Submitted:

01 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Data Analysis

3. The Significance of Critical and Precious Minerals

3.1. Definition and Importance

3.2. Geopolitical and Economic Implications

3.3. Environmental and Social Impact of Traditional Mining

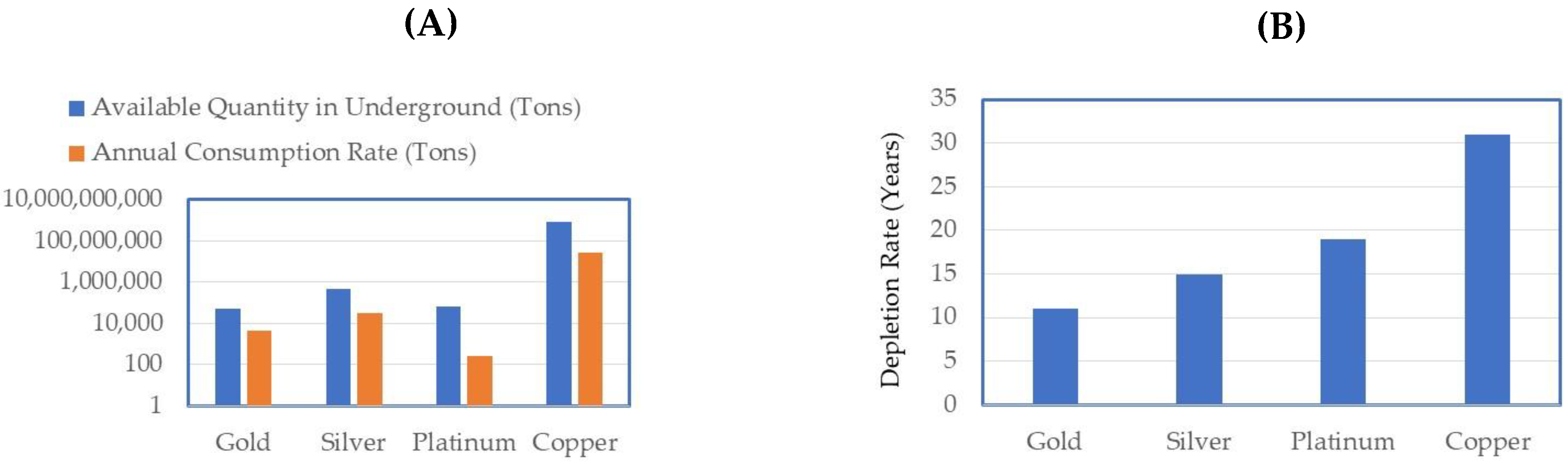

3.4. Growing Demand and Resource Depletion

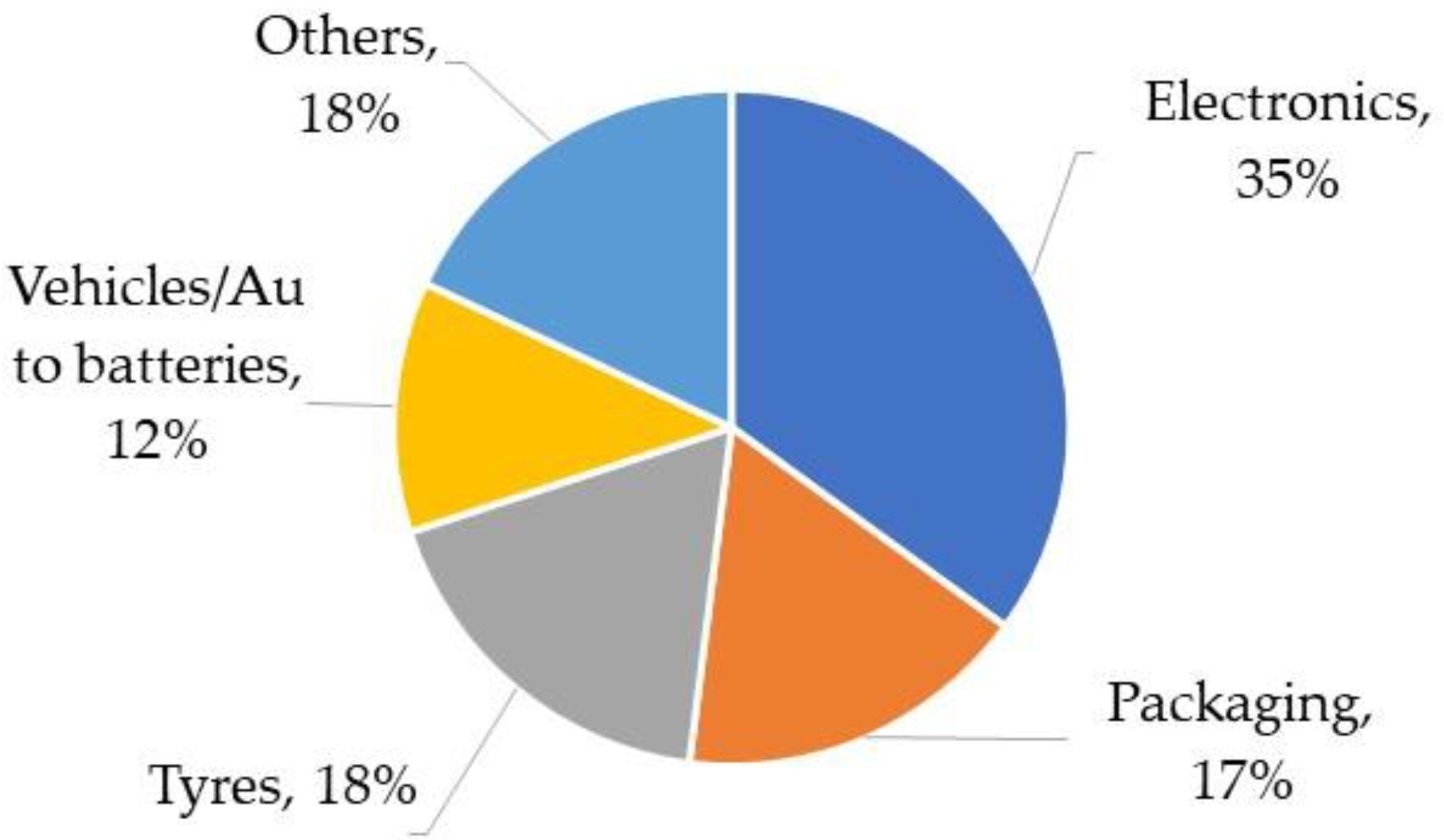

4. E-Waste as a Sustainable Resource

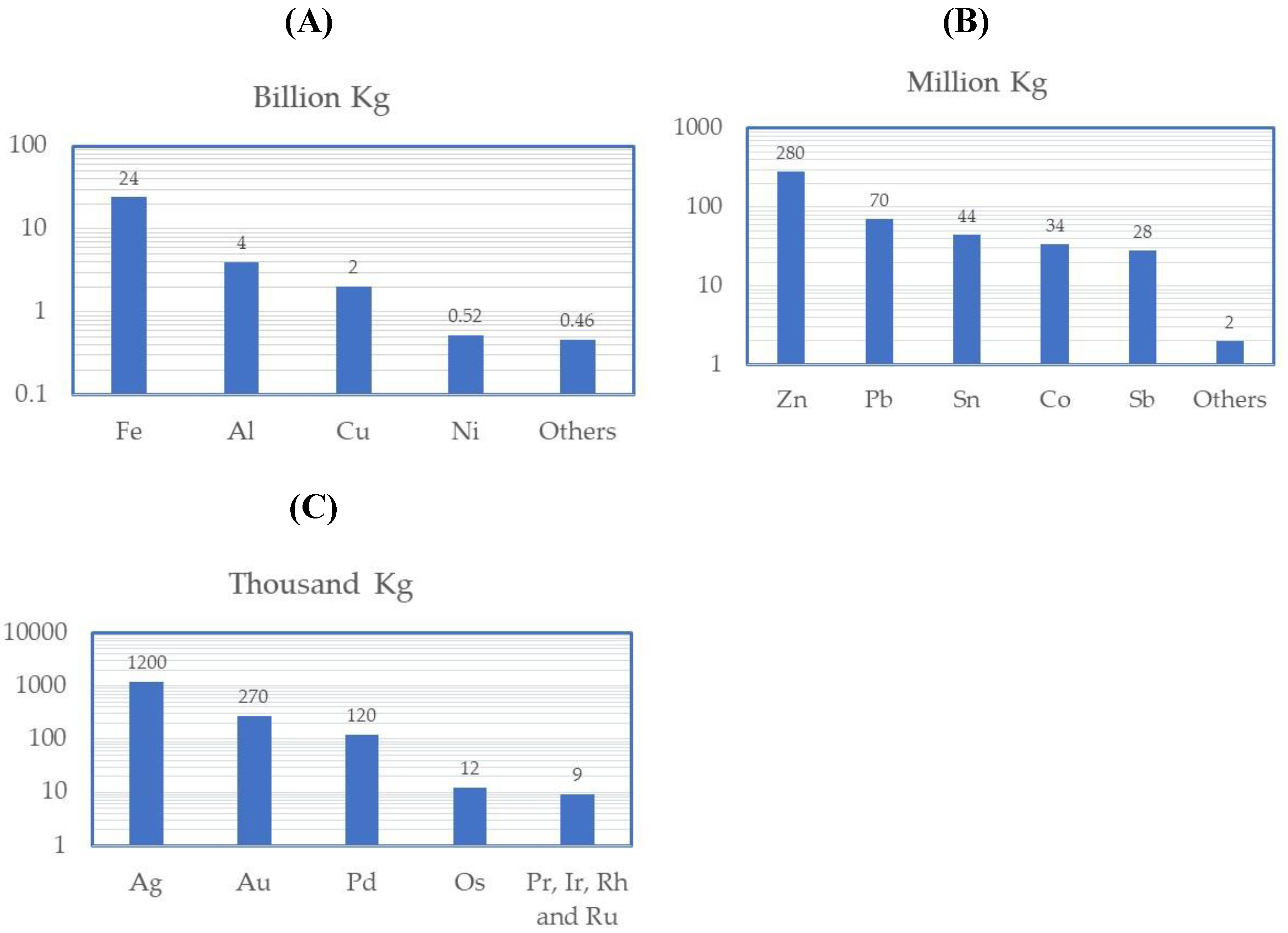

4.1. Composition and Availability

4.2. Environmental Benefits

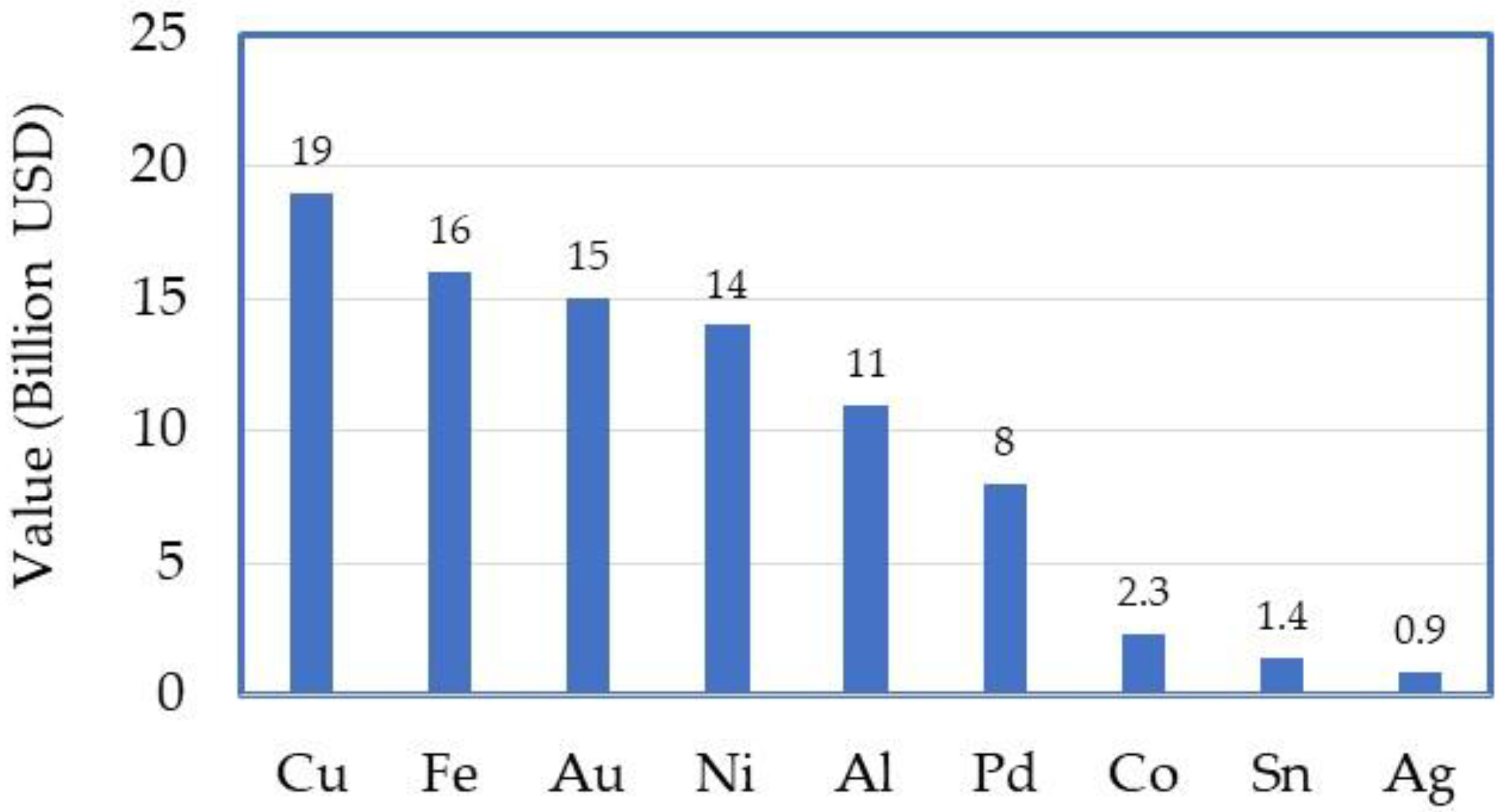

4.3. Economic Viability

4.4. Scalability and Potential for Circular Economy Integration

5. Technologies for Mineral Recovery from E-Waste

5.1. Physical and Mechanical Separation

5.2. Pyrometallurgical Processes

5.3. Hydrometallurgical Processes

5.4. Bio-Metallurgy

5.5. Electrochemical Processes

- Gold (Au) and Silver (Ag): Gold and silver are among the most valuable metals found in electronic waste. They are best recovered through hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical methods, both of which are highly effective in extracting these precious metals. Additionally, electrochemical processes can also be used to recover gold and silver with high purity, ensuring that these valuable materials are efficiently separated and refined.

- Copper (Cu): Copper is commonly found in e-waste, particularly in circuit boards and wiring. It can be efficiently extracted using hydrometallurgy, pyrometallurgy, and electrochemical methods. These processes ensure high recovery rates of copper, which is a key material in electronics due to its excellent conductivity and recyclability.

- Rare Earth Elements (REEs): The recovery of rare earth elements (REEs), such as neodymium and dysprosium, is a more challenging task, as traditional recovery methods often struggle to extract these elements efficiently. While bio-metallurgy (using microorganisms to extract metals) shows promise for REE recovery, it requires further research and optimization to enhance its effectiveness and scalability.

- Platinum Group Metals (PGMs): Platinum group metals, including platinum, palladium, and rhodium, are highly valuable but are typically found in smaller quantities in e-waste. The most effective recovery methods for PGMs are hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy, which allow for the extraction of these metals with high efficiency.

- Ferrous Metals (Fe, Ni, Co): Ferrous metals, such as iron (Fe), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co), are best recovered using physical separation methods, such as magnetic separation, or through pyrometallurgical techniques. These methods effectively separate ferrous metals from other materials, ensuring that they can be recycled and reused.

6. Challenges and Barriers

6.1. Technical Challenges

6.2. Economic Constraints

6.3. Regulatory and Policy Gaps

6.4. Consumer Participation and Awareness

7. Enhanced Strategies for Sustainable E-Waste Recycling

7.1. Adoption of Green Chemistry and Green Engineering in Design Processes

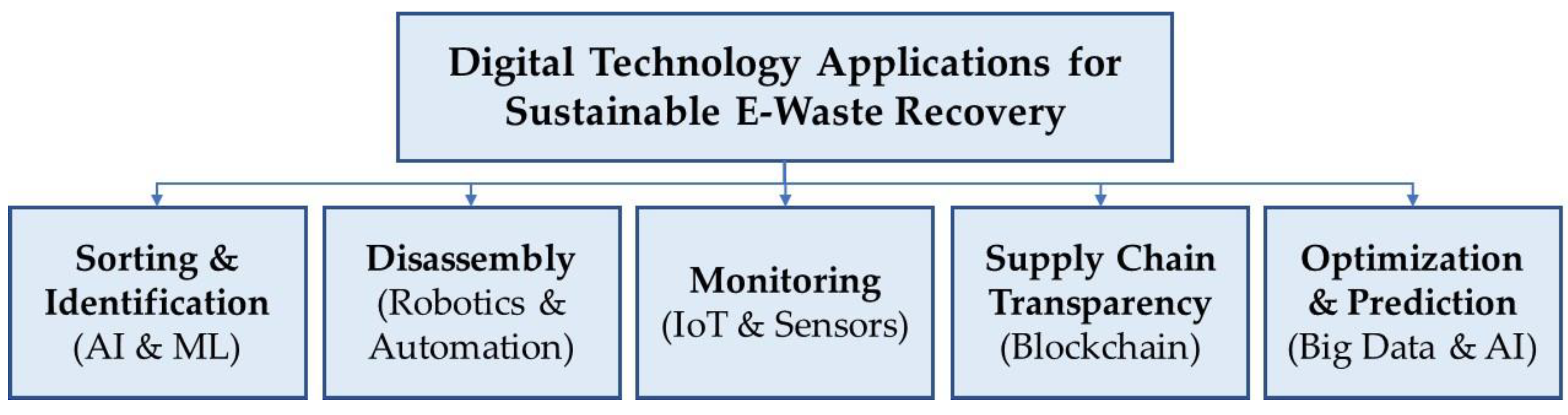

7.2. Employment of Digital Technologies

7.2.1. AI and Machine Learning for Sorting and Identification

7.2.2. IoT and Sensor-Based Monitoring

7.2.3. Blockchain for Supply Chain Transparency

7.2.4. Robotics and Automated Disassembly

7.2.5. Big Data and Predictive Analytics

7.2.6. AI-based Digital Simulation

7.2.7. Digital Twins for Process Optimization

7.3. Advance Processing Technologies

7.3.1. Chemical and Biotechnological Processing

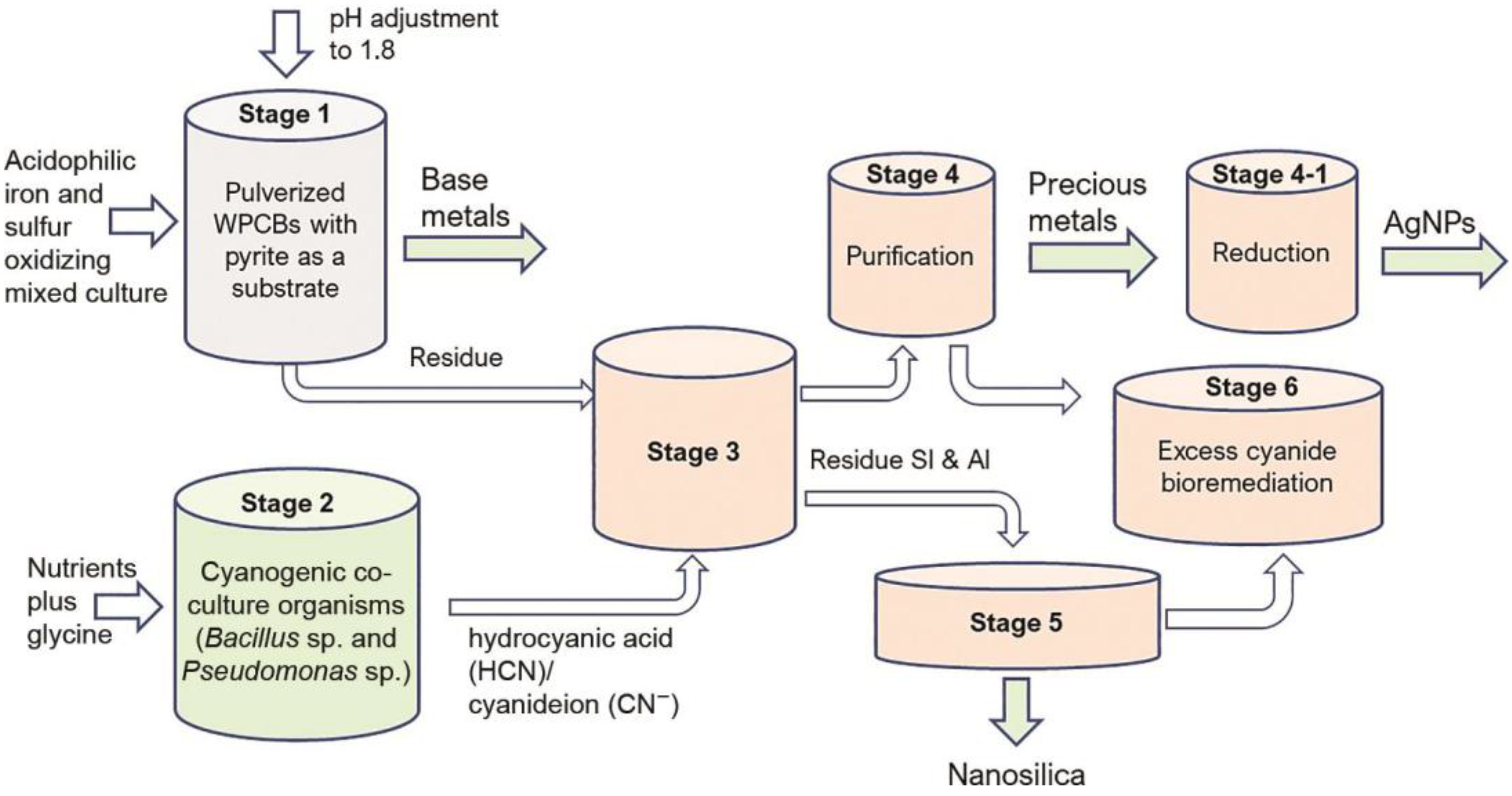

7.3.2. Multi-Stage Bioleaching and Bio-Recovery Process

7.3.3. Thermal and Electrochemical Processing

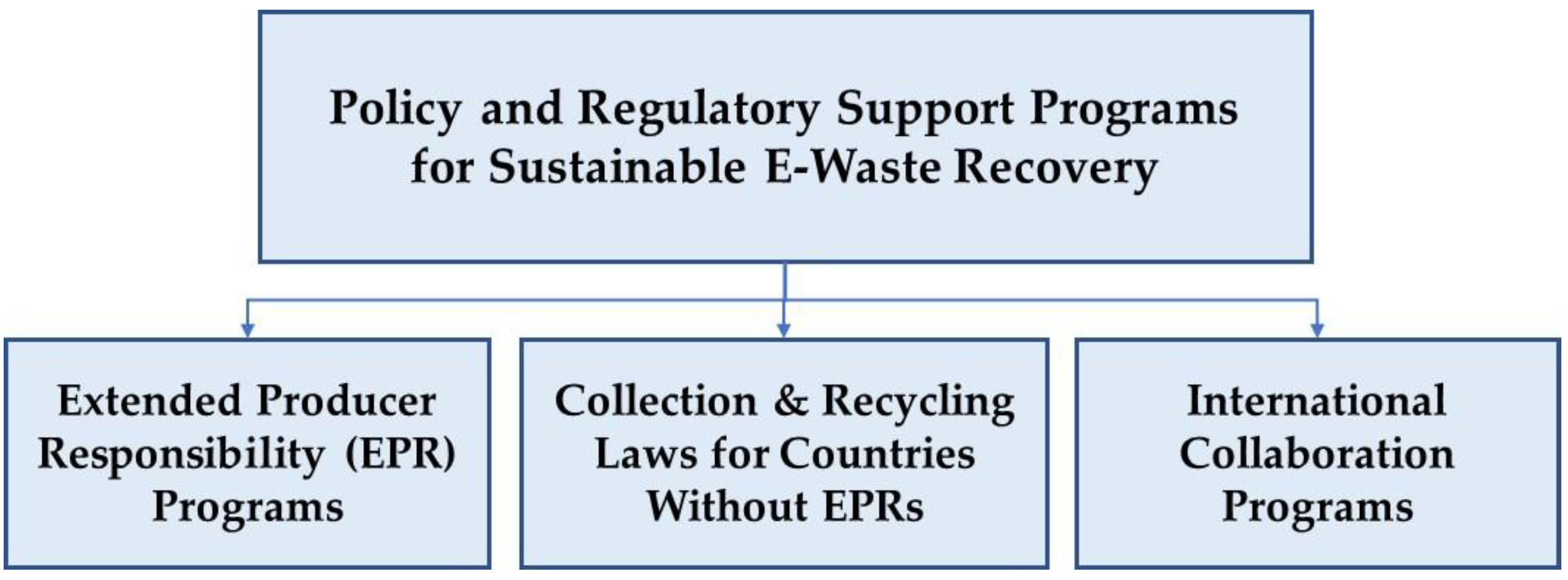

7.4. Policy and Regulatory Support

7.4.1. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Programs

7.4.2. E-Waste Collection and Recycling Laws

7.4.3. International Collaboration for E-Waste Management

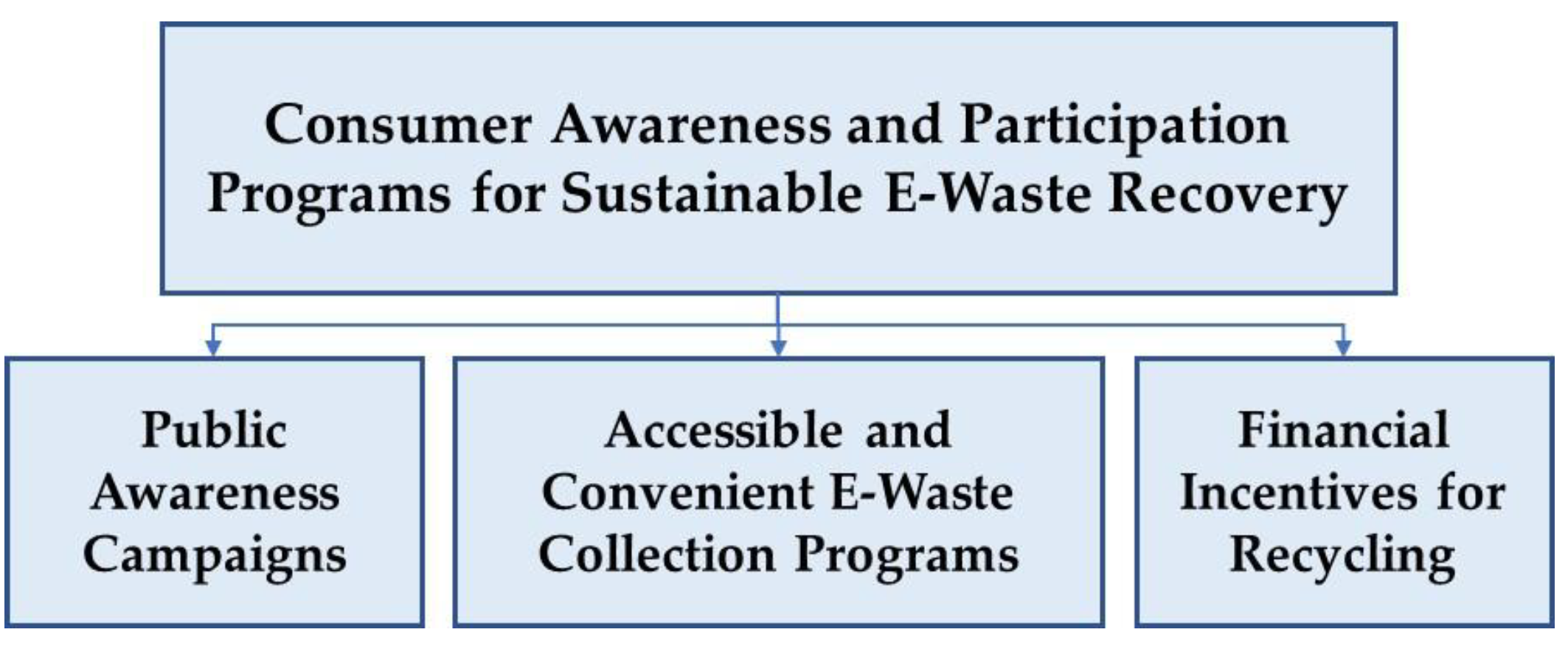

7.5. Consumer Awareness and Participation

7.5.1. Public Awareness Campaigns

7.5.2. Accessible and Convenient E-Waste Collection Programs

7.5.3. Financial Incentives for Recycling

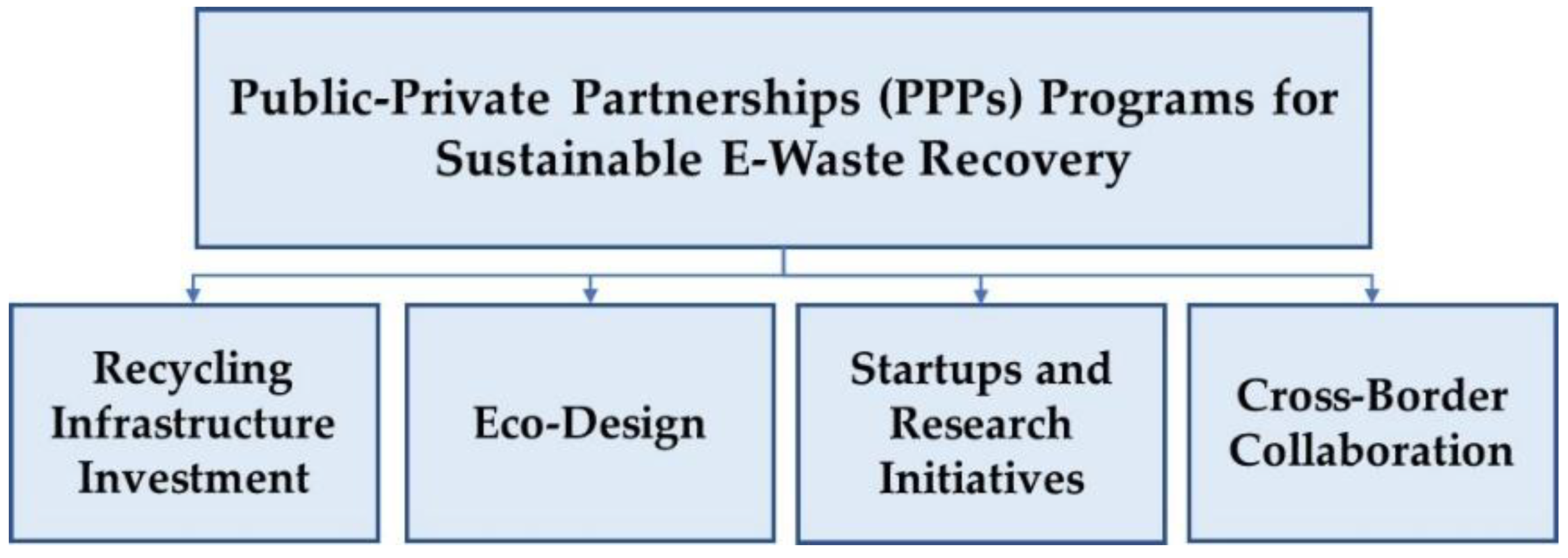

7.6. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in E-Waste Recycling

7.6.1. Investment in Recycling Infrastructure

7.6.2. Encouraging Eco-Design in the Tech Industry

7.6.3. Support for Startups and Research Initiatives

7.6.4. Cross-Border Collaboration

7.7. Case Studies and Best Practices for Sustainable E-Waste Recycling

8. Roadmap for E-Waste Sustainability Strategies

9. Conclusion

References

- Abdol Jani, W. N. F., F. Suja, S. I. Sayed Jamaludin, N. F. Mohamad, and N. H. Abdul Rani. 2023. Optimization of Precious Metals Recovery from Electronic Waste by Chromobacterium Violaceum Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Bioinorg. Chem. Appl., e4011670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul, K., R. Muhammad, B. Geoffrey, and M. Syed. 2014. Metal extraction processes for electronic waste and existing industrial routes: a review and Australian perspective. Resources 3: 152–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdulWaheed, K., A. Singh, A. Siddiqua, M. El Gamal, and M. Laeequddin. 2023. E-Waste recycling behavior in the United Arab Emirates: investigating the roles of environmental consciousness, cost, and infrastructure support. Sustainability 15: 14365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Amazon. Amazon Trade-in gives new life to old devices. Here’s how the program works. Available online: https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/devices/amazon-trade-in-program.

- Afroz, R., M. Muhibbullah, P. Farhana, and M. Morshed. 2020. Analyzing the intention of the households to drop off mobile phones to the collection boxes: empirical study in Malaysia. Ecofeminism and Climate Change 1: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V. V., and S. Ülkü. 2013. The role of modular upgradability as a green design strategy. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 15: 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwar, R., and A. K. Tripathi. 2021. E-waste management: a review of recycling process, environmental and occupational health hazards, and potential solutions. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag 15: 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. I., Y. B. Kar, C. Doroody, T. S. Kiong, K. S. Rahman, M. N. Harif, and N. Amin. 2023a. A comprehensive review of flexible cadmium telluride solar cells with back surface field layer. Heliyon 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., J. Steen, S. Ali, and R. Valenta. 2023b. Carbon-adjusted efficiency and technology gaps in gold mining. Resour. Policy. 81: 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W. A., and B. L. MacCarthy. 2023. Blockchain-enabled supply chain traceability–How wide? How deep? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 263: 108963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcil, A., C. Erust, C. S. Gahan, M. Ozgun, M. Sahin, and A. Tuncuk. 2015. Precious metal recovery from waste printed circuit boards using cyanide and non-cyanide lixiviants–a review. Waste Manag 45: 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akewar, M., and M. Chandak. 2024. Hyperspectral Imaging Algorithms and Applications: A Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akitsu, T. 2017. Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry Research of Metal Compounds. Intechopen Publishing: Available online: www.intechopen.com/books/5891.

- Al Rashid, A., and M. Koç. 2023. Additive manufacturing for sustainability and circular economy: needs, challenges, and opportunities for 3D printing of recycled polymeric waste. Mater. Today Sustain., 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ajmi, F., M. Al-Marri, and F. Almomani. 2025. Electrocoagulation Process as an Efficient Method for the Treatment of Produced Water Treatment for Possible Recycling and Reuse. Water 17: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameer, H. 2015. Integrated Framework for Modelling the Management of Electronic Waste in Saudi Arabia. Victoria University. [Google Scholar]

- Alamsyah, A., S. Widiyanesti, P. Wulansari, E. Nurhazizah, A. S. Dewi, D. Rahadian, and P. Tyasamesi. 2023. Blockchain traceability model in the coffee industry. J. Open Innov.: Technol., Mark., Complex. 9, 1: 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L., K. Sivaramakrishnan, M. Shafi Kuttiyathil, V. Chandrasekaran, H. Ahmed, O. Al-Harahsheh, and M. Altarawneh. 2023. Prediction of Thermogravimetric Data in Bromine Captured from Brominated Flame Retardants (BFRs) in e-Waste Treatment Using Machine Learning Approaches. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 0: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N. A.L., R. Ramly, A. A.B. Sajak, and R. Alrawashdeh. 2021. IoT E-Waste Monitoring System to Support Smart City Initiatives. International Journal of Integrated Engineering: vol. 13, 2, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Alias, C., D. Bulgari, F. Bilo, L. Borgese, A. Gianoncelli, G. Ribaudo, E. Gobbi, and I. Alessandri. 2021. Food Waste Assisted Metal Extraction from Printed Circuit Boards: The Aspergillus Niger Route. Microorganisms 9, 5: 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A. I. 2022. Household’s awareness and participation in sustainable electronic waste management practices in Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng J 13, 4: 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaf, S., C. W. Babbitt, and R. Chen. 2021. The evolution of consumer electronic waste in the United States. J Ind Ecol 25, 3: 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, C., F. Revellio, I. Tenner, and S. Schaltegger. 2022. The potential of modular product design on repair behavior and user experience–Evidence from the smartphone industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 367: 132770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananno, A. A., M. H. Masud, P. Dabnichki, M. Mahjabeen, and S. A. Chowdhury. 2021. Survey and analysis of consumers’ behaviour for electronic waste management in Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manag. 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P. T., and J. B. Zimmerman. 2003. Design through the Twelve Principles of Green Engineering. Env. Sci. Tech. 37, 5: 94A–101A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastas, P. T., and J. C. Warner. 1998. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, T. A. 2022. Comparative Study of National Variations of the European WEEE Directive: Manufacturer's View. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 14: 19920–19939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C. G. 2019. Antimony production and commodities. In mineral processing and extractive metallurgy handbook. Soc. Mining Metall. Expl. (SME): pp. 431–442. [Google Scholar]

- Andooz, A., M. Eqbalpour, E. Kowsari, S. Ramakrishna, and Z. A. Cheshmeh. 2022. A Comprehensive Review on Pyrolysis of EWaste and Its Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 333: 130191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, M., and K. Gurumurthy. 2020. Neural network prediction of bioleaching of metals from waste computer printed circuit boards using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Comput Intell 36, 4: 1548–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, L., R. Pummill, J. du-Brimpong, S. Becker, M. Green, M. Ilardi, E. Van Dam, and R. L. Neitzel. 2020. Analysis of e-waste recycling behavior based on survey at a Midwestern US University. Waste Management 105: 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Trevor. 2020. 20-Geothermal Energy. Letcher, Future Energy, 3rd ed. M. Trevor. Elsevier: pp. 431–445. ISBN 9780081028865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadi, M., F. Pourhossein, S. M. Mousavi, and S. Yaghmaei. 2021. Green Recovery of Cu-Ni-Fe from a Mixture of Spent PCBs Using Adapted A. Ferrooxidans in a Bubble Column Bioreactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 272: 118701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artang, S., A. Ghasemian, and I. Hameed. 2023. E-Waste Tracker: A Platform to Monitor e-Waste from Collection to Recycling. In Proceedings of the 37th ECMS International Conference on Modelling and Simulation (ECMS2023). Florence, Italy, vol. 37, ISBN 978-3-937436-80-7/978-3-937436-79-1. [Google Scholar]

- Asunis, F., G. Cappai, A. Carucci, M. Cera, G. D. Gioannis, G. P. Deidda, G. Farru, G. Massacci, A. Muntoni, M. Piredda, and A. Serpe. 2024. A Case Study Of Implementation Of Circular Economy Principles To Waste Management: Integrated Treatment Of Cheese Whey And Hi-Tech Waste. Detritus: vol. 28, p. 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y., P. K. Soori, and F. Ghaith. 2021. Analysis of households’ e-waste awareness, disposal behavior, and estimation of potential waste mobile phones towards an effective e-waste management system in Dubai. Toxics 9: 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, K., X. Zeng, and J. Li. 2016. Relationship between e-waste recycling and human health risk in India: critical review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23, 12: 11509–11532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwan, W. A. 2024. Electronic Waste (E-Waste) Generation and Management Scenario of India, and ARIMA Forecasting of E-Waste Processing Capacity of Maharashtra State till 2030. Waste Manag. Res. 1, 4: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, M., and R. Nidhi. 2025. E-Waste Management Rules 2022: Issues and Solution for Environmental Protection. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldé, C. P., R. Kuehr, T. Yamamoto, R. McDonald, E. D’Angelo, S. Althaf, G. Bel, O. Deubzer, E. Fernandez-Cubillo, V. Forti, V. Gray, S. Herat, S. Honda, G. toni, D. S. Khetriwal, V. L. di Cortemiglia, Y. Lobuntsova, I. Nnorom, N. Pralat, and M. Wagner. 2024. International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). 2024. Global E-waste Monitor 2024. Geneva/Bonn. Pdf version: 978-92-61-38781-5.

- Bansod, P. 2022. IoT Based Smart E-Waste Management System. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 10: 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrueto, Y., P. Hernandez, Y. Jimenez, and J. Morales. 2021. Leaching of Metals from Printed Circuit Boards Using Ionic Liquids. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 23, 5: 2028–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basel Convention. n.d.Available online: https://www.basel.int/theconvention/overview/tabid/1271/default.aspx (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Bassiouny, A. M., A. S. Farhan, S. A. Maged, and M. I. Awaad. 2021. Comparison of different computer vision approaches for e-waste components detection to automate e-waste disassembly. Proceedings of the 2021 International Mobile, Intelligent, and Ubiquitous Computing Conference (MIUCC), Cairo, Egypt; IEEE, pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Battelle. 2023. United States Energy Association: critical material recovery from e-waste. Final report. Subagreement no. 633-2023-004-01. Available online: https://usea.org/sites/default/files/USEA633-2023-004-01_CMfromEwaste_FINAL_REPORT.pdf.

- Bella, F., P. Renzi, C. Cavallo, and C. Gerbaldi. 2018. Caesium for perovskite solar cells: an overview. Chemistry European Journal 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2024. Beyond Surplus Embracing Sustainability with the Apple Recycle Program: Benefits and Best Practices. Electronics Recycling, IT Equipment Disposal & Data Destruction Blog. Available online: https://www.beyondsurplus.com/embracing-sustainability-apple-recycle-program/.

- Biswas, D., H. Jalali, A. H. Ansaripoor, and P. De Giovanni. 2023. Traceability vs. sustainability in supply chains: the implications of blockchain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 305, 1: 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, A., and M. Govind. 2017. Emerging trends in consumers’ ewaste disposal behaviour and awareness: a worldwide overview with special focus on India. Resour Conserv Recycl 117: 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, A., and M. Govind. 2017. Emerging trends in consumers’ e-waste disposal behavior and awareness: worldwide overview with special focus on India. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 117: 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschert, S., and R. Rosen. 2016. Edited by P. Hehenberger and D. Bradley. Digital Twin-The Simulation Aspect. In Mechatronic Futures: Challenges and Solutions for Mechatronic Systems and Their Designers. Springer International Publishing: pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.M., A. Mirkouei, D. Reed, and V. Thompson. 2023. Current nature-based biological practices for rare earth elements extraction and recovery: bioleaching and biosorption. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 173: 113099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, S. 2023. E-Waste no more: Fairphone and Framework show a better way forward for personal electronics. Available online: https://sustainablebrands.com/read/e-waste-no-more-fairphone-and-framework-show-a-better-way-forward-for-personal-electronics (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Bustamante, M. J. 2020. Using sustainability-oriented process innovation to shape product markets. Int. J. Innovat. Manag. 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, J. 2021. Lithium brine production, reserves, resources, & exploration in Chile: an updated review. Ore Geol. Rev. 128: 103883. [Google Scholar]

- Cabri, A., F. Masulli, S. Rovetta, and M. Mohsin. 2022. Recovering Critical Raw Materials from WEEE using Artificial Intelligence. Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Modelling and Applied Simulation, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, K., L. Wang, J. Ke, X. He, Q. Song, J. Hu, G. Yang, and J. Li. 2023. Differences and determinants for polluted area, urban and rural residents’ willingness to hand over and pay for waste mobile phone recycling: evidence from China. Waste Manag 157: 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, K., X. Xu, Y. Bian, and Y. Sun. 2019. Optimal trade-in strategy of business-to-consumer platform with dual-format retailing model. Omega 82: 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J., S. Cowie, P. Stewart, E. Jones, and A. Offer. 2018. Machine Learning at a Gold-Silver Mine: A case study from the Ban Houayxai Gold-Silver Operation. In Proceedings of the Complex Orebodies Conference 2018, Brisbane, Australia, November 19–21; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2023. Catelli, E., Zelan Li, Giorgia Sciutto, Paolo Oliveri, Silvia Prati, Michele Occhipinti, Alessandro Tocchio, Roberto Alberti, Tommaso Frizzi, Cristina Malegori, Rocco Mazzeo. Towards the non-destructive analysis of multilayered samples: A novel XRF-VNIR-SWIR hyperspectral imaging system combined with multiblock data processing. Analytica Chimica Acta 1239: 340710. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerchier, P., M. Dabala, and K. Brunelli. 2017. Gold Recovery from PCBs with Thiosulfate as Complexing Agent. Mater. Sci. Forum 879: 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A., R. Das, and J. Abraham. 2020. Bioleaching of heavy metals from spent batteries using Aspergillus nomius JAMK1. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 17: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G., P. R. Jadhaob, K. K. Pant, and K. D. P. Nigam. 2018. Novel technologies and conventional processes for recovery of metals from waste electrical and electronic equipment: challenges & opportunities–a review. J Environ Chem Eng 6: 1288–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G., P.R. Jadhaob, K. K. Pant, and K. D. P. Nigam. 2018. Novel technologies and conventional processes for recovery of metals from waste electrical and electronic equipment: challenges & opportunities–a review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6: 1288–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., J. Zhang, Z. Yu, and X. Zhao. 2024. Structure and evolution of global lead trade network: an industrial chain perspective. Resour. Policy. 90: 104735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., H. Shang, Y. Ren, Y. Yue, H. Li, and Z. Bian. 2022. Systematic Assessment of Precious Metal Recovery to Improve Environmental and Resource Protection. ACS ES&T Eng 2, 6: 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunxiang, C., H. BaoMin, Z. Lichen, and L. Shuangjin. 2011. Titanium alloy production technology, market prospects and industry development. Materials Design 32: 1684–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. 2022. iFixit and Samsung are now selling repair parts for some Galaxy devices [Online]. The Verge. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2022/8/2/23288062/ifixit-samsung-repair program-galaxy-s20-s21-tab-s7-plus (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Collins, B. 2018. Anglo using ‘Digital Twins’, Robotics to Boost Mining: Q&A. Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Available online: https://about.bnef.com/blog/anglo-using-digital-twins-robotics-boost-mining-qa/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Cooper, J., and J. Beecham. 2013. A study of platinum group metals in three-way autocatalysts. Platin Met. Rev. 57: 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, F., N. M. Gusmerotti, and M. Frey. 2020. Consumer’s circular behaviors in relation to the purchase, extension of life, and end of life management of electrical and electronic products: a review. Sustain. Times 12: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Peluzo, B. M., and E. Kraka. 2022. Uranium: the nuclear fuel cycle and beyond. Intern. J. Molecular Sci. 23: 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzio, C., G. Viglia, L. Lemarie, and S. Cerutti. 2023. Toward an integration of blockchain technology in the food supply chain. J. Bus. Res. 162: 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiella, F., I. D’Adamo, S. L. Koh, and P. Rosa. 2015. Recycling of WEEEs: an economic assessment of present and future e-waste streams. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 51: 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J., and L. Zhang. 2008. Metallurgical recovery of metals from electronic waste: a review. J Hazard Mater 158: 228–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J., and L. Zhang. 2008. Metallurgical recovery of metals from electronic waste: a review. J Hazard Mater 158: 228–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D., and P. Dutta. 2022. Product return management through promotional offers: The role of consumers’ loss aversion. International Journal of Production Economics 251: 108520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daware, S., S. Chandel, and B. Rai. 2022. A machine learning framework for urban mining: a case study on recovery of copper from printed circuit boards. Miner Eng 180: 107479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hollander, M. C., C. Bakker, and E. J. Hultink. 2017. Product design in a circular economy: development of a typology of key concepts and terms. J. Ind. Ecol. 21: 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DER. 2019. Design for Electronics Recycling: Best Practices. Available online: https:// resources.pcb.cadence.com/blog/2019-design-forelectronics-recycling-best-practices (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Dhir, A., S. Malodia, U. Awan, M. Sakashita, and P. Kaur. 2021. Extended valence theory perspective on consumers’ e-waste recycling intentions in Japan. J Clean Prod 312: 127443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A., N. Koshta, R. K. Goyal, M. Sakashita, and M. Almotairi. 2021a. Behavioral reasoning theory (BRT) perspectives on E-waste recycling and management. J. Clean. Prod. 280: 124269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A., S. Malodia, U. Awan, M. Sakashita, and P. Kaur. 2021b. Extended valence theory perspective on consumers’ e-waste recycling intentions in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 312: 127443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L. A., G. G. Clark, and T. E. Lister. 2017. Optimization of the Electrochemical Extraction and Recovery of Metals from Electronic Waste Using Response Surface Methodology. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 26: 7516–7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFilippo, N. M., and M. K. Jouaneh. 2017. A system combining force and vision sensing for automated screw removal on laptops. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng 15: 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilshara, P., B. Abeysinghe, R. Premasiri, N. Dushyantha, N. Ratnayake, S. Senarath, A. Sandaruwan Ratnayake, and N. Batapola. 2024. The role of nickel (Ni) as a critical metal in clean energy transition: applications, global distribution and occurrences, production-demand and phytomining. J. Asian Earth Sci. 259: 105912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive. 2012. 2012/19/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE), Text with EEA Relevance. Off. J. Eur. Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2012/19/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32012L0019.

- Dostal, J. 2017. Rare earth element deposits of alkaline igneous rocks. Resources 6: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, M. A., and S. Salehpour. 2014. Applying the Principles of Green Chemistry to Polymer Production Technology. Macromol. React. Eng. 8: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarahy, A. M., M. G. Eloffy, A. K. Priya, A. Hammad, M. Zahran, A. Maged, and K. Z. Elwakeel. 2024. Revitalizing the circular economy: An exploration of e-waste recycling approaches in a technological epoch. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 7: 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental R&D. 2023. Korea environmental industry and technology institute. Available online: https://www.keiti.re.kr/site/eng/02/10219000000002020092205.jsp (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Escobar-Pemberthy, N., and M. Ivanova. 2020. Implementation of Multilateral Environmental Agreements: Rationale and Design of the Environmental Conventions Index. Sustainability 12, 17: 7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. n.d.Horizon Europe. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe_en (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- European Commission. 2019. Communication on ‘The European Green Deal’ [WWW Document]. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/communication-european-gree n-deal_en.

- European Commission. 2023. Study on the critical raw materials for the EU 2023: final report. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/ areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials_en.

- E-Waste (Management) Rules. 2016. Available online: https:// www.google.com/url?\sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web& cd=&ved=2ahUKEwj1ppjivfuDAxVB2AIHHQlg Ag8QFnoECBYQAQ&url=https%3A%2F% 2Fgreene.gov.in%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018% 2F01%2FEWM-Rules-2016-english23.03.2016.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1luqSO41p0g_GBiVPFS0n&opi=89978449.

- E-Waste (Management) Rules. 2022. Available online: https://cpcb.nic.in/uploads/Projects/E-Waste/e-waste_rules_2022.pdf.

- Fan, C., C. Xu, A. Shi, M. P. Smith, J. Kynicky, and C. Wei. 2023. Origin of heavy rare earth elements in highly fractionated peraluminous granites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta Volume 343: 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, F., R. Golmohammadzadeh, and C. A. Pickles. 2022. Potential and Current Practices of Recycling Waste Printed Circuit Boards: A Review of the Recent Progress in Pyrometallurgy. J. Environ. Manage. 316: 115242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farjana, M., A. B. Fahad, S. E. Alam, and M. M. Islam. 2023. An IoT-and Cloud-Based E-Waste Management System for Resource Reclamation with a Data-Driven Decision-Making Process. IoT 4: 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W. L., R. Kotter, P. G. Özuyar, I. R. Abubakar, J. H. P. P. Eustachio, and N. R. Matandirotya. 2023. Understanding rare earth elements as critical raw materials. Sustainability 15: 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornalczyk, A., J. Willner, K. Francuz, and J. Cebulski. 2013. E-waste as a source of valuable metals. October 2013. Archives of Materials Science and Engineering 63, 2: 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Forti, V., C. P. Baldé, R. Kuehr, and G. Bel. 2020. The global e-waste monitor 2020. Bonn/Geneva/Rotterdam: United Nations University (UNU), International Telecommunication Union (ITU) & International Solid Waste Association (ISWA). 120. [Google Scholar]

- Forti, V., C. P. Balde, R. Kuehr, and G. Bel. 2020. Global E-Waste Monitor 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Funari, V., H. I. Gomes, D. Coppola, G. A. Vitale, E. Dinelli, M. de Pascale, and Rovere. 2021. Opportunities and threats of selenium supply from unconventional and low-grade ores: a critical review. Resources Conserv. Recycl. 170: 105593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G. M. 2009. Biosorption: Critical Review of Scientic Rationale, Environmental Importance and Significance for Pollution Treatment. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 84, 1: 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcıa-Balboa, C., P. Martınez-Aleson Garcıa, V. LopezRodas, E. Costas, and B. Baselga-Cervera. 2022. Microbial Biominers: Sequential Bioleaching and Biouptake of Metals from Electronic Scraps. MicrobiologyOpen 11, 1: e1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S., A. Ahmad, D. Madsen, and S. S. Sohail. 2023. Sustainable behavior with respect to managing E-wastes: factors influencing E-waste management among young consumers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 20: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, D., P. Lathwal, and S. C. Lopez Rocha. 2023. Unleashing the Power of Hydrogen For the Clean Energy transition. Sustainable energy For All. World Bank Blogs. [Google Scholar]

- Gilal, F. G., S. M. M. Shah, S. Adeel, R. G. Gilal, and N. G. Gilal. 2022. Consumer e-waste disposal behaviour: a systematic review and research agenda. Int J Consum Stud 46: 1785–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F. G., S. M. M. Shah, S. Adeel, R. G. Gilal, and N. G. Gilal. 2022. Consumer e-waste disposal behaviour: a systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 46: 1785–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar-Ahmadi, M., and S. M. Mousavi. 2021. Extraction of Valuable Metals from Discarded AMOLED Displays in Smartphones Using Bacillus Foraminis as an AlkaliTolerant Strain. Waste Manag 131: 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. 2021. Digital Twin Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by End-Use (Automotive & Transport, Retail & Consumer Goods, Agriculture, Manufacturing, Energy & Utilities), by Region, and Segment Forecasts. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/digital-twin-market (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Gupta, M. 2024. India’s E-Waste Management Rules 2022: Strengthening Recycling and Promoting a Circular Economy. Available online: https://solarquarter.com/2024/12/20/indias-e-waste-management-rules-2022-strengthening-recycling-and-promoting-a-circular-economy/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Gupta, S., S. Modgil, T. M. Choi, A. Kumar, and J. Antony. 2023. Influences of artificial intelligence and blockchain technology on financial resilience of supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 261: 108868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelstein, K. 2009. Globally sustainable manganese metal production and use. J. Environm. Management 90: 3736–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen, T., and A. Colicev. 2023. Blockchain-enabled advances (BEAs): implications for consumers and brands. J. Bus. Res. 160: 113763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E. G., F. Grosse-Dunker, and R. Reichwald. 2009. Sustainability innovation cube-a framework to evaluate sustainability-oriented innovations. Int. J. Innovat. Manag. 13: 683–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H., I. M. M. Rahman, Y. Egawa, H. Sawai, Z. A. Begum, T. Maki, and S. Mizutani. 2013. Recovery of Indium from End-of-Life Liquid-Crystal Display Panels Using Aminopolycarboxylate Chelants with the Aid of Mechanochemical Treatment. Microchem. J. 106: 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X., Y. You, W. Li, Y. Cao, L. Bi, and Z. Liu. 2024. The enrichment mechanism of indium in Fe-enriched sphalerite from the Bainiuchang Zn-Sn polymetallic deposit, SW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 167: 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y., E. Ma, and Z. Xu. 2014. Recycling Indium from Waste Liquid Crystal Display Panel by Vacuum CarbonReduction. J. Hazard. Mater. 268: 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henckens, M. L., P. P. Driessen, and E. Worrell. 2018. Molybdenum resources: their depletion and safeguarding for future generations. Res., Conserv., Recycl. 134: 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

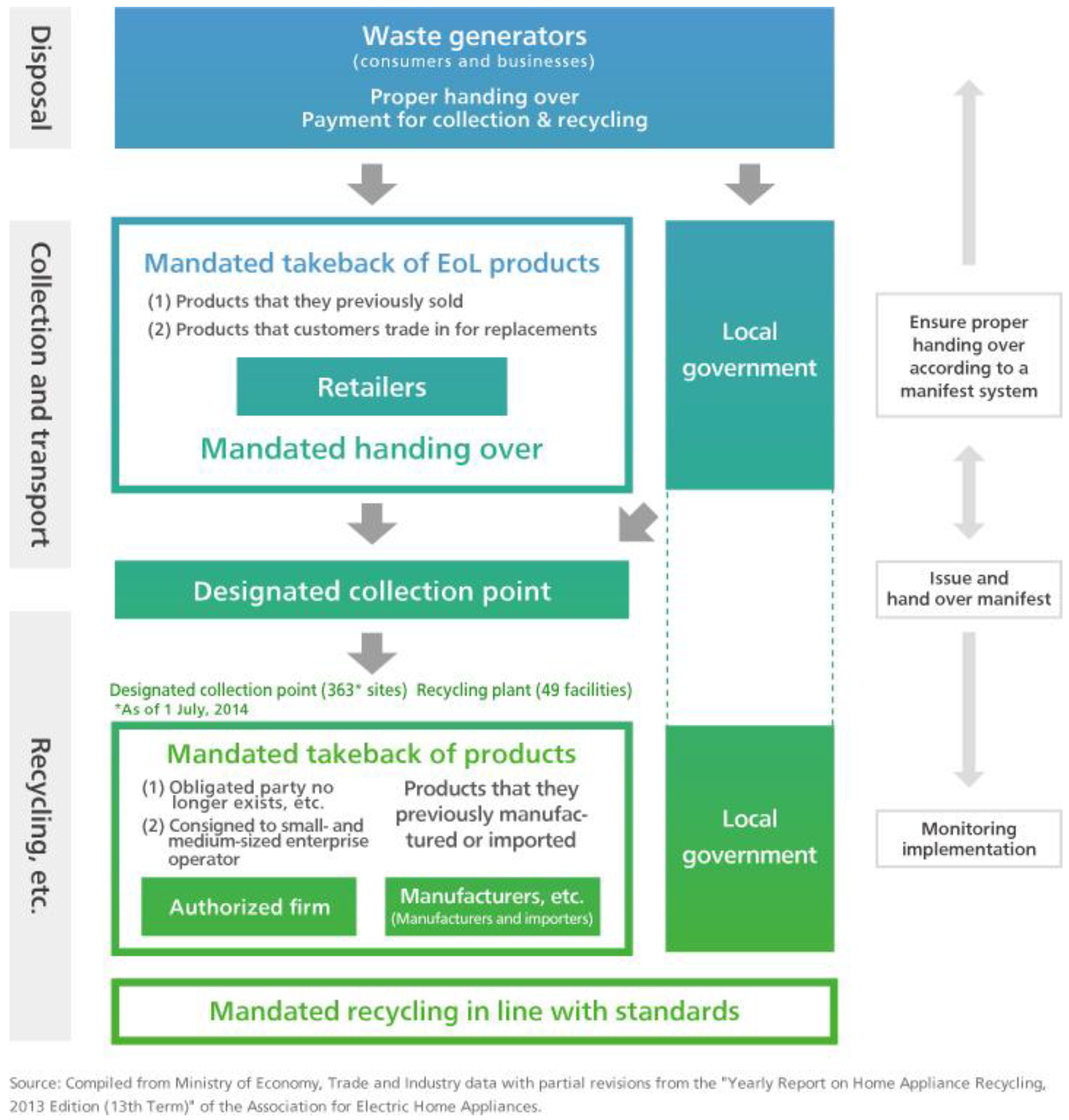

- Hibiki, A. 2024. Recycling Laws and Their Evaluation in Japan. In Introduction to Environmental Economics and Policy in Japan. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, B. R., D. Turnbull, L. Ashworth, and S. McKnight. 2023. Geochemical characteristics and structural setting of lithium–caesium–tantalum pegmatites of the Dorchap Dyke Swarm, northeast Victoria. Australia. Austr. J. Earth Sci. 70: 763–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R. J., Y. Lu, and L. Lu. 2022. Introduction: overview of the global iron ore industry. Iron ore. In Woodhead Publ. Series in Metals and Surface Engineering, 2nd ed. Edited by L. Lu. Elsevier, Woodhead Publishing: pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S., Z.-J. Ma, and J.-B. Sheu. 2019. Optimal prices and trade-in rebates for successive-generation products with strategic consumers and limited trade-in duration. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 124: 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. F., S. L. Chou, and S. L. Lo. 2022. Gold recovery from waste printed circuit boards of mobile phones by using microwave pyrolysis and hydrometallurgical methods. Sustain Environ Res 32: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Q. Ding, Y. Wang, H. Hong, and H. Zhang. 2021. The evolution and influencing factors of international tungsten competition from the industrial chain perspective. Resour. Policy. 73: 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K., J. Li, and Z. Xu. 2010. Characterization and Recycling of Cadmium from Waste Nickel–Cadmium Batteries. Waste Manag 30, 11: 2292–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T., K. Lin, X. Tan, and J. Ruan. 2023. Recovery of Pure Lead and Preparation of Nano-Copper from Waste Glass Diodes via a Clean and Efficient Technology of Step-by-Step Vacuum Evaporation-Condensation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 190: 106799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iattoni, G., E. Vermeersch, C. P. Balde, I. Nnorom, and R. Kuehr. 2021. Regional E-waste monitor for the Arab states 2021. UNU/UNITAR, ITU. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. 2022. The role of critical minerals in clean energy transitions. In World Energy Outlook special report. International Energy Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Illes, A., K. Geeraerts, and J.-P. Schweizer. Illegal Shipment of E-Waste from the EU: A Case Study on Illegal E-Waste Export from the EU to China, 2015.

- ILO. 2014. Tackling informality in e-waste managment: the potential of cooperative enterprises. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M., P. Dias, and N.. Huda. 2020. Waste mobile phones: survey and analysis of the awareness, consumption and disposal behavior of consumers in Australia. Journal of Environmental Management 275: 111111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italimpianti. n.d.Available online: https://www.italimpianti.it/en/catalogue/refining/precious-metals-electrolysis/electrolytic-gold-refining-plant-type-iao-a (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Jabbour, C. J.C., A. Colasante, I. D'Adamo, P. Rosa, and C. Sassanelli. 2023. Comprehending e-waste limited collection and recycling issues in Europe: A comparison of causes. Journal of Cleaner Production 427: 139257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhao, P. R., E. Ahmad, K. K. Pant, and K. D. P. Nigam. 2022. Advancements in the field of electronic waste recycling: critical assessment of chemical route for generation of energy and valuable products coupled with metal recovery. Sep Purif Technol 289: 120773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhao, P. R., E. Ahmad, K. K. Pant, and K. D. P. Nigam. 2022. Advancements in the field of electronic waste recycling: critical assessment of chemical route for generation of energy and valuable products coupled with metal recovery. Sep Purif Technol 289: 120773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangre, J., K. Prasad, and D. Patel. 2022. Analysis of barriers in e-waste management in developing economy: an integrated multiple-criteria decision-making approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29: 72294–72308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X., M. Yang, A. Wan, S. Yu, and Z. Yao. 2022. Bioleaching of Typical Electronic Waste—Printed Circuit Boards (WPCBs): A Short Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19: 7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P., L. Zhang, S. You, Y. Van Fan, R. R. Tan, J. J. Klemes, and F. You. 2023. Blockchain technology applications in waste management: Overview, challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 421: 138466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C., Z. Zhang, and Z. Cheng. 2024. Edited by R. Pandey, A. Pandey, L. Krmicek, C. Cucciniello and D. Müller. Carbonatites and related mineralization: an overview Alkaline Rocks and Their Economic and Geodynamic Significance Through Geological Time. Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, S., R. Kadam, H. Jang, D. Seo, and J. Park. 2024. Recent Advances in Wastewater Electrocoagulation Technologies: Beyond Chemical Coagulation. Energies 17: 5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarlela, T., F. Villagrossi, A. Rastegarpanah, A. San-Miguel-Tello, and T. Pitkäaho. Robotised disassembly of electric vehicle batteries: A systematic literature review. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 74, 2024: 901–921. [CrossRef]

- Kaarlela, T., S. Pieskä, and T. Pitkäaho. 2020. Digital Twin and Virtual Reality for Safety Training. Proceedings of the 2020 11th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Mariehamn, Finland, September 23–25; pp. 000115–000120. [Google Scholar]

- Kafle, A., A. Timilsina, A. Gautam, K. Adhikari, A. Bhattarai, and N. Aryal. 2022. Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. Environ. Adv. 8: 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S. S., and A. Gunasekaran. 2023. Analysing the role of Industry 4.0 technologies and circular economy practices in improving sustainable performance in Indian manufacturing organisations. Prod. Plan. Control 34, 10: 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellos, G., A. Tremouli, P. Tsakiridis, E. Remoundaki, and G. Lyberatos. 2023. Silver recovery from end-of-life photovoltaic panels based on microbial fuel cell technology. Waste BioMass Valorization 15: 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, Q., J. Li, and X. Zeng. 2021. Mapping recyclability of industrial waste for anthropogenic circularity: a circular economy approach. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 9: 11927–11936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, C. L., R. Al Aziz, T. Ahmed, S. M. Misbauddin, and M. A. Moktadir. 2023. Impact of industry 4.0 technologies on sustainable supply chain performance: The mediating role of green supply chain management practices and circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 419: 138249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katepalli, A., Y. Wang, and D. Shi. 2023. Solar harvesting through multiple semi-transparent cadmium telluride solar panels for collective energy generation. Solar Energy 264: 112047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M. 2016. Recovery of metals and nonmetals from electronic waste by physical and chemical recycling processes. Waste Manag 57: 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A., M. A. Rhamdhani, G. Brooks, and S. Masood. 2014. Metal extraction processes for electronic waste and existing industrial routes: a review and Australian perspective. Resources 3, 1: 152–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. A., A. A. Laghari, M. Rashid, H. Li, A. R. Javed, and T. R. Gadekallu. 2023. Artificial intelligence and blockchain technology for secure smart grid and power distribution Automation: A State-of-the-Art Review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 57: 103282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetriwal, D. S., P. Kraeuchi, and R. Widmer. 2009. Producer responsibility for e-waste management: key issues for consideration–learning from the Swiss experience. J Environ Manag 90, 1: 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khonina, S. N., N. L. Kazanskiy, I. V. Oseledets, A. V. Nikonorov, and M. A. Butt. 2024. Synergy between Artificial Intelligence and Hyperspectral Imagining—A Review. Technologies 12: 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianpour, K., A. Jusoh, A. Mardani, D. Streimikiene, F. Cavallaro, K. M. Nor, and et al. 2017. Factors influencing consumers’ intention to return the end of life electronic products through reverse supply chain management for reuse, repair and recycling. Sustainability 9: 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Environmental Industry, and Technology Institute. 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2024, from Keiti.re.kr website. Available online: https://www.keiti.re.kr/site/eng/main.do.

- Koshta, N., S. Patra, and S. P. Singh. 2022. Sharing economic responsibility: assessing end user’s willingness to support E-waste reverse logistics for circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 332: 130057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W., M. Karner, G. Traar, J. Henjes, and W. Sihn. 2018. Digital Twin in Manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 51: 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., and G. Dixit. 2018a. Evaluating critical barriers to implementation of WEEE management using DEMATEL approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 131: 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., H. S. Saini, S. Sengör, R. K. Sani, and S. Kumar. 2021. Bioleaching of Metals from Waste Printed Circuit Boards Using Bacterial Isolates Native to Abandoned Gold Mine. BioMetals 34, 5: 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A. A., I. V. Sanislav, H. E. Cathey, and P. H. Dirks. 2023. Geochemistry of indium in magmatic-hydrothermal tin and sulfide deposits of the Herberton mineral field. Australia. Mineral. Dep. 58: 1297–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubinger, F., A. Brown, P. Börkey, and M. Dubois. 2022. Deposit-refund systems and the interplay with additional mandatory extended producer responsibility policies. Environment Working Paper No. 208, OECD ENV/WKP 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, S. H., and M. G. Badami. 2020. Extended producer responsibility for E-waste management: policy drivers and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 251: 119657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B. 2021. Formation of tin ore deposits: a reassessment. Lithos 403: 105756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., W. Qin, J. Li, Z. Tian, F. Jiao, and C. Yang. 2021. Tracing the global tin flow network: highly concentrated production and consumption. Res., Conserv., Recycl. 169: 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., H. Zhang, X. Zhou, and W. Zhong. 2022. Research on the evolution of the global import and export competition network of chromium resources from the perspective of the whole industrial chain. Resour. Policy. 79: 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G., Y. Mo, and Q. Zhou. 2010. Novel Strategies of Bioleaching Metals from Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs) in Mixed Cultivation of Two Acidophiles. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 47, 7: 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., J. Mao, W. Chen, and L. Shi. 2019. Indium in mainland China: insights into use, trade, and efficiency from the substance flow analysis. Resources, Conserv., Recycl. 149: 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. W., T. M. Cheng, Y. J. Chen, K. C. Yueh, S. Y. Tang, K. Wang, and et al. 2022. High-yield recycling and recovery of copper, indium, and gallium from waste copper indium gallium selenide thin-film solar panels. Solar Energy Material. Solar Cells 241: 111691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., S. Huang, Y. Jin, L. Ma, W.-X. Wang, and J. C.-H. Lam. 2022. A Green Slurry Electrolysis to Recover Valuable Metals from Waste Printed Circuit Board (WPCB) in Recyclable pH-Neutral Ethylene Glycol. J. Hazard. Mater. 433: 128702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K., Q. Tan, J. Yu, and M. Wang. 2023. A global perspective on e-waste recycling. Circ. Econ. 2, 1: 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., L. Zhang, S. Jiang, Z. Yuan, and J. Chen. 2023a. Global copper cycles in the anthroposphere since the 1960s. Resources, Conserv., Recycl. 199: 107294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., S. Fang, H. Dong, and C. Xu. 2021. Review of Digital Twin about Concepts, Technologies, and Industrial Applications. J. Manuf. Syst. 58: 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Y. Geng, Z. Gao, J. Li, and S. Xiao. 2023b. Uncovering the key features of gold flows and stocks in China. Resour. Policy. 82: 103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofthouse, V., and S. Prendeville. 2017. Edited by C. Bakker and R. Mugge. Considering the user in the circular economy. In PLATE (Product Lifetimes and the Environment) Conference Proceedings. IOS Press: Amsterdam: pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y., B. Yang, Y. Gao, and Z. Xu. 2022. An automatic sorting system for electronic components detached from waste printed circuit boards. Waste Manag 137: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukomska, A., A. Wisniewska, Z. Dabrowski, J. Lach, K. Wrobel, D. Kolasa, and U. Domanska. 2022. Recovery of Metals from Electronic Waste-Printed Circuit Boards by Ionic Liquids, DESs and Organophosphorous-Based Acid Extraction. Molecules 27, 15: 4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T., H. Chen, and Y. L. Guo. 2023. Investigating innovation diffusion, social influence, and personal inner forces to understand people’s participation in online e-waste recycling. J Retail Consum Serv 73: 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, T., Y. Wang, and Y. B. Hahn. 2018. Graphene and its derivatives for solar cells application. Nano Energy 47: 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyapour, H., and S. Mohammadnejad. 2022. Optimization of the operating parameters in gold electro-refining. Minerals Engineering 186: 107738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldybayev, G., A. Karabayev, R. Sharipov, K. M. Azzam, E. S. Negim, O. Baigenzhenov, A. Alimzhanova, M. Panigrahi, and R. Shayakhmetova. 2024. Processing of titanium-containing ores for the production of titanium products: a comprehensive review. Heliyon 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masud, M. H., M. Mourshed, M. Mahjabeen, A. A. Ananno, and P. Dabnichki. 2022. Global electronic waste management: current status and way forward. In Paradigm Shift in E-waste Management. pp. 9–47. [Google Scholar]

- Meixner, A., R. N. Alonso, F. Lucassen, L. Korte, and S. A. Kasemann. 2022. Lithium and Sr isotopic composition of salar deposits in the Central Andes across space and time: the Salar de Pozuelos. Argentina. Mineral. Dep. 57: 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, G., A. Becci, and A. Amato. 2022. Recovery of Precious Metals from Printed Circuit Boards by Cyanogenic Bacteria: Optimization of Cyanide Production by Statistical Analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 3: 107495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, J. A., I. Esparragoza, and H. Maury. 2018. Development of a metric to assess the complexity of assembly/disassembly tasks in open architecture products. Int. J. Prod. Res. 56: 7201–7219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- METI related Laws. 2023. METI. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/english/information/data/la (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Michael, L. K., S. S. Hungund, and S. K. V. 2024. Factors influencing the behavior in recycling of e-waste using integrated TPB and NAM model. Cogent Business & Management 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A. K. 2021. AI4R2R (AI for rock to revenue): a review of the applications of AI in mineral processing. Minerals 11, 10: 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D., and Y. Rhee. 2010. Current Research Trends of Microbiological Leaching for Metal Recovery from Industrial Wastes. Curr. Res. Technol. Edu. Top. Appl. Microbiol. Microb. Biotechnol. 2: 1289–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A. M.O. 2024a. Nexuses of critical minerals recovery from e-waste. Academia Environmental Sciences and Sustainability 1: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A. M.O. 2024b. “Sustainable recovery of silver nanoparticles from electronic waste: Applications and safety concerns. Review Article. Academia Engineering 1, 3: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A. M.O., E. K. Paleologos, D. Mohamed, A. Fayad, and M. T. Al Nahyan. 2025. Critical Minerals Mining: A Path Toward Sustainable Resource Extraction and Aquatic Conservation. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M., S. Rovetta, F. Masulli, and A. Cabri. 2025. Automated Disassembly of Waste Printed Circuit Boards: The Role of Edge Computing and IoT. Computers 14, 2: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M., S. Rovetta, F. Masulli, and A. Cabri. 2024. Real-Time Detection of Electronic Components in Waste Printed Circuit Boards: A Transformer-Based Approach, Torino, Italy. arXiv arXiv:2409.16496. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin, M., X. Zeng, S. Rovetta, and F. Masulli. 2024a. Measuring the Recyclability of Electronic Components to Assist Automatic Disassembly and Sorting Waste Printed Circuit Boards. arXiv arXiv:2406.16593. [Google Scholar]

- Mokarian, P., I. Bakhshayeshi, F. Taghikhah, Y. Boroumand, E. Erfani, and A. Razmjou. 2022. The advanced design of bioleaching process for metal recovery: A machine learning approach. Sep. Purif. Technol. 291: 120919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moossa, B., H. Qiblawey, M. S. Nasser, M. A. Al-Ghouti, and A. Benamor. 2023. Electronic waste considerations in the Middle East and North African (MENA) region: a review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 29: 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D., D. I. Groves, and M. Santosh. 2024. Metallic Mineral Resources: The Critical Components for a Sustainable Earth. University of Western Australia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D., D. I. Groves, M. Santosh, and C.-X. Yang. 2025. Critical metals: Their applications with emphasis on the clean energy transition. Geosystems and Geoenvironment 4, 1: 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, A., Z. Zhang, A. E. Shine, M. L. Free, and P. K. Sarswat. 2022. E-wastes derived sustainable Cu recovery using solvent extraction and electrowinning followed by thiosulfate-based gold and silver extraction. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances Volume 8: 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V., and S. Ramakrishna. 2022. A review on global E-waste management: urban mining towards a sustainable future and circular economy. Sustainability 14: 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajan, P., A. Vafaei-Zadeh, H. Hanifah, and R. Thurasamay. 2023. Sustaining the environment through e-waste recycling: an extended valence theory perspective. Aslib J Inf Manag. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T., and K. Halada. 2015. Urban Mining Systems. In Springer Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, T., J. Yang, R. Aromaa-Stubb, Q. Zhu, and M. Lundström. 2024. Process simulation and life cycle assessment of hydrometallurgical recycling routes of waste printed circuit boards. J Clean Prod 435: 140458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanath, K., and S. A. Kumar. 2021. The role of communication medium in increasing e-waste recycling awareness among higher educational institutions. Int J Sustain High Educ 22: 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjo, M. 1987. Urban mine, Bulletin of the Research Institute for Mineral Dressing and Metallurgy at Tohoku University. Tohoku University: pp. 239–241. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanasamy, M., D. Dhanasekaran, and N. Thajuddin. 2022. Frankia Consortium Extracts High-Value Metals from eWaste. Environ. Technol. Innovat. 28: 102564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, N. T., H. Kim, M. Frenzel, M. S. Moats, and S. M. Hayes. 2022. Global tellurium supply potential from electrolytic copper refining. Resources, Conservation, Recycling 184: 106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveenkumar, R., J. Iyyappan, R. Pravin, S. Kadry, J. Han, R. Sindhu, and G. Baskar. 2023. A strategic review on sustainable approaches in municipal solid waste management and energy recovery: Role of artificial intelligence, economic stability and life cycle assessment. Bioresour. Technol., 129044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazlı, T. 2021. Repair motivation and barriers model: investigating user perspectives related to product repair towards a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduneseokwu, C. K., Y. Qu, and A.. Appolloni. 2017. Factors influencing consumers’ intentions to participate in a formal e-waste collection system: case study of Onitsha, Nigeria. Sustainability 9, 6: 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K. S., I. Head, G. C. Premier, K. Scott, E. Yu, J. Lloyd, and J. Sadhukhan. 2016. A multilevel sustainability analysis of zinc recovery from wastes. Resources, Conservation, Recycling 113: 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nili, S., M. Arshadi, and S. Yaghmaei. 2022. Fungal Bioleaching of E-Waste Utilizing Molasses as the Carbon Source in a Bubble Column Bioreactor. J. Environ. Manage. 307: 114524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nithya, R., C. Sivasankari, and A. Thirunavukkarasu. 2021. Electronic waste generation, regulation and metal recovery: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19: 1347–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnorom, I. C., J. Ohakwe, and O. Osibanjo. 2009. Survey of willingness of residents to participate in electronic waste recycling in Nigeria–case study of mobile phone recycling. Journal of Cleaner Production 17, 18: 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, A. A., U. H. Akter, T. H. Pranto, and A. K.M.B. Haque. 2022. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Circular Economy: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Review. Ann. Emerg. Technol. Comput. 6, 2: 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose, K., and T. H. Okabe. 2024. Platinum group metals production, 2nd ed. Treatise Process Metallurgy: Vol. 3, pp. 751–770. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, P., and T. Pamuła. 2020. Application of deep learning object classifier to improve e-waste collection planning. Waste Manag 109: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2016. Extended Producer Responsibility: Updated Guidance for Efficient Waste Management. OECD Publishing: Paris. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outteridge, T., N. Kinsman, G. Ronchi, and H. Mohrbacher. 2020. Industrial relevance of molybdenum in China. Advances Manufact 8: 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturkcan, S. 2024. The right-to-repair movement: Sustainability and consumer rights. Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases 14, 2: 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, M. M., V. R. Myneni, B. Gudeta, and S. Komarabathina. 2022. Toxic metal recovery from waste printed circuit boards: a review of advanced approaches for sustainable treatment methodology. Adv Mater Sci Eng 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleologos, E. K., A. M.O. Mohamed, D. N. Singh, B. C. O’Kelly, M. El Gamal, a. Mohammad, p. Singh, V. S.N. Goli, A. J. S Roque, J. A. Oke, H. Abuel-Naga, and E.-C. Leong. 2024. Sustainability Challenges of Critical Minerals for Clean Energy Technologies: Copper and Rare Earths. Environmental Geotechnics J. Published Online: February 02, 2024. , 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., C. W. Y. Wong, and C. Li. 2022. Circular economy practices in the waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) industry: a systematic review and future research agendas. J Clean Prod 365: 132671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S., A. Akcil, N. Pradhan, and H. Deveci. 2015. Current Scenario of Chalcopyrite Bioleaching: A Review on the Recent Advances to Its Heap-Leach Technology. Bioresour. Technol. 196: 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R., L. Krmíček, D. Müller, A. Pandey, and C. Cucciniello. 2024. Alkaline rocks: their economic and geodynamic significance through geological time. Edited by R. Pandey, A. Pandey, L. Krmicek, C. Cucciniello and D. Müller. Alkaline Rocks and Their Economic and Geodynamic Significance Through Geological Time. Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ.: vol. 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, D., D. Joshi, M. K. Upreti, and R. K. Kotnala. 2012. Chemical and biological extraction of metals present in E waste: a hybrid technology. Waste Manage 32: 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J., C. Ahn, K. Lee, W. Choi, H. Song, S. O. Choi, and S. W. Han. 2019. Analysis on public perception, user-satisfaction, and publicity for WEEE collecting system in South Korea: case study for door-to-door service. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 144: 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S., S. Yunfei, J. Khan, U. Haq, and S. Ruinan. 2019. E-waste generation and awareness on managing disposal practices at Delhi National Capital Region in India [Paper presentation]. 2019 16th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Active Media Technology and Information Processing; IEEE, December, pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, R. A., and S. Ramakrishna. 2020. A Comprehensive Analysis of E-Waste Legislation Worldwide. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 13: 14412–14431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Belis, V., M. Braulio-Gonzalo, P. Juan, and M. D. Bovea. 2017. Consumer attitude towards the repair and the second-hand purchase of small household electrical and electronic equipment. A Spanish case study. J. Clean. Prod. 158: 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DataScience PETRA. 2018. World’s First Digital Twin for Mine Value Chain Optimisation. PETRA DataScience. Available online: http://www.petradatascience.com/casestudy/worlds-first-digital-twin-for-mine-value-chain-optimisation/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Petranikova, M., A. H. Tkaczyk, A. Bartl, A. Amato, V. Lapkovskis, and C. Tunsu. 2020. Vanadium sustainability in the context of innovative recycling and sourcing development. Waste Management 113: 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, D. E. 2019. Vanadium. Available online: https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/vanadium/mcs-2019-vanad.pdf.

- Porter, J. 2022. Google joins Samsung in working with iFixit on a self-repair program [Online]. The Verge. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2022/4/8/23016233/google-pixelsmartphones-ifixit-repair-program (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Portmet. 2023. How biggest tech companies promote e-waste recycling? Available online: https://portmet.pt/en/how-biggest-tech-companies-promote-e-waste-recycling/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Praveena, B. A., N. Lokesh, A. Buradi, N. Santhosh, B. L. Praveena, and R. Vignesh. 2022. A comprehensive review of emerging additive manufacturing (3D printing technology): Methods, materials, applications, challenges, trends and future potential. Mater. Today. Proc. 52: 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisler, Z., R. Andolina, A. Busacca, C. Caliri1, C. Miliani, and F. P. Romano. 2024. Deep learning for enhanced spectral analysis of MA-XRF datasets of paintings. Science Advances: vol. 10, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Priyashantha, A. K. H., N. Pratheesh, and P. Pretheeba. 2022. E-waste scenario in South-Asia: an emerging risk to environment and public health. Environ. Anal. Health Toxicol. 37, 3: e2022022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X., J. Fang, J. Xia, G. He, and H. Chen. 2023. Recent progress and perspective on molybdenum-based electrocatalysts for water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48: 26084–26106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, P., S. Ghassa, F. Moosakazemi, R. Khosravi, and H. Siavoshi. 2021. Recovery of a Critical Metal from Electronic Wastes: Germanium Extraction with Organic Acid. J. Clean. Prod. 315: 128223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramprasad, C., W. Gwenzi, N. Chaukura, N. Izyan Wan Azelee, A. Upamali Rajapaksha, M. Naushad, and et al. 2022. Strategies and options for the sustainable recovery of rare earth elements from electrical and electronic waste. Chem Eng J 442: 135992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, W., and L. Zhang. 2023. Bridging the intention-behavior gap in mobile phone recycling in China: the effect of consumers’ price sensitivity and proactive personality. Environ Dev Sustain 25: 938–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapuc, W., J. Kévin, D. Anne-Lise, S. Pierre, S. Pierre, S. Pierre, S. Pierre, S. Pierre, S. Pierre, S. Pierre, and S. Pierre. 2020. XRF and hyperspectral analyses as an automatic way to detect flood events in sediment cores. Sedimentary Geology Volume 409: 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasnan, M. I., A. F. Mohamed, C. T. Goh, and K. Watanabe. 2016. Sustainable e-waste management in Asia: analysis of practices in Japan, Taiwan and Malaysia. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manage. 18, 04: 1650023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegarpanah, A., H. C. Gonzalez, and R. Stolkin. 2021. Semi-autonomous behaviour treebased framework for sorting electric vehicle batteries components. Robotics 10, 2. Available online: https://www. mdpi.com/2218-6581/10/2/82. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S., L. Verma, and J. Singh. 2020. Environmental hazards and management of E-waste. Environmental concerns and sustainable development. Amsterdam: Springer, 381–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, D. A., M. Baniasadi, J. E. Graves, A. Greenwood, and S. Farnaud. 2022. Thiourea Leaching: An Update on a Sustainable Approach for Gold Recovery from E-Waste. J. Sustain. Metall. 8, 2: 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rene, E. R., M. Sethurajan, V. K. Ponnusamy, G. Kumar, T. N. B. Dung, K. Brindhadevi, and et al. 2021. Electronic waste generation, recycling and resource recovery: technological perspectives and trends. J Hazard Mater 416: 125664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoldi, A., E. F. Trogu, G. C. Marcheselli, F. Artizzu, N. Picone, M. Colledani, P. Deplano, and A. Serpe. 2019. Advances in Recovering Noble Metals from Waste Printed Circuit Boards (WPCBs). ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 1: 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E., S. Di Piazza, G. Cecchi, M. Mazzoccoli, M. Zerbini, A. M. Cardinale, and M. Zotti. 2022. Applied Tests to Select the Most Suitable Fungal Strain for the Recovery of Critical Raw Materials from Electronic Waste Powder. Recycling 7, 5: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R., G. Von Wichert, G. Lo, and K. D. Bettenhausen. 2015. About the Importance of Autonomy and Digital Twins for the Future of Manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 48: 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostek, L., E. Pirard, and A. Loibl. 2023. The future availability of zinc: potential contributions from recycling and necessary ones from mining. Resources, Conserv., Recycl. Adv. 19: 200166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saphores, J. D. M., H. Nixon, O. Ogunseitan, and A. A. Shapiro. 2006. Household willingness to recycle electronic waste: An application to California. Environment and Behavior 38, 2: 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinova, E., C. Evans, E. Lebre, M. Stringer, M. Azadi, and R. K. Valenta. 2023. Will global cobalt supply meet demand? The geological, mineral processing, production and geographic risk profile of cobalt. Resources, Conservation, Recycling 190: 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayfayn, N. 2018. Sustainable Development in Saudi Arabia, Past, Present and Future. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Schischke, K., M. Proske, N. F. Nissen, and M. Schneider-Ramelow. 2019. Impact of modularity as a circular design strategy on materials use for smart mobile devices. MRS Energy Sustain 6: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, K. A., and L. Agbemabiese. 2021. E-Waste Legislation in the US: An Analysis of the Disparate Design and Resulting Inuence on Collection Rates across States. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 64, 6: 1067–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEGH. 2024. Sustainable cross-border e-waste management. Available online: https://segh.net/f/one-to-watch-sustainable-cross-border-e-waste-management (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Serpe, A., G. G. De, A. Muntoni, F. Asunis, D. Spiga, A. A. Oumarou, S. Trudu, and M. Cera. 2023. Process for Production of a Leaching Mixture Starting from Dairy Waste Products, WO2023199263A1. [Google Scholar]

- Serpe, A., D. Purchase, L. Bisschop, D. Chatterjee, G. De Gioannis, H. Garelick, A. Kumar, W. J.G.M. Peijnenburg, V. M.I. Piro, M. Cera, Y. Shevahi, and S. Verbeek. 2024. 2002–2022: 20 years of e-waste regulation in the European Union and the worldwide trends in legislation and innovation technologies for a circular economy. RSC Sustainability. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpe, A., A. Rigoldi, C. Marras, F. Artizzu, M. L. Mercuri, and P. Deplano. 2015. Chameleon Behaviour of Iodine in Recovering Noble-Metals from WEEE: Towards Sustainability and “Zero” Waste. Green Chem 17, 4: 2208–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin, M., M. Nur Uddin, J. I. Chowdhury, S. F. Ahmed, M. N. Uddin, M. Mofijur, and et al. 2023. A review of the recent development, challenges, and opportunities of electronic waste (e-waste). Int J Environ Sci Technol 20: 4513–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharudin, M. R., R. Said, C. Hotrawaisaya, N. R. Nik bdul Rashid, and F. S. Azman Perwira. 2020. Linking determinants of the youth’s intentions to dispose of portable e-waste with the proper disposal behavior in Malaysia. The Social Science Journal 60, 4: 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H., N. Rawal, and B. Mathew. 2015. The characteristics, toxicity and effects of cadmium. Int. J. Nanotech. Nanosci. 3: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H., and H. Kumar. 2024. A computer vision-based system for real-time component identification from waste printed circuit boards. J. Environ. Manag. 351: 119779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, O. S., I. D. Williams, and P. J. Shaw. 2021. Global E-Waste Management: Can WEEE Make a Difference? A Review of e-Waste Trends, Legislation, Contemporary Issues and Future Challenges. Waste Manag 120: 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A., F. Pahlevani, K. Levick, I. Cole, and V. Sahajwalla. 2017. Synthesis of copper-tin nanoparticles from old computer printed circuit boards. J Clean Prod 142: 2586–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidique, S. F., F. Lupi, and S. V. Joshi. 2010. The effects of behavior and attitudes on drop-off recycling activities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 54, 3: 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., R. Srivastava, E. Fuenmayor, V. Kuts, Y. Qiao, N. Murray, and D. Devine. 2022. Applications of Digital Twin across Industries: A Review. Appl. Sci. 12: 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonego, M., M. E.S. Echeveste, and H. Galvan Debarba. 2018. The role of modularity in sustainable design: a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 176: 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sronsri, C., W. Sittipol, N. Panitantum, and K. U-yen. 2021. Optimization of Elemental Recovery from Electronic Wastes Using a Mild Oxidizer. Waste Manag 135: 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Step. 2014. Solving the E-Waste Problem (Step) White Paper. Recommendations for Standards Development for Collection, Storage, Transport and Treatment of E-waste. Available online: https://www.step-initiative.org/files/_documents/whitepapers/StEP_WP_Standard_20140602.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Step. 2020. Case Studies and approaches to building partnerships between the informal and the formal sector for sustainable e-waste management. Available online: https://www.step-initiative.org/files/_documents/publications/Partnerships-between-the-informal-and-the-formal-sector-for-sustainable-e-waste-management.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Sun, X., H. Hao, Z. Liu, and F. Zhao. 2020. Insights into the global flow pattern of manganese. Resour. Policy. 65: 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. 2023. The use of aluminum alloys in structures: review and outlook. Structures 57: Article 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., Y. Xiao, J. Sietsma, H. Agterhuis, and Y. Yang. 2015. A Cleaner Process for Selective Recovery of Valuable Metals from Electronic Waste of Complex Mixtures of End-of-Life Electronic Products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 13: 7981–7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabelin, C. B., I. Park, T. Phengsaart, S. Jeon, M. Villacorte-Tabelin, D. Alonzo, and et al. 2021. Copper and critical metals production from porphyry ores and e-wastes: a review of resource availability, processing/recycling challenges, socio-environmental aspects, and sustainability issues. Resour Conserv Recycl 170: 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., H. Xie, B. Zhang, X. Chen, Z. Zhao, J. Qu, P. Xing, and H. Yin. 2019. Recovery and Regeneration of LiCoO2-Based Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries by a Carbothermic Reduction Vacuum Pyrolysis Approach: Controlling the Recovery of CoO or Co. Waste Manag 97: 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, F., J. Cheng, Q. Qi, M. Zhang, H. Zhang, and F. Sui. 2018. Digital Twin-driven Product Design, Manufacturing and Service with Big Data. In Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. CrossRef: vol. 94, pp. 3563–3576. [Google Scholar]

- Tari, A., and R. Trudel. 2024. Why You Should Offer a Take-Back Program for Your Old Products. Environmental sustainability. Available online: https://hbr.org/2024/02/why-you-should-offer-a-take-back-program-for-your-old-products (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Tasker, P. A., J. A. McCleverty, P. G. Plieger, T. J. Meyer, and L. C. West. 2004. 9.17 Metal Complexes for Hydrometallurgy and Extraction. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II. Elsevier: vol. 9, pp. 759–807. [Google Scholar]

- Tatariants, M., S. Yousef, S. Sakalauskaitė, R. Daugelavičius, G. Denafas, and G. Bendikiene. 2018. Antimicrobial copper nanoparticles synthesized from waste printed circuit boards using advanced chemical technology. Waste Manag 78: 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, S. C., N. S. Nayak, D. R. Tipre, and S. R. Dave. 2022. Multi-Metal Mining from Waste Cell Phone Printed Circuit Boards Using Lixiviant Produced by a Consortium of Acidophilic Iron Oxidizers. Environ. Eng. Sci. 39, 3: 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P., and S. Kumar. 2021. Pretreatment of Low-Grade Shredded Dust e-Waste to Enhance Silver Recovery through Biocyanidation by Pseudomonas Balearica SAE1. 3 Biotech 11, 11: 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaseen Ikram, S., V. Mohanraj, S. Ramachandran, and A. Balakrishnan. 2023. An Intelligent Waste Management Application Using IoT and a Genetic Algorithm–Fuzzy Inference System. Appl. Sci. 13: 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Apple International Community School Thi Thu Nguyen. 2023. E-waste collection drive-join us and make a difference! Available online: https://applecommunityschool.ae/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/circular-27-E-waste-collection-drive.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Thi Thu Nguyen, H., R. J. Hung, and C. H. Lee. 2019. Determinants of residents’-waste recycling behavioral intention: case study from Vietnam. Sustainability 11, 1: 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thukral, S., D. Shree, and S. Singhal. 2023. Consumer behavior towards storage, disposal and recycling of e-waste: systematic review and future research prospects. Benchmarking Int. J. 30: 1021–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S. K., S. Sahoo, N. Wang, and A. Huczko. 2020. Graphene research and their outputs: status and prospect. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 5: 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M., P. S. Phillips, and A. D. Read. 2004. Using the theory of planned behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: case study from Brixworth, UK. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 41, 3: 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombino, S., R. Sole, M. L. Di Gioia, D. Procopio, F. Curcio, and R. Cassano. 2023. Green Chemistry Principles for Nano-and Micro-Sized Hydrogel Synthesis. Molecules 28: 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunsu, C., M. Petranikova, M. Gergoric, C. Ekberg, and T. Retegan. 2015. Reclaiming rare earth elements from end-of-life products: a review of the perspectives for urban mining using hydrometallurgical unit operations. Hydrometallurgy 156: 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/hwgenerators/new-international-requirements-electrical-and-electronic-waste (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- U.S. EPA. n.d.Available online: https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/cleaning-electronic-waste-e-waste.

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries. 2023. Indium, 88–89. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/mineral-commodity-summaries.

- UNEMG-Environment Management Group. 2019. A New Circular Vision for Electronics: Time for a Global Reboot. World Economic Forum (WEF): Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_A_New_Circular_Vision_for_Electronics.pdf.

- UNEP. 2023. Sustainable Future of E-waste. Available online: https://www.unep.org/ietc/news/story/sustainable-future-e-waste (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Valera, E. H., R. Cremades, E. van Leeuwen, and A. van Timmeren. 2023. Additive manufacturing in cities: Closing circular resource loops. Circ. Econ., 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, S., R. Kleijn, B. Sprecher, and A. Tukker. 2020. Identifying supply risks by mapping the cobalt supply chain. Resources, Conservation, Recycling 156: 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, A. Z., and M. Aurisicchio. 2019. Archetypical consumer roles in closing the loops of resource flows for Fast-Moving Consumer Goods. J. Clean. Prod. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yken, J., K. Y. Cheng, N. J. Boxall, A. N. Nikoloski, N. Moheimani, M. Valix, and A. H. Kaksonen. 2023. An Integrated Bio-hydrometallurgical Approach for the Extraction of Base Metals from Printed Circuit Boards. Hydrometallurgy 216: 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglio, F., and I. Birloaga. 2018. Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Recycling: Aqueous Recovery Methods. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials. Woodhead Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Villares, M., A. Işıldar, A. M. Beltran, and J. Guinee. 2016. Applying an exante life cycle perspective to metal recovery from e-waste using bioleaching. J Clean Prod 129: 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S., S. Das, and Y. P. Ting. 2020. Predictive modeling and response analysis of spent catalyst bioleaching using artificial neural network. Bioresour Technol Rep 9: 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Y. Liang, Y. Zeng, C. Liu, C. Zhan, P. Chen, S. Song, and F. Jia. 2024. Highly Selective Recovery of Gold and Silver from E-Waste via Stepwise Electrodeposition Directly from the Pregnant Leaching Solution Enabled by the MoS2 Cathode. J. Hazard. Mater. 465: 133430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J., J. Guo, and Z. Xu. 2016. An environmentally friendly technology of disassembling electronic components from waste printed circuit boards. Waste Manag 53: 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., A. Wang, W. Zhong, D. Zhu, and C. Wang. 2022. Analysis of international nickel flow based on the industrial chain. Resour. Policy. 77: 102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., D. Guo, X. Wang, B. Zhang, and B. Wang. 2018. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resources. Conservation and Recycling 133: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, K., W. H. Chen, F. Dietrich, K. Dröder, and S. Kara. 2015. Robot assisted disassembly for the recycling of electric vehicle batteries. Proc CIRP, vol. 29, pp. 716–721. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212827115000931. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., K. Qiu, X. Diao, J. Ma, H. Yu, M. An, C. Zhi, L. Krmicek, and J. Deng. 2024. Edited by R. Pandey, A. Pandey, L. Krmicek, C. Cucciniello and D. Müller. The giant Baerzhe REE-Nb-Zr-Be deposit, Inner Mongolia, China, an Early Cretaceous analogue of the Strange Lake rare-metal deposit, Quebec. Alkaline Rocks and Their Economic and Geodynamic Significance Through Geological Time. Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ.: vol. 551. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X., X. Li, J. Bian, and C. Yang. 2023. Deposit or reward: Express packaging recycling for online retailing platforms. Omega 117: 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J., J. Li, and Z. Xu. 2017. Novel Approach for in Situ Recovery of Lithium Carbonate from Spent Lithium Ion Batteries Using Vacuum Metallurgy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 20: 11960–11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M., and F.-S. Zhang. 2011. Nano-Lead Particle Synthesis from Waste Cathode Ray-Tube Funnel Glass. J. Hazard. Mater. 194: 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, F., and F. Zhang. 2009. Preparation of nano-Cu2O/TiO2 photocatalyst from waste printed circuit boards by electrokinetic process. J Hazard Mater 172: 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, F. R., H. Weng, Y. Qi, G. Yu, Z. Zhang, F. Zhang, and et al. 2017. A novel recovery method of copper from waste printed circuit boards by supercritical methanol process: preparation of ultrafine copper materials. Waste Manag 60: 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R., J. Peng, P. Zhang, C. Guo, X. Jiang, S. Lu, Y. Kang, Q. Xu, Z. Li, and Y. Wei. 2023. Plasma heavy metals and coagulation levels of residents in E-waste recycling areas. Environ. Technol. Innov. 32: 103379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaashikaa, P. R., B. Priyanka, P. Senthil Kumar, S. Karishma, and S. I. Jeevanantham. 2022. A review on recent advancements in recovery of valuable and toxic metals from e-waste using bioleaching approach. Chemosphere 287: 132230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R., D. Kumar Panda, and S. Kumar. 2022. Understanding the individuals’ motivators and barriers of e-waste recycling: a mixed-method approach. J. Environ. Manag. 324: 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubchuk, A. 2023. Russian gold mining: 1991 to 2021, & beyond. Ore Geol. Rev. 153: 105287. [Google Scholar]