1. Introduction

Freshwater fish biodiversity is being increasingly imperiled by a range of factors globally (Dudgeon et al., 2006). The vulnerability of fish habitats arises from the fact that they can be extracted, diverted, contained, or contaminated by humans in ways that compromise their value as habitats for fish biota. Furthermore, the complex and often synergistic interactions between ecosystem stressors or threats to freshwater fish biodiversity will be compounded by human-induced global climate change, causing higher temperatures and shifts in precipitation and river runoff (IPCC, 2007) and increasing the difficulty of predicting outcomes for biodiversity and consequential extinction risks (Brook et al., 2008).

Human activities have degraded most ecosystems on earth, with over 83% of terrestrial landscapes being under direct human impact (Meybeck, 2004). This is particularly important for riverine systems because they are heavily influenced by surrounding environments (Allan & Flecker, 1993; Allan, 2004). As a result, these ecosystems are becoming increasingly degraded, hence a concern for resident fauna considering their limited ability to disperse and escape the affected area (Olden et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). Rivers and lakes are home to some of the most diverse and unique ecosystems on the planet. However, habitat loss and degradation have led to a significant decrease in aquatic biodiversity worldwide (Allan & Flecker, 1993). Freshwater fishes had the highest extinction rate among vertebrates in the 20th century (Burkhead, 2012), while freshwater fauna are projected to have a future extinction rate five times that of their terrestrial counterparts (Ricciardi & Rasmussen, 1999).

Land transformation for agriculture and urbanization has led to sedimentation, pollution by nutrients, and changed runoff patterns, leading to direct mortality of biota by poisoning and aquatic habitat degradation, and sub-lethal effects and physiological impairment that may cause extinction over longer time scales (Thieme et al., 2010). Pollutants may result in eutrophication, toxic algal blooms, and fish kills that are associated with biodiversity losses. Lakes and rivers are landscape ‘receivers’ (Dudgeon et al., 2006) and catchment condition impacts biodiversity via multiple complex direct and indirect pathways. Furthermore, downstream assemblages in streams and rivers are affected by upstream processes.

Trewavas (1983) and Kapute (2018) reported that the Southeast Arm of Lake Malawi and Lake Malombe fish nursery grounds have been degraded by the clearing of aquatic vegetation to construct beaches in front of resorts and cottages, while dragging seine nets along the substrate has also destroyed the nests built by the Chambo and disrupted their spawning. Currently, about 102 fish species are listed on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Data List as endangered (Malawi Environmental Affairs Department report, 2010). The degradation of these critical fish nursery grounds highlights the urgency of addressing both local and broader environmental threats to freshwater biodiversity. Effective conservation strategies must incorporate integrated land and water management practices, taking into account the interrelated nature of habitat destruction and climate change impacts to ensure the long-term sustainability of these vital ecosystems.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Area

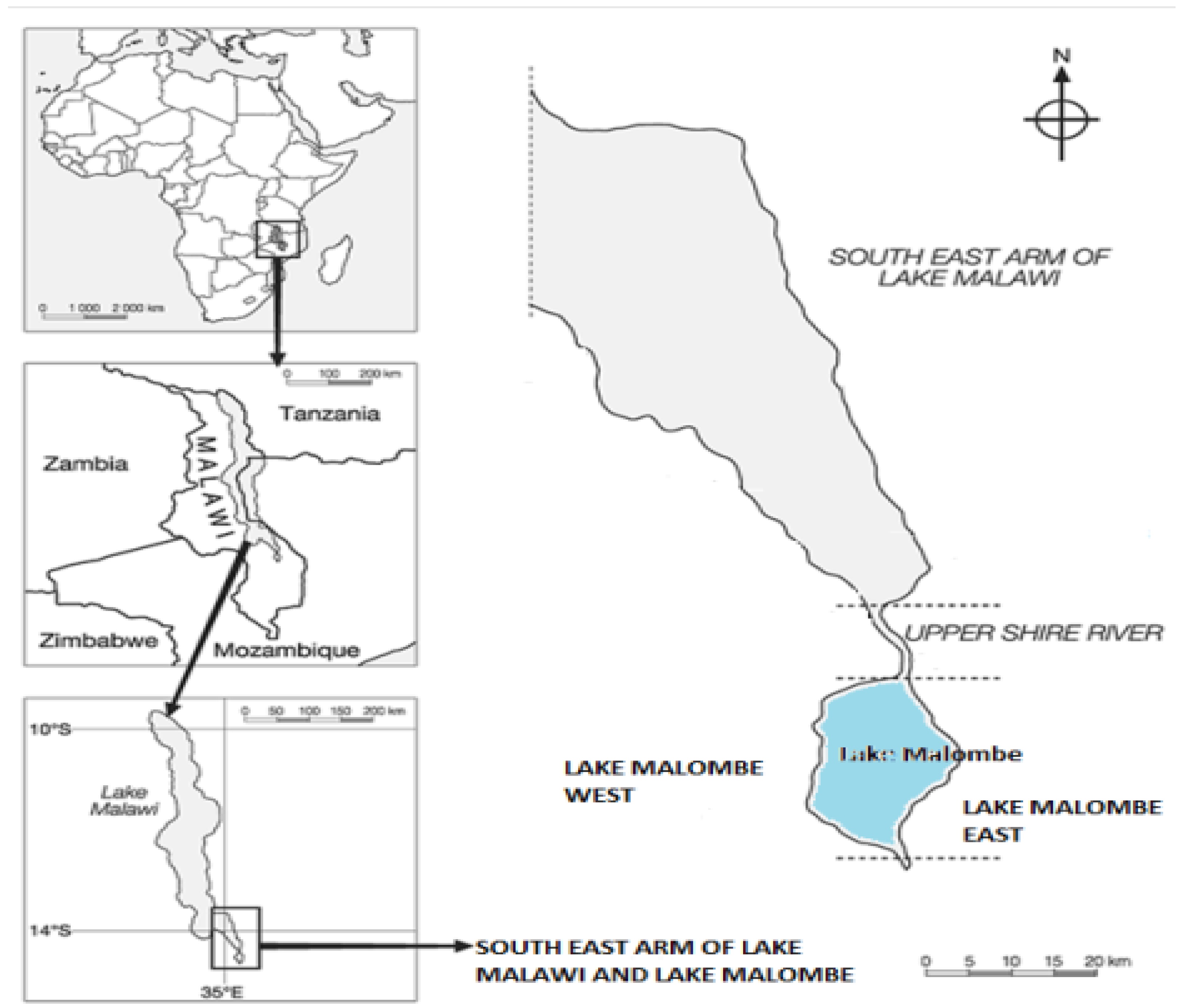

The study was conducted in the Southeast Arm of Lake Malawi, Lake Malombe, and Upper Shire River, located in the southern part of Malawi between 13.8- and 14.9-degrees south latitude and between 34.2- and 35.3-degrees east longitude. The catchment area has a total area of 9,914 km², of which 3,844 km² comprises water and marshy areas. This region is characterized by a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. The wet season, which spans from November to April, brings heavy rainfall, while the dry season from May to October experiences significantly lower precipitation.

The Southeast Arm of Lake Malawi is one of the most biologically diverse freshwater ecosystems in the world, home to a rich variety of endemic fish species. This area, along with Lake Malombe and the Upper Shire River, serves as a crucial habitat for many fish species, providing breeding and nursery grounds that are essential for maintaining fish populations.

Lake Malombe, a shallow lake south of Lake Malawi, is connected to the larger lake via the Upper Shire River. The Upper Shire River flows from the southern end of Lake Malawi, through Lake Malombe, and eventually into the Zambezi River. These water bodies are integral to the local hydrology and ecology, supporting not only fish but also various other aquatic and terrestrial species. The region's economy heavily relies on fishing, agriculture, and tourism, making the sustainability of these ecosystems vital for the livelihoods of the local communities.

The catchment area surrounding these water bodies includes a mix of land uses, such as agricultural fields, natural forests, agroforests, grasslands, settlements, and bare lands. Agricultural activities dominate the landscape, with crops like maize, cassava, and rice being the primary cultivars. These agricultural practices, along with expanding settlements, have led to significant land cover changes over the years.

The study area's geographical and ecological characteristics make it an ideal location for investigating the impacts of land use and land cover changes on fish biodiversity and productivity.

Figure 1 below provides a detailed map showing the location and extent of the Southeast Arm of Lake Malawi, Lake Malombe, and the Upper Shire River as of 2012.

2.2. Field Data Collection

Field data collection involved gathering both qualitative and quantitative information crucial for assessing the impact of land use and land cover changes on fish biodiversity and catches. Qualitative data included observations of fish colors, species sex, and imagery maps showing land use and land cover. Quantitative data comprised measurements of fish species weight, length, width, and age, as well as average rainfall figures, average temperature figures, and fish catch figures.

A comprehensive field survey was conducted to determine the available fish species in selected areas of Lake Malawi, Lake Malombe, and the Upper Shire River. Fish samples were collected from various locations within these water bodies to ensure a representative dataset. In Lake Malawi, sampling points included Namalaka Beach, Malindi, and the Nsangu/Namiyasi area. For the Upper Shire River, fish were collected at three key points: Liwonde barrage, Mvera beach, and Mangochi Bridge. In Lake Malombe, fish species were sampled from Chapola and Mtambo beach.

The collection of fish catches was facilitated by hiring local fishermen who exclusively used mosquito nets as fishing gear. The choice of mosquito nets was strategic due to their small mesh size, which allows for the capture of a wide range of fish species, including smaller and juvenile fish. The use of mosquito nets was sanctioned by the fisheries department, ensuring compliance with local regulations and ethical considerations.

Fish sorting and species identification were conducted by skilled fish taxonomists from the fisheries department. The identification process was meticulous, involving the manual sorting of fish to the species level. Key morphological features such as fish length (measured in millimeters) and mass (measured in grams) were recorded using a measuring board and an electronic weighing scale, respectively. This detailed data collection enabled the determination of species length frequencies and provided insights into the population structure of different fish species.

In addition to capturing the physical characteristics of the fish, the precise locations where the fish were caught were documented. This georeferenced data allowed for tracing the exact origin of the fish, facilitating a spatial analysis of fish distribution and habitat preferences within the study area. This spatial information was critical for correlating fish population dynamics with specific land use and land cover changes in the catchment area.

The land cover change database was created using data sources from remotely sensed satellite imagery from the Landsat series of satellites (Digital Elevation Model; DEM 30 meters). Main satellite data sources included high-resolution satellite imagery in TIFF format, freely downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and Google Earth. The study area, covering 9,914 km² with 3,844 km² comprising water and marshy areas, was analyzed using a supervised classification method with the maximum likelihood algorithm to ensure accuracy.

The supervised classification method involves selecting training sites for each land cover type to guide the classification algorithm. The maximum likelihood algorithm considers the statistics for each class in each spectral band, assuming normal distribution, and estimates the probability that a given pixel belongs to a specific class. Each pixel is assigned to the class with the highest probability. If the highest probability is below a specified threshold, the pixel remains unclassified. The catchment area was categorized into the following main classes: cultivation, natural forest, agroforest, water and marshy areas, settlement and bare land, and grassland.

Landsat 4, 5 TM, and Landsat 8 images of Path 181; Row 063, covering the study area, were downloaded from the Landsat imagery archive hosted by the USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center using the USGS Globalization Visualization Viewer (GLoVis) tool. These images, acquired on 03-03-2000, 20-06-2005, 19-08-2010, and 08-07-2017, were chosen for their cloud-free quality. Landsat 7 ETM images were not used due to errors that could affect classification. Control points were collected on the ground at specific land use/land cover locations for validation purposes.

The Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM) is a multispectral scanning radiometer carried on board Landsat 4, 5, and 8. The TM sensors collect data in seven bands across the visible, near-infrared, shortwave, and thermal infrared spectral bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, with a spatial resolution of 30 meters and a swath width of 185 kilometers. This data provides nearly continuous temporal resolution of 16 days for Earth observation. The multi-temporal nature of the data allowed for the analysis of land use and land cover changes over the study period from 2000 to 2017. The temporal resolution of 16 days ensures that the same area is imaged frequently, allowing for the detection of changes and trends over time.

The process of classification was validated using ground control points collected during field surveys. These control points provided accurate reference data for different land use and land cover types, ensuring the reliability of the classification results. The integration of satellite imagery with ground-truth data enhanced the accuracy of the land cover maps, enabling a robust analysis of the spatial and temporal dynamics of land use changes in the study area.

3. Results and Discussion

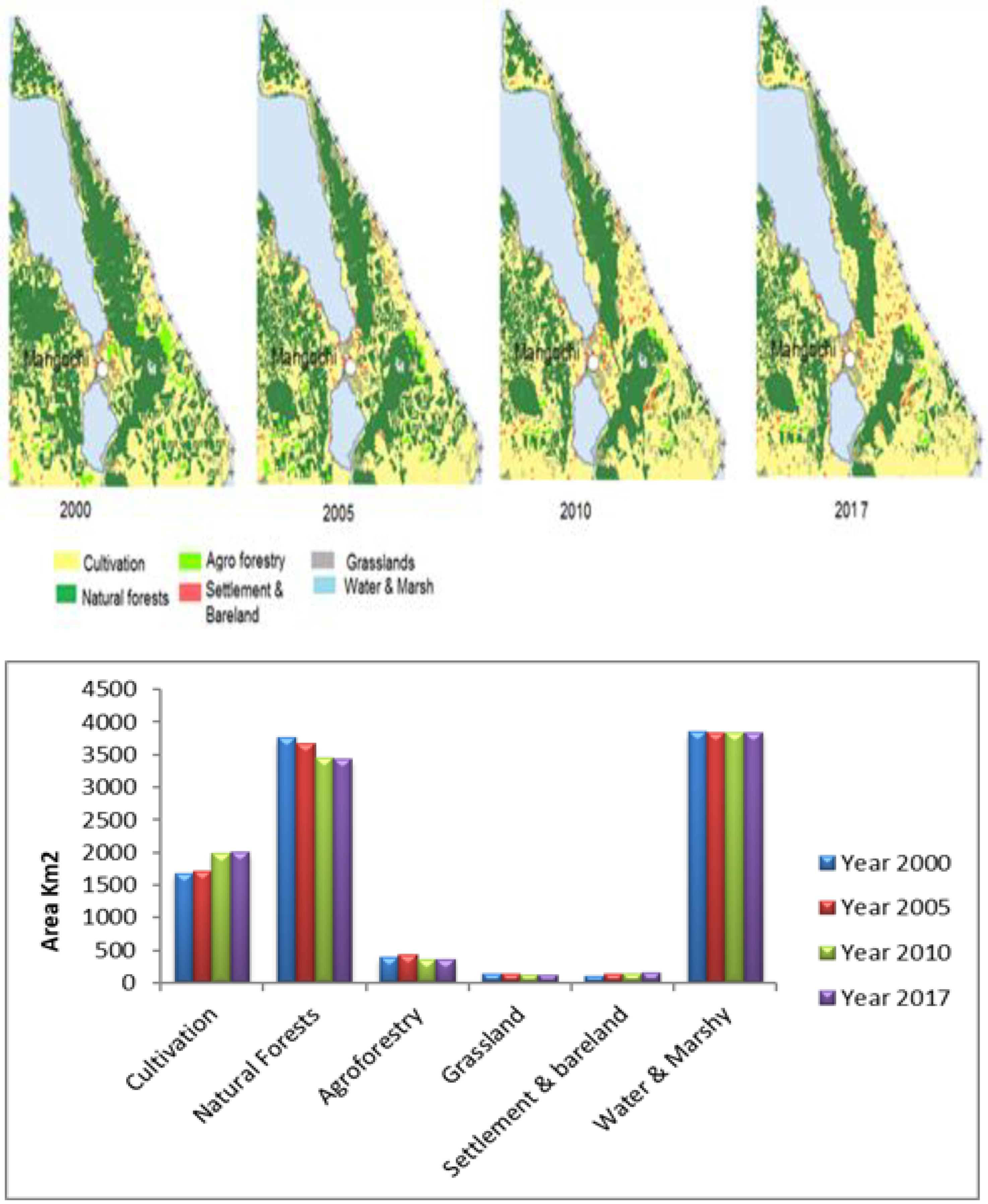

Figure 2 shows the dynamics of land use and land cover in terms of area covered by a particular land use at a certain period and comparing it by the same time to other time series. Cultivation area increased from 2000 to 2017. The natural forest variation was always opposite to agroforestry. From 2000 to 2005, it was noted that there was a decrease in the natural forest and an increase in agroforestry. Nevertheless, there was an increase in the natural forest and a decrease in agroforestry between 2005 and 2010, which could be attributed to efforts by local communities in managing the natural forests. The decrease in grasslands and fluctuation in settlement and bare land from 2000 to 2017 was also noted. The area with water and marshy also slightly decreased.

Figure 2 illustrates the dynamics of land use and land cover (LULC) in the study area from 2000 to 2017. Over this period, significant changes in LULC were observed, particularly an increase in cultivation and settlement areas. These changes showed a strong negative correlation with fish catches during the study period. Statistical analysis at a 0.05% significance level indicated that this correlation was significant (p < 0.05), suggesting that as cultivation and settlement areas expanded in the catchment, fish catches declined. This negative correlation is likely due to the degradation of aquatic habitats caused by increased agricultural activities and urbanization, leading to water pollution and the removal of substrates crucial for fish breeding (Thieme et al., 2010). These results are consistent with findings by Ricciardi and Rasmussen (1999), who noted similar impacts on freshwater biodiversity due to land use changes.

The increase in cultivated land and settlements is often driven by a growing human population, which intensifies the pressure on fish resources (Ricciardi & Rasmussen, 1999). Agricultural runoff containing pesticides and fertilizers can pollute water bodies, causing eutrophication and depleting oxygen levels, which are detrimental to fish health and reproduction (Dudgeon et al., 2006). Additionally, the expansion of settlements results in increased wastewater discharge and habitat fragmentation, further degrading the aquatic environment (Allan & Flecker, 1993).

Conversely, land cover types such as natural forests, agroforests, grasslands, and water and marshy areas showed a strong positive correlation with fish catches. This indicates that as these land cover types decreased, there was a corresponding reduction in fish catches. These natural and semi-natural habitats are crucial for maintaining healthy aquatic ecosystems as they provide essential services such as filtering pollutants, stabilizing sediments, and supplying nutrients that support fish productivity (Olden et al., 2010). These findings align with previous research indicating the importance of natural habitats for sustaining fish populations (Burkhead, 2012).

The preservation of natural forests and agroforests is particularly important as they help maintain water quality and provide habitat complexity that benefits fish breeding and feeding (Wang et al., 2011). Grasslands and marshy areas also play a vital role in maintaining the hydrological cycle and supporting biodiversity. These areas offer refuge and breeding grounds for fish, contributing to higher fish productivity and catches (Burkhead, 2012).

Figure 3 shows a notable decline in fish catches from Lake Malawi and Lake Malombe from 2000 to 2017. The total fish catch was over 4000 tonnes per year in 2000 but gradually decreased to below 2000 tonnes per year by 2017. This declining trend aligns with observations by Trewavas (1983) and Kapute (2018), who attributed it to factors such as overfishing and the use of unregulated fishing gear. Overfishing depletes fish stocks faster than they can replenish, while unregulated practices, including the use of small mesh nets and destructive fishing methods, further exacerbate the problem by capturing juvenile fish and damaging habitats (Al-Ahmadi & Hames, 2009). These findings are similar to those of several studies highlighting the detrimental impacts of fishing practices on aquatic biodiversity.

These findings underscore the importance of sustainable land and water management practices. Conservation efforts should focus on protecting and restoring natural habitats, regulating fishing activities, and implementing land use policies that minimize environmental degradation. Creating conservation buffer zones around water bodies, promoting sustainable agricultural practices, and engaging local communities in resource management can help mitigate the adverse effects of land use changes on fish biodiversity and productivity. Long-term monitoring and community involvement are essential for ensuring the effective conservation and management of these vital ecosystems (Zeinivand & Temme, 2014).

4. Socioeconomic Drivers of Land Use Changes

This study explored the socioeconomic factors driving land use and land cover changes, focusing on population growth, agricultural expansion, and urbanization. Rapid population growth in Malawi has led to an escalating demand for land, primarily for agricultural purposes and settlement, which in turn has resulted in widespread deforestation and habitat fragmentation. As populations expand, more land is cleared for farming, leading to the loss of vital ecosystems that support fish biodiversity.

Agricultural practices, particularly in areas adjacent to water bodies, have significant repercussions for aquatic ecosystems. The intensive use of fertilizers and pesticides contributes to sedimentation and pollution in lakes and rivers, which degrades fish habitats. Nutrient runoff can lead to eutrophication, causing harmful algal blooms that deplete oxygen levels in the water, adversely affecting fish populations (Thieme et al., 2010). These changes highlight the critical need to address the environmental impacts of agricultural expansion and its relationship with fish biodiversity.

Urbanization further exacerbates these issues, as expanding settlements encroach upon natural landscapes. Increased construction and infrastructure development often lead to habitat destruction and fragmentation, which isolates fish populations and reduces genetic diversity. The growing demand for urban infrastructure, such as roads and housing, places additional pressure on land resources, further contributing to the decline of aquatic ecosystems (Allan & Flecker, 1993).

The study also emphasized the indirect effects of socioeconomic activities on fish biodiversity. The rising demand for natural resources, driven by economic growth and population pressures, often leads to unsustainable practices that deplete fish stocks. Overfishing, coupled with habitat degradation from land use changes, results in a compounded negative impact on fish populations. This situation highlights the urgent need for more sustainable land management practices that balance socioeconomic development with environmental conservation.

Moreover, socioeconomic factors often influence local communities' reliance on natural resources. As fish populations decline, communities may turn to more aggressive fishing practices or alternative resource exploitation, perpetuating a cycle of over-exploitation. This dynamic underscores the importance of integrating socioeconomic considerations into conservation strategies to achieve more effective resource management.

To address these challenges, the study advocates for the implementation of sustainable land management practices that consider both human needs and ecological health. This includes promoting agroecological practices that enhance productivity while minimizing environmental impacts and developing urban planning strategies that protect vital habitats. Community engagement and education are also essential in fostering sustainable practices, encouraging local populations to participate in the conservation of their natural resources.

Ultimately, understanding the socioeconomic drivers of land use change is crucial for developing effective policies and management strategies. By addressing the root causes of habitat degradation and promoting sustainable practices, it is possible to mitigate the adverse effects on fish biodiversity and ensure the long-term health of aquatic ecosystems. Future research should focus on exploring the interactions between socioeconomic factors and ecological outcomes to better inform conservation efforts and land use planning.

5. Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the impact of land use and land cover changes on fish biodiversity and catches in the Southeast Arm of Lake Malawi, Lake Malombe, and the Upper Shire River. The findings underscore the critical importance of maintaining natural vegetation and implementing sustainable land use practices to protect fish habitats and support fisheries.

The observed negative correlations between increased agricultural and settlement areas and fish catches highlight the urgent need for interventions that prioritize ecosystem health. Specifically, the degradation of aquatic habitats due to sedimentation and pollution from agricultural runoff has been linked to declining fish populations. This indicates that land use changes driven by population growth and urbanization are exerting significant pressure on aquatic ecosystems.

Conversely, the positive relationships between fish productivity and natural habitats demonstrate that conservation efforts can yield significant benefits for aquatic biodiversity. Areas with intact natural forests, wetlands, and grasslands contribute to healthier ecosystems by providing critical breeding grounds and nutrient-rich environments for fish. This underscores the importance of preserving these habitats as integral components of effective fisheries management.

Overall, the study's results advocate for the integration of land and water management policies that consider the interconnectedness of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Such integration is crucial for developing comprehensive strategies that not only protect fish populations but also promote sustainable agricultural practices. By fostering collaboration among stakeholders, including local communities, policymakers, and environmental organizations, it is possible to create a holistic approach that ensures the long-term health of both fisheries and their surrounding environments.

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the need for immediate action to mitigate the impacts of land use changes on fish biodiversity. Future research should prioritize long-term monitoring to understand the cumulative effects of these changes on aquatic ecosystems. Engaging local communities in conservation efforts and educating them about the benefits of sustainable land and water management will be crucial for the success of these initiatives, ultimately leading to healthier ecosystems and more resilient fisheries.

6. Recommendations

The results of this study underscore the urgent need for integrated land and water management policies that recognize the interconnectedness of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Given the significant impact of land use changes on fish biodiversity, it is essential for policymakers to adopt a holistic approach that addresses the multifaceted challenges posed by agricultural expansion, urbanization, and population growth.

Current policies should be revised to incorporate specific measures aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of land use changes on fish habitats. An integrated management framework would facilitate collaboration among various stakeholders, including government agencies, local communities, and environmental organizations. This collaborative approach can lead to more effective and context-sensitive policies that promote the sustainable use of natural resources.

Enhanced monitoring and regulation of land use practices are critical to ensure compliance with environmental standards. This can be achieved through regular assessments of land use changes and their impacts on aquatic ecosystems. Implementing a robust regulatory framework that includes penalties for non-compliance can deter unsustainable practices. Additionally, establishing clear guidelines for land development near water bodies can help minimize habitat degradation and ensure the protection of critical fish breeding grounds.

Community-based management strategies are essential for fostering local stewardship of natural resources. Engaging local communities in decision-making processes empowers them to take ownership of conservation efforts. Education and capacity-building initiatives can help communities understand the importance of preserving aquatic ecosystems and the long-term benefits of sustainable practices. By involving local populations in monitoring and management, policies can be more effectively implemented and adapted to local conditions.

The implementation of conservation buffer zones around key aquatic habitats is a crucial recommendation from this study. These buffer zones can act as protective barriers that reduce runoff and filter pollutants before they enter water bodies. Establishing these zones not only protects critical fish habitats but also enhances the resilience of ecosystems to external pressures. Such zones can be designed to include native vegetation, which provides essential habitat for wildlife and helps stabilize shorelines.

Promoting sustainable agricultural practices is vital for reducing runoff and pollution that negatively affect fish populations. This can involve advocating for agroecological methods, such as crop rotation, cover cropping, and integrated pest management, which enhance soil health and reduce dependency on chemical inputs. Providing training and incentives for farmers to adopt these practices can lead to improved agricultural productivity while safeguarding aquatic ecosystems.

The study highlights the importance of collaborative research in informing policy decisions. Ongoing research initiatives should focus on assessing the long-term impacts of land use changes on fish biodiversity and the effectiveness of management strategies. Policymakers should work closely with researchers to ensure that policies are grounded in scientific evidence and adaptive management principles.

Ultimately, the integration of these recommendations into policy frameworks can lead to a more sustainable balance between land use and aquatic ecosystem health. As pressures on natural resources continue to grow, it is imperative for policies to evolve in response to emerging challenges. Continuous dialogue among stakeholders, coupled with adaptive management strategies, will be essential to address the complex dynamics between human activities and ecological integrity.

By fostering a proactive approach that incorporates both socioeconomic needs and environmental sustainability, we can ensure the long-term resilience of fish populations and the health of aquatic ecosystems. Future research should further explore innovative policy mechanisms and community engagement strategies to enhance the effectiveness of conservation efforts in the face of ongoing environmental change.

References

- Al-Ahmadi, F., & Hames, A. (2009). Comparison of four classification methods to extract land use and land cover from raw satellite images for some remote arid areas, kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Earth Science, 20(1), 167–191. [CrossRef]

- Allan, J. D., & Flecker, A. S. (1993). Biodiversity conservation in running waters: identifying the major factors that threaten destruction of riverine species and ecosystems. BioScience, 43(1), 32-43. [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.D. (2004). Landscapes and rivers capes: The influence of land use on stream ecosystems. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 35:257–284. [CrossRef]

- Brook, B. W. , Sodhi, N. S., & Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2008). Synergies among extinction drivers under global change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23(8), 453-460. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.E. , Reynolds, J.D. and Allison, E.H. (2008). Sustained by snakes? Seasonal livelihood strategies and resource conservation by Tonlé Sap fishers in Cambodia. Human Ecology 36:835–851. [CrossRef]

- Burkhead, N. M. (2012). Extinction rates in North American freshwater fishes, 1900–2010. BioScience, 62(9), 798-808. [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, D. , Arthington, A. H., Gessner, M. O., Kawabata, Z. I., Knowler, D. J., Lévêque, C.,... & Sullivan, C. A. (2006). Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biological reviews, 81(2), 163-182. [CrossRef]

- Government of Malawi (2010). Malawi State of Environment and Outlook Report, Environmental Affairs Department.

- IPCC. (2007). Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Kapute, F. (2018). The role of the Liwonde National Park in conserving fish species diversity in the Upper Shire River, Malawi. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management 21(2): 132-138. [CrossRef]

- Meybeck, M. (2004). The global change of continental aquatic systems: Dominant impacts of human activities. Water Science and Technology 49:73–83. [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D., M. J. Kennard, F. Leprieur, P.A. Tedesco, K.O. Winemiller, and E. GarcíaBerthou. (2010). Conservation biogeography of freshwater fishes: Recent progress and future challenges. Diversity and Distributions 16:496–513. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, A. and Rasmussen J.B. (1999). Extinction rates of North American freshwater fauna. Conservation Biology 13:1220–1222. [CrossRef]

- Thieme, M. L. , Lehner, B., Abell, R., Hamilton, S. K., Kellndorfer, J., Powell, G., & Riveros, J. C. (2010). Freshwater conservation planning in data-poor areas: An example from a remote Amazonian basin (Madre de Dios River, Peru and Bolivia). Biological Conservation, 143(5), 1111-1123. [CrossRef]

- Trewavas, E. (1983). Tilapiine fishes of the genera Sarotherodon, Oreochromis and Danakilia. London. British Museum (Natural History), 583 p. 34-36.

- Wang, L. Lyons, J. Kanehl, P. and Gatti, R. (2011). Influences of watershed land use on habitat quality and biotic integrity in Wisconsin streams. Fisheries 22:37–41. [CrossRef]

- Zeinivand, H., & Temme, A. J. A. M. (2014). A comparison of supervised, unsupervised and synthetic land use classification methods in the north of Iran. International Journal of Science and Technology, 13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).