Introduction

The Emergency Department (ED) is a specific clinical setting where the real challenge is the need to make rapid decisions about the management of patients in order to arrive at the correct diagnosis and, consequently, the correct treatment, often in the absence of the immediate availability of some instrumental tests or of prior specialist consultation.

Transient neurological deficit (TND), a common neurological condition characterized by a focal and transient loss of brain function [

1,

2], and acute confusional state (ACS), a common clinical neurological/neuropsychiatric disorder with global cognitive impairment and inattention [

3,

4], usually lead patients to be admitted to the ED and represent two of the most common diagnostic challenges for the attending emergency physician.

The clinical symptoms overlap between these different neurological disorders [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] and their short duration, which often resolves on admission to the ED, with the patient being asymptomatic during the clinical examination, represent the main diagnostic challenge for the emergency physician.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA), a transient episode of neurological dysfunction without acute infarction on diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

14], is the neurological disorder that in most cases (80%) underlines a TND [

15]. However, focal seizures, migraine with aura [

15] or other conditions such as metabolic disorders [

16], infections [

2], or drug/toxic abuse and psychogenic disorders [

17] can be considered as alternative causes of TND.

In addition, both stroke mimics [

2,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] and stroke chameleons [

2,

8,

12,

18,

24] need to be considered in patients with TND. In particular, stroke mimics are reported to account for 14.6% of patient admissions to the ED [

19].

Finally, ACS is often associated with the same conditions that cause TND, such as non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), vascular disease, sepsis or fever, metabolic or electrolyte disorders, drug/toxin abuse, and psychiatric disorders [

13].

According to the literature, targeted investigations such as electrocardiography, laboratory tests and neuroimaging, especially cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are necessary to rule out various causes of ACS [

4,

25,

26,

27]. MRI, including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging (FLAIR) and, in some cases, gradient-echo sequences associated with cerebral three-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography, is a mainstay of the diagnostic workup for TND of various origins and, as well as for the ACS, has to be preferred to brain computed tomography (CT) [

2,

28,

29].

However, in real clinical practice, in a setting such as the ED, especially in a primary level hospital, but often also in a secondary and tertiary level hospital, the attending physicians have to make the correct diagnosis in the absence of immediate availability of brain MRI. Furthermore, less than half (39%) of patients with TIA, the most common cause of TND and one of the main causes of ACS, show detectable lesions on DWI [

30,

31].

These limitations lead to the widespread use of alternative diagnostic tools in clinical practice, such as electroencephalogram (EEG), a non-invasive and inexpensive instrumental test that could be performed at the patient’s bedside, but in the absence of universally accepted guidelines [

32,

33] and in the absence of strong evidence in the literature on the contribution of emergent EEG (emEEG) in the differential diagnosis of TND or ACS.

The diagnostic power of EEG in the differential diagnosis of TND has been analyzed in only one previous study [

2], which reported no difference in EEG patterns between TIA, seizure, stroke mimic, stroke chameleon and other diagnoses, while Prud’hon et al. [

13] analyzed the role of EEG in the diagnostic workup of patients with ACS, reporting that this neurophysiological test was a key investigation in the management strategy of ACS in 11% of patients admitted to the ED.

However, both previous studies had some limitations, mainly related to the small number of patients analyzed and the timing of EEG recording, with a median delay of 1.6 and 1.5 days after symptom onset, respectively.

In the current study, we report the emEEG patterns of a large sample of consecutive patients admitted to the ED of a tertiary care hospital for TND or ACS, performed early after symptom onset.

The main aim of our study was to observe the frequency and characteristics of emEEG abnormalities in patients with different neurologic admission symptoms and with different final diagnoses of TND and ACS, and to observe the contribution of emEEG in the differential diagnosis of TND/ACS.

Results

In the present secondary analysis of data from the EMINENCE monocentric retrospective study, we included 603 emEEGs performed on 579 patients of a total of 1018 recruited in the first analysis between 1 January 2023 and 31 December 2023. During their stay in the ED, 24 patients underwent a second EEG. Most emEEGs (n=600; 99.5%) were performed during working hours.

The median age of the cohort was 73 years [IQR 24]. Two hundred and ninety patients (49.2%) were female.

One hundred and twenty-four subjects (21.0%) had a history of epilepsy, 47 of unknown aetiology and 77 of structural aetiology. One hundred and six subjects (18.3%) were taking anti-seizure medication (ASM).

Three hundred and ninety-two patients (67.7%) had no previous brain parenchymal damage. Of the remaining 187 patients, 69 (36.8%) underwent a previous neurosurgical intervention. The most common causes of brain damage were multi-infarct encephalopathy (135 patients; 23.3%), previous ischemic stroke (46 patients; 7.9%), brain tumor (24 patients; 4.1%), haemorrhagic stroke (10 patients; 1.8%) and previous traumatic brain injury (7 patients; 1.2%).

One hundred and nineteen patients (20.5%) were admitted to the ED with metabolic or electrolyte disorders, 141 patients (24.3%) were found to have fever or sepsis, and 13 patients (2.2%) were admitted after drug abuse.

Brain CT was performed in 558 patients (96.4%) and showed acute pathology in 90 patients (15.2%), of which cerebral ischemia was the most common brain damage (14 patients; 2.4%).

Twenty-four patients (3.8%) underwent lumbar puncture, of whom two had results suggestive of central nervous system (CNS) infection.

The demographic characteristics of patients are shown in

Table 1.

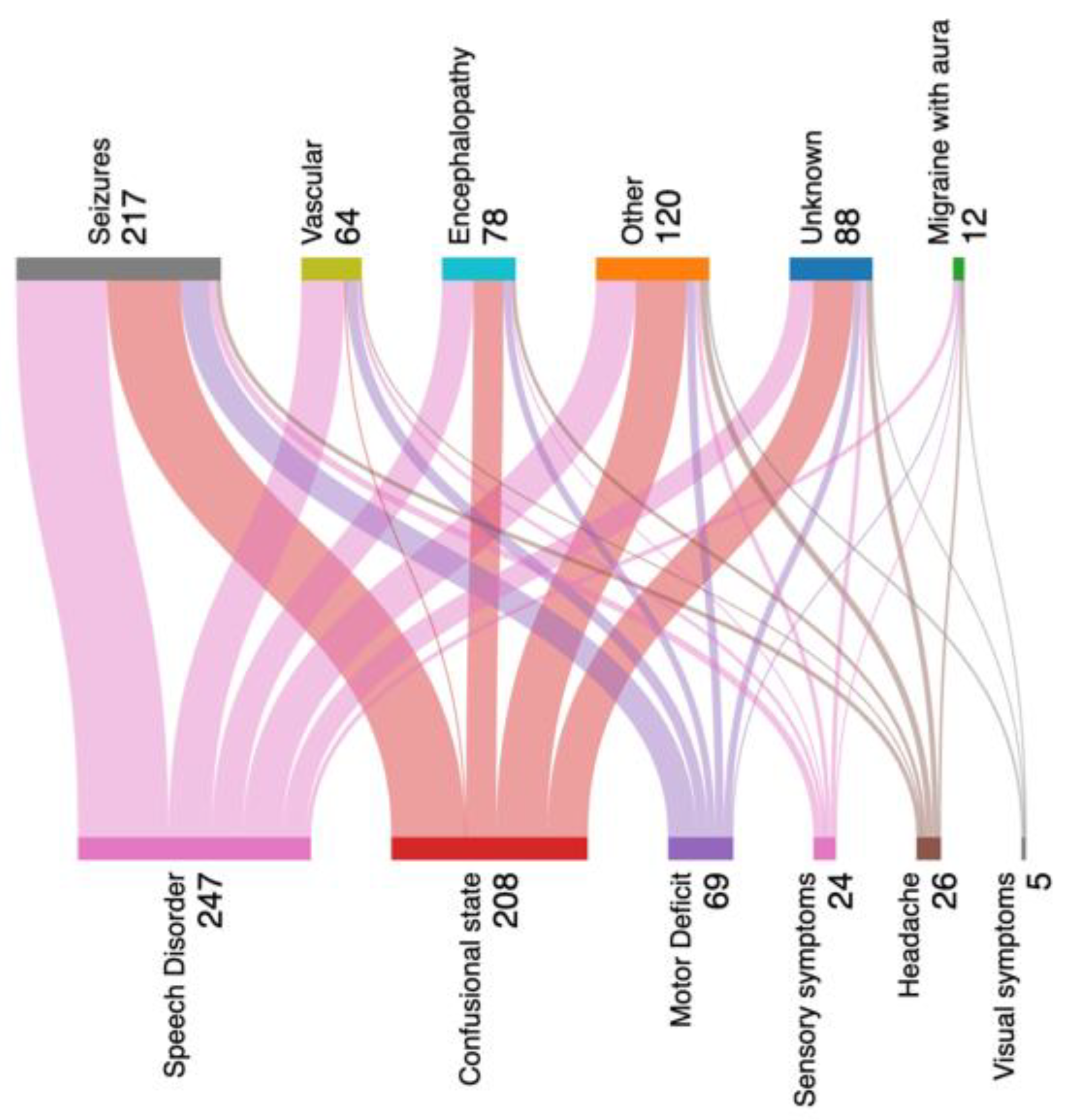

Two hundred and eight patients (35.9%) were admitted to the ED for ACS, 247 (42.6%) had a speech disorder, 69 (11.9%) had motor symptoms, 24 (4.1%) had sensory symptoms, 26 patients (4.5%) had headache associated with one of these other neurological symptoms, and 5 patients (0.8%) were admitted with visual symptoms.

The median duration of symptoms was 60 minutes (IQR 345). Two hundred and three patients (35.1%) still had the neurological symptoms that led to their admission to the ED at the time of their emergency department visit.

The median delay from symptom onset to EEG recording was 350 minutes (5-6 hours) (IQR 675 minutes).

One hundred and seventy-one patients (29.5%) had neurological symptoms that led to admission to the ED when the emEEG was performed, and 135 of them (79%) had an abnormal neurophysiological test. The remaining 408 patients (70.4%) showed remission of neurological signs and symptoms when the emEEG was performed, with 252 subjects (61.7%) reporting an abnormal neurophysiological test.

The demographic characteristics of the patients included, previous neurosurgical intervention (n=61 of 69 patients, 88.4%), sepsis (n=58 of 66 patients, 87.0%), metabolic disorder (n=33 of 39 patients, 84. 6%), previous brain parenchymal damage without previous neurosurgery (n=152 of 187 patients, 81.2%), electrolyte disturbance (n=64 of 80 patients, 80.0%) and fever (n=52 of 65 patients, 80.0%) were the most common predisposing factors for an abnormal EEG.

According to the signs and symptoms on admission, we found an abnormal EEG in 186/247 patients with speech disorder (75.3%), in 47/69 patients with hyposthenia (68.1%), in 131/208 with ACS (62.9%), in 14/26 with headache (53.8%), in 2/5 with visual symptoms (40%), and in 8/24 with hypoesthesia (33.3%). The distribution of abnormal emEEG according to symptom presentation tended to be significant (V di Cramer=0.156).

Table 2 shows a comprehensive list of emEEG characteristics and abnormalities according to neurological signs and symptoms on admission.

An alluvial plot showing the discharge diagnosis compared with the neurological signs and symptoms on admission to the ED in patients who underwent emEEGs is shown in

Figure 1.

According to the alluvial plot, 217 patients were discharged with a seizure, 64 with a vascular disorder, of which 47 subjects were discharged with a TIA, 14 with an atypical stroke [

2] and 3 with a rapidly regressive ischemic attack (RRIA) when an acute infarct was detected on MRI diffusion sequences [

2]. Seventy-eight patients had a final diagnosis of encephalopathy, of which 43 were due to sepsis, 14 to metabolic disturbance, 7 to electrolyte disturbance, 12 to substance abuse and 2 to non-specific fever. One hundred and twenty patients were discharged in the “other” group, which included minor head trauma, focal brain lesions and psychiatric disorders as the cause of the neurological symptomatology that brought the patients to the ED. Twelve patients were discharged with migraine with aura and the remaining 88 subjects were discharged to the ’unknown’ group if the TND/ACS had no defined aetiology or non-neurological cause.

According to the different final diagnoses, we found an abnormal EEG in 186/217 patients with seizures (85.7%), in 58/78 patients with encephalopathy (74.3%), in 39/64 patients with vascular disease (60.9%), in 62/120 patients with other diagnosis (52.1%), in 38/88 patients with unknown diagnosis (43.1%) and in 4/12 patients with migraine with aura (33.3%). The distribution of abnormal emEEG according to final diagnosis was significant (V Cramer=0.26).

Migraine with aura (8/12 patients; 66%) and unknown diagnosis (50/88 patients; 56%) were the final diagnoses with the most normal emEEG.

Table 3 shows a comprehensive list of emEEG characteristics and abnormalities according to the final diagnosis of the patient.

Table 4 shows the number of each abnormal emEEG feature according to the different final diagnoses of the most common neurological signs or symptoms on admission.

The emEEG influenced the initial diagnostic suspicion in 452 (78.1%) patients, confirming the initial diagnosis in 93% (16.1%) and excluding it in 319 (55.1%).

One hundred and eighty-five patients (32%) underwent subsequent hospitalization, 3 (0.5%) refused hospitalization, and the remaining 391 (67.5%) were discharged home from the ED. One hundred and ninety-one patients (33%) presented an EEG within normal limits, and 157 of them (82.1%) were discharged home within 24 hours of admission to the ED.

Discussion

According to our results, speech disorder (75.3%), hyposthenia (68.1%) and ACS (62.9%) were the neurological signs/symptoms on admission to the ED that showed the highest percentage of abnormal emEEG, especially when epileptic discharges were taken into account. Seizures (85.7%) and encephalopathy (74.3%) were the final diagnoses with the highest percentage of abnormal emEEG, particularly epileptic discharges and focal slow waves in patients discharged as seizures and bilateral slow waves and triphasic waves in patients discharged as encephalopathy, regardless of the admission symptoms. The presence/absence of epileptic discharges associated with focal slow waves discriminated between seizures and vascular etiology, especially for the admission symptom of hyposthenia (100% seizures when epileptic discharges were present vs 50% when focal slow waves alone were present). Instead, migraine with aura (66%) and unknown diagnosis (56%) was the final diagnosis with the most normal emEEG.

The rapid timing of the emEEG recording compared to the patient’s admission to the ED (median delay 5-6 hours) allowed us to perform the neurophysiological test in 29.5% of patients who were still symptomatic, of whom 79% had an abnormal emEEG.

Transient neurological deficits and ACS are usually a diagnostic challenge, especially for ED physicians who have to make quick decisions about patient management.

Brain MRI is the instrumental test that can best identify part of the differential diagnosis of ACS and especially of TND and must be preferred to brain CT [

28].

However, in real clinical practice, especially in a setting such as the ED, clinicians must make the correct diagnosis without the immediate availability of this instrumental test, bearing also in mind that however only less than half (39%) of patients with TIA, the most common cause of TND and one of the main causes of ACS, have detectable lesions on DWI [

30,

31]. These limitations have led to the widespread use of alternative instrumental tests, such as emEEG, a non-invasive and inexpensive diagnostic tool that can be performed at the patient’s bedside.

EEG, which allows functional exploration of the brain, is considered complementary to neuroimaging in the detection of different neurological conditions, such as NCSE or encephalopathy of different aetiology, and its usually rapid availability, even in an emergency context, has led to a wide use of this diagnostic tool in the ED, but in the absence of universally accepted guidelines [

32,

33] and in the absence of strong evidence in the literature on the contribution of emEEG in the differential diagnosis of TND and ACS.

In fact, only a few previous studies [

2,

13,

17,

47,

48,

49] have analysed the diagnostic power of emEEG in patients with TND or ACS.

In more detail, only Prud’hon et al. [

13] analysed patients with ACS and reported that emEEG was a key examination in the management strategy of ACS in 11% of patients admitted to the ED, with limitations regarding the small sample size and the long delay between symptom onset and neurophysiological test recording (mean 1.5 days).

Regarding the studies on TND, three of them [

47,

48,

49] considered a single aetiology of TND. The study by Seo-Young Lee et al. [

47] analysed post-traumatic TND, Ji Hoon Phi et al. [

48] reported data on post-operative TND, while Madkour et al. [

49] analysed patients with TIA.

In another study [

17], Vellieux et al. analysed the role of spectral EEG analysis in the differential diagnosis of TND and reported a discriminative EEG power in migraine with aura compared to TND of other origins. However, in an emergency setting such as the ED, where clinicians need rapid information to make prompt decisions about patient management, spectral analysis could not be used as an emergency tool, requiring more time to be performed compared to a normal interpretation of emEEG results according to ACNS EEG terminology [

38]. In addition, this study had other limitations related to the small sample analysed and the timing of the emEEG recording, including patients with TND symptom onset within the previous seven days.

At the same time, Madkour et al. [

49] also reported the discriminative power of EEG spectral analysis compared to conventional EEG in a small sample of patients with TIA.

To date, the only previous study analysing the diagnostic power of conventional emEEG in the differential diagnosis of TND reported no difference in EEG patterns between TNDs of different origins [

2]. The authors reported that the EEG was abnormal in 42% of cases and that focal slow waves were the most common finding. However, this EEG pattern was found in all diagnostic groups and therefore did not allow an aetiological orientation. However, this previous study also had limitations related to the small number of patients analysed and the timing of the EEG recording, with a median delay of 1.6 days after symptom onset, suggesting that it may be less informative than an emEEG performed in the first few hours. The study by Lorenzon et al. [

2] showed the same limitations as the paper by Vellieux 2021 et al. [

17], as both studies were performed on the same sample of patients.

In the current study, we recruited all consecutive patients admitted to the ED of our hospital who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and who underwent emEEG, including both neurophysiological tests recorded during daily clinical practice and those performed outside hospital hours.

The power of the present study was mainly represented by the large sample analysed and the rapid timing of the EEG execution compared to the symptom onset, with a median recording time of 350 min (between 5 and 6 hours), which allowed us to perform the neurophysiological test when the patient was still symptomatic in 29. 5% of subjects, a result very different from previous studies [

2,

13], and which allowed us to obtain a very high percentage of abnormal EEGs: 79% in patients still symptomatic, 61.7% in patients with resolution of the neurological symptoms on admission.

Another strength of our study was the inclusion of patients with both TND and ACS in the analysis. Indeed, the frequent overlapping of clinical symptoms between these different neurological disorders [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], and the assumption that the underlying aetiologies are often the same, can hinder the correct diagnostic workup, especially in the ED setting, where attending physicians usually have to make rapid decisions about the diagnostic-therapeutic management of patients, often in the absence of immediate availability of some instrumental tests, such as brain MRI, or prior neurological or neurosurgical consultation.

Speech disorder, ACS and hyposthenia were the presenting neurological signs/symptoms with both high emEEG demand and high percentage of abnormal emEEG, especially when epileptic discharges were taken into account. More specifically, seizures, periodic discharges or epileptic discharges were never reported in patients with visual symptoms and were reported in only one patient for both sensory disturbances and headache associated with speech disorder. This result is important because emEEG is usually requested to confirm an epileptic suspicion as the cause of symptoms of access to the ED and, according to our data, hyposthenia, speech disorder and ACS were the presenting neurological signs/symptoms for which emEEG was most useful when seizure was considered in the differential diagnosis.

At the same time, seizure was the most commonly reported final diagnosis for all these three most frequent admission symptoms, followed by vascular disease for speech disorder and hyposthenia.

Although encephalopathy was not one of the most frequent final diagnoses in patients with these three preceding neurological signs/symptoms, it was the discharge diagnosis most associated with abnormal emEEG after seizure, especially for ACS and speech disorder. In particular, encephalopathy was the only final diagnosis, other than seizures, in which the emEEG could show a specific abnormal pattern, the triphasic waves, which allowed not only to exclude an epileptic origin of TND/ACS, but also to suggest an alternative aetiology.

According to our results, 37.4% of all patients were discharged with seizures, 13% with encephalopathy and 11% with vascular disease. These last two percentages were very similar despite the fact that while encephalopathy is a diagnosis that can be detected by emEEG, this neurophysiological test should not be the gold standard for detecting vascular disease. The main explanation for this similar percentage of discharge etiology could be the atypical presentation of some vascular diseases, as observed in our results (21.8%), characterized by march of symptoms, multiple stereotyped episodes, isolated speech disorder, tingling sensation or rigid postures. This percentage may seem high compared to the diagnosis of TIA (70%), but it must be borne in mind that the present sample of patients is limited to those who underwent an emEEG and in whom an epileptic aetiology was therefore suspected.

Seizures were the final diagnosis in which epileptic discharges were most frequently reported, with a percentage of 37.7%, a result in line with previous literature [

50,

51], and their presence contributed significantly to the final diagnosis of seizures, regardless of the admission symptom (hyposthenia, speech disorder or ACS). According to our results, the focal slow-wave EEG pattern was also significantly associated with the final diagnosis of seizures when speech disorder and ACS were the admission symptoms. In these cases, we believe that almost a second EEG may be necessary to consider these EEG changes as an expression of a postcritical state rather than related to another aetiology such as vascular disease.

With regard to vascular disease, we also reported that it was the second most common final diagnosis after seizure when hyposthenia and speech disorder were the presenting symptoms. In these cases, the presence/absence of epileptic discharges associated with focal slow waves allowed us to discriminate between the two aetiologies of seizures and vascular disease, especially for hyposthenia (100% seizures when epileptic discharges were present vs. 50% when focal slow waves alone were present).

Overall, the analysis of our results showed that emEEGs influenced the initial diagnostic suspicion in 452 (78.1%) patients, confirming the initial diagnosis in 93/579 (16.1%) and excluding it in 319/579 (55.1%). This is a result of great clinical importance because, in a specific clinical setting such as that of the ED, where the real challenge is the need to make rapid decisions about the management of patients, often in the absence of the immediate availability of some instrumental tests or of prior specialist consultation, not only the confirmation but also the exclusion of the initial diagnosis could be of great importance in achieving the correct diagnosis and, consequently, the correct treatment.

Finally, migraine with aura was the final diagnosis with the most normal emEEG (66%), followed by unknown origin (56%), characterized by a non-neurological aetiology causing TND/ACS or by an undefined aetiology. Regarding the admission signs/symptoms, although we are aware of the preliminary nature of our results given the very small sample of patients with visual disturbance, we reported that none of them showed epileptic discharge and none of them was discharged as a seizure. With regard to sensory disturbance and the group of patients who also had headache, only one patient had epileptic discharge for both symptoms, compared with 8 and 5 patients discharged as seizure respectively. These results suggested that the usefulness of the emEEG could be limited when these three previous admission signs/symptoms or when migraine with aura and the unknown origin as suspected diagnosis were concerned. This is an important point, particularly for primary and secondary hospitals where the availability of emEEG is limited and resources are scarce in front of the need of highly qualified staff.

Our study has some limitations. The main limitation of our study is the classification of the patients. An emEEG was often requested to confirm or exclude epileptic seizures as the cause of the neurological symptoms presenting to the ED, or the patients who had an emEEG were those in whom the diagnosis of TND or confusional state was uncertain. In addition, although experts in vascular disorders, epilepsy and migraine participated in the classification, multiple aetiologies were possible and some patients may have been misclassified, especially because our evaluation is limited to discharge from the ED and we have no subsequent outpatient neurological follow-up. In particular, 88 patients remained without a diagnosis at the end of their medical care. However, we did not find a better classification than the combination of clinical, biochemical and instrumental data, and this represents the daily challenge of emergency physicians.

In addition, given the retrospective nature of the research, clinical and instrumental information was collected from medical records and may have been incomplete.

In addition, although our sample of patients was significantly larger than previous studies, we were able to include a limited number of subjects with some of the presentation signs/symptoms (sensory and visual disturbances or symptoms associated with headache), making our results preliminary, at least for this category of patients.

Furthermore, this study was conducted in a tertiary hospital where at least two or three neurophysiological technicians and one EEG expert neurologist/neurophysiologist per day were exclusively dedicated to recording and interpreting emEEGs during their working hours. We are aware that, in clinical practice, this daily work organization has made it possible both to reduce the time taken to perform emEEGs after patient admission and to cope with the large number of requests for emEEGs, many of which came from the ED department, and thus to collect the current large sample of patients. We also recognize that this daily work organization could not be extended to primary and secondary hospitals, where the availability of emEEG is limited. In addition, our sample, recruited in a tertiary teaching hospital, included mainly complex and severe cases that may not fully represent the spectrum of cases in smaller hospitals, limiting the generalizability of our work.

In conclusion, this study, which included a large sample of subjects with a rapid timing of EEG performance compared to symptom onset and limited to emEEGs performed in the ED, was mainly helpful in establishing the final diagnosis of seizures and encephalopathy, especially when speech disorder, hyposthenia and ACS were the presenting neurological signs/symptoms. In addition, the presence/absence of epileptic discharges associated with focal slow waves allowed differentiation between seizures and vascular etiologies, especially for the admission symptom of hyposthenia. Migraine with aura and unknown diagnosis was instead the final diagnosis with the most normal emEEG. Further multicentre prospective studies with large samples, especially for some of the admission signs/symptoms such as sensory and visual disturbances and headache, and restricting the evaluation of emEEGs performed in the ED setting, are needed to increase the robustness and generalizability of our findings. However, these preliminary results should encourage clinicians to request an emEEG as soon as possible, mainly after the onset of speech disturbance, hyposthenia and ACS, especially if of short duration.

Author Contributors: MS, AN, AG and BP conceived the study and its design. MS, AN and AG managed its coordination. MS drafted the manuscript and developed the methodology. MS, MTV and CI performed data collection. FL and AG performed statistical analysis. MS, AN, AG, PN, BP, PN critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.