1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains a major global health challenge, particularly with the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains [

1,

2]. These resistant strains severely compromise current treatment regimens, underscoring the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies [

2,

3]. Among the promising candidates, bortezomib (BTZ), a proteasome inhibitor originally approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma, has shown potent activity against Mtb [

4]. Linezolid (LZD), an oxazolidinone antibiotic, is already an established component of TB treatment regimens [

1,

5]. However, the mechanisms underlying BTZ resistance remain poorly understood [

6], and while LZD resistance has been primarily attributed to ribosomal mutations, non-ribosomal resistance mechanisms remain largely unexplored [

7]. Thus, elucidating these resistance mechanisms is crucial for developing more effective therapeutic strategies.

Previous studies suggest that BTZ inhibits Mtb proteolysis by targeting ClpP1P2, a caseinolytic protease complex encoded by

clpP1 and

clpP2 [

8,

9,

10], and may also act on the Mtb proteasome complex PrcBA, encoded by

prcB and

prcA [

11,

12]. LZD, on the other hand, inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit [

13,

14]. However, some resistant strains lack mutations in these established targets, suggesting the involvement of alternative resistance pathways, like MmpL9, and EmbB-EmbC[

15,

16,

17]. Efflux pump systems, such as the MmpS5-MmpL5 transporter, have been implicated in conferring drug resistance in mycobacteria by actively extruding antimicrobial compounds [

18,

19]. In

Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm), mutations in

MSMEG_1380, encoding a TetR-family transcriptional regulator, have been shown to upregulate efflux pump expression, conferring resistance to multiple drugs, including clofazimine (CFZ) and bedaquiline (BDQ) [

20,

21]. In addition, porins such as

MSMEG_0965 (MspA) play a critical role in drug uptake by facilitating the transport of hydrophilic molecules across the mycobacterial cell wall [

22,

23]. Mutations in genes encoding porins can reduce membrane permeability, thereby diminishing the efficacy of antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones and potentially leading to treatment failure or prolonged therapy duration [

24]. While these resistance mechanisms have been individually characterized, their potential interplay in mediating resistance, particularly in strains with multiple mutations, remains unclear [

25].

In this study, we used the nonpathogenic Msm mc²155 as a model organism [

26] to investigate drug resistance mechanisms in mycobacteria. By screening spontaneous BTZ-resistant mutants and performing whole-genome sequencing (WGS), we identified multiple resistance-associated mutations, despite the absence of mutations in the known BTZ target, suggesting the involvement of alternative resistance mechanisms. Notably, among these mutants, we identified a strain exhibiting high-level resistance to both BTZ and LZD. CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted gene knockout, gene editing, overexpression, and complementation experiments revealed that

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 are key determinants of resistance. Single-gene mutations conferred low-level resistance, while double-gene mutations significantly enhanced resistance to BTZ, LZD, and other antibiotics. The ethidium bromide (EtBr) accumulation assay demonstrated that mutations in

MSMEG_0965 led to a significant reduction in cell wall permeability, resulting in lower intracellular drug concentrations. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that mutations in

MSMEG_1380 promote drug efflux through the upregulation of MmpS5-MmpL5 system [

27,

28]. These findings highlight the synergistic role of

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 in conferring high-level resistance, emphasizing the multifactorial mechanisms between drug uptake and efflux mechanisms. This study advances our understanding of mycobacterial drug resistance and provides valuable insights into potential therapeutic targets for combating MDR/XDR strains.

2. Results

2.1. High Frequency of Spontaneous Mutations Conferring BTZ Resistance in Msm

To investigate potential BTZ targets, we screened Msm mc

2155 strains for spontaneous resistance to BTZ. First, we determined that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of BTZ for Msm was 5 μg/mL. Msm strains were then plated on 7H10 agar plates containing increasing concentrations of BTZ (20 × MIC, 40 × MIC, and 60 × MIC) in four independent batches. From each batch, 10~20 single colonies were randomly selected from each batch, yielding a total of 57 resistant colonies. Subsequently, these colonies were cultured, and the MIC was determined to assess the resistance levels. All strains exhibited MIC ≥ 20 μg/mL (listed in

Table S1), with a spontaneous mutation rate ranging from 1.86 × 10⁻⁷ to 6.60 × 10⁻⁷. In contrast, previous studies reported a spontaneous mutation rate of only 6 × 10⁻¹⁰ in Mtb H37Rv strains screened for rifampin (RIF) resistance on 7H10 agar containing 5 or 10 μg/mL RIF [

29], which is three orders of magnitude lower than the rate observed for BTZ-resistant strains. These findings indicate a relatively high mutation rate in BTZ-resistant Msm strains.

2.2. WGS of BTZ-Resistant Msm Strains Revealed a Variety of Mutations across Different Genes

Sanger sequencing of

prcA,

prcB, and

clpP1P2, which encode known BTZ targets, revealed no mutations in the resistant strains. To further evaluate their roles in BTZ susceptibility, we constructed Msm strains with knockouts of

prcA or

prcB, overexpression of

clpP1P2, and knockdowns of

clpP1 or

clpP2. The results showed no significant correlation was found between BTZ susceptibility and these genetic modifications (

Figure S1), suggesting that BTZ resistance in Msm may involve alternative resistance mechanisms beyond these known targets.

To further explore potential resistance mechanisms, we randomly selected 5 resistant strains from the 57 isolates and parent strain for WGS. The sequencing analysis identified 35 unique mutations across various genes (

Table S2). Among them,

MSMEG_3244 was the most frequently mutated gene (4/5 strains), followed by

MSMEG_5085 and

MSMEG_3987 (2/5 strains). Mutations in

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 were detected in only one strain. Sanger sequencing of these genes across all 57 isolates revealed mutation frequencies of 7% (

MSMEG_3244), 42% (

MSMEG_5085), 17% (

MSMEG_3987), 3% (

MSMEG_1380), and 3% (

MSMEG_0965). Further validation is required to determine the association of these genes with BTZ resistance.

2.3. BTZ-Resistant Msm Strains Exhibited Cross-Resistance to Other Antibiotics

To determine whether the spontaneous drug-resistant mutants exhibited cross-resistance, we tested the susceptibility of WGS-analyzed strains to a range of antibiotics (

Table 1). Most resistant strains showed no significant changes (a 4-fold change in MIC) in their sensitivity to antibiotics such as levofloxacin (LEV), amikacin (AMK), and streptomycin (STR). However, some strains exhibited notable cross-resistance. For instance, Msm-R1-2 demonstrated high resistance to both BTZ and LZD, with MICs rising to 80 µg/mL and 128 µg/mL, respectively. Additionally, the MIC of clarithromycin (CLR) increased 4-fold. Similarly, Msm-R1-13 exhibited an 8-fold increase in MIC of CLR and a 4-fold increase in MIC of gentamicin (GEN), while Msm-R4-1 showed a 4-fold increase in MIC of ethambutol (EMB). These observations suggest that resistance mechanisms may involve shared pathways that regulate cross-resistance, warranting further investigation.

2.4. Single Knockout of MSMEG_1380 or MSMEG_0965 in Msm Resulted in Low-Level Resistance to BTZ and LZD

To further investigate the genes associated with Msm's resistance to BTZ, we used CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted recombineering technology [

30] to knock out

MSMEG_3244,

MSMEG_5085,

MSMEG_3987,

MSMEG_1380, and

MSMEG_0965 genes. We then tested the MICs of BTZ against these knockout strains. The results showed that compared to Msm, Msm

Δ3244, Msm

Δ5085, and Msm

Δ3987 exhibited no significant changes in resistance to BTZ, indicating that these genes are not involved in the resistance mechanism. In contrast, Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965 resulted in a 4-fold increase in the MIC of BTZ compared to Msm, suggesting that

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 play crucial roles in Msm's resistance to BTZ (

Table 2).

Given that Msm-R1-2, a strain exhibiting high-level resistance to both BTZ and LZD, harbors mutations in

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 (Tabes 1 and S2), we further evaluated the LZD susceptibility of Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965 to determine their individual contributions to resistance. The results showed that, compared to the wild-type Msm, both Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965 exhibited a 4-fold increase in the MIC of LZD (

Table 3). These findings suggest that

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 are key contributors to BTZ and LZD resistance in Msm.

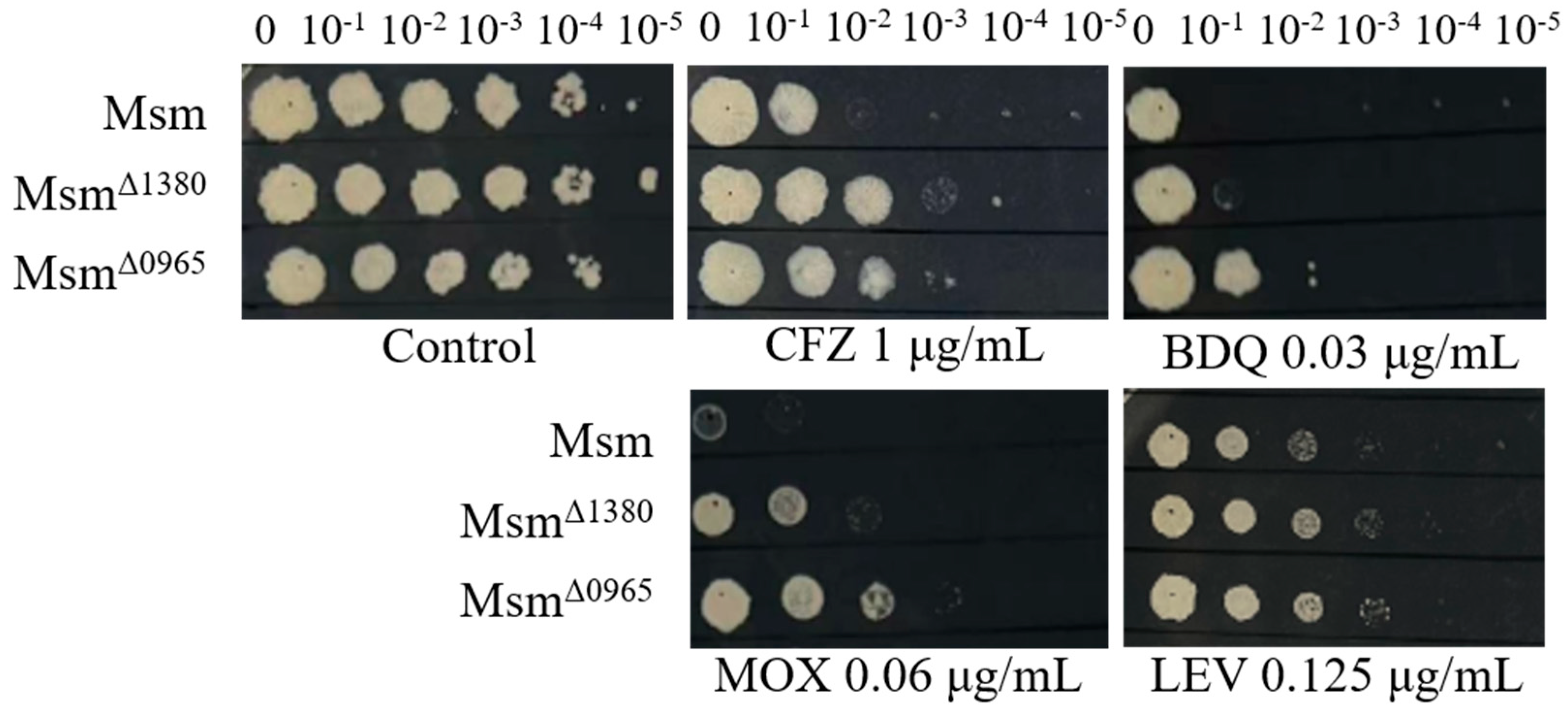

2.5. Single Knockout of MSMEG_1380 or MSMEG_0965 in Msm Affected the Sensitivity of to Other Antibiotics

Previous studies have suggested that

MSMEG_1380 is associated with drug efflux mechanisms, while

MSMEG_0965 is linked to drug uptake processes[

28,

31]. Mutations in these genes are known to confer resistance to multiple antibiotics. To investigate the roles of

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965, we tested the susceptibility of Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965 to a range of antibiotics. Both knockout strains (Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965) exhibited resistance to CFZ, moxifloxacin (MOX), and LEV. Interestingly, BDQ resistance was observed only in Msm

Δ0965, indicating that

MSMEG_0965 plays a specific role in mediating BDQ resistance (

Figure 1). In addition, both Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965 displayed a 4-fold increase in MIC of vancomycin (VAN). Furthermore, Msm

Δ0965 also exhibited an 8-fold increase in MIC of CLR, a 4-fold increase in MIC of sulfadiazine (SDZ), and a 16-fold increase in MIC of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) (

Table 4). In contrast, both knockout strains (Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965) showed no significant differences in MICs for EMB, STR, GEN, and AMK compared to the wild type Msm (

Table S3). These findings suggest that while the knockout of

MSMEG_1380 or

MSMEG_0965 in Msm strains affects sensitivity to various antibiotics, with distinct and gene-specific mechanisms of action that do not apply universally to all antibiotics, such as BDQ.

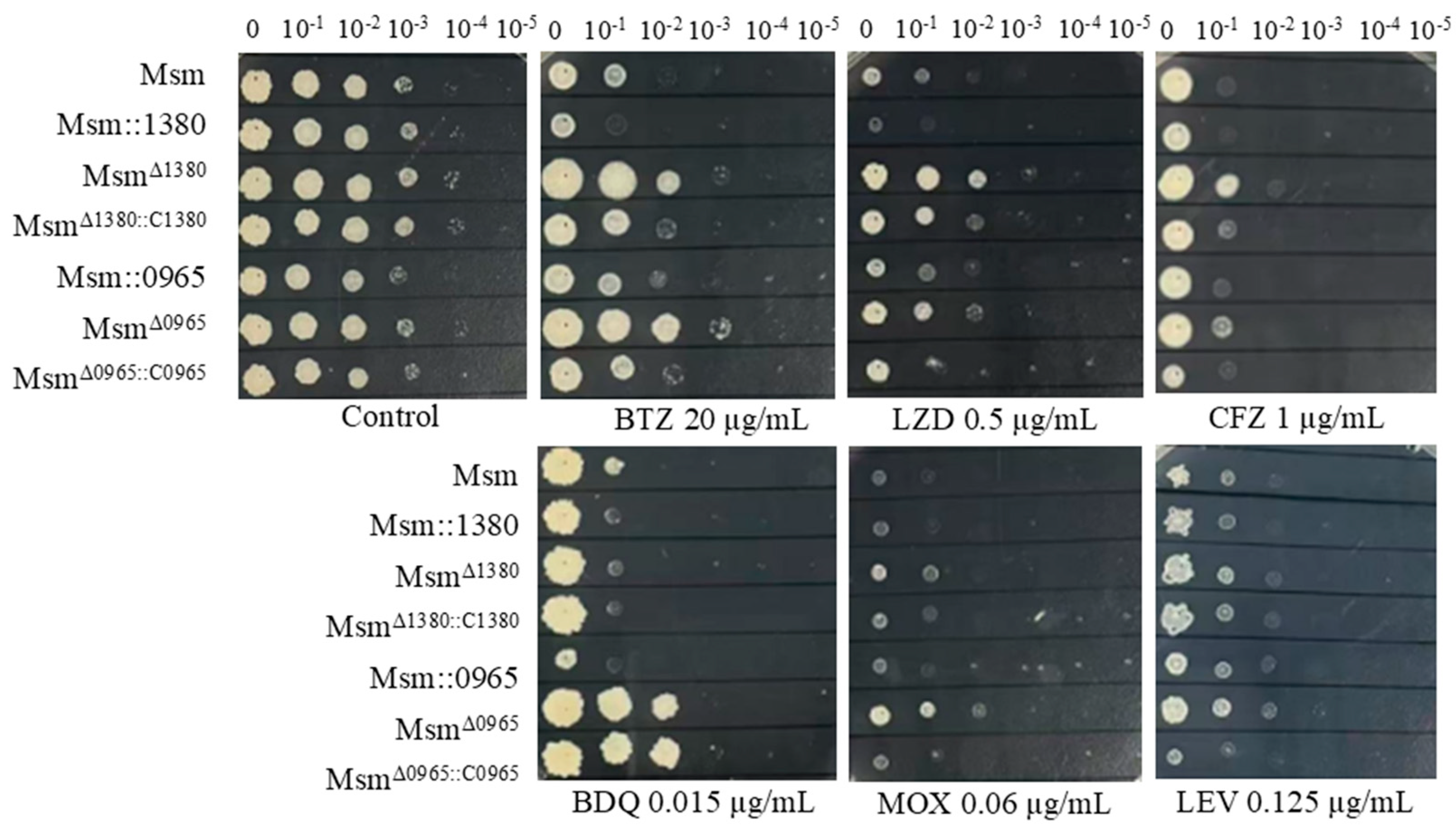

2.6. Overexpression of MSMEG_1380 or MSMEG_0965 in Msm and Complementation of these Genes in Knockout Strains Affected the Drug Sensitivity to BTZ and LZD

To further investigate the functional contributions of

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 to drug susceptibility phenotypes, we generated Msm recombinant strains harbouring overexpression constructs for these genes and performed genetic complementation in their respective knockout backgrounds. Overexpression and genetic complementation of

MSMEG_1380 were placed under the transcriptional control of the

hsp60 promoter, while the corresponding manipulations for

MSMEG_0965 utilised its native promoter. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) revealed that Msm::1380 and Msm::0965 strains displayed enhanced sensitivity to BTZ and LZD. Genetic complementation of Msm

Δ1380::C1380 partially restored sensitivity to BTZ, LZD, CFZ. Similarly, complementation of Msm

Δ0965::C0965 wild-type susceptibility levels to BTZ, LZD, MOX, and CFZ. Notably, BDQ susceptibility remained unaltered in the Msm

Δ0965::C0965 strain, suggesting a gene-specific interaction between

MSMEG_0965 and intrinsic BDQ resistance mechanisms (

Figure 2). We also evaluated the susceptibility of these strains to other antibiotics, including VAN and CLR. The MICs of these antibiotics in the overexpression strains remained equivalent to those of wild-type Msm, and the MICs in the complementation strains showed no significant changes compared to their respective knockout strains (

Table S4). These results suggest that overexpression of

MSMEG_1380 or

MSMEG_0965, and complementation in the respective knockout strains affect specific drug sensitivity, but their underlying regulatory mechanisms differ, highlighting the complexity of the regulatory networks involved.

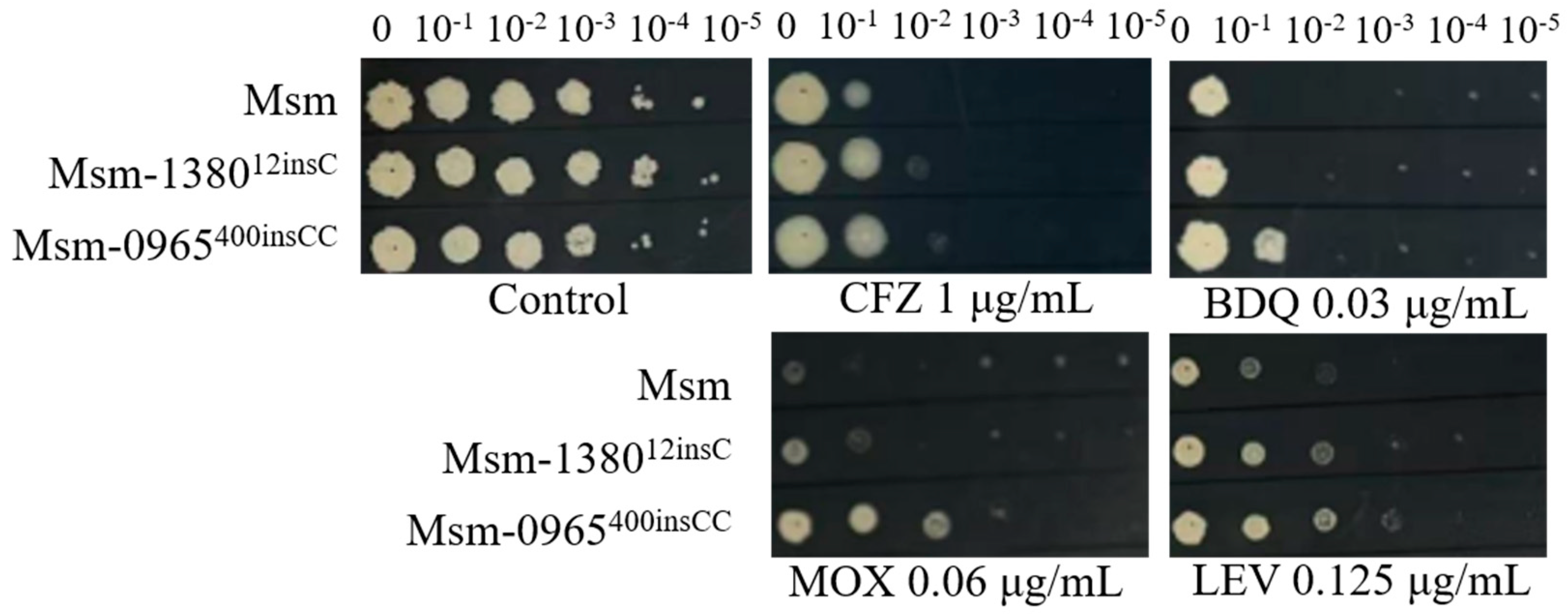

2.7. Roles of MSMEG_138012insC and MSMEG_0965400insCC in Multidrug Resistance were Confirmed by Gene Editing in Msm

To verify that single mutations in

MSMEG_1380 or

MSMEG_0965 confer resistance to multiple drugs, we employed CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted recombineering technology [

30] to edit the respective mutation sites in these genes. The drug susceptibility profiles of the single gene-edited strains were consistent with those of Msm

Δ1380 and Msm

Δ0965 (

Figure 1,

Table 4 and

Table 5,

Figure 3). These results indicated that single knockout or mutation of

MSMEG_1380 or

MSMEG_0965 in Msm conferred only low-level resistance to BTZ and LZD rather than the high-level resistance observed in the Msm-R1-2 strain. These findings confirm the important roles of

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 in conferring drug resistance in Msm. However, the precise mechanisms underlying the high-level resistance to BTZ and LZD observed in the Msm-R1-2 remain to be further elucidated.

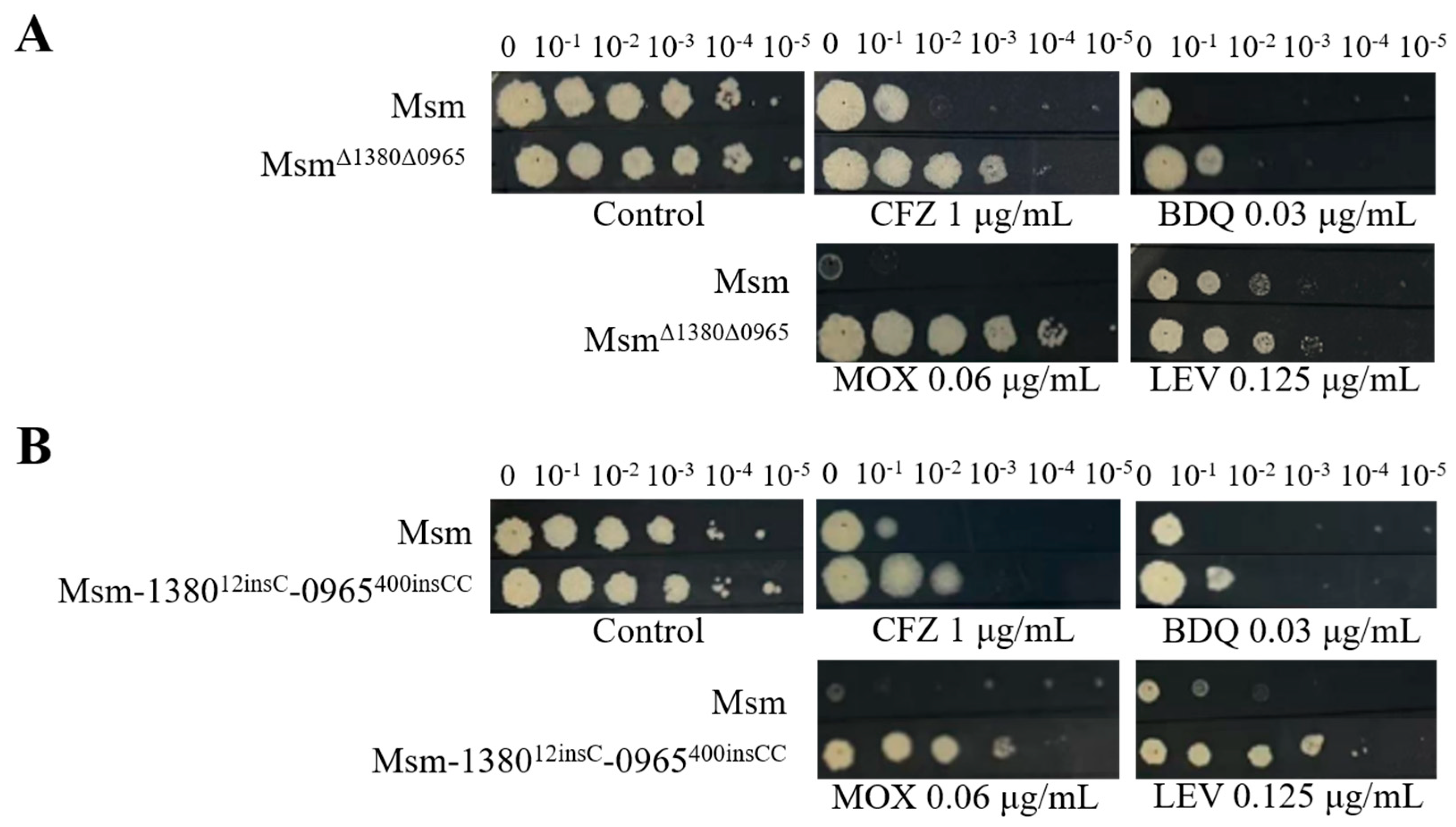

2.8. Dual Mutations of MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 in Msm Exhibited High-Level Resistance to BTZ and LZD

Based on the above results, we hypothesize that the dual mutations in

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 are the primary cause of high-level resistance in Msm [

32,

33]. To validate this hypothesis, we used CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted recombineering technology [

30] to perform the dual knockouts and gene editing strains of these two genes in Msm. DST revealed that the MICs of BTZ and LZD against the dual mutation strains (Msm

Δ1380Δ0965 and Msm-1380

e12insC-0965

e400insCC) were 16-fold and 64-fold higher respectively than those to Msm (

Table 6), which was consistent with the MIC values observed in Msm-R1-2 (

Table 1). Compared to the single-gene mutant strains, the dual mutation strains also exhibited higher resistance to MOX and LEV (

Figure 1,

Figure 3, and

Figure 4), and increased resistance to VAN (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). The resistance levels of the double mutation strains to CLR, SDZ, and SMX were comparable to those of Msm

Δ0965 and Msm-0965

e400insCC (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). Interestingly, the complementation of

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 in the double-knockout strains did not alter the MICs of multi-drugs (

Table 6). Based on the MIC results of the dual knockout and dual gene-edited strains, we propose that the dual mutations of

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 in Msm are the main reason for Msm's high-level resistance to BTZ and LZD, and they also influence the sensitivity to other antibiotics.

2.8. Knockout and Mutation of MSMEG_0965 Reduced Cell Wall Permeability

Based on the function of the protein encoded by

MSMEG_0965 [

23], we hypothesized that mutations in

MSMEG_0965 might impair cell wall permeability [

34,

35]. To test this hypothesis, we performed the EtBr accumulation assay[

36] to evaluate cell wall permeability in Msm-R1-2, knockout and gene-edited Msm strains. The results showed that Msm-R1-2, Msm

Δ0965 and Msm-0965

e400insCC strains exhibited significantly reduced cell wall permeability, while the permeability of Msm

Δ1380 and Msm-

1380e12insC remained unchanged. Similarly, the permeability of Msm

Δ1380Δ0965 and Msm-1380

e12insC-0965

e400insCC was also significantly decreased (

Figure 5). These results indicate that knockout and mutation of

MSMEG_0965 reduce cell wall permeability, thereby contributing to drug resistance, while

MSMEG_1380 does not appear to affect cell wall permeability.

3. Discussion

The emergence of MDR and XDR Mtb strains presents a critical barrier to global TB control, emphasizing the urgent need for new therapeutic strategies [

1,

37]. This study provides novel insights into the mechanisms underlying BTZ and LZD resistance, identifying double mutations in

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 as key contributors to high-level resistance. These findings highlight the synergistic effect of efflux and uptake pathways in mediating drug resistance. This new and previously unreported phenomenon underscores the importance of multifactorial resistance mechanisms in mycobacteria.

DST revealed that certain BTZ-resistant strains, such as Msm-R1-2, exhibit cross-resistance to LZD and CLR, suggesting a network effect where BTZ resistance influences the activity of other drugs [

38,

39,

40]. Notably, single-gene mutations in

MSMEG_1380 or

MSMEG_0965 result in low-level resistance to BTZ and LZD (4-fold increase in MIC), while double mutations produce a synergistic effect, raising MICs by 16-fold and 64-fold, respectively. Interestingly, resistance levels to CLR, SDZ, and SMX in the double-mutant strain aligned with those observed in the

MSMEG_0965 single mutant strain, suggesting

MSMEG_0965 primarily mediates resistance to these drugs (

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5).

Further characterization of single-gene knockout strains revealed that Msm

Δ0965, but not Msm

Δ1380 (

Figure 1), confers resistance to BDQ [

41,

42]. This finding suggests a lack of clear genotype-phenotype correlation for BDQ resistance in this context and implicates MspA porin may be a critical determinant [

22,

43,

44,

45]. Complementation and overexpression experiments showed that

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 influence drug sensitivity to BTZ, LZD, and some other antibiotics, but their effects on drugs like LEV, VAN, and CLR remained unchanged. These results highlight the potential strain-dependent effects of genetic modifications and the complexity of antibiotic resistance regulation [

46].

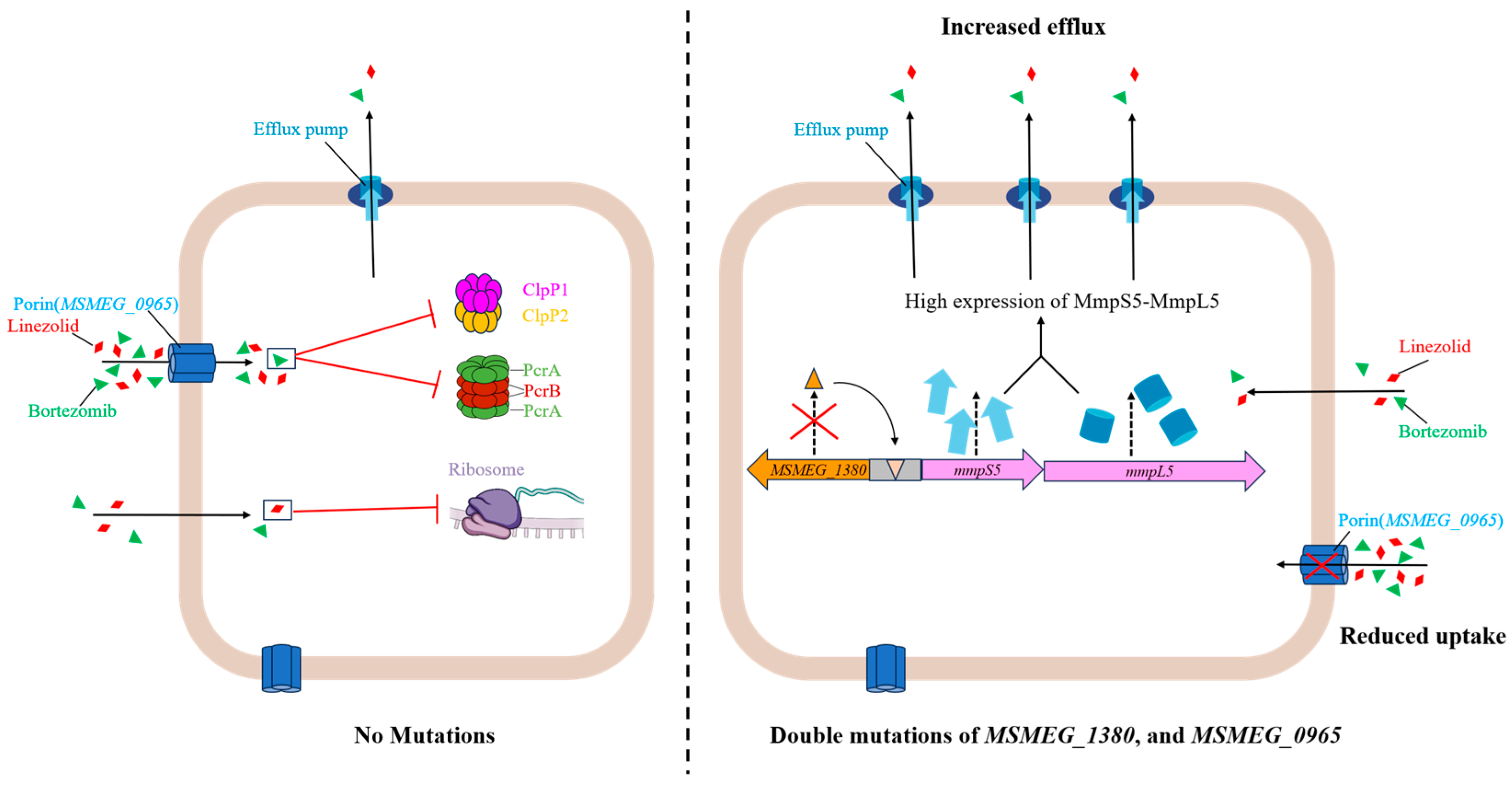

Mechanistically,

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965 appear to act synergistically to confer high-level resistance to BTZ and LZD.

MSMEG_1380 likely enhances the expression or activity of the MmpS5-MmpL5 system, promoting increased drug efflux and reduced intracellular drug concentrations [

27,

28]. In parallel,

MSMEG_0965 modulates the MspA porin, altering cell wall permeability and limiting the passive diffusion of antibiotics [

22,

43,

47]. Together, these dual mechanisms significantly contribute to the observed multidrug resistance phenotype, highlighting the complex regulatory interplay between efflux and uptake systems [

32,

33,

48] (

Figure 6). Our findings provide phenotypic evidence for the synergistic action of

MSMEG_1380 and

MSMEG_0965, supporting a multifactorial regulatory model of resistance [

38,

39,

40].

Despite these advances, the study has limitations. First, these findings were observed in Msm, a non-pathogenic model organism, and their relevance to clinical Mtb strains requires further validation. Second, while the phenotypic effects of MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 mutations are well-characterized, their precise molecular mechanisms are not yet fully understood. Functional studies, including protein structure-function analyses and investigations of regulatory pathways, are essential to further elucidate their roles. Lastly, other potential resistance pathways and mutations were not explored in this study, warranting further investigation.

Future studies should focus on validating these findings in Mtb clinical isolates, elucidating the molecular mechanisms of MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965, and identifying additional resistance-associated pathways. Therapeutic strategies targeting the MmpS5-MmpL5 efflux system or restoring porin functionality could provide promising avenues for overcoming resistance. Furthermore, continued exploration of BTZ resistance mechanisms will be critical for gaining valuable insights and providing the base for the development of next-generation anti-TB therapies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

All mycobacterial strains were cultured at 37℃ in 7H9 liquid medium supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, 0.2% glycerol, and 10% OADC, or on 7H10/7H11 solid medium. Antibiotics were added to the media as required: 50 μg/mL kanamycin (KAN) and 30 μg/mL zeocin (ZEO). For induced expression, 200 ng/mL anhydrotetracycline (aTc) was added. All Escherichia coli strains were cultured in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL KAN, 30 μg/mL ZEO, and 100 μg/mL ampicillin as required.

4.2. Screening for Spontaneous BTZ-Resistant Msm Strains

Msm cultures at an OD

600 of 1.0 were plated (500 μL) on 7H10 medium containing 100, 200, or 300 μg/mL BTZ, with two replicates per concentration. Serial tenfold dilutions were then plated on BTZ-free 7H10 agar to calculate colony-forming units (CFU). The mutation frequency was determined by counting CFU and the number of resistant colonies. Resistant strains were analyzed for mutations in

prcBA and

clpP1P2 by Sanger sequencing using primers listed in

Table S5. Genomic DNA from the parent strain and seven BTZ-resistant strains (which did not harbor mutations in

prcA,

prcB,

clpP1, or

clpP2) was sequenced by Shanghai Jingnuo Biotechnology Co. Mutations in the resistant strains were identified by comparing their genomic profiles to that of the parent strain (

Table S4).

4.3. Construction of Knockout Strains

Gene knockout was performed using CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted recombineering technology [

30]. First, the pJV53-Cpf1 plasmid was electroporated into Msm to obtain Msm::pJV53-cpf1 and then induced competent cells were prepared. The crRNA sequences were designed using the website (

https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/), synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (

Table S6), and ligated into the linearized pCR-Zeo vector after annealing. Approximately 800 bp upstream and downstream fragments (including 15-36 bp of the target gene to be deleted) were amplified by PCR and assembled into the pBlueSK vector, followed by PCR amplification of the resulting ~1600 bp double-stranded template. The pCR-Zeo plasmid containing the crRNA sequence and the double-stranded template were then electroporated into the Msm::pJV53-cpf1 inducible competent cells. The cells were plated on 7H11 agar containing 50 μg/mL KAN, 30 μg/mL ZEO, and 200 ng/mL aTc and incubated at 30℃. Positive colonies were identified by PCR and Sanger sequencing.

4.4. Construction of Overexpression and Complementation Strains

The target genes were amplified from Msm and cloned into the linearized pRH2502 plasmid under the control of either the exogenous

hsp60 promoter or the native promoter of the respective genes. Primers used in this study are listed in

Table S5. The recombinant plasmids were electroporated into either wild-type Msm (for overexpression strains) or the corresponding knockout strains (for complementation strains). Transformants were plated on 7H10 agar containing 50 μg/mL KAN, and positive colonies were confirmed by PCR.

4.5. Construction of Gene Editing Strains

CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted recombineering [

30] was used for gene editing. CrRNAs targeting the mutation sites were designed using the CHOPCHOP web tool (

Table S6) and subsequently into the linearized pCR-Zeo vector. The 500 bp flanking regions (~1000 bp total) of the mutation site were amplified from the resistant strains and used as repair templates. The crRNA-containing pCR-Zeo plasmid and repair templates were co-electroporated into Msm::pJV53-Cpf1 inducible competent cells. Transformants were plated on 7H11 agar containing 50 μg/mL KAN, 30 μg/mL ZEO, and 200 ng/mL aTc and incubated at 30℃. Positive colonies were confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing.

4.6. DST

In this study, all drugs were prepared in solutions with DMSO or water at a final concentration of 10 mg/mL, except for CFZ, which was prepared at a final concentration of 5 mg/mL. Two methods were used to test the drug susceptibility of the strains. Knockout, overexpression, and complementation strains were grown in 7H9 medium at 37℃ to the logarithmic phase for both methods.

For the microplate broth dilution assay, cultures were adjusted to an OD

600 of 0.5 and diluted 1:1000. The MICs were determined using the broth microdilution method in 96-well plates. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 72 hours, and the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that visibly inhibited bacterial growth [

17].

For the solid plate assay, cultures were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.9. Bacterial suspensions were serially diluted in 10-fold increments to obtain six different dilutions, ranging from the undiluted suspension to a 10-5 dilution. A 1 µL aliquot of each dilution was spotted onto solid media containing different concentrations of drugs, with 7H10 solid media without antibiotics serving as the control. The plates were incubated at 37℃ for three days, and colony growth was assessed visually and photographed.

4.7. Cell Wall Permeability Assay

EtBr accumulation assay was performed as described previously [

36]. The EtBr working solution (4 μg/mL) was prepared in PBS containing 0.08% glucose and 0.05% Tween 80 was prepared. Cultures were grown to an OD

600 of 0.6–0.8, centrifuged, and resuspended in PBS with 0.05% Tween 80 to an OD

600 of 0.5. For each strain, 100 μL of the cell suspension was added to a white 96-well plate (3 experimental wells, 3 no-reagent controls, and 3 no-cell controls). Fluorescence was measured using a multimode microplate reader (excitation: 530 nm, emission: 590 nm) at 1-minute intervals over 60 minutes. Background fluorescence was subtracted, and data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2. Results are presented as the mean ± SD, with

n=3 for each group. Statistical significance was assessed using an independent

t-test, with

P < 0.05 considered significant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.G. (Yamin Gao), T.Z. (Tianyu Zhang); Methodology: H.Z. (Han Zhang); Software: H.Z. (Han Zhang), B.Y. (Buhari Yusuf); Validation: H.Z. (Han Zhang), Y.G. (Yamin Gao), T.Z. (Tianyu Zhang); Formal Analysis: B.Y. (Buhari Yusuf); Investigation: H.Z. (Han Zhang), C.F. (Cuiting Fang); Resources: H.M.A.H. (H.M. Adnan Hameed), Y.G. (Yamin Gao), T.Z. (Tianyu Zhang); Data Curation: B.Y. (Buhari Yusuf); Writing – Original Draft Preparation: H.Z. (Han Zhang), C.F. (Cuiting Fang); Writing – Review & Editing: C.F. (Cuiting Fang), X.Z. (Xiaoqing Zhu), S.W. (Shuai Wang), H.M.A.H. (H.M. Adnan Hameed), Y.G. (Yamin Gao), T.Z. (Tianyu Zhang); Visualization: H.Z. (Han Zhang); Supervision: Y.G. (Yamin Gao) , T.Z. (Tianyu Zhang); Project Administration: Y.G. (Yamin Gao), T.Z. (Tianyu Zhang); Funding Acquisition: H.M.A.H. (H.M. Adnan Hameed), Y.G. (Yamin Gao), T.Z. (Tianyu Zhang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1300904), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 32300152), partially by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFF0713600), the State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (SKLRD-Z-202414, SKLRD-Z-202301), and Guangzhou Science and Technology Plan-Youth Doctoral "Sail" Project (2024A04J4273). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the group of Yicheng Sun from the Institute of Pathogenic Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, for kindly sending the pJV53-Cpf1 and pCR-Zeo plasmids as tools for gene knockout and gene editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Organization, W.H. Global tuberculosis report 2024; World Health Organization: 2024.

- Dheda, K.; Mirzayev, F.; Cirillo, D.M.; Udwadia, Z.; Dooley, K.E.; Chang, K.-C.; Omar, S.V.; Reuter, A.; Perumal, T.; Horsburgh, C.R., Jr.; et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2024, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Qi, Y.; Yan, X.; Qi, G.; Peng, Q. The progress of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug targets. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1455715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, W.; Ngan Grace, J.Y.; Low Jian, L.; Poulsen, A.; Chia Brian, C.S.; Ang Melgious, J.Y.; Yap, A.; Fulwood, J.; Lakshmanan, U.; Lim, J.; et al. Target mechanism-based whole-cell screening identifies bortezomib as an inhibitor of caseinolytic protease in mycobacteria. mBio 2015, 6, 10.1128–10.1128/mbio.00253-00215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalá, L.; Ruiz-Serrano, M.J.; Pérez-Fernández Turégano, C.; García De Viedma, D.; Díaz-Infantes, M.; Marín-Arriaza, M.; Bouza, E. In vitro activities of linezolid against clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis that are susceptible or resistant to first-line antituberculous drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003, 47, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Aurooz, F.; Singh, V. Clp protease complex as a therapeutic target for tuberculosis. In Bacterial Enzymes as Targets for Drug Discovery; Elsevier: 2025; pp. 363-385. [CrossRef]

- Sander, P.; Belova, L.; Kidan, Y.G.; Pfister, P.; Mankin, A.S.; Böttger, E.C. Ribosomal and non-ribosomal resistance to oxazolidinones: species-specific idiosyncrasy of ribosomal alterations. Mol Microbiol 2002, 46, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, W.; Santhanakrishnan, S.; Dymock, B.W.; Dick, T. Bortezomib warhead-switch confers dual activity against mycobacterial caseinolytic protease and proteasome and selectivity against human proteasome. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupoli, T.J.; Vaubourgeix, J.; Burns-Huang, K.; Gold, B. Targeting the proteostasis network for mycobacterial drug discovery. ACS Infect Dis 2018, 4, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Lin, G.; Wang, M.; Dick, L.; Xu, R.-M.; Nathan, C.; Li, H. Structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteasome and mechanism of inhibition by a peptidyl boronate. Mol Microbiol 2006, 59, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, W.; Santhanakrishnan, S.; Ngan, G.J.Y.; Low, C.B.; Sangthongpitag, K.; Poulsen, A.; Dymock, B.W.; Dick, T. Towards selective mycobacterial ClpP1P2 inhibitors with reduced activity against the human proteasome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e02307–02316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Hu, G.; Tsu, C.; Kunes, Y.Z.; Li, H.; Dick, L.; Parsons, T.; Li, P.; Chen, Z.; Zwickl, P.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis prcBA genes encode a gated proteasome with broad oligopeptide specificity. Mol Microbiol 2006, 59, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadura, S.; King, N.; Nakhoul, M.; Zhu, H.; Theron, G.; Köser, C.U.; Farhat, M. Systematic review of mutations associated with resistance to the new and repurposed Mycobacterium tuberculosis drugs bedaquiline, clofazimine, linezolid, delamanid and pretomanid. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020, 75, 2031–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.C.; Ng, H.F.; Ngeow, Y.F. Mechanisms of linezolid resistance in mycobacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Xu, L.; Zou, Y.; Li, B.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, M.; Xu, B.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chu, H. Molecular analysis of linezolid-resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63, e01842–01818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Hameed, H.M.A.; Wang, S.; Fang, C.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Ju, Y.; et al. EmbB and EmbC regulate the sensitivity of Mycobacterium abscessus to echinomycin. mLife 2024, 3, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Cai, X.; Yu, W.; Zeng, S.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Gao, Y.; Lu, Z.; Hameed, H.M.A.; Fang, C.; et al. Arabinosyltransferase C mediates multiple drugs intrinsic resistance by altering cell envelope permeability in Mycobacterium abscessus. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e0276321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.J.; Haeili, M.; Ghazi, M.; Goudarzi, H.; Pormohammad, A.; Imani Fooladi, A.A.; Feizabadi, M.M. New insights in to the intrinsic and acquired drug resistance mechanisms in mycobacteria. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.; Gutiérrez, A.V.; Viljoen, A.J.; Ghigo, E.; Blaise, M.; Kremer, L. Mechanistic and structural insights into the unique TetR-dependent regulation of a drug efflux pump in Mycobacterium abscessus. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, C.; Ortiz, A.T.; Tan, C.C.S.; Pang, J.; Acman, M.; Millard, J.; Padayatchi, N.; Grant, A.D.; O'Donnell, M.; Pym, A.; et al. Detection of a historic reservoir of bedaquiline/clofazimine resistance-associated variants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Med 2024, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartkoorn, R.C.; Uplekar, S.; Cole, S.T. Cross-resistance between clofazimine and bedaquiline through upregulation of MmpL5 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 2979–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, C.; Kubetzko, S.; Kaps, I.; Seeber, S.; Engelhardt, H.; Niederweis, M. MspA provides the main hydrophilic pathway through the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol 2001, 40, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, P.A. Cellular impermeability and uptake of biocides and antibiotics in gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol 2002, 92, 46S–54S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilchanka, O.; Pavlenok, M.; Niederweis, M. Role of porins for uptake of antibiotics by Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008, 52, 3127–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gygli, S.M.; Borrell, S.; Trauner, A.; Gagneux, S. Antimicrobial resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: mechanistic and evolutionary perspectives. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017, 41, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snapper, S.B.; Melton, R.E.; Mustafa, S.; Kieser, T.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr. Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol 1911, 4, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslov, D.A.; Shur, K.V.; Vatlin, A.A.; Danilenko, V.N. MmpS5-MmpL5 transporters provide Mycobacterium smegmatis resistance to imidazo[1,2-b][1,2,4,5]tetrazines. Pathogens 2020, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salini, S.; Muralikrishnan, B.; Bhat, S.G.; Ghate, S.D.; Rao, R.S.P.; Kumar, R.A.; Kurthkoti, K. Overexpression of a membrane transport system MSMEG_1381 and MSMEG_1382 confers multidrug resistance in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microb Pathog 2023, 185, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billington, O.J.; McHugh, T.D.; Gillespie, S.H. Physiological cost of rifampin resistance induced in vitro in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999, 43, 1866–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.Y.; Yan, H.Q.; Ren, G.X.; Zhao, J.P.; Guo, X.P.; Sun, Y.C. CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted recombineering in bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Deng, L.; Lin, D.; Zheng, W. In vitro activity of tetracycline analogs against multidrug-resistant and extensive drug resistance clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2023, 140, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, A.; Bakht, P.; Saini, M.; Pandey, S.; Pathania, R. Role of bacterial efflux pumps in antibiotic resistance, virulence, and strategies to discover novel efflux pump inhibitors. Microbiology (Reading) 2023, 169, 001333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Guo, L.; Bao, Z.; Xian, M.; Zhao, G. Efflux pumps and porins enhance bacterial tolerance to phenolic compounds by inhibiting hydroxyl radical generation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederweis, M. Mycobacterial porins--new channel proteins in unique outer membranes. Mol Microbiol 2003, 49, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, G.E.; Niederweis, M.; Russell, D.G. Decreased outer membrane permeability protects mycobacteria from killing by ubiquitin-derived peptides. Mol Microbiol 2009, 73, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.; Ramos, J.; Couto, I.; Amaral, L.; Viveiros, M. Ethidium bromide transport across Mycobacterium smegmatis cell-wall: correlation with antibiotic resistance. BMC Microbiol 2011, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheda, K.; Gumbo, T.; Maartens, G.; Dooley, K.E.; McNerney, R.; Murray, M.; Furin, J.; Nardell, E.A.; London, L.; Lessem, E.; et al. The epidemiology, pathogenesis, transmission, diagnosis, and management of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and incurable tuberculosis. Lancet Respir Med 2017, S2213-2600(2217)30079-30076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dwivedi, S.P.; Gaharwar, U.S.; Meena, R.; Rajamani, P.; Prasad, T. Recent updates on drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of applied microbiology 2020, 128, 1547–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, D.R.; Berríos-Caro, E.; Joerres, C.; Suñé, M.; Forsyth, J.H.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Galla, T.; Knight, C.G. Mutators can drive the evolution of multi-resistance to antibiotics. PLoS Genet 2023, 19, e1010791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igler, C.; Rolff, J.; Regoes, R. Multi-step vs. single-step resistance evolution under different drugs, pharmacokinetics, and treatment regimens. Elife 2021, 10, e64116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.; Gutiérrez, A.V.; Viljoen, A.; Rodriguez-Rincon, D.; Roquet-Baneres, F.; Blaise, M.; Everall, I.; Parkhill, J.; Floto, R.A.; Kremer, L. Mutations in the MAB_2299c TetR regulator confer cross-resistance to clofazimine and bedaquiline in Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 63, e01316–01318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snobre, J.; Villellas, M.C.; Coeck, N.; Mulders, W.; Tzfadia, O.; de Jong, B.C.; Andries, K.; Rigouts, L. Bedaquiline- and clofazimine- selected Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants: further insights on resistance driven largely by Rv0678. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 10444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailaender, C.; Reiling, N.; Engelhardt, H.; Bossmann, S.; Ehlers, S.; Niederweis, M. The MspA porin promotes growth and increases antibiotic susceptibility of both Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology (Reading) 2004, 150, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenkalb, L.; Carter, J.; Spitaleri, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Hunt, M.; Malone, K.; Utpatel, C.; Cirillo, D.M.; Rodrigues, C.; Nilgiriwala, K.S.; et al. Deciphering bedaquiline and clofazimine resistance in tuberculosis: an evolutionary medicine approach. bioRxiv 2021.03.19.43 6148. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Rivière, E.; Limberis, J.; Huo, S.; Metcalfe, J.Z.; Warren, R.M.; Van Rie, A. Genetic variants and their association with phenotypic resistance to bedaquiline in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review and individual isolate data analysis. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e604–e616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.C.; Kishony, R. Opposing effects of target overexpression reveal drug mechanisms. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, J.; Mailaender, C.; Etienne, G.; Daffé, M.; Niederweis, M. Multidrug resistance of a porin deletion mutant of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004, 48, 4163–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, M.; Réfregiers, M.; Pos, K.M. Mechanisms of envelope permeability and antibiotic influx and efflux in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Microbiol 2017, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The sensitivity of Msm, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965 to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; MsmΔ1380, MSMEG_1380 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ0965, MSMEG_0965 knockout Msm strain. CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 1.

The sensitivity of Msm, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965 to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; MsmΔ1380, MSMEG_1380 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ0965, MSMEG_0965 knockout Msm strain. CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 2.

The sensitivity of recombinant strains to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; Msm::1380, MSMEG_1380 overepression Msm strain; MsmΔ1380, MSMEG_1380 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ1380::C1380, MSMEG_1380 complemented MsmΔ1380 strain; Msm::0965, MSMEG_0965 overepression Msm strain; MsmΔ0965, MSMEG_0965 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ0965::C0965, MSMEG_0965 complemented MsmΔ0965 strain. BTZ, bortezomib; LZD, linezolid; CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 2.

The sensitivity of recombinant strains to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; Msm::1380, MSMEG_1380 overepression Msm strain; MsmΔ1380, MSMEG_1380 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ1380::C1380, MSMEG_1380 complemented MsmΔ1380 strain; Msm::0965, MSMEG_0965 overepression Msm strain; MsmΔ0965, MSMEG_0965 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ0965::C0965, MSMEG_0965 complemented MsmΔ0965 strain. BTZ, bortezomib; LZD, linezolid; CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 3.

The sensitivity of single gene-edited strains to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion mutation in MSMEG_1380; Msm-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 400insCC insertion mutation in MSMEG_0965. CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 3.

The sensitivity of single gene-edited strains to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion mutation in MSMEG_1380; Msm-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 400insCC insertion mutation in MSMEG_0965. CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 4.

Dual mutations of MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 in Msm affect Msm sensitivity to various antibiotics. (A) The sensitivity of Msm and MsmΔ1380Δ0965 to various antibiotics. (B) The sensitivity of Msm and Msm-1380e12insC-0965e400insCC to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; MsmΔ1380Δ0965, MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 double knockout Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion in MSMEG_1380 and a 400insCC insertion in MSMEG_0965. CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 4.

Dual mutations of MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 in Msm affect Msm sensitivity to various antibiotics. (A) The sensitivity of Msm and MsmΔ1380Δ0965 to various antibiotics. (B) The sensitivity of Msm and Msm-1380e12insC-0965e400insCC to various antibiotics. Msm: wide type Msm strain; MsmΔ1380Δ0965, MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 double knockout Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion in MSMEG_1380 and a 400insCC insertion in MSMEG_0965. CFZ, clofazimine; BDQ, bedaquiline; MOX, moxifloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin.

Figure 5.

MSMEG_0965 affects cell wall permeability in Msm. (A) EtBr accumulation in Msm and Msm-R1-2. (B) EtBr accumulation in single knockout strains. (C) EtBr accumulation in single gene-edited strains. (D) EtBr accumulation in double knockout and double gene-edited strains. ****, P < 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, n=3. Msm: wide type Msm strain; Msm-R1-2, BTZ-resistant strains; MsmΔ1380, MSMEG_1380 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ0965, MSMEG_0965 knockout Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion mutation in MSMEG_1380; Msm-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 400insCC insertion mutation in MSMEG_0965; MsmΔ1380Δ0965, MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 double knockout Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion in MSMEG_1380 and a 400insCC insertion in MSMEG_0965.

Figure 5.

MSMEG_0965 affects cell wall permeability in Msm. (A) EtBr accumulation in Msm and Msm-R1-2. (B) EtBr accumulation in single knockout strains. (C) EtBr accumulation in single gene-edited strains. (D) EtBr accumulation in double knockout and double gene-edited strains. ****, P < 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, n=3. Msm: wide type Msm strain; Msm-R1-2, BTZ-resistant strains; MsmΔ1380, MSMEG_1380 knockout Msm strain; MsmΔ0965, MSMEG_0965 knockout Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion mutation in MSMEG_1380; Msm-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 400insCC insertion mutation in MSMEG_0965; MsmΔ1380Δ0965, MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965 double knockout Msm strain; Msm-1380e12insC-0965e400insCC, Msm strain with a 12insC insertion in MSMEG_1380 and a 400insCC insertion in MSMEG_0965.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the mechanism underlying high-level resistance to BTZ and LZD in Msm harboring mutations in MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the mechanism underlying high-level resistance to BTZ and LZD in Msm harboring mutations in MSMEG_1380 and MSMEG_0965.

Table 1.

MICs of various antibiotics against BTZ-resistant Msm strains.

Table 1.

MICs of various antibiotics against BTZ-resistant Msm strains.

| Strains |

MICs (μg/mL) |

| BTZ |

LZD |

CLR |

EMB |

GEN |

LEV |

AMK |

STR |

| Msm |

5 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| Msm-R1-2 #

|

80 |

128 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

0.25 |

| Msm-R1-13 #

|

>80 |

4 |

8 |

1 |

8 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

0.25 |

| Msm-R3-2 #

|

80 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

1 |

| Msm-R4-1 #

|

80 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| Msm-R4-7 #

|

80 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.5 |

1 |

0.5 |

Table 2.

MICs of BTZ against Msm, MsmΔ3244, MsmΔ5085, MsmΔ3987, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965.

Table 2.

MICs of BTZ against Msm, MsmΔ3244, MsmΔ5085, MsmΔ3987, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965.

| Strains |

BTZ MIC (μg/mL) |

| Msm |

5 |

| MsmΔ3244

|

5 |

| MsmΔ5085

|

5 |

| MsmΔ3987

|

5 |

| MsmΔ1380

|

20 |

| MsmΔ0965

|

20 |

Table 3.

MICs of LZD against Msm, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965.

Table 3.

MICs of LZD against Msm, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965.

| Strains |

LZD MIC (μg/mL) |

| Msm |

2 |

| MsmΔ1380

|

8 |

| MsmΔ0965

|

8 |

Table 4.

MICs of multi-drugs against Msm, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965.

Table 4.

MICs of multi-drugs against Msm, MsmΔ1380, and MsmΔ0965.

| Strains |

MICs (μg/mL) |

| VAN |

CLR |

SDZ |

SMX |

| Msm |

8 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| MsmΔ1380

|

32 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| MsmΔ0965

|

32 |

16 |

8 |

16 |

Table 5.

MICs of multi-drugs against single gene-edited strains.

Table 5.

MICs of multi-drugs against single gene-edited strains.

| Strains |

MICs (μg/mL) |

| BTZ |

LZD |

VAN |

CLR |

SDZ |

SMX |

| Msm |

5 |

2 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| Msm-1380e12insC

|

20 |

8 |

32 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| Msm-0965e400insCC

|

20 |

8 |

32 |

16 |

8 |

16 |

Table 6.

MICs of multi-drugs against single gene-edited strains.

Table 6.

MICs of multi-drugs against single gene-edited strains.

| Strains |

MICs (μg/mL) |

| BTZ |

LZD |

VAN |

CLR |

SDZ |

SMX |

| Msm |

5 |

2 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| MsmΔ1380Δ0965

|

80 |

128 |

128 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

| Msm-1380e12insC-0965e400insCC

|

80 |

128 |

128 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

| MsmΔ1380Δ0965::C1380C0965

|

80 |

128 |

128 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).