Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

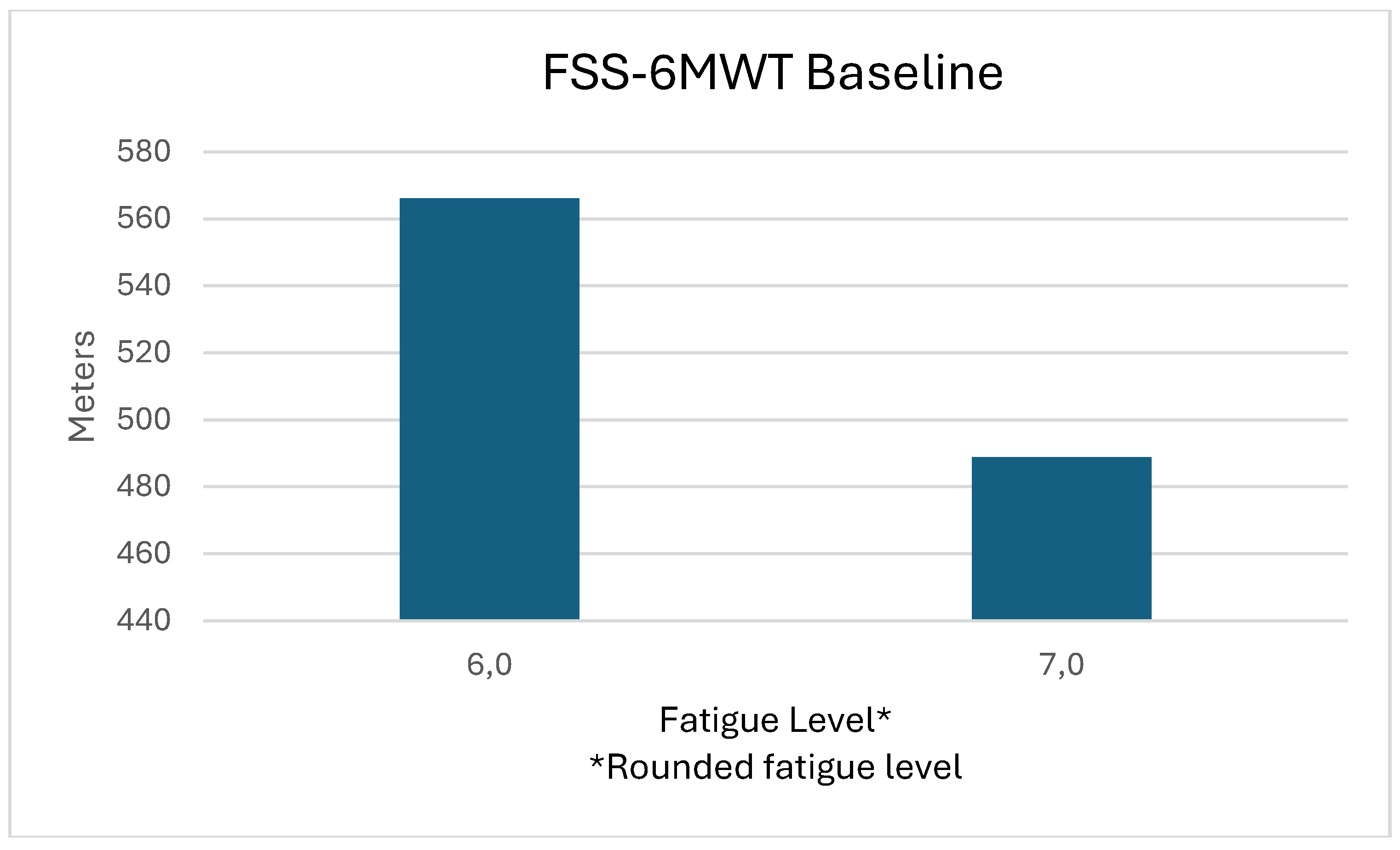

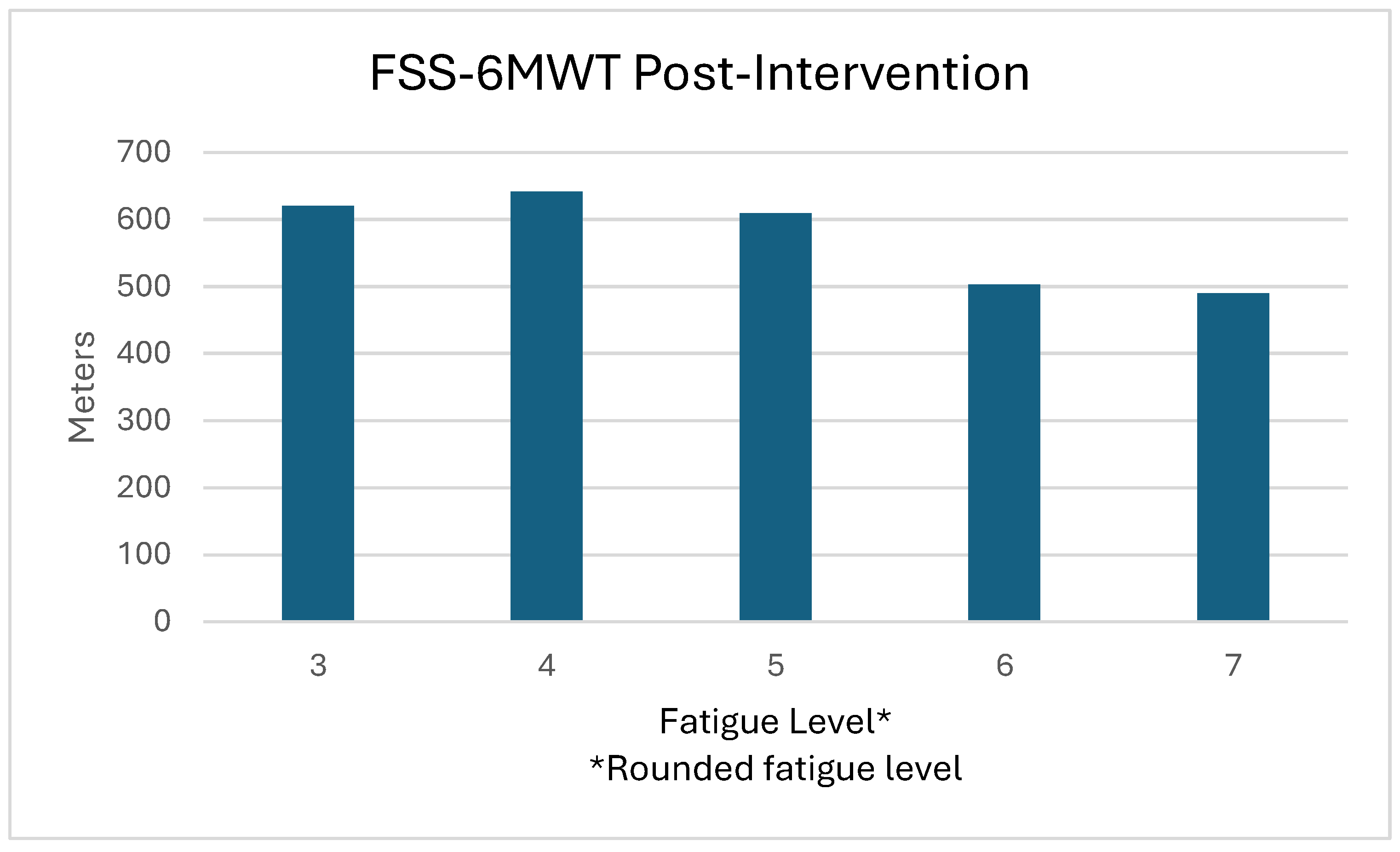

Background and Clinical Significance: Post COVID-19 Condition is a recently recognized syndrome characterized by the persistence of various symptoms, including dyspnea, physical and mental fatigue, and post-exertional malaise. Currently, there is no established treatment or clear consensus on the effectiveness of rehabilitation. In addition, asynchronous telerehabilitation may be an option to reach more of the population with persistent COVID symptoms. Therefore, it is necessary to show the efficacy of this telematic approach and the benefits of a multimodal rehabilitation strategy in these patients. Case Presentation: This study presents a case series of 12 patients (9 women and 3 men) diagnosed with Post COVID-19 Condition and chronic fatigue who underwent rehabilitation through an asynchronous telerehabilitation approach. The 12-week intervention included therapeutic education, physical and respiratory rehabilitation. The most prevalent symptoms were severe fatigue, arthralgias and myalgias, cough and dyspnea and brain fog. The following variables were analyzed: Fatigue, quality of life, dyspnea, respiratory strength, aerobic capacity and upper and lower limb strength. Conclusions: After 12 weeks significant improvements were found in fatigue, aerobic capacity and limb and respiratory strength. However, no improvement was found in dyspnea scores, which did not correlate with respiratory strength. Interestingly, a post-intervention correlation emerged between the distance covered in the aerobic capacity and perceived fatigue, suggesting that asynchronous telerehabilitation could be a viable treatment strategy for these patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Elegibility Criteria

2.2. Cases Characteristics

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Intervention

2.4.1. Therapeutic Education

2.4.2. Pulmonary Rehabilitation

2.4.3. Physical Rehabilitation

2.5. Outcomes

2.5.1. Primary Outcome

2.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

- Quality of life: EQ-5D-5L

- Dyspnea

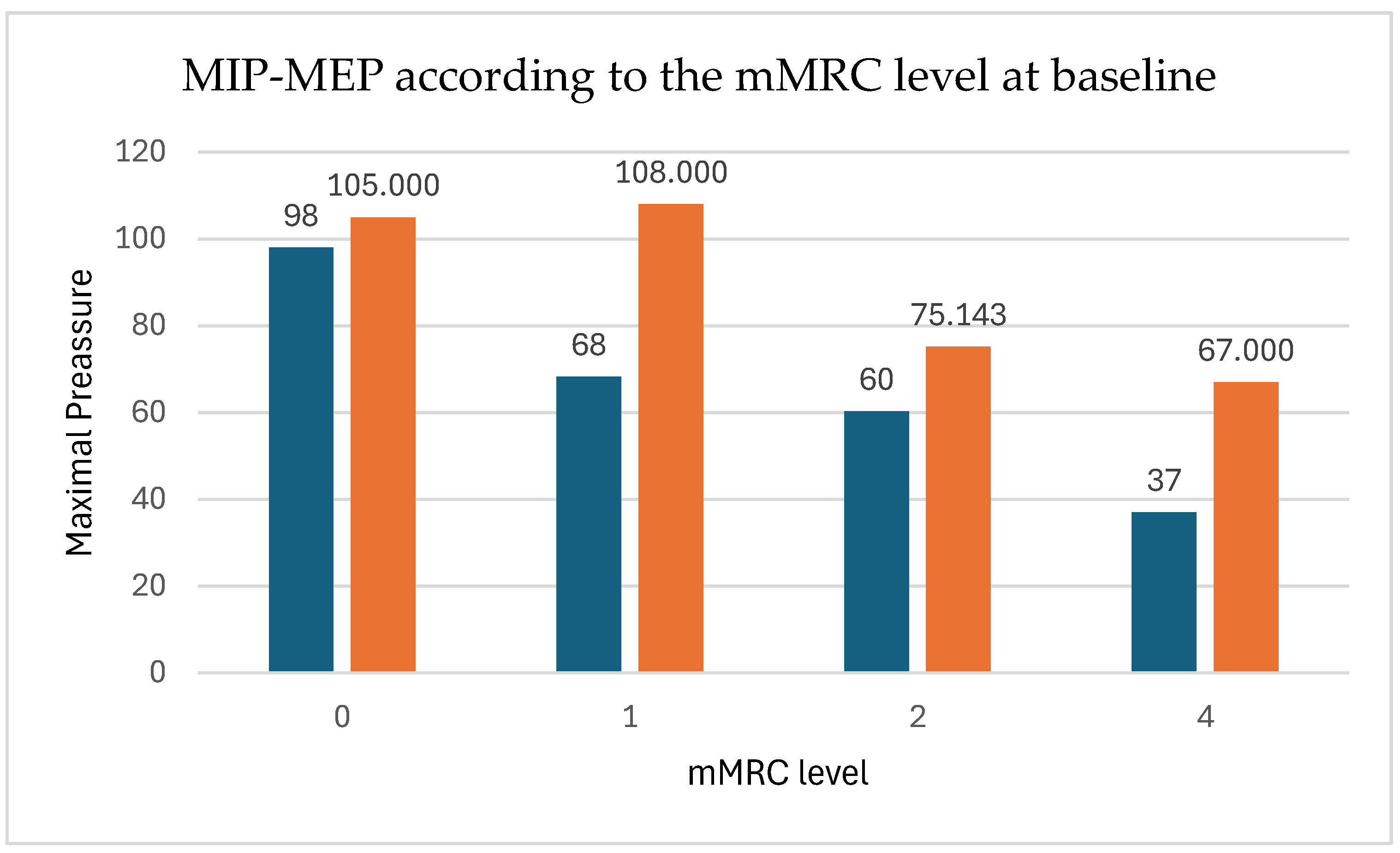

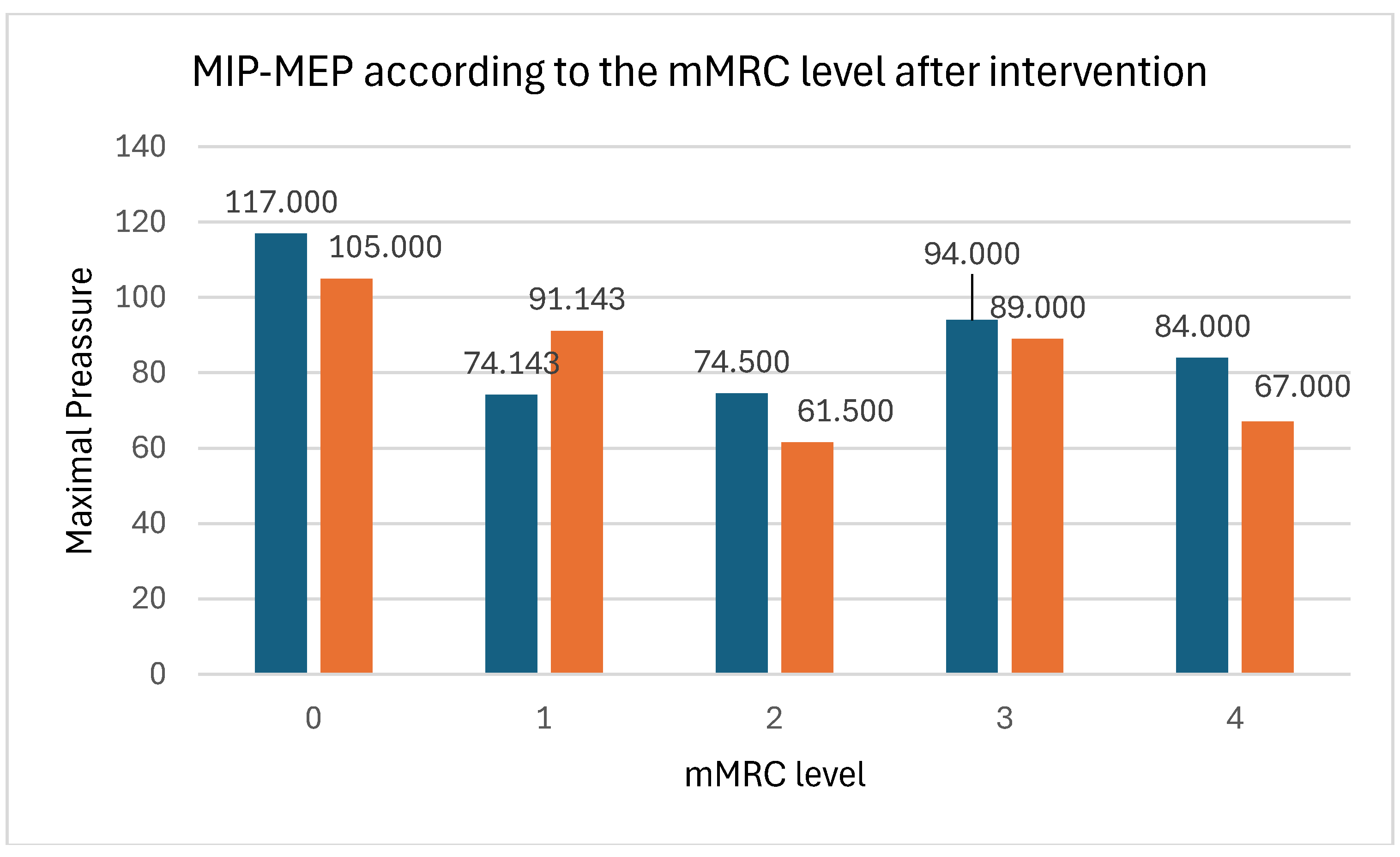

- Respiratory strength

- Functional status

- The Six Minutes Walking Test (6MWT) is a sub-maximal exercise test used and recommended to assess the maximum distance possible for six minutes, in a 30-meter corridor, allowing the patient to rest as needed. It has been shown to be reliable [34,35,36]. The distance covered by each participant is compared with the estimated distance for their gender, weight, and age according to the Troosters equation [37].

- The 30” Sit to Stant Test (STST) is part of the Senior Fitness Test (SFT) designed by Rikli and Jones. It has been used as a stand-alone test, especially to assess weakness in respiratory patients who have passed COVID-19 [38,39,40]. For the 30”STST, participants were seated in a chair with their feet flat on the floor and arms crossed over their shoulders, performing as many squats as possible within 30 seconds [41].

- The 30”Arm Curl Test (ACT) is part of the SFT and is also used as a stand-alone test to assess strength. It has been shown to be reliable [38,39] in deconditioned patients and in post-COVID-19 patients [42]. The higher the number of repetitions, the better the strength. During the 30”ACT, participants were seated in a chair and performed as many elbow flexions as possible within 30 seconds using their dominant arm, with women lifting a 2kg weight and men a 4kg weight.

2.6. Stastistical Analysis

2.7. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, W. Coronavirus desease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 condition. World Health Organ. 2023.

- Soriano, J.B.; Ancochea, J. On the new post COVID-19 condition. Arch. Bronconeumol. Engl. Ed. 2021, 57, 735–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Hughes, S.E.; Turner, G.; Rivera, S.C.; McMullan, C.; Chandan, J.S.; Haroon, S.; Price, G.; Davies, E.H.; Nirantharakumar, K.; et al. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: A review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis 2021. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Sivan, M.; Perlowski, A.; Nikolich, J.Ž. Long COVID: A clinical update. The Lancet 2024, 404, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Hernández, A.; González-Rodríguez, V.D.R.; López-Flores, A.; Kammar-García, A.; Mancilla-Galindo, J.; Vera-Lastra, O.; Jiménez-López, J.L.; Peralta Amaro, A.L. [Stress, anxiety, and depression in health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic]. Rev. Medica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2022, 60, 556–562. [Google Scholar]

- Erraoui, M.; Lahlou, L.; Fares, S.; Abdelnaby, A.; Nainia, K.; Ajdi, F.; Khabbal, Y. The impact of COVID-19 on the quality of life of southern Moroccan doctors : A gender-based approach. Rev. DÉpidémiologie Santé Publique 2022, 70, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi, Á.; Ladrón, R.; Ybarra-Falcón, C.; Tobar, J.; San Román, J.A. Exercise Intolerance in Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 and the Value of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing- a Mini-Review. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 924819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vontetsianos, A.; Chynkiamis, N.; Gounaridi, M.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Lekka, C.; Zaneli, S.; Anagnostopoulos, N.; Oikonomou, E.; Vavuranakis, M.; Rovina, N.; et al. Exercise Intolerance Is Associated with Cardiovascular Dysfunction in Long COVID-19 Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haunhorst, S.; Dudziak, D.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Seifert, M.; Sotzny, F.; Finke, C.; Behrends, U.; Aden, K.; Schreiber, S.; Brockmann, D.; et al. Towards an understanding of physical activity-induced post-exertional malaise: Insights into microvascular alterations and immunometabolic interactions in post-COVID condition and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Infection 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, H.-J.; Lin, C.-W.; Hsiao, M.-Y.; Wang, T.-G.; Liang, H.-W. Long COVID and rehabilitation. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2024, 123, S61–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloeckl, R.; Zwick, R.H.; Fürlinger, U.; Schneeberger, T.; Leitl, D.; Jarosch, I.; Behrends, U.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Koczulla, A.R. Practical Recommendations for Exercise Training in Patients with Long COVID with or without Post-exertional Malaise: A Best Practice Proposal. Sports Med. - Open 2024, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, D.M.; Wijaya, L.C.G. General rehabilitation for the Post-COVID-19 condition: A narrative review. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2023, 18, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Utrera, C.; Montero-Almagro, G.; Anarte-Lazo, E.; Gonzalez-Gerez, J.J.; Rodriguez-Blanco, C.; Saavedra-Hernandez, M. Therapeutic Exercise Interventions through Telerehabilitation in Patients with Post COVID-19 Symptoms: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matamala-Gomez, M.; Maisto, M.; Montana, J.I.; Mavrodiev, P.A.; Baglio, F.; Rossetto, F.; Mantovani, F.; Riva, G.; Realdon, O. The Role of Engagement in Teleneurorehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Qu, Y. Do patients with and survivors of COVID-19 benefit from telerehabilitation? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 954754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pozas, O.; Corbellini, C.; Cuenca-Zaldívar, J.N.; Meléndez-Oliva, É.; Sinatti, P.; Sánchez Romero, E.A. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation versus face-to-face pulmonary rehabilitation on physical function and quality of life in people with post COVID-19 condition: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Martínez, M.Á.; López-Liria, R.; Martínez-Cal, J.; Benzo-Iglesias, M.J.; Torres-Álamo, L.; Rocamora-Pérez, P. Telerehabilitation, A Viable Option in Patients with Persistent Post-COVID Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.R.; Hoffman, M.; Jones, A.W.; Holland, A.E.; Borghi-Silva, A. Effect of Pulmonary Rehabilitation on Exercise Capacity, Dyspnea, Fatigue, and Peripheral Muscle Strength in Patients With Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 105, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Gattoni, C.; Iacovino, M.; Ferguson, C.; Tosolini, J.; Singh, A.; Soe, K.K.; Porszasz, J.; Lanks, C.; Rossiter, H.B.; et al. A Pilot Study on the Effects of Exercise Training on Cardiorespiratory Performance, Quality of Life, and Immunologic Variables in Long COVID. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpallo-Porcar, B.; Calvo, S.; Alamillo-Salas, J.; Herrero, P.; Gómez-Barrera, M.; Jiménez-Sánchez, C. An Opportunity for Management of Fatigue, Physical Condition, and Quality of Life Through Asynchronous Telerehabilitation in Patients After Acute Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 105, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupp, L.B. The Fatigue Severity Scale: Application to Patients With Multiple Sclerosis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arch. Neurol. 1989, 46, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, H.; Shao, S.; Tran, K.C.; Wong, A.W.; Russell, J.A.; Khor, E.; Nacul, L.; McKay, R.J.; Carlsten, C.; Ryerson, C.J.; et al. Evaluating fatigue in patients recovering from COVID-19: Validation of the fatigue severity scale and single item screening questions. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Dlugonski, D.; Pilutti, L.A.; Sandroff, B.M.; Klaren, R.; Motl, R.W. Psychometric properties of the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 331, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Moro-López-Menchero, P.; Cancela-Cilleruelo, I.; Pardo-Hernández, A.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Gil-de-Miguel, Á. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the EuroQol-5D-5L in previously hospitalized COVID-19 survivors with long COVID. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestall, J.C.; Paul, E.A.; Garrod, R.; Garnham, R.; Jones, P.W.; Wedzicha, J.A. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999, 54, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formiga, M.F.; Dosbaba, F.; Hartman, M.; Batalik, L.; Senkyr, V.; Radkovcova, I.; Richter, S.; Brat, K.; Cahalin, L.P. Role of the Inspiratory Muscles on Functional Performance From Critical Care to Hospital Discharge and Beyond in Patients With COVID-19. Phys. Ther. 2023, 103, pzad051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymerich, C.; Rodríguez-Lázaro, M.; Solana, G.; Farré, R.; Otero, J. Low-Cost Open-Source Device to Measure Maximal Inspiratory and Expiratory Pressures. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 719372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lista-Paz, A.; Langer, D.; Barral-Fernández, M.; Quintela-del-Río, A.; Gimeno-Santos, E.; Arbillaga-Etxarri, A.; Torres-Castro, R.; Vilaró Casamitjana, J.; Varas De La Fuente, A.B.; Serrano Veguillas, C.; et al. Maximal Respiratory Pressure Reference Equations in Healthy Adults and Cut-off Points for Defining Respiratory Muscle Weakness. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023, 59, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente Maestú, L.; García De Pedro, J. Las pruebas funcionales respiratorias en las decisiones clínicas. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2012, 48, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente Maestú, L. Manual SEPAR de procedimientos; Luzán 5: Madrid, 2002; ISBN 978-84-7989-152-7. [Google Scholar]

- Spruit, M.A.; Singh, S.J.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Rochester, C.; Hill, K.; Holland, A.E.; Lareau, S.C.; Man, W.D.-C.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Key Concepts and Advances in Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, e13–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uszko-Lencer, N.H.M.K.; Mesquita, R.; Janssen, E.; Werter, C.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.-P.; Pitta, F.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Spruit, M.A. Reliability, construct validity and determinants of 6-minute walk test performance in patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 240, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcuri, J.F.; Borghi-Silva, A.; Labadessa, I.G.; Sentanin, A.C.; Candolo, C.; Pires Di Lorenzo, V.A. Validity and Reliability of the 6-Minute Step Test in Healthy Individuals: A Cross-sectional Study. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2016, 26, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.R.; Gulart, A.A.; Venâncio, R.S.; Munari, A.B.; Gavenda, S.G.; Martins, A.C.B.; Mayer, A.F. Performance difference on the six-minute walk test on tracks of 20 and 30 meters for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Validity and reliability. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021, 25, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troosters, T.; Gosselink, R.; Decramer, M. Six minute walking distance in healthy elderly subjects. Eur. Respir. J. 1999, 14, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikli, R.E.; Jones, C.J. Development and Validation of Criterion-Referenced Clinically Relevant Fitness Standards for Maintaining Physical Independence in Later Years. The Gerontologist 2013, 53, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, B.; Stanghelle, J.K. The Senior Fitness Test. J. Physiother. 2015, 61, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Mejía, E.A.; González, M.E.O.; Castillo, L.Y.R.; Niño, D.M.V.; Pacheco, A.M.S.; Sandoval-Cuellar, C. Reliability of Senior Fitness Test version in Spanish for older people in Tunja-Colombia.

- McAllister, L.S.; Palombaro, K.M. Modified 30-Second Sit-to-Stand Test: Reliability and Validity in Older Adults Unable to Complete Traditional Sit-to-Stand Testing. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2020, 43, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.M.D.; Spositon, T.; Cerci Neto, A.; Soares, F.M.C.; Pitta, F.; Furlanetto, K.C. Functional tests for adults with asthma: Validity, reliability, minimal detectable change, and feasibility. J. Asthma 2022, 59, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundura, L.; Cezar, R.; André, S.; Campos-Mora, M.; Lozano, C.; Vincent, T.; Muller, L.; Lefrant, J.-Y.; Roger, C.; Claret, P.-G.; et al. Low perforin expression in CD8+ T lymphocytes during the acute phase of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection predicts long COVID. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1029006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, C.G.; Peterson, D.; Armstrong, J.; Knox, K.; Roy, A. Potential molecular mechanisms of chronic fatigue in long haul COVID and other viral diseases. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2023, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verveen, A.; Verfaillie, S.C.J.; Visser, D.; Csorba, I.; Coomans, E.M.; Koch, D.W.; Appelman, B.; Barkhof, F.; Boellaard, R.; De Bree, G.; et al. Neurobiological basis and risk factors of persistent fatigue and concentration problems after COVID-19: Study protocol for a prospective case–control study (VeCosCO). BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenveld, T.; Achttien, R.; Smits, M.; De Vries, M.; Van Heerde, R.; Staal, B.; Van Goor, H. ; COVID Rehab Group Feasibility of Virtual Reality Exercises at Home for Post–COVID-19 Condition: Cohort Study. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 9, e36836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Herrera, S.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Sánchez-Recio, R.; Méndez-López, F.; Magallón-Botaya, R.; Sánchez-Arizcuren, R. Effectiveness of an online multimodal rehabilitation program in long COVID patients: A randomized clinical trial. Arch. Public Health 2024, 82, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Crouch, R. Minimal clinically important difference for change in 6-minute walk test distance of adults with pathology: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Yang, L.; Qumu, S.; Situ, X.; Lei, J.; Yu, B.; Liu, B.; Liang, Y.; He, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Tele-rehabilitation in COVID-19 survivors (TERCOV): An investigator-initiated, prospective, multi-center, real-world study. Physiother. Res. Int. 2024, 29, e2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallier, J.-M.; Simon, C.; Bronstein, A.; Dumont, M.; Jobic, A.; Paleiron, N.; Mely, L. Randomized controlled trial of home-based vs. hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation in post COVID-19 patients. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n=12 | ||

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Sex | n (%) | |

| Male | 3 (25.00) | |

| Female | 9 (75.00) | |

| Age | m (SD) | 51 (8.00) |

| BMI (kg/cm) | m (SD) | 27.69 (4.86) |

| Level of education | n (%) | |

| Primary | 0 (0.00) | |

| Secondary | 6 (50.00) | |

| University | 6 (50.00) | |

| Health Data | ||

| Time with symptoms (days) | n (%) | >365 (100.00) |

| Emotional disorder | n (%) | 2 (16.70) |

| Other pathologies | ||

| Diabetes | 2 (16.70) | |

| Obesity | 1 (8.30) | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1 (8.30) | |

| Hypertension | 2 (16.70) | |

| No pathology | 6 (50.00) |

| Nº Case | Age | Gender | BMI | Level of Education | Metabolic Syndrome | Emotional Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 35 | Female | 30.86 | University | Obesity | Anxiety, Depression |

| Case 2 | 54 | Female | 30.03 | Secondary | Obesity | None |

| Case 3 | 52 | Female | 32.88 | Secondary | Obesity, Hypercolesterolemia | None |

| Case 4 | 52 | Female | 29.86 | University | Hypertension | None |

| Case 5 | 39 | Female | 21.91 | Secondary | None | None |

| Case 6 | 63 | Male | 31.12 | Secondary | Hypertension, Obesity | Depression |

| Case 7 | 47 | Female | 20.7 | University | None | None |

| Case 8 | 58 | Female | 23.53 | University | Diabetes T2 | None |

| Case 9 | 57 | Male | 35.27 | Secondary | Obesity, Diabetes T2 | None |

| Case 10 | 51 | Female | 23.73 | University | None | None |

| Case 11 | 56 | Female | 29.62 | University | Hypercolesterolemia | None |

| Case 12 | 47 | Male | 22.78 | Secondary | None | None |

| Nº Case | General | Respiratory | Cardiovascular | Neurological | Gastrointestinal | Musculoskeletal | Oto-laryngology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Fatigue | None | None | None | None | Arthralgia, Myalgia | None |

| Case 2 | Fatigue, Profuse sweating | Cough, Dyspnoea | POTS, palpitations | Headaches, paraesthesias, brain fog, lack of concentration | Nausea, Diarrhoea, Pyrosis | Arthralgia, Myalgia | Dizziness |

| Case 3 | Fatigue | Cough, Dyspnoea | None | Headaches, paraesthesias | None | Arthralgia, Myalgia | Dysphonia, Dizziness |

| Case 4 | Fatigue, Fever | Cough, Dyspnoea | POTS, palpitations | Headaches, paraesthesias, brain fog, lack of concentration | None | Arthralgia, Myalgia | None |

| Case 5 | Fatigue | None | Palpitations | Headaches, paraesthesias, brain fog, lack of concentration | Abdominal Pain, Diarrhoea | Arthralgia, Myalgia | None |

| Case 6 | Fatigue | Dyspnoea | POTS | Paresthesias, Anosmia, Brain fog, Lack of concentration | None | Arthralgia, Myalgia | None |

| Case 7 | Fatigue | Dyspnoea | None | Headache, Paresthesias, Brain fog | Diarrhoea | Arthralgia, Myalgia | Dizziness |

| Case 8 | Fatigue | Dyspnoea | None | Paresthesia, Brain fog | None | Arthralgia, Myalgia | None |

| Case 9 | Fatigue | Cough, Dyspnoea | Palpitations | Brain fog, Lack of concentration | None | Arthralgia, Myalgia | Dizziness |

| Case 10 | Fatigue | Cough, Dyspnoea | None | Headaches, paraesthesias, Anosmia, Brain fog, Lack of concentration | Nausea, Diarrhoea | Arthralgia, Myalgia | None |

| Case 11 | Fatigue | Dyspnoea | None | Anosmia, Brain fog, Lack of concentration | None | Arthralgia, Myalgia | None |

| Case 12 | Fatigue | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Pre-intervention n= 12 | Post-intervention n=12 | Difference | p Value | Effect Size Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary variable | ||||||

| FSS | m (SD) | 6.41 (0.51) | 4.85 (1.39) | -1.57 (1.44) | 0.003T | 1.088 |

| Secondary variables | ||||||

| EQ-5D | ||||||

| Coefficient | m (SD) | 0.57 (0.30) | 0.74 (0,16) | 0.17 | 0.246W | |

| VAS | m (SD) | 56.08 (13.33) | 60.00 (14.45) | -3.91 (12.33) | 0.295T | 0.317 |

| mMRC | m (RIQ) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.00 | 0.125M | |

| 6MWT | m (SD) | 527.45 (87.08) | 583.04 (75.99) | 55.58 (37.34) | <0.001T | 1.488 |

| 30” STST | m (SD) | 14.00 (4.00) | 18.00 (4.00) | 4.00 (4.00) | <0.001T | 1.127 |

| 30” ACT | m (SD) | 16.00 (4.00) | 21.00 (4.00) | 5.00 (4.00) | 0.001T | 1.422 |

| MIP | m (SD) | 63.50 (21.16) | 80.25 (17.29) | 16.75 (15.20) | 0.003T | 1.103 |

| MEP | m (SD) | 85.17 (27.50) | 99.33 (19.77) | 14.17 (19.89) | 0.031T | 1.337 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).