1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a severe neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the progressive deterioration of motor neurons, resulting in muscle paralysis and eventual death within 2–5 years from onset [

1]. The exact pathogenesis of ALS is not fully understood and involves various pathophysiological pathways, including neuroinflammation [

2], iron accumulation [

3], and microRNA (miRNA) dysregulation [

4], among others. The multifaceted nature of ALS and the absence of a clearly defined mechanism suggest that a combination of pathways contributes to neurodegeneration in ALS, necessitating a multi-targeted therapeutic approach.

PrimeC is a novel formulation composed of unique doses of ciprofloxacin and celecoxib, aiming to synergistically inhibit the progression of ALS by addressing key elements of its pathophysiology, namely miRNA dysregulation, neuroinflammation and iron accumulation.

Ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic, has demonstrated binding to the RNA-binding protein TRBP, facilitating its association with the RISC-loading complex and regulating miRNA processing [

5]. Imbalances in these processes are observed in ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases [

6]. Ciprofloxacin also functions as an iron chelator [

7], with various examples of iron chelators reducing brain iron stores and exhibiting neuroprotective effects in neurodegenerative diseases [

8].

Celecoxib, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is known for its selective COX-2 inhibition, complemented by COX-2-independent mechanisms contributing to its anti-inflammatory action [

9].

Preclinical studies combining celecoxib with ciprofloxacin showed a synergistic effect in zebrafish ALS models, with benefits to motor function as well as to central nervous system (CNS) cell morphology [

10].

In a Phase IIa clinical study aimed to assess PrimeC’s potential beneficial effects, results showed safety and tolerability in people living with ALS (PALS) [

11]. The study also demonstrated, via relevant biomarkers (e.g., TDP-43, PgJ2 and LC3), a promising biological effect for the combination on mitigating disease progression. A subsequent Phase IIb clinical trial aiming to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of PrimeC in PALS through a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study (PARADIGM; NCT05357950), demonstrated consistently positive effects across all clinical outcomes (ALSFRS-R total score and sub-domains, SVC, etc.), with a favorable safety and tolerability profile. PrimeC treatment slowed disease progression, trended towards an improved survival, demonstrated beneficial regulation of miRNA, and effectively modulated iron metabolism, as observed by regulation of transferrin and ferritin (unpublished data).

Combination therapy is most widely used in treating the most dreadful diseases, such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and is gaining widespread recognition by scientists and clinicians as a novel therapeutic approach. By combining two FDA approved drugs, we aim to achieve synergistic therapeutic effects, dose and toxicity reductions, and to thereby minimize or delay the induction of drug resistance.

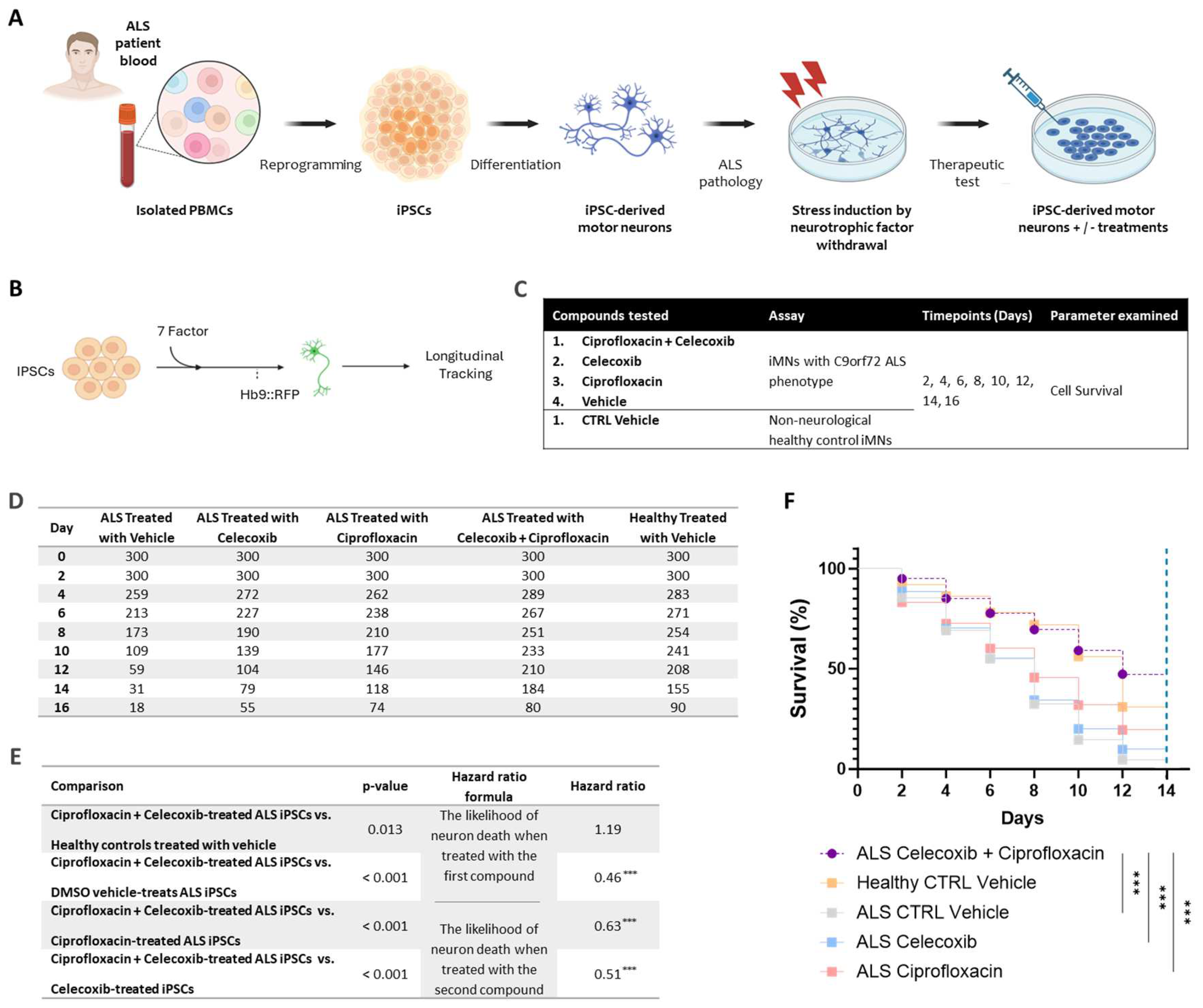

To assess the synergistic effect of the PrimeC combination, two preclinical studies were conducted: (1) an in vitro study aimed to examine the synergistic effect of the PrimeC combination compared to each compound (ciprofloxacin and celecoxib) alone using human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived motor neurons (MNs) with ALS pathology (C9orf72); (2) drug concentration profiling in a C57BL mouse strain.

These findings, together with the proposed mechanistic framework and the preclinical evidence presented, underscore the potential of PrimeC as a novel combination therapy for neurodegenerative diseases, particularly ALS. This integrated approach sets the stage for advancing PrimeC as an innovative therapeutic strategy in this field.

2. Results

2.1. Elucidating The Neurotherapeutic Effects of the PrimeC Combination Relative to Single Agents Utilizing an iPSC Assay

Upon conducting the initial viability analysis for the entire 16-day period, a substantial drop in the quantity of survived cells from healthy control treatment conditions was observed between days 14 and 16. This trend could indicate a senescence effect not related to treatment effects, but rather to the cells’ tendency to simply degenerate under normal in vitro culture conditions such as this one. In order to ensure equitable comparisons with the rest of the experimental conditions, we referred to the number of induced motor neurons (iMNs) on day 16 as an outlier in all of the analyses. Thus, the different cell survival rate comparisons were conducted for a 14-day range, excluding day 16.

As expected, survival analysis comparing the non-treatment control conditions, conveyed a significantly better survival rate for the healthy control iMNs compared to ALS patient-derived iMNs treated with the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle dose (Hazard ratio=0.5, p < 0.001). The median survival time of DMSO-treated healthy control iPSCs was significantly longer than DMSO-treated ALS iPSCs median survival time (12 days vs. 8 days, p < 0.001; see

Figure 1D &

Figure 1F). These results establish that ALS-patient derived iMNs do indeed exhibit the expected characteristic of increased neurodegeneration compared to iMNs derived from neurologically healthy controls.

The survival rate of ALS iMNs treated with the ciprofloxacin + celecoxib combination was significantly higher than ALS vehicle-treated iMNs (Hazard ratio = 0.46, p < 0.001). The median survival of PrimeC combination-treated iMNs was higher than the median survival of DMSO vehicle-treated cells (12 days vs. 8 days; p < 0.001; see

Figure 1D-F).

The survival rate of iMNs treated with the ciprofloxacin + celecoxib combination was significantly higher than iMNs treated with ciprofloxacin alone (Hazard ratio = 0.63, p < 0.001). The median survival time for PrimeC combination-treated iPSCs was 12 days, which was significantly longer than ciprofloxacin-treated iPSCs’ median survival (8 days; p < 0.001; see

Figure 1D-F). The survival rate of iMNs treated with the ciprofloxacin + celecoxib combination was significantly higher than those treated with celecoxib alone (Hazard ratio = 0.51, p < 0.001). The median survival time for PrimeC combination-treated iPSCs was also significantly longer than celecoxib-treated iPSCs (12 days vs. 8 days; p < 0.001; see

Figure 1D-F).

Moreover, the survival rate of iMNs treated with the ciprofloxacin + celecoxib combination slightly surpassed the healthy controls (Hazard ratio = 1.19, p = 0.013). PrimeC-treated cells survived slightly longer than DMSO-treated healthy control iPSCs (see

Figure 1D-F).

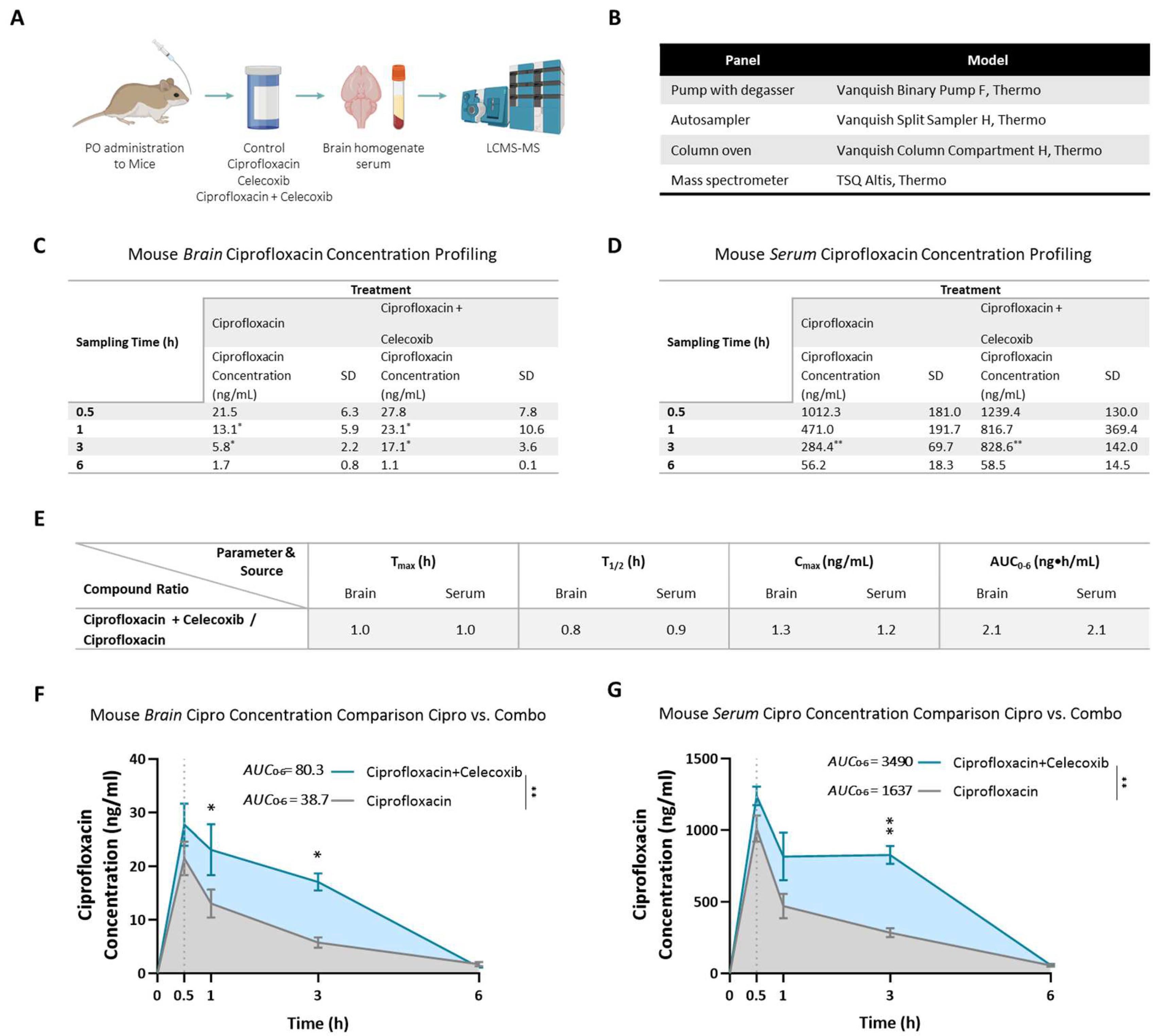

2.2. Evaluating the Improved Drug Concentration Profiling of the PrimeC Combination Relative to Single Active Drug Administration in Mice

The drug concentration profile of the PrimeC combination in C57BL mice brain and serum was tested following acute single dose per os (PO) administration. The drug concentration profile of ciprofloxacin alone was compared to the drug concentration profile of the combination compound of PrimeC.

Ciprofloxacin concentrations in brain and serum following PO administration were quantifiable in all sampling time points. The time at which the maximum mean concentration of ciprofloxacin occurred (Tmax) following PO administration is 0.5 hours in both the brain and the serum in all treatment groups. The ciprofloxacin brain and serum concentrations declined in a log-linear manner starting at approximately 0.5 hours post dose. For the ciprofloxacin-treated group, terminal half-life (t1/2) of ciprofloxacin was calculated as 1.6 and 1.4 hours in the brain and serum, respectively. For the PrimeC combination group, terminal half-life (t1/2) of ciprofloxacin was calculated as 1.2 and 1.3 hours in the brain and serum, respectively.

C

max values showed a 30% increase of ciprofloxacin in brains of the PrimeC combination-treated group (C

max = 27.8 ng/mL) compared to the ciprofloxacin-treated group (C

max = 21.5 ng/mL). In serum, C

max values showed a 20% increase of ciprofloxacin for the PrimeC combination-treated group (C

max = 1239.4 ng/mL) compared to the ciprofloxacin-treated group (C

max = 1012.3 ng/mL; see

Figure 2E).

AUC

0-6h values showed a 108% increase of ciprofloxacin in brains of the PrimeC combination-treated group (AUC

0-6h = 80.27 ng*h/mL) compared to the ciprofloxacin-treated group (AUC

0-6h = 38.69 ng*h/mL; 95% CI [-10.97, -2.563], p < 0.001; see

Figure 2E-F). In serum, AUC

0-6h values showed a similar 113% increase of ciprofloxacin for the PrimeC combination-treated group (AUC

0-6h = 3490 ng*h/mL) compared to the ciprofloxacin-treated group (AUC

0-6h = 1637 ng*h/mL; 95% CI [-419.2, -140.5], p < 0.001; see

Figure 2E &

Figure 2G).

Ciprofloxacin concentration levels displayed a significant difference throughout the duration of the study between the PrimeC combination-treated group and the ciprofloxacin-treated group in brain (F(1,8) = 11.72, p = 0.009; see

Figure 2F) and in serum (F(1,8) = 18.74, p = 0.003; see

Figure 2G). In the brain, Bonferroni post-hoc test revealed significant differences in favor of the PrimeC combination-treated group at time points 1 hour (Predicted LS Mean Difference = 10.2, 95% CI [0.1127, 19.93], p = 0.047) and 3 hours (Predicted LS Mean Difference = 11.34, 95% CI [1.428, 21.25], p = 0.020; see

Figure 2C &

Figure 2E-F). In serum, Bonferroni post-hoc test revealed a significant difference in favor of the PrimeC combination-treated group at the 3 hour time point (Mean Difference = -544.2, 95% CI [-796.3, -292.1], p = 0.001; see

Figure 2D-E &

Figure 2G).

3. Discussion

This paper examined the synergistic effect of ciprofloxacin and celecoxib in vitro as a combination treatment in an iPSC-derived MN model, and the drug concentration profile of the PrimeC combination in vivo in mice. The safety, superior drug concentration profile, and synergistic neurotherapeutic effects of the PrimeC combination support its potential as a novel therapeutic agent for ALS.

Human iPSC-derived iMN models serve as a valuable platform for enabling drug screening approaches aimed at identifying compounds and combinations that can mitigate the impact of ALS pathophysiology. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are a type of white blood cells commonly used for generating iPSCs due to their ease of collection and reprogramming [

12]. The lymphocytes from the human PBMCs are then reprogrammed into iPSCs. Cellular reprogramming, and particularly the generation of iPSCs, has significant benefits for drug development, as they can be generated from patient-specific cells, such as skin or blood cells, and differentiated into various cell types. Deriving patient iMNs recapitulates the neurodegeneration involved in ALS, allowing for the creation of ALS in vitro models which ultimately provide a platform for drug screening and testing [

13]. Furthermore, cellular reprogramming enables high-throughput, personalized drug screening on patient-derived neurons. Revolutionizing drug development, iPSCs provide more accurate and efficient models for disease research and drug discovery, enabling an examination of the efficacy of the PrimeC combination using state of the art in vitro cellular techniques.

For over a decade, iPSCs have been utilized as a valid and valuable disease modelling platform, enabling high-throughput drug screening to identify therapeutic applications for diseases such as ALS [

14]. Multiple research groups have established various ALS iPSC models as powerful tools for recapitulating disease phenotypes manifested by neurodegeneration, cell death mechanisms, phenotypical progression, etc. [

15]. For instance, ropinirole was identified as a potential therapeutic candidate for ALS in a large in vitro iPSC drug screening [

15], which led to a Phase I/II trial [

16,

17]. Indeed, these iMNs derived from PALS recapitulate the neurodegeneration involved in ALS, thus providing a valid and biologically relevant in vitro model system [

13,

18].

In this study, neuronal survival rate of PrimeC combination-treated iPSCs demonstrated similar survival rates to those of healthy controls, higher than vehicle-treated ALS iMNs, and significantly higher than ALS iMNs treated with ciprofloxacin or celecoxib alone. This is especially relevant taking into account the recent prospects of iPSC models in screening and developing regenerative medicinal products, enabling associations with three-dimensional multicellular organoids (e.g., gene editing, organs-on-a-chip, different “omics” methodologies, etc.) for future work [

19]. ALS drug development has recently witnessed a spurt of iPSC-based studies, either for mechanism examination, safety, drug screening or efficacy [

15,

16,

20]. However, many of the disease models encounter challenges in replicating disease phenotypes, primarily attributable to the inherent iPSC immaturity issues, and the absence of their corresponding native environmental cues [

19]. Strategies directed at augmenting iPSC maturation phenotypes will enable surmounting the challenges associated with polygenic, sporadic, and late-onset disease models, such as ALS.

The drug concentration profile study results suggest that ciprofloxacin exposure was higher following the administration of the PrimeC combination than when administering ciprofloxacin alone. Overall, this proof-of-concept study in mice demonstrated that the combination of the two active substances improved the therapeutic mode of action relative to administration of a single active drug. Previous studies have shown enhanced concentrations of ciprofloxacin in blood when administered in combination with other active substances targeting different pathologies [

21]. However, this examination is the first of its kind in assessing the additive effect of ciprofloxacin with celecoxib, substantiating their combination as a viable therapeutic formulation.

These findings may also indicate that the combination could enhance ciprofloxacin’s penetration of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This aligns with prior research showing that ciprofloxacin is a known multi-drug resistance 1 (MDR1) substrate [

22], and that celecoxib inhibits MDR1, leading to increased intracellular ciprofloxacin levels [

23]. Moreover, ALS-specific pharmacoresistance mechanisms have been identified, with selective upregulation of drug efflux transporters in the SOD1 G93A mouse model [

24], reinforcing the relevance of MDR1 inhibition in ALS. Additionally, COX inhibition has been associated with a 70–100% increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) ciprofloxacin concentrations [

25], further supporting the hypothesis that celecoxib may enhance fluoroquinolone CNS penetration. This suggested potential utility in addressing CNS-related pathologies warrants further investigation.

Taken together, this collective study demonstrates the beneficial effect of ciprofloxacin and celecoxib to ALS-related therapy, and the synergistic effects they hold in combining the two components. This multiple-angle approach substantiates the sound proof of concept PrimeC holds, addressing an improved drug concentration profile and enhanced survival. In conclusion, the aforementioned findings set the stage for the use of PrimeC as a potentially safe and effective treatment for ALS.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Motor Neuron (MN) Survival

In this study, iPSC-derived iMNs were generated from PALS (C9orf72 pathology) and from healthy donors’ PBMCs. Neuronal survival rate was compared between PrimeC’s components, their combination and the relevant DMSO vehicle reference as described in

Figure 2A-C. Cell survival was measured by longitudinally tracking iMNs at days 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16 post treatment for each treatment condition.

4.1.1. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) Isolation

In this study, iPSC-derived iMNs were generated from PBMCs, which are a type of white blood cells commonly used for generating iPSCs due to their ease of collection and reprogramming [

12]. Lymphoblastoid cell lines from healthy donors as well as from PALS were obtained from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Biorepository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research. (C9 ALS: ND06769, ND10689, and ND12099; CTRLS: ND03231, ND03719, and ND05280).

4.1.2. iPSC Generation

Lymphocytes sourced from individuals with ALS to generate iPSCs were then utilized. The lymphocytes were reprogrammed into iPSCs using episomal vectors- they were transfected with mammalian expression vectors carrying Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, L-Myc, Lin28, and a p53 shRNA using the Adult Dermal Fibroblast Nucleofector Kit and Nucleofector 2b Device (Lonza) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, the cells were cultured on mouse feeders until iPSC colonies emerged. These colonies were then expanded and sustained on Matrigel (BD) in mTeSR1 medium (Stem Cell Technologies) (Following [

26]).

4.1.3. iPSC-Derived iMNs

iPSCs were differentiated into fibroblast-like cells to enable efficient retroviral transduction. Briefly, iPSCs were plated in several T-75 flasks coated with Matrigel and the media was changed to fibroblast media (DMEM +10% FBS) at 30%–50% confluency. The media was changed once a week until the appearance of fibroblast-like cells. The formation is cell line dependent and ranges from 30 to 50 days. Reprogramming experiments were conducted using either 96-well plates. These were coated sequentially with gelatin (0.1% for 1 hour at room temperature) and laminin overnight (4°C, overnight). For each well of the 96-well plates, 7 iMN factors were added in 150 μl of fibroblast medium, along with 8 μg/ml of polybrene. Lentivirus encoding the Hb9::RFP reporter (labels motor neurons) was transduced into iMN cultures 48 hours after the initial transduction with retroviruses encoding transcription factors. On day 4, primary mouse cortical glial cells derived from P2-P3 ICR pups (both male and female) were added to the transduced cultures in glia medium, which consisted of MEM (Life Technologies), 10% donor equine serum (HyClone), 20% glucose (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. On day 5, the cultures were switched to N3 medium, containing DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies), 2% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, N2 and B27 supplements (Life Technologies), 7.5 μM RepSox (Selleck), and 10 ng/ml each of GDNF, BDNF, and CNTF (R&D). The iMN cultures were maintained in N3 medium, with medium changes performed every other day until day 16 (Following[

26]).

4.1.4. iMN Assay

Hb9:RFP+ iMNs form between day 13–16 after transduction of iMN factors. The iMN survival assay was initiated on day 17. Starting at Day 17, longitudinal tracking of iMNs was performed using Molecular Devices ImageExpress once every other day for 16 days. Tracking of neuronal survival was performed using ImageJ. Neurons were scored as dead when their soma was no longer detectable by RFP fluorescence. iMN survival experiments included neurotrophic factor withdrawal in order to exacerbate the survival difference between control and PALS’ iMNs. Neurotrophic factor withdrawal of FGF-2, BDNF, GDNF, and CNTF from the culture medium was performed on day 17. For treatment with drugs, cultures were treated with DMSO or drug after neurotrophic factor withdrawal (starting at day 17). Treatment with fresh media containing vehicle or drugs occurred every 3 days for 16 days. In order to assess the different effects of PrimeC on the iPSC derived C9orf72 cells we used the following comparisons: iMNs treated with the combination dose of ciprofloxacin + celecoxib, cells treated with ciprofloxacin or celecoxib alone, and a vehicle control. Control cell lines of non-neurological subjects (i.e., neurologically healthy controls) were used in the comparisons. Three replicates per condition were used- three healthy control lines (n=100 iMNs/line X 3 lines=300 total iMNs) and three PALS lines (n=100 iMNs/line X 3 lines=300 total iMNs).

A hazard ratio was calculated for each of the comparisons as the likelihood of neuron death when treated with the indicated compound divided by the likelihood of neuron death when treated with another indicated compound. The higher the ratio, the more likely it is for a cell to die when treated with the second compound compared to being treated with the first compound in each comparison above.

4.1.5. Statistical Analysis

Multiple groups and/or time points were analyzed utilizing two-way ANOVA, and when appropriate, a two-way ANOVA repeated measurements (time x groups).

Analysis utilized Prism Origin (GraphPad Software) software package. For iMN survival, a 2-sided log-rank test was employed to accommodate instances where events did not occur (iMNs that did not degenerate before the experiment’s conclusion). In each case, 300 iMNs were selected to generate survival curves. If all iMNs degenerated in a given experiment, a 2-tailed Student’s t test was used for statistical significance.

The normal distribution of datasets was tested using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Multiple group differences were assessed via One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction for all comparisons, unless the data were non–normally distributed, in which case nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis testing was applied. Normally distributed datasets used mean and standard deviation or standard error of the mean, while non–normally distributed datasets used median and interquartile range. Differences between two groups were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student’s t test, unless the data were non–normally distributed, in which case 2-sided Mann-Whitney testing was utilized. Upon conducting Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, significance was assumed at p ≤ 0.0125.

Kaplan-Meier plots were generated using iMNs obtained from each treatment condition in replicates of three. Confirmation of iMN survival times were analyzed by manual longitudinal tracking.

4.2. Drug Concentration Profiling of the PrimeC Combination in C57BL Mice

The drug concentration profile of the PrimeC combination in C57BL strain mice’s brain and blood (serum) was tested following acute oral administration (PO; single dose). The drug concentration profile of ciprofloxacin alone was compared to the drug concentration profile of the combination compound of ciprofloxacin and celecoxib (i.e., the PrimeC combination). To this aim, a total of 58 male mice aged 8 weeks were utilized in the study, which was conducted in two cycles of 12 groups with 4-6 animals per group. The tested mice were PO administered (oral gavage) at timepoint 0 (see

Figure 2A-B for study design).

4.2.1. Mice

The C57BL strain male mouse model was used (Envigo RMS,Israel Ltd.). Animals’ handling was performed according to guidelines of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC), and Pharmaseed standard operating procedures (SOPs). The animals were monitored for morbidity and mortality, body weight (BW), clinical signs and bleeding during the dosing times. This study was performed in compliance with “The Israel Animal Welfare Act”; and following “The Israel Board for Animal Experiments”; Ethics Committee # NPC-Ph-IL2109-110-3.

4.2.2. Formulation Preparation

C57BL mice were treated with distinct concentrations of the PrimeC combination of celecoxib (Hikal Ltd., India) and ciprofloxacin (Neuland Laboratory Ltd., India), or with ciprofloxacin alone.

The solutions for both active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), ciprofloxacin and celecoxib, were prepared under appropriate conditions to yield specific predetermined concentrations. The solutions were administered orally.

4.2.3. Ciprofloxacin Liquid Chromatography with Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (LCMS-MS)

Blood and Serum Extraction

Approximately 350 μL of whole blood was collected into tubes containing a clotting activator gel. The blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for at least 30 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting serum was separated, transferred into Eppendorf tubes (or equivalent), and stored at -80°C until further analysis for ciprofloxacin quantification using the LC-MS/MS method (see

Figure 1B).

Brain Tissue Extraction

At the termination timepoints, animals were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of a Ketamine-Xylazine mixture (90:10 mg/kg, respectively) and briefly perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Following sacrifice as approved by the Ethics Committee (Approval No. NPC-Ph-IL2109-110-3), brains were collected, weighed, and processed. Each brain was rinsed with ice-cold PBS, minced, and homogenized in 1 mL of ice-cold PBS using the gentleMACS™ Dissociator (Program Protein_01_01). The homogenates were then sonicated and centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was aliquoted and stored at -80°C until further analysis for ciprofloxacin quantification using the LC-MS/MS method (see

Figure 1B).

LC-MS/MS Analysis

Both serum and brain supernatant samples were analyzed for ciprofloxacin quantification using the LC-MS/MS method.

4.2.4. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using the computer program PK Solutions 2.0 (Summit Research Services, USA). The following pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated:

Maximum observed ciprofloxacin concentrations (Cmax) in serum and brain samples and their times of determination (Tmax) were the obtained values. Standard deviations were reported to the same precision as the corresponding mean value. Unless stated otherwise, all summary statistics (e.g., Mean, SD) presented are based upon rounded numbers.

Areas under concentration-time curves up to the last quantifiable concentration (AUC0-6) were calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. In the calculation of AUC0-6 values, it was assumed that the pre-dose (0 hours) ciprofloxacin concentrations were zero. Data permitting, the terminal elimination rate constant (λZ) was estimated by fitting a linear regression of log concentration against time, and t½ was calculated as ln2/λZ. For the estimate of λZ to be accepted as reliable, the following criteria were imposed:

The terminal data points were apparently randomly distributed about a single straight line (on visual inspection)

A minimum of three data points was available for the regression

The regression coefficients ≥ 0.85

The interval including the data points chosen for the regression was at least two-fold greater than the half-life itself

A mixed model for repeated measures followed by a post hoc Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons was performed for between-group comparisons of ciprofloxacin concentrations, statistical significance set at p ≤ 0.05. This analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.2 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA,

www.graphpad.com.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this collective study, comprised of an in vitro iPSC assay as well as an in vivo study in mice, demonstrates the beneficial effect of the ciprofloxacin and celecoxib combination on ALS-related pathology, and the synergistic effects they hold by combining these two components. This multidisciplinary approach substantiates the sound proof of concept PrimeC holds, addressing enhanced survival and improved drug concentration profiling. In summary, the aforementioned findings set the stage for the use of PrimeC as a potentially safe and effective treatment for ALS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.Z., J.K.I., G.R.L. and F.T.; methodology, S.S.Z., N.R.B., J.K.I., G.R.L.; software, N.K, J.K.I., G.R.L.; validation, S.S.Z., N.K. and G.R.L.; formal analysis, N.K., J.K.I. and G.R.L; investigation, S.S.Z., N.K., J.K.I. and G.R.L; resources, S.S.Z., F.T., J.K.I; data curation, J.K.I., G.R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K; writing—review and editing, S.S.Z., N.K, N.R.B., F.T., J.K.I and G.R.L; visualization, N.K.; supervision, F.T.; project administration, S.S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by NeuroSense Therapeutics, Ltd. (Drug Concentration Profiling of the PrimeC Combination in C57BL Mice) towards external analyses conducted by two clinical research organizations (CROs): Pharmaseed Ltd. & Selvita S.A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study was conducted in accordance with “The Israel Animal Welfare Act” and approved by “The Israel Board for Animal Experiments” Ethics Committee # NPC-Ph-IL-2109-110-3.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

In beloved memory of Shay Rishoni, an inspiring ALS advocate and patient, whose strength, determination, and unwavering dedication to advancing ALS research were instrumental in the founding of NeuroSense Therapeutics. His legacy continues to drive progress in the fight against ALS, and PrimeC stands as a tribute to his vision and relentless pursuit of hope for those living with ALS. We extend our heartfelt appreciation to Alon Ben-Noon, CEO of NeuroSense Therapeutics, whose vision and dedication have been instrumental in building the company from its inception, driving its mission forward to develop effective treatments for ALS. Our sincere gratitude goes to our esteemed Scientific Advisory Board members— Dr. Jinsy Andrews, Prof. Jeremy Shefner, Prof. Merit Cudkowicz, Prof. Orla Hardiman, and Prof. Jeffrey Rosenfeld, for their invaluable guidance and contributions to ALS research. We also wish to acknowledge Ariel Gordon, NeuroSense Therapeutics’ first investor, for his early support and belief in our mission, and Avital Pushett, NeuroSense’s first employee, whose dedication and scientific expertise were instrumental in transforming PrimeC from a concept into a reality.

Conflicts of Interest

S.S.Z., N.K., N.R.B. and F.T. are employees of NeuroSense Therapeutics. NeuroSense Therapeutics owns patent rights to the ciprofloxacin & celecoxib combination that was used in these studies. J.K.I. is employed by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc and is a co-founder of AcuraStem and Modulo Bio. J.K.I. is on the scientific advisory boards of AcuraStem, Vesalius Therapeutics, Spinogenix, and Synapticure. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALS |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| AIDS |

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| iPSCs |

Induced pluripotent stem cells |

| PK |

Pharmacokinetic |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| miRNA |

MicroRNA |

| TRBP |

Transactivation response element RNA-binding protein |

| RISC |

RNA-induced Silencing Complex |

| NSAID |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| COX-2 |

Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| PALS |

People living with ALS |

| TDP-43 |

TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| PgJ2 |

15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 |

| LC3 |

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 |

| ALSFRS-R |

Revised Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale |

| SVC |

Slow Vital Capacity |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| MNs |

Motor neurons |

| iMNs |

Induced motor neurons |

| C9orf72 |

Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 |

| PBMCs |

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| NINDS |

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke |

| C9 |

C9orf72 samples |

| CTRL |

Controls |

| shRNA |

Short hairpin RNA |

| Oct4 |

Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 |

| Sox2 |

Sex determining region Y-box 2 |

| KLF4 |

Kruppel-like factor 4 |

| L-Myc |

L-myc-1 proto-oncogene protein |

| Lin28 |

Lin-28 homolog A protein gene |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| MEM |

Minimum essential medium |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium |

| GDNF |

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BDNF |

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CTNF |

Ciliary neurotrophic factor |

| RFP |

Red fluorescent protein |

| FGF-2 |

Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| PO |

Per os |

| NIH |

National Institute of Health |

| AAALAC |

Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care |

| SOP |

Standard operating procedure |

| BW |

Body weight |

| API |

Active pharmaceutical ingredients |

| LCMS-MS |

Liquid Chromatography with Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer |

| mg |

Milligram |

| kg |

Kilogram |

| ng |

Nanogram |

| mL |

Milliliter |

| h |

Hour |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

| t1/2 |

Terminal half life |

| Tmax |

Transport maximum |

| Cmax |

Maximum concentration |

| BBB |

Blood-brain barrier |

| MDR1 |

Multi-drug resistance 1 |

References

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1602–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, F. Role of Neuroinflammation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Cellular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1005–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndayisaba, A.; Kaindlstorfer, C.; Wenning, G.K. Iron in Neurodegeneration—Cause or Consequence? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Melo, D.; Droppelmann, C.A.; He, Z.; Volkening, K.; Strong, M.J. Altered microRNA expression profile in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a role in the regulation of NFL mRNA levels. Mol. Brain 2013, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; E Szulwach, K.; Duan, R.; A Faghihi, M.; Khalil, A.M.; Lu, L.; Paroo, Z.; et al. A small molecule enhances RNA interference and promotes microRNA processing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, C.; Marzocchi, C.; Battistini, S. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells 2018, 7, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, S.; Her, Y.F.; Maher, L.J. Nonantibiotic Effects of Fluoroquinolones in Mammalian Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 22287–22297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuñez, M.T.; Chana-Cuevas, P. New Perspectives in Iron Chelation Therapy for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopfová, L.; Šmarda, J. The use of Cox-2 and PPARγ signaling in anti-cancer therapies. Exp. Ther. Med. 2010, 1, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldshtein, H.; Muhire, A.; Légaré, V.P.; Pushett, A.; Rotkopf, R.; Shefner, J.M.; Peterson, R.T.; Armstrong, G.A.B.; Blum, N.R. Efficacy of Ciprofloxacin/Celecoxib combination in zebrafish models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 1883–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon-Zimri, S.; Pushett, A.; Russek-Blum, N.; Van Eijk, R.P.A.; Birman, N.; Abramovich, B.; Eitan, E.; Elgrart, K.; Beaulieu, D.; Ennist, D.L.; et al. Combination of ciprofloxacin/celecoxib as a novel therapeutic strategy for ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2022, 24, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hokayem, J.; Cukier, H.N.; Dykxhoorn, D.M. Blood Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): Benefits, Challenges and the Road Ahead. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.; Piedrahita, J.A. Generation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) from Adult Canine Fibroblasts. Methods Mol Biol. 2015, 1330, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, A.D.; Liang, P.; Wu, J.C. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells as a Disease Modeling and Drug Screening Platform. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2012, 60, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Otomo, A.; Atsuta, N.; Nakamura, R.; Akiyama, T.; Hadano, S.; Aoki, M.; Saya, H.; Sobue, G.; et al. Modeling sporadic ALS in iPSC-derived motor neurons identifies a potential therapeutic agent. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, H.; Yasuda, D.; Fujimori, K.; Morimoto, S.; Takahashi, S. Ropinirole, a New ALS Drug Candidate Developed Using iPSCs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, S.; Takahashi, S.; Ito, D.; Daté, Y.; Okada, K.; Kato, C.; Nakamura, S.; Ozawa, F.; Chyi, C.M.; Nishiyama, A.; et al. Phase 1/2a clinical trial in ALS with ropinirole, a drug candidate identified by iPSC drug discovery. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 766–780.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós, M.A.; Choi, E.S.; Cofré, A.R.; Dokholyan, N.V.; Duzzioni, M. Motor neuron-derived induced pluripotent stem cells as a drug screening platform for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 962881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, M.X.; Sachinidis, A. Current Challenges of iPSC-Based Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2019, 8, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasteuning-Vuhman, S.; de Jongh, R.; Timmers, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J. Towards Advanced iPSC-based Drug Development for Neurodegenerative Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelín-Jiménez, G.; Ángeles, A.P.; Martínez-Rossier, L.; Fernández, A.S. Ciprofloxacin Bioavailability is Enhanced by Oral Co-Administration with Phenazopyridine. Clin. Drug Investig. 2006, 26, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuppalanchi, R.; Miller, M.; Gorski, J.C.; Renbarger, J.L.; Galinsky, R.E.; Hall, S.D. Effect of MDR1 genotype (G2677T) on the disposition of ciprofloxacin in adults. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 77, P31–P31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalle, A.M.; Rizvi, A. Inhibition of Bacterial Multidrug Resistance by Celecoxib, a Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonski, M.R.; Jacob, D.A.; Campos, C.; Miller, D.S.; Maragakis, N.J.; Pasinelli, P.; Trotti, D. Selective increase of two ABC drug efflux transporters at the blood–spinal cord barrier suggests induced pharmacoresistance in ALS. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 47, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naora, K.; Katagiri, Y.; Ichikawa, N.; Hayashibara, M.; Iwamoto, K. Enhanced entry of ciprofloxacin into the rat central nervous system induced by fenbufen. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991, 258, 1033–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Lin, S.; A Staats, K.; Li, Y.; Chang, W.-H.; Hung, S.-T.; Hendricks, E.; Linares, G.R.; Wang, Y.; Son, E.Y.; et al. Haploinsufficiency leads to neurodegeneration in C9ORF72 ALS/FTD human induced motor neurons. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).