Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This review offers an in-depth analysis of microbial γ-poly-glutamic acid (γ-PGA), highlighting its production, biosynthetic pathways, unique properties, and extensive applications in the food and health industries. γ-PGA is a naturally occurring biopolymer synthesized by various microorganisms, particularly species of Bacillus. The report delves into the challenges and advancements in cost-effective production strategies, addressing the economic constraints associated with large-scale γ-PGA synthesis. Its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxic nature make it a promising candidate for diverse industrial applications. In the food industry, γ-PGA's exceptional water-holding capacity and humectant properties are key to its utility. These features enable it to enhance the stability, viscosity, and shelf life of food products, making it a valuable ingredient in processed foods. The review highlights its ability to improve the textural quality of baked goods, stabilize emulsions, and act as a protective agent against staling. Beyond food applications, γ-PGA's role in health and pharmaceuticals is equally significant. Its use as a drug delivery carrier, vaccine adjuvant, and biofilm inhibitor underscores its potential in advanced healthcare solutions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Polyglutamic Acid (PGA)

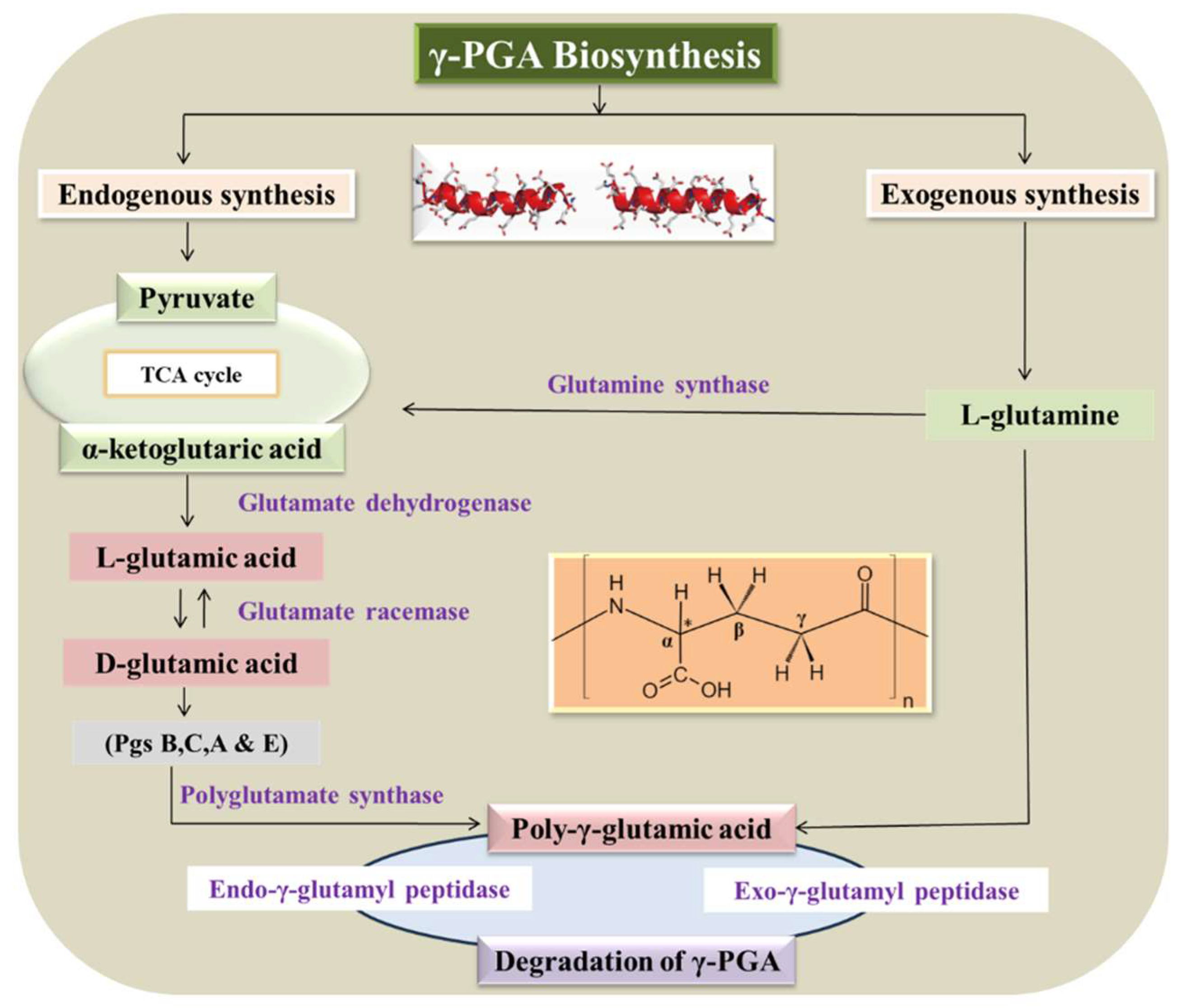

3. Biosynthesis of γ-PGA

3.1. γ-PGA Racemization

3.2. γ-PGA Polymerization

3.3. γ-PGA Regulation

3.4. γ-PGA Degradation

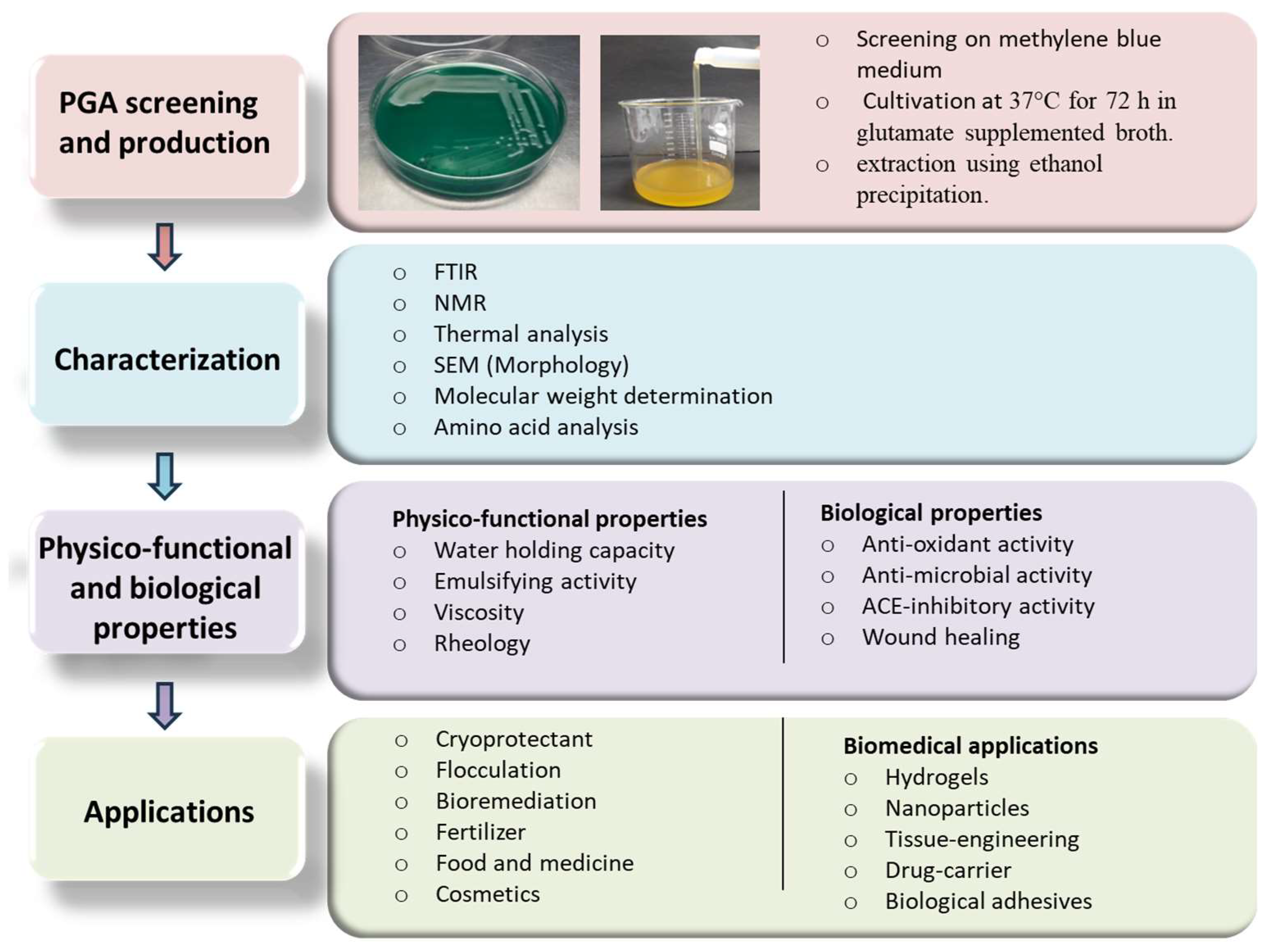

4. Production of γ-PGA

5. γ-PGA from Bacillus spp.

5.1. B. licheniformis

5.2. Bacillus subtilis

5.3. Bacillus anthracis

5.4. Bacillus thuringiensis

6. Structural and Physico-Chemical Properties of γ-PGA

6.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

6.2. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Analysis

6.3. Thermal Analysis

6.4. Molecular Weight Determination

6.5. Amino Acids and Enantiomeric Composition Analysis

7. Physico-Functional Properties

7.1. Water Holding Capacity

7.2. Emulsifying Property

7.3. Rheology and Viscosity

8. Biological Properties

8.1. Antioxidant Activity

8.2. Anti-Microbial Activity

8.3. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Activity

8.4. Wound Healing

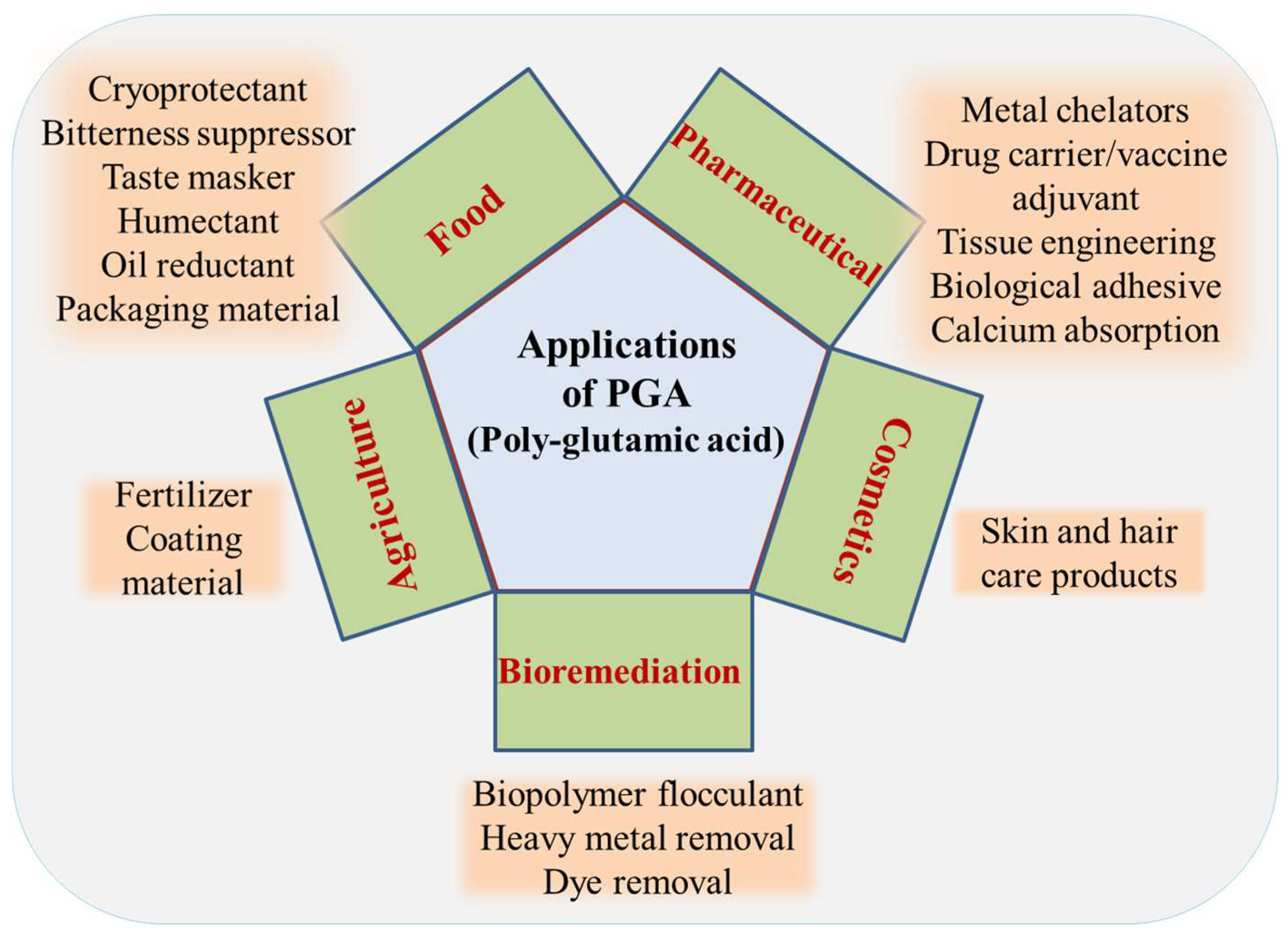

9. Applications of γ-PGA

9.1. Flocculation

9.2. Bioremediation

9.3. Fertilizer

9.4. Cryoprotectant

9.5. In Food and Medicine

9.6. Cosmetics

9.7. Biomedical Applications

9.7.1. Hydrogels

9.7.2. Nanoparticles

9.7.3. Tissue Engineering

9.7.4. Drug Carrier/Deliverer

9.7.5. Metal Chelators

9.7.6. Biological Adhesive

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Russo, T., Fucile, P., Giacometti, R., & Sannino, F. 2021. Sustainable removal of contaminants by biopolymers: a novel approach for wastewater treatment. Current state and future perspectives. Processes, 9(4), 719. [CrossRef]

- Jonnalagadda, S. S., Harnack, L., Hai, L. R., McKeown, N., Seal, C., Liu, S., et al. 2011. Putting the whole grain puzzle together: health benefits associated with whole grains-summary of American Society for Nutrition 2010 satellite symposium. Journal of Nutrition.141, 1011S-1022S. [CrossRef]

- Ajayeoba, T. A., Dula, S., & Ijabadeniyi, O. A. 2019. Properties of poly-γ-glutamic acid producing-Bacillus species isolated from ogi liquor and lemon-ogi liquor. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 771. [CrossRef]

- 4. Obst M, Steinbuchel A. 2004. Microbial degradation of poly (amino acid)s. Biomacromolecules. 5:1166–76. [CrossRef]

- Ivanovics, G., & Bruckner, V. 1937. The chemical nature of the immuno-specific capsule substance of anthrax bacillus. Naturwissenschaften, 25, 250.

- Bajaj, I., and Singhal, R. 2011. Poly (glutamic acid) an emerging biopolymer of commercial interest. Bioresource Technology 102, 5551-5561. [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, A., Bhat, A., Irorere, V. U., Hill, D., Williams, C., and Radecka, I. 2015. Poly-γ-glutamic acid: production, properties and applications. Microbiology 161, 1-17.

- Ashiuchi, M., Kamei, T., Baek, D. H., Shin, S. Y., Sung, M. H., Soda, K., et al. 2001. Isolation of Bacillus subtilis (chungkookjang), a poly-γ-glutamate producer with high genetic competence. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 57, 764–769.

- Yang, L. B., Zhan, X. B., Zhu, L., Gao, M. J., & Lin, C. C. 2016. Optimization of a low-cost hyperosmotic medium and establishing the fermentation kinetics of erythritol production by Yarrowia lipolytica from crude glycerol. Preparative Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 46(4), 376-383. [CrossRef]

- Hseu, Z., Guo, Y., Liu, J., Qiu, H., Zhao, M., Zou, W., & Li, S. 2016. Microbial synthesis of poly-γ-glutamic acid: current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 9(1), 1-12.

- Sung, M. H., Park, C., Kim, C. J., Poo, H., Soda, K., & Ashiuchi, M. 2005. Natural and edible biopolymer poly-γ-glutamic acid: synthesis, production, and applications. The Chemical Record, 5(6), 352-366.

- Najar, I. N., & Das, S. 2015. Poly-glutamic acid (PGA)-Structure, synthesis, genomic organization and its application: A Review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 6(6), 2258.

- Wang, L. L., Chen, J. T., Wang, L. F., Wu, S., Zhang, G. Z., Yu, H. Q., & Shi, Q. S. 2017. Conformations and molecular interactions of poly-γ-glutamic acid as a soluble microbial product in aqueous solutions. Scientific reports, 7(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, C. B., & Strey, H. H. 2008. Osmotically induced helix-coil transition in poly (glutamic acid). Biophysical Journal, 94(11), 4427-4434.

- Gooding, E. A., Sharma, S., Petty, S. A., Fouts, E. A., Palmer, C. J., Nolan, B. E., & Volk, M. 2013. pH-dependent helix folding dynamics of poly-glutamic acid. Chemical Physics. 422, 115-123.

- Jose, A. A., Anusree, G., Pandey, A., & Binod, P. 2018. Production optimization of poly-γ-glutamic acid by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens under solid-state fermentation using soy hull as substrate. Indian Journal of Biotechnology. vol 17(1).

- Oppermann-Sanio, F. B., and Steinbüchel, A. 2002. Occurrence, functions and biosynthesis of polyamides in microorganisms and biotechnological production. Naturwissenschaften 89, 11-22.

- Yao, J., Jing, J., Xu, H., Liang, J., Wu, Q., Feng, X., et al. 2009. Investigation on enzymatic degradation of γ-polyglutamic acid from Bacillus subtilis NX-2. Journa of Molecular Catalysis B 56, 158-164. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, L. P., Brito, P.N., and Alegre, R. M. 2013. The existing studies on biosynthesis of poly (γ-glutamic acid) by fermentation. Food Public Health 3, 28-36.

- Cachat, E., Barker, M., Read, T. D., and Priest, F. G. 2008. A Bacillus thuringiensis strain producing a polyglutamate capsule resembling that of Bacillus anthracis. Federation of European Microbiological Societies Microbiology Letter. 285, 220-226.

- Candela, T., Moya, M., Haustant, M., and Fouet, A. 2009. Fusobacterium nucleatum, the first gram-negative bacterium demonstrated to produce polyglutamate. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 55, 627-632. [CrossRef]

- Cao M., Geng W., Liu L., Song C., Xie H., Guo W., Jin Y., Wang S. 2011. Glutamic acid independent production of poly-γ-glutamic acid by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LL3 and cloning of pgsBCA genes. Bioresource Technology 102:4251–4257.

- Chettri, R., Bhutia, M. O., and Tamang, J. P. 2016. Poly-γ-glutamic acid (PGA)-producing Bacillus species isolated from Kinema, Indian fermented soybean food. Frontiers Microbioogy. 7:971.

- Kambourova, M., Tangney, M., and Priest, F. G. 2001. Regulation of polyglutamic acid synthesis by glutamate in Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 67,1004-1007. [CrossRef]

- Meerak, J., Yukphan, P., Miyashita, M., Sato, H., Nahagawa, Y., and Tahara, Y. 2008. Phylogeny of (γ-polyglutamic acid-producing Bacillus strains isolated from a fermented locust bean product. Journal of General and Applied Microbiology 54, 159-166.

- Tork, S. E., Aly, M. M., Alakilli, S. Y., and Al-Seeni, M. N. 2015. Purification and characterization of gamma poly glutamic acid from newly Bacillus licheniformis NRC20. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 74, 382-391. [CrossRef]

- Candela T., Fouet A. 2006. Poly-gamma-glutamate in bacteria. Molecular Microbiology 60:1091–1098.

- Buescher JM and Margaritis A. 2007. Microbial biosynthesis of polyglutamic acid biopolymer and applications in the biopharmaceutical, biomedical and food industries. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 27:1–19.

- Ko Y. H., Gross R. A. 1998. Effects of glucose and glycerol on γ-poly(glutamic acid) formation by Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 9945a. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 57:430–437.

- Rehm B. 2009. Microbial Production of Biopolymers and Polymer Precursors: Applications and Perspectives Caister: Horizon Scientific Press.

- Li, D., Hou, L., Gao, Y., Tian, Z., Fan, B., Wang, F., & Li, S. 2022. Recent advances in microbial synthesis of poly-γ-glutamic acid: a review. Foods, 11(5), 739.

- Wu Q, Xu H, Xu L, Ouyang P. 2006. Biosynthesis of poly (gamma-glutamic acid) in Bacillus subtilis NX-2: regulation of stereochemical composition of poly (gamma-glutamic acid). Process Biochemistry. 41:1650–5.

- Ashiuchi M. 2004. Enzymatic synthesis of high-molecular-mass poly-gamma-glutamate and regulation of its stereochemistry. Applied and Environmental Microbiology.70:4249–55.

- Candela T, Fouet A. 2005. Bacillus anthracis CapD, belonging to the gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase family, is required for the covalent anchoring of capsule to peptidoglycan. Molecular Microbiology. 57:717–26. [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro D, Yoshioka M, Ashiuchi M. 2011. Bacillus subtilispgsE (formerly ywtC) stimulates poly-γ-glutamate production in the presence of Zinc. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 108:226–30.

- Tran LSP, Nagai T, Itoh Y. 2000. Divergent structure of the ComQXPA quorum-sensing components: molecular basis of strain-specific communication mechanism in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular Microbiology.37:1159–71. [CrossRef]

- Do TH. 2011. Mutations suppressing the loss of DegQ function in Bacillus subtilis (natto) poly-γ-glutamate synthesis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology.77:8249–58.

- Ohsawa T, Tsukahara K, Ogura M. 2009. Bacillus subtilis response regulator DegU is a direct activator of pgsB transcription involved in gamma-poly-glutamic acid synthesis. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry.73:2096–102.

- Stanley NR, Lazazzera BA. 2005. Defining the genetic differences between wild and domestic strains of Bacillus subtilis that affect poly-gamma-dl-glutamic acid production and biofilm formation. Molecular Microbiology. l.57:1143–58.

- Kimura K, Tran LSP, Uchida I, Itoh Y. 2004. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis gamma-glutamyl transferase and its involvement in the degradation of capsule poly-gamma-glutamate. Microbiology.150:4115–23.

- King EC, Blacker AJ, Bugg TDH. 2000. Enzymatic breakdown of poly-gamma-D-glutamic acid in Bacillus licheniformis: identification of a polyglutamyl gamma-hydrolase enzyme. Biomacromolecules.1:75–83.

- Hsueh, Y. H., Huang, K. Y., Kunene, S. C., & Lee, T. Y. 2017. Poly-γ-glutamic acid synthesis, gene regulation, phylogenetic relationships, and role in fermentation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(12), 2644.

- Sanda, F., Fujiyama, T., & Endo, T. 2001. Chemical synthesis of poly-γ-glutamic acid by polycondensation of γ-glutamic acid dimer: synthesis and reaction of poly-γ-glutamic acid methyl ester. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry, 39(5), 732-741.

- Inatsu, Y., Nakamura, N., Yuriko, Y., Fushimi, T., Watanasiritum, L., & Kawamoto, S. 2006. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis strains in Thua nao, a traditional fermented soybean food in northern Thailand. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 43(3), 237-242. [CrossRef]

- Shih I. L., Van Y. T., Yeh L. C., Lin H. G., Chang Y. N. 2001. Production of a biopolymer flocculant from Bacillus licheniformis and its flocculation properties. Bioresource Technology. 78:267–272.

- Goto, A., and Kunioka, M. 1992. Biosynthesis and hydrolysis of poly (γ-glutamic acid) from Bacillus subtilis IFO3335. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 56, 1031-1035.

- Kunioka, M. (1995). Biosynthesis of poly (γ-glutamic acid) from l-glutamine, citric acid and ammonium sulfate in Bacillus subtilis IFO3335. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 44, 501-506.

- Cao M., Geng W., Zhang W., Sun J., Wang S., Feng J., Zheng P., Jiang A., Song C. 2013. Engineering of recombinant Escherichia coli cells co-expressing poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) synthetase and glutamate racemase for differential yielding of γ-PGA. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 6:675–684.

- Ashiuchi, M. 2013. Biochemical engineering of PGA. Microbial Biotechnology, 6(6), 664-674.

- Wei, X., Yang, L., Chen, Z., Xia, W., Chen, Y., Cao, M., & He, N. (2024). Molecular weight control of poly-γ-glutamic acid reveals novel insights into extracellular polymeric substance synthesis in Bacillus licheniformis. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts, 17(1), 60.

- Zeng, W., Liu, Y., Shu, L., Guo, Y., Wang, L., & Liang, Z. 2024. Production of ultra-high-molecular-weight poly-γ-glutamic acid by a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis strain and genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Biotechnology Journal, 19(4), 2300614. [CrossRef]

- Ashiuchi M., Kamei T., Baek D.H., Shin S.Y., Sung M.H., Soda K., Yagi T., Misono H. 2001. Isolation of Bacillus subtilis (chungkookjang), a poly-γ-glutamate producer with high genetic competence. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 57:764–769.

- Bhat A.R., Irorere V.U., Bartlett T., Hill D., Kedia G., Morris M.R., Charalampopoulos D., Radecka I. 2013. Bacillus subtilis natto: a non-toxic source of poly-γ-glutamic acid that could be used as a cryoprotectant for probiotic bacteria. AMB Express3:36. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q., Xu H., Ying H., Ouyang P. 2010. Kinetic analysis and pH-shift control strategy for poly (γ-glutamic acid) production with Bacillus subtilis CGMCC 0833. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 50:24–28.

- Cao M., Song C., Jin Y., Liu L., Liu J., Xie H., Guo W., Wang S. 2010. Synthesis of poly (γ-glutamic acid) and heterologous expression of pgsBCA genes. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic. 67:111–116.

- Birrer, G. A., Cromwick, A. M., & Gross, R. A. 1994. γ-Poly (glutamic acid) formation by Bacillus licheniformis 9945a: physiological and biochemical studies. International journal of biological macromolecules, 16(5), 265-275.

- Shih I. L., Wu P. J., Shieh C. J. 2005. Microbial production of a poly (γ-glutamic acid) derivative by Bacillus subtilis. Process Biochemistry. 40:2827–2832.

- Zhang H., Zhu J., Zhu X., Cai J., Zhang A., Hong Y., Huang J., Huang L., Xu Z. (2012). High-level exogenous glutamic acid-independent production of poly-(γ-glutamic acid) with organic acid addition in a new isolated Bacillus subtilis C10. Bioresource Technology. 116:241–246.

- Cromwick, A. M., Birrer, G. A., & Gross, R. A. 1996. Effects of pH and aeration on γ-poly (glutamic acid) formation by Bacillus licheniformis in controlled batch fermentor cultures. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 50(2), 222-227.

- Kubota, H., Matsunobu, T., Uotani, K., Takebe, H., Satoh, A., Tanaka, T., & Taniguchi, M. 1993. Production of poly (γ-glutamic acid) by Bacillus subtilis F-2-01. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry, 57(7), 1212-1213.

- Shih, L., & Van, Y. T. 2001. The production of poly-(γ-glutamic acid) from microorganisms and its various applications. Bioresource Technology, 79(3), 207-225.

- Yoon, W. K., Garcia, C. V., Kim, C. S., & Lee, S. P. 2018. Fortification of mucilage and GABA in Hovenia dulcis extract by co-fermentation with Bacillus subtilis HA and Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014. Food Science and Technology Research, 24(2), 265-271.

- Bajaj I. B., Lele S. S., Singhal R. S. 2008. Enhanced production of poly (γ-glutamic acid) from Bacillus licheniformis NCIM 2324 in solid state fermentation. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 35:1581–1586. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj I. B., Lele S. S., Singhal R. S. 2009. A statistical approach to optimization of fermentative production of poly (γ-glutamic acid) from Bacillus licheniformis NCIM 2324. Bioresource Technology 100:826–832. [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk M., Abou-Zeid D., Sabra W. 2012. Application of Plackett–Burman experimental design to evaluate nutritional requirements for poly (γ-glutamic acid) production in batch fermentation by Bacillus licheniformis A13. African Journal of Applied Microbiology Res. 2:6–18.

- Wang, N., Yang, G., Che, C., & Liu, Y. 2011. Heterogenous expression of poly-γ-glutamic acid synthetase complex gene of Bacillus licheniformis WBL-3. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology, 47, 381-385. [CrossRef]

- Ho, G. H., Ho, T. I., Hsieh, K. H., Su, Y. C., Lin, P. Y., Yang, J., & Yang, S. C. 2006. γ-Polyglutamic acid produced by Bacillus Subtilis (Natto): Structural characteristics, chemical properties and biological functionalities. Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society, 53(6), 1363-1384.

- Cheng, C., Asada, Y., & Aida, T. 1989. Production of γ-polyglutamic acid by Bacillus licheniformis A35 under denitrifying conditions. Agricultural and biological chemistry, 53(9), 2369-2375. [CrossRef]

- Bovarnick, M. 1942. The formation of extracellular d (-)-glutamic acid polypeptide by Bacillus subtilis. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 145(2), 415-424. [CrossRef]

- Scoffone, V., Dondi, D., Biino, G., Borghese, G., Pasini, D., Galizzi, A., & Calvio, C. 2013. Knockout of pgdS and ggt genes improves γ-PGA yield in B. subtilis. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 110(7), 2006-2012.

- Shi, F., Xu, Z., & Cen, P. 2006. Efficient production of poly-γ-glutamic acid by Bacillus subtilis ZJU-7. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 133, 271-281.

- Ogawa, Y., Yamaguchi, F., Yuasa, K., & Tahara, Y. 1997. Efficient production of γ-polyglutamic acid by Bacillus subtilis (natto) in jar fermenters. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry, 61(10), 1684-1687.

- Zwartouw H.T., Smith H. 1956. Polyglutamic acid from Bacillus anthracis grown in vivo: structure and aggression activity. Biochemical Journal. 63:437–442.

- Ezzell J. W., Abshire T. G., Panchal R., Chabot D., Bavari S., Leffel E. K., Purcell B., Friedlander A. M., Ribot W. J. 2009. Association of Bacillus anthracis capsule with lethal toxin during experimental infection. Infection and Immunity. 77:749–755. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Zhong, C., & Wu, D. 2021. Study on the reuse process of hydrolysate from γ-polyglutamic acid fermentation residues. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 14(5), 103145.

- Mohanraj, R., Gnanamangai, B. M., Ramesh, K., Priya, P., Srisunmathi, R., Poornima, S., & Robinson, J. P. 2019. Optimized production of gamma poly glutamic acid (γ-PGA) using sago. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 22, 101413. [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj BS, Chen B-H 2012. In vitro removal of toxic heavy metals by poly (γ-glutamic acid)-coated superparamagnetic nanoparticles. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 7:4419.

- Lee, J. M., Kim, J. H., Kim, K. W., Lee, B. J., Kim, D. G., Kim, Y. O., & Kong, I. S. 2018. Physicochemical properties, production, and biological functionality of poly-γ-D-glutamic acid with constant molecular weight from halotolerant Bacillus sp. SJ-10. International journal of biological macromolecules, 108, 598-607.

- Gentilini, C., Dong, Y., May, J. R., Goldoni, S., Clarke, D. E., Lee, B. H., & Stevens, M. M. (2012). Functionalized Poly (γ-Glutamic Acid) Fibrous Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Advanced healthcare materials, 1(3), 308-315.

- Kunioka, M. 1995. Biosynthesis of poly (γ-glutamic acid) from l-glutamine, citric acid and ammonium sulfate in Bacillus subtilis IFO3335. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 44, 501-506.

- Bajestani, M. I., Mousavi, S. M., Mousavi, S. B., Jafari, A., & Shojaosadati, S. A. 2018. Purification of extra cellular poly-γ-glutamic acid as an antibacterial agent using anion exchange chromatography. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 113, 142-149. [CrossRef]

- Shyu, Y. S., & Sung, W. C. 2010. Improving the emulsion stability of sponge cake by the addition of γ-polyglutamic acid. Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 18(6), 14.

- Johnson, L. C., Akinmola, A. T., & Scholz, C. 2022. Poly (glutamic acid): From natto to drug delivery systems. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 40, 102292.

- Shi, W., Liang, J., Tao, W., Tan, S., & Wang, Q. 2015. γ-PGA additive decreasing soil water infiltration and improving water holding capacity. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 31(23), 94-100.

- Lim S., Kim J., Shim J., Imm B., Sung M., Imm J. 2012. Effect of poly-γ-glutamic acids (PGA) on oil uptake and sensory quality in doughnuts. Food Science and Biotechnology. 21:247–252.

- Lee, N., Go, T., Lee, S., Jeong, S., Park, G., Hong, C., et al. 2014. In vitro evaluation of new functional properties of poly-γ-glutamic acid produced by Bacillus subtilis D7. Saudi Journal of. Biological Sciences. 21, 153–158. [CrossRef]

- Mundo, J. L. M., Zhou, H., Tan, Y., Liu, J., & Mc Clements, D. J. 2020. Stabilization of soybean oil-in-water emulsions using polypeptide multilayers: Cationic polylysine and anionic polyglutamic acid. Food Research International, 137, 109304. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Zhang, S., Jiang, G., Gan, L., Xu, Z., & Tian, Y. 2022. Optimization of fermentation conditions, purification and rheological properties of poly (γ-glutamic acid) produced by Bacillus subtilis 1006-3. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 52(3), 302-310.

- de Cesaro, A., da Silva, S. B., da Silva, V. Z., & Ayub, M. A. Z. 2014. Physico-chemical and rheological characterization of poly-gamma-glutamic acid produced by a new strain of Bacillus subtilis. European polymer journal, 57, 91-98.

- Wang, R., Zhou, B., Xu, D. L., Xu, H., Liang, L., Feng, X. H., & Chi, B. 2016. Antimicrobial and biocompatible ε-polylysine–γ-poly (glutamic acid)–based hydrogel system for wound healing. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers, 31(3), 242-259.

- Pihlanto, A., Akkanen, S., & Korhonen, H. J. 2008. ACE-inhibitory and antioxidant properties of potato (Solanum tuberosum). Food Chemistry, 109(1), 104-112. [CrossRef]

- Tsao C. T., Chang C. H., Lin Y. Y., Wu M. F., Wang J. L., Young T. H., Han J. L., Hsieh K. H. 2011. Evaluation of chitosan/γ-poly (glutamic acid) polyelectrolyte complex for wound dressing materials. Carbohydrate Polymers. 84:812–819.

- Ye, H., Xian, Y., Li, S., Zhang, C., & Wu, D. 2022. In situ forming injectable γ-poly (glutamic acid)/PEG adhesive hydrogels for hemorrhage control. Biomaterials Science, 10(15), 4218-4227.

- Deng S, Bai R, Hu X, Luo Q 2003. Characteristics of a bioflocculant produced by Bacillus mucilaginosus and its use in starch wastewater treatment. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 60:588–593. [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Zhang Y, Wei X, Hu Z, Zhu F, Xu L, Luo M, Liu H 2013. Production of ultra-high molecular weight poly-γ-glutamic acid with Bacillus licheniformis P-104 and characterization of its flocculation properties. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 170:562–572. [CrossRef]

- Kinnersley, A., Strom, D., Meah, R.Y., and Koskan, C.P. 1994. Composition and method for enhanced fertilizer uptake by plants (WO patent no. 94/09,628).

- Inbaraj B. S., Chiu C. P., Ho G. H., Yang J., Chen B. H. 2006. Removal of cationic dyes from aqueous solution using an anionic poly-γ-glutamic acid-based adsorbent. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 137:226–234.

- Campos, V., Fernandes, A. R., Medeiros, T. A., & Andrade, E. L. 2016. Physicochemical characterization and evaluation of PGA bioflocculant in coagulation-flocculation and sedimentation processes. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 4(4), 3753-3760.

- Zheng H, Gao Z, Yin J, Tang X, Ji X, Huang H 2012. Harvesting of microalgae by flocculation with poly(γ-glutamic acid). Bioresource Technology 112:212–220. [CrossRef]

- Sheu, Y. T., Tsang, D. C., Dong, C. D., Chen, C. W., Luo, S. G., & Kao, C. M. 2018. Enhanced bioremediation of TCE-contaminated groundwater using gamma poly-glutamic acid as the primary substrate. Journal of Cleaner Production, 178, 108-118. [CrossRef]

- Hajdu I., Bodnár M., Csikós Z., Wei S., Daróczi L., Kovács B., Győri Z., Tamás J., Borbély J. 2012. Combined nano-membrane technology for removal of lead ions. Journal of Membrane Science. 409–410:44–53.

- Xu Z, Wan C, Xu X, Feng X, Xu H. 2013. Effect of poly (γ-glutamic acid) on wheat productivity, nitrogen use efficiency and soil microbes. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 13:744–755.

- Wang, F., Chen, Y., Zheng, J., Yang, C., Li, L., Li, R., & Li, Z. 2024. Preparation of potential organic fertilizer rich in γ-polyglutamic acid via microbial fermentation using brewer's spent grain as basic substrate. Bioresource Technology, 394, 130216.

- Wang Q., Chen S., Zhang J., Sun M., Liu Z., Yu Z. 2008. Co-producing lipopeptides and poly-γ-glutamic acid by solid-state fermentation of Bacillus subtilis using soybean and sweet potato residues and its biocontrol and fertilizer synergistic effects. Bioresource Technology. 99:3318–3323.

- Shih I. L., Van Y. T., Sau Y. Y. 2003. Antifreeze activities of poly (γ-glutamic acid) produced by Bacillus licheniformis. Biotechnology Letters. 25:1709–1712.

- Bhat A, Irorere V, Bartlett T, Hill D, Kedia G, Charalampopoulos D, Nualkaekul S, Radecka 2015. Improving survival of probiotic bacteria using bacterial poly-γ-glutamic acid. International Journal of Food Microbiology 196:24–31.

- Tanimoto H., Fox T., Eagles J., Satoh H., Nozawa H., Okiyama A., Morinaga Y., Fairweather-Tait S. J. 2007. Acute effect of poly-γ-glutamic acid on calcium absorption in post-menopausal women. Journal of the American College of the Nutrition. 26:645–649.

- Kishimoto N, Morishima H, Uotani K. 2008. Compositions for prevention of increase of blood pressure Japanese patent application. Publication (2008-255063).

- Tamura, M., Watanabe, J., Hori, S., Inose, A., Kubo, Y., Noguchi, T., & Kobori, M. 2021. Effects of a high-γ-polyglutamic acid-containing natto diet on liver lipids and cecal microbiota of adult female mice. Bioscience of Microbiota, Food and Health, 2020-061. [CrossRef]

- Siaterlis A., Deepika G., Charalampopoulos D. 2009. Effect of culture medium and cryoprotectants on the growth and survival of probiotic lactobacilli during freeze drying. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 48:295–301.

- Jagannath A., Raju P. S., Bawa A. S. 2010. Comparative evaluation of bacterial cellulose (nata) as a cryoprotectant and carrier support during the freeze drying process of probiotic lactic acid bacteria. LWT – Food Science and Technology. 43:1197–1203.

- Ben-Zur N., Goldman D. M. 2007. γ-Polyglutamic acid: a novel peptide for skin care. Cosmetics Toiletries. 122:65–74.

- Abd Alsaheb, R. A., Othman, N. Z., Abd Malek, R., Leng, O. M., Aziz, R., & El Enshasy, H. A. 2016. Polyglutamic acid applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical industries. Der Pharmacia Letter, 8(9), 217-225.

- Murakami S, Aoki N, Matsumura S 2011. Bio-based biodegradable hydrogels prepared by cross-linking of microbial poly (γ-glutamic acid) with l-lysine in aqueous solution. Polymer Journal. 43:414–420.

- Lin W-C, Yu D-G, Yang M-C 2006. Blood compatibility of novel poly (γ-glutamic acid)/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 47:43–49.

- Yu, K., & Aubin-Tam, M. E. (2020). Bacterially grown cellulose/graphene oxide composites infused with γ-Poly (glutamic acid) as biodegradable structural materials with enhanced toughness. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 3(12), 12055-12063. [CrossRef]

- Tao, L., Long, H., Zhang, J., Qi, L., Zhang, S., Li, T., & Li, S. 2021. Preparation and coating application of γ-polyglutamic acid hydrogel to improve storage life and quality of shiitake mushrooms. Food Control, 130, 108404.

- Lin Y-H, Chung C-K, Chen C-T, Liang H-F, Chen S-C, Sung H-W 2005. Preparation of nanoparticles composed of chitosan/poly-γ-glutamic acid and evaluation of their permeability through Caco-2 cells. Biomacromolecules 6:1104–1112. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay P, Mishra R, Rana D, Kundu PP 2012. Strategies for effective oral insulin delivery with modified chitosan nanoparticles: a review. Progress in Polymer Science. 37:1457–1475.

- Hsieh C.-Y., Tsai S.-P., Wang D.M., Chang Y.N., Hsieh H.J. 2005. Preparation of γ-PGA/chitosan composite tissue engineering matrices. Biomaterials. 26:5617–5623. [CrossRef]

- Ye H., Jin L., Hu R., Yi Z., Li J., Wu Y., Xi X., Wu Z. 2006. Poly (γ,l-glutamic acid)–cisplatin conjugate effectively inhibits human breast tumor xenografted in nude mice. Biomaterials. 27:5958–5965.

- Singer J. W. 2005. Paclitaxel poliglumex (XYOTAX, CT-2103): a macromolecular taxane. J Control Release109:120–126.

- Otani Y., Tabata Y., Ikada Y. 1999. Sealing effect of rapidly curable gelatin-poly (l-glutamic acid) hydrogel glue on lung air leak. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 67:922–926.

- Shih, I. L., Van, Y. T., & Shen, M. H. 2004. Biomedical applications of chemically and microbiologically synthesized poly (glutamic acid) and poly (lysine). Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry, 4(2), 179-188.

- Yu, X., Wang, M., Wang, Q. H., & Wang, X. M. 2011. Biosynthesis of polyglutamic acid and its application on agriculture. Advanced materials research, 183, 1219-1223. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Y., & Ye, H. F. 2007. Characterization and flocculating properties of an extracellular biopolymer produced from a Bacillus subtilis DYU1 isolate. Process Biochemistry, 42(7), 1114-1123.

- Zhang, C., Ren, H. X., Zhong, C. Q., & Wu, D. 2020. Biosorption of Cr (VI) by immobilized waste biomass from polyglutamic acid production. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 3705.

- Liu, J., Ma, X., Wang, Y., Liu, F., Qiao, J., Li, X. Z., & Zhou, T. 2011. Depressed biofilm production in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens C06 causes γ-polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA) overproduction. Current microbiology, 62, 235-241. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Wu, D., & Ren, H. 2019. Economical production of agricultural γ-polyglutamic acid using industrial wastes by Bacillus subtilis. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 146, 117-123.

- Pereira, A. E. S., Sandoval-Herrera, I. E., Zavala-Betancourt, S. A., Oliveira, H. C., Ledezma-Pérez, A. S., Romero, J., & Fraceto, L. F. 2017. γ-Polyglutamic acid/chitosan nanoparticles for the plant growth regulator gibberellic acid: Characterization and evaluation of biological activity. Carbohydrate polymers, 157, 1862-1873.

- Richard, A., & Margaritis, A. 2001. Poly (glutamic acid) for biomedical applications. Critical reviews in biotechnology, 21(4), 219-232.

- Yang, Z. H., Dong, C. D., Chen, C. W., Sheu, Y. T., & Kao, C. M. 2018. Using poly-glutamic acid as soil-washing agent to remediate heavy metal-contaminated soils. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 5231-5242.

- Xu, J., Krietemeyer, E. F., Finkenstadt, V. L., Solaiman, D., Ashby, R. D., & Garcia, R. A. 2016. Preparation of starch–poly–glutamic acid graft copolymers by microwave irradiation and the characterization of their properties. Carbohydrate Polymers, 140, 233-237.

- Zhang, S. F., Gao, C., Lü, S., He, J., Liu, M., Wu, C., & Liu, Z. 2017. Synthesis of PEGylated polyglutamic acid peptide dendrimer and its application in dissolving thrombus. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 159, 284-292.

- Tao, L., Tian, L., Zhang, X., Huang, X., Long, H., Chang, F., & Li, S. 2020. Effects of γ-polyglutamic acid on the physicochemical properties and microstructure of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) surimi during frozen storage. Lwt, 134, 109960.

- Shi, F., Xu, Z., & Cen, P. 2006. Optimization of γ-polyglutamic acid production by Bacillus subtilis ZJU-7 using a surface-response methodology. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering, 11, 251-257.

- Konglom, N., Chuensangjun, C., Pechyen, C., & Sirisansaneeyakul, S. 2012. Production of poly- γ-glutamic acid by Bacillus licheniformis: Synthesis and characterization. Journal of Metals, Materials and Minerals, 22(2), 7-11.

- Chatterjee, P. M., Datta, S., Tiwari, D. P., Raval, R., & Dubey, A. K. 2018. Selection of an effective indicator for rapid detection of microorganisms producing γ-polyglutamic acid and its biosynthesis under submerged fermentation conditions using Bacillus methylotrophicus. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology, 185, 270-288.

- Hezayen, F. F., Rehm, B. H., Tindall, B. J., & Steinbüchel, A. 2001. Transfer of Natrialba asiatica B1T to Natrialba taiwanensis sp. nov. and description of Natrialba aegyptiaca sp. nov., a novel extremely halophilic, aerobic, non-pigmented member of the Archaea from Egypt that produces extracellular poly (glutamic acid). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 51(3), 1133-1142.

- Qi, H., Na, R., Xin, J., Xie, Y. J., & Guo, J. F. 2013. Effect of corona electric field on the production of gamma-poly glutamic acid based on Bacillus natto. Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 418, No. 1, p. 012139).

- Du, G., Yang, G., Qu, Y., Chen, J., & Lun, S. 2005. Effects of glycerol on the production of poly (γ-glutamic acid) by Bacillus licheniformis. Process Biochemistry, 40(6), 2143-2147.

- Zhang, H., Zhu, J., Zhu, X., Cai, J., Zhang, A., Hong, Y., & Xu, Z. 2012. High-level exogenous glutamic acid-independent production of poly-(γ-glutamic acid) with organic acid addition in a new isolated Bacillus subtilis C10. Bioresource Technology, 116, 241-246.

- Min, J. H., Reddy, L. V., Dimitris, C., Kim, Y. M., & Wee, Y. J. 2019. Optimized production of poly (γ-glutamic acid) by Bacillus sp. FBL-2 through response surface methodology using central composite design.

- Ward, R. M., Anderson, R. F., & Dean, F. K. 1963. Polyglutamic acid production by Bacillus subtilis NRRL B-2612 grown on wheat gluten. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 5(1), 41-48.

- Kreyenschulte, D., Krull, R., & Margaritis, A. 2014. Recent advances in microbial biopolymer production and purification. Critical reviews in biotechnology, 34(1), 1-15.

- Giannos, S. A., Shah, D., Gross, R. A., Kaplan, D. L., & Mayer, J. M. 1990. Poly (glutamic acid) produced by bacterial fermentation. In Novel biodegradable microbial polymers (pp. 457-460). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Mahaboob Ali, A. A., Momin, B., & Ghogare, P. 2020. Isolation of a novel poly-γ-glutamic acid-producing Bacillus licheniformis A14 strain and optimization of fermentation conditions for high-level production. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 50(5), 445-452.

- Manocha, B., & Margaritis, A. 2010. Controlled Release of Doxorubicin from Doxorubicin/γ-Polyglutamic Acid Ionic Complex. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2010(1), 780171.

- Yazdanparast, S., Benvidi, A., Banaei, M., Nikukar, H., Tezerjani, M. D., & Azimzadeh, M. 2018. Dual-aptamer based electrochemical sandwich biosensor for MCF-7 human breast cancer cells using silver nanoparticle labels and a poly (glutamic acid)/MWNT nanocomposite. Microchimica Acta, 185, 1-10.

- Oliveri, V., Bellia, F., Viale, M., Maric, I., & Vecchio, G. 2017. Linear polymers of β and γ cyclodextrins with a polyglutamic acid backbone as carriers for doxorubicin. Carbohydrate polymers, 177, 355-360.

- Ko, W. C., Chang, C. K., Wang, H. J., Wang, S. J., & Hsieh, C. W. 2015. Process optimization of microencapsulation of curcumin in γ-polyglutamic acid using response surface methodology. Food chemistry, 172, 497-503.

- Li, M., Zhu, X., Yang, H., Xie, X., Zhu, Y., Xu, G., & Li, A. 2020. Treatment of potato starch wastewater by dual natural flocculants of chitosan and poly-glutamic acid. Journal of Cleaner Production, 264, 121641.

- Santos, D. P., Bergamini, M. F., & Zanoni, M. V. B. 2008. Voltammetric sensor for amoxicillin determination in human urine using polyglutamic acid/glutaraldehyde film. Sensors and actuators B: Chemical, 133(2), 398-403.

- Garcia, J. P. D., Hsieh, M. F., Doma Jr, B. T., Peruelo, D. C., Chen, I. H., & Lee, H. M. 2013. Synthesis of gelatin-γ-polyglutamic acid-based hydrogel for the in vitro controlled release of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) from Camellia sinensis. Polymers, 6(1), 39-58.

- Rethore, G., Mathew, A., Naik, H., & Pandit, A. 2009. Preparation of chitosan/polyglutamic acid spheres based on the use of polystyrene template as a nonviral gene carrier. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods, 15(4), 605-613.

| Sl. NO | NAME OF BACTERIA | LAB | SOURCES | PROPERTIES | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bacillus licheniformis NCIM 2324 | No | NCIM | Molecular weight determination, amino acid analysis, total sugar content | Bajaj et al. [64] |

| 2 | B. licheniformis & B. subtilis | No | Chunkookjang | Chemical and microbial synthesis, application of PGA in medicine as drug carrier & biological adhesives | Shih et al. (2004) [125] |

| 3 | B. licheniformis CCRC 12826 | No | CCRC, Taiwan | Production of biodegradable & harmless PGA | Shih et al. (2001) [45] |

| 4 | B. subtilis | No | natto | Factors affecting production and agricultural applications | Yu et al. (2011) [126] |

| 5 | B. subtilis DYU1 | No | Soil samples from a soy sauce manufacturing site | Flocculating activity and harmlessness to humans and environment | Wu & Ye (2007) [127] |

| 6 | B. subtilis | No | Soil sample of electroplating industry | Biodegradability, film-forming property, fibrogenicity, water-holding capacity | Zhang et al. (2020) [128] |

| 7 | B. amyloliquefaciens C06 | No | Post-harvest fruit | Optimization of fermentation conditions to regulate stereochemical composition of γ-PGA & enhanced productivity of γ-PGA | Liu et al. (2011) [129] |

| 8 | B. subtilis ZC-5 | No | CICC, China | Solid-state fermentation, low cost substrates, environmental friendly process, reduced energy requirement & waste-water production | Zhang et al. (2019) [130] |

| 9 | B. licheniformis | No | Applied Chemistry Research Center (Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico) | Characterization of nanoparticles, encapsulation assays, bioactivity assays, in vitro release assays | Pereira et al. (2017) [131] |

| 10 | B. subtilis & B. licheniformis | No | reviewing different sources | Biopolymer Rheology & Viscosity-molecular weight correlation | Richard & Margaritis (2001) [132] |

| 11 | B. subtilis | No | Analysis of heavy metal distribution in soil | Yang et al. (2018) [133] | |

| 12 | B. licheniformis ATCC 9945a | No | ATCC | Water absorption & solubility, graft content & efficiency, rheological behaviour | Xu et al. (2016) [134] |

| 13 | B. subtilis | No | Nattokinase | High safety, simple production process, drug delivery system, excellent water solubility, biocompatibility, biodegradability | Zhang et al. (2017) [135] |

| 14 | B. subtilis | no | natto | cryoprotective effects of γ-PGA, Determination of dynamic rheological properties, Ca2+-ATPase activity, gel strength, salt-soluble protein content | Tao et al. (2020) [136] |

| 15 | B. subtilis ZJU-17 | no | fermented bean curd | effects of carbon sources and influence of nitrogen source on gamma polyglutamic acid production | Shi et al. (2006) [137] |

| 16 | B. licheniformis 9945 | no | ATCC | Production and purification and molecular size estimation | Kongklom et al. (2012) [138] |

| 17 | B. methylotrophicus, B. subtilis and B. licheniformis | no | Natto & rhizosphere of pepper, cabbage, sweet corn, fenugreek leaves, barley, tomato, and sugarcane plants | Use of methylene blue to differentiate the monomeric and the polymeric forms of glutamic acid | Chatterjee et al. (2018) [139] |

| 18 | Natrialba aegyptiaca & N. asiatica | no | beach sand (Egypt) | Analysis of the extracellular polymer | Hezayen et al. (2001) [140] |

| 19 | Bacillus natto 20646 | no | Natto | PCR Analysis | Qi et al. (2013) [141] |

| 20 | Bacillus sp. SJ-10 | no | Chungkookjang | physicochemical properties and biofunctionality of PGA, Molecular weight determination | Lee et al. (2018) [78] |

| 21 | B. licheniformis WBL-3 (mutant of 9945) | no | ATCC | Effect of glycerol on cell growth and g-PGA production | Du et al. (2005) [142] |

| 22 | B. subtilis | no | Natto | Culture conditions, PGA Analysis | Ogawa et al. (1997) [72] |

| 23 | B. subtilis C10 | no | Sauce (from local supermarket, China) | Isolation and characterisation of exogenous glutamic acid-independent strain | Zhang et al. (2012) [143] |

| 24 | Bacillus spp. FBL-2. | no | Cheonggukjang | Optimization of medium components by central composite design (CCD) | Min et al. (2019) [144] |

| 25 | B. amyloliquefaciens C06 | no | Mesophilic cheese starter | Molecular weight determination, UV scanning and amino acid analysis with paper chromatography | Liu et al. (2011) [129] |

| 26 | B. licheniformis A13 | no | Isolated from a tannery effluent | optimization of PGA production | Mabrouk et al. (2012) [65] |

| 27 | B. licheniformis A35 | no | Natto | Determination of amino acid | Cheng et al. (1989) [67] |

| 28 | B. licheniformis NRC20 | no | Mine soil | Viscosity measurement, Molecular weight determination, Amino acid analysis | Tork et al. (2015) [26] |

| 29 | B. subtilis | no | Natto | Application of γ-polyglutamic acid (Na+ form) in skin care products | Ho et al. (2006) [76] |

| 30 | B. licheniformis and B. subtilis | no | Natto | biofilm formation, biosynthesis of PGA, genes involed, applications | Najar & Das (2015) [12] |

| 31 | B. subtilis NRRL B-2612 | no | devitalized wheat gluten | Solubility in water, molecular weight determination,viscocity | Ward et al. (1963) [145] |

| 32 | B. licheniformis 9945a (NCIM 2324), B. subtilis ZJU-7 | no | Reviewing many sources | Molecular mass determination, Amino acid analysis, biodegradability, edibility and mmunogenicity | Ogunleye, et al. (2015) [7] |

| 33 | B. subtilis | no | Natto | Rheology of biopolymers | Kreyenschulte et al. (2014) [146] |

| 34 | B. licheniformis | no | ATCC | production optimization | Giannos et al. (1990) [147] |

| 35 | B. licheniformis NBRC12107 | no | Fermented locust bean products | Characterization, Tensile strength and porosity | Yu & Aubin (2020) [116] |

| 36 | B. licheniformis A14 | no | Marine sands | Microbially derived biopolymers are renewable in nature | Ali et al. (2020) [148] |

| 37 | B. subtilis (CGMCC17326) | no | Natto | Film forming property, Reduced degree of browning in shiitake mushrooms | Tao et al. (2021) [117] |

| 38 | B. subtilis W-17 CICC 10260 | no | CICC | Use of γ-polyglutamic acid waste biomass | Zhang et al. (2021) [75] |

| SL NO | PGA | SOURCE | PROPERTIES | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Commercial PGA | Natto Biosciences (Montreal, Canada) | hydrophilicity, biodegradability, biocompatibility, immunogenicity and ionic nature | Manocha & Margaritis (2010) [149] |

| 2 | Commercial PGA | Sigma Aldrich | Detection of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells & MUC1 biomarker | Yazdanparast et al. (2018) [150] |

| 3 | Commercial PGA | VEDAN Co. (Taichung, Taiwan) | Polyelectrolyte complex formation | Tsao et al. (2011) [92] |

| 4 | Commercial PGA | IRIS Biotech gmbh (CAS No 26247-79-0) | Protective agent of protein aggregation, drug delivery, low physical stability | Oliveri et al. (2017) [151] |

| 5 | Commercial PGA | VEDAN Co. (Taichung, Taiwan) | Water-soluble properties, anti-cancer & antioxidant activties, increase biocompatible & biodegradable abilities, encapsulation efficiency | Ko et al. (2015) [152] |

| 6 | Commercial PGA | Bioshinking Company (Nanjing, China | Biodegradability, physico-chemical characterization & evaluation of PGA bioflocculant in coagulation flocculation & sedimentation processes | Li et al. (2020) [153] |

| 7 | Commercial PGA | Sigma Aldrich | Antibacterial activity, low solubility in organic solvents, high positive potential, low sentivity | Santos et al. (2020) [154] |

| 8 | Commercial PGA | VEDAN Co. (Taichung, Taiwan) | Determination of Swelling Degree | Garcia et al. (2013) [155] |

| 9 | Commercial PGA | New England BioLabs, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom | Biodegradable polymer, increased rigidity, porosity & availailibity, rate of degradation | Rethore et al. (2009) [156] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).