Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

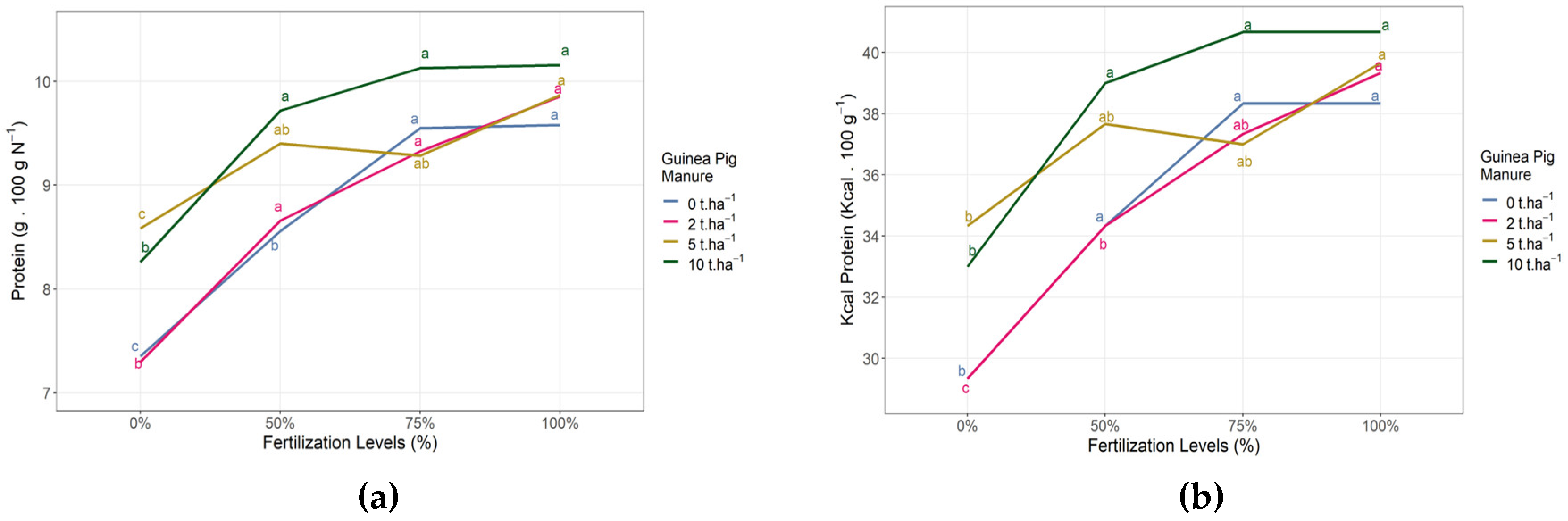

Sustainable fertilization using local resources like manure is crucial for soil health. This study evaluated the potential of guinea pig manure to replace mineral fertilizers in hard yellow maize (hybrid INIA 619) under Peruvian coastal conditions. A split-plot design tested four doses of guinea pig manure (0, 2, 5, 10 t⋅ha⁻¹) and four levels of mineral fertilization (0%, 50%, 75%, 100%). The study assessed plant height, ear characteristics, yield, and nutritional quality parameters. The results indicated that 100% mineral fertilization led to the highest plant height (229.67 cm) and grain weight (141.8 g). Yields of 9.19 and 9.08 t⋅ha⁻¹ were achieved with 5 and 10 t⋅ha⁻¹ of manure, while 50% mineral fertilization gave 8.8 t⋅ha⁻¹, similar to the full dose (8.7 t⋅ha⁻¹). Protein content was highest with 10 t⋅ha⁻¹ of manure combined with mineral fertilization. However, no significant differences were found between the 50%, 75%, and 100% mineral fertilizer doses. In conclusion, applying guinea pig manure improved nutrient use efficiency, yield, and grain protein quality in maize, reducing the need for mineral fertilizers by up to 50%. This provides a sustainable fertilization strategy for agricultural systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

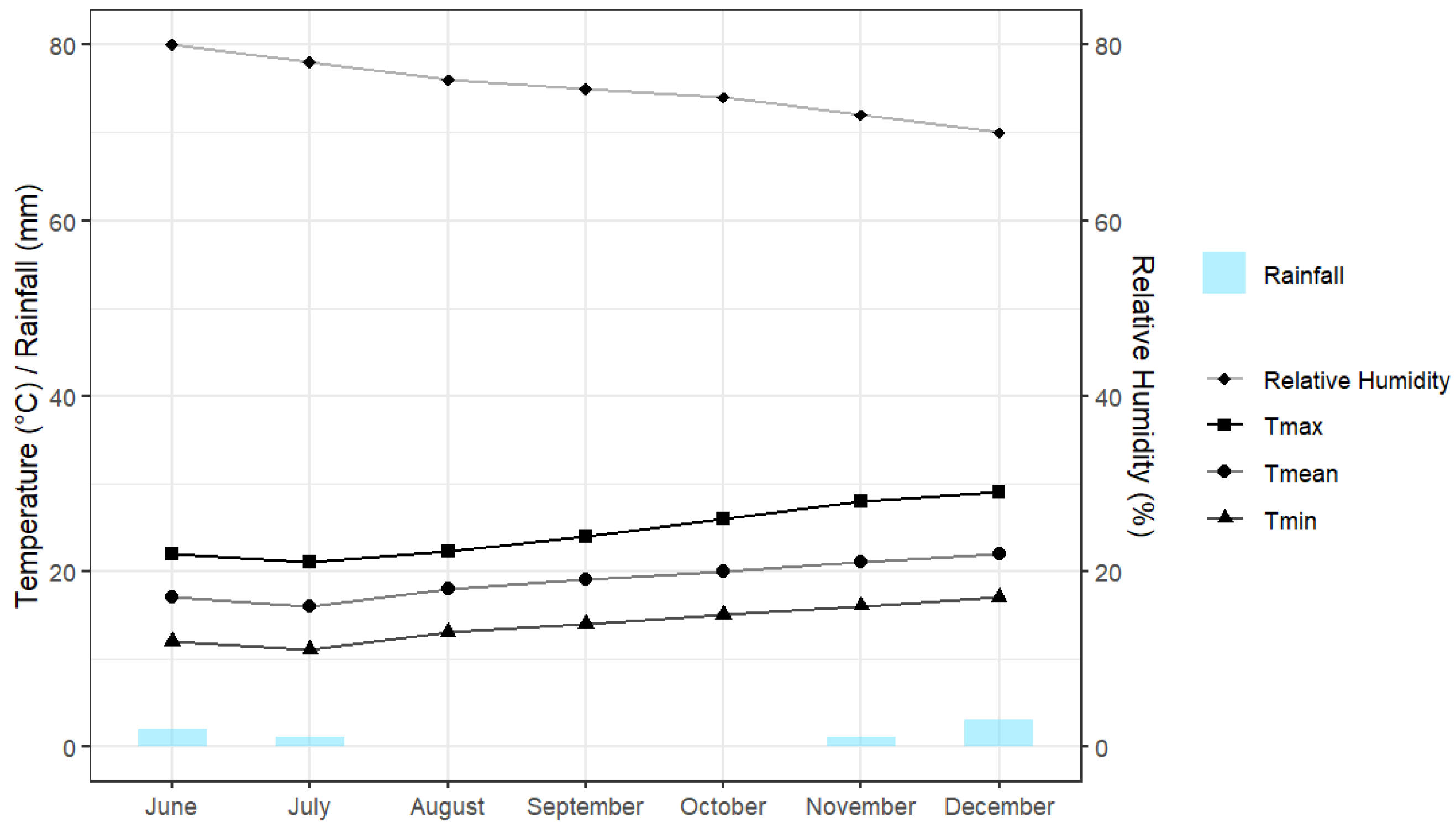

2.1. Trial Location

2.2. Soil Characteristics

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Description of the Organic Matter

2.5. Crop Fertilization

2.6. Agronomic Management

2.7. Evaluated Parameters

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

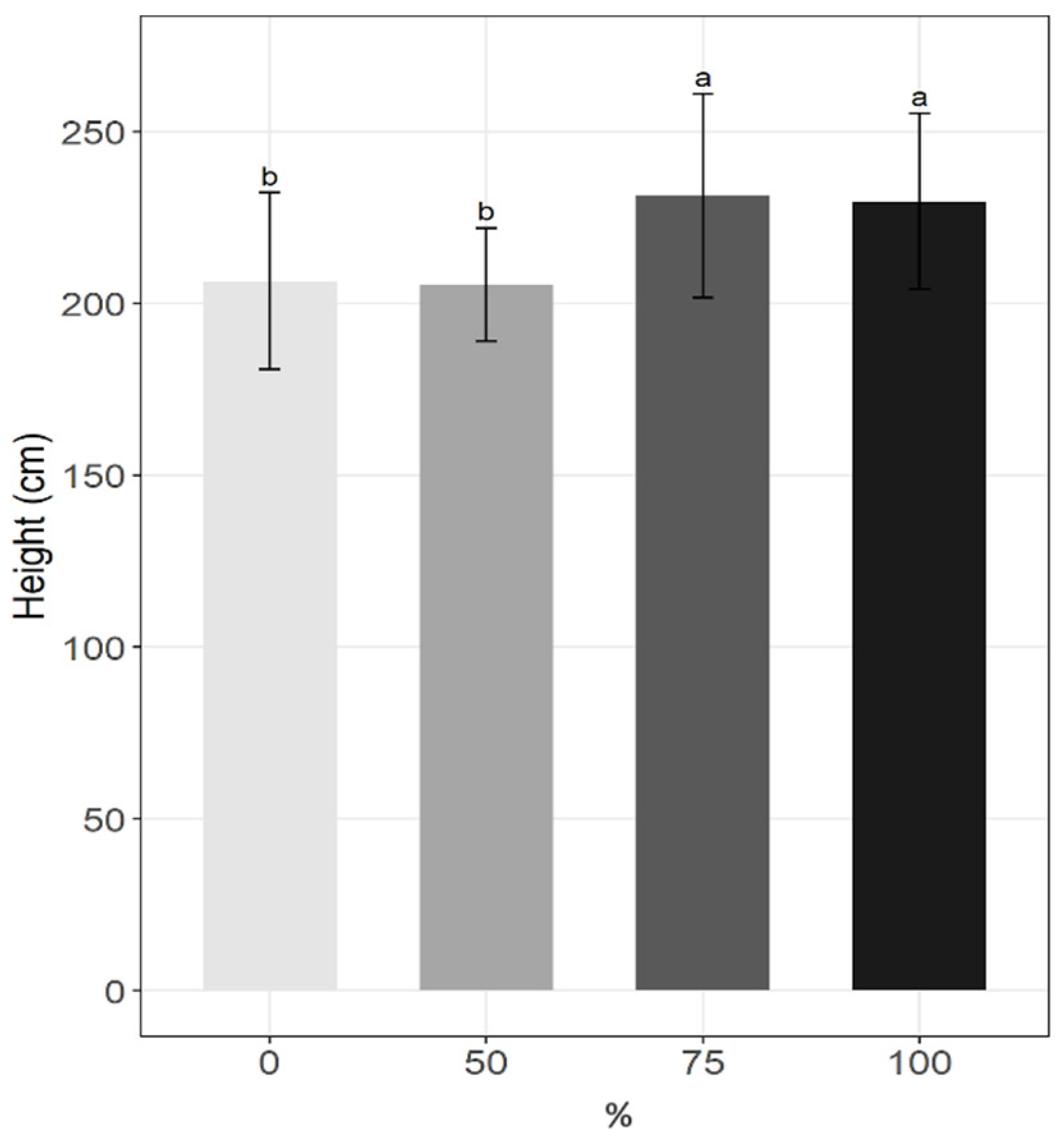

3.1. Vegetative Characteristics

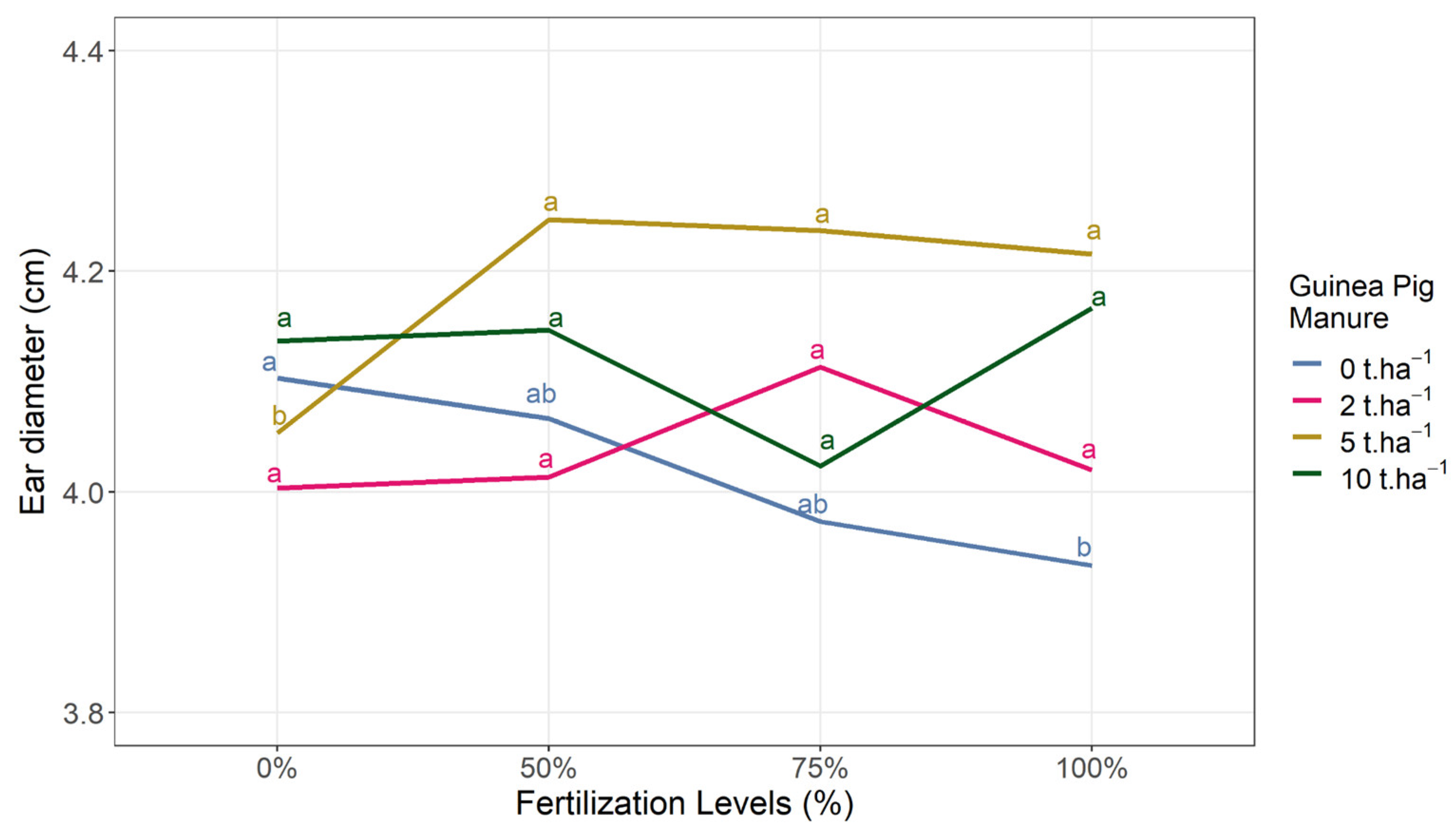

3.2. Ear Characteristics

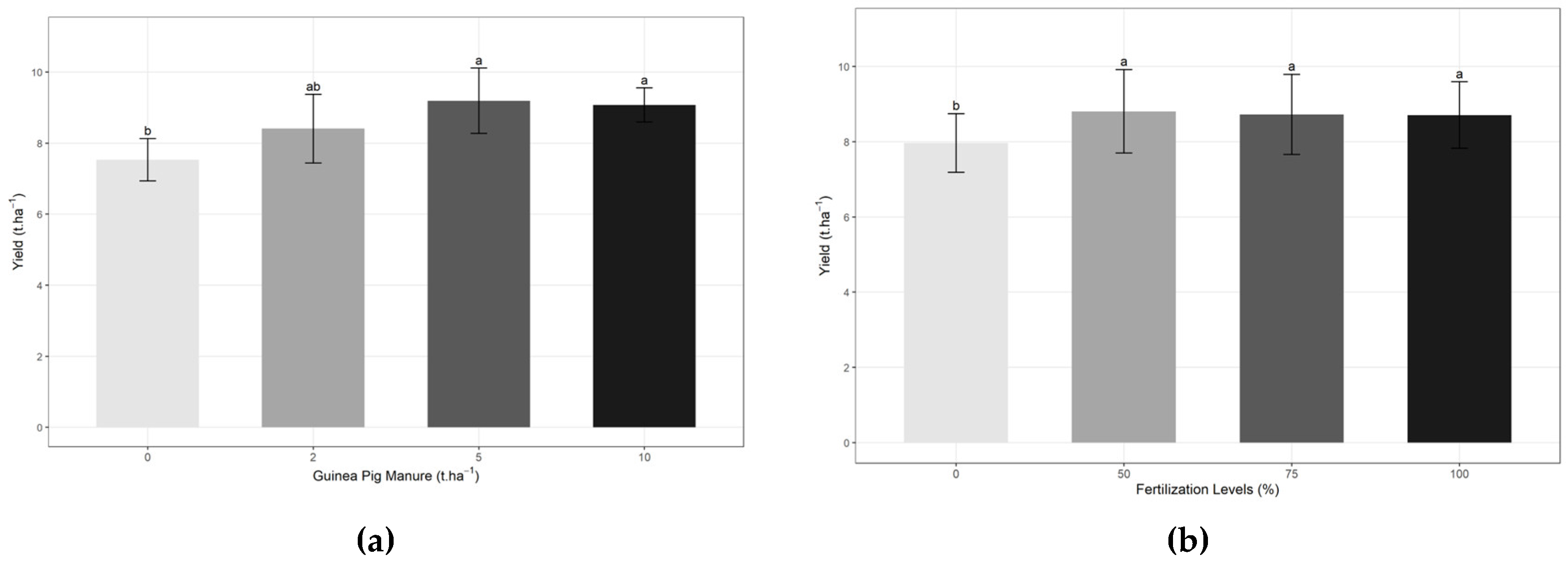

3.3. Yield

3.4. Nutritional Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shah, T.R., T.; Prasad, K.; Kumar, P. Maize- A Potential Source of Human Nutrition and Health: A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1166995. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática Encuesta Nacional Agropecuaria; 2022.

- Acosta, L.; Barreda, C.; Becerra, J.; Galarreta, L.; Huaman, O.; Moreyra, J.; Romero, C.; Rospigliosi, J. Marco Orientador de Cultivos, Campaña 2024/2025 2024.

- Barandiarán, M. Manual Técnico Del Cultivo de Maíz Amarillo Duro; 1; First.; Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria: Perú, 2020; ISBN 978-9972-44-051-9.

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global Maize Production, Consumption and Trade: Trends and R&D Implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [CrossRef]

- Grote, U.; Fasse, A.; Nguyen, T.T.; Erenstein, O. Food Security and the Dynamics of Wheat and Maize Value Chains in Africa and Asia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 617009. [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, B.M.; Vasal, S.K.; Kassahun, B.; Singh, N.N. Quality Protein Maize. Curr. Sci. 2001, 81, 1308–1319.

- Prasanna, B.M.; Cairns, J.E.; Zaidi, P.H.; Beyene, Y.; Makumbi, D.; Gowda, M.; Magorokosho, C.; Zaman-Allah, M.; Olsen, M.; Das, A.; et al. Beat the Stress: Breeding for Climate Resilience in Maize for the Tropical Rainfed Environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1729–1752. [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, H.; Pelletier, J.; Mulenga, B.P.; Subakanya, M. Climate-Smart Agriculture, Cropland Expansion and Deforestation in Zambia: Linkages, Processes and Drivers. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105482. [CrossRef]

- Mulyati; Baharuddin, A.B.; Tejowulan, R.S. Improving Maize (Zea Mays L.) Growth and Yield by the Application of Inorganic and Organic Fertilizers Plus. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 712, 012027. [CrossRef]

- Setyowati, N.; Chozin, M.; Nadeak, Y.A.; Hindarto, S.; Muktamar, Z. Sweet Corn (Zea Mays Saccharata Sturt L.) Growth and Yield Response to Tomato Extract Liquid Organic Fertilizer. Am. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. AJMRD 2022, 4, 25–32.

- Samaniego, T.; Pérez, W.E.; Lastra-Paúcar, S.; Verme-Mustiga, E.; Solórzano-Acosta, R. The Fermented Liquid Biofertilizer Use Derived from Slaughterhouse Waste Improves Maize Crop Yield. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2024, 27. [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, J.; Ngoma, H.; Mason, N.M.; Barrett, C.B. Does Smallholder Maize Intensification Reduce Deforestation? Evidence from Zambia. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 63, 102127. [CrossRef]

- Murillo Montoya, S.A.; Mendoza Mora, A.; Fadul Vásquez, C.J. La importancia de las enmiendas orgánicas en la conservación del suelo y la producción agrícola. Rev. Colomb. Investig. Agroindustrial 2019, 7, 58–68. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.W. Impact of Soil Organic Matter on Soil Properties—a Review with Emphasis on Australian Soils. Soil Res. 2015, 53, 605–635. [CrossRef]

- Avilés, D.F.; Martínez, A.M.; Landi, V.; Delgado, J.V. El cuy (Cavia porcellus): un recurso andino de interés agroalimentario The guinea pig (Cavia porcellus): An Andean resource of interest as an agricultural food source. Anim. Genet. Resour. Génétiques Anim. Genéticos Anim. 2014, 55, 87–91. [CrossRef]

- Huerta, S.S.E.; Crisanto, J.M.S.; Olivera, C.C.; Alfaro, E.G.B. Biofertilizer of Guinea Pig Manure for the Recovery of a Degraded Loam Soil. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 86, 745–750. [CrossRef]

- Meneses Quelal, W.O.; Velázquez-Martí, B.; Gaibor Chávez, J.; Niño Ruiz, Z.; Ferrer Gisbert, A. Evaluation of Methane Production from the Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Manure of Guinea Pig with Lignocellulosic Andean Residues. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 2227–2243. [CrossRef]

- Aliaga Rodríguez, Luis; Moncayo Galliano, Roberto; Rico, Elizabeth; Caycedo, Alberto Producción de Cuyes; 1era ed.; Universidad Católica Sedes Sapientiae: Lima, Perú, 2009; ISBN 978-612-4030-00-0.

- Wood, S.A.; Tirfessa, D.; Baudron, F. Soil Organic Matter Underlies Crop Nutritional Quality and Productivity in Smallholder Agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 266, 100–108. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.S.; Lense, G.H.E.; Fávero, L.F.; Oliveira Junior, B.M. de; Mincato, R.L. Nutritional Status and Physiological Parameters of Maize Cultivated with Sewage Sludge. Ciênc. E Agrotecnologia 2020, 44, e029919. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Davari; S.N. Sharma Effect of Different Combinations of Organic Materials and Biofertilizers on Productivity, Grain Quality and Economics in Organic Farming of Basmati Rice (Oryza Sativa). Indian J. Agron. 2001, 55, 290–294. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Wang, C.-H. Effects of Organic Materials on Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality of Honeydew Melon. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2016, 47, 495–504. [CrossRef]

- Herencia, J.F.; Ruiz-Porras, J.C.; Melero, S.; Garcia-Galavis, P.A.; Morillo, E.; Maqueda, C. Comparison between Organic and Mineral Fertilization for Soil Fertility Levels, Crop Macronutrient Concentrations, and Yield. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 973–983. [CrossRef]

- Menšík, L.; Hlisnikovský, L.; Pospíšilová, L.; Kunzová, E. The Effect of Application of Organic Manures and Mineral Fertilizers on the State of Soil Organic Matter and Nutrients in the Long-Term Field Experiment. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 2813–2822. [CrossRef]

- Efthimiadou, A.; Bilalis, D.; Karkanis, A.; Froud-Williams, B. Combined Organic/Inorganic Fertilization Enhance Soil Quality and Increased Yield, Photosynthesis and Sustainability of Sweet Maize Crop. AJCS 2010, 4, 722–729.

- Wei, Z.; Ying, H.; Guo, X.; Zhuang, M.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, F. Substitution of Mineral Fertilizer with Organic Fertilizer in Maize Systems: A Meta-Analysis of Reduced Nitrogen and Carbon Emissions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1149. [CrossRef]

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 Diario Oficial de La Federación. Norma Oficial Mexicana Que Establece Las Especificaciones de Fertilidad, Salinidad y Clasificación de Suelos. Estudios, Muestreo y Análisis; México, 2022.

- USEPA USEPA. METHOD 9045D. SOIL AND WASTE pH 2004; Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- ISO (International Organization for Standardization) ISO (International Organization for Standardization). ISO 10694:1995 Soil Quality — Determination of Organic and Total Carbon after Dry Combustion (Elementary Analysis); Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

- Verhulst, Nele; Sayre, Ken; Govaerts, Bram Manual de determinación de rendimiento; 1er ed.; Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT): México, 2012; ISBN 978-607-95844-7-4.

- AACC-Method 46-11 American Association of Cereal Chemists. Crude Protein – Improved Kjeldahl Method, Copper Catalyst Modification; St. Paul, USA, 2009.

- INACAL (Instituto Nacional de Calidad) Norma Técnica Peruana. NTP 205.004:2022. CEREALES Y LEGUMINOSAS. Determinación de Cenizas; NTP 205.004:2022; Perú, 2022.

- INACAL (Instituto Nacional de Calidad) Norma Técnica Peruana. NTP 209.019:1976 (Revisada El 2014). ALIMENTOS BALANCEADOS PARA ANIMALES. Métodos de Ensayo; NTP 209.019:1976 (Revisada El 2014); Perú, 2014.

- AOCS - Ba 6 - 84 American Oil Chemists’ Society. Crude Fiber in Oilseed By- Products; USA, 2017.

- Collazos, C; Phlip, W.; Viñas, E; Alvistur, J; Urquieta, A; Vásquez, J Ministerio de Salud, Instituto Nacional de Nutrición. Metodología Para Carbohidratos, Por Diferencia de Materia Seca (MS-INN); Lima, Perú, 1993.

- de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research 2023.

- Széles, A.; Horváth, É.; Vad, A.; Harsányi, E. The Impact of Environmental Factors on the Protein Content and Yield of Maize Grain at Different Nutrient Supply Levels. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2018, 764. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zheng, F.; Jia, X.; Liu, P.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B. The Combined Application of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers Increases Soil Organic Matter and Improves Soil Microenvironment in Wheat-Maize Field. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 2395–2404. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria Híbrido Simple de Maíz Amarillo Duro INIA 619 - Megahíbrido 2012.

- Silva Díaz, W.; Alfaro Jiménez, Y.; Jiménez Aponte,Ricardo J Evaluación de las características morfológicas y agronómicas de cinco líneas de maíz amarillo en diferentes fechas de siembra. UDO Agríc. 2009, 9, 743–755.

- Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Du, J.; Wang, C.; Wen, W.; Guo, X.; Zhao, C. Investigating the Genetic Basis of Maize Ear Characteristics: A Comprehensive Genome-Wide Study Utilizing High-Throughput Phenotypic Measurement Method and System. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Janampa, N.; Quiñones, A.; Salas, L.S.; Chalco, Y. Variación de sustancias húmicas de abonos orgánicos en cultivos de papa y maíz. Cienc. Suelo Argent. 2014, 32, 139–147.

- Murray-Núñez, R.; Orozco-Benítez, G.; Martínez-Orozco, S.; Avila-Ramos, F.; Bautista-Trujillo, G.; Carmona-Gasca, C.; Martínez-González, S. Composición Química Del Excremento Entero, Composta y Lixiviado de La Cama de Cuyes. Abanico Agrofor. 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Pérez-Santo, M.; Sariol-Sánchez, D.M.; Enríquez-Acosta, E.A.; Bermeo Toledo, C.R.; Llerena Ramos, L.T.; Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Pérez-Santo, M.; Sariol-Sánchez, D.M.; Enríquez-Acosta, E.A.; et al. Respuesta Agroproductiva Del Arroz Var. INCA LP-7 a La Aplicación de Estiércol Vacuno. Cent. Agríc. 2019, 46, 39–48.

- Moreno Ayala, L.; Cadillo Castro, J. Uso Del Estiércol Porcino Sólido Como Abono Orgánico En El Cultivo Del Maíz Chala. An. Científicos 2018, 79, 415. [CrossRef]

- Montoya Gómez, B.; Constanza Daza, M.; Urrutia Cobo, N. Evaluación de la mineralización de nitrógeno en dos abonos orgánicos (lombricompost y gallinaza). Suelos Ecuat. 2017, 47, 47–52.

- Mangalassery, S.; Kalaivanan, D.; Philip, P.S. Effect of Inorganic Fertilisers and Organic Amendments on Soil Aggregation and Biochemical Characteristics in a Weathered Tropical Soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 187, 144–151. [CrossRef]

- Galindo, O. Cadena Productiva de Cuy; 1st ed.; Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego: Perú, 2023;

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática Microdatos Available online: https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/ (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- FONCODES (Fondo de Cooperación para el Desarrollo Social) Crianza de Cuyes. Manual Técnico. Proyecto “Mi Chacra Emprendedora Haku Wiñay”; Ministerio de Desarrollo e Inclusión Social.: Perú, 2014;

- Chauca de Zaldivar, L. Producción de cuyes (Cavia porcellus) en los países andinos. World Anim. Rev. 1995, 83.

- Sosa-Rodrigues, B.A.; García-Vivas, Y.S. Eficiencia de uso del nitrógeno en maíz fertilizado de forma orgánica y mineral. Agron. Mesoam. 2018, 29, 207. [CrossRef]

- Widowati; Sutoyo; Karamina, H.; Fikrinda, W. Soil Amendment Impact to Soil Organic Matter and Physical Properties on the Three Soil Types after Second Corn Cultivation. AIMS Agric. Food 2020, 5, 150–169.

- Chang-An, L.; Feng-Rui, L.; Li-Min, Z.; Rong-He, Z.; Yu-Jia; Shi-Ling, L.; Li-Jun, W.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Feng-Min, L. Effect of Organic Manure and Fertilizer on Soil Water and Crop Yields in Newly-Built Terraces with Loess Soils in a Semi-Arid Environment. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 117, 123–132. [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Yan, Z.; Sun, P.; Zhang, L.; Ding, P.; Li, L.; Ren, A.; Sun, M.; Gao, Z. Effects of Nitrogen on Photosynthetic Productivity and Yield Quality of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 1448. [CrossRef]

- Aytenew, M.; Bore, G. Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Fertility and Environmental Quality: A Review. J. Plant Sci.

- Maguiña-Maza, R.M.; Francisco Perez, S.C.; Pando Cárdenas, G.L.; Sessarego Dávila, E.; Chagray Ameri, N.H.; Pujada Abad, H.N.; Airahuacho Bautista, F.E. Potencial agronómico, productivo, nutricional y económico de cuatro genotipos de maíz forrajero en el valle de Chancay, Perú. Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecu. 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.; Bocianowski, J.; Kruczek, A.; Szymańska, G.; Roszkiewicz, R. Response of Two Cultivar Types of Maize (Zea Mays L.) Expressed in Protein Content and Its Yield to Varied Soil Resources of N and Mg and a Form of Nitrogen Fertilizer.

- Çarpıcı, E.B.; Celık, N.; Bayram, G. Yield and Quality of Forage Maize as Influenced by Plant Density and Nitrogen Rate. Turk. J. Field Crops 2010, 15, 128–132.

- Gregersen, P.L.; Culetic, A.; Boschian, L.; Krupinska, K. Plant Senescence and Crop Productivity. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013, 82, 603–622. [CrossRef]

- Sierra Macías, M.; Andrés Meza, P.; Rodríguez Montalvo, F.; Palafox Caballero, A.; Gómez Montiel, N. Líneas tropicales de maíz (Zea mays L.) convertidas al carácter de calidad de proteína. Rev. Biológico Agropecu. Tuxpan 2014, 2, 315–319. [CrossRef]

- Izsáki, Z. Relationship between the Nmin Content of the Soil and the Quality of Maize (Zea Mays L.) Kernels. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 43, 77–86.

- Keeney, D.R. Protein and Amino Acid Composition of Maize Grain as Influenced by Variety and Fertility. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1970, 21, 182–184. [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Main Plot | Subplot |

| Guinea pig manure (t∙ha-1) | Fertilization (%) | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 (0-0-0) * |

| 2 | 50 (120-60-70) * | |

| 3 | 75 (180-90-105) * | |

| 4 | 100 (240-120-140) * | |

| 5 | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | 50 | |

| 7 | 75 | |

| 8 | 100 | |

| 9 | 5 | 0 |

| 10 | 50 | |

| 11 | 75 | |

| 12 | 100 | |

| 13 | 10 | 0 |

| 14 | 50 | |

| 15 | 75 | |

| 16 | 100 |

| Factor | EL (cm) | ED (cm) | RE | GR | EW (g) | GW (g) | CW (g) |

| t∙ha-1 | Guinea pig manure (G) | ||||||

| 0 | 15.51 ± 2.27 | 4.01 ± 0.26 c | 13.45 ± 1.07 | 28.84 ± 4.77 | 141.04 ± 35.77 | 116.56 ± 30.06 | 24.49 ± 6.79 |

| 2 | 15.54 ± 2.47 | 4.04 ± 0.24 c | 13.87 ± 1.12 | 28.52 ± 5.35 | 146.75 ± 38.35 | 121.69 ± 32.33 | 25.58 ± 8.06 |

| 5 | 16.31 ± 2.12 | 4.19 ± 0.22 a | 13.73 ± 1 | 29.85 ± 4.93 | 160.63 ± 34.75 | 132.69 ± 28.37 | 28.18 ± 7.24 |

| 10 | 16.08 ± 2.47 | 4.11 ± 0.21 b | 13.62 ± 1.17 | 29.71 ± 5.85 | 154.06 ± 35.4 | 127.29 ± 29.96 | 26.77 ± 5.99 |

| (%) | Fertilization (F) | ||||||

| 0 | 15.69 ± 2.15 | 4.07 ± 0.22 | 13.58 ± 0.33 b | 28.16 ± 2.36 b | 142.89 ± 11.49 b | 122.59 ± 10.05 c | 24.98 ± 5.99 |

| 50 | 16.15 ± 2.43 | 4.11 ± 0.24 | 13.53 ± 0.31 b | 30.51 ± 2.34 a | 155.21 ± 13.16 a | 125.2 ± 10.94 bc | 28.01 ± 8.24 |

| 75 | 15.98 ± 2.44 | 4.08 ± 0.28 | 13.53 ± 0.30 b | 28.3 ± 1.75 b | 149.97 ± 19.05 ab | 132.88 ± 15.42 b | 25.68 ± 7 |

| 100 | 15.62 ± 2.37 | 4.08 ± 0.24 | 13.87 ± 0.23 a | 30.59 ± 2,99 a | 155.51 ± 12.29 a | 141,8 ± 11.93 a | 26.33 ± 7.01 |

| G | 0.53 | ** | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 0.18 |

| F | 0.19 | 0.47 | ** | * | * | *** | 0.08 |

| G*F | 0.35 | ** | 0.43 | 0.66 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.18 |

| Level | Prot | Ash | Fat | Fiber | CHO | TE | Kcal Prot | Kcal Fat | Kcal CHO |

| g∙100g∙N-1 | g∙100g-1 | g∙100g-1 | g∙100g-1 | g∙100g-1 | Kcal∙100 g-1 | Kcal∙100 g-1 | Kcal∙100 g-1 | Kcal∙100 g-1 | |

| (%) | Fertilization (F) | ||||||||

| 0 | 7.87 ± 0.7 c | 1.13 ± 0.14 | 3.21 ± 0.32 | 2.56 ± 0.2 | 74.22 ± 0.98 a | 357.17 ± 1.99 b | 31.5 ± 2.75 c | 28.92 ± 2.91 | 296.75 ± 3.84 a |

| 50 | 9.08 ± 0.74 b | 1.1 ± 0.13 | 3.42 ± 0.33 | 2.51 ± 0.16 | 73.01 ± 0.9 b | 359.92 ± 3.42 a | 36.33 ± 2.96 b | 30.83 ± 2.98 | 291.92 ± 3.45 b |

| 75 | 9.57 ± 0.57 a | 1.14 ± 0.17 | 3.56 ± 0.56 | 2.5 ± 0.14 | 72.64 ± 0.74 b | 360.83 ± 3.16 a | 38.33 ± 2.39 a | 32 ± 4.94 | 290.5 ± 2.88 b |

| 100 | 9.86 ± 0.73 a | 1.03 ± 0.13 | 3.43 ± 0.28 | 2.53 ± 0.18 | 72.6 ± 0.88 b | 360.75 ± 2.05 a | 39.5 ± 3 a | 30.92 ± 2.54 | 290.33 ± 3.5 b |

| F | *** | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.82 | *** | ** | *** | 0,32 | *** |

| G*F | * | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.70 | * | 0.86 | 0.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).