1. Introduction

Acridocarpus Guill. & Perr. is one of the exceptional genera in the Paleotropics having some floral morphology characteristics (Souto & Oliveira, 2014; da Costa Santos et al., 2023). This genus comprises over thirty species of scandent and erect shrubs able to adapt to arid climates and are distributed in West Africa, East Africa, Madagascar, and New Caledonia (De Almeida et al., 2024). The ethnobotanical use of A. smeathmannii was premised on its use for problems of the reproductive system and its accessory organs (Catarino et al., 2016).

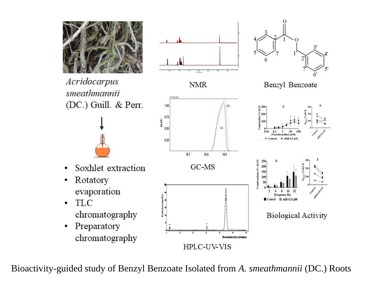

Our previous studies demonstrated the medicinal potential of crude A. smeathmannii root extract to improve reproductive behavior and functions in animal models (Kale et al., 2019a). Also, its toxicological assessment showed that the extract was relatively safe in rodents (Kale et al., 2019b). The structural analysis of this extract revealed a mixture of polyphenols, flavonoids, sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, fatty acids, and benzyl alcohol esters (Kale et al., 2019a). To identify an active principle on a molecular basis, we further purified A. smeathmannii root extract by repeated thin layer chromatography (TLC), column chromatography, and medium pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC). Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC-UV-VIS), and NMR spectroscopy led to the isolation of a natural benzyl benzoate (nBB). The identity was confirmed by comparison with the spectroscopic data of a commercial BB sample. In retrospect, nBB is one of the most abundant components in A. smeathmannii root extracts.

The chemical determination and physicochemical characteristics of BB have been reviewed (Chen et al., 2020; De Meneses et al., 2020; Soszka et al., 2021). BB is one of the popular old drugs known for its spasmolytic effects (Rivero-Cruz et al., 2007) and vasodilation (Orra et al., 2021) respectively. It is naturally found in various essential oils with Peru and Tolu balsams, as well as abundant compound in several plant roots, flowers, and stems (González-Minero et al., 2023). In the health industry, BB was applied to smooth muscle tissue problems related to genito-urinary apparatus including the urinary bladder, ureter, and uterus (Hayes et al., 2024). More so, it was given to patients with dysmenorrhea before discovering other preferable analgesics, antipyretics, and anti-inflammatory agents (Anuchatkidjaroen & Phaechamud, 2013). It also relieves asthma and related symptoms (Kazi et al., 2021). Currently, it is applied to the skin as a lotion for ticks and lice (Bezabh et al., 2022), as a preservative in heparin drugs (Al-Akeel et al., 2013), as well as a vehicle in testosterone preparations for treating hypogonadism (Vashishth et al., 2024). Surprisingly, the mechanism of action of BB is still unknown. Recent studies have suggested that BB helps modulate the spastic effects of smooth muscle viscera in patients thereby offering relief in acute spastic conditions (Pang, 2024). Safety assessment of BB, benzyl alcohol, benzoic acid, and its salts have been documented (Del Olmo et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017). Yet, there are divergent opinions about its safety on the reproductive system, although BB and benzyl derivatives stay relevant. This calls for further evaluation on their biological effects, in particular, given the fact that they are present mostly for clinical and non-clinical uses.

The problems of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are on the increase. The pathological and genetic bases of LUT-associated risk factors have been updated (Kheir et al., 2024; Hennenberg et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). Despite the many years of efforts of pharmacological intervention, symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) responds to α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists for flow rates of urine control but does not cater to the long-term risk of urinary retention (Gravas et al., 2023; Katsimperis et al., 2024). Also, 5α-reductase inhibitors which reduce dihydrotestosterone production can help correct volume-related symptoms and decrease the risk of acute urinary retention (Arya et al., 2025). When combined, α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists and 5α-reductase inhibitors can achieve more therapeutic goals in BPH suggestive of LUTS (Hennenberg et al., 2017). Another relevant second line of treatment is less effective and is not preferred (Michel et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024). Upon this, medications are complicated by adverse drug effects and patient intolerance and may still proceed to surgery. Importantly, there is no ideal drug for the treatment of mixed LUTS (Michel et al., 2023). These necessitate a search for a new medical intervention or an alternative therapy. To stem the tide, the European Association of Urology guidelines have for the first time supported the recommendation of medicinal plant products as supplementary for alternative management of BPH (Gravas et al., 2023).

Several herbal remedies or medicinal plant products have been explored for use in LUT suggestive of BHP (Leisegang et al., 2022; Davis & Choisy, 2024). There is growing interest in addressing the gaps between complex phytochemicals and drug discovery (Chihomvu et al., 2024). Thousands of compounds in plant extract with known ethnobotanical history are often screened for biological activity (Sharma et al., 2016; Chihomvu et al., 2024; Davis & Choisy, 2024). There is a paucity of studies on the in vitro effects of BB action on human prostate smooth muscle tissue. The present study was designed to achieve two goals. Firstly, it reports the isolation and purification of nBB from A.smeathmannii. Secondly, it assessed in vitro actions of nBB on human prostate tissue obtained from radical prostatectomy to ascertain its effect.

Methodology

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drugs and chemicals

Phenylephrine and noradrenaline were obtained from Sigma (Munich, Germany). Carbachol, methacholine, n-heptane, deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany), and potassium chloride was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO 63103, USA). Commercial benzyl benzoate (BB) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Cheme GmbH, Kappehweg 1, 91625 Schnelldorf, Germany (PCode: 102808073). Other solvents and reagents used were of analytical grade.

Plant Collection, Authentication and Extraction

A. smeathmannii roots were collected on natural farmland beside the premiere area, Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria in 2023 by the botanist, Dr. A. Samuel Odewo [Forest Research Institute of Nigeria (FRIN), Ibadan 200221, Oyo-State, Nigeria]. Plant-authenticated vouchers were deposited in a publicly available herbarium, FRIN, Nigeria (Voucher number, FHI: 113685) (Figure 1). Research permission to experiments with A. smeathmannii roots was approved by the Health Research and Ethics Committee, College of Medicine, University of Lagos (CMUL/HREC/09/18/424). In addition, the authors obtained a phytosanitary certification (No. 0124876) from the Nigeria Agricultural Quarantine Service Plant Health, Nigeria. The plant root was dried at ± 23 °C expunged from the sticks and ground into powder (Christy and Norris LAB MILL, NO. 50158, England) in the Pharmacognosy Department, Olabisi Onabanjo University Nigeria.

A solvent extractor thimble was filled with (25 g x 10) of A. smeathmannii roots powder and extracted with n-heptane (EMPLURA®) (250 mL flask) for four hours. The solvent was removed using a rotatory evaporator coupled with Vacuumbrand CVC 3000 and IKA® RV 10 digital (IKA®, RV 10D S93, Germany) at 40 ± 1 °C and 120 mbar. The dried light golden-yellow extract (27.1 g; yield, 4.96%) was reconstituted and used in fractions (stored at 4 °C) for biological activities studies in vitro.

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analyses were carried out on precoated silica gel 60 F254 and cellulose sheets (Merck, Germany), and visualization of the plates was carried out under UV (Jeulin® Enceinte, Germany, 701435, 365 nm) or stained using potassium permanganate (0.1 M). The total light golden-yellow heptane AS extract of A. smeathmannii (27.1 g) was dissolved in 90 % methanol and extracted in n-hexane (1:10) by a separating funnel into an upper layer (HUASF, 1.25 g) and a lower layer (HLASF, 15.24 g). Further, HLASF was dissolved in 70 % methanol and extracted with dichloromethane to afford a dichloromethane fraction (HLASF) (0.91 g) and a residue (11.14 g) which were stored at -40C. A preparatory chromatography using a 5:1:0.02 mixture of hexane: ethyl acetate: acetic acid, v/v was done providing 44 fractions (HLASF1-44). The HLASF1-44 fractions were monitored by TLC using a mixture of hexane: ethyl acetate: acetic acid (10:1:0.02, v/v). TLC was also conducted on the lower layer of A. smeathmannii (HLASF) fraction using a 5:1:0.02 mixture of n-hexane: ethyl acetate: acetic acid (v/v). Retention on TLC plates was measured as the retention factor (Rf). The preparatory TLC technique afforded for HLASFF12 a Rf value of 0.53 from HLASF. For preparative purposes, the HLASF fraction was separated using an 18-cm column (diameter, 5 cm) filled with 30 g of silica gel 60 (35 - 75-μm mesh, CAS No. 7631 - 89 -9, Merck KGaA, Germany). The column was sealed and topped with sea sand (3 mm, Cat. Nr. 1313710000, Grussing GmbH). The flow rate was 2.5 mL/min. Fractions HLASF1-44, 5 mL each were collected and monitored by TLC (conditions, see above). Fractions showing spots with the same Rf value were gathered in a single flask and the solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator. Repeated column chromatography of HLASF7-14 yielded twenty-two fractions (HLASFF1-22). Serial TLC, NMR, HPLC, and GC-MS were used to analyse the isolates. HLASFF12 (nBB) appeared as a colourless liquid that crystalized into a white solid (10.5 mg).

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis was performed with a QP2010 Plus gas chromatograph/mass instrument (Shimadzu®) equipped with a fused silica capillary column (Equity TM-5; 30 m, 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm film thickness; SUPELCO) and a quadrupole detector working with electron impact ionization at 70 eV. An aliquot (30 µg in 500 µl methanol) of A. smeathmannii was prepared. A fraction of 1 µl was injected in 1:5 split modes at an interface temperature (50°C for 3 min and 50°C - 310°C with 10°C/min) and a helium inlet pressure of 70 kPa. Shimadzu® (Kyoto Japan) GC-MS scan measurement was used for data collection in duplicate.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was performed with 20 mg of A. smeathmannii dissolved in 500 μL CDCl3. 1H-NMR spectra were registered at 27 °C with an Avance-III 500 MHz system (BRUKER, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped within inverse probe head (5 mm SEI, 1H/13C; Z-gradient). Two-dimensional experiments including COSY, HMBC, HSQC, and NOESY spectra were measured using standard Bruker parameter sets in the TOPSPIN 3.5 software. Data processing and analysis were done with MNova (15.0.1).

High-Performance Column Chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu® SIL-20AHT Europa GmbH, Duisburg, F.R. Germany) was carried out with HPLC instruments (SPD-10AV UV-VIS detector, LC-10AS, SIL-20A HT autosampler) using a LiChrospher® column (RP-18, 5 µm). Thus, HLASF1-44 and HLASFF12 (5 µl each) aliquots were dissolved in 1 ml methanol and placed in glass vials, after which they were filled up to near total vial volume of 1.5 ml and placed into the HPLC (Shimadzu®) sampler. The column was developed with aqueous methanol (60%) at 0.5 mL/min. The eluate was monitored at 280 nm.

This study obtained tissues from the periurethral zone of the prostate from patients who underwent radical prostatectomy (rPx) for prostate cancer. Tissues were sampled immediately after surgery, followed by macroscopic examination of tissues by the pathology department (LMU). Specifically, periurethral zone portions were taken and used since most prostate cancers arise in the peripheral zone so patients with previous transurethral resection or with previous laser enucleation were excluded. For storage and transport, organs and tissues were placed in Custodiol® (Köhler, Bensheim, Germany) solution. Most importantly, BPH is present in almost 80% of patients with prostate cancer. For the measurement of contraction, dissected prostate strips (6 × 3 × 3 mm) were mounted in 10 mL aerated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) tissue baths (Danish Myotechnology, Denmark, DMD) with four chambers, containing Krebs-Henseleit (KH) solution (37°C, pH 7.4) (Hennenberg et al., 2017). Experiments were started within 1 hour of tissue collection sampling. Mounted preparations were stretched to approximately 4.9 mN and left to equilibrate for 45 min. The initial phase of the equilibration period may be characterized by spontaneous decreases in tone; therefore, tension was adjusted three times during the equilibration period, until a stable resting tone of 4.9 mN was attained. After the equilibration period, the maximum contraction induced by 80 mM KCl was assessed. Subsequently, media were rinsed out three times with KH solution, and nBB or ethanol (for controls) was added. Cumulative concentration-response curves for noradrenaline (NA), and phenylephrine (PHE) (for prostate tissues) were constructed 30 minutes following the addition of BB or ethanol. From one patient, the sample was split into the control and nBB group (two each) examined, and analyzed as a single case within the same experiment. Different patient samples were used for agonist-induced contraction. Consequently, both groups in each series had identical group sizes. Agonist-induced contractions were expressed as a percentage of 80 mM KCl-induced contractions (maximum of phasic contraction) (Hennenberg et al., 2017). This is required because of differences in stromal/epithelial ratios, different smooth muscle content, varying degrees of BPH, and/or any other heterogeneity between tissue samples and patients. The nBB concentrations of 10 µM, 100 µM 5, and 200 µM were compared to controls examined with ethanol. Fractions of 50 µL nBB were added to a 10 mL organ bath to achieve final bath concentrations of 0.05, 0.25, and 0.5 µM nBB, respectively. The maximum possible contractions (Emax), concentrations inducing 50% of maximum agonist-induced contraction (EC50), and frequencies (f) as 50% of maximum EFS-induced contraction (Ef50) were calculated separately for each single experiment, by curve fitting using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The EC50 values have been expressed as negative logarithms of the molar concentration for agonists (pEC50) to quantify potency (Tamalunas et al., 2022). Studies on human prostate tissues were carried out in line with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and have been approved by the ethics committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians University (LMU), Munich, Germany. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The possible modulatory effects of increasing nBB concentrations on prostate tissues were assessed and compared with the control. Contractions were induced with NA (non-selective) and PHE (α1-selective) agonists for adrenoceptors (0.1 - 100 µM) in prostate tissues. Anti-contractile effects were expressed as a positive percentage in proportion to the contraction achieved by an agonist.

Electrical Field Stimulation (EFS) was applied to achieve frequency-response curves for contractions induced by neurogenic activation, following 30 min after the addition of BB or control ethanol. EFS generates action potentials that cause endogenous neurotransmitters to be released, including noradrenaline and acetylcholine. Briefly, tissue strips were placed between two parallel platinum electrodes connected to a CS4 stimulator (Danish Myotechnology). Square pulses (positive monopole) with durations of 1 millisecond and voltage of 20 V were applied for train duration. EFS-induced contractile responses were studied at frequencies of 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 Hz, with train intervals of 60 s between stimulations. Similarly, only one curve was recorded with each sample. Calculations of the EFS-induced contractions followed the measurement of peak height in EFS-induced contractions expressed as % of 80 mM KCl-induced contractions (maximum of phasic contraction). The Emax values and frequencies (f) inducing g 50% of the maximum EFS-induced contraction (Ef50) were evaluated by curve fitting using GraphPad Prism.

Results of concentration and frequency response curves are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Post hoc analyses for multiple comparisons at single agonist concentrations or frequencies among groups were compared by Two-way ANOVA multiple comparisons. Each series of organ bath experiments is based on n = 5 independent experiments, including values from paired samples in each experiment. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (9.5.0) (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Emax, pEC50, and Ef50 values were two sample means in each series in the human prostate experiments compared by a paired t-test (Michel et al. 2020). Changes in concentration and frequency response observed in contraction experiments are reported as percentage change relative to control (mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs of KCl).

3. Results

Structural analysis of HLASFF12

Fraction HLASFF12 was showed a single spot on the TLC plate at an Rf value of 0.53 (see above). Similarly, reversed phase HPLC analysis of this fraction gave a dominant peak (monitored at 280 nm) at a retention volume of 22.4 mL (Figure 5). Therefore, we decided to perform a more detailed structural analysis by GC-MS (Supplementary Figure S1) and NMR (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures S4–S6). The GC analysis of HLASFF12 again showed a single peak at a retention time of 18.92 minutes (Supplementary Figure S7). In the mass spectrum, HLASFF12 was characterized by a molecular ion M+ at m/z 212 and a base peak at m/z 105 (Supplementary Figure S2). A similarity search with data from the NIST library resulted in a 98% match with the mass spectrum of benzoic acid benzyl ester (benzyl benzoate, BB). GC-MS analysis of a commercial reference sample of BB was fully in line (Figure 4). Additionally, we subjected HLASFF12 to a detailed NMR analysis (approximately 5 mg in 0.5 mL CDCl3). The 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) was characterized by intense signals in the spectral region for aromatics (i.e. 8.2 - 7.3 ppm) (Supplementary Figures S3 and S7). Moreover, we observed a singlet peak at 5.42 ppm which was determined as a CH2 group by a two-dimensional HSQC-DEPT experiment (Supplementary Figure S5). Normalizing the integral of this signal to an arbitrary value of 2, the total integral of the signals in the aromatic region indicated the presence of 10 H-atoms, as expected for BB. Fully in line with the expected structure, NMR clearly showed the two benzyl moieties of BB connected via a CH2 group that is attached to an O-atom (Figure 2 and ). The presence of two benzyl rings was also confirmed by the observed correlation signals in the two-dimensional COSY, NOESY, HSQC and HMBC spectra (Supplementary Figure S3–S6). Again, a sample of commercial BB afforded the same 1H and 13C NMR signatures (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S1). Based on this solid spectral evidence, we assigned benzyl benzoate (BB) as the underlying structure in HLASFF12. Since the 1H NMR spectrum of HLASFF12 did not display other signals at high intensities and the TLC, GC and HPLC data only showed one signal for nBB, we concluded that HLASFF12 mainly consisted of BB (> 90 %) (Figure 3).

A non-selective agonist of the adrenergic system, noradrenaline, contracted human prostate tissues (0.1 - 100 µM NA) as shown in Figure 6. The addition of NA following incubation with nBB (10 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM) in the organ bath produced no significant change when compared with the control ethanol group (Figure 6A–I) (Table 1). When 10 µM nBB was added to the bath, NA-induced contractility on the human prostate increased (p> 0.05) up to 39% at 100 µM NA (mean difference (MD) 37.23 [-75.22 - 0.77] % of KCl). In contrast, inhibitions of NA-induced contractions of the human prostate were obtained with increasing nBB concentrations (50 and 100 µM). Thus, the addition of 50 µM produced inhibitions (p> 0.05) at 10, 30, and 100 µM NA up to 22% (MD 27.11 [-8.985 - 63.20] of % KCl), 6.2% (8.512 [-27.58 - 44.60]) and 0.1% (0.11 [-35.98 - 36.20]) when compared with control ethanol group. Furthermore, 100 µM nBB incubation produced inhibitions (p> 0.05) at 3, 10, 30 and 100 µM NA up to 11.8% (MD 6.19 [-62.22 - 74.60]), 29.6% (32.07 [-36.34 - 100.50 µM]), 22.1% (26.39 [-42.02 - 94.80]) and 34.6% (39.04 [-29.37 - 107.5]).

The contraction of human prostate tissues was achieved by phenylephrine, an α1-adrenoceptor agonist (0.1- 100 µM NA) in (Figure 7A–I) (Table 1). An addition of PHE following incubation of human prostrate with nBB (10 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM) in the organ bath did not lower contractions due to NA compared with the control ethanol group. Thus, the lowest nBB dose (10 µM) lowered (p> 0.05) peak by 5% at 100 µM NA concentrations (MD 6.7 [-43.65 - 57.12] % of KCl). Also, slight but insignificant inhibitions of NA-induced contractions were observed with increasing BB (p > 0.05) concentration of 50 µM nBB, which peak at 30 µM NA up to 9.2% (MD 29.97 [-53.58 - 113.5] of % KCl) and decrease (p > 0.05) further at 100 µM to 2% (12.31 [-71.24 - 95.86] of % KCl) when compared with the control ethanol group. However, with 100 µM nBB, no reduction in NA-induced contraction was observed at 100 µM NA 1.6% (MD 1.75 [-26.77 - 30.27] of KCl).

The release of endogenous neurotransmitters neurogenic potentials by EFS leading to contraction was investigated in human prostate tissues (Figure 8A–I) (Table 2). The nBB addition produced no inhibition during EFS-induced contractions induced by 2 - 32 Hz in human prostate tissues. All the frequencies applied (2 - 32 Hz) at 10 µM nBB did not produce any change but further increased contractions of human prostate tissues when compared with control. However, with 50 µM nBB, reduced (p> 0.05) the EFS-induced human prostate contraction within the curve, peak up to 57% at 2 Hz (MD 10.51 µM [-15.58 to 36.61] of KCl), 4 Hz (27.4%) (6.8 [-19.32 to 32.87]), 8 Hz (17%) (12.68 [-13.44 to 38.75]), 16 Hz (26.8%) (23.7 (-2.351 to 49.84] of KCl, p = 0.08) and 32 Hz (22%) (41.31 [15.22 to 67.41] of KCl, p = 0.01). With 100 µM nBB, inhibitions (p> 0.05) peak at 16 Hz (16%) (9.04 [-36.45 to 54.53] and 32 Hz (23.8%) (19.52 [-25.97 to 65.01] of KCl) when compared with the control groups.

Discussion

This present study provides a report of HLASFF12 isolated from A. smeathmannii roots and further explores its potential modulatory effects on human prostate smooth muscle tissue in the organ bath. The A. smeathmannii root extract has been used for a long in Western Africa and has become a constituent of many polyherbal mixtures (Catarino et al., 2016). Previous studies showed that A. smeathmannii was effective in enhancing reproductive function, hematological indices and possess minimal toxicities in rodents (Kale et al., 2019a; 2019b). In pursuit of its phytoactive components, repeated column chromatography led to the fraction HLASFF12 which was identified by GC-MS, HPLC, and NMR (1D and 2D) as benzyl benzoate. Thus, HLASFF12 constitutes one of the main compounds in A. smeathmannii root extracts (Kale et al. 2019).

The pharmacological potential of nBB incubated in the organ bath and exposed to human prostate smooth muscle tissue stimulated by adrenergic agonist was investigated. BB, an ester soluble in many organic compounds such as alcohol, but less in water is a well-known cosmetic ingredient and pesticide (Johnson et al., 2017; Chen & Oi, 2020). Now, BB is being chemically synthesized from the condensation of benzoic acid and benzyl alcohol among others (De Meneses et al., 2020). BB is easily metabolized and has a multipurpose use (Johnson et al., 2017). There are reports that benzyl radicals exhibit smooth muscle relaxing actions with minimal toxicity (Semwal et al., 2021). Several medicinal plants are being explored for natural BB and other benzyl derivatives in search of novel compounds (Rivero-Cruz et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2023). The uses, exposure, and controversy of benzoic acid and its derivatives in several foods and additives have been reviewed (Del Olmo et al., 20217; Yin et al., 2018). In this study, the isolation and purification of the HLASF fractions were studied extensively through repeated TLC, NMR, GC-MS and HPLC. GC-MS of one of the obtained fractions (HLASFF12) showed a match with the mass spectrum for a benzoic acid benzyl ester (BB) with a molecular ion M+ at m/z 212 (98%) (Figure 4) (Supplementary Figure S4). Further, structural characterization was established using detailed NMR spectroscopy (Figure 3). All analytical data were in line with a reference sample of commercial BB. From our knowledge, this study is the first to isolate and purify BB from A. smeathmannii. The contractility of the human prostate by adrenergic agonists (NA or PHE, 0.1 - 100 µM) was shown. From our results, the adrenergic non-selective agonist, NA, induces contraction of human prostate tissues was not affected by 10 µM nBB following incubation in the organ bath (Figure 6) (Table 1). However, a slight but insignificant inhibition of NA-induced was achieved by increasing the concentrations of nBB (50 and 100 µM). Similarly, when PHE, a specific agonist at α1-adrenoceptor was applied, contractility of human prostate tissue persisted with nBB (10 µM), although 50 and 100 µM nBB slightly but insignificantly lowered prostate contractility.

It is interesting that BB as a solvent or preservative in medicals or cosmetics could impact health and environment and thus requires monitoring. Both males and females are patients of LUTS which is on the increase (Amundsen et al., 2020; González-Minero et al., 2023). Symptomatic LUTS is common in men particularly because of the prostate enlargement secondary to benign prostate hypertrophy (BPH) (Amundsen et al., 2020; Cavanaughet al., 2024). Mostly men in their fifties and above are being affected by BPH which may their overall health (Zhang et al., 2024). Given the pathophysiology of BPH, increased prostate smooth muscle tone is a risk factor for urethral obstruction, causing impairments that precipitate LUTS symptoms (Cavanaugh et al., 2024).

Our present findings show that persistent firing waves discharged from the prostate and the increased tone by low dose nBB may increase further the prostatic urethral pressure which could worsen patient symptoms. Our results support the inhibitory effects of increasing nBB dosage to attain reduced contraction (Al-Akeel et al., 2013; Kazi et 2021). Studies have also suggested that BB could modulate pain to regulate the spastic action of smooth muscle before bringing about relief (Rivero-Cruz et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2016; Orra et al. 2021). In parallel, the effect of nBB on EFS-induced contraction of human prostate tissues was assessed. The results obtained in our study demonstrate that the release of endogenous neurotransmitters neurogenic potentials following EFS were like those observed with adrenergic agonists. While, 10 µM nBB did not produce a positive change to EFS-induced neurogenic firing, 50 and 100 µM nBB slightly reduced the overall frequency (2 - 32 Hz). Thus, incubation of nBB in the bath produced no inhibition to the human prostate contractility, but offered some degree of inhibition, giving further credence to anti-spasmolytic activity (Rivero-Cruz et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2023).

The molecular mechanism of BB in inhibiting prostate smooth muscle has not been studied, but these findings may be pointing to the mechanism of vasodilation earlier reported (Rivero-Cruz et al., 2007; Kazi et al., 2021; Orra et al., 2021). Though the mechanisms of BB inhibitory effects are poorly studied, its anti-pesticidal action has been associated with depolarization of the nervous system. Additionally, it may be that nBB works together with a1-adrenergic to promote prostate stimulation. Studies have suggested that non-adrenergic contractions efforts including those of endothelins contribute to these efforts (Hennenberg et al., 2024). It may also be that nBB inhibitory action favors non-selective adrenergic inhibition and possibly other neurotransmitter-release given low doses. However, the difference between nBB treated and control ethanol group was large enough to reduce the abnormal prostate electrical field stimulation at high dosage. Whether this would translate into clinical implication requires further investigation.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates for the first-time isolation and purification of nBB from A. smeathmannii which exhibits potential modulatory inhibitory effects on adrenergic agonists and electrical force stimulation on human prostate smooth tissue. This is in support of its ethnobotanical usage of the crude extracts in the management of reproductive diseases. Also, since nBB modulates prostate smooth muscle contractility, caution in patients taking herbal supplements or pharmaceutical formulations containing BB is essential as this may play a role in lower urinary tract symptoms condition.

Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O. E. K, W. E., M. H.; Methodology, O. E. K, C. H., A. T., W. E., M. H.; Software, O. E. K, C. H., W. E., M. H. Validation, O. E. K, I. R., C. H., A. T., C. G. S., W. E., M. H.; Formal analysis, O. E. K, C. H., W. E., M. H.; Investigation, O. E. K, I. R., C. H., W. E., M. H.; Resources, O. E. K, I. R., C. H., A. T., C. G. S., W. E., M. H.; Data curation, O. E. K, I. R., C. H., A. T., C. G. S., W. E., M. H.; Writing - Original draft preparation - O. E. K, C. H., W. E., M. H.; Writing—review and editing O. E. K, I. R., C. H., A. T., C. G. S., W. E., M. H.; Visualization, O. E. K, I. R., C. H., A. T., C. G. S., W. E., M. H.; Supervision, O. E. K, C. H., A. T., C. G. S., W. E., M. H.; Project administration, O. E. K, I. R., C. H., W. E., M. H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out with the Fellowship support of the Alexander Von Humboldt Stiftung Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Dr. Odewo A. Samuel of the Herbarium Unit, Forest Research Institute of Nigeria (FRIN), Oyo, Nigeria, is gratefully acknowledged. We also acknowledge the technical assistance Mr. Adeoti O. A., Pharmacognosy Department, Olabisi Onabanjo University Nigeria. The 2023 Award Fellowship support of the Alexander Von Humboldt Stiftung Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation

A. smeathmannii (Acridocarpus smeathmannii) (AS)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)

Benzyl benzoate (BB)

Concentrations inducing 50% of maximum agonist-induced contraction (EC50)

Electrical Field Stimulation (EFS)

Frequencies (f) inducing 50% of maximum EFS-induced contraction (Ef50)

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS),

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Lower layer of A. smeathmannii (HLASF)

Lower layer of A. smeathmannii fraction (HLASFF12) (nBB)

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)

Maximum possible contractions (Emax),

Negative logarithms of the molar concentration for agonists (pEC50)

Noradrenaline (NA),

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

Phenylephrine (PHE)

Radical prostatectomy (rPx)

Retention factor (Rf)

Thin layer chromatography (TLC)

Homonuclear correlation spectroscopy (COSY)

Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy (NOESY)

Heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC)

Distortionless Enhancement by Polarization Transfer (DEPT)

Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (HMBC)

References

- Al-Akeel, R. A.; El-Kersh, T. A.; Al-Sheikh, Y. A.; Al-Ahmadey, Z. Z. Heparin-benzyl alcohol enhancement of biofilms formation and antifungal susceptibility of vaginal Candida species isolated from pregnant and nonpregnant Saudi women. Bioinformation 2013, 9(7), 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, C. L.; Helmuth, M. E.; Smith, A. R.; DeLancey, J. O.; Bradley, C. S.; Flynn, K. E.; LURN Study Group. Longitudinal changes in symptom-based female and male LUTS clusters. Neurourology and urodynamics 2020, 39(1), 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anuchatkidjaroen, S.; Phaechamud, T. Virgin coconut oil containing injectable vehicles for ibuprofen sustainable release. Key Engineering Materials 2013, 545, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, G. C.; Rathee, A.; Mehla, S.; Bisht, P.; Sharma, R. A Review of the Azasteroid-type 5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors for the Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Letters in Drug Design & Discovery 2024, 21(12), 2271–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Bezabh, S. A.; Tesfaye, W.; Christenson, J. K.; Carson, C. F.; Thomas, J. Antiparasitic activity of tea tree oil (TTO) and its components against medically important ectoparasites: A systematic review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14(8), 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, L; Havik, PJ; Romeiras, MM. Medicinal plants of Guinea-Bissau: Therapeutic applications, ethnic diversity and knowledge transfer. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2016, 183, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh, D.; Urbanucci, A.; Mohamed, N. E.; Tewari, A. K.; Figueiro, M.; Kyprianou, N. Link between circadian rhythm and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)/lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The Prostate 2024, 84(5), 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Oi, D. H. Naturally occurring compounds/materials as alternatives to synthetic chemical insecticides for use in fire ant management. Insects 2020, 11(11), 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihomvu, P.; Ganesan, A.; Gibbons, S.; Woollard, K.; Hayes, M. A. Phytochemicals in Drug Discovery—A Confluence of Tradition and Innovation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(16), 8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Santos, J. V.; Guesdon, I. R.; Amorim, A. M. A.; Meira, R. M. A. S. Does leaf morphoanatomy corroborate systematics and biogeographic events in the Paleotropical genus Acridocarpus (Malpighiaceae)? South African Journal of Botany 2023, 163, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. C.; Choisy, P. Medicinal plants meet modern biodiversity science. Current Biology 2024, 34(4), R158–R173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, R. F.; de Morais, I. L.; Alves-Silva, T.; Antonio-Domingues, H.; Pellegrini, M. O. A new classification system and taxonomic synopsis for Malpighiaceae (Malpighiales, Rosids) based on molecular phylogenetics, morphology, palynology, and chemistry. PhytoKeys 2024, 242, 69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Meneses, A. C.; Balen, M.; de Andrade Jasper, E.; Korte, I.; de Araújo, P. H. H.; Sayer, C.; de Oliveira, D. Enzymatic synthesis of benzyl benzoate using different acyl donors: Comparison of solvent-free reaction techniques. Process Biochemistry 2020, 92, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Del Olmo, A.; Calzada, J.; Nuñez, M. Benzoic acid and its derivatives as naturally occurring compounds in foods and as additives: Uses, exposure, and controversy. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2017, 57(14), 3084–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Olmo, A.; Calzada, J.; Nuñez, M. Benzoic acid and its derivatives as naturally occurring compounds in foods and as additives: Uses, exposure, and controversy. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2017, 57(14), 3084–3103. [Google Scholar]

- González-Minero, F. J.; Bravo-Díaz, L.; Moreno-Toral, E. Pharmacy and fragrances: Traditional and current use of plants and their extracts. Cosmetics 2023, 10(6), 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravas, S; Gacci, M; Gratzke, C; Herrmann, TR; Karavitakis, M; Kyriazis, I; Malde, S; Mamoulakis, C; Rieken, M; Sakalis, VI; Schouten, N. Summary paper on the 2023 European Association of Urology guidelines on the management of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms. European urology 2023, 84(2), 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B. W.; Choi, H. W.; Rathore, A. P.; Bao, C.; Shi, J.; Huh, Y.; Abraham, S. N. Recurrent infections drive persistent bladder dysfunction and pain via sensory nerve sprouting and mast cell activity. Science immunology 2024, 9(93), eadi5578. [Google Scholar]

- Hennenberg, M.; Acevedo, A.; Wiemer, N.; Kan, A.; Tamalunas, A.; Wang, Y.; Gratzke, C. Non-adrenergic, tamsulosin-insensitive smooth muscle contraction is sufficient to replace α1-adrenergic tension in the human prostate. The Prostate 2017, 77(7), 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennenberg, M.; Hu, S.; Tamalunas, A.; Stief, C. G. Genetic Predisposition to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Where Do We Stand? European Urology Open Science 2024, 70, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.; Bergfeld, W. F.; Belsito, D. V.; Hill, R. A.; Klaassen, C. D.; Liebler, D. C.; Andersen, F. A. Safety assessment of benzyl alcohol, benzoic acid and its salts, and benzyl benzoate. International journal of toxicology 2017, 36(3_suppl), 5S–30S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, O. E.; Awodele, O.; Akindele, A. J. Acridocarpus smeathmannii (DC.) Guill. & Perr. Root enhanced reproductive behavior and sexual function in male wistar rats: Biochemical and pharmacological mechanisms. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2019a, 230, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kale, O. E.; Awodele, O.; Akindele, A. J. Subacute and subchronic oral toxicity assessments of Acridocarpus smeathmannii (DC.) Guill. & Perr. root in Wistar rats. Toxicology Reports 2019b, 6, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Katsimperis, S.; Kapriniotis, K.; Manolitsis, I.; Bellos, T.; Angelopoulos, P.; Juliebø-Jones, P.; Tzelves, L. Early investigational agents for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia’. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2024, 33(4), 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A. A.; Reddy, B. S.; Singh, L. R. Synthetic approaches to FDA approved drugs for asthma and COPD from 1969 to 2020. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 2021, 41, 116212. [Google Scholar]

- Kheir, G. B.; Verbakel, I.; Wyndaele, M.; Monaghan, T. F.; Sinha, S.; Larsen, T. H.; Everaert, K. Lifelong LUTS: Understanding the bladder's role and implications across transition phases, a comprehensive review. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2024, 43(5), 1066–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Leisegang, K.; Jimenez, M.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Finelli, R.; Majzoub, A.; Henkel, R.; Agarwal, A. A systematic review of herbal medicine in the clinical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2(1), 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M. C.; Cardozo, L.; Chermansky, C. J.; Cruz, F.; Igawa, Y.; Lee, K. S.; Andersson, K. E. Current and emerging pharmacological targets and treatments of urinary incontinence and related disorders. Pharmacological Reviews 2023, 75(4), 554–674. [Google Scholar]

- Orra, S.; Boyajian, M. K.; Bryant, J. R.; Talbet, J. H.; Mulliken, J. B.; Rogers, G. F.; Oh, A. K. Balsam of Peru: history and utility in plastic surgery. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2021, 32, 1209–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, D. S. (2024). Anesthetic and analgesic adjunctive drugs. Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Sixth Edition of Lumb and Jones, 420-447.

- Rivero-Cruz, B.; Rivero-Cruz, I.; Rodríguez-Sotres, R.; Mata, R. Effect of natural and synthetic benzyl benzoates on calmodulin. Phytochemistry 2007, 68(8), 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semwal, R. B.; Semwal, D. K.; Combrinck, S.; Viljoen, A. Emodin-A natural anthraquinone derivative with diverse pharmacological activities. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112854. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, C.; M. Al Kaabi, J.; M. Nurulain, S.; N. Goyal, S.; Amjad Kamal, M.; Ojha, S. Polypharmacological properties and therapeutic potential of β-caryophyllene: a dietary phytocannabinoid of pharmaceutical promise. Current pharmaceutical design 2016, 22(21), 3237–3264. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M. K.; Savita, K.; Singh, S.; Mishra, D.; Rani, P.; Chanda, D.; Verma, R. S. Vasorelaxant property of 2-phenyl ethyl alcohol isolated from the spent floral distillate of damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) and its possible mechanism. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2023, 313, 116603. [Google Scholar]

- Soszka, N.; Hachuła, B.; Tarnacka, M.; Kamińska, E.; Grelska, J.; Jurkiewicz, K.; Kamiński, K. The impact of the length of alkyl chain on the behavior of benzyl alcohol homologues–the interplay between dispersive and hydrogen bond interactions. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2021, 23(41), 23796–23807. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, L. S.; Oliveira, D. M. T. Seed development in Malpighiaceae species with an emphasis on the relationships between nutritive tissues. Comptes Rendus. Biologies 2014, 337(1), 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Vashishth, R.; Chuong, M. C.; Duarte, J. C.; Gharat, Y.; Kerr, S. G. Two Sustained Release Membranes Used in Formulating Low Strength Testosterone Reservoir Transdermal Patches. Current Drug Delivery 2024, 21(3), 438–450. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, W.; Kim, H. T.; Wang, S.; Gunawan, F.; Wang, L.; Kishimoto, K.; Stainier, D. Y. The potassium channel KCNJ13 is essential for smooth muscle cytoskeletal organization during mouse tracheal tubulogenesis. Nature communications 2018, 9(1), 2815. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Ding, Z.; Peng, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Ke, H.; Xu, K. LUTS/BPH increases the risk of depressive symptoms among elderly adults: A 5-year longitudinal evidence from CHARLS. Journal of Affective Disorders 2024, 367, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).