Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

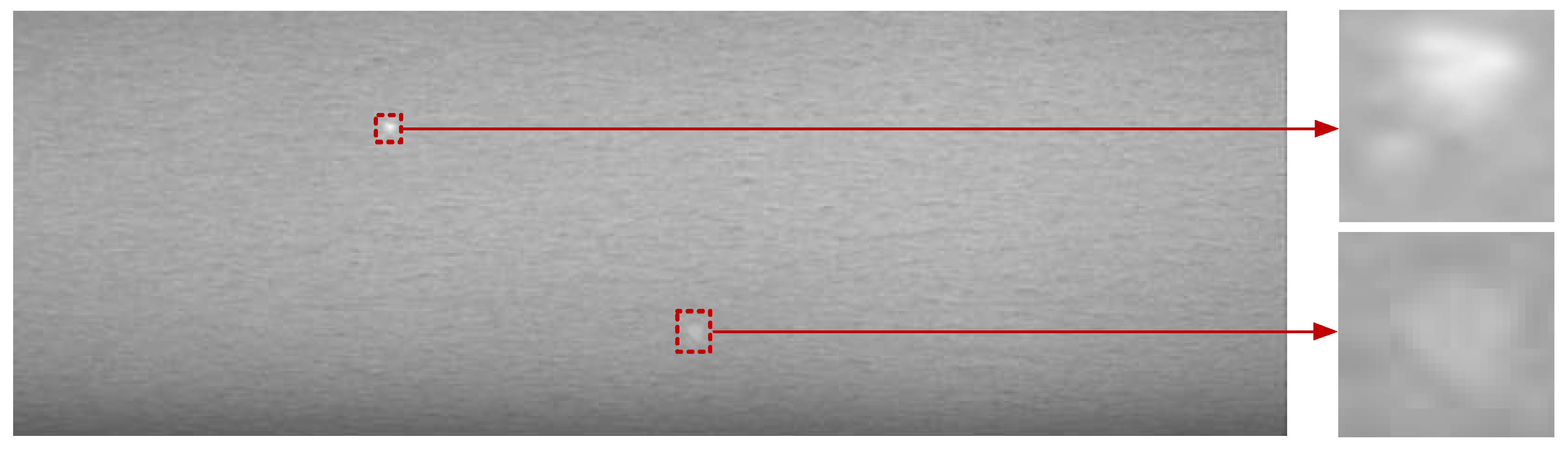

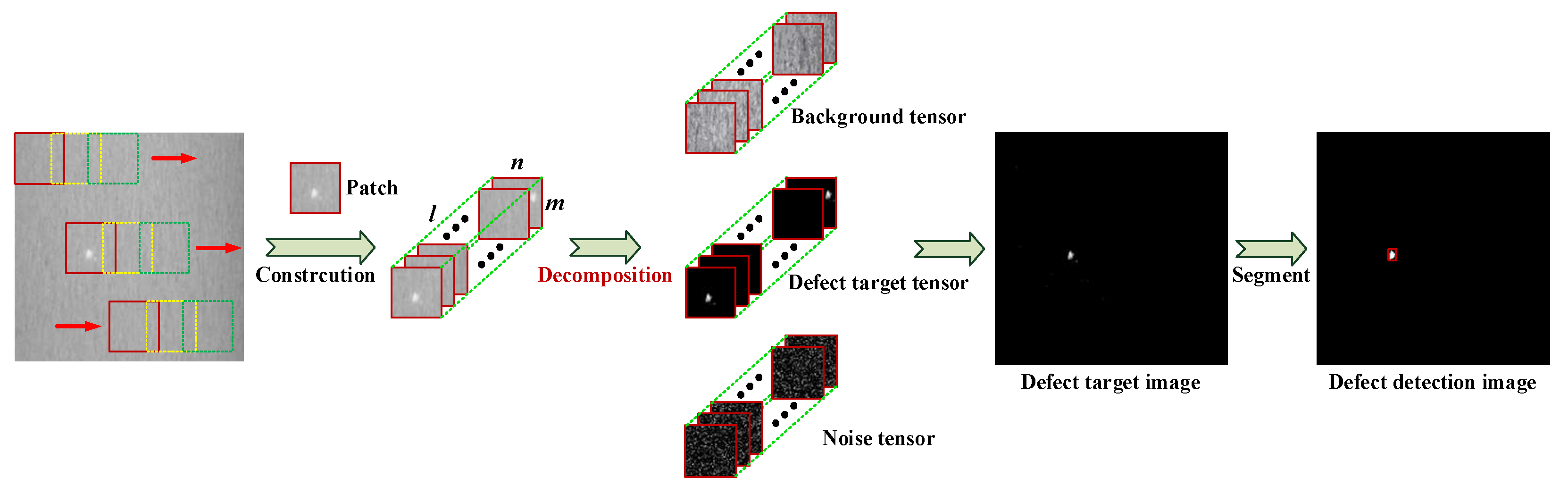

Accurate and efficient white-spot defects detection for the surface of galvanized strip steel is one of the most important guarantees for the quality of steel production. It’s a fundamental but “hard” small target detection problem due to its small pixel occupation in low-contrast images. By fully exploiting the low-rank and sparse prior information of surface defect image, a Schatten-p norm-based low-rank tensor decomposition (SLRTD) method is proposed to decomposes the defect image into low-rank background, sparse defect, and random noise. Firstly, the original defect images are transformed into a new patch-based tensor mode through data reconstruction for mining valuable information of defect image. Then, considering the over-shrinkage problem in low-rank component estimation caused by vanilla nuclear norm and weighted nuclear norm, a nonlinear reweighting strategy based on Schatten p-norm is incorporated to improve the decomposition performance. Finally, a solution framework is proposed via a well-designed alternating direction method of multipliers to obtain the white-spot defect target image by a simple segmenting algorithm. The white-spot defect dataset from real-world galvanized strip steel production line is constructed, and the experimental results demonstrate that the proposed SLRTD method outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods qualitatively and quantitatively.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose a SLRTD method by digging out inter-patch correlation-ships of surface defect images of galvanized strip steel. The separated defect foreground target information with sparse outliers is embedded in the background of low-rank representation.

- To achieve an accurate estimation of non-defect background rank, we incorporate weighted Schatten p-norm regularization for the background component, allowing for better noise removal while preserving edges, ultimately leading to improved detection results. Concurrently, a nonlinear reweighting strategy and tensor singular value decomposition (t-SVD) are adopted to help the model more delicately balance the low-rank and sparse components throughout the iterative process, which elevates the separation accuracy between the defect target and non-defect background.

- On the basis of the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM), an effective approach is introduced to solve the sparse and low-rank component decomposition problem. Experiments validate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed SLRTD method.

2. Related Works

2.1. Filtering-Based Methods

2.2. Data-Driven-Based Methods

2.3. Tensor Decomposition-Based Methods

3. Methodology

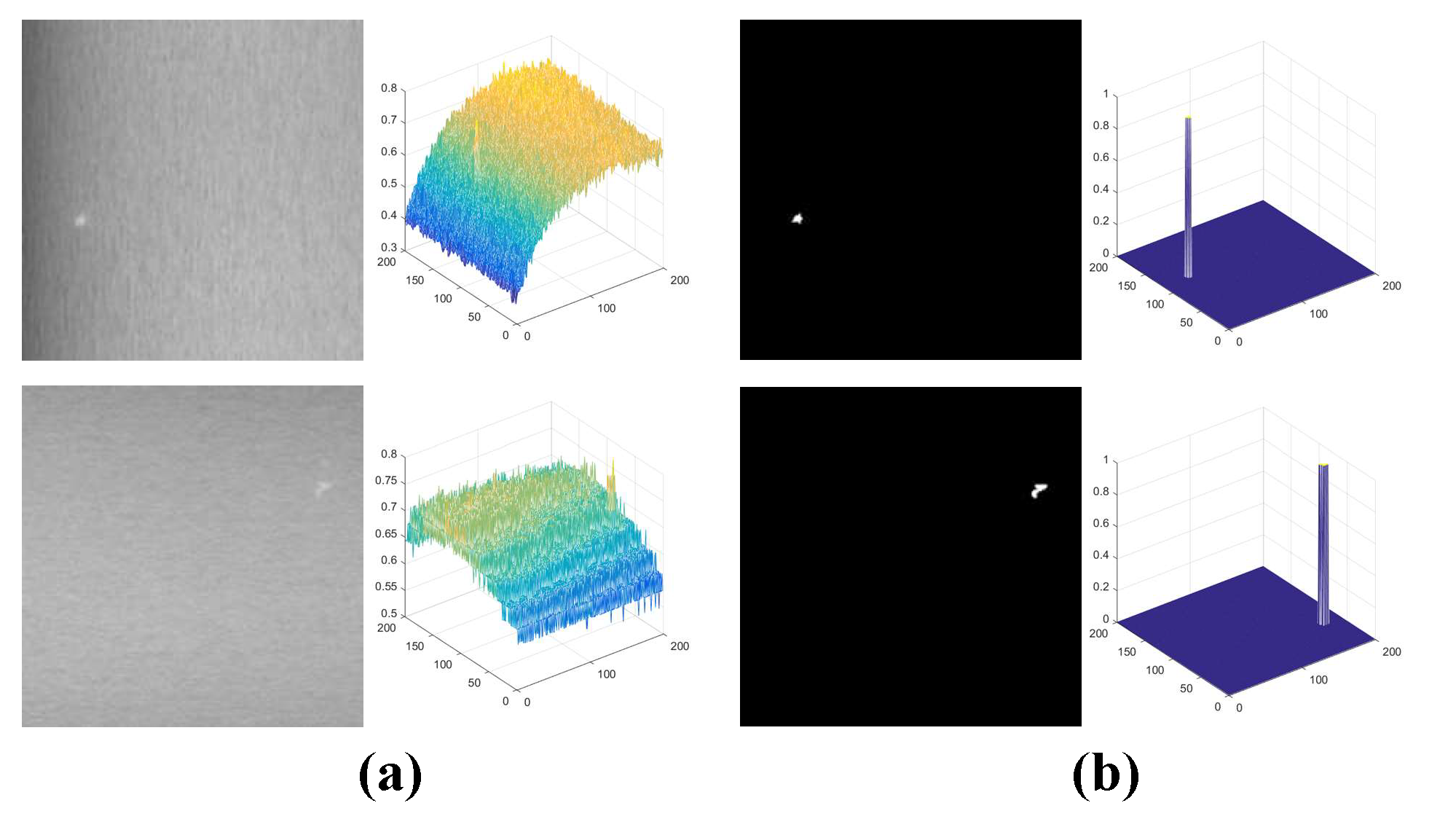

3.1. Construction of Tensor Model for Defect Image

3.2. Model Solution

| Algorithm 1: Solving Equation (11) |

| Input: , power p Output: |

| step 1: Conduct FFT operation: |

| step 2: Conduct SVD operation on each frontal slice of : |

| for do |

| , |

| Compute |

| for do |

| ; |

| end for |

| , ; |

| end for |

| for do |

| ; |

| end for |

| step 3: Compute |

| Algorithm 2: Solving Equation (7) by ADMM |

| Input: Original defect image sequence tensor , power p, , |

| Output: , , |

| Initialize: , , , , , , |

| While: not converged, do |

| step 1: Update by Equation (11) |

| step 2: Update by Equation (15) |

| step 3: Update by Equation (16) |

| step 4: Update by Equation (19) |

| step 5: Update by Equation (20) |

| step 6: Check the convergence condition |

| step 7: Update |

| end while |

3.3. Model Analysis

3.3.1. Computational Complexity

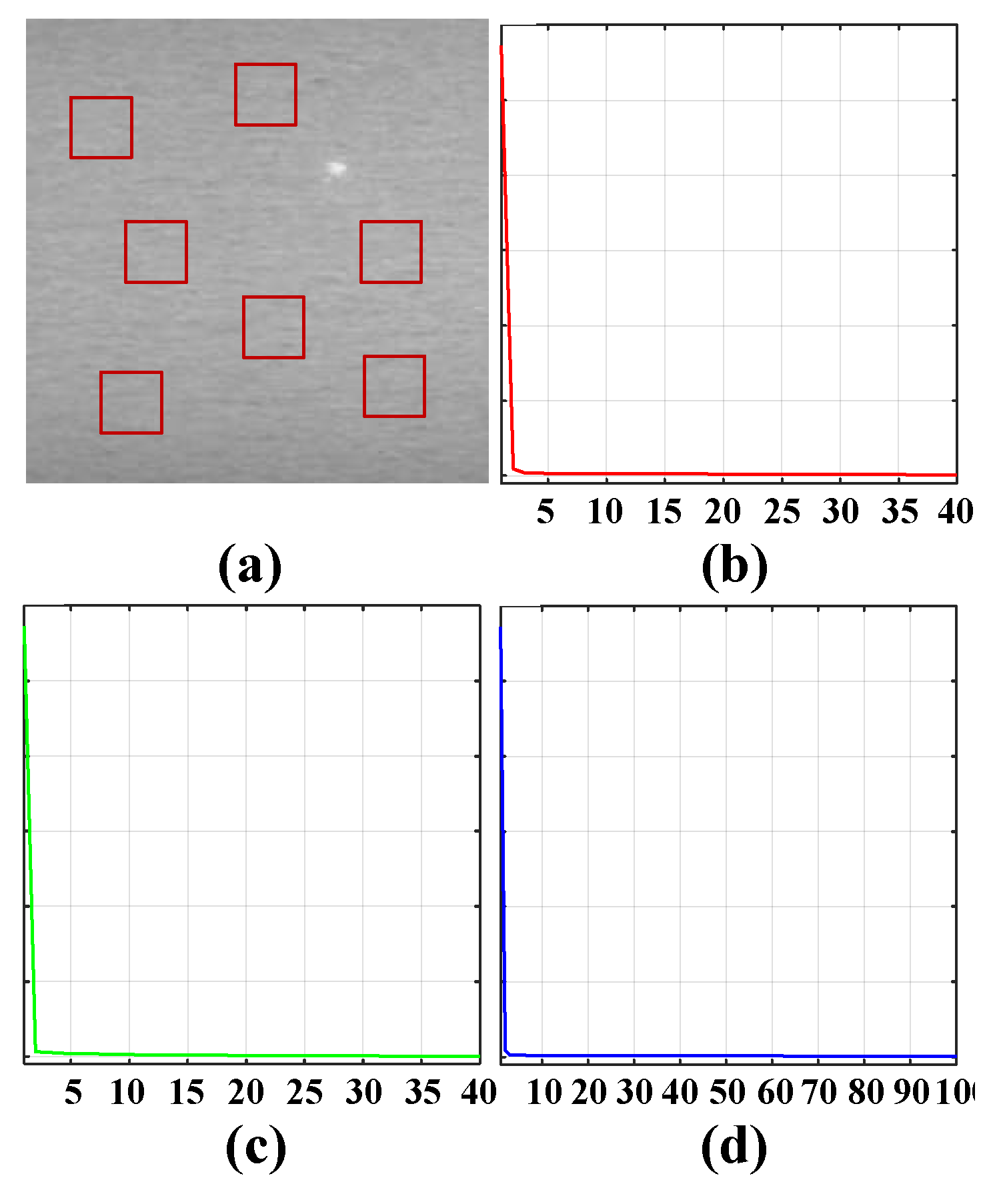

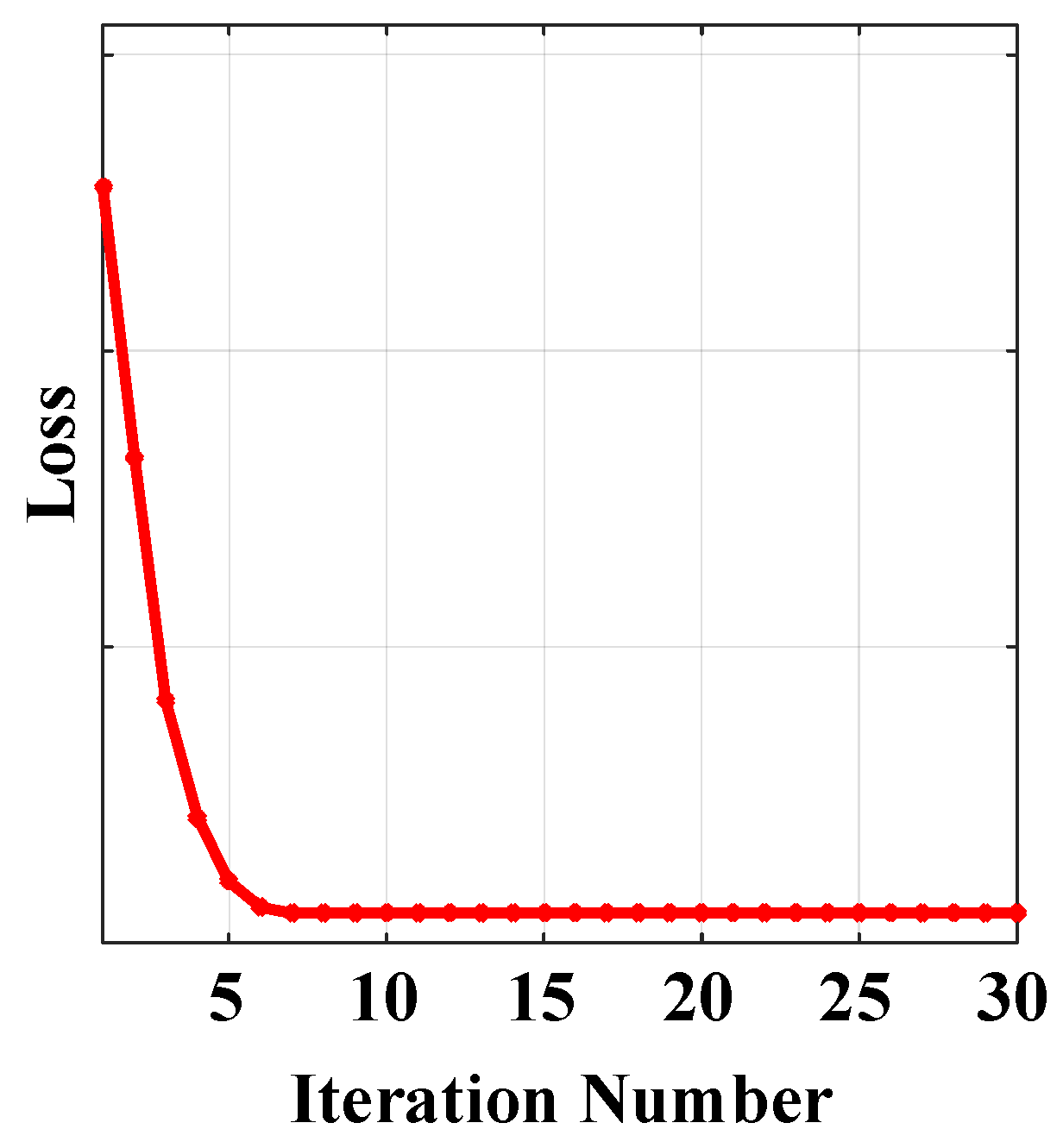

3.3.2. Convergence of Algorithm

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup

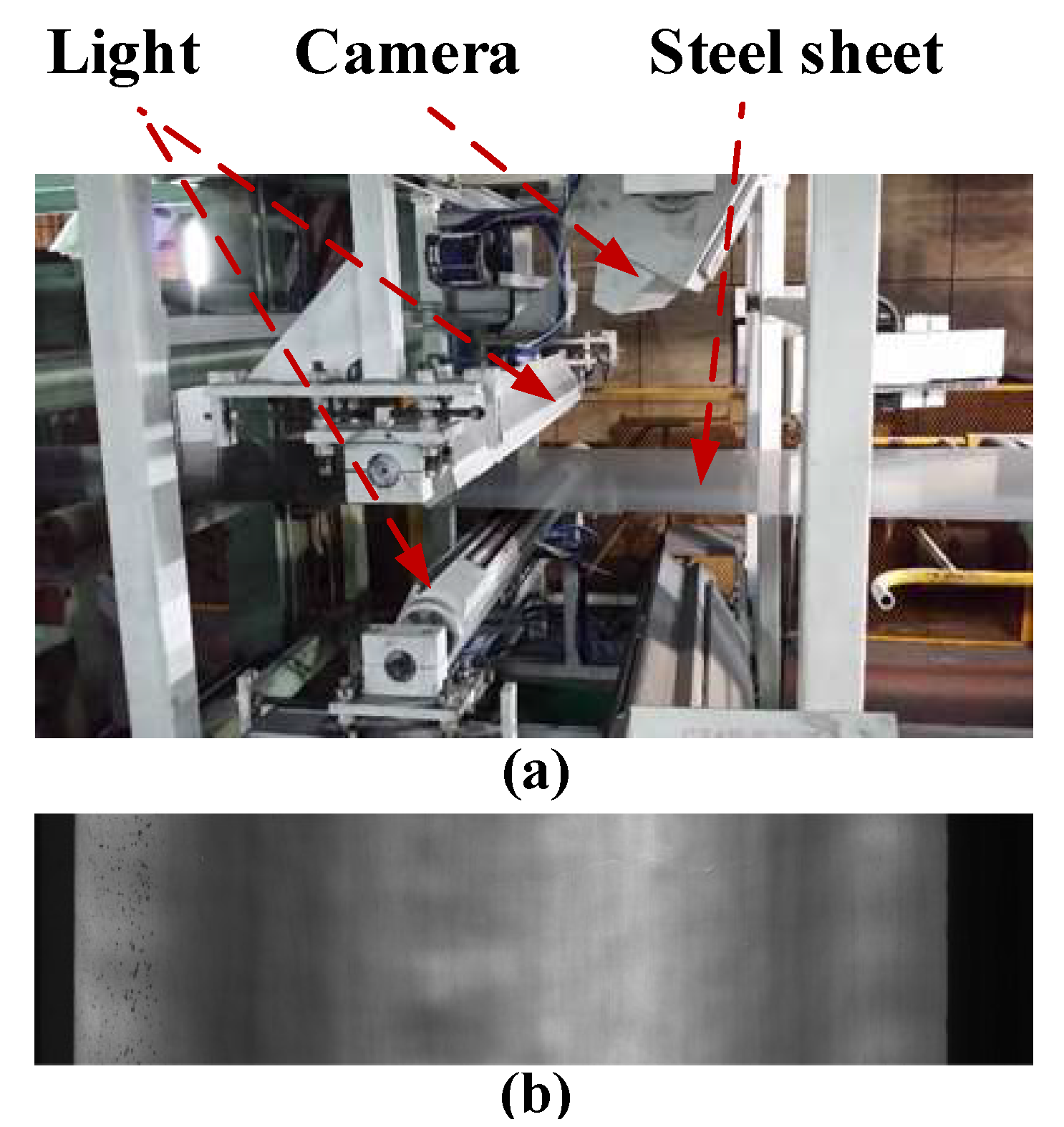

4.1.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

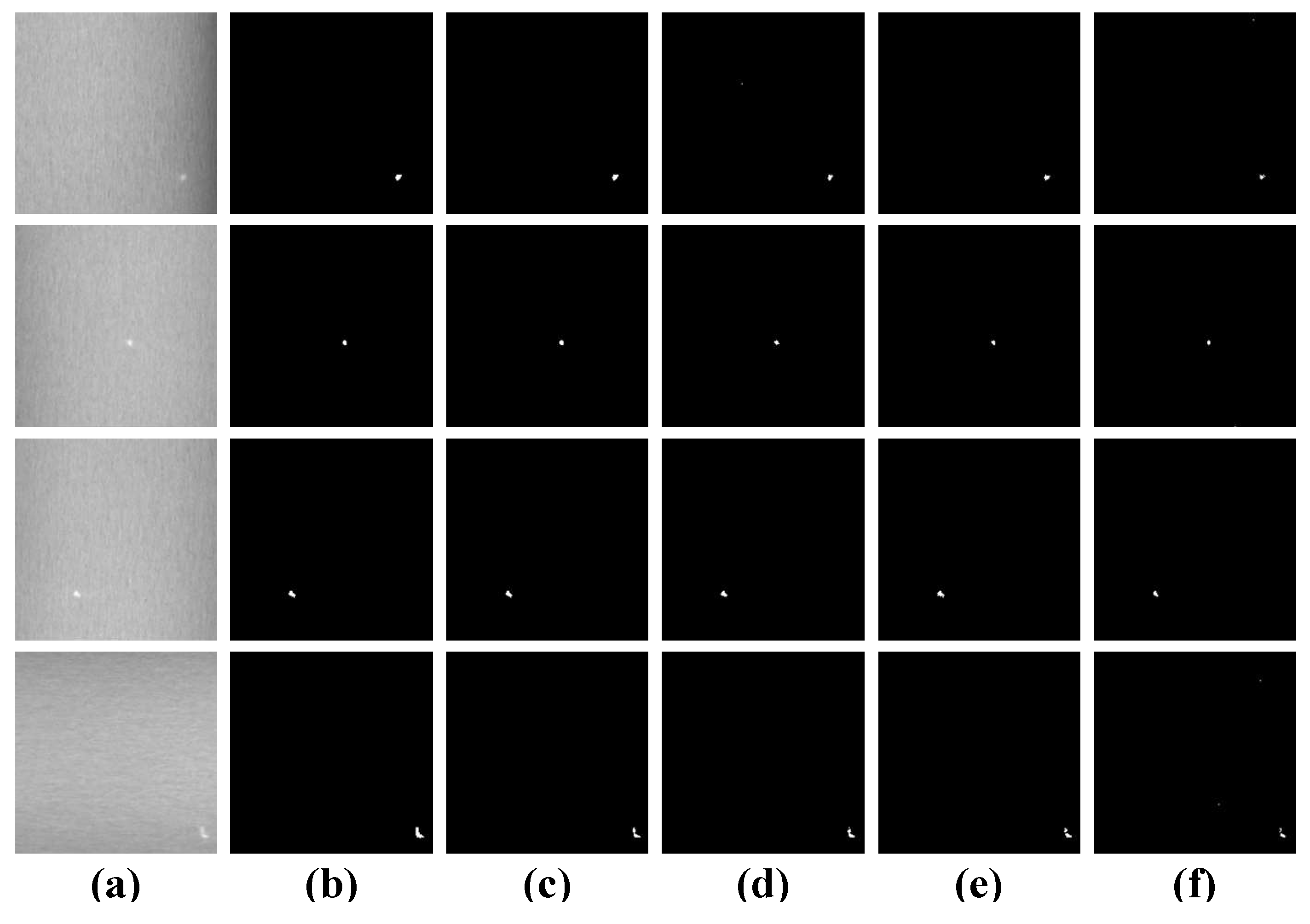

4.2. Validation of the Proposed Method

4.2.1. Parameter Analysis

4.2.2. Robustness to Noise

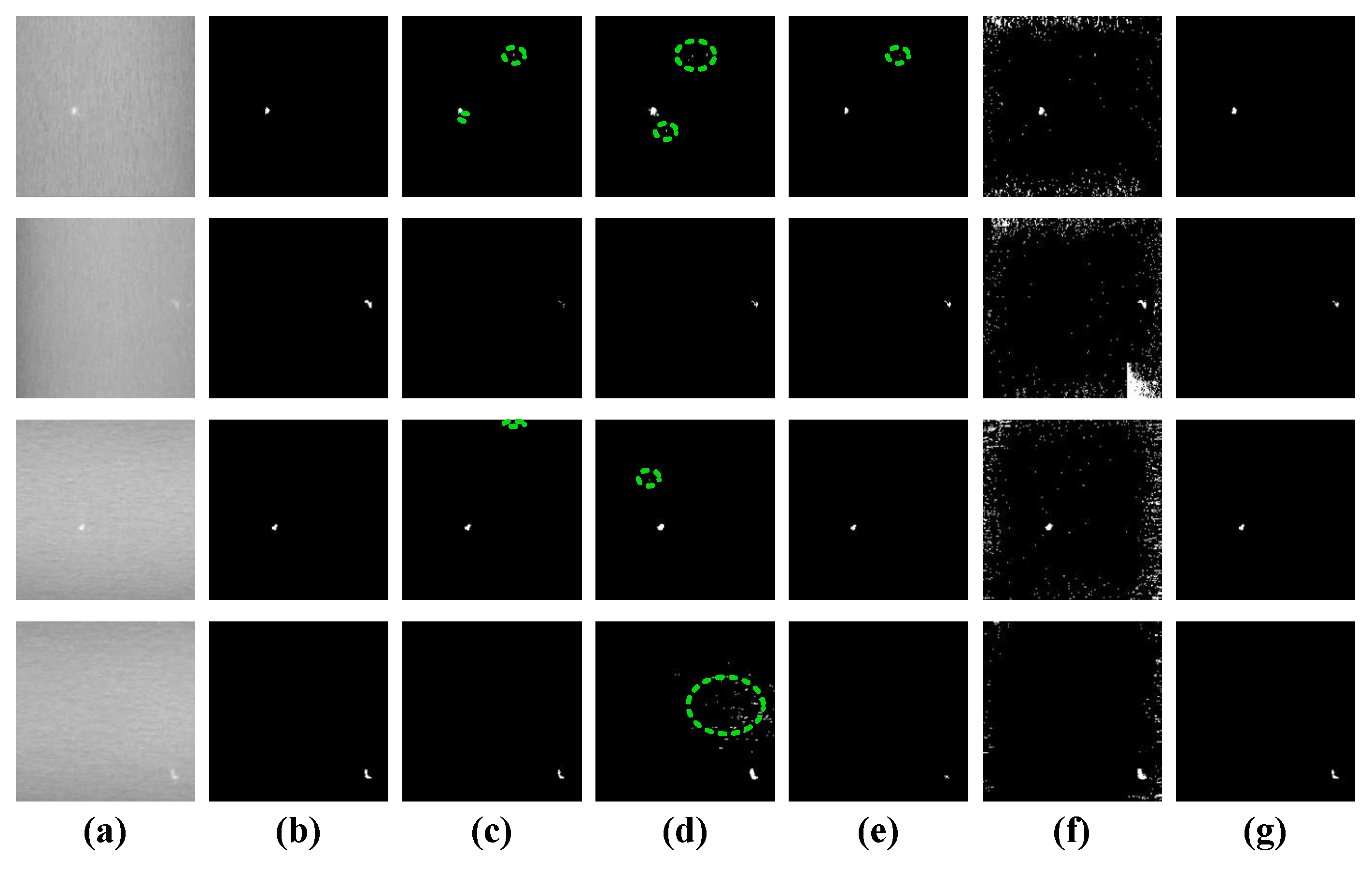

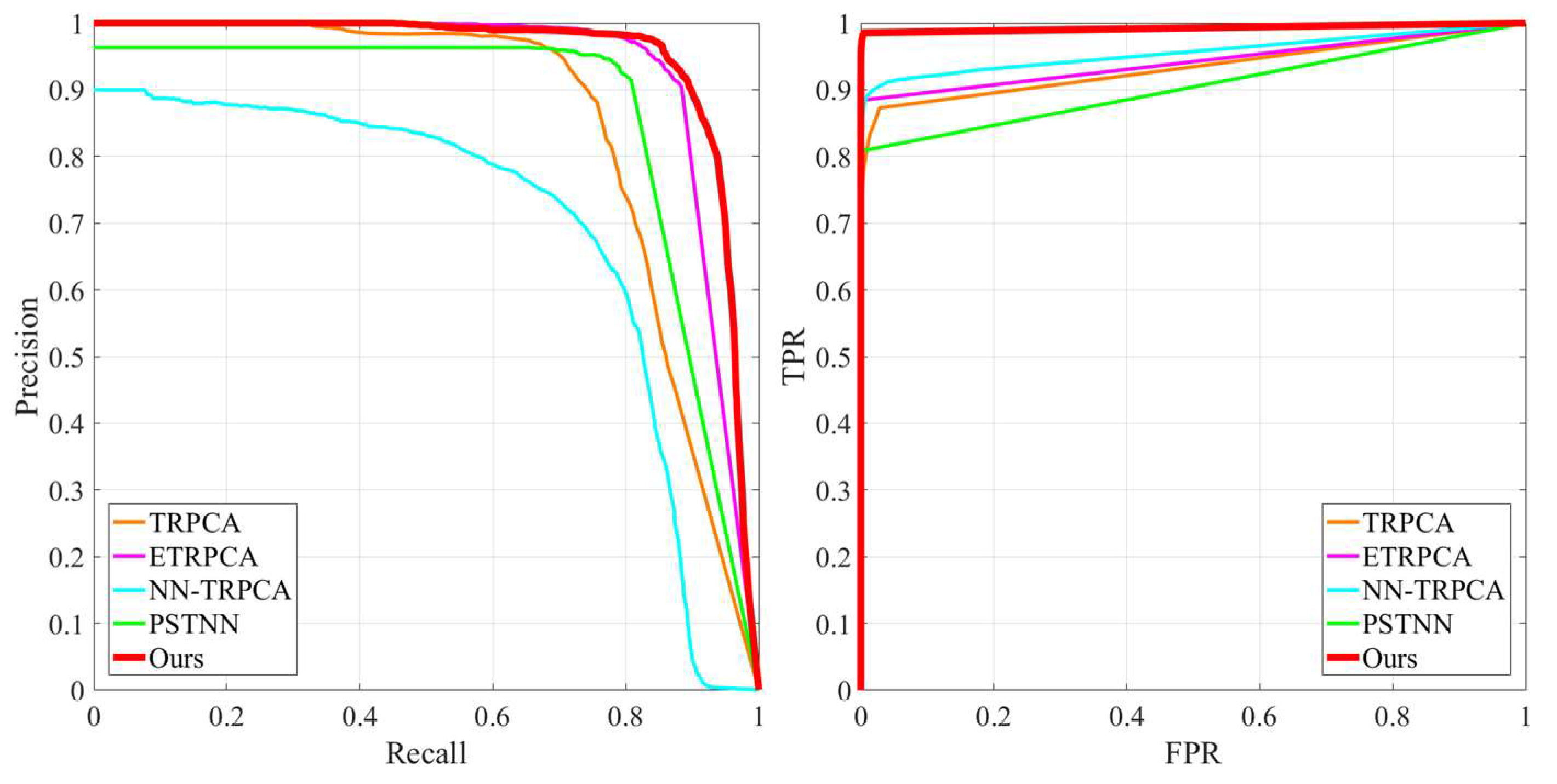

4.3. Comparison with the State-of the-Art Methods

4.3.1. Qualitative Comparison

4.3.2. Quantitative Comparison

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diers, J.; Pigorsch, C. A survey of methods for automated quality control based on images. INT. J. COMPUT. VISION 2023, 131, 2553–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.P.; He, G.H.; Zhou, P. MFNet: a novel multilevel feature fusion network with multibranch structure for surface defect detection. IEEE T. INSTRUM. MEAS. 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Yuan, X.; Yao, X.W.; Yan, K.B.; Zeng, Q.H.; Xie, X.X.; Han, J.W. Towards large-scale small object detection: survey and benchmarks. IEEE T. PATTERN. ANAL. 2023, 45, 13467–13488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.L.; Dong, Z.C. FASCNet: an edge-computational defect detection model for industrial parts. IEEE INTERNET. THINGS. 2023, 11, 6622–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.W.; Chen, Y.W.; Su, J.J.; Yang, C.H.; Silvén, O.; Liu, L. Prior-guided YOLOX for tiny roll mark detection on strip steel. IEEE SENS. J. 2024, 24, 15575–15587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, R.; Hsu, C.C.; Band, S.S. A systematic review of deep learning approaches for surface defect detection in industrial applications. ENG. APPL. ARTIF. INTEL. 2023, 130, 107717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M.; Hill, R.; Allen, P. A comprehensive review of convolutional neural networks for defect detection in industrial applications. IEEE ACCESS 2024, 12, 94250–94295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.X.; Chen, K.Y.; Shi, Z.W.; Guo, Y.H.; Ye, J.P. Object detection in 20 years: a survey. P. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.B.; Babiceanu, R.F. Deep CNN-based visual defect detection: survey of current literature. COMPUT. IND. 2023, 14, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.H.; Chu, M.X.; Gong, R.F.; Zheng, Z.H. Global attention module and cascade fusion network for steel surface defect detection. PATTERN RECOGN. 2024, 158, 110979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, A.; Ozdemir, A.; Iwen, M.A.; Aviyente, S. Extension of PCA to higher order data structures: an introduction to tensors, tensor decompositions, and tensor PCA. P. IEEE 2018, 106, 1341–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.G.; An, W. Infrared dim and small target detection via multiple subspace learning and spatial-temporal patch-tensor model. IEEE T. GEOSCI. REMOTE. 2020, 59, 3737–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yang, M. Low-rank tensor recovery via non-convex regularization, structured factorization and spatio-temporal characteristics. PATTERN RECOGN. 2023, 137, 109343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Hong, D.F.; Han, Z.; Li, J.X.; Yao, J.; Gao, L.R.; Zhang, B.; Chanussot, J. tensor decompositions for hyperspectral data processing in remote sensing: a comprehensive review. IEEE GEOSC. REM. SEN. M. 2023, 11, 26–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, X.R.; Chen, S.H. 5-D spatial-temporal information-based infrared small target detection in complex environments. PATTERN RECOGN. 2024, 158, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.Y.; Wu, P.S.; Wang, Z.D.; Li, H.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.H. A small-sized object detection oriented multi-scale feature fusion approach with application to defect detection. IEEE T. INSTRUM. MEAS. 2022, 71, 3507014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Shan, J.; He, Y.; Song, K. Steel surface defect recognition: a survey. COATINGS 2024, 37, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Y.; Xie, Q.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J. Tiny defect detection in high-resolution aero-engine blade images via a coarse-to-fine framework. IEEE T. INSTRUM. MEAS. 2021, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Li, M.; Miao, D.Q.; Pedrycz, W.; Wang, Z.G.; Jiang, M.H. Construction of a feature enhancement network for small object detection. PATTERN RECOGN. 2023, 143, 109801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.Q.; Liu, M.Q.; Zhang, S.L.; Wei, P.; Chen, B.D. CANet: contextual information and spatial attention based network for detecting small defects in manufacturing industry. PATTERN RECOGN. 2023, 140, 109558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Duan, G.F.; Tan, J.R. Residual shape adaptive dense-nested Unet: redesign the long lateral skip connections for metal surface tiny defect inspection. PATTERN RECOGN. 2023, 147, 110073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.Q. Reweighted infrared patch-tensor model with both nonlocal and local priors for single-frame small target detection. IEEE J-STARS. 2017, 10, 3752–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.Y.; Feng, J.S.; Chen, Y.D.; Liu, W.; Lin, Z.C.; Yan, S.C. Tensor robust principal component analysis with a new tensor nuclear norm. IEEE T. PATTERN ANAL. 2019, 42, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.D.; Peng, Z.M. Infrared small target detection based on partial sum of the tensor nuclear norm. REMOTE SENS-BASEL 2019, 11, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.X.; Zhang, P.; Xia, W.; Xie, D.Y.; Gao, X.B.; Tao, D.C. Enhanced tensor RPCA and its application. IEEE T. PATTERN ANAL. 2020, 43, 2133–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.Z.; Zhou, Z.X. Logarithmic norm regularized low-rank factorization for matrix and tensor completion. IEEE T. IMAGE PROCESS. 2021, 30, 3434–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, X.R.; Yan, Y.F.; Xia, C.Q. Spatial-temporal tensor representation learning with priors for infrared small target detection. IEEE T. AERO. ELEC. SYS. 2023, 59, 9598–9620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Peng, J.J.; Qin, W.J.; Wang, J.J.; Meng, D.Y. Guaranteed tensor recovery fused low-rankness and smoothness. IEEE T. PATTERN ANAL. 2023, 45, 10990–11007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.Y.; Guo, Q.; Hui, S.X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, C.M. Tensor robust PCA with nonconvex and nonlocal regularization. COMPUT. VIS. IMAGE UND. 2024, 243, 104007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.X.; Zhao, E.W.; Zheng, W.; Peng, X.D.; Niu, W.L.; Yang, Z. Infrared small target detection via two-stage feature complementary improved tensor low-rank sparse decomposition. IEEE J-STARS. 2024, 17, 17690–17709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gu, S.H.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, W.M.; Zhang, W.S.; Zhang, L. Weighted Schatten p-norm minimization for image denoising and background subtraction. IEEE T. IMAGE PROCESS. 2016, 25, 4842–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.G.; Li, M.; An, W. Infrared small target detection via spatial-temporal infrared patch-tensor model and weighted Schatten p-norm minimization. INFRARED PHYS. TECHN. 2019, 102, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.M.; Meng, D.Y.; Zhang, L.; Feng, X.C.; Zhang, D. A generalized iterated shrinkage algorithm for non-convex sparse coding. ICCV. 2013, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.Y.; Yang, M.; Gao, Q.X.; Song, W. Non-convex tensorial multi-view clustering by integrating l1-based sliced-Laplacian regularization and l2,p-sparsity. PATTERN RECOGN 2024, 154, 110605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patch | Step | AUC | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20×20 | 10 | 0.9341 | 0.0009 |

| 20 | 0.9712 | 0.0030 | |

| 30×30 | 10 | 0.9501 | 0.0007 |

| 20 | 0.9728 | 0.0019 | |

| 30 | 0.9775 | 0.0046 | |

| 40×40 | 10 | 0.9560 | 0.0005 |

| 20 | 0.9737 | 0.0017 | |

| 30 | 0.9769 | 0.0034 | |

| 40 | 0.9762 | 0.0034 | |

| 50×50 | 10 | 0.9589 | 0.0006 |

| 20 | 0.9732 | 0.0014 | |

| 30 | 0.9760 | 0.0021 | |

| 40 | 0.9744 | 0.0018 | |

| 50 | 0.9731 | 0.0015 |

| p | AUC | MAE |

|---|---|---|

| 0.4 | 0.9776 | 0.0017 |

| 0.7 | 0.9560 | 0.0005 |

| 1 | 0.9050 | 0.0005 |

| SNR | No Noise | 36dB | 32dB | 28dB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | |||||

| AUC | 0.9560 | 0.9386 | 0.9058 | 0.8272 | |

| MAE | 0.005 | 0.1610 | 0.1731 | 0.1939 | |

| Method | TRPCA | ETRPCA | NN-TRPCA | PSTNN | Ours | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | ||||||

| AUC | 0.9352 | 0.9259 | 0.9427 | 0.8925 | 0.9560 | |

| MAE | 0.0160 | 0.0004 | 0.0071 | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).