Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

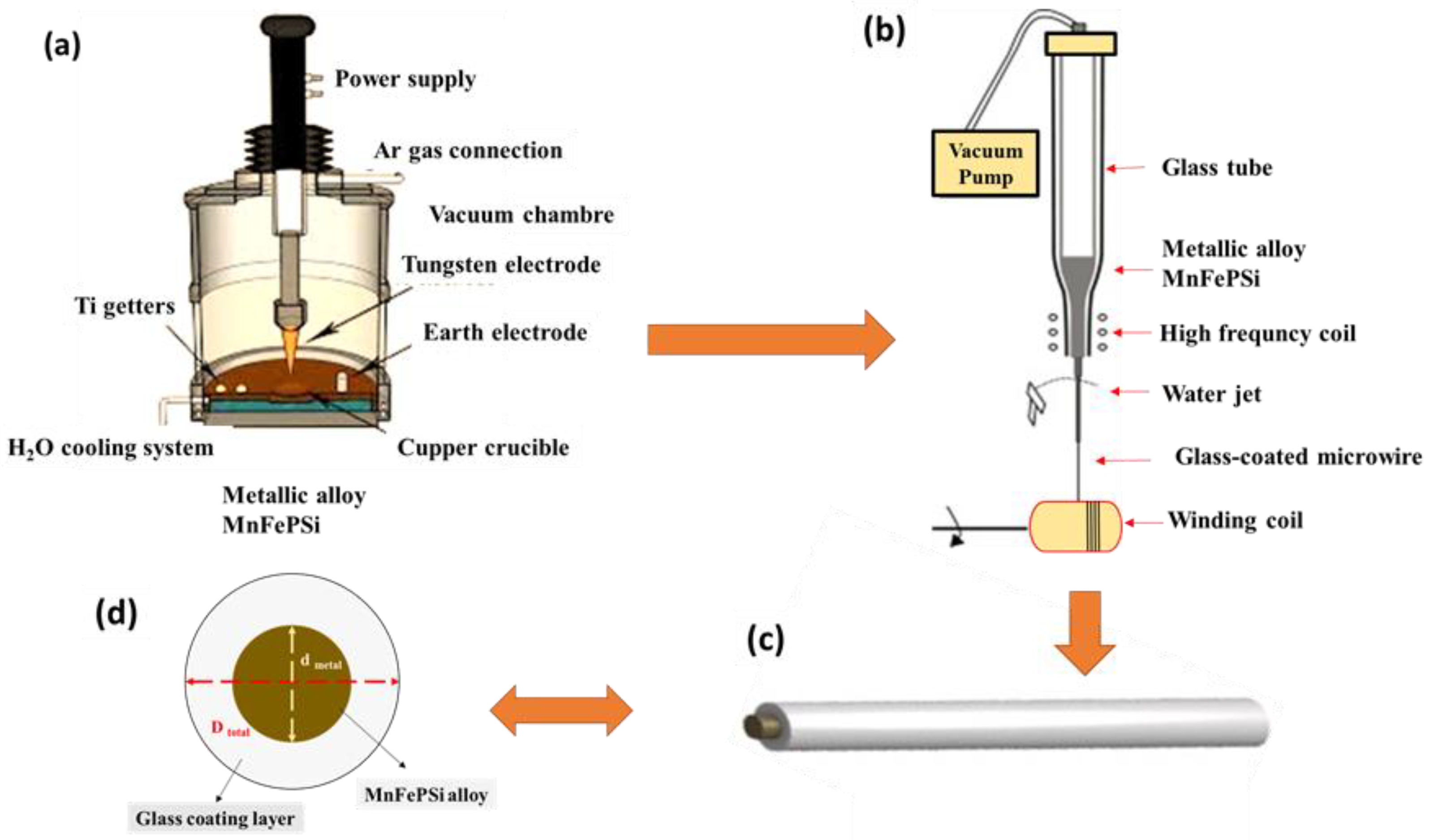

2.1. Fabrication of Bulk Mn-Fe-P-Si-Master Alloy

2.2. Preparation of Mn-Fe-P-Si Glass-Coated Microwires

2.3. Characterization of the Structural and Magnetic Properties

3. Results

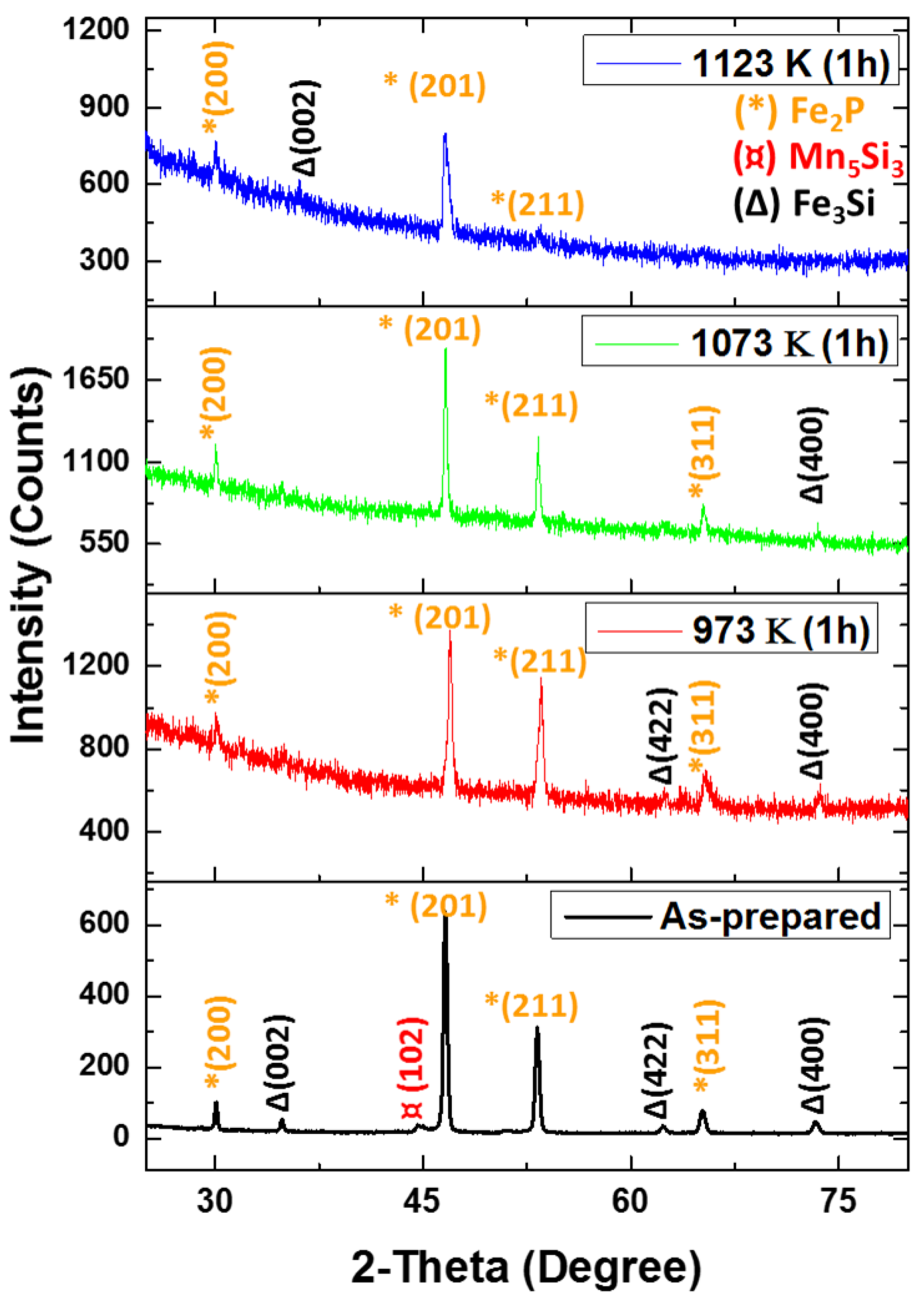

3.1. Structure Characterizations

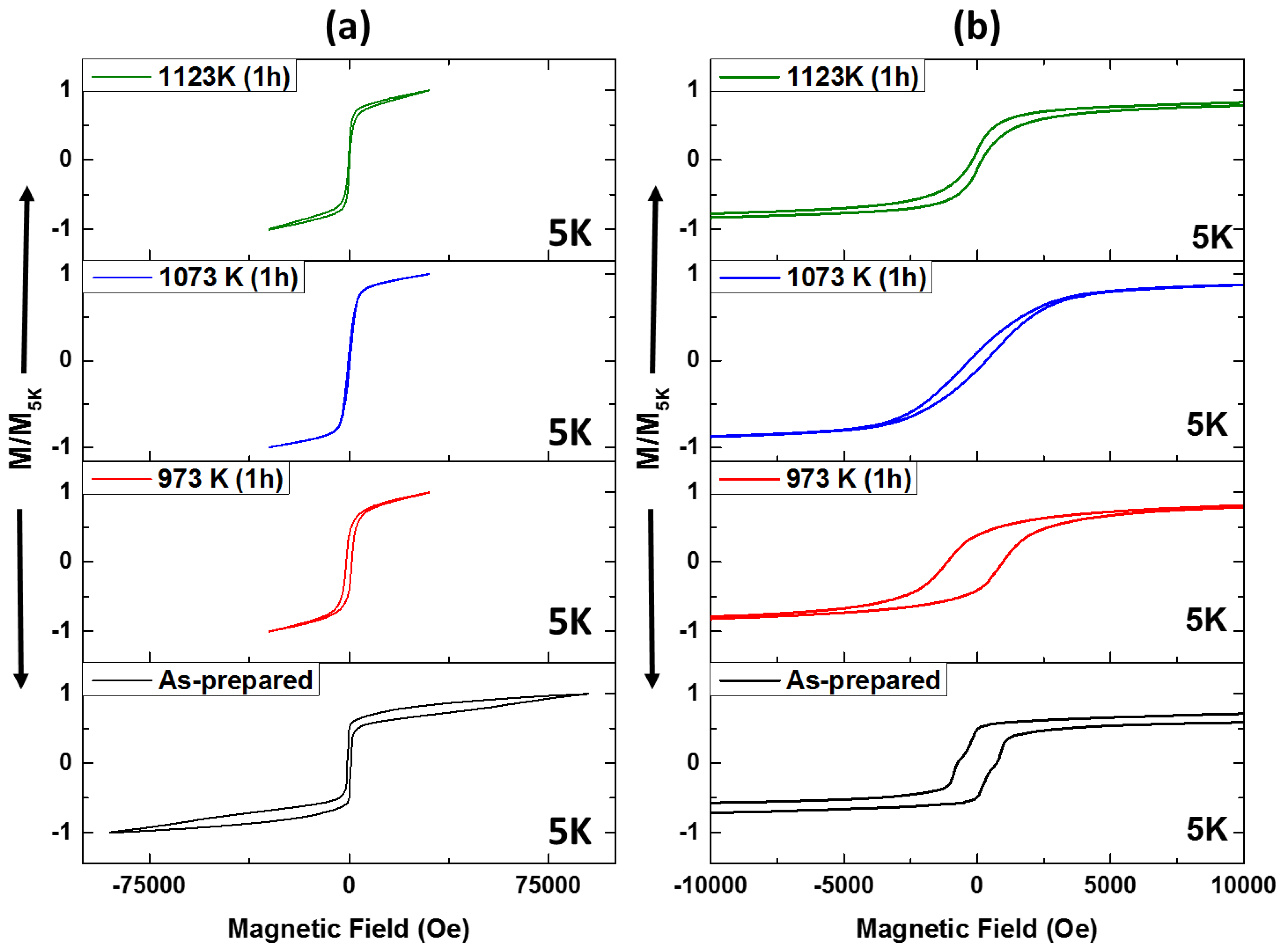

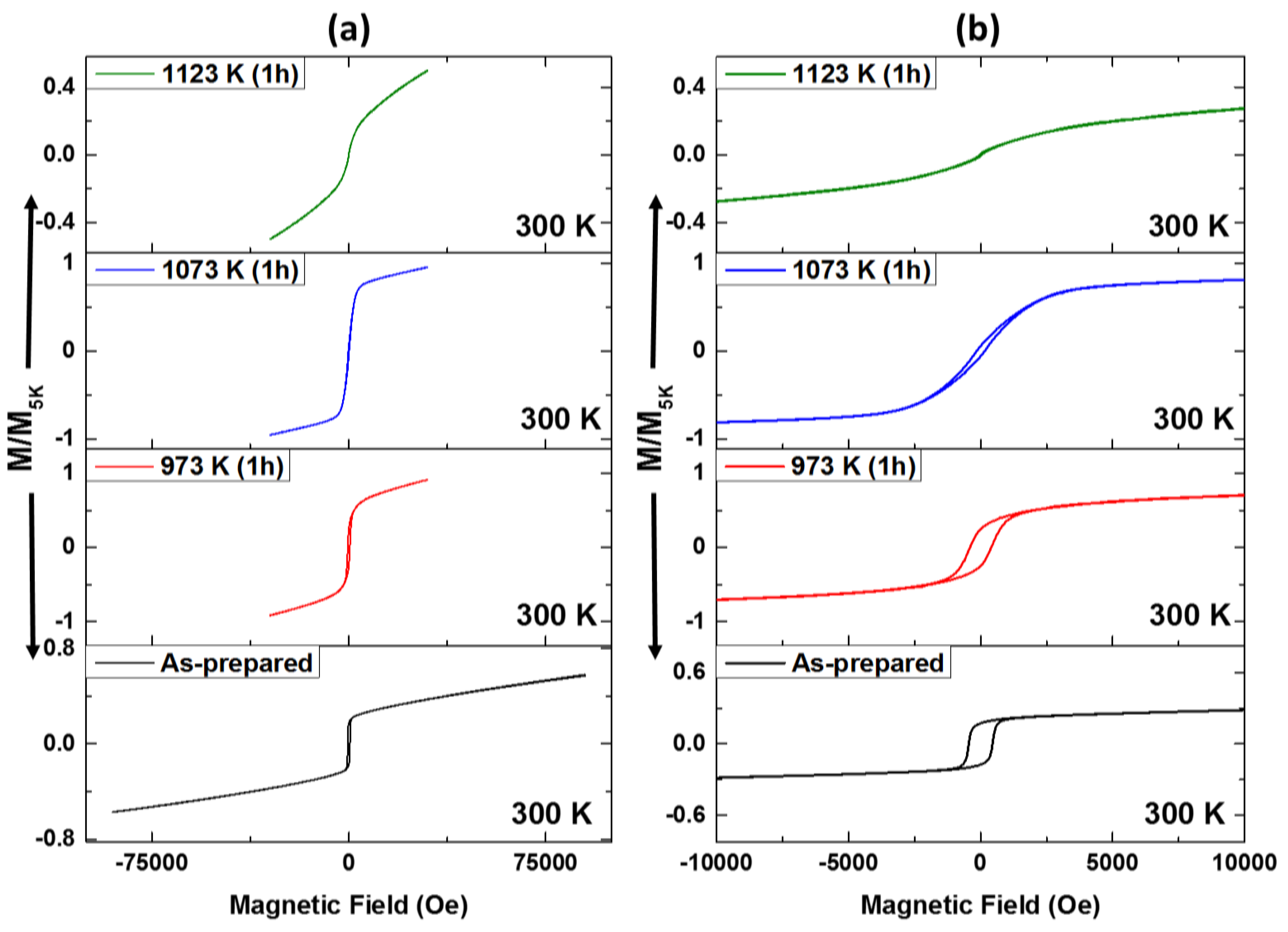

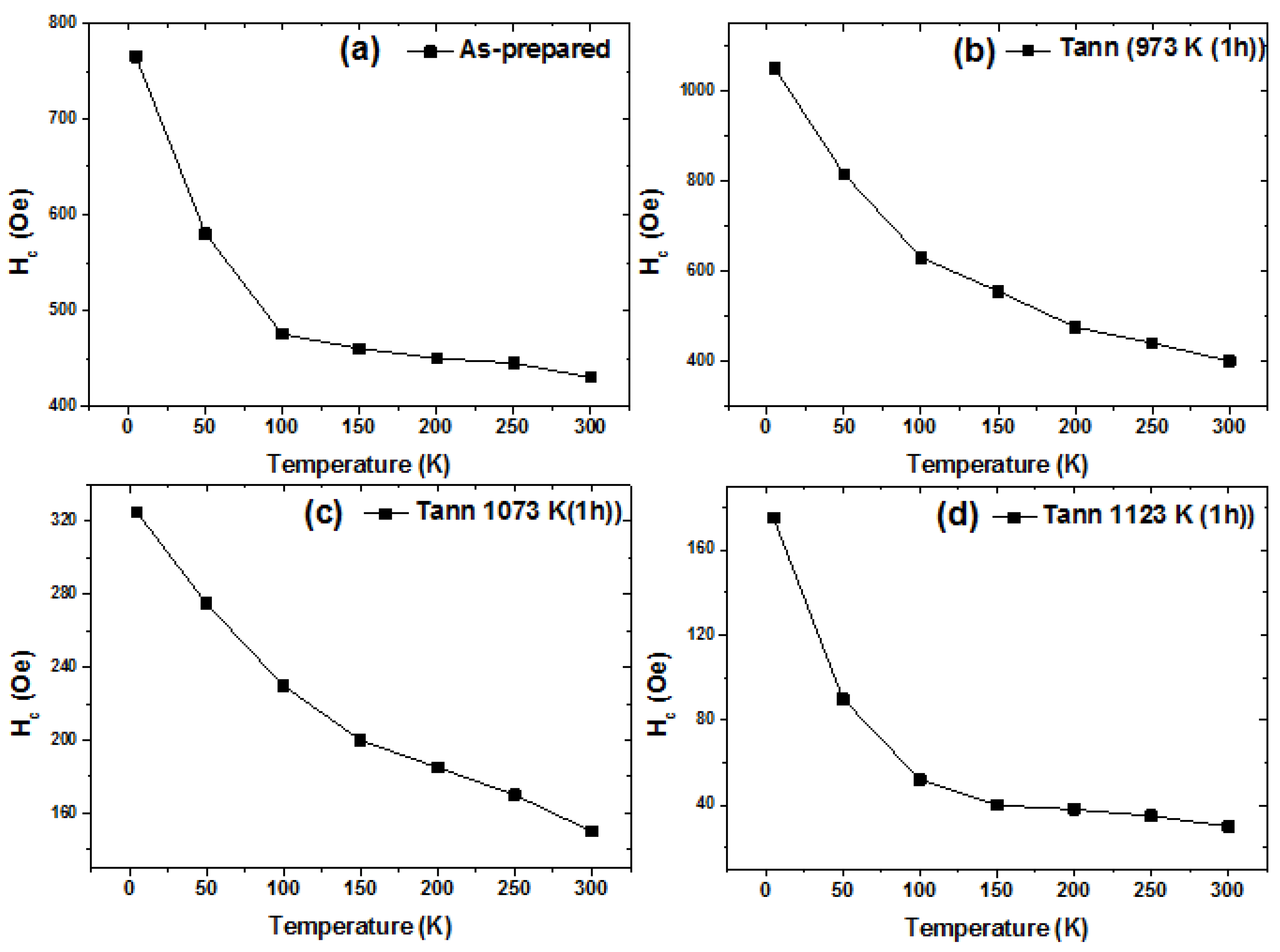

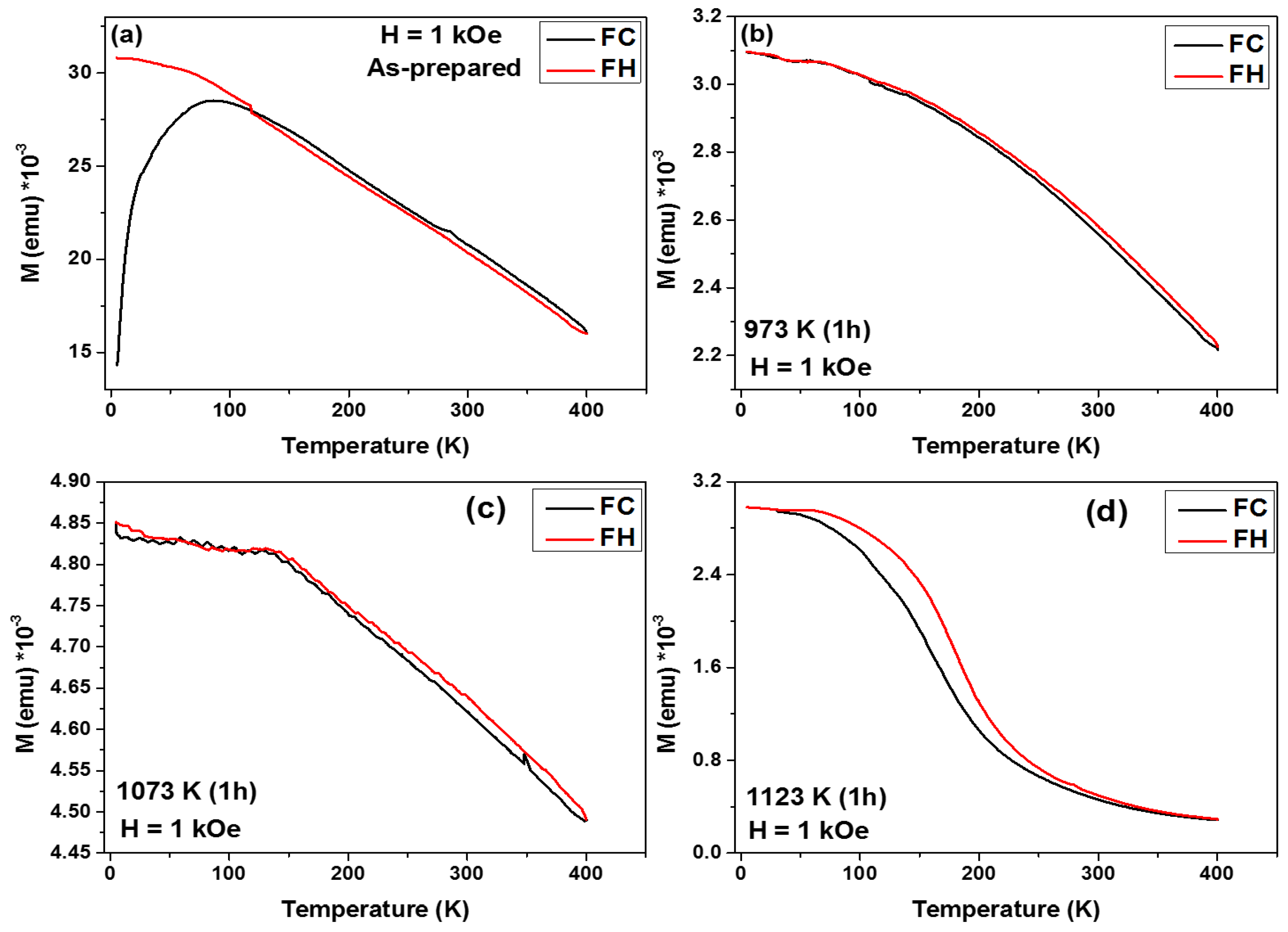

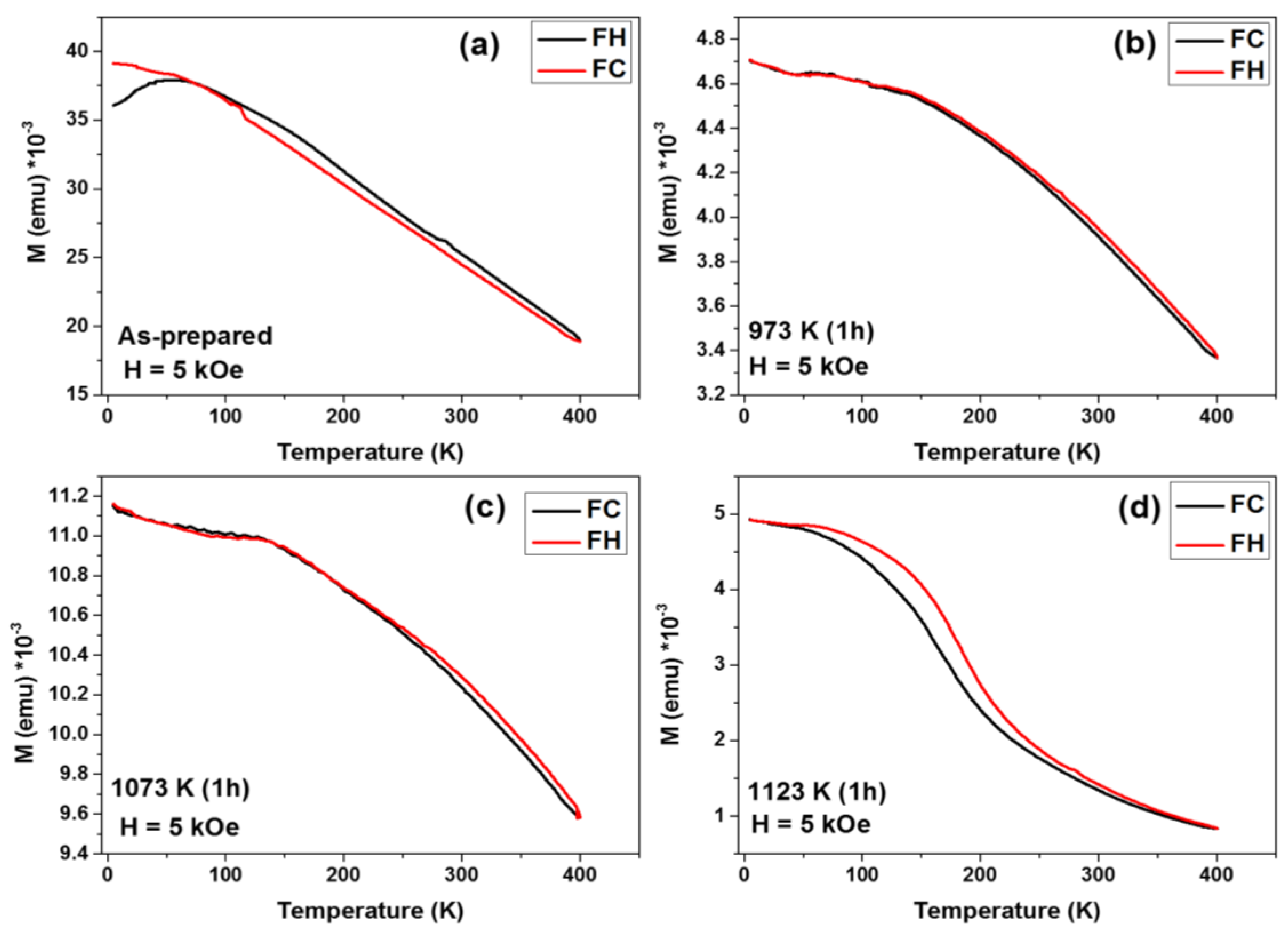

3.2. Magnetic Hysteresis Loops Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, Y. L.; Sellmyer, D. J. Magnetic Nanomaterials: Fundamentals, Synthesis and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2017; pp. 3–546.

- A. Kitanovski, Energy applications of magnetocaloric materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, K. S.; Mandrus, D.; Park, J. G. Magnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Nature 2018, 563, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.V. Trevizoli, J.R. P.V. Trevizoli, J.R. Barbosa, Overview on magnetic refrigeration, in: A. Olabi (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Smart Materials, Elsevier, Oxford, 2022, pp. 395–406. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Phan, S.C. Yu, Review of the magnetocaloric effect in manganite materials. J. Magn. Magn Mater. 2007, 308, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Ju, Y. M.; Xu, J. J.; Yang, Z. Y.; Gao, S.; Hou, Y. L. Magnetic Nanomaterials: Chemical Design, Synthesis, and Potential Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A. H.; Salabas, E. L.; Schuth, F. Magnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, protection, functionalization, and application. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1222–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, V. M. Salaheldeen, V. Zhukova, J. M. Blanco, J. Gonzalez, A. Zhukov. The Impact of High-Temperature Annealing on Magnetic Properties, Structure and Martensitic Transformation of Ni₂MnGa-based Glass-Coated Microwires. Ceramics International, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pacheco, R. Streubel, O. Fruchart, et al. Three-dimensional nanomagnetism. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 15756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Moya, S. Kar-Narayan, N. D. Mathur, Caloric materials near ferroic phase transitions. Nature Materials 2014, 13, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Kadic, G.W. Milton, M. van Hecke, M. Wegener, 3D Metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2019, 1, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Manosa, A. Planes, Materials with giant mechanocaloric effects: Cooling by strength. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1603607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, A. Wederni, M. Ipatov, J. Gonzalez, V. Zhukova, A. Zhukov, Elucidation of the Strong Effect of the Annealing and the Magnetic Field on the Magnetic Properties of Ni2-Based Heusler Microwires. Crystals 2022, 12, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Li, Z. Wu, S. Yuan, X.B. Zhang Advances and challenges for flexible energy storage and conversion devices and systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2101–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Guillou, G. Porcari, H. Yibole, N. van Dijk, E. Bruck, Taming the first-order transition in giant magnetocaloric materials. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2671–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Salaheldeen, V. Zhukova, M. Ipatov, A. Zhukov, GdFe-based nanostructured thin films with large perpendicular magnetic anisotropy for spintronic applications. AIP Advances 2024, 14, 025308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, X. Zhao, J. Xu, Y. Fang, G. Chen, Y. Song, S. Li, J. Chen Giant magnetoelastic effect in soft systems for bioelectronics. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 1670–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Bonnot, R. Romero, L. Manosa, E. Vives, A. Planes, Elastocaloric effect associated with the martensitic transition in shape-memory alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 125901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Salaheldeen, V. Vega, A. Ibabe, M. Jaafar, A. Asenjo, A. Fernandez, V.M. Prida, Tailoring of Perpendicular Magnetic Anisotropy in Dy13Fe87 Thin Films with Hexagonal Antidot Lattice Nanostructure. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, V. Zhukova, J. Gonzalez, A. Zhukov, Anomalous magnetic behavior in MnFePSi glass-coated microwires. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. M. Hu, C.W. Nan Opportunities and challenges for magnetoelectric devices APL Mater. 2019, 7, 080905. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, T. Gottschall, K.P. Skokov, J.D. Moore, O. Gutfleisch, Giant magnetocaloric effect driven by structural transitions. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, A.M. Abu-Dief, L. Martínez-Goyeneche, S.O. Alzahrani, F. Alkhatib, P. Álvarez-Alonso, J.A. Blanco, Dependence of the Magnetization Process on the Thickness of Fe70Pd30 Nanostructured Thin Film. Materials. 2020, 13, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Y. Cong, L. Huang, V. Hardy, D. Bourgault, X.M. Sun, Z.H. Nie, M.G. Wang, Y. Ren, P. Entel, Y.D. Wang, Low-field-actuated giant magnetocaloric effect and excellent mechanical properties in a NiMn-based multiferroic alloy. Acta Mater. 2018, 146, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, A. Talaat, M. Ipatov, V. Zhukova, A. Zhukov, Preparation and Magneto-Structural Investigation of Nanocrystalline CoMn-Based Heusler Alloy Glass-Coated Microwires. Processes 2022, 10, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Narita, M. Fox A review on piezoelectric, magnetostrictive, and magnetoelectric materials and device technologies for energy harvesting applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1700743–10.1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. F. Wu, H.C. Xuan, S. Agarwal, Y.K. Xu, T. Zhang, L. Feng, H. Li, P.D. Han, C.L. Zhang, D.H. Wang, et al. Large magnetocaloric effect and magnetoresistance in Fe and Co co-doped Ni-Mn-Al Heusler alloys. Phys. Status Solidi A. 2018, 215, 1700843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Franco, J.S. Blázquez, J.J. Ipus, J.Y. Law, L.M. Moreno-Ramírez, A. Conde, Magnetocaloric effect: From materials research to refrigeration devices. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 93, 112–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, V. Zhukova, R. Lopez Anton, A. Zhukov, Dependence of Magnetic Properties of As-Prepared Nanocrystalline Ni2MnGa Glass-Coated Microwires on the Geometrical Aspect Ratio. Sensors 2024, 24, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Graf, S.S.P. Parkin, C. Felser, Heusler Compounds—A Material Class with Exceptional Properties. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2011, 47, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Otsuka, C.M. K. Otsuka, C.M. Wayman, Shape Memory Materials; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, (1999).

- M. Salaheldeen, V. Zhukova, M. Ipatov, A. Zhukov, Unveiling the Magnetic and Structural Properties of (X2YZ; X = Co and Ni, Y = Fe and Mn, and Z = Si) Full-Heusler Alloy Microwires with Fixed Geometrical Parameters. Crystals 2023, 13, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. G. Pushin, Alloys with a Termomechanical Memory: Structure, properties and application. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2000, 90 (Suppl. S1), S68–S95. [Google Scholar]

- R. Cesare, J. Pons, R. Santamarta, C. Segui, V.A. Chernenko, Ferromagnetic Shape Memory Alloys: An Overview. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2004, 49, 779–789. [Google Scholar]

- M. Salaheldeen, A. Wederni, M. Ipatov, V. Zhukova, A. Zhukov, Carbon-Doped Co2MnSi Heusler Alloy Microwires with Improved Thermal Characteristics of Magnetization for Multifunctional Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. A. Gschneidner, V.K. Pecharsky, Thirty years of near room temperature magnetic cooling: where we are today and future prospects. Int. J. Refrig. 2008, 31, 945–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Smith, C.R.H. Bahl, R. Bjørk, K. Engelbrecht, K.K. Nielsen, N. Pryds, Materials challenges for high performance magnetocaloric refrigeration devices, Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 1288–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. D. Kuz’Min, Factors limiting the operation frequency of magnetic refrigerators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 251916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Vuarnoz, T. Kawanami, Numerical analysis of a reciprocating active magnetic regenerator made of gadolinium wires. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 37, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Zhukov, M. Ipatov, J.J. del Val, V. Zhukova, V.A. Chernenko, Magnetic and structural properties of glass-coated Heusler-type microwires exhibiting martensitic transformation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. F. Miao, S.Y. Hu, F. Xu, E. Brück, Overview of magnetoelastic coupling in (Mn, Fe)2(P,Si)-type magnetocaloric materials. Rare Met. 2018, 37, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Gottschall, K.P. Skokov, M. Fries, A. Taubel, I. Radulov, F. Scheibel, D. Benke, S. Riegg, O. Gutfleisch, Making a cool choice: the materials library of magnetic refrigeration. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Suye, H. Yibole, F. Guillou, Influence of the particle size on a MnFe(P,Si,B) compound with giant magnetocaloric effect. AIP Advances 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. H. Dung, L. Zhang, Z.Q. Ou, E. Brück, From first-order magneto-elastic to magneto-structural transition in (Mn,Fe) 1.95 P 0.50 Si 0.50 compounds, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 092511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Hudl, P. Nordblad, T. Björkman, O. Eriksson, L. Häggström, M. Sahlberg, Y. Andersson, E.K. Delczeg-Czirjak, L. Vitos, Order-disorder induced magnetic structures of FeMnP0.75 Si 0.25. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 134420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. F. Miao, L. Caron, P. Roy, N. H. Dung, L. Zhang, W. A. Kockelmann, R. A. de Groot, N. H. van Dijk, and E. Bruck, Tuning the phase transition in transition-metal-based magnetocaloric compounds. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 174429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou. ZQ, L. Zhang, N.H. Dung, L. Caron, E. Bru¨ ck. Structure, magnetism and magnetocalorics of Fe-rich (Mn,Fe)1.95P1- xSix melt-spun ribbons. J Alloys Compd. 2017, 710, 446e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. H. Dung, Z. Q. Ou, L. Caron, L. Zhang, D. T. Cam Thanh, G. A. de Wijs, R. A. de Groot, K. H. J. Buschow, E. Bruck, Mixed magnetism for refrigeration and energy conversion. Adv. Energy Mater. 2011, 1, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. J. Neish, M. P Oxley, J. Guo, B. C. Sales, L. J. Allen, and M. F. Chisholm, Local Observation of the Site Occupancy of Mn in a MnFePSi Compound. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X. F. Miao, L. Caron, Z. Gercsi, A. Daoud-Aladine, N. H. van Dijk, and E. Bruck, Thermal-history dependent magnetoelastic transition in (Mn,Fe)2(P,Si). Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 042403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Zhang, S. Smits, A. Kiecana, I. Batashev, Q. Shen, N. van Dijk, E. Brück, Impact of W doping on Fe-rich (Mn,Fe)2(P,Si) based giant magnetocaloric materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 933, 167802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Zheng, H. Z. Zheng, H. Wang, C. Li, X. Chen, D. Zeng, S. Yuan, Enhancement of magnetic properties and magnetocaloric effects for Mn0.975Fe0.975P0.5Si0.5 alloys by optimizing quenching temperature. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 2200160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. He, V. Svitlyk, Y. Mozharivskyj, Synthetic approach for (Mn,Fe)2(Si,P) magnetocaloric materials: purity, structural, magnetic, and magnetocaloric properties. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 2827–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Lai, B. Huang, X. You, M. Maschek, G. Zhou, N. van Dijk, E. Brück, Giant magnetocaloric effect for (Mn,Fe,V)2(P,Si) alloys with low hysteresis. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Dev. 2024, 9, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. F. Miao, L. Caron, P.C.M. Gubbens, A. Yaouanc, P. Dalmas De R´eotier, H. Luetkens, A. Amato, N.H. van Dijk, E. Brück, Spin correlations in (Mn,Fe)2(P,Si) magnetocaloric compounds above curie temperature. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. dev. 2016, 1, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, V. Zhukova, J. J. Rosero-Romo, M. Ipatov, and A. Zhukov. Preparation and magnetic properties of MnFePSi-based glass-coated microwires. AIP Advances 2024, 1, 015350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.S.J. Rodin Ihnfeldt, R. E.S.J. Rodin Ihnfeldt, R. Chen, T. Feng, and S. Adapa. Low-cost magnetocaloric materials discovery. 2020 DOE Annual Merit Review 2020, 1–22.

- J. Lai, X. You, I. Dugulan, B. Huang, J. Liu, M. Maschek, et al-, “Tuning the magneto-elastic transition of (Mn,Fe,V)2(P,Si) alloys to low magnetic field applications. J Alloys Compd. 2020, 821, 153451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Lai, X. Tang, H. Sepehri-Amin, and K. Hono, Tuning transition temperature of magnetocaloric Mn 1.8 Fe 0.2 (P 0.59 Si 0.41) x alloys for cryogenic magnetic refrigera-tion. Scr. Mater. 2020, 183, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- M. Fries, L. Pfeuffer, E. Bruder, T. Gottschall, S. Ener, L.V.B. Diop, et al. “Microstructural and magnetic properties of Mn-Fe-P-Si (Fe2P-type) magnetocaloric compounds. Acta Mater. 2017, 132, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Tu, J. Yan, Y. Xie, J. Li, S. Feng, M. Xia, J. Li, and A.P. Leung, “Accelerated design for magnetocaloric performance in Mn-Fe-P-Si compounds using machine learning. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 96, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Guillou, G. Porcari, H. Yibole, N. H. van Dijk, and E. Bruck, “Taming the first-order transition in giant magnetocaloric, materials. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. H. Dung, L. Zhang, Z. Q. Ou, L. Zhao, L. van Eijck, A. M. Mulders, M. Avdeev, E. Suard, N. H. van Dijk, and E. Bruck, “High/low-moment phase transition in hexagonal Mn-Fe-P-Si compounds. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 045134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Yu, Z.R. Zhu, J.W. Lai, Z.G. Zheng, D.C. Zeng, and J.L. Zhang, “Enhance magnetocaloric effects in Mn1.15Fe0.85P0.52Si0.45B0.03 alloy achieved by copper mould casting and annealing treatments. J Alloys Compd. 2015, 649, 1043e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Tu, J. Li, R. Zhang, Q. Hu, and J. Li, “Microstructure evolution, solidification characteristic and magnetocaloric properties of MnFeP0.5Si0.5 particles by droplet melting. Intermetallic 2021, 131, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Yue, M.F. Xu, H.G. Zhang, D.T. Zhang, D.M. Liu, and Z. Altounian, “Structural and magnetocaloric properties of MnFeP1-xSix compounds prepared by spark plasma sintering. IEEE Trans Magn. 2015, 51, 11e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Luo, J.Y. Law, H. Shen, L.M. Moreno-Ramírez, V. Franco, S. Guo, N.T.M. Duc, J. Sun, and M-H. Phan, “Enhanced Magnetocaloric Properties of Annealed Melt-Extracted Mn1.3Fe0.6P0.5Si0.5 Microwires. Metals 2022, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, M. Ipatov, V. Zhukova, A. García-Gomez, J. Gonzalez, A. Zhukov; Preparation and magnetic properties of Co2-based Heusler alloy glass-coated microwires with high Curie temperature. AIP Advances 2023, 13, 025325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Zhukov, P. Corte-Leon, L. Gonzalez-Legarreta, M. Ipatov, J.M. Blanco, A. Gonzalez, V. Zhukova, Advanced functional magnetic microwires for technological applications. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 253003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Chiriac, T.A. Ovari, Amorphous glass-covered magnetic wires: preparation, properties, applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 1996, 40, 333–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, A. Wederni, M. Ipatov, V. Zhukova, A. Zhukov. Preparation and Magneto-Structural Investigation of High-Ordered (L21 Structure) Co2MnGe Microwires. Processes 2023, 11, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, A. Garcia-Gomez, M. Ipatov, P. Corte-Leon, V. Zhukova, J.M. Blanco, and A. Zhukov, “Fabrication and Magneto-Structural Properties of Co2-Based Heusler Alloy Glass-Coated Microwires with High Curie Temperature. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Zhukova, A.F. Cobeño, A. Zhukov, J.M. Blanco, V. Larin and J. Gonzalez, “Coercivity of glass-coated Fe73.4-xCu1Nb3.1Si13.4+xB9.1 (0≤x≤1.6) microwires, Nanostructured. Materials 1999, 11, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, A. Wederni, M. Ipatov, V. Zhukova, R. Lopez Anton, and A. Zhukov, “Enhancing the Squareness and Bi-Phase Magnetic Switching of Co2FeSi Microwires for Sensing Application. Sensors 2023, 23, 5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, V. Zhukova, J. Rosero, D. Salazar, M. Ipatov, and A. Zhukov, “Comparison of the magnetic and structural properties of MnFePSi microwires and MnFePSi bulk alloy. Materials 2024, 17, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Vázquez, Soft magnetic wires. Physica B 2001, 299, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Salaheldeen, A. Garcia-Gomez, P. Corte-Leon, A. Gonzalez, M. Ipatov, V. Zhukova, R. Lopez Anton, and A. Zhukov, Manipulation of magnetic and structure properties of Ni2FeSi glass-coated microwires by annealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 942, 169026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Lóopez Antóon, J.P. R. Lóopez Antóon, J.P. Andres, J.A. Gonzalez, A. García-Gomez, V. Zhukova, A. Chizhik, M. Salaheldeen, A. Zhukov, Tuning of magnetic properties and Giant Magnetoimpedance effect in multilayered microwires. J. Sci.: Advanced Materials and Devices 2024, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Herzer, Modern soft magnets: Amorphous and nanocrystalline materials. Acta Materialia 2013, 61, 718–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Chemical composition | Lattice constant (a) nm | Dg (nm) |

| As-prepared | Mn₄₀Fe₃₀P₁₅Si₁₅ | 0.58 | 36 |

| 973 K (1h) | Mn₄₀Fe₃₀P₁₅Si₁₅ | 0.54 | 136 |

| 1073 K (1h) | Mn₄₀Fe₃₀P₁₅Si₁₅ | 0.60 | 141 |

| 1123 K (1h) | Mn₄₀Fe₃₀P₁₅Si₁₅ | 0.61 | 148 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).