1. Introduction

The rising global aging population has led to increased cases of age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [

1]. These conditions not only impair memory and executive functions but also reduce overall cognitive performance, significantly affecting the quality of life of older adults [

2]. Given the limitations of pharmacological treatments, which often have variable efficacy and side effects, non-pharmacological interventions have gained traction as viable alternatives to support healthy cognitive aging [

3]. Among these, physical and cognitive training programs have been shown to improve brain health and slow cognitive decline by promoting neuroplasticity [

4].

Cognitive training has long been recognized for its ability to engage higher-order cognitive functions such as memory, problem-solving, and attention. Interventions that focus on these skills have been shown to improve cognitive task performance and induce structural and functional brain changes in older adults [

5]. Additionally, it is still unknown whether a combination of exercise and cognitive training (CECT) is more effective than either intervention alone. The present systematic review and meta-analysis were undertaken to evaluate the effect of CECT on working memory in the elderly [

6]. In an fMRI study on dual-task performance, the training group showed increased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation, which was correlated with improved performance [

7]. ‘

Recently, a realistic Drumming-Based Cognitive and Physical Training was developed specifically to enhance memory in older adults. This intervention which integrates cognitive exergaming with a virtual drumming component, led to greater brain activation, particularly reflected in increased oxyhemoglobin levels in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) than conventional cognitive training [

8]. This form of intervention has the potential to improve brain function by activating the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), areas responsible for cognitive control, decision-making, and emotional regulation in healthy adults [

8]. Rhythm-based activities like drumming engage both hemispheres of the brain and stimulate regions involved in motor control, attention, and executive function. Specifically, drumming has been shown to increase connectivity between the motor cortex and prefrontal cortex, enhancing functional integration between cognitive and motor processes [

9,

10,

11].

Building on the existing evidence, this study aims to examine the impact of drumming-based cognitive and physical training on cognitive performance, emotional well-being, and brain activity in older adults. Specifically, this research will focus on changes in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, task performance, and prefrontal cortex activity, using fNIRS to measure brain activation. It is hypothesized that Older Adults undergoing the drumming intervention of 4 weeks will show significant improvements in cognitive performance, emotional well-being, and brain activity compared to the control group.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to investigate the effects of a drumming-based cognitive and physical training program on older adults. A total of 40 participants, aged 55 years or older, were recruited. These individuals were randomly assigned to either an experimental group (n = 20) that received the drumming intervention or a control group (n = 20) that performed conventional memory training.

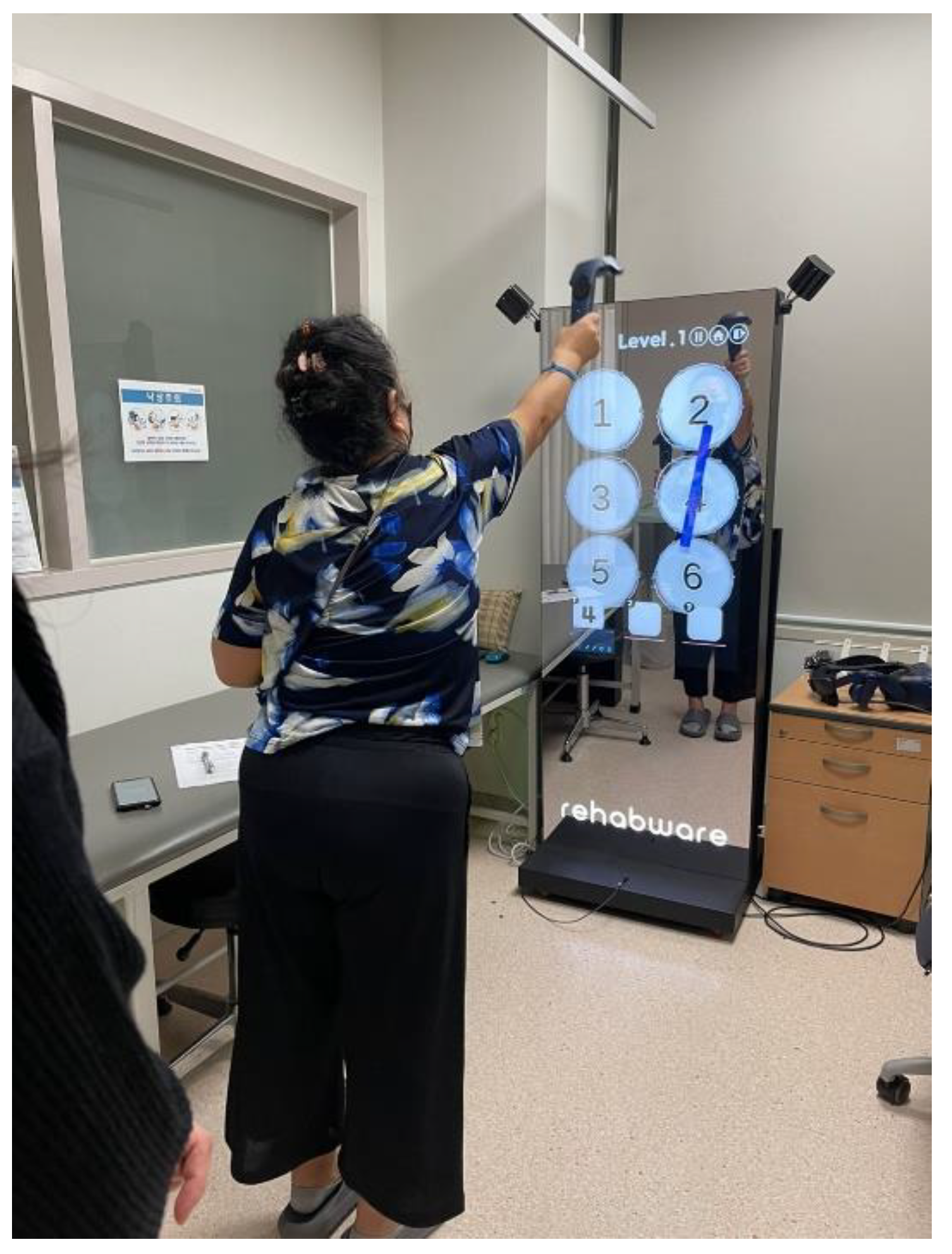

The experimental group engaged in memory training using a realistic Drumming-based task within an isolated laboratory setting. Participants stood before a 42-inch LED monitor, where they observed and memorized digits presented on the screen for five seconds. Following this, they were directed to strike virtual drums in the correct sequence using an electronic drumstick held in both hands. This drumstick simulated the tactile sensations and vibrations of actual drumming, while the monitor provided synchronized visual and auditory feedback to enhance the immersive drumming experience. The participants of a control group underwent memory training using conventional paper-and-pencil methods in a dedicated laboratory setting, where digits were visually presented one at a time on a computer screen for five seconds, with the memory span length beginning with three digits and gradually increasing to nine, and after the numbers disappeared from the screen, participants were asked to write them in the correct sequential order on a response sheet [

12].

The intervention consisted of 30-minute sessions, three times per week, for a total of 12 sessions over four weeks. Each session was structured to progressively increase in difficulty, beginning with simple rhythmic patterns and gradually incorporating more complex sequences that required higher levels of cognitive engagement and physical coordination. The training aimed to activate cognitive functions through rhythm-based tasks that engaged both the dominant and non-dominant hands. Participants were required to follow rhythmic drumming patterns while also responding to cognitive cues, thus simultaneously stimulating cognitive control, motor coordination, and emotional regulation.

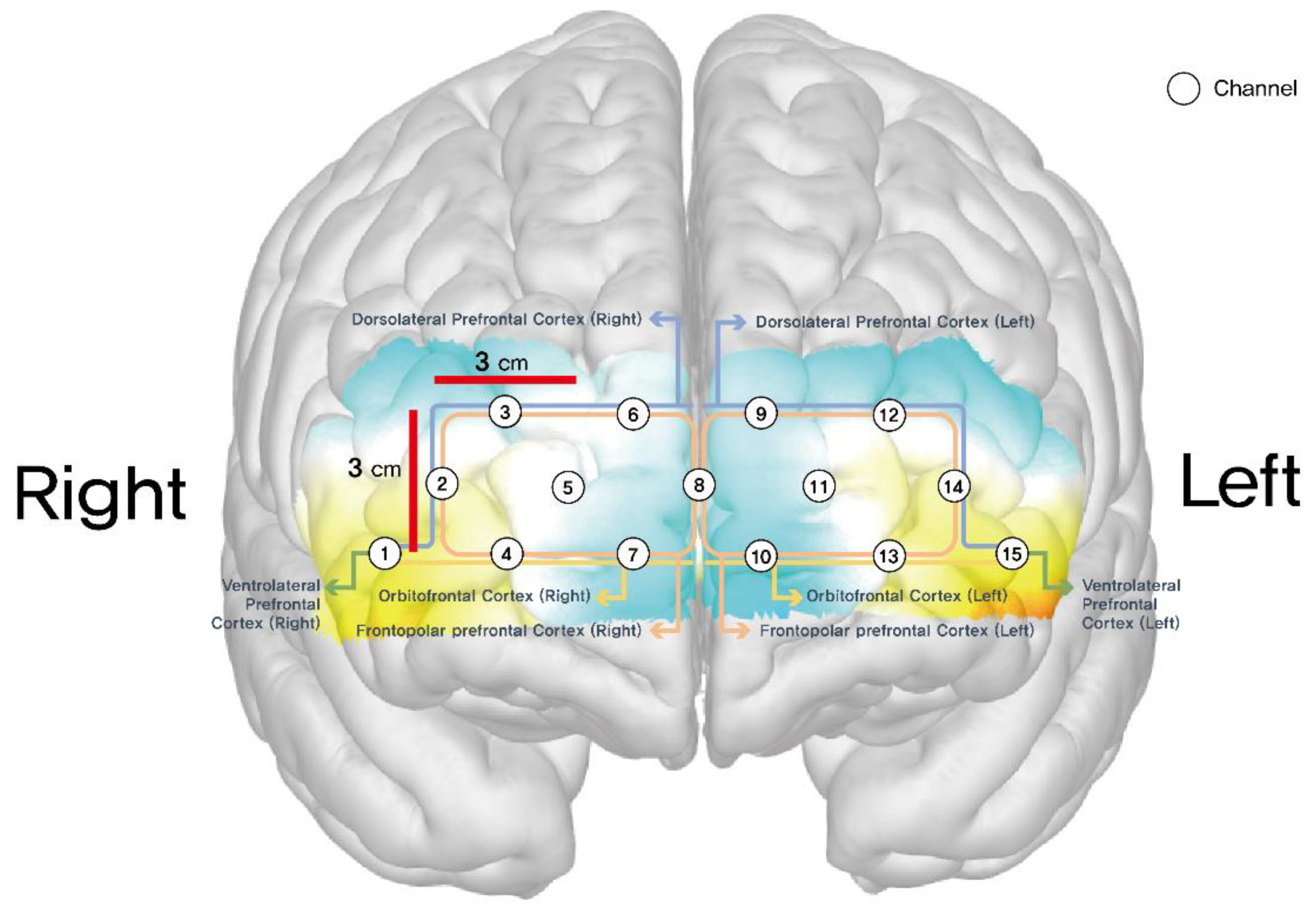

Data collection occurred at two time points, both before the intervention and after the intervention. Cognitive performance was assessed using a variety of task-based measures, including the number of correct answers, total training attempts, success rate, Time to Highest Level. Cognitive and emotional functions were assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to evaluate global cognitive function, and the Geriatric Depression Scale (KGDS) to assess depressive symptoms. Both the experimental and control groups underwent fNIRS (NIRSIT Lite Adult; OBELAB Inc.) measurements during their first and final visits to assess the hemodynamic responses of cerebral blood volume during the intervention by detecting oxyhemoglobin levels in the brain. The final output of each optode was then reported as mean total oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO μm). A total of 15 channels were located on both sides of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (channels 2, 3, 12, 14), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) (channels 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 15), and frontopolar prefrontal cortex (FPPFL) (channels 5, 6, 8, 9,11) [

13]. Positions of these channels were: channel 1, right lateral OFC; channels 4 and 7, right medial OFC; channels 2 and 3, right DLPFC; channel 15, left lateral OFC; channels 10 and 13, left medial OFC; channels 12 and 14, left DLPFC; channels 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11, frontopolar prefrontal cortex.

Figure 2 shows positions of these channels.

Figure 1.

Memory training by virtual drum beating.

Figure 1.

Memory training by virtual drum beating.

Figure 2.

Schematic positions of fNIRS channels.

Figure 2.

Schematic positions of fNIRS channels.

Channels 1 through 15 corresponded to specific areas of the prefrontal cortex that are known to be involved in these higher-order cognitive processes. Statistical analysis was performed using paired t-tests to compare pre- and post-intervention results within each group, and independent t-tests to compare the post-intervention differences between the experimental and control groups. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance, and effect sizes were calculated to assess the magnitude of the intervention’s impact.

All participants were required to have no severe cognitive impairments that could affect their ability to engage in the intervention. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the university’s institutional review board, and written informed consent was collected from all participants before their involvement in the research. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital (IRB No. DUIH-2023-04-018), and the study was registered at the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS, KCT0008500. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all procedures were performed following the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

A total of 40 participants were enrolled in the study, with 20 assigned to the experimental group and 20 to the control group. At baseline, no significant differences were observed between the groups in demographic characteristics, including age (p = 0.6156), weight (p = 0.1930), and gender distribution (p = 0.2357). The only notable difference was in height, with the control group being significantly taller on average (p = 0.0385). Baseline measures of cognitive performance and brain activity were also comparable between the groups, with no significant differences observed in MMSE scores, correct answers, total training attempts, or brain activity across the 15 prefrontal regions (p > 0.05).

Post-intervention, the experimental group exhibited significant improvements in cognitive performance. The number of correct answers increased by 10.35 points (p = 0.0004), and the success rate of task completions improved by 19.44% (p = 0.0001). Between-group comparisons confirmed the effectiveness of the drumming intervention, with the experimental group outperforming the control group in correct answers (p = 0.0248) and success rate (p = 0.0003).

The fNIRS data revealed significant changes in brain activity in the experimental group, particularly in two key regions of the prefrontal cortex. Channel 1, located in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), showed a near-significant increase in brain activity post-intervention (p = 0.074). Channel 15, located in the left orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), exhibited a significant increase in brain activity (p = 0.028). These findings suggest that drumming-based cognitive and physical training effectively enhances cognitive function and prefrontal cortex activity in older adults.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of subjects in the experimental group and the control group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of subjects in the experimental group and the control group.

| Measure |

Control Group (n=20) |

Experimental Group (n=20) |

p-value |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Male |

6 (30%) |

2 (10%) |

0.235 |

| Female |

14 (70%) |

18 (90%) |

Age, years

mean (SD)

|

62.95 (5.76) |

63.75 (4.09) |

0.6156 |

Height, cm

mean (SD)

|

164.45 (7.69) |

159.80 (5.91) |

0.038# |

Weight, kg

mean (SD)

|

61.25 (7.89) |

58.25 (6.34) |

0.193# |

Pre MMSE

mean (SD)

|

27.25 (2.57) |

27.00 (1.52) |

0.710## |

Table 2.

Difference of measures after cognitive memory training in each groups.

Table 2.

Difference of measures after cognitive memory training in each groups.

| |

Control Group (n=20) |

Experimental Group (n=20) |

p-value between groups |

| Measure |

Pre

Mean (SD) |

Post, Mean (SD) |

Difference Mean, (SD) |

p-value |

Pre, Mean (SD) |

Post, Mean (SD) |

Difference, Mean, (SD) |

p-value |

| Correct Answers |

33.60 (4.35) |

36.95 (9.29) |

3.35 (7.81) |

0.070 |

34.45 (10.11) |

44.80 (5.99) |

10.35 (10.88) |

0.000 |

0.024 |

| Total Training Attempts |

49.40 (7.47) |

53.35 (9.00) |

3.95 (9.15) |

0.068 |

52.70 (6.76) |

52.95 (5.73) |

0.25 (6.21) |

0.859 |

0.142 |

| Success Rate |

68.52 (6.00) |

68.31 (12.35) |

-0.21 (12.88) |

0.943 |

65.16 (17.38) |

84.59 (6.17) |

19.44 (17.84) |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| Time to Highest Level |

511.00 (187.37) |

273.45 (90.09) |

-237.55 (237.29) |

0.000 |

486.55 (338.64) |

123.60 (94.17) |

-362.95 (284.94) |

0.000 |

0.138 |

| MMSE |

27.25 (2.57) |

28.80 (1.44) |

1.55 (1.64) |

0.000 |

27.00 (1.52) |

28.95 (1.15) |

1.95 (1.28) |

0.000 |

0.394 |

| GDS |

5.00 (4.96) |

5.25 (5.11) |

0.25 (1.62) |

0.498 |

8.50 (5.41) |

8.05 (6.01) |

-0.45 (3.39) |

0.560 |

0.410 |

Table 3.

Differences in HbO when undergoing intervention in both groups (µm).

Table 3.

Differences in HbO when undergoing intervention in both groups (µm).

| |

Intervention of first visits,

Mean (SD) |

Intervention of final visits,

Mean (SD) |

| Brain Region |

Experimental |

Control |

p-value |

Experimental |

Control |

p-value |

| Region 1 |

-0.10 (1.34) |

-0.30 (1.06) |

0.606 |

0.52 (1.48) |

1.22 (0.82) |

0.074 |

| Region 2 |

0.34 (1.10) |

-0.20 (1.39) |

0.180 |

0.58 (1.17) |

0.80 (1.63) |

0.627 |

| Region 3 |

-0.34 (1.89) |

-0.11 (0.65) |

0.608 |

0.54 (1.56) |

0.48 (0.99) |

0.891 |

| Region 4 |

-0.25 (0.74) |

-0.39 (1.10) |

0.636 |

0.68 (0.82) |

0.71 (1.07) |

0.930 |

| Region 5 |

0.48 (0.75) |

0.03 (0.72) |

0.060 |

0.01 (0.65) |

0.25 (1.00) |

0.364 |

| Region 6 |

0.09 (1.48) |

-0.08 (0.67) |

0.635 |

0.32 (1.23) |

0.50 (1.12) |

0.627 |

| Region 7 |

-0.29 (1.06) |

-0.47 (0.73) |

0.525 |

0.50 (0.89) |

0.73 (1.23) |

0.512 |

| Region 8 |

0.18 (1.92) |

-0.34 (0.77) |

0.268 |

0.15 (2.33) |

0.48 (1.32) |

0.589 |

| Region 9 |

0.01 (1.25) |

-0.18 (0.87) |

0.581 |

0.13 (1.37) |

-0.01 (1.00) |

0.724 |

| Region 10 |

-0.44 (0.98) |

-0.49 (1.01) |

0.886 |

0.66 (0.93) |

0.72 (1.42) |

0.857 |

| Region 11 |

-0.15 (0.79) |

-0.29 (1.07) |

0.636 |

0.36 (0.85) |

0.25 (0.96) |

0.702 |

| Region 12 |

-0.22 (0.76) |

-0.55 (0.76) |

0.171 |

0.23 (0.84) |

0.45 (0.84) |

0.427 |

| Region 13 |

-0.43 (0.68) |

-0.74 (0.57) |

0.124 |

0.56 (0.54) |

1.03 (1.06) |

0.086 |

| Region 14 |

0.39 (1.83) |

-0.10 (0.83) |

0.279 |

-0.12 (2.14) |

0.73 (1.19) |

0.128 |

| Region 15 |

-0.14 (1.28) |

-0.51 (1.18) |

0.343 |

0.51 (1.34) |

1.61 (1.69) |

0.028 |

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide the evidence that a drumming-based cognitive and physical training intervention can lead to significant improvements in cognitive performance, emotional well-being, and brain activity in older adults. Music-based and rhythm-based interventions have received growing attention due to their unique ability to engage multiple cognitive systems simultaneously A meta-analysis by Pietschnig et al. (2010) analyzed the cognitive effects of music exposure, showing that while Mozart music has been linked to improvements in spatial ability, its overall impact on broader cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and executive function remains inconclusive [

14]. Additionally, rhythmic interventions have been found to enhance mood, reduce stress, and improve emotional regulation [

15]. Our findings showed a significant increase in the number of correct task answers post-intervention (p = 0.0004) and Between-group comparisons (p = 0.0248), supporting the effectiveness of cognitive training in improving accuracy. This is consistent with Nouchi et al., where tasks like Digit Cancellation, Symbol Search, and Digit Symbol Coding assessed cognitive gains through correct responses, highlighting the role of structured training in enhancing cognitive function in older adults [

16]. After applying a 4-week, 12-session drumming-based cognitive and physical training intervention, the significant increase in success rate (19.44%, p = 0.0001) suggests improved task accuracy and learning efficiency. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that physical activity and multimodal training contribute to cognitive resilience by enhancing executive function, attentional control, and neuroplasticity [

17,

18].

The final measurements obtained from each optode were expressed as the mean total oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO µm). A total of 15 channels were strategically positioned across both hemispheres, focusing on specific prefrontal regions: the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (channels 2, 3, 12, 14), the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) of channels 1, 4, 7, 10, 13 and 15 and the frontopolar prefrontal cortex (FPPFL) of channels 5, 6, 8, 9 and 11 [

13]. Regarding their exact placement, channel 1 was located on the right lateral OFC, while channels 4 and 7 were positioned in the right medial OFC. Channels 2 and 3 were mapped onto the right DLPFC, whereas channel 15 was assigned to the left lateral OFC. Furthermore, channels 10 and 13 corresponded to the left medial OFC, channels 12 and 14 were designated for the left DLPFC, and channels 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11 covered the frontopolar prefrontal cortex. This distribution ensured a comprehensive assessment of hemodynamic activity in these key cognitive regions [

13]. In the results, the mean HbO µm channel 15 located on the left OFC of Experimental group, was statistically significant when compared to the Control group (p = 0.0285). The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) plays a crucial role in cognitive flexibility and behavioral adaptation, particularly in response to changes in reward contingencies. Previous research has demonstrated that OFC is heavily involved in reversal learning, where individuals must adjust their stimulus-reward associations following changes in contingencies. Lesion studies have shown that damage to the OFC results in significant impairments in reversal learning, whereas other forms of cognitive flexibility, such as extra-dimensional set-shifting, are more strongly associated with the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC) [

19,

20]. Functional neuroimaging studies confirm that OFC activation increases during reversal learning, particularly after negative feedback, underscoring its role in modifying decision-making strategies based on reward-related information [

21]. Additionally, the OFC is implicated in emotional regulation, interacting with the amygdala to modulate affective responses and inhibit maladaptive emotional reactions [

22,

23].

In this study, after a 4-week, 12-session drumming-based cognitive and physical training intervention, the mean HbO concentration in channel 15, located in the left OFC of the experimental group, was significantly higher compared to the control group (p = 0.0285). This finding contrasts with our previous study, which examined healthy adults and found significant activation in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, Channel 2) and right medial OFC (Channels 7 and 10) during a single drumming session [

8]. Given that the OFC is primarily involved in affective and reinforcement learning [

24]. older adults in this study may have relied more on these processes during training. In contrast, younger adults in the previous study likely engaged executive control mechanisms mediated by the DLPFC, as suggested by prior research on age-related differences in cognitive control strategies [

25,

26].

This prolonged engagement may have facilitated neural adaptation in cognitive and affective processing networks, potentially contributing to increased OFC activation in older adults. While previous research suggests that extended cognitive training enhances prefrontal neuroplasticity [

27]., further investigation is needed to determine the specific mechanisms underlying increased OFC involvement in older adults.

Overall, these findings suggest that drumming-based cognitive-motor training influences distinct neural mechanisms depending on age and training duration. The increased OFC activation observed in this study aligns with its established role in adaptive decision-making and emotional regulation. Future research should further explore how age-related differences, intervention duration, and cognitive demands influence the recruitment of prefrontal regions during cognitive-motor training.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a 4-week drumming-based cognitive and physical training program can lead to significant improvements in both cognitive performance and brain activity in older adults. The significant increases in correct answers, success rates, and MMSE scores observed in the experimental group, along with the reductions in depressive symptoms, suggest that drumming-based interventions offer a promising approach for enhancing cognitive and emotional health in aging populations. The observed changes in brain activity, particularly in regions of the prefrontal cortex associated with cognitive control and emotional regulation, provide further evidence of the potential neuroplastic effects of this intervention. As such, drumming-based cognitive training may serve as an effective non-pharmacological tool for preventing or mitigating age-related cognitive decline.

Author Contributions

BSK made substantial contributions to the experimental design, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. YGN made substantial contributions to the data collection, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital. This study was performed following protocols approved by the IRB (No. DUIH-2023-04-018) and included only patients who provided written informed consent. Trial registration: KCT0008500 Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS), Republic of Korea..

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), grant-funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1C1C2007812).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

References

- Liu, Y. , Tan, Y., Zhang, Z., Yi, M., Zhu, L., & Peng, W. (2024). The interaction between ageing and Alzheimer's disease: insights from the hallmarks of ageing.

- Livingston, G. , Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S.,... & Orgeta, V. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 396(10248), 413-446. [CrossRef]

- James, C. E. , Müller, D. M., Müller, C. A., Van de Looij, Y., Altenmuller, E., Kliegel, M.,... & Marie, D. (2024). Randomized controlled trials of non-pharmacological interventions for healthy seniors: Effects on cognitive decline, brain plasticity and activities of daily living—A 23-year scoping review. Heliyon.

- Castellote-Caballero, Y. , Carcelén Fraile, M. D. C., Aibar-Almazán, A., Afanador-Restrepo, D. F., & González-Martín, A. M. (2024). Effect of combined physical–cognitive training on the functional and cognitive capacity of older people with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. BMC medicine, 22(1), 281.

- Lampit, A. , Hallock, H., & Valenzuela, M. (2014). Computerized cognitive training in cognitively healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of effect modifiers. PLOS Medicine, 11(11), e1001756. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. , Zang, M., Wang, B., & Guo, W. (2023). Does the combination of exercise and cognitive training improve working memory in older adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ, 11, e15108.

- Erickson, K. I. , Colcombe, S. J., Wadhwa, R., Bherer, L., Peterson, M. S., Scalf, P. E.,... & Kramer, A. F. (2007). Training-induced functional activation changes in dual-task processing: an FMRI study. Cerebral cortex, 17(1), 192-204.

- Nam, Y.-G. , & Kwon, B.-S. (2023). Prefrontal cortex activation during memory training by virtual drum beating: A randomized controlled trial. Healthcare, 11(2559), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Saarman, E. (2006). Feeling the beat: Symposium explores the therapeutic effects of rhythmic music. Stanford news.

- Bengtsson, S. L. , Ullen, F. ( 45(1), 62–71.

- Deyo, L. J. (2016). Cognitive functioning of drumming and rhythm therapy for neurological disorders.

- Moberly, A. C. , Pisoni, D. B., & Harris, M. S. (2017). Visual working memory span in adults with cochlear implants: Some preliminary findings. World journal of otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery, 3(04), 224-230.

- Cho,T. H.; Nah, Y.; Park, S.H.; Han, S. Prefrontal cortical activation in Internet Gaming Disorder Scale high scorers during actual real-time internet gaming: A preliminary study using fNIRS. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 492–505.

- Pietschnig, J. , Voracek, M., & Formann, A. K. (2010). Mozart effect–Shmozart effect: A meta-analysis. Intelligence, 38(3), 314-323.

- Fancourt, D. , Perkins, R. ( 11(3), e0151136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouchi, R. , Taki, Y., Takeuchi, H., Hashizume, H., Nozawa, T., Sekiguchi, A.,... & Kawashima, R. (2012). Beneficial effects of short-term combination exercise training on diverse cognitive functions in healthy older people: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 13, 1-10.

- Kramer, A. F. , Colcombe, S. I. ( 26(1), 124–127.

- McAuley, E. , Kramer, A. F., & Colcombe, S. J. (2004). Cardiovascular fitness and neurocognitive function in older adults: a brief review. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 18(3), 214-220.

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Dissociation in prefrontal cortex of affective and attentional shifts. Nature 1996;380:69–72.

- Keeler JF, Robbins TW. Translating cognition from animals to humans. Biochem Pharm. 2011;81:1356–66.

- Hampshire A, Owen AM. Fractionating attentional control using event-related fMRI. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1679–89.

- Levy BJ, Anderson MC. Purging of memories from conscious awareness tracked in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16785–94.

- Schmitz TW, Correia MM, Ferreira CS, Prescot AP, Anderson MC. Hippocampal GABA enables inhibitory control over unwanted thoughts. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1311.

- Rolls, E. T. (2004). The functions of the orbitofrontal cortex. Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 11-29. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, R. , Anderson, N. D., Locantore, J. K., & McIntosh, A. R. (2002). Aging gracefully: compensatory brain activity in high-performing older adults. Neuroimage, 17(3), 1394-1402.

- Nashiro, K. , Sakaki, M., Braskie, M. N., & Mather, M. (2017). Resting-state networks associated with cognitive processing show more age-related decline than those associated with emotional processing. Neurobiology of aging, 54, 152-162.

- Park, D. C. , & Bischof, G. N. (2013). The aging mind: neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 15(1), 109-119.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).