1. Introduction

The government of Norway aims at growth of the salmon industry, but is faced with several challenges, including an annual large loss of money from the farmers due to disease and other production-related problems. Salmon lice infestation remains one of the great challenges for Atlantic salmon aquaculture, particularly during the seawater phase of production. Sea lice levels in salmon farms are under surveillance by The Norwegian Food Safety Authorities throughout the production period. It is a welfare issue for the fish and makes the fish vulnerable towards other diseases.

Lepeophtheirus salmonis is the species of greatest concern [

1,

2,

3] and the infestation status in each Norwegian fish farm is weekly reported in an open access website [

4].

After hatching

L. salmonis free swimming nauplii molt into the infective copepodite stage in about 2 to 5 days. This is followed by the chalimus stage that undergoes two molting stages before becoming a pre-adult or mobile stage [

3,

5,

6,

7]. Then they can move around on the surface of the fish and may also swim in the water column, where particularly the nauplii and copepodites display different vertical migration patterns in response to light [

8]. Finally mature female lice develop egg strings that hatch and propagate the lice infection [

6]. Medicinal treatments to combat

L. salmonis have increased, as well as resistance towards the chemicals [

9]. New approaches must be introduced, and one possibility is a vaccine.

A peptide vaccine can be developed by looking for proteins that the lice inject into the blood stream of the salmon [

10,

11]. The protein peroxiredoxin-2 was found to be a possible vaccine target, since it belongs to a family of ubiquitous multifunctional antioxidant proteins. Its main function is to eliminate peroxides generated during metabolism. A recombinant protein is too expensive as an immunogen, but a peptide vaccine from such a protein is less expensive to produce and might be a possibility. The aim of the present study was to test a peptide vaccine from the protein peroxiredoxin-2 that has proven to be effective towards lice in seawater tanks [

11]. The test was done in semi-commercial scale at a sea farm research facility where natural occurrence of salmon lice is a frequent problem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Facility and Animal Ethics

The vaccine trial with Atlantic salmon was conducted at the Knappen-Solheim fish farm (Locality number 13567), Matre Research Station, Institute of Marine Research, Norway, in accordance with relevant guidelines and approval granted by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (FOTS ID: 29785, 13 July 2022). The sea farm had 10 cages with experimental fish, where two experimental groups of salmon lice vaccinated postsmolt were reared in cages M4 and M9, and two control groups of postsmolt were reared in cages M5 and M8 (

Figure 1) in the period of 21.11.2022 – 21.12.2023. All groups were fed Skretting 9 mm feed (Premium 2500-50A), according to an automated feeding schedule during daylight. The surrounding cages kept other experimental groups of 2 - 5 Kg salmon in cages M1 – M3, M6 - M7 and 1 – 3 Kg rainbow trout (

Oncorhynchus mykiss) in cage M10, in the period January until middle of June 2023. Delousing fish with Salmosan™ were carried out in the surrounding fish groups M1 – M3 and M10 on 13.01.2023 and on 13.02.2023, and fish groups M6 – M7 on 22.02.2023. These treatments were performed onboard a well boat and the treatment water was collected in onboard tanks and emptied in the open sea outside Masfjorden, to avoid potential influence on fish farms and spawning areas for wild stocks.

2.2. Vaccination

A total of 32.000 salmon parr (hatched from AquaGen QTL-SHIELD roe) were fully vaccinated 30.08.2022 with the ordinary vaccines (Alpha JECT micro 6 and Alpha JECT micro 1 PD) used in Norwegian aquaculture to prevent infection in salmon growing at sea. The experimental subgroup of 2 x 8000 parr were then vaccinated 20.09.2022 as described by [

11] with a short peptide of 13 amino acids (NKEFKEVSLKDYT) at an average weight of 84

+ 5 g. The peptide was produced by ProImmune (Oxford, United Kingdom) with Montanide

TM as adjuvant and processed as a lyophilized powder with a purity of 98% with TFA (Tri fluoric acid) as the counter ion. The smoltified salmon were transferred to seawater 21.11.2022 in land-based tanks and further transported to the sea cages in the period 07.-09.12.2022 at an average weight of 140 g (136

+ 7 g in vaccinated and 143

+ 9 g in control groups).

2.3. Sampling and Evaluation

The vaccination side-effects on the fish were quantified by X-ray imaging of the vertebra column after slaughtering on 20.12.2023, and by observing melanin spots [

12] in organs and body cavity sections and adherence in body cavity sections (

Figure 2) at six sampling dates (n = 20 per cage) from 21.11.2022 until 20.12.2023, together with measurements of whole-body weight (n

> 100 per cage). The scores from melanin spots and adherence were in the range from 0 – 3, where 3 is the most severe score (modified from [

13]) which implied that the sum of scores from the three cavity sections could reach a maximum score of 9. Skin bleedings, external wounds and other welfare related scores like damaged fins, emaciated body and external malformations were also quantified in the range of 0 – 3. The eye health was generally fine without signs of cataract and no tapeworms (

Eubothrium sp.) were observed in the intestines during the experimental period. The overall mortality was 0,32 % in land-based tanks and 4,8 % in sea cages in the vaccinated groups, and 0,44 % in land-based tanks and 7,9 % in sea cages in the control groups, respectively. Most of the mortality was recorded in December 2022 – January 2023, due to predator attacks from cormorants (

Phalacrocorax carbo) and a minor incidence of mortality was observed on 20.07.2023, due to an episodic peak in aluminum from snow melting water in the surrounding rivers.

Specific daily growth rate (SGR %) was calculated (1) according to [

14]:

where W

1 and W

2 denote fish wet weights at sampling times T

1 and T

2, respectively.

The effect of the salmon lice vaccine against sea lice infestation in each of the four experimental cages was evaluated weekly by counting the numbers of sessile, mobile and mature female salmon lice (with or without egg strings) per fish in 20 salmon per cage (n=100 per cage on 26.06. and 26.10.2023). The fish were gently netted by a deeply submerged net, operated by a crane, and mildly sedated with 80 mg/l FinquelTM (100 % Tricaine mesylate) for a period of 5-10 minutes in bath before lice counting by experienced technicians with head lamp. Lost lice in sedation bath were also counted. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority gave a dispensation (30.12.2022) from the regulation to have up to 1 mature female salmon lice per salmon in the week nos. 16-21 and up to 2 mature female salmon lice per salmon for the rest of the trial period, in order to avoid delousing during the experimental period. The trial was terminated in December 2023.

2.4. Statistics

All statistical analyses [

15] were carried out in Statistica Ver.13.4.D.14. Due to non-normally distributed data, outliers (x

i) were removed if they could be identified according to equation 2.

where Q1 and Q3 are the 1st and 3rd quartiles and IQR is the inter quartile range. After removal of outliers, comparison of groups was done with a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for independent groups with significance level α = 0,05.

3. Results

3.1. Welfare, Growth and Sexual Maturation

Neither of the vaccinated nor the control groups showed any appearance of vaccination injuries on the vertebral column. Both the vaccinated and the control groups showed generally low and non-significant different internal melanin levels (50 % between 1,0 – 2,0) in the belly (

Figure 3a) in the autumn after vaccination and throughout the winter season. Thereafter the medians dropped from 1,5 in April to 1,0 in June and stayed low until slaughter in December. Melanin in organs (

Figure 3b) were significantly higher in the vaccinated groups (median = 2,9) than in the control groups (median = 1,8) in December 2022, whereafter the level in the vaccinated groups gradually dropped and became equal to the control groups from June until December 2023 when slaughtered.

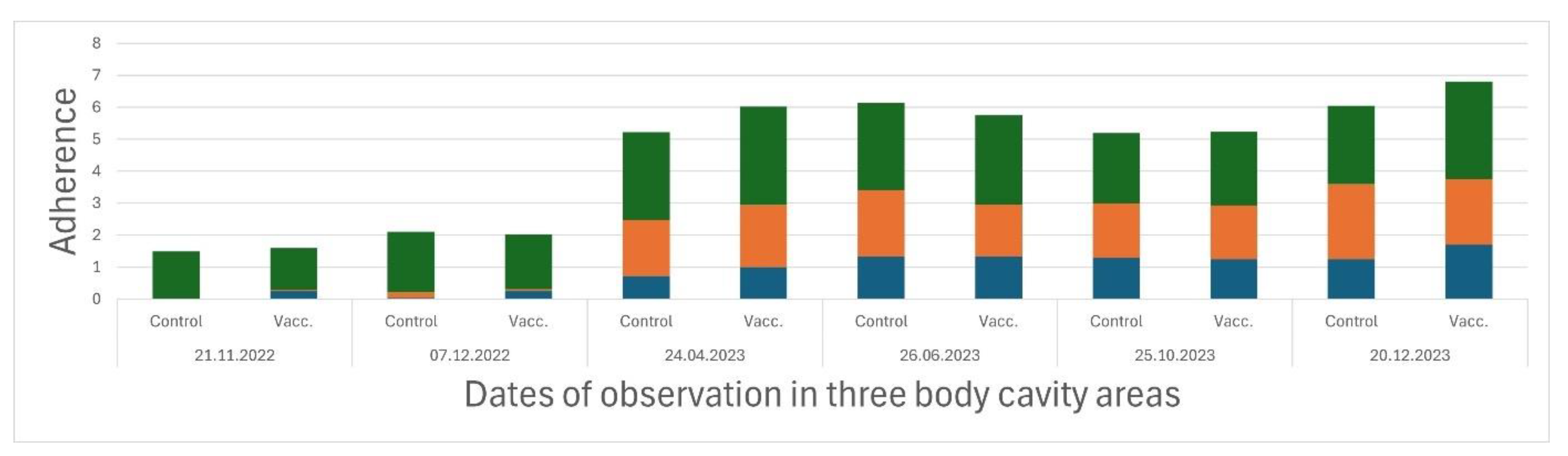

The adherence between the organs and the muscle segments in three internal body cavity regions were low and only appeared in section 3 (mid belly region) during the autumn after vaccination (

Figure 4). The levels of adherence increased significantly in all three evaluation sections in April 2023, however, no significant differences were observed between the vaccinated and the control groups, which showed stabilized adherence levels.

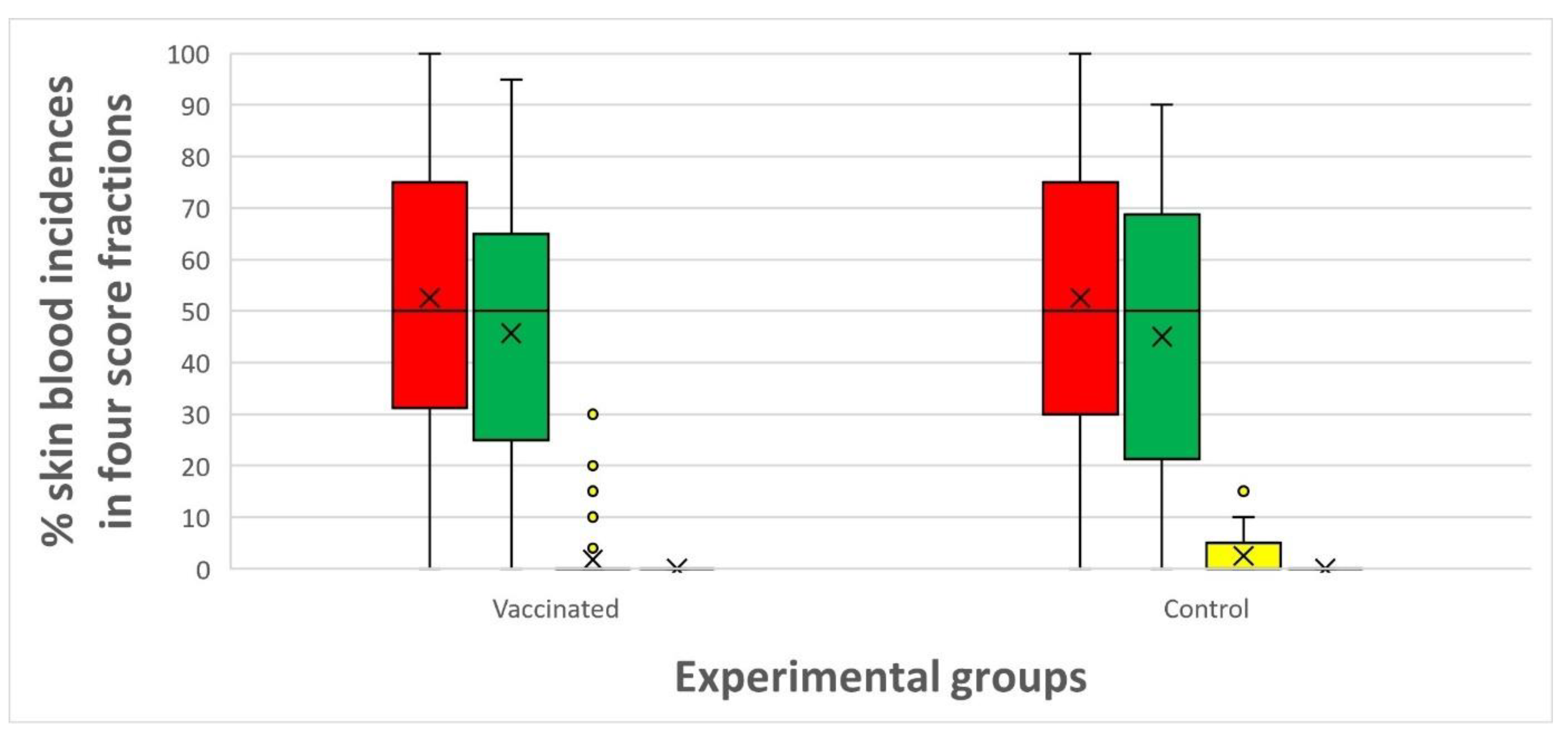

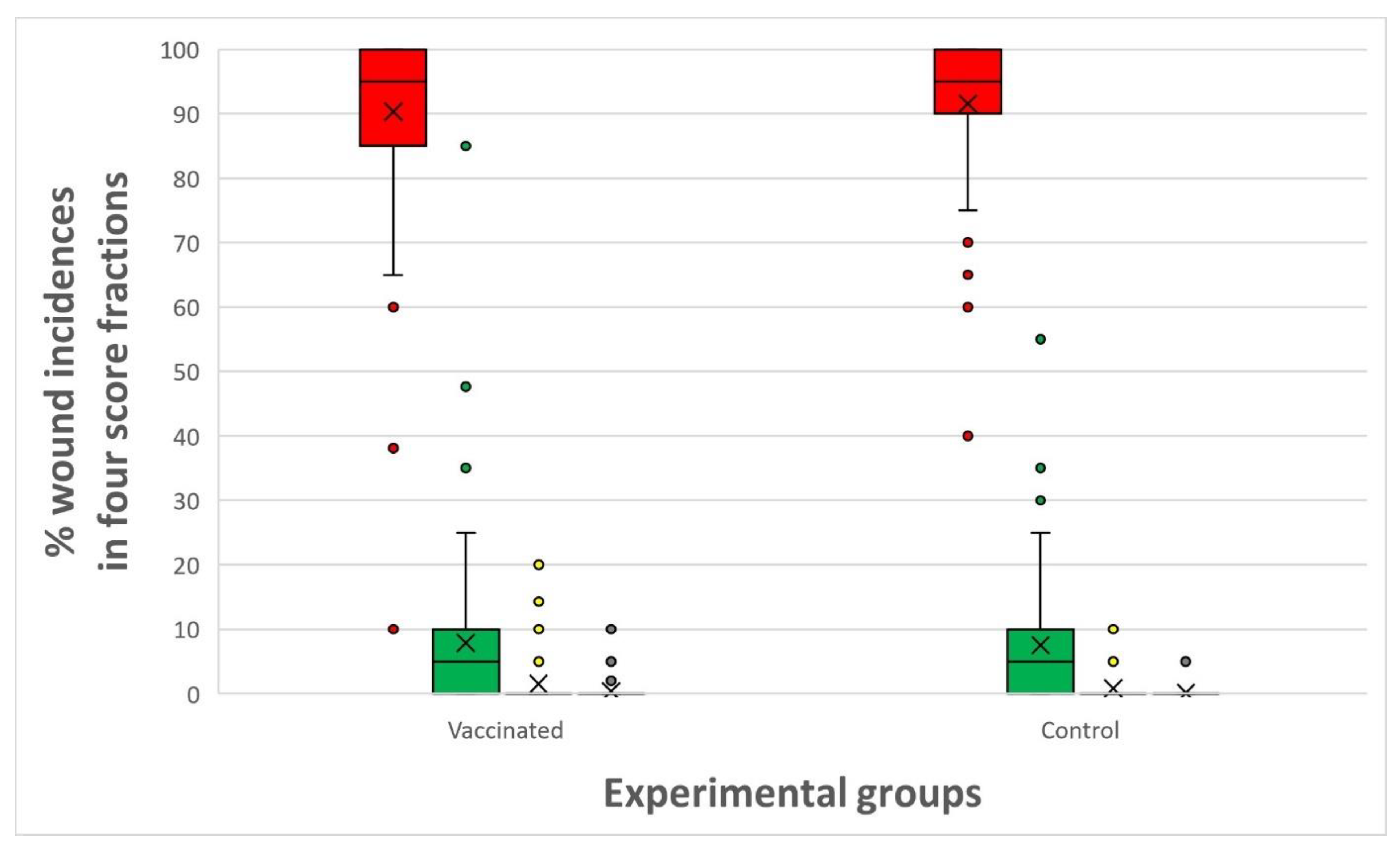

Both the vaccinated and the control groups showed generally low and non-significantly different levels of accumulated skin bleedings (

Figure 5) and wounds (

Figure 6) between the vaccinated and control groups. More than 95 % of the fish had minor appearance (scores 0 and 1) of skin bleedings and almost 100 % had minor appearance of wounds.

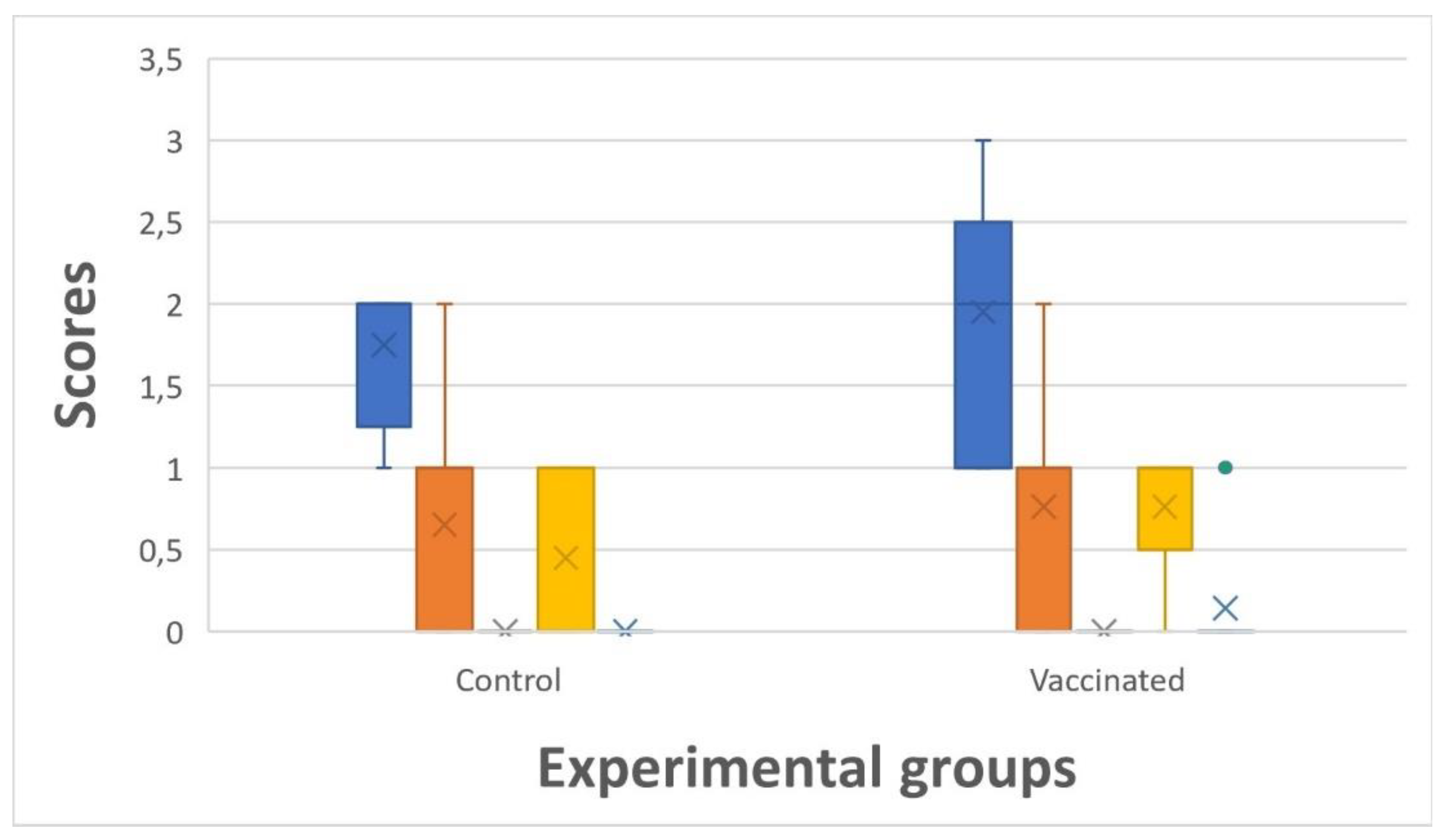

No significant differences were observed in welfare scores (fins, wounds, emaciated, scale loss and external malformations) at slaughter in vaccinated vs. control groups (

Figure 7). The highest accumulated median scores (1,9) were observed in fins, whereas median wounds and scale loss appeared between 0,5 – 0,8.

The smoltified salmon were on average 140 g at release into sea cages in December 2022, whereafter they showed a daily specific growth rate (SGR %) between 1,0 – 1,2 % until October 2023 (

Figure 8). From October to December 2023 the SGR dropped to 0,3 % and the final average round slaughter weights were 5,7 kg in the vaccinated groups and 5,9 kg in the control groups, however not significantly different. The maturation process had evidently started in the end of October in all groups when 20 – 30 % of the males showed initial prolongation of the jaws and appearance of jaw crook (Score 1,

Table 1), according to [

16]. Between October and the beginning of December this incidence had increased to 30 – 37 %, whereas 1 - 5 % of all the salmon in both the vaccinated and the control groups showed conspicuous spawning colours or thicker posterior part of their bodies at 04.12.2023 (Score 3,

Table 1). The slaughterhouse reported 84,7 % superior quality in the control group and 81,9 % superior quality in the vaccinated group at 20.12.2023, however not statistically significantly different.

3.2. Lice infestations

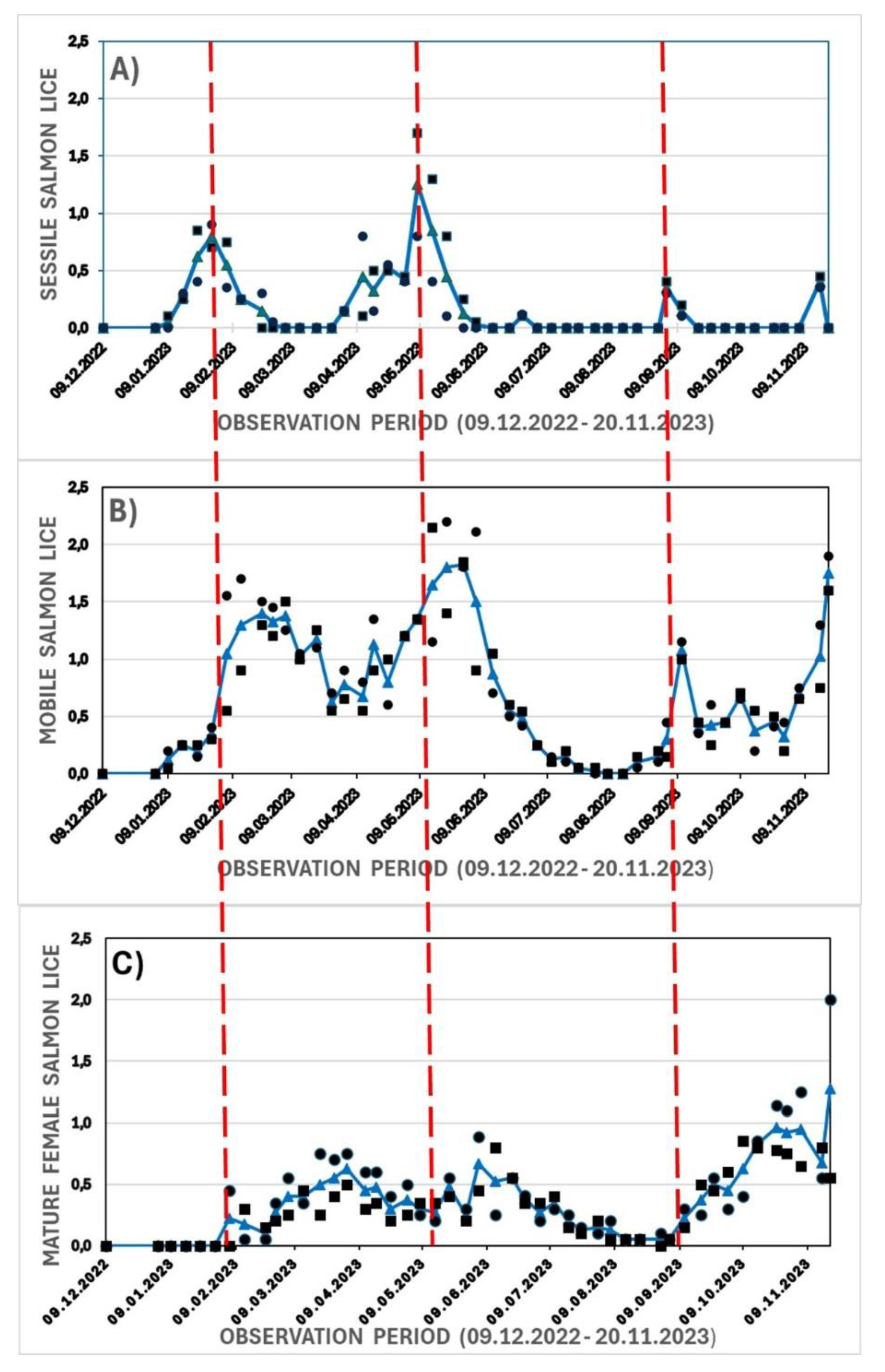

The occurrence of salmon lice infection showed four peaks of sessile stages throughout the experimental period within the control groups (

Figure 9a). The occurrence of sessile stages was consecutively followed by time delayed peaks or waves (red dotted lines in figures) of mobile and mature female stages, respectively (Figs. 9 b-c), in line with the lice development. A peak wave (0,6) of mature female stage per salmon was first observed in the second half of March 2023, followed by a peak in June and an increasing wave in October - November. The highest levels were observed by the end of November (single observations of > 2,0 mature female salmon lice per fish), and the experiment was thus terminated in December.

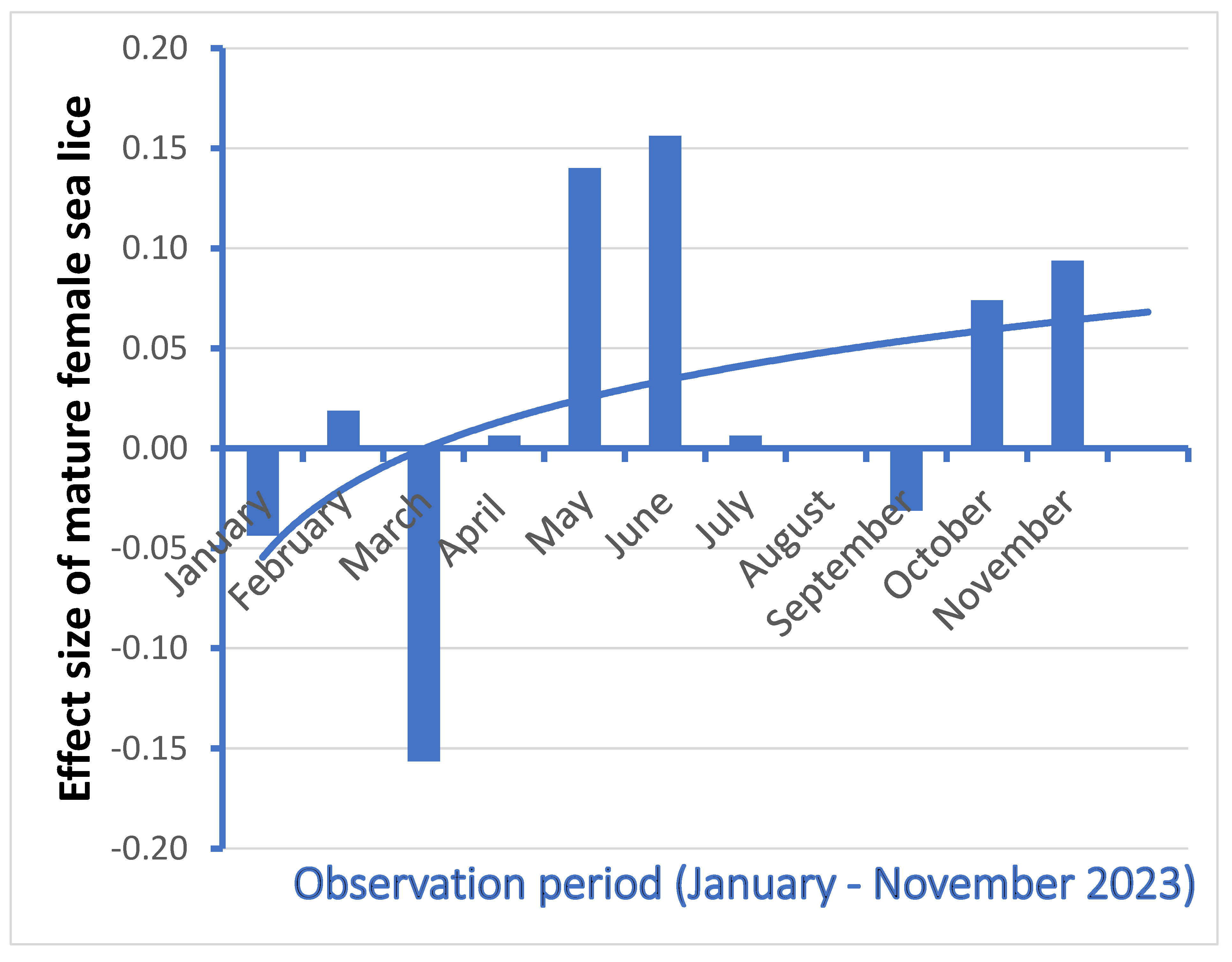

The weekly trend lines for the vaccinated groups (not shown here) followed the same general patterns as the control groups. The differences in nos. of mature female lice with egg strings between the control groups and the vaccinated groups were statistically significant (p = 0,03) in May, in favour of the vaccinated groups. The effect size (

Figure 10) showed a minor positive difference in 0,07 mature female salmon lice per salmon in favor of the vaccinated groups from May until November. No differences between control groups and vaccinated groups were observed for females without egg strings.

4. Discussion

4.1. Lice Preventive Methods

Barrett et al. [

17] have highlighted the benefits of the methods to prevent salmon lice infestation before they occur instead of treatment-focused methods, which all have negative effects on fish welfare [

18]. Meta-analysis of studies trialing the efficacy of excisting preventive methods concluded with a 76 % reduction in infestation density in cages with plankton mesh ‘snorkels’ or ‘skirts’, while the development of an effective vaccine still remains a key target [

17]. Lately, also submerged cages with air domes [

19] or access to air bubbles [

20] show promising reduction in lice infestation, however, these methods might also create production and welfare challenges [

21]. The alternative use of effective vaccines against salmon lice infestation would lower the costs for the farmers and the welfare issues for the fish.

4.2. The Semi-Commercial Approach

In the present semi-commercial scale trial with 8.000 fish per 2016 m3 cage (maximum biomass of 23,4 Kg/m3), there were no significant differences in welfare characteristics (melanin in belly or organs, adherence, skin bleedings or wounds, scale loss, fin or other external damages) between vaccinated and control groups. Moreover, no differences in the occurrence of emaciated fish, growth or incidence of maturation were observed between the groups. The X-ray images confirmed that neither of the vaccinated nor the control groups showed any appearance of vaccination injuries on the vertebral column. We were thus not able to observe any negative effects from the vaccine or the vaccination procedure per se over the 12 months trial in the sea cages.

Other fish trials with salmon lice vaccines [

11,

22,

23,

24] have been carried out in lab-scale, pointing out the necessity of validating the efficacy under large-scale trials and applications under field conditions. As the first vaccine study mimicking industrial conditions, we have also faced the challenges that are naturally occurring in a fish farm. First of all, the salmon was infested with copepodites of wild salmon lice when they naturally appeared, just as the salmon in commercial fish farms do. This is in contradiction to the controlled infestation rates in a lab. The infestation rates were generally lower in the present fjord system with periodic peaks of fresh water supply from the rivers, than is recorded in salmon farms in high salinity coast habitats [

4]. It has previously been shown that the abundance and distribution of fish lice increase in numbers under increased temperatures [

25,

26] and salinity [

27] and that the protective effects of snorkel barriers are strongly influenced by both salinity and temperature [

28]. Secondly, infestation and delousing of the other co-occurring fish groups in the present fish farm have probably influenced the copepodite infestation pressure towards our four experimental groups. However, this pressure was removed when the other groups were slaughtered in June.

Water currents probably had a more significant impact on the copepodite infestation pressure between the four experimental cages than natural variation in salinity and temperature. Nelson et al. [

29] also observed major effects on horizontal and vertical distribution of sea lice larvae in and around salmon farms. Salmon lice eggs and nauplii are spread from fish farms along the coast and from the outer part of the fjord into the present inner part where local current gyros appear and are partly mixing with the outward freshwater transport from the rivers and the hydroelectric power plants. Particularly the latter freshwater source has lately become quite unpredictable due to varying diurnal electricity production schemes. Locally, the dominant sea current direction from land side supplied pulses of salmon nauplii to the experimental cages. This resulted in peaks in copepodite infestation in the inner cages M4 and M5 before similar peaks were observed in M8 and M9, irrespective of vaccination status. Still, the experimental design with a diagonal spread of the experimental groups [

30] ensured that some significant results were obtained.

Another challenge with experimental groups in sea cages is the risk of fish mortality due to unplanned incidences from varying weather conditions, shifting water quality and predator attacks. Fortunately, the only significant mortality observed was attacks towards newly populated smolts from diving cormorants, restricted by mounting an extra preventive net outside the cages during the initial phase of the experiment, and mortality due to an episodic peak in aluminum from snow melting water in the surrounding rivers. Weekly sampling of salmon lice stages under the prevailing conditions was based on predetermined variability and statistical power analysis [

31]. A Standard Operating Procedure for validation of automatic louse counts has been developed and it was suggested a sampling size of 20 fish under high prevalence [

32]. This sampling size was applied weekly in the present trial and an increased sample size of 100 fish in the end of June confirmed the results in line with the sample size of 20 fish. Low fish mortality and an appropriate sample size should thus ensure that the harvested data from the semi-commercial approach were reliable.

4.3. The Vaccine Candidate

The novel approach of using a peptide from a protein as a vaccine instead of a cloned protein give new challenges. Vaccination with peptides always has a possibility of generating side effects, and an extra injection with a vaccine might also be harmful. However, as is shown through the figures compared with the control; growth rate was similar; melanin deposits are slightly and temporarily elevated due to the extra injection; and other welfare scores were also low and gave indiscriminate differences in fish welfare scores.

From the proof-of-concept article [

11] it is shown that the 70 % purified vaccine gave better protection towards lice infestation than the 98 % purified one. Upon high purification basic and acid side chains may react with each other forming an amide bound. This might change the structure of the peptide so much that the right immune stimulation was not achieved. The solubility of the peptide i.e. the HLB (hydrophile-lipophile-balance) in the adjuvant is also of importance. The peptide will have a distribution in the water-in-oil emulsion making it prone to attack from proteases in the blood stream.

The length of the peptide might also be important for its immunogenic potential. The bioinformatic model showed that the selected peptide is from a surface sequence of peroxiredoxin-2 [

11]. We believe this to be a linear sequence, but a 13 amino acid sequence may as well be coiled and do not necessarily mimic the surface sequence inducing the wanted ideal cellular immune response.

Preliminary experiments so far have given no indication of a humoral response, and we believe that a cellular MHC I response [

33] is more likely. This is based on the fact, that Atlantic salmon is an evolutionary old specie [

34], and MHC I is an old immune response system as well. According to this, even shorter peptide chains, 6-12 amino acids may stimulate the immune response. A shorter peptide sequence is also less expensive to produce, an advantage from a business point of view. Use of peptides as immune stimulants is a new technique, and the importance of length of peptides as well as sterically conformation is not known. From the above standing arguments, held together with the promising lab scale results [

11], it seems clear that further development of the vaccine should be a goal.

4.4. Effects on Salmon Lice

The weekly catch-and-release sampling strategy of 20 out of 8.000 salmon per sea cage by gently netting them by a deeply submerged net, ensured a low probability for repeated sampling of the same individual from month to month, thus a minimum influence on lice levels from repeated sampling was expected. Despite the before mentioned challenges with a semi-commercial approach and challenges related to the chosen peptide, the current trial has demonstrated preventive effects from the vaccine. The effect size (

Figure 10) showed a minor positive difference in 0,05 mature female salmon lice per salmon in favor of the vaccinated groups from May until November. This effect should be held together with the upper limit from the Norwegian Food Safety Authorities of 0,2 mature female salmon lice per salmon in the most critical period for smolt migration.

Contreras et al. [

22] and Tartor et al. [

24] have demonstrated immunization of Atlantic salmon against salmon lice infestation after vaccination with a salmon lice-gut recombinant protein P33. This protection seemed to be vaccine dose-dependent, where higher doses resulted in lower parasitic infestation rates. Both studies [

22,

24] showed a 35 % reduction in adult salmon lice females after P33 vaccination. The present study did, however, not test different vaccine doses.

The effect of the vaccine (

Figure 10) was lower than expected. At present we do not know sufficiently about the immune system in Atlantic salmon, and how the lice inhibit the immune system. Preliminary results show no humoral response, and it is probably a cellular response we observe. The antigenicity of the peptide used must be increased, and a better adjuvant has to be found.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S., A.J., E.D.-P. and R.N. validation, E.D.-P. and R.N.; formal analysis, R.N.; methodology, E.S., A.J., E.D.-P. and R.N; investigation, E.D.-P., L.P.A.B. and R.N.; resources, E.S.; data curation, E.D.-P. and R.N..; writing—original draft preparation, R.N. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S., R.N., L.P.A.B.; visualization, R.N. and E.D.-P.; supervision, R.N. and E.S.; project administration, R.N. and E.S.; funding acquisition, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Cape of good hope AS, Norway.

Ethics Statement

The animal study protocol was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Experiental Animal Administration Supervision and Application System (FOTS), the under the Norwegian Food Safety Authorities. The Norwegian Computing Center calculated, based on the probability of salmon lice infestation of farmed salmon in a fjord system, the need for 8.000 individual salmon in each sea cage to be able to find eventual differences between vaccinated and control groups. Power analysis was applied to calculate the need for weekly counting in each sea cage of at least 20 salmon for salmon infestation, 20 salmon for welfare aspects and 80 - 100 salmon for growth monitoring, depending on current population variance.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff and laboratory technicians at Matre Research Station, Institute of Marine Research, Norway for their assistance throughout the challenge study, specifically Trond Asheim, Magnus Fjelldal, Simon Flavell, Jan Olav Fosse, Marius Lund Halland, Karen Anita Kvestad, Truls Marøy, Ivar Helge Matre, Linda Neset, Kris Oldham, Audun Østby Pedersen, Håkon Torvik and Jan Even Østerbø.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors A.J. and E.S. are shareholders in the Cape of good hope AS, Norway. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bron, J.E.; Sommerville, C.; Jones, M.; Rae, G.H. The settlement and attachment of early stages of the salmon louse, Lepeophtheirus salmonis, (Copepoda: Caligidae) on the salmon host, Salmo salar. Journal of Zoology 1991, 224, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxaspen, K. Geographical and temporal variation in abundance of salmon lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) on salmon (Salmo salar L.). ICES Journal of Marine Science 1997, 54, 1144-1147. [CrossRef]

- Boxaspen, K. A review of the biology and genetics of sea lice. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2006, 63, 1304-1316. [CrossRef]

- Norwegian fish health. Available online: https://www.barentswatch.no/fiskehelse/ (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Johnson, S.C.; Albright, L.J. The developmental stages of Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Krøyer, 1837) (Copepoda: Caligidae). Can. J. Zool. 1991, 69, 929–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, L.A.; Eichner, C.; Caipang, C.M.A.; Dalvin, S.T.; Bron, J.E.; Nilsen, F.; Boxshall, G.; Skern-Mauritzen, R. The salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Copepoda: Caligidae) life cycle has only two chalimus stages. PLoS ONE 2013 8(9), e73539. [CrossRef]

- Eichner, C.; Hamre, L.A.; Nilsen, F. Instar growth and molt increments in Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Copepoda: Caligidae) chalimus larvae. Parasitology International 2015, 64, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szetey, A.; Wright, D.W.; Oppedal, F.; Dempster, T. Salmon lice nauplii and copepodids display different vertical migration patterns in response to light. Aquaculture Environment Interactions 2021, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaen, S.M.; Helgesen, K.O.; Bakke, M.J.; Kaur, K.; Horsberg, T.E. Drug resistance in sea lice: a threat to salmonid aquaculture. Trends in Parasitology 2015, 31, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slinde, E.; Johny, A.; Egelandsdal, B. Peptides for the inhibition of parasite infection. Patent filed and published as NO20211347A·2021-11-08; WO2023080791A1·2023-05-11 (can be accessed at Espacenet.com).

- Johny, A.; Ilardi, P.; Olsen, R.E.; Egelandsdal, B.; Slinde, E. A Proof-of-Concept Study to Develop a Peptide-Based Vaccine against Salmon Lice Infestation in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.). Vaccines 2024,12(5), 456-466. [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Løge-Hagen, A.S.; Dalum, A.S.; Erkinharju, T.; Midtlyng, P.J.; Aunsmo, A. A case of melanization after intramuscular vaccination in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) – Possible causes and implications. Journal of Fish Diseases 2023, 46, 1157-1161. [CrossRef]

- Midtlyng, P.J.; Reitan, L.J.; Speilberg, l. Experimental studies on the efficacy and side-effects of intraperitoneal vaccination of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) against furunculosis. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 1996, 6, 335 - 350. [CrossRef]

- Houde, E.D.; Schekter, R.C. Growth rates, rations and cohort consumption of marine fish larvae in relation to prey concentrations. Rapp. Proc. Réun. Cons. Int. Exp. Mer 1981, 178, 441-453.

- Sokal, R.R.; Rohlf, F.J. Biometry., 2nd ed.; W.H. Freeman and Co.: New York, USA, 1981; 859 p, ISBN 0-7167-1254-7. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, C.; Gismervik, K.; Iversen, M.H.; Kolarevic, J.; Nilsson, J.; Stien, L.H.; Turnbull, J.F. Welfare Indicators for farmed Atlantic salmon: tools for assessing fish welfare, FHF – Norwegian Seafood Research Fund: Tromsø, Norway, 2018; 351 p. ISBN 978-82-8296-556-9. http://www.nofima.no/fishwell/english.

- Barrett, L.T.; Oppedal, F.; Robinson, N.; Dempster, T. Prevention not cure: a review of methods to avoid sea lice infestations in salmon aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture 2020, 12, 2527–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, S.; Skern, R.; Saito, T.; Thompson, C. Optimising delousing strategies: Developing best practice recommendations for maximal efficacy and positive welfare. Final report No. 2023-29 from Institute of Marine Research, Norway 2023, 40 p., ISSN:1893-4536.

- Oppedal, F.; Folkedal, O.; Stien, L.H.; Vågseth, T.; Fosse, J.O.; Dempster, T.; Warren-Myers, F. Atlantic salmon cope in submerged cages when given access to an air dome that enables fish to maintain neutral buoyancy. Aquaculture 2020, 525, 735286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.T.; Larsen, L.-T.U.; Bui, S.; Vågseth, T.; Eide, E.; Dempster, T.; Oppedal, F.; Folkedal, O. Post-smolt Atlantic salmon can regulate buoyancy in submerged sea-cages by gulping air bubbles. Aquacultural Engineering 2024, 107, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren-Myers, F.; Vågseth, T.; Folkedal, O.; Stien, L.H.; Fosse, J.O.; Dempster, T.; Oppedal, F. Full production cycle, commercial scale culture of salmon in submerged sea-cages with air domes reduces lice infestation, but creates production and welfare challenges. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M.; Karlsen, M.; Villar, M.; Olsen, R.H.; Leknes, L.M.; Furevik, A.; Yttredal, K.L.; Tartor, H.; Grove, S.; Alberdi, P. Vaccination with Ectoparasite Proteins Involved in Midgut Function and Blood Digestion Reduces Salmon Louse Infestations. Vaccines 2020, 8(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, J.K.; Carpio, Y.; Johansen, L.-H.; Velazquez, J.; Hernandez, L.; Leal, Y.; Kumar, A.; Estrada, M.P. Impact of a candidate vaccine on the dynamics of salmon lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) infestation and immune response in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). PLoS ONE 2020, 15(10), 21p., e0239827. [CrossRef]

- Tartor, H.; Karlsen, M.; Skern-Mauritzen, R.; Monjane, A.L.; Press, C.M.; Wiik-Nielsen, C.; Olsen, R.H.; Leknes, L.M.; Yttredal, K.; Brudeseth, B.E.; Grove, S. Protective Immunization of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.) against Salmon Lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) Infestation. Vaccines 2022, 10, 16. [CrossRef]

- Hogans, W.E.; Trudeau, D.J. Preliminary studies on the biology of sea lice, Caligus elongatus, Caligus curtus and Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Copepoda: Caligoida) parasitic on the cage-cultured salmonids in the lower Bay of Fundy. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1989, 1715, iv +14 pp. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/mpo-dfo/Fs97-6-1715-eng.pdf.

- Nilsen, F. Recent advances in salmon louse research. Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists 2018, 38(3), 91-97. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326057591_Recent_advances_in_Salmon_louse_research.

- Arriagada, G.; Vanderstichel, R.; Stryhn, H.; Milligan, B.; Revie, C.W. Evaluation of water salinity effects on the sea lice Lepeophtheirus salmonis found on farmed Atlantic salmon in Muchalat Inlet, British Columbia, Canada. Aquaculture 2016, 464, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, T. Salinity and temperature alter the efficacy of salmon louse prevention. Aquaculture 2023, 575, 739673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.J.; Robinson, S.M.C.; Fiendel, N.; Sterling, A.; Byrne, A.; Pee Ang, K. Horizontal and vertical distribution of sea lice larvae (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) in and around salmon farms in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Journal of Fish Diseases 2017, 41, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, G.E.P.; Hunter, W.G.; Hunter, J.S. Statistics for experimenters – An introduction to design, data analysis, and model building. John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 1978; 653 p.

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences., 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Ass. Publishers: Hillsdale, New Jersey, USA, 1988; 567 p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, S.; Folkedal, O.; Nerbø, I.S.; Barrett, L.T. A Standard Operating Procedure for validation of automatic louse counts. Report No. 2024-56 from Institute of Marine Research, Norway 2024, 26 p.

- Roitt, I.M.; Brostoff, J.; Male, D.K. Immunology, 2nd ed.; Gower Medical Publishing: London, UK, 1989; p. 4.1-4.12. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, S.; Koop, B.F.; Sandve, S.R.; Miller, J.R.; Kent, M.P.; Nome, T.; Hvidsten, T.R.; Leong, J.S.; Minkley, D.R.; Zimin, A.; Grammes, F.; Grove, H.; Gjuvsland, A.; Walenz, B.; Hermansen, R.A.; von Schalburg, K.; Rondeau, E.B.; Di Genova, A.; Samy, J.K.A.; Vik, J.O.; Vigeland, M.D.; Caler, L.; Grimholt, U.; Jentoft, S.; Våge, D.I.; de Jong, P.; Moen, T.; Baranski, M.; Palti, Y.; Smith, D.R.; Yorke, J.A.; Nederbragt, A.J.; Tooming-Klunderud, A.; Jakobsen, K.S.; Jiang, X.; Fan, D.; Hu, Y.; Liberles, D.A.; Vidal, R.; Iturra, P.; Jones, S.J.M.; Jonassen, I.; Maass, A.; Omholt, S.W.; Davidson, W.S. The Atlantic salmon genome provides insights into rediploidization. Nature 2016, 533, 200-205 + 7p. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental set-up at Knappen-Solheim fish farm, located in Masfjorden, Norway with 10 cages (12 x 12 x 17 m). The two salmon lice vaccinated fish groups were reared in cages M4 and M9, whereas the two control groups were reared in cages M5 and M8. The dominant sea current direction from land side is indicated by the blue arrow.

Figure 1.

Experimental set-up at Knappen-Solheim fish farm, located in Masfjorden, Norway with 10 cages (12 x 12 x 17 m). The two salmon lice vaccinated fish groups were reared in cages M4 and M9, whereas the two control groups were reared in cages M5 and M8. The dominant sea current direction from land side is indicated by the blue arrow.

Figure 2.

Upper photo (A) by Erik Dahl-Paulsen: Evaluation sections (1 – 3) of internal vaccination effects. Lower photo (B) by Audun Østby Pedersen: X-ray image of anterior and posterior whole-body parts of vaccinated Atlantic salmon.

Figure 2.

Upper photo (A) by Erik Dahl-Paulsen: Evaluation sections (1 – 3) of internal vaccination effects. Lower photo (B) by Audun Østby Pedersen: X-ray image of anterior and posterior whole-body parts of vaccinated Atlantic salmon.

Figure 3.

A) Melanin in belly section and B) melanin in organs in vaccinated (orange) and control (blue) groups (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) from the period 21.11.2022 – 20.12.2023. The data are presented by the median values (X), 50 % interquartile range (IR in box), upper and lower quartile + 1,5 Interquartile range, respectively (whiskers) and eventual outliers.

Figure 3.

A) Melanin in belly section and B) melanin in organs in vaccinated (orange) and control (blue) groups (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) from the period 21.11.2022 – 20.12.2023. The data are presented by the median values (X), 50 % interquartile range (IR in box), upper and lower quartile + 1,5 Interquartile range, respectively (whiskers) and eventual outliers.

Figure 4.

Internal distribution of adherence (blue = section 1, orange = section 2 and green = section 3) in vaccinated and control fish (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) from the period 21.11.2022 – 20.12.2023.

Figure 4.

Internal distribution of adherence (blue = section 1, orange = section 2 and green = section 3) in vaccinated and control fish (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) from the period 21.11.2022 – 20.12.2023.

Figure 5.

Accumulated skin bleedings (scores 0 – 3) in vaccinated vs. control groups (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) throughout the experimental period. Red = % score of 0 appearance, green = % score of 1, yellow = % score of 2 and grey = % score of 3.

Figure 5.

Accumulated skin bleedings (scores 0 – 3) in vaccinated vs. control groups (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) throughout the experimental period. Red = % score of 0 appearance, green = % score of 1, yellow = % score of 2 and grey = % score of 3.

Figure 6.

Accumulated wounds (scores 0 – 3) in vaccinated vs. control groups (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) throughout the experimental period. Red = % score of 0 appearance, green = % score of 1, yellow = % score of 2 and grey = % score of 3.

Figure 6.

Accumulated wounds (scores 0 – 3) in vaccinated vs. control groups (n = 40 fish in each pooled group) throughout the experimental period. Red = % score of 0 appearance, green = % score of 1, yellow = % score of 2 and grey = % score of 3.

Figure 7.

Welfare scores (blue = fins, orange = wounds, grey = emaciated, yellow = scale loss, green = external malformations) at slaughter (20.12.2023) in vaccinated vs. control groups (n = 40 in each pooled group).

Figure 7.

Welfare scores (blue = fins, orange = wounds, grey = emaciated, yellow = scale loss, green = external malformations) at slaughter (20.12.2023) in vaccinated vs. control groups (n = 40 in each pooled group).

Figure 8.

Specific daily growth rate (SGR %) for vaccinated (orange) vs. control (blue) groups (n > 200 in each pooled group) in the period 09.12.2022 – 20.12.2023.

Figure 8.

Specific daily growth rate (SGR %) for vaccinated (orange) vs. control (blue) groups (n > 200 in each pooled group) in the period 09.12.2022 – 20.12.2023.

Figure 9.

Dynamic, wild salmon lice infection of sessile (A, red lines), mobile (B) and mature female lice (C) stages of two control groups in the period 09.12.2022 – 20.11.2023. Each legend represents the average lice level from 20 fish. Circles and squares represent parallel groups and solid line with triangles represent the average levels.

Figure 9.

Dynamic, wild salmon lice infection of sessile (A, red lines), mobile (B) and mature female lice (C) stages of two control groups in the period 09.12.2022 – 20.11.2023. Each legend represents the average lice level from 20 fish. Circles and squares represent parallel groups and solid line with triangles represent the average levels.

Figure 10.

Effect size (control – vaccinated) in mature female salmon lice per salmon in the period from January – November 2023. A logarithmic trend line is displayed.

Figure 10.

Effect size (control – vaccinated) in mature female salmon lice per salmon in the period from January – November 2023. A logarithmic trend line is displayed.

Table 1.

Average % incidence (from two cages) of sexual maturation (predominantly in males) in vaccinated (V) and control (C) groups, by visual external categorization in four categories, where score 0 = no signs of maturation, 1 = initial signs of maturation like prolongation of jaws and appearance of jaw crook, 2 = the skin is darker, mainly silvery, conspicuous prolongation of jaws in males, 3 = conspicuous spawning colours, brownish, the posterior part of the body is thicker than in immature salmon, according to [

16]. n = 20 fish from each cage, except for October when n = 100.

Table 1.

Average % incidence (from two cages) of sexual maturation (predominantly in males) in vaccinated (V) and control (C) groups, by visual external categorization in four categories, where score 0 = no signs of maturation, 1 = initial signs of maturation like prolongation of jaws and appearance of jaw crook, 2 = the skin is darker, mainly silvery, conspicuous prolongation of jaws in males, 3 = conspicuous spawning colours, brownish, the posterior part of the body is thicker than in immature salmon, according to [

16]. n = 20 fish from each cage, except for October when n = 100.

| Date |

Group |

Score 0 |

Score 1 |

Score 2 |

Score 3 |

| 07.02.2023 |

V |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 07.02.2023 |

C |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 24.04.2023 |

V |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 24.04.2023 |

C |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 26.06.2023 |

V |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 26.06.2023 |

C |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 26.08.2023 |

V |

97 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

| 26.08.2023 |

C |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 25.10.2023 |

V |

75 |

20 |

0 |

5 |

| 25.10.2023 |

C |

67 |

30 |

2 |

1 |

| 04.12.2023 |

V |

60 |

37 |

0 |

3 |

| 04.12.2023 |

C |

65 |

30 |

3 |

2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).