1. Introduction

Critical Infrastructures (CIs) are indispensable for daily life but remain vulnerable to crises such as natural disasters or targeted attacks, which can disrupt vital services like energy and transportation [

1,

2,

3]. Because these events often occur without warning, the lack of reliable, up-to-date infrastructure data hinders rapid crisis management, particularly in municipalities with lower levels of digitisation that lack comprehensive digital representations of their CIs.

Although open geographic data from crowdsource and community-driven projects like OpenStreetMap (OSM) can inform risk management [

4], their varying completeness and consistency pose significant challenges to effective decision-making. Consequently, emergency services, healthcare facilities, and utilities can face operational delays that jeopardise public safety and incur substantial economic losses during crises [

5,

6].

Bridging data gaps in OSM to reconstruct an approximate model of existing power grids becomes essential for a broad range of stakeholders—those who need to assess disaster impacts on grid topology or make infrastructure decisions when up-to-date grid models are unavailable. Grid-mapping approaches often rely on expert knowledge, proprietary data, or manual intervention [

7,

8,

9], limiting their scalability in dynamic emergency scenarios. In such situations, even an approximate grid representation can be indispensable for rapid decision-making.

Recent progress in Digital Twin (DT) technologies [

10,

11] and open-data integration offers promising pathways for CIs resilience. A DT is bidirectionally coupled by means of a twinning mechanism to ensure the virtual replica is in an up-to-date state. CIs resilience-related tools utilising the replica can implement smart functionalities, simulation and control action on the real object. This study aligns with that paradigm by contributing to crisis management and infrastructure resilience in the reacting phase. Building on our earlier work [

10], we propose an automated toolbox for reconstructing Medium Voltage (MV) power grid models based solely on OSM.

OSM has become a prominent open-data resource for geospatial information, providing extensive global coverage and a standardised format well-suited for distribution-grid research [

9,

12,

13,

14]. Its collaboratively maintained database includes geo-located information on roads and power-network elements, often derived from aerial imagery, on-site surveys, or other openly licensed data. Although completeness varies by region, two main advantages make OSM particularly valuable for grid reconstruction. First, it is actively maintained and continuously expanding, ensuring the longevity of tools that rely on its evolving dataset. Second, its worldwide coverage supports broader applicability, enabling methods to scale across diverse urban contexts. This study introduces an open-data-centric approach that leverages OSM’s existing power infrastructure and land-use data to estimate and augment missing grid elements. By dispensing with proprietary or expert-restricted sources, our method provides a scalable solution for reconstructing MV power grids across multiple urban environments.

The main contribution of this work is an automated, data-driven methodology for estimating energy demand and reconstructing MV power grids using only OSM data. Specifically, we (i) retrieve and preprocess publicly available geospatial information, (ii) estimate energy demand and identify gaps in secondary substations via a land-use-based approach, (iii) employ a constraint-programming solver to produce realistic MV networks, and (iv) generate layered visual outputs for rapid interpretation and “what-if” simulations. By offering a reproducible, open-data-centric method, this work provides a scalable approach for addressing incomplete grid data, supporting both crisis management and broader infrastructure analysis, and ultimately laying the groundwork for enhanced CIs resilience.

To our knowledge, no existing approach offers the level of automation in reconstructing MV grid models by solely utilising OSM data without expert input or geographically constrained datasets. Our method addresses the challenges of inconsistent data, incomplete infrastructure mapping, and reliance on proprietary sources. It automates tasks traditionally handled manually and introduces a scalable means of estimating and resolving supply-demand discrepancies in urban energy infrastructures.

We validate our approach through a case study of Darmstadt, a medium-sized German city. This evaluation demonstrates how open geospatial data can be processed to efficiently reconstruct representative MV grids, identify potential discrepancies, and address data gaps in the OSM transformer inventory, especially in commercial and industrial zones with lower mapping completeness (data coverage and availability). Performance metrics, visual outputs, and statistical assessments compare land use power demand estimation to the OSM power transformers data to identify potential data gaps.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews related work on grid reconstruction.

Section 3 presents preliminaries and the method overview, followed by data acquisition and preprocessing in

Section 4 and

Section 5, respectively.

Section 6 explains secondary substation estimation based on land use, while

Section 7 describes the generation of the MV grid topology.

Section 8 outlines our visualisation approach, and

Section 9 presents the evaluation case study, a discussion, implications and limitations. Finally,

Section 10 concludes and discusses future directions.

2. Related Work

The automated modelling of power grids has gained increasing attention in recent years, driven by the need for scalable and efficient solutions to address growing urban energy demands [

15]. Traditionally, grid reconstruction relied on static assumptions and proprietary datasets. In response, recent research has shifted toward open-data-driven and algorithmic approaches.

Several open-source tools and initiatives [

7,

9,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] extract power grid information from OSM, demonstrating the potential for automated modelling to streamline energy distribution network reconstruction and support adaptive urban planning [

21]. However, most early work has centred on High Voltage (HV) networks, while MV and Low Voltage (LV) grids remain challenging due to data scarcity, sensitivity, and proprietary restrictions. Moreover, incomplete mapping of underground cables and smaller-scale components often limits the applicability of these open-data-based methods [

22], underscoring the complexity and variability of modern urban energy systems.

Kisse et al. [

23] introduced a GIS-based framework that combined OSM data with pandapower to model power and gas distribution grids integrated with heat pump systems. Although their synthetic grid models provided valuable insights such as investment costs and CO

2 reductions, the approach still required manual editing of transformer locations where source data was insufficient, limiting its scalability and full automation. Similarly, Dierich et al. [

8] and Fekete [

4] integrated qualitative stakeholder insights with Geographic Information System (GIS) analyses to assess critical infrastructure interdependencies and cascading effects during crises. While these mixed-methods approaches improved situational awareness, they depended on localised data, expert input, and proprietary GIS tools, which can restrict generalisability.

Focusing specifically on MV grids, Gebhard et al. [

9] leveraged OSM substation and street network data, Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP)-based optimisation, Voronoi diagrams, and Delaunay triangulation (a method that naturally connects points that are spatially close) to generate cost-optimal MV topologies. Their method incorporated optional manual adjustments, for instance, by including proprietary or uncertain load data as a list of custom locations. Although land use data was discussed, it was not integrated into the automation process. Their case study demonstrated that even incomplete OSM data for secondary substations can yield realistic grid topologies. However, the quality of the result depends on the quality of the regional OSM data.

Tomaselli et al. [

7] further advanced the field by generating ensembles of LV grid topologies to capture uncertainty through probabilistic methods. Yet their approach relied on expert-provided substation inputs [

23]. Likewise, [

20] assumed secondary substations as given. Other work by Tomaselli et al. [

24] used external references to extract or synthesise transformer coordinates, reducing but not eliminating manual intervention and reliance on external dataset quality.

Meanwhile, Baecker et al. [

12] presented a methodology that combines OSM-derived building data with statistical information from sources like CORINE Land Cover [

25] and TABULA [

26], relying on German census-based assumptions [

27] for household counts and external studies for peak loads [

14,

28]. Although innovative and capable of producing highly granular results, this approach still hinges on region-specific data for residential and non-residential peak loads and expert-derived building typologies, raising questions about its generalisability to other regions.

Beyond these approaches, land use data has proven valuable for infrastructure modelling [

29,

30,

31,

32], providing essential spatial insights by classifying geographic areas according to their social functions. However, most MV grid reconstruction efforts use land-use data to define load areas or generate virtual MV-LV stations, often without integrating OSM-derived power infrastructure data [

33,

34,

35]. For instance, the DINGO tool [

33] employs OSM-based land-use classifications to delineate load zones, followed by clustering or Voronoi-based assignment of supply points to HV-MV stations. While some methods use the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) [

35] or the CVRP [

33,

34] to optimise grid layouts, these approaches generally model direct point-to-point connections and have focused on rural settings.

In summary, despite the significant progress in automated grid reconstruction, three main challenges persist:

Focus on HV networks: MV and LV reconstructions remain underexplored and often less automated.

Reliance on manual inputs, proprietary data, expert knowledge, or geographically constrained datasets: Many methods still require expert intervention, closed-source datasets, or regional assumptions that limit scalability and reproducibility.

Underutilisation of land use data for urban demand and substation estimation: While OSM data is increasingly used in research, its land use layer is rarely leveraged to estimate missing grid elements directly in dense urban environments.

Our work addresses these gaps by presenting a synthetic grid reconstruction methodology that integrates both OSM land use data and existing power infrastructure, automating spatial energy demand estimation and MV grid topology generation. Our approach aims to provide a scalable solution for urban environments, reducing reliance on proprietary sources and manual refinements, with potential use in crisis management and rapid decision-making scenarios.

3. Method

To contextualise the modelling approach used in subsequent sections,

Section 3.1 introduces preliminaries of the problem, then

Section 3.2 presents our method overview.

3.1. Preliminaries

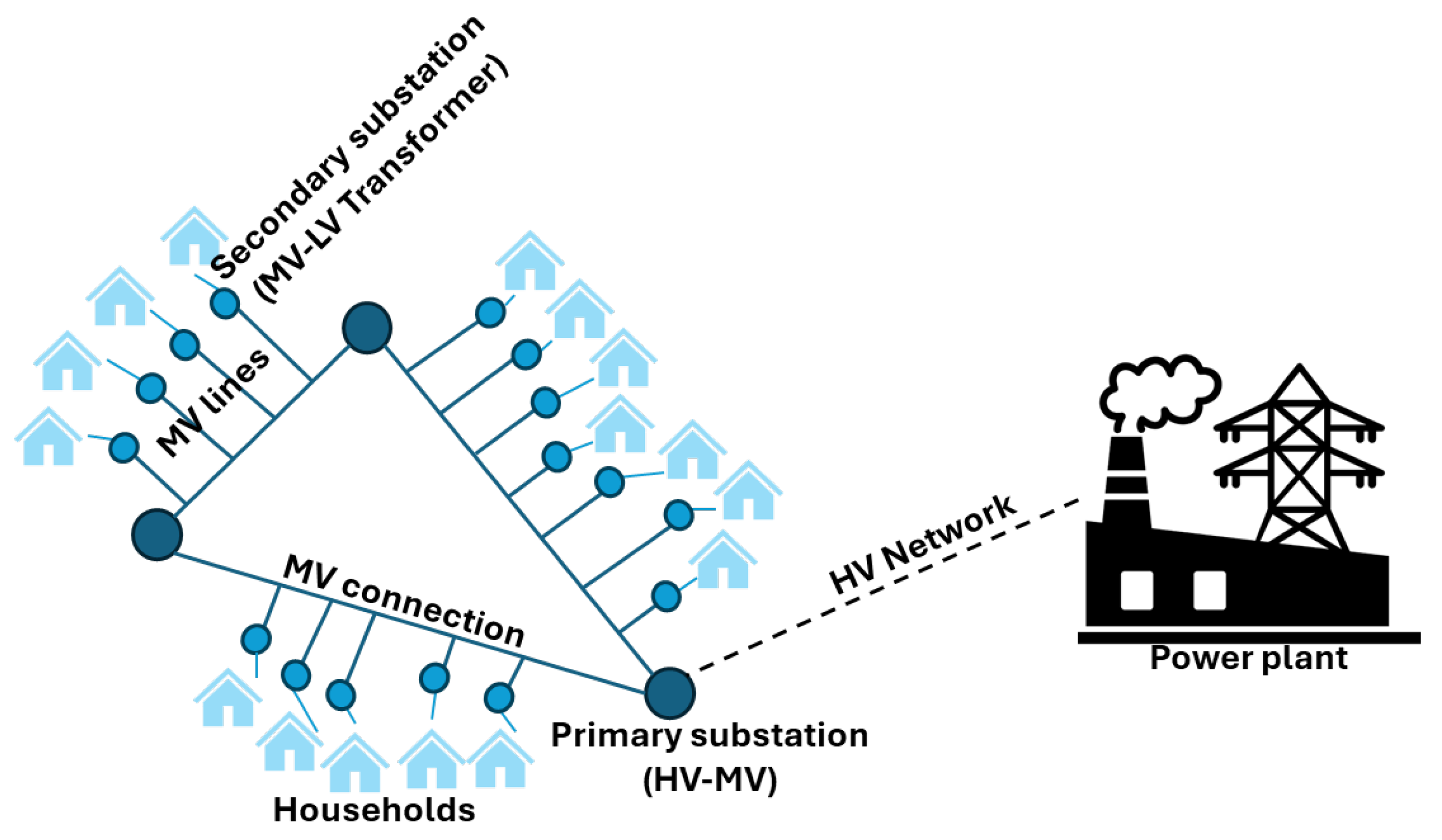

Figure 1 schematically shows an electrical distribution grid, including its embedding into the larger power system context. For this paper, the MV grid, including its nodes and lines, as well as the primary and secondary substations, are of relevance.

Electrical grids are composed of buses, substations, and lines at different voltage levels. Transformers in substations allow stepping the voltage up or down, easing the transmission of electrical energy. While the transmission of electrical power over large distances usually takes place at the extra-high voltage level (above 200 kV), distribution grids can be separated into HV, MV, and LV level. For example in Germany, MV is commonly defined as below 50 kV, while LV is considered as below 1 kV. Residential and commercial customers are connected at the LV layer, while industrial ones are often connected to the MV grid. Traditionally, power generation was connected only to the transmission grid, but due to the energy transition, distribution grids are increasingly transformed with local generation like wind and solar power.

At urban scales, two types of substations are relevant for this work. Primary substations contain transformers for converting power between the HV and MV level. Secondary substations (or transformers) convert MV to LV. Due to their network character, distribution grids can be modelled as undirected, weighted, geometric graphs . Each node corresponds to a bus or substation, connected via power lines (mostly cables in urban areas), represented as edges . The edge weights can reflect the cost of a line. We model the network as undirected because power lines allow a bidirectional flow of power.

3.2. Method Overview

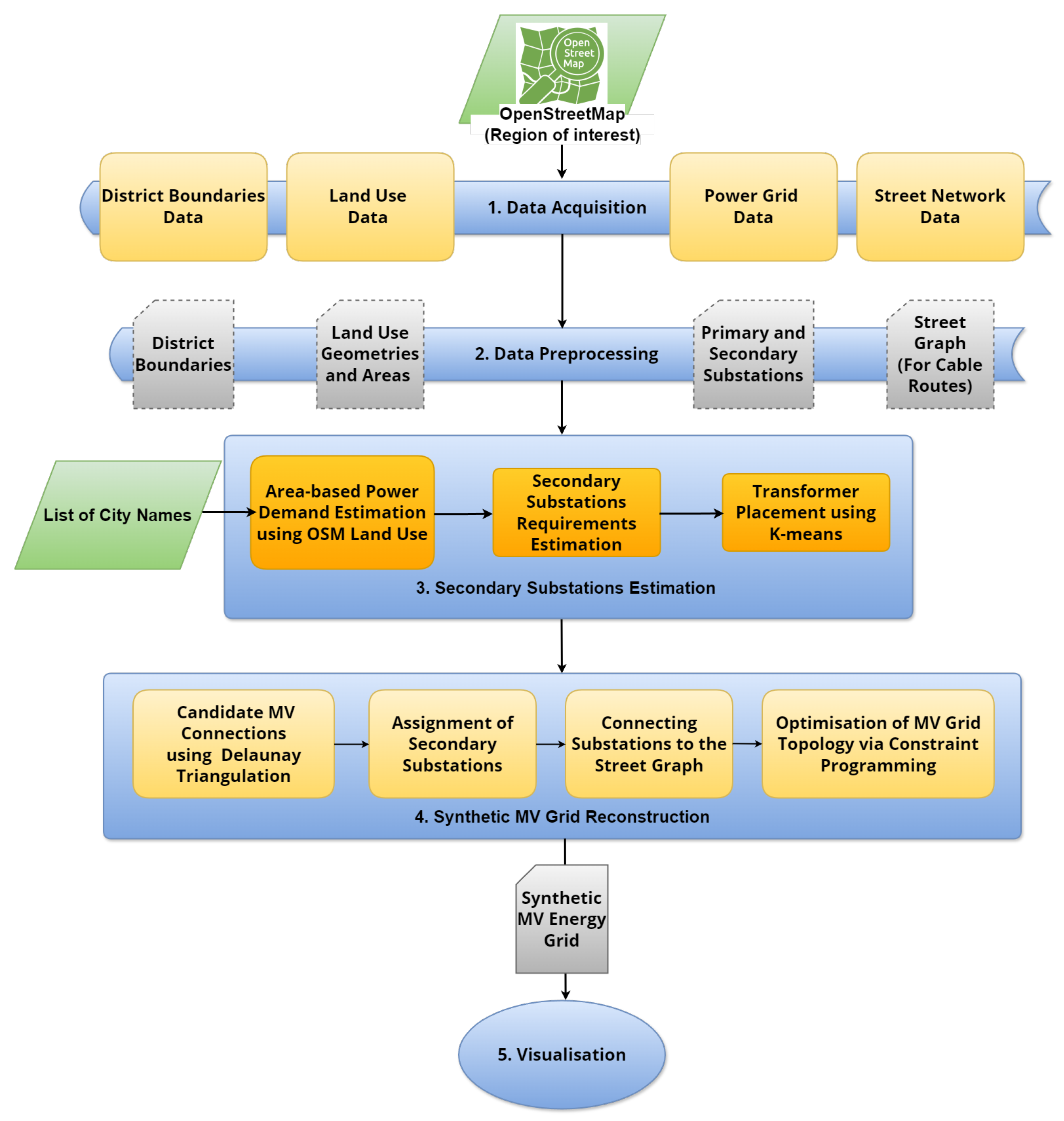

The proposed approach, illustrated in

Figure 2, provides an automated method for reconstructing a synthetic MV power grid by leveraging land-use and power infrastructure data from OSM. The final output is a graph-based representation of the MV network, where:

Nodes represent primary and secondary substations, each with geographic locations and relevant attributes (e.g., voltage, type)

Edges represent MV lines aligned with actual street paths for spatial realism.

By framing the grid in this manner, the approach allows stakeholders (e.g., crisis response teams) to identify approximate cable locations and assess which specific roads might carry MV lines. For instance, if a street is damaged or a primary substation is compromised, one can rapidly gauge how the power supply might be disrupted. The methodology minimises total cable length subject to capacity constraints (via an optimisation problem detailed in

Section 7.4) to yield a plausible, cost-effective MV layout.

The approach proceeds through four key steps, each generating outputs essential for subsequent analyses:

- 1.

-

Data acquisition: Administrative district boundaries, land-use features, power grid data, and street network information are retrieved from OSM.

Result: A collection of raw geospatial data layers—district polygons, land-use polygons, existing substations, and street network.

- 2.

-

Data preprocessing: The geospatial data are cleaned, filtered, and standardised into a consistent coordinate system.

Result: A validated and harmonised dataset, complete with corrected geometries, classified substations, and uniform spatial referencing.

- 3.

-

Secondary substations estimation: Land-use areas are aggregated, and a specialised workflow is applied to detect coverage gaps in the existing MV grid and estimate where additional transformers may be required.

Result: An updated substation inventory that bridges gaps in the MV grid by incorporating newly placed secondary substations.

- 4.

-

Synthetic MV grid reconstruction: Network cost is minimised subject to capacity constraints, ensuring that cables align with realistic street paths for a plausible MV network topology.

Result: A fully constructed synthetic MV network—modelled as a weighted graph where edges follow the street geometry—enabling subsequent analysis or scenario-based evaluations (e.g., identifying the impact of street closures or a primary substation compromise on the power supply).

These steps support demand estimation, coverage validation, and optimisation of grid layout. Algorithm 1 provides a high-level overview of the reconstruction process, while the subsequent sections elaborate on each step in detail. Therefore, the algorithm’s output is a spatially explicit MV grid with edges reflecting actual street corridors, which can serve as a practical resource for crisis managers and municipal planners.

|

Algorithm 1 Steps for MV Grid Reconstruction using Land Use Estimation |

- 1:

Input: Region of interest (area name) - 2:

Output: Optimised placement of secondary stations and synthetic power grid topology - 3:

Step 1: Data Acquisition (Fetch Data from OSM) - 4:

Fetch district boundaries data, land use data, power grid data, street network data - 5:

Step 2: Data preprocessing - 6:

Preprocess district geometries, land use polygons, and classify substations - 7:

Step 3: Secondary Substations Estimation (Based on Land Use Data) - 8:

3.1 Assign transformers capacity - 9:

3.2 Calculate Land Use Areas - 10:

3.3 Derive state demand per square meter estimations using land use data - 11:

3.4 Calculate power demand per area using land use data - 12:

3.5 Estimate substations according to land use and supply-demand discrepancy - 13:

3.6 Placement of synthetic transformers - 14:

Step 4: Synthetic MV Grid Reconstruction - 15:

4.1 Generates candidate MV connections between primary substations - 16:

4.2 Assignment of secondary substations to candidate MV connections - 17:

4.3 Connecting substations to the street graph - 18:

4.4 Generation of street network edges and calculating the actual street distances - 19:

4.5 Optimise MV grid via Constraint Programming (CP) formulation - 20:

Step 5: Visualisation - 21:

Generate layered visuals to facilitate further analysis. |

4. Data Acquisition from OSM

Our approach relies on OSM as the only source for geospatial data to obtain four main data layers: district boundaries, land use data, power grid infrastructure, and street networks. The OSMnx library automates data retrieval. This section corresponds to Step 1 in Algorithm 1.

District Boundaries Data: Districts refer to municipal administrative subdivisions that serve governance and planning purposes. In this study, district boundaries are extracted from OSM to define the study area, enabling spatially disaggregated analyses of infrastructure, land use and demand. In OSM, these subdivisions are tagged with

boundary=administrative and a corresponding

admin_level1. In this work, we focus on and retrieve the relevant polygons for

admin_level=10, as it typically represents the smallest formally recognised administrative units.

Land Use Data: Within the extracted district boundaries, we retrieve land use features: landuse=residential, landuse=commercial, and landuse=industrial. These categories form the basis for estimating urban energy demand as we associate each land use type with different demand patterns.

Power Grid Data: Power grid infrastructure, including substations and transformers, is queried using OSM tags power=substation and power=transformer. Due to their good coverage in OSM and their manageable number for one city, primary substations can be assumed as given. Relevant attributes such as name, voltage, and frequency are included. Geometries are processed with the Shapely library, extracting coordinates for point features and centroids for polygonal features.

Street Network Data: Due to the limited availability of MV power distribution lines in OSM, they are assumed to follow street layouts, as supported by prior studies [

7,

9,

22]. Therefore, the street network from OSM is used as the base graph for modelling possible cable routes, assuming a radial grid topology. The street network data is retrieved via OSMnx, based on predefined modes (e.g.,

walk for pedestrian paths and

drive for vehicle-accessible roads). This network is used later to compute realistic distances between substations and to model cable routes.

5. Data Preprocessing

This section corresponds to Step 2 in Algorithm 1. It refines and standardises the raw OSM-extracted data layers—district boundaries, land use polygons, power grid elements, and street networks—so they can reliably support the subsequent grid reconstruction. In particular, it tackles the data inconsistencies and missing attributes often observed in OSM, which is a community-driven platform. Such crowd-sourced data can contain partially overlapping polygons, inconsistent geometric definitions, and attribute discrepancies (e.g., missing voltages or incorrect substation tags).

District Boundaries: District polygons, extracted initially from OSM, may overlap or extend beyond the main city area due to heterogeneous mapping inputs or different admin_level definitions. We remove overlaps, discard polygons not fully contained within the city boundary, and resolve invalid geometries. Next, each district is transferred into a uniform coordinate system suited for distance and area measurements. This ensures that the polygons do not double-count or omit any city areas and are comparable and measurable on the same spatial scale.

Land Use Geometries and Areas: Although we initially extracted residential, commercial and industrial land use features in the acquisition step, these polygons are stored in OSM’s global latitude-longitude format. For more precise local-area calculations, we transform them into a suitable coordinate reference system and clip them so that only the parts within each district boundary remain. As a result, each district ends up with its own clearly defined land use categories data, which can then be analysed independently for energy demand or other purposes.

Primary and Secondary Substations: Only a few features have assigned voltage and frequency values in OSM for the power grid. Therefore, retrieved power grid features must be preprocessed.

Features with a frequency value that differs from the main grid frequency ( in Europe) are excluded, for example, to avoid elements from the railway power system.

Substations without names are assigned placeholder identifiers based on OSM IDs.

Due to inconsistencies in OSM tagging (e.g., interchanging power=substation and power=transformer), a voltage-based strategy ensures consistent classification.

Features with voltage above are categorised as primary substations, while those below or with missing voltage values are classified as secondary substations. A default voltage of is assigned to elements with undefined voltage.

Each substation is then spatially attributed to its corresponding district and land use category, enabling a quantitative assessment, i.e., determination of substation counts per land use within each district.

This two-step acquisition-preprocessing arrangement helps ensure that OSM-extracted features are both comprehensive (broadly acquired) and accurate (cleaned, consistently measured, and clipped) before we move to the next step in the grid reconstruction process.

6. Secondary Substations Estimation Based on Land Use

This section corresponds to Step 3 in Algorithm 1 and details a data-driven methodology based solely on OSM. By relying solely on energy and land use data from OSM, the proposed approach avoids dependence on proprietary or region-specific datasets, ensuring replicability of the method and broad applicability across different regions, even when traditional grid data models are unavailable.

6.1. Transformer Capacities

As noted by [

12], LV transformer capacities are scarcely available in OSM. Due to the unreliability of OSM metadata, their study employed building density as a proxy to select standard transformer sizes conforming to standard utility practices. Since our approach deliberately does not incorporate buildings to avoid reliance on external, geographically constrained datasets for building-area-dependent peak load estimations and instead relies solely on OSM land use data, we adapt their methodology to determine transformer capacities. Specifically, we select 160 kVA for residential areas (low to medium demand), 250 kVA for commercial zones (medium to high demand), and 400 kVA for industrial areas (high demand).

6.2. Land Use Area Calculation

Each land use category is aggregated within each district to obtain cohesive polygons (e.g., all residential polygons unified). We then compute these unified polygons’ total area (in square meters). This step effectively yields each district’s final land use areas, forming the spatial foundation for subsequent demand estimation.

6.3. Demand per Square-Meter Using OSM Land Use

This subsection describes a data-driven, automated method to derive demand per square meter for various land use types using OSM data.

We gather transformer data and land use areas from multiple cities to estimate energy demand for each land use category. This ensures that derived demand values reflect state-level conditions. In this study, 25 counties and independent cities in Hesse, Germany

2, encompassing 299 districts, are employed for this purpose. The input data can be readily extended to include additional cities, enabling a broader application of the proposed methodology. Moreover, the approach exhibits high scalability, as incorporating further cities requires minimal effort—simply adding their names to the input list. Our process follows these steps:

- 1.

Gather Data from Other Cities: We collect district-level OSM data (transformers, land use areas) for a set of cities.

- 2.

Compute Capacity per Land Use: In each district, we multiply the number of OSM transformers (attributed to that land use) by their standard capacities (see

Section 6.1), yielding a total transformer capacity.

- 3.

Obtain Demand per Square meter: We divide the total capacity by the district’s land use area (in square meters), obtaining a “demand density” (kVA/m2) for that land use type.

- 4.

Average Across Districts and Cities: Each city’s data is aggregated to produce a city-level average for each land use type. We then compute the state-level average by merging these city-level values, effectively deriving a baseline demand per square meter for each land use category.

This data-driven approach bypasses reliance on geographically constrained or proprietary datasets, instead leveraging freely available OSM. It is parallelised for efficiency, taking under two minutes (93.34 seconds in our setup) to process hundreds of districts.

6.4. Power Demand per Area and Number of Secondary Substations Estimation

We obtain the total load for each land use by multiplying the baseline demand per square meter (

Section 6.3) by the land use area. Next, we divide this load by the transformer’s effective capacity (adjusted for future growth and conservative loading) and round up to the nearest whole number, revealing the required count of secondary substations. Comparing this estimate with the actual OSM-based substation inventory highlights any deficit, i.e., the missing transformers needed to meet the estimated demand.

Because OSM data can be incomplete, our method may estimate fewer transformers than OSM indicates (as shown in the discussion in

Section 9 for residential areas with multi-story buildings). In such cases, we do not remove existing substations; rather, we focus on bridging deficits. To mitigate possible underestimation, we apply a 10% growth factor (aligned with forecasts projecting load increases [

36,

37,

38]) and an 80% loading threshold to account for thermal stress [

39]. These measures ensure we do not drastically under-represent real-world demand conditions and possibly reflect common planning assumptions that may have been considered in the grid’s original design.

6.5. Transformers Placement

This subsection outlines how missing transformers are added to areas where our land use-based estimation indicates deficits. We employ a grid-based approach to represent demand as discrete "load zones" (

Section 6.5.1), then apply K-means clustering to identify suitable transformer locations.

6.5.1. Load Zone Generation

A spatially explicit representation of energy demand is required to guide the placement of new transformers. A "load zone" is a small, discrete portion of a land use polygon, essentially a point representing some fraction of the total demand in that area. To create these zones, we overlay a regular grid on each district’s land use polygon wherever the estimated number of needed transformers exceeds what OSM currently shows. Each grid cell within the polygon is assigned a portion of the total demand, producing a set of load zones with associated load values. By distributing demand uniformly among these generated grid points, we avoid lumping all consumption into a single location and using external, geographically constrained peak load estimations or proprietary datasets. Although this approach does not capture accurate variation, it provides a transparent and scalable way to represent spatial demand patterns using only OSM. The result is a set of load zones with associated load values.

6.5.2. K-Means Clustering for Synthetic Transformer Placement

We combine these load zones with the coordinates of existing transformers in the same district and land use. For each district and land use category with missing transformers, we create one cluster per missing transformer using K-Means clustering. Each cluster centre (the centroid of a group of zones and existing transformer points) becomes a new synthetic transformer location. This ensures new transformers are placed in areas with loads, are respectful of existing transformer positions, and are likely to reduce the distance between load pockets and transformer sites (helping lower technical losses). An optional post-processing step can be applied to "snap" each new transformer to the nearest valid street node to ensure realistic siting and viable locations.

Although we do not visualise these intermediate steps here,

Section 9 of the evaluation presents a map illustrating how newly placed transformers align with the identified load zones and existing infrastructure. Transformers placement is implemented utilising Shapely and scikit-learn libraries for spatial operations and K-Means clustering, respectively. The outcome of this step is a list of new transformer locations to cover previously unmet demand, which is then added to the secondary substation inventory for the synthetic MV grid reconstruction.

7. Synthetic MV Grid Reconstruction

This section outlines the method for generating a synthetic MV grid and corresponds to

Step 4 in Algorithm 1. The process involves generating candidate MV connections and the geometric assignment of secondary substations to candidate MV connections between primary substations (HV-MV) in

Section 7.1, connecting substations to the street graph in

Section 7.2, generating street distances and street network edges between substations in

Section 7.3 and finally, the optimisation of MV grid topology in

Section 7.4.

7.1. Candidate MV Connections and Assignment of Secondary Substations

We assume that each MV line is treated as a direct link between two distinct primary substations. This configuration permits each point to be served by two separate sides and from different primary substations, and all secondary substations are connected to the grid by exactly one line, not consisting of junctions. This keeps the network model focused on primary substations and their attached secondary substations.

Generating Candidate MV Connections: To identify potential MV routes, we adopt the proximity-based approach of [

9]. First, we gather the geographic coordinates of all primary substations. Next, we apply Delaunay triangulation, which connects points so no substation lies inside the circumcircle of any triangle, resulting in line segments between spatially close substations. We collect each segment to form a set of candidate MV connections.

Assigning Secondary Substations: Each secondary substation is assigned to the nearest candidate line based on Euclidean distance. This ensures every secondary node attaches to exactly one MV connection, providing the basis for subsequent integration, where realistic street network edges, distances and operational constraints will be incorporated to refine the synthetic grid topology.

7.2. Connecting Substations to the Street Graph

The electrical grid can be modelled as a graph, with nodes representing supply points (primary and secondary substations) and edges corresponding to cable lines following the street network. This process connects each substation to its nearest node within the street graph, aligning the grid with actual urban infrastructure.

7.3. Generating Street Distances and Street Network Edges Between Substations

With candidate connections established, we next integrate these with real street network data to ensure the grid’s alignment with urban infrastructure. To model realistic MV grid topologies, we compute the shortest path distances between the connected substations (

Section 7.2) based on the street network rather than geodesic distances using the NetworkX library. This generates the required distance matrix for optimisation while ensuring cost-effective grid reconstruction.

7.4. Optimisation of MV Grid Topology via Constraint Programming

Reconstructing an efficient MV grid topology requires minimising total cable length while ensuring that transformer capacities and physical cable limits are not exceeded. We address this routing challenge by formulating it as a constraint-programming problem [

40,

41] that explicitly encodes route continuity, capacity, and load distribution constraints.

7.4.1. Problem Formulation Using Constraint Programming

We model the grid as a sequence of nodes where primary substations serve as terminal nodes (node 0 for the start and node

for the end), and secondary substations (each with a capacity requirement

in kVA) occupy intermediate positions. The cost of connecting any two nodes

i and

j is defined by the street-network distance

(computed in

Section 7.2), and the total load along the route must not exceed a cable capacity

B (e.g., 10,000 kVA). Formally, we define:

Variables: Binary decision variables for all , where if the route travels directly from node i to node j; and auxiliary variables (for ) that track the accumulated load at node i.

Constraints: (i)

Route continuity: Each node (except the last) must have exactly one outgoing edge, and each node (except the first) exactly one incoming edge:

(ii) Capacity and subtour elimination: For all with , if the route travels from node i to node j (i.e., ), then the cumulative load at node j must be at least the cumulative load at node i plus the demand at node j (i.e., ), without exceeding the cable capacity:

Finally, the (iii)

overall capacity constraint limits the total load of secondary substations in the route:

The objective function: We aim to minimise the total cable length:

where

are the street-network distances between nodes

i and

j. These definitions yield a

constraint-programming model that enforces route continuity, capacity restrictions, and load distribution while minimising total cable length.

7.4.2. Solver Implementation

We assemble a distance matrix from precomputed street-network paths and a demand vector for each secondary substation. The solver then uses the variables and to find a sequence of nodes (primary-to-primary) that satisfies all constraints while minimising total cable length. The final solution includes the ordered route, total distance, and auxiliary outputs (e.g., the street segments).

8. Visualisation

An interactive map presents the grid model as distinct, toggleable layers for clarity and analysis using Folium. Administrative boundaries are outlined in black dashed lines with an orange fill, while land use categories are colour-coded for differentiation. Primary and secondary substations are marked with ID, voltage, and classification, with additional secondary substations appearing as black markers. Each substation is linked to the nearest street node, and demand clusters are visualised as filled polygons. MV grid routes are displayed using actual street paths, allowing interactive exploration of network expansion scenarios. The colour-coded, toggleable layers ensure clear differentiation and can support decision-makers analysing the grid.

9. Evaluation and Discussion

9.1. Case Study for a German City

We apply our methodology to Darmstadt, a medium-sized city with a population of over 168,457

3.

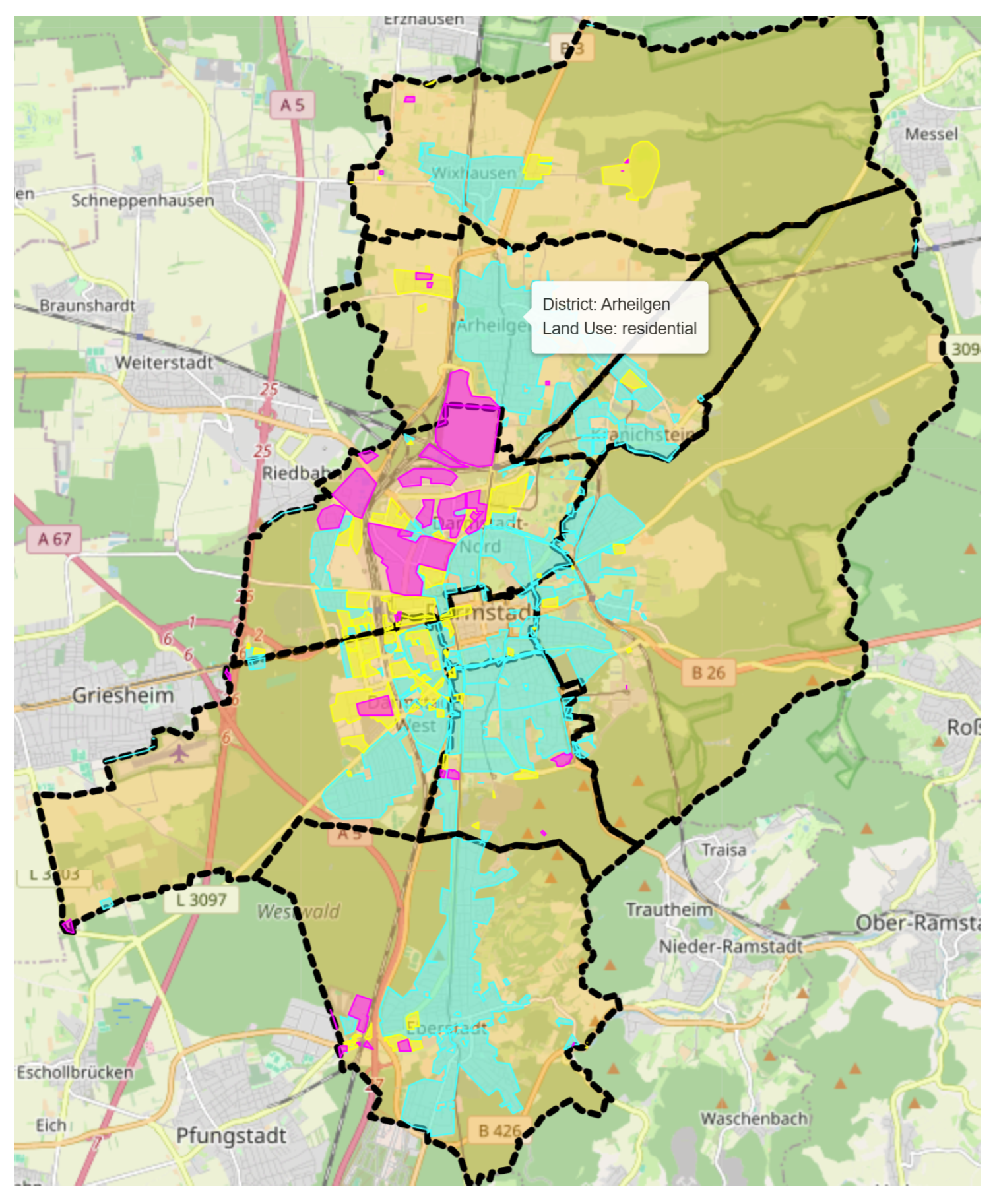

Figure 3 shows the extracted districts (9 total) and the mapped land use categories: residential (cyan), commercial (yellow), and industrial (magenta).

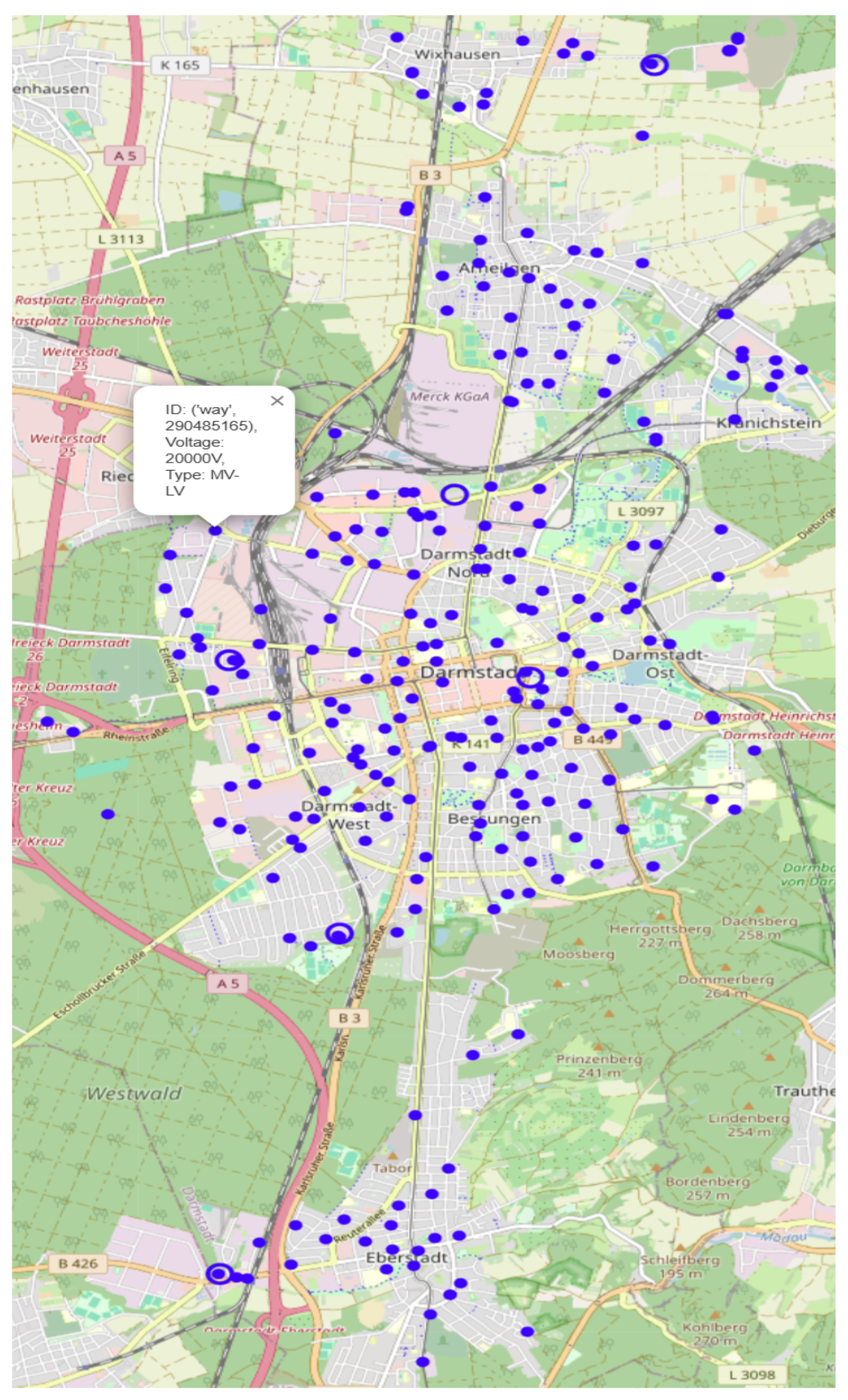

Figure 4 depicts six primary and 258 secondary substations from OSM (distinct markers).

Primary substations are depicted as larger blue-outlined circles, reflecting their higher voltage levels and role in the power grid. Secondary substations are shown as smaller filled blue circles, highlighting their lower voltage levels and smaller spatial footprints. Both marker types include labels displaying the substation ID, voltage level, and classification, enabling clear differentiation between HV-MV and MV-LV substations. We then generate the complete street graph and compute the shortest paths, caching the distance results for faster reuse.

Figure 5 illustrates the K-Means-based insertion of missing transformers in Darmstadt-Nord; existing transformers appear in blue, and newly placed ones in black. Finally, our constraint-programming solver generated the synthetic MV network (

Figure 6) with a total cable length of 163,836 m.

Although our primary goal is to validate the model’s reliability and to demonstrate the behaviour for city-level scenario analyses rather than optimise speed, we note that the method runs efficiently on a system equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700H @ 2.30GHz CPU and 32.0 GB RAM. For instance, processing district boundaries and land use features required a few seconds, while estimating loads took roughly 3 s. Fetching and processing substations took 0.12 seconds. The initial computation of street-network distances, including footpaths (664 s), is a one-time cost—after caching, subsequent runs complete in a fraction of this time (14.18 seconds). Substation connections to the street graph are established in 8.35 seconds. Applying the transformer placement algorithm took about 37 s. and the solvers had a max search time limit of 300 seconds per solution.

9.2. OSM Data Quality Assessment

Table 1 summarises the results of a comparison for Darmstadt between the estimated required number of secondary substations according to land use and the actual number retrieved from OSM data to estimate the missing number needed to cover the estimated demand. We then summarise these discrepancies across residential, commercial, and industrial land uses in

Table 2, computing mean difference, mean absolute deviation (MAD), root mean square error (RMSE), and coverage.

Overall, residential areas show slight overrepresentation in OSM (107% coverage), possibly reflecting higher mapping activity, or our approach does not capture multi-story buildings. Commercial areas are underrepresented by about 19%, while industrial zones (50% coverage) reveal the most significant gaps in OSM’s inventory. These discrepancies underscore the need for robust estimation methods (like ours) that can supplement incomplete OSM data, especially when assessing power infrastructure in crisis scenarios.

9.3. Implications and Limitations

In practice, overrepresentation of residential OSM transformers may result from community-driven mapping. At the same time, underrepresentation in commercial and industrial districts may stem from partially mapped private substations subject to industry-internal handling or restricted-access facilities. Although our land-use-based approach mitigates these gaps, it also relies on simplifying assumptions—such as uniform load distribution across each land use area.

The assumption of uniformly distributed loads preserves model generality and circumvents reliance on proprietary or region-specific consumption data; however, it may not accurately capture local variations within a single land use. Similarly, our methodology depends solely on OSM land-use data, foregoing occupant-level coincidence factors, detailed building footprints, and explicit kW-to-kVA conversions. This strategy enhances scalability and ensures applicability in regions lacking high-resolution datasets, yet it can underestimate demand when OSM data is incomplete. To counter this, we incorporate conservative margins; a growth factor and a loading threshold.

Another aspect is since our method relies solely on OSM data (both existing energy infrastructure and land use), it can leverage comparable cities—within the same country or even abroad—to derive global-state demand estimates. This is particularly advantageous where OSM data are absent for secondary energy infrastructure (e.g., transformer counts). However, it also underscores the need for research on data-absent contexts that avoid reliance on proprietary or highly localised inputs.

Where apparent excesses arise (e.g., a district with more OSM transformers than estimated), local factors such as multi-story buildings or incomplete neighbour data may be at play. Consequently, we focus on bridging deficits rather than redistributing surplus units. Future investigations could explore inter-district supply dependencies or integrate occupant-level/building-height data where freely available.

Our open-data-driven approach offers robust, scalable solutions but may undermine local precision. Higher-accuracy methods can incorporate occupant profiles and floor areas to refine load estimations, though they typically rely on geographically constrained or proprietary data. This trade-off underscores how purely OSM-based models minimise external dependencies and facilitate large-scale implementations, albeit with certain simplifying assumptions. For even greater fidelity, future work might refine these margins or incorporate new open datasets (e.g., nighttime satellite imagery, population density) to capture demand patterns more accurately.

10. Conclusions

This study presents an automated, open-data-based approach for reconstructing approximate synthetic MV power grids. Our primary contribution is a data-driven, land-use-based methodology that estimates energy demand and secondary substation placement without reliance on expert knowledge or proprietary datasets. By exclusively leveraging OSM energy infrastructure and land use data, our method overcomes several limitations of manual grid-mapping approaches and offers insights for diverse stakeholders.

The integration of an optimisation scheme ensures that the reconstructed grid topologies are both physically plausible and cost-effective by minimising total cable length under capacity constraints. Clear visual outputs further support rapid interpretation and decision-making. Our case study in Darmstadt demonstrates the practical applicability of our approach, highlighting how open data can successfully fill critical information gaps in transformer inventories, particularly in commercial and industrial areas.

While our approach relies on simplifying assumptions, such as a uniform load distribution, these choices were made to ensure scalability and broad applicability. To counteract potential underestimations due to incomplete OSM data, we incorporate conservative margins, which may reflect common planning practices. Future research should refine assumptions, integrate additional open data sources (e.g., nighttime satellite imagery, population density), and explore inter-district supply dependencies to enhance local precision.

In summary, our methodology offers a reproducible and scalable approach for MV grid reconstruction, contributing to the broader vision of digitally resilient cities by informing future energy system research and supporting practical crisis management efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.B. and E.B.; methodology, M.B. and E.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B. and E.B.; resources, M.B.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and E.B.; review, E.B, M.B. and T.G.; writing—editing, M.B., T.G. and E.B.; visualisation, M.B.; supervision, E.B.; project administration, E.B.; funding acquisition, E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been conducted in the context of the "diresCity" project, "Applied Methods for Digital and Resilient Cities", funded by the German Aerospace Center (DLR). We acknowledge support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG – German Research Foundation) and the Open Access Publishing Fund of Hochschule Darmstadt – University of Applied Sciences.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilised in this study is sourced from OpenStreetMap and detailed descriptions of its usage are provided within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of Grammarly, ChatGPT and DeepL for enhancing grammar and sentence coherence. All content, interpretations, and conclusions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. The disaster risk reduction (DRR) glossary, 2022.

- Federal Ministry of the Interior (Germany). National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP Strategy), 2009.

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Guide to Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, 2019.

- Fekete, A. Critical infrastructure cascading effects. Disaster resilience assessment for floods affecting city of Cologne and Rhein-Erft-Kreis. Journal of Flood Risk Management 2020, 13, e312600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara Valencia. Valencia Chamber report on damages in the 87 industry municipalities affected by DANA. Informe de Cámara Valencia sobre daños en la industria de los 87 municipios afectados por la DANA., 2024.

- Ouyang, M. Review on modeling and simulation of interdependent critical infrastructure systems. Reliability engineering & System safety 2014, 121, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, D.; Stursberg, P.; Metzger, M.; Steinke, F. Representing topology uncertainty for distribution grid expansion planning. CIRED 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierich, A.; Tzavella, K.; Setiadi, N.J.; Fekete, A.; Neisser, F.M. Enhanced Crisis-Preparation of Critical Infrastructures through a Participatory Qualitative-Quantitative Interdependency Analysis Approach. ISCRAM 2019, 16, 1226–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard, T.; Tundis, A.; Steinke, F. Automated Generation of Urban Medium-voltage Grids using OpenStreetMap Data. 2024 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe) 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brucherseifer, E.; Winter, H.; Mentges, A.; Mühlhäuser, M.; Hellmann, M. Digital Twin conceptual framework for improving critical infrastructure resilience. at - Automatisierungstechnik 2021, 69, 1062–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhard, T.; Sattler, B.J.; Gunkel, J.; Marquard, M.; Tundis, A. Improving the resilience of socio-technical urban critical infrastructures with digital twins: Challenges, concepts, and modeling. Sustainability Analytics and Modeling 2025, 5, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baecker, B.R.; Candas, S.; Tepe, D.; Mohapatra, A. Generation of low-voltage synthetic grid data for energy system modeling with the pylovo tool. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks, 2025; 101617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheggen, L.; Ferdinand, R.; Moser, A. Planning of low voltage networks considering distributed generation and geographical constraints. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Energy Conference (ENERGYCON). IEEE; 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlömer, G.; Blaufuß, C.; Hofmann, L. Modelling of Low-Voltage Grids with the Help of Open Data. In Proceedings of the NEIS Conference 2016: Nachhaltige Energieversorgung und Integration von Speichern. Springer; 2017; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, A.; Daneshvar, M.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Energy Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence for Energy Management. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banze, T.; Kneiske, T.M. Open data for energy networks: introducing DAVE—a data fusion tool for automated network generation. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, H.O.; Desuó, L.; de SS Fogliatto, M.; Ribeiro, V.P.; Balestieri, J.A.; Maciel, C.D. A Bayesian Hierarchical Model to create synthetic Power Distribution Systems. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 235, 110706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugl, R.; Wogrin, S.; Bachhiesl, U.; Frauenlob, L. GridTool: An open-source tool to convert electricity grid data. SoftwareX 2023, 21, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medjroubi, W.; Müller, U.P.; Scharf, M.; Matke, C.; Kleinhans, D. Open data in power grid modelling: new approaches towards transparent grid models. Energy Reports 2017, 3, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, H.K.; Janecke, L.; Weber, M.; Hagenmeyer, V. An optimization-based approach for automated generation of residential low-voltage grid models using open data and open source software. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitkoetter, W.; Medjroubi, W.; Vogt, T.; Agert, C. Comparison of open source power grid models—combining a mathematical, visual and electrical analysis in an open source tool. Energies 2019, 12, 4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, C.M.; San Roman, T.G.; Sanchez-Miralles, A.; Gonzalez, J.P.P.; Martinez, A.C. A reference network model for large-scale distribution planning with automatic street map generation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2010, 26, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisse, J.M.; Braun, M.; Letzgus, S.; Kneiske, T.M. A GIS-Based planning approach for urban power and natural gas distribution grids with different heat pump scenarios. Energies 2020, 13, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, D.; Stursberg, P.; Metzger, M.; Steinke, F. Learning probability distributions over georeferenced distribution grid models. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 235, 110636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency, E. CORINE Land Cover - European Union’s Copernicus land monitoring service information, Report, 2018.

- Loga, T.; Stein, B.; Diefenbach, N.; Born, R. Deutsche Wohngebäudetypologie. Technical report, Institut Wohnen und Umwelt GmbH, zweite erweiterte Auflage, 2015.

- Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. Zensus 2011: Vielfältiges Deutschland, 2016.

- Wille-Haussmann, B.; Fischer, D.; Köpfer, B.; Bercher, S.; Engelmann, P.; Ohr, F. Synthetische Lastprofile für eine effiziente Versorgungs-planung für Nicht-Wohngebäude. Fraunhofer ISE 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamwi, A.; Medjroubi, W.; Vogt, T.; Agert, C. OpenStreetMap data in modelling the urban energy infrastructure: a first assessment and analysis. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülk, L.; Wienholt, L.; Cußmann, I.; Müller, U.P.; Matke, C.; Kötter, E. Allocation of annual electricity consumption and power generation capacities across multiple voltage levels in a high spatial resolution. International Journal of Sustainable Energy Planning and Management 2017, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamwi, A.; Medjroubi, W.; Vogt, T.; Agert, C. Development of a GIS-based platform for the allocation and optimisation of distributed storage in urban energy systems. Applied Energy 2019, 251, 113360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Wang, Z.; Mao, D.; Guan, K.; Jia, M.; Chen, C. Mapping the essential urban land use in changchun by applying random forest and multi-source geospatial data. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amme, J.; Pleßmann, G.; Bühler, J.; Hülk, L.; Kötter, E.; Schwaegerl, P. The eGo grid model: An open-source and open-data based synthetic medium-voltage grid model for distribution power supply systems. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing; 2018; Vol. 977, p. 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, J.; Pfeifer, P.; Wirtz, C.; Wursthorn, D.; Vennegeerts, H.; Moser, A. Modelling of synthetic power distribution systems in consideration of the local electricity supply task. In Proceedings of the Cired. AIM; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kays, J.; Seack, A.; Smirek, T.; Westkamp, F.; Rehtanz, C. The generation of distribution grid models on the basis of public available data. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2016, 32, 2346–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. Monitoring the adequacy of resources in European electricity markets. Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection (bmwk) 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Research Department. Electricity consumption in Germany from 2000 to 2022. Statista 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.D.; Zimmerman, Z.; Gramlich, R. Strategic Industries surging: Driving Us Power Demand. Grid Strategies, LLC, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Diahovchenko, I.; Petrichenko, R.; Petrichenko, L.; Mahnitko, A.; Korzh, P.; Kolcun, M.; Čonka, Z. Mitigation of transformers’ loss of life in power distribution networks with high penetration of electric vehicles. Results in Engineering 2022, 15, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechter, R. Constraint processing; Morgan Kaufmann, 2003.

- Sapena, O.; Onaindia, E.; Garrido, A.; Arangu, M. A distributed CSP approach for collaborative planning systems. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2008, 21, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).