1. Introduction

In recent years, mobile robots have become essential across various industries and are increasingly integrated into our daily life [

1,

2,

3]. As these robots take on more complex tasks, their ability to navigate and understand their surroundings becomes crucial [

1,

2]. SLAM is a fundamental technique in robotics and autonomous systems, enabling them to construct a map of an unknown environment while simultaneously determining their own position within it [

4,

5]. SLAM achieves this by processing sensor data from cameras, LiDAR, or sonar, combined with advanced algorithms such as Kalman filters, particle filters, and graph-based optimization [

6,

7]. It is widely used in applications like mobile robots, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and self-driving cars [

6,

7,

8].

As research in SLAM advances, improving its efficiency and accuracy remains a key focus to enhance autonomous navigation in real-world scenarios [

9]. A major challenge is balancing high accuracy with computational efficiency, especially in environments with dynamic obstacles, low-feature areas, or changing lighting conditions [

7]. SLAM methods must balance precision and real-time processing, particularly in environments with dynamic obstacles, low-feature regions, or variable lighting conditions [

10]. SLAM methods are generally divided into two categories:

feature-based methods [

11] and

direct-based methods [

12]. Feature-based approaches, such as ORB-SLAM [

13] and PTAM (Parallel Tracking and Mapping) [

14], rely on detecting and tracking key points across frames, which can be computationally demanding in texture-less environments. Direct methods, like LSD-SLAM [

15] and DSO [

16], operate on raw image intensities, making them more sensitive to lighting changes and motion blur.

Many SLAM methods rely on high-precision sensors, such as 3D LiDAR, which provide detailed spatial data but are expensive and computationally intensive [

17,

18]. Vision-based SLAM, using RGB or RGB-D cameras, offers a more affordable solution but faces challenges, especially in dynamic environments and feature-poor areas [

5,

19]. Additionally, relying on a single sensor type limits performance in complex environments, as each sensor has its own limitations, such as poor accuracy in low-light conditions or difficulty in capturing fine details in featureless areas [

20]. To overcome these challenges, SLAM methods need to integrate multiple sensor modalities to improve robustness and accuracy [

21].

One solution to these challenges is the use of hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of different sensors [

22,

23]. Multi-sensor SLAM, which integrates sensors like LiDARs and RGB-D cameras, has gained significant attention in recent years [

24]. By fusing the spatial precision of LiDAR with the rich visual context provided by RGB-D cameras, these approaches can handle dynamic and feature-sparse environments more effectively [

20]. This fusion approach leverages data from various sensors and employs information fusion algorithms to improve pose estimation, trajectory estimation, and mapping, giving robots enhanced environmental awareness and better navigation in complex scenarios [

24,

25]. To further reduce computational complexity, RGB-D camera data can be converted into 2D laser scans by projecting 3D point clouds, making it possible to achieve real-time navigation in resource-constrained environments [

22,

26]. Furthermore, traditional SLAM algorithms like Gmapping, rely on particle filters. It can be enhanced by improving the way of dealing with these particles in combining with information got from sensors which can achieve better performance [

24,

27].

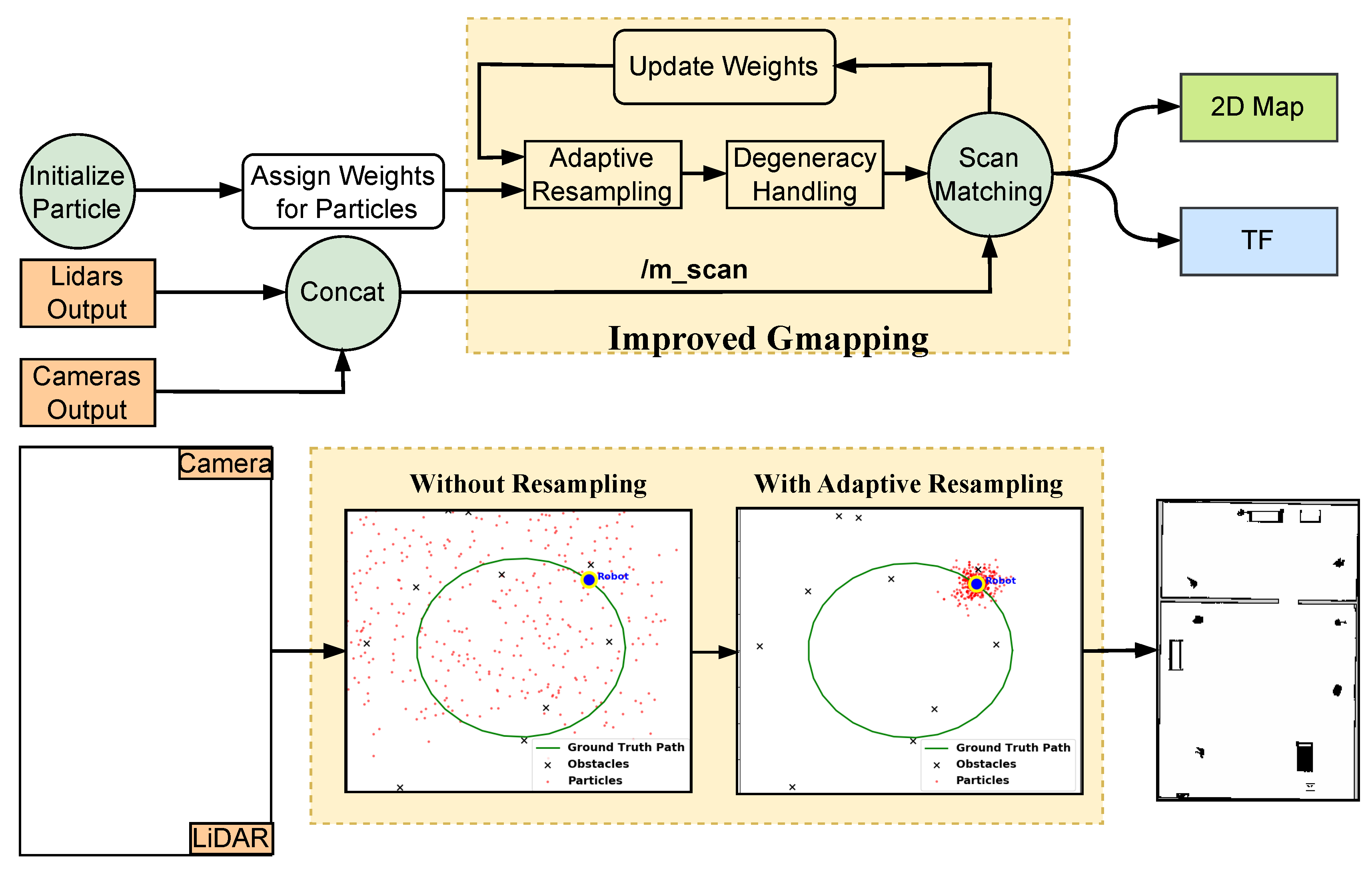

In summary, the contributions of our work can be listed as follows:

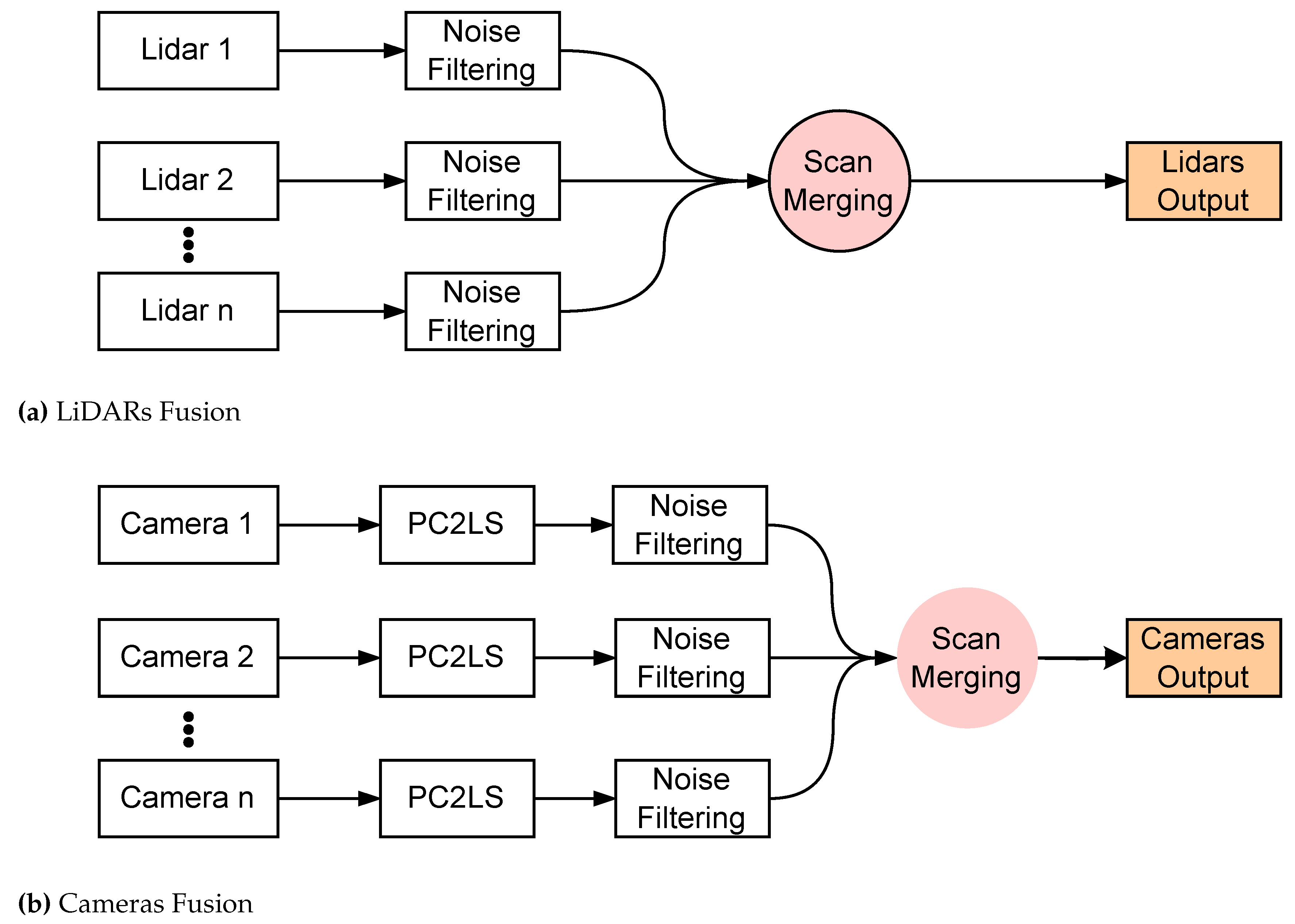

Point Cloud Projection Broadcasting: We implemented a system for projecting RGB-D camera point clouds as 2D laser scans. This involves preparing the data for seamless integration with other sensors by utilizing transformation matrices and leveraging existing ROS packages, see Figure 3b.

Modular Multi-Sensor Fusion with Noise Filtering: The system incorporates multiple sensors in parallel with early fusion, designed for adaptability and modularity. If one sensor fails, the system can continue functioning. Additionally, a noise filtering block is added after each sensor to improve data quality and reliability. See Figure 3a,b.

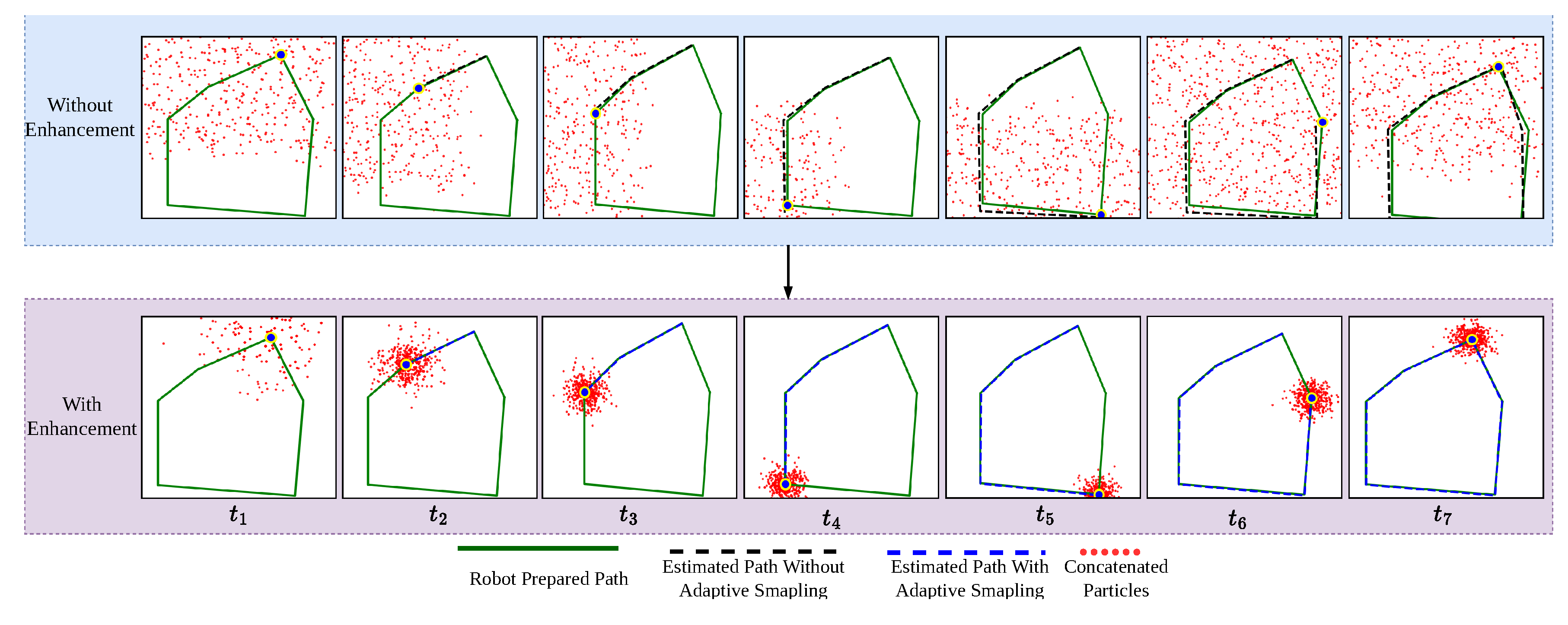

Enhanced Gmapping with Adaptive Resampling and Degeneracy Handling: The Gmapping method is enhanced by integrating adaptive resampling in combination with degeneracy handling. This selective resampling is triggered only when necessary, preserving particle diversity and improving mapping accuracy. By maintaining a balanced particle distribution, the system ensures robust localization, reduces computational overhead, and prevents particle collapse. This results in improved mapping accuracy and computational efficiency, see Figure 2.

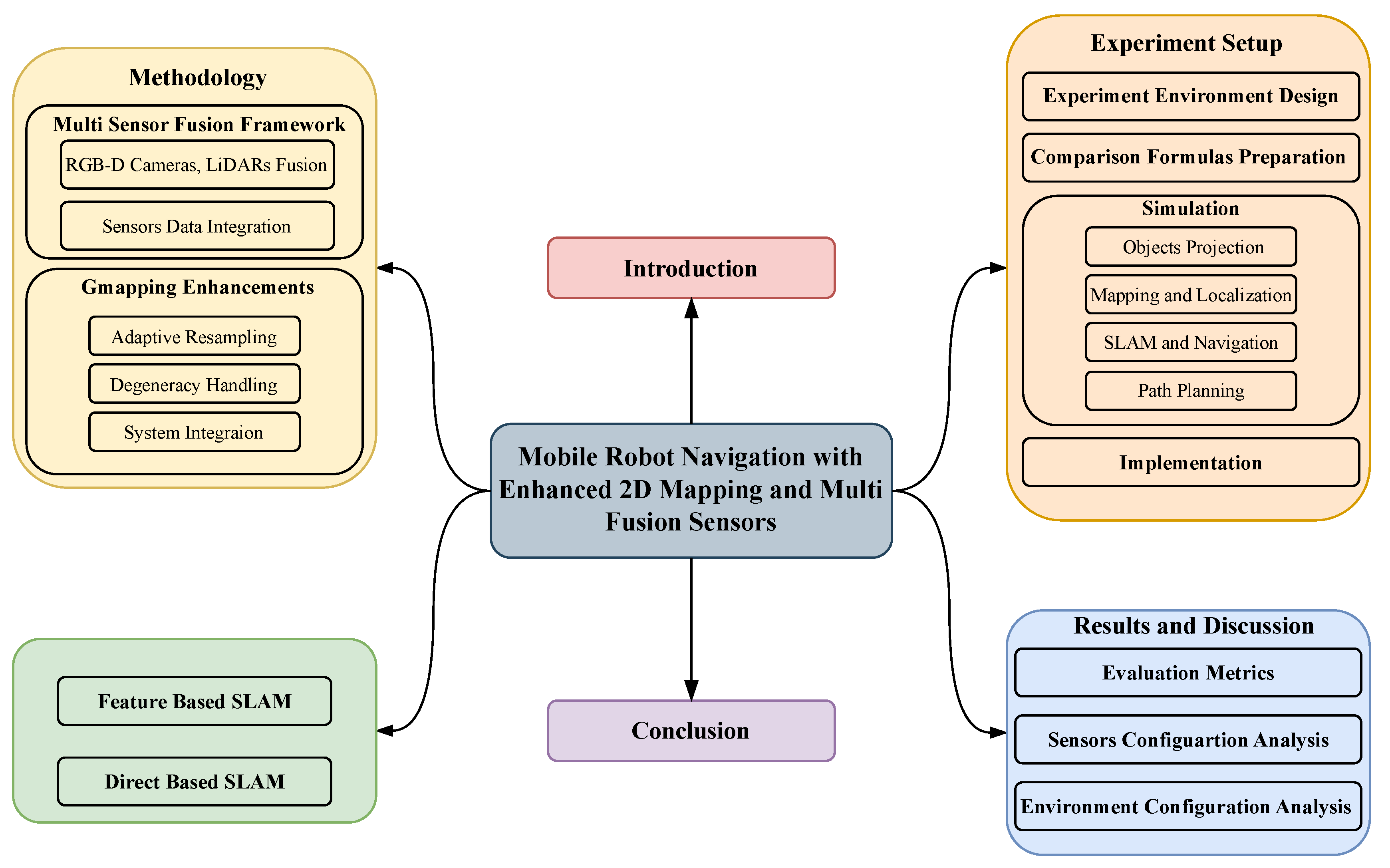

The rest of the paper is organized as shown in

Figure 1, the paper is divided into six main sections.

Section 1 provides an introduction to 2D mapping, outlining its challenges and proposed solutions.

Section 2 reviews related work, offering a detailed analysis of existing methodologies and their limitations.

Section 3 explains the methodology, covering data acquisition, point cloud processing, sensor vision integration, and data broadcasting.

Section 4 focuses on the experiments, describing the simulation environment, object projection, performance evaluation metrics, and real-world implementation in a small-scale area.

Section 5 discusses the results, examining sensor configurations, environmental setups, and system performance while highlighting their practical implications. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the key contributions, insights, and potential avenues for future research.

Figure 1.

Paper Organizational Chart.

Figure 1.

Paper Organizational Chart.

Figure 2.

The process of combining LiDAR and camera outputs, as shown in Figure 3a,b, to generate a 2D map. This process includes preparing the m_scan topic from sensor fusion, initializing the particles and assigning them weights, performing scan matching between sensors and particles to update the weights, and refining the estimation. Additionally, adaptive resampling is applied, and degeneracy is handled within the mapping algorithm. The final output is a 2D map, transformation tf.

Figure 2.

The process of combining LiDAR and camera outputs, as shown in Figure 3a,b, to generate a 2D map. This process includes preparing the m_scan topic from sensor fusion, initializing the particles and assigning them weights, performing scan matching between sensors and particles to update the weights, and refining the estimation. Additionally, adaptive resampling is applied, and degeneracy is handled within the mapping algorithm. The final output is a 2D map, transformation tf.

Figure 3.

Fusion of LiDAR and camera data, including noise filtering and converting camera point clouds to laser scans (PC2LS), preparing the data for robot navigation.

Figure 3.

Fusion of LiDAR and camera data, including noise filtering and converting camera point clouds to laser scans (PC2LS), preparing the data for robot navigation.

4. Experiment Setup

The proposed SLAM system was evaluated using the Tiago Robot. The setup featured front and back LiDAR sensors and cameras at four positions (front, back, left, and right), providing 360-degree coverage. This configuration enabled the robot to detect obstacles, navigate effectively, and interact with its surroundings.

4.1. Experiment Environment Design

The experiments were conducted in three different environments, each with increasing levels of difficulty: simple, moderate, and complex. These environments were designed in Gazebo to closely resemble real-world conditions, including both fixed and moving obstacles such as tables, chairs, and humans. The purpose of these tests was to evaluate how well the robot could navigate, avoid obstacles, and complete its tasks efficiently.

Simple Environment: This setup has only a few obstacles, such as tables, keyboards, and sofas. The paths are wide and clear, making navigation easy for the robot. It provides a basic test of movement without major challenges.

Moderate Environment: This setup adds more obstacles, like lamp holders and standing humans, to make navigation harder. The paths are narrower, requiring the robot to move carefully and adjust its route when needed. This helps test how well the robot can handle slightly more difficult spaces.

Complex Environment: This setup is the most challenging. More obstacles are placed while the robot is moving, and the paths are made even narrower. This forces the robot to make precise movements and smart decisions to avoid collisions. It tests how well the robot adapts to unpredictable situations.

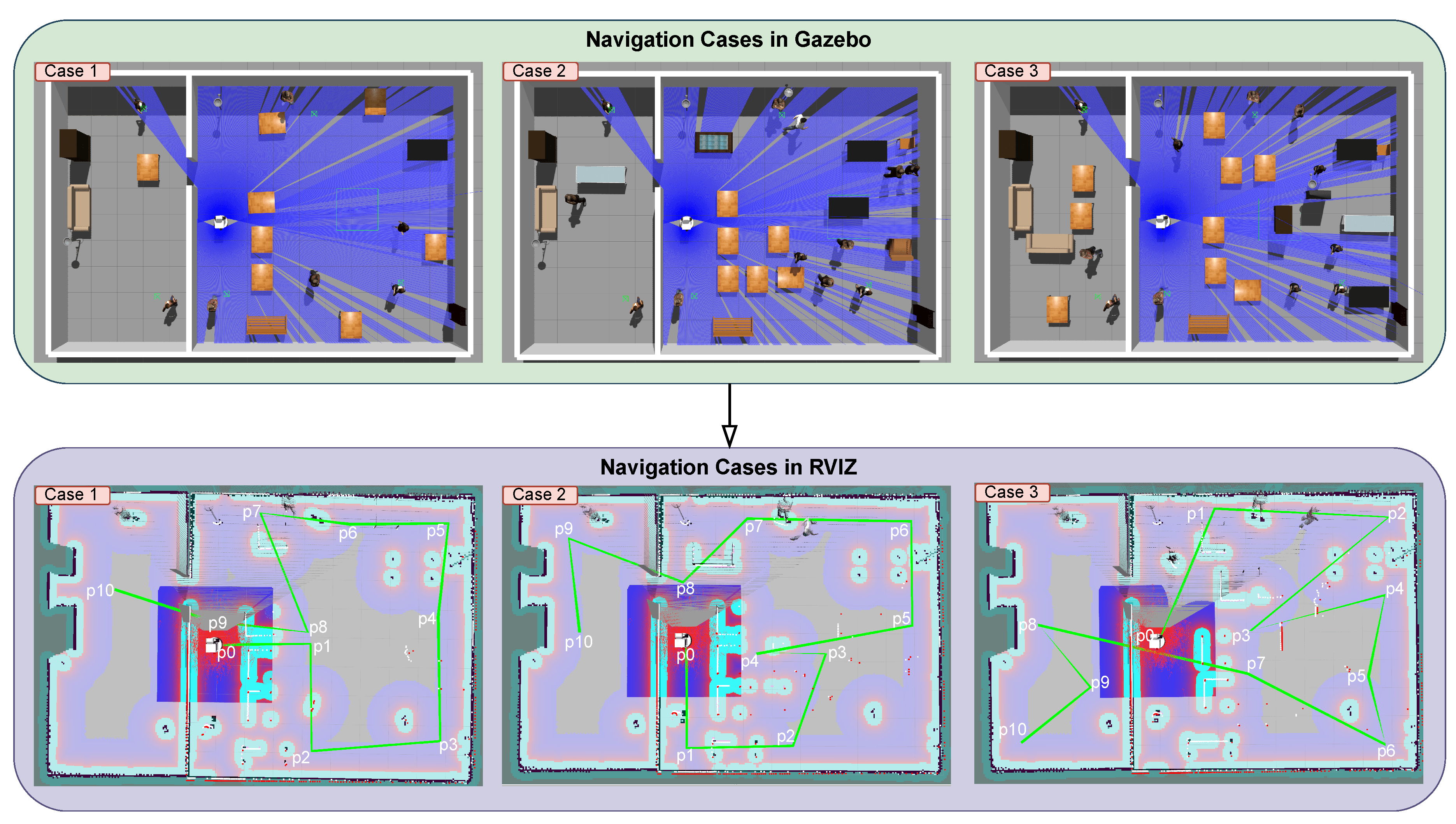

Each environment is shown in Figure 7, which illustrates the planned navigation paths and challenges. The navigation system was implemented using a Python script that processed data from /next_goal and move_base topics. The robot’s movement between waypoints was controlled using the cmd_vel topic. These topics are generally generated in ROS navigation system.

4.2. Comparison Formulas Preparation

For simulation comparison, we assess the path coverage distance, time, battery efficiency, and CPU capabilities of the robot. The robot gathers odometry data from /mobile_base_controller/odom topic. To calculate the time interval between measurements, we subtract the previous timestamp from the current timestamp , resulting in . The linear velocity v is obtained from the absolute value of the x-component of the velocity reported in the odometry data. The incremental distance is then computed as . The total distance is the sum of all incremental distances. The robot’s ability to reach the next goal is assessed by measuring its success in arriving at predetermined positions. The overall journey success rate is calculated based on the accumulated number of successfully reached points.

For battery efficiency, we assume that the battery decreases by 0.01 units per distance step. The drop in battery percentage is calculated as and the drop in voltage is .

Finally, the results have been tabulated in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

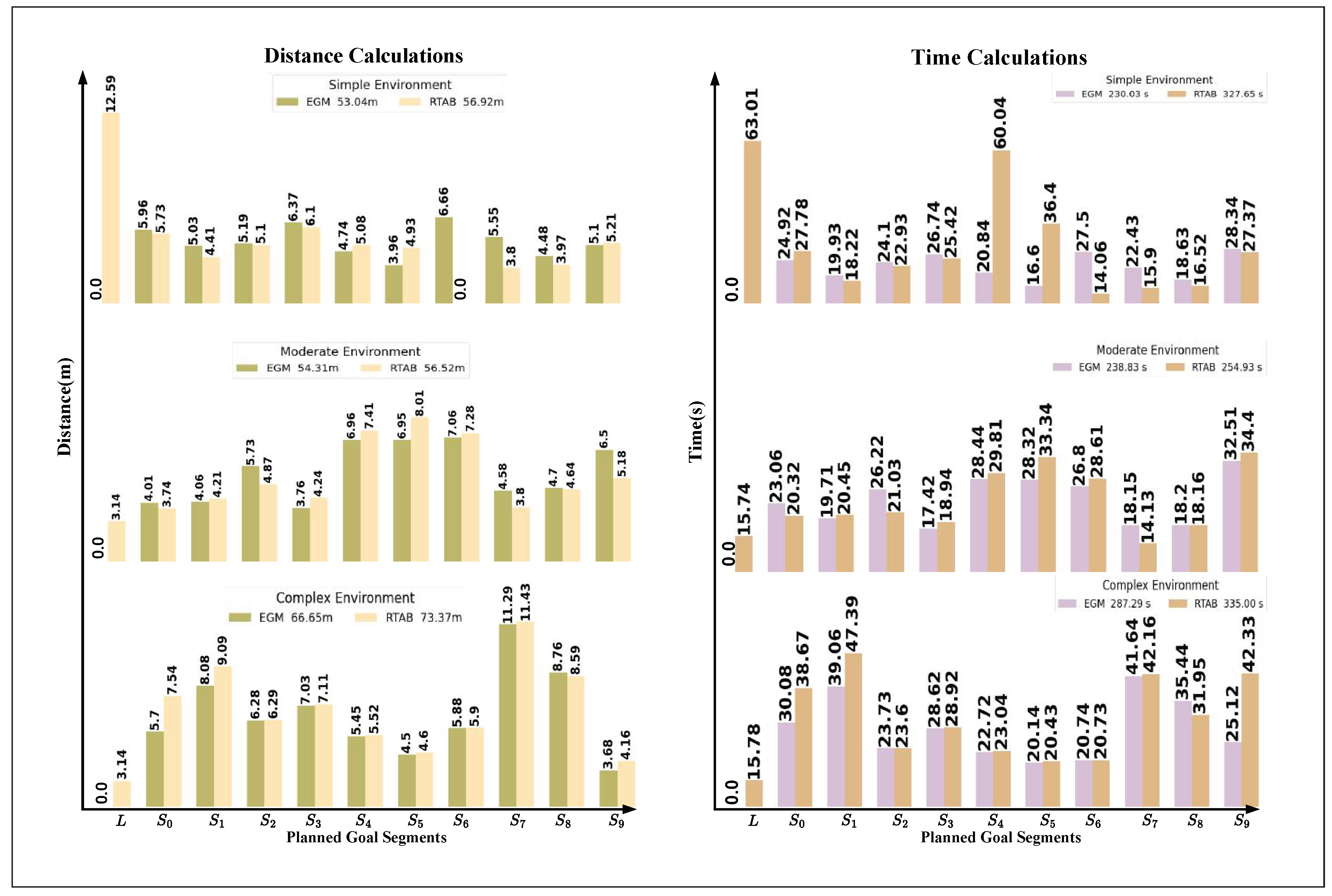

Table 4. Additionally, they have been shown in Figure 9 and

Figure 11 to be more understandable and clear for comparison needed.

4.3. Simulation

We used simulations to test our method and ensure it works well in real-world applications. The simulations were conducted in Gazebo, a robot simulation environment, while Rviz was used for visualization. We tested our method in different scenarios to evaluate its ability to map and locate objects. Additionally, we compared it with another SLAM methods such as RTAB-Map.

4.3.1. Rviz and Gazebo Objects Projection

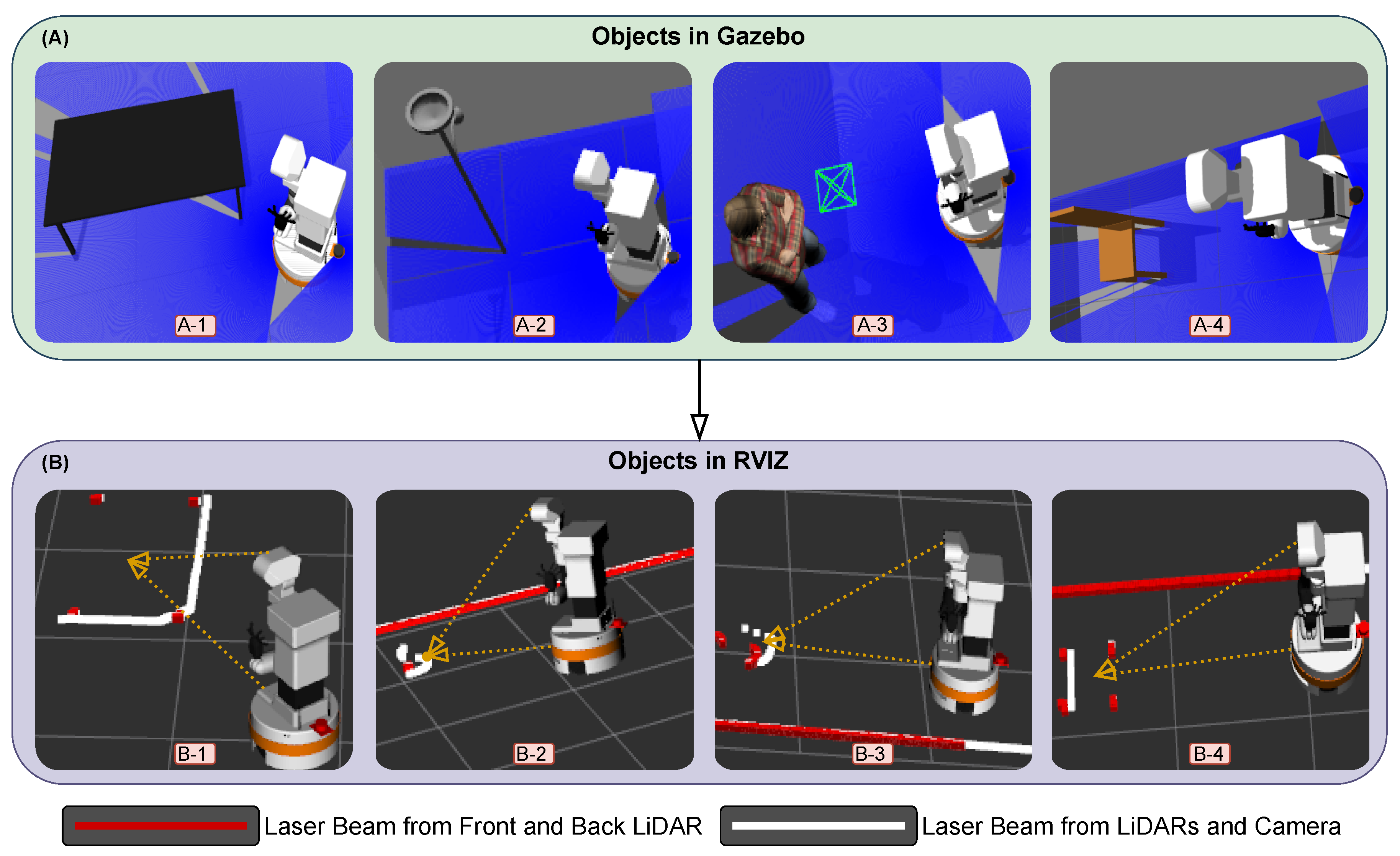

To show the effectiveness of the fusion of the sensors that we did before which is shown in Figure 3a,b, we demonstrate that affection by using Gazebo and Rviz and by the integration of the python scripts that we prepared. Figure 6 demonstrates some of the fundamentals that we used in our study. Section A represents the objects and environment in Gazebo, section B represents the visualization of the objects and their detection in Rviz. In this demonstration, we aimed to do a comparison between the robot laser beams when it interacts with external objects while creating the map. 1. When the robot just has its front LiDAR sensor which will be represented as the red line, 2. when we integrate the robot back LiDAR sensor which also presented as a red line, 3. when we merge all LiDAR sensors and depth cameras converted scan information which presented as a white line. The robot detects and interacts with various objects, which can be moving, fixed to the ground, or hanging from the ceiling. We selected four objects for our analysis.

Firstly, in images A-1 and B-1, the robot interacts with a table. When using only LiDAR data, the robot detects the table legs, shown by the red points. However, by combining LiDAR and camera data using our approach, all desk boundaries are detected and represented by white dots. For images A-2 and B-2, the robot interacts with a floor lamp that has a head at the top. Using only LiDAR data, the robot detects the vertical column of the lamp, represented by red dots. When camera data is integrated, the boundaries of the lamp head are also detected and projected as white dots, representing the combined sensor data. In images A-3 and B-3, the robot interacts with a human standing in front of it. With only LiDAR data, the robot detects the human legs, shown by red dots. When camera information is added, the robot detects the entire human body, projected as a 2D representation with a white line. Lastly, in images A-4 and B-4, the robot interacts with a chair. Using only LiDAR sensors, the robot detects the chair legs, represented by red dots. By integrating camera information, the boundaries of the chair are also detected, shown by white dots. These results highlight the advantages of fusing cameras with LiDAR sensors, enabling the robot to perceive its environment more effectively and capture finer details for improved navigation and interaction.

4.3.2. Mapping and Localization

Localization and mapping is fundamental for any mobile robot to navigate efficiently and accurately within its environment [

19,

30]. It involves determining the robot’s position and orientation (pose) relative to a map of its surroundings. In the context of SLAM, mapping, and localization are inherently interdependent; each relies on the other to function effectively [

50]. A well-constructed map guides the robot through the environment, aiding in obstacle avoidance and path planning. In this section, we will discuss the methods used for map creation and localization, specifically focusing on three approaches: AMCL, Gmapping, and RTAB-Map. Each method offers unique advantages and is tailored to specific aspects of robot navigation.

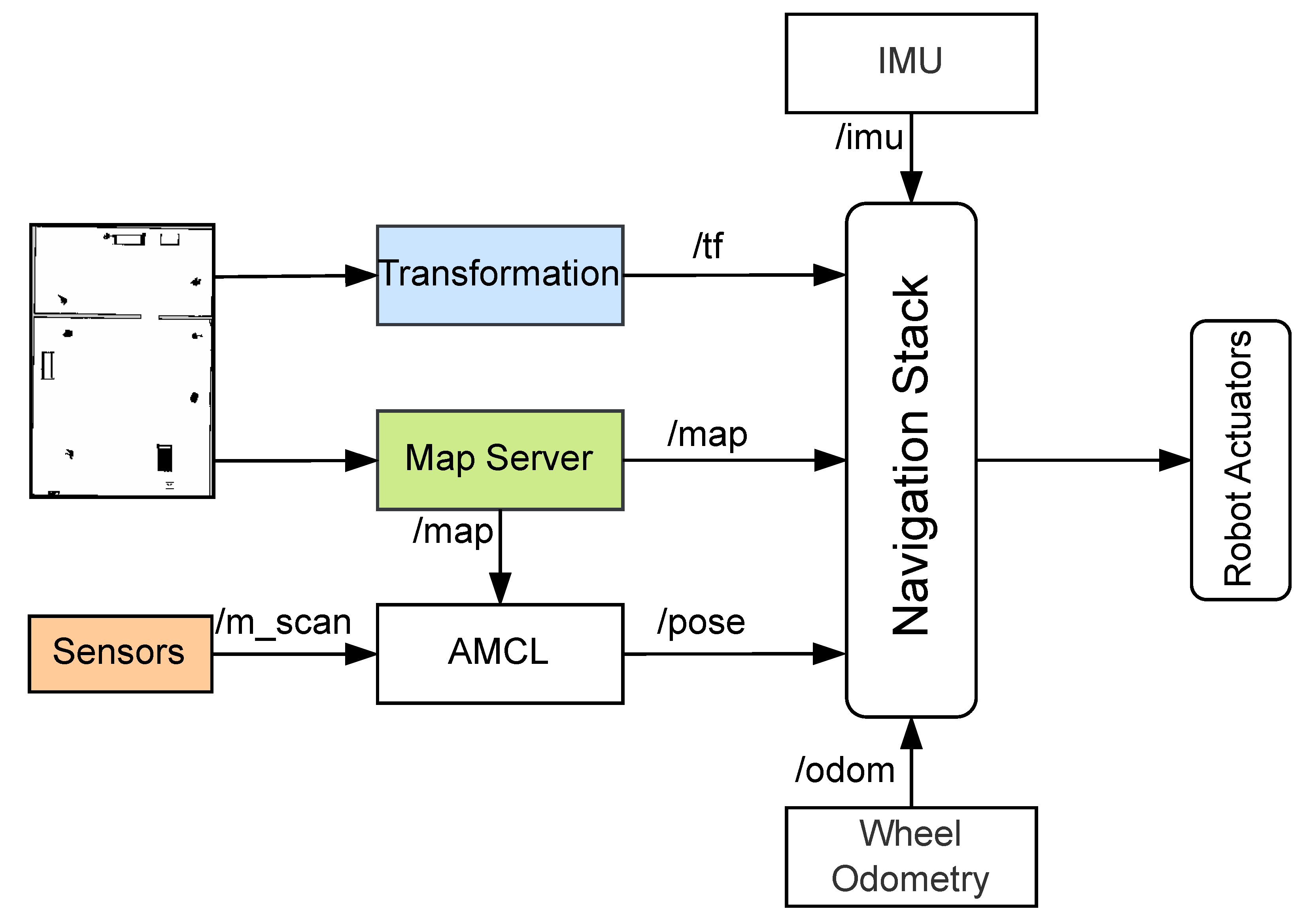

A. G-Mapping and AMCL

Gmapping is a widely used ROS package for implementing SLAM. It utilizes scanning data from cameras and/or LiDAR sensors to map the environment where the robot operates. This package creates a 2D occupancy grid map from laser scan data while estimating the robot’s trajectory. The process involves grid mapping, data association, and pose graph optimization [

21]. Furthermore, AMCL operates in a 2D space using a particle filter to track the robot’s pose relative to a known map. It publishes a transform between the /map and /odom frames, helping the robot understand its position within the environment. The particle filter estimates the robot’s

coordinates. Each particle represents a possible robot pose and has associated coordinates, orientation values, and weight based on the accuracy of its pose prediction. As the robot moves and acquires new sensor data, particles are re-sampled, retaining them with higher weights to refine the pose estimate [

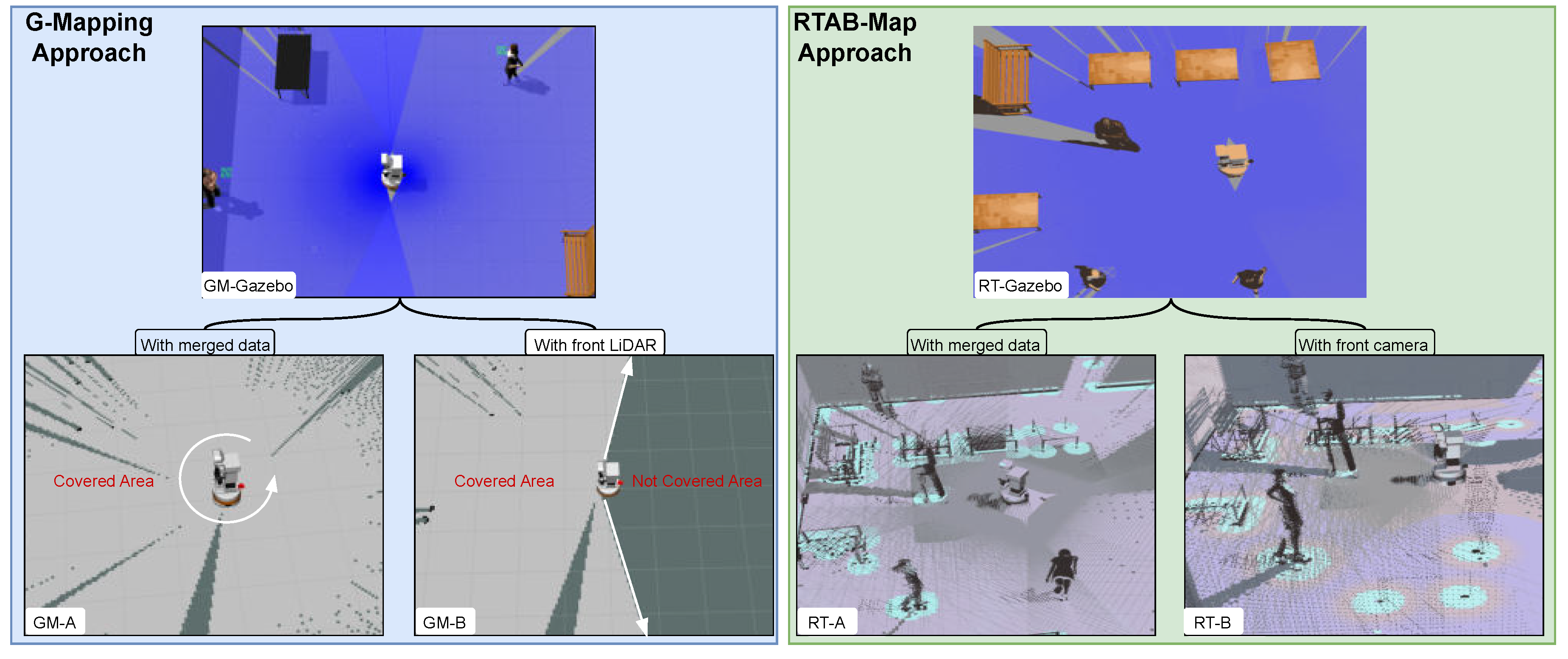

51]. Combining Gmapping with AMCL creates a more robust and reliable SLAM system. This combination improves both map creation time and accuracy. As shown in Figure 8 which is represented in

blue box, we have the same environment built in GM-Gazebo. By integrating additional sensors, such as back LiDAR and multiple RGB-D cameras as in GM-A, around

360-degree is achieved while the robot is stationary.

However, it takes a longer time to move the robot to cover all places in the environment to create the map, as in GM-B. The setup reduces the time required to generate the map compared to using only front LiDAR and front cameras. The sensor setup accelerates mapping and improves detail, allowing the robot to detect elevated objects and obstacles more effectively. AMCL is better in fast localization compared to RTAB-Map localization as seen in

Table 3, and

Figure 11.

Finally, by optimizing EGM and AMCL parameters to utilize data from all sensors, we achieve fast and accurate map generation, facilitating reliable localization and efficient navigation. It leverages the strengths of them, combined with sensor coverage, to develop the robot’s operational capabilities [

52].

B. RTAB Map

As mentioned before, RTAB-Map performs robot mapping and localization using advanced computer vision algorithms and loop closure detection logic [

38]. This approach, while effective, results in high computational demands and longer localization times. During localization, the robot may experience delays in recognizing its position, which in turn affects its ability to reach its goal successfully. Additionally, creating a complete map requires the robot to travel and cover the entire environment, which can be time-consuming.

To address these challenges, we included extra cameras on the robot to speed up data matching and improve localization accuracy. As shown in Figure 8, represented in green box, RT-Gazebo environment consists of three participants and several tables. The RT-A display shows the map created using merged data from multiple cameras, while RT-B) shows the map created using only the front camera sequentially. In the first scenario, RT-A, the three participants and the surrounding environment are detected easily and accurately. In contrast, in the second scenario RT-B, where only one camera is used, only some features are detected initially, requiring the robot to move around the environment to detect the remaining features.

4.3.3. SLAM and Navigation

In our experiment, the navigation setup was configured using the ROS Navigation Stack. First, the environment map was generated using the EGM package, which relies on laser rangefinder data. This map served as the foundation for robot localization. To localize the robot within this map, we used the AMCL package, which performs probabilistic localization using LiDAR data, the map, and initial pose estimates. We employed two mapping methods (G-Mapping and RTAB-Map) and two localization techniques (AMCL and RTAB-Map loop closure detection). This allowed us to test the performance of the navigation stack under different conditions. Three distinct test cases were designed, see Figure 7 with varying environments to assess how the robot navigated under different scenarios.

The simulation was implemented and visualized using Gazebo and Rviz. Python scripts were written to facilitate the simulation process and follow them synchronously. The environments were designed to allow for comparison across different simulation scenarios. Each case involved ten different goals, with the coordinates of each goal stored in TXT files. This was achieved using the /clicked_point topic published from the Rviz interface, allowing automatic storage of goal x and y coordinates for later use. Finally, a Python script published the x and y coordinates from the TXT file and visualized the path by connecting the goals to clearly display the planned trajectory.

4.3.4. Path Planning

After setting up the simulation environment in Gazebo and configuring the /move_base parameters for all scenarios, the next phase of our experiment involved implementing path planning. Once the robot’s position and orientation are localized, a path must be planned to reach the target goal. Path planning is essential for autonomous navigation, ensuring that the robot can move from its current position to the destination while avoiding obstacles [

20]. It is generally divided into two types: global path planning and local path planning.

1. Global Path Planning:

It involves finding an optimal or near-optimal path from the starting point to the destination, considering the entire environment. This planning is done without considering the real-time constraints or dynamic obstacles in the environment [

53]. Common algorithms used for global path planning include A* (A-star), and Dijkstra’s algorithm. These algorithms consider the entire map or environment, including obstacles, to determine the best path. In our setup, we implemented a global path planning algorithm using the ROS packages /global_planner and navfn. These packages generate a global path based on a static map of the environment. The /move_base package works in tandem with the global planner, handling navigation by sending velocity commands to the robot. This component collaborates with the global planner to manage navigation by sending velocity commands to the robot.

2. Local Path Planning:

Local path planning focuses on the robot’s immediate surroundings. It adjusts the robot’s trajectory in real-time, helping it avoid dynamic obstacles while following the global path. Local path planners respond to changes in the environment, making necessary adjustments to avoid obstacles and maintain the planned trajectory. Techniques like potential fields, reactive methods, and artificial potential fields are commonly employed for this purpose [

20]. We implemented local path planning using the /base_local_planner and /dwa_local_planner packages, allowing the robot to make real-time adjustments based on its local environment. However, we observed that the local planner sometimes failed in certain scenarios, especially when limited sensor data was available. This failure could be traced back to the global planner’s initial trajectory calculation. In situations where the robot approached obstacles, such as tables, the empty space between table legs could mislead the robot into thinking a passageway was available, causing collisions.

To ensure a fair comparison and consistent conditions across all three cases, we established ten fixed points on the maps, each with specific positions and orientations, as shown in Figure 7. These points were stored in TXT files using a Python script, ensuring uniformity in the robot’s path planning for each scenario. During the operation of the navigation system, the script continuously logged the positions of clicked points in Rviz to the TXT file by monitoring the /clicked_point topic. This standardization of initial positions, path trajectories, and /move_base parameters was essential for ensuring the repeatability and reproducibility of the experiments.

4.4. Implementation

Due to environmental constraints and the lack of specific sensors, we conducted a small-scale real-world implementation using the Tiago robot with pre-integrated sensors which are 1 RGB-D camera and one 2D LiDAR sensor. The experiment was set up using six independent segments forming a hexagonal path, initializing 1000 particles randomly, see

Figure 10. The

blue area indicates regions mapped with the original Gmapping technique, whereas the

pink area represents our EGM approach, which integrates adaptive resampling and degeneracy handling into classical Gmapping.

This enhancement significantly improved the distribution of particles, shown as red points, making them more concentrated and focused, thus allowing the robot to obtain more precise localization and estimation of its position. The green, black, and blue lines in the visualization represent the planned path, the estimated path using original Gmapping, and the estimated path using our improved method, respectively. The alignment differences between these paths highlight the improvements in robot position estimation.

The quantitative results, summarized in

Table 5, illustrate key performance metrics:

Traveled Distance: Using our EGM, the total traveled distance was 14.95m, compared to 16.10m with the original GM. This reduction demonstrates improved estimation of the robot position based on the distributed particles and in collaboration with obtained sensor fused information.

Time Required: The journey with EGM was completed in 64.70s, whereas GM required 70.90s.

Goals Achievement: Both methods successfully reached all goal points (100% success rate), confirming that the EGM and classical GM are scoring the same target for goal achievement.

Overlap Ratio: The overall overlap ratio with EGM was 68%, while GM had 33.7%. The high overlap ratio in EGM suggests that the particles were more focused, reducing unnecessary dispersion and enhancing robot’s precise positioning.

Average Error: The cumulative localization error in EGM was 0.85m, while GM had a higher error of 1.56m. This 45.5% reduction in error demonstrates the effectiveness of adaptive resampling in maintaining accurate position estimates.

The overlap ratio was used to evaluate the alignment of estimated positions with the true robot position by considering the fraction of particles within a threshold distance of 0.5 meters. It was computed as follows:

where

is the Euclidean distance between particle

and the true position

. The number of particles satisfying

was then used to compute the overlap ratio:

These findings emphasize that integrating adaptive resampling and degeneracy handling in Gmapping enhances particle consistency, leading to more realistic and efficient mapping. The reduction in traveled distance, time, and localization error while maintaining a high goal success rate proves the effectiveness of our approach in real-world implementations.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the evaluation and discussion of our proposed method, focusing on multi-sensor integration with optimal fusion strategies and enhanced mapping.

5.1. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the robot’s performance, we considered key metrics that evaluate its efficiency and effectiveness in navigation. Task accomplishment was measured by the robot’s ability to successfully complete assigned tasks. Time and distance efficiency were tracked by recording the time and distance between goals to evaluate navigation performance and compute the total accumulated time and distance. Success rates were analyzed by assessing the percentage of goals successfully reached versus failures due to obstacles, providing insight into the robot’s obstacle avoidance capabilities (see

Table 1,

Table 3, and Figure 9,

Figure 11). Resource consumption, including battery efficiency and CPU usage, was monitored to understand the computational and energy demands during operation. Stability was evaluated by analyzing the robot’s linear and angular velocities to ensure smooth and consistent movement (see

Table 2,

Table 4). To further analyze time and distance efficiency, we normalized execution times and distances relative to the maximum recorded time and distances. Then, we visualized them using a heatmap. Warmer colors with higher numbers indicate longer execution times and longer distances, while cooler colors with small numbers represent faster performance, allowing for an intuitive comparison of sensor configurations.

For real-world implementation, as described in

Section 4.4, we followed the same strategy as in the simulation while additionally incorporating the overlap ratio metric, which quantifies the alignment of the estimated robot position relative to the given position.

5.2. Sensor Configuration Analysis

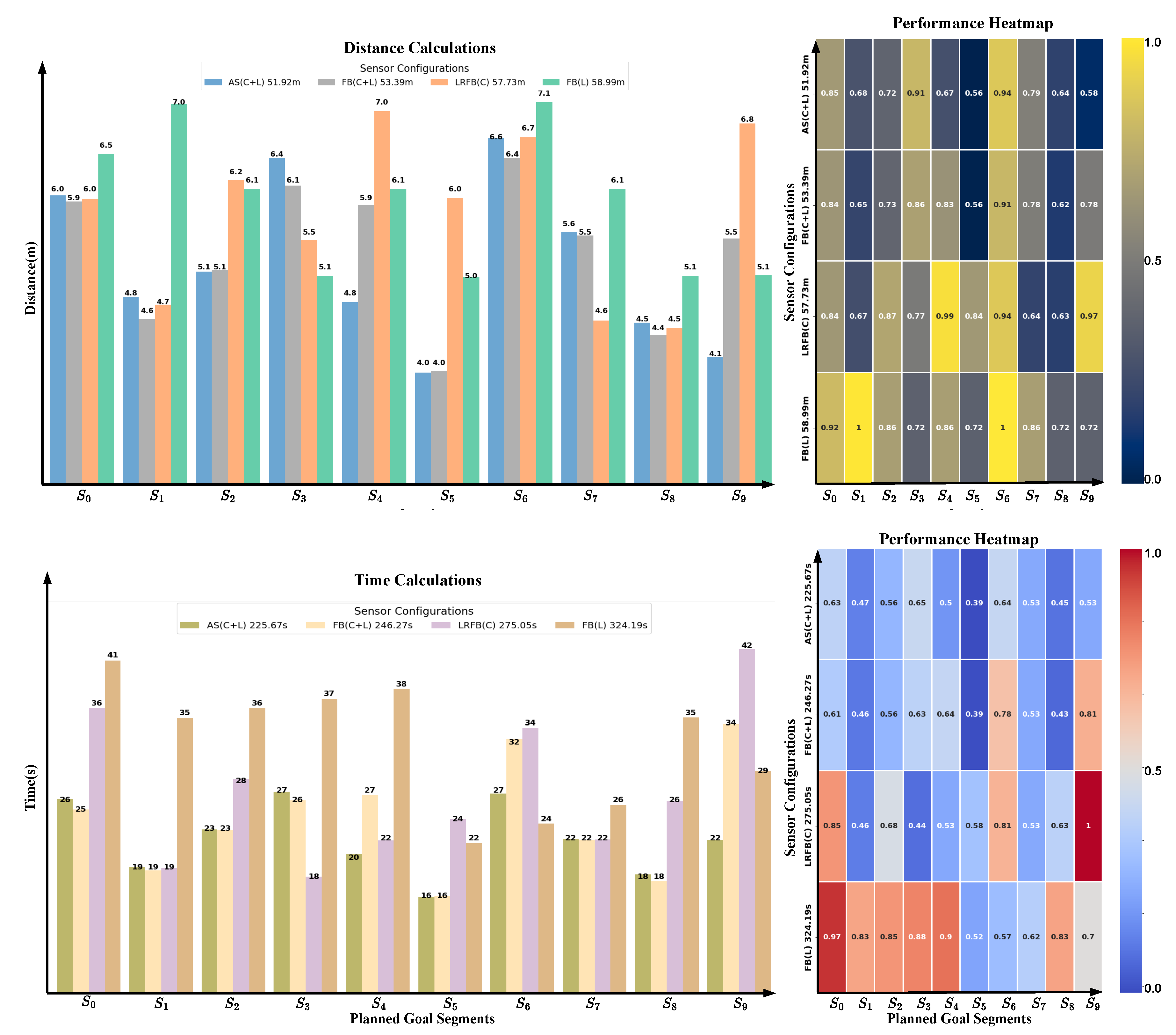

To evaluate the impact of different sensor configurations on navigation performance, we conducted experiments with four distinct setups using our EGM method:

1. AS(C+L): All sensors, incorporating both cameras and LiDARs.

2. FB(C+L): Front and back cameras and LiDARs.

3. LRFB(C): Left, right, front, and back just cameras.

4. FB(L): Front and back just LiDAR sensors.

As shown in Figure 9 and

Table 1,

Table 2, all the details and comparisons discussed in this section are provided in these visualizations and tables. Utilizing all available sensors,

AS(C+L), which combines all cameras and LiDARs, significantly improved navigation efficiency. This configuration resulted in the shortest travel distance of

51.8 meters and the lowest travel time of

223.7 seconds, outperforming all other setups.

Incorporating only front and back cameras and LiDARs, FB(C+L), enabled the robot to reach all goals successfully. However, it required more time (54.3 seconds) and travel distance (245.5 meters) compared to AS(C+L). When relying solely on cameras, LRFB(C), the robot became stuck at one goal, preventing full completion of the planned journey. In contrast, using only LiDAR sensors, FB(L), resulted in just 40% navigation success, with the robot failing to complete the journey due to obstacles. Moreover, the heatmap indicates that areas with shorter time and distance values are concentrated at the top of the grid. As sensor configurations are reduced, both execution time and distance increase, visually demonstrating the performance decline with fewer sensor incorporation. Battery and voltage consumption was minimized using AS(C+L), with a charge decrease of 5.3% and a voltage drop of 2.6%. CPU usage was also the lowest in this configuration. Stability analysis further demonstrated that AS(C+L) provided more consistent linear and angular velocity, ensuring smoother motion.

In real-time implementation, as shown in

Table 5, a slight improvement was observed when comparing EGM with GM in terms of time, distance traveled, overlap ratio between planned and estimated segments, and average error generated. Although environmental constraints limited the scale of our experiments compared to the simulations, the results were still sufficient to demonstrate that incorporating both visual and LiDAR-based data, combined with a well-designed fusion framework and adaptive particle assembly, allows the robot to navigate effectively in complex environments in both simulation and real-world applications.

5.3. Environmental Configuration Analysis

This section evaluates the performance of the proposed EGM method across different environments: simple, moderate, and complex. The goal is to fairly compare the impact of adaptive sampling and degeneracy handling, combined with our sensor fusion technique, against the RTAB-Map approach in varying environmental conditions. The evaluation was conducted using various performance metrics, as shown in

Figure 11 and

Table 3,

Table 4.

In a simple environment, the proposed EGM method completed the task in 230.04 seconds, compared to 327.65 seconds using the RTAB method. The distance covered was 53.04 meters with our approach versus 56.92 meters with RTAB. Additionally, the RTAB-Map approach caused the robot to get stuck at two goals, while our method successfully reached all goals.

In a moderate environment, the proposed method completed the task in 238.83 seconds, compared to 254.93 seconds with the RTAB method. The distance covered was 54.31 meters with our approach versus 58.27 meters with RTAB. Similarly, the RTAB-Map approach caused the robot to get stuck at one goal, whereas our method successfully navigated to all goals.

In a complex environment, the proposed method completed the task in 287.29 seconds, compared to 335.0 seconds with the RTAB method. The distance covered was 66.65 meters with our approach versus 73.37 meters with RTAB. Again, the RTAB-Map approach resulted in the robot getting stuck at two goals, while our method successfully completed the entire task. Additional metrics, including charge and voltage consumption, CPU usage, and motion stability, further highlight the advantages of our approach. While both methods showed increased CPU demand as environmental complexity grew, our approach maintained lower CPU usage in certain cases. In terms of motion stability, both methods demonstrated stable linear and angular velocities, ensuring smoother navigation.

These results demonstrate that the proposed method have slight competitive results against RTAB in terms of time efficiency and distance traveled across various environments. This is primarily due to the localization requirements of RTAB-Map, which involves processing intense features to help the robot localize and move to the next goal.

6. Conclusion

In this work, we developed an improved SLAM system for mobile robot navigation by combining our sensor fusion technique with an enhanced mapping approach. Our fusion method converts RGB-D point clouds into 2D laser scans, allowing seamless integration with LiDAR data, while parallel noise filtering improves sensor reliability. To enhance localization, we introduced Enhanced Gmapping (EGM), which includes adaptive resampling and degeneracy handling to maintain particle diversity and degeneracy handling to prevent mapping errors. These improvements made the system more stable and accurate. Our approach slightly improved traditional methods, achieving 8% less traveled distance, 13% faster processing, and 15% better goal completion in simulations. In real-world tests, EGM further reduced the traveled distance by 3% and execution time by 9%, demonstrating its effectiveness. Despite these improvements, challenges remain, such as difficulty detecting objects with gaps, like table legs, which can cause navigation errors. To address this, we plan to integrate AI-based solutions, including LSTM for better memory of visited locations and CNNs for improved object recognition. Additionally, we will test the system in more complex and dynamic environments beyond controlled simulations to further validate its real-world applicability. These advancements will improve the system’s adaptability and reliability, making it more effective for real-world autonomous navigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A.-L. and A.A.-H; methodology, M.J., A.C., and B.A.-L; software, A.C., and B.A.-L.; validation, A.A.-H, M.J., and B.A.-L; investigation, B.A.-L., A.A.-H, and M.J.; resources, A.A.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.-L., A.C., and M.J.; writing—review and editing, B.A.-L., A.C., M.J., and A.A.-H.; visualization, B.A.-L., M.J., and A.C..; supervision, A.A.-H.; project administration, B.A.-L. and A.A.-H.; funding acquisition, A.A.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.