Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Agricultural tractor operators deal with health risks from engine and attachments noise, especially during prolonged exposure. This study measured noise levels in three tractors—one with a cabin and two without—at PTO speeds of 540, 750, and 1000 RPM. Measurements were taken at the operator’s seat and up to 15 m away using a sound level meter. Statistical analysis and machine learning models, including Linear Regression, Polynomial Regression (PR2), Support Vector Regression, and Random Forest (RF), were applied to predict spatial noise distribution. Results showed that noise levels at the operator’s seat exceeded 85 dB, with non-cabin tractors surpassing 100 dB, posing significant health risks. The Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed significant differences, with Dunn’s post-hoc test showing higher noise levels in non-cabin tractors. RPM variations did not significantly affect noise levels. The RF model performed best (R² = 0.89, RMSE = 2.06), with distance and cabin presence as key predictors. A 2D and 3D spatial analysis using RF regression provided insights for protecting worker health and tractor integrity, enhancing potential failure prediction based on abnormal noise patterns.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Noise Level Measurements

2.2. Data Analysis

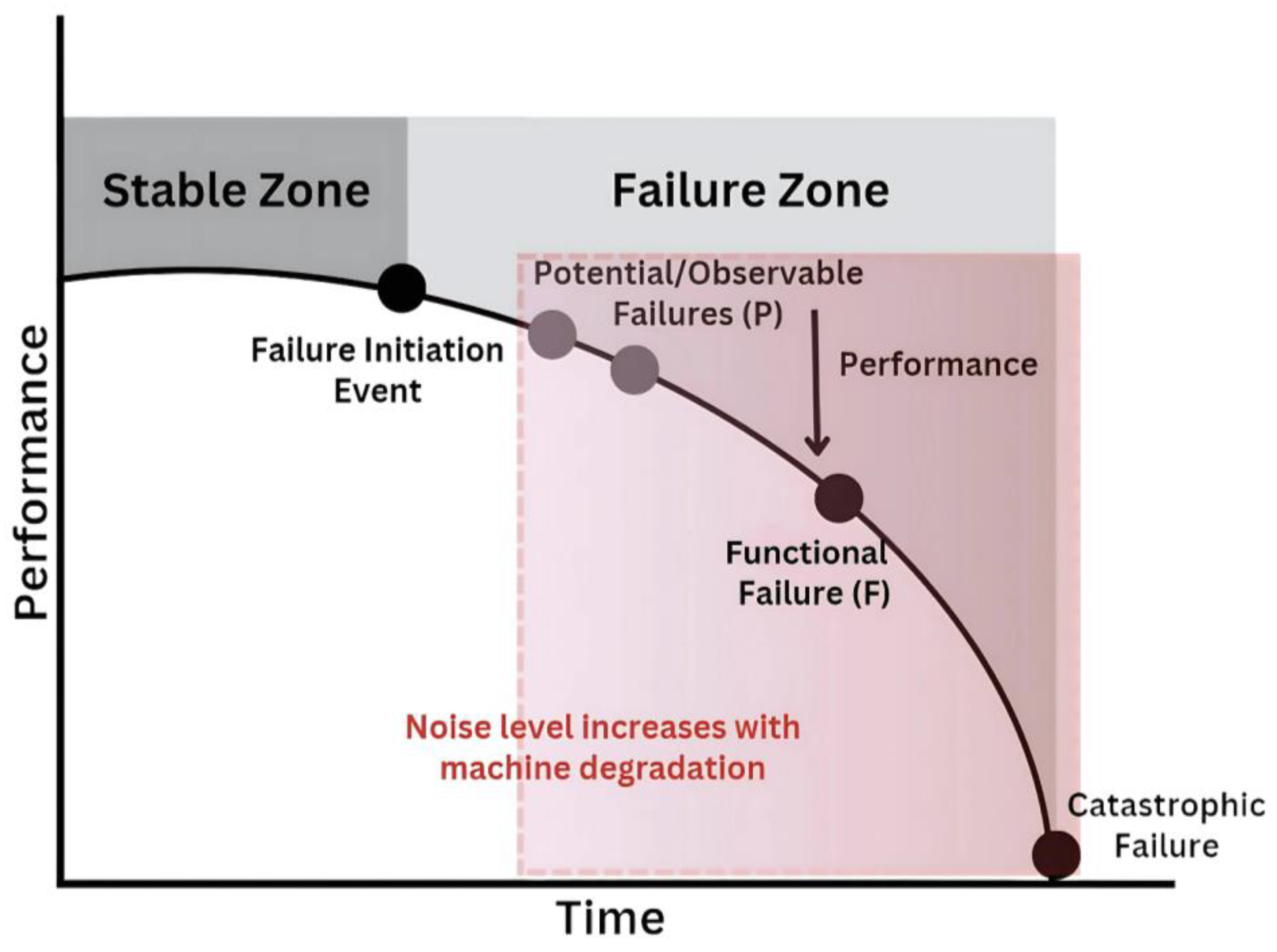

2.3. Development of Machine Learning Models to Predict Potential Failures

3. Results and Discussion

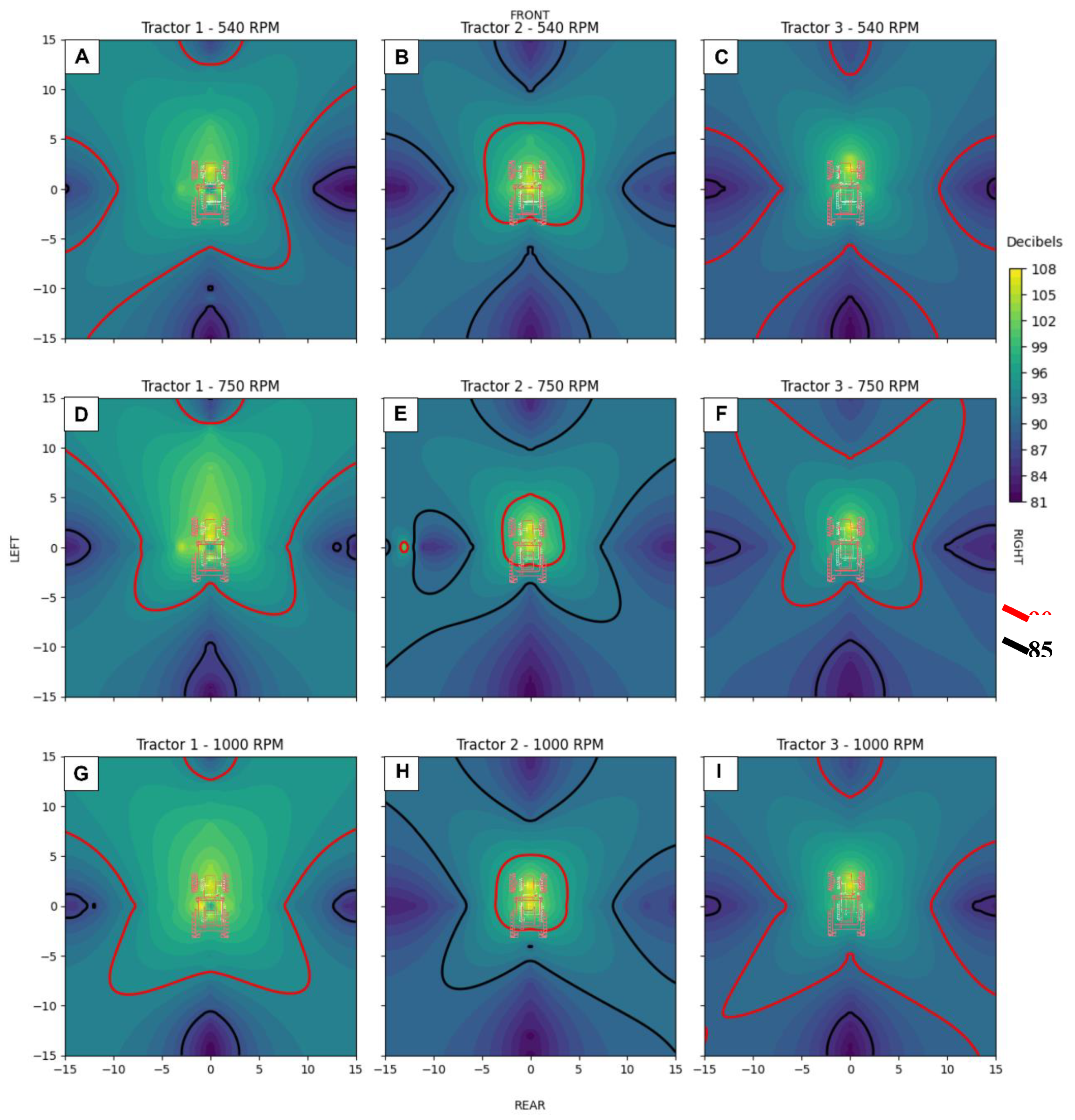

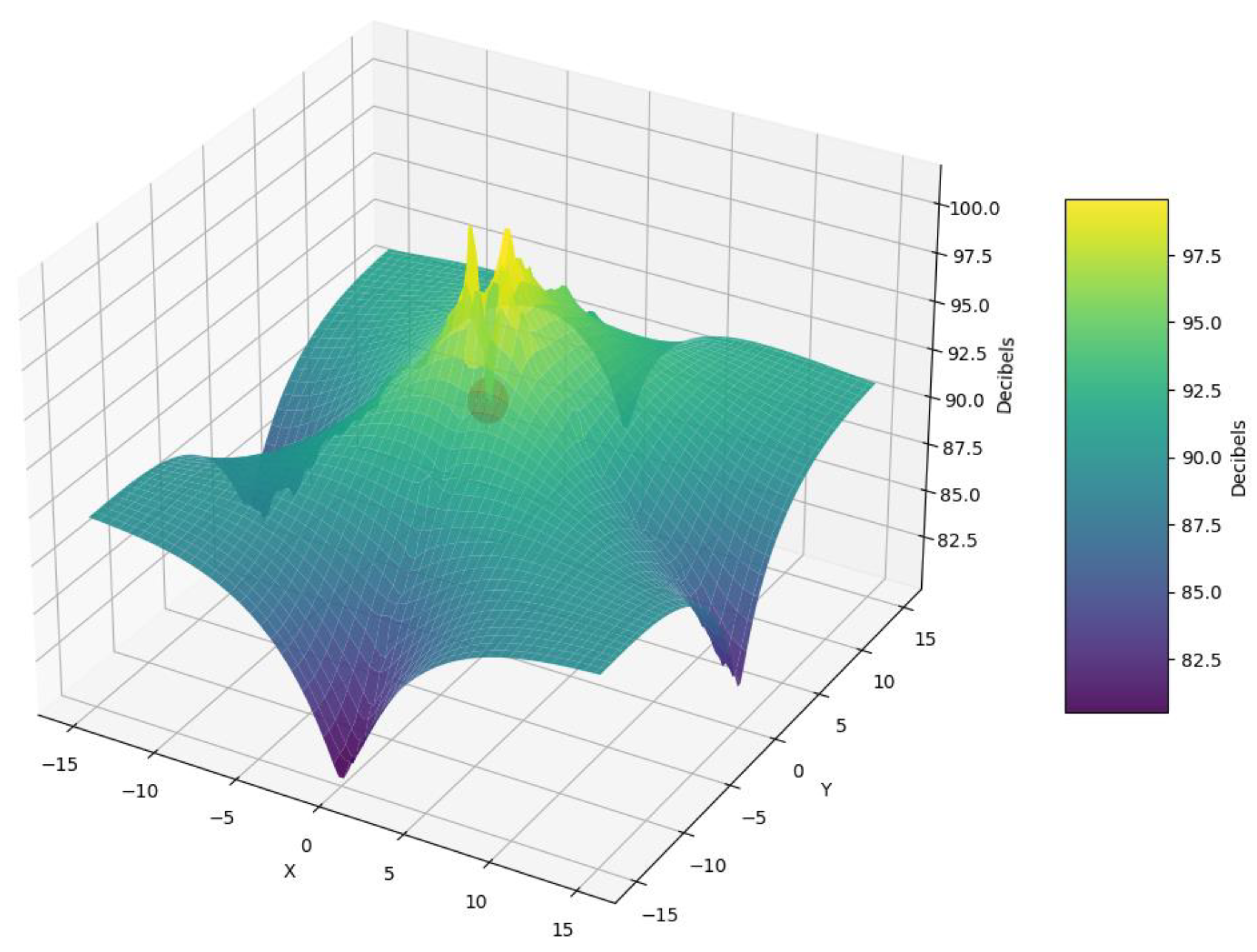

3.1. Spatial Noise Level Distribution Analysis

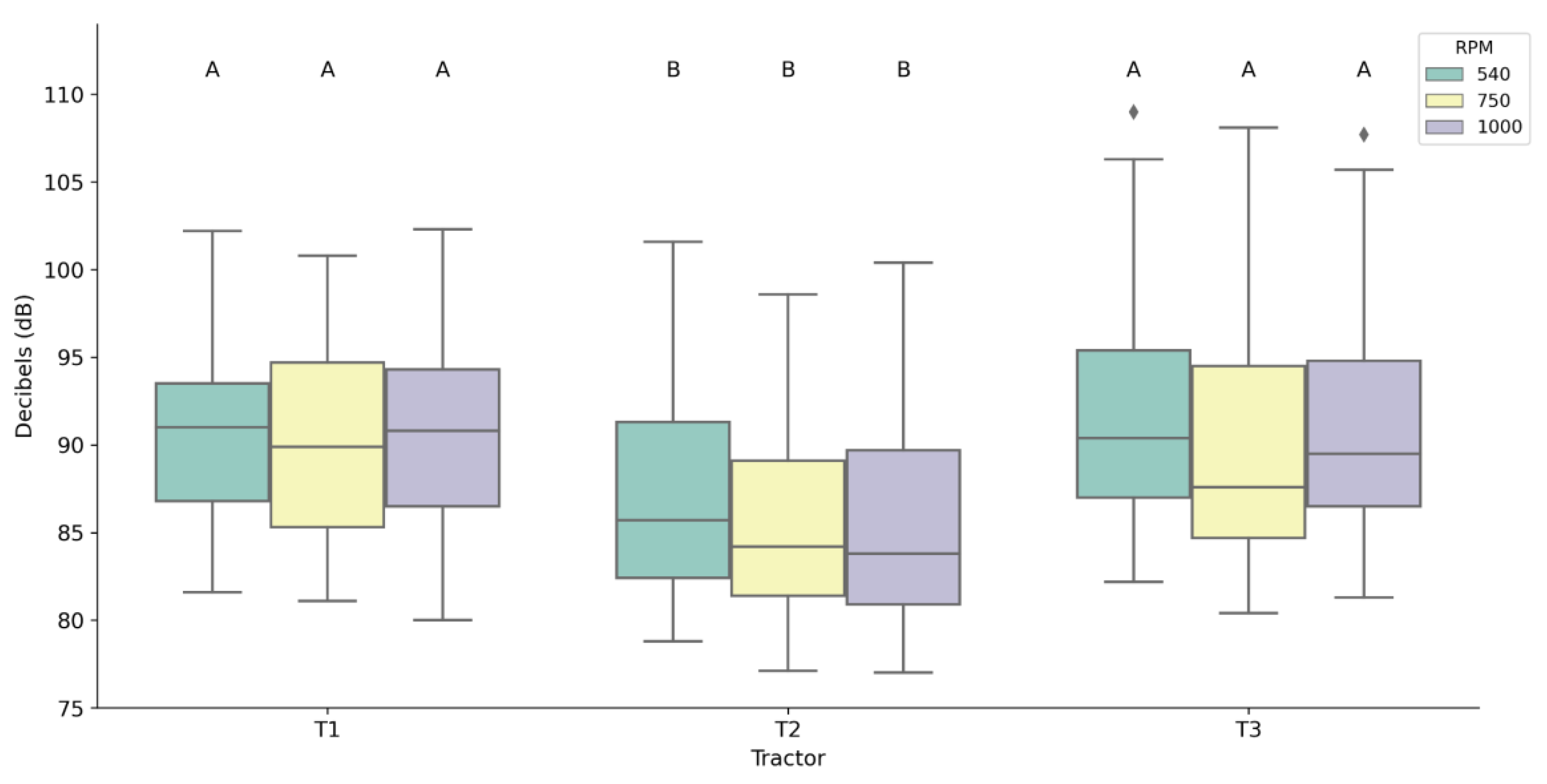

3.2. Statistical Analysis

3.3. Use of Random Forest Model as a Tool to Detect Potential Failures

Conclusions

Supplemental Material

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Mean Diff | p-adj | Reject |

| T1_540 | T1_750 | 0.47213 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_540 | T1_1000 | -0.03770 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_540 | T2_540 | 3.62459 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T1_540 | T2_750 | 5.24426 | 0.0191 | TRUE |

| T1_540 | T2_1000 | 5.16721 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T1_540 | T3_540 | -1.02623 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_540 | T3_750 | 1.08525 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_540 | T3_1000 | -0.39508 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_750 | T1_1000 | -0.50984 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_750 | T2_540 | 3.15246 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T1_750 | T2_750 | 4.77213 | 0.0178 | TRUE |

| T1_750 | T2_1000 | 4.69508 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T1_750 | T3_540 | -1.49836 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_750 | T3_750 | 0.61311 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_750 | T3_1000 | -0.86721 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_1000 | T2_540 | 3.66230 | 0.0004 | TRUE |

| T1_1000 | T2_750 | 5.28197 | 0.0991 | FALSE |

| T1_1000 | T2_1000 | 5.20492 | 0.0004 | TRUE |

| T1_1000 | T3_540 | -0.98852 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_1000 | T3_750 | 1.12295 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T1_1000 | T3_1000 | -0.35738 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T2_540 | T2_750 | 1.61967 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T2_540 | T2_1000 | 1.54262 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T2_540 | T3_540 | -4.65082 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T2_540 | T3_750 | -2.53934 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T2_540 | T3_1000 | -4.01967 | 0.0174 | TRUE |

| T2_750 | T2_1000 | -0.07705 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T2_750 | T3_540 | -6.27049 | 0.0165 | TRUE |

| T2_750 | T3_750 | -4.15902 | 0.0028 | TRUE |

| T2_750 | T3_1000 | -5.63934 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T2_1000 | T3_540 | -6.19344 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T2_1000 | T3_750 | -4.08197 | 0.0000 | TRUE |

| T2_1000 | T3_1000 | -5.56230 | 0.0166 | TRUE |

| T3_540 | T3_750 | 2.11148 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T3_540 | T3_1000 | 0.63115 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

| T3_750 | T3_1000 | -1.48033 | 1.0000 | FALSE |

References

- K. J. Stoss, J. K. J. Stoss, J. Deere, J. Deere European, J. Sobotzik, and E. R. Kreis, “Tractor Power for Implement Operation-Mechanical, Hydraulic, and Electrical: An Overview Bin Shi”, Accessed: May 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.asabe.org.

- and D., S. Pérez, Diego, “Mantenimiento básico de máquinas e instalaciones en la industria alimentaria,” Málaga, España: IC Editorial. Accessed: Sep. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C34&inst=7103165812348674092&q=Mantenimiento+Básico+de+Máquinas+en+instalaciones+en+la+Industria+alimentaria&btnG=.

- C. Guillén Subirán, “Consideraciones sobre la salud laboral de los trabajadores en el sector agropecuario,” Gestión práctica de riesgos laborales: Integración y desarrollo de la gestión de la prevención, ISSN 1698-6881, No. 179, 2020, págs. 35-43, no. 179, pp. 35–43, 2020, Accessed: Sep. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7291147&info=resumen&idioma=SPA.

- Vallone, M.; Bono, F.; Quendler, E.; Febo, P.; Catania, P. Risk exposure to vibration and noise in the use of agricultural track-laying tractors. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2016, 23, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, D.W. Control of Farm Tractor Intake and Exhaust Noise. 50th Anniversary SAE Tractor Meeting (1966). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Jahanbakhshi, A.; Yousefi, M.; Karami-Boozhani, S.; Heidarbeigi, K.; Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y. The effect of combined resistance muffler on noise pollution and the allowable driver exposure in Massey-Ferguson tractors (MF 285 and MF 299). J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2020, 19, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamo, J. Effects of cab noise environment on the hearing perception of agricultural tractor drivers. Appl. Acoust. 1979, 12, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhao, X. Noise Reduction in Tractor Cabs Using Coupled Resonance Acoustic Materials. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 32689–32695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilski, B. Exposure to audible and infrasonic noise by modern agricultural tractors operators. Appl. Ergon. 2013, 44, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOS Santos, L.M.; Ferraz, G.A.; Batista, M.L.; Martins, F.B.; Barbosa, B.D. Characterization of noise emitted by a low-profile tractor and its influence on the health of rural workers. An. da Acad. Bras. de Cienc. 2020, 92, e20200460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aybek, H. Kamer, S. A.-A. Ergonomics, and undefined 2010, “Personal noise exposures of operators of agricultural tractors,” Elsevier, Accessed: Sep. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003687009001021?casa_token=3HWqzGyIzwcAAAAA:oK_yX1EHs1jhotUPx8wvAHb5QXxQPTEkcqvdN_4qHhLGoPIfwyEHQsa2ep2ci1GPlcsMIGqtAg.

- Suggs, B.K.H.A.C.W. Tractor Noise and Operator Performance. Trans. ASAE 1968, 11, 0001–0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- and, M. Cecchini. Zoppello, G., D. Monarca, “Aziende agricole, il rischio da rumore ed il - Google Scholar.” Accessed: Sep. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C34&inst=7103165812348674092&q=Aziende+agricole%2C+il+rischio+da+rumore+ed+il&btnG=.

- Souza, L.H.; Vieira, L.B.; Fernandes, H.C.; Lima, J.S.S. Níveis de ruído emitidos por uma recolhedora-trilhadora de feijão. Eng. Agricola 2004, 24, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. L. da Vitória, “Avaliação do nível de ruído emitido por tratores em diferentes operações agrícolas,” Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Accessed: Sep. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C34&inst=7103165812348674092&q=Avaliação+do+nível+de+ruído+emitido+por+tratores+em+diferentes+operações+agrícolas&btnG=.

- B. J. Ahlstrom, J. B. J. Ahlstrom, J. Zilles, and M. L. Pate, “Innovations in Engine Design and Cab Structures of Agricultural Equipment Considerations for Noise Exposure Written for presentation at the 2022 ASABE Annual International Meeting Sponsored by ASABE,” pp. 1–3, 2022.

- Cecchini, M.; Piccioni, F.; Ferri, S.; Coltrinari, G.; Bianchini, L.; Colantoni, A. Preliminary Investigation on Systems for the Preventive Diagnosis of Faults on Agricultural Operating Machines. Sensors 2021, 21, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.A.G.; de Sá, J.L.R.; Menegatti, R. Diagnostic of Failure in Transmission System of Agriculture Tractors Using Predictive Maintenance Based Software. Agriengineering 2019, 1, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Monir, M.U.; Sarkar, S.M.; Aziz, A.A.

- Di, G.; Yao, Y.; Chen, C.; Lin, Q.; Li, Z. An experiment study on the identification of noise sensitive individuals and the influence of noise sensitivity on perceived annoyance. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. del A. MINAM, “ds.085.2003.pcm_ ECA RUIDO,” mediante Decreto Supremo N° 085-2003-PCM, pp. 1–11, 2003, [Online]. Available: https://sinia.minam.gob.

- Congreso de la República del Perú, “Ley De Seguridad N°29783 Y Reglamento De Seguridad DS N° 005-2012-TR,” El peruano, vol. 1, pp. 5–20, 2011, [Online]. Available: https://www.diariooficial.elperuano.pe/pdf/0052/ley-seguridad-salud-en-el-trabajo.

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Boiral, O.; Arana, G.; Allur, E. OHSAS 18001 certification and work accidents: Shedding light on the connection. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 68, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Code, F. O. R. S. Code, F. O. R. The, O. Measurement, O. N. Agricultural, and F. Tractors, “Code 5 Oecd Standard Code for the Official Measurement of Noise At the Driving Position ( S ),” no. July, pp. 1–17, 2007.

- Franklin, R.C.; Depczynski, J.; Challinor, K.; Williams, W.; Fragar, L.J. Factors Affecting Farm Noise During Common Agricultural Activities. J. Agric. Saf. Heal. 2006, 12, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, P.S.; Gaikwad, A.A.; Badgujar, S.Y.; Surkutwar, Y.V.; Karanth, N.V. Noise Reduction on Agricultural Tractor. Symposium on International Automotive Technology 2013. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Mccolly, H.F.; Martin, J.W. Introduction to Agricultural Engineering. Soil Sci. 1956, 81, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.T.; Cortez, J.W.; Nagahama, H.D.J. NÍVEL DE RUÍDO DE UM TRATOR AGRÍCOLA EM FUNÇÃO DA ROTAÇÃO, DA DISTÂNCIA, DA VELOCIDADE E DA CONDIÇÃO DO SOLO OBTIDO POR MEIO DE DECIBELÍMETRO COM E SEM PROTEÇÃO DE VENTO. Ènerg. NA Agric. 2012, 27, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, S.R.; Dias, V.d.O.; Cornélio, J.P.L.; Hitz, M.E. Noise in agricultural machinery: Modernization and workers' health; Seven Events: Sao Jose dos Pinhais, Parana, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barač, Ž.; Plaščak, I.; Jurišić, M.; Tadić, V.; Zimmer, D.; Duvnjak, V. Noise in the Cabin of Agricultural Tractors. Teh. Vjesn. - Tech. Gaz. 2018, 25, 1611–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Shepard, “A two-dimensional interpolation for irregularly-spaced data function”.

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; Volume 445, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1. 0 Contributors. SciPy 1.0 Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, C.M.A.; Junior, G.M.; Da Silva, R.R.; Rafull, L.Z.L.; Orlando, R.C.; Ale, L.P. Occupational noise level exposures outside and inside agricultural tractor cabs. 2023; 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Canada, “Evaluation the vibration and noise level emitted by a tractor Written for presentation at the 2014 ASABE and CSBE/SCGAB Annual International Meeting Sponsored by ASABE”.

- Avaliação dos níveis de ruído em tratores agrícolas e seus efeitos sobre o operador,” Aleph, Dec. 1991, Accessed: Sep. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://repositorioslatinoamericanos.uchile.cl/handle/2250/2579014.

- Y. J. Park and K. U. Kim, “Reduction of rattle noise of a direct engine-pto driveline of agricultural tractors: part iii. reduction of pto rattle noise by a torsional damper,” Trans ASABE, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 369–374.

- Camargo, D.A.; Munis, R.A.; Miyajima, R.H.; Lima, R.C.A.; Simões, D. An evaluation of machine operator exposure to occupational noise during harvesting and extraction operations in Brazilian eucalyptus plantations. Int. J. For. Eng. 2022, 34, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleed, M.; Um, T.-W.; Kamal, T.; Usman, S.M. Classification of Agriculture Farm Machinery Using Machine Learning and Internet of Things. Symmetry 2021, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Zarnaq, M.; Omid, M.; Biabani-Aghdam, E. Fault diagnosis of tractor auxiliary gearbox using vibration analysis and random forest classifier. Inf. Process. Agric. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

| Tractor | Cabin | Traction | Power (kW) | Nominal RPM | Hour Meter |

| T1 | No | Single traction | 65.4 | 2500 | 430 |

| T2 | Yes | Power-assisted traction | 73 | 2300 | 30 |

| T3 | No | Assisted traction | 59.65 | 2300 | 50 |

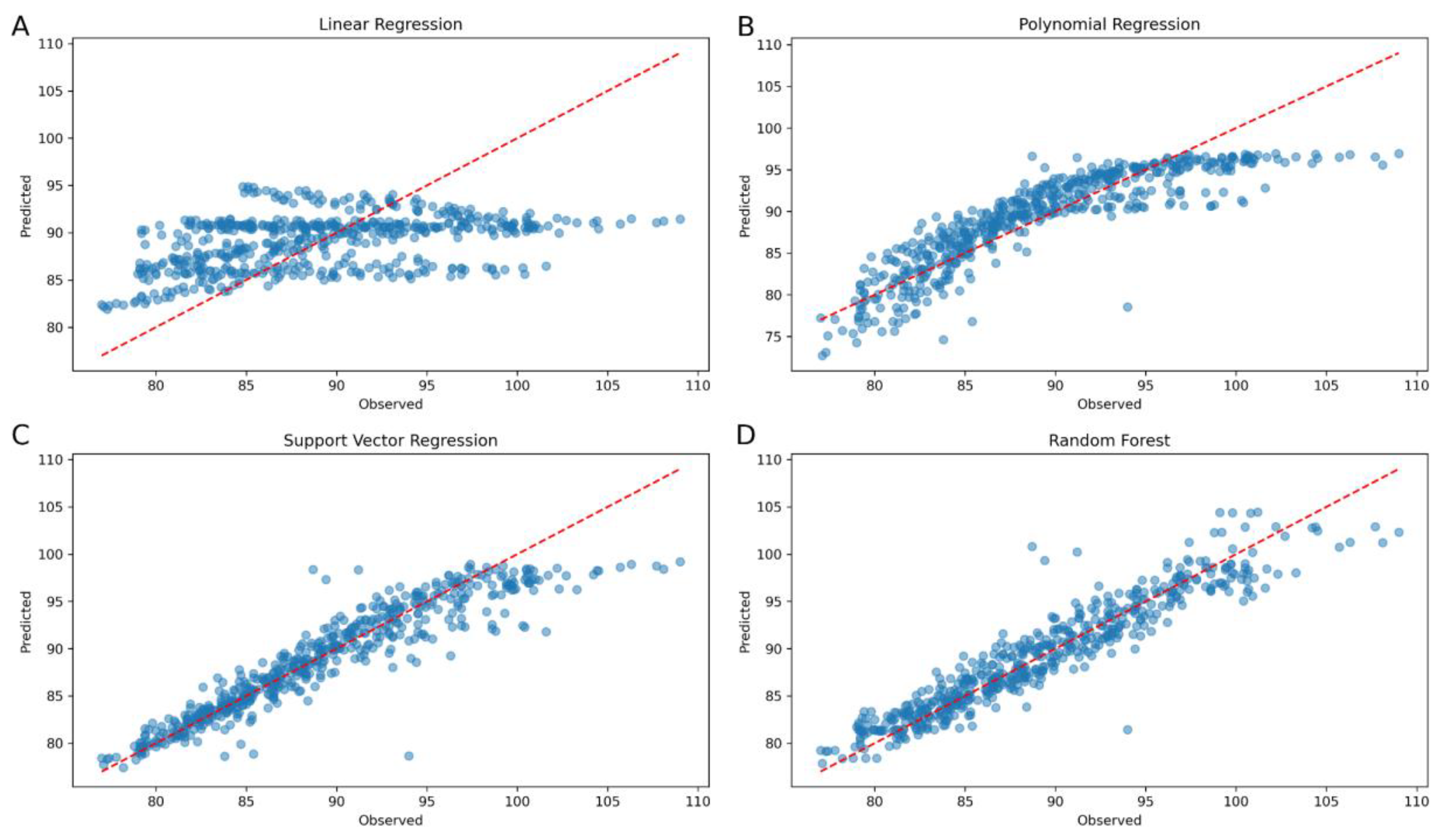

| Training | Testing | |||

| Model | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 |

| LR | 5.71 (± 0.032) | 0.19 (± 0.008) | 5.77 (± 0.135) | 0.17 (± 0.031) |

| PR | 3.03 (± 0.028) | 0.77 (± 0.005) | 3.09 (± 0.107) | 0.76 (± 0.016) |

| RF | 1.56 (± 0.172) | 0.94 (± 0.013) | 2.06 (± 0.281) | 0.89 (± 0.030) |

| SVR | 2.18 (± 0.225) | 0.88 (± 0.025) | 2.28 (± 0.297) | 0.87 (± 0.035) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).