Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

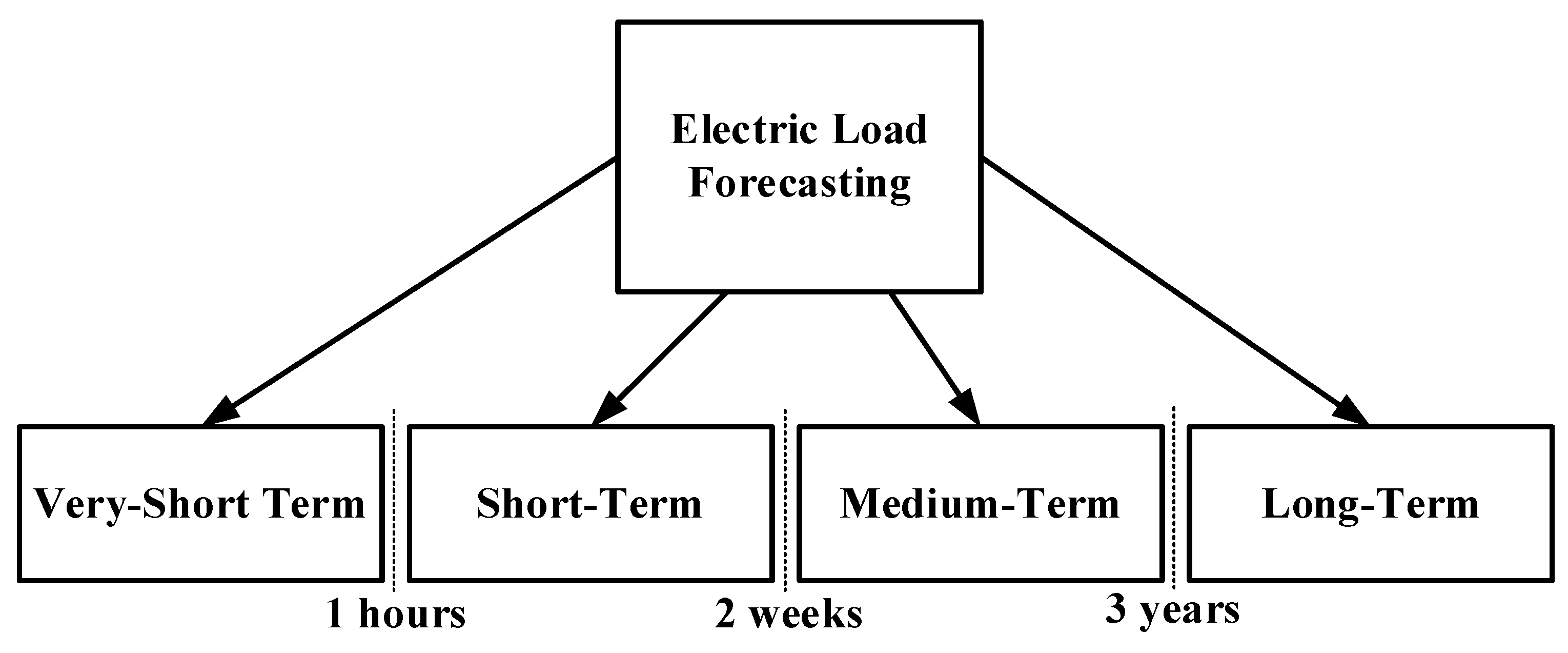

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Material and Methods

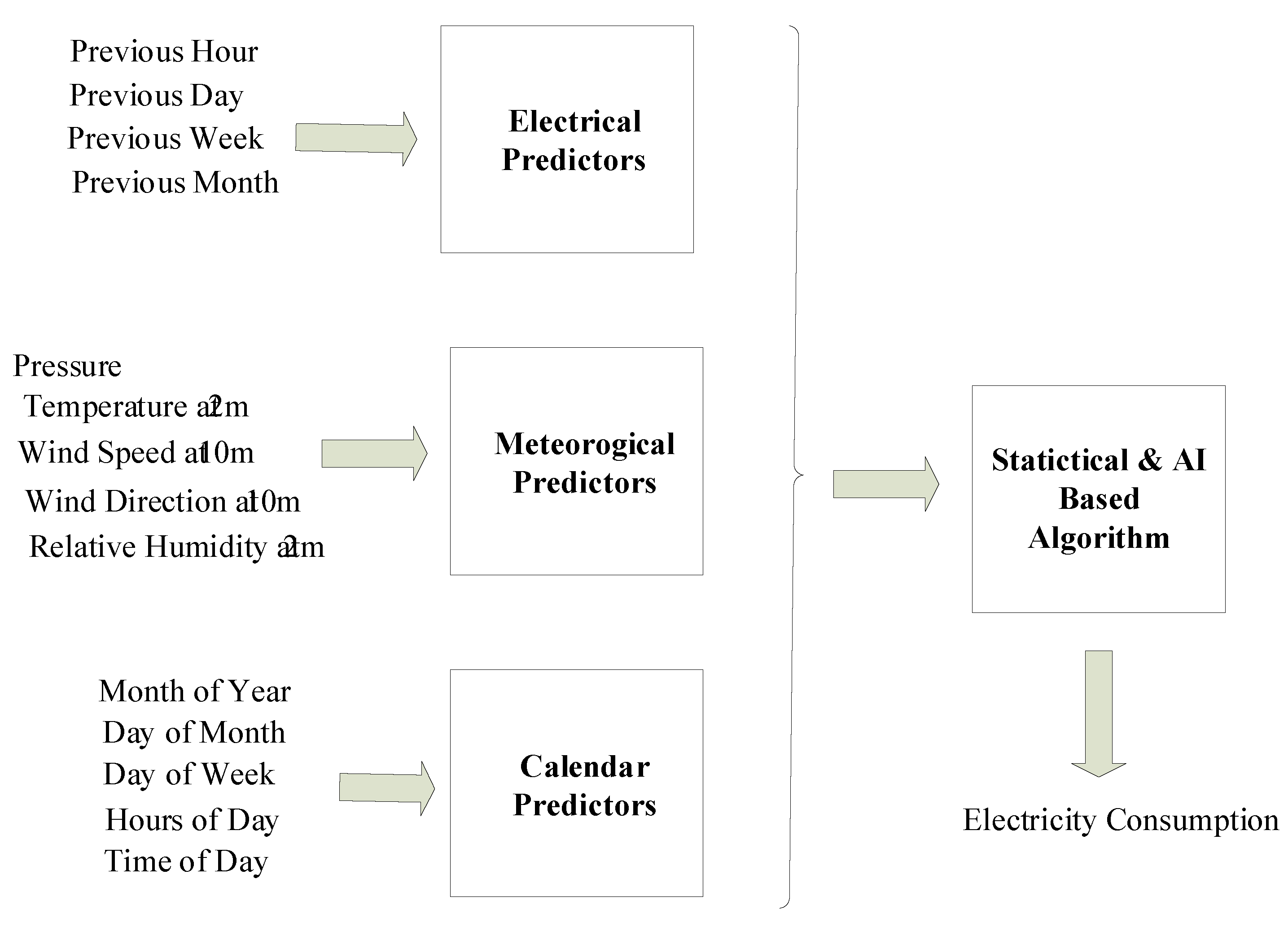

3.1. Material

3.1.1. Data Source and Acquisition

3.1.2. Properties of Dataset

3.2. Methods of Forecasting

3.2.1. Multiple Linear Regression

3.2.2. Group Method of Data Handling

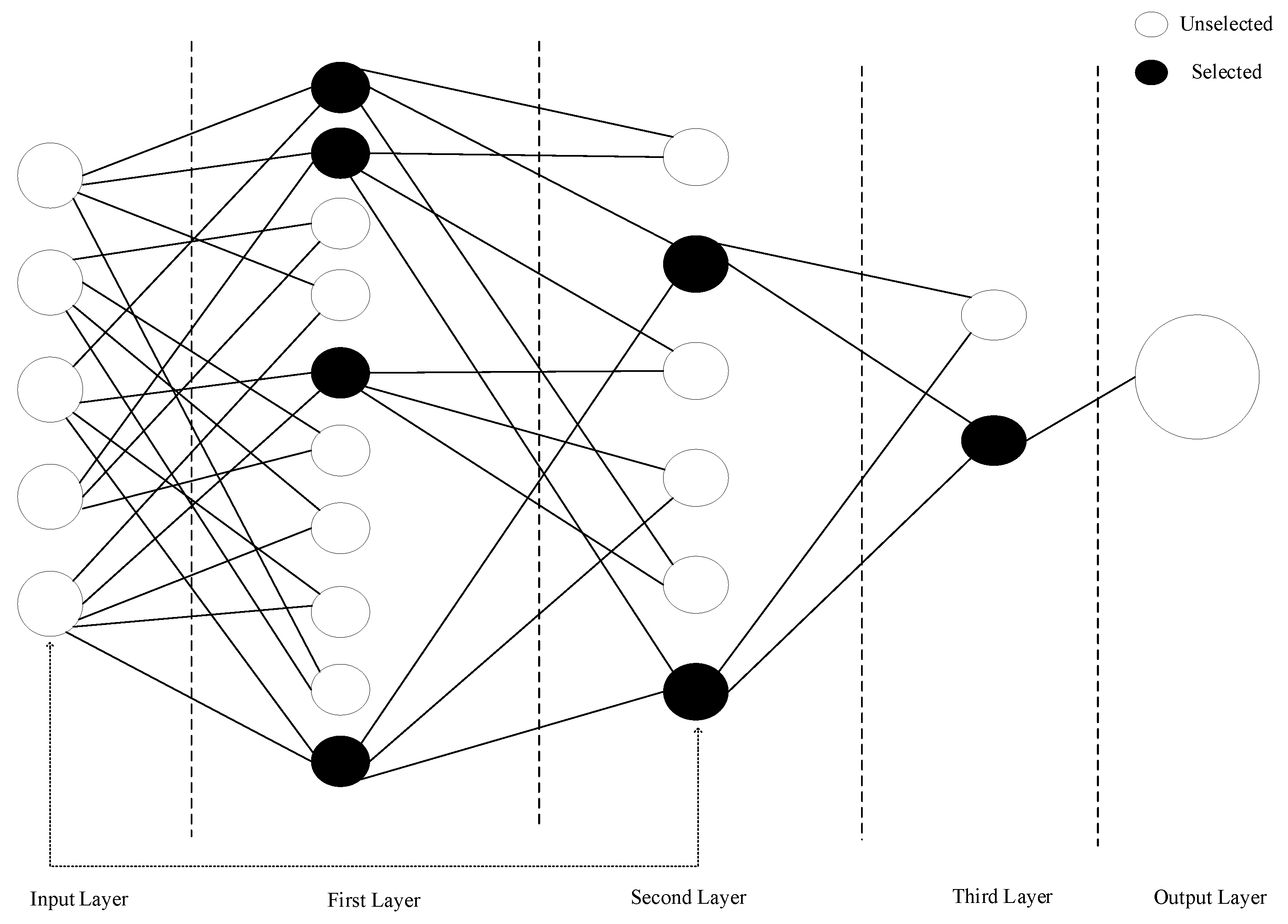

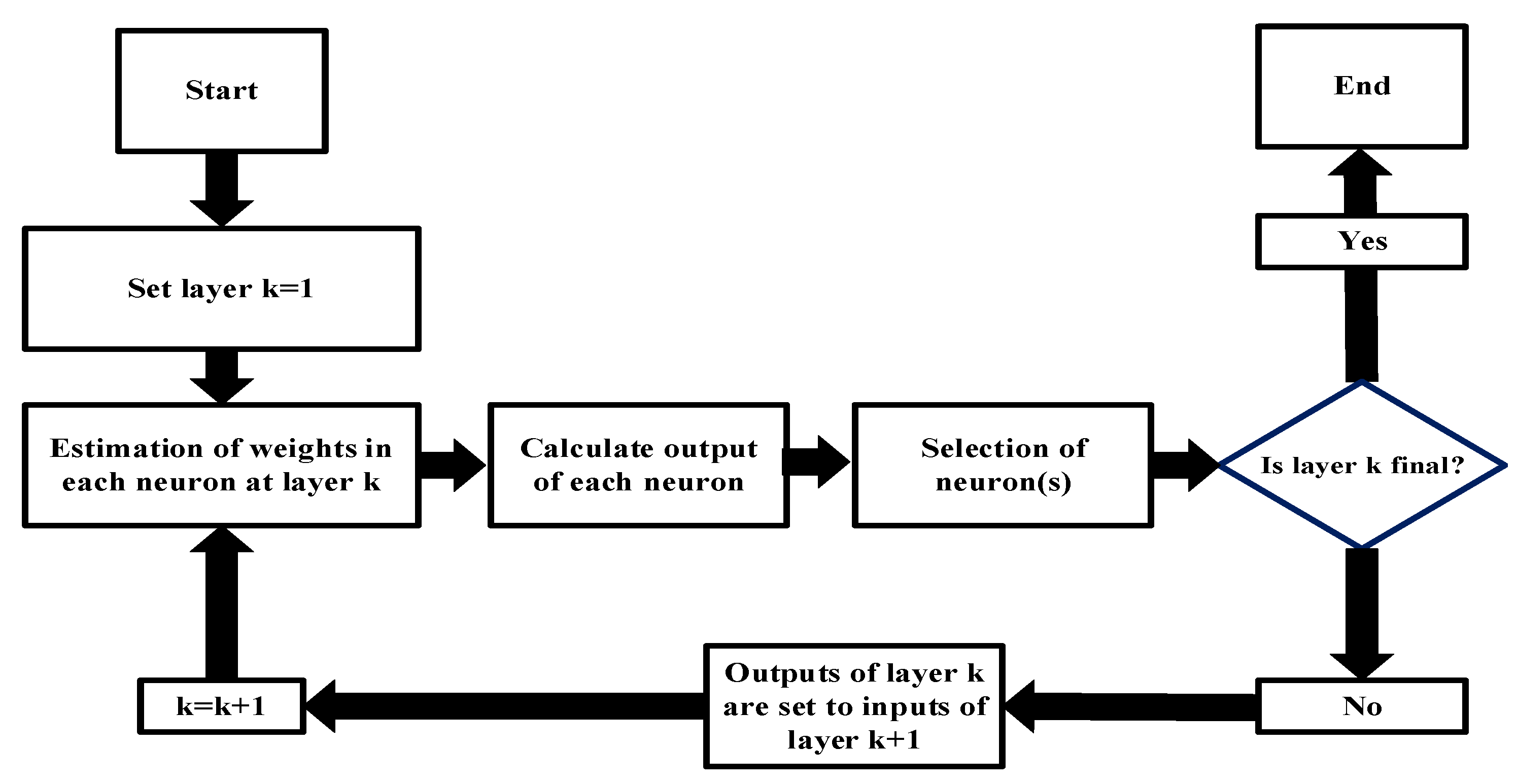

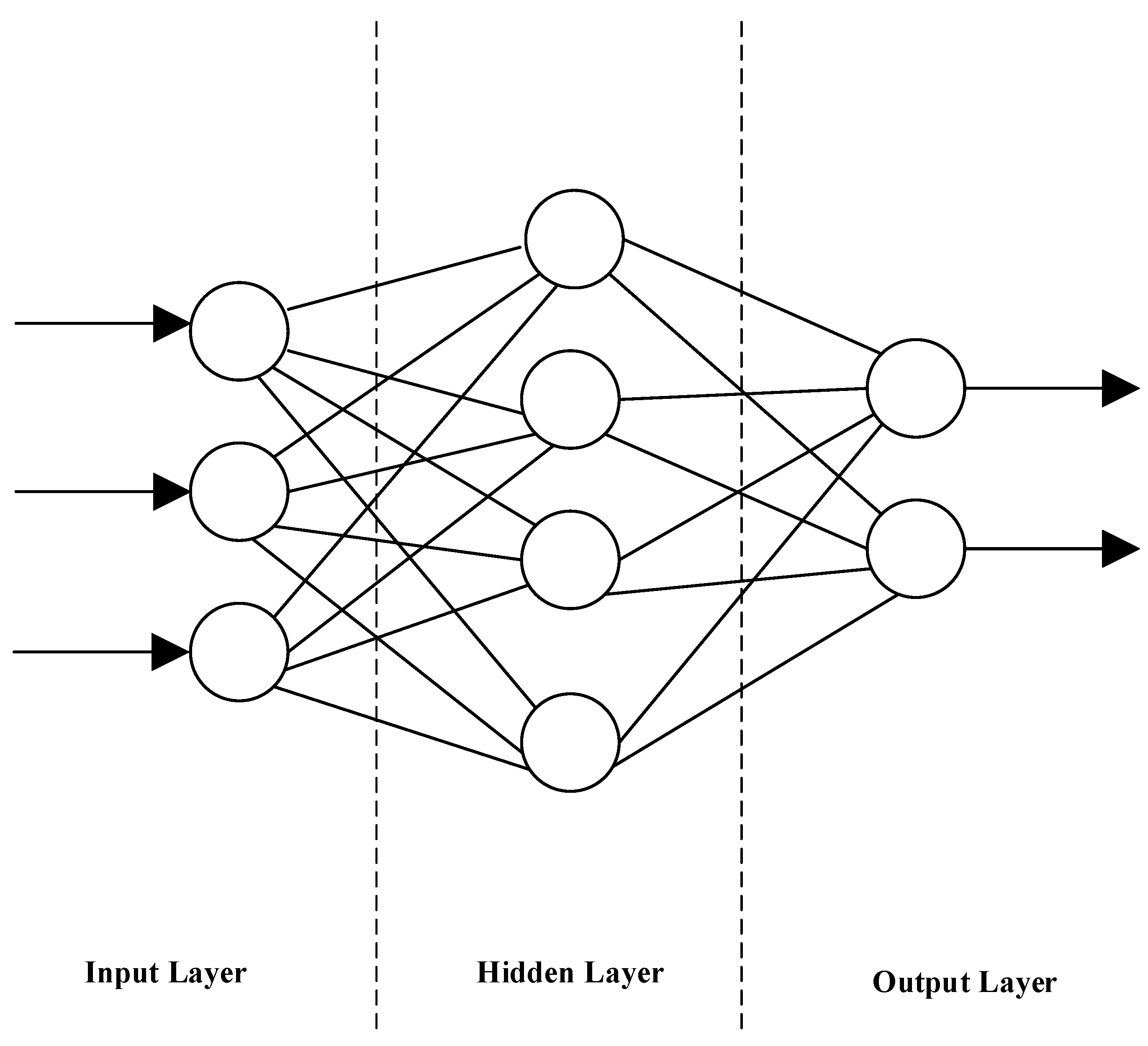

3.2.3. Multi-Layered Perceptron Neural Network (MLPNN)

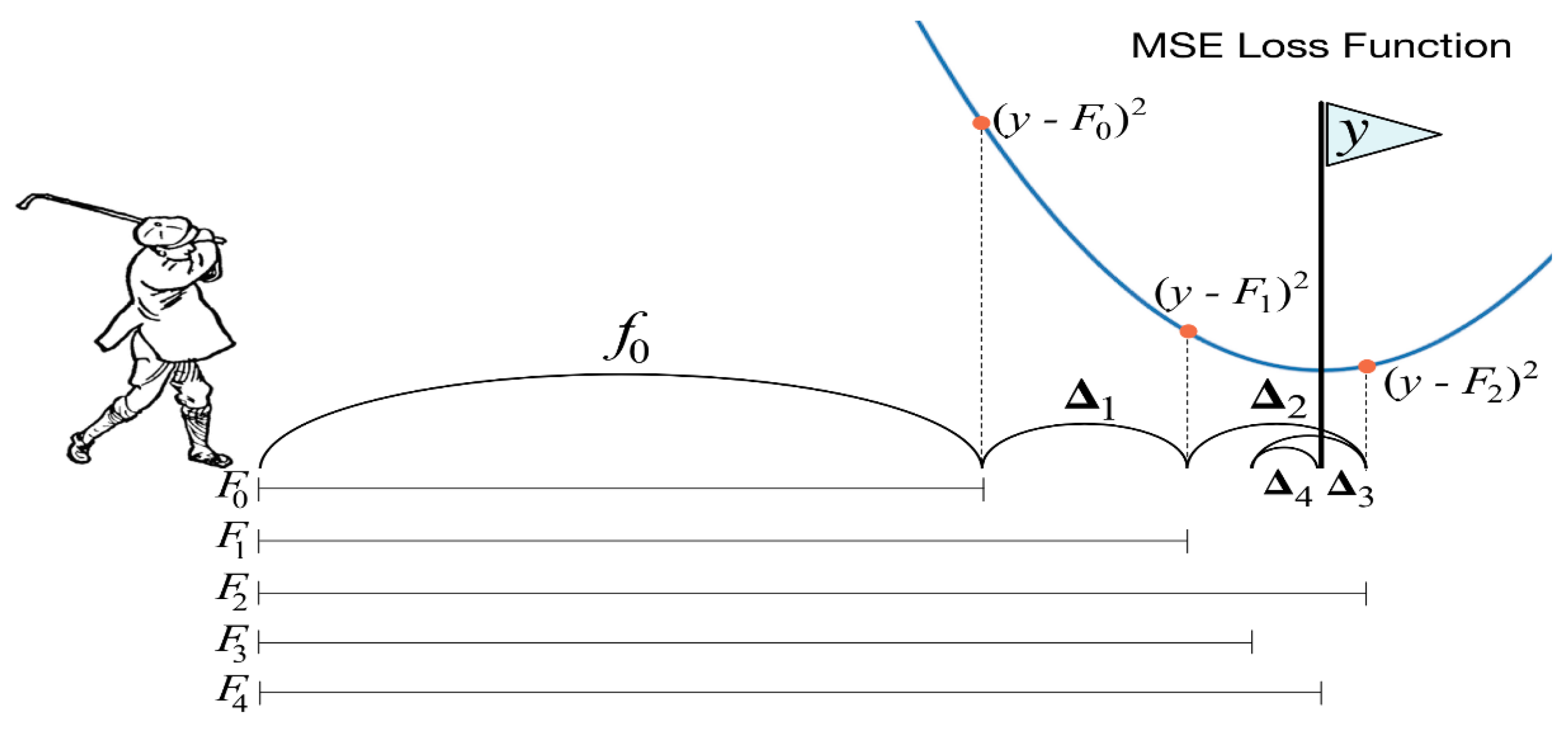

3.2.4. Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT)

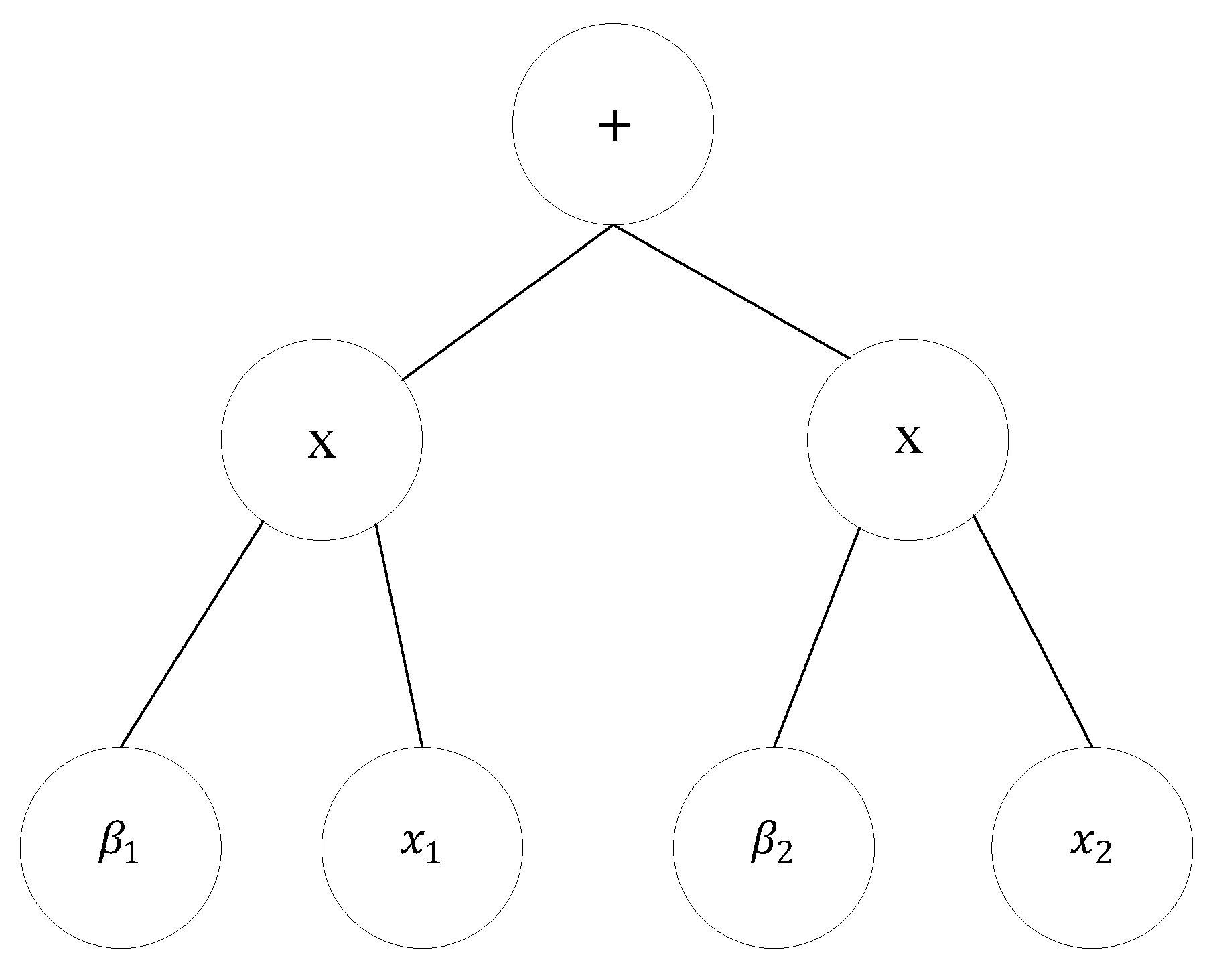

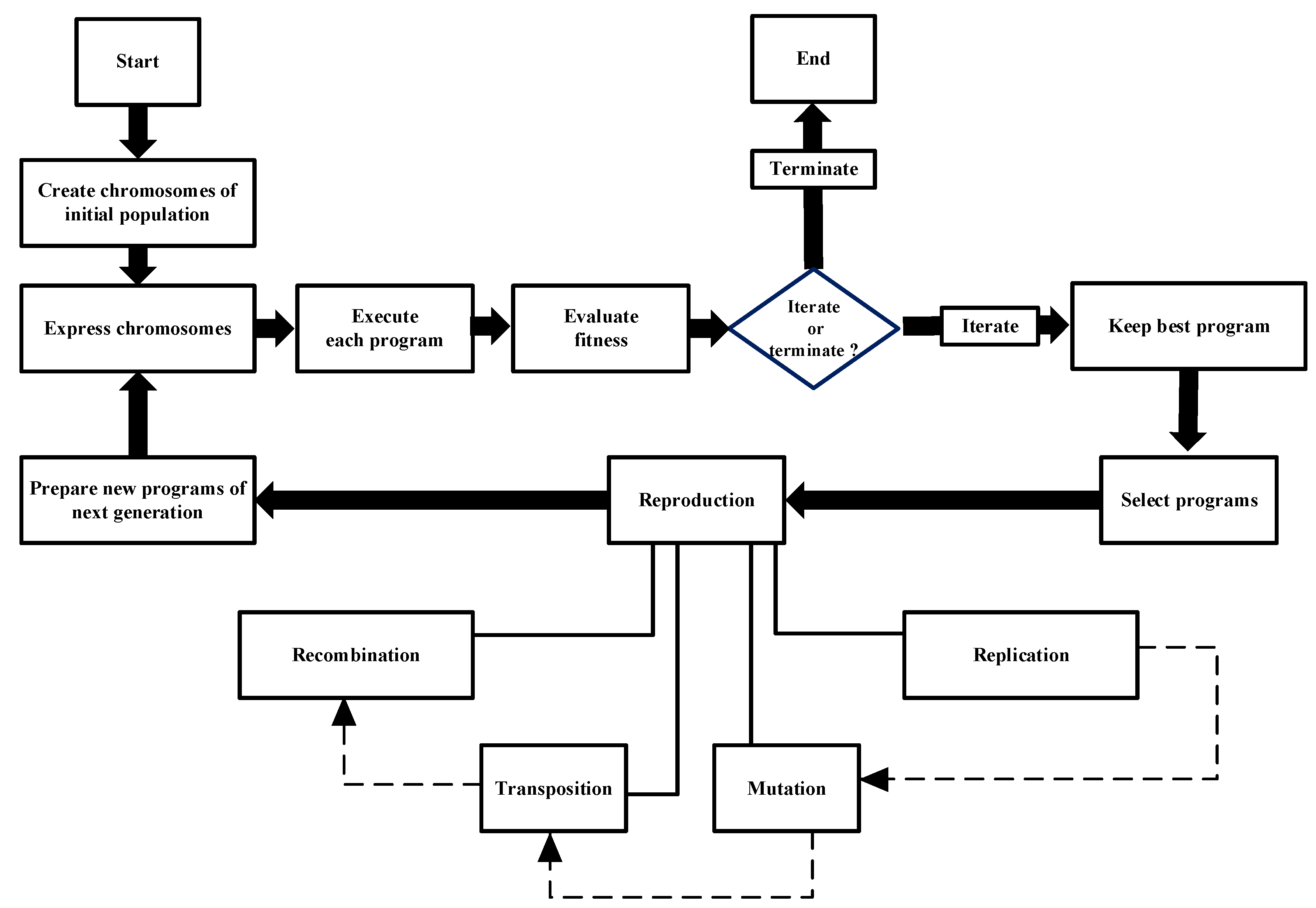

3.2.5. Gene Expression Programming (GEP)

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| ANFIS | Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System |

| BT | Boosting Tree |

| EMD | Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GEP | Gene Expression Programming |

| GMDH | Group Method of Data Handling |

| GP | Genetic Programming |

| GRNN | Generalised Regression Neural Networks |

| LGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| LTEF | Long-Term Electrical Energy Forecasting |

| LSSVM | Least Squares Support Vector Machines |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MARS | Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines |

| MERRA-2 | Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 |

| MLP | MultiLayer Perceptron |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| MLTF | Medium-Term Electrical Energy Forecasting |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| MSLR | Multiple Least Squares Regression |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SCG | Scaled Conjugate Gradient |

| STEF | Short-Term Electrical Energy Forecasting |

| VSTEF | Very Short-Term Electrical Energy Forecasting |

| WD | Wavelet Decomposition |

| XGB | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Allouhi, A.; El Fouih, Y.; Kousksou, T.A.J.; Zeraouli, Y.; Mourad, Y. Energy Consumption and Efficiency in Buildings: Current Status and Future Trends. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.C. Electric load forecasting by support vector model. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2009, 33, 2444–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecati, C.; Kolbusz, J.; Różycki, P.; Siano, P.; Wilamowski, B.M. A Novel RBF Training Algorithm for Short-Term Electric Load Forecasting and Comparative Studies. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2015, 62, 6519–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedinec, A.; Filiposka, S.; Dedinec, A.; Kocarev, L. Deep belief network based electricity load forecasting: An analysis of Macedonian case. Energy 2016, 115, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Fan, S. Probabilistic electric load forecasting: A tutorial review. International Journal of Forecasting 2016, 32, 914–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboli, H.R.; Fallahpour, A.; Selvaraj, J.; Abd Rahim, N. Long-term electrical energy consumption formulating and forecasting via optimized gene expression programming. Energy 2017, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.Q.; Khosravi, A. A review on artificial intelligence based load demand forecasting techniques for smart grid and buildings. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 1352–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.; Stewart, R.; Lu, J. Forecasting low voltage distribution network demand profiles using a pattern recognition based expert system. Energy 2014, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep Learning in Neural Networks: An Overview. Neural Networks 2014, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Hassan, M.Y.; Majid, M. Application of hybrid GMDH and Least Square Support Vector Machine in energy consumption forecasting. 2012, pp. 139–144. [CrossRef]

- Jinlian, L.; Yufen, Z.; Jiaxuan, L. Long and medium term power load forecasting based on a combination model of GMDH, PSO and LSSVM. 2017 29th Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC), 2017, pp. 964–969. [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Astiaso Garcia, D.; Keynia, F.; Bisegna, F.; Santoli, L. A novel composite neural network based method for wind and solar power forecasting in microgrids. Applied Energy 2019, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timur, O.; Zor, K.; Çelik, Ö.; Teke, A.; Ibrikci, T. Application of Statistical and Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Medium-Term Electrical Energy Forecasting: A Case Study for a Regional Hospital 2020. 8, 520–536. [CrossRef]

- Sarduy, J.R.G.; Di Santo, K.G.; Saidel, M.A. Linear and non-linear methods for prediction of peak load at University of São Paulo. Measurement 2016, 78, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goia, F.; Gustavsen, A. Energy performance assessment of a semi-integrated PV system in a zero emission building through periodic linear regression method. Energy Procedia 2017, 132, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukseltan, E.; Yucekaya, A.; Bilge, A.H. Forecasting electricity demand for Turkey: Modeling periodic variations and demand segregation. Applied Energy 2017, 193, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Mejías, R.; Pérez-Fargallo, A.; Rubio-Bellido, C.; Pulido-Arcas, J.A. Comparison of linear regression and artificial neural networks models to predict heating and cooling energy demand, energy consumption and CO2 emissions. Energy 2017, 118, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnasco, A.; Fresi, F.; Saviozzi, M.; Silvestro, F.; Vinci, A. Electrical consumption forecasting in hospital facilities: An application case. Energy and Buildings 2015, 103, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen Garcia, E.; Zorita, A.; Duque, O.; Morales, L.; Osornio-Rios, R.; Romero-Troncoso, R. Power Consumption Analysis of Electrical Installations at Healthcare Facility. Energies 2017, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damrongsak, D.; Wongsapai, W.; Thinate, N. Factor Impacts and Target Setting of Energy Consumption in Thailand’s Hospital Building. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2018, 70, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Gandomi, A. Short-term load forecasting of power systems by gene expression programming. Neural Computing and Applications 2012, 21, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhu, Y. The application of Empirical Mode Decomposition and Gene Expression Programming to short-term load forecasting. 2010, Vol. 8, pp. 4331–4334. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Huo, L.; Guo, L.; Hu, J. Short-term load forecasting based on improved gene expression programming. 2008 7th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, 2008, pp. 5647–5650. [CrossRef]

- Bakare, M.; Abdulkarim, A.; Nuhu, A.; Muhamad, M. A hybrid long-term industrial electrical load forecasting model using optimized ANFIS with gene expression programming. Energy Reports 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, S.; Nazeri Tahroudi, M.; Hamraz, B. Comparison of the performances of GEP, ANFIS, and SVM artifical intelligence models in rainfall simulaton. Időjárás 2021, 125, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, F.; xu, Y.; Iqbal, M.; Javed, M.F.; Jamhiri, B. Predictive modeling of swell-strength of expansive soils using artificial intelligence approaches: ANN, ANFIS and GEP. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 289C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, B.; Kim, C. A Study on the development of long-term hybrid electrical load forecasting model based on MLP and statistics using massive actual data considering field applications. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 221, 109415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Keynia, F. Mid-term Electricity Load Forecasting by a New Composite Method Based on Optimal Learning MLP Algorithm. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafati, A.; Joorabian, M.; Mashhour, E. An efficient hour-ahead electrical load forecasting method based on innovative features. Energy 2020, 201, 117511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaoudi, M.S.; Refaat, S.; Chihi, I.; Trabelsi, M.; Oueslati, F.; Abu-Rub, H. A novel stacked generalization ensemble-based hybrid LGBM-XGB-MLP model for Short-Term Load Forecasting. Energy 2020, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damrongsak, D.; Wongsapai, W.; Thinate, N. Factor Impacts and Target Setting of Energy Consumption in Thailand’s Hospital Building. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2018, 70, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordillo-Orquera, R.; Lopez-Ramos, L.M.; Muñoz-Romero, S.; Iglesias-Casarrubios, P.; Arcos-Avilés, D.; Marques, A.G.; Rojo-Álvarez, J.L. Analyzing and Forecasting Electrical Load Consumption in Healthcare Buildings. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Gui, M.; Baran, M.; Willis, H. Modeling and forecasting hourly electric load by multiple linear regression with interactions. 2010, pp. 1 – 8. [CrossRef]

- Amral, N.; Ozveren, C.; King, D. Short term load forecasting using Multiple Linear Regression. 2007, pp. 1192 – 1198. [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, M.G.; Malvoni, M.; Congedo, P. Comparison of strategies for multi-step ahead photovoltaic power forecasting models based on hybrid group method of data handling networks and least square support vector machine. Energy 2016, 107, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Xie, L.; Liu, D.; Huang, J. A hybrid model based on selective ensemble for energy consumption forecasting in China. Energy 2018, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag, O.; Yozgatligil, C. GMDH: An R package for short term forecasting via GMDH-type neural network algorithms. The R Journal 2016, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zor, K.; Çelik, Ö.; Timur, O.; Teke, A. Short-Term Building Electrical Energy Consumption Forecasting by Employing Gene Expression Programming and GMDH Networks. Energies 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishik, M.Y.; Göze, T.; Özcan, İ.; Güngör, V.Ç.; Aydın, Z. Short term electricity load forecasting: A case study of electric utility market in Turkey. 2015 3rd International Istanbul Smart Grid Congress and Fair (ICSG), 2015, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Ma, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, P. A Deep Neural Network Model for Short-Term Load Forecast Based on Long Short-Term Memory Network and Convolutional Neural Network. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilamowski, B.M. Neural network architectures and learning algorithms. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 2009, 3, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S. The Vanishing Gradient Problem During Learning Recurrent Neural Nets and Problem Solutions. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems 1998, 6, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzani, S.; Granderson, J.; Fernandes, S. Gradient boosting machine for modeling the energy consumption of commercial buildings. Energy and Buildings 2017, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, T.; Howard, J. How to Explain Gradient Boosting: Illustration of GBDT by Golf Example, 2019.

- Persson, C.; Bacher, P.; Shiga, T.; Madsen, H. Multi-site solar power forecasting using gradient boosted regression trees. Solar Energy 2017, 150, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. Gene Expression Programming: a New Adaptive Algorithm for Solving Problems, 2001, [arXiv:cs.AI/cs/0102027].

- He, Y.; Zheng, Y. Short-term power load probability density forecasting based on Yeo-Johnson transformation quantile regression and Gaussian kernel function. Energy 2018, 154, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Ö.; Teke, A.; Yıldırım, B. The optimized artificial neural network model with Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm for global solar radiation estimation in Eastern Mediterranean Region of Turkey. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zor, K.; Timur, O.; Çelik, Ö.; Yıldırım, B.; Teke, A. Interpretation of Error Calculation Methods in the Context of Energy Forecasting. 2017.

| Very-Short Term | Short-Term | Medium-Term | Long-Term | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Purchasing | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Electrical Power System Planning | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Demand Management | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Maintenance and Operation | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Finance | ✓ | ✓ |

| Category | Predictor Name | Description | Unit | Min | Median | Mean | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical | consP1 | Previous Hour Consumption | MWh | 28.8 | 63.14 | 62.52 | 127.70 |

| consP24 | Previous Day Consumption | MWh | 28.8 | 63.14 | 62.52 | 127.70 | |

| consP168 | Previous Week Consumption | MWh | 28.7 | 63.14 | 62.52 | 127.70 | |

| consP720 | Previous Month Consumption | MWh | 28.7 | 63.14 | 62.52 | 127.70 | |

| Meteorological | T2M | Temperature at 2 Meters | °C | 3.45 | 19.47 | 19.37 | 44.47 |

| RH2M | Relative Humidity at 2 Meters | % | 5.81 | 53.50 | 53.47 | 100.00 | |

| PREC | Precipitation | mm/hour | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0583 | 7.90 | |

| PRES | Surface Pressure | kPa | 96.8 | 98.45 | 98.47 | 100.36 | |

| WS10M | Wind Speed at 10 Meters | m/s | 0.02 | 3.0 | 3.299 | 15.77 | |

| WD10M | Wind Direction at 10 Meters | Degrees | 0.0 | 184.375 | 185.375 | 359.93 | |

| Calendar | MoY | Month of Year | - | 1.0 | 7.0 | 6.522 | 12.0 |

| DoM | Day of Month | - | 1.0 | 16.0 | 15.75 | 31.0 | |

| DoW | Day Of Week | - | 1.0 | 4.0 | 3.99 | 7.0 | |

| HoD | Hours of Day | - | 0.0 | 11.5 | 11.49 | 23.0 | |

| ToD | Time of Day | - | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.3187 | 1.0 |

| Technique | Applied Model | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| STATISTICAL | MLR |

|

|

| Technique | Applied Model | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | GMDH |

|

|

| Technique | Applied Model | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | MLPNN |

|

|

| Technique | Applied Model | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | GBDT |

|

|

| Technique | Applied Model | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | GEP |

|

|

| Training | Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | R2 (%) | MAPE (%) | R2 (%) | MAPE (%) | Computational Time (s) |

| GBDT | 99.432 | 0.768 | 98.591 | 0.827 | 6.99 |

| MLR | 99.221 | 0.840 | 98.934 | 0.844 | 0.73 |

| GMDH | 99.225 | 0.843 | 98.917 | 0.844 | 47.65 |

| GEP | 99.161 | 0.836 | 98.910 | 0.856 | 76.48 |

| MLPNN | 99.214 | 0.897 | 98.912 | 0.909 | 283.96 |

| y | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.373176 | 0.995068 | -0.010423 | 0.000928 | -0.000072 | -0.001758 | |||

| -0.098162 | 0.030519 | 1.001483 | 0.000412 | -0.00089 | ||||

| 0.427163 | -0.022356 | 0.99412 | 0.000252 | 0.000264 | -0.000015 | |||

| 0.438007 | -0.018055 | 0.990181 | 0.000897 | -0.001366 | -0.000004 | |||

| -0.055873 | -0.953728 | 1.955633 | 6.915873 | -3.449387 | -3.466498 | |||

| 0.002755 | 0.001672 | 1.001275 | 0.000032 | -0.00002 | -0.000055 | |||

| 0.418694 | -0.010462 | 0.989895 | 0.000929 | -0.001762 | -0.000005 | |||

| 0.339005 | -0.01959 | 0.99359 | 0.000198 | 0.000194 | 0.000026 | |||

| -0.022724 | 4.027849 | -3.027107 | 20.15361 | -10.10289 | -10.05072 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).