Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

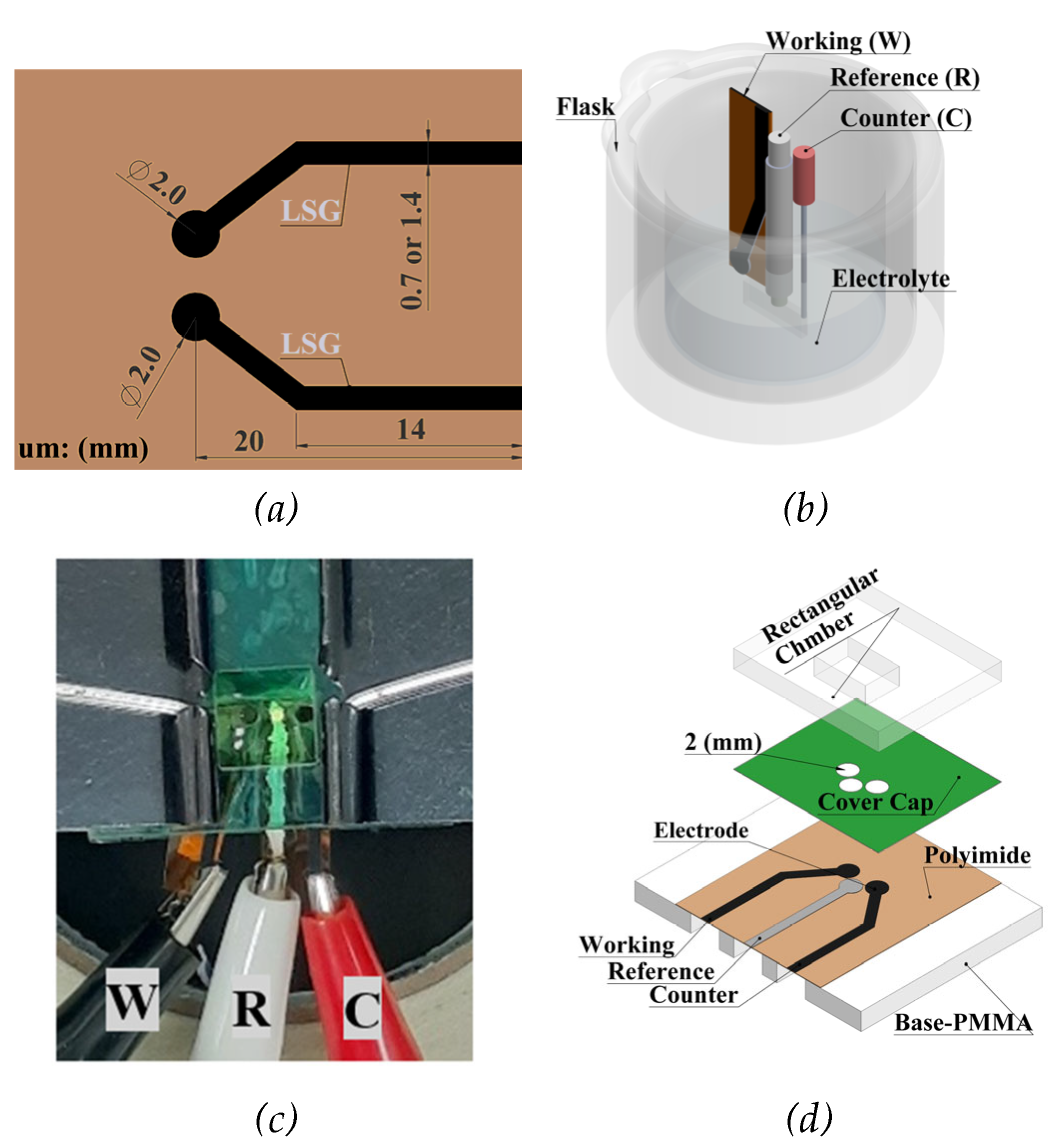

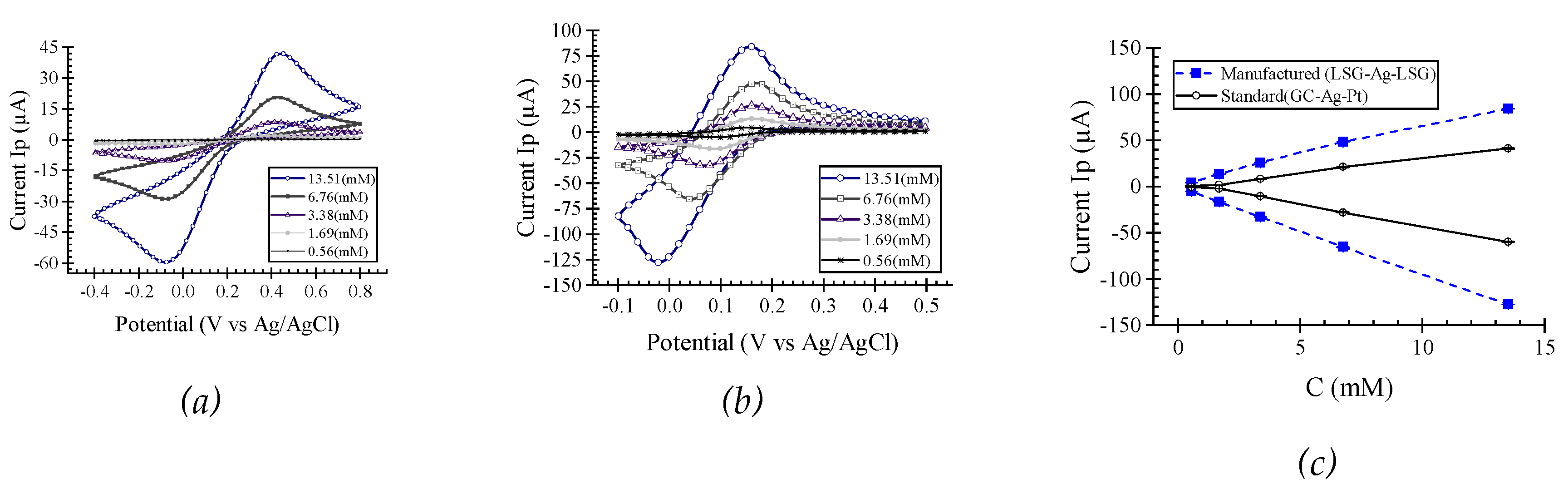

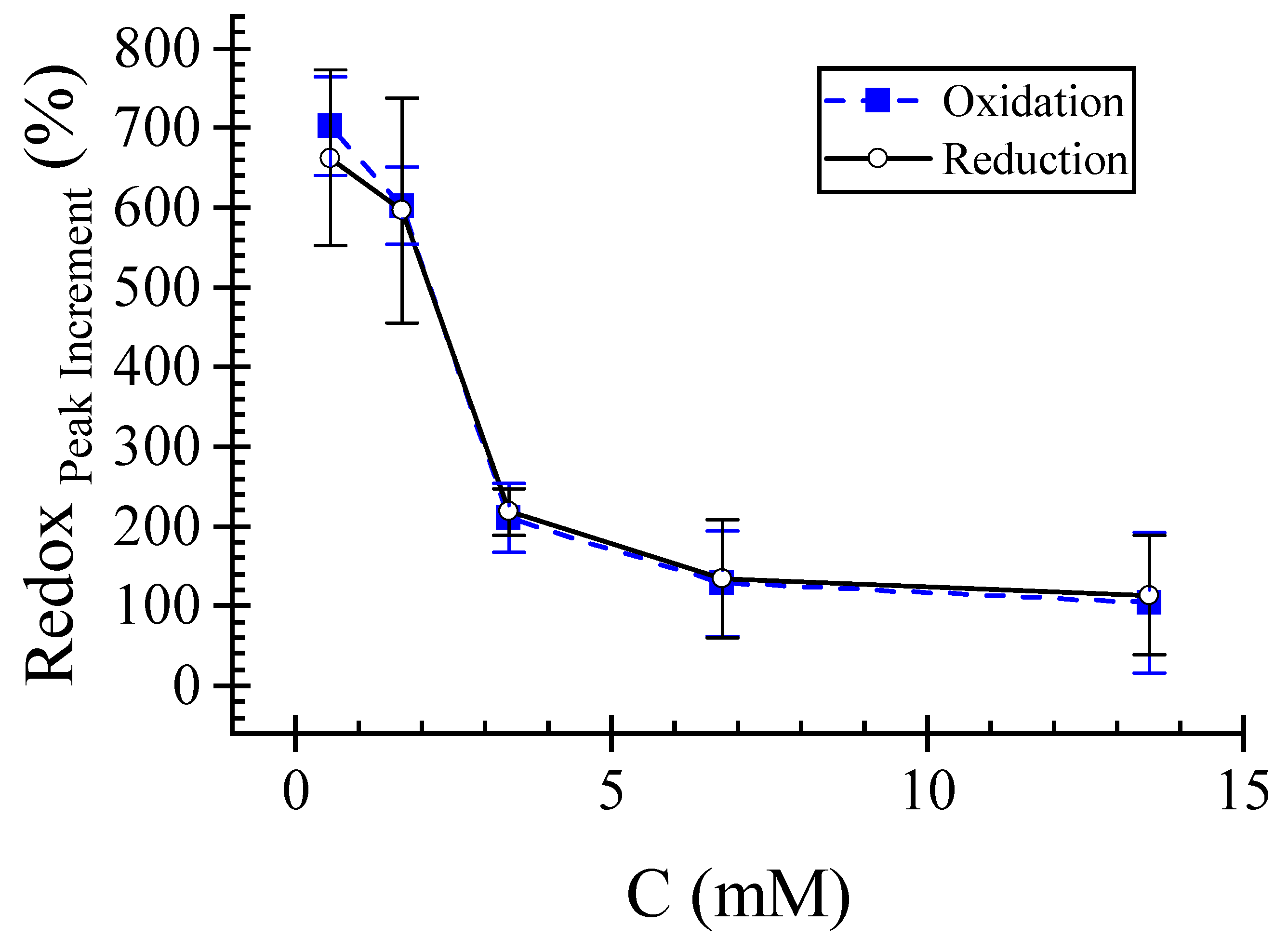

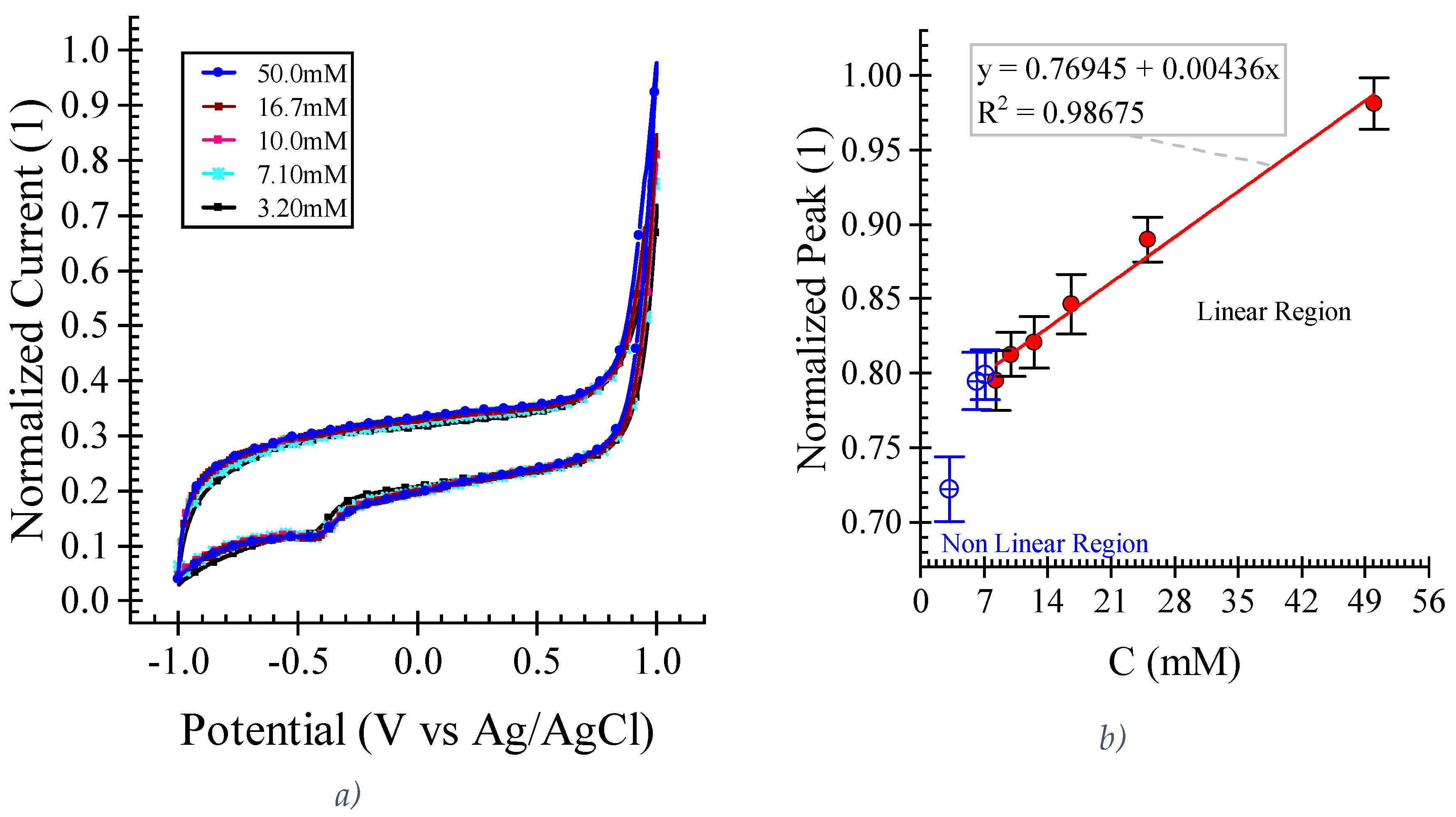

This study investigates the fabrication of laser-scribed graphene (LSG) electrodes on polyimide substrates using a CO2 laser cutter for label-free L-histidine detection in artificial sweat. Two-level full factorial and central composite designs were employed to optimize critical manufacturing parameters, including laser speed, power, and electrode width. Electrochemical characterization using cyclic voltammetry with K3Fe[CN]6 demonstrated superior LSG electrode performance compared to standard glassy carbon electrodes, exhibiting a 702 ± 62% higher oxidation current peak at 0.56 (mM) K3Fe[CN]6 in 0.1 M KCl. We successfully demonstrated the label-free electrochemical detection of L-histidine in artificial sweat using these LSG electrodes. The results show a linear relationship (R2 =0.987) between current peak and L-histidine concentration within the 8.3 (mM) to 50 (mM) range, demonstrating high sensitivity towards L-histidine. These findings highlight the potential of this optimized LSG electrode fabrication approach for developing high-performance, user-friendly, and disposable wearable biosensors for real-time, and non-invasive health monitoring applications in sweat analysis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

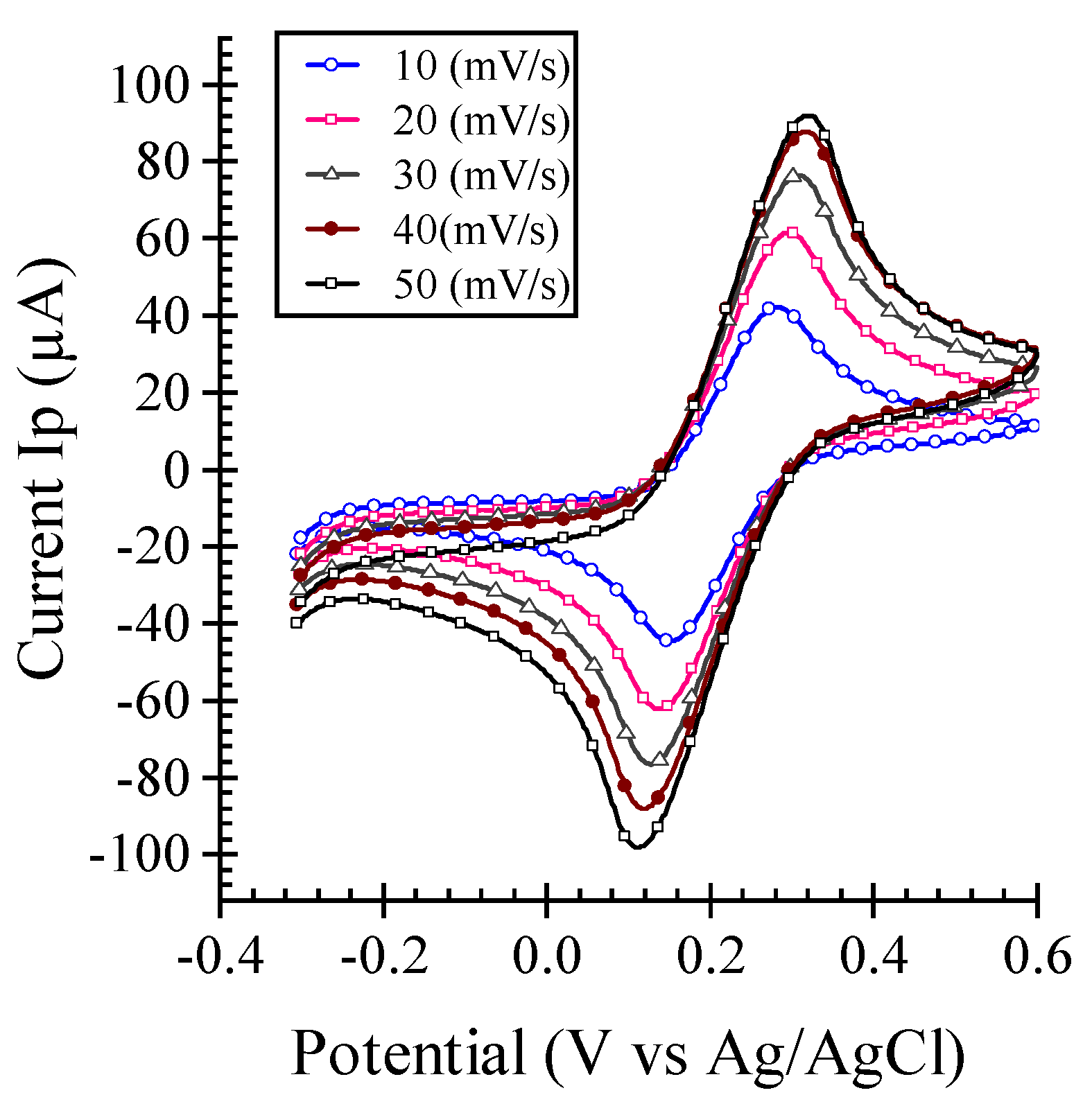

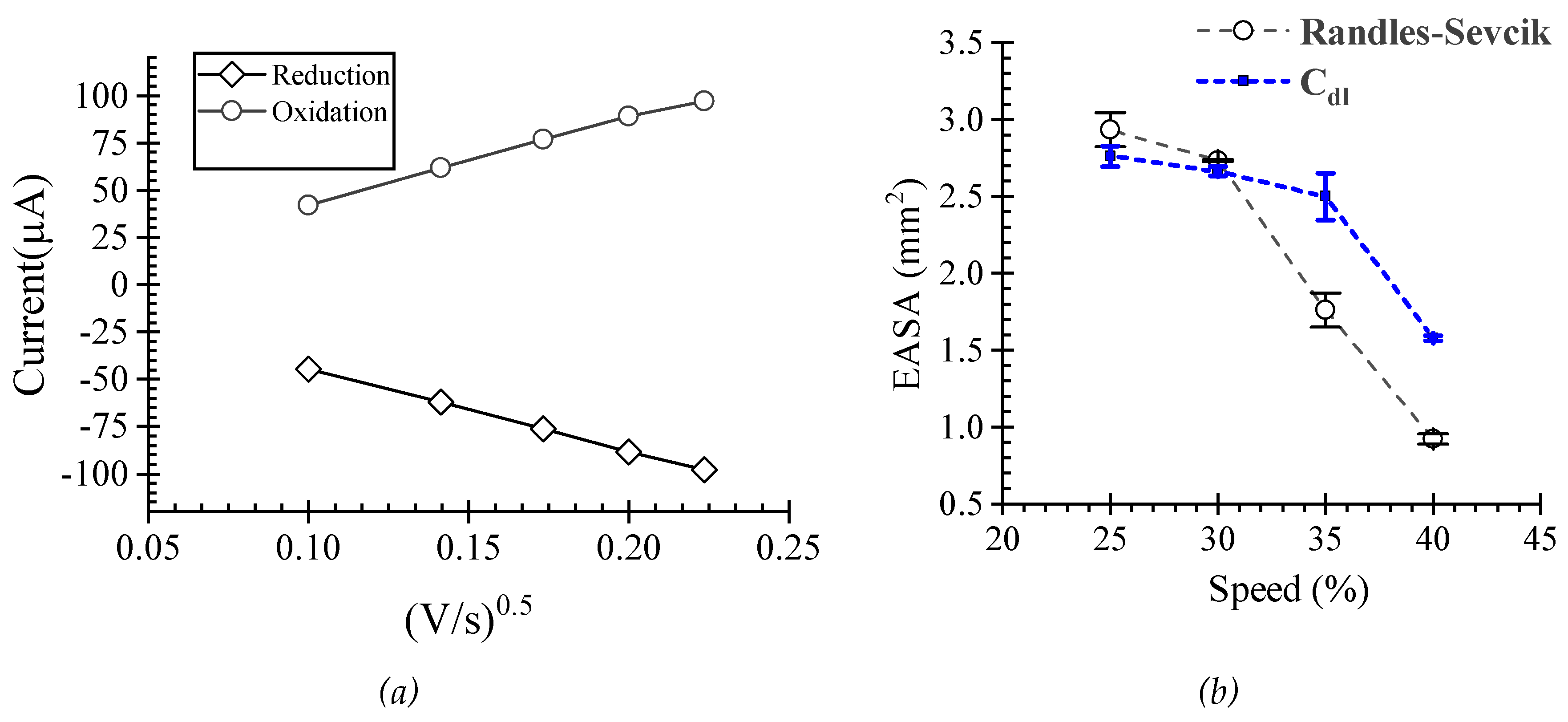

Electrochemical Characterization

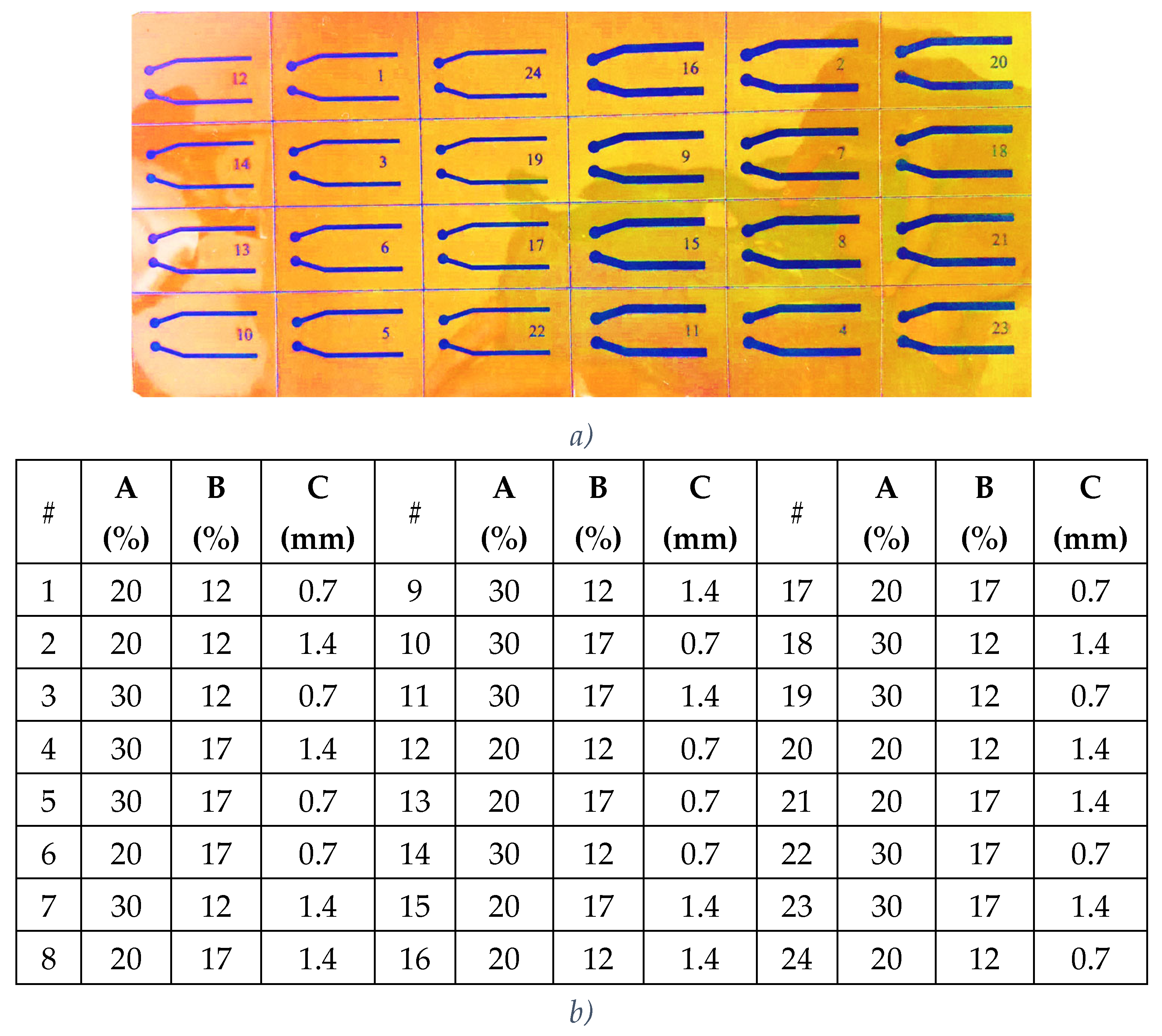

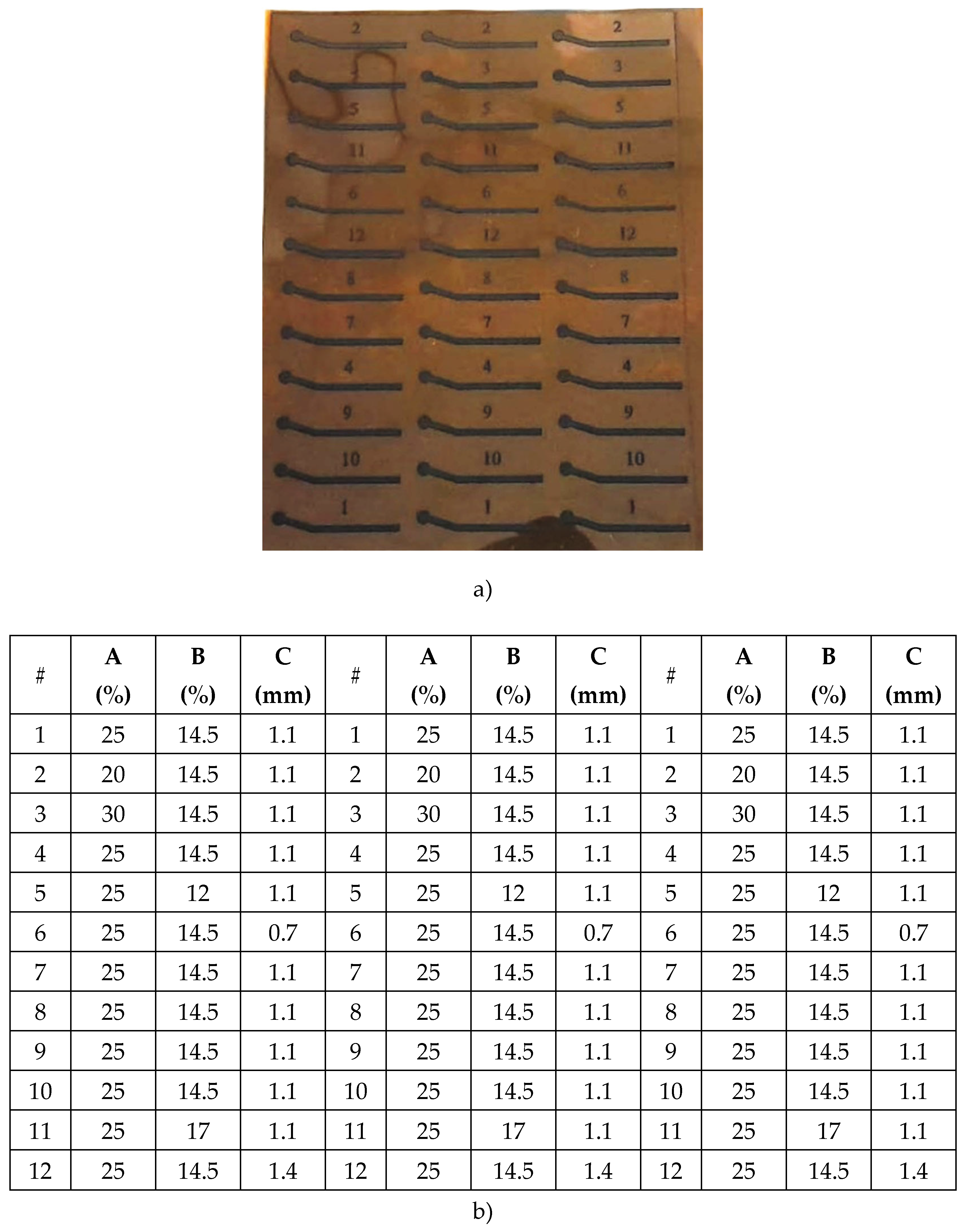

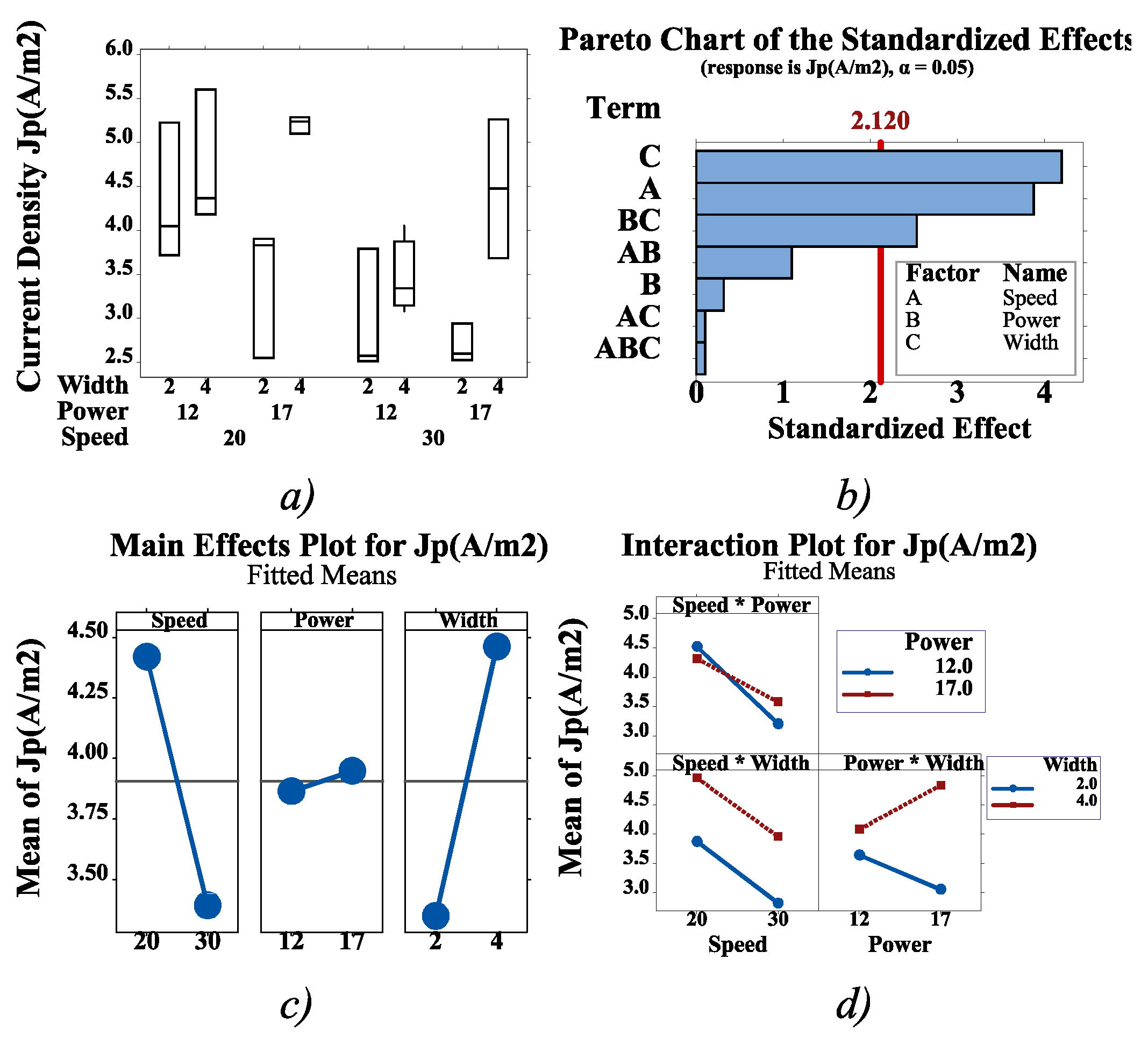

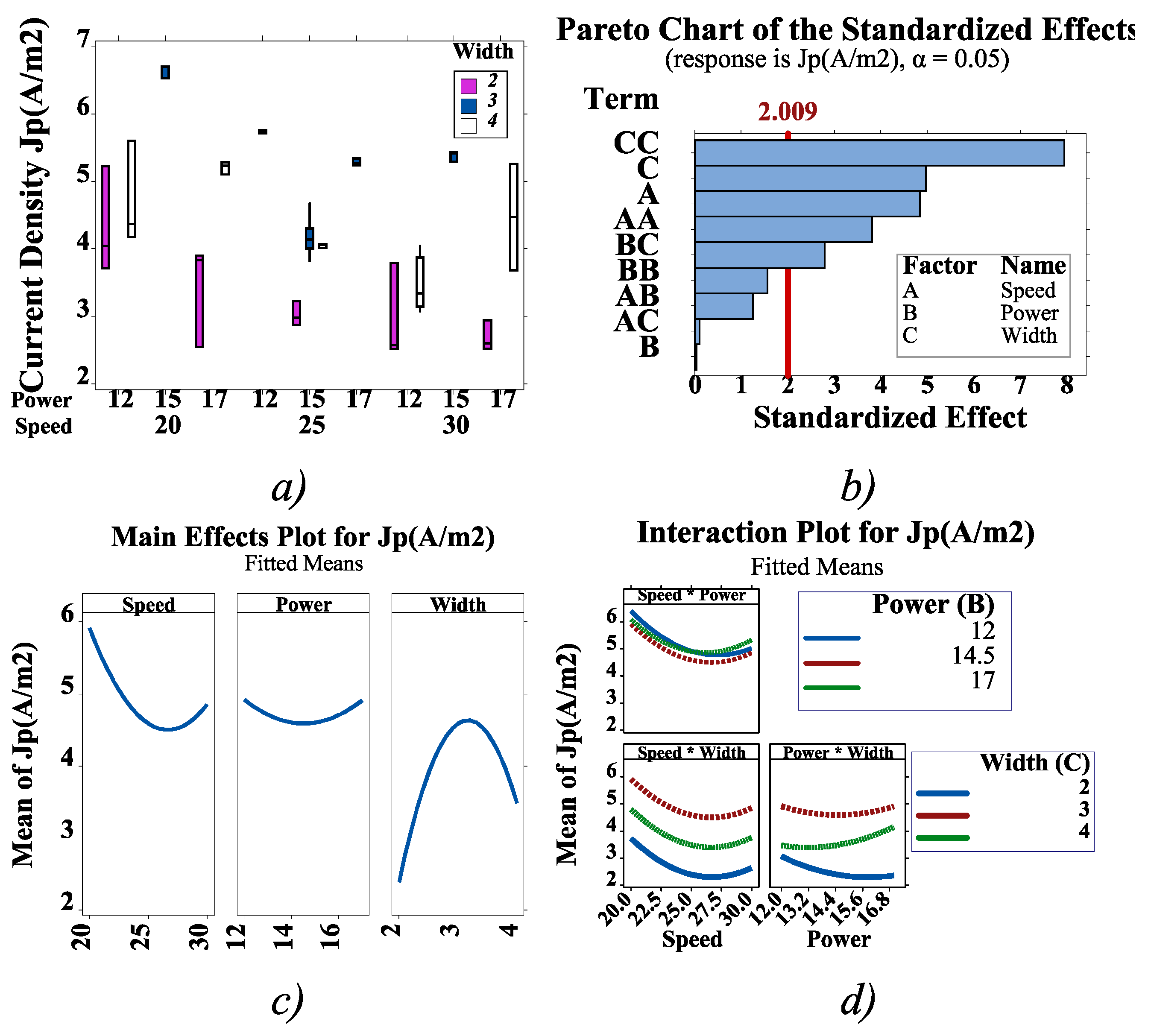

Design of Experiments Using FFD and CCD

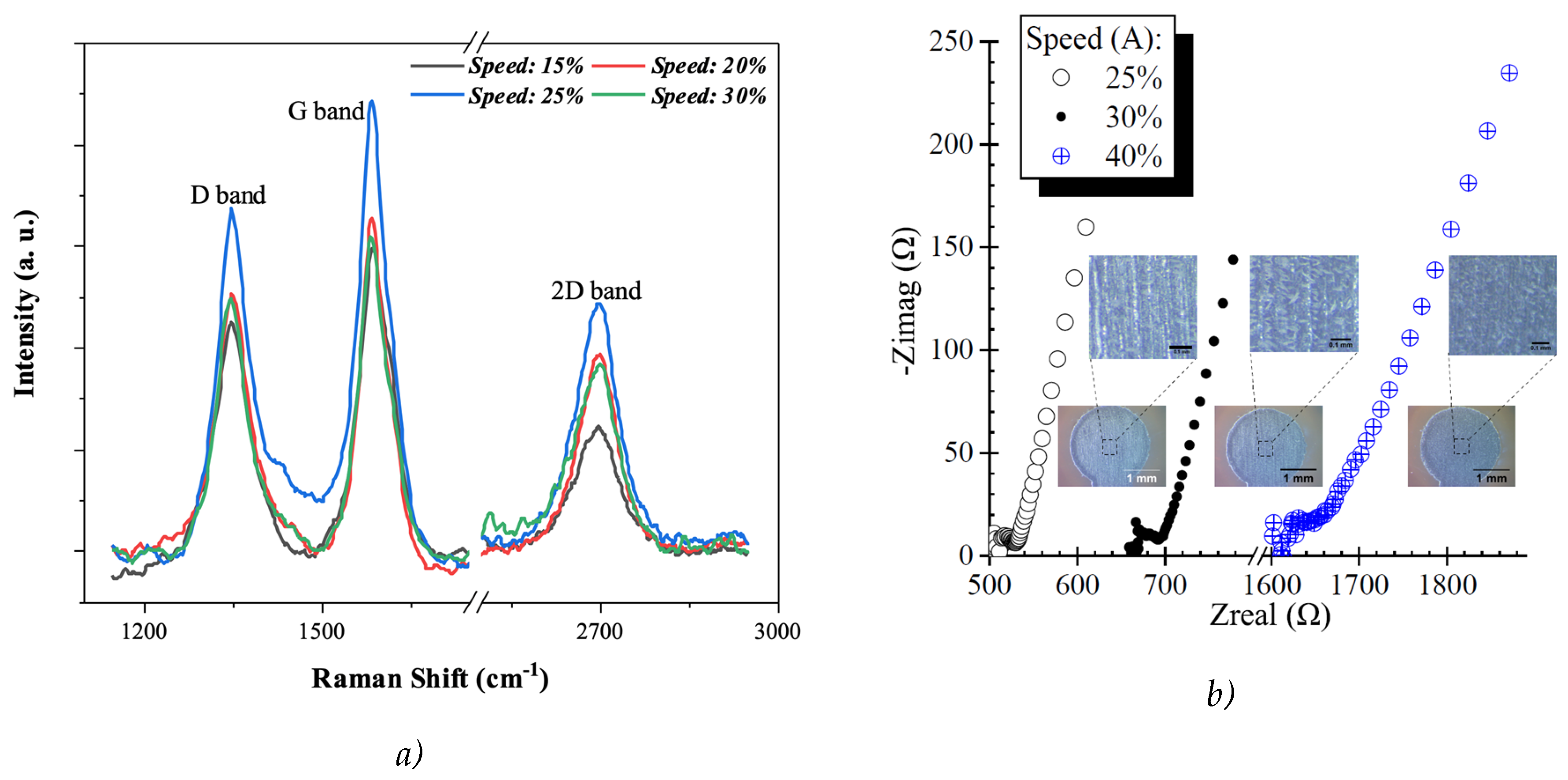

Raman Measurements

3. Results ad Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geim, A.K. Graphene: Status and Prospects. Science 2009, 324, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwierz, F. Graphene Transistors: Status, Prospects, and Problems. Proc. IEEE 2013, 101, 1567–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Dubonos, S.V.; Firsov, A.A. Two-Dimensional Gas of Massless Dirac Fermions in Graphene. Nature 2005, 438, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, H.; Clauss, A.; Fischer, G.; Hofmann, U. Surface Properties of Extremely Thin Graphite Lamellae; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1962; Volume 1, pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Deligeorgis, G.; Konstantinidis, G.; Dragoman, M.; Plana, R. Fabrication of Graphene Devices, Issues and Prospects. In Proceedings of the CAS 2010 Proceedings (International Semiconductor Conference); IEEE: Sinaia, October, 2010; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, C.; Song, Z.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Ogbazghi, A.Y.; Feng, R.; Dai, Z.; Marchenkov, A.N.; Conrad, E.H.; First, P.N.; et al. Ultrathin Epitaxial Graphite: 2D Electron Gas Properties and a Route toward Graphene-Based Nanoelectronics. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 19912–19916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cai, W.; An, J.; Kim, S.; Nah, J.; Yang, D.; Piner, R.; Velamakanni, A.; Jung, I.; Tutuc, E.; et al. Large-Area Synthesis of High-Quality and Uniform Graphene Films on Copper Foils. Science 2009, 324, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, F.; Hao, C.; Xiang, J.; Wang, L.; Hou, H.; Su, Z.; Hu, W.; Liu, Z. Enhanced Laser Scribed Flexible Graphene-Based Micro-Supercapacitor Performance with Reduction of Carbon Nanotubes Diameter. Carbon 2014, 75, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, J.-R. Laser Scribed Graphene Cathode for Next Generation of High Performance Hybrid Supercapacitors. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, Y.; Bo, X.; Min, J.; Pak, O.S.; Zhu, L.; Wang, M.; Tu, J.; Kogan, A.; Zhang, H.; et al. A Laser-Engraved Wearable Sensor for Sensitive Detection of Uric Acid and Tyrosine in Sweat. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, Z.; Chen, X. Laser-Scribed Graphene for Sensors: Preparation, Modification, Applications, and Future Prospects. gxjzz 2023, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameku, W.A.; Negahdary, M.; Lima, I.S.; Santos, B.G.; Oliveira, T.G.; Paixão, T.R.L.C.; Angnes, L. Laser-Scribed Graphene-Based Electrochemical Sensors: A Review. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.-H.; Thaxton, A.; Jeong, I.C.; Kim, K.; Sosnay, P.R.; Cutting, G.R.; Searson, P.C. Sweat Test for Cystic Fibrosis: Wearable Sweat Sensor vs. Standard Laboratory Test. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2018, 17, e35–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshin, O.; Kireev, D.; Hlukhova, H.; Idachaba, F.; Akinwande, D.; Atayero, A. Graphene-Based Biosensor for Early Detection of Iron Deficiency. Sensors 2020, 20, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.L.; Venton, B.J.; Heien, M.L.A.V.; Wightman, R.M. Detecting Subsecond Dopamine Release with Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry in Vivo. Clinical Chemistry 2003, 49, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husmann, S.; Nossol, E.; Zarbin, A.J.G. Carbon Nanotube/Prussian Blue Paste Electrodes: Characterization and Study of Key Parameters for Application as Sensors for Determination of Low Concentration of Hydrogen Peroxide. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2014, 192, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Song, C.; Hong, Y.S.; Kim, M.; Cho, H.R.; Kang, T.; Shin, K.; Choi, S.H.; Hyeon, T.; Kim, D.-H. Wearable/Disposable Sweat-Based Glucose Monitoring Device with Multistage Transdermal Drug Delivery Module. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1601314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.-J. Ultrasensitive Label-Free Detection of PNA–DNA Hybridization by Reduced Graphene Oxide Field-Effect Transistor Biosensor. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2632–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenzl, C.; Nayak, P.; Hirsch, T.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Alshareef, H.N.; Baeumner, A.J. Laser-Scribed Graphene Electrodes for Aptamer-Based Biosensing. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.S.; Tan, M.T.T.; Loh, H.-S.; Khiew, P.S.; Chiu, W.S. Facile Hydrothermal Growth Graphene/ZnO Nanocomposite for Development of Enhanced Biosensor. Analytica Chimica Acta 2016, 903, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Lukas, H.; Tu, J.; Min, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C.; Rossiter, H.B.; Gao, W. SARS-CoV-2 RapidPlex: A Graphene-Based Multiplexed Telemedicine Platform for Rapid and Low-Cost COVID-19 Diagnosis and Monitoring. Matter 2020, 3, 1981–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K.; Dale, C.; Hedley, J.; Kowal, M.D.; Kaner, R.B.; Keegan, N. Laser-Scribed Graphene Presents an Opportunity to Print a New Generation of Disposable Electrochemical Sensors. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 13613–13622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, P.; Kurra, N.; Xia, C.; Alshareef, H.N. Highly Efficient Laser Scribed Graphene Electrodes for On-Chip Electrochemical Sensing Applications. Adv Elect Materials 2016, 2, 1600185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, M.J.Y.; Vasudevan, M.; Perumal, V.; Liu, W.W.; Mohamed, N.M. Synthesis of Laser Scribed Graphene Electrode with Optimized Power for Biosensing. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Regional Symposium on Micro and Nanoelectronics (RSM); IEEE: Genting Highland, Pahang, Malaysia, August, 2019; pp. 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- De La Roche, J.; López-Cifuentes, I.; Jaramillo-Botero, A. Influence of Lasing Parameters on the Morphology and Electrical Resistance of Polyimide-Based Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG). Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, J.; Cheng, H. Effects of Laser Processing Parameters on Properties of Laser-Induced Graphene by Irradiating CO2 Laser on Polyimide. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Burke, M.; Iacopino, D.; Quinn, A.J. Design of Experiments and Optimization of Laser-Induced Graphene. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 16736–16743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design and Analysis of Experiments; Montgomery, D. C., Ed.; Eighth edition.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-14692-7. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, J. Design of Experiments for Engineers and Scientists; Elsevier, 2023; ISBN 0-443-15174-1.

- Senf, B.; Yeo, W.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Recent Advances in Portable Biosensors for Biomarker Detection in Body Fluids. Biosensors 2020, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachornsakkul, K.; Dungchai, W. Rapid Distance-Based Cardiac Troponin Quantification Using Paper Analytical Devices for the Screening and the Follow-Up of Acute Myocardial Infarction, Using a Single Drop of Human Whole Blood. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Rivera, R.; García-Rodríguez, W.; López, L.; Cunci, L.; Resto, P.J.; Domenech, M. PCL/PEO Polymer Membrane Prevents Biofouling in Wearable Detection Sensors. Membranes 2023, 13, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Histidine in Health and Disease: Metabolism, Physiological Importance, and Use as a Supplement. Nutrients 2020, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.P.; Brown, S.B.; Griffiths, C.; Weller, R.; Gibbs, N.K. Feeding Filaggrin: Effects of L-Histidine Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis. CCID 2017, Volume 10, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, R.H.; Sparkes, D.L.; Dascombe, B.J.; Macdonald, M.M.; Evans, C.A.; Stevens, C.J.; Crompton, M.J.; Gottfries, J.; Franks, J.; Murphy, G.; et al. Sweat Facilitated Amino Acid Losses in Male Athletes during Exercise at 32-34°C. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hier, S.W.; Cornbleet, T.; Bergeim, O. THE AMINO ACIDS OF HUMAN SWEAT. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1946, 166, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callewaert, C.; Buysschaert, B.; Vossen, E.; Fievez, V.; Van De Wiele, T.; Boon, N. Artificial Sweat Composition to Grow and Sustain a Mixed Human Axillary Microbiome. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2014, 103, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, W.; Saavedra-Ruiz, A.; Resto-Irizarry, P.J. Label-Free Classification of L-Histidine Vs Artificial Human Sweat Using Laser Scribed Electrodes and a Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; He, Z.; Song, Y.; Fu, X.; Rommel, M.; Luo, X.; Hartmaier, A.; Zhang, J.; Fang, F. Topic Review: Application of Raman Spectroscopy Characterization in Micro/Nano-Machining. Micromachines 2018, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, T.; Shen, Z. Raman Spectroscopy and Imaging of Graphene. Nano Res. 2008, 1, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.P.; Nolte, D.D. Strong Anomalous Optical Dispersion of Graphene: Complex Refractive Index Measured by Picometrology. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 22105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okafor, P.A.; Huxel, B.; Iroh, J.O. Electrochemical Behavior of Multifunctional Graphene–Polyimide Nanocomposite Film in Two Different Electrolyte Solutions. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2015, 132, app.42673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F.J.; Salinas-Castillo, A.; Rivadeneyra, A.; Albrecht, A.; Godoy, A.; Morales, D.P.; Rodriguez, N. In-Depth Study of Laser Diode Ablation of Kapton Polyimide for Flexible Conductive Substrates. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhafez, M.; Tomaraei, G.N.; Bedewy, M. Fluence-Dependent Morphological Transitions in Laser-Induced Graphene Electrodes on Polyimide Substrates for Flexible Devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 2973–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).