1. Introduction

As a comprehensive and strategic approach, sustainability addresses current needs without jeopardizing the capacity of future generations to fulfill their own requirements. This concept is underpinned by three fundamental pillars: environmental stewardship, economic viability, and social equity. It emphasizes the prudent management of resources, the minimization of environmental impacts, and the implementation of long-term ecological practices. In essence, sustainable development seeks to establish resilient systems that sustain productivity and enhance quality of life while remaining adaptable to evolving circumstances [

1]. Consequently, this integrative perspective fosters innovation and efficiency, reinforcing a commitment to the preservation of natural ecosystems, the promotion of economic advancement, and the improvement of social welfare [

2].

With the increasing industrial-environmental impacts, conserving resources, and ensuring long-term energy security, sustainable electricity production becomes a crucial aspect to mitigate. It is clear with the rapidly growing global population and increasing energy demands, that traditional fossil fuel-based energy sources pose significant threats to the environment, contributing to climate change and resource depletion [

3]. Sustainable energy production may address environmental concerns by reducing dependency on finite resources alongside promoting economic resilience and stabilizing energy costs.

In recent years, particularly over the last decade, wind energy has emerged as a prominent renewable energy source, characterized by its impressive capacity factor, which can reach between 40% and 50% in certain projects. This development aligns with the environmental regulations governing installation projects, reflecting the sustainable performance objectives set forth by multilateral organizations such as the United Nations (UN) [

4,

5]. According to the Global Wind Energy Council report [

6], transitioning to numerous renewable energy sources, such as wind power, can be dramatically impactful in reducing carbon emissions and minimizing ecological footprints in producing electricity.

Besides, the energy sector in general has undergone a significant transformation driven by advancements in ML. Such technologies have shown immense potential in optimizing various facets of energy generation, particularly within renewable energy resources such as wind power. Being said, ML techniques can steer sustainability within energy systems by enhancing efficiency, accuracy, and predictive capabilities by enabling more precise forecasting of energy production and consumption patterns [

7,

8]. A successful predictive maintenance plan has been achieved by identifying patterns and trends from various sources that human analysts might overlook, facilitating a more balanced and resilient energy supply [

9]. No doubt that with the effective integration of such techniques into the electrical grid, energy usage can be optimized dynamically by adjusting supply and demand in real-time, thus can reduce energy wastage and improve overall sustainability [

10].

Thus, in our research, we present a case study that demonstrates a sample utilization of Machine Learning techniques in developing predictive maintenance plans for wind energy systems. In this case study, we have shown the benefits of using those techniques in terms of predicting the possible failures and prioritizing the parts to be maintained or replaced, which also helps save significant number of resources in terms of manpower, cost, time, etc. to achieve sustainability and successful strategic planning.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Importance of Using ML and AI from Management Perspective

The role of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) in management is becoming increasingly crucial, given their ability to refine decision-making processes and improve operational efficiencies. Organizations can harness large datasets to detect patterns and trends that traditional analytical approaches might overlook. As noted by Brynjolfsson and McAfee [

11], the capability to analyze data in real-time enables businesses to quickly adjust to market fluctuations, thus encouraging a more responsive strategic orientation. Moreover, the implementation of predictive analytics equips firms to project future market conditions and consumer preferences, facilitating more strategic and informed decision-making [

12].

Furthermore, the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence technologies is instrumental in achieving a competitive advantage by automating routine tasks and refining resource allocation. Perifanis and Kitsios [

13] assert that intelligent systems can streamline operational processes, permitting human resources to focus on more strategic and high-level initiatives instead of mundane operational responsibilities. This reallocation not only elevates overall productivity but also strengthens the organization’s capacity for innovation. Additionally, AI-based tools can facilitate automated planning and decision-making by simulating a range of strategic alternatives, thereby enabling managers to evaluate the potential consequences of various strategies with greater accuracy [

14]. Several recent research also highlighted the importance of utilization digital technologies including AI to increase effectiveness and efficiency of different managerial functions and processes in the digital transformation of organization, as well as industries and cities from a broader perspective [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) encourages a culture of decision-making driven by data, which is imperative for effective strategic management in the contemporary era. Organizations that leverage these technologies are better equipped to derive insights from data analytics, thereby informing their strategic decisions and enhancing performance outcomes. As noted by Loureiro et al. [

22], this shift towards data-centric approaches not only improves operational effectiveness but also aligns with the broader movement of digital transformation in the business landscape. Therefore, the incorporation of AI and ML is not merely a technological improvement; it is a critical element of modern strategic management practices that can significantly influence the success and sustainability of organizations.

2.2. Wind Energy Systems as Sustainable Energy Source

The utilization of wind energy spans several centuries, with its origins traceable to ancient societies that employed windmills for tasks such as grain milling and water pumping. The contemporary evolution of wind energy systems commenced in the late 19th century, marked by the creation of the wind turbine [

23]. In 1888, Charles F. Brush constructed the first of its kind large-scale wind turbine in Cleveland, Ohio, featuring a rotor diameter of 17 meters and generating 12 kW of electrical power [

24]. Throughout the years, innovations in materials, aerodynamics, and technology have markedly enhanced the efficiency and dependability of wind turbines. The establishment of offshore wind farms in the latter part of the 20th century further augmented the capabilities of wind energy, capitalizing on the stronger and more stable winds found over oceanic expanses [

25].

The proliferation of wind farms has received notable support from European and emerging nations as a strategic initiative to sustain competitiveness in the production of durable consumer goods and essential commodities. The wind energy industry has experienced remarkable growth, with a 1.8% increase in installed capacity in 2021 compared to 2020, culminating in a total of 94 GW. The distribution of this capacity is notable, with onshore wind farms accounting for 77% and offshore farms for 23%. These figures underscore the resilience of the energy sector amid significant economic challenges faced by various nations in the second decade of the 21st century [

4].

However, this sector encounters significant challenges, including a pronounced reliance on adequate infrastructure in proximity to energy generation sites, as well as regional regulatory and technical issues that may obstruct energy production and distribution. Furthermore, the upkeep of wind turbines presents a critical limitation that could hinder sustained growth due to elevated industrial expenses [

26,

27,

28]. The variability in wind speeds necessitates the implementation of effective energy storage systems and backup generation to maintain grid stability and reliability. Moreover, issues related to visual aesthetics, noise pollution, and impacts on wildlife require meticulous site selection and environmental considerations.

On the other hand, the infrastructure that underpins wind turbines and energy systems represents a sophisticated and intricate network aimed at effectively and dependably capturing wind energy. Central to this infrastructure are the wind turbines, which have undergone substantial advancements in both design and technology over the years. Contemporary wind turbines are composed of several essential elements, including the rotor, main shaft, generator, nacelle, and various critical control electronics that oversee turbine functionality and efficiency [

29]. In addition to individual turbines, the wind energy infrastructure includes entire wind farms, which are groups of turbines strategically arranged to optimize energy generation. These wind farms are linked through internal electrical networks and are integrated into larger transmission grids via substations [

30].

Various scholarly works have been directed towards filling the primary gaps recognized in the studies related to offshore wind turbine maintenance. A notable contribution is made by Ilić et al. [

31], who delve into preventive maintenance, addressing failure identification, maintenance techniques, and the optimization of maintenance schedules. In addition, Morales et al. [

32] put forth a model that employs mathematical optimization to improve the scheduling of maintenance for offshore wind turbines. Similarly, Costa et al. [

33] focus on the maintenance of offshore wind turbines, revealing shortcomings in monitoring, inspection, and fault diagnosis methodologies. They stress the necessity of integrating advanced technologies and tools, including drones, robots, and remote sensors, to improve maintenance practices. Furthermore, Chen et al. [

34] have pointed out the vital role of preventive and corrective maintenance for offshore wind turbines, highlighting the insufficient availability of accurate performance and longevity data. In general, authors emphasize the significance of a systematic maintenance approach that considers reliability, safety, and cost-effectiveness, as well as the reliability of the data.

2.3. Utilization of ML in the Energy Sector

Initially, while AI refers to the simulation of human intelligence in programmed machines that can learn, and solve problems, ML is also defined as a subset of AI that enables systems to automatically learn from experience and previous data and improve without being explicitly programmed [

35]. Generally, AI and ML are used across various industries for different tasks. To mention a few; data analysis, natural language processing, image and speech recognition, anomaly detection, automated control systems and complex decision-making processes, and advanced predictive analytics can be considered among the most commonly used applications of AI and ML [

36]. Indeed, ML impacted various industry sectors by improving decision-making and enhancing productivity. For instance, ML algorithms optimize supply chains, predict maintenance needs, enhance quality control in the manufacturing sector, improve diagnostic imaging for patients in the healthcare sector, and used for fraud detection, risk management, and algorithmic trading through FinTech applications [

37].

Utilization of such ML applications for the operation and maintenance of systems in the energy sector is also getting more and more substantial. Usage of ML in such systems supports real-time optimization that can significantly enhance grid stability and reduce the need for energy storage solutions, which are often costly and resource-intensive [

38]. In addition, a prediction system based on ML can predict energy demand, allowing for more efficient energy distribution and planning. Those predictions that can be calculated through the advanced algorithms in ML applications help in reducing peak load pressures and accordingly, minimize the operational costs associated with energy generation and distribution [

39].

On the other hand, ML can also transform how we manage and sustain renewable energy infrastructures. One may argue that an extremely significant application of utilizing ML in this area is predictive maintenance [

4]. In technical terms, it utilizes advanced algorithms to analyze data collected from sensors embedded in wind turbines and other renewable energy equipment. Since it is a data-driven approach, continuous monitoring of equipment health and performance will be achieved, enabling early detection of potential failures, especially before any serious escalation. Thus, ML algorithms can facilitate timely maintenance interventions by identifying anomalies, predicting failures, preventing unexpected downtimes, and ensuring a more reliable energy supply [

40]. One may argue that traditional maintenance practices based on fixed schedules or reactive responses to failures can be inefficient and costly, and therefore the ability to predict maintenance would make substantial cost savings. More specifically, predictive maintenance driven by ML can reduce maintenance costs, since it only targets those components that genuinely need attention. This optimized approach also minimizes unnecessary disruptions to energy production [

4].

Given the complex and interconnected structure of wind energy systems, which include vital components, it is imperative to implement effective maintenance to optimize turbine performance and extend their operational lifespan. Maintenance strategies should prioritize a proactive and predictive approach, aimed at detecting and correcting potential issues prior to their escalation into significant challenges [

41]. Traditional reactive maintenance practices can result in prolonged downtime and higher costs, making predictive maintenance, enhanced by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), a more attractive alternative. The implementation of such systems can greatly improve operational efficiency, particularly through the anticipation of equipment malfunctions and the strategic planning of maintenance tasks [

42]. By adopting a proactive maintenance strategy, engineers are able to assess and predict issues such as blade degradation and gearbox failures using data collected from sensors installed on wind turbines. This approach has the potential to lower maintenance expenses by as much as 30% and decrease downtime by 50% in certain instances [

43].

Research focused on the maintenance of wind turbines has introduced computational models that enhance the precision of Maintenance Planning and Control strategies by as much as 94%. This advancement plays a significant role in optimizing the associated costs of these processes. The offshore setting, in contrast to onshore locations, presents challenges in accessibility to wind turbines and accelerates their degradation, resulting in increased operational and maintenance expenses [

44,

45,

46].

Furthermore, by relying on ML predictions, we can schedule regular and timely maintenance, which helps prevent minor issues from turning into major problems [

47]. Predictive maintenance significantly extends the life of wind energy assets, reduces the need for frequent equipment replacements, and minimizes the environmental impact. Such smarter and more responsive maintenance practices enhance the overall reliability and resilience of the energy grid and in return, ensure a steady and uninterrupted supply of renewable energy, which is crucial for meeting the growing energy demands in an environmentally sustainable manner [

48]. On the other end of this ML-driven maintenance analytics, manufacturers can leverage this data to improve the robustness and efficiency of new turbines for future design and development, ultimately reducing needed maintenance [

4]. With such a continuous feedback loop between operational data and technological innovation, the entire renewable energy sector will be dramatically improved. The application of ML in wind energy grid maintenance will not only advance sustainability by promoting efficient resource use and extending equipment life but also ensure the reliability and resilience of renewable energy systems [

49].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Analysis Strategy

Based on the increasing importance of wind energy as renewable energy alternatives, we decided to increase the operational efficiency of a wind turbine system by establishing a strategy for predictive maintenance. In the scope of this strategy, we assume that the cost of repairing a generator is much less than the cost of replacing it, and the cost of inspection is less than the cost of repair. In support of this strategy, we applied machine learning models to improve the machinery/processes by predicting the failures correctly. For this purpose, we used secondary data that was previously collected. Data reflected the generator failure of wind turbines using measures from several different sensors installed on the generator. To support the high security of the data and the relevant systems, data was provided and used in ciphered format.

Our purpose in this study was to develop a Machine Learning Model to predict the Failures correctly, in order to reduce the maintenance cost and increase the operational efficiency. First, we have conducted Univariate analyses to better understand the data. Then, to be able to recommend a suitable approach for better predictive maintenance, we developed a predictive ML model, by utilizing different Cross-validation, Hyperparameter tuning. As discussed by Cabral et al. [

4] and suggested by Ahmad et al. [

50], we used Python programming to conduct the ML analyses and incorporated in our predictive models several techniques, including Logistic Regression, Bagging (i.e., BaggingCLassifier, Decision Tree, Random Forest), Boosting (i.e., Adaboost, Gradient Boosting, XGBoosting).

Our objective is to build various classification models, tune them, and find the best one that will help identify failures so that the generators could be repaired or replaced before failing/breaking to reduce the overall maintenance cost. Hence, as our data analysis strategy, first we defined the classification model as follows:

True positives (TP) are failures correctly predicted by the model. These will result in repair costs.

False negatives (FN) are real failures where there is no detection by the model. These will result in replacement costs.

False positives (FP) are detections where there is no failure. These will result in inspection costs.

In this analysis, our goal is to increase True Positives (TP), while reducing False Negatives (FN). Thus, we will focus on finding the model to increase Recall coefficient, also called Sensitivity, which is defined as the proportion of TP that are correctly identified (TP / (TP + FN)).

Those wind energy technologies and equipment had several different sensors that had been fitted across different machines to collect data related to various environmental factors (temperature, humidity, wind speed, etc.) and additional features related to various parts of the wind turbine (gearbox, tower, blades, break, etc.). Through utilization of those sensors, the cost of operation and maintenance would be much lower if component failure patterns were predicted, and faulty components were replaced before they failed; and thus predictive maintenance strategy would be very beneficial to predict degradation of components and their future capability.

3.2. Overview of Dataset and Data Preprocessing

In our study, we used a secondary dataset, which originally belonged to the company that was responsible for the maintenance of the wind energy generator systems. Dataset contained the data related to the generator failures of wind turbines and measures from different sensors, which we call “Parts” in our analysis. However, data was in the ciphered version, and named as Part-1, Part-2, up to Part-40, as well as the target variable that shows the system generator failures as 1 (failure) or 0 (No Failure).

We separated the data into two datasets, as Training and Test datasets. In the training dataset, there were 20,000 rows and 41 columns, whilst there were 5,000 rows and 41 columns in the Test dataset. In both datasets, all variables from Part-1 to Part-40 were in the float type. Only the target variable, which was the state of failure, was Integer type. Variables could have negative and positive values. The lowest value in the training dataset was -20.37 for Part-16 and the highest value was 23.63 for Part-32.

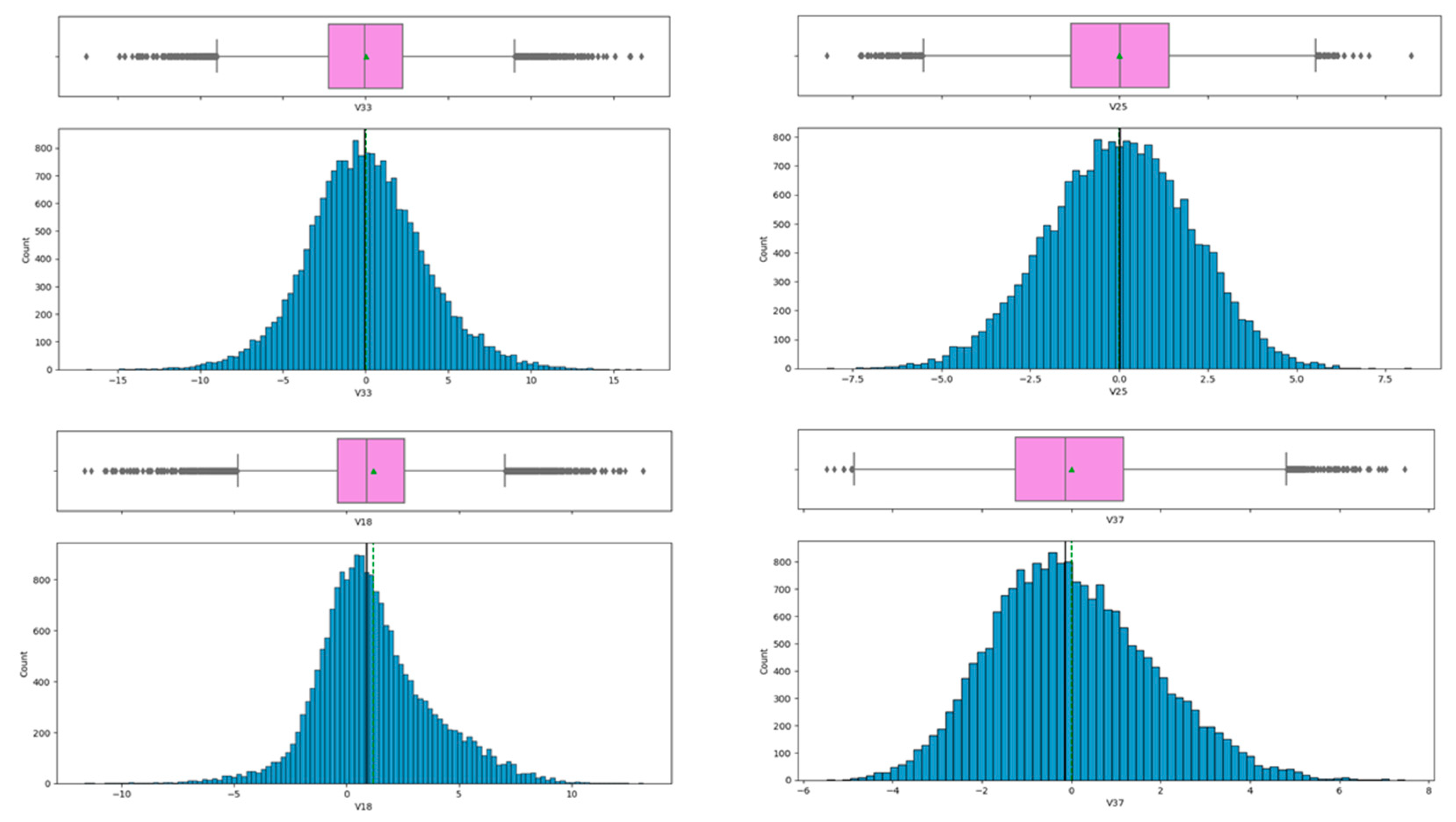

We used Boxplot and Histogram to conduct the univariate analysis of the data by variables. Almost all variables had the shape of Normal Distribution. Besides, mean and median values were very close to each other for most variables, which made the distributions symmetric, and not skewed to left or right. The exceptions for variables having symmetrical distribution were Part-18, Part-29 and Part-37, which had right (positive) skewed (mean is greater than median) distribution. Please see

Figure 1 for some examples for Boxplot and Histogram.

In the Training dataset, there were 18,890 rows having 0 (No Failure) and 1,110 rows having 1 (Failure) for the target variable. On the other hand, in the Test dataset, there were 4,718 rows having 0 (No Failure) and 282 rows having 1 (Failure) for the target variable.

There were no duplicate values in neither Training nor Test datasets. In the Training data set, there were only 18 missing values for Part-1 and Part-2, whilst there were only 5 missing values for Part-1, and 6 missing values for Part-2 in the Test dataset. Missing values were filled with the median value of the relevant variables following the k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) distance-based median procedure approach [

51,

52]. Outliers were also checked for all the variables in both datasets. Although there were some outlier values for the variables, we did not remove any values from the dataset, as there was no outlier value so far from the rest of the data. As we had a separate Test dataset, following the approach recommended by Ahmad et al. [

50], we divided the Training dataset into «train» and «validation» sets using the 75-25 ratio in order to prevent the data leakage. The reason for this ratio was the fact that the rows in the Test dataset were 25% of the Training dataset.

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance

To find out the best performing machine learning model to maximize the True Positive and minimize False Negatives, we developed models using Cross-validation and Hyperparameter Tuning. ML Models which were used and compared in this analysis include the following bagging and boosting models: Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Bagging, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Adaboost, and XGBoost.

We used Recall score as model performance parameter, as the decision was made based on the highest Recall score on test dataset. First, we employed and tested the models with data in Training & Validation dataset and got the performance scores on Test Dataset to make the final decision on the models. However, number of failures and not-failures were not so balanced in the dataset. Thus, we decided to test the models utilizing Oversampling and Undersampling techniques. For oversampling, we used Synthetic Minority Over Sampling Technique (SMOTE) and for undersampling we used Random Undersampling [

53]. The cross-validation performance of the models with oversampled and undersampled data are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Based on the cross-validation performance for oversampled and undersampled data, XGBoost turned out to be the best model that yielded highest Recall score both for training (0.99 for oversampled and 0.91 for undersampled) and validation (0.85 for oversampled and 0.88 for undersampled) data.

Afterwards, we applied Hyperparameter Tuning for better configuration of the models (Ahmad et al., 2024). The models that we tuned were as follows: Adaboost using oversampled data, Random Forest using undersampled data, Gradient Boosting using oversampled data, and XGBoost using oversampled data. For the final performance scores of the tuned models for Training, Validation and Test data are presented on the following

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Based on models’ performance on Test data, XGBoost model turned out to be the best model that yielded the maximum Recall score (0.87). It should also be noted that recall scores that were close to each other and far from 1, indicated that the model did not overfit.

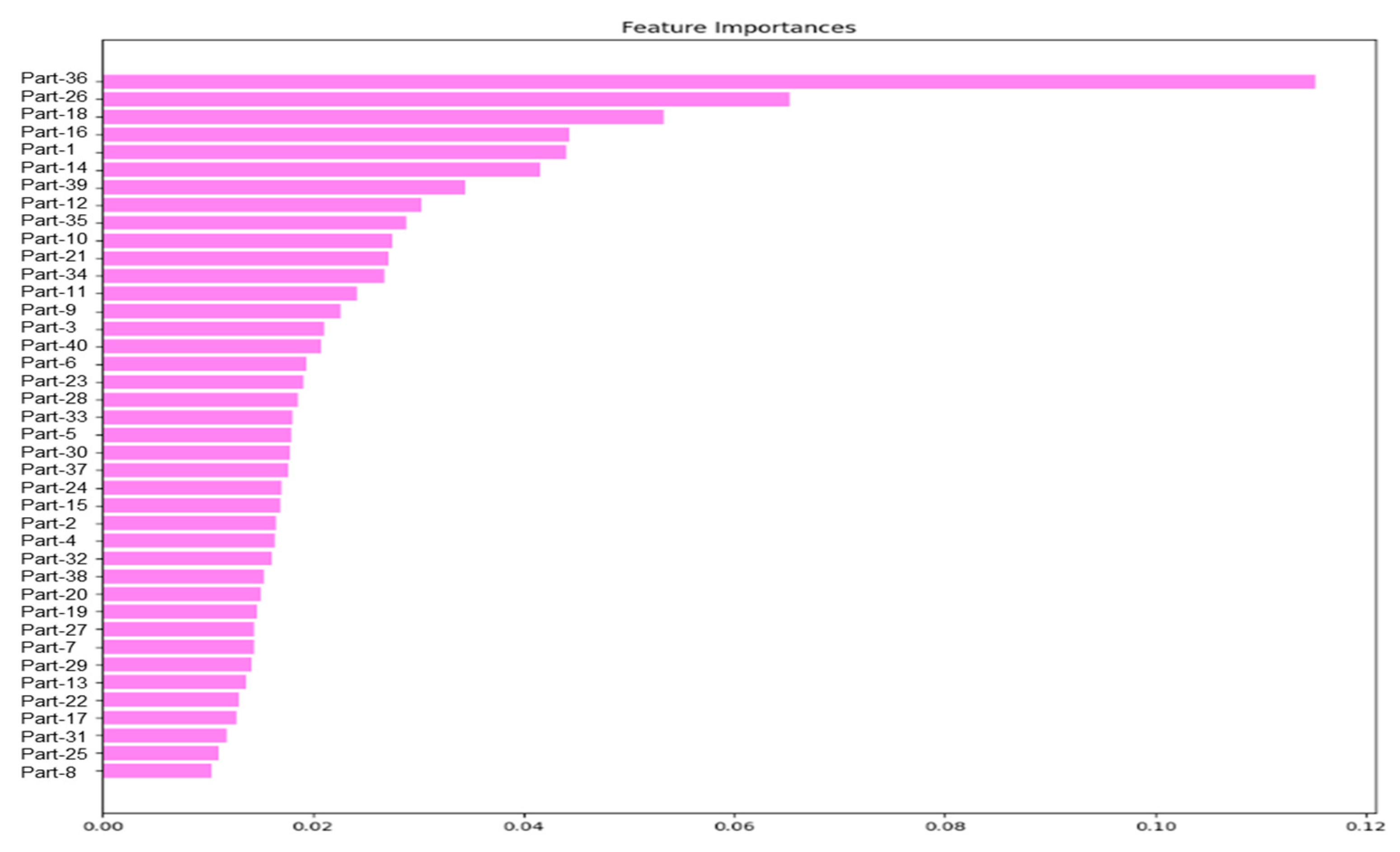

As the next step, we conducted the Feature Importance analysis of the best ML model, XGBoost Classifier with hyperparameter tuning. This analysis is conducted to reveal the most significant variables that play a crucial role in finding and estimating the failures. Please find the results in

Figure 2.

4.2. Results of ML Analysis

At the end of the analyses, Tuned XGBoost model has turned out to be the best model having the highest Recall value that correctly predicts the Failures. Based on the purpose of decreasing the cost of predictive maintenance, we decided to choose the model that maximizes Recall score that maximize True Positives and minimize False Negatives.

Based on the results and importance analysis of the best ML model, Tuned XGBoost, the most important features are ranked as follows. It should be noted that Part-36 is significantly more important in estimating the failure compared to the rest of the parts.:

Part-36 (Negative correlation with Failure – Decreasing values of Part-36 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-26 (Negative correlation with Failure – Decreasing values of Part-26 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-18 (Negative correlation with Failure – Decreasing values of Part-18 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-16 (Positive correlation with Failure – Increasing values of Part-16 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-1 (Positive correlation with Failure – Increasing values of Part-1 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-14 (Positive correlation with Failure – Increasing values of Part-14 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-39 (Negative correlation with Failure – Decreasing values of Part-39 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-12 (Negative correlation with Failure – Decreasing values of Part-12 results in higher Failure chance)

Part-35 (Negative correlation with Failure – Decreasing values of Part-35 results in higher Failure chance)

Based on the results from the best ML model, following might be the most important recommendations for the predictive maintenance of the system that we analyzed:

As the components Part-36, Part-26 and Part-18 are the most important ones in predicting the failure, and all have negative correlation with failure, lower values (especially low negative values) measured from those components will most probably lead to failure. Thus, we recommend system engineers be more careful and plan to repair the generator, if they detect a decrease in the measurement of the components Part-36, Part-26, Part-18.

As the components Part-16, Part-1 and Part-14 are the second most important group of parts in predicting the failure, and all have positive correlation with failure, higher values (especially high positive values) measured from those components will most probably lead to failure. Thus, we recommend system engineers be more careful and plan to repair the generator, if they detect an increase in the measurement of the components Part-16, Part-1 and Part-14.

Since the components Part-39, Part-12, and Part-35 are the third most important group of parts in predicting the failure, and all have negative correlation with failure, lower values (especially low negative values) measured from those components will most probably lead to failure. Thus, we recommend system engineers be more careful and plan to repair generator, if they detect a decrease in the measurement of the components Part-39, Part-12, and Part-35.

5. Discussion

This paper primarily aimed to investigate the role of machine learning in establishing a predictive maintenance system for wind turbine generators and its consequences for strategies of utilization of artificial intelligence and business analytics in the renewable energy sector, which is among the most important fields for achieving sustainability. For our case study, we utilized Jupyter Notebook, a dynamic platform for Python users, to create machine learning algorithms. The data employed in this study was derived from a secondary dataset that was previously established. Data reflected the generator failure of wind turbines using measures from several different sensors and components installed on the generator. To support the high security of the data and the relevant systems, data was provided and used in ciphered format.

During the analysis, we employed a variety of machine learning models, notably including Logistic Regression, Bagging (i.e., BaggingCLassifier, Decision Tree, Random Forest), Boosting (i.e., Adaboost, Gradient Boosting, XGBoosting). In our data analysis strategy, first of all, we defined the classification model as follows:

True positives (TP) are failures correctly predicted by the model. These will result in repair costs.

False negatives (FN) are real failures where there is no detection by the model. These will result in replacement costs.

False positives (FP) are detections where there is no failure. These will result in inspection costs.

Thus, our goal was to increase True Positives (TP), while reducing False Negatives (FN). Hence, we have focused on finding the model to increase Recall coefficient, also called Sensitivity, which is defined as the proportion of TP that are correctly identified (TP / (TP + FN)).

Performance assessments have revealed that the TunedXGBoost algorithm exhibits the highest recall value, followed by Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Logistic Regression, Bagging and AdaBoost, with Decision Tree showing the least recall value.

5.1. Managerial and Practical Implications

The incorporation of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) into predictive maintenance strategies for renewable energy systems, especially in the context of wind energy, carries substantial managerial implications that can significantly improve operational efficiency and reliability [

54]. By utilizing sophisticated algorithms to scrutinize data from sensors and historical maintenance logs, managers are equipped to foresee equipment failures prior to their occurrence, thus reducing downtime and lowering maintenance expenses. Thus, artificial intelligence is fundamentally altering the landscape of the renewable energy industry by improving infrastructure maintenance, optimizing energy production, and enabling the seamless integration of renewable resources into the electrical grid. The sophisticated analytics, predictive insights, and optimization strategies offered by AI are vital for achieving international renewable energy goals. As the technology of AI progresses, its role in shaping the renewable energy sector will become increasingly significant, fostering a transition towards a more sustainable and environmentally friendly future. By utilizing the strengths of AI, we can hasten the move towards renewable energy solutions, ensuring a viable planet for future generations [

55].

Research by [

49] indicates that such predictive analytics not only extend the operational lifespan of vital components but also foster a more anticipatory maintenance approach, transitioning from a reactive to a preventive maintenance model. This transition is in harmony with strategic goals aimed at maximizing asset utilization and enhancing return on investment, which are critical for sustainable practices within the renewable energy industry [

56].

Utilization of AI and ML techniques and methods in the energy sector and systems encompasses a variety of strategic and operational dimensions. Beyond the technological aspects, there is a need for comprehensive policy frameworks and strategic management practices that support the deployment and scaling of AI and ML solutions in the energy sector [

57]. Effective policy frameworks can incentivize investments in renewable energy technologies and facilitate the integration of AI-driven solutions into existing energy infrastructures, which will contribute one more step towards developing the human-centric and resilient energy systems. The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in predictive maintenance significantly improves decision-making processes for managers. These technologies offer real-time insights into the functioning of wind turbines, allowing managers to allocate resources more efficiently and prioritize maintenance tasks according to the importance of various system components. Oh et al [

56] emphasize that the capacity to analyze extensive datasets facilitates the detection of trends and anomalies that may elude conventional analytical methods. This approach to data-driven decision-making not only boosts operational efficiency but also aids in strategic planning by guiding investment choices related to technology enhancements and maintenance scheduling, ultimately leading to optimized system performance.

Furthermore, the implementation of predictive maintenance, driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies, can also yield substantial advancements in safety and regulatory compliance within the renewable energy industry. By accurately forecasting potential equipment failures, organizations can effectively manage the risks linked to malfunctions, thus protecting personnel and preserving the integrity of infrastructure. According to Aragon-Correa et al. [

58], compliance with environmental regulations is essential for sustainable practices, and predictive maintenance supports this compliance by ensuring that equipment operates within safe limits. Therefore, the managerial ramifications of integrating predictive maintenance through AI and ML not only bolster operational and financial performance but also further the strategic aims of safety and sustainability in renewable energy systems.

Additionally, strategic management practices can ensure that these technologies are implemented in ways that maximize their impact on sustainability and operational efficiency [

59]. In conclusion, the application of AI and ML in wind-based renewable energy systems presents a transformative opportunity to enhance sustainability and operational efficiency. The importance of sustainability in electricity production, particularly through renewable sources like wind energy, cannot be overstated. AI and ML offer powerful tools for predictive maintenance, optimizing energy production, and fostering a more sustainable and resilient energy sector [

60]. As we advance toward Industry 5.0, the integration of these technologies will be crucial in developing human-centric, sustainable, and resilient energy systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E., W.D., K.A.J. and V.S.; Data curation, A.E. and W.D.; Formal analysis, A.E. and W.D.; Investigation, A.E. and K.A.J.; Methodology, A.E. and W.D.; Project administration, A.E. and W.D.; Resources, A.E. and W.D.; Software, A.E. and W.D.; Supervision, A.E.; Validation, A.E., W.D., K.A.J., V.S., and M.R.; Visualization, A.E., W.D., K.A.J., V.S., and M.R.; Writing – original draft, A.E., W.D., and K.A.J.; Writing – review & editing, A.E., W.D., K.A.J., V.S., and M.R.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as the study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable as the study did not involve any human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business: Introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organization Environment 2016, 29, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, S. BP Statistical Review of World Energy; BP Plc.: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, E.L.S.; Gonzalez, M.O.A.; Vidal, P.C.J.; Junior, J.F.C.; Vasconcelos, R.M.; Melo, D.C.; Morais, R.L.L.; Neto, J.A. Optimization models for operations and maintenance of offshore wind turbines based on artificial intelligence and operations research: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Business and Management 2024, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook. 2019, Retrieved from https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/98909c1b-aabc-4797-9926-35307b418cdb/WEO2019-free.pdf.

- GWEC. GWEC Global Wind Report; Global Wind Energy Council Publications: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Drakaki, M.; Karnavas, Y.L.; Tziafettas, I.A.; Linardos, V.; Tzionas, P. Machine learning and deep learning-based methods toward industry 4.0 predictive maintenance in induction motors: State of the art survey. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management 2022, 15, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Axsen, J.; Sorrell, S. Promoting novelty, rigor, and style in energy social science: Towards codes of practice for appropriate methods and research design. Energy Research Social Science 2018, 45, 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.P.; Soares, F.A.; Vita, R.; Francisco, R.D.P.; Basto, J.P.; Alcalá, S.G. A systematic literature review of machine learning methods applied to predictive maintenance. Computers Industrial Engineering 2019, 137, 106024. [Google Scholar]

- Forootan, M.M.; Larki, I.; Zahedi, R.; Ahmadi, A. Machine learning and deep learning in energy systems: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H. Analytics at Work: Smarter Decisions, Better Results; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perifanis, N.A.; Kitsios, F. Investigating the influence of artificial intelligence on business value in the digital era of strategy: A Literature review. Information 2023, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.F.S.; Laurindo, F.J.B.; Spinola, M.M.; Goncalves, R.F.; Mattos, C.A. The strategic use of artificial intelligence in the digital era: Systematic literature review and future research directions. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 57, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badillo, I.; Tejeida, R.; Morales, O.; Briones, A. A systems science / cybernetics perspective on contemporary management in supply chains. In Applications of Contemporary Management Approaches in Supply Chains (ch.7, pp. 139–158); Tozan, H., Ertürk, A., Eds.; InTech Open Access Publishers: Check Republic, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bošković, G.; Cvetanović, A.M.; Jovičić, N.; Jovanović, A.; Jovičić, M.; Milojević, S. Digital technologies for advancing future municipal solid waste collection services. In Digital Transformation and Sustainable Development in Cities and Organizations (ch.8, pp. 167–192); Theofanidis, F., Abidi, O., Erturk, A., Colbran, S., Coskun, E., Eds.; IGI Global Publishers: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Erturk, A.; Colbran, S.; Coskun, E.; Theofanidis, F.; Abidi, O. Convergence of Digitalization, Innovation, and Sustainable Development in Business; IGI Global Publishers: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Herath, S.K.; Herath, L.M. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable development (SD) in the digital age. In Convergence of Digitalization, Innovation, and Sustainable Development in Business (ch.8, pp. 162–184); Erturk, A., Colbran, S., Coskun, E., Theofanidis, F., Abidi, O., Eds.; IGI Global Publishers: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kargas, A.; Gialeris, E.; Filios, S.; Komisopoulos, F.; Lymperiou, A.; Salmon, I. Evaluating the progress of digital transformation in Greek SMEs. In Digital Transformation and Sustainable Development in Cities and Organizations (ch.4, pp. 81–105); Theofanidis, F., Abidi, O., Erturk, A., Colbran, S., Coskun, E., Eds.; IGI Global Publishers: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Bravo, M.; Labella-Fernandez, A. Sustainable smart cities: a step beyond. In Digital Transformation and Sustainable Development in Cities and Organizations (ch.6, pp. 125–140); Theofanidis, F., Abidi, O., Erturk, A., Colbran, S., Coskun, E., Eds.; IGI Global Publishers: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Theofanidis, F.; Abidi, O.; Erturk, A.; Colbran, S.; Coskun, E. Digital Transformation and Sustainable Development in Cities and Organizations; IGI Global Publishers: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J.; Tussyadiah, I. Artificial intelligence in business: State of the art and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research 2021, 129, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwell, J.F.; McGowan, J.G.; Rogers, A.L. Wind Energy Explained: Theory, Design, and Application; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hau, E.; Renouard, H. Wind Turbines: Fundamentals, Technologies, Application, Economics (Vol. 2); Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, B. Renewable Energy: Physics, Engineering, Environmental Impacts, Economics & Planning, 5th ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, N.; Irawan, C.A.; Jones, D.F.; Menachof, D. A multi-criteria port suitability assessment for developments in the offshore wind industry. Renewable Energy 2017, 102, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baagøe-Engels, V.; Stentoft, J. Operations and maintenance issues in the offshore wind energy sector. International Journal of Energy Sector Management 2016, 10, 245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.A.T.; Chou, S.Y.; Yu, T.H.K. Developing an exhaustive optimal maintenance schedule for offshore wind turbines based on risk-assessment, technical factors and cost-effective evaluation. Energy 2022, 249, 123613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riziotis, V.A.; Voutsinas, S.G.; Politis, E.S.; Chaviaropoulos, P.K. Aeroelastic stability of wind turbines: The problem, the methods and the issues. Wind Energy: An International Journal for Progress and Applications in Wind Power Conversion Technology 2004, 7, 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Bórawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A.; Jankowski, K.J.; Dubis, B.; Dunn, J.W. Development of wind energy market in the European Union. Renewable Energy 2020, 161, 691–700. [Google Scholar]

- Ilić, M.; Hie, L.; Joo, J.Y. Efficient coordination of wind power and price-responsive demand - Part II: Case studies. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2011, 26, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, R.; Chicano, F.; Khomh, F.; Antoniol, G. Efficient refactoring scheduling based on partial order reduction. Journal of Systems and Software 2018, 145, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.M.; Orosa, J.A.; Vergara, D.; Fernandez-Arias, P. New tendencies in wind energy operation and maintenance. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 1386. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X. Learning deep representation of imbalanced SCADA data for fault detection of wind turbines. Measurement 2019, 139, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydia, M.; Selvakumar, A.I.; Kumar, S.S.; Kumar, G.E.P. Advanced algorithms for wind turbine power curve modeling. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2013, 4, 827–835. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Vol. 4, No. 4, p. 738); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, I.H.; Frank, E.; Hall, M.A.; Pal, C.J. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques, 4th ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Yu, T. A new generation of AI: A review and perspective on machine learning technologies applied to smart energy and electric power systems. International Journal of Energy Research 2019, 43, 1928–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Yuan, J.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Y. Review on wind power development and relevant policies in China during the 11th Five-Year-Plan period. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 1907–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, I.S.; Ustun, T.S. A survey on behind the meter energy management systems in smart grid. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 72, 1208–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Cinar, Z.M.; Abdussalam, N.A.; Zeeshan, Q.; Korhan, O.; Asmael, M.; Safaei, B. Machine learning in predictive maintenance towards sustainable smart manufacturing in industry 4.0. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, A.; Li, W. The prediction and diagnosis of wind turbine faults. Renewable Energy 2011, 36, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Review on probabilistic forecasting of wind power generation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 32, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Falani , S.Y.A.; González, M.O.A.; Barreto, F.M.; Toledo, J.C.; Torkomian, A.L.V. Trends in the technological development of wind energy generation. International Journal of Technology Management and Sustainable Development 2020, 19, 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Sobral, J.; Soares, C.G. Review of condition-based maintenance strategies for offshore wind energy. Journal of Marine Science and Application 2019, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Y.; Steel, J.A. A progressive study into offshore wind farm maintenance optimization using risk-based failure analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 42, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Bompard, E.F. Big data analytics in smart grids: A review. Energy Informatics 2018, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi, A. Maximizing Solar PV Energy Penetration Using Energy Storage technology. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15, 866–870. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Qian, L.; Mao, B.; Huang, C.; Huang, B.; Si, Y. A data-driven design for fault detection of wind turbines using Random Forests and XGboost. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 21020–21031. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Ali, M.A.; Hasan, M.R.; Mobo, F.D.; Rai, S.I. Geospatial machine learning and the power of Python programming: Libraries, tools, applications, and plugins. In Ethics, Machine Learning, and Python in Geospatial Analysis (Ch. 10, pp. 223–253); Galety, M.G., Natarajan, A.K., Gedefa, T.F., Lemma, T.D., Eds.; IGI Global Publishers: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.; Ayub, M.S.; Arora, S.; Khan, M.A. An investigation of the imputation techniques for missing values in ordinal data enhancing clustering and classification analysis validity. Decision Analytics Journal 2023, 9, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kwon, O. Missing values and optimal selection of an imputation method and classification algorithm to improve the accuracy of ubiquitous computing applications. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2015, 538613. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Mu, W.; Song, Y.; Dou, J. An improved and random synthetic minority oversampling technique for imbalanced data. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 248, 108839. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, H.; Pillai, A.C.; Friedrich, D.; Collu, M.; Dawood, T.; Johanning, L. A review of predictive and prescriptive offshore wind farm operation and maintenance. Energies 2022, 15, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.M.; Ibekwe, K.; Ilojianya, V.; Sonko, S. AI in renewable energy: A review of predictive maintenance and energy optimization. International Journal of Science and Research Archive 2024, 11, 718–729. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.Y.; Joung, C.; Lee, S.; Shim, Y.B.; Lee, D.; Cho, G.E.; Jang, J.; Lee, I.Y.; Park, Y.B. Condition-based maintenance of wind turbine structures: A state-of-the-art review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 204, 114799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Fu, C.; Yang, S. Big data driven smart energy management: From big data to big insights. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 56, 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Aragon-Correa, J.A.; Marcus, A.A.; Vogel, D. The effects of mandatory and voluntary regulatory pressures on firms’ environmental strategies: A review and recommendations for future research. Academy of Management Annals 2020, 14, 339–365. [Google Scholar]

- Pfenninger, S.; Hirth, L.; Schlecht, I.; Schmid, E.; Wiese, F.; Brown, T.; Davis, C.; Gidden, M.; Heinrichs, H.; Heuberger, C.; Hilpert, S. Opening the black box of energy modelling: Strategies and lessons learned. Energy Strategy Reviews 2018, 19, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, D.; Wang, H. Data-driven methods for predictive maintenance of industrial equipment: A survey. IEEE Systems Journal 2019, 13, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).