1. Introduction

In many regions globally, ruminant livestock production is a vital source of income and food for people. However, it also significantly contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, primarily through enteric methane (CH

4) production. Enteric fermentation, the process by which methanogenic archaea in the rumen produce CH₄ during digestion, accounts for over 90% to CH

4 emissions from livestock sector [

1]. This represents approximately 40% to total agricultural GHG emissions, with annual emissions from ruminants estimated between 80 and 95 million tons of CH

4 [

2]. Addressing rumen CH₄ emissions presents a viable strategy for mitigating climate change. Moreover, CH

4 emissions represents an energy loss for ruminants, ranging from 5 to 15% of feed energy, depending on diet composition and intake levels [

7,

8]. Consequently, reducing these emissions could enhance the efficiency of animal production systems while benefiting the environment. Precisely, quantifying methane production establishes a foundation for assessing the effectiveness of emission reduction initiatives and facilitates the establishment of achievable targets in this topic [

3,

4]. This underscores the importance of developing and applying precise methodologies for estimating CH₄ emissions in ruminant systems.

Over the past few years, some

in vivo and

in vitro techniques were developed to measure total gas production (GP), dry matter digestibility, neutral detergent fiber (NDF) degradability and methane production from different feedstuffs for ruminants.

In vivo techniques that involve the use of animals have always been considered gold standard methods and are useful to estimate methane production. Several techniques have been developed to measure methane emissions in ruminants. The respiration chamber (RC) remains a reference method [

5,

6], where an animal is placed in a chamber, and gas exchange is monitored by comparing air composition before and after ventilation. Another widely used method is the sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) tracer technique, where a capillary tube collects gas from the animal’s nose while SF6 is released from the rumen, and gas concentration is measured using gas chromatography [

7,

8] while emission is calculated by the equation used by Johnson et al. [

8,

9]. The GreenFeed (GF) system trains animals to approach a feeding station that captures their breath emissions [

10,

11]. Other methods include the sniffer method [

3] during milking, ventilated hoods [

12] for capturing gases from the head, and a facemask system [

13] connected to a gas analyzer. Some of the disadvantages of the

in vivo techniques are that they are expensive, laborious, and time-consuming. Furthermore, their ethical challenges are significant, primarily due to their reliance on animal testing. Moreover, as the animal is in a stressful environment it is extremely difficult to apply any feed manipulation experiment. Even though

in vivo methods are the gold standard in determining methane production, they are unable to explain the kinetics of methane production.

As public interest in animal welfare grows, scientific research increasingly focuses on developing less invasive methods, such as

in vitro techniques, to accurately measure methane production by ruminants [

14]. These methods not only minimize the impact on animals but also provide precise and detailed results. Most

in vitro techniques are based on the two-stage method developed by Tilley and Terry's ([

15]), which simulates rumen conditions such as temperature, pH, and anaerobic environment. This approach uses rumen inoculum (strained rumen fluid), a buffer to maintain stable pH, and a nutrient-rich medium to support the growth and activity of ruminal microorganisms.

The end products of fermentation, such as total gas, methane, and volatile fatty acid production, are crucial for understanding how different feedstuffs are fermented in the rumen. However, investigating the kinetics of their production is a critical next step to gaining deeper insights into the metabolic processes driving methane emissions in the rumen.

This review describes a novel, fully automatic system called Gas Endeavour (GE) (BPC Instruments, Lund, Sweden). This system not only measures total gas and methane production but also provides comprehensive data on the methane kinetics of ruminant feeds. We evaluated the system’s applicability to animal nutrition research, its operational procedures, and its performance outcomes. The results highlight the potential of this technology in advancing our understanding of feed fermentation and mitigating methane emissions.

2. In Vitro Gas Production Techniques (IVGPT)

These techniques have been widely used to understand the rumen degradability of feed and forages. Rymer has reported a detailed history and methodological considerations of IVGPT over the time [

16]. Along with the increasing interest in GHG emissions, researchers and companies are developing systems to investigate methane emissions using IVGPT , which is why some traditional systems have been modified to assess methane emissions and methane kinetics [

17,

18].

2.1. Siringe Method (Hohenheim Gas Test)

The pioneering method developed by Menke for measuring

in vitro gas production employs large calibrated syringes filled with feed and buffered rumen fluid. In each syringe, 200 mg of feed dry matter are incubated, and GP values are manually recorded after 24 hours of incubation at 39°C [

19]. Using these data, Menke formulated equations to estimate the metabolizable energy of feeds. The resulting values have proven to be highly accurate and strongly correlated with those obtained using more recent methods, which are based on dry matter degradability measured both

in vitro and

in vivo [

20]. To better capture fermentation kinetics, Blümmel and Ørskov [

21] modified Menke’s method by incubating the syringes in a thermostatically controlled water bath, ensuring more consistent temperatures throughout gas recording. Blümmel et al. [

21] and Makkar et al. [

22] further adapted the method by increasing the sample size to 500 mg and doubling the buffer amount. This adjustment minimized temperature drops during gas readings, which is crucial for accurately monitoring GP over time and capturing detailed fermentation kinetics.

2.2. In vitro Methane Measuring Techniques

Several in vitro gas measurement techniques [

23,

24,

25] have been developed over the time (

Table 1) starting from manual gas estimation methods to fully automatic systems [

26] to asses the nutrititive value of feeds and the use of nutritional strategies to mitigate methane emissions. Most of GP systems assess methane production at the end of the incubation using techniques like gas chromatography [

26]. Pellikaan et al. [

27] adopted the method described by Cone et al.[

28], modified it to measure methane kinetics by extracting gas from headspace through gas tight syringes. Similarly, Ramin and Huhtanen [

29] sucessfully measured methane kinetics from in vitro GP measurements by collecting GP at various intervals of incubation followed by gas chromatography equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD), to then apply a dynamic mechanistic rumen model to predict the methane kinetic parameters. Another fully automatic system developed by Ankom Technology® (Macedon, NY, USA) is the ANKOM

RF gas production system. This system that allows to maintain low pressure inside the bottles (6.9 kPa) [

30] as high pressure can effect the end products [

31] and the rate extent of fermentation [

20]. It has been used successfully to visualize and analyze GP kinetics, substrate utilization rates, and other critical parameters [

32,

33,

34]. However, since this system is also unable to explain the methane kinetics, again, gas chromatography has been used to assess the compositional analysis of gas produced during fermentation. Also, this methodology measures the gas pressure which needs to be converted into moles of gas produced using the ideal gas law equation and then covert it into milliliters of gas produced by using the Avogadro’s law. Furthermore, the instrument has other technical drawbacks such as leakage of gas and battery failure [

35]. Another fully automatic GP system was developed by Muetzel et al. [

36] which can measure GP and methane production kinetics in real time without any manual extraction of gas from headspace of bottles. This system collects and analyzes fermentation gases with a computer-controlled gas chromatograph, rather than allowing them to escape into the atmosphere once a certain pressure threshold is reached as in previous system [

32].

Recently, Braidot et al [

37] developed a volume

-based_system that uses an IR gas analyzer to measure methane concentration from gases produced in airtight fermentation bottles. Gas volume is tracked by a gas counter, then directed to the analyzer, which accurately detects methane levels under controlled conditions. Headspace within the bottles and tubing ensures consistent gas measurement before analysis.

2.5. Limitations of IVGPT

The availability of rumen fluid to prepare inoculum is one of the limitations of all the

in vitro approaches, since it is not always readily available due to high management expenses, ethical concerns, mixing of saliva during the oral stomach tubing technique or the need of facilities to maintain rumen fistulated animals [

38,

39,

40]. Similarly, seasonal changes, fluctuations in feed intake and diet composition among individual animals, and differences in harvesting techniques can all result in qualitative discrepancies in rumen fluid collected at different times, even from the same animal. Therefore, a potential approach is to store the rumen fluid in order to minimize the variations and standardize the rumen microbial activity or, to use it immediately after rumen extraction. Indeed, storing rumen fluid using 5% of dimethyl sulfoxide and frozen it at -20 °C has resulted in lower GP with lower variability between treatments compared to the use of fresh rumen [

33]. These challenges, which affect all aspects of evaluating ruminal fermentation processes, are particularly pronounced when the research objective is to assess methane emissions. The strictly anaerobic microflora, responsible methanogenesis, is highly sensitive to disturbances caused by the preparation of the microbial inoculum. Any stress experienced by the inoculum leads to a disproportionately greater reduction in methane emissions compared to the overall reduction in GP [

41].

Another limitation of

in vitro techniques that utilize fermentation bottles instead of syringes lies in managing the pressure buildup within the headspace. Specifically, monitoring pressure variations in the headspace is difficult to achieve using manual or semi-automatic methods. Releasing fermentation gases (venting) is crucial to maintaining low pressure inside the bottles and preventing CO₂ solubilization in the medium[

20]. However, this process must also prevent air ingress, which could disrupt anaerobic conditions, and avoid temperature fluctuations, which could compromise the accuracy of gas volume measurements.

Table 1 summarizes various IVGPT developed over time for estimating gas and methane production, most of them are based on pressure measurements from fermentation vessels through sensors. However, and specifically for methane production, these systems do not provide kinetic data that describes extent and rate of digestion from single sample incubation. They are mostly indirect methods, requiring the analysis of the gas produced at the end of the incubation to determine the proportion of methane, which is then used to calculate the total methane production.

Table 1.

In vitro fermentation parameters and experimental setup that can influence gas production measurements and the composition of fermentation gases (adapted from Yáñez-Ruiz [

42]).

Table 1.

In vitro fermentation parameters and experimental setup that can influence gas production measurements and the composition of fermentation gases (adapted from Yáñez-Ruiz [

42]).

| Reference |

Device |

Water-bath / air incubator |

Devise

volume, mL |

Inoculum / medium ratio,

mL/mL |

Buffer

reference |

Duration of incubation, h |

Dietary substrate, buffered medium ratio

mg/mL |

Gas venting, and collection |

Pressure control |

Gas measurement, and analysis |

| Menke et al. [19] |

Syringes |

Water rotor-bath |

30 |

1:2 |

[19] |

24 |

6.67 |

Manual,

Endpoint sampling |

Yes, moveable glass piston |

Manual,

no analysis |

| Theodorou et al. [24] |

Bottles |

Air

incubator |

60 |

1:9 |

[24] |

24 – 72 |

2-20 |

Manual,

Endpoint sampling |

No, pressure increase |

Manual,

no analysis |

| Mauricio et al. [38] |

Bottles |

Air

incubator |

100 |

1:9 |

[24] |

n.s. |

10.0 |

Manual,

Endpoint sampling |

No, pressure increase |

Manual,

no analysis |

| Pell and Schofield [23] |

Bottles

stirred |

Air

incubator |

10 |

1:4 |

[43] |

n.s. |

10.0 |

Manual

Endpoint sampling |

No, pressure increase |

Manual,

CH4 by GC |

| Cone et al. [28] |

Bottle

shaked |

Water

bath |

100 |

1:2 |

[44] |

48 |

6.67 |

Automated

Fixed pressure |

Yes |

Manual,

|

| Davies et al. [45] |

Bottles |

Air

incubator |

100 |

1:9 |

[24] |

n.s. |

10.0 |

Automated

Fixed pressure |

Yes |

n.s.,

n.s. |

| Cornou et al. [35] |

Bottles |

Air

incubator |

60 |

1:2 |

[44] |

72 |

8.33 |

Automated

Fixed pressure |

Yes |

Manual,

no analysis |

| Muetzel et al. [36] |

Bottles |

Air

incubator |

60 |

1:4 |

[46,47] |

48 |

10.0 |

Automated

Automated |

Yes |

Automated,

CH4 by GC |

| Pellikaan et al. [18] |

Bottles

shaked |

Water

bath |

60 |

1:2 |

[44] |

72 |

8.33 |

Automated

Vented pressure?? |

Yes |

Manual,

CH4 by GC |

| Tagliapietra et al. [20] |

Bottles |

Air

incubator |

75 |

1:2 |

[44] |

144 |

6.67 |

Automated

Automated |

Yes |

Manual,

CH4 by GC |

| Braidot et al. [37] |

Bottles stirred |

Water

bath |

500 |

1:2 |

[44] |

48 |

6.67 |

Automated

Automated |

No, Volume base |

Automated,

CH4 - infrared |

3. The Gas Endeavour System

The Gas Endeavour (GE), an automatic gas flow measurement system developed by BPC Instruments (Lund, Sweden), is a volumetric gas measurement apparatus capable to detecting low gas volumes [

48]. Initially introduced as the Automatic Methane Potential Test System (AMPTS), it functions as an anaerobic batch fermentation system. The GE operates on the principles of liquid displacement and buoyancy to measure GP. This device allows for the simultaneous analysis of multiple samples with in a thermostatically controlled water bath that contains 15-18 digestion bottles continuously shaking at a defined rpm. The water bath, which serves as an incubator, maintains a constant temperature of 39°C by an automatic heat controller. Samples are weighed directly into the bottles together with the inoculum (rumen fluid) and a buffer solution. The duration of incubation depends on the study's objectives and typically lasts up to 140 hours for feed characterization. GE estimates not only gas and methane production but also their kinetics. GE is a real-time instrument design for measuring the kinetics of both total gas and methane production in the biofuels sector.

In the field of animal nutrition, the GE is still an emerging tool and, compared to other techniques, requires further data validation and the development of standardized protocols to ensure reliability in this context.

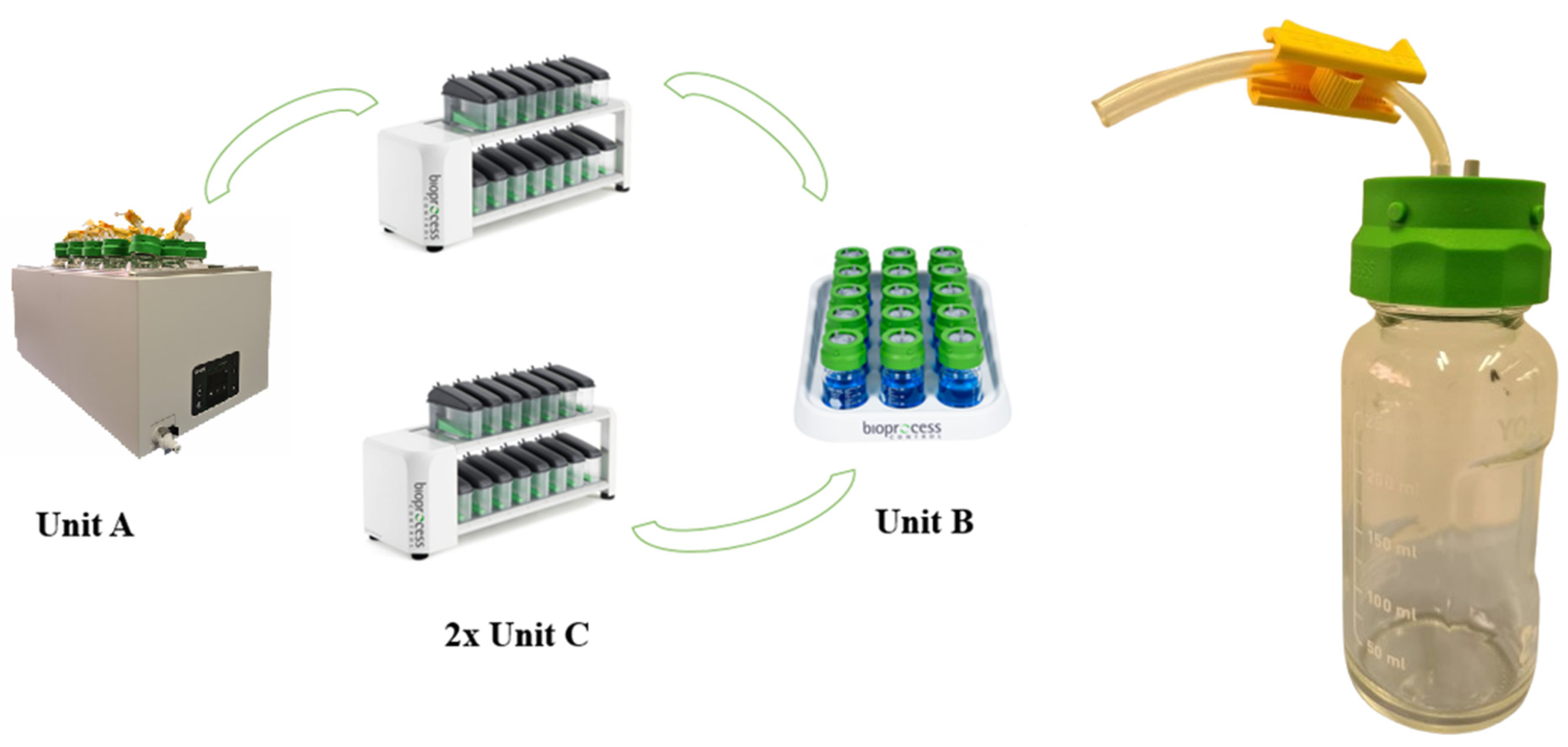

Figure 1.

Gas Endeavour system.

Figure 1.

Gas Endeavour system.

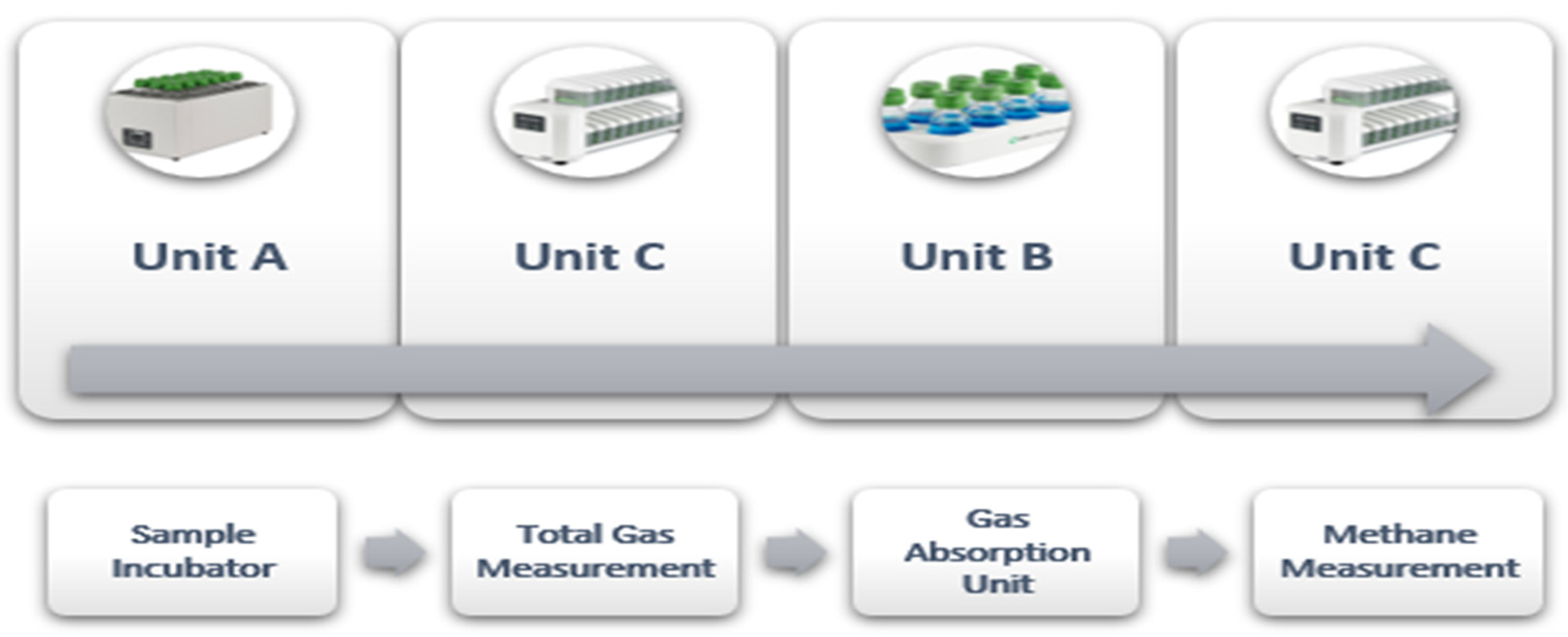

3.1. Parts and Functionality

Four essential parts (

Figure 2) make up the GE: unit A, unit B, and two units C. Then the whole system has be connected to a computer to assess to all the functionalities of the system, from settings to results. The equipment described in this review is the one used for animal feed

in vitro purposes.

Unit A consists of a thermostatic water bath that serves as incubator, here water temperature and agitation can be set manually before every incubation. Inside unit A, 15 bottles or glass reactors with a capacity of 250 ml each contain the sample and other reagents. The bottles are tightly and hermetically closed by a plastic screw cap with two holes or ports (

Figure 2). One port is independent, it has just a short Tygon tube with a yellow stopper that allows the opening or closing of the air flow. This is the via from which the liquid reagents can be easily added inside each bottle without opening them and disturbing the anaerobic system. The second whole directly connects each bottle to its own flow cell in Unit C-1 through a Tygon tube. These tubes will transport the gas produced from the bottles of Unit A to the flow cells of Unit C-1.

Unit C is responsible for gas measurement and consists of two units used to measure both total gas (C-1) and methane (C-2). Unit C-1 includes 15-18 flow cell units, each with a measurement resolution of 2 ml, corresponding to individual bottle reactors. Each cell is equipped with two ports: a gas inlet port that receives gas from the reactor, where every 2 ml of gas displaces liquid, causing a plastic valve to move up and down, which signals a reading. The more frequently this valve moves, the greater the amount of gas being produced. The gas outlet port is connected to Unit B via Tygon tubes, transferring gas that has already been measured by the flow cell. Unit C-2 mirrors the structure of Unit C-1 but connected to Unit C-1 via Unit B to measure methane production.

Unit B serves as the gas absorption unit. It consists of 15 glass bottles, each with a capacity of 100 mL, containing 80 mL of a 3M NaOH alkaline solution. Each bottle is equipped with a plastic screw cap featuring two ports. One port receives the gas produced by the reactors, which has already passed through the flow cells of Unit C-1. Inside the bottles, carbon dioxide is absorbed by the alkaline solution. The second port of each cap is connected to another flow cell in Unit C-2 via a Tygon tube.

Figure 3 explains the workflow of the GE system. This scientific arrangement enables the effective investigation and monitoring of the system's gas dynamics [

48]. During and at the end of the incubation, the system provides these parameters: total gas and methane production (both cumulative and at specific intervals, e.g., every 1 min, 5 min, 15 min, 1 hour, etc.), and the gas flow rate. Additionally, the system displays graphical representation of each parameter throughout the whole incubation. All recorded data can be downloaded on-line as an excel file through a computer connected to the measuring units [

49].

3.2. Area of Application of the Gas Endeavour System

The GE system has been employed across multiple fields to measure gas production (GP), including the assessment of biomethane potential , [

50,

51], biohydrogen potential [

52,

53], and biomass degradability [

54,

55] of substrates intended for anaerobic digestion, such as agricultural residues and organic waste. Additionally, the GE system is widely used to evaluate the fermentation characteristics of various feedstuffs, including gas production kinetics and methane emissions. Although relatively few studies have explored its application in assessing the quality of feeds and diets for animal feeding and nutrition, promising results have been reported [

56,

57].

3.2.1. Biomethane Potential

GE has been successfully used as a regulated laboratory method for determining the biochemical methane potential (BMP) of biodegradable materials automatically, predominantly for measuring methane coming from anaerobic fermentation from various organic substances. The technique has been commonly used to measure the methane potential along with the biodegradability status of wastewater and waste biomass from different sources [

58,

59,

60]. Several studies have leveraged Gas Endeavour’s automated data logging and controlled environment capabilities to improve the reliability and reproducibility of BMP assessments. For example, research by Zsuzsanna [

50] compared the BMP measured with GE and theoretical methane production from using different biodegradable plastics. A non-significant difference was observed between the theoretical and measured biomethane values for one of the products, demonstrating the accuracy of biomethane measurement using the GE system. Moreover, the

Gas Endeavour has been applied across a range of substrates [

61], from agricultural residues to food waste, proving versatile in handling the variability in methane production rates typical in BMP tests. Studies, including [

59,

61,

62,

63], found that the system’s precision allowed for detailed kinetic analysis, revealing insights into degradation rates and methane production potential across diverse substrates. This adaptability makes it a preferred choice for researchers aiming to compare substrates under identical conditions.

A comparative analysis between the predecessor of GE, the Automatic Methane Potential Test System (AMPTS II), and the Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN) method for evaluating total biogas production was done [

64]. Both the AMPTS II and DIN standard method are batch systems measuring biomethane via gas volume. AMPTS II uses the same principal as GE while DIN method uses manual eudiometers (graduated glass tubes) filled with a low-pH buffer to prevent CO₂ absorption, measuring total biogas volume by liquid displacement. Methane content is determined periodically via external gas sampling. While both are volume-based batch systems, the key distinction lies in CO₂ handling—AMPTS II chemically removes CO₂ for direct methane measurement same as GE, whereas the DIN method retains CO₂ in biogas and measures methane indirectly through manual analysis. Comparative analysis recognizes the GE (AMPTS II) as a new device to analyze biomethane that is more automated and rapid method than the DIN. For this test, the GE used 14 bioreactors or bottles with a stirrer incorporated in each cap. The stirring was done every 30 minutes, the temperature of the water bath was set at 38 °C and nitrogen was used to flush and purge the Tygon tubes of the instrument. Ten feedstocks were tested: paper sludge, waste jelly, lactose pellets, used cattle bedding, manure scrap, potato sludge, parlor water, fresh straw, cyanobacterial biomass and hot dog casings. Results showed that eight out of these ten feedstocks were significantly different but the AMPTS results at 21 days aligned with the DIN results at 28 days. This suggests AMPTS achieves stable measurements faster, potentially reflecting higher consistency in biogas production. While fresh straw and hot dog casings were not significantly different for total biogas and methane production. The findings revealed notable differences between the systems, warranting further investigation to understand the underlying reasons [

64].

Similarly, when GE was compared with the manual biomethane test. Significantly higher methane production was measured using the GE system compared to the BMP. The differences were attributed to the type of method used to measure methane production, manometric (BMP) against volumetric (GE) [

65].

3.2.2. Animal Nutrition

After successful usage of GE in the biogas sector, researchers are using GE to measure methane and total gas in animal nutrition to assess the effect of feed additives and forages on methane emissions. Researchers are taking more interest in using this system in animal nutrition as the system is fully automated and can provide methane production and kinetics in real time [

49]. While other batch systems, like AnkomRF, required gas chromatograph to measure methane. In ruminant nutrition research, where understanding the digestibility and methane emissions of feeds is crucial, this instrument plays a key role in evaluating how different feed formulations influence fermentation processes and gas output in vitro. For instance, the effect of chopped grass has been investigated on silage and results showed that chopping of silage increased the rumen fermentability, resulting in 9 percent increase in methane production [

66]. Researchers from University of Parma, Italy used this system first time for the purpose of improving ruminant nutrition. They tested multiple feedstuffs to analyze the results of GP from GE [

67] . Similarly, to understand the effect of feed additives on GP kinetics of Bioflavex (Exquim S.A., Barcelona, Spain), a commercial additive made by a mixture of natural flavonoids from which naringina was the main component taken from

Citrus aurantium and

Citrus paradise was used as feed additive. The in vitro incubation was done using a TMR ration for dairy cows producing milk for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese and adding increasing dosages of additives (50, 100, 200 and 400 g/cow/day). Results of total GP at 24 hours of in vitro incubation using the GE showed that the use of Bioflavex did not affect the total GP in any of the dosages applied. However, the GP between the 1st and 8th hour of incubation was lower with the use of the additive at the 4 dosages in comparison to the control diet [

68].

The GE has also been utilized to detect and evaluate the ruminal bioavailability and solubility of trace minerals, as they can influence rumen microbial activity, diet fermentation, and the fulfilment of animals' nutritional requirements. For instance, a study revealed that MnSO

4, ZnSO

4, and CuSO

4 are highly soluble in the rumen, MnO is moderately soluble, and ZnO has low solubility. To enhance the number of replicates, the study employed two GE devices. This bioavailability assessment, based on the trace mineral content, indicated high bioavailability for MnO, MnSO

4, and CuSO

4, while ZnO showed poor assimilation by rumen bacteria [

69].

Similarly, GE was used also to simulate the large intestine fermentations of different types of dietary fibres and the production of butyrate incubating the substrates in faeces of pigs [

70]. Researcher used GE to determine the total GP and took advantage of the kinetics given by the instrument by showing its graphics of cumulative GP profiles. The results showed that the replicates were similar between each other for GP, with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 3.37% at 24h and 2.65% at 48h, which may reflect the repeatability of the GE [

70].

3.3. Challenges and Considerations in Practical Use of GE

Using the GE system in animal nutrition and fermentation studies requires careful attention to experimental details. Given the small volume of gas produced after 24 hours of incubation, accurate measurement is essential. While the system’s high sensitivity and automated features provide significant advantages, they also require precise setup and calibration. Below are key challenges and practical considerations to address:

3.3.1. Buffer, Rumen Inoculum and Feed Substrate Ratio

The volumes of buffered rumen fluid and substrate incubated are directly correlated with GP and methane production kinetics, serving as critical parameters in GE systems. The ratios of buffer volume, rumen fluid volume, and substrate amount have been extensively studied and reported in the literature. Menke suggests a rumen-to-buffer ratio of 1:2; for preparing 30 mL of the inoculum, Menke used 0.22 g of diet with 10 mL of rumen liquid and 20 mL of buffer [

19] Van Soest proposes a ratio of 1:4, for preparing 50 mL of inoculum 0.5 g diet with 10 mL rumen fluid and 40 mL buffer [

43]; and Cone adopts Menke's 1:2 ratio [

28]. These ratios substantially influence key factors such as: a) Microbial fermentative activity, which determines the efficiency of substrate breakdown; b) Buffering capacity of the medium, which regulates pH stability and modulates CO₂ release; and c) Total gas volume (CO₂ and CH₄) produced during fermentation, reflecting the metabolic pathways of the microbial consortia. Despite the broad range of working volumes (medium + inoculum) utilized in biomethane potential studies (ranging from 150 mL to 400 mL, with 200 mL being the most commonly adopted [

58,

59,

61]) the impact of these variations on methane production kinetics in GE systems remains insufficiently explored. A systematic investigation into how medium and inoculum volumes influence fermentation dynamics could provide valuable insights.

Recommendation: Standardize the ratio between buffer, rumen inoculum and substrate of fermentation in the GE system to ensure consistent and reliable results.

3.3.2. Bubbling of CO₂

The preparation of buffer solutions requires the bubbling of CO₂, and the duration of this process is a critical factor [

19], as it can affect total GP and kinetics. This effect is due to the absorption of CO

2 into the buffer solution as carbonic acid and its subsequent release during incubation. While the solubility of CO₂ in water has been extensively studied [

71,

72], limited research has been conducted to determine the optimal bubbling duration for CO₂ in the buffer. Most protocols follow the Menke and Steingass’ recommendation [

19] which suggest the use of resazurin and bubbling of CO

2 until colour change following continuous flushing of bottle headspace with CO

2 during medium preparation to maintain an anaerobic environment. However, significant variability exists among researchers, with some studies reporting CO₂ bubbling durations of up to 2 hours [

26,

73]. This highlights the lack of standardization in protocols regarding the optimal bubbling time, which could impact the reproducibility and accuracy of experimental results.

In laboratory routines, the pressure to reduce analysis time can often lead to an underestimation of the critical role of this procedure. It is essential for establishing a strictly anaerobic environment, which is vital for the growth and activity of methanogenic populations. Additionally, this procedure ensures a consistent release of CO₂ from the buffer, which directly impacts the CO₂ to CH₄ ratio in fermentation gases, ultimately influencing the accuracy and reliability of the experimental results.

Recommendation: Standardize the CO₂ bubbling time during medium preparation to ensure the medium achieves a complete color change. This will minimize the risk of underestimating GP and CH₄ production, particularly during the critical initial hours of incubation.

3.3.3. Effect of Shaking on Gas Production

The agitation or shaking of reactors is an aspect of major concern, as it represents a wide variation across IVGPT methodologies [

16]. Mixing play a crucial role in ensuring the even distribution of microorganisms within the medium, preventing the sedimentation of particulate material, equalizing the temperature distribution inside each bottle and aiding in the release of trapped gas bottles. Agitation method include stirring, shaking or vigorously agitating. Some Authors perform agitation manually or with devices like magnetic stir bars. Practices vary widely: some protocols call for agitation only once, typically at the start of incubation; others do so at fixed intervals, often when measurements are taken; while some procedures omit agitation altogether or fail to report it. In the literature, there is a lack of experimental evidence on the effects of agitation on fermentation processes and the release of fermentation gas. The

GE instrument, with its ability to customize times, speed, and rhythm of agitation, provides a valuable tool for investigating optimal operating conditions and developing guidelines for standardizing

in vitro methods.

Recommendation: The shaking or stirring speed should be controlled to prevent the deposition of dissolved substances or particulates (diet) onto the headspace area or bottle cap. Such deposition may obstruct the gas outlet and leave residues of unfermented diet, potentially leading to inaccurate gas and digestibility measurements.

3.3.4. Effect of Headspace Pressure on Gas Production

In pressure-based GP systems [

25,

74] there is a potential for underestimating GP as incubation progresses. The increasing pressure from the gas produced within the bottles promotes the solubilization of CO₂ into the fermentation liquid as carbonic acid, potentially leading to buffer CO₂ oversaturation [

75]. This acidification of the medium selectively inhibits microbial activity and can alter the accuracy of gas volume measurements and impact the interpretation of fermentation kinetics. However, the introduction of gas venting in automatic pressure-based GP systems has addressed this issue [

32,

76]. Venting the gas accumulated in the bottle headspace is a critical step for ensuring accurate measurement of GP, as each release carries the risk of introducing measurement errors. In contrast, the GE system, a volume-based approach, avoids venting gas into the atmosphere. Instead, it transfers the gas to a measurement unit, maintaining constant pressure in the reactor bottles. Despite these advantages, a detailed study is necessary to evaluate the potential for CO₂ solubility in both the inoculum and the water present in the GE measurement cells. This is particularly relevant given the solubility of CO₂ in water, which is 0.231 mmol L⁻¹ kPa⁻¹ at 37°C, as dictated by Henry's Law [

77]. Nevertheless, preliminary findings from our lab (unpublished data) indicate that the reduction of bottle headspace provides more repeatable GP and CH₄ kinetics in GE system.

Recommendation: Use the smallest possible bottle headspace volume to optimize conditions for accurate GP, specifically for methane measurements with GE system.

3.3.5. Effect of Headspace Pressure on Methane Production

Methane production kinetics can be measured using various procedures, with the most common being: a) Batch systems without gas release: Analysis of the composition of gases accumulated in the headspace of the fermentation bottle. b) Batch systems with gas release: Analysis of both gases accumulated in the headspace and those collected in a dedicated gas bag for released gases. c) Batch systems with an alkaline trap: The trap removes CO₂ from the fermentation gas, enabling the measurement of gas volume, which is assumed to consist exclusively of CH₄ [

78,

79]. The main limitations of these procedures are: "a": the increase in headspace pressure enhances CO₂ solubilization into the medium (see section 3.4.1.4). This process can lead to underestimation of GP measurements and overestimation of CH₄ proportions (%);"b": This method involves dual analysis, which increases the variability of experimental results due to potential air contamination and errors during gas sampling; "c": this procedure is utilized in the GE system and presents the following challenges: i) Potential air contamination (mainly N₂ and O₂) in the headspace and tubing cannot be recognized leading to overestimation of CH₄ measurements; ii) Delayed of CH₄ production measurement compared to GP measurements with both distortion of their kinetics and underestimation of CH₄ proportion (%).

The last issue has been addressed in Gas Endeavor (GE) through the Over- and Under-Estimation function, which allows users to input “headspace gas concentration”, “initial flushing headspace concentration”, and “final headspace concentration” [

80]. However, the impact of this function on methane kinetics calculations requires further analysis. On the other hand, pressure-based systems like AnkomRF avoid issues of methane over- or underestimation entirely, as these systems do not measure methane kinetics directly.

Recommendation:

Remove air from bottle headspace and tubes of connection flushing the system with CO₂. Minimize the bottle headspace volume to reduce the risk of interference from potential air contamination. Incubate at least 1 gram of substrate to minimize the impact of potential air contamination on GP, CH₄ production, and proportion.

3.3.6. Normalization of Gas and Methane Measurement for Temperature, Pressure and Vapor Interference

According to universal gas law, the volume of gas is directly proportional to temperature atmospheric pressure and small changes of these operative conditions can lead to variation in gas measurement resulting in different GP and methane kinetics. Moreover, temperature influence the production of water vapors, i.e. at the temperature of 39°C, around 7% of gas volume is occupied by water vapours [

81].

Historical work conducted by Menke to estimate the energy value of feeds using GP measurements was based on data collected at a standardized temperature of 39 °C but without any control on atmospheric pressure. Manual gas measurement systems using bottles cannot standardize the temperature and pressure during gas collection and measurement, as the gas is typically measured at room temperature. In contrast, automated gas measurement systems enable temperature standardization, allowing gases to be measured either at 39 °C or at room temperature and allow the normalization of atmospheric pressure. In particular, the GE system measures gases at room temperature.

In general, according to ISO 10780, gas volumes must always be expressed in “normal conditions”, i.e. at 273.16 K (0 °C) and 101.3 kPa, however, most scientific publications in animal nutrition use data standardized to 39 °C and do not report any information on atmospheric pressure conditions. To solve this problem, gas measurement should be corrected at “normal conditions” for temperature and pressure, avoiding also the effect of vapor production. In GE system, users can measure the gas volume in both conditions, normalized and non-normalized [

80] resulting in more accurate gas measurement.

Recommendation: Standardize the laboratory temperature and adjust GP and CH₄ data to 39°C to ensure consistency with the majority of available scientific literature. However, the data provided by the GE at 273.16 K (0 °C) and 101.3 kPa is more accurate measurement of gas measurements.

3.4. Gas Endevour Properties and Characteristics: Strengths and Weaknesses

3.4.1. Gas and Methane Measurement

The primary purpose of GE system in animal nutrition is to measure GP, CH₄ production and their kinetics during

in vitro fermentation. This is achieved using sensors and software that continuously monitors and log data into a computer. Once the experiment begins, no further human intervention is required until the incubation is completed. The equipment offers a sensibility of 2 ml and a measurement uncertainty declared by the producer of 1% [

80] ensuring high accuracy. This accuracy is supported by the already described key design elements, including gas venting mechanism, controlled bottle environment and continuous shaking in Unit A.

Unlike other in vitro techniques, which require additional analyses such as gas chromatography to determine the methane content at the end of incubation, the GE system provides continuous methane production measurements throughout the process. Integration of the system with Unit C allows direct methane quantification, reducing time-consuming and resource-intensive post-incubation analyses.

Another opportunity offered by GE system is the format of its results. While other IVGPT often report gas production in terms of pressure (psi or kPa), requiring conversion to volume using specific equations, the GE system directly provides results in volume (mL) of gas and methane produced. This eliminates conversion steps, streamlining data interpretation and reducing errors.

3.4.2. Gas and CH₄ Flow Rate and Kinetics

The rate at which a feed or its chemical components ferment in the rumen is as crucial as the extent of digestion. Feeds with similar overall degradability can ferment at different rates, leading to variations in ruminal dynamics such as rumen bulking capacity, passage rate, and nutrient availability for microbial growth. It has been demonstrated [

82] that cumulative gas production after 24 hours of incubation does not necessarily correlate with fermentation rates. Therefore, the GP rate is significantly affected by feed intake, and consequently, dairy performances in terms of milk production and quality, as well as methane emissions expressed as daily production (mL/d) or related to milk yield (mL/kg milk) [

83].

While many in vitro techniques require sophisticated equipment to record GP at different incubation times, the GE System measure the GP flow inside each fermentation reactor, monitoring the rate of gas production at any time of the incubation.

Similarly, the i

n vitro CH₄ production is often evaluated at a single time point, typically at the end of the incubation, leaving limited scientific data on the kinetics of methane formation during fermentation [

84]. An advantage of GE system is that kinetics of fermentation, of gas and methane, can be studied on the same sample, enabling the computation of changes in methane production rates over time. For instance, GE system was used to study the rumen fiber fermentation of soybean and maize silages, evaluating GP kinetics [

85]. Similarly, the potential and rate of methane production have been investigated for components of corn stover, including stem bark (SB), stem pith (SP), and leaves (LV) over time[

86].

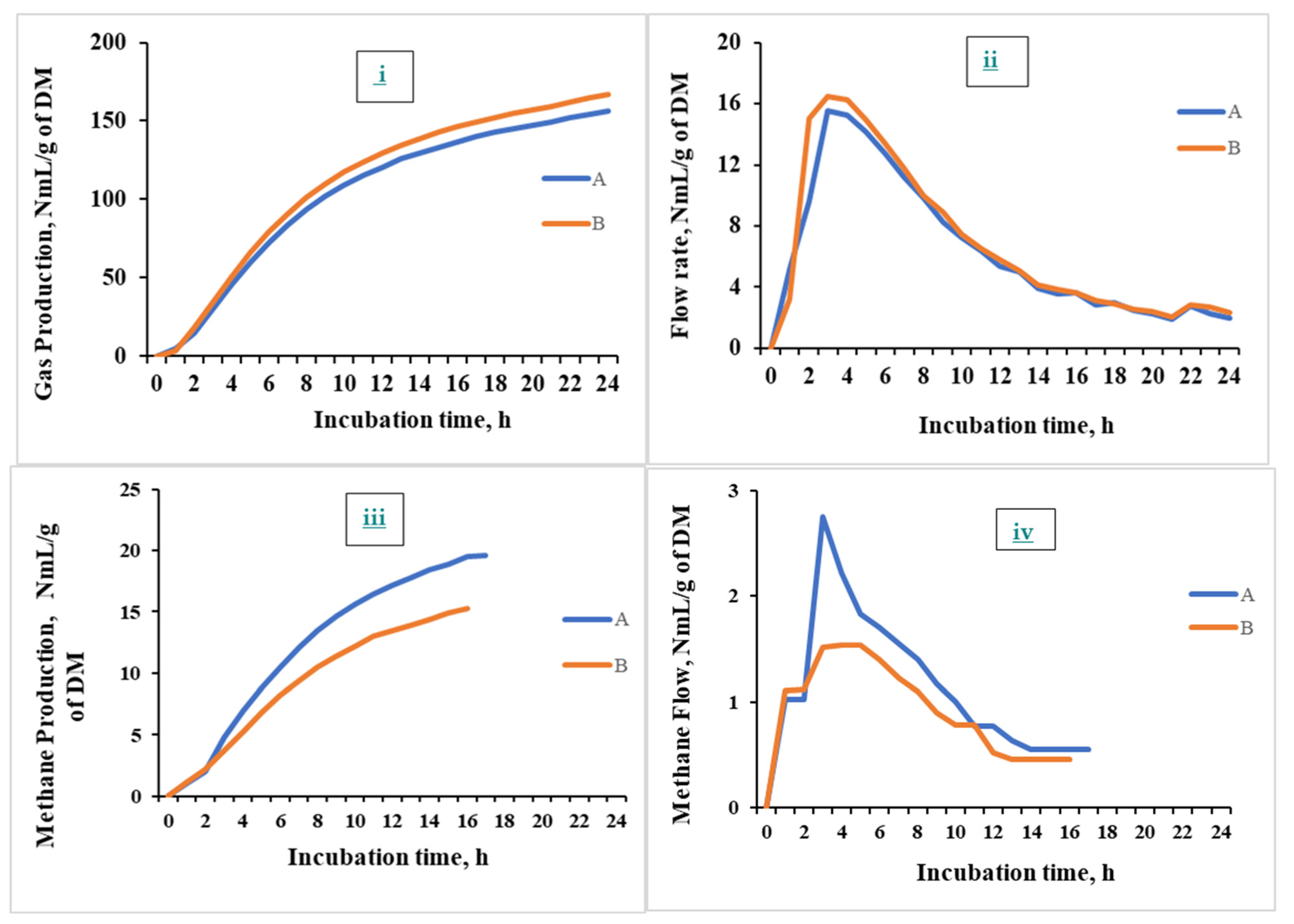

3.4.3. Real-Time Monitoring

The GE provides, in real time, the total gas and methane production kinetics that can be monitored at every moment. This information can be expressed across various time intervals, such as 1 minute, 15 minutes, and 1 hour. The real time monitoring allows the incubation time to be easily adjusted. The incubation can be stopped or extended depending on the GP curve showed on the screen, so it guarantees a sufficient time of fermentation of the testing material. In fact, some studies recommends to stop the incubation at the pick of GP at which the efficiency of microbial production is maximum[

87] to study the microbial profile and activity, and the product of fermentation. The GE system has not yet been used for this purpose; however, theoretically, it could be applied, offering significant time and cost savings in analysis compared to other in vitro systems that lack continuous gas production monitoring. In

Figure 4 is reported an example of cumulated gas and methane production throughout a 24 h incubation period. The demonstrative trial was conducted using a standard total mixed ratio (TMR) of lactating dairy cows following the procedure outlined in this review. Rumen fluid was collected from two Italian Simental lactating cows at the Experimental Farm “Lucio Toniolo” of the University of Padova, Italy. The TMR was formulated to meet nutrient recommendations [

88] and included corn silage, mixed meadow hay, alfalfa hay, wheat straw, energy mix (corn and wheat), protein mix (soybean and sunflower), wheat germ, and molasses. Two experimental bottles were prepared, each containing 1±0.0010 g of TMR, 50 mL of rumen fluid, and 100 mL of buffer with a bottle headspace of 160 mL. Gas and methane production were recorded hourly.

3.4.5. Limitations

While

in vitro methodologies are generally less expensive than

in vivo experiments, the GE system has higher initial installation costs compared to other

in vitro methods [

89]. However, these costs can be offset with consistent use across multiple trials, making it cost-effective over time.

The system’s throughput is limited, as it cannot handle as many simultaneous samples as gravimetric or manual systems. With limited bottle capacity, a maximum of four treatments per run is possible, including blanks, controls, and triplicates for statistical validation.

The Tygon tubes that connect the bottles (Unit A) with the flow cells (Unit C-1) often get blocked with water droplets. Water condensation occurs at the very end of the procedure, after the rumen fluid is injected into the bottles. This may be a major concern because these tubes transport the gas produced in the reactors. If they get blocked with water, the gas accumulating in the headspace of the bottles might not be able to pass through and will not arrive to the measure cell flow. Also, this might alter the pressure inside the bottles leading to a possible underestimation of the total GP and an overestimation of CH₄.

Any standardization of the procedure on how to use the GE for feedstuff in vitro GP has been established until now. As with any new equipment, its implementation requires further examination for adapting the technique to the system and also some repetition to refine the method. Even though a full standardization of the technique is not feasible because of issues mostly related to the animal and the rumen fluid, a basic protocol that covers the procedure of incubation is needed. Harmonization of the whole procedure and detailed information regarding analytical procedures will guarantee repeatability and then facilitate the validation of GE results and the comparison between results from different in vitro experiments. Chemical methodologies should not have a problem regarding repeatability, but again, as we are dealing with biological agents such as rumen fluid, results may differ among authors. This is also why a comparison of GP measurement between different laboratories needs to be done to achieve reproducible results and then validation.

A comparison with some other techniques that have been extensively studied could be conducted in order to validate the GP results from the GE. As has been discussed before, the results coming from volumetric-based methods tend to be higher than the ones coming from pressure-based methods. If this is the case, the GE may be overestimating the GP.

Therefore, further studies are required on the development of a standardized procedure for feedstuff in vitro fermentation, and the in vivo significance of the results obtained.

4. Potential Future Applications

GE system initially developed to measure biomethane potential has since found applications in various fields such as wastewater treatment, biodegradability testing, and notably, animal nutrition. A quick Google Scholar search shows that there are over 150 publications referencing the GE system overall, while animal nutrition–specific studies—including conference proceedings, theses, and journal articles—number around 30. These figures are approximate and depend on the search terms used (e.g., “Gas Endeavour animal nutrition” versus “Gas Endeavour biogas”).

With further development and research, GE can be used for a variety of objectives across numerous sectors, especially in the ruminant nutrition field. GE applications go beyond measuring ruminant methane generation [

49]. Even though it is clear that GE could play an important role in the study of rumen modulators for increasing efficiency of microbial protein synthesis and decreasing methane emissions by ruminants, GE can be useful to provide better insights in other nutritional parameters. Like any other

in vitro technique, GE may be used to predict voluntary intake because studies have reported that there is a significant correlation between

in vitro GP and dry matter intake [

90]. Also, it could be a useful tool to assess the action of anti-nutritional factors such as alkaloids, tannins, saponins, phenolics, etc. on rumen fermentation. Some ingredients often contain secondary compounds that affect rumen microbes. They are able to dilute and solubilize inside the rumen, so their effect is somehow difficult to assess. GE could provide a better insight into nutrient-antinutrient and antinutrient-antinutrient interactions by measuring the effects of additives that can neutralize the influence of antinutrients on microbial efficiency. It could be able to predict digestibility of feeds because

in vitro rumen GP can accurately predict the metabolizable energy content of a wide variety of feeds (Getachew et al., 2005). Moreover, the use of GE could study the associative effects when mixing different types of feeds in ruminants’ diet because the use of some feed ingredients may alter the digestibility of the others by stimulating rumen fermentation. A further application could involve evaluating the effect of feed processing such as dry rolling, steaming, flaking, milling and others that may alter starch digestion by microbial enzymes. GE can assess the kinetics of different grain varieties as a way to select the ones with a greater enzymatic degradation inside the rumen. In this way, GE could become a potential and valuable tool that links plant breeding programs with ruminant performance. In general, GE could contribute to the development of nutritional supplementation strategies using locally available conventional and unconventional feedstuffs in order to achieve maximum microbial efficiency in the rumen.

5. Conclusions

Ruminant livestock production significantly contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions, primarily through enteric methane (CH₄) release. Addressing this issue requires precise, cost-effective, and ethically viable methods to quantify and mitigate methane emissions. While in vivo techniques remain the benchmark, their limitations have led to the advancement of in vitro systems like the Gas Endeavour (GE) system, which provides real-time insights into methane kinetics and fermentation dynamics.

The GE system offers significant advantages over other in vitro methods, particularly its fully automated operation, continuous monitoring, and elimination of post-incubation gas chromatography. Unlike both traditional and fully automated pressure-based methods, which only provide gas production kinetics, the GE system delivers direct methane production kinetics, enhancing its applicability across bioenergy and animal nutrition research. Despite challenges such as initial costs and protocol standardization, its efficiency and precision make it a promising tool for improving methane mitigation strategies.

In conclusion, the Gas Endeavour system represents a pivotal advancement on in vitro rumen fermentation research. By combining automation, precision, and real-time analytics, it holds potential to advance sustainable livestock practices, refine dietary strategies, and contribute meaningfully to global climate change mitigation efforts. As standardization and validation efforts progress, the GE system is poised to become a useful tool in both academic and industrial settings, bridging the gap between laboratory insights and practical agricultural solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.I.; writing—review and editing, S.A, L.B. and F.T.; funding acquisition, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out within the Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR) – MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.4 – D.D. 1032 17/06/2022, CN00000022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Food; Agriculture Organization of the United, N. FAOSTAT statistical database, FAO, 2024: 2024.

- Tubiello, F.N.; Salvatore, M.; Rossi, S.; Ferrara, A.; Fitton, N.; Smith, P. The FAOSTAT database of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. Environmental Research Letters 2013, 8, 015009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnsworthy, P.C.; Craigon, J.; Hernandez-Medrano, J.H.; Saunders, N. On-farm methane measurements during milking correlate with total methane production by individual dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2012, 95, 3166–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnsworthy, P.C.; Craigon, J.; Hernandez-Medrano, J.H.; Saunders, N. Variation among individual dairy cows in methane measurements made on farm during milking. Journal of Dairy Science 2012, 95, 3181–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghorn, G. Technical Manual on Respiration Chamber Designs. 2014.

- Storm, I.M.; Hellwing, A.L.F.; Nielsen, N.I.; Madsen, J. Methods for measuring and estimating methane emission from ruminants. Animals 2012, 2, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejian, V.; Lal, R.; Lakritz, J.; Ezeji, T. Measurement and prediction of enteric methane emission. International journal of biometeorology 2011, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.; Huyler, M.; Westberg, H.; Lamb, B.; Zimmerman, P. Measurement of methane emissions from ruminant livestock using a sulfur hexafluoride tracer technique. Environmental science & technology 1994, 28, 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lassey, K.R. On the importance of background sampling in applications of the SF6 tracer technique to determine ruminant methane emissions. Animal feed science and technology 2013, 180, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Nan, X.; Yang, L.; Zheng, S.; Jiang, L.; Xiong, B. A review of enteric methane emission measurement techniques in ruminants. Animals 2020, 10, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, P.R.Z.S. Method and system for monitoring and reducing ruminant methane production. US830 7785B2, 2012.

- Place, S.E.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Mitloehner, F.M. Construction and Operation of a Ventilated Hood System for Measuring Greenhouse Gas and Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Cattle. Animals 2011, 1, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.R.; Terry, S.A.; Biffin, T.E.; Maurício, R.M.; Pereira, L.G.R.; Ferreira, A.L.; Ribeiro, R.S.; Sacramento, J.P.; Tomich, T.R.; Machado, F.S. Replacement of soybean meal with soybean cake reduces methane emissions in dairy cows and an assessment of a face-mask technique for methane measurement. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2019, 6, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, A.K.; Hegarty, R.S.; Cowie, A. Meta-analysis quantifying the potential of dietary additives and rumen modifiers for methane mitigation in ruminant production systems. Animal Nutrition 2021, 7, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, J.; Terry, D.R. A two-stage technique for the in vitro digestion of forage crops. Grass and forage science 1963, 18, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymer, C.; Huntington, J.; Williams, B.; Givens, D. In vitro cumulative gas production techniques: History, methodological considerations and challenges. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2005, 123, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Villa, A.; O’brien, M.; López, S.; Boland, T.; O’kiely, P. Modifications of a gas production technique for assessing in vitro rumen methane production from feedstuffs. Animal feed science and technology 2011, 166, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellikaan, W.; Hendriks, W.; Uwimana, G.; Bongers, L.; Becker, P.; Cone, J. A novel method to determine simultaneously methane production during in vitro gas production using fully automated equipment. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2011, 168, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, K.; Raab, L.; Salewski, A.; Steingass, H.; Fritz, D.; Schneider, W. The estimation of the digestibility and metabolizable energy content of ruminant feedingstuffs from the gas production when they are incubated with rumen liquor in vitro. The Journal of Agricultural Science 1979, 93, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliapietra, F.; Cattani, M.; Bailoni, L.; Schiavon, S. In vitro rumen fermentation: effect of headspace pressure on the gas production kinetics of corn meal and meadow hay. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2010, 158, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümmel, M.; Orskov, E. Comparison of in vitro gas production and nylon bag degradability of roughages in predicting of food intake in cattle. Animal Feed Science and Technology 1993, 40, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar, H.; Blümmel, M.; Becker, K. Formation of complexes between polyvinyl pyrrolidones or polyethylene glycols and tannins, and their implication in gas production and true digestibility in in vitro techniques. British Journal of Nutrition 1995, 73, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pell, A.; Schofield, P. Computerized monitoring of gas production to measure forage digestion in vitro. Journal of dairy science 1993, 76, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, M.K.; Williams, B.A.; Dhanoa, M.S.; McAllan, A.B.; France, J. A simple gas production method using a pressure transducer to determine the fermentation kinetics of ruminant feeds. Animal feed science and technology 1994, 48, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, R.M.; Mould, F.L.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Owen, E.; Channa, K.S.; Theodorou, M.K. A semi-automated in vitro gas production technique for ruminant feedstuff evaluation. Animal Feed Science and Technology 1999, 79, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, S.; Jantzen, B.; Axel, A.M.D.; Tagliapietra, F.; Hansen, H.H. Effect of Iodoform in Maize and Clover Grass Silages: An In Vitro Study. Ruminants 2024, 4, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellikaan, W.F.; Hendriks, W.H.; Uwimana, G.; Bongers, L.J.G.M.; Becker, P.M.; Cone, J.W. A novel method to determine simultaneously methane production during in vitro gas production using fully automated equipment. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2011, 168, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, J.W.; van Gelder, A.H.; Visscher, G.J.; Oudshoorn, L. Influence of rumen fluid and substrate concentration on fermentation kinetics measured with a fully automated time related gas production apparatus. Animal Feed Science and Technology 1996, 61, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ramin, M.; Huhtanen, P. Development of an in vitro method for determination of methane production kinetics using a fully automated in vitro gas system—A modelling approach. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2012, 174, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankom. ANKOM RF Gas Production System. Available online: https://www.ankom.com/product-catalog/ankom-rf-gas-production-system (accessed on March 18).

- Jouany, J.; Lassalas, B. Gas pressure inside a rumen in vitro system stimulates the use of hydrogen. 2002.

- Hess, P.A.; Giraldo, P.; Williams, R.; Moate, P.; Beauchemin, K.; Eckard, R. A novel method for collecting gas produced from the in vitro ankom gas production system. Journal of Animal Science 2016, 94, 570–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkala, B.Z.; DiGiacomo, K.; Hess, P.S.A.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J. Rumen fluid preservation for in vitro gas production systems. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2022, 292, 115405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regadas Filho, J.; Tedeschi, L.; Fonseca, M.; Cavalcanti, L. 1629 (M343) Comparison of fermentation kinetics of four feedstuffs using an in vitro gas production system and the ANKOM gas production system.

- Cornou, C.; Storm, I.M.D.; Hindrichsen, I.K.; Worgan, H.; Bakewell, E.; Ruiz, D.R.Y.; Abecia, L.; Tagliapietra, F.; Cattani, M.; Ritz, C. A ring test of a wireless in vitro gas production system. Animal Production Science 2013, 53, 585–592. [Google Scholar]

- Muetzel, S.; Hunt, C.; Tavendale, M.H. A fully automated incubation system for the measurement of gas production and gas composition. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2014, 196, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidot, M.; Sarnataro, C.; Romanzin, A.; Spanghero, M. A new equipment for continuous measurement of methane production in a batch in vitro rumen system. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 2023, 107, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mauricio, R.M.; Owen, E.; Mould, F.L.; Givens, I.; Theodorou, M.K.; France, J.; Davies, D.R.; Dhanoa, M.S. Comparison of bovine rumen liquor and bovine faeces as inoculum for an in vitro gas production technique for evaluating forages. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2001, 89, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutimura, M.; Myambi, C.; Gahunga, P.; Mgheni, D.; Laswai, G.; Mtenga, L.; Gahakwa, D.; Kimambo, A.; Ebong, C. Rumen liquor from slaughtered cattle as a source of inoculum for in vitro gas production technique in forage evaluation. Agricultural Journal 2013, 8, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, T. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis: Working Group I contribution to the Fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge university press: 2014.

- Spanghero, M.; Chiaravalli, M.; Colombini, S.; Fabro, C.; Froldi, F.; Mason, F.; Moschini, M.; Sarnataro, C.; Schiavon, S.; Tagliapietra, F. Rumen Inoculum Collected from Cows at Slaughter or from a Continuous Fermenter and Preserved in Warm, Refrigerated, Chilled or Freeze-Dried Environments for In Vitro Tests. Animals 2019, 9, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Kebreab, E.; Morgavi, D.P.; O’Kiely, P.; Reynolds, C.K.; Schwarm, A.; Shingfield, K.J.; Yu, Z.; et al. Design, implementation and interpretation of in vitro batch culture experiments to assess enteric methane mitigation in ruminants—a review. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2016, 216, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, H.K.; Van Soest, P.J. Forage fiber analyses (apparatus, reagents, procedures, and some applications); US Agricultural Research Service: 1970.

- Menke, K.H. Estimation of the energetic feed value obtained from chemical analysis and in vitro gas production using rumen fluid. Anim Res Dev 1988, 28, 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Z.; Mason, D.; Brooks, A.; Griffith, G.; Merry, R.; Theodorou, M. An automated system for measuring gas production from forages inoculated with rumen fluid and its use in determining the effect of enzymes on grass silage. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2000, 83, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mould, F.; Kliem, K.; Morgan, R.; Mauricio, R. In vitro microbial inoculum: A review of its function and properties. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2005, 123, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mould, F.; Morgan, R.; Kliem, K.; Krystallidou, E. A review and simplification of the in vitro incubation medium. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2005, 123, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Instruments, B. Gas Endeavour III. Available online: https://bpcinstruments.com/bpc_products/gas-

endeavour-iii/ (accessed on.

- Liu, J.; van Gorp, R.; Nistor, M. The new Gas Endeavour system from Bioprocess Control AB for in vitro

assessment of animal feeds. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Feed Science Conference,

Uppsala, Sweden, 2018; pp. 12-13.

- Üveges, Z.; Damak, M.; Klátyik, S.; Ramay, M.W.; Fekete, G.; Varga, Z.; Gyuricza, C.; Székács, A.; Aleksza, L. Biomethane Potential in Anaerobic Biodegradation of Commercial Bioplastic Materials. Fermentation 2023, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świechowski, K.; Rasaq, W.A.; Syguła, E. Anaerobic digestion of brewer’s spent grain with biochars—biomethane production and digestate quality effects. Frontiers in Energy Research 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, J.; Liao, Q.; Fu, Q.; Liu, Z. Enhanced biohydrogen and biomethane production from Chlorella sp. with hydrothermal treatment. Energy Conversion and Management 2020, 205, 112373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Reyes, J.; Buitrón, G.; Moreno-Andrade, I.; Tapia-Rodríguez, A.C.; Palomo-Briones, R.; Razo-Flores, E.; Aguilar-Juárez, O.; Arreola-Vargas, J.; Bernet, N.; Braga, A.F.M.; et al. Standardized protocol for determination of biohydrogen potential. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolci, G.; Venturelli, V.; Catenacci, A.; Ciapponi, R.; Malpei, F.; Romano Turri, S.E.; Grosso, M. Evaluation of the anaerobic degradation of food waste collection bags made of paper or bioplastic. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 305, 114331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.M.D.; de Almeida, J.F.M.; Escócio, V.A.; da Silva, A.L.N.; de Sousa, A.M.F.; Visconte, L.L.Y.; Furtado, C.R.G.; Pacheco, E.B.A.V.; Leite, M.C.A.M. Evaluation of rheological behavior, anaerobic and thermal degradation, and lifetime prediction of polylactide/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/powdered nitrile rubber blends. Polymer Bulletin 2019, 76, 2899–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Strömberg, S.; Gorp, J.v.; Nistor, M. Importance of accurate and correct quantitative measurements in a new volumetric gas measuring technique for in vitro assessment of ruminant feeds. 2016.

- Elgemark, E. Intensively processed silage using Bio-extruder. 2019.

- Psenovschi, G.; Vintila, A.C.N.; Neamtu, C.; Vlaicu, A.; Capra, L.; Dumitru, M.; Enascuta, C.-E. Biogas Production Using “Gas Endeavour” Automatic Gas Flow System. Chemistry Proceedings 2023, 13, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Dębowski, M.; Kisielewska, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Zieliński, M. Methane Production from Confectionery Wastewater Treated in the Anaerobic Labyrinth-Flow Bioreactor. Energies 2023, 16, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Walery, M. Aquatic Macrophyte Biomass Periodically Harvested Form Shipping Routes and Drainage Systems in a Selected Region of Poland as a Substrate for Biogas Production. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 4184. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.; Nishi, K.; Koyama, M.; Toda, T.; Matsuyama, T.; Ida, J. Combined effects of various conductive materials and substrates on enhancing methane production performance. Biomass and Bioenergy 2023, 178, 106977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syguła, E.; Rasaq, W.A.; Świechowski, K. Effects of Iron, Lime, and Porous Ceramic Powder Additives on Methane Production from Brewer’s Spent Grain in the Anaerobic Digestion Process. Materials 2023, 16, 5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwarc, D.; Nowicka, A.; Zieliński, M. Comparison of the Effects of Pulsed Electric Field Disintegration and Ultrasound Treatment on the Efficiency of Biogas Production from Chicken Manure. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8154. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinheinz, G.; Hernandez, J. Comparison of two laboratory methods for the determination of biomethane potential of organic feedstocks. Journal of microbiological methods 2016, 130, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nolan, P.; Luostarinen, S.; Doyle, E.; O'kiely, P. Anaerobic digestion of perennial ryegrass prepared by cryogenic freezing versus thermal drying methods, using contrasting in vitro batch digestion systems. Renewable energy 2016, 87, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Rustas, B.; Eriksson, T. Rumen in vitro total gas production of timothy, red clover and the mixed silage after extrusion. 2018.

- Quarantelli, A.; Renzi, M.; Simoni, M.; Martuzzi, F.; Rosato, M.; Zambini, E.M.; Righi, F. Evaluation of an additive capable to improve ruminal fermentations through the use of an automated gas production system. ITALIAN JOURNAL OF ANIMAL SCIENCE 2019, 18, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bertignon, M. Analisi di additivi in grado di migliorare le fermentazioni ruminali attraverso l’uso di un sistema automatizzato di gas production. Università di Parma. Dipartimento di Scienze Medico-Veterinarie, 2020.

- Vigh, A.; Criste, A.; Gragnic, K.; Moquet, L.; Gerard, C. Ruminal solubility and bioavailability of inorganic trace mineral sources and effects on fermentation activity measured in vitro. Agriculture 2023, 13, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muragijeyezu, P.C. Investigating the potential of different dietary fibers to stimulate butyrate production in vitro. 2020.

- Diamond, L.W.; Akinfiev, N.N. Solubility of CO2 in water from− 1.5 to 100 C and from 0.1 to 100 MPa: evaluation of literature data and thermodynamic modelling. Fluid phase equilibria 2003, 208, 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Tian, H.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Liu, A.; Yang, L. Solubility of CO2 in water and NaCl solution in equilibrium with hydrate. Part I: Experimental measurement. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2016, 409, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen, B.; Hansen, H.H. Differences in Donor Animal Production Stage Affect Repeatability of In Vitro Rumen Fermentation Kinetics. Animals 2023, 13, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Tang, S.; Tan, Z.; Zhou, C.; Han, X.; Kang, J. Comparisons of manual and automated incubation systems: effects of venting procedures on in vitro ruminal fermentation. Livestock Science 2016, 184, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lucile, F.; Cézac, P.; Contamine, F.; Serin, J.-P.; Houssin, D.; Arpentinier, P. Solubility of Carbon Dioxide in Water and Aqueous Solution Containing Sodium Hydroxide at Temperatures from (293.15 to 393.15) K and Pressure up to 5 MPa: Experimental Measurements. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 2012, 57, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliapietra, F.; Cattani, M.; Bailoni, L.; Schiavon, S. In vitro rumen fermentation: Effect of headspace pressure on the gas production kinetics of corn meal and meadow hay. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2010, 158, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.J.; Slupsky, J.D.; Mather, A.E. The solubility of carbon dioxide in water at low pressure. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 1991, 20, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Bueno, I.C.S.; Nozella, E.F.; Goddoy, P.B.; Cabral Filho, S.L.S.; Abdalla, A.L. The influence of head-space and inoculum dilution on in vitro ruminal methane measurements. International Congress Series 2006, 1293, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Yu, Z. Effects of gas composition in headspace and bicarbonate concentrations in media on gas and methane production, degradability, and rumen fermentation using in vitro gas production techniques. Journal of Dairy Science 2013, 96, 4592–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instruments, B. Gas Endeavour Anaerobic Testing Handbook. 2024, 1.0. 1.0.

- Rosato, M.; Quarantelli, A. Comparing ruminal activity measures performed with Gas Endeavour with literature data. Congress of Animal Nutrition ASPA 2016 - Perugia-Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baffa, D.F.; Oliveira, T.S.; Fernandes, A.M.; Camilo, M.G.; Silva, I.N.; Meirelles Júnior, J.R.; Aniceto, E.S. Evaluation of Associative Effects of In Vitro Gas Production and Fermentation Profile Caused by Variation in Ruminant Diet Constituents. Methane 2023, 2, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, T.M.; Pierce, K.M.; Kelly, A.K.; Kenny, D.A.; Lynch, M.B.; Waters, S.M.; Whelan, S.J.; McKay, Z.C. Feed Intake, Methane Emissions, Milk Production and Rumen Methanogen Populations of Grazing Dairy Cows Supplemented with Various C 18 Fatty Acid Sources. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarana, L.; Cattani, M.; Tagliapietra, F.; Bailoni, L.; Schiavon, S. Influence of main dietary chemical constituents on the in vitro gas and methane production in diets for dairy cows. Journal of animal science and biotechnology 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota Graziosi, A.; Colombini, S.; Crovetto, G.M.; Galassi, G.; Chiaravalli, M.; Battelli, M.; Reginelli, D.; Petrera, F.; Rapetti, L. Partial replacement of soybean meal with soybean silage in lactating dairy cows diet: part 1, milk production, digestibility, and N balance. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2022, 21, 634–644. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Hua, D.; Mu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, G. Methane production from the anaerobic digestion of substrates from corn stover: Differences between the stem bark, stem pith, and leaves. The Science of the total environment 2019, 694, 133641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümmel, M.; Lebzien, P. Predicting ruminal microbial efficiencies of dairy rations by in vitro techniques. Livestock production science 2001, 68, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Council, N.R. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Seventh Revised Edition, 2001; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2001; p. 405. [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo, C.; Hafner, S.D.; Teixeira Franco, R.; Benbelkacem, H.; Moretti, P.; Bayard, R.; Buffière, P. How different are manometric, gravimetric, and automated volumetric BMP results? Water 2020, 12, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümmel, M.; Steingass, H.; Becker, K. The relationship between in vitro gas production, in vitro microbial biomass yield and 15N incorporation and its implications for the prediction of voluntary feed intake of roughages. The British journal of nutrition 1997, 77, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).