Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

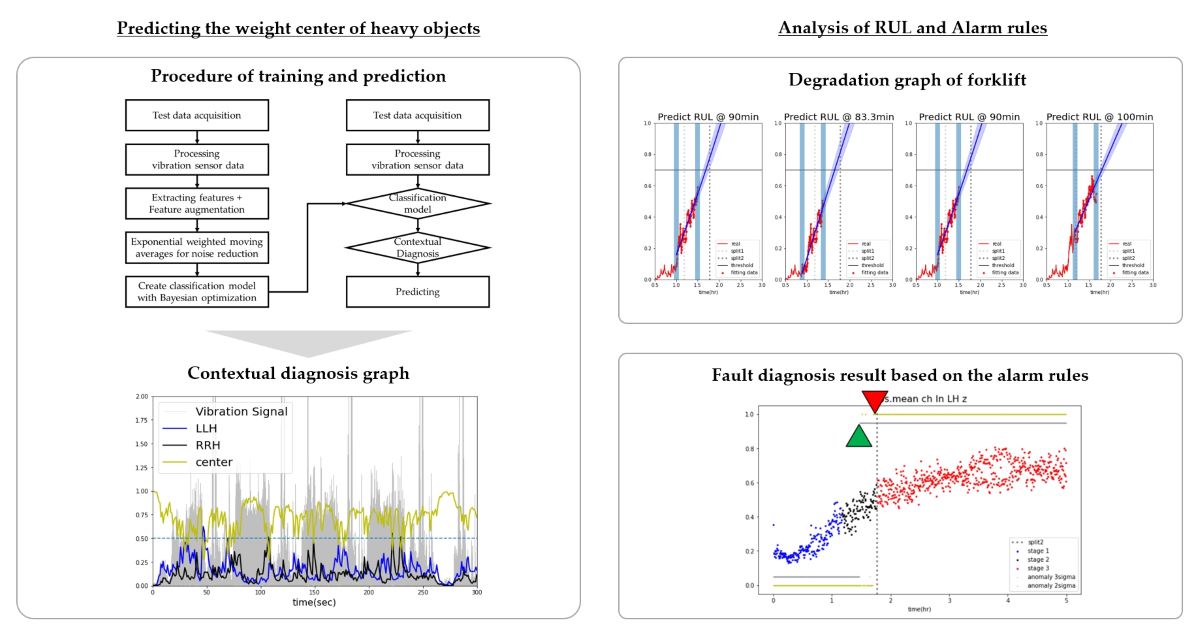

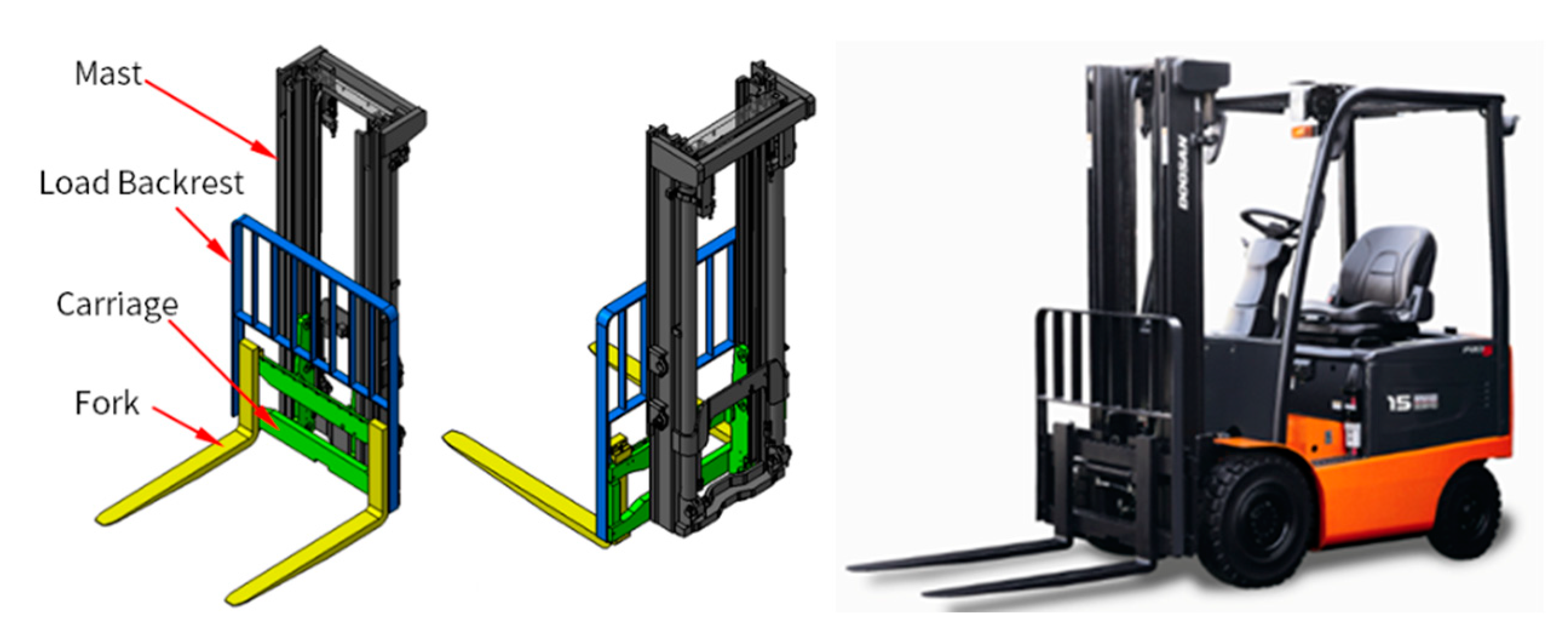

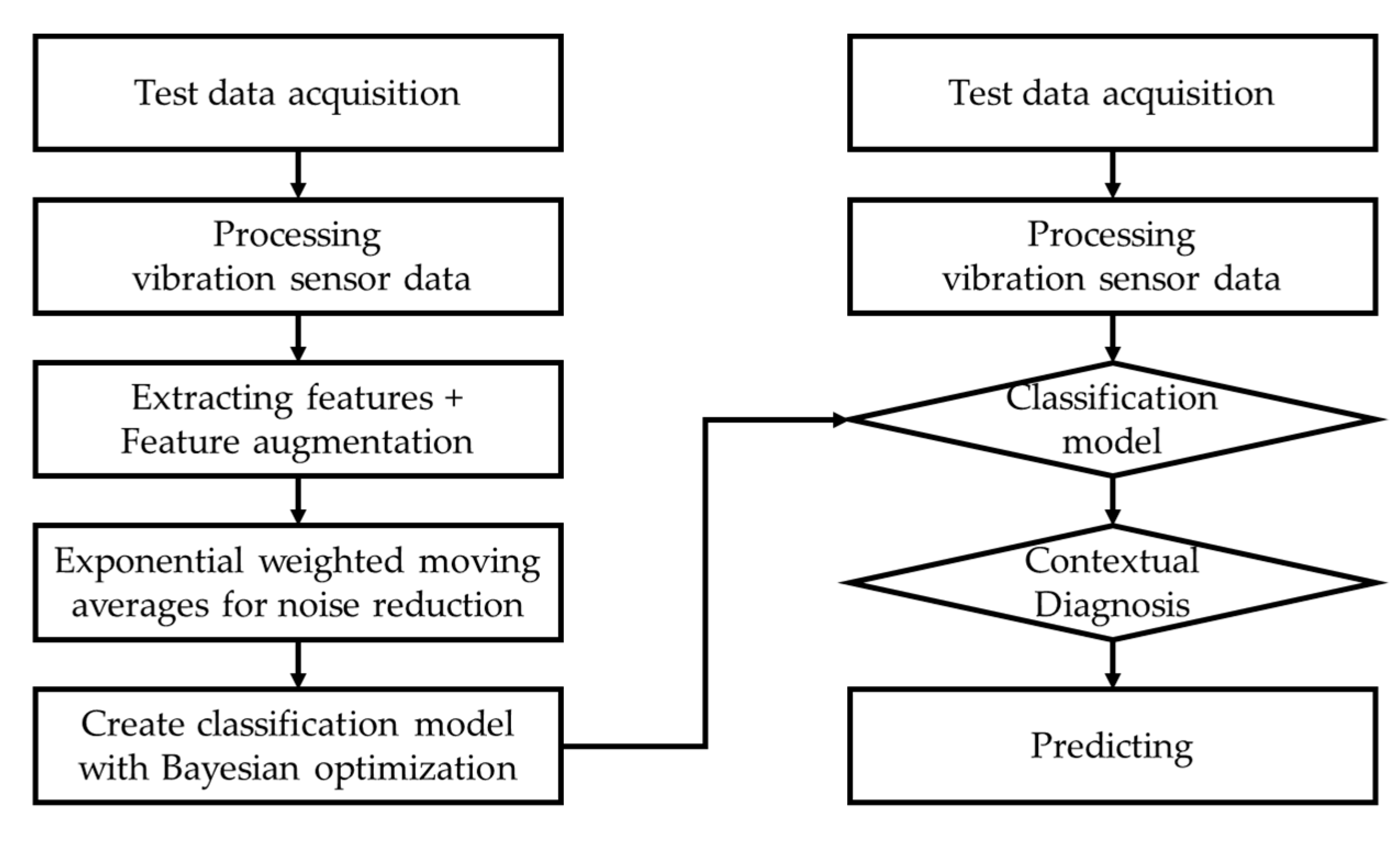

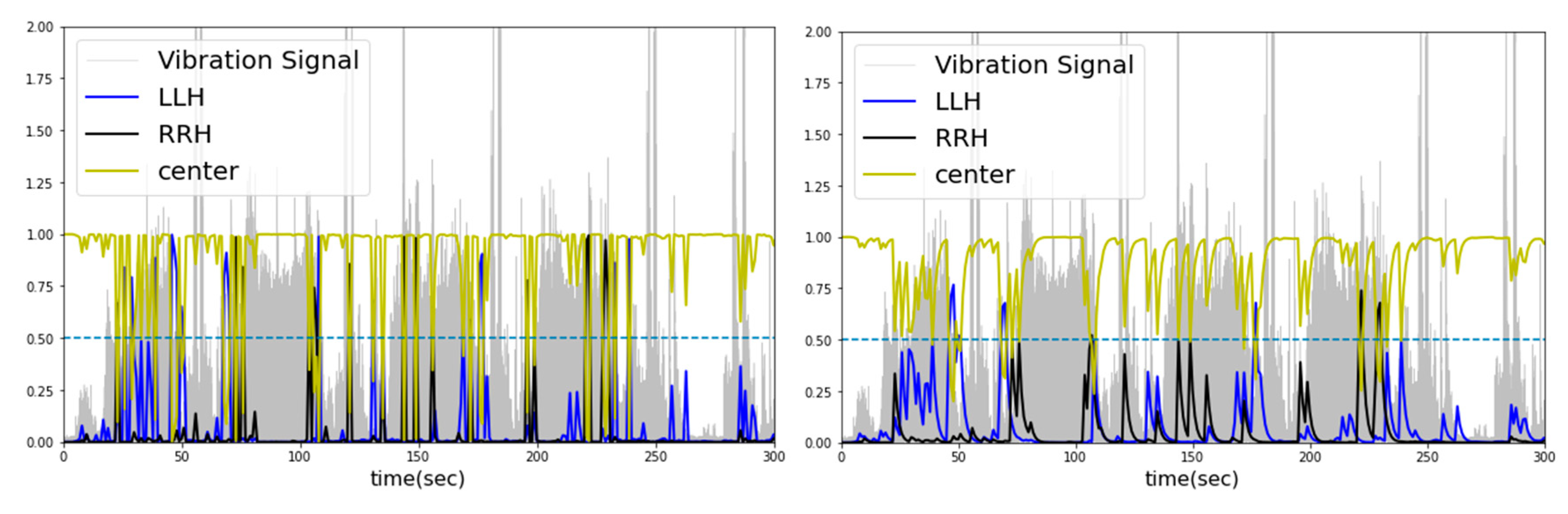

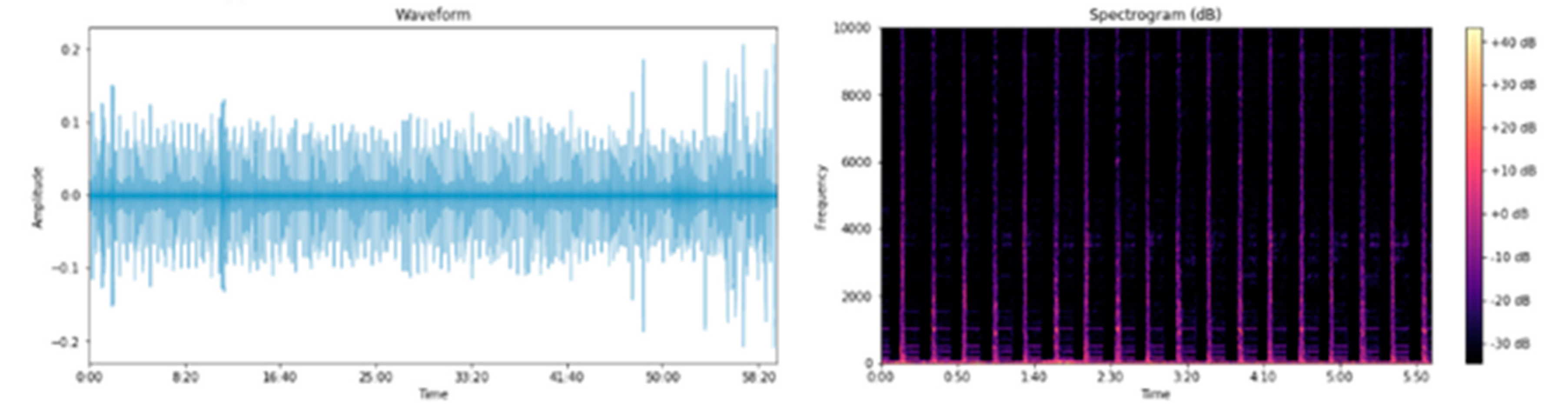

2. Diagnosing and classifying the weight center of heavy objects carried by forklifts

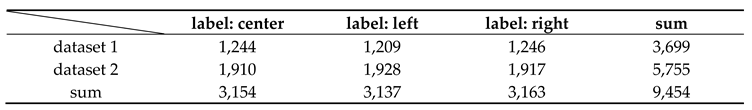

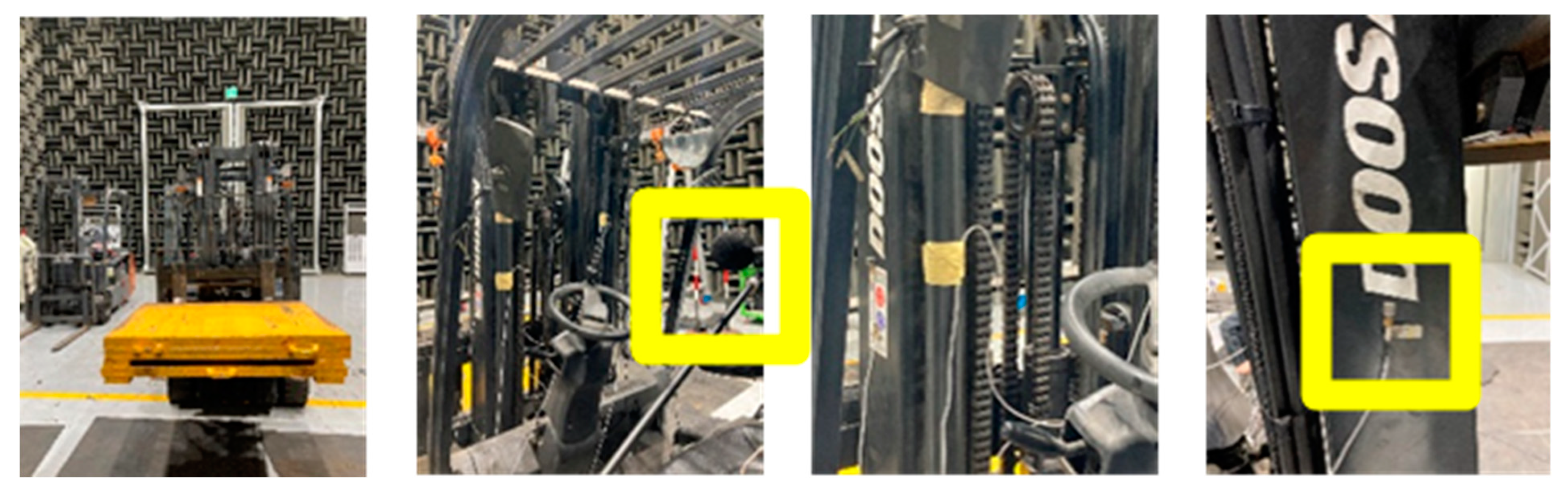

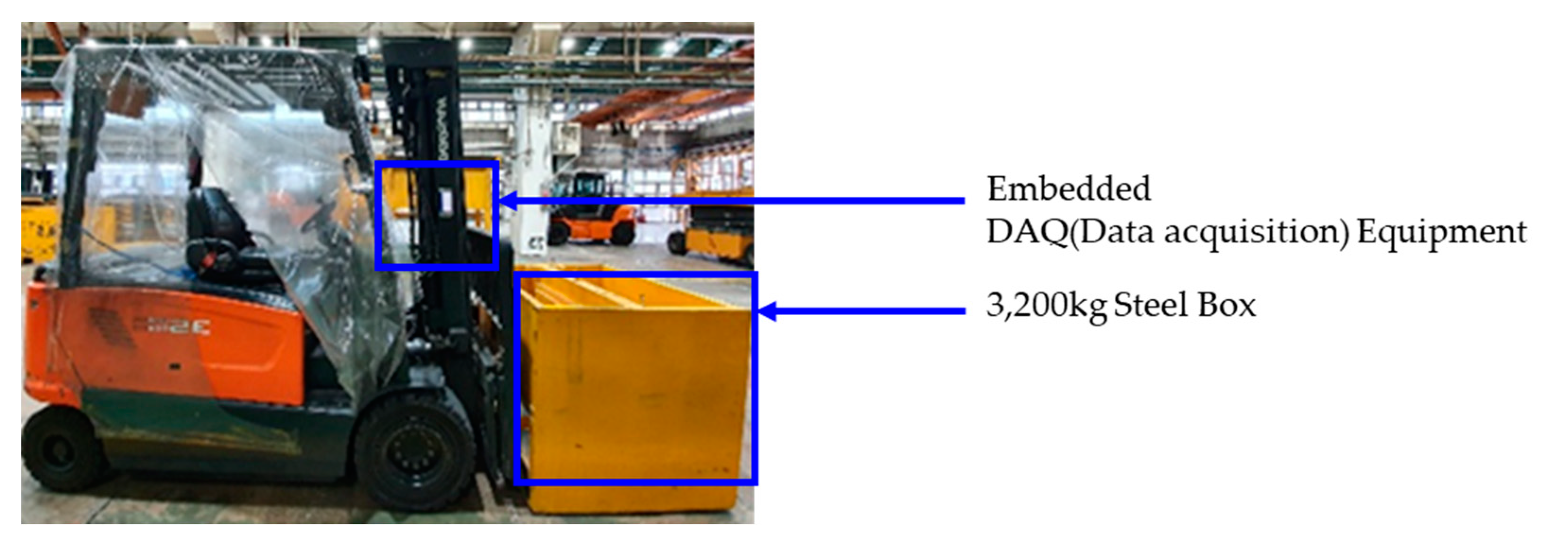

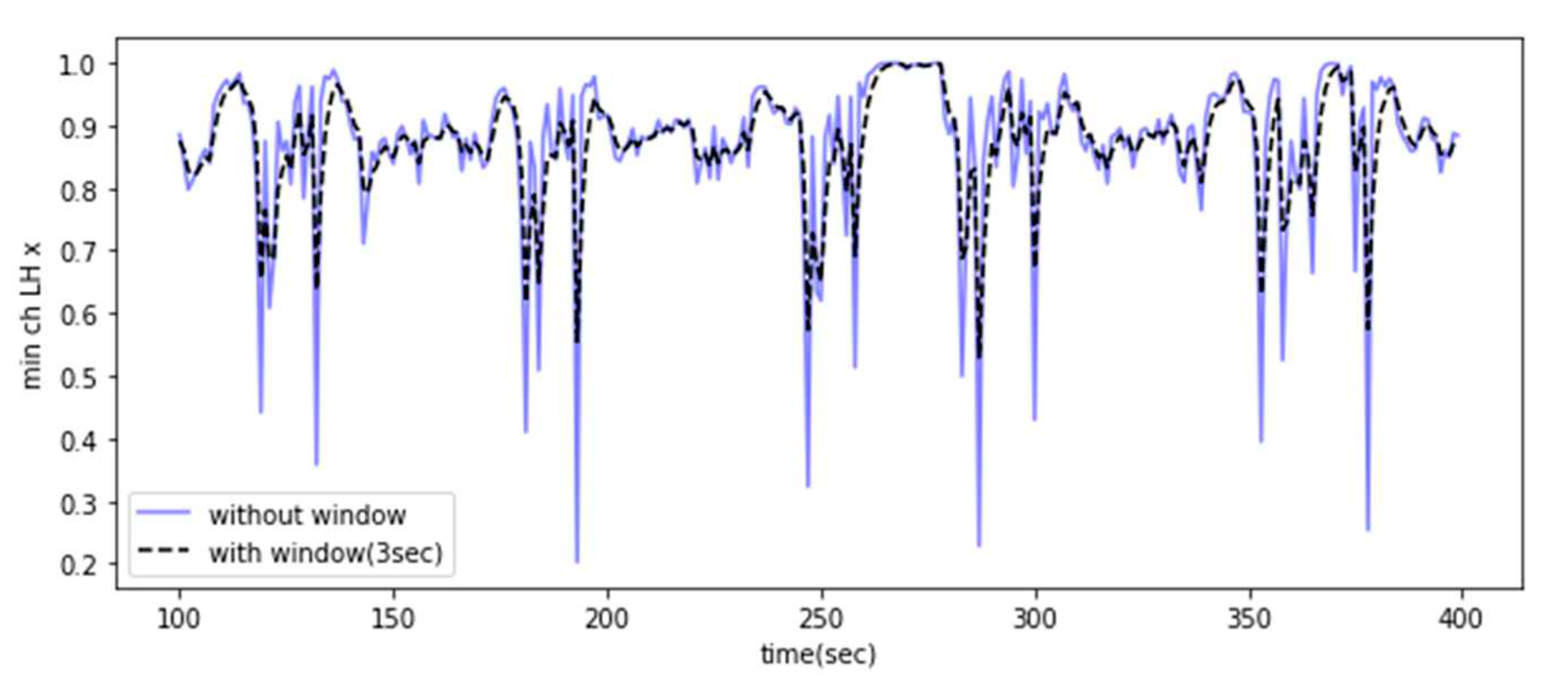

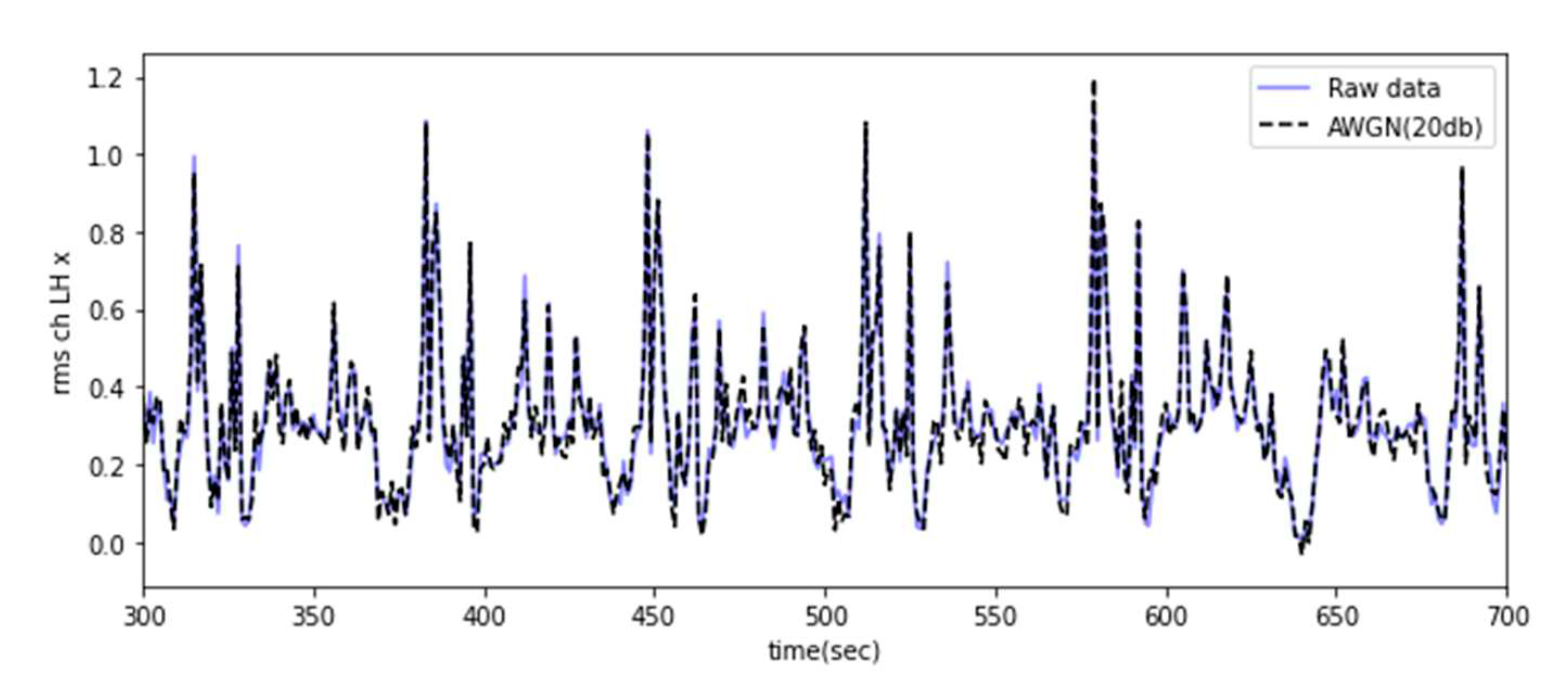

2.1. Experimental data acquisition and feature engineering

| features | feature vectors without exponentially weighted window | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | … | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | … | m | ||

| Min | . | … | 0.885433 | 0.843096 | 0.797650 | 0.811161 | 0.827289 | … | . | |

| Max | . | … | 0.078264 | 0.080768 | 0.106396 | 0.108621 | 0.116061 | … | . | |

| Peak to Peak | . | … | 0.093902 | 0.112324 | 0.146313 | 0.142308 | 0.140491 | … | . | |

| Mean(abs) | . | … | 0.351697 | 0.401478 | 0.407600 | 0.368202 | 0.429075 | … | . | |

| RMS | . | … | 0.267110 | 0.309412 | 0.318085 | 0.291022 | 0.342365 | … | . | |

| Variance | . | … | 0.073500 | 0.098043 | 0.103476 | 0.086930 | 0.119690 | … | . | |

| Kurtosis | . | … | 0.004885 | 0.008043 | 0.011320 | 0.016485 | 0.014369 | … | . | |

| Skewness | . | … | 0.477752 | 0.469798 | 0.491220 | 0.486768 | 0.492277 | … | . | |

| Crest Factor | . | … | 0.064416 | 0.039363 | 0.096850 | 0.127109 | 0.100406 | … | . | |

| Shape Factor | . | … | 0.049605 | 0.060854 | 0.070667 | 0.080790 | 0.088413 | … | . | |

| Impulse Factor | . | … | 0.033882 | 0.023190 | 0.053079 | 0.070003 | 0.057815 | … | . | |

| Margin Factor | . | … | 0.003583 | 0.002052 | 0.003671 | 0.005534 | 0.003556 | … | . | |

| features | feature vectors with exponentially weighted window(3sec) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | … | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | … | m | |

| Min | . | … | 0.875394 | 0.859245 | 0.828448 | 0.819804 | 0.823547 | … | . |

| Max | . | … | 0.076663 | 0.078716 | 0.092556 | 0.100588 | 0.108325 | … | . |

| Peak to Peak | . | … | 0.096910 | 0.104617 | 0.125465 | 0.133887 | 0.137189 | … | . |

| Mean(abs) | . | … | 0.365030 | 0.383254 | 0.395427 | 0.381814 | 0.405444 | … | . |

| RMS | . | … | 0.276765 | 0.293089 | 0.305587 | 0.298304 | 0.320335 | … | . |

| Variance | . | … | 0.079095 | 0.088569 | 0.096022 | 0.091476 | 0.105583 | … | . |

| Kurtosis | . | … | 0.005647 | 0.006845 | 0.009082 | 0.012784 | 0.013576 | … | . |

| Skewness | . | … | 0.479047 | 0.474423 | 0.482821 | 0.484795 | 0.488536 | … | . |

| Crest Factor | . | … | 0.052390 | 0.045876 | 0.071363 | 0.099236 | 0.099821 | … | . |

| Shape Factor | . | … | 0.048446 | 0.054650 | 0.062658 | 0.071724 | 0.080069 | … | . |

| Impulse Factor | . | … | 0.027911 | 0.025551 | 0.039315 | 0.054659 | 0.056237 | … | . |

| Margin Factor | . | … | 0.002978 | 0.002515 | 0.003093 | 0.004314 | 0.003935 | … | . |

| feature combination | The no. of training data | The no. of test data |

|---|---|---|

| 1. original | 6,617 | 2,837 |

| 2. original + LSTM AE | 13,234 | 2,837 |

| 3. original + AWGN | 13,234 | 2,837 |

| 4. original + LSTM AE +AWGN | 19,851 | 2,837 |

2.2. Classification result

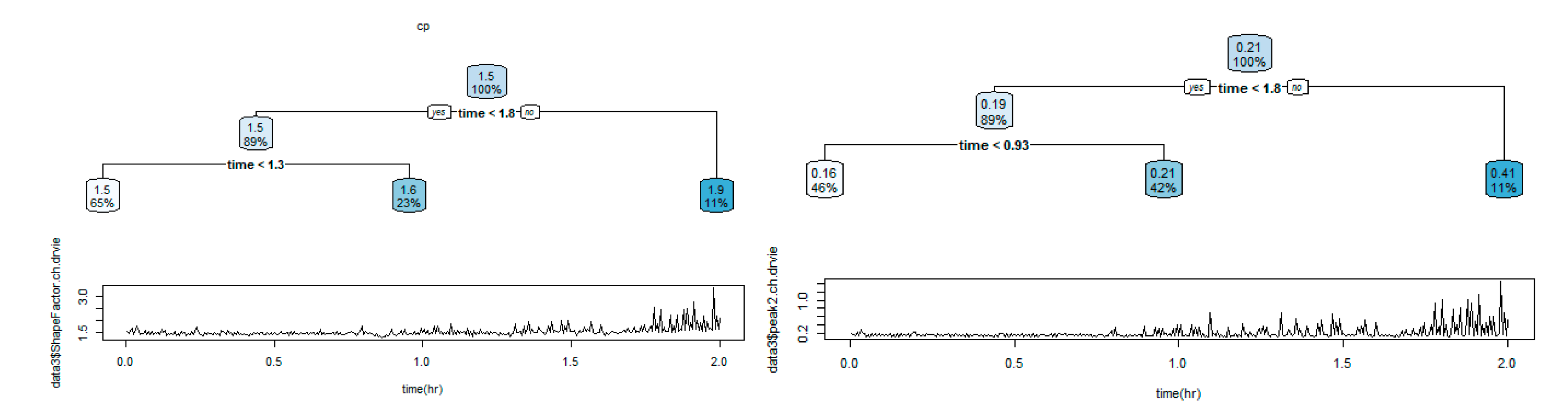

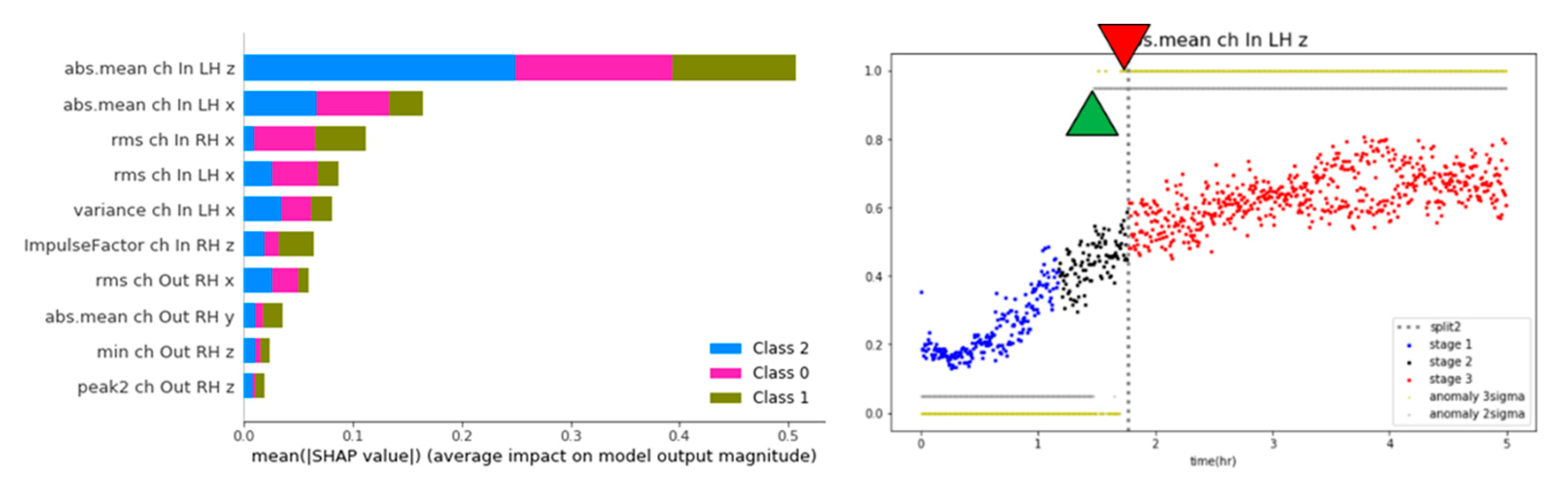

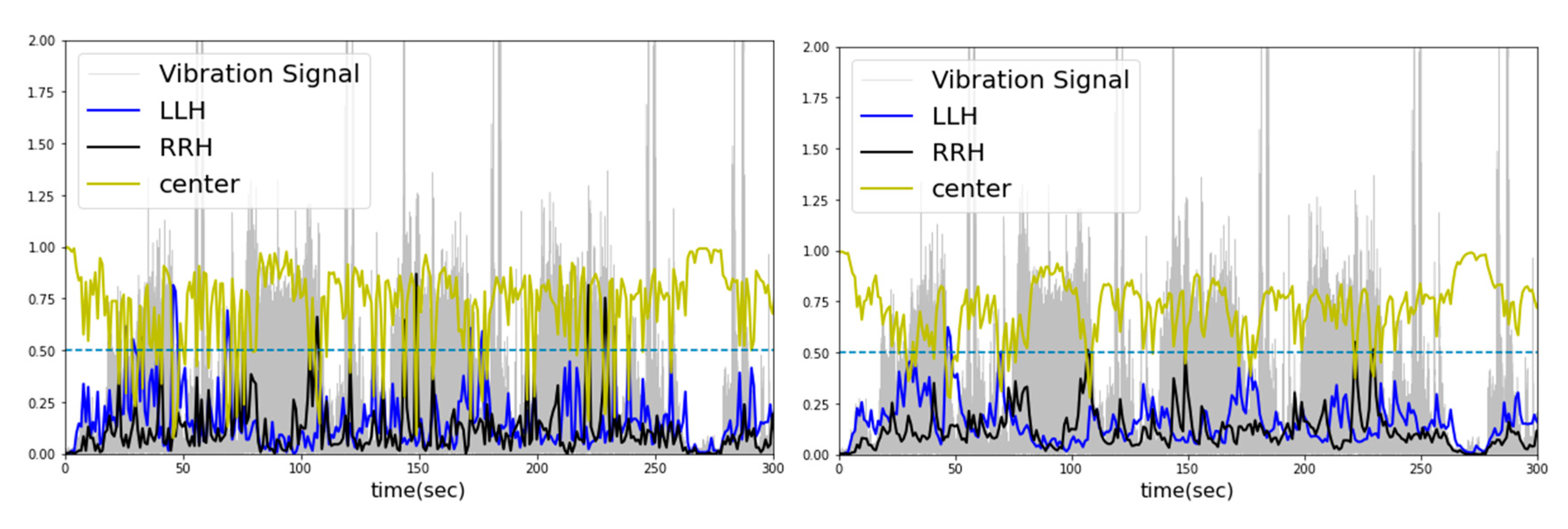

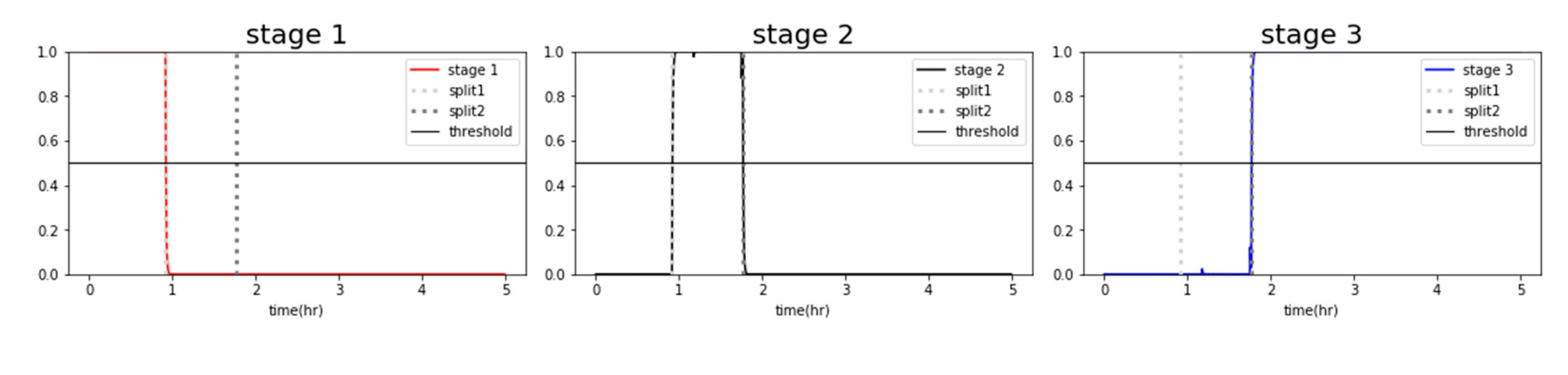

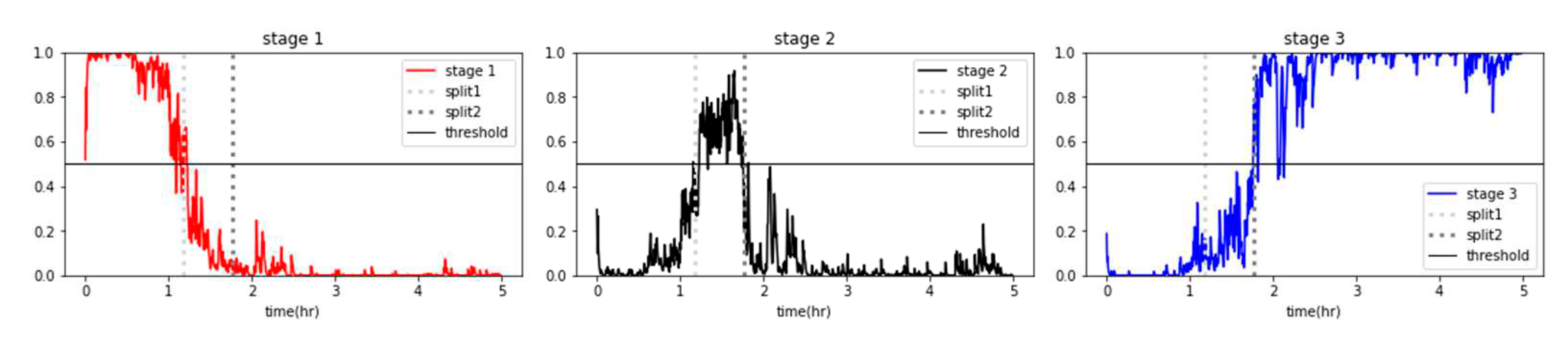

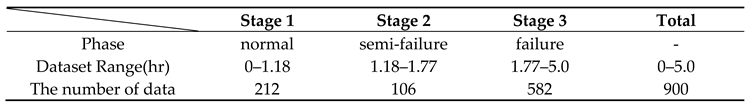

3. Abnormal lifting weight stage classification

3.1. Experimental data acquisition and feature engineering

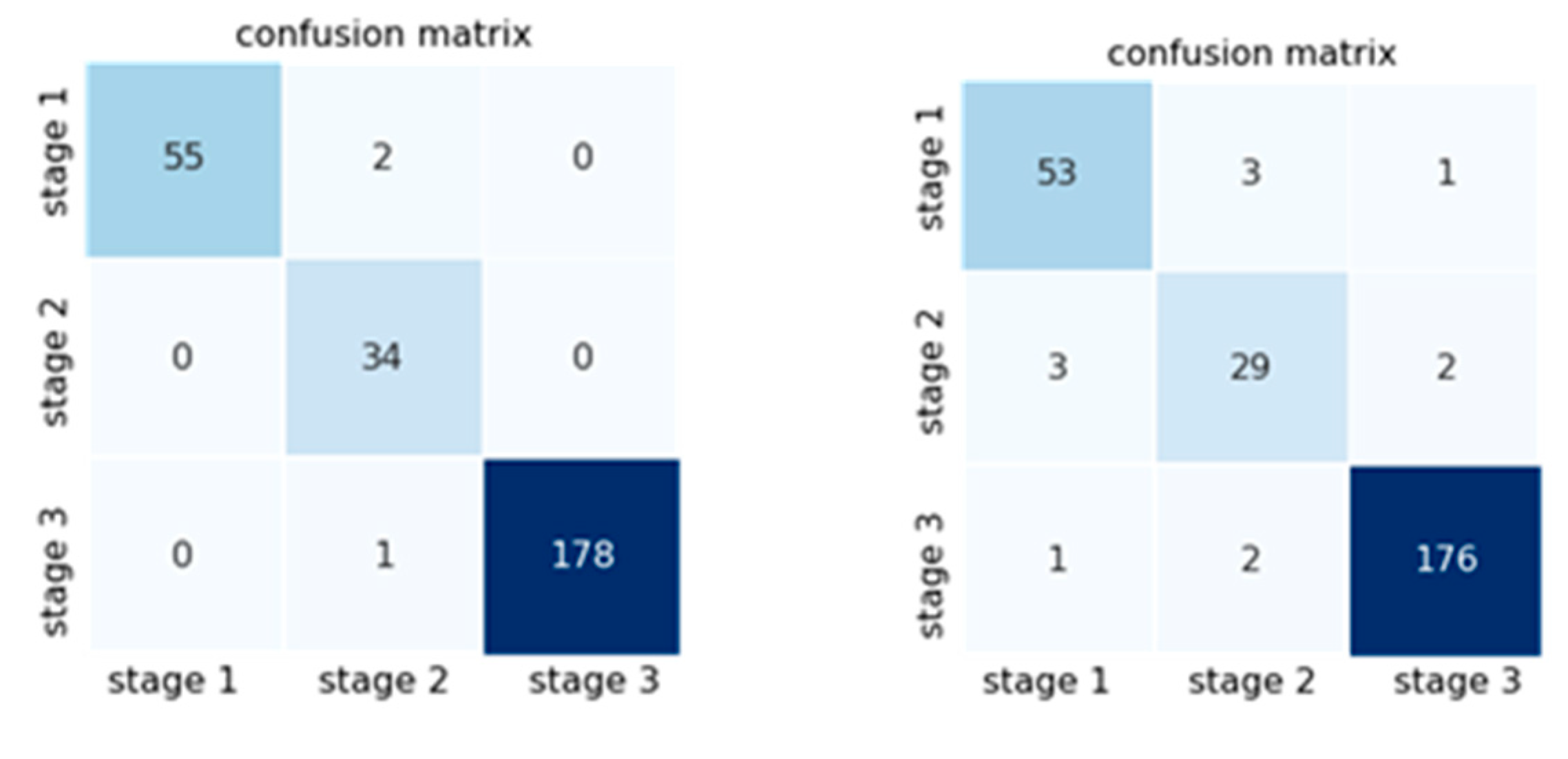

3.2. Stage classification result

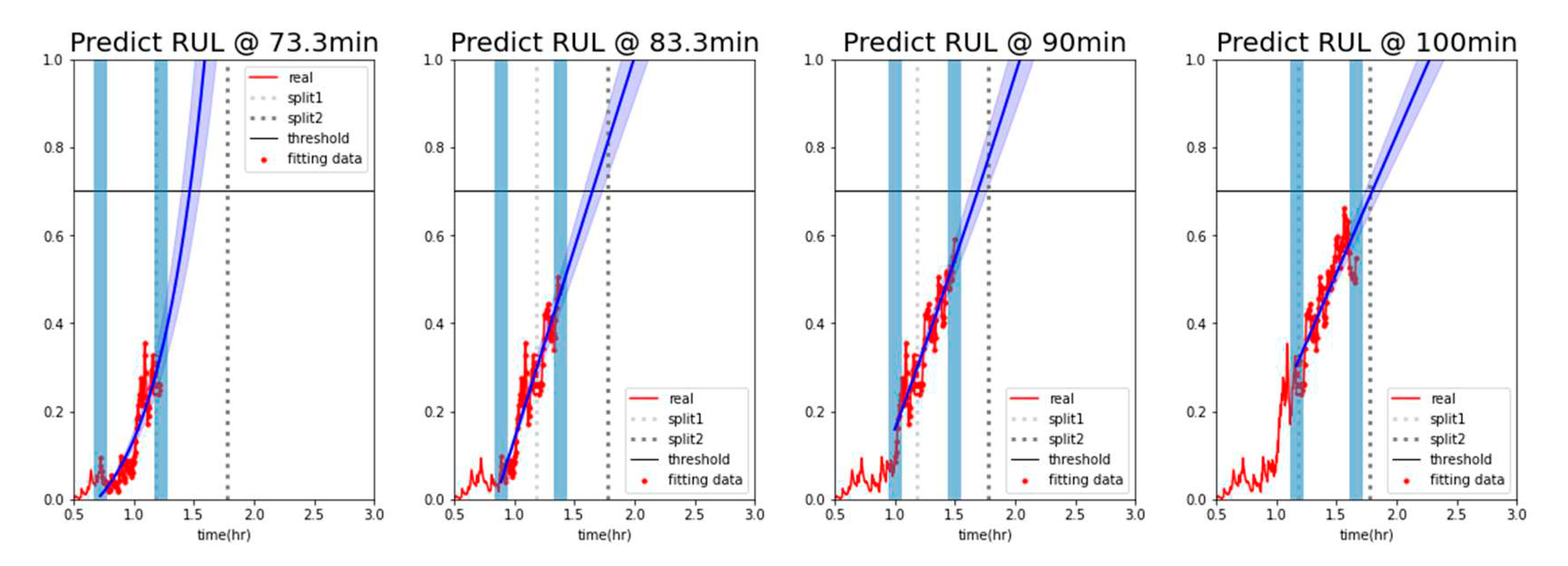

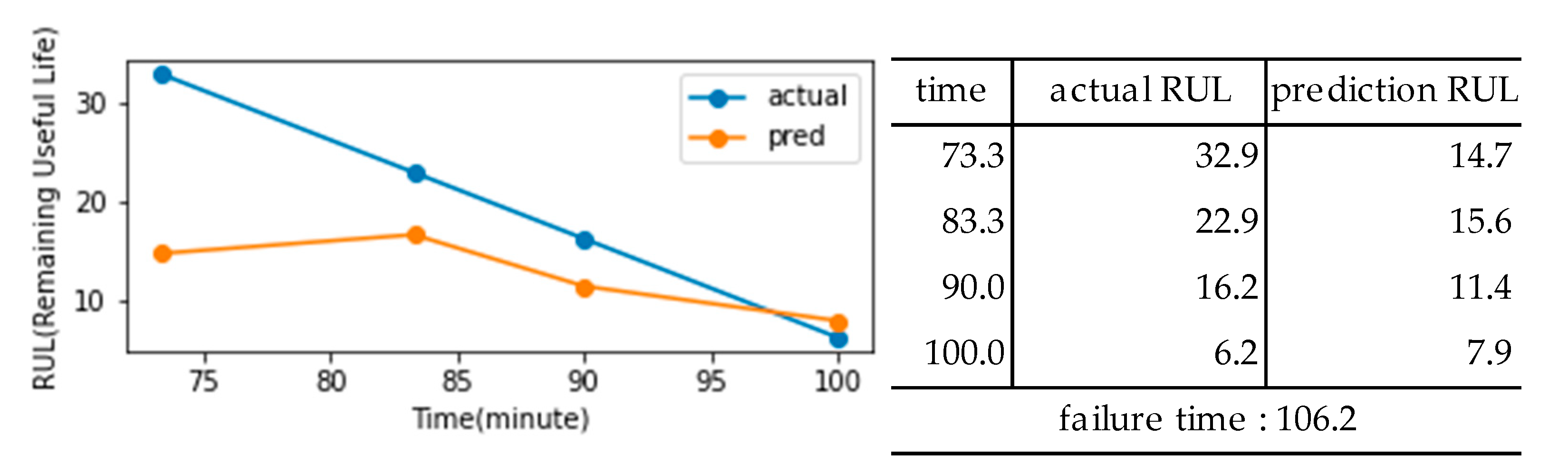

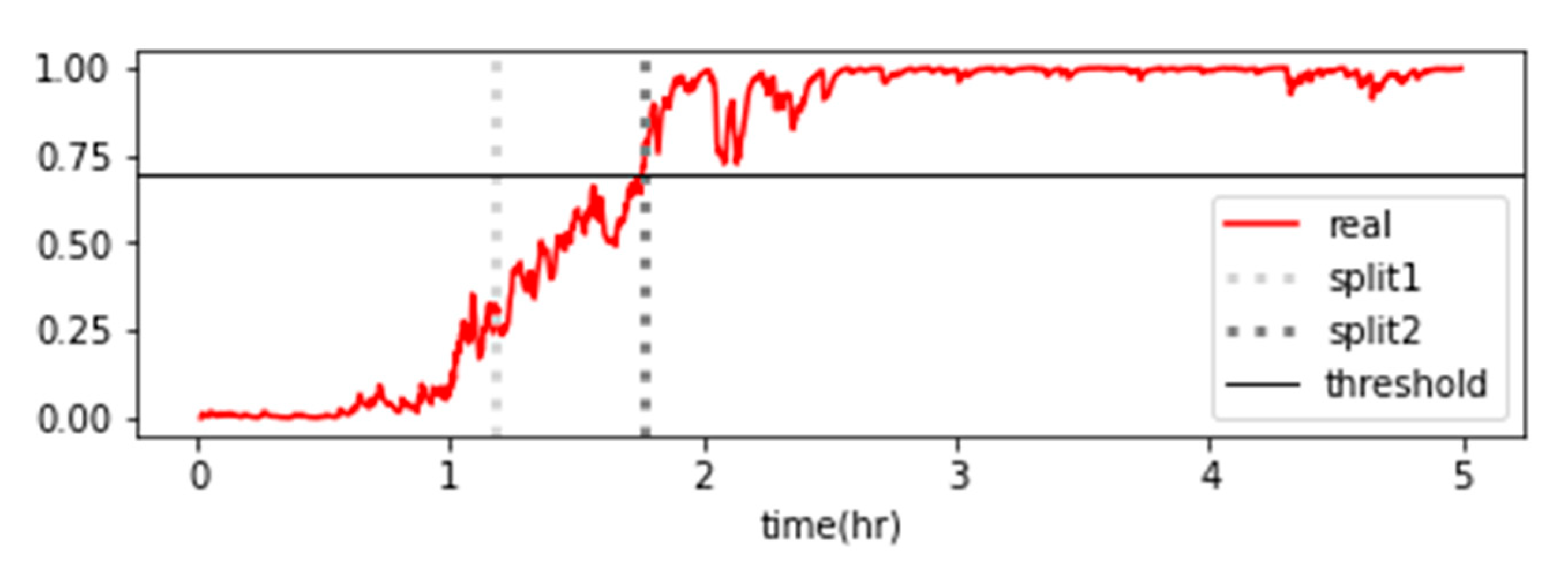

4. RUL analysis and alarm rule fault diagnosis in abnormal lifting due to unbalanced load

4.1. Generation of the life prediction model and verification of RUL

4.2. Alarm rule-based fault diagnosis

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsui, K.L.; Chen, N.; Zhou, Q.; Hai, Y.; Wang, W. Prognostics and Health Management: A Review on Data Driven Approaches. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. , Wu, F., Zhao, W., Ghaffari, M., Liao, L., & Siegel, D. Prognostics and health management design for rotary machinery systems—Reviews, methodology and applications. Mechanical systems and signal processing 2014, 42, 314–334. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.; Li, Y.-F. A review on prognostics and health management (PHM) methods of lithium-ion batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 116, 109405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, J.; Saidi, L.; Harrath, S.; Bechhoefer, E.; Benbouzid, M. Online automatic diagnosis of wind turbine bearings progressive degradations under real experimental conditions based on unsupervised machine learning. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 132, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, L.; Ali, J.B.; Bechhoefer, E.; Benbouzid, M. Wind turbine high-speed shaft bearings health prognosis through a spectral Kurtosis-derived indices and SVR. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 120, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.C. Forecasting seasonals and trends by exponentially weighted moving averages. Int. J. Forecast. 2004, 20, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J. S. The exponentially weighted moving average. Journal of quality technology, 1986, 18, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi, S. V. Advanced digital signal processing and noise reduction. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Aurélien, G. Hands-on machine learning with Scikit-learn, Keras, and TensorFlow. O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2022.

- Graves, A. Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Simard, P.; Frasconi, P. Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks 1994, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascanu, R. , Mikolov, T., & Bengio, Y. On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 1310-1318). Pmlr. 20 May.

- Hochreiter, S. The Vanishing Gradient Problem During Learning Recurrent Neural Nets and Problem Solutions. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl.-Based Syst. 1998, 6, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to Forget: Continual Prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Yue, J.; Rao, Y. A deep learning framework for financial time series using stacked autoencoders and long-short term memory. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0180944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning, 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G. , Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W.,... & Liu, T. Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2017, 30.

- Liang, W.; Luo, S.; Zhao, G.; Wu, H. Predicting Hard Rock Pillar Stability Using GBDT, XGBoost, and LightGBM Algorithms. Mathematics 2020, 8, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, S.; Rana, S.; Gupta, S.; Vellanki, P.; Venkatesh, S. Bayesian Optimization for Adaptive Experimental Design: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 13937–13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J. , Bardenet, R., Bengio, Y., & Kégl, B. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2011, 24.

- Singh, K. , & Upadhyaya, S. Outlier detection: applications and techniques. International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI), 2012, 9, 307. [Google Scholar]

- Weigend, A. S. , Mangeas, M., & Srivastava, A. N. Nonlinear gated experts for time series: Discovering regimes and avoiding overfitting. International journal of neural systems 1995, 6, 373–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y. , Lu, C. T., & Chen, April 2006., D. Spatial weighted outlier detection. In Proceedings of the 2006 SIAM international conference on data mining (pp. 614-618). Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Classification and regression trees. Routledge, 2017.

- Sokolova, M. , Japkowicz, N., & Szpakowicz, S. (2006). Beyond accuracy, F-score and ROC: a family of discriminant measures for performance evaluation. In AI 2006: Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 19th Australian Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Hobart, Australia, Proceedings 19 (pp. 1015-1021). Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 4-8 December 2006.

- Jeni, L. A. , Cohn, J. F., & De La Torre, F. Facing imbalanced data--recommendations for the use of performance metrics. In 2013 Humaine association conference on affective computing and intelligent interaction (pp. 245-251). IEEE, 2013. 20 September.

- Sun, Y., Wong, A. K., & Kamel, M. S. Classification of imbalanced data: A review. International journal of pattern recognition and artificial intelligence. 2009, 23, 687–719.

- Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Guchhait, P.K.; Banerjee, R.; Srivastava, A.K.; Vishwakarma, D.N.; Saket, R.K. A Comprehensive Review of Condition Based Prognostic Maintenance (CBPM) for Induction Motor. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 90690–90704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. M. , & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2017, 30.

| Crest factor | max/RMS |

| Shape factor | RMS/mean(abs) |

| Impulse factor | max/mean(abs) |

| Margin factor | max/mean(abs)2 |

| Before contextual diagnosis | After contextual diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| time | Left(LLH) | Right(RRH) | Center | time | Left(LLH) | Right(RRH) | Center |

| 1 | 0.00112 | 0.00014 | 0.99874 | 1 | 0.00112 | 0.00014 | 0.99874 |

| 2 | 0.00305 | 0.00044 | 0.99651 | 2 | 0.00241 | 0.00034 | 0.99725 |

| 3 | 0.00239 | 0.00070 | 0.99691 | 3 | 0.00240 | 0.00055 | 0.99706 |

| 4 | 0.00103 | 0.00012 | 0.99885 | 4 | 0.00167 | 0.00032 | 0.99801 |

| 5 | 0.00117 | 0.00022 | 0.99862 | 5 | 0.00141 | 0.00027 | 0.99832 |

| 6 | 0.02492 | 0.00198 | 0.97311 | 6 | 0.01335 | 0.00113 | 0.98552 |

| 7 | 0.06715 | 0.01467 | 0.91818 | 7 | 0.04046 | 0.00795 | 0.95158 |

| 8 | 0.06500 | 0.00303 | 0.93197 | 8 | 0.05278 | 0.00548 | 0.94174 |

| 9 | 0.13749 | 0.01739 | 0.84512 | 9 | 0.09522 | 0.01145 | 0.89333 |

| 10 | 0.07009 | 0.01556 | 0.91436 | 10 | 0.08264 | 0.01351 | 0.90385 |

| . | … | … | … | . | … | … | … |

| . | … | … | … | . | … | … | … |

| . | … | … | … | . | … | … | … |

| m | … | … | … | m | … | … | … |

| case no. | dataset | machine learning model |

feature moving average window size | smoothing factor(α) | contextual diagnosis accuracy score (probability moving average window size) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1sec | 2sec | 3sec | |||||

| case01 | raw feature | Random forest | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7522 | 0.8135 | 0.8950 |

| case02 | raw feature | Random forest | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.8019 | 0.8622 | 0.9186 |

| case03 | raw feature | Random forest | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8347 | 0.8752 | 0.9274 |

| case04 | with lstm ae feature | Random forest | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7392 | 0.8047 | 0.8904 |

| case05 | with lstm ae feature | Random forest | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.7846 | 0.8470 | 0.9094 |

| case06 | with lstm ae feature | Random forest | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8216 | 0.8713 | 0.9263 |

| case07 | with AWGN feature | Random forest | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7487 | 0.8238 | 0.9020 |

| case08 | with AWGN feature | Random forest | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.7994 | 0.8601 | 0.9203 |

| case09 | with AWGN feature | Random forest | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8294 | 0.8819 | 0.9366 |

| case10 | with all feature | Random forest | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7487 | 0.8587 | 0.9362 |

| case11 | with all feature | Random forest | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.8033 | 0.8897 | 0.9450 |

| case12 | with all feature | Random forest | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8305 | 0.9048 | 0.9563 |

| case13 | raw feature | lightGBM | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7659 | 0.8453 | 0.9295 |

| case14 | raw feature | lightGBM | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.8223 | 0.8858 | 0.9496 |

| case15 | raw feature | lightGBM | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8646 | 0.9129 | 0.9637 |

| case16 | with lstm ae feature | lightGBM | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7621 | 0.8347 | 0.9098 |

| case17 | with lstm ae feature | lightGBM | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.8160 | 0.8773 | 0.9369 |

| case18 | with lstm ae feature | lightGBM | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8488 | 0.9041 | 0.9521 |

| case19 | with AWGN feature | lightGBM | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7642 | 0.8421 | 0.9161 |

| case20 | with AWGN feature | lightGBM | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.8379 | 0.8925 | 0.9485 |

| case21 | with AWGN feature | lightGBM | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8643 | 0.9122 | 0.9591 |

| case22 | with all feature | lightGBM | 1 sec | 1.00 | 0.7638 | 0.8389 | 0.9221 |

| case23 | with all feature | lightGBM | 2 sec | 0.67 | 0.8206 | 0.8883 | 0.9454 |

| case24 | with all feature | lightGBM | 3 sec | 0.50 | 0.8569 | 0.9115 | 0.9566 |

| feature | breakpoint 1 | breakpoint 2 |

|---|---|---|

| max | 0.892 | 1.764 |

| min | 0.925 | 1.775 |

| peak2 | 0.925 | 1.775 |

| skewness | 1.308 | 1.831 |

| Crest Factor | 1.353 | 1.708 |

| Shape Factor | 1.308 | 1.775 |

| Impulse Factor | 1.353 | 1.764 |

| Margin Factor | 1.353 | 1.775 |

| average | 1.177 | 1.771 |

| Model | Dataset | Accuracy | F1 Score | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (weighted) | (macro) | |||

| Logistic Regression |

Case 1(vibration feature) | 0.9815 | 0.9814 | 0.9599 |

| Case 2(vibration+sound feature) | 0.9889 | 0.9891 | 0.9790 | |

| Random Forest |

Case 1(vibration feature) | 0.9519 | 0.9523 | 0.9116 |

| Case 2(vibration+sound feature) | 0.9556 | 0.9556 | 0.9220 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).