Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

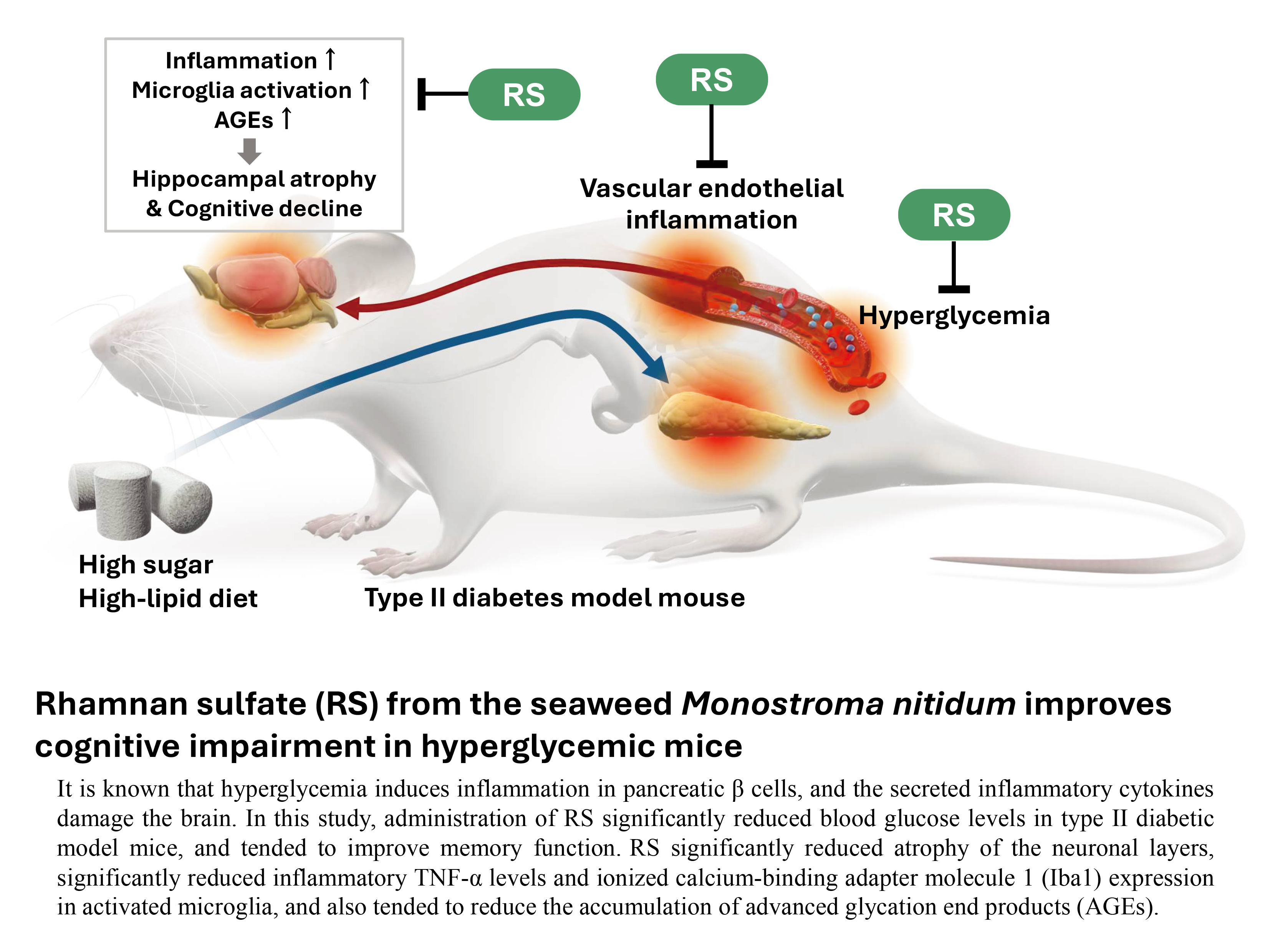

Abstract

Keywords:

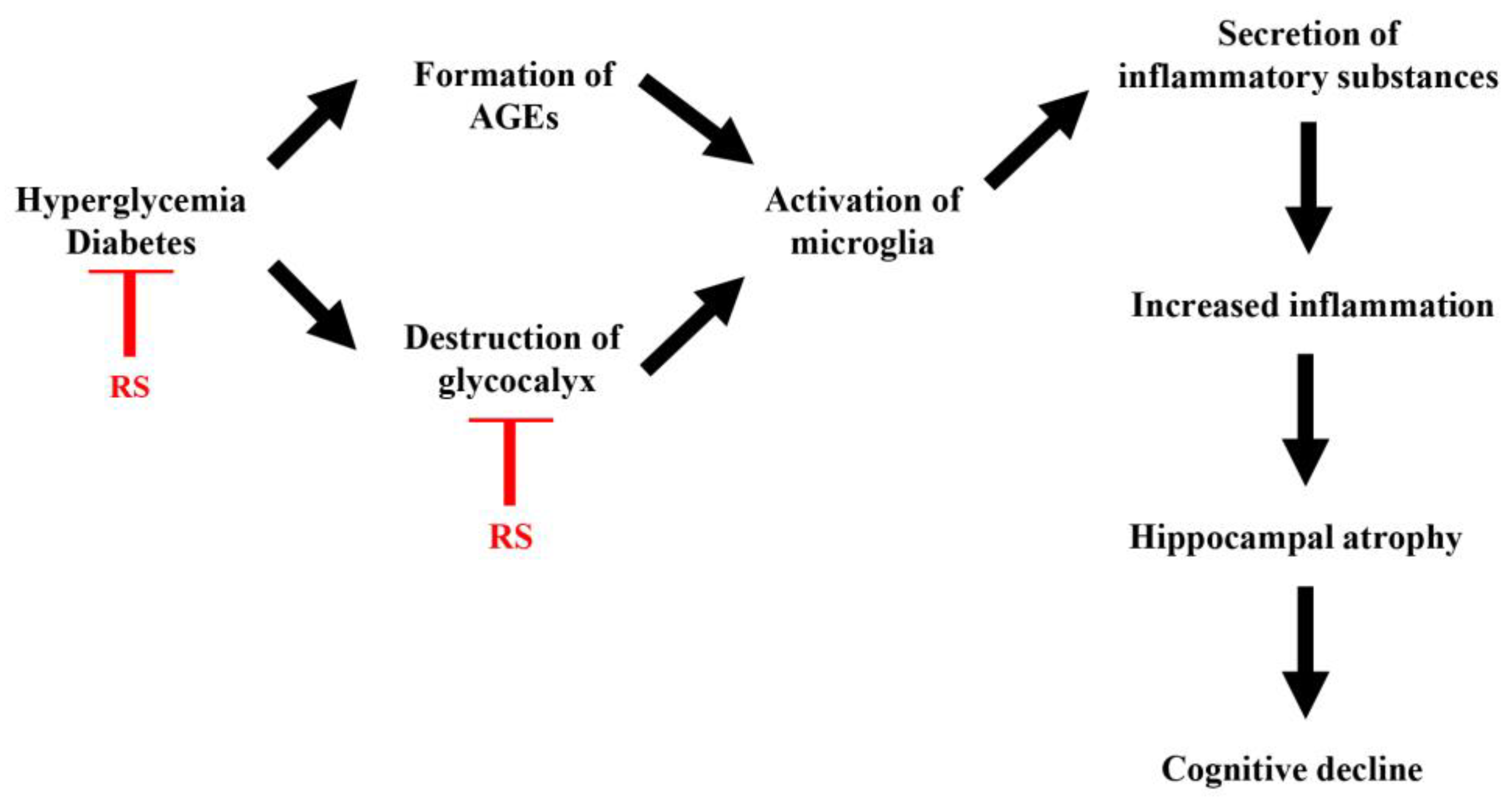

1. Introduction

2. Results

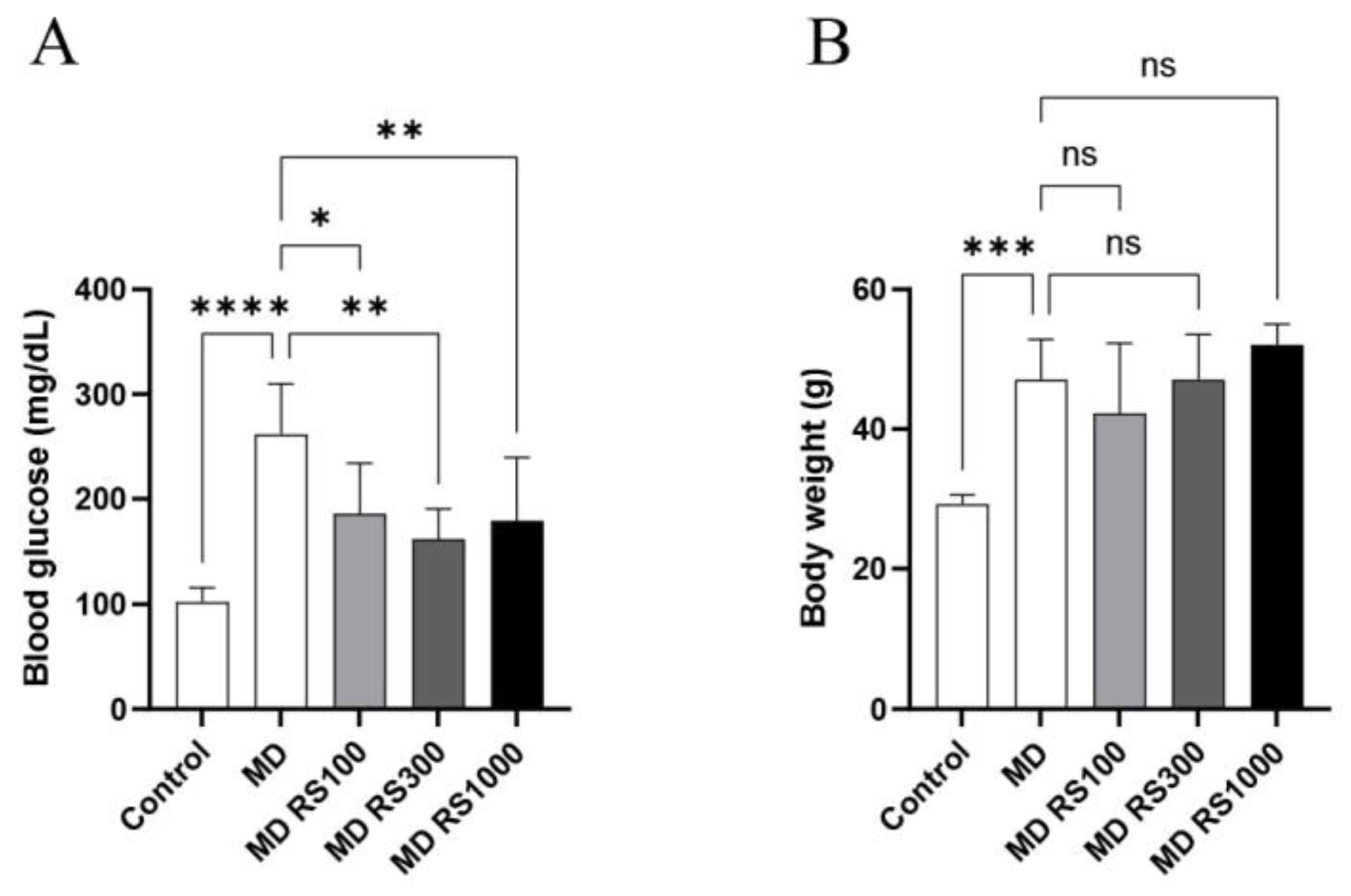

2.1. Body Weight and Blood Glucose Levels

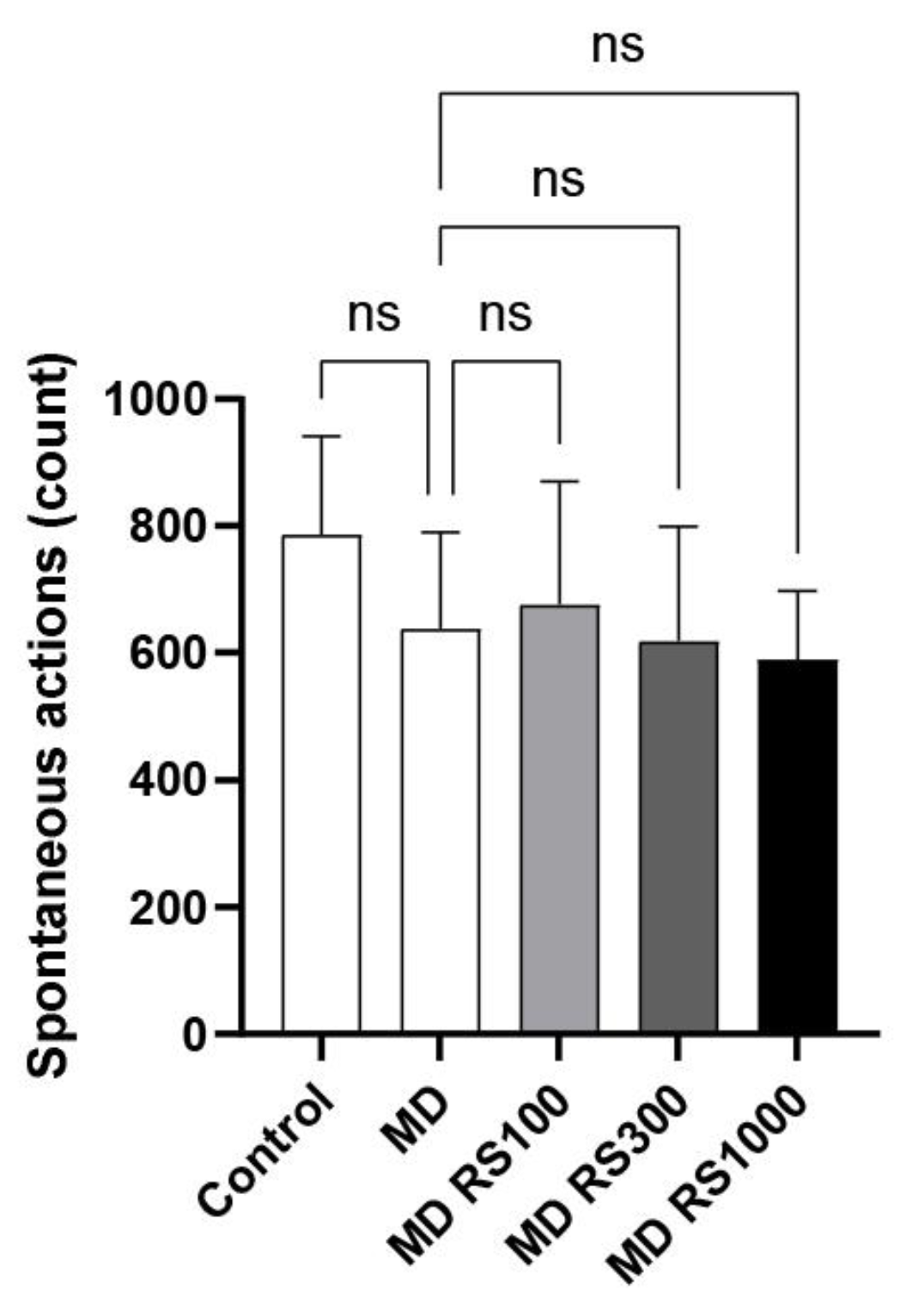

2.1.1. Effect of RS on Spontaneous Locomotor Activity

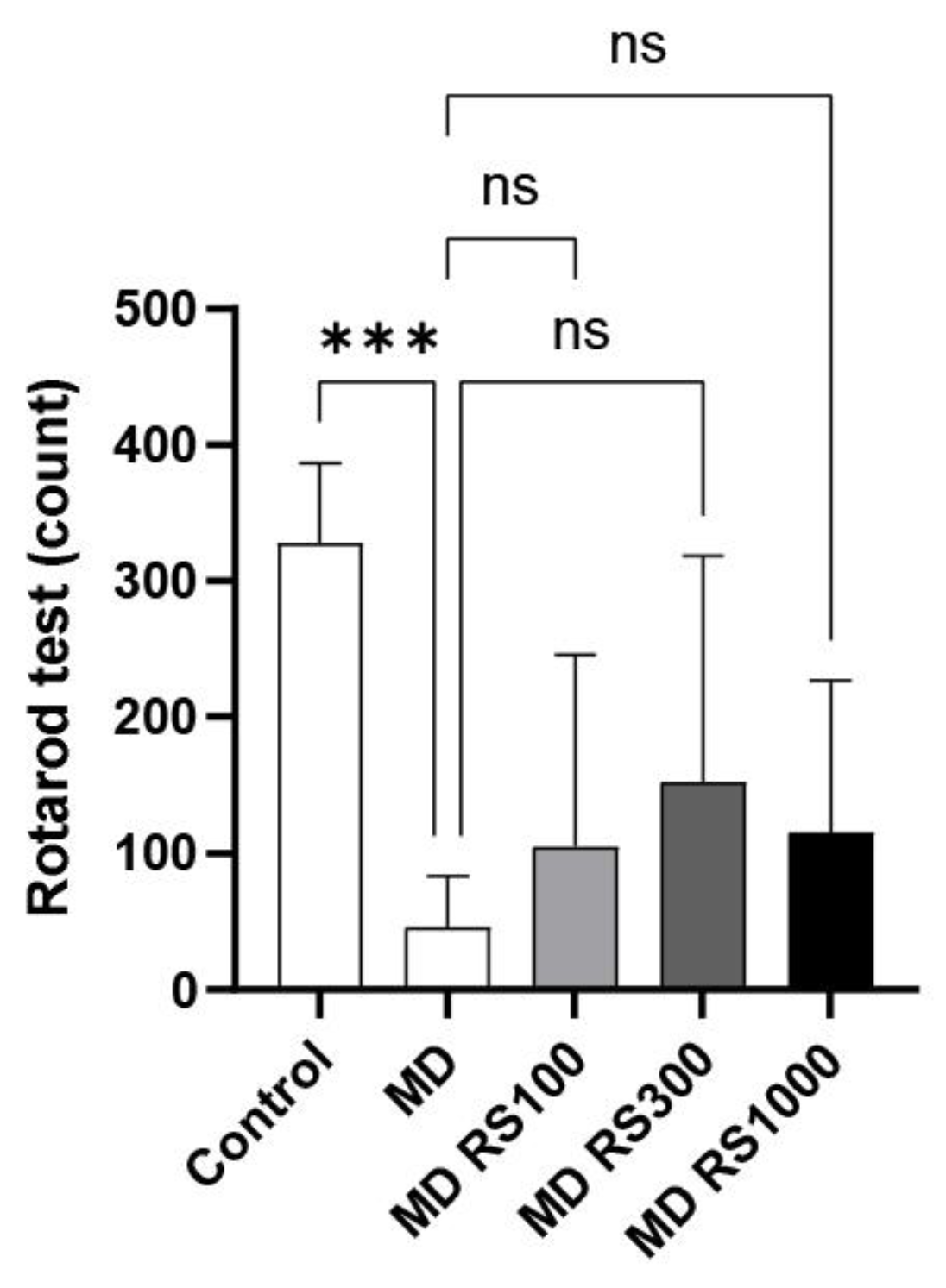

2.1.2. Effect of RS on Rotarod Test

2.1.3. Effect of RS on Eight-Way Maze Test

2.2. Analysis of Hippocampal Pathology Specimens

2.2.1. Effect of RS on Hippocampal Neuronal Layers (CA1, CA2, CA3, and Dentate Gyrus)

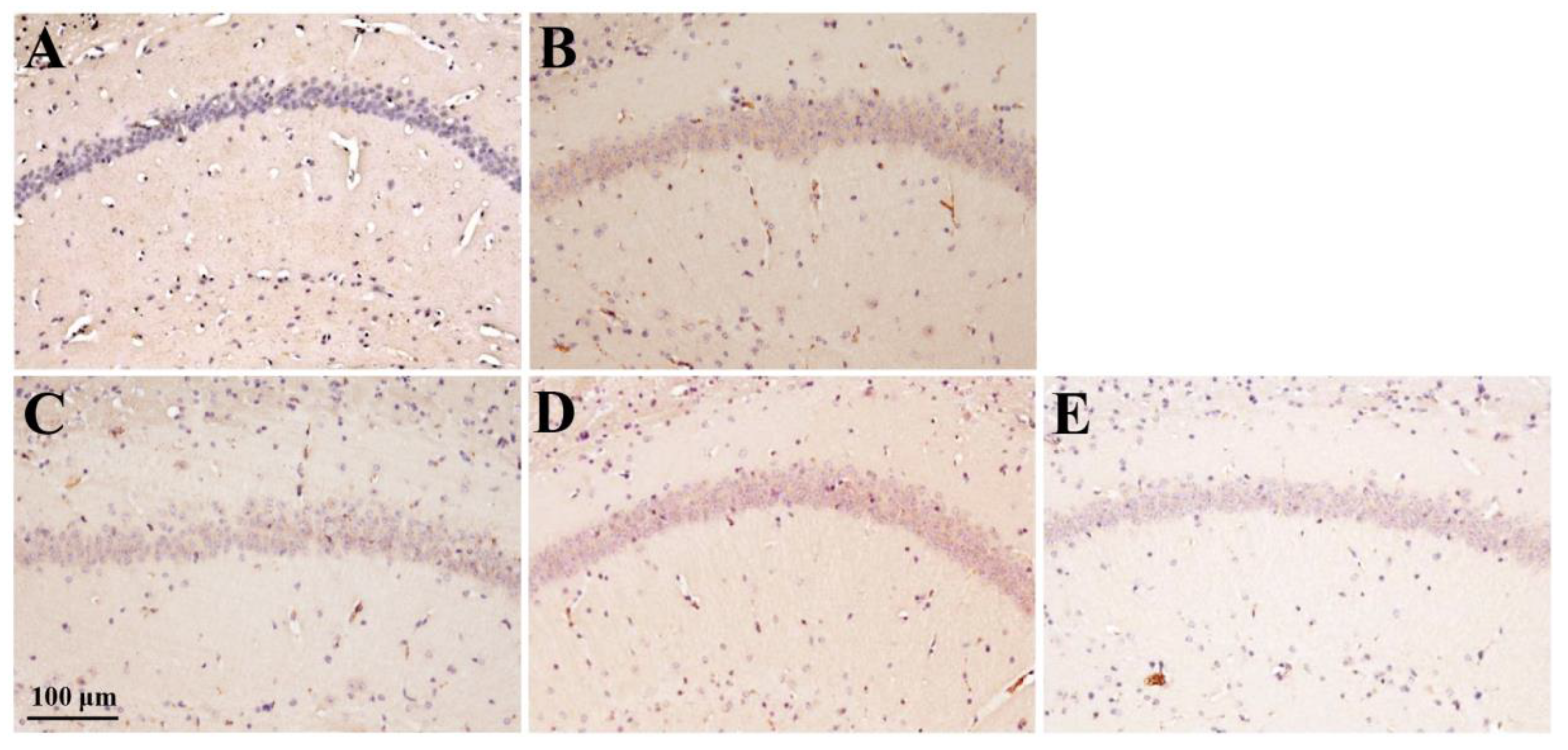

2.2.2. Effect of RS on TNF-α Expression in the Brain

2.2.3. Effect of RS on Iba1 Expression in the Brain

2.2.4. Effect of RS on AGEs Accumulation in the Brain

3. Discussion

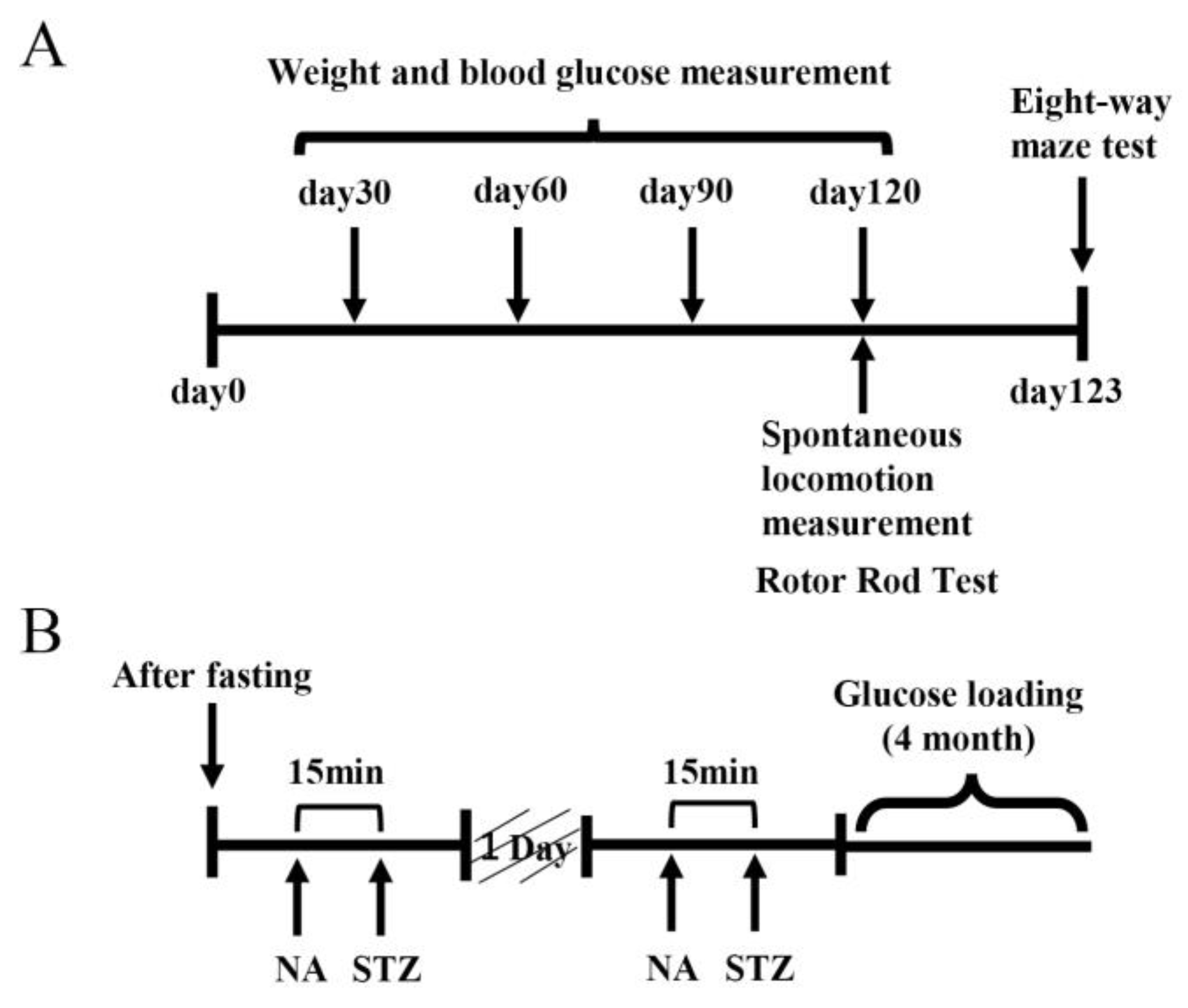

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals

4.2. Behavioral Pharmacological Test

4.3. Brain Sample Preparation

4.4. Histochemical and Immunohistochemical Analysis of Brain Samples

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Additional notice

Abbreviations

| AGE | advanced glycation end products |

| HE | hematoxylin-eosin |

| Iba1 | ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 |

| MD | maltodextrin |

| NA | nicotinamide |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| PPAR | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| RAGE | receptor of AGE |

| RS | rhamnan sulfate |

| SD | standard deviation |

| STZ | streptozotocin |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Launer, L.J.; Miller, M.E.; Williamson, J.D.; Lazar, R.M.; Gerstein, H.C.; Murray, A.M.; Sullivan, M.; Horowitz, K.R.; Ding, J.; Marcovina, S.; et, al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering on brain structure and function in people with type 2 diabetes (ACCORD MIND): a randomized open-label substudy. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukai, N.; Doi, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Hirakawa, Y.; Nagata, M.; Yoshida, D.; Hata, J.; Fukuoka, M.; Nakamura, U.; Kitazono, T.; Kiyohara, Y. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in community-dwelling Japanese subjects: The Hisayama Study. J. Diabetes Invest. 2014, 5, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopf, D.; Frolich, L. Risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease in diabetic patients: a systematic review of prospective trials. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009, 16, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peila, R.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Launer, L.J. Type2 diabetes, APOE Gene, and the Risk for Dementia and Related Pathologies: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, A.; Stolk, R.P.; van Harskamp, F.; Pols, H.A.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 1999, 53, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohara, T.; Doi, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Hata, J.; Iwaki, T.; Kanda, S.; Kiyohara, Y. Glucose tolerance status and risk of dementia in the community: the Hisayama study. Neurology 2011, 7, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adav, S.S.; Sze, S.K. Insight of brain degenerative protein modifications in the pathology of neurodegeneration and dementia by proteomic profiling. Mol. Brain 2016, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.; Imaizumi, T. Diabetic vascular complications: pathophysiology, biochemical basis and potential therapeutic strategy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005, 11, 2279–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglietto-Vargas, D.; Shi, J.; Yager, D.M.; Ager, R.; LaFerla, F.M. Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease crosstalk. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 64, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Wada, T.; Ban, S.; Fujita, K.; Miwa, T. Cognitive function investigation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease with diabetes in a psychiatric hospital. Jpn. Soc. Psychiatr. Pharm. 2022, 6, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M.; Wada, T.; Furukawa, A.; Koriyama, Y.; Miwa, T. Effects of loading glucose on cognitive function in mice. Jpn. Soc. Psychiatr. Pharm. 2023, 6, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M.; Ning, Ma.; Miwa, T. Effects of glucose loading on cognitive function in streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemic mouse models. Jpn. Soc. Psychiatr. Pharm. 2023, 6, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T.; Hanyu, H.; Hirao, K.; Kanetaka, H.; Sakurai, H.; Iwamoto, T. Efficacy of PPAR-γ agonist pioglitazone in mild Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.R.; Barbieri, M.; Boccardi, V.; Angellotti, E.; Marfella, R.; Paolisso, G. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors have protective effect on cognitive impairment in aged diabetic patients with mild cognitive impairment. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, L.; Grenha, A. Sulfated seaweed polysaccharides as multifunctional materials in Drug Delivery Applications. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Xiao, J.; Yu, N.; Yi, G. Impact of Insulin Sensitizers on the Incidence of Dementia:A Meta-Analysis. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2016, 41, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbatecola, A.M.; Rizzo, M.; Grella, R.; Arciello, A.; Laieta, M.T.; Acampora, R.; Passariello, N.; Cacciapuoti, F.; Paolisso, G. Postprandial plasma glucose excursions and cognitive functioning in aged type 2 diabetics. Neurology, 2006, 67, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mao, W.; Hou, Y.; Gao, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, C. Preparation, structure and anticoagulant activity of a low molecular weight fraction produced by mild acid hydrolysis of sulfated rhamnan from Monostroma latissimum. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, N.; Maeda, M. Chemical structure of antithrombin-active Rhamnan sulfate from Monostroma nitidum. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1998, 62, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Shimada, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Nishimura, N. Rhamnan sulphate from Monostroma nitidum attenuates hepatic steatosis by suppressing lipogenesis in a diet-induced obesity zebrafish model. J. Funct. Foods. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Terasawa, M.; Okazaki, F.; Nakayama, H.; Zang, L.; Nishiura, K.; Matsuda, K.; Nishimura, N. Rhamnan sulphate from green algae Monostroma nitidum improves constipation with gut microbiome alteration in double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Zang, L.; Ishimaru, T.; Nishiura, K.; Matsuda, K.; Uchida, R.; Nakayama, H.; Matsuoka, I.; Terasawa, M.; Nishimura, N. Lipid-and glucose-lowering effects of Rhamnan sulphate from Monostroma nitidum with altered gut microbiota in mice. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.4100. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 4342–4352. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Akita, N.; Terasawa, M.; Hayashi, T.; Suzuki, K. Rhamnan sulfate extracted from Monostroma nitidum attenuates blood coagulation and inflammation of vascular endothelial cells. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 73, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasawa, M.; Hiramoto, K.; Uchida, R.; Suzuki, K. Anti-Inflammatory activity of orally administered Monostroma nitidum rhamnan sulfate against lipopolysaccharide-induced damage to mouse organs and vascular endothelium. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasawa, M.; Zang, L.; Hiramoto, K.; Shimada, Y.; Mitsunaka, M.; Uchida, R.; Nishiura, K.; Matsuda, K.; Nishimura, N.; Suzuki, K. Oral administration of rhamnan sulfate from Monostroma nitidum suppresses atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice fed a high-fat diet. Cells 2023, 12, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, D. : Imai.; Y., Ohsawa, K..; Nakajima, K., Fukuuchi, Y.; Kohsaka, S. Microglia-specific localization of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graeber, M.B.; Streit, W.J. Microglia:biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Yamagishi, S.; Yonekura, H.; Doi, T.; Tsuji, H.; Kato, I.; Takasawa, S.; Okamoto, H.; Abedin, J.; Tanaka, N.; et. al. Role of AGE-RAGE system in Vascular injury in diabetes. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 902, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, T.; van Ypersele de Strihou, C.; Kurokawa, K.; Baynes, J.W. Alterations in nonenzymatic biochemistry in uremia: origin and significance of “carbonyl stress” in long-term uremic complications. Kidney Int. 1999, 55, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, A.; Beckman, J.A.; Schmidt, A.M.; Creager, M.A. Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 2006, 114, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.; Fukami, K.; Matsui, T. Crosstalk between advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-receptor RAGE axis and dipeptidyl peptidase-4-incretin system in diabetic vascular complications. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2015, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, Z.; Neapetung, J.; Pacholko, A.; Kiir, T.A.B.; Yamamoto, Y.; Bekar, L.K.; Campanucci, V.A. Hyperglycemia induces RAGE-dependent hippocampal spatial memory impairments. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 229, 113287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparotto, J.; Ribeiro, C.T.; da Rosa-Silva, H.T.; Bortolin, R.C.; Rabelo, T.K.; Peixoto, D.O.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Gelain, D.P. Systemic inflammation changes the site of RAGE expression from endothelial cells to neurons in different brain areas. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 3079–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Quintero, S.V.; Cancel, L.M.; Pierides, A.; Antonetti, D.; Spray, D.C.; Tarbell, J.M. High Glucose Attenuates Shear-Induced Changes in Endothelial Hydraulic Conductivity by Degrading the Glycocalyx. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, T.W.; Bush, P.A.; Chen, Y.; Young, S.P.; Zhang, H.; Millington, D.S.; Granger, D.L.; Mwaikambo, E.D.; Anstey, N.M.; Weinberg, J.B. Glycocalyx breakdown is increased in African children with cerebral and uncomplicated falciparum malaria. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 14185–14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, A.; Targosz-Korecka, M.; Suraj, J.; Proniewski, B.; Jasztal, A.; Marczyk, B.; Sternak, M.; Przybylo, M.; Kurpinska, A.; Walczak, M.; et. al. Degradation of Glycocalyx and Multiple Manifestations of Endothelial Dysfunction Coincide in the Early Phase of Endothelial Dysfunction Before Atherosclerotic Plaque Development in Apolipoprotein E/Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Deficient Mice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelazzi, C.; Villa, G.; Mancinelli, P.; De Gaudio, A.R.; Adembri, C. Glycocalyx and sepsis-induced alterations in vascular permeability. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.T.; Rioux, L.E.; Turgeon, S.L. Alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibition is differentially modulated by fucoidan obtained from Fucus vesiculosus and Ascophyllum nodosum. Phytochemistry 2014, 98, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Golen, R.F.; Reiniers, M.J.; Vrisekoop, N.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Olthof, P.B.; van Rheenen, J.; van Gulik, T.M.; Parsons, B.J.; Heger, M.M. The mechanisms and physiological relevance of glycocalyx degradation in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 1098–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulivor, A.W.; Lipowsky, H.H. Inflammation- and ischemia-induced shedding of venular glycocalyx. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Matsui, K.; Sano, T.; Kubota, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Mano, A.; Yamada, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Kubota, N.; et. al. Differential effects of diet- and genetically induced brain insulin resistance on amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener 2019, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ztotek, M.; Kurowska, A.; Herbet, M.; Piatkowska-Chmiel, I. GLP-1 Analogs, SGLT-2, and DPP-4 Inhibitors: A Triad of Hope for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.H.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Hong, N.; Jung, J.H.; Baik, K.; Cho, H.; Lyoo, C.H.; Ye, B.S.; Sohn, Y.H.; Seong, J.-K.; Lee, PH. Association of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor Use and Amyloid Burden in Patients With Diabetes and AD-Related Cognitive Impairment. Neurology 2021, 97, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, R. ; Sakazaki, F,; Okuno, T.; Nakamuro, K,; Ueno, H. Difference in glucose intolerance between C57BL/6J and ICR strain mice with streptozotocin/nicotinamide-induced diabetes. Biomed. Res, 33. [CrossRef]

- Szkudelski, T. The mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in B cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol. Res. 2001, 50, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchigata, Y, Yamamoto, H, Kawamura, A, Okamoto, H. Protection by superoxide dismutase, catalase, and poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibitors against alloxan- and streptozotocin-induced islet DNA strand breaks and against the inhibition of proinsulin synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 6: 6084–6088. PMID, 6084.

| TNF-α | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | p value |

| A Control | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| B MD | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0.001 a * |

| C MD + RS100 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.005 b * |

| D MD + RS300 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 b * |

| E MD + RS1000 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 b * |

|

a vs. Control b vs. MD |

| lba1 | +1 | +2 | +3 | p value |

| A Control | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| B MD | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0.003 a * |

| C MD + RS100 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 b * |

| D MD + RS300 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.004 b * |

| E MD + RS1000 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0.007 b * |

|

a vs. Control b vs. MD |

| AGE | 0 | +1 | +2 | p value |

| A Control | 4 | 2 | 0 | |

| B MD | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0.036 a * |

| C MD + RS100 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.076 b |

| D MD + RS300 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.497 b |

| E MD + RS1000 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0.289 b |

|

a vs. Control b vs. MD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).