1. Introduction

The constant development of highly sophisticated techniques in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures using ionizing radiation has shown a growing demand for reliable and accurate dosimetry techniques. Innovative high performance dosimetry methods require materials capable of determining absorbed dose, even when information on energy and nature of charged particles at the point of interest is incomplete or fragmentary [

1].

On the one hand, novel radiosensitive materials may be used to simulate human tissues and organs, commonly referred to as tissue-equivalent materials [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], or to determine absorbed dose in water following the international dosimetry protocols TRS-398 IAEA and TG-51 AAPM, in the latter case referred to as water-equivalent materials [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Selecting an appropriate dosimetry material requires comprehensive information about its properties, ideally matching the absorption and dispersion characteristics of the target material to be emulated. Gel dosimeters emerge as the most suitable option for designing and implementing dosimeters capable of performing direct measurements of absorbed dose in aqueous media [

10].

International ionizing radiation dosimetry protocols recommend both instrumental and measurements’ calibration be expressed in terms of absorbed dose in liquid water, under normal temperature/pressure conditions [

1,

14]. Therefore, it is desirable to develop dosimeters with sensitive volumes made of materials having radiation interaction properties close to those of liquid water, so that correction factors may not be necessary and beam perturbation is avoided during the irradiation. Furthermore, water-equivalence dosimeters are necessary to enable consistent benchmarking against reference dosimetry protocols and to enhance the reproducibility of dose measurements across varying radiation fields and energies. In this regard, if two materials have similar mass absorption/scattering properties for photon and charged particles’ beams over a certain energy range, then the corresponding particle transport and further dose deposition for both materials will be similar [

15]. Hydrogels are three-dimensional (3D) polymer networks that are strongly imbibed by water, whose amount approaches up to 99 % w/w of the total hydrogel mass [

16]. Thus, in terms of radiation-matter interaction, compounds candidate to dosimetry materials can be considered water equivalent if the corresponding fundamental physical quantities, such as the mass attenuation coefficient (

) and the mass stopping power (

), are consistent (typically, less than 1% deviation is accepted) with those of liquid water -considered as the reference material- within the energy range of interest [

1,

2,

10];

stands for the incident intensity that penetrates a material of mass density

and thickness

x and

I is the emerging intensity; while

E is the average energy dissipated per unit of traveled length in the compound.

Hence, proper assessment of the bulk mass density (

) of materials of dosimetry interest stands as extremely important since it allows to establish radiation-matter interaction properties required for radiological applications, as previously proposed by many authors through multiple approaches [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Besides, searching for innovative approaches for developing systems with high tissue equivalence, the use of microbiological agents distributed in hydrogels is proposed. Bacteria have shown promise as tools in whole-cell biosensors, leveraging their biochemical complexity, [

23] for applications such as bioremediation tasks [

24] and even as therapeutic agents in the fight against cancer [

25].

In this context, combining the metabolic activity of microbiological agents with gel-based dosimetry characteristics [

10,

26,

27,

28] emerges as an innovative approach using biotechnology and molecular biology procedures as an unconventional alternative to develop a whole cell sensor, also representing a potential approach to achieve 3D dose mapping within biological environment. Consequently, the proposed sensor, utilizes bacterial culture media capable of characterizing the absorbed dose through the survival of these microorganisms [

29].

Therefore, this study aims to determine the mass density of two hydrogel-based cell culture media:

i) Medium with Agar-Agar (MAA) and

ii) Medium with Agar-Agar and Glucose (MAAG) [

29], which are suitable for both irradiation and bacterial growth, considering the presence or absence of Staphylococcus Aureus (SA) and Escherichia Coli (EC) strains. Thus, accurate assessments of the bulk mass density of the proposed hydrogel-based bacteria-infused dosimeters have been performed as key information leading to similarities/discrepancies in radiation attenuation/scattering properties, thereby ultimately affecting the accuracy of dose measurements. Additionally, considering that SA-inoculated systems have already been investigated reporting the corresponding dose-response performance [

29], the viability of EC-inoculated systems is evaluated for its potential application in radiation dosimetry within the 0-10 Gy range, using simple analytic techniques, such as spectrophotometric and bacterial culture methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture Media and Bacterial Strains

Culture media are intended as a set of essential nutrients that create the conditions for the development of the microorganisms under study. Based on previous publications [

29,

30], Agar-Agar has been used as the main component and support matrix for culture media solutions. Also, sodium chloride (NaCl) is added to the solution to promote an isotonic concentration, fostering conditions similar to those of biological tissues and optimal for microbial growth. In order to provide sufficient nutrients to promote proper bacterial growth, Agar PCA is used, forming the first medium (

MAA), while the second developed medium, called

MAAG, contains a glucose addition to the

MAA formulation. Both compositions are summarized in the

Table 1 [

29].

The media are studied with and without inoculated bacterial content within them, to develop systems with high tissue-equivalence by using bacteria distributed in hydrogels, since the proportionality between the absorbed dose due to X-rays and the number of colony forming units has been demonstrated [

31].

The first bacterial strain used is Staphylococcus−aureus (SA), an anaerobic, Gram-positive, coagulase and catalase positive, motionless and non-sporulating bacteria. Its diameter ranges from 0.5 to 1.5

and tends to form grape-like clusters [

32].

The second strain used is Escherichia Coli (EC) ATCC

®25922. EC is a Gram-negative bacillus approximately 1

long and

wide, although it may vary depending on the strain and its conditions. It may have flagella operating as whip-like structures for mobility or pili for surface adherence. Physiologically, it is an facultative anaerobe capable of growth with or without oxygen, but cannot grow at extreme thermal or pH conditions [

33]. Phylogenetically, it belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family and is closely related to pathogens such as Salmonella, Klebsiella and Serratia [

34].

2.2. Culture Media’ Preparation and Inoculation

Each medium is prepared, with a reduction of 1 ml of water in the case of samples designated for inoculation, and sterilized. Those volumes that are not to be inoculated are poured into cells of 1 × 1 × 2 , cataloged and sealed with parafilm. The inoculated media are kept in a water bath at 50 ºC to prevent premature gelation.

For each bacterial strain, two vials are prepared, each containing 1 ml of sterilized distilled water and inoculated with one loopful of the respective strain. Once homogenized, the volumes of

MAA and

MAAG are inoculated accordingly and poured into cataloged cells and sealed with parafilm. A total of 18 samples is prepared, as reported by

Figure 1.

The density test is performed for each media, with and without bacteria, at 5, 25 and 37 ºC. Once the samples are prepared, each is maintained at its designated temperature for at least 24 hours. For streamlined measurement processing, each sample is cataloged as indicated in the

Table 2.

2.3. Mass Density Measurements

Density measurements of each medium in the presence and absence of bacteria at different temperatures are carried out from two different approaches. It should be noted that, since the water content in each medium is higher than 96 %, densities are expected to approximate that of liquid water.

The first approach consists of direct mass and volume measurements of each sample. Mass measurements are performed with

Mettler Toledo ME204 (Mettler-Toledo S.A.E., España) analytical balance, while volume measurements are carried out by recording the lengths of each side of the cube that conforms the sample with a ±

precision rule. Each measurement is made at least three times per sample, from which the average is calculated and the density is determined by using the equation:

where

is the density and

m and

V are the mass and volume of the sample, respectively.

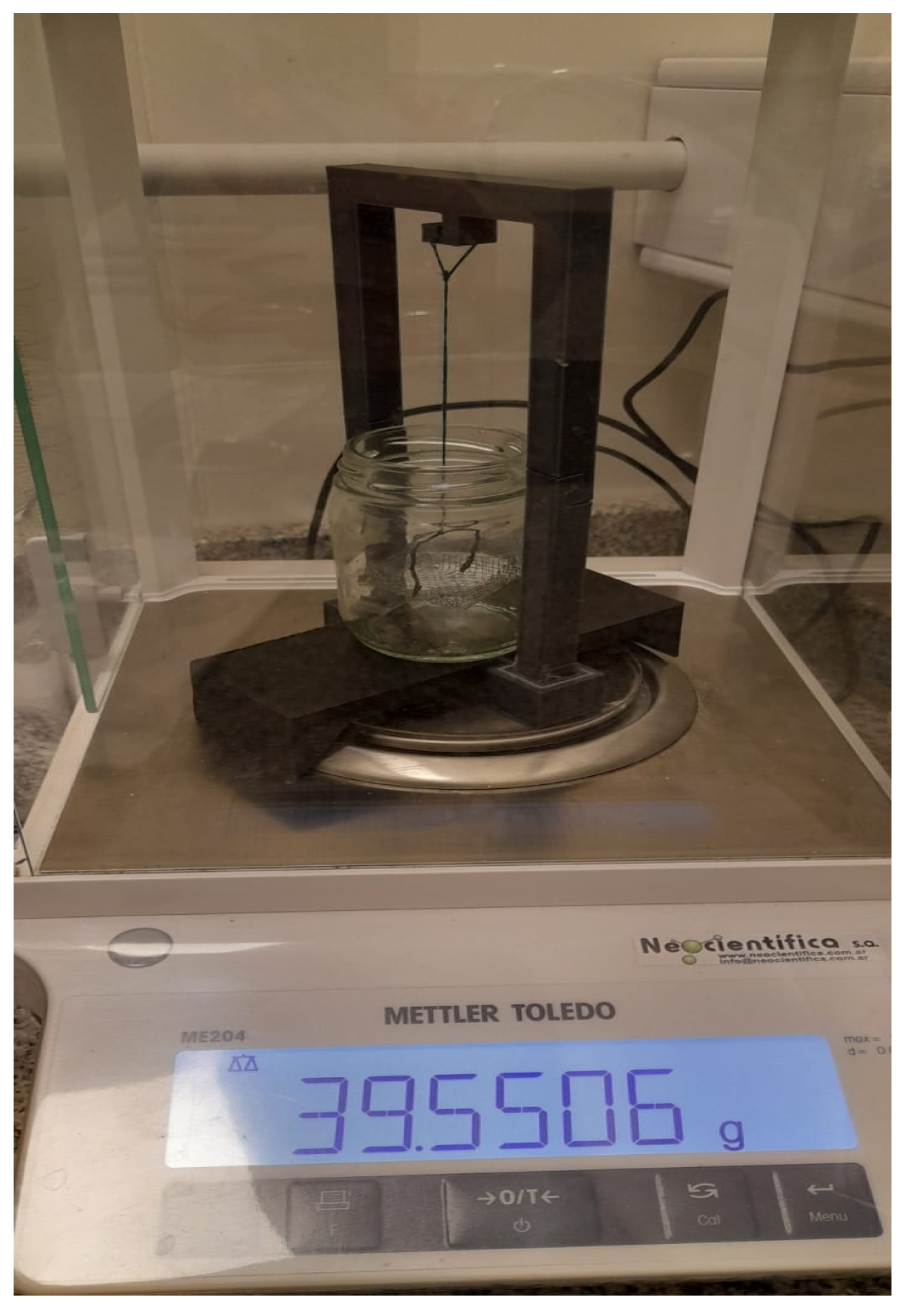

For the second approach, using the setup shown in

Figure 2, the density of the media is determined from the Archimedes’ principle.

The procedure is as follows: Firstly, it has to be ensured that the balance is calibrated and zeroed. Then, the mass in air () of the basket that will hold the sample and the mass in air of the basket containing the sample are weighed (). Subsequently, the mass of the basket submerged in a liquid with known density is performed (), in this case, heptane with a density has been used. Finally, the basket mass containing the sample immersed in heptane () is established.

Once these data are known, it is possible to calculate the mass of each sample in air (

) and immersed in heptane (

), the thrust mass (

) from which it is possible to know the volume of the sample (

), and finally determine its density (

). Equations (

2) to (

6) detail the calculations for each of these parameters. A minimum of three measurements is performed per sample to ensure accuracy.

It is worth remarking that maintaining the heptane at the same temperature as the samples during density measurements at different temperatures is mandatory.

2.4. Microbial Growth Feasibility and Characterization

After determining the density of the corresponding media, EC is cultured in Petri dishes containing the prepared media to assess whether the strain can grow effectively. The plates are incubated for 24 h at 37 ºC.

If growth is confirmed, its characterization follows a procedure similar to that in [

29]. Each culture media batch is separated into two volumes V1 and V2. Where V1 corresponds to the non-inoculated samples and is poured into blank cells, while V2 corresponds to the culture material to be inoculated. Prepared samples are initially stored at 4 ºC for at least 8 hours. Subsequently, the blank samples are brought to their respective temperatures, while V2 is heated in a water bath at 55 ºC with constant stirring and inoculated by adding 1 mL of distilled and sterilized water, at the same temperature, containing 2 mg of EC microbiological content per 15 ml of media. Once homogenized, the preparation is poured into cells to be stored at 4, 25 and 37 ºC, respectively.

A total of 3 blank cells and 12 inoculated cells are prepared per media. Absorbance measurements are performed with a UNICO S1205 spectrophotometer at 800 nm every 15 min after inoculation.

2.5. Dose-Response Preliminary Performance

The absorbed dose along with absorbed dose rate values have been established correctly using a calibrated ionization chamber system, consisting of a Farmer PTW type ionization chamber, a UNIDOS electrometer, and the corresponding extension cable, together with the calibration certificate for soft X-rays beams up to 30 kVp. The water-proof ionization chamber was placed inside a spectrophotometry vial filled with distilled water to adequately represent the irradiation conditions of the test samples, as shown in

Figure 3.

A preliminary assessment of the dose-response performance is achieved by irradiating the samples through gelled media with microbiological content in stationary phase, under the following conditions: 3 samples serve as blanks (non-irradiated), 3 samples are irradiated at low doses (± Gy ), 3 samples are irradiated at an intermediate dose level (± Gy) and 3 samples are irradiated at a high dose (± Gy). Once irradiated, the samples from each group are stored at different temperatures, 4, 25 and 37 ºC.

The samples were irradiated using an orthovoltage X-ray tube available at the LIIFAMIR

x laboratory facilities. A conventional 1 kW power tube (YXLON EVO 225)[

35] provided with a tungsten anode has been configured to operate at 150 kV,

mA to irradiate samples placed at a source-surface distance (SSD) of

±

cm. Absorbance measurements are recorded before irradiation of the sample, and post-irradiation measurements are carried out during the first 3 h as well as 24 and 48 h after irradiation in order to control possible variations over time.

3. Results and Discussion

This section is organized according to the proposed scopes reporting mass density of culture media in first instance followed by the characterization of microbial assay growth and, finally, a preliminary approach to the corresponding overall dose.-response to X-ray radiation.

3.1. Culture Media Mass Density

3.1.1. Mass Density Assessment According to the First Measurement Approach

The results obtained from the first approach are shown in

Table 3, where the average mass and volume measured for each medium and corresponding density are reported. Uncertainties were calculated from error propagation.

Notably, no significant mass density differences have been found between media with and without bacteria according to the corresponding uncertainties. This trend might be expected given that the variations are due to a combination of the presence or absence of bacteria and the presence or absence of glucose. Furthermore, since the elemental composition of bacteria generally includes mainly carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen, which are predominant elements in chemical/polymer dosimetry gels, the differences concerning them are comparable.

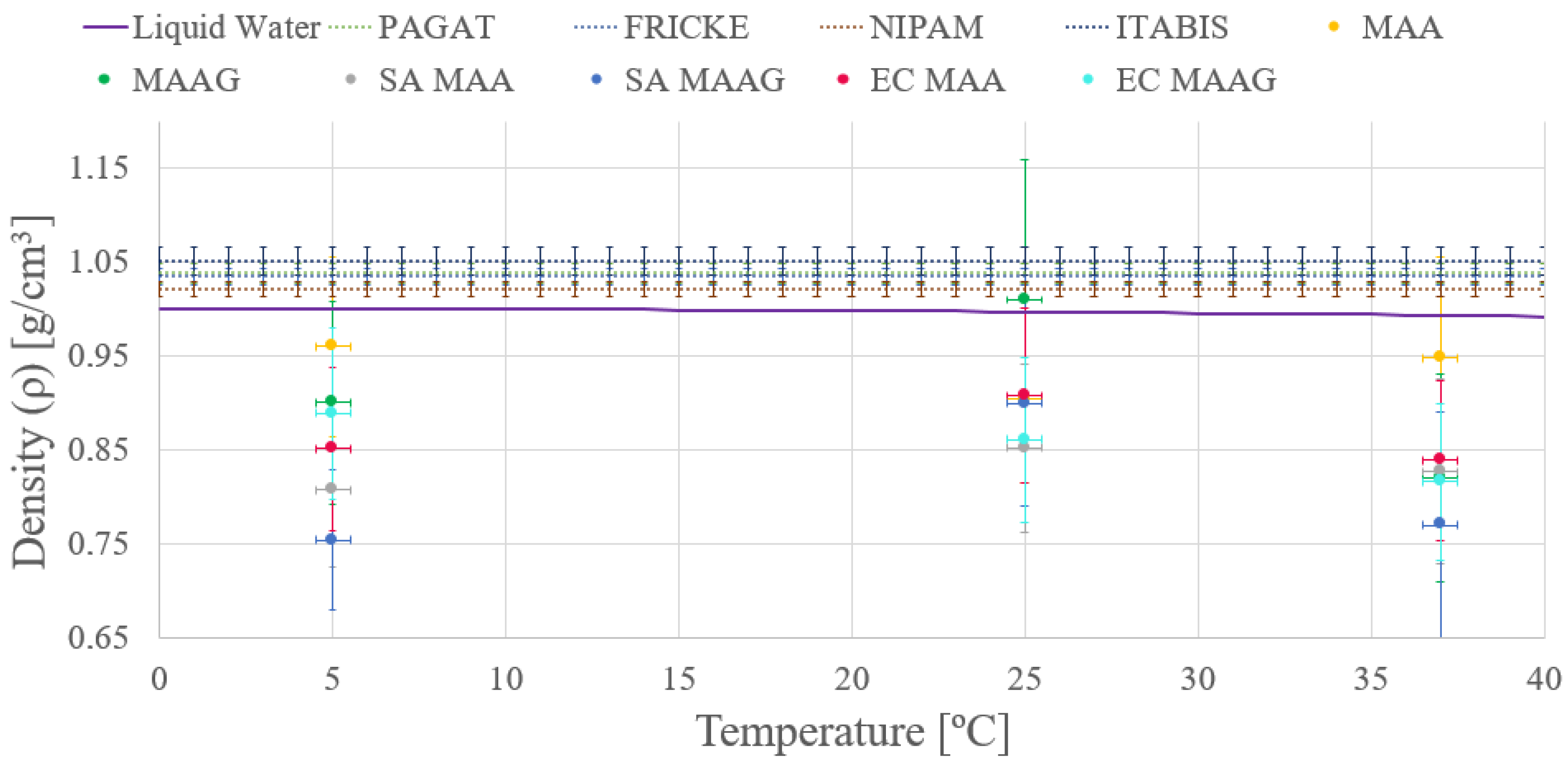

As depicted in

Figure 4 both media present enhanced density in the absence of bacteria, a trend consistent across both strains studied. However, given uncertainties ranging from 9 and 16 % of the final value obtained, stemming from the applied measurement methodology, conclusions based on this trend may be premature, feature that will be reassessed after reviewing results from the second measurement approach. Additionally, the mass density of dosimetry gels is comparable to the liquid water, as widely reported in literature [

10,

36,

37].

Moreover, another remarkable observation is that the density of both media varies with temperature.

3.1.2. Bulk Mass Density Assessment According to the Second Measurement Approach

The results obtained from the second approach are summarized in

Table 4, presenting the values of mass in air (

), mass immersed in heptane (

), along with the values obtained for volume (

), mass density (

) and corresponding uncertainties.

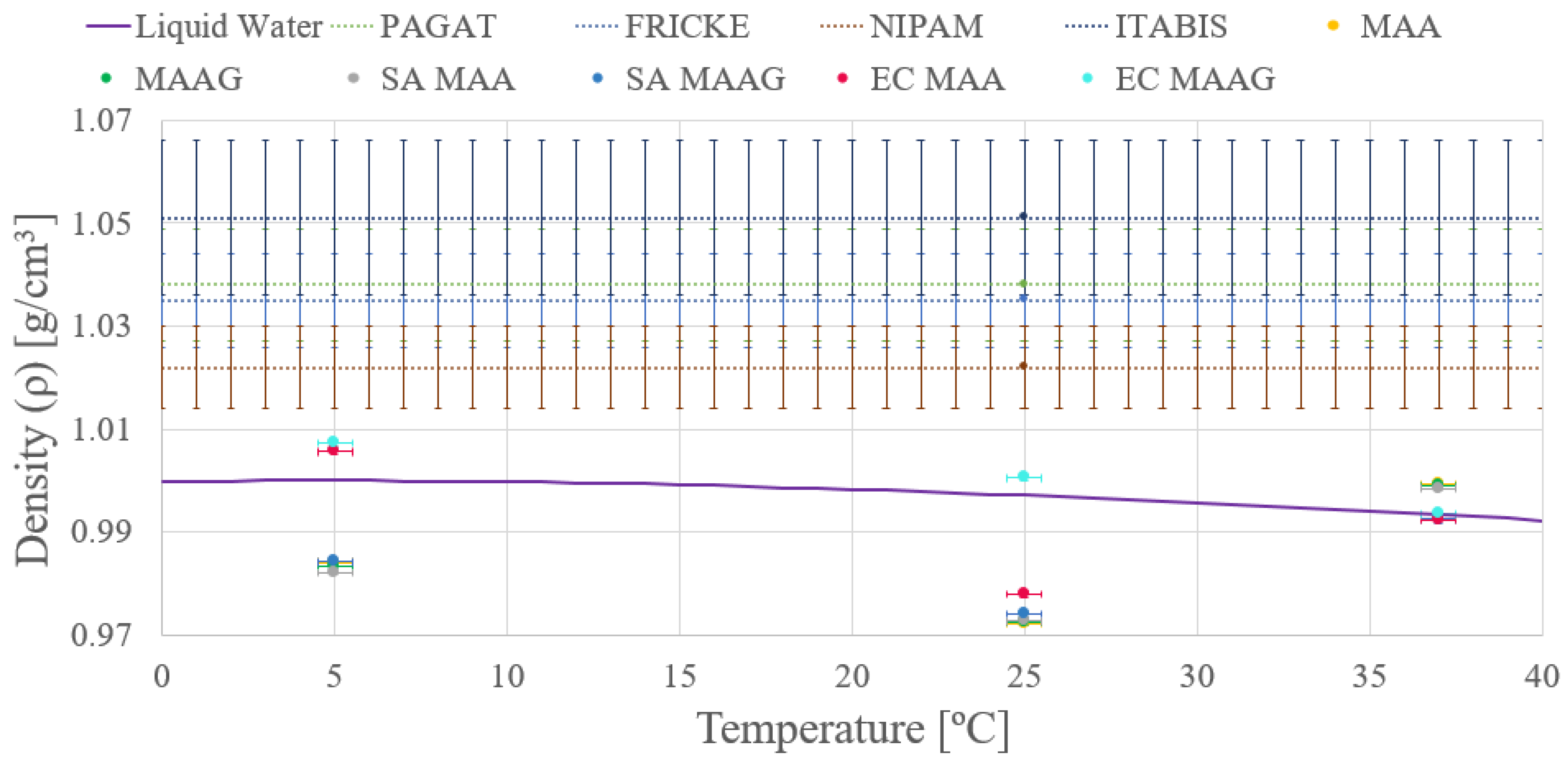

Similar to the findings of the first approach, it can be noted that the final density values do not exhibit significant differences. However, the second approach shows enhanced precision in both measurements and density calculations, as may be appreciated in the

Figure 5, where almost negligible variations are shown between the media with and without microbiological content. Data are reported for both liquid water and different dosimetry gels.

Conversely, it is evident that while the obtained mass density values do not coincide with the liquid water within corresponding uncertainties, they are closer than those obtained through the first approach. In addition, the uncertainties achieved from the second approach vary between and %, which are significantly lower than the uncertainties obtained from the first approach.

Thus, the second approach and its results are considered for guiding future tests and studies, whether from an experimental, theoretical or computational point of view.

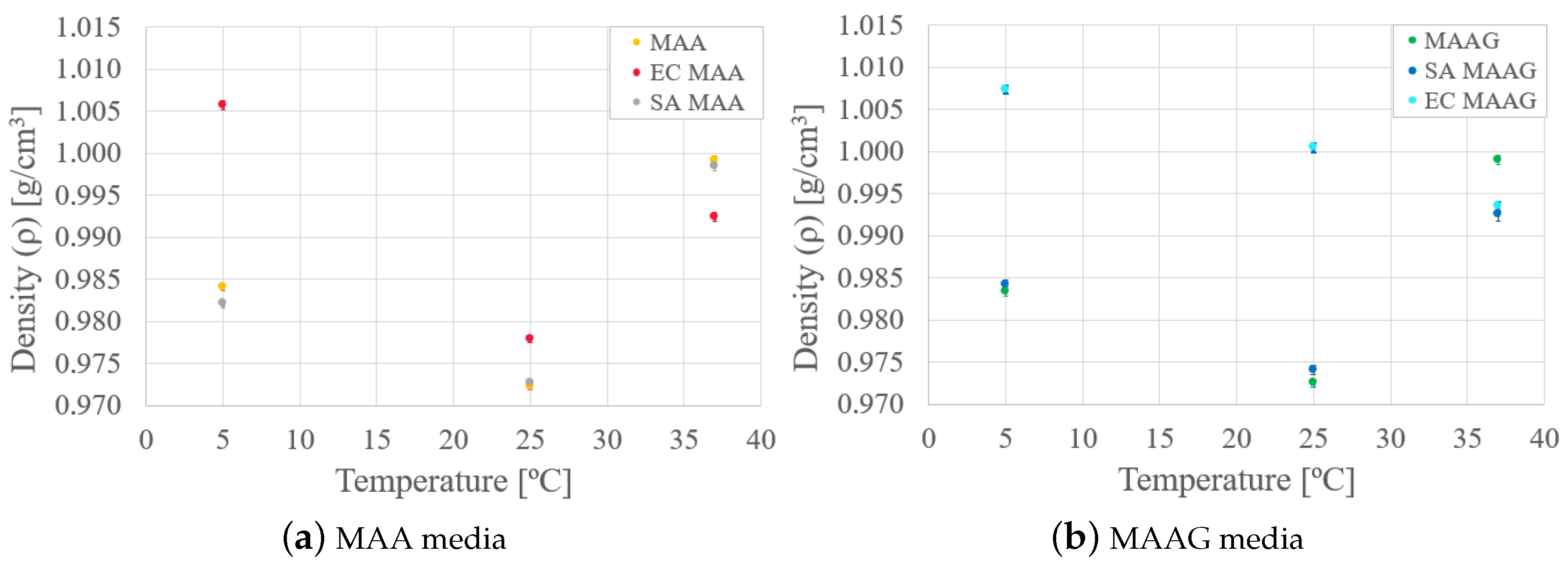

Finally, analyzing the mass density behavior of each medium in the presence and absence of bacteria, as reported in

Figure 6, it is possible to reaffirm that mass density varies as a function of temperature for both media. In the case of the SA strain, the behavior is similar to that of the media without microbiological content, while with the EC strain, greater variations occur, especially at lower temperatures where the density is higher.

Likewise, as the temperature increases for both media and strains, there is generally an enhanced similarity between samples with respect to their mass density values.

It should be noted that the low density variation observed in the materials of interest, under the conditions studied, implies a lower effect on the mass attenuation coefficient and stopping power [

1,

2,

10] if the materials are compared in terms of radiation-matter interaction. Furthermore, by presenting densities similar to water, it could be preliminarily inferred that the proposed materials might present high tissue equivalence if low-density (soft) tissues are considered [

38,

39].

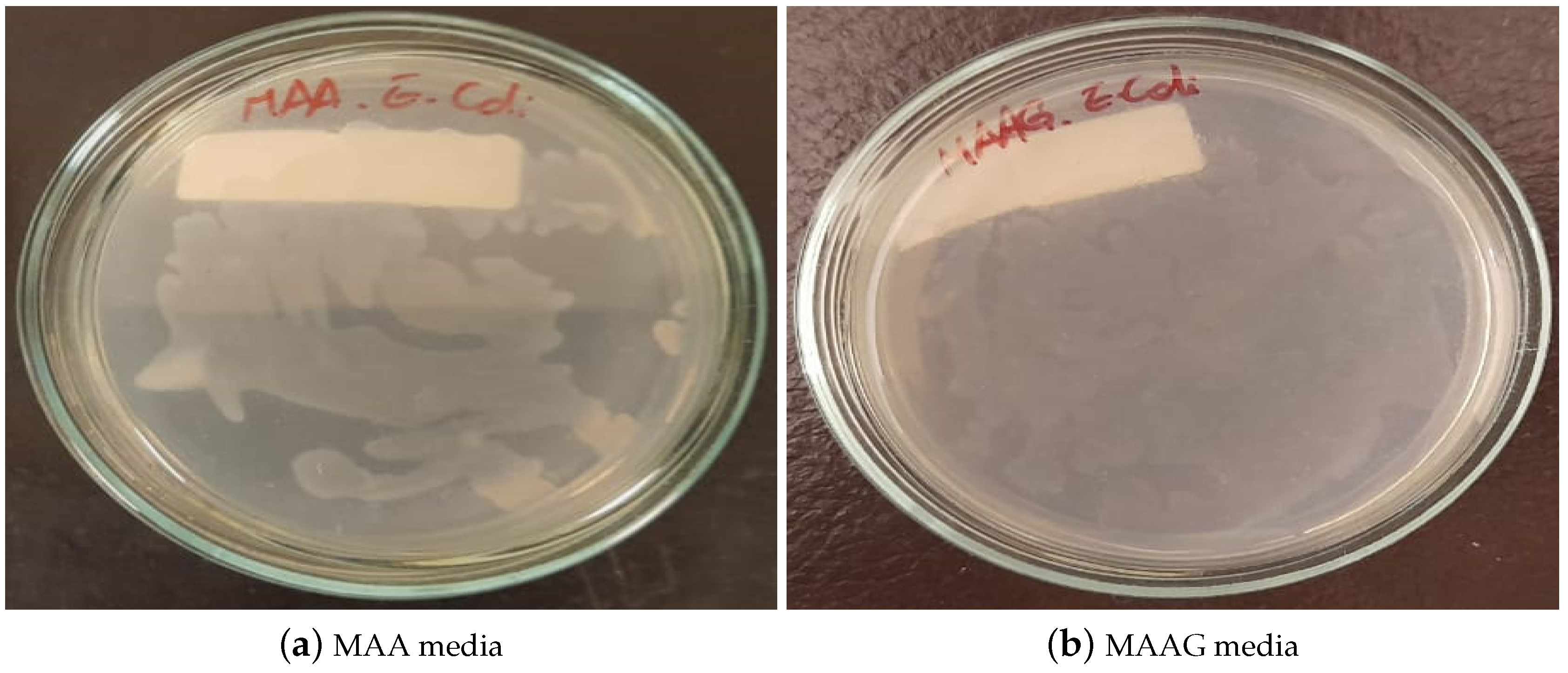

3.2. Microbial Growth Characterization

After 24 hours of cultivating and incubating the EC strain in each culture medium, the results of bacterial growth were visually inspected. As illustrated in

Figure 7, growth is confirmed in both media, highlighting their suitability for microbiological growth, with notable differences, MAAG presenting greater growth compared to MAA. This result aligns with expectations, since the presence of glucose in MAAG serves as a primary energy source for microorganisms [

40], thus facilitating more effective bacterial growth.

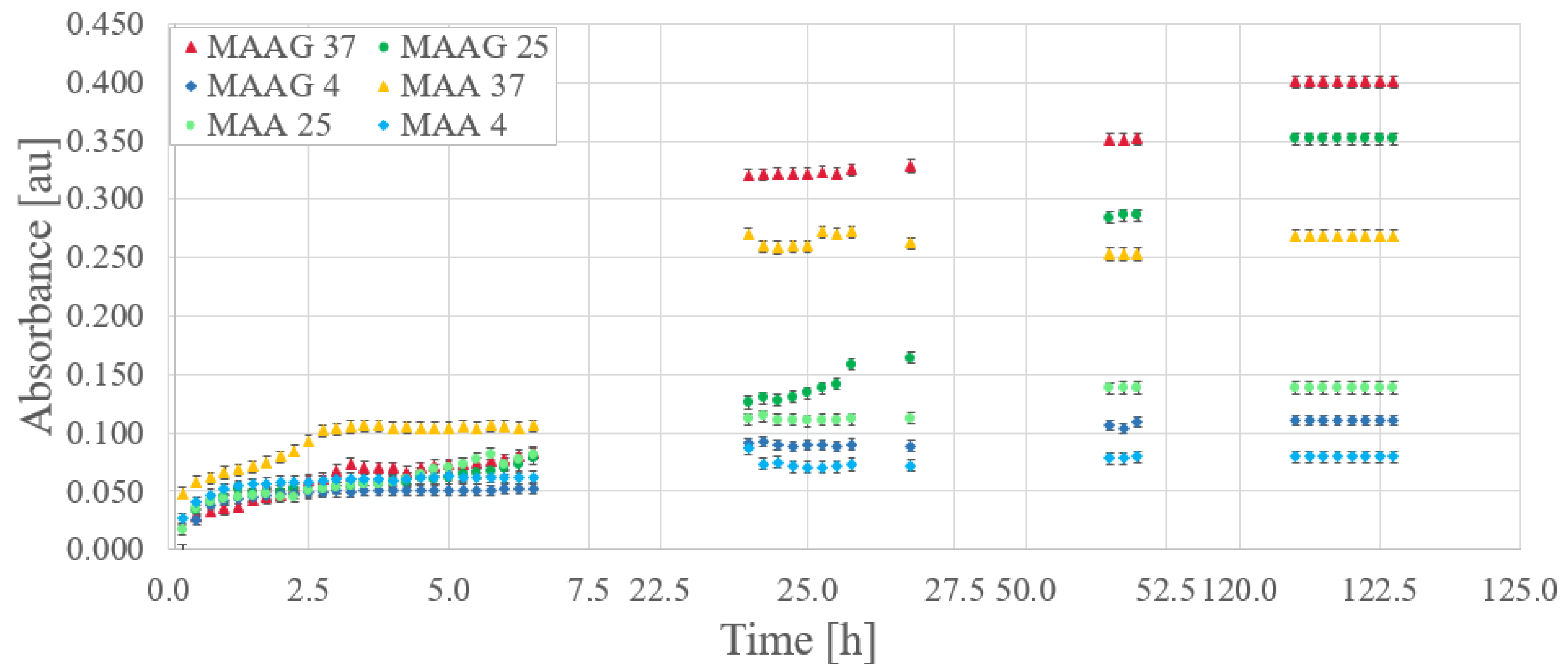

Based on preliminary characterizations of the proposed culture media [

29], optical absorbance measurements were performed in triplicate for EC samples inoculated at 800 nm, with readings taken at 15-min intervals.

Figure 8 reports the bacterial growth obtained for each culture media. Gaps between data (missing points) correspond to periods during nights or weekends when measurements were not feasible.

Relevant considerations arise when comparing storage temperatures for the same growing medium. Direct inspections reveal that, while initial bacterial growth is robust at all temperatures, over time, samples stored at higher temperatures exhibit higher absorbance, while those stored at 4 ºC demonstrate lower growth compared to those stored at 25 or 37 ºC. Unlike the results reported for the SA strain, where the greatest growth after a period of time occurs at lower temperatures [

29].

However, the samples corresponding to the MAAG media present a higher growth rate, favored by the presence of glucose.

Table 5 displays the percentage differences in growth between the two media for different temperatures with the EC strain, which is also illustrated in the

Figure 8. Notably, as time increases, percentage differences become more pronounced for the MAAG medium, as compared to the MAA media at the same temperature. Although the highest final growth is reported at a temperature of 37 ºC, the highest percentage differences in growth between media occur at 25 ºC, reaching a value of 153 %, indicating that, at this temperature, the presence or absence of glucose in the media has a significant impact.

It should be noted that the percentage differences in growth between media exceed the 25 % reported for the SA strain in all cases.

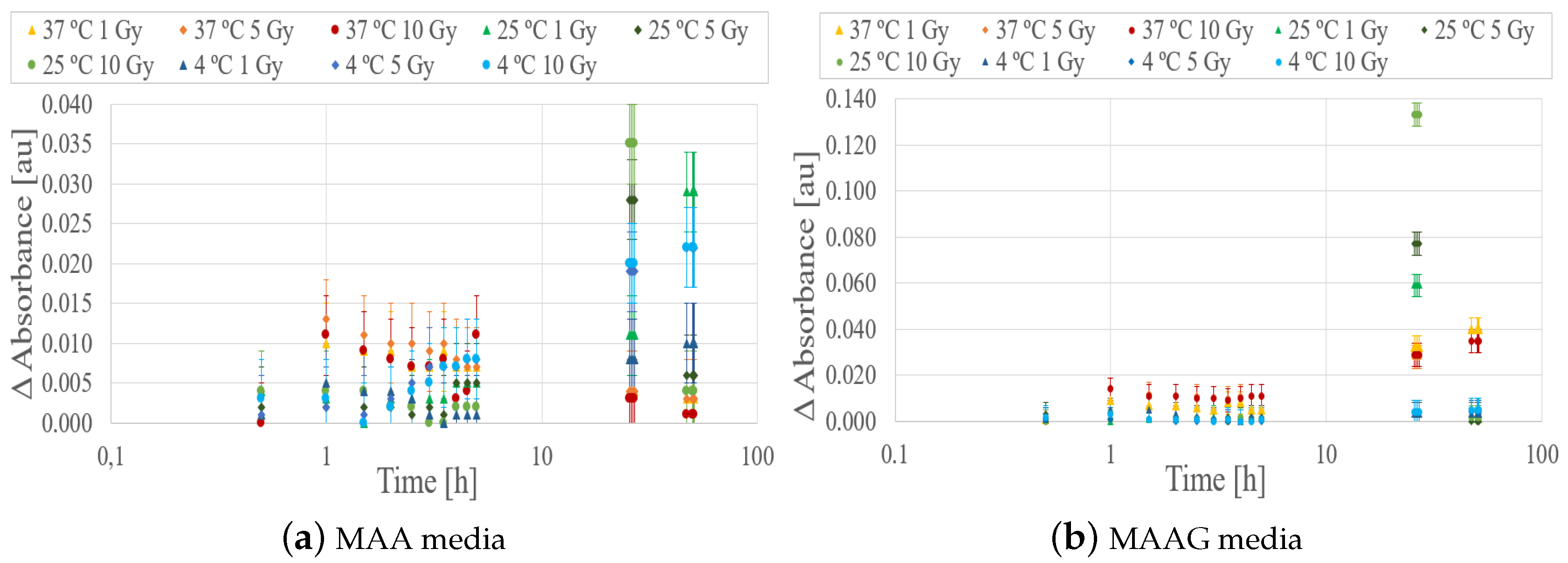

3.3. Preliminary Dose-Response Performance of Hydrogel-Based Dosimeters Infused with Escherichia Coli

Absorbance measurements were carried out on each sample before irradiation, immediately after, and over a post-irradiation period of 50 hours. The response of samples stored at 4, 25 and 37 ºC was evaluated exposing samples to doses of 1, 5 and 10 Gy for each medium. As illustrated in the

Figure 9a,b on a logarithmic scale, during the first 10 hours after irradiation, the EC strain does not exhibit a clear dose-response behavior. However, noticeable changes occur after 24 hours, contrasting with the observations made for the SA strain [

29], which displayed a marked response within 2 hours after irradiation at a specific temperature.

During the measurement process, the base cell is defined as the cell containing non-irradiated bacteria, and the changes in recorded absorbance take into account not only the medium’s composition and variations but also the growth and survival of the bacteria.

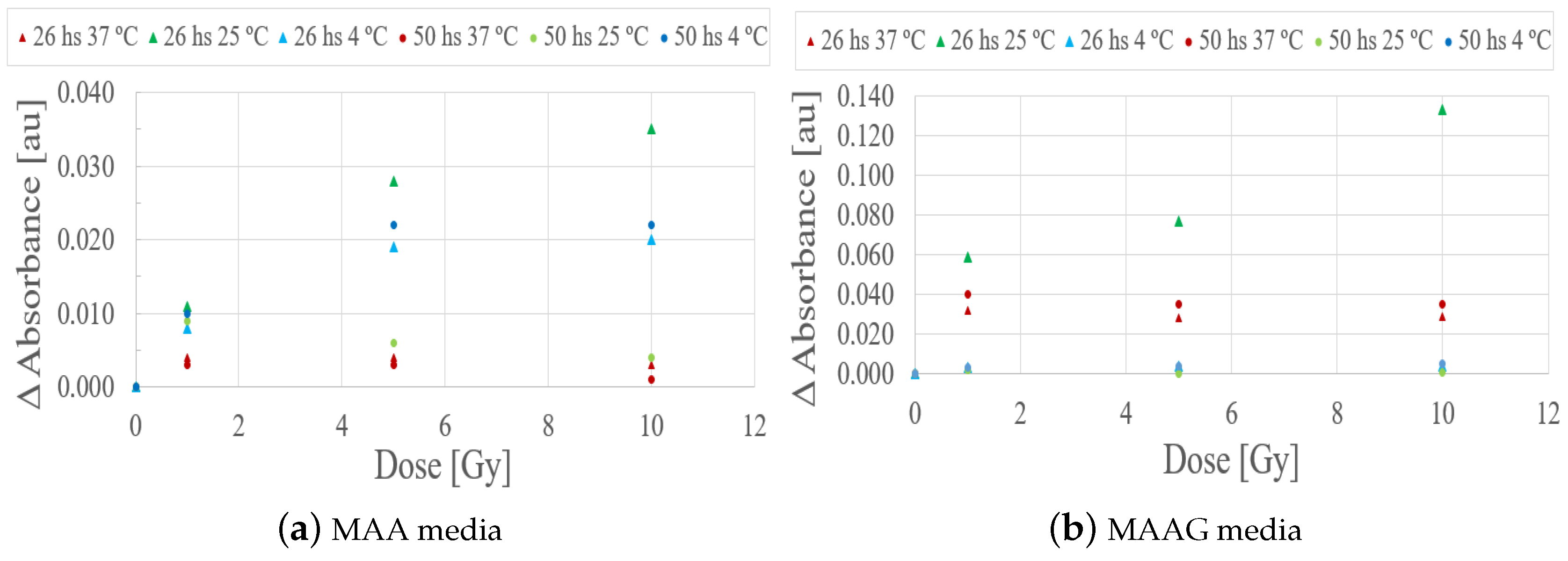

Evaluating the behavior of the studied samples at 26 and 50 hours after irradiation, as illustrated in the

Figure 10, it can be quoted that the samples stored at 4 and 37 ºC did not exhibit significant responses that could eventually be associated with a potential low sensitivity for the studied dose range. However, samples stored at 25 ºC, preliminarily showed a notable response to irradiation within a period of 26 hours. However, this trend could not be detected after 48 hours.

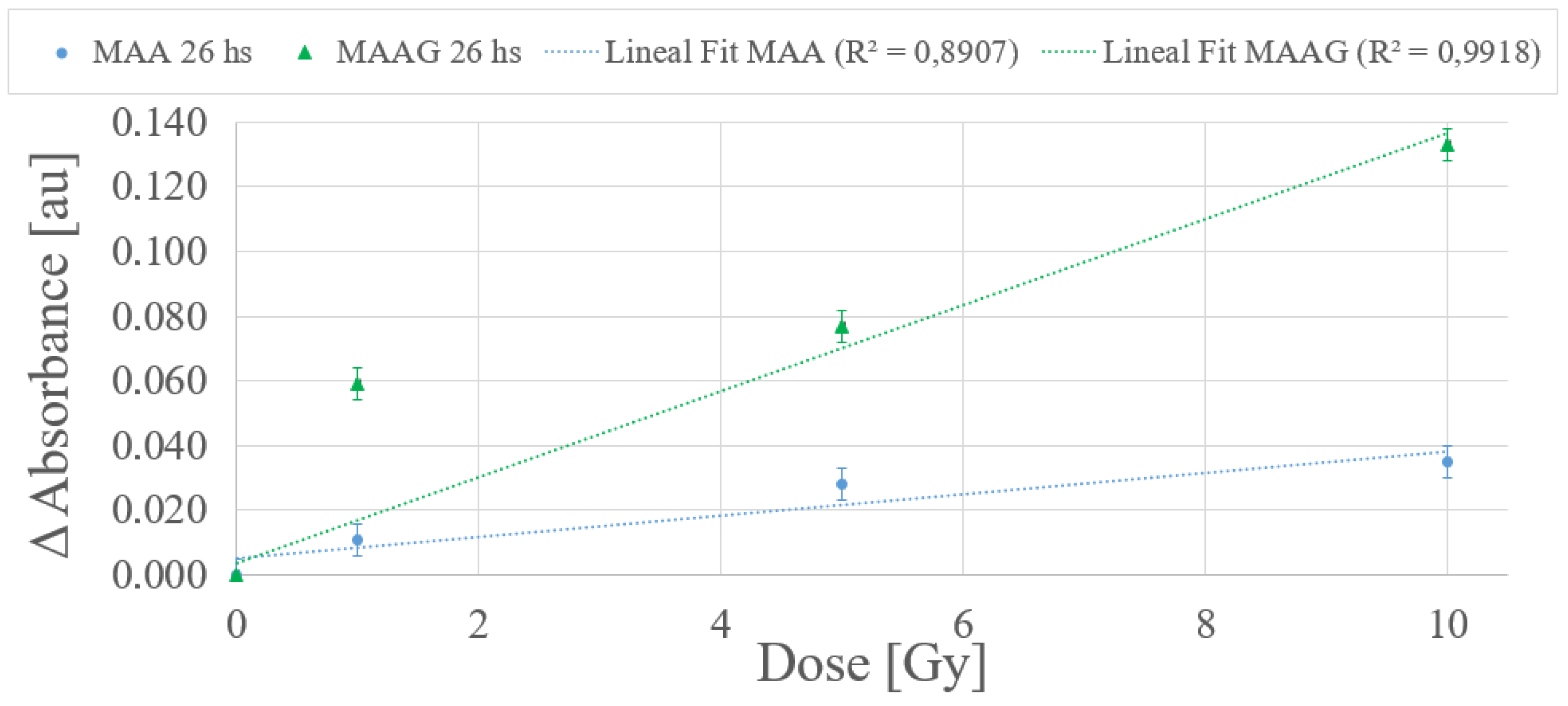

According to the dose-response trend obtained at 25 ºC, a first-order (linear) function has been proposed to fit the data for the dose range from 0 to 10 Gy for each medium.

Figure 11 depicts a typical example within the dose range of interest, with measurements carried out 26 h after irradiation. The values obtained from the linear fit correlation parameter (

) support the proposed first-order approximation for the dose-response dependence, which aligns with the commonly desirable characteristic for any dosimetry system. Thereby, it is considered that measurements obtained between 24 and 27 hours after sample irradiation demonstrate an univoque and evident response to irradiation, unlike the 2 and a half to 3 and a half hours previously reported for the SA strain.

The results reported in

Figure 11, although preliminary, may assist in verifying whether there is indeed an unequivocal correlation response to the dose. Further studies for each system, incorporating shorter dose intervals within the same range may be performed.

4. Conclusions

The present work assessed the bulk mass density of two hydrogel-based cell culture media that can be used to elaborate bacteria-infused dosimeters: i) Agar-Agar (MAA) and ii) Agar-Agar with glucose (MAAG), demonstrating also that both gels are suitable for radiation dosimetry and bacterial growth, considering the presence or absence of Staphylococcus Aureus (SA) and Escherichia Coli (EC) strains. Bulk mass density assessments were successfully conducted at different temperatures using two independent approaches: the first, based on direct measurements of mass and volume, which yielded densities comparable to those of liquid water, with uncertainties ranging between 9 and 16 %, while the second approach, employing Archimedes’ principle, produced more precise estimations with uncertainties between 0.04 and 0.08 %, thus remarking the second approach as more reliable for bulk mass density determinations of bacteria-infused hydrogels.

The minor bulk mass density differences with respect to liquid water observed in the investigated materials indicate promising performance in terms of almost negligible effects on correction requirements on the mass attenuation coefficient and stopping power for ionizing radiation dosimetry purposes. Furthermore, having bulk mass density similar to the liquid water, it could be preliminarily concluded that the proposed bacteria-infused hydrogel-based materials attain high water (soft tissue) equivalence. In addition, the viability of the systems inoculated with Escherichia Coli was evaluated for their potential application in X-ray radiation dosimetry within the range of 0 to 10 Gy. Preliminary results for the dose-response output demonstrated for the Escherichia Coli infused culture media a noticeable high linear correlation to X-ray radiation doses over the entire studied range, particularly for samples stored at 25°C. In summary, the studied systems based on hydrogels infused with Escherichia Coli (EC) strains were properly characterized in terms of the corresponding growth curve and post-irradiation bacterial survival, supporting their potential as effective dosimeters. Ongoing and future work will allow to expand the present results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.R. and M.V.; methodology: M.R., C.S.D. and M.V.; formal analysis: C.S.D.; investigation: C.S.D., M.R. and M.V., M.R.; resources: M.R., M.V. and C.S.D.; writing-original draft preparation: C.S.D., M.V. and M.R.; writing-review and editing: M.V., C.S.D., M.R.; visualization: C.S.D.; supervision: M.R. and M.V.; project administration: M.R. and M.V.; funding acquisition: M.R. and M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been partially supported by Universidad de La Frontera by projects DI21-0068 and DI21-1005, SECyT-UNC project 30820150100052CB and FONCYT project PICT 2021-GRFT1-00728.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank IFEG-CONICET for the work space and Carolina Salinas Domján is grateful for the doctoral scholarship awarded by CONICET.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| LIIFAMIRx

|

Laboratorio de Investigación e Instrumentación en Física Aplicada a la Medicina |

| |

e Imágenes de Rayos X |

| MAA |

Medium with Agar-Agar |

| MAAG |

Medium with Agar-Agar and Glucose |

| SA |

Staphylococcus Aureus |

| EC |

Escherichia Coli |

References

- International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. Tissue Substitutes in Radiation Dosimetry and Measurement. ICRU Report 1989, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C.; Ximenes Filho, R.; Vieira, J.; Tomal, A.; Poletti, M.; Garcia, C.; Maia, A. Evaluation of tissue-equivalent materials to be used as human brain tissue substitute in dosimetry for diagnostic radiology. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2010, 268, 2515–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Sabharwal, A.; Singh, B.; Sandhu, B.; Garg, R. Study of Effective Atomic Number of Muscle Tissue Equivalent Material Using Back-scattering of Gamma Ray Photons. In Proceedings of the International Journal of Advance Research in Science and Engineering, 03 2018, Vol. 07, p. 5.

- Jucius, R.A.; Kambic, G.X. Radiation Dosimetry In Computed Tomography (CT). In Proceedings of the Application of Optical Instrumentation in Medicine VI; Gray, J.E.; Hendee, W.R., Eds. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 1977, Vol. 0127, pp. 286 – 295. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.955952. [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Hintenlang, D.; Bolch, W. Tissue-equivalent materials for construction of tomography phantoms in pediatric radiology. Medical physics 2003, 30, 2072–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinase, S.; Kimura, M.; Noguchi, H.; Yokoyama, S. Development of lung and soft tissue substitutes for photons. Radiation Protection Dosimetry 2005, 115, 284–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oana, I. Craciunescu, Laurens E. Howle, S.T.C. Experimental evaluation of the thermal properties of two tissue equivalent phantom materials. International Journal of Hyperthermia 1999, 15, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, B.C.; Frimaio, A.; Barrio, R.M.; Sirico, A.C.; Costa, P.R. Comparative analysis of the transmission properties of tissue equivalent materials. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2020, 167, 108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venning, A.J.; Hill, B.; Brindha, S.; Healy, B.J.; Baldock, C. Investigation of the PAGAT polymer gel dosimeter using magnetic resonance imaging. Physics in medicine and biology 2005, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Vedelago, J.; Chacón, D.; Mattea, F.; Velásquez, J.; Pérez, P. Water-equivalence of gel dosimeters for radiology medical imaging. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2018, 141, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Macchione, M.A.; Páez, S.L.; Strumia, M.C.; Valente, M.; Mattea, F. Chemical Overview of Gel Dosimetry Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Gels 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattea, F.; Romero, M.; Vedelago, J.; Quiroga, A.; Valente, M.; Strumia, M.C. Molecular structure effects on the post irradiation diffusion in polymer gel dosimeters. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2015, 100, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedelago, J.; Mattea, F.; Valente, M. Integration of Fricke gel dosimetry with Ag nanoparticles for experimental dose enhancement determination in theranostics. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2018, 141, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariotti, V.; Gayol, A.; Pianoschi, T.; Mattea, F.; Vedelago, J.; Pérez, P.; Valente, M.; Alva-Sanchez, M. Radiotherapy dosimetry parameters intercomparison among eight gel dosimeters by Monte Carlo simulation. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2022, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keall, P.; Baldock, C. A theoretical study of the radiological properties and water equivalence of Fricke and polymer gels used for radiation dosimetry. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 1999, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ionov, L. Hydrogel-based actuators: possibilities and limitations. Materials Today 2014, 17, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A. .; A., B. Monte Carlo Calculation of Mass Attenuation Coefficients of Some Biological Compounds. Süleyman Demirel University Faculty of Arts and Science Journal of Science 2019, 14, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, H.; Marashdeh, M.; Alsuhybani, M.; Almurayshid, M. Evaluation of radiation attenuation properties of breast equivalent phantom material made of gelatin material in mammographic X-ray energies. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2024, 17, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonguc, B.T.; Arslan, H.; Al-Buriahi, M.S. Studies on mass attenuation coefficients, effective atomic numbers and electron densities for some biomolecules. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2018, 153, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, H.; Gümüs, H. Stopping power and CSDA range calculations of electrons and positronsover the 20 eV–1 GeV energy range in some water equivalent polymer gel dosimeters. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2022, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüs, H. Positron CSDA range and stopping power calculations in some human body tissues by using Lenz Jensen atomic screening function. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2022, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, M.; Ç. Tufan, M. Stopping power and range calculations in human tissues by using the Hartree-Fock-Roothaan wave functions. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2017, 140, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Moraskie, M.; Roshid, M.H.O.; O’Connor, G.; Dikici, E.; Zingg, J.M.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S. Microbial whole-cell biosensors: Current applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 191, 113359. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra, T.; Dev, S.; Banerjee, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Singh, R.; Aggarwal, S. Use of immobilized bacteria for environmental bioremediation: A review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Mei, Y.; Shi, J.; Tan, W.; Zheng, J.H. Genetically engineered oncolytic bacteria as drug delivery systems for targeted cancer theranostics. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 124, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.; Mattea, F.; Vedelago, J.; Chacón, D.; Valente, M.; Álvarez, C.I.; Strumia, M. Analytical and rheological studies of modified gel dosimeters exposed to X-ray beams. Microchemical Journal 2016, 127, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- McAuley, K.B.; Nasr, A.T. Fundamentals of gel dosimeters. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2013, 444. [Google Scholar]

- Baldock, C.; Deene, Y.D.; Doran, S.; Ibbott, G.; Jirasek, A.; Lepage, M.; McAuley, K.B.; Oldham, M.; Schreiner, L.J. Polymer gel dosimetry. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2010, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas Domján, C.; Romero, M.R.; Valente, M. Development and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus-hydrogel-based radiation dosimeter. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2024, 212, 111455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, T.; Mathur, A.; Kukuruzovic, R.; McGuigan, M. Hypotonic vs isotonic saline solutions for intravenous fluid management of acute infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Chen, Y. Effects of X-Ray Irradiation on the Microbial Growth and Quality of Flue-Cured Tobacco during Aging. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2015, 111, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zendejas-Manzo, G.S.; Avalos-Flores, H.; Soto-Padilla, M.Y. Microbiología general de Staphylococcus aureus: Generalidades, patogenicidad y métodos de identificación. Revista Biomédica 2014, 25, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Blount, Z.D. The Natural History of Model Organisms: The unexhausted potential of E. coli. eLife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D.; Krieg, N.; Staley, J.; Garrity, G.; Boone, D.; De Vos, P.; Goodfellow, M.; Rainey, F.; Schleifer, K. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology: Volume Two The Proteobacteria Part B The Gammaproteobacteria; Springer New York, NY, 2005. [CrossRef]

-

EVO Manual; YXLON, 2016.

- NIST. NIST Standard Reference Database 69: NIST Chemistry WebBook, Thermophysical Properties of Fluid Systems, Isobaric Properties for Water. https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/fluid/, 2008.

- Wagner, W.; Pruß, A. The IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 2002, 31, 387–535, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jpr/article-pdf/31/2/387/16672775/387_1_online.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, I.; Kolditz, D.; Langner, O.; Kalender, W.A. A formulation of tissue- and water-equivalent materials using the stoichiometric analysis method for CT-number calibration in radiotherapy treatment planning. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2012, 57, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Singh, M.; Mishra, S. Tissue-equivalent materials used to develop phantoms in radiation dosimetry: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 7170–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hironaka, I.; Iwase, T.; Sugimoto, S.; ichi Okuda, K.; Tajima, A.; Yanaga, K.; Mizunoe, Y. Glucose Triggers ATP Secretion from Bacteria in a Growth-Phase-Dependent Manner. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2013, 79, 2328–2335, [https://journals.asm.org/doi/pdf/10.1128/aem.03871-12].. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).