Submitted:

02 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

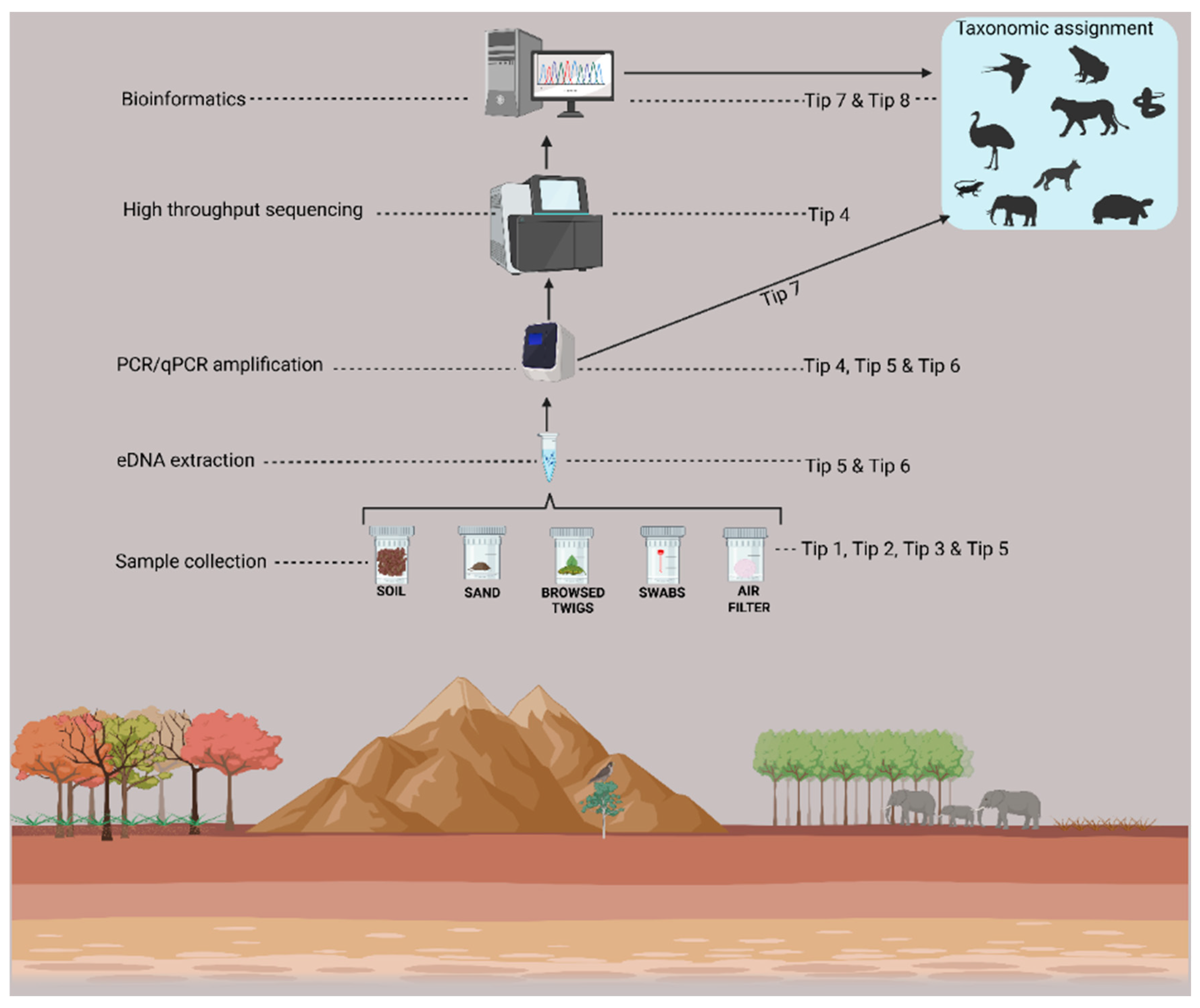

Tip 1: Select the Sampling Substrate Carefully.

Tip 2: Sample Size Matters

Tip 3: Choose the Sample Preservation Method Thoughtfully.

Tip 4: Determine the Analytical Approaches with Care.

Tip 5: Be Mindful of Contamination.

Tip 6: Strategize on How to Handle Inhibition.

Tip 7: Build a Custom Reference Database.

Tip 8: Interpret the Sequence Read Counts Wisely.

2. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

References

- Adams, C. I. M., Knapp, M., Gemmell, N. J., Jeunen, G., Bunce, M., Lamare, M. D., & Taylor, H. R. (2019). Beyond Biodiversity : Can Environmental DNA ( eDNA ) Cut It as a Population Genetics Tool ? Genes. [CrossRef]

- Amador, J., Milne, P. J., Moore, C. A., & Zika, R. G. (1990). Extraction of chromophoric humic substances from seawater. Marine Chemistry, 29(C), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Andres, K. J., Lodge, D. M., Sethi, S. A., & Andrés, J. (2023). Detecting and analysing intraspecific genetic variation with eDNA : From population genetics to species abundance. April, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ariza, M., Fouks, B., Mauvisseau, Q., Halvorsen, R., Alsos, I. G., & de Boer, H. J. (2023). Plant biodiversity assessment through soil eDNA reflects temporal and local diversity. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 14(2), 415–430. [CrossRef]

- Aucone, E., Kirchgeorg, S., Valentini, A., Pellissier, L., Deiner, K., & Mintchev, S. (2023). Drone-assisted collection of environmental DNA from tree branches for biodiversity monitoring. 5762(January), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bairoliya, S., Zhi Xiang, J. K., & Cao, B. (2022). Extracellular DNA in Environmental Samples: Occurrence, Extraction, Quantification, and Impact on Microbial Biodiversity Assessment. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 88(3), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Berry, O., Jarman, S., Bissett, A., Hope, M., Paeper, C., Bessey, C., Schwartz, M. K., Hale, J., & Bunce, M. (2021). Making environmental DNA ( eDNA ) biodiversity records globally accessible. July 2020, 699–705. [CrossRef]

- Bessey, C., Gao, Y., Bach, Y., Haylea, T., Jarman, S. N., & Berry, O. (2022). Comparison of materials for rapid passive collection of environmental DNA. November 2021, 2559–2572. [CrossRef]

- Bongaarts, J. (2019). IPBES, 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In Population and Development Review (Vol. 45, Issue 3). [CrossRef]

- Boussarie, G., Bakker, J., Wangensteen, O. S., Mariani, S., Bonnin, L., Juhel, J., Kiszka, J. J., Kulbicki, M., Manel, S., Robbins, W. D., Vigliola, L., & Mouillot, D. (2018). Environmental DNA illuminates the dark diversity of sharks. May.

- Boyer, F., Mercier, C., Bonin, A., Le Bras, Y., Taberlet, P., & Coissac, E. (2016). obitools: inspired software package for DNA metabarcoding. Molecular Ecology Resources, 16(1), 176–182. [CrossRef]

- Bracken, F. S. A., Carlsson, J., Rooney, S. M., Kelly, M., & James, Q. (2019). Identifying spawning sites and other critical habitat in lotic systems using eDNA “ snapshots ”: A case study using the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus L . November 2018, 553–567. [CrossRef]

- Brauwer, M. De, Clarke, L. J., Chariton, A., Cooper, M. K., Bruyn, M. De, Furlan, E., Macdonald, A. J., Rourke, M. L., Sherman, C. D. H., Suter, L., Rath, C. V.-, Zaiko, A., & Trujillo-, A. (2023). Best practice guidelines for environmental DNA biomonitoring in Australia and New Zealand. August 2022, 417–423. [CrossRef]

- Bruce, K., Blackman, R. C., Bourlat, S. J., Hellström, M., Bakker, J., Bista, I., Bohmann, K., Bouchez, A., Brys, R., Clark, K., & Elbrecht, V. (2021). A practical guide to DNA-based methods for biodiversity assessment.

- Cai, P., Huang, Q., & Zhang, X. (2006). Interactions of DNA with Clay Minerals and Soil Colloidal Particles and Protection against Degradation by DNase. 2971–2976.

- Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., & Holmes, S. P. (2017). Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME Journal, 11(12), 2639–2643. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J. A., & Holmes, S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature Methods, 13(7), 581–583. [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B. J., Duffy, J. E., Gonzalez, A., Hooper, D. U., Perrings, C., Venail, P., Narwani, A., MacE, G. M., Tilman, D., Wardle, D. A., Kinzig, A. P., Daily, G. C., Loreau, M., Grace, J. B., Larigauderie, A., Srivastava, D. S., & Naeem, S. (2012). Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486(7401), 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R., & Raven, P. H. (2020). Vertebrates are on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Chiarello, M., Jackson, C. R., & Mccauley, M. (2022). Ranking the biases : The choice of OTUs vs . ASVs in 16S rRNA amplicon data analysis has stronger effects on diversity measures than rarefaction and OTU identity threshold. 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Cordier, T., Alonso-, T. C. L., Apothéloz-, S. L., Aylagas, E., Bohan, D. A., Bouchez, A., Chariton, A., Creer, S., Frühe, L., Keck, F., Keeley, N., Laroche, O., Leese, F., Pochon, X., Stoeck, T., & Pawlowski, J. (2021). Ecosystems monitoring powered by environmental genomics : A review of current strategies with an implementation roadmap. October 2019, 2937–2958. [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, M. E. (2019). Can Environmental RNA Revolutionize Biodiversity Science? Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 34(8), 694–697. [CrossRef]

- Day, K., Campbell, H., Fisher, A., Gibb, K., Hill, B., Rose, A., & Jarman, S. N. (2019). Development and validation of an environmental DNA test for the endangered Gouldian finch. Endangered Species Research, 40, 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Deagle, B. E., Thomas, A. C., McInnes, J. C., Clarke, L. J., Vesterinen, E. J., Clare, E. L., Kartzinel, T. R., & Eveson, J. P. (2018). Counting with DNA in metabarcoding studies: How should we convert sequence reads to dietary data? Molecular Ecology, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Deiner, K., Yamanaka, H., & Bernatchez, L. (2021). The future of biodiversity monitoring and conservation utilizing environmental DNA. Environmental DNA, 3(1), 3–7. [CrossRef]

- Dibattista, J. D., Berumen, M. L., Priest, M. A., Brauwer, M. De, Coker, D. J., Hay, A., Bruss, G., Mansour, S., Bunce, M., Goatley, C. H. R., Power, M., & Marshell, A. (2022). Environmental DNA reveals a multi- taxa biogeographic break across the Arabian Sea and Sea of Oman. August 2021, 206–221. [CrossRef]

- Djurhuus, A., Port, J., Closek, C. J., Yamahara, K. M., Romero-maraccini, O., Walz, K. R., Goldsmith, D. B., Michisaki, R., Breitbart, M., Boehm, A. B., & Chavez, F. P. (2017). Evaluation of Filtration and DNA Extraction Methods for Environmental DNA Biodiversity Assessments across Multiple Trophic Levels. 4(October), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. 26(19), 2460–2461. [CrossRef]

- Erdozain, M., Thompson, D. G., Porter, T. M., Kidd, K. A., Kreutzweiser, D. P., Sibley, P. K., Swystun, T., Chartrand, D., & Hajibabaei, M. (2019). Metabarcoding of storage ethanol vs. conventional morphometric identification in relation to the use of stream macroinvertebrates as ecological indicators in forest management. Ecological Indicators, 101(January), 173–184. [CrossRef]

- Erickson, R. A., Merkes, C. M., & Mize, E. L. (2019). Sampling Designs for Landscape - level eDNA Monitoring Programs. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 15(5), 760–771. [CrossRef]

- Ficetola, G. F., Miaud, C., Pompanon, F., & Taberlet, P. (2008). Species detection using environmental DNA from water samples. March, 423–425. [CrossRef]

- Funk, W. C. (2021). Population genomics for wildlife conservation and management. October 2020, 62–82. [CrossRef]

- Furlan, E. M., Davis, J., & Duncan, R. P. (2020). Identifying error and accurately interpreting environmental DNA metabarcoding results: A case study to detect vertebrates at arid zone waterholes. Molecular Ecology Resources, 20(5), 1259–1276. [CrossRef]

- Furlan, E. M., & Gleeson, D. (2016). A framework for estimating the sensitivity of eDNA surveys. 641–654. [CrossRef]

- Guerra-castro, E. J., Cajas, J. C., Simões, N., Cruz-motta, J. J., & Mascaró, M. (2021). SSP: an R package to estimate sampling effort in studies of ecological communities. 561–573. [CrossRef]

- Hermans, S. M., Buckley, H. L., & Lear, G. (2018). Optimal extraction methods for the simultaneous analysis of DNA from diverse organisms and sample types. Molecular Ecology Resources, 18(3), 557–569. [CrossRef]

- Hohenlohe, P. A., Funk, W. C., & Rajora, O. P. (2021). Population genomics for wildlife conservation and management. Molecular Ecology, 30(1), 62–82. [CrossRef]

- Holman, L. E., Bruyn, M. De, Creer, S., Carvalho, G., Robidart, J., & Rius, M. (2021). biogeographic patterns. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(June). [CrossRef]

- Holt, W. V, & Brown, J. L. (2014). Reproductive Sciences in Animal Conservation.

- Ji, Y., Ashton, L., Pedley, S. M., Edwards, D. P., Tang, Y., Nakamura, A., Kitching, R., Dolman, P. M., Woodcock, P., Edwards, F. A., Larsen, T. H., Hsu, W. W., Benedick, S., Hamer, K. C., Wilcove, D. S., Bruce, C., Wang, X., Levi, T., Lott, M., … Yu, D. W. (2013). Reliable, verifiable and efficient monitoring of biodiversity via metabarcoding. Ecology Letters, 16(10), 1245–1257. [CrossRef]

- Joos, L., Beirinckx, S., Haegeman, A., Debode, J., Vandecasteele, B., Baeyen, S., Goormachtig, S., Clement, L., & Tender, C. De. (2020). Daring to be differential : metabarcoding analysis of soil and plant-related microbial communities using amplicon sequence variants and operational taxonomical units. 1–17.

- Kelly, R. P., Shelton, A. O., & Gallego, R. (2019). Understanding PCR Processes to Draw Meaningful Conclusions from Environmental DNA Studies. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Klymus, K. E., Richter, C. A., Chapman, D. C., & Paukert, C. (2015). Quantification of eDNA shedding rates from invasive bighead carp Hypophthalmichthys nobilis and silver carp Hypophthalmichthys molitrix q. Biological Conservation, 183, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Klymus, K. E., Ruiz Ramos, D. V., Thompson, N. L., & Richter, C. A. (2020). Development and Testing of Species-specific Quantitative PCR Assays for Environmental DNA Applications. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 165, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Kozich, J. J., Westcott, S. L., Baxter, N. T., Highlander, S. K., & Schloss, P. D. (2013). Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the miseq illumina sequencing platform. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 79(17), 5112–5120. [CrossRef]

- Koziol, A., Stat, M., Simpson, T., Jarman, S., DiBattista, J. D., Harvey, E. S., Marnane, M., McDonald, J., & Bunce, M. (2019). Environmental DNA metabarcoding studies are critically affected by substrate selection. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(2), 366–376. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, M., Wong, S., Nakao, M., & Hyodo, S. (2020). Field application of an improved protocol for environmental DNA extraction , purification , and measurement using Sterivex filter. Scientific Reports, 0123456789, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kyle, K. E., Allen, M. C., Dragon, J., Bunnell, J. F., Reinert, H. K., Zappalorti, R., Jaffe, B. D., Angle, J. C., & Lockwood, J. L. (2022). Combining surface and soil environmental DNA with artificial cover objects to improve terrestrial reptile survey detection. Conservation Biology, 36(6), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Leempoel, K., Hebert, T., & Hadly, E. A. (2020). A comparison of eDNA to camera trapping for assessment of terrestrial mammal diversity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 287(1918). [CrossRef]

- Levy-booth, D. J., Campbell, R. G., Gulden, R. H., Hart, M. M., Powell, R., Klironomos, J. N., Pauls, K. P., Swanton, C. J., Trevors, J. T., & Dunfield, K. E. (2007). Cycling of extracellular DNA in the soil environment. 39, 2977–2991. [CrossRef]

- Macé, B., Hocdé, R., Marques, V., Guerin, E., Valentini, A., Arnal, V., Pellissier, L., & Manel, S. (2022). Evaluating bioinformatics pipelines for population- level inference using environmental DNA. November 2021, 674–686. [CrossRef]

- Machado, W., Franchini, J. C., de Fátima Guimarães, M., & Filho, J. T. (2020). Spectroscopic characterization of humic and fulvic acids in soil aggregates, Brazil. Heliyon, 6(6). [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, A., Nakamura, K., Yamanaka, H., & Kondoh, M. (2014). The Release Rate of Environmental DNA from Juvenile and Adult Fish. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Matthias, L., Allison, M. J., Maslovat, C. Y., Hobbs, J., & Helbing, C. C. (2021). Improving ecological surveys for the detection of cryptic , fossorial snakes using eDNA on and under artificial cover objects. Ecological Indicators, 131, 108187. [CrossRef]

- Morita, H., & Akao, Is. (2021). The effect of soil sample size , for practical DNA extraction , on soil microbial diversity in different taxonomic ranks. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Fonseca, G. A. B. da, & Kent, J. (1998). A critically endangered new species of nectophrynoides (anura: Bufonidae) from the kihansi gorge, udzungwa mountains, tanzania. African Journal of Herpetology, 47(2), 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F. J. A., Lallias, D., Bik, H. M., & Creer, S. (2018). Sample size effects on the assessment of eukaryotic diversity and community structure in aquatic sediments using high-throughput sequencing. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Navajas, M., Lagnel, J., Fauvel, G., & De Moraes, G. (1999). Sequence variation of ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacers (ITS) in commercially important Phytoseiidae mites. Experimental and Applied Acarology, 23(11), 851–859. [CrossRef]

- Nearing, J. T., Douglas, G. M., Comeau, A. M., & Langille, M. G. I. (2018). Denoising the Denoisers : an independent evaluation of microbiome sequence error- correction approaches. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Neice, A. A., & McRae, S. B. (2021). An eDNA diagnostic test to detect a rare, secretive marsh bird. Global Ecology and Conservation, 27, e01529. [CrossRef]

- Newbold, T., Bennett, D. J., Choimes, A., Collen, B., Day, J., Palma, A. De, Dı, S., Edgar, M. J., Feldman, A., Garon, M., Harrison, M. L. K., Alhusseini, T., Echeverria-london, S., Ingram, D. J., Itescu, Y., Kattge, J., Kemp, V., Kirkpatrick, L., Kleyer, M., … Mace, G. M. (2015). Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, R. V., Cromsigt, J. P. G. M., & Spong, G. (2015). DNA left on browsed twigs uncovers bite-scale resource use patterns in European ungulates. Oecologia, 178(1), 275–284. [CrossRef]

- Ogram, A., Sayler, S., & Barkay, T. (1987). The extraction and purification of microbial D N A from sediments. 7, 57–66.

- Pilliod, D., CARENS.GOLDBERG, R. A., & WAITS, L. P. (2014). Factors influencing detection of eDNA from a stream-dwelling amphibian. 109–116. [CrossRef]

- Quéméré, E., Hibert, F., Miquel, C., Lhuillier, E., Rasolondraibe, E., Champeau, J., Rabarivola, C., Nusbaumer, L., Chatelain, C., Gautier, L., Ranirison, P., Crouau-Roy, B., Taberlet, P., & Chikhi, L. (2013). A DNA Metabarcoding Study of a Primate Dietary Diversity and Plasticity across Its Entire Fragmented Range. PLoS ONE, 8(3). [CrossRef]

- Rojahn, J., Gleeson, D. M., Bylemans, J., & Haeusler, T. (2021). Improving the detection of rare native fish species in environmental DNA metabarcoding surveys. October 2020, 990–997. [CrossRef]

- Romanowski, G., Lorenz, M. G., & Wackernagel, W. (1991). Adsorption of plasmid DNA to mineral surfaces and protection against DNase I. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 57(4), 1057–1061. [CrossRef]

- Rourke, M. L., Fowler, A. M., Hughes, J. M., Broadhurst, M. K., Dibattista, J. D., Fielder, S., Wilkes, J., & Elise, W. (2022). Environmental DNA ( eDNA ) as a tool for assessing fish biomass : A review of approaches and future considerations for resource surveys. January 2021, 9–33. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-, D. V, Meyer, R. S., Toews, D., Stephens, M., Kolster, M. K., & Sexton, J. P. (2023). Environmental DNA ( eDNA ) detects temporal and habitat effects on community composition and endangered species in ephemeral ecosystems : A case study in vernal pools. June 2022, 85–101. [CrossRef]

- Sato, H., Sogo, Y., Doi, H., & Yamanaka, H. (2017). Usefulness and limitations of sample pooling for environmental DNA metabarcoding of freshwater fish communities. Scientific Reports, May, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P. D., & Westcott, S. L. (2011). Assessing and Improving Methods Used in Operational Taxonomic Unit-Based Approaches for 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis ᰔ †. 77(10), 3219–3226. [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P. D., Westcott, S. L., Ryabin, T., Hall, J. R., Hartmann, M., Hollister, E. B., Lesniewski, R. A., Oakley, B. B., Parks, D. H., Robinson, C. J., Sahl, J. W., Stres, B., Thallinger, G. G., Van Horn, D. J., & Weber, C. F. (2009). Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 75(23), 7537–7541. [CrossRef]

- Schmieder, R., & Edwards, R. (2011). Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics, 27(6), 863–864. [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, A. J., Chokhachy, R. Al, Schabacker, J., Smith, S., Luikart, G., & Amish, S. J. (2019). Improved detection of rare , endangered and invasive trout in using a new large - volume sampling method for eDNA capture. May, 227–237. [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, A. J., Hutchins, P. R., Forstchen, M., Mckeefry†, M. N., & Swigris, and A. M. (2020). The Elephant in the Lab (and Field): Contamination in Aquatic Environmental DNA Studies. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8(December), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Serrao, N. R., Weckworth, J. K., Mckelvey, K. S., & Dysthe, J. C. (2021). Molecular genetic analysis of air , water , and soil to detect big brown bats in North America Molecular genetic analysis of air , water , and soil to detect big brown bats in North America. Biological Conservation, 261(September), 109252. [CrossRef]

- Sigsgaard, E. E., Jensen, M. R., Winkelmann, I. E., Møller, P. R., Hansen, M. M., & Thomsen, P. F. (2020). Population-level inferences from environmental DNA—Current status and future perspectives. Evolutionary Applications, 13(2), 245–262. [CrossRef]

- Singer, G. A. C., Fahner, N. A., Barnes, J. G., Mccarthy, A., & Hajibabaei, M. (2019). Comprehensive biodiversity analysis via ultra-deep patterned flow cell technology : a case study of eDNA metabarcoding seawater. Scientific Reports, April, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Skelton, J., Cauvin, A., & Hunter, M. E. (2022). Environmental DNA metabarcoding read numbers and their variability predict species abundance, but weakly in non-dominant species. Environmental DNA, August, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Spear, M. J., Embke, H. S., Krysan, P. J., & Vander, M. J. (2021). Application of eDNA as a tool for assessing fish population abundance. March 2020, 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Spear, M. J., Embke, H. S., Krysan, P. J., & Vander Zanden, M. J. (2021). Application of eDNA as a tool for assessing fish population abundance. Environmental DNA, 3(1), 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Stat, M., Huggett, M. J., Bernasconi, R., Dibattista, J. D., Newman, S. J., Harvey, E. S., Bunce, M., & Tina, E. (2017). Ecosystem biomonitoring with eDNA : metabarcoding across the tree of life in a tropical marine environment. Scientific Reports, September, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K. A. (2019). Understanding the effects of biotic and abiotic factors on sources of aquatic environmental DNA. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28(5), 983–1001. [CrossRef]

- Strona, G., & Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2022). Coextinctions dominate future vertebrate losses from climate and land use change. 4345.

- Suarez-bregua, P., Miguel, A., Parsons, K. M., Rotllant, J., Pierce, G. J., Saavedra, C., Robinson, C. V., & Doyle, J. (2022). Environmental DNA ( eDNA ) for monitoring marine mammals : Challenges and opportunities. September, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Taberlet, P., Bonin, A., Zinger, L., & Coissac, E. (2018). Environmental DNA: For biodiversity research and monitoring. Environmental DNA: For Biodiversity Research and Monitoring, 1–253. [CrossRef]

- Taberlet, P., COISSAC, E., HAJIBABAEI, M., & RIESEBERG, L. H. (2012). Environmental DNA. Molecular Ecology, 21(22), R1250–R1252. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, I. S., & Roy, D. (2020). Environmental DNA and RNA as Records of Human Exposome , Including Biotic / Abiotic Exposures and Its Implications in the Assessment of the Role of Environment in Chronic Diseases.

- Thomas, A. C., Howard, J., Nguyen, P. L., Seimon, T. A., & Goldberg, C. S. (2018). ANDeTM: A fully integrated environmental DNA sampling system. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(6), 1379–1385. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P. F., & Willerslev, E. (2015a). Environmental DNA - An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P. F., & Willerslev, E. (2015b). Environmental DNA - An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, P. F., & Willerslev, E. (2015c). Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, S., Takahara, T., Doi, H., Shibata, N., & Yamanaka, H. (2019). The detection of aquatic macroorganisms using environmental DNA analysis—A review of methods for collection, extraction, and detection. Environmental DNA, 1(2), 99–108. [CrossRef]

- van der Heyde, M., Bunce, M., & Nevill, P. (2022). Key factors to consider in the use of environmental DNA metabarcoding to monitor terrestrial ecological restoration. Science of the Total Environment, 848(July), 157617. [CrossRef]

- van der Heyde, M., Bunce, M., Wardell-Johnson, G., Fernandes, K., White, N. E., & Nevill, P. (2020). Testing multiple substrates for terrestrial biodiversity monitoring using environmental DNA metabarcoding. Molecular Ecology Resources, 20(3), 732–745. [CrossRef]

- Vestheim, H., & Jarman, S. N. (2008). Blocking primers to enhance PCR amplification of rare sequences in mixed samples - a case study on prey DNA in Antarctic krill stomachs. Frontiers in Zoology, 5, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wainer, R., Ridgway, H., Jones, E., Peltzer, D., & Dickie, I. (2020). Consequences of environmental DNA pooling. 1–11.

- Wilcox, T. M., McKelvey, K. S., Young, M. K., Jane, S. F., Lowe, W. H., Whiteley, A. R., & Schwartz, M. K. (2013). Robust Detection of Rare Species Using Environmental DNA: The Importance of Primer Specificity. PLoS ONE, 8(3). [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M. D. (2016). Comment : The FAIR Guiding Principles for scienti fi c data management and stewardship. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. E., Huyvaert, K. P., Vercauteren, K. C., Davis, A. J., & Piaggio, A. J. (2018). Detection and persistence of environmental DNA from an invasive, terrestrial mammal. Ecology and Evolution, 8(1), 688–695. [CrossRef]

- WWF. (2020). Living Planet Report 2020 - Bending the curve of biodiversity loss. In Wwf.

- Xu, B., Zeng, X. M., Gao, X. F., Jin, D. P., & Zhang, L. B. (2017). ITS non-concerted evolution and rampant hybridization in the legume genus Lespedeza (Fabaceae). Scientific Reports, 7(January), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yates, M. C., Derry, A. M., & Cristescu, M. E. (2021). Environmental RNA: A Revolution in Ecological Resolution? Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 36(7), 601–609. [CrossRef]

- Yoccoz, N. G., Bråthen, K. A., Gielly, L., Haile, J., Edwards, M. E., Goslar, T., Von Stedingk, H., Brysting, A. K., Coissac, E., Pompanon, F., Sonstebo, J. H., Miquel, C., Valentini, A., De Bello, F., Chave, J., Thuiller, W., Wincker, P., Cruaud, C., Gavory, F., … Taberlet, P. (2012). DNA from soil mirrors plant taxonomic and growth form diversity. Molecular Ecology, 21(15), 3647–3655. [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, H., Viet, H. Q., Vasileiadou, K., Potirakis, A., Arvanitidis, C., Topalis, P., Pavloudi, C., & Pafilis, E. (2020). PEMA: A flexible Pipeline for Environmental DNA Metabarcoding Analysis of the 16S/18S ribosomal RNA, ITS, and COI marker genes. GigaScience, 9(3), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Zheng, Y., Zhan, A., Dong, C., Zhao, J., & Yao, M. (2022). Environmental DNA captures native and non-native fish community variations across the lentic and lotic systems of a megacity. 0097(February), 1–14.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).