Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

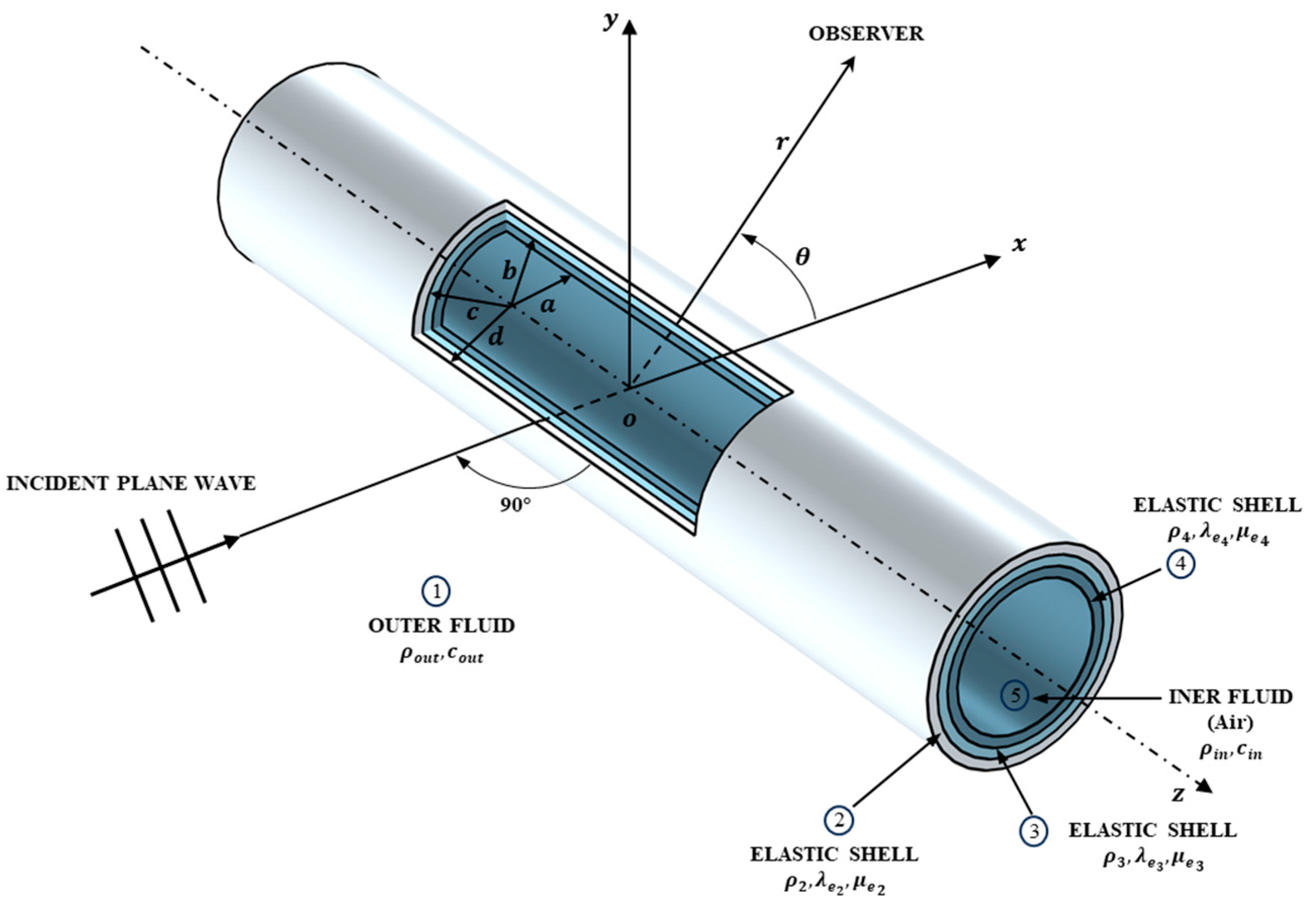

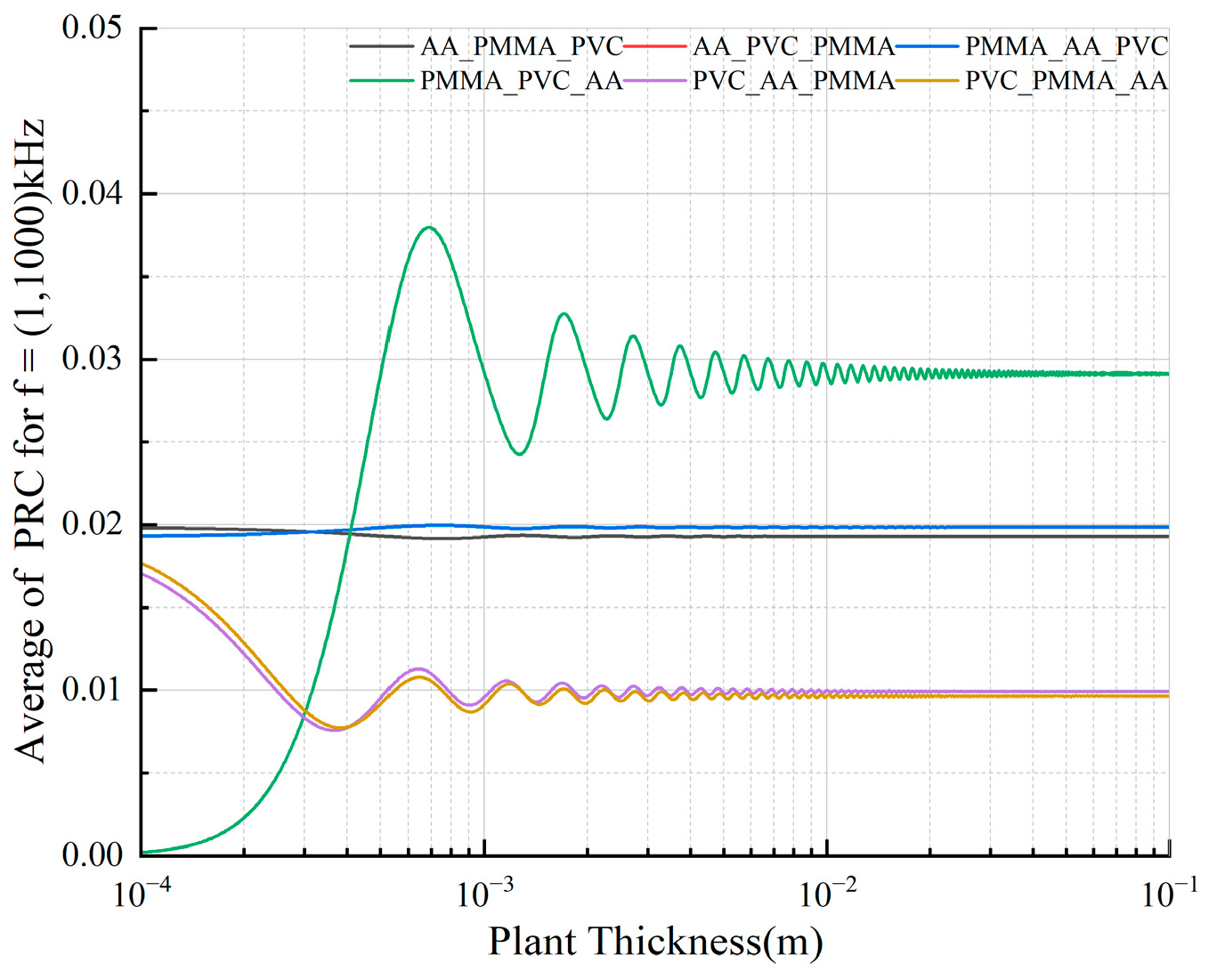

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

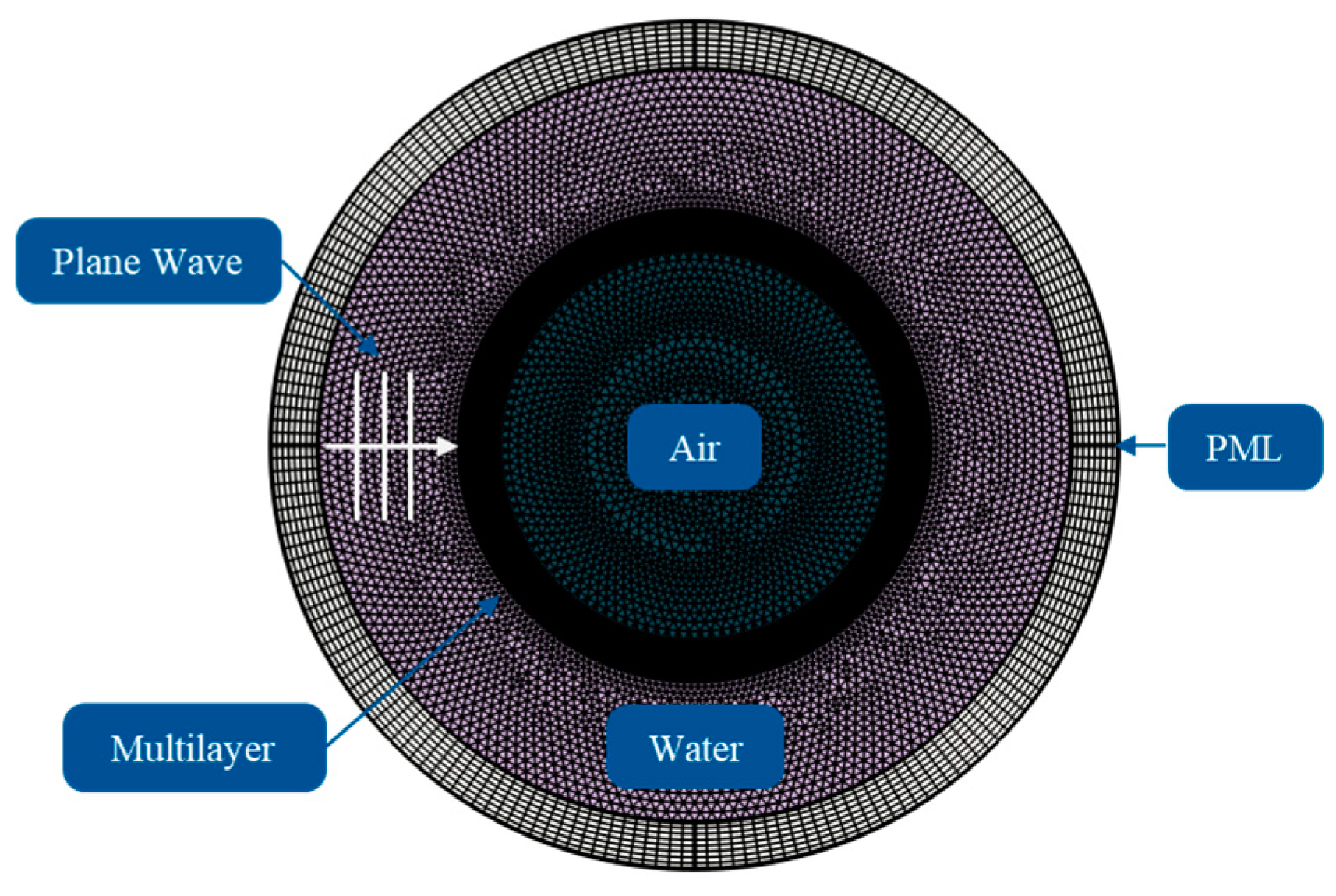

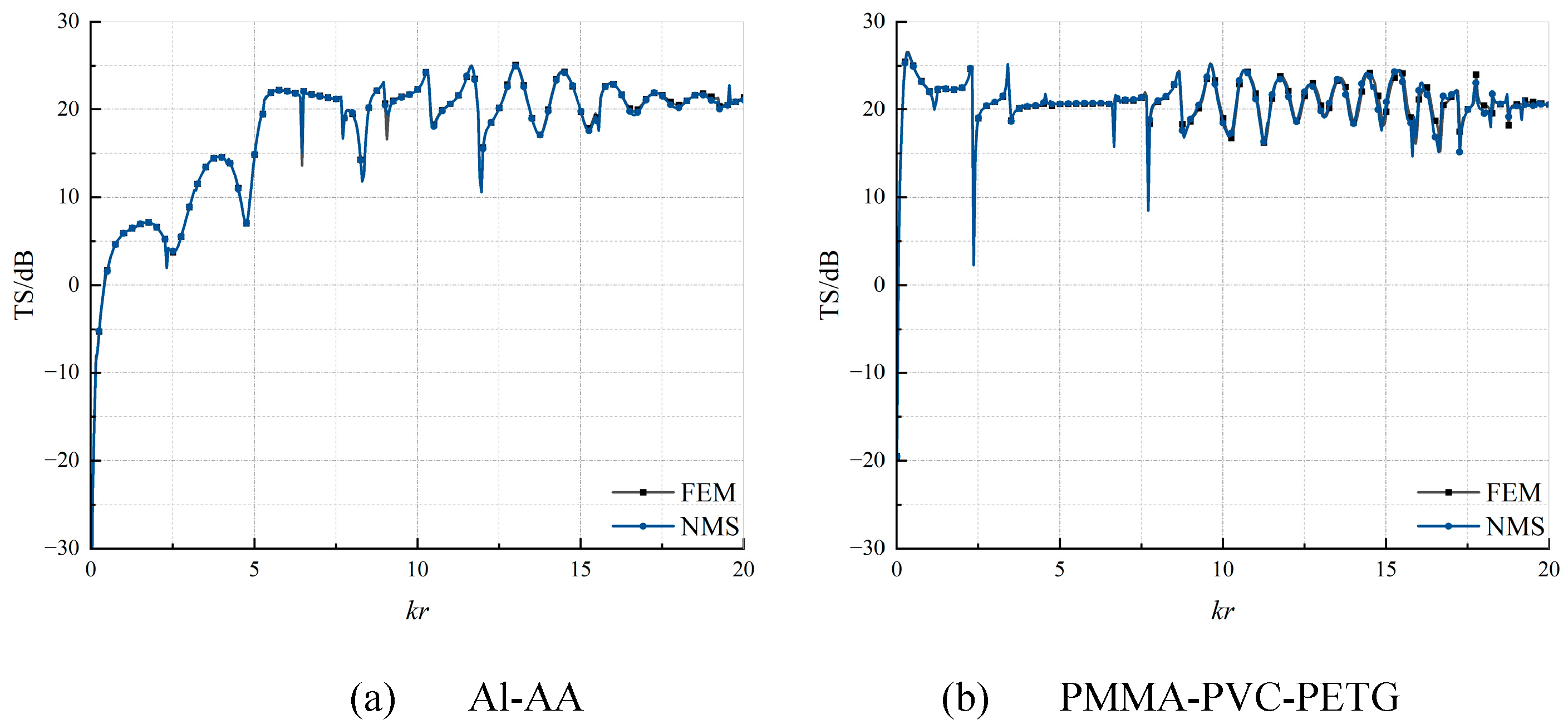

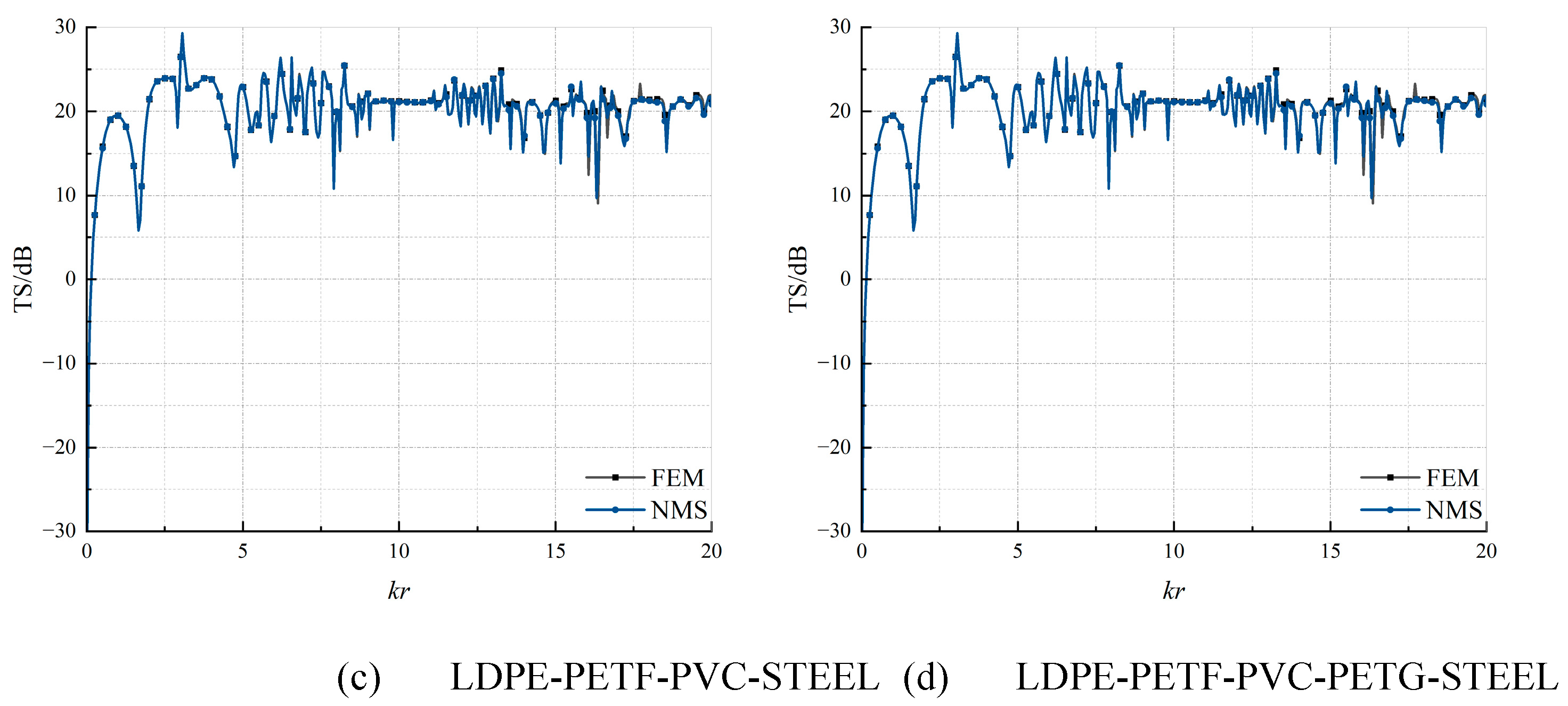

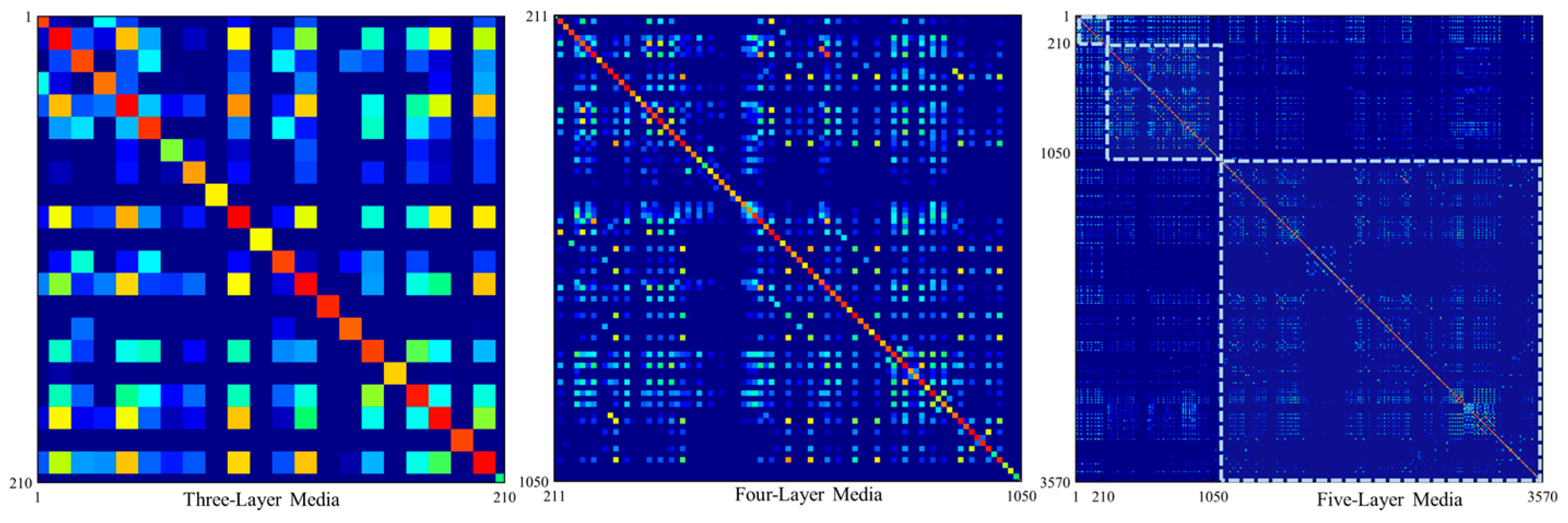

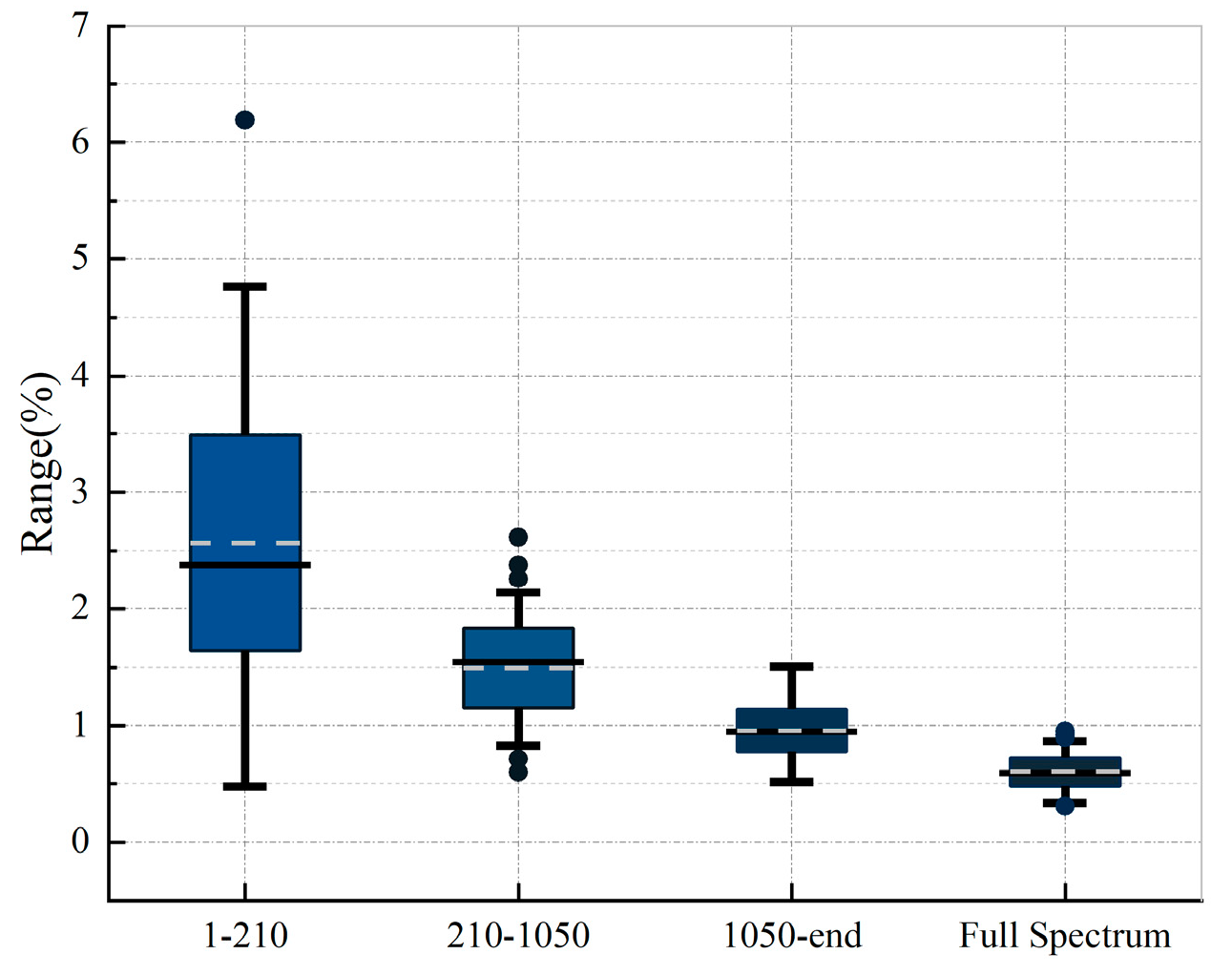

2.2. Numerical Verification

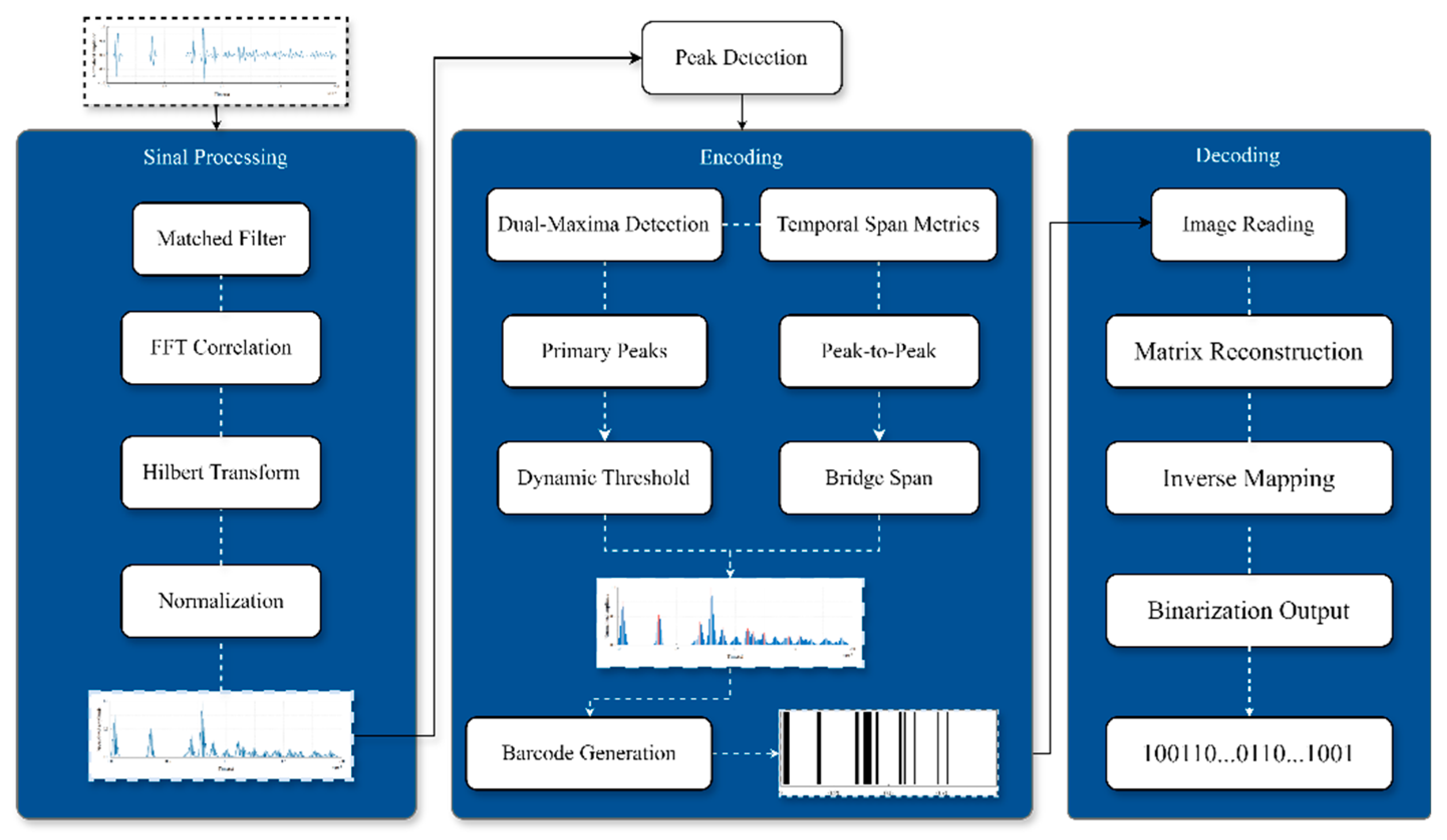

2.3. AlD Tag Generation Workflow

3. Verifications and Results

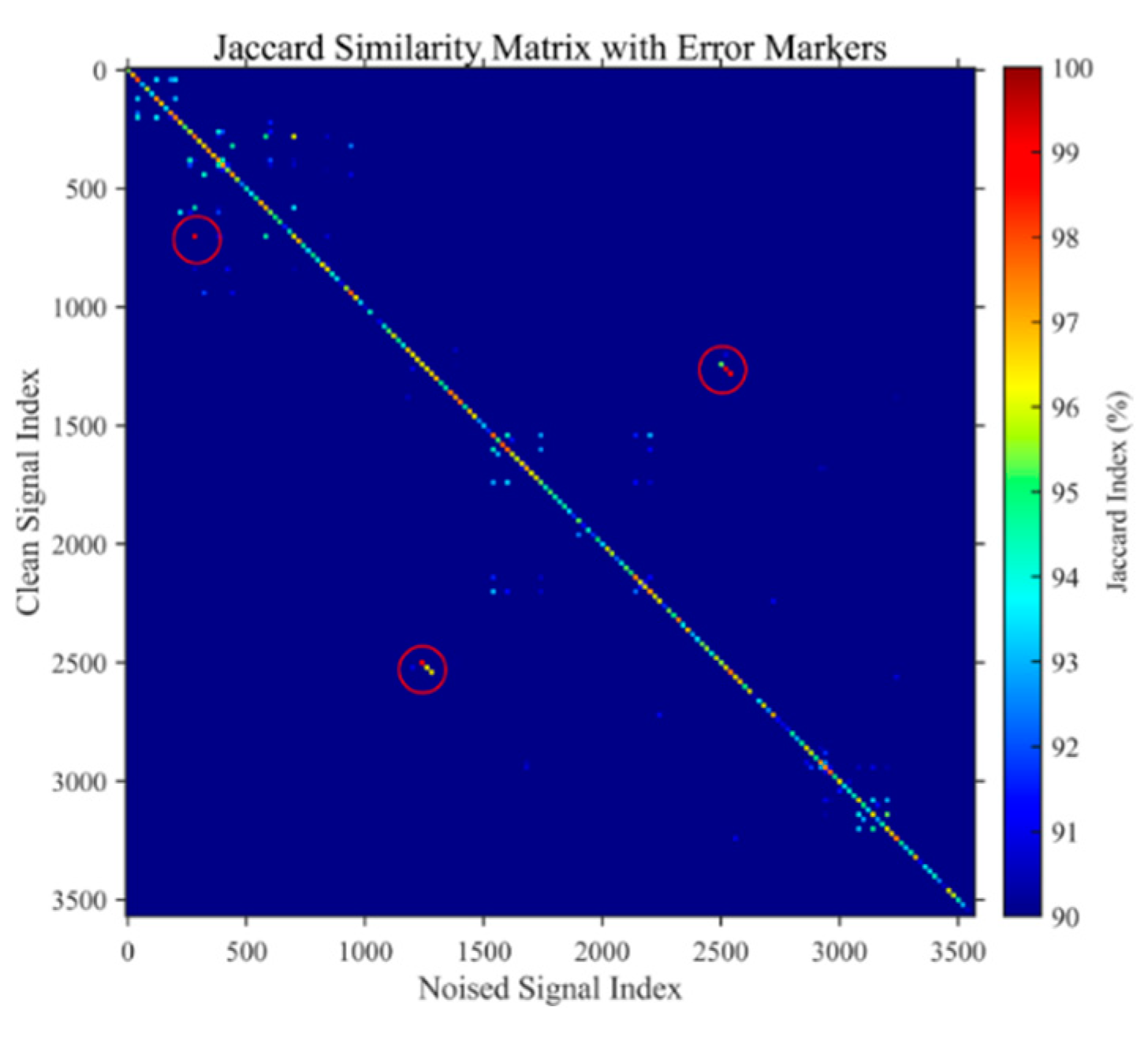

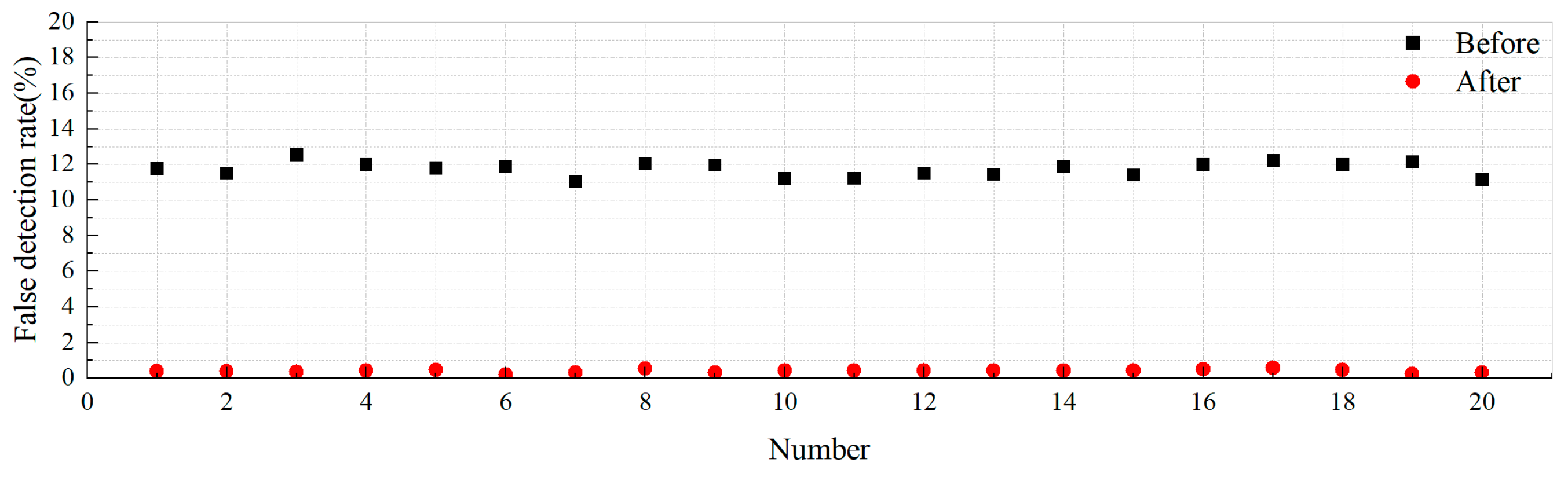

3.1. Effectiveness of AID Tags

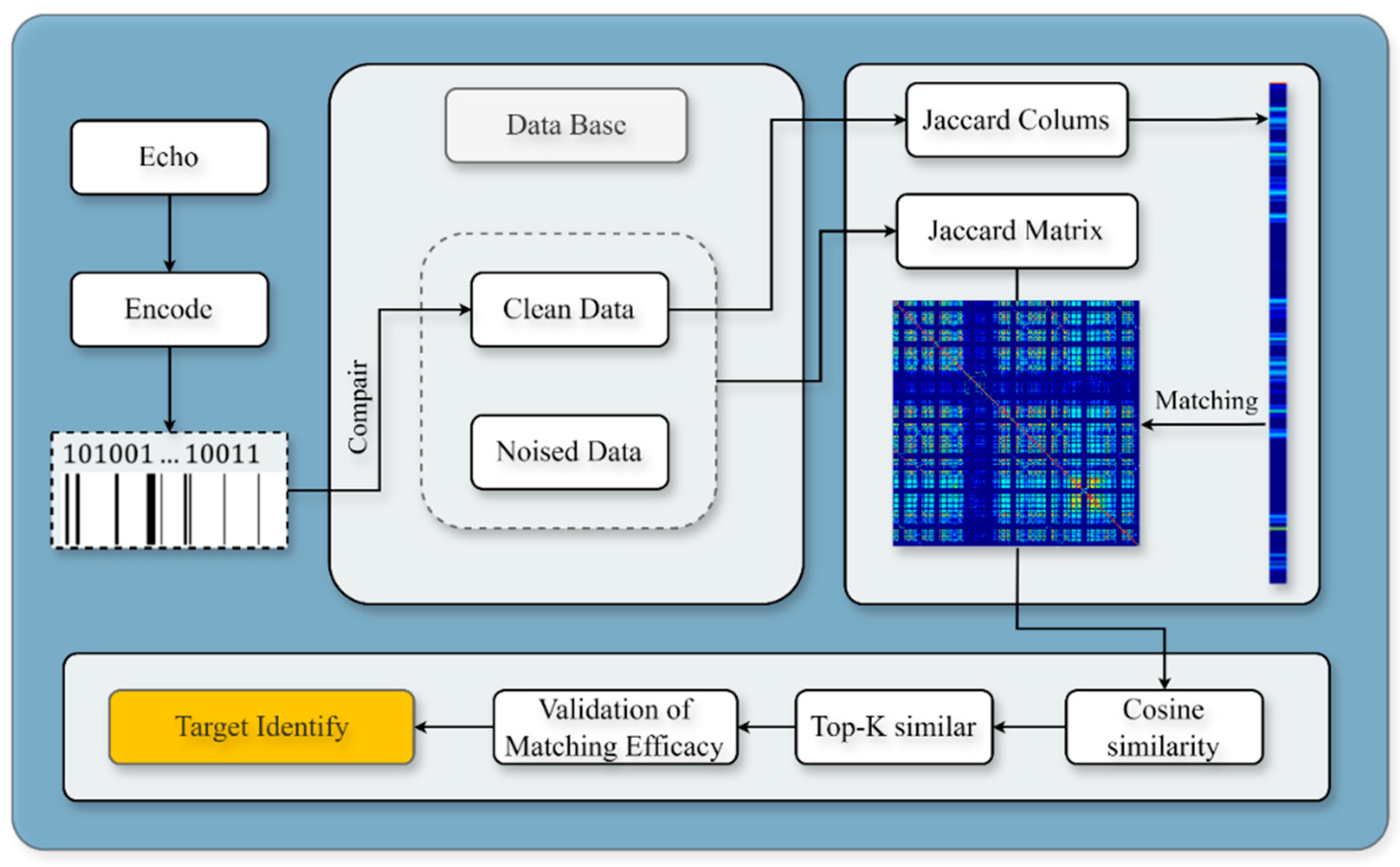

3.2. Target Recognition Methodology

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Wernli R, L. AUV commercialization-who's leading the pack?[C]//Oceans 2000 Mts/ieee Conference and Exhibition. Conference Proceedings (cat. No. 00ch37158). IEEE 2000, 1, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Xiao Y, Li T. A survey of autonomous underwater vehicle formation: Performance, formation control, and communication capability[J]. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 815–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussen C M G, Diniz P S R, Campos M L R, et al. A survey of underwater wireless communication technologies[J]. J. Commun. Inf. Sys 2016, 31, 242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Maurelli F, Krupiński S, Xiang X, et al. AUV localisation: a review of passive and active techniques[J]. International Journal of Intelligent Robotics and Applications 2022, 6, 246–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García J, Gómez-Espinosa A, Cuan-Urquizo E, et al. Autonomous underwater vehicles: Localization, navigation, and communication for collaborative missions[J]. Applied sciences 2020, 10, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin J, Li M, Li D, et al. A survey on visual navigation and positioning for autonomous UUVs[J]. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulinas J, Petillot Y, Salvi J, et al. The SLAM problem: a survey[J]. Artificial Intelligence Research and Development 2008, 363, 371. [CrossRef]

- Jung J, Li J H, Choi H T, et al. Localization of AUVs using visual information of underwater structures and artificial landmarks[J]. Intelligent Service Robotics 2017, 10, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish A, Nichols B, Trivett D, et al. Passive underwater acoustic tags using layered media[J]. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2019, 145, EL81–EL89.

- Satish A, Trivett D, Sabra K G. Omnidirectional passive acoustic identification tags for underwater navigation[J]. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2020, 147, EL517–EL522. [CrossRef]

- Jalal A S, A. Passive RFID Tags[J]. Wulfenia Journal 2015, 22, 415–435. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj A, Allam A, Erturk A, et al. Ultrasound-Powered Wireless Underwater Acoustic Identification Tags for Backscatter Communication[J]. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. [CrossRef]

- Islas-Cital A, Atkins P, Gardner S, et al. Performance of an enhanced passive sonar reflector SonarBell: A practical technology for underwater positioning[J]. Underwater Technology 2013, 31, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Fan J, Huang J, et al. Passive underwater acoustic barcodes using Rayleigh wave resonance[J]. Journal of Applied Physics 2022, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish A, Sabra K G. Passive underwater acoustic identification tags using multi-layered shells[J]. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2021, 149, 3387–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somaan N, Bhardwaj A, Sabra K G. Passive acoustic identification tags for marking underwater docking stations[J]. JASA Express Letters 2024, 4.

- Ding D, Chen C X, Kong H M, et al. Acoustic encoding of high-frequency time-domain echoes from layered elastic spherical shells in water[J]. Applied Acoustics 2023, 42, 781–791. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Fan J, Wang B, et al. Acoustic barcode based on the acoustic scattering characteristics of underwater targets[J]. Applied Acoustics 2022, 189, 108607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunaurd G, C. Sonar cross section of a coated hollow cylinder in water[J]. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1977, 61, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N. A Time Frequency Approach to Blind Deconvolution in Multipath Underwater Channels[D]. Universidade do Algarve (Portugal), 2001.

- Wenz G, M. Acoustic ambient noise in the ocean: spectra and sources[J]. The journal of the acoustical society of America 1962, 34, 1936–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, P. Approximating the Shapiro-Wilk W-test for non-normality[J]. Statistics and computing 1992, 2, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas E, Wang Z. Performance prediction of underwater acoustic communications based on channel impulse responses[J]. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag S, Kumar S K, Tiwari M K. An efficient recommendation generation using relevant Jaccard similarity[J]. Information Sciences 2019, 483, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu D, Li Q, He X, et al. Preparation of highly dewetted porous steel for shallow water AUV based on laser ablation method[J]. Applied Surface Science 2024, 652, 159261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N. A Time Frequency Approach to Blind Deconvolution in Multipath Underwater Channels[D]. Universidade do Algarve (Portugal).

- Efron B, Tibshirani R J. An introduction to the bootstrap[M]. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1994.

- Huang M, Chen D, Feng D. The Fruit Recognition and Evaluation Method Based on Multi-Model Collaboration[J]. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomavicius G, Zhang J. Classification, ranking, and top-K stability of recommendation algorithms[J]. INFORMS Journal on Computing 2016, 28, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material names | Density |

Young's modulus |

Poisson's ratio |

Longitudinal

velocity |

Characteristic impedance )(megarayleighs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 1000 | / | / | 1480 | 1.48 |

| Air | 1.2 | / | / | 344 | 0.41e-3 |

| Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) |

1180 | 2.8 | 0.38 | 2108 | 2.49 |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | 1400 | 3 | 0.38 | 2003 | 2.80 |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) |

2200 | 0.4 | 0.37 | 567 | 1.25 |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol-modified (PETG) | 1270 | 2 | 0.37 | 1669 | 2.12 |

| High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | 970 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1820 | 1.77 |

| Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) | 910 | 0.1 | 0.45 | 646 | 0.59 |

| Acrylic Acid (AA) | 1190 | 3.2 | 0.35 | 2078 | 2.47 |

| Aluminum (Al) | 2700 | 70 | 0.33 | 4032 | 10.89 |

| Structural steel | 7850 | 200 | 0.3 | 5856 | 45.97 |

| PMMA-PTFE-LDPE |  |

|

|

| PMMA-LDPE-PTFE |  |

|

|

| PTFE-PMMA-LDPE |  |

|

|

| PTFE-LDPE-PMMA |  |

|

|

| LDPE-PMMA-PTFE |  |

|

|

| LDPE-PTFE-PMMA |  |

|

|

| Comparison Data | MJI (%) |

|---|---|

| PMMA-PTFE-LDPE | 99.02 |

| PMMA-LDPE-PTFE | 98.24 |

| PTFE-LDPE-PMMA | 98.71 |

| PTFE-PMMA-LDPE | 98.27 |

| LDPE-PMMA-PTFE | 97.58 |

| LDPE-PTFE-PMMA | 97.40 |

| Mean | 98.20 |

| Structural Steel MJI (%) | Aluminum MJI (%) |

|---|---|

| 98.54 | 98.76 |

| 98.31 | 98.24 |

| 98.97 | 98.60 |

| 98.64 | 98.73 |

| 97.17 | 96.98 |

| 97.61 | 97.92 |

| 98.21(mean) | 98.21(mean) |

| Number of material layers | Cylinder radius | quantity |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.25 | 210 |

| 4 | 0.26 | 840 |

| 5 | 0.27 | 2520 |

| Number of material layers | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 95.67 | 96.11 |

| 4 | 95.03 | 95.28 |

| 5 | 94.46 | 94.60 |

| All | 94.70 | 94.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).