Submitted:

02 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

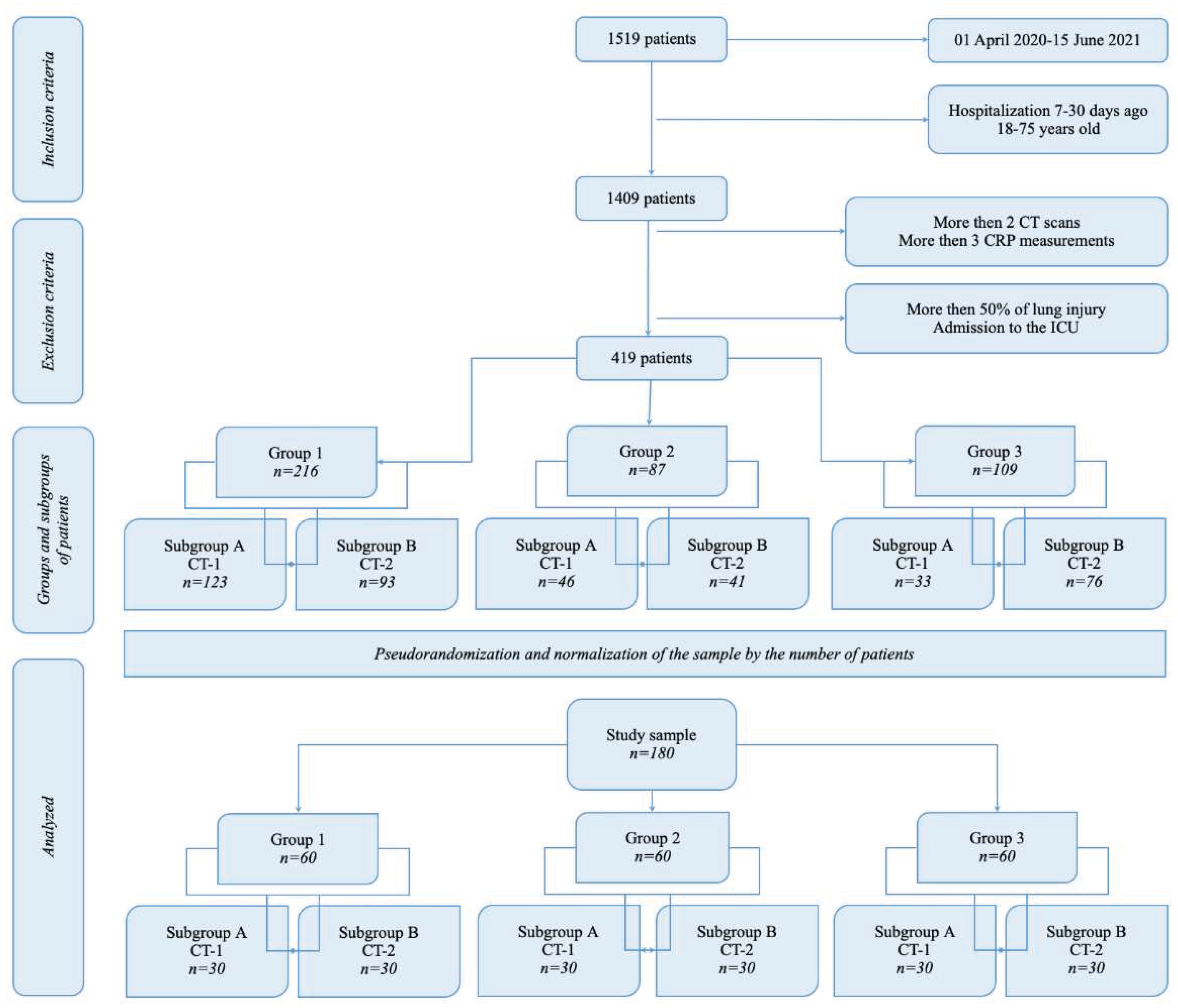

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Ethics

- all patients (age 18-75 y.o.) with COVID-19 admitted to the hospital with mild or moderate COVID-19 (5-50% of lung damage according to CT-scan), hospital length of stay - 7-30 days.

- less than 7 days in hospital for any reason,

- chronic decompensated diseases with extrapulmonary organ dysfunction (tumor progression, liver cirrhosis, congestive heart failure), admission to ICU,

- Patients with less than 2 chest computed tomography studies during hospitalization. Patients without signs of viral pneumonia according to computed tomography (CT-0 severity criteria). Patients with a total lesion of the lungs according to computed tomography (CT-4 severity criteria).

- Patients in whom more than 30 days have passed since the onset of the disease and before hospitalization,

- Patients who received treatment in the ICU, as well as patients who died.

2.2. Rehabilitation Programs

- -

- Positioning with the active patient’s participation and teaching to regularly change the position of the body.

- -

- Verticalization taking into account the mRMI-ICU mobility index.

- -

- Dynamic physical exercises of low intensity: passive, passive-active, and active exercises for small and medium muscle groups, depending on the severity of the disease and the clinical condition of the patient. If a mobility index mRMI-ICU ≥ 6 points, in case of good tolerance of physical activity, exercises involving large muscle groups were added.

- -

- Elements of strength training.

- -

- Exercises to restore balance.

- -

- Physical exercises that increase the mobility of the chest.

- -

- Breathing exercises: an extended exhalation, localized breathing, diaphragmatic breathing; separate dynamic breathing exercises in a gentle mode at a slow pace. Lungs overdistension and fast and strong movements of the chest were avoided.

2.3. Laboratory and Instrumental Examination

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Length of Stay in the Hospital

3.2. Dynamics of Complaints

3.3. Laboratory and Instrumental Data

3.4. The Quality of Life

4. Discussion

4.1. Length of Stay in the Hospital

4.2. Early and Safe Start

4.2. Safety of the Rehabilitation Programs

4.3. Quality of Life

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 6 April 2023 Edition 137 https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---6-april-2023.

- Filgueira, T.O.; Castoldi, A.; Santos, L.E.R.; de Amorim, G.J.; Fernandes, M.S.d.S.; Anastácio, W.d.L.D.N.; Campos, E.Z.; Santos, T.M.; Souto, F.O. The Relevance of a Physical Active Lifestyle and Physical Fitness on Immune Defense: Mitigating Disease Burden, With Focus on COVID-19 Consequences. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 587146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F.; Mangone, M.; Ruiu, P.; Paolucci, T.; Santilli, V.; Bernetti, A. Rehabilitation setting during and after Covid-19: An overview on recommendations. J. Rehabilitation Med. 2021, 53, jrm00141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. Jan 11, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-ofsevere-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected (accessed Feb 8, 2020).

- Filipović, T.; Gajić, I.; Gimigliano, F.; Backović, A.; Hrković, M.; Nikolić, D.; Filipović, A. The role of acute rehabilitation in COVID-19 patients. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabilitation Med. 2023, 59, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyutin, D.; Koneva, E.; Achkasov, E.; Kostenko, A.; Tsvetkova, A.; Elfimov, M.; Eremenko, A.; Bazarov, D.; Shestakov, A.; Korchazhkina, N. Influence of therapeutic exercises and hardware massage in electrostatic field on lung damage in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Vopr. Kurortol. Fizioter. i Lech. fizicheskoi kul'tury 2022, 99, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladlow, P.; Barker-Davies, R.; Hill, O.; Conway, D.; O'Sullivan, O. Use of symptom-guided physical activity and exercise rehabilitation for COVID-19 and other postviral conditions. BMJ Mil. Heal. 2023, e002399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneş, M.; Yana, M.; Güçlü, M.B. Physical activity levels respiratory and peripheral muscle strength and pulmonary function in young post-COVID-19 patients. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2023, 135, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demeco, A.; Marotta, N.; Barletta, M.; Pino, I.; Marinaro, C.; Petraroli, A.; Moggio, L.; Ammendolia, A. Rehabilitation of patients post-COVID-19 infection: a literature review. J. Int. Med Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.; Lee, W.; Cho, H.; Wu, M.; Hu, H.; Kao, K.; Chen, N.; Tsai, Y.; Huang, C. Recovery of pulmonary functions, exercise capacity, and quality of life after pulmonary rehabilitation in survivors of ARDS due to severe influenza A (H1N1) pneumonitis. Influ. Other Respir. Viruses 2018, 12, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Cen, F.; Li, X.; Song, Z.; Peng, M.; Liu, X. Importance of respiratory airway management as well as psychological and rehabilitative treatments to COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1698–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-C.; Chou, W.; Chan, K.-S.; Cheng, K.-C.; Yuan, K.-S.; Chao, C.-M.; Chen, C.-M. Early Mobilization Reduces Duration of Mechanical Ventilation and Intensive Care Unit Stay in Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2017, 98, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Respiratory rehabilitation in elderly patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Ban, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Z. Early pulmonary rehabilitation for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: Experience from an intensive care unit outside of the Hubei province in China. Heart Lung: J. Cardiopulm. Acute Care 2020, 49, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negm, A.M.; Salopek, A.; Zaide, M.; Meng, V.J.; Prada, C.; Chang, Y.; Zanwar, P.; Santos, F.H.; Philippou, E.; Rosario, E.R.; et al. Rehabilitation Care at the Time of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Scoping Review of Health System Recommendations. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 13, 781271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Guo, L.; Tian, F.; Dai, T.; Xing, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, Q. Rehabilitation of patients with COVID-19. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 14, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrose, A.F.; Kurra, A.; Tsirakidis, L.; Hunt, K.C.; Ayers, E.; Gitkind, A.; Yerra, S.; Lo, Y.; Ortiz, N.; Jamal, F.; et al. Rehabilitation and In-Hospital Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2021, 77, e148–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centeno-Cortez, A.K.; Díaz-Chávez, B.; Santoyo-Saavedra, D.R.; Álvarez-Méndez, P.A.; Pereda-Sámano, R.; Acosta-Torres, L.S. Respiratory physiotherapy in post-acute COVID-19 adult patients: Systematic review of literature. Revista Medica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social 2022, 60, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Udina, C.; Ars, J.; Morandi, A.; Vilaró, J.; Cáceres, C.; Inzitari, M. Rehabilitation in adult post-COVID-19 patients in post-acute care with Therapeutic Exercise. J. Frailty Aging 2021, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groah, S.L.; Pham, C.T.; Rounds, A.K.; Semel, J.J. Outcomes of patients with COVID-19 after inpatient rehabilitation. PM&R 2021, 14, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterhoff, G.; Noser, J.; Held, U.; Werner, C.M.L.; Pape, H.-C.; Dietrich, M. Early Operative Versus Nonoperative Treatment of Fragility Fractures of the Pelvis: A Propensity-Matched Multicenter Study. J. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 33, e410–e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Du, C.; et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Chen, M.; Gray, S.R.; Ho, F.K.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C. New versus old guidelines for sarcopenia classification: What is the impact on prevalence and health outcomes? Age Ageing 2019, 49, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Lee, J.; Moon, S.Y.; Jin, H.Y.; Yang, J.M.; Ogino, S.; Song, M.; Hong, S.H.; Ghayda, R.A.; Kronbichler, A.; et al. Physical activity and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe COVID-19 illness and COVID-19 related mortality in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 56, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, H.J.A.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Charlesworth, S.A.; Ivey, A.C.; Warburton, D.E.R. Exercise volume and intensity: a dose–response relationship with health benefits. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupin, D.; Roche, F.; Gremeaux, V.; Chatard, J.C.; Oriol, M.; Gaspoz, J.M.; Barthelemy, J.C.; Edouard, P. Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged >/=60 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawner, C.A.; Ehrman, J.K.; Bole, S.; Kerrigan, D.J.; Parikh, S.S.; Lewis, B.K.; Gindi, R.M.; Keteyian, C.; Abdul-Nour, K.; Keteyian, S.J. Inverse Relationship of Maximal Exercise Capacity to Hospitalization Secondary to Coronavirus Disease 2019. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugliera, L.; Spina, A.; Castellazzi, P.; Cimino, P.; Tettamanti, A.; Houdayer, E.; Arcuri, P.; Alemanno, F.; Mortini, P.; Iannaccone, S. Rehabilitation of COVID-19 patients. J. Rehabilitation Med. 2020, 52, jrm00046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Baldwin, C.; Bissett, B.; Boden, I.; Gosselink, R.; Granger, C.L.; Hodgson, C.; Jones, A.Y.; E Kho, M.; Moses, R.; et al. Physiotherapy management for COVID-19 in the acute hospital setting: clinical practice recommendations. J. Physiother. 2020, 66, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquet, V.; Luczak, C.; Seiler, F.; Monaury, J.; Martini, A.; Ward, A.B.; Gracies, J.-M.; Motavasseli, D.; Lépine, E.; Chambard, L.; et al. Do Patients With COVID-19 Benefit from Rehabilitation? Functional Outcomes of the First 100 Patients in a COVID-19 Rehabilitation Unit. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2021, 102, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanakis, M.; Batalik, L.; Papathanasiou, J.; Dipla, L.; Antoniou, V.; Pepera, G. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs in the era of COVID-19: a critical review. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, S.; Filho, W.J.; Shinjo, S.K.; Ferriolli, E.; Busse, A.L.; Avelino-Silva, T.J.; Longobardi, I.; de Oliveira Júnior, G.N.; Swinton, P.; Gualano, B.; et al. Muscle strength and muscle mass as predictors of hospital length of stay in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: A prospective observational study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Feng, X.; Jiang, C.; Mi, S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Correlation between white blood cell count at admission and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, N.; Hu, J.Y.; Wu, L.L.; Su, G.S.; Zhong, N.S.; Zheng, Z.G. [Pulmonary rehabilitation guidelines in the principle of 4S for patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)]. . 2020, 43, 180–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zbinden-Foncea, H.; Francaux, M.; Deldicque, L.; Hawley, J.A. Does High Cardiorespiratory Fitness Confer Some Protection Against Proinflammatory Responses After Infection by SARS-CoV-2? Obesity 2020, 28, 1378–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltagliati, S.; Sieber, S.; Sarrazin, P.; Cullati, S.; Chalabaev, A.; Millet, G.P.; Boisgontier, M.P.; Cheval, B. Muscle strength explains the protective effect of physical activity against COVID-19 hospitalization among adults aged 50 years and older. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabchi, F.; Mazaheri, R.; Sabeti, K.; Yunesian, M.; Alizadeh, Z.; Ahmadinejad, Z.; Aghili, S.M.; Tavakol, Z. Regular Sports Participation as a Potential Predictor of Better Clinical Outcome in Adult Patients With COVID-19: A Large Cross-Sectional Study. J. Phys. Act. Heal. 2021, 18, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, R.; Zincarelli, C.; Onufrio, M.; D’alessio, A.; Di Ruocco, G.; Di Minno, M.N.D.; Pisacreta, A. Early rehabilitation treatment in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19: Effects on autonomy and quality of life. Physiother. Pr. Res. 2022, 43, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Gomez-Baya, D.; Peralta, M.; Frasquilho, D.; Santos, T.; Martins, J.; Ferrari, G.; de Matos, M.G. The Effect of Muscular Strength on Depression Symptoms in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, T.; Razieh, C.; Zaccardi, F.; Rowlands, A.V.; Seidu, S.; Davies, M.J.; Khunti, K. Obesity, walking pace and risk of severe COVID-19 and mortality: analysis of UK Biobank. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladlow, P.; Holdsworth, D.A.; O’sullivan, O.; Barker-Davies, R.M.; Houston, A.; Chamley, R.; Rogers-Smith, K.; Kinkaid, V.; Kedzierski, A.; Naylor, J.; et al. Exercise tolerance, fatigue, mental health, and employment status at 5 and 12 months following COVID-19 illness in a physically trained population. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 134, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CT at admission | length of stay in hospital, mediana, days | Inter quartile range, days | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1, n=60 | CT-1, n=30 | 13 | 11-15 |

| CТ-2, n=30 | 14 | 12-16 | |

| Group 2, n=60 | CT-1, n=30 | 12 | 9-15 |

| CТ-2, n=30 | 14 | 11-15 | |

| Group 3, n=60 | CT-1, n=30 | 14 | 12-15 |

| CТ-2, n=30 | 16 | 14-21 | |

| CT - computed tomography, CT-1 - up to 25% of lungs injury; CT-2 - 25-50% of lungs injury. | |||

| Complains | At admission | At discharge | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1, n=60 | Weakness, n | 40 | 30 | 0.175 |

| headache, n | 2 | 1 | 0.0001 | |

| shortness of breath, n | 15 | 5 | 0.0001 | |

| cough, n | 18 | 3 | 0.0001 | |

| Group 2, n=60 | weakness, n | 51 | 32 | 0.013 |

| headache, n | 6 | 1 | 0.0001 | |

| shortness of breath, n | 22 | 10 | 0.0001 | |

| cough, n | 30 | 17 | 0.055 | |

| Group 3, n=60 | weakness, n | 47 | 18 | 0.458 |

| headache, n | 6 | 0 | - | |

| shortness of breath, n | 14 | 6 | 0.0001 | |

| cough, n | 27 | 9 | 0.0001 | |

| Total, n=180 | weakness, n | 138 | 80 | 0.0005 |

| headache, n | 14 | 2 | 0.0001 | |

| shortness of breath, n | 51 | 21 | 0.0001 | |

| cough, n | 75 | 29 | 0.0001 | |

| C-reactive protein, mg/l | Mean | CI -95% | CI +95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1, n=60 | at admission | 46.03 | 33.27 | 58.80 |

| at discharge | 6.70 | 3.70 | 9.71 | |

| Group 2, n=60 | at admission | 67.71 | 50.03 | 85.38 |

| at discharge | 4.17 | 4.16 | 11.07 | |

| Group 3, n=60 | at admission | 44.69 | 32.14 | 57.24 |

| at discharge | 9.57 | 4.19 | 14.95 | |

| Total, n=180 | at admission | 52.81 | 44.44 | 61.18 |

| at discharge | 7.96 | 5.65 | 10.28 | |

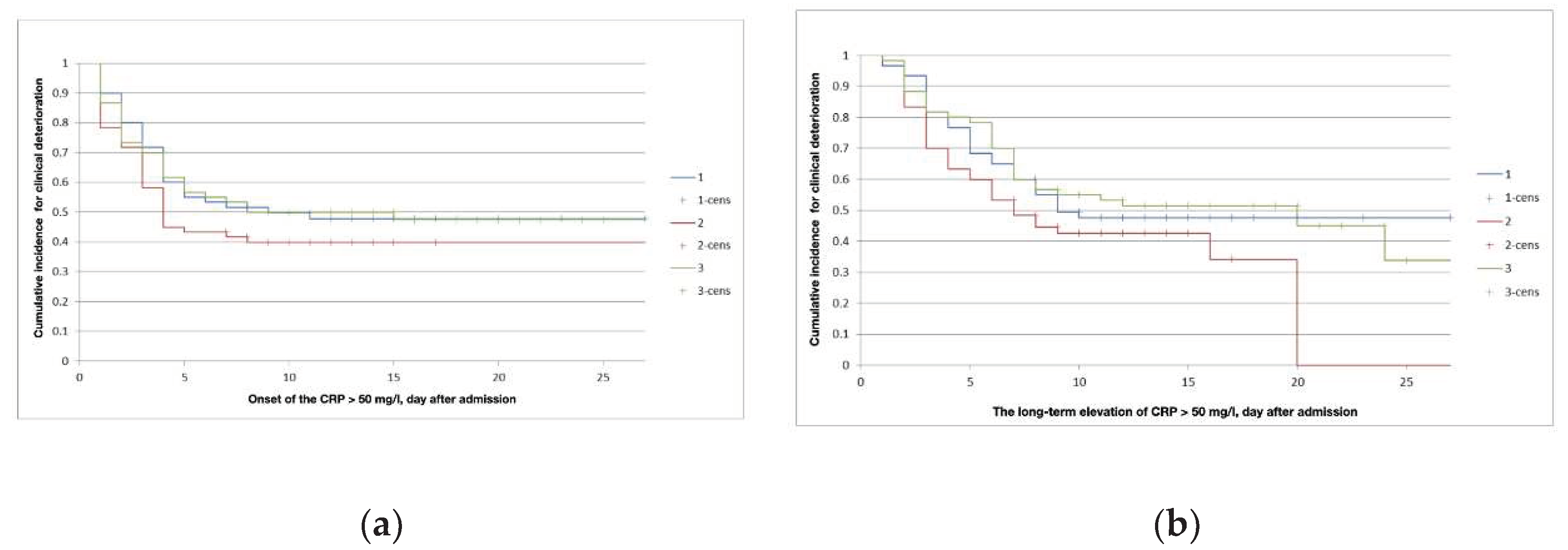

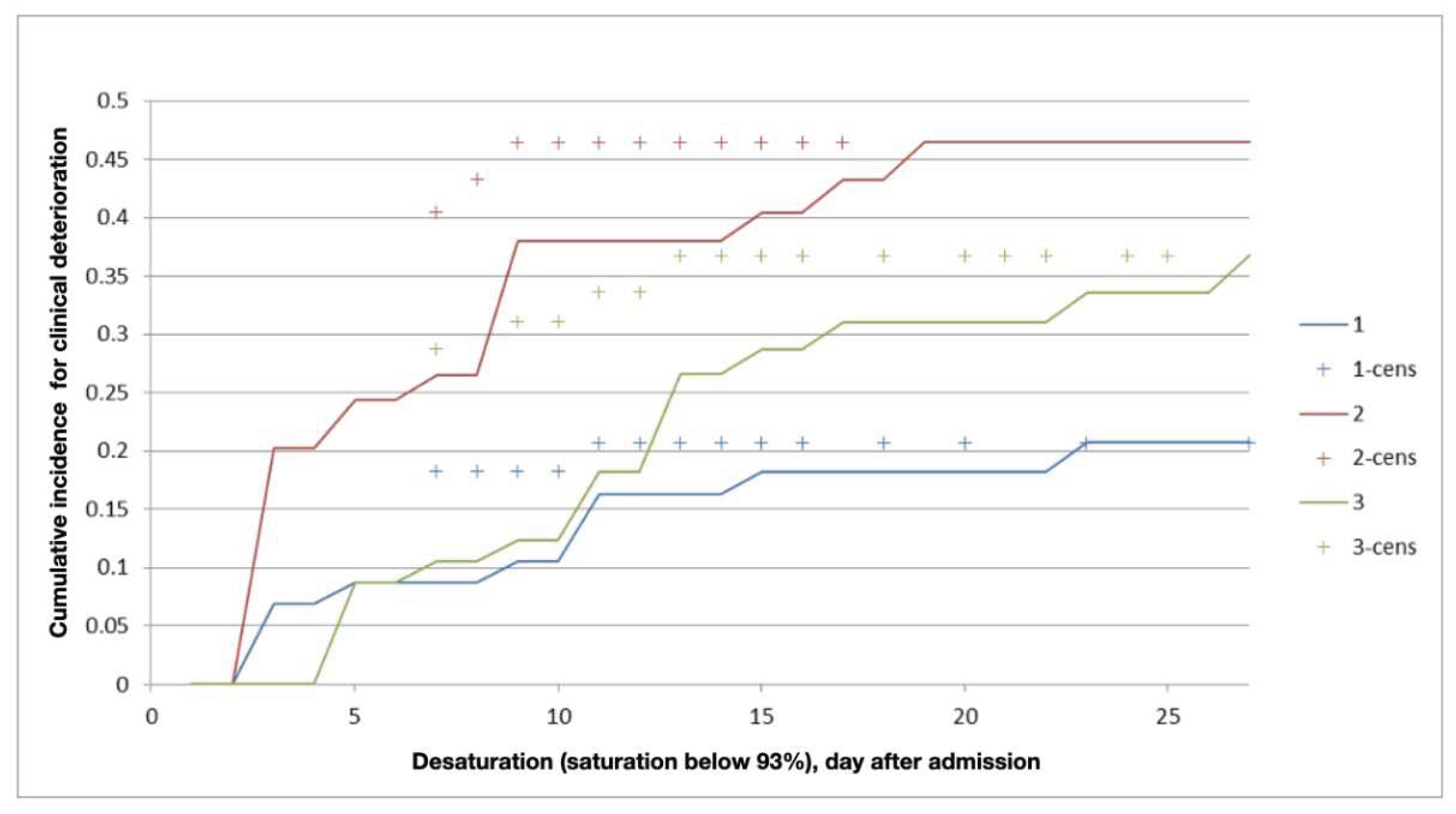

| Group | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | A | B | A | B | A | B |

| The onset of CRP level above 50 mg/l (median, interquartile range), days | 4 (2.5-5) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 2 (1-4) | 3 (1-5) | 2(1.5-4) |

| Duration of CRP level above 50 mg/l (median, interquartile range), days | 4.5 (3-6) | 5 (3-8) | 3.5 (3-5.5) | 3.5(2-6.5) | 6 (3-7) | 6 (2.5-7.5) |

| Component | Level 1 «no problem» |

Level 2 «slight problems» |

Level 3 «moderate problems» |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility, n (%) | 27 (15) | 96 (53) | 57 (32) |

| Self-care, n (%) | 23 (13) | 98 (54) | 59 (33) |

| Usual activities, n (%) | 11 (6) | 93 (52) | 76 (42) |

| Pain/discomfort, n (%) | 11 (6) | 98 (54.5) | 71 (39.5) |

| Anxiety/depression, n (%) | 7 (4) | 85 (47) | 88 (49) |

| p>0.05 | |||

| Level 1 «no problem» |

Level 2 «slight problems» |

Level 3 «moderate problems» |

Р | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety/depression | P-value | |||

| Group 1 A, n (%) | 23 (51) | 18 (40) | 4 (9) | 0.0098 |

| Group 2 A, n (%) | 9 (20) | 27 (60) | 9 (20) | p>0.05 |

| Group 3 A, n (%) | 10 (22) | 25 (56) | 10 (22) | p>0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).