Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

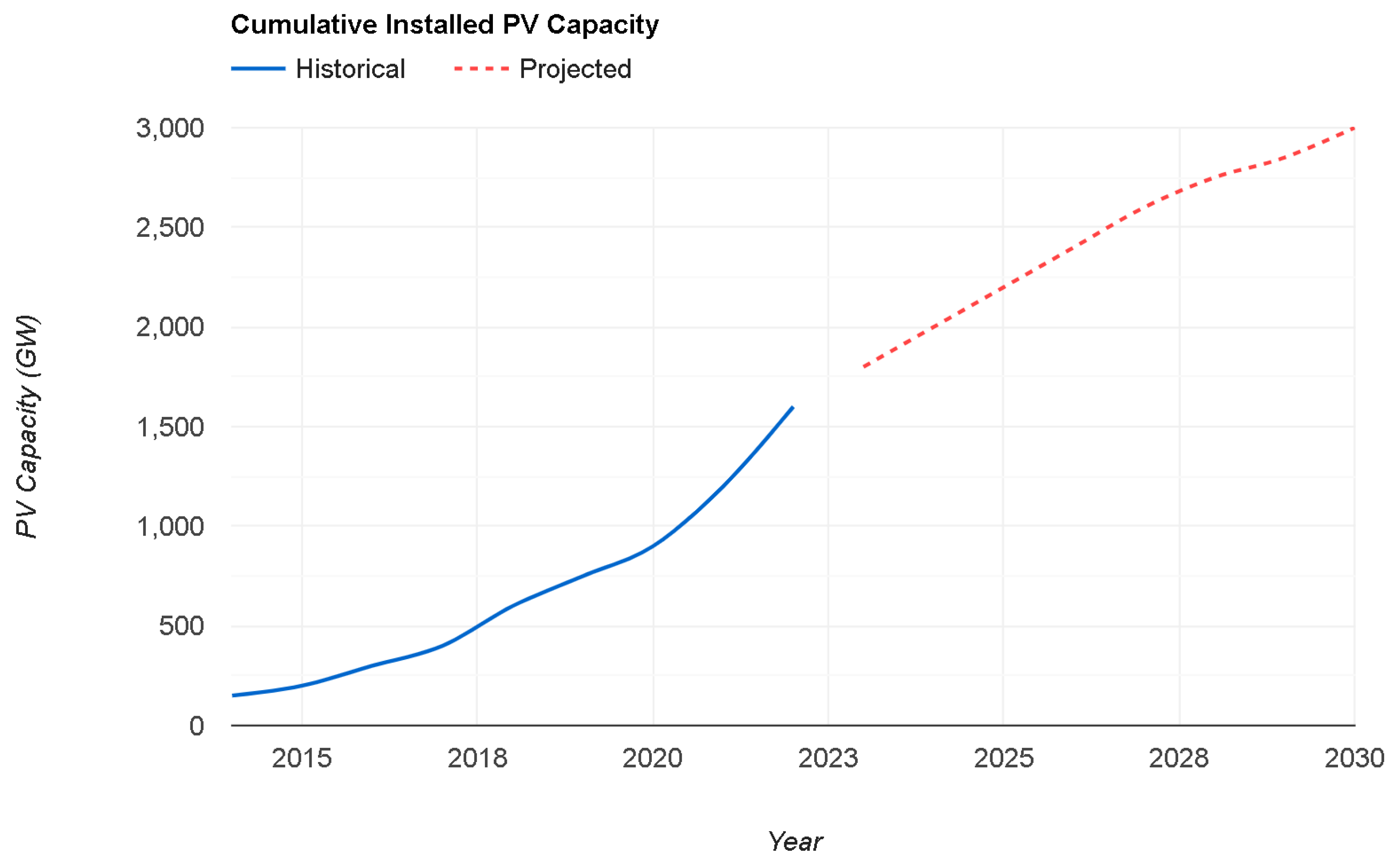

1. Introduction

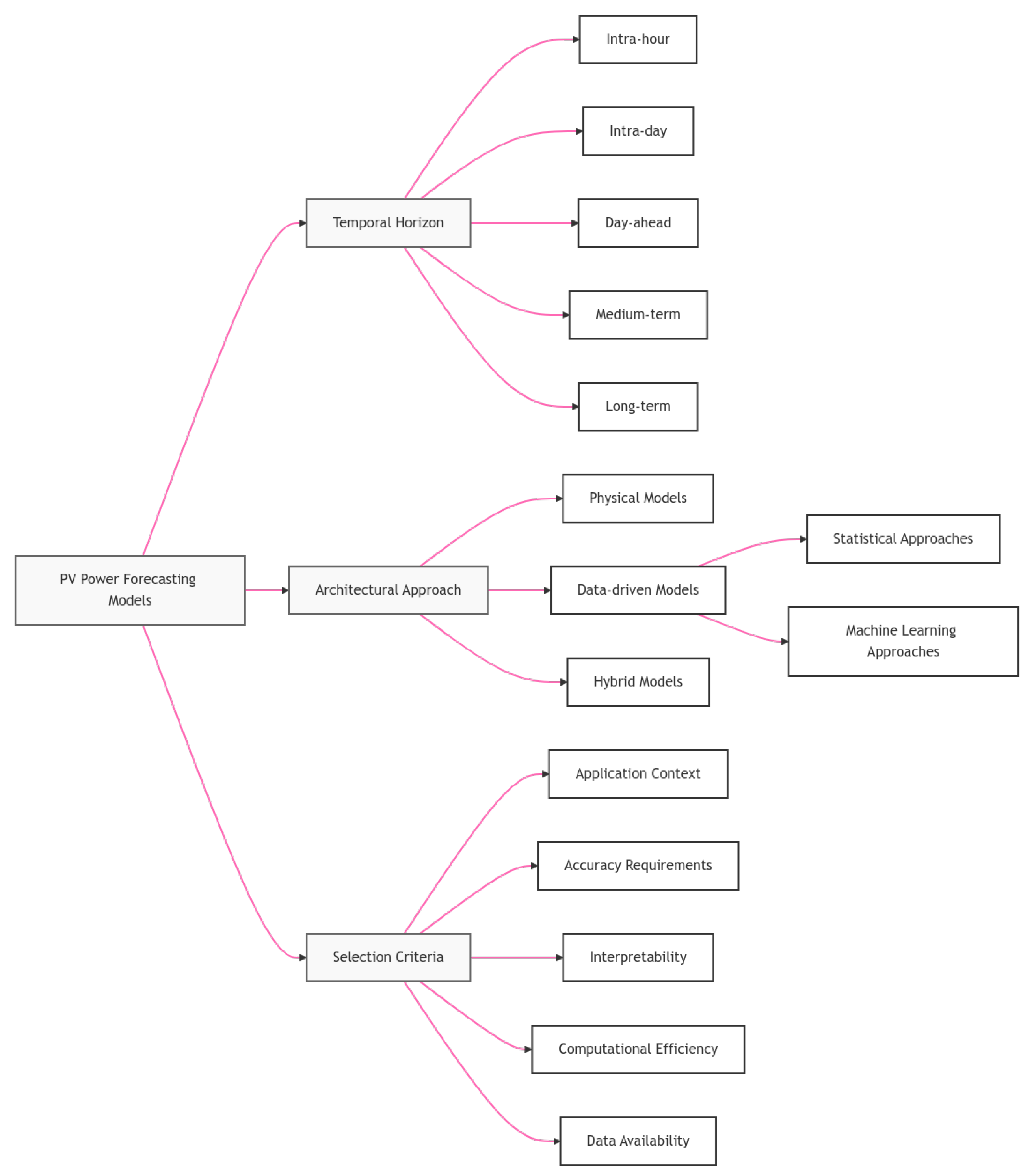

2. Taxonomy

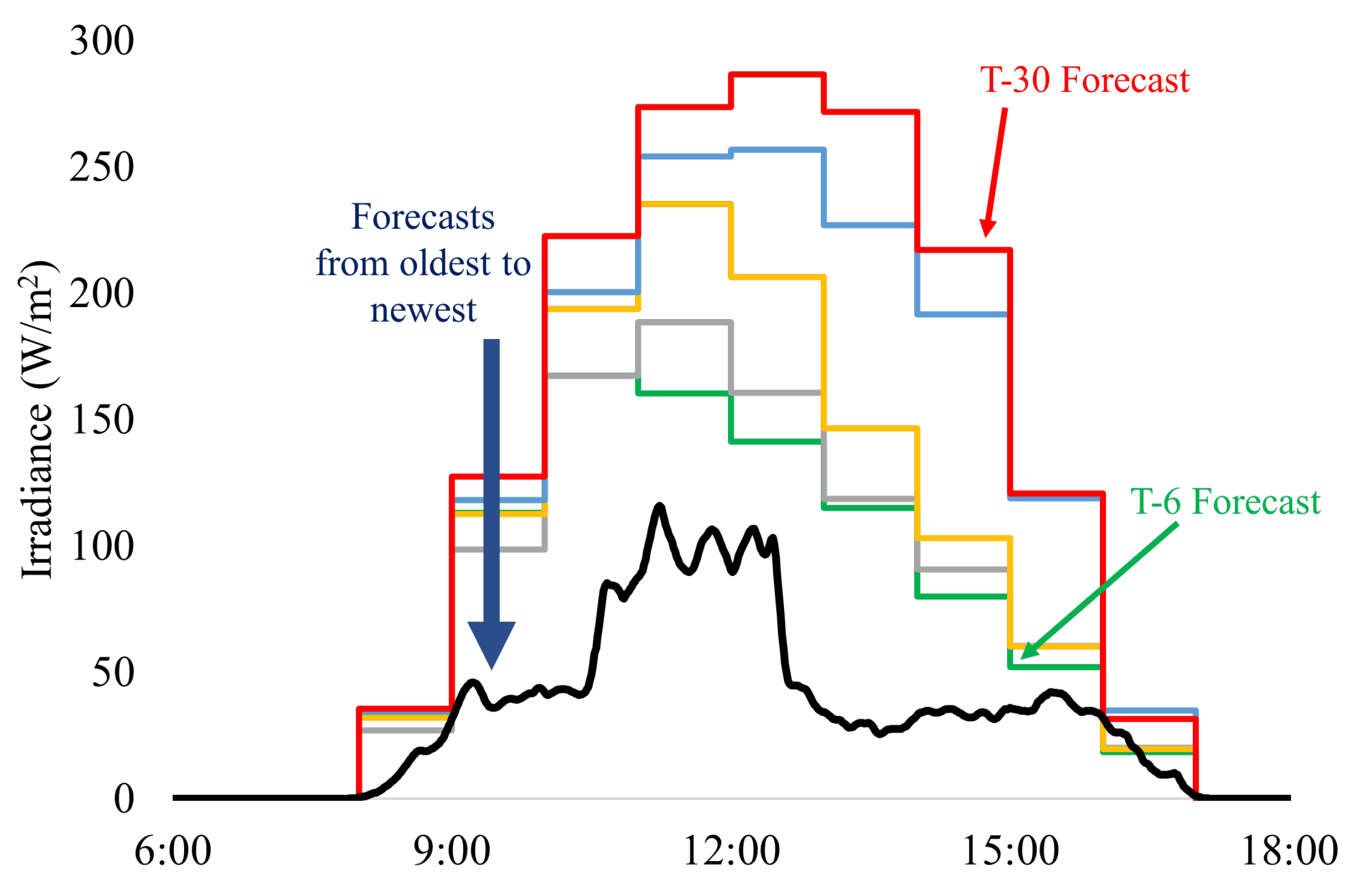

2.1. Temporal Horizon Classification

2.2. Model Architecture Classification

2.3. Physical Models

- Clear sky models: These models estimate the maximum achievable PV power under perfect cloudless situations through a combination of astronomical calculations and atmospheric measurements.

- Decomposition models: These models achieve sun irradiance decomposition into direct and diffuse fractions for better PV performance forecasting across diverse sky scenarios.

- Semi-empirical models: These models use physical equations combined with empirically obtained coefficients to generate predictions of PV power output from selected environmental factors.

2.3.1. Data-Driven Models

- Physical approaches: These models implement physical equations to convert solar irradiance data into predictions of produced electricity. Typical input sources include numerical weather predictions (NWP), satellite images, and data from meteorological stations [5].

- Statistical approaches: These models build correlations between input parameters and output based on concepts such as persistence or time series. They encompass traditional statistical methods (time series and regression) and artificial intelligence models, such as neural networks, LSTM, and SVM [5].

- Hybrid approaches: These models are an amalgamation of physical correlations with statistical techniques to improve forecasting accuracy. They generally use technical parameters of PV panels estimated from historical data [5].

- Regression models: Regression models are used to find the linear or nonlinear relations between PV power output and explanatory variables such as solar irradiance, temperature, and time of day [12].

- Time series models: These models establish temporal dependencies in PV power generation data, using methods such as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA), and exponential smoothing [6].

- Artificial neural networks (ANNs): Consisting of interconnected nodes capable of learning nonlinear relationships among input variables and PV power [15].

- Support vector machines (SVMs): The aim of SVM is to find the optimal hyperplane that separates PV power output classes or predicts continuous output values [6].

- Ensemble models: These combine several distinct forecasting models, like decision trees or ANNs, to boost predictive accuracy and robustness [7].

- Deep learning models: These have introduced extensions to ANN-wise deep architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, to capture buried hierarchical and temporal patterns in PV power data [5].

2.3.2. Hybrid Models

2.4. Selection Framework Based on Application Context

3. State-of-the-Art Forecasting Techniques

3.1. Statistical Measures for Forecast Accuracy

-

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): This is a quadratic scoring rule that provides an average magnitude for the forecast errors and weighs larger errors more heavily than smaller [5,6,10,12]. It can be expressed as:Getting better at improving upon model RMSE would be focused on outlier analysis as RMSE is well-known to be very sensitive to outliers.

-

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): This expresses the forecast error as a percentage of the observed values and is considered a dimension-free measure of accuracy [5,6,12]. It is given as:It is possible to compare the performances of the models on different PV systems and power.

3.2. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

- Deep learning architecture: Clean and better performance over shallow architectures are manifested by deep neural networks (DNNs) containing multiple hidden layers. Notably, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and LSTM networks have efficiently captured spatial and temporal dependencies, respectively [5].

- Hybrid ANN models: The enhanced accuracy and robustness result from hybridizing ANNs with other techniques, such as wavelet transforms or evolutionary algorithms [12,16]. Taking as an example wavelet-based feature extraction in combination with ANNs, these methods have shown superiority over others in handling non-stationary PV power data [7].

- Bayesian neural networks: The integration of Bayesian inference into ANNs through statistical means allows these networks to produce uncertainty measurements together with probabilistic forecasts useful for energy trading risk evaluations [9].

3.3. Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

- Kernel selection: the selection of kernel function makes a huge difference in the SVM performance. PV power forecasting is generally carried out using a gaussian radial basis function (RBF) and polynomial kernels [12]. More recently, improved results have been seen with custom kernels built for specific data characteristics [10].

- Feature selection: for SVM performance it is important to choose the most relevant input features. Optimizing feature subsets for SVM-based PV power forecasting has been applied with techniques like recursive feature elimination (RFE) and genetic algorithms (GA).

- Ensemble SVMs: The integration of several SVM models using bagging, boosting, or stacking techniques has shown improved accuracy and robustness over individual SVM models [12].

3.4. Ensemble and Hybrid Approaches

- Homogeneous ensembles: These types of ensembles, combine various models of the same type (like bagging, boosting or stacking of decision trees and ANNs). Homogenous ensembles are commonly used; however, examples like random forest (RF) and gradient boosting machines (GBM) are popular ones [5].

- Heterogeneous ensembles: These ensembles include varied models, such as by merging physical models with data-driven approaches or mixing statistical and machine learning techniques [5]. The diversity of the individual models helps capture complementary information and improve overall forecasting performance [6].

- Physical-statistical hybrid models: These models employ physical equations to model the deterministic components of PV power output and statistical techniques to take into account stochastic variations [5]. The combination of domain knowledge and data-driven learning often leads to improved accuracy and interpretability [10].

- Wavelet-based hybrid models In this approach, wavelet transforms are used to decompose the PV power time series into different frequency components [7]. Separate models are then used to forecast each frequency component, and finally, the predictions are aggregated to obtain the final prediction [18]. This approach helps to capture multiscale patterns and enhances forecasting performance [6].

- Evolutionary-neural hybrid models: Evolutionary algorithms, like genetic algorithm (GA) or particle swarm optimization (PSO), are used to optimize the hyperparameters or structure of neural net models [12]. This hybrid strategy combines the comprehensive search feature of evolutionary algorithms with the learning capability of neural networks [5].

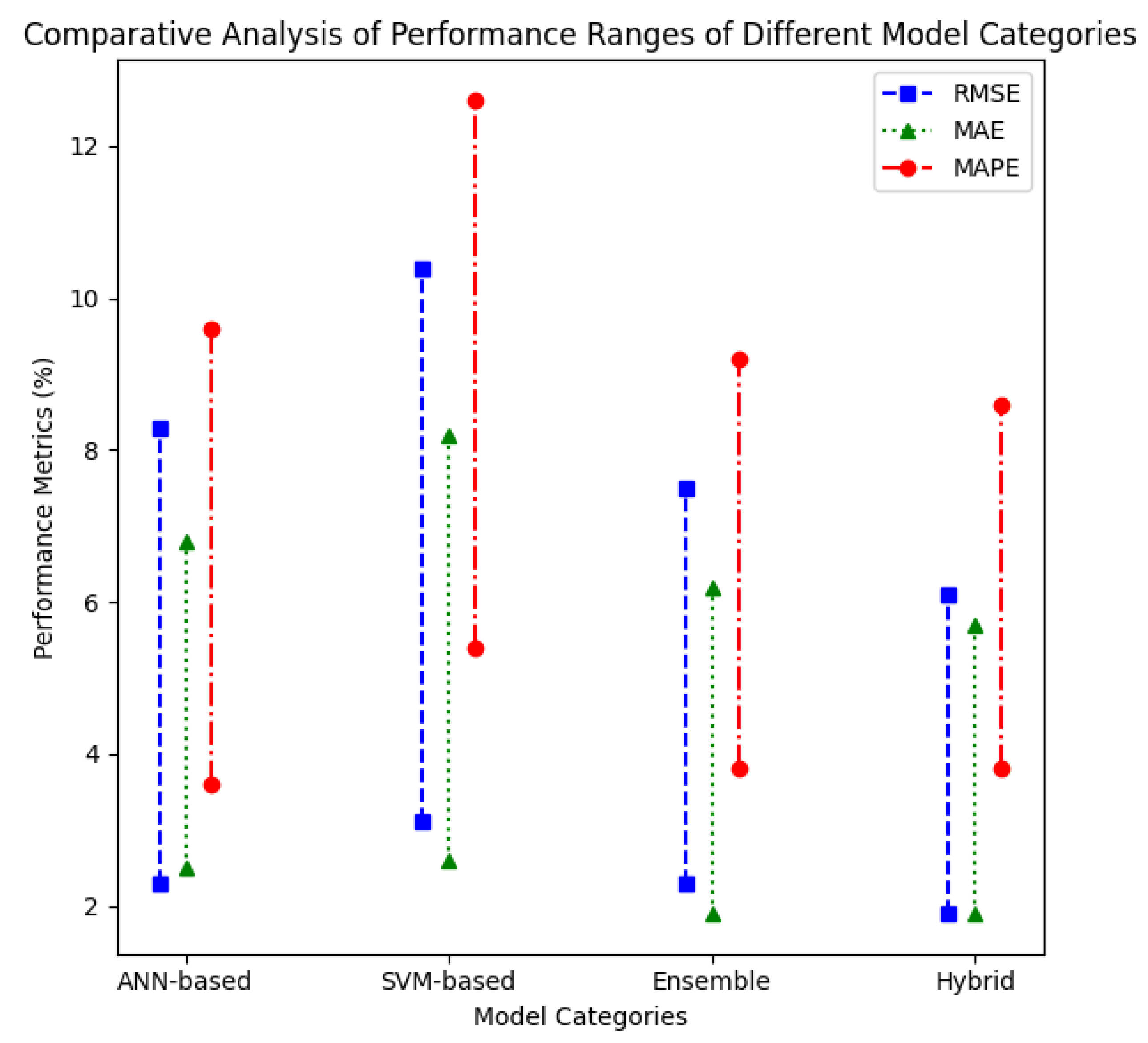

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Model Performance

4. Model Optimization Strategies

4.1. Hyperparameter Tuning and Feature Selection

- Grid search: This exhaustive search method evaluates the model performance for all possible combinations of hyperparameter values within a predefined range [6]. While grid search is straightforward to implement, it can be computationally expensive, especially for models with a large number of hyperparameters [5].

- Random search: An exhaustive search that assesses the model accuracy on every combination of possible hyperparameter values outlined under a specified range [6]. Although it is simple to implement, grid search can be quite slow for models with many hyperparameters [5]. Research has also shown random search to be more efficient than grid search in medium to high-dimensional hyperparameter search spaces [10].

- Bayesian optimization: This sequential model-based optimization approach starts by building a (probabilistic) model of the objective function (e.g., forecast accuracy), and then uses this model to select the hyperparameter values to evaluate next [7]. It allows a probabilistic approach to the parameter search and has been proven to be more efficient and effective than grid search and random search.

- Genetic algorithms (GA): The GA-based hyperparameter tuning treats the optimization problem as a process of evolutionary optimization, whereby a population of candidate hyperparameter settings evolves through generations via selection, crossover, and mutation operations [12]. GA has been shown to be effective in finding near-optimal hyperparameter configurations for PV power forecasting models [5].

- LSTM-WGAN: A data imputation technique using Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is developed to mitigate the difficulties stemming from inadequate prediction results due to missing data in PV power records. This method introduces a data-driven GAN framework with quasi-convex characteristics to ensure the smoothness of the imputed data with the existing data and employs a gradient penalty mechanism and a single-batch multi-iteration strategy for stable training [19].

- Filter methods: These methods assess the relevance of each feature independently of the learning algorithm. The relevance is usually checked using statistical measures such as correlation, mutual information, or chi-squared tests. Features are ranked based on their individual relevance scores, and the top-ranked features are selected for model training [5].

- Wrapper methods: These methods assess the quality of various subsets of features using the learning algorithm itself as part of the process of selection [12]. Examples include recursive feature elimination (RFE) and genetic algorithms (GA) for feature subset search. Wrapper methods usually out-perform filter methods but are computationally quite expensive [7].

- Embedded methods: These methods use feature selection during the model fitting process by taking advantage of the inherent feature importance metrics in the learning algorithm [10]. Regularization techniques such as L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization can provide some form of encouragement to model sparse feature representations, thereby allowing them to identify the most relevant features [5].

- Temporal feature extraction: Derived features such as moving averages, lag values, and rolling statistics can capture short-term and long-term temporal dependencies in the PV power time series [6].

- Spatial feature extraction: Techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) and wavelet transforms can be used to extract spatial patterns and multi-resolution information from the input features [7].

- Domain-specific feature generation: Incorporating expert knowledge and physical understanding of the PV system can help create meaningful features, such as the clearness index, which captures the ratio of actual solar irradiance to the theoretical maximum [10].

4.2. Evolutionary and Swarm Intelligence Algorithms

- Feature selection GA and PSO successfully select the most crucial set of input features for PV power forecasting models which reduces computational requirements and enhances understanding of results [7].

- Hyperparameter tuning: DE, PSO, and ABC have been employed to search for the optimal hyperparameter settings of various forecasting models, such as ANNs, SVMs, and random forests, resulting in improved predictive performance [5].

- Model structure optimization: GAs and ACO have enabled researchers to discover efficient model architectures by means of optimizing both neural network structures and the patterns of network connections [5].

- Ensemble model generation: DE and ABC have been utilized to generate diverse and complementary forecasting models, which are combined into a robust ensemble prediction [6].

4.3. Hybrid Optimization Frameworks

- GA-ANN hybrid: The GA is used in this framework to get the structural optimization and hyperparameter optimization of an ANN model. Conventional gradient-based methods are applied to training the ANN model. The ANN parameters are finely tuned by gradient methods, while GA is able to search the immense search space of model configurations [12].

- PSO-SVM hybrid: This system enables the use of PSO to identify optimal SVM model hyperparameters including kernel function and regularization parameter and kernel parameters. The global search feature of PSO enables the identification of optimal hyperparameter settings that lead to accurate PV power predictions when trained over an SVM model [5].

- DE-Ensemble hybrid: This framework produces different base forecasting models through DE optimization while ensemble techniques such as stacked or weighted averaging determine the model selection according to [7]. By using the DE algorithm users can optimize the ensemble weights or stacking model to achieve minimum ensemble error [6].

- ACO-Fuzzy hybrid: This framework integrates Ant Colony Optimization with Fuzzy logic systems for PV power forecasting [12]. ACO facilitates optimization of fuzzy model parameters by finding the most suitable membership functions and rule structures and the fuzzy system delivers understandable forecasting results.

5. Performance Evaluation Metrics and Frameworks

5.1. Evaluation under Different Weather Conditions

- Partially cloudy conditions: Partially cloudy conditions introduce significant variability in solar irradiance, leading to rapid fluctuations in PV power output [7]. Under these evaluation conditions analysts can measure forecasting models’ success in representing cloud transit dynamics and power system instability [10].

- Variable sky conditions: Sunlight spikes caused by "broken clouds" could lead to major positive and negative fluctuations in the irradiance pattern measured at the PV site location. Assessment of how these variable sky conditions affect PV energy generation is important for increasing forecast accuracy and understanding the uncertainties involved [21].

5.2. Benchmarking and Model Comparison Strategies

- Benchmark datasets: The development and distribution of publicly accessible benchmark datasets stands essential for PV power forecasting progress and model determination [5]. These datasets should cover a variety of configurations of PV systems from different geographical regions with different weather conditions to accurately evaluate how generalizable the models are. For instance, [4] assessed the global horizontal irradiance (GHI) of four global reanalysis datasets-MERRA-2, ERA5, ERA5-Land, and CFSv2-in a comparison applied across 35 observation stations scattered throughout Brazil and ground-based measurements to determine their aptitude for the representation of hourly GHI. Such studies provide valuable insights into the suitability of different data sources for PV power forecasting in regions with limited observational time series measurements.

- Evaluation metrics: Standardizing the evaluation metrics used for model comparison is essential for ensuring that results are comparable and meaningful with regards to performance assessment [12]. These should include the statistical measures discussed in Section 3.1: RMSE, MAE, and MAPE, along with domain-specific measures like forecast skill [7].

- Cross-validation: Employing cross-validation techniques, such as k-fold or leave-one-out cross-validation, helps assess the model’s performance on unseen data and reduces the risk of overfitting [6]. Through sequential training and testing partitions of the data with cross-validation techniques we can achieve better estimates of model generalization ability [5].

- Statistical significance tests: Conducting statistical significance tests, such as t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, is important to determine whether the performance differences between models are statistically significant or merely due to chance [10]. Such tests provide a rigorous basis through which models can be compared and ranked [12].

- Model complexity and interpretability: Model complexity alignment with interpretability needs to be evaluated jointly with predictive performance for practical utilization purposes [7]. We should prefer less complex models having better interpretability over more complex models even when these simpler choices allocate slightly fewer accurate predictions [6].

5.3. Operational and Economic Impact Assessment

- Grid stability: Precise PV power predictions support grid operators in maintaining power supply-demand equilibrium thus minimizing system instability that causes blackouts [5]. For PV power generation variability prediction operators must take charge of other generation resources dispatch to maintain grid stability [10].

- Reserve capacity requirements: Accurate PV power forecasting enables grid operators to reach the best possible decisions about reserve capacity deployment because unexpected renewable energy generation changes need compensation [12]. The accuracy of PV power forecasts helps decrease both the system’s operational expenses and enhance its productivity [7].

- Curtailment reduction: When the power grid experiences limits to its capacity to accept PV system electricity outputs it results in power generation curtailment [6]. Grid operators who predict PV power with accuracy develop proactive measures against curtailment events through generator dispatch adjustments or demand response program implementation [5].

- Module lifespan prediction: Long-term reliability tests for high power density PV modules have shown that standard tests, like IEC 61215, may not adequately assess the long-term reliability of these modules. A new combined stress test concept, which includes light-combined damp heat cycles, has been introduced to better predict the rate of degradation and the service life of PV modules based on latent heat analysis [23].

- Energy market participation: Accurate forecasts for PV power enable PV system owners and operators to effectively participate in energy markets (day-ahead and real-time markets) [10]. By providing reliable estimates of their expected power output, PV system owners can optimize their bidding strategies and thus maximize their revenues [12].

- Reduced imbalance costs: In many electricity markets, generators are penalized for deviations between their scheduled and actual power output [7]. If their actual generation differs substantially from their forecast values, PV system owners could face substantial imbalance costs [6]. Accurate PV power forecasts help minimize these imbalance costs by reducing the mismatch between predicted and actual generation [5].

- Investment planning: The forecasting models of PV power systems serve as fundamental elements for establishing strong investment decisions in PV project development [10]. Providing reliable estimates of expected power output over the lifetime of a project should enable an investor to assess the financial viability of PV installations and make proper decisions on capacity expansions and technology upgrades [12].

6. Recent Innovations in Photovoltaic Power Forecasting

6.1. Advanced Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques

6.2. Integration of Diverse Data Sources

6.3. Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithms

6.4. Real-Time and On-Demand Forecasting Applications

7. Challenges and Future Opportunities

7.1. Variability and Uncertainty in Solar Power Generation

7.2. Integration with Grid Operations

7.3. Data Quality and Availability

7.4. Model Complexity and Computational Requirements

7.5. Adaptability to Changing Conditions

7.6. Future Research Directions

- Enhanced Data Integration: Multiple data integration between satellite images and sky images and NWP data gives researchers an expanded perspective to study PV power generation factors. Using data from various sources to build forecasts results in increased accuracy and reliability estimates [27].

- Advanced Optimization Techniques: Metaheuristic optimization algorithms like the PSO, GA, and DE can improve the internal configurations of forecasting models that help enhance the forecasting model’s performance [12].

- Real-Time and Scalable Solutions: Solutions such as cloud-based platforms to offer a real-time, scalable forecasting tool would lead to the large-scale availability of PV power forecasts for many end-users, given that they are made freely accessible [27].

- Adaptive Learning Models: The adaptive learning models, which may effectuate dynamic learning through access to new data and rapid changes in conditions, is essential in achieving high prediction accuracy in time [10].

8. Conclusions

List of Abbreviations and Notations

Abbreviations:

- ANN: Artificial Neural Network

- ARIMA: AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average

- CNN: Convolutional Neural Network

- DE: Differential Evolution

- DL: Deep Learning

- EP: Evolutionary Programming

- GA: Genetic Algorithm

- GRU: Gated Recurrent Unit

- LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory

- MAE: Mean Absolute Error

- MAPE: Mean Absolute Percentage Error

- ML: Machine Learning

- NWP: Numerical Weather Prediction

- PSO: Particle Swarm Optimization

- PV: Photovoltaic

- R²: Coefficient of Determination

- RF: Random Forest

- RMSE: Root Mean Square Error

- RNN: Recurrent Neural Network

- SARIMA: Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average

- SVM: Support Vector Machine

- SVR: Support Vector Regression

- WGAN: Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network

References

- Bizzarri, F.; Nitti, S.; Malgaroli, G. The use of drones in the maintenance of photovoltaic fields. 2019, Vol. 119. [CrossRef]

- Spertino, F.; Chiodo, E.; Ciocia, A.; Malgaroli, G.; Ratclif, A. Maintenance Activity, Reliability Analysis and Related Energy Losses in Five Operating Photovoltaic Plants. 2019. [CrossRef]

- PVPS, I. Trends in Photovoltaic Applications 2024: Survey Report of Selected IEA Countries between 1992 and 2023; Report IEA-PVPS T1-43: 2024, IEA PVPS Task 1, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, M.; Aguilar, S.; Souza, R.; Cyrino Oliveira, F. Global Horizontal Irradiance in Brazil: A Comparative Study of Reanalysis Datasets with Ground-Based Data. Energies 2024, 17, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dahidi, S.; Madhiarasan, M.; Al-Ghussain, L.; Abubaker, A.; Ahmad, A.; Alrbai, M.; Aghaei, M.; Alahmer, H.; Alahmer, A.; Baraldi, P.; et al. Forecasting Solar Photovoltaic Power Production: A Comprehensive Review and Innovative Data-Driven Modeling Framework. Energies 2024, 17, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanetu, K. Solar Photovoltaic Power Forecasting: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.; Mekhilef, S.; Mokhlis, H.; Shah, N. Review on Forecasting of Photovoltaic Power Generation Based on Machine Learning and Metaheuristic Techniques. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2019, 13, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, B.; Kuehnert, J.; Lorenz, E.; Kramer, O.; Heinemann, D. Comparing support vector regression for PV power forecasting to a physical modeling approach using measurement, numerical weather prediction, and cloud motion data. Sol. Energy 2016, 135, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateko, A.; Yang, H.T.; Huang, C.M. Short-Term PV Power Forecasting Using a Regression-Based Ensemble Method. Energies 2022, 15, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Chouder, A.; Oudira, H.; Silvestre, S.; Kichou, S. Improving Photovoltaic Power Prediction: Insights through Computational Modeling and Feature Selection. Energies 2024, 17, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, G.; Cocina, V.; Di Leo, P.; Spertino, F.; Massi Pavan, A. Error Assessment of Solar Irradiance Forecasts and AC Power from Energy Conversion Model in Grid-Connected Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2016, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.; Tey, K.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Mekhilef, S.; Idris, M.; Van Deventer, W.; et al. Forecasting of photovoltaic power generation and model optimization: A review. Deakin University. Journal contribution, 2018.

- Saigustia, C.; Pijarski, P. Time Series Analysis and Forecasting of Solar Generation in Spain Using eXtreme Gradient Boosting: A Machine Learning Approach. Energies 2023, 16, 7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.C.; Tu, C.S.; Hong, C.M.; Lin, W.M. A Review of State-of-the-Art and Short-Term Forecasting Models for Solar PV Power Generation. Energies 2023, 16, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantillo-Luna, S.; Moreno-Chuquen, R.; Celeita, D.; Anders, G. Deep and Machine Learning Models to Forecast Photovoltaic Power Generation. Energies 2023, 16, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; So, D.; Jo, J.; Kang, N.; Hwang, E.; Moon, J. Two-Stage Neural Network Optimization for Robust Solar Photovoltaic Forecasting. Electronics 2024, 13, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; et al. Transient Stability Assessment Method for Power System Based on SVM with Adaptive Parameters Adjustment. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC); 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, D.; Dai, W.; Wu, Q. Informer Short-Term PV Power Prediction Based on Sparrow Search Algorithm Optimised Variational Mode Decomposition. Energies 2024, 17, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xuan, L.; Gong, D.; Xie, X.; Zhou, D. A Long Short-Term Memory–Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network-Based Data Imputation Method for Photovoltaic Power Output Prediction. Energies 2025, 18, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudys, A.; Gaidukevičius, J. Forecasting Solar Energy Generation and Household Energy Usage for Efficient Utilisation. Energies 2024, 17, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, G.; Cocina, V.; Di Leo, P.; Spertino, F. Weather forecast-based power predictions and experimental results from photovoltaic systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion, IEEE, Ischia, Italy; 2014; pp. 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Li, X.; Scott, A.; Sun, Y.; Venugopal, V.; Brandt, A. SKIPP’D: A SKy Images and Photovoltaic Power Generation Dataset for short-term solar forecasting. Solar Energy 2023, 255, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, W.; Choi, J.; Kim, G.; Hyun, J.; Ahn, H.; Park, N. Predicting Photovoltaic Module Lifespan Based on Combined Stress Tests and Latent Heat Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensler, A.; Henze, J.; Sick, B.; Raabe, N. Deep Learning for solar power forecasting — An approach using AutoEncoder and LSTM Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), 2016; pp. 002858–002865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, I.; Amor, D.; Gutiérrez. Recent Trends in Real-Time Photovoltaic Prediction Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, M.; Guo, M.; et al. Innovative approaches to solar energy forecasting: unveiling the power of hybrid models and machine learning algorithms for photovoltaic power optimization. J Supercomput 2025, 81, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, P.; Remund, J.; Vallance, L. Short-term solar power forecasting based on satellite images. In Renewable Energy Forecasting from Model to Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ciocia, A.; Chicco, G.; Gasperoni, A.; Malgaroli, G.; Spertino, F. Photovoltaic Power Prediction from Medium-Range Weather Forecasts: a Real Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT EUROPE); 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagne, M.; David, M.; Lauret, P.; Boland, J.; Schmutz, N. Review of Solar Irradiance Forecasting Methods and a Proposition for Small-Scale Insular Grids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Yang, B.; Han, Y.; Chen, N. State-Of-The-Art Solar Energy Forecasting Approaches: Critical Potentials and Challenges. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10, 875790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyte, A.; Van Thong, V.; Belmans, R.; Nijs, J. Voltage fluctuations on distribution level introduced by photovoltaic systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Conv. 2006, 21, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Ting, K.; Zhou, Z. Isolation-based anomaly detection. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data (TKDD) 2012, 6, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

| Temporal Horizon | Range | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-hour | < 1 hour | Real-time dispatch, power quality control |

| Intra-day | 1 - 24 hours | Day-ahead scheduling, energy trading |

| Day-ahead | 24 - 48 hours | Maintenance planning, resource allocation |

| Medium-term | 48 hours - 1 month | Asset management, seasonal planning |

| Long-term | > 1 month | Capacity expansion, policy making |

| Application Context | Key Requirements | Suitable Model Types |

|---|---|---|

| High accuracy, | Data-driven models | |

| Grid operation | Fast computation | (ML, DL), |

| Hybrid physical-statistical models | ||

| Probabilistic forecasts, | Ensemble models, | |

| Energy trading | Uncertainty | Bayesian |

| quantification | approaches | |

| Interpretability, | Physical models, | |

| PV plant monitoring | System-specific | Semi-empirical |

| insights | models | |

| Robustness to data | Ensemble models, | |

| Performance assessment | quality, Handling | Deep learning |

| missing data | models | |

| Spatial aggregation, | Spatio-temporal | |

| Regional forecasting | Scalability | models, |

| Hierarchical models |

| Model | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Suitable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedforward | RMSE: 3.2-7.6%, | Short-term | |

| MLP [15] | architecture, | MAE: 2.5-5.9% | forecasting, |

| Backpropagation | PV plant | ||

| learning | monitoring | ||

| Spatial feature | RMSE: 2.8-6.4%, | Regional | |

| CNN [5] | extraction, | MAPE: 4.2-9.6% | forecasting, |

| Hierarchical | Spatio-temporal | ||

| learning | modeling | ||

| Temporal | RMSE: 3.5-8.3%, | Medium-term | |

| LSTM [5] | dependency | MAE: 2.9-6.8% | forecasting, |

| capture, | Time series | ||

| Long-term memory | analysis | ||

| Multi-resolution | RMSE: 2.3-5.7%, | Non-stationary | |

| Wavelet-ANN [7] | analysis, | MAPE: 3.6-8.5% | data, |

| De-noising | Feature | ||

| and compression | extraction |

| Model | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Suitable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-linear | RMSE: 4.5-9.7%, | Short-term | |

| mapping, | MAE: 3.8-8.2% | forecasting, | |

| SVM-RBF [12] | Gaussian | Regression | |

| kernel | tasks | ||

| function | |||

| Polynomial | RMSE: 5.2-10.4%, | Non-linear | |

| kernel | MAPE: 6.3-12.6% | relationships, | |

| SVM-Poly [10] | function, | High-dimensional | |

| Degree | input | ||

| optimization | |||

| Genetic | RMSE: 3.9-8.5%, | Feature | |

| feature | MAE: 3.2-7.1% | optimization, | |

| GA-SVM [7] | selection, | Computationally | |

| Optimal | efficient | ||

| subset | |||

| identification | |||

| Recursive | RMSE: 4.2-9.1%, | High-dimensional | |

| feature | MAPE: 5.4-11.3% | input, | |

| RFE-SVM [17] | elimination, | Feature | |

| Backward | ranking | ||

| feature | |||

| selection | |||

| Multiple | RMSE: 3.1-7.3%, | Improved | |

| SVM | MAE: 2.6-6.2% | accuracy, | |

| Ensemble-SVM [12] | combination, | Robustness | |

| Bagging, | enhancement | ||

| boosting, | |||

| stacking |

| Model | Key | Performance | Suitable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Features | Metrics | Applications | |

| Bagging of | RMSE: 2.9-6.8%, | Short-term | |

| decision trees, | MAE: 2.4-5.7% | forecasting, | |

| Random Forest [6] | Feature | Variable | |

| importance | selection | ||

| ranking | |||

| Sequential | RMSE: 3.2-7.5%, | Nonlinear | |

| Gradient Boosting [5] | tree boosting, | MAPE: 4.3-9.2% | relationships, |

| Gradient-based | Medium-term | ||

| optimization | forecasting | ||

| Physical | RMSE: 2.6-6.1%, | Improved | |

| modeling of | MAE: 2.2-5.3% | interpretability, | |

| components, | Domain | ||

| Physical-ANN hybrid [10] | ANN for | knowledge | |

| stochastic | integration | ||

| variation | |||

| Multi-scale | RMSE: 2.5-5.9%, | Non-stationary | |

| decomposition, | MAPE: 3.8-8.6% | data, | |

| Wavelet-SVM hybrid [7] | SVM for | Robustness | |

| component | improvement | ||

| forecasting | |||

| GA for | RMSE: 2.3-5.4%, | Hyperparameter | |

| ANN | MAE: 1.9-4.6% | tuning, | |

| GA-ANN hybrid [5] | optimization, | Model | |

| Evolutionary | structure | ||

| learning | optimization |

| Algorithm | Category | Main Characteristics | Optimization Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Evolutionary algorithm | Selection, crossover, and mutation-based optimization | Feature selection; hyperparameter-tuning; model structure optimization |

| Differential Evolution (DE) | Evolutionary algorithm | Mutation and crossover-based optimization on vectors in search space | Hyperparameter-tuning; model structure optimization |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Swarm intelligence algorithm | Particle move in search space based on personal and global best positions | Feature selection; hyperparameter-tuning; model structure optimization |

| Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) | Swarm intelligence algorithm | Pathfinding based on pheromone deposition by ants | Feature selection; hyperparameter-tuning; model structure optimization |

| Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) | Swarm intelligence algorithm | Mimics foraging behavior of honeybees | Feature selection; hyperparameter-tuning; ensemble model generation |

| Framework | Optimization Techniques | Main Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| GA-ANN-hybrid | Genetic Algorithm; | Efficient exploration of model |

| Artificial Neural Network | configuration space; fine-tuning of model parameters; improved generalization and robustness | |

| PSO-SVM-hybrid | Particle Swarm Optimization; | Effective hyperparameter optimization; |

| Support Vector Machine | enhanced model accuracy and robustness; reduced computational complexity | |

| DE-Ensemble-hybrid | Differential Evolution; | Discovery of diverse and complementary models; |

| Ensemble methods | improved performance and stability; robustness to individual model weaknesses | |

| ACO-Fuzzy-hybrid | Ant Colony Optimization; | Optimization of fuzzy rule-based systems; |

| Fuzzy Logic Systems | incorporation of domain-specific knowledge for transparent reasoning |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).