Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

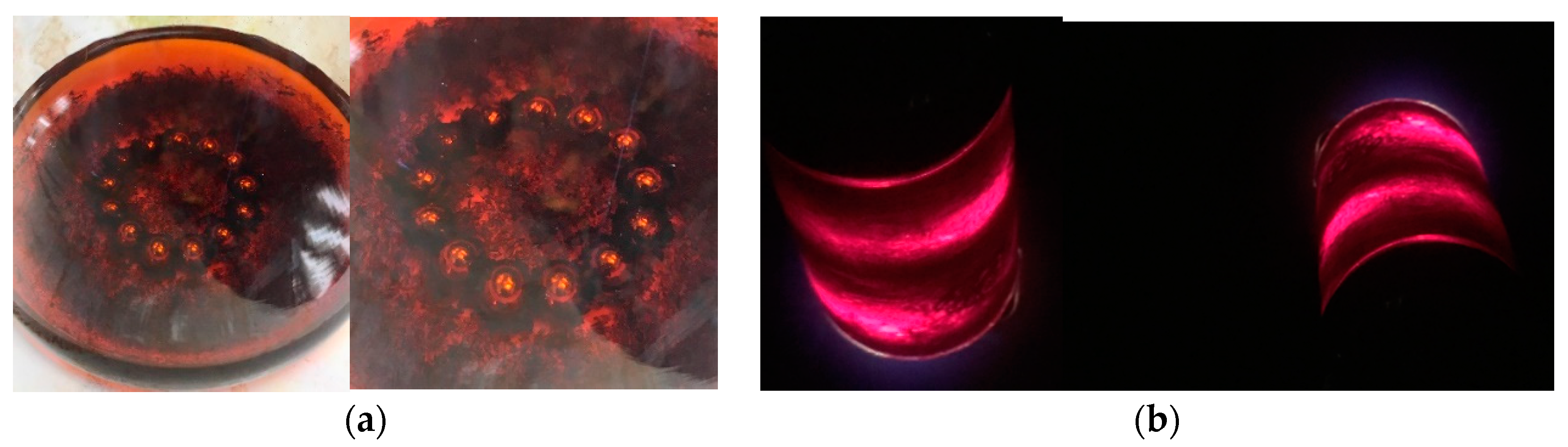

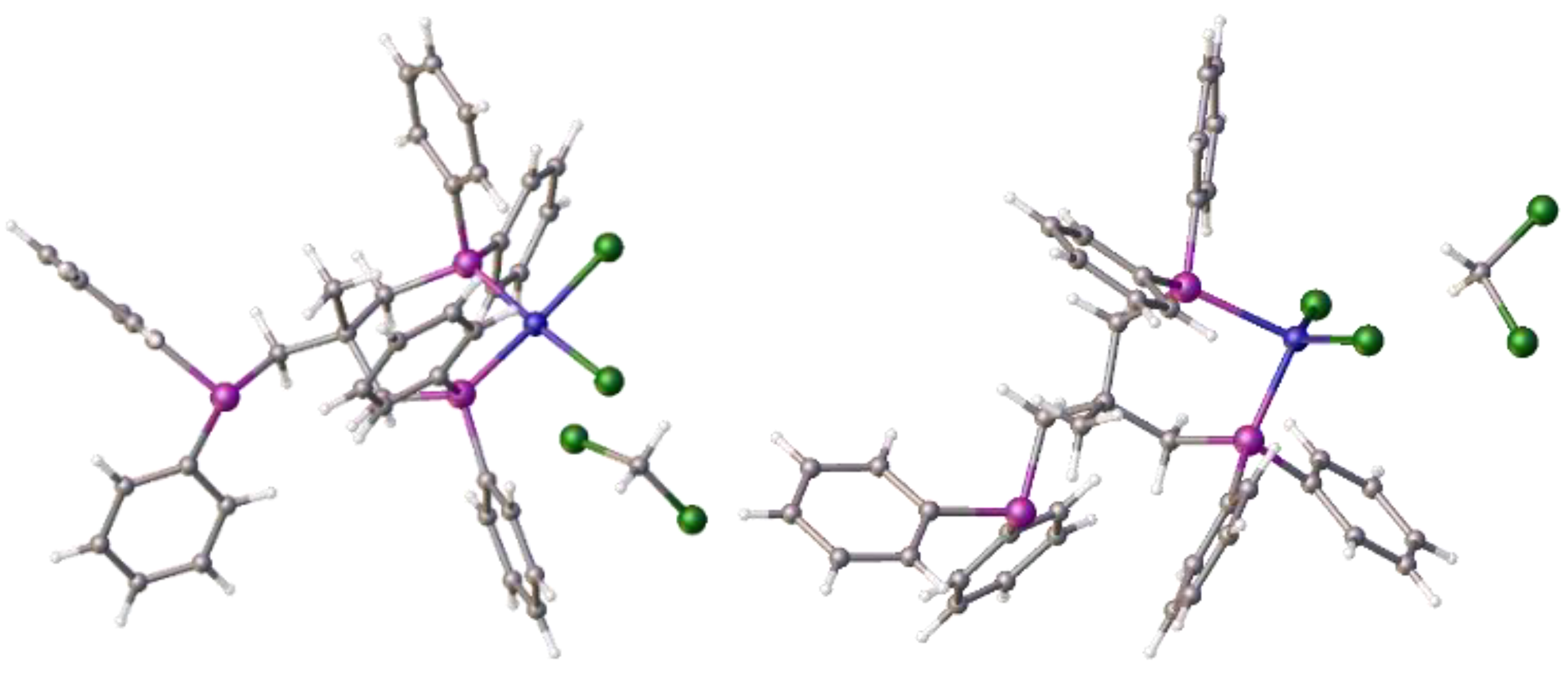

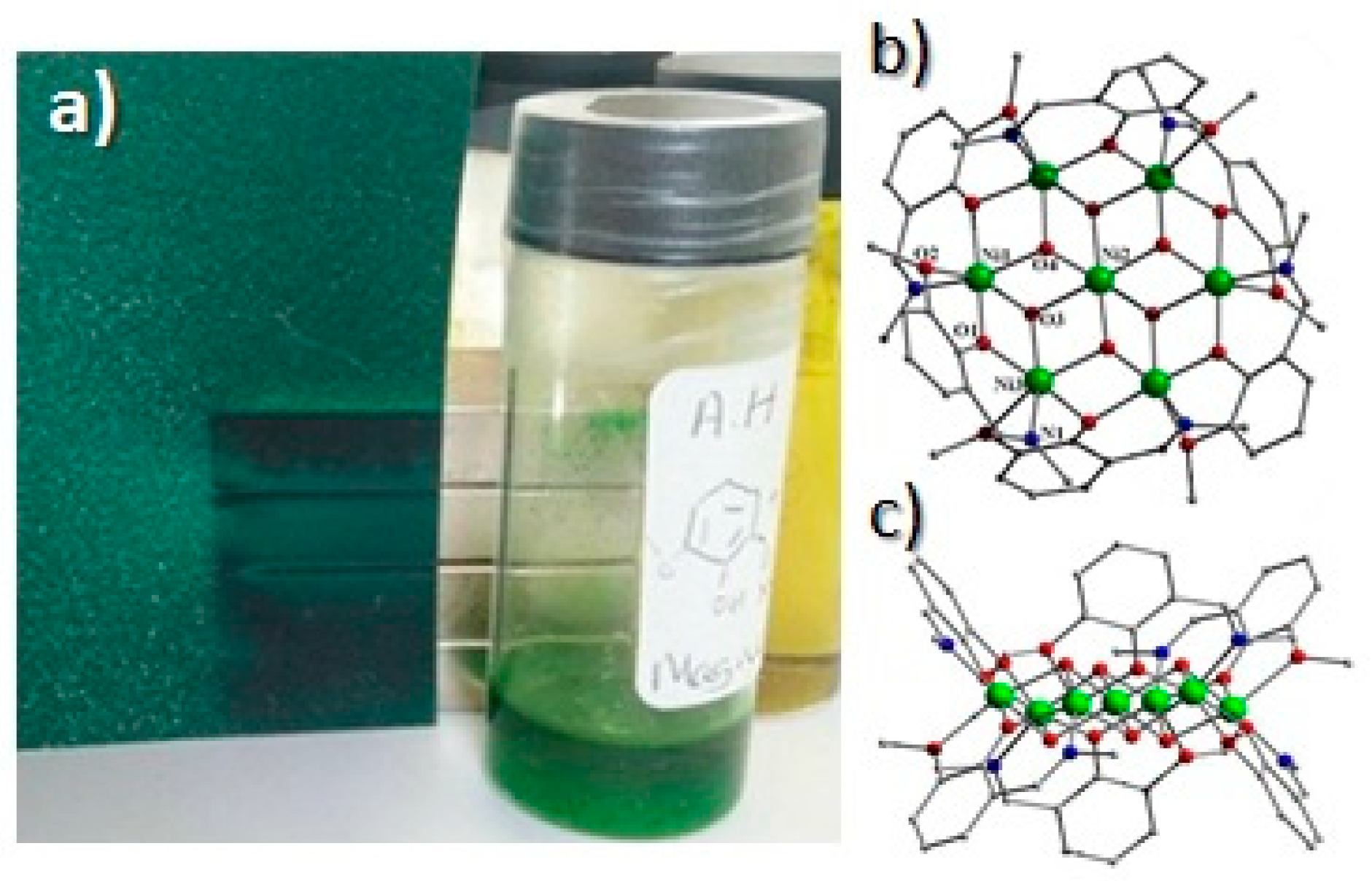

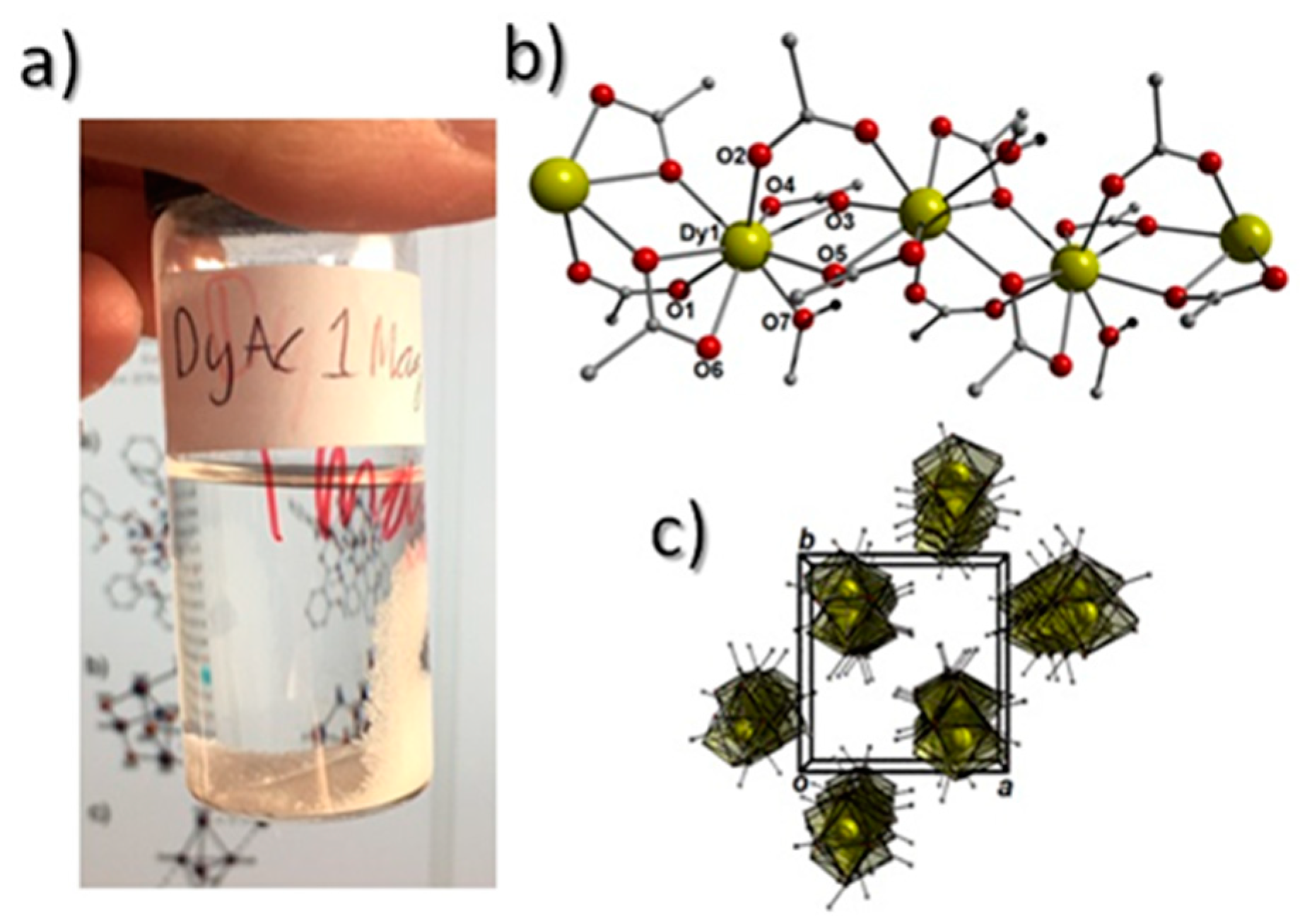

The crystallization of nickel (II) bis-phosphine and nickel and zinc cluster complexes have been carried out in localized magnetic fields set up using neodymium magnets, including custom made Magnetic Crystallization Towers (MCTs). In all cases, whether the product complex is diamagnetic or paramagnetic, a complex spatial patterning of the crystals occurs based on the orientation of the magnetic field lines. The effects of nucleation, and solution concentration gradients on the crystallization process are also explored. These observations therefore show how the crystallization process is affected by magnetic fields and thus these results have far-reaching effects which most certainly will include crystallization and ion migrations in biology.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Part A Nickel Phosphine Complexes

2.2. Part B: Nickel and Zinc Cluster Complexes

3. Concluding Comments

4. Materials and Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dechambenoit, P.; Long, J.R. Microporous magnets, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2011, 40, 3249–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Pineda, F.A.; Blasco-Ahicart, M. , Castro, N. ; López, D.N.; Galán-Mascarós. J.R. Direct magnetic enhancement of electrocatalytic water oxidation in alkaline media, Nat. Energy, 2019, 4, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, U.E.; Ulrich, T. Magnetic field effects in chemical kinetics and related phenomena, Chem. Rev., 1989, 89, 51–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, E.-K.; Zhang, C.-Y.; He, J.; Yin, D.-C. An Overview of Hardware for Protein Crystallization in a Magnetic Field, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, Z. , Wang, H. ; Qu, Z.; Chen, Q. Tuning the structure and properties of a multiferroic metal-organic-framework via growing under high magnetic fields, RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 13675–13678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meihaus, K.R.; Corbey, J.F.; Fang, M.; Ziller, J.W.; Long, J.R.; Evans, W.R. Separating rare earth complexes using a commercial bar magnet, Inorg. Chem., 2014, 53, 3099–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potticary, J.; Hall, C.L.; Guo, R.; Price, S.L. ; Hall. S.R. On the Application of Strong Magnetic Fields during Organic Crystal Growth, Crystal Growth & Design, 2021, 21, 6254–6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakayama, N.I. Effects of a Strong Magnetic Field on Protein Crystal Growth, Cryst. Growth and Design, 2003, 3, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, E. Molecular magnetism: from chemical design to spin control in molecules, materials and devices. Nat Rev Mater, 2020, 5, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Tong, M.-L. Single-molecule magnets beyond a single lanthanide ion: the art of coupling, Chem. Sci., 2022, 13, 8716–8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, D.N.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Layfield, R.A. Lanthanide single-molecule magnets, Chem. Rev., 2013, 113, 5110–5148. [Google Scholar]

- V. Kozhevnikov. Meissner Effect: History of Development and Novel Aspects, J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2021, 34, 1979–2009. [CrossRef]

- Essén, H.; Fiolhais, M.C.N. Meissner effect, diamagnetism, and classical physics—a review, Am. J. Phys., 2012, 80, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, J.A.; Grant, M.J.; Malone, L.; Putzke, C.; Kaczorowski, D.; Wolf, T.; Hardy, F.; Meingast, C.; Analytis, J.G.; Chu, J.-H.; Fisher, I.R.; Carrington, A. Observation of the non-linear Meissner effect, Nature Commun. , 2022, 13, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pollner, B.; Paulitsch-Fuchs, A.H.; Fuchs, E.C.; Dyer, N.P.; Loiskandl, W.; Lass-Flörl, C. Investigation of the effect of sustainable magnetic treatment on the microbiological communities in drinking water, Environmental Research. 2022, 213, 113628. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Jiang, W.; Xu, P. A critical review of the application of electromagnetic fields for scaling control in water systems: mechanisms, characterization, and operation NPJ Clean Water. 2020, 3, 25. [CrossRef]

- Coey, J.M.D.; Cass, S. Magnetic water treatment, J. Magnetism and Mag. Mater., 2000, 209, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, F.; Tlili, M.M.; Ben Amor, M.; Maurin, G.; Gabrielli, C. Influence of magnetic field on calcium carbonate precipitation, Chem. Eng and Processing: Process Intensification. 2009, 48, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakayama, N.I. Effects of a Strong Magnetic Field on Protein Crystal Growth. Cryst. Growth and Design. 2003, 3, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Ohtsuka, J.; Kashiwagi, T.; Numoto, Hirota, N.; Ode, T.; Okada, H.; Nagata, K.; Kiyohara, M.; Suzuki, E.; Kita, A.; Wada, H.; Tanokura, M. In-situ and real-time growth observation of high-quality protein crystals under quasi-microgravity on earth, Sci. Reports., 2016, 6, 22127. [CrossRef]

- Yin. D.-C. Prog. Protein crystallization in a magnetic field, Cryst. Growth and Charact. Mat., 2015, 61, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Quiroz-Garcia, B.; Yokaichiya, F.; Stojanoff, V.; Rudolph, P. Protein crystal growth in gels and stationary magnetic fields. Cryst. Res. Technol., 2007, 42, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, S.; Hagiwara, M. Contactless crystallization method of protein by a magnetic force booster, Sci. Reports. 2022, 12, 17287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.B.J.; Bwambok, D.K.; Chen, J.; Chopade, P.D.; Thuo, M.M.; Mace, C.R.; Mirica, K.A.; Kumar, A.A.; Myerson, A.S.; Whitesides, G.M. Using Magnetic Levitation to Separate Mixtures of Crystal Polymorphs, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10208–10211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahamsson, C.K; Nagarkar, A.; Fink, M.J.; Preston, D.J.; Ge, S.; Bozenko Jr, J.S.; Whitesides, G.M. Analysis of Powders Containing Illicit Drugs Using Magnetic Levitation, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl., 2020, 132, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Hu, Z. Wang, H. Wang H, Z. Qu and Q. Chen. Tuning the structure and properties of a multiferroic metal–organic-framework via growing under high magnetic fields. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 13675–13678. [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.L.; Luo, Y.-H.; He, Z.-T.; He, C.; Zheng, Z.-Y.; Su, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.-Y. ; Chen, C; Sun, B. -W. Molecular Disorder Induced by the Application of an External Magnetic Field during Crystal Growth, J. Phys. Chem., 2019, 123, 15230–15235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meihaus, K.R.; Corbey, J.F.; Fang, M.; Ziller, J.W.; Long, J.R.; Evans, W.J. Influence of an Inner-Sphere K+ Ion on the Magnetic Behavior of N23– Radical-Bridged Dilanthanide Complexes Isolated Using an External Magnetic Field, Inorg. Chem., 2014, 53, 3099–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, R.F.; Cheisson, T.; Cole, B.E.; Manor, B.C.; Carroll, P.J.; Schelter, E.J. Magnetic Field Directed Rare-Earth Separations Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2019, 58, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee-Ghosh, K.; Dor, O.B.; Tassinari, F.; Capua, E.; Yochelis, S.; Capua, A.; Yang, S.-H.; Parkin, S.S.P.; Sarkar, S.; Kronik, L. Baczewski, L. T.; Naaman, R.; Paltiel, Y. Separation of enantiomers by their enantiospecific interaction with achiral magnetic substrates, Science, 2018, 360, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Pineda, F.A.; Blasco-Ahicart, M.; Nieto-Castro, D.; López, N.; Galán-Mascarós, J.R. Direct magnetic enhancement of electrocatalytic water oxidation in alkaline media, Nature Energy, 2019, 4, 519-525. [CrossRef]

- Clevenger, A.L.; Stolley, R.M.; Aderibigbe, J.; Louie, J. Trends in the Usage of Bidentate Phosphines as Ligands in Nickel Catalysis. Chem. Revs. 2020, 120, 6124–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacot, T.J. Ferrocenyl Phosphine Complexes of the Platinum Metals in Non-Chiral Catalysis. Their Applications in Carbon—Carbon and Carbon—Heteroatom Coupling Reactions. Platinum Metals Rev., 2001, 45, 22-30. [CrossRef]

- Young, D.J.; Chienb, S.W.; Hor, T.S.A. 1,1’-Bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene in functional molecular materials, Dalton Trans. , 2012, 41, 12655–12665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataro, C.; Campbell, A.N.; Ferguson, M.A.; Incarvito, C.D.; Rheingold, A.L. Group 10 metal compounds of 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (dppf) and 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ruthenocene: a structural and electrochemical investigation. X-ray structures of [MCl2(dppr)] (M=Ni, Pd), J. Organometal. Chem., 2003, 673, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevenger, A.L.; Stolley, R.M.; Aderibigbe, J.; Louie, J. Trends in the usage of bidentate phosphines as ligands in nickel catalysis, Chem. Revs., 2020, 120, 6124–6196. [Google Scholar]

- Meally, S.T.; McDonald, C.; Karotsis, G.; Papaefstathiou, G.S.; Brechin, E.K.; Dunne, P.W.; McArdle, P.; Power, N.P.; Jones L.F. A family of double-bowl pseudo metallocalix[6]arene discs, Dalton Trans, 2010, 39, 4808-4816. [CrossRef]

- Meally, S.T.; Karotsis, G.; Brechin, E.K.; Papaefstathiou, G.S.; Dunne, P.W.; McArdle, P. , Jones, L. F. Planar [Ni7] discs as double-bowl, pseudo metallacalix[6]arene host cavities, Cryst. Eng. Comm., 2010, 12, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazari, N., Melvin, P.; Beromi, M. Well-defined nickel and palladium precatalysts for cross-coupling, Nat. Rev. Chem., 2017, 1, 0025. [CrossRef]

- Casellato, U.; Ajó, D.; Valle, G.; Corain, B.; Longato, B.; Graziani, R. Heteropolymetallic complexes of 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino) ferrocene (dppf). II. Crystal structure of dppf and NiCl2(dppf), J. Cryst. Spect. Res., 1988, 18, 583–590. [CrossRef]

- This complex [C6H4-CH2PtBu2¬-2-C6H4-CH2P(H)tBu2)2NiCl3, is prepared reaction of the ligand [1,2-C6H4-(CH2PtBu2)2] with [Ni(DME) NiCl2] in dichloromethane. Further information is included in supplementary materials.

- Hashimoto, T.; Ishimaru, T.; Shiota, K.; Yamaguchi, Y. Bottleable NiCl2(dppe) as a catalyst for the Markovnikov-selective hydroboration of styrenes with bis(pinacolato)diboron. Chem. Commun., 2020, 56, 11701-11704. [CrossRef]

- Busby, R.; Hursthouse, M.B.; Jarrett, P.S.; Lehmann, C.W.; Malik, K.M.A.; Phillips, C. Dimorphs of [1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane]dichloronickel(II), J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans., 1993, 3767-3770. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, H.N.; Jonassen, H.B.; Aguiar, A.M. , Nickel (II) and cobalt (II) complexes of cis - 1,2, bis (diphenylphosphino) ethylene, Inorg. Chim. Acta, 1967, 1, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hecke, G.R; Horrocks, W.D. Ditertiary Phosphine Complexes of Nickel. Spectral, Magnetic, and Proton Resonance Studies. A Planar-Tetrahedral Equilibrium, Inorg. Chem. 1966, 5, 1968–1974. [CrossRef]

- For an extensive review on Nickel phosphines in catalysis see: Clevenger, A.L.; Stolley, R.M.; Aderibigbe, J.; Louie, J. For an extensive review on Nickel phosphines in catalysis see: Clevenger, A.L.; Stolley, R.M.; Aderibigbe, J.; Louie, J., Trends in the Usage of Bidentate Phosphines as Ligands in Nickel Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R. , Fergusson, J. E. Coordination chemistry of 1,1,1-tris-(bisphenylphosphinomethyl) ethane. II. Four and five coordinate complexes of cobalt(II) and nickel(II), Inorg. Chim. Acta., 1970, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis, E.F.; Filgueiras, C.A.L. ,1,1,1- Tris(diphenylphosphinemethyl)ethane complexes of nickel and platinum with tin, Transition Met. Chem., 1994, 19, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Chew, R.J.; Tang, H.M.; Madrahimov, S.; Bengali, A.A.; Fan, W.Y. Triphos nickel(II) halide pincer complexes as robust proton reduction electrocatalysts. Mol. Catalysis, 2020, 490, 110950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapporto, P.; Midollini, S.; Orlandini, A.; Sacconi, L. Complexes of cobalt, nickel, and copper with the tripod ligand 1,1,1-tris(diphenylphosphinomethyl)ethane (p3). Crystal structures of the [Co(p3)(BH4)] and [Ni(p3)(SO2)] complexes, Inorg. Chem., 1976, 15, 2768-2774. [CrossRef]

- Kandiah, M.; McGrady, G.S.; Decken, A.; Sirsch, P. [(Triphos)Ni(η2-BH4)]: An Unusual Nickel(I) Borohydride Complex, Inorg. Chem., 2005, 44, 8650–8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Yorita, K.; Kato, Y.; Structural lnterconversions of Dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine) nickel(II) in Various Solvents. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn., 1979, 52, 2465-2473. [CrossRef]

- Meally, S.T.; McDonald, C.; Kealy, P.; Taylor, S.M.; Brechin, E.K.; Jones, L.F. Investigating the solid state hosting abilities of homo- and hetero-valent [Co-7] metallocalix[6]arenes, Dalton Trans. , 2012, 41, 5610–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R.; Munoz, J.C.; Perec, M. Bis(μ-acetato-κ3O,O′:O′)bis[bis(acetato-κ2O,O′)diaquadysprosium(III)] tetrahydrate, Acta. Cryst. C. 2002, C58, m498–m500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.-Z.; Lan, Y.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Anson, C.E.; Powell, A.K. Polymerisation of the Dysprosium Acetate Dimer Switches on Single-Chain Magnetism. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 12566–12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).