1. Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common form of cancer with almost 2.5 billion cases reported just in 2024 globally and 1.8 billion deaths [

1]. According to GLOBOCAN projections, the cancer burden in India is poised for a substantial increase, with estimates suggesting a 57.5% rise in cancer cases by 2040 compared to 2020, reaching an estimated 2.08 million cases [

2]. Therefore, Bronchogenic carcinoma, a formidable adversary in the global health landscape, casts a long shadow of mortality. This insidious malignancy, often detected at advanced stages, underscores the urgent need for innovative diagnostic strategies. The etiology of lung cancer is multifaceted, encompassing a confluence of risk factors, including the ubiquitous exposure to tobacco smoke, the insidious influence of genetic predispositions, and the insidious impact of environmental pollutants such as occupational hazards, air pollution, and the ubiquitous presence of radon.

Projections suggest a notable increase in cancer incidence in India, with a forecasted 12.8% rise expected by 2025 compared to 2020. This anticipated surge underscores the critical need for enhanced cancer prevention and control strategies within the Indian context [

2].

Recognizing this urgent need, a deeper understanding of the disease biology is paramount.

By meticulously analyzing the microscopic appearance of lung tumors, researchers gain valuable insights into the diverse subtypes of lung cancer, their growth patterns, and their potential responses to treatment. This knowledge forms the foundation for developing more effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to combat this devastating disease. From a histopathological perspective, lung cancers exhibit diverse morphologies.

Broadly categorized into two primary subtypes, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC), these entities diverge significantly in their biological behavior and clinical management. NSCLC, encompassing approximately 80-85% of all lung cancer cases, presents a heterogeneous spectrum, encompassing squamous cell carcinoma, characterized by the formation of squamous cells, large cell carcinoma, distinguished by its pleomorphic appearance, and adenocarcinoma, the most prevalent subtype, often arising from the peripheral lung. SCLC, constituting the remaining 15-20%, exhibits aggressive characteristics, characterized by rapid growth and a propensity for early metastasis [

3].

The distinct morphological features observed in lung cancer, such as the presence of atypical cells, variations in tissue architecture, and the degree of cellular differentiation, provide valuable clues for pathologists. These observations, however, require further confirmation through conventional diagnostic techniques. This multi-pronged approach ensures accurate disease characterization, essential for guiding appropriate treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes.

However, conventional diagnostic approaches for lung cancer which include chest X-ray, CT scan, PET scan, bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, and needle aspiration., while valuable, present limitations in terms of invasiveness and potential for early detection. The emergence of liquid biopsies, offering a minimally invasive window into the patient’s biological state, has revolutionized cancer research and diagnostics.

Table 1.

Conventional ways of lung cancer detection using quantitative perspective based on the data collected from recent studies [

4].

Table 1.

Conventional ways of lung cancer detection using quantitative perspective based on the data collected from recent studies [

4].

Conventional Diagnostic Approaches for Lung Cancer: A Quantitative Perspective

|

|

•

Chest Radiography:

|

|

○

Sensitivity: 15-20%

|

|

○

Specificity: High, but limited by operator variability.

|

|

•

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

|

|

○

Sensitivity:

|

|

■

Low-dose CT screening:

|

|

■

Detects approximately 15-20% of lung cancers.

|

|

■

High false-positive rates (around 96% of detected nodules are benign).

|

|

■

Helical CT scan:

|

|

■

Higher sensitivity for detecting lung nodules (around 90%).

|

|

○

Specificity: Moderate to high, depending on nodule characteristics and image interpretation.

|

|

• Bronchoscopy:

|

|

○

Sensitivity: Highly variable depending on the location and size of the tumor.

|

|

■

Can be as low as 40% for peripheral lesions.

|

|

○

Specificity: Generally high, but can be affected by operator expertise and sampling technique.

|

|

•

Sputum Cytology:

|

|

○

Sensitivity: Low (around 20-40%)

|

|

○

Specificity: Moderate

|

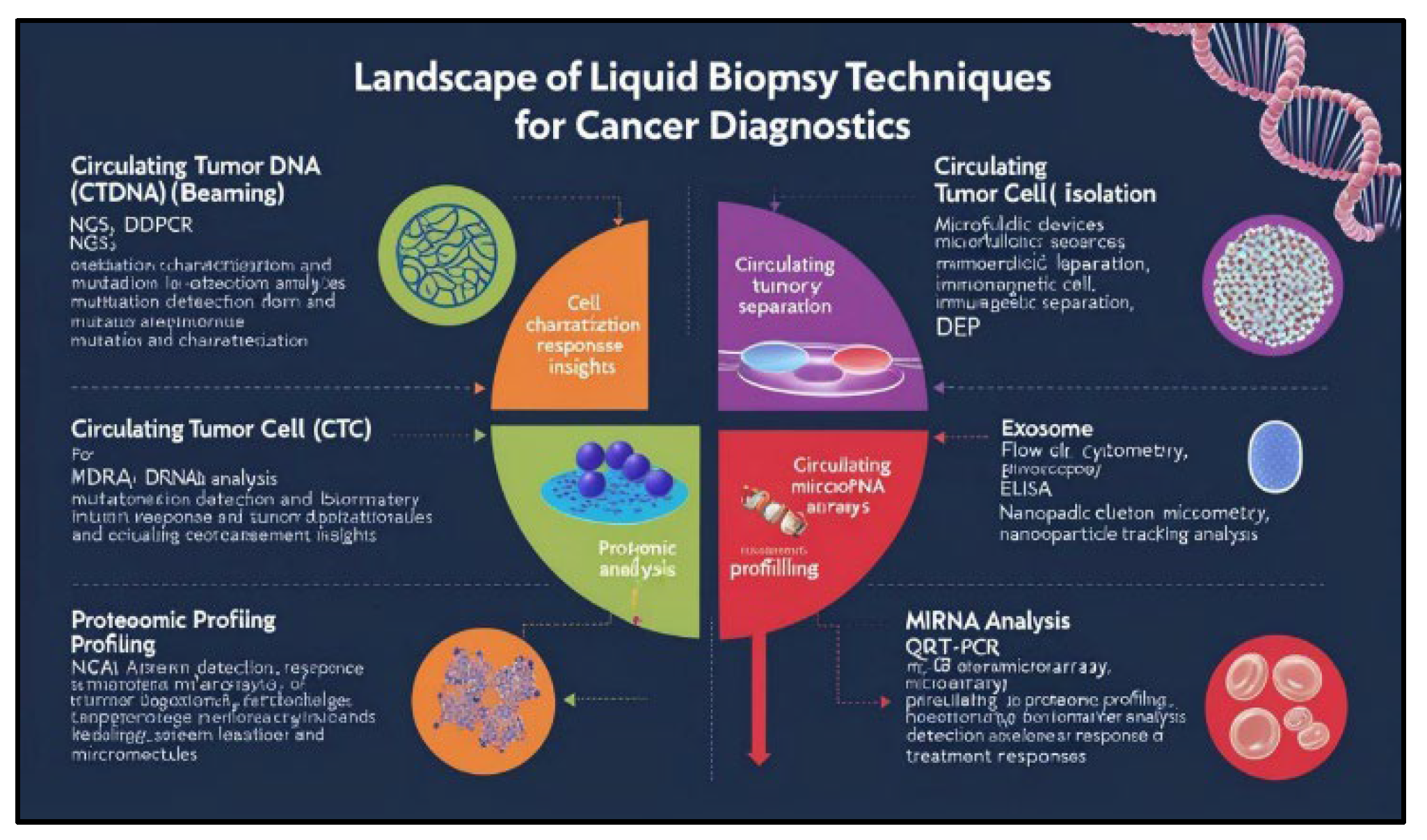

So, the landscape of lung cancer diagnosis has witnessed a paradigm shift with the advent of liquid biopsy techniques. These minimally invasive approaches offer a valuable alternative to traditional tissue biopsies, enabling the analysis of circulating tumor-derived components within bodily fluids such as blood, plasma, and pleural fluid often called biological markers. A diverse array of sophisticated techniques has been developed for the isolation and characterization of these circulating biomarkers, including:

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis: Techniques such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), digital droplet PCR (ddPCR), and BEAMing (beads, emulsions, amplification, and magnetics) are employed to detect and characterize tumor-specific mutations, copy number variations, and methylation patterns within circulating cell-free DNA.

Circulating Tumor Cell (CTC) isolation: Techniques like microfluidic devices, immunomagnetic separation, and DEP (dielectrophoresis) are utilized to isolate and characterize circulating tumor cells, providing insights into tumor biology and treatment response.

Exosome analysis: Techniques such as flow cytometry, electron microscopy, and nanoparticle tracking analysis are employed to isolate and characterize exosomes, which carry valuable information about tumor-derived proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids.

Proteomic profiling: Techniques such as ELISA, mass spectrometry, and protein microarrays are used to analyze circulating protein biomarkers, including tumor-associated antigens, cytokines, and growth factors.

miRNA analysis: Techniques such as qRT-PCR, microarrays, and NGS are used to detect and quantify circulating microRNAs, which have been shown to play critical roles in tumorigenesis and metastasis.

Figure 1.

landscape for analytical techniques for cancer diagnostics for various biomarkers detected in lung cancer.

Figure 1.

landscape for analytical techniques for cancer diagnostics for various biomarkers detected in lung cancer.

These innovative techniques, coupled with advancements in bioinformatics and data analysis, are paving the way for a new era of personalized lung cancer medicine. By leveraging the power of liquid biopsies, researchers and clinicians can gain deeper insights into the complex biology of lung cancer, enabling early detection, improved risk stratification, and the development of more effective and targeted therapies [

5].

3. Novel Biomarkers in the Study of Lung Cancer Through Liquid Biopsies: An Early Detection for the Disease

Conventional diagnostic and prognostic approaches for lung cancer, such as imaging modalities (e.g., CT scans) and tissue biopsies, while valuable, present inherent limitations. These limitations include, but are not limited to, invasiveness, potential for complications, patient discomfort, and the risk of radiation exposure. Moreover, the inherent heterogeneity of tumor tissue can introduce significant diagnostic bias. Consequently, the development of non-invasive biomarkers for lung cancer has emerged as a critical research priority [

6,

7].

Biomarkers are biological indicators which are present in the body fluids like serum, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, saliva, sputum and tissues. These are extensively studied aspects of biology when taken into account the diagnostic and prognostic properties of a particular disease. They can be considered as “signposts” within our biological systems, providing clues about a wide range of conditions, from the onset of a disease to the effectiveness of a particular treatment.

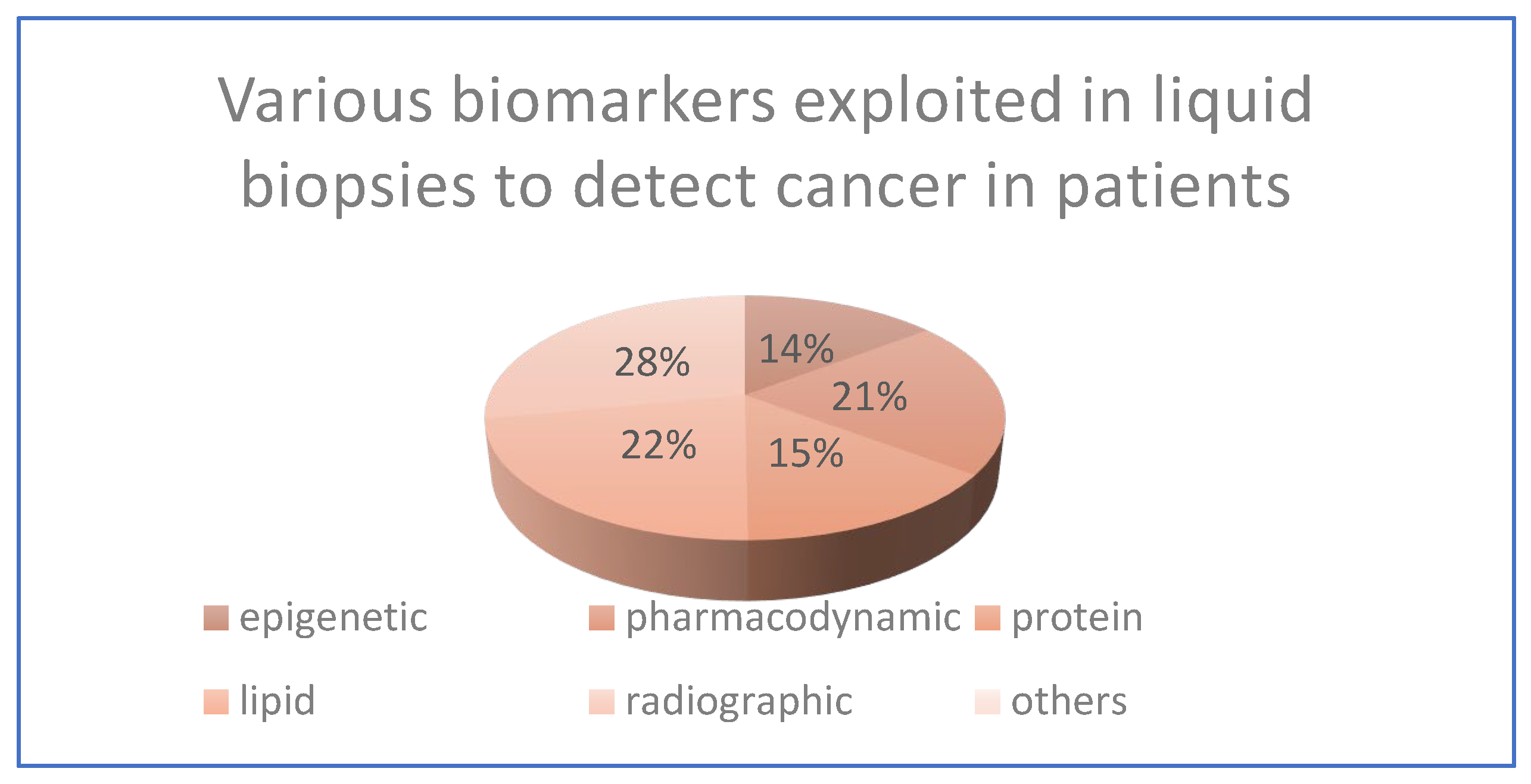

These encompass a wide range of biological indicators, including epigenetic, pharmacodynamic, protein, lipid, radiographic, and numerous other physiologic and histologic markers, based on various aspects like classification by biological origin, by clinical application, by analytical method, by source. used to assess various aspects of health and disease.

Figure 2.

The above pie-chart has been created according to the data received from various scholarly articles and across the web.

Figure 2.

The above pie-chart has been created according to the data received from various scholarly articles and across the web.

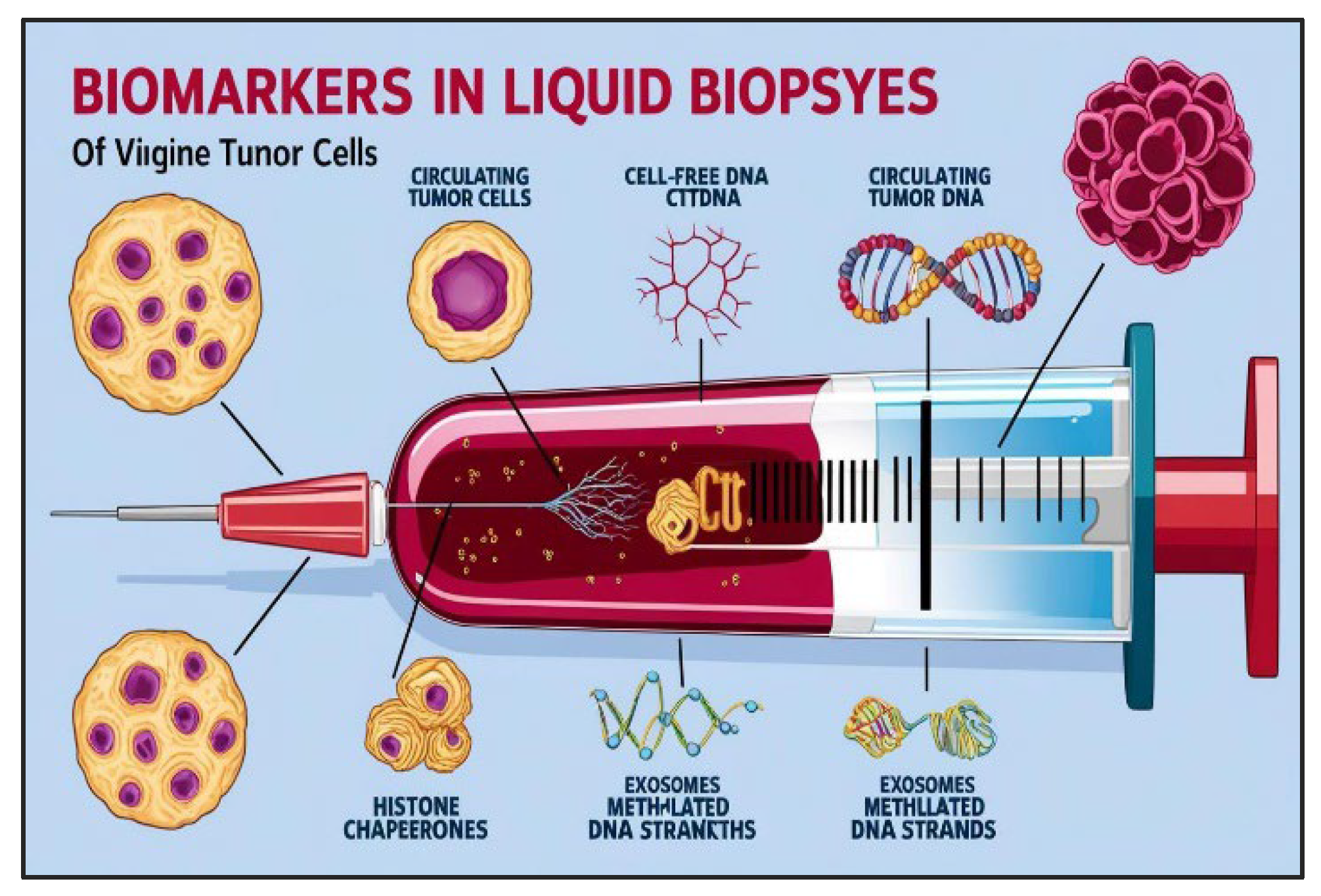

Figure 3.

Analyzing various biomarkers for lung cancer detection through liquid biopsies.

Figure 3.

Analyzing various biomarkers for lung cancer detection through liquid biopsies.

A plethora of potential biomarkers have been identified within the liquid biopsy landscape, encompassing a diverse array of molecular entities. These include circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), proteins, lipids, various RNA species, including microRNAs (miRNAs), and other circulating biomolecules. The feasibility of detecting and quantifying these biomarkers has been significantly enhanced by the advent of sophisticated analytical techniques, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), next-generation sequencing, and microfluidic-based platforms [

8].

Not to our surprise, the dynamic nature of lung cancer, characterized by genomic instability and continuous evolutionary pressures, poses a significant challenge. This inherent heterogeneity within the tumor microenvironment can lead to substantial variability in biomarker expression levels, necessitating the identification of robust and reliable biomarkers for accurate and clinically meaningful assessments. And in this continuous search of biomarkers, the promising advent of histone chaperones offer great potential in lung cancer research. These proteins, which are necessary for coordinating chromatin dynamics, play an important role in regulating gene expression and maintaining genomic stability as well. Dysregulation of these proteins is now widely recognized as a major contributor to oncogenesis. This review looks at the burgeoning topic of circulating histone chaperones as new biomarkers for lung cancer detection in liquid biopsies.

Beyond the recognized area of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating exosomes, a diverse population of extracellular vesicles containing a distinct cargo of proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids that reflect the tumor microenvironment, are among the most promising candidates in the race of search for biomarkers to be exploited in lung cancer detection by liquid biopsies. To add on to this, studies on the involvement of circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing certain miRNAs, such as miR-21 and miR-155, have yielded promising findings in distinguishing malignant from benign lung nodules. Furthermore, the discovery of circulating immune cell subsets in liquid biopsies, notably tumor-associated macrophages and regulatory T-cells, provides important information about the tumor-immune milieu and may serve as prognostic indications. These new techniques are still under investigation, hold the potential to revolutionize lung cancer diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies [

9,

10]. While examining cellular biomarkers provides valuable clues about the cellular processes involved in lung cancer, delving into the realm of DNA biomarkers offers a deeper layer of understanding, revealing the genetic alterations that drive tumor development and progression.

3.1. cfDNA or Cell Free Deoxyribonucleic Acids

The emergence of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as a readily accessible biomarker in liquid biopsies has revolutionized the landscape of lung cancer diagnostics. Recent studies have demonstrated the remarkable potential of cfDNA analysis in reflecting the tumor’s genetic landscape, enabling the detection of actionable mutations such as EGFR, KRAS, and ALK rearrangements with high sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, cfDNA analysis offers invaluable insights into tumor evolution, facilitating real-time monitoring of treatment response, predicting disease recurrence, and identifying emerging resistance mechanisms. This dynamic interplay between the tumor and the circulating milieu provides a unique opportunity to personalize treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes [

11].

3.2. ctDNA, CTCs

The presence of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) fragments within the venous bloodstream holds immense promise for early lung cancer detection. These fragments, originating from tumor cells undergoing necrosis or apoptosis, are released into the circulation, carrying with them the genetic imprints of the malignancy.

Recently, advancements in sensitive molecular techniques have enabled the detection and characterization of these miniscule DNA fragments, offering a unique window into the tumor’s genetic landscape. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the detection rate of ctDNA in plasma can exceed 80%, establishing its potential as a valuable diagnostic tool, particularly in scenarios where tissue biopsies are challenging or contraindicated [

12].

The significance of ctDNA analysis extends beyond diagnosis. It allows for the identification of crucial oncogenic drivers, including mutations in genes such as EGFR, KRAS, ERBB2, and BRAF, as well as gene rearrangements involving EML4-ALK, ROS1, NTRK1/2, and RET. Notably, ctDNA analysis can detect exon skipping alterations and gene amplifications, such as those observed in MET amplification, providing invaluable insights for personalized treatment decisions [

13].

By analyzing these genetic alterations in ctDNA, clinicians can tailor treatment strategies, select targeted therapies, and monitor treatment response in real-time. This approach offers the potential for improved patient outcomes by enabling early intervention and personalized medicine for individuals afflicted with lung cancer.

Besides this, circulating tumor cells (CTCs) represent a captivating window into the metastatic cascade, arising from the detachment of malignant cells from the primary tumor mass. This detachment, orchestrated by a complex interplay of mechanical forces and alterations in cell adhesion molecules, enables these rogue cells to embark on a perilous journey through the circulatory system. The presence of these metastatic sentinels within the peripheral blood has emerged as a significant prognostic indicator, reflecting the dynamic interplay between the tumor and its microenvironment [

14].

Indeed, compelling evidence suggests an association between CTC burden and disease progression in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A seminal study unveiled a noteworthy observation: patients grappling with metastatic NSCLC and experiencing disease progression exhibited a discernible elevation in the expression of genes implicated in tumor aggressiveness within their circulating tumor cells. Specifically, these patients demonstrated heightened expression levels of genes such as PIK3CA, AKT2, TWIST, and ALDH1, suggesting a potential role for these genes in driving metastatic dissemination and conferring a more aggressive phenotype upon the circulating tumor cells [

15].

Even though these biological indicators are very well exploited in terms of liquid biopsy assays, the need for revolution never ends. From the advent of ctDNA and CTCs to the discovery of new biomarkers daily is the need of an hour. Recent studies on accessory biomolecules have become a promising boon to the humanity. Histone chaperones thus come to the role.

Histone chaperones are accessory proteins in the nucleus of the cell which are associated with the histone proteins and negatively charged chromatin. It is an essential aspect studied during association and dissociation of chromatin material with the histone protein to form nucleosomes. Histone proteins are basic proteins which help in the binding of negatively charged DNA around it. The histone is an octamer of four types of core proteins, H2A, H2B, H3, H4. Histone chaperones help in regulating the machinery of histone proteins [

16].

The review discusses the recent advances in understanding the release of histone chaperones while circulation exploiting their potential as diagnostic and prognostic indications, technological difficulties, and future possibilities in this exciting field. A thorough review was conduct on circulating histone chaperones in lung cancer, focusing on their ability to distinguish malignant from benign situations and forecast disease progression [

17].

| A recent study: |

| Building upon recent investigations that have delved into the intricate epigenetic landscape of small cell lung cancer (SCLC), this study employed a novel, bisulfite-free, enrichment-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) approach, termed T7-MBD-seq, to comprehensively evaluate genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in this aggressive malignancy. This innovative methodology, incorporating an in-house library preparation strategy, enabled efficient sample multiplexing prior to enrichment, thereby facilitating the analysis of limited sample material. Notably, T7-MBD-seq demonstrated exceptional sensitivity, yielding reproducible methylation profiles with DNA inputs as low as 1 ng. To validate the efficacy of this approach, T7-MBD-seq was initially applied to a cohort encompassing 110 samples, comprising 97 samples derived from patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) or circulating tumor cell-derived explant (CDX) models (representing 50 preclinical models from 33 unique patients) and 13 samples of healthy lung tissue. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed a distinct separation between SCLC models and healthy lung controls, highlighting the discriminatory power of this approach. Consistent with previous observations, SCLC samples exhibited greater DNA methylation heterogeneity compared to healthy lung tissue, underscoring the dynamic epigenetic landscape of this malignancy. Notably, approximately 75% of the identified differentially methylated regions (DMRs) mapped to CpG islands, shores, or shelves, suggesting a significant impact of DNA methylation on gene regulation within these genomic regions. The majority of DMRs identified in SCLC were hypermethylated, a finding consistent with the enrichment strategy employed, which preferentially captures CpG-dense regions. Importantly, methylation profiles generated using T7-MBD-seq demonstrated strong concordance with previously reported methylation patterns in SCLC primary tumors and healthy lung tissue profiled on the Illumina Human Methylation 450k platform, further validating the robustness and accuracy of this approach [18]. |

3.3. Histone Chaperones

Chaperone in past was regarded to the old woman usually who served the princesses and always stayed with her. It originally meant to regard a woman whose duty was to accompany a younger woman. Let us relate histone proteins to be princesses of the nucleus, histone chaperones are the accessory proteins which serve the histone protein and serve to be the essential elements for the assembly and disassembly of chromatin fibers around the positively charged histone protein. In addition, histone chaperones help in regulating the replication of DNA independently or by coupling mechanisms. These help in the repair of genetic material thereby reducing genetic alterations. But in case if this mechanism is failed upon to be done on time, this can cause diseases like cancer. Additionally, these participate in biogenesis, transportation and other cellular mechanisms. Dysregulation of histone chaperone activity can have profound consequences, contributing to a spectrum of human diseases, including cancer. Aberrant expression or function of these proteins can disrupt chromatin architecture, leading to aberrant gene expression, genomic instability, and ultimately, uncontrolled cell growth [

19].

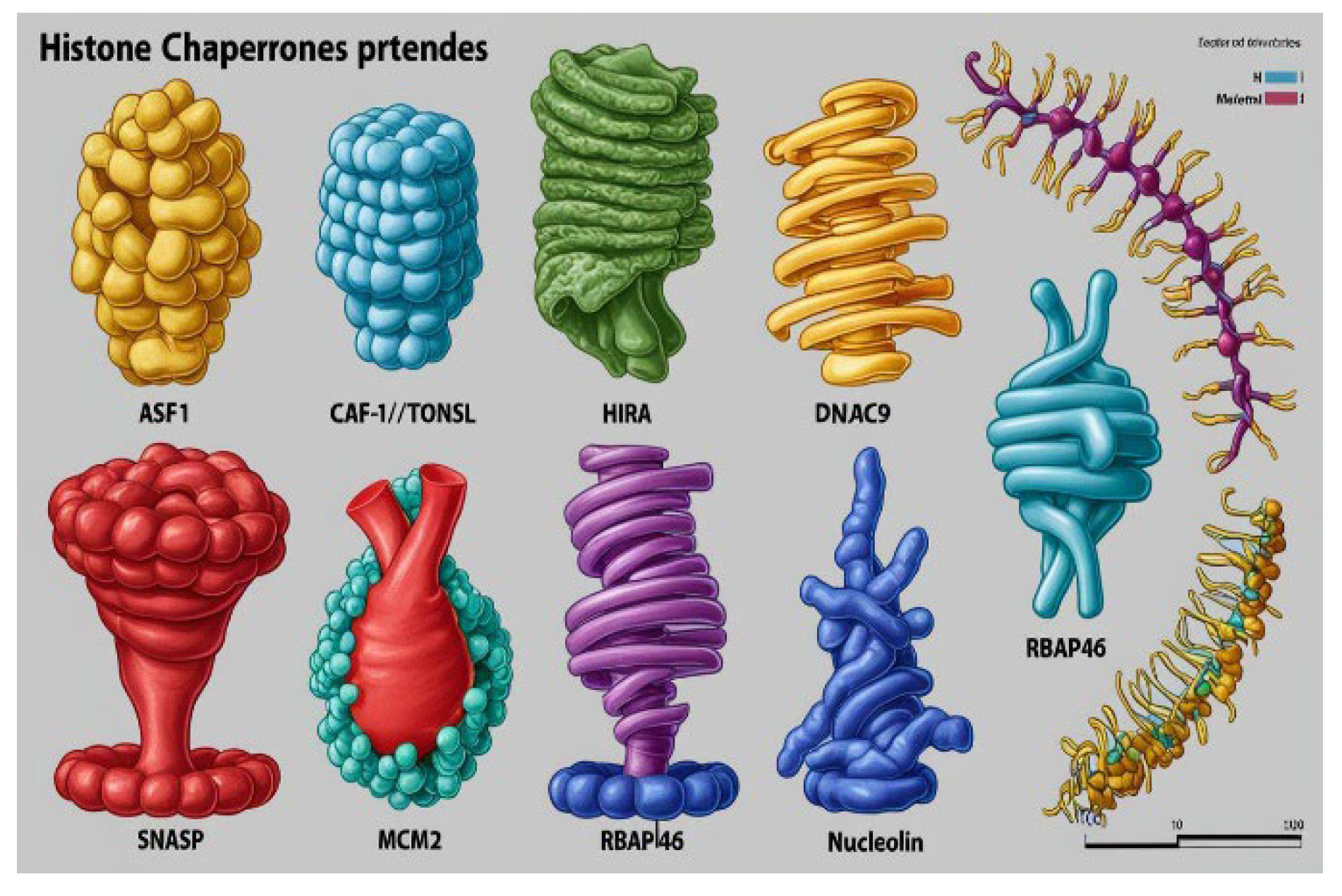

Figure 4.

Histone Chaperones.

Figure 4.

Histone Chaperones.

A negatively charged piece of DNA or chromatin fiber is coiled with the histone protein octamer composed of four types of histones basically H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 to form nucleosomes which are also called the beads on the string where string refers to the chromatin fibers. The histone octamer along with the chromatin fiber is the building block of genetic epitome of the cells, but even after being much essential in packing of the genetic material, nucleosomes prove to be a constant barrier in replication, transcription, and other molecular activities of the DNA, here histone chaperones play a vital role. These proteins help in the peeling of DNA, therefore are commonly referred to as the peelers of genetic material [

20].

There are several histone chaperones regulating different mechanisms in the body, some of them are: ASF1, CAF-1/TONSL, HIRA, DNAJC9, HJURP, sNASP, MCM2, RBAP46, nucleoplasmin and nucleolin etc. Beyond their expertise in nuclear assembly and disassembly, emerging evidence suggests that histone chaperones may also serve as valuable biomarkers in lung cancer, offering novel insights into disease progression and treatment response.

3.3.1. Promising Future of Histone Chaperones as Biomarkers

Studies have shown altered expression levels of certain histone chaperones (such as CAF-1, HIRA, and ASF-1) in lung cancer tissues compared to normal lung tissues. This suggests that histone chaperone dysregulation may contribute to lung cancer development and progression [

21].

Even though histone chaperones play crucial roles in chromatin remodeling, gene expression, and DNA repair, dysregulation of these processes is a hallmark of cancer. Therefore, altered histone chaperone function could contribute to tumorigenesis by:

Altering gene expression patterns: Leading to the activation of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes [

22].

Promoting genomic instability: Disrupting DNA repair mechanisms and increasing the accumulation of mutations [

22].

Contributing to cellular transformation: Promoting uncontrolled cell growth, invasion, and metastasis [

22].

3.3.2. Emerging Evidence of Circulating Histones and Nucleosomes:

Studies have demonstrated the presence of circulating histones and nucleosomes in the blood of cancer patients, including those with lung cancer.

These circulating nucleosomes can carry tumor-derived DNA, which can be analyzed for mutations and other molecular alterations.

While direct studies on circulating histone chaperones in lung cancer are limited, these findings suggest that circulating components of the chromatin machinery may reflect tumor burden and disease activity [

23].

The histone chaperone complex FACT is often upregulated in various cancers. However, apart from being highly condensed forms of proteins associated with the DNA and genes, these complexes show high dynamicity if looked over upon as biomarkers [

24]. FACT, a protein complex essential for transcription, assists RNA polymerase II in navigating the challenging chromatin landscape. While models suggest FACT can either globally alter nucleosome accessibility or induce local destabilization by displacing H2A/H2B dimers, our study provides new insights. We demonstrate that H2A/H2B dimers are crucial for FACT’s function. Through a series of in vitro experiments, we show that FACT facilitates the transition of RNA polymerase II from a stalled state to an active state of transcription. This dynamic interplay, likely involving repeated interactions between FACT and H2A/H2B dimers, not only enhances transcriptional efficiency but also ensures the preservation of chromatin structure during this crucial process [

25].

Besides just DNA biomarkers certain ribonucleic acids also serve to be a great platform of research and a few biomarkers have been identified as well. Some amongst them can be long non coding RNA:

3.4. Long Non-Coding RNA LINC01929

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) constitute a distinct class of RNA molecules that diverge significantly from their protein-coding counterparts, such as messenger RNA (mRNA). Unlike mRNA, which serves as the blueprint for protein synthesis, translating genetic information into functional proteins, lncRNAs exhibit a diverse repertoire of functions that extend beyond the realm of protein translation [

26].

Previous studies have implicated LINC01929 as a dysregulated gene in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

6]. Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that aberrant LINC01929 expression may serve as a valuable prognostic indicator in this malignancy. To investigate this hypothesis, the present study examined the expression levels of LINC01929 in NSCLC tissues and compared them to adjacent healthy tissue samples. Furthermore, the study explored the potential clinical significance of LINC01929 expression by correlating its levels with relevant clinical parameters, such as tumor stage and grade, and assessing its impact on patient survival. Additionally, the functional role of LINC01929 was investigated by examining the effects of LINC01929 knockdown on its target miRNA expression in lung cancer cell lines [

27].

Even though the existing biomarkers provide a strong framework of research and diagnostic potentials, yet new biomarkers are needed to be identified daily to increase disease diagnostic and prognostic accuracy. Besides DNA, the accessory proteins associated with them also can be used to diagnose the disease accuracy.

4. Circulating Histone Chaperones and Their Evidence as Cancer Biomarkers: A Study Already Done

Studies have shown, Histone chaperones like CALML3-AS1 are found upregulated in the cells and tissues specifically non-small cell lung cancer. Their silencing can definitely reduce the malignancies of cancer. However, their role in small cell lung cancer developmental studies is still unclear.

According to studies, these histone chaperones along with the histone protein and other mutated DNA cut fragments which are causing lung cancer in patients are circulating in the body fluids like blood. This venous blood when syringed out will contain the histone chaperones specifically AS1, which will be high in quantity in the patients but might be downregulated in normal human population [

28].

Validating it with “The presence of circulating ASF1 in conjunction with other biomarkers, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or circulating tumor cells (CTCs),” may enhance the diagnostic accuracy and prognostic utility for lung cancer.

4.1. Establish Circulating Histone Chaperone Profiles as Sensitive and Specific Indicators for the Early Identification of Lung Cancer

Histone chaperones like ASF1B, have its role still to be defined in lung cancer detection using liquid biopsies. Studies relate to their elevated amounts in plasma circulating freely can be a parameter to judge lung cancer still remains a mystery.

4.2. Investigate the Prognostic Value of These Profiles in Predicting Disease Progression and Patient Outcomes

This study aims at the point that circulating levels of the histone chaperone ASF1, a key regulator of chromatin dynamics, are significantly elevated in the venous blood of patients with Adenocarcinoma (ADC) of the lung. This elevation reflects the dynamic interplay between tumor growth, cellular turnover, and the release of cellular debris within the complex milieu of the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, it is postulated that these elevated ASF1 levels may serve as a harbinger of disease progression, offering valuable insights into the patient’s clinical trajectory, including overall survival, progression-free survival, and responsiveness to therapeutic interventions [

29].

Experimental findings have already demonstrated that silencing CALML3-AS1 significantly suppressed the malignant behavior of SCLC cells, manifesting as a reduction in cell proliferation, colony formation, migratory and invasive capacities, and the formation of spheroids. Concomitantly, a concomitant decrease in the expression of stemness marker proteins was observed [

30].

Drawing upon a comprehensive review of existing literature, our research posits that circulating levels of histone chaperone ASF1 are significantly elevated in the venous blood of patients with Adenocarcinoma (ADC) of the lung. This elevation likely reflects the dynamic interplay between tumor growth, cellular turnover, and the release of cellular debris within the complex microenvironment of the growing tumor. Moreover, this study aims to investigate the prognostic significance of these elevated ASF1 levels in predicting the clinical trajectory of lung adenocarcinoma, with a particular focus on stratifying patients based on their risk of disease progression, overall survival, and responsiveness to therapeutic interventions [

31].

Studies have revealed a significant upregulation of RBBP4 expression in NSCLC, a trend observed across multiple independent studies. This elevated RBBP4 expression was strongly associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes, including reduced overall survival and an increased risk of disease progression. Mechanistically, RBBP4 knockdown was observed to induce autophagic cell death in NSCLC cell lines, suggesting a potential tumor-suppressive role for this protein. These collective findings position RBBP4 as not only a potential prognostic biomarker for NSCLC but also as a promising therapeutic target for the development of novel anti-cancer strategies [

32].

4.3. Analytical Techniques Employed to Detect Lung Cancer Using Liquid Biopsies and the Intervention of ASF1: The Histone Chaperone

A diverse array of sophisticated techniques, including quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), western blotting, droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), microfluidic platforms, and next-generation sequencing technologies, are currently employed for the isolation and characterization of liquid biopsy components in lung cancer research [

33].

5. Discussion

The journey of exploring circulating histone chaperones as lung cancer biomarkers has been a fascinating one, mirroring the dynamic nature of the disease itself. Early studies hinted at the potential of these proteins in reflecting chromatin alterations within the tumor microenvironment. However, many questions remain unanswered [

1,

2].

One of the biggest challenges lies in understanding the precise mechanisms that govern the release of histone chaperones into the bloodstream. Do they originate directly from tumor cells? Are they released by immune cells interacting with the tumor? Or are they a product of systemic inflammation triggered by the malignancy? Deciphering these intricate pathways is crucial for interpreting circulating chaperone levels accurately.

In addition to this, while studies have shown altered levels of certain chaperones in lung cancer, translating these findings into clinically meaningful biomarkers remains a significant hurdle. We need to establish robust and reproducible assays for detecting and quantifying these proteins in a reliable and cost-effective manner [

3,

4]. Additionally, larger, well-designed studies are necessary to validate these biomarkers in diverse patient populations and to assess their prognostic and predictive value.

Despite these challenges, the potential of circulating histone chaperones as novel diagnostic and prognostic tools is undeniable. Imagine a future where a simple blood test could not only detect lung cancer at its earliest stages but also provide valuable insights into the tumor’s biology and predict its behavior. This would revolutionize patient care, enabling earlier interventions, more personalized treatment strategies, and ultimately, improved outcomes for individuals battling this devastating disease [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

However, it’s crucial to proceed with caution. Overhyping the potential of any new biomarker can lead to false hope and disappointment. Rigorous scientific investigation, coupled with ethical considerations, must guide the development and clinical translation of these promising biomarkers. The story of circulating histone chaperones in lung cancer is still unfolding. It’s a testament to the power of scientific inquiry and the relentless pursuit of better treatments for patients. By embracing the challenges and building upon the successes of past research, we can pave the way for a future where lung cancer is no longer an insurmountable foe [

10,

11,

12].

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this review highlights the emerging role of circulating histone chaperones as promising novel biomarkers in the evolving landscape of lung cancer diagnostics. While the field is still nascent, preliminary evidence suggests that alterations in the levels of circulating histone chaperones, such as ASF1, may reflect the dynamic interplay between tumor growth and the host environment.

Further research is warranted to investigate the specific mechanisms underlying the release of histone chaperones into the circulation and to elucidate their precise role in tumorigenesis. Rigorous validation studies are necessary to establish the clinical utility of circulating histone chaperone profiles as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for lung cancer.

The development of sensitive and specific assays for the detection and quantification of circulating histone chaperones, coupled with advancements in liquid biopsy technologies, will be crucial for translating these findings into clinical practice. Ultimately, the integration of circulating histone chaperone analysis into the diagnostic and prognostic armamentarium for lung cancer holds the potential to revolutionize patient care by enabling early detection, personalized treatment strategies, and improved clinical outcomes.

Author Contributions

AK and SM contributing equally in the preparation of manuscript.

Financial Support

Fund from Institutional grant were utilized

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest

Competing Interests

There is no competing interest

References

- Rosado-De-Christenson, M. L., Templeton, P. A., & Moran, C. A. (1994). Bronchogenic carcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics, 14(2), 429–446. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P., Sathishkumar, K., Chaturvedi, M., Das, P., & Stephen, S. (2022). Cancer incidence estimates for 2022 & projection for 2025: Result from National Cancer Registry Programme, India. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 156(4), 598. [CrossRef]

- Dorantes-Heredia, R., Ruiz-Morales, J. M., & Cano-García, F. (2016). Histopathological transformation to small-cell lung carcinoma in non-small cell lung carcinoma tumors. Translational Lung Cancer Research, 5(4), 401–412. [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, Y., Nakayama, T., Kusunoki, Y., Iso, H., & Suzuki, T. (2008). Sensitivity and specificity of lung cancer screening using chest low-dose computed tomography. British Journal of Cancer, 98(10), 1602–1607. [CrossRef]

- Khan, P., Siddiqui, J. A., Maurya, S. K., Lakshmanan, I., Jain, M., Ganti, A. K., Salgia, R., Batra, S. K., & Nasser, M. W. (2020). Epigenetic landscape of small cell lung cancer: small image of a giant recalcitrant disease. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 83, 57–76. [CrossRef]

- Fass, L. (2008). Imaging and cancer: A review. Molecular Oncology, 2(2), 115–152. [CrossRef]

- Tárnoki, D. L., Karlinger, K., Ridge, C. A., Kiss, F. J., Györke, T., Grabczak, E. M., & Tárnoki, Á. D. (2024). Lung imaging methods: indications, strengths and limitations. Breathe, 20(3), 230127. [CrossRef]

- Kurma, K., Eslami-S, Z., Alix-Panabières, C., & Cayrefourcq, L. (2024). Liquid biopsy: paving a new avenue for cancer research. Cell Adhesion & Migration, 18(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wang, L., Lin, H., Zhu, Y., Huang, D., Lai, M., Xi, X., Huang, J., Zhang, W., & Zhong, T. (2024). Research progress of CTC, ctDNA, and EVs in cancer liquid biopsy. Frontiers in Oncology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., Guo, H., Zhao, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, C., Bu, J., Sun, T., & Wei, J. (2024). Liquid biopsy in cancer current: status, challenges and future prospects. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Boukovala, M., Westphalen, C. B., & Probst, V. (2024). Liquid biopsy into the clinics: Current evidence and future perspectives. The Journal of Liquid Biopsy, 4, 100146. [CrossRef]

- Bamodu, O. A., Chung, C., & Pisanic, T. R. (2023). Harnessing liquid biopsies: Exosomes and ctDNA as minimally invasive biomarkers for precision cancer medicine. The Journal of Liquid Biopsy, 2, 100126. [CrossRef]

- Reina, C., Šabanović, B., Lazzari, C., Gregorc, V., & Heeschen, C. (2024). Unlocking the future of cancer diagnosis – promises and challenges of ctDNA-based liquid biopsies in non-small cell lung cancer. Translational Research, 272, 41–53. [CrossRef]

- Telekes, A., & Horváth, A. (2022). The role of Cell-Free DNA in cancer Treatment decision making. Cancers, 14(24), 6115. [CrossRef]

- Kontic, M., Ognjanovic, M., Jovanovic, D., Kontic, M., & Ognjanovic, S. (2016). A preliminary study on the relationship between circulating tumor cells count and clinical features in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 8(6), 1029–1031. [CrossRef]

- Keck, K. M., & Pemberton, L. F. (2011). Histone chaperones link histone nuclear import and chromatin assembly. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1819(3–4), 277–289. [CrossRef]

- Nair, N., Shoaib, M., & Sørensen, C. S. (2017). Chromatin dynamics in genome stability: roles in suppressing endogenous DNA damage and facilitating DNA repair. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(7), 1486. [CrossRef]

- Chemi, F., Pearce, S. P., Clipson, A., Hill, S. M., Conway, A., Richardson, S. A., Kamieniecka, K., Caeser, R., White, D. J., Mohan, S., Foy, V., Simpson, K. L., Galvin, M., Frese, K. K., Priest, L., Egger, J., Kerr, A., Massion, P. P., Poirier, J. T., . . . Dive, C. (2022). cfDNA methylome profiling for detection and subtyping of small cell lung cancers. Nature Cancer, 3(10), 1260–1270. [CrossRef]

- Avvakumov, N., Nourani, A., & Côté, J. (2011). Histone Chaperones: Modulators of Chromatin marks. Molecular Cell, 41(5), 502–514. [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Ramírez, L., Kann, M. G., Shoemaker, B. A., & Landsman, D. (2005). Histone structure and nucleosome stability. Expert Review of Proteomics, 2(5), 719–729. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Kim, T., & Cho, E. (2024). HIRA vs. DAXX: the two axes shaping the histone H3.3 landscape. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 56(2), 251–263. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Arciga, K., Flores-León, M., Ruiz-Pérez, S., Trujillo-Pineda, M., González-Barrios, R., & Herrera, L. A. (2022). Histones and their chaperones: Adaptive remodelers of an ever-changing chromatinic landscape. Frontiers in Genetics, 13. [CrossRef]

- Holdenrieder, S., Nagel, D., Schalhorn, A., Heinemann, V., Wilkowski, R., Von Pawel, J., Raith, H., Feldmann, K., Kremer, A. E., Müller, S., Geiger, S., Hamann, G. F., Seidel, D., & Stieber, P. (2008). Clinical relevance of circulating nucleosomes in cancer. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1137(1), 180–189. [CrossRef]

- Bi, L., Xie, C., Yao, M., Hnit, S. S. T., Vignarajan, S., Wang, Y., Wang, Q., Xi, Z., Xu, H., Li, Z., De Souza, P., Tee, A., Wong, M., Liu, T., Zhao, X., Zhou, J., Xu, L., & Dong, Q. (2018). The histone chaperone complex FACT promotes proliferative switch of G 0 cancer cells. International Journal of Cancer, 145(1), 164–178. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, F., Kulaeva, O. I., Patel, S. S., Dyer, P. N., Luger, K., Reinberg, D., & Studitsky, V. M. (2013). Histone chaperone FACT action during transcription through chromatin by RNA polymerase II. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(19), 7654–7659. [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J. S., Amaral, P. P., Carninci, P., Carpenter, S., Chang, H. Y., Chen, L., Chen, R., Dean, C., Dinger, M. E., Fitzgerald, K. A., Gingeras, T. R., Guttman, M., Hirose, T., Huarte, M., Johnson, R., Kanduri, C., Kapranov, P., Lawrence, J. B., Lee, J. T., . . . Wu, M. (2023). Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 24(6), 430–447. [CrossRef]

- Pan, T., Wang, H., Wang, S., & Liu, F. (2022). Long Non-Coding RNA LINC01929 facilitates cell proliferation and metastasis as a competing endogenous RNA against MicroRNA MIR-1179 in Non-Small cell lung carcinoma. British Journal of Biomedical Science, 79. [CrossRef]

- Mao, G., & Liu, J. (2024b). CALML3-AS1 enhances malignancies and stemness of small cell lung cancer cells through interacting with DAXX protein and promoting GLUT4-mediated aerobic glycolysis. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 117177. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X., Zhou, M., Zhang, L., Fu, Y., Xu, M., Wang, X., Cui, Z., Gao, Z., Li, M., Dong, Y., Feng, H., Ma, S., & Chen, C. (2022). Histone chaperone ASF1A accelerates chronic myeloid leukemia blast crisis by activating Notch signaling. Cell Death and Disease, 13(10). [CrossRef]

- Mao, G., & Liu, J. (2024). CALML3-AS1 enhances malignancies and stemness of small cell lung cancer cells through interacting with DAXX protein and promoting GLUT4-mediated aerobic glycolysis. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 117177. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H., Mohammadhosseini, M., McClatchy, J., Villamor-Payà, M., Jeng, S., Bottomly, D., Tsai, C., Posso, C., Jacobson, J., Adey, A., Gosline, S., Liu, T., McWeeney, S., Stracker, T. H., & Agarwal, A. (2024). The TLK-ASF1 histone chaperone pathway plays a critical role in IL-1β–mediated AML progression. Blood, 143(26), 2749–2762. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y., Zhang, Z., Yin, A., Su, X., Tang, N., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Chen, W., Wang, J., & Wang, W. (2024). RBBP4: A novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for non-small-cell lung cancer correlated with autophagic cell death. Cancer Medicine, 13(15). [CrossRef]

-

How to detect lung cancer | Lung cancer tests. (n.d.). American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/how-diagnosed.html#:~:text=this%20cancer%20spread.-,Bronchoscopy,to%20create%20a%20virtual%20bronchoscopy.

- Kaur R, Kumar P, Kumar A. Insights on the nuclear shuttling of H2A-H2B histone chaperones. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids [Internet]. 2023;1–13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38133493.

- Gill J, Kumar A, Sharma A. Structural comparisons reveal diverse binding modes between nucleosome assembly proteins and histones. Epigenetics Chromatin [Internet]. 2022;15:20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606827.

- Kumar A, Barve U, Gopalkrishna V, Tandale B V, Katendra S, Joshi MS, et al. Outbreak of cholera in a remote village in western India. Indian J Med Res [Internet]. 2022;156:442–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36751742.

- Garg K, Kumar A, Kizhakkethil V, Kumar P, Singh S. Overlap in oncogenic and pro-inflammatory pathways associated with areca nut and nicotine exposure. Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapy [Internet]. 2023; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2949713223000538.

- Kumar A, Kumar P, Yadav CP, Kumar D. A Comprehensive Quality Management System for Molecular Diagnostic Testing. 2024.

- Kumar P, Dhingra A, Sharma D, Kumar A, Singh S. Microbiome and Development of Ovarian Cancer. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets [Internet]. 2022; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35532247.

- Sajid M, Srivastava S, Kumar A, Kumar A, Singh H, Bharadwaj M. Bacteriome of Moist Smokeless Tobacco Products Consumed in India With Emphasis on the Predictive Functional Potential. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2021;12:784841. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35003015.

- Siddiqui F, Croucher R, Ahmad F, Ahmed Z, Babu R, Bauld L, et al. Smokeless Tobacco Initiation, Use, and Cessation in South Asia: A Qualitative Assessment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research [Internet]. 2021;23:1801–4. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ntr/article/23/10/1801/6222133.

- Kumar A, Sharma D, Aggarwal ML, Chacko KM, Bhatt TK. Cancer/testis antigens as molecular drug targets using network pharmacology. Tumor Biology [Internet]. 2016;37:15697–705. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Mandhan P, Sharma M, Pandey S, Chandel N, Chourasia N, Moun A, et al. A Regional Pooling Intervention in a High-Throughput COVID-19 Diagnostic Laboratory to Enhance Throughput, Save Resources and Time Over a Period of 6 Months. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2022;13:858555. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35756046.

- Deoshatwar A, Salve D, Gopalkrishna V, Kumar A, Barve U, Joshi M, et al. Evidence-Based Health Behavior Interventions for Cholera: Lessons from an Outbreak Investigation in India. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2021;106:229–32. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34695790.

- Viswanathan R, Kumar A. Frontier Warriors—Combating Cholera in Rural India. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2019;100:1071–2. Available from: http://www.ajtmh.org/content/journals/10.4269/ajtmh.19-0027.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).