Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

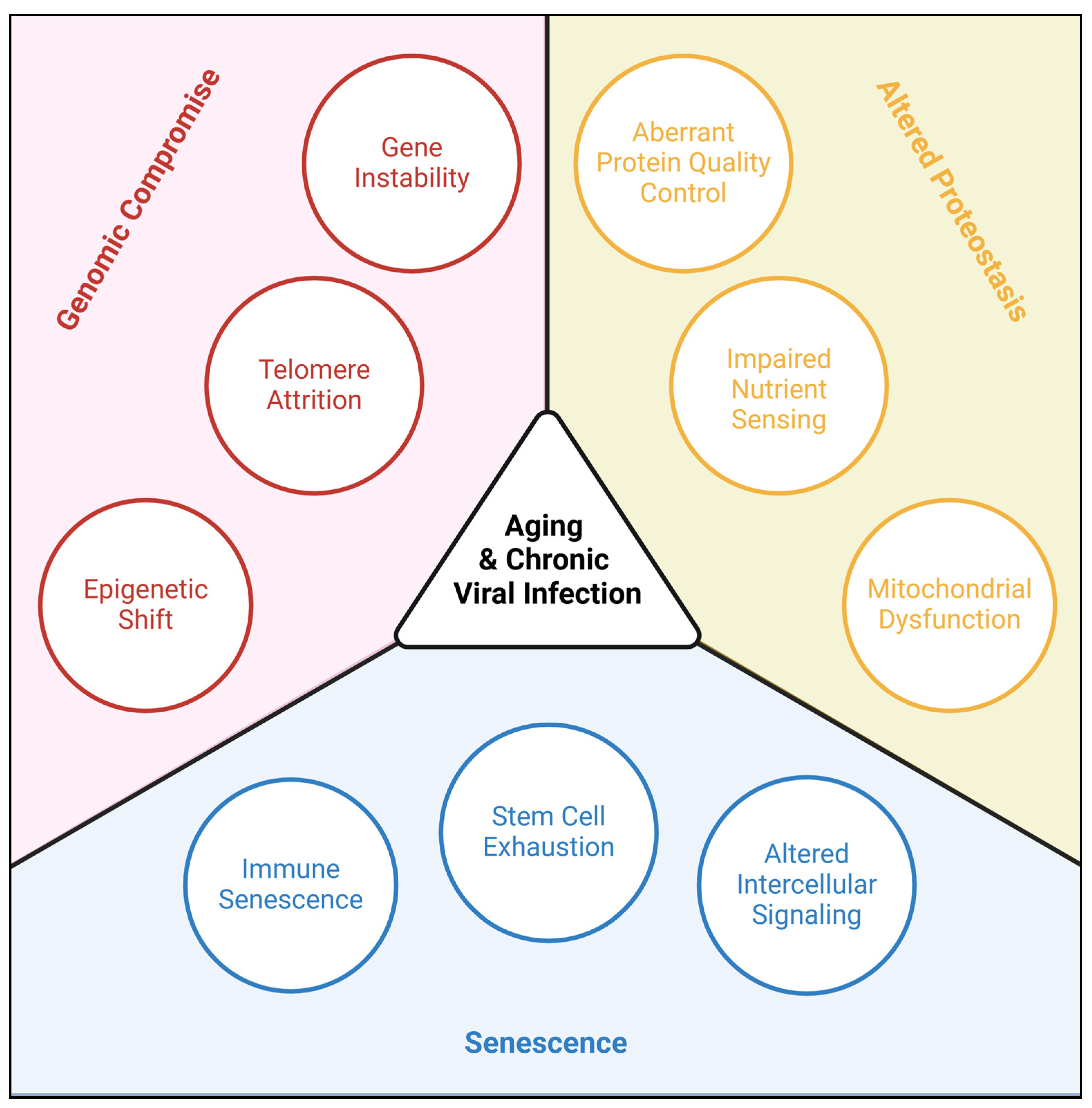

1. Introduction

2. Altered Proteostasis

| Genus | Genome | Capsid | Virus | Associated Diseases |

| Coronavirus | Linear +ssRNA |

Enveloped Icosahedral |

SARS-CoV-2 | COVID19 |

| Enteroviruses | Linear +ssRNA |

Non-enveloped Icosahedral |

Coxsackievirus | Hand-Foot-and-Mouth, Viral Meningitis |

| Echovirus | Viral Meningitis | |||

| Poliovirus | Paralytic Poliomyelitis | |||

| Flaviviruses | Linear +ssRNA |

Enveloped Dimeric αhelix |

Dengue | Breakbone Fever |

| Japanese Encephalitis | Viral Encephalitis | |||

| West Nile | Viral Encephalitis | |||

| Herpesviruses | Linear dsDNA |

Enveloped Icosahedral |

Herpes Simplex 1 | Cold Sores, Viral Encephalitis |

| Varicella Zoster | Chicken Pox, Shingles |

|||

| Epstein Barr | Cancer (Lymphoma, Leukemia, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma), Infectious Mononucleosis, Multiple Sclerosis |

|||

| Cytomegalovirus | Congenital Birth Defects, Viral Encephalitis |

|||

| Polyomaviruses | Circular dsDNA |

Non-enveloped Icosahedral |

JC | Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy, Cancer (Glioblastoma, Colorectal Carcinoma) |

| Lentiviruses | Linear +ssRNA |

Enveloped Cone-shaped |

HIV | Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorder |

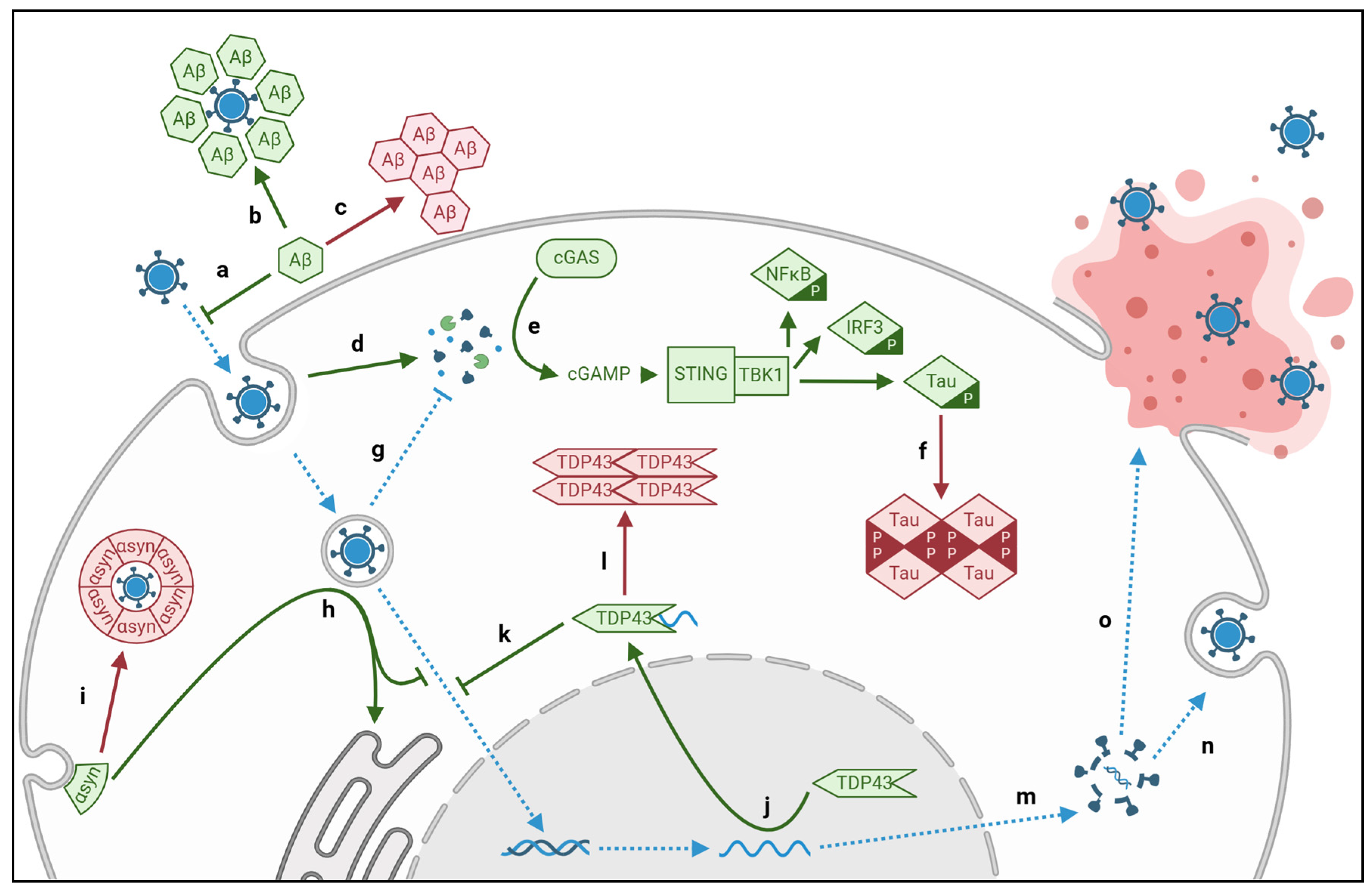

2.1. Viral aggregation of intracellular Tau and extracellular Amyloid-β

| Disease | Proteinopathy | Pathway | Virus | Protein |

| Alzheimer’s Dementia |

Extracellular Aβ Plaques |

Amyloidogenesis | CMV | M45 |

| HIV | TAT | |||

| HSVI | gD | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | S-protein | |||

| Intracellular Tau Tangles |

cGAS-STING | CMV | pUL31* pUL83* |

|

| HIV | GAG* | |||

| HSV1 | ICP27 VP11* |

|||

| SARS-CoV-2 | S-protein | |||

| VZV | ORF9* | |||

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia |

Cytosolic TDP43 Aggregates | RNA Translocation | CV | 2A, 2C |

| Echovirus | 2A, 2C | |||

| Poliovirus | 2A, 2C | |||

| HIV | GAG VIF |

|||

| HERV-K | ASRGL1* | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | S-protein | |||

| Parkinson’s Disease and Lewy Body Dementia |

Lewy Body Aggregates |

Endoplasmic Reticulum Sequestration |

CMV | Envelope |

| EBV | ||||

| Dengue | ||||

| HIV | ||||

| JEV | ||||

| WNV | ||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | N-protein S-protein |

2.2. Viral aggregation of TDP43

2.3. Viral aggregation of α-synuclein

2.4. Viral aberration of Protein Quality Control

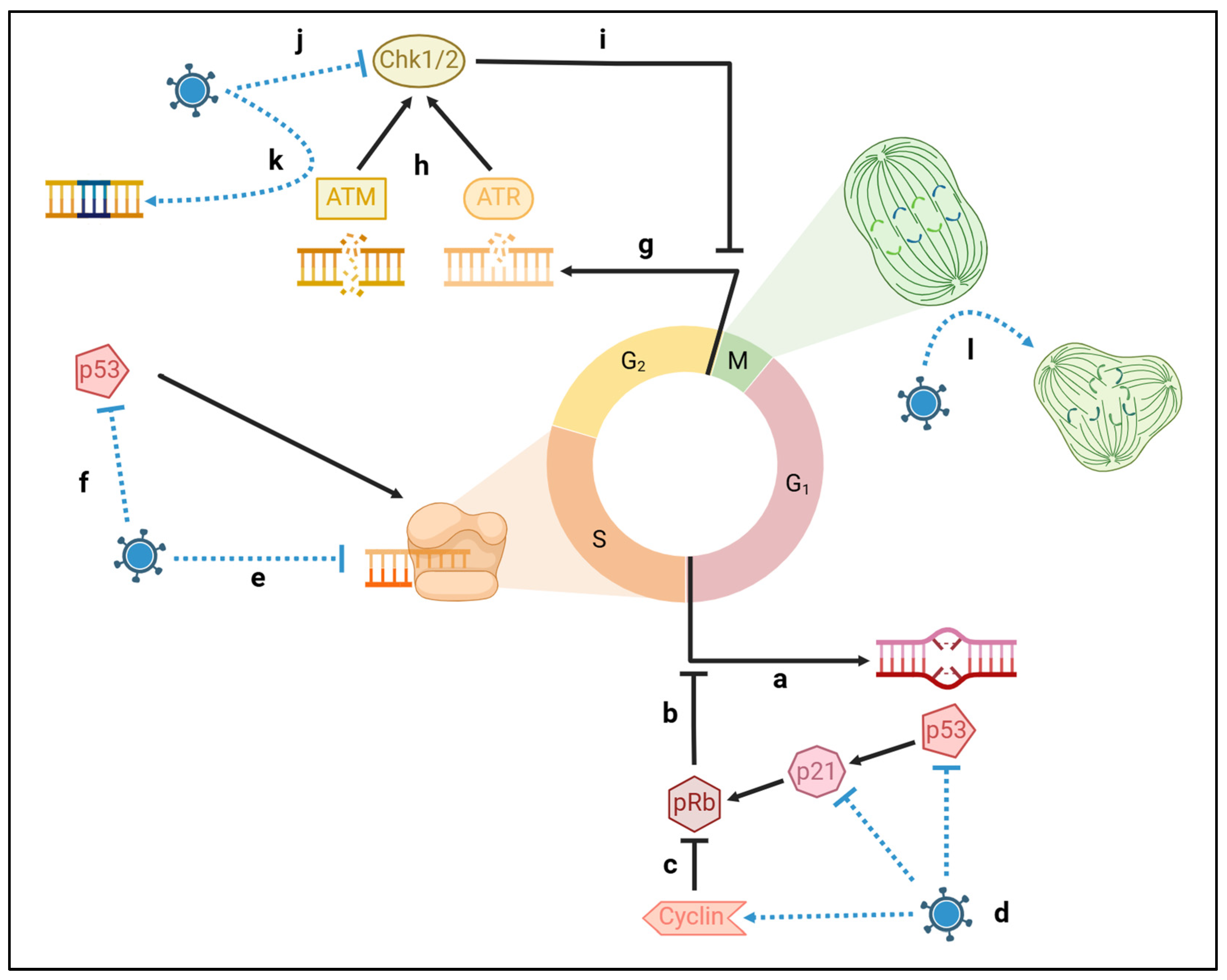

3. Genomic Compromise

3.1. Viral damage of host DNA

3.3. Viral attrition of telomeres

3.4. Viral shift of the epigenome

4. Senescence

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| PQC | Protein Quality Control |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| FTD | Frontotemporal Dementia |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| ssRNA | Single Stranded RNA |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Coronavirus |

| CV | Coxsackie Virus |

| JEV | Japanese Encephalitis Virus |

| WNV | West Nile Virus |

| dsDNA | Double Stranded DNA |

| HSV1 | Herpes Simplex Virus 1 |

| VZV | Varicella Zoster Virus (also human herpesvirus 3) |

| EBV | Epstein Barr Virus (also human herpesvirus 4) |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus (also human herpesvirus 5) |

| JCV | JC polyomavirus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| LBD | Lewy Body Dementia |

| gD/B | Glycoprotein D/B |

| TDP43 | Transactive Response DNA-binding Protein 43 |

| TAT | Transactivator of Transcription |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| STING | Synthase-stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| NFκB | Nuclear Factor ΚB |

| IRF3 | Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding Kinase 1 |

| VP | Viral Protein |

| GAG | Group-associated Antigen |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| VIF | Viral Infectivity Factor |

| HERV-K | Human Endogenous Retrovirus |

| ASRGL1 | Asparaginase And Isoaspartyl Peptidase 1 |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| EBNA | Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen |

| DDR | DNA Damage Response |

| TERT | Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase |

| DNMT | DNA Methyltransferase |

| TET | Ten-eleven Translocation Methylcytosine Dioxygenase |

| PD1 | Programmed Death Receptor 1 |

| CTLA4 | Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte-associated Protein 4 |

References

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [CrossRef]

- Levine, K.S.; Leonard, H.L.; Blauwendraat, C.; Iwaki, H.; Johnson, N.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Faghri, F.; Singleton, A.B.; Nalls, M.A. Virus Exposure and Neurodegenerative Disease Risk across National Biobanks. Neuron 2023, 111, 1086-1093.e2. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Feng, L.; Wu, B.; Xia, W.; Xie, P.; Ma, S.; Liu, H.; Meng, M.; Sun, Y. The Association between Varicella Zoster Virus and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Neurol Sci 2024, 45, 27–36. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D.M.; Smiley, B.M.; Smiley, J.A.; Khorsandian, Y.; Kelly, M.; Itzhaki, R.F.; Kaplan, D.L. Repetitive Injury Induces Phenotypes Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease by Reactivating HSV-1 in a Human Brain Tissue Model. Science Signaling 2025, 18, eado6430. [CrossRef]

- Levine, K.S.; Leonard, H.L.; Blauwendraat, C.; Iwaki, H.; Johnson, N.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Faghri, F.; Singleton, A.B.; Nalls, M.A. Virus Exposure and Neurodegenerative Disease Risk across National Biobanks. Neuron 2023, 111, 1086-1093.e2. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F.; Abondio, P.; Bruno, R.; Ceraudo, L.; Paparazzo, E.; Citrigno, L.; Luiselli, D.; Bruni, A.C.; Passarino, G.; Colao, R.; et al. Alzheimer’s Disease as a Viral Disease: Revisiting the Infectious Hypothesis. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 91, 102068. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ruan, L.; Zhu, L.; Jin, K.; Zhuge, Q.; Su, D.-M.; Zhao, Y. Impact of Aging Immune System on Neurodegeneration and Potential Immunotherapies. Prog Neurobiol 2017, 157, 2–28. [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yue, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, H.; et al. Gut Microbiota Interact With the Brain Through Systemic Chronic Inflammation: Implications on Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Aging. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 796288. [CrossRef]

- Blinkouskaya, Y.; Caçoilo, A.; Gollamudi, T.; Jalalian, S.; Weickenmeier, J. Brain Aging Mechanisms with Mechanical Manifestations. Mech Ageing Dev 2021, 200, 111575. [CrossRef]

- Andjelkovic, A.V.; Situ, M.; Citalan-Madrid, A.F.; Stamatovic, S.M.; Xiang, J.; Keep, R.F. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Normal Aging and Neurodegeneration: Mechanisms, Impact, and Treatments. Stroke 2023, 54, 661–672. [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, Z.; Tarantini, S.; Sorond, F.; Merkely, B.; Csiszar, A. Mechanisms of Vascular Aging, A Geroscience Perspective: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 931–941. [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, N.; Jung, H.S.; Bae, S.H.; Chelakkot, C.; Hong, S.; Choi, J.-S.; Yim, D.-S.; Oh, Y.-K.; Choi, Y.-L.; Shin, Y.K. Effect of HPV E6/E7 siRNA with Chemotherapeutic Agents on the Regulation of TP53/E2F Dynamic Behavior for Cell Fate Decisions. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 735–749. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, G.S. Amyloid-β and Tau: The Trigger and Bullet in Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol 2014, 71, 505–508. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kam, T.-I.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. α-Synuclein Pathology as a Target in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat Rev Neurol 2025, 21, 32–47. [CrossRef]

- Koike, Y. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Loss of TDP-43 Function to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Frontotemporal Dementia-Related Genes. Neurosci Res 2024, 208, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, K.; Pernemalm, M.; Pålsson, S.; Roberts, T.C.; Järver, P.; Dondalska, A.; Bestas, B.; Sobkowiak, M.J.; Levänen, B.; Sköld, M.; et al. The Viral Protein Corona Directs Viral Pathogenesis and Amyloid Aggregation. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2331. [CrossRef]

- Michiels, E.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential of Interactions between Human Amyloids and Viruses. Cell Mol Life Sci 2020, 78, 2485–2501. [CrossRef]

- Green, R.C.; Schneider, L.S.; Amato, D.A.; Beelen, A.P.; Wilcock, G.; Swabb, E.A.; Zavitz, K.H.; Tarenflurbil Phase 3 Study Group Effect of Tarenflurbil on Cognitive Decline and Activities of Daily Living in Patients with Mild Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 2557–2564. [CrossRef]

- Moir, R.D.; Lathe, R.; Tanzi, R.E. The Antimicrobial Protection Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2018, 14, 1602–1614. [CrossRef]

- Hammarström, P.; Nyström, S. Viruses and Amyloids - a Vicious Liaison. Prion 17, 82–104. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C.; Zhang, Q.-X.; Zhao, J.; Wei, N.-N. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations Studies on the Protective and Pathogenic Roles of the Amyloid-β Peptide between Herpesvirus Infection and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Mol Graph Model 2022, 113, 108143. [CrossRef]

- Idrees, D.; Kumar, V. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Interactions with Amyloidogenic Proteins: Potential Clues to Neurodegeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021, 554, 94–98. [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.L.; Shanmugam, N.; Strange, M.; O’Carroll, A.; Brown, J.W.; Sierecki, E.; Gambin, Y.; Steain, M.; Sunde, M. Viral M45 and Necroptosis-Associated Proteins Form Heteromeric Amyloid Assemblies. EMBO Rep 2019, 20, e46518. [CrossRef]

- Hategan, A.; Bianchet, M.A.; Steiner, J.; Karnaukhova, E.; Masliah, E.; Fields, A.; Lee, M.-H.; Dickens, A.M.; Haughey, N.; Dimitriadis, E.K.; et al. HIV Tat Protein and Amyloid-β Peptide Form Multifibrillar Structures That Cause Neurotoxicity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2017, 24, 379–386. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Hong, Y.; Pradeep Nidamanuri, N.; Yang, C.; Li, Q.; Dong, M. Identification and Nanomechanical Characterization of the HIV Tat-Amyloid β Peptide Multifibrillar Structures. Chemistry – A European Journal 2020, 26, 9449–9453. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Huang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Hong, C.; Sun, Z.; Deng, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. The cGAS-STING Pathway in Viral Infections: A Promising Link between Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Autophagy. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1352479. [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.-T.; Du, F.; Aroh, C.; Yan, N.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase Is an Innate Immune Sensor of HIV and Other Retroviruses. Science 2013, 341, 903–906. [CrossRef]

- Hyde, V.R.; Zhou, C.; Fernandez, J.R.; Chatterjee, K.; Ramakrishna, P.; Lin, A.; Fisher, G.W.; Çeliker, O.T.; Caldwell, J.; Bender, O.; et al. Anti-Herpetic Tau Preserves Neurons via the cGAS-STING-TBK1 Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Rep 2024, 115109. [CrossRef]

- Lio, C.-W.J.; McDonald, B.; Takahashi, M.; Dhanwani, R.; Sharma, N.; Huang, J.; Pham, E.; Benedict, C.A.; Sharma, S. cGAS-STING Signaling Regulates Initial Innate Control of Cytomegalovirus Infection. J Virol 2016, 90, 7789–7797. [CrossRef]

- Maelfait, J.; Bridgeman, A.; Benlahrech, A.; Cursi, C.; Rehwinkel, J. Restriction by SAMHD1 Limits cGAS/STING-Dependent Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses to HIV-1. Cell Rep 2016, 16, 1492–1501. [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhuang, M.-W.; Deng, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Nan, M.-L.; Zhang, X.-J.; Gao, C.; Wang, P.-H. SARS-CoV-2 ORF9b Antagonizes Type I and III Interferons by Targeting Multiple Components of the RIG-I/MDA-5-MAVS, TLR3-TRIF, and cGAS-STING Signaling Pathways. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 5376–5389. [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.; Ferreira, A.R.; Ribeiro, D. The Interplay between Human Cytomegalovirus and Pathogen Recognition Receptor Signaling. Viruses 2018, 10, 514. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-F.; Zou, H.-M.; Liao, B.-W.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Yang, Y.; Fu, Y.-Z.; Wang, S.-Y.; Luo, M.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y. Human Cytomegalovirus Protein UL31 Inhibits DNA Sensing of cGAS to Mediate Immune Evasion. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 69-80.e4. [CrossRef]

- Biolatti, M.; Dell’Oste, V.; Pautasso, S.; Gugliesi, F.; von Einem, J.; Krapp, C.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Borgogna, C.; Gariglio, M.; De Andrea, M.; et al. Human Cytomegalovirus Tegument Protein Pp65 (pUL83) Dampens Type I Interferon Production by Inactivating the DNA Sensor cGAS without Affecting STING. Journal of Virology 2018, 92, 10.1128/jvi.01774-17. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; You, H.; Su, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Zheng, C. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Tegument Protein VP22 Abrogates cGAS/STING-Mediated Antiviral Innate Immunity. J Virol 2018, 92, e00841-18. [CrossRef]

- Sumner, R.P.; Blest, H.; Lin, M.; Maluquer de Motes, C.; Towers, G.J. HIV-1 with Gag Processing Defects Activates cGAS Sensing. Retrovirology 2024, 21, 10. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, C.; Zhou, S.; Li, Q.; Feng, Y.; Sun, P.; Feng, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Luo, X.; et al. Viral Tegument Proteins Restrict cGAS-DNA Phase Separation to Mediate Immune Evasion. Mol Cell 2021, 81, 2823-2837.e9. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, W.; Shao, Q.; Chen, Z.; Huang, C. The Battle between the Innate Immune cGAS-STING Signaling Pathway and Human Herpesvirus Infection. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1235590. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, S.; Fernandez-Sesma, A. Collateral Damage during Dengue Virus Infection: Making Sense of DNA by cGAS. J Virol 2017, 91, e01081-16. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Montojo, M.; Fathi, S.; Rastegar, C.; Simula, E.R.; Doucet-O’Hare, T.; Cheng, Y.H.H.; Abrams, R.P.M.; Pasternack, N.; Malik, N.; Bachani, M.; et al. TDP-43 Proteinopathy in ALS Is Triggered by Loss of ASRGL1 and Associated with HML-2 Expression. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4163. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Rodríguez, R.; Pérez-Yanes, S.; Lorenzo-Sánchez, I.; Estévez-Herrera, J.; García-Luis, J.; Trujillo-González, R.; Valenzuela-Fernández, A. TDP-43 Controls HIV-1 Viral Production and Virus Infectiveness. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7658. [CrossRef]

- Fung, G.; Shi, J.; Deng, H.; Hou, J.; Wang, C.; Hong, A.; Zhang, J.; Jia, W.; Luo, H. Cytoplasmic Translocation, Aggregation, and Cleavage of TDP-43 by Enteroviral Proteases Modulate Viral Pathogenesis. Cell Death Differ 2015, 22, 2087–2097. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wei, W. Enterovirus D68 Infection Induces TDP-43 Cleavage, Aggregation, and Neurotoxicity. J Virol 2023, 97, e0042523. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.C.; Liu, H.; Mohamud, Y.; Bahreyni, A.; Zhang, J.; Cashman, N.R.; Luo, H. Sublethal Enteroviral Infection Exacerbates Disease Progression in an ALS Mouse Model. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 16. [CrossRef]

- Rahic, Z.; Buratti, E.; Cappelli, S. Reviewing the Potential Links between Viral Infections and TDP-43 Proteinopathies. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 1581. [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.S.; Patel, P.; Dutta, K.; Julien, J.-P. Inflammation Induces TDP-43 Mislocalization and Aggregation. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0140248. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.C.; Feuer, R.; Cashman, N.; Luo, H. Enteroviral Infection: The Forgotten Link to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis? Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11, 63. [CrossRef]

- Licht-Murava, A.; Meadows, S.M.; Palaguachi, F.; Song, S.C.; Bram, Y.; Zhou, C.; Jackvony, S.; Schwartz, R.E.; Froemke, R.C.; Orr, A.L.; et al. Astrocytic TDP-43 Dysregulation Impairs Memory by Modulating Antiviral Pathways and Interferon-Inducible Chemokines 2022, 2022.08.30.503668.

- Spillantini, M.G.; Crowther, R.A.; Jakes, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Goedert, M. Alpha-Synuclein in Filamentous Inclusions of Lewy Bodies from Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 6469–6473. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bohara, V.S.; Chauhan, A.S.; Mohapatra, A.; Kaur, H.; Sharma, A.; Chaudhary, N.; Kumar, S. Alpha-Synuclein Expression in Neurons Modulates Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection. Journal of Virology 2024, 98, e00418-24. [CrossRef]

- Beatman, E.L.; Massey, A.; Shives, K.D.; Burrack, K.S.; Chamanian, M.; Morrison, T.E.; Beckham, J.D. Alpha-Synuclein Expression Restricts RNA Viral Infections in the Brain. J Virol 2016, 90, 2767–2782. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, H.K.; Traverse, E.M.; Barr, K.L. Viral Parkinsonism: An Underdiagnosed Neurological Complication of Dengue Virus Infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, e0010118. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liao, Z.; Tan, H.; Wang, K.; Feng, C.; Xing, P.; Zhang, X.; Hua, J.; Jiang, P.; Peng, S.; et al. The Association between Cytomegalovirus Infection and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Prospective Cohort Using UK Biobank Data. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 74, 102757. [CrossRef]

- Semerdzhiev, S.A.; Fakhree, M.A.A.; Segers-Nolten, I.; Blum, C.; Claessens, M.M.A.E. Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 N-Protein and α-Synuclein Accelerate Amyloid Formation. ACS Chem Neurosci 2021, 13, 143–150. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Ma, K. SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Interact with Alpha Synuclein and Induce Lewy Body-like Pathology In Vitro. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3394. [CrossRef]

- Marreiros, R.; Müller-Schiffmann, A.; Trossbach, S.V.; Prikulis, I.; Hänsch, S.; Weidtkamp-Peters, S.; Moreira, A.R.; Sahu, S.; Soloviev, I.; Selvarajah, S.; et al. Disruption of Cellular Proteostasis by H1N1 Influenza A Virus Causes α-Synuclein Aggregation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 6741–6751. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, A.; Castañeda, C.A. Protein Quality Control Machinery: Regulators of Condensate Architecture and Functionality. Trends Biochem Sci 2025, S0968-0004(24)00275-5. [CrossRef]

- Almasy, K.M.; Davies, J.P.; Lisy, S.M.; Tirgar, R.; Tran, S.C.; Plate, L. Small-Molecule Endoplasmic Reticulum Proteostasis Regulator Acts as a Broad-Spectrum Inhibitor of Dengue and Zika Virus Infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2012209118. [CrossRef]

- Proulx, J.; Borgmann, K.; Park, I.-W. Role of Virally-Encoded Deubiquitinating Enzymes in Regulation of the Virus Life Cycle. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 4438. [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, E.; Medina-Guzman, R.; Bahatyrevich-Kharitonik, B.; Ruano, D. Protein Quality Control Systems and ER Stress as Key Players in SARS-CoV-2-Induced Neurodegeneration. Cells 2024, 13, 123. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; White, K.M.; O’Meara, M.J.; Rezelj, V.V.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 Protein Interaction Map Reveals Targets for Drug Repurposing. Nature 2020, 583, 459–468. [CrossRef]

- Corona, A.K.; Saulsbery, H.M.; Corona Velazquez, A.F.; Jackson, W.T. Enteroviruses Remodel Autophagic Trafficking through Regulation of Host SNARE Proteins to Promote Virus Replication and Cell Exit. Cell Rep 2018, 22, 3304–3314. [CrossRef]

- Zeltzer, S.; Zeltzer, C.A.; Igarashi, S.; Wilson, J.; Donaldson, J.G.; Goodrum, F. Virus Control of Trafficking from Sorting Endosomes. mBio 2018, 9, e00683-18. [CrossRef]

- Orzalli, M.H.; Kagan, J.C. Apoptosis and Necroptosis as Host Defense Strategies to Prevent Viral Infection. Trends Cell Biol 2017, 27, 800–809. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.P.; McCormick, C. Herpesviruses and the Unfolded Protein Response. Viruses 2020, 12, 17. [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, A.; Sariyer, I.K.; Berger, J.R. Revisiting JC Virus and Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy. J Neurovirol 2023, 29, 524–537. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Xuan, B.; Gualberto, N.; Yu, D. The Human Cytomegalovirus Protein pUL38 Suppresses Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Cell Death Independently of Its Ability To Induce mTORC1 Activation. Journal of Virology 2011, 85, 9103–9113. [CrossRef]

- Szymula, A.; Palermo, R.D.; Bayoumy, A.; Groves, I.J.; Ba Abdullah, M.; Holder, B.; White, R.E. Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen EBNA-LP Is Essential for Transforming Naïve B Cells, and Facilitates Recruitment of Transcription Factors to the Viral Genome. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1006890. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, S.; Xue, H.; He, Y. Impact of Endogenous Viral Elements on Glioma Clinical Phenotypes by Inducing OCT4 in the Host. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1474492. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, M.; Jiang, X.; He, G. Research Advances in Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA) and CMA-Based Protein Degraders. J Med Chem 2025. [CrossRef]

- Groelly, F.J.; Fawkes, M.; Dagg, R.A.; Blackford, A.N.; Tarsounas, M. Targeting DNA Damage Response Pathways in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2023, 23, 78–94. [CrossRef]

- Studstill, C.J.; Mac, M.; Moody, C.A. Interplay between the DNA Damage Response and the Life Cycle of DNA Tumor Viruses. Tumour Virus Res 2023, 16, 200272. [CrossRef]

- Wallet, C.; De Rovere, M.; Van Assche, J.; Daouad, F.; De Wit, S.; Gautier, V.; Mallon, P.W.G.; Marcello, A.; Van Lint, C.; Rohr, O.; et al. Microglial Cells: The Main HIV-1 Reservoir in the Brain. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Jennings, A.L.; Valada, A.; O’Shea, C.; Iskhakova, M.; Hu, B.; Javidfar, B.; Ben Hutta, G.; Lambert, T.Y.; Murray, J.; Kassim, B.; et al. HIV Integration in the Human Brain Is Linked to Microglial Activation and 3D Genome Remodeling. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 4647-4663.e8. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-H.; Maric, D.; Major, E.O.; Nath, A. Productive HIV Infection in Astrocytes Can Be Established via a Non-Classical Mechanism. AIDS 2020, 34, 963–978. [CrossRef]

- Maldarelli, F.; Wu, X.; Su, L.; Simonetti, F.R.; Shao, W.; Hill, S.; Spindler, J.; Ferris, A.L.; Mellors, J.W.; Kearney, M.F.; et al. Specific HIV Integration Sites Are Linked to Clonal Expansion and Persistence of Infected Cells. Science 2014, 345, 179–183. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, A.; Al-Harthi, L. HIV Infection of Non-Classical Cells in the Brain. Retrovirology 2023, 20, 1. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Li, B.; Xu, T.; Hu, R.; Tan, D.; Song, X.; Jia, P.; Zhao, Z. VISDB: A Manually Curated Database of Viral Integration Sites in the Human Genome. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48, D633–D641. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, W.-L.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yao, Y.; Xiang, T.; Feng, Q.-S.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, R.-J.; Jia, W.-H.; et al. Genome-Wide Profiling of Epstein-Barr Virus Integration by Targeted Sequencing in Epstein-Barr Virus Associated Malignancies. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1115–1124. [CrossRef]

- Janjetovic, S.; Hinke, J.; Balachandran, S.; Akyüz, N.; Behrmann, P.; Bokemeyer, C.; Dierlamm, J.; Murga Penas, E.M. Non-Random Pattern of Integration for Epstein-Barr Virus with Preference for Gene-Poor Genomic Chromosomal Regions into the Genome of Burkitt Lymphoma Cell Lines. Viruses 2022, 14, 86. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.Z.; Abbasi, A.; Kim, D.H.; Lippman, S.M.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Cleveland, D.W. Chromosomal Fragile Site Breakage by EBV-Encoded EBNA1 at Clustered Repeats. Nature 2023, 616, 504–509. [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Zimmerman, E.S.; Planelles, V.; Chen, J. Activation of the ATR Pathway by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Vpr Involves Its Direct Binding to Chromatin In Vivo. J Virol 2005, 79, 15443–15451. [CrossRef]

- González, M.E. The HIV-1 Vpr Protein: A Multifaceted Target for Therapeutic Intervention. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 126. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, U.; Tavella, S.; Martínez-Orellana, P.; Cicio, G.; Colliva, A.; Ceccon, M.; Cabrini, M.; Henriques, A.C.; Fumagalli, V.; Paldino, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Induces DNA Damage, through CHK1 Degradation and Impaired 53BP1 Recruitment, and Cellular Senescence. Nat Cell Biol 2023, 25, 550–564. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liao, G.; Nirujogi, R.S.; Pinto, S.M.; Shaw, P.G.; Huang, T.-C.; Wan, J.; Qian, J.; Gowda, H.; Wu, X.; et al. Phosphoproteomic Profiling Reveals Epstein-Barr Virus Protein Kinase Integration of DNA Damage Response and Mitotic Signaling. PLOS Pathogens 2015, 11, e1005346. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Targeting P53 Pathways: Mechanisms, Structures and Advances in Therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Shumilov, A.; Tsai, M.-H.; Schlosser, Y.T.; Kratz, A.-S.; Bernhardt, K.; Fink, S.; Mizani, T.; Lin, X.; Jauch, A.; Mautner, J.; et al. Epstein–Barr Virus Particles Induce Centrosome Amplification and Chromosomal Instability. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14257. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-E.; Kim, T.-S.; Zeng, Y.; Mikolaj, M.; Il Ahn, J.; Alam, M.S.; Monnie, C.M.; Shi, V.; Zhou, M.; Chun, T.-W.; et al. Centrosome Amplification and Aneuploidy Driven by the HIV-1-Induced Vpr•VprBP•Plk4 Complex in CD4+ T Cells. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.-C.; Xue, H.; Zhang, C.-Y. The Oncogenic Roles of JC Polyomavirus in Cancer. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 976577. [CrossRef]

- Prichard, M.N.; Sztul, E.; Daily, S.L.; Perry, A.L.; Frederick, S.L.; Gill, R.B.; Hartline, C.B.; Streblow, D.N.; Varnum, S.M.; Smith, R.D.; et al. Human Cytomegalovirus UL97 Kinase Activity Is Required for the Hyperphosphorylation of Retinoblastoma Protein and Inhibits the Formation of Nuclear Aggresomes. Journal of Virology 2008, 82, 5054–5067. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanow, B.; Phan, Q.V.; Wiebusch, L. Emerging Mechanisms of G1/S Cell Cycle Control by Human and Mouse Cytomegaloviruses. mBio 2021, 12, e02934-21. [CrossRef]

- Wiebusch, L.; Asmar, J.; Uecker, R.; Hagemeier, C. Human Cytomegalovirus Immediate-Early Protein 2 (IE2)-Mediated Activation of Cyclin E Is Cell-Cycle-Independent and Forces S-Phase Entry in IE2-Arrested Cells. J Gen Virol 2003, 84, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Cheerathodi, M.R.; Meckes, D.G. The Epstein-Barr Virus LMP1 Interactome: Biological Implications and Therapeutic Targets. Future Virol 2018, 13, 863–887. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, X.; Yan, B.; Chen, L.; Tao, Y.; Cao, Y. Epstein-Barr Virus Encoded LMP1 Regulates Cyclin D1 Promoter Activity by Nuclear EGFR and STAT3 in CNE1 Cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2013, 32, 90. [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Murakami, M.; Kumar, P.; Bajaj, B.; Sims, K.; Robertson, E.S. Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Augments Mdm2-Mediated P53 Ubiquitination and Degradation by Deubiquitinating Mdm2. J Virol 2009, 83, 4652–4669. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.K.; Jha, H.C.; El-Naccache, D.W.; Robertson, E.S. An EBV Recombinant Deleted for Residues 130-159 in EBNA3C Can Deregulate P53/Mdm2 and Cyclin D1/CDK6 Which Results in Apoptosis and Reduced Cell Proliferation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 18116–18134. [CrossRef]

- Rossiello, F.; Jurk, D.; Passos, J.F.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Telomere Dysfunction in Ageing and Age-Related Diseases. Nat Cell Biol 2022, 24, 135–147. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Tutton, S.; Lieberman, P.M. The Telomeric Response to Viral Infection. Viruses 2017, 9, 218. [CrossRef]

- Nassour, J.; Przetocka, S.; Karlseder, J. Telomeres as Hotspots for Innate Immunity and Inflammation. DNA Repair (Amst) 2024, 133, 103591. [CrossRef]

- Montano, M.; Oursler, K.K.; Xu, K.; Sun, Y.V.; Marconi, V.C. Biological Ageing with HIV Infection: Evaluating the Geroscience Hypothesis. The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2022, 3, e194–e205. [CrossRef]

- Dowd, J.B.; Bosch, J.A.; Steptoe, A.; Jayabalasingham, B.; Lin, J.; Yolken, R.; Aiello, A.E. Persistent Herpesvirus Infections and Telomere Attrition Over 3 Years in the Whitehall II Cohort. J Infect Dis 2017, 216, 565–572. [CrossRef]

- Noppert, G.A.; Feinstein, L.; Dowd, J.B.; Stebbins, R.C.; Zang, E.; Needham, B.L.; Meier, H.C.S.; Simanek, A.; Aiello, A.E. Pathogen Burden and Leukocyte Telomere Length in the United States. Immun Ageing 2020, 17, 36. [CrossRef]

- Virseda-Berdices, A.; Behar-Lagares, R.; Martínez-González, O.; Blancas, R.; Bueno-Bustos, S.; Brochado-Kith, O.; Manteiga, E.; Mallol Poyato, M.J.; López Matamala, B.; Martín Parra, C.; et al. Longer ICU Stay and Invasive Mechanical Ventilation Accelerate Telomere Shortening in COVID-19 Patients 1 Year after Recovery. Crit Care 2024, 28, 267. [CrossRef]

- de Lange, T. A Loopy View of Telomere Evolution. Front Genet 2015, 6, 321. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N. Infection-Induced Epigenetic Changes and Their Impact on the Pathogenesis of Diseases. Semin Immunopathol 2020, 42, 127–130. [CrossRef]

- Silmon de Monerri, N.C.; Kim, K. Pathogens Hijack the Epigenome: A New Twist on Host-Pathogen Interactions. The American Journal of Pathology 2014, 184, 897–911. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Robertson, E.S. The Crosstalk of Epigenetics and Metabolism in Herpesvirus Infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 1377. [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, L.; Lenart, A.; Tan, Q.; Vaupel, J.W.; Aviv, A.; McGue, M.; Christensen, K. DNA Methylation Age Is Associated with Mortality in a Longitudinal Danish Twin Study. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 149–154. [CrossRef]

- Bose, D.; Robertson, E.S. Chapter 108 - Viruses, Cell Transformation, and Cancer. In Molecular Medical Microbiology (Third Edition); Tang, Y.-W., Hindiyeh, M.Y., Liu, D., Sails, A., Spearman, P., Zhang, J.-R., Eds.; Academic Press, 2024; pp. 2209–2225 ISBN 978-0-12-818619-0.

- Chen, M.; Lejeune, S.; Zhou, X.; Nadeau, K. Chapter 5 - Basic Genetics and Epigenetics for the Immunologist and Allergist. In Allergic and Immunologic Diseases; Chang, C., Ed.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 119–143 ISBN 978-0-323-95061-9.

- Rowles, D.L.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Greco, T.M.; Lin, A.E.; Li, M.; Yeh, J.; Cristea, I.M. DNA Methyltransferase DNMT3A Associates with Viral Proteins and Impacts HSV-1 Infection. PROTEOMICS 2015, 15, 1968–1982. [CrossRef]

- Paschos, K.; Smith, P.; Anderton, E.; Middeldorp, J.M.; White, R.E.; Allday, M.J. Epstein-Barr Virus Latency in B Cells Leads to Epigenetic Repression and CpG Methylation of the Tumour Suppressor Gene Bim. PLOS Pathogens 2009, 5, e1000492. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xie, L.; Shi, F.; Tang, M.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, L.; Yu, X.; Luo, X.; et al. Targeting the Signaling in Epstein–Barr Virus-Associated Diseases: Mechanism, Regulation, and Clinical Study. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Leong, M.M.L.; Lung, M.L. The Impact of Epstein-Barr Virus Infection on Epigenetic Regulation of Host Cell Gene Expression in Epithelial and Lymphocytic Malignancies. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 629780. [CrossRef]

- Nehme, Z.; Pasquereau, S.; Herbein, G. Control of Viral Infections by Epigenetic-Targeted Therapy. Clinical Epigenetics 2019, 11, 55. [CrossRef]

- Kananen, L.; Nevalainen, T.; Jylhävä, J.; Marttila, S.; Hervonen, A.; Jylhä, M.; Hurme, M. Cytomegalovirus Infection Accelerates Epigenetic Aging. Exp Gerontol 2015, 72, 227–229. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, R. Acute Enterovirus Infections Significantly Alter Host Cellular DNA Methylation Status. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 80, 104190. [CrossRef]

- Kuss-Duerkop, S.K.; Westrich, J.A.; Pyeon, D. DNA Tumor Virus Regulation of Host DNA Methylation and Its Implications for Immune Evasion and Oncogenesis. Viruses 2018, 10, 82. [CrossRef]

- Balnis, J.; Madrid, A.; Hogan, K.J.; Drake, L.A.; Adhikari, A.; Vancavage, R.; Singer, H.A.; Alisch, R.S.; Jaitovich, A. Persistent Blood DNA Methylation Changes One Year after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Clin Epigenetics 2022, 14, 94. [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Cantos, A.; Rodríguez-Centeno, J.; Silla, J.C.; Barruz, P.; Sánchez-Cabo, F.; Saiz-Medrano, G.; Nevado, J.; Mena-Garay, B.; Jiménez-González, M.; Miguel, R. de; et al. Effect of HIV Infection and Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation on Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Patterns. eBioMedicine 2023, 88. [CrossRef]

- Colpitts, T.M.; Barthel, S.; Wang, P.; Fikrig, E. Dengue Virus Capsid Protein Binds Core Histones and Inhibits Nucleosome Formation in Human Liver Cells. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24365. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Vogel, J.L.; Narayanan, A.; Peng, H.; Kristie, T.M. Inhibition of the Histone Demethylase LSD1 Blocks Alpha-Herpesvirus Lytic Replication and Reactivation from Latency. Nat Med 2009, 15, 1312–1317. [CrossRef]

- Ambagala, A.P.; Bosma, T.; Ali, M.A.; Poustovoitov, M.; Chen, J.J.; Gershon, M.D.; Adams, P.D.; Cohen, J.I. Varicella-Zoster Virus Immediate-Early 63 Protein Interacts with Human Antisilencing Function 1 Protein and Alters Its Ability to Bind Histones H3.1 and H3.3. J Virol 2009, 83, 200–209. [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.S.; Lan, K.; Subramanian, C.; Robertson, E.S. Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Recruits Histone Deacetylase Activity and Associates with the Corepressors mSin3A and NCoR in Human B-Cell Lines. J Virol 2003, 77, 4261–4272. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-J.; Kim, Y.-E.; Pham, H.T.; Kim, E.T.; Chung, Y.-H.; Ahn, J.-H. Functional Interaction of the Human Cytomegalovirus IE2 Protein with Histone Deacetylase 2 in Infected Human Fibroblasts. J Gen Virol 2007, 88, 3214–3223. [CrossRef]

- Hackett, B.A.; Dittmar, M.; Segrist, E.; Pittenger, N.; To, J.; Griesman, T.; Gordesky-Gold, B.; Schultz, D.C.; Cherry, S. Sirtuin Inhibitors Are Broadly Antiviral against Arboviruses. mBio 2019, 10, 10.1128/mbio.01446-19. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; Nehme, J.; Demaria, M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends Cell Biol 2018, 28, 436–453. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, F.G.; Wikby, A.; Maxson, P.; Olsson, J.; Johansson, B. Immune Parameters in a Longitudinal Study of a Very Old Population of Swedish People: A Comparison between Survivors and Nonsurvivors. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995, 50, B378-382. [CrossRef]

- Hadrup, S.R.; Strindhall, J.; Køllgaard, T.; Seremet, T.; Johansson, B.; Pawelec, G.; thor Straten, P.; Wikby, A. Longitudinal Studies of Clonally Expanded CD8 T Cells Reveal a Repertoire Shrinkage Predicting Mortality and an Increased Number of Dysfunctional Cytomegalovirus-Specific T Cells in the Very Elderly. J Immunol 2006, 176, 2645–2653. [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Pera, A.; Sanchez-Correa, B.; Alonso, C.; Lopez-Fernandez, I.; Morgado, S.; Tarazona, R.; Solana, R. Effect of Age and CMV on NK Cell Subpopulations. Exp Gerontol 2014, 54, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Pita-Lopez, M.L.; Gayoso, I.; DelaRosa, O.; Casado, J.G.; Alonso, C.; Muñoz-Gomariz, E.; Tarazona, R.; Solana, R. Effect of Ageing on CMV-Specific CD8 T Cells from CMV Seropositive Healthy Donors. Immunity & Ageing 2009, 6, 11. [CrossRef]

- Wertheimer, A.M.; Bennett, M.S.; Park, B.; Uhrlaub, J.L.; Martinez, C.; Pulko, V.; Currier, N.L.; Nikolich-Žugich, D.; Kaye, J.; Nikolich-Žugich, J. Aging and Cytomegalovirus Infection Differentially and Jointly Affect Distinct Circulating T Cell Subsets in Humans. J Immunol 2014, 192, 2143–2155. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Shariff, N.; Cobbold, M.; Bruton, R.; Ainsworth, J.A.; Sinclair, A.J.; Nayak, L.; Moss, P.A.H. Cytomegalovirus Seropositivity Drives the CD8 T Cell Repertoire Toward Greater Clonality in Healthy Elderly Individuals1. The Journal of Immunology 2002, 169, 1984–1992. [CrossRef]

- Attaf, M.; Malik, A.; Severinsen, M.C.; Roider, J.; Ogongo, P.; Buus, S.; Ndung’u, T.; Leslie, A.; Kløverpris, H.N.; Matthews, P.C.; et al. Major TCR Repertoire Perturbation by Immunodominant HLA-B*44:03-Restricted CMV-Specific T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, F.; Clave, E.; Wanke, K.; von Braun, A.; Bondet, V.; Alanio, C.; Douay, C.; Baque, M.; Lependu, C.; Marconi, P.; et al. Primary Immune Responses Are Negatively Impacted by Persistent Herpesvirus Infections in Older People: Results from an Observational Study on Healthy Subjects and a Vaccination Trial on Subjects Aged More than 70 Years Old. eBioMedicine 2022, 76, 103852. [CrossRef]

- Lanfermeijer, J.; de Greef, P.C.; Hendriks, M.; Vos, M.; van Beek, J.; Borghans, J.A.M.; van Baarle, D. Age and CMV-Infection Jointly Affect the EBV-Specific CD8+ T-Cell Repertoire. Front. Aging 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.M.; McSharry, B.P.; Steain, M.; Ashhurst, T.M.; Slobedman, B.; Abendroth, A. Varicella Zoster Virus Productively Infects Human Natural Killer Cells and Manipulates Phenotype. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1006999. [CrossRef]

- Gerada, C.; Campbell, T.M.; Kennedy, J.J.; McSharry, B.P.; Steain, M.; Slobedman, B.; Abendroth, A. Manipulation of the Innate Immune Response by Varicella Zoster Virus. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.J. Immune Senescence and Vaccines to Prevent Herpes Zoster in Older Persons. Current Opinion in Immunology 2012, 24, 494–500. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Bientinesi, E.; Monti, D. Immunosenescence and Inflammaging in the Aging Process: Age-Related Diseases or Longevity? Ageing Res Rev 2021, 71, 101422. [CrossRef]

- Ghamar Talepoor, A.; Doroudchi, M. Immunosenescence in Atherosclerosis: A Role for Chronic Viral Infections. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 945016. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, E.; Morales-Pison, S.; Urbina, F.; Solari, A. Aging Hallmarks and the Role of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 651. [CrossRef]

- Bellon, M.; Nicot, C. Telomere Dynamics in Immune Senescence and Exhaustion Triggered by Chronic Viral Infection. Viruses 2017, 9, 289. [CrossRef]

- Derhovanessian, E.; Maier, A.B.; Hähnel, K.; Zelba, H.; de Craen, A.J.M.; Roelofs, H.; Slagboom, E.P.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; Pawelec, G. Lower Proportion of Naïve Peripheral CD8+ T Cells and an Unopposed Pro-Inflammatory Response to Human Cytomegalovirus Proteins in Vitro Are Associated with Longer Survival in Very Elderly People. Age (Dordr) 2013, 35, 1387–1399. [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, G.; McElhaney, J.E.; Aiello, A.E.; Derhovanessian, E. The Impact of CMV Infection on Survival in Older Humans. Curr Opin Immunol 2012, 24, 507–511. [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, G.; Goldeck, D.; Derhovanessian, E. Inflammation, Ageing and Chronic Disease. Curr Opin Immunol 2014, 29, 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Smithey, M.J.; Li, G.; Venturi, V.; Davenport, M.P.; Nikolich-Žugich, J. Lifelong Persistent Viral Infection Alters the Naive T Cell Pool, Impairing CD8 T Cell Immunity in Late Life. J Immunol 2012, 189, 5356–5366. [CrossRef]

- Serriari, N.-E.; Gondois-Rey, F.; Guillaume, Y.; Remmerswaal, E.B.M.; Pastor, S.; Messal, N.; Truneh, A.; Hirsch, I.; van Lier, R.A.W.; Olive, D. B and T Lymphocyte Attenuator Is Highly Expressed on CMV-Specific T Cells during Infection and Regulates Their Function. J Immunol 2010, 185, 3140–3148. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Vergès, S.; Milush, J.M.; Pandey, S.; York, V.A.; Arakawa-Hoyt, J.; Pircher, H.; Norris, P.J.; Nixon, D.F.; Lanier, L.L. CD57 Defines a Functionally Distinct Population of Mature NK Cells in the Human CD56dimCD16+ NK-Cell Subset. Blood 2010, 116, 3865–3874. [CrossRef]

- Effros, R.B.; Boucher, N.; Porter, V.; Zhu, X.; Spaulding, C.; Walford, R.L.; Kronenberg, M.; Cohen, D.; Schächter, F. Decline in CD28+ T Cells in Centenarians and in Long-Term T Cell Cultures: A Possible Cause for Both in Vivo and in Vitro Immunosenescence. Exp Gerontol 1994, 29, 601–609. [CrossRef]

- J Heath, J.; D Grant, M. The Immune Response Against Human Cytomegalovirus Links Cellular to Systemic Senescence. Cells 2020, 9, 766. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M.; Yang, P.-S.; Jin, M.-N.; Yu, H.T.; Kim, T.-H.; Jang, E.; Uhm, J.-S.; Pak, H.-N.; Lee, M.-H.; Joung, B. Association of Physical Activity Level With Risk of Dementia in a Nationwide Cohort in Korea. JAMA Network Open 2021, 4, e2138526. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, H.; Liu, X.; Sun, W. Modifiable Lifestyle Factors Influencing Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders Mediated by Structural Brain Reserve: An Observational and Mendelian Randomization Study. J Affect Disord 2025, 372, 440–450. [CrossRef]

| Target | Virus | Protein | Mechanism |

| ATM/ATR | EBV | EBNA3c | Evasion of ATM via p53 degradation |

| LMP1 | Transcriptional downregulation of ATM | ||

| HIV | VPR | Chromatin binding activates ATR | |

| Chk1/2 | EBV | EBNA3a | Inactivation by direct binding |

| HIV | VPR | Inactivation by phosphorylation | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | ORF6 NSP13 |

Proteolysis Autophagy-mediated degradation |

|

| p53 | EBV | EBNA3c | Ubiquitin-directed degradation |

| JCV | LTAg | Inactivation by direct binding | |

| pRb | CMV | IE2 | Inactivating phosphorylation via Cyclin-E1 |

| pp71 | Ubiquitin-directed degradation | ||

| pUL97 | Inactivation by phosphorylation | ||

| EBV | EBNA3 | Inactivation by direct binding Inactivating phosphorylation via Cyclin-D1 |

|

| LMP1 | Inactivating phosphorylation via Cyclin-D1 | ||

| JCV | LTAg | Inactivation by direct binding |

| Virus | Immune Changes | Citation |

| CMV | Decrease in percentage of CD16- NK cells | [130] |

| Decrease in percentage of CD16+/CD56bright NK cells | ||

| Increased CD16+/CD56- subset | [131] | |

| Increased CD8+ T-cells with high CD244 expression | [132] | |

| Increased CD4+ and CD8+ effector memory cells | ||

| Exhaustion of peripheral T-cell compartments | ||

| Accumulation of terminally differentiated, apoptosis-resistant, CMV-specific CD8+ lymphocytes |

[133,134] | |

| Reduced diversity of TCR repertoire | [135] | |

| EBV | Increase in differentiated phenotype markers (i.e., KLRG1) | [136] |

| Increase in terminally differentiated T-cells | ||

| Reduced diversity of TCR repertoire | ||

| VZV | Increased population of CD57+, terminally differentiated NK cells | [137] |

| Impaired Type I IFN pathway | [138] | |

| Impaired production of pro-inflammatory cytokines | ||

| Reduced frequency of VZV-specific memory T cells | [139] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).