1. Introduction

Second harmonic generation (SHG) at frequency

has been initially investigated in case of an electromagnetic wave of frequency

interacting with molecular dipoles, lacking inversion symmetry, but such that the energy difference between the electronic ground- and excited states, making up each dipole, is close to

[

1]. Therefore subsequent observation of SHG, over a

broad frequency range, in bulk materials displaying conversely

inversion symmetry[

2,

3] or at their surface [

4,

5], for which the incident light was coupled with

valence and conduction electrons rather than molecules, was bound to require new interpretations. The corresponding hydrodynamic and quantum arguments were further extended to account tentatively for SHG data, measured in metallic samples [

6,

7,

8] of nanometric (

nm) dimension. Remarkably those various explanations shared a common feature, since all of them dealt with conduction electrons coupled with an electromagnetic field [

2,

3,

4,

9,

10,

11], obeying Maxwell’s equations [

12] and thence

not allowing for 3-dimensional space-charge for some reason to be developed in the conclusion. Therefore this work is aimed at devising the

first theory of space-charge waves in conducting materials. Its potential will then be illustrated by investigating SHG induced in samples of nanometric length. As a matter of fact SHG will turn out to stem from the

quadratic term, showing up in the expressions of the

drift current and the

polarisation of conduction electrons. Actually

space-charge solitons have already been invoked to account for the Gunn effect [

13] and acousto-electric instabilities observed in piezoelectric semi-conductors [

14,

15], but the corresponding theoretical treatments were empirical, which prevented any conclusive statement regarding their validity. By contrast, the self-consistent analysis, laid out below, yields the

explicit dependence of the SHG signal on the sample length, electron concentration and frequency

for the sake of comparison with measurements.

The outline is as follows : the dispersion curve of space-charge waves will be worked out in section 1 with help of Newton and Gauss’ equations and the charge conservation law, whereas section 2 will deal with the procedure permitting to match together an electromagnetic wave with a space-charge one of same frequency; SHG will be analysed in section 3, while the main results will be summarised in the conclusion.

2. 1-Dispersion Curve

Though various geometrical shapes, such as silver-coated nanocones and bowtie antennas [

6], gold nanospheres [

7] and V-groove nanoparticle [

8], have been discussed by other authors, we shall focus for simplicity upon the wire, sketched in

Figure 1, containing conduction electrons of charge

e, effective mass

m and concentration

and located in a cylindrical frame

. It is assumed to sustain a wave, travelling along the

z axis and conveying an electric field

E,

parallel to the

z direction and taken to read

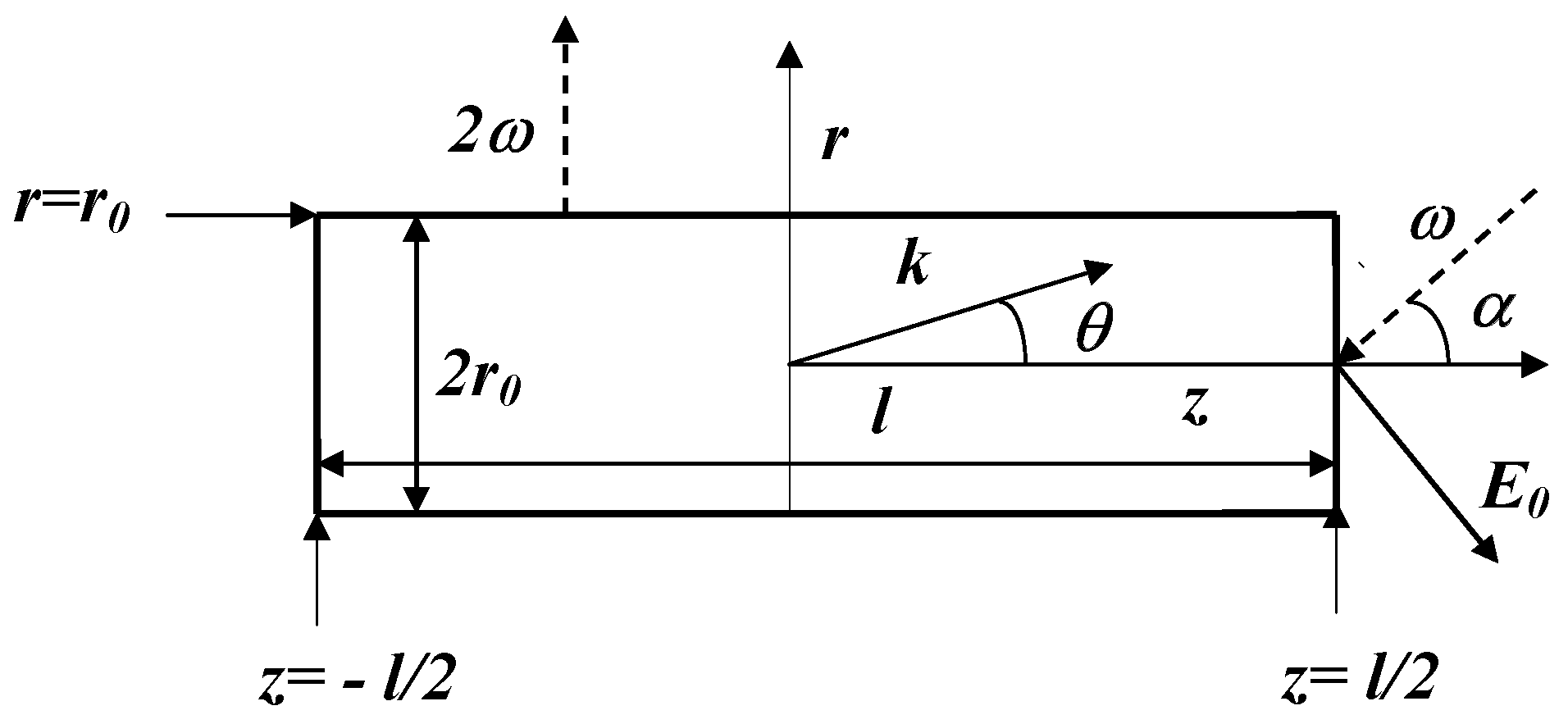

Figure 1.

Cross section of a cylindrical wire of length l and radius in the plane; the dashed lines labelled designate respectively the incoming electromagnetic wave of frequency , making an angle with the z direction, and the outgoing one of frequency , parallel to the radial axis; the solid lines labelled k, refer, respectively, to a one-electron wave-vector, making an angle with the z direction and the electric field carried along by the incoming wave.

Figure 1.

Cross section of a cylindrical wire of length l and radius in the plane; the dashed lines labelled designate respectively the incoming electromagnetic wave of frequency , making an angle with the z direction, and the outgoing one of frequency , parallel to the radial axis; the solid lines labelled k, refer, respectively, to a one-electron wave-vector, making an angle with the z direction and the electric field carried along by the incoming wave.

with

t standing for time,

x being the coordinate along the

radial axis and the complex unknowns

to be assigned below. The field

E sets the electrons in motion in compliance with Newton’s law as

with

designating the displacement coordinate of the electron mass center,

parallel to the

z axis, Drude’s collision time [

12,

16], the

z-

dependent pressure and electron concentration, respectively. In addition to the usual inertial

, electrostatic

and friction

terms [

12,

16], Equation (

1) is seen to display a pressure induced force

to be derived now.

To that end, let us begin with writing the expression of the force

exerted by

p upon a cylinder of axis

z, length

, section

, containing thence

of electrons

Then

showing up in the right-hand side of Equation (

1), is identified as the force exerted on a

single electron. The expression of

will be worked out now by resorting to usual thermodynamical definitions [

16,

17], while assuming a

unique temperature

T all over the wire

with

referring to a small volume, containing

of electrons

,

local Helmholz free energy per unit-volume, Fermi energy, known as the chemical potential of independent electrons and space-charge density

, respectively. Thus the pressure gradient

is realized to ensue from the finite space-charge density

. Note also that the macroscopic pressure

p is unrelated to the so called

quantum pressure, considered by other authors [

4,

9,

10].

Besides, the field

E induces [

12,

16,

18] a dielectric displacement

D, parallel to the

z direction

with

referring to the vacuum permittivity. Noteworthy is that the polarisation term

(

n stands for the refractive index), originating from the

filled bands and contributing to

in the Ampère-Maxwell equation, is

lacking in Equation (

2), because the corresponding electrons contribute

nothing to

. Linearising further

D by dropping

in Equation (

2)

and Fourier transforming it with respect to

t yields

The space-charge density

is given by Gauss’ equation [

18], reading in this unidimensional analysis as

At last substituting

to

in Equation (

1) and Fourier transforming the resulting expression with respect to

, while taking advantage of Equation (

4), gives

Thus combining Equations (

3,

5) together is seen to make up a

Cramer system in terms of the unknowns

, to be solved as

with

being the plasma frequency [

12]. Those expressions of

are seen to be quite different from the corresponding formulae, valid for an electromagnetic wave [

12] which can be deduced from Equation (

1), after deleting

, as

The charge conservation law [

18] can be recast, by taking advantage of Equation (

4) while assuming

, as

Comparing Equation (

8) with the Ampère-Maxwell equation [

12] enables one to realise that the space-charge wave conveys

no magnetic field, unlike electromagnetic waves.

The current density in Equation (

8) is defined as

with

referring to the

drift[

12,

16] and

diffusion[

13,

14,

15] components, respectively, both flowing along the

z axis. They read [

13,

14,

15,

16]

with

being a diffusion coefficient [

13,

14,

15]. Linearising

by dropping

in Equation (

9) and Fourier transforming the resulting expression of

with respect to

t and that of

with respect to

z lead to

with

standing for Drude’s conductivity [

12,

16] and

B given by Equation (

6). The expression of

in Equation (

10) is to be compared with that of a current

, aroused by an electromagnetic wave and obeying thence Ohm’s law [

12,

16]

At last, Fourier transforming the charge conservation law in Equation (

8) with respect to

, while taking advantage of Equations (

6,

10), yields eventually the dispersion relation

as

Explicit expressions are needed now for

. To that end, the set of conduction electrons is assumed to make up an isotropic, 3-dimensional Fermi gas, either degenerate (metal) or not (semi-conductor). The one-electron energy

and the corresponding density of states

read in both cases

wherein

and

are defined in the caption of

Figure 1. Moreover the origin of energy

is taken at the bottom of the conduction band. Due to the electron velocity being equal to

, each electron contributes

to

with

being the Fermi-Dirac distribution [

16], whereas

refer, respectively, to Boltzmann’s constant and the mean free path, projected onto the

z axis. Remarkably the conduction electrons are to be described below as a Fermi gas at

local thermal equilibrium, characterised by a

uniqueT, yet

zdependent. The diffusion current density

is then obtained by integrating

over

in reciprocal space

with

being the radius of the spherical Brillouin zone and

standing for the volume of the unit-cell, accommodating at most 2 electrons. Hence

is inferred to be the upper bound of the conduction band. After integration with respect to

, Equation (

14) is recast into

Note that

entails

. The calculation of

proceeds differently for a metal or a semi-conductor.

Since the

T dependence of

is negligible [

16] in a metal up to room temperature, the calculation of

will be made at

, which yields

by assuming a half-filled band

. Performing further the integration in Equation (

15) owing to Sommerfeld’s expansion [

16] gives eventually

By contrast, the conduction electron properties prove strongly

T-dependent in semi-conductors [

16], which implies near room temperature

for which

designates the donor concentration. At last

is inferred to read

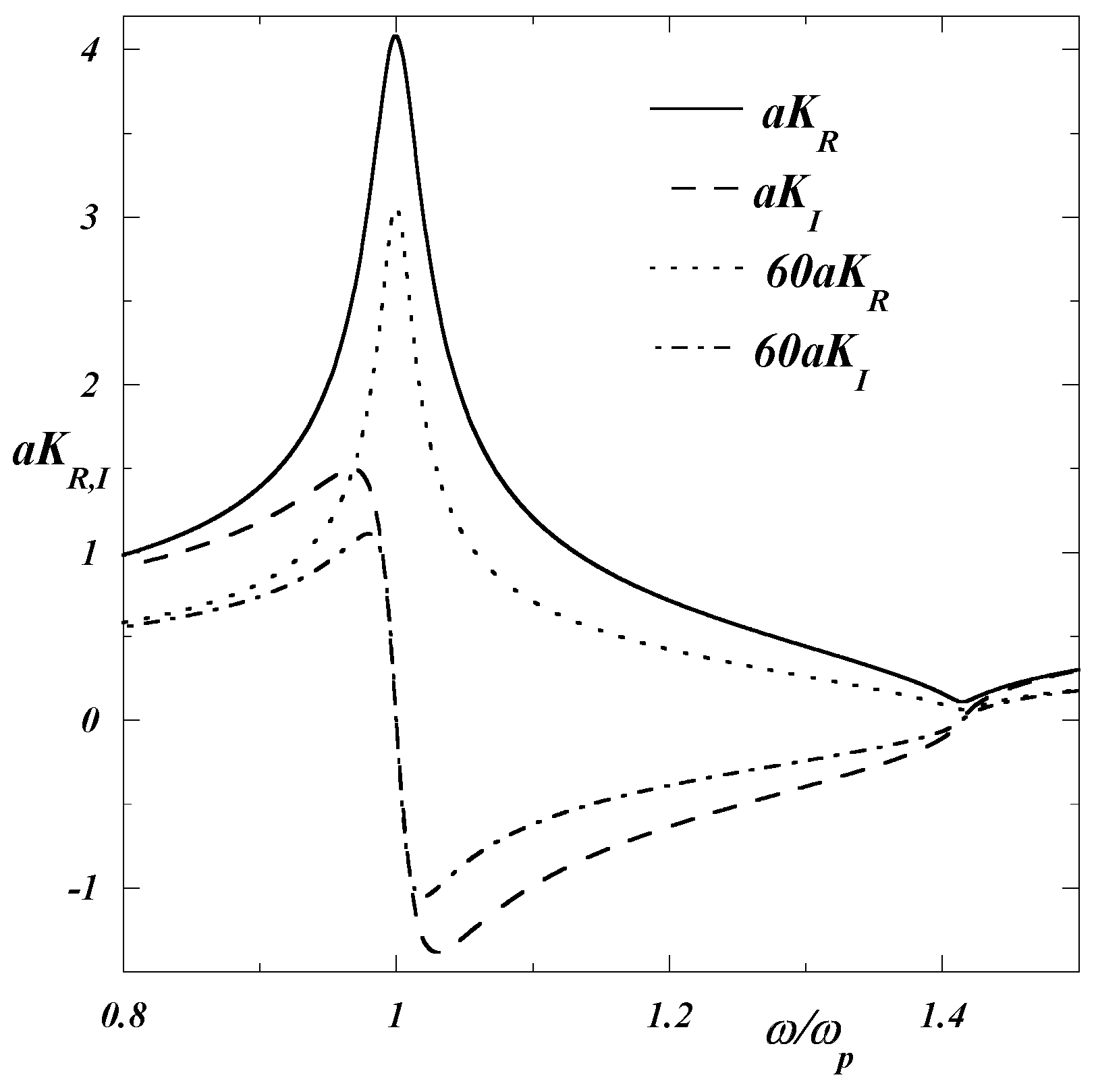

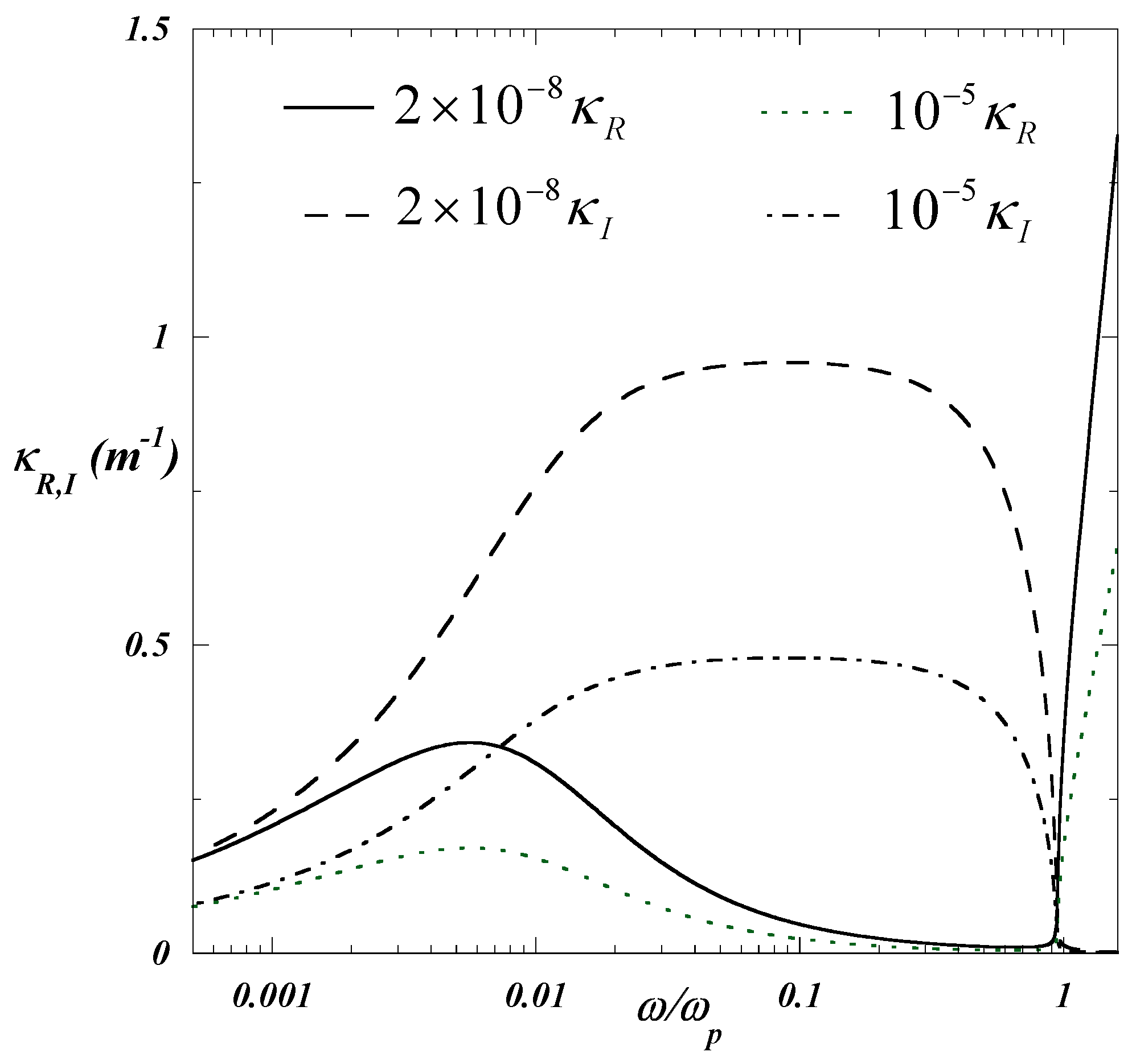

The dispersion curve

, ensuing from Equation (

12), has been plotted in

Figure 2. For

there is

, whereas there is

for

.

4. 3-SHG

The polarisation

and current density

which have been discarded while linearising

in Equations (

2,

9), are both realised to oscillate like

and are thence recognised as the

only source of SHG in this work. They read

which entails for their time-Fourier transforms

owing to Equations (

4,

6)

The average values of

over

are needed to proceed further. They are inferred to read, thanks to Equations (

16,

19)

The SHG signal to be addressed now consists for

in an

electromagnetic wave of frequency

propagating outward along the

radial direction (see

Figure 1) and carrying an electric component, parallel to the

z axis

with the wave number

. However for

,

induces in addition a

drift current density

, obeying Ohm’s law (see Equation (

11)) and a dielectric displacement

, both aligned with the

z axis and reading [

12]

with

given by Equation (

7). The complex number

will be calculated now with help of the wave-equation [

12]

The dispersion curve of electromagnetic waves

plotted in

Figure 3, turns out to differ markedly from that of space-charge waves

, pictured in

Figure 2. Likewise, there is

for

, whereas there is

for

. Actually, the conditions

and

characterise, respectively, the surface plasmon-polaritons [

11,

12], for which the electromagnetic field is confined inside a narrow range

in accordance with the skin effect [

19], and three-dimensional plasmons, penetrating deeply into bulk matter due to

. At last, it is worth noting that there is

, as inferred from Equations (

12,

21) for

, which entails that the associated space-charge and electromagnetic waves are

identical in this particular case, since both are characterised by

but

vanishing space-charge density

and magnetic field. Besides, the plasma oscillation ought to take place at

rather than

, as arbitrarily purported in textbooks [

12,

16,

20] to ensue from

with

defined in Equation (

7).

The unknown

will be assigned thanks to Equations (

11,

20), by substituting

to

, respectively, in the wave-equation (

21), which yields finally

with

given by Equation (

7).

The incoming electromagnetic power

and the outgoing one

can thence be inferred to read

The property

is a signature of the

non-linear character of SHG [

1]. Moreover

reaches its upper bound for

deg.

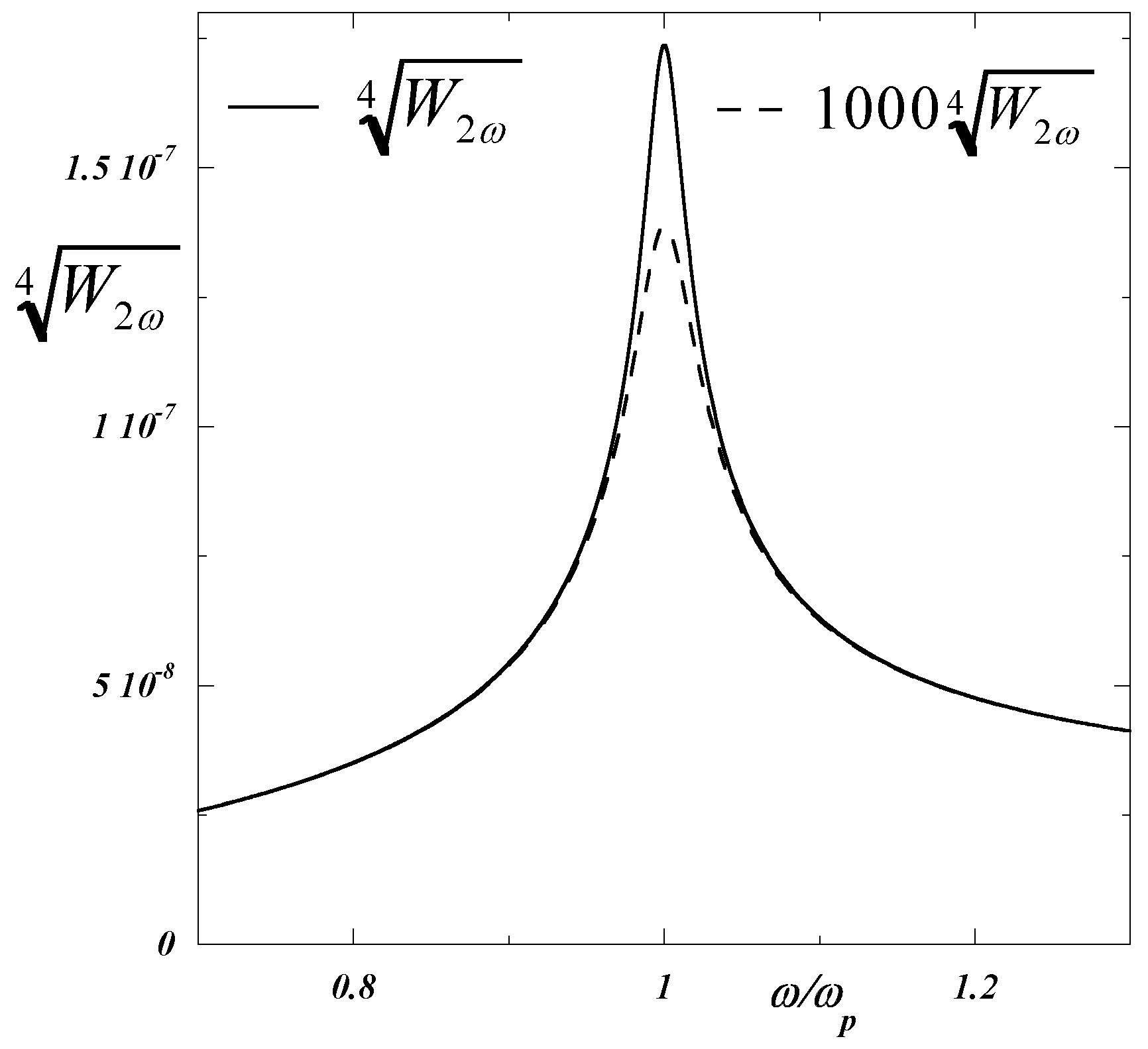

The outgoing power

has been plotted in

Figure 4 for a metal and a semi-conductor. Both plots exhibit a sharp maximum at

, ensuing from

with

, as inferred from Equation (

6) for

.

decreases to 0 with

, whereas it reaches a plateau

for

. The huge ratio

(semi-conductor)

(metal)

, conspicuous in

Figure 4, stems from

Such a behaviour, ensuing from

in Equations (

20,

22), respectively, is thence realised to concur with the ratio of

-values, assumed in Figs.2,4. Therefore choosing a semi-conducting sample of short length

l is likely to greatly enhance the SHG efficiency. Besides, semi-conductors exhibit two additional merits :

semi-conductors, unlike metals of fixed , enable one to tune to the searched frequency, either by controlling the doping rate or monitoring the temperature;

the relatively low value of

rad/s, typical of donor-like semi-conductors permits to benefit from a broader frequency range above

rad/s than in metals and acceptor-like semi-conductors, for which this threshold is pushed up above

rad/s. Moreover this analysis breaks down in the microscopic limit for

, which, in view of Equation (

12), sets upper limits

rad/s and

rad/s for metals and semi-conductors, respectively.

Figure 4.

Plot of the SHG power

at frequency

, expressed in

with

V/m,

nm,

nm; the solid and dashed lines depict the data reckoned for a semi-conductor and a metal, respectively; the various parameters, used for the calculations, have been assigned to the same values, as already taken for

Figure 2.

Figure 4.

Plot of the SHG power

at frequency

, expressed in

with

V/m,

nm,

nm; the solid and dashed lines depict the data reckoned for a semi-conductor and a metal, respectively; the various parameters, used for the calculations, have been assigned to the same values, as already taken for

Figure 2.

5. Conclusions

The properties of

longitudinal space-charge waves have been worked out with help of Equations (

1,

4,

8) and strong emphasis has been put on their being quite different from

transverse electromagnetic waves which are rather solutions of Maxwell’s equations [

12,

18]. Accordingly, a space-charge wave carries

no magnetic field, whereas an electromagnetic wave carries

no three-dimensional space-charge, even though the electromagnetic field may be strongly

spatially inhomogeneous [

9,

10,

11]. However most of textbooks [

12,

20] purport wrongly that the

same dielectric displacement

D comes up, on the one hand, in the Ampère-Maxwell equation

and on the other hand, in Gauss’ equation (see Equation (

4)) and the charge conservation law (see Equation (

8)). Unfortunately such a claim is inconsistent in two respects :

as already recalled above, D contains only the polarisation, stemming from the conduction electrons in Gauss’ equation and the charge conservation law, whereas D includes in addition that of filled bands in the Ampère-Maxwell equation;

there is for Gauss’ equation and the charge conservation law versus for the Ampère-Maxwell equation.

Hopefully this work will help dispel this ubiquitous and harmful confusion.

Figure 1 illustrates how matching both waves together might provide with a novel mechanism of SHG, instrumental over a wide frequency range in semi-conductors. Light has been shed on the advantage offered by nanometric samples. The concentration dependence of

turns out to be redolent of a similar behaviour of the Hall voltage, varying [

21] like

. Note also that the

-dimensional

space charge discussed here, is quite different from the

-dimensional

superficial charge density, conveyed by a surface plasmon polariton [

11,

12]. Last but not least, the

dependences of

, unveiled here, lend themselves to an experimental check.