Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the colorectum, posing a significant global health burden. Recent studies highlight the critical role of gut microbiota and its metabolites, particularly bile acids (BAs), in UC’s pathogenesis. The relationship between BAs and gut microbiota is bidirectional: microbiota influence BA composition, while BAs regulate microbiota diversity and activity through receptors like Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5). Targeting bile acid metabolism to reshape gut microbiota presents a promising therapeutic strategy for UC. This review examines the classification and synthesis of BAs, their interactions with gut microbiota, and the potential of nutritional and microbial interventions. By focusing on these therapies, we aim to offer innovative approaches for effective UC management.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

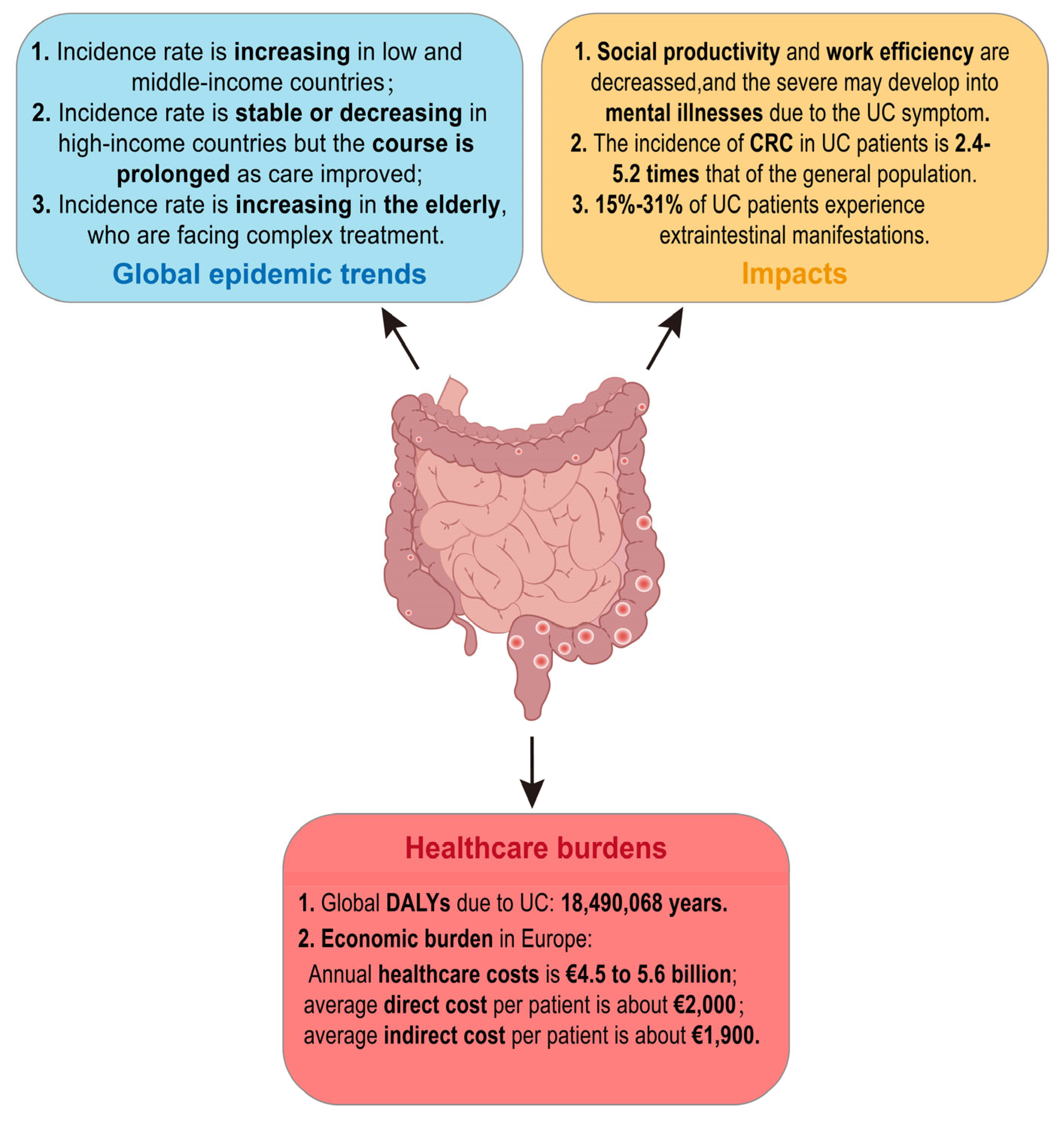

2. The Current Status of UC

3. Bile Acid Metabolism

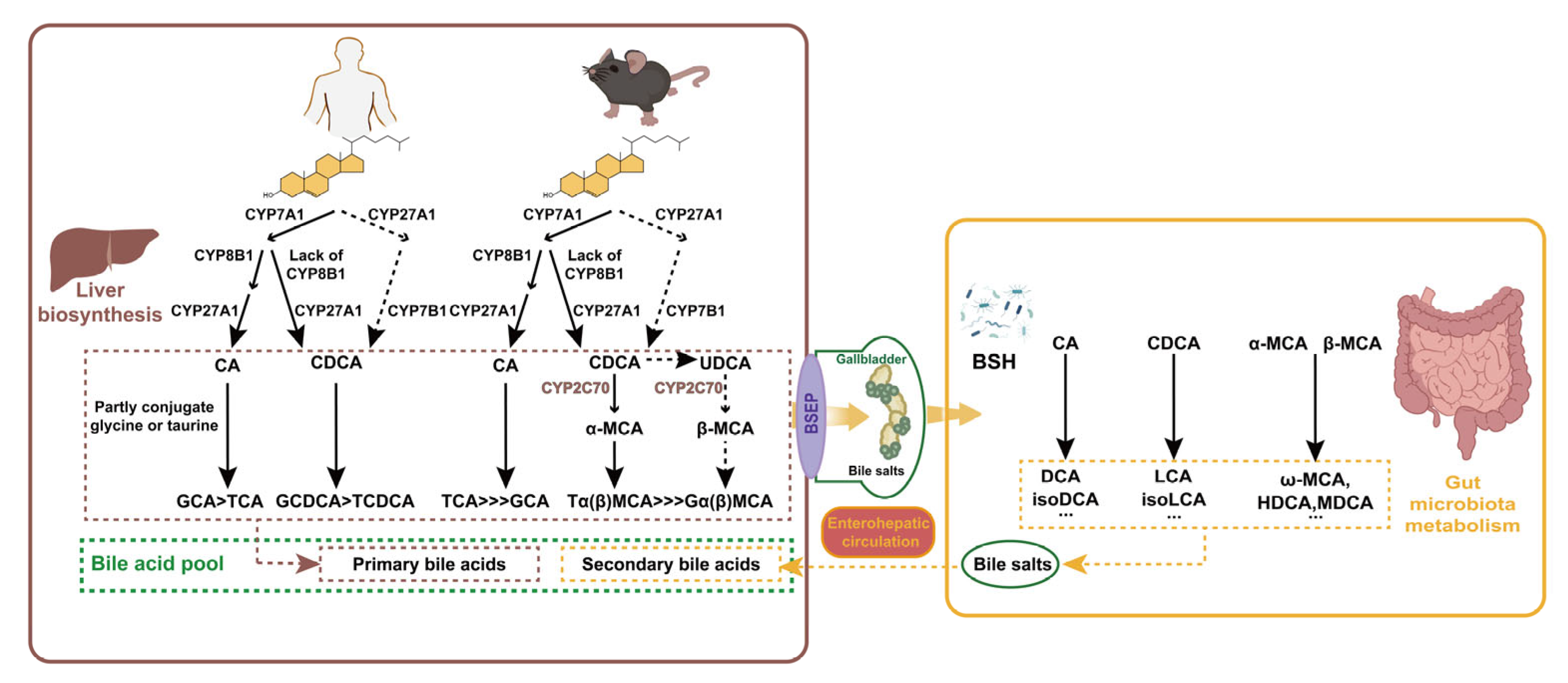

3.1. Classification and Synthesis of BAs

3.2. Mutual Regulation of Microbiota and BAs

3.3. Receptors Involved in BA Metabolism

3.3.1. FXR

3.3.2. VDR, PXR and CAR

3.3.3. TGR5

3.3.4. M3R and S1PR2

4. UC and BA Metabolism

4.1. Disrupted BA Metabolism and Intestinal Flora Drive UC

4.2. Regulation of UC by BA Receptors

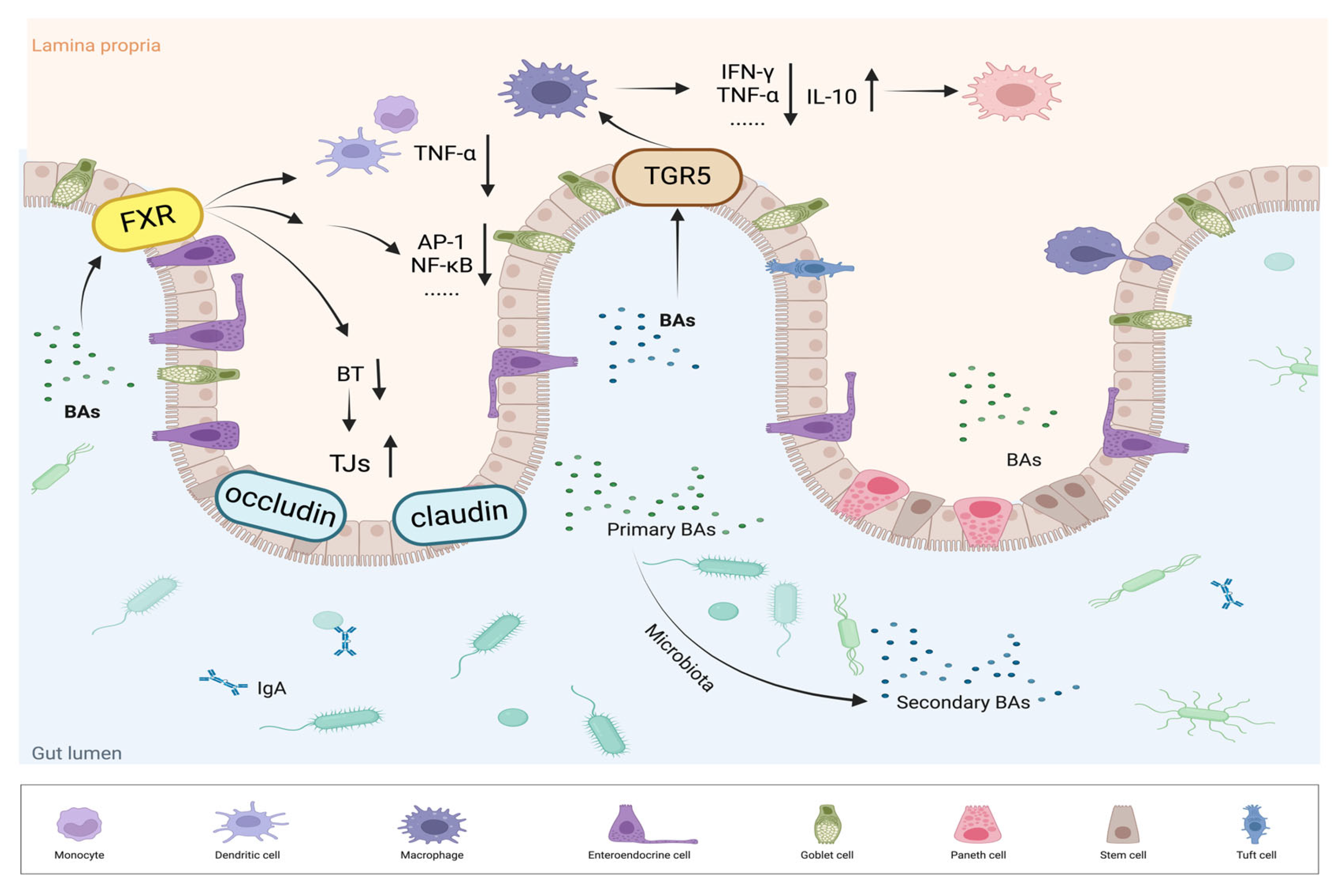

4.2.1. FXR Regulates the Immune Response and Intestinal Health

| Study design | Reference | Main findings |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse colon and enterocyte-like cells treated with medium or INT-747. | Gadaleta et al.,2011[78] | FXR activation inhibits the secretion of TNF-α in immune cells (such as PBMCs and CD14+ monocytes). |

| Fxr-/- and WT mice treated with GW4064 or vehicle for 2 days and then subjected to BDL or sham operation. | Inagaki et al.,2006[83] | FXR activation increases genes involved in enterοprotection, decreases bacterial overgrowth and mucosal injury in ileum. |

| Rats subjected to BDL or not, and treated with vehicle 5 mg/kg GW4064 or UDCA. | Verbeke et al.,2015[84] | FXR activation normalizes ileal permeability and reduces bacterial translocation, resulting in a significant decrease in natural killer cells and INF-γ expression. |

| Patients with BAD (n=28) received oral INT-747 acid 25 mg daily for 2 weeks. | Walters et al.,2015[86] | FXR activation induced by INT-747 reduces hepatic bile acid synthesis and improving diarrhea symptoms. |

| IHC was used to detect FXR in tissues from human normal samples (n = 238), polyps (n = 32), and adenocarcinomas staged I-IV (n = 43, 39, 68, and 9, respectively). | Bailey et al.,2014[88] | FXR expression decreases in samples from patients with precancerous lesions and is nearly absent in advanced colon adenocarcinoma samples. |

| Fxr-/- and WT mice intraperitoneally injected with sterile saline with or without AOM once a week for 6 weeks. | Maran et al.,2009[89] | FXR deficiency promotes cell proliferation, inflammation, and tumorigenesis in the intestine, suggesting that FXR may protect against intestinal carcinogenesis. |

4.2.2. TGR5 Bridges Inflammation and Immune Responses

5. BA-Based Therapies

5.1. Dietary and Phytochemical Strategies

5.2. Fecal Microbial Transplantation (FMT) and Probiotic Measurements

6. Summary and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| BAs | Bile acids |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| TGR5 | Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life years |

| SCFAs | Short chain fatty acids |

| CA | Cholic acid |

| CDCA | Chenodeoxycholic acid |

| DCA | Deoxycholic acid |

| LCA | Lithocholic acid |

| UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic acid |

| α/β-MCA | α/β-muricholic acid |

| HCA | Hyocholic acid |

| HDCA | Hyodeoxycholic acid |

| MDCA | Murine deoxycholic acid |

| BSEP | Bile salt export pump |

| BSH | Bile salt hydrolase |

| 7α-HSDH | 7α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase |

| OATPs | Organic Anion Transport Proteins |

| ASBT | Apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter |

| HSDHs | Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

| PXR | Pregnane X receptor |

| CAR | Constitutive androstane receptor |

| GPCRs | G protein-coupled receptors |

| M3R | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3 |

| S1PR2 | Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 |

| SHP | Small heterodimer partner |

| LRH-1 | Liver receptor homolog-1 |

| FGF15/19 | Fibroblast growth factor 15/19 |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| BAAT | Bile acid coenzyme A: amino acid N-acyltransferase |

| MRP3 | Multidrug resistance protein 3 |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| AOM | Azoxymethane |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| AP-1 | Activator protein 1 |

| STAT3 | Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 |

| BAD | Bile acid-induced diarrhea. |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor protein 3 |

References

- Le Berre, C.; Honap, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2023, 402, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.C.; Sollano, J.; Hui, Y.T.; Yu, W.; Santos Estrella, P.V.; Llamado, L.J.Q.; Koram, N. Epidemiology, burden of disease, and unmet needs in the treatment of ulcerative colitis in Asia. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 15, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Ha, C. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2020, 49, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molodecky, N.A.; Soon, I.S.; Rabi, D.M.; Ghali, W.A.; Ferris, M.; Chernoff, G.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Barkema, H.W. , et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, S.F.; van den Heuvel, T.R.; Zeegers, M.P.; Hameeteman, W.H.; Romberg-Camps, M.J.; Oostenbrug, L.E.; Masclee, A.A.; Jonkers, D.M.; Pierik, M.J. Epidemiology and Long-term Outcome of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosed at Elderly Age-An Increasing Distinct Entity? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Bernstein, C.N.; Bitton, A.; Murthy, S.K.; Nguyen, G.C.; Lee, K.; Cooke-Lauder, J.; Siddiq, S.; Windsor, J.W.; Carroll, M.W. , et al. The Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada 2018: A Scientific Report from the Canadian Gastro-Intestinal Epidemiology Consortium to Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2019, 2, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Sensky, T.; Casellas, F.; Rioux, L.C.; Ahmad, T.; Marquez, J.R.; Vanasek, T.; Gubonina, I.; Sezgin, O.; Ardizzone, S. , et al. A Global, Prospective, Observational Study Measuring Disease Burden and Suffering in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Using the Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self-Measure Tool. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 15, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, C.D.; Pavlidis, P.; Norton, C.; Norton, S.; Pariante, C.; Hayee, B.; Powell, N. Depressive symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease: an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammation? Clin Exp Immunol 2019, 197, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Andrews, J.M. It is high time to examine the psyche while treating IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Gonczi, L.; Lakatos, P.L.; Burisch, J. The Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Europe in 2020. J. Crohns Colitis 2021, 15, 1573–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabila, S.L.; McQuistan, A.A.; Murray, J.H. Incidence of Colorectal Cancer Among Active Component Service Members, 2010-2022. MSMR 2023, 30, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Marabotto, E.; Kayali, S.; Buccilli, S.; Levo, F.; Bodini, G.; Giannini, E.G.; Savarino, V.; Savarino, E.V. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Epidemiology and Prevention: A Review. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olen, O.; Erichsen, R.; Sachs, M.C.; Pedersen, L.; Halfvarson, J.; Askling, J.; Ekbom, A.; Sorensen, H.T.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbord, M.; Annese, V.; Vavricka, S.R.; Allez, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Boberg, K.M.; Burisch, J.; De Vos, M.; De Vries, A.M.; Dick, A.D. , et al. The First European Evidence-based Consensus on Extra-intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disease, G.B.D.; Injury, I.; Prevalence, C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burisch, J.; Jess, T.; Martinato, M.; Lakatos, P.L.; EpiCom, E. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, A.; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, F.; de Boer, J.F.; Staels, B. Microbiome Modulation of the Host Adaptive Immunity through Bile Acid Modification. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.R.; Haileselassie, Y.; Nguyen, L.P.; Tropini, C.; Wang, M.; Becker, L.S.; Sim, D.; Jarr, K.; Spear, E.T.; Singh, G. , et al. Dysbiosis-Induced Secondary Bile Acid Deficiency Promotes Intestinal Inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Sun, X.; Oh, S.F.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Geva-Zatorsky, N.; Jupp, R.; Mathis, D.; Benoist, C. , et al. Microbial bile acid metabolites modulate gut RORgamma(+) regulatory T cell homeostasis. Nature 2020, 577, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dawson, P.A. Animal models to study bile acid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2019, 1865, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Fukami, T.; Masuo, Y.; Brocker, C.N.; Xie, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Wolf, C.R.; Henderson, C.J.; Gonzalez, F.J. Cyp2c70 is responsible for the species difference in bile acid metabolism between mice and humans. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, S.I.; Wahlstrom, A.; Felin, J.; Jantti, S.; Marschall, H.U.; Bamberg, K.; Angelin, B.; Hyotylainen, T.; Oresic, M.; Backhed, F. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Bile acid metabolism and circadian rhythms. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2020, 319, G549–G563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyssen, H.J.; De Pauw, G.; Van Eldere, J. Formation of hyodeoxycholic acid from muricholic acid and hyocholic acid by an unidentified gram-positive rod termed HDCA-1 isolated from rat intestinal microflora. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999, 65, 3158–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Miyazaki, T.; Iwamoto, J.; Hirayama, T.; Morishita, Y.; Monma, T.; Ueda, H.; Mizuno, S.; Sugiyama, F.; Takahashi, S. , et al. Regulation of bile acid metabolism in mouse models with hydrophobic bile acid composition. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Deng, Z.; Yang, C.; Tan, J.; Dou, C.; Luo, F.; Chen, Y. Bile acid metabolism regulatory network orchestrates bone homeostasis. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 196, 106943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.V.; Begley, M.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G.; Marchesi, J.R. Functional and comparative metagenomic analysis of bile salt hydrolase activity in the human gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 13580–13585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlstrom, A.; Sayin, S.I.; Marschall, H.U.; Backhed, F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Stine, J.G.; Bisanz, J.E.; Okafor, C.D.; Patterson, A.D. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Best, N.; Rolle-Kampczyk, U.; Schaap, F.G.; Basic, M.; Olde Damink, S.W.M.; Bleich, A.; Savelkoul, P.H.M.; von Bergen, M.; Penders, J.; Hornef, M.W. Bile acids drive the newborn’s gut microbiota maturation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tang, R.; Leung, P.S.C.; Gershwin, M.E.; Ma, X. Bile acids and intestinal microbiota in autoimmune cholestatic liver diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2017, 16, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Patterson, A.M.; Cotter, P.D.; Beraza, N. Cholestasis induced by bile duct ligation promotes changes in the intestinal microbiome in mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Gui, W.; Koo, I.; Smith, P.B.; Allman, E.L.; Nichols, R.G.; Rimal, B.; Cai, J.; Liu, Q.; Patterson, A.D. The microbiome modulating activity of bile acids. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibaut, M.M.; Bindels, L.B. Crosstalk between bile acid-activated receptors and microbiome in entero-hepatic inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ticho, A.L.; Malhotra, P.; Dudeja, P.K.; Gill, R.K.; Alrefai, W.A. Bile Acid Receptors and Gastrointestinal Functions. Liver Res 2019, 3, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinal, C.J.; Tohkin, M.; Miyata, M.; Ward, J.M.; Lambert, G.; Gonzalez, F.J. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 2000, 102, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Hollister, K.; Sowers, L.C.; Forman, B.M. Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol. Cell 1999, 3, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Thorell, A.; Claudel, T.; Jha, P.; Koefeler, H.; Lackner, C.; Hoesel, B.; Fauler, G.; Stojakovic, T.; Einarsson, C. , et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid exerts farnesoid X receptor-antagonistic effects on bile acid and lipid metabolism in morbid obesity. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, P.; Cariou, B.; Lien, F.; Kuipers, F.; Staels, B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 147–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, J.S.; Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M. Hepatic FXR: key regulator of whole-body energy metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2011, 22, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, B.; Jones, S.A.; Price, R.R.; Watson, M.A.; McKee, D.D.; Moore, L.B.; Galardi, C.; Wilson, J.G.; Lewis, M.C.; Roth, M.E. , et al. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.T.; Makishima, M.; Repa, J.J.; Schoonjans, K.; Kerr, T.A.; Auwerx, J.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Molecular basis for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis by nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Ahn, S.H.; Inagaki, T.; Choi, M.; Ito, S.; Guo, G.L.; Kliewer, S.A.; Gonzalez, F.J. Differential regulation of bile acid homeostasis by the farnesoid X receptor in liver and intestine. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 2664–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, B.; Wang, L.; Chiang, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Klaassen, C.D.; Guo, G.L. Mechanism of tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor in suppressing the expression of genes in bile-acid synthesis in mice. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, F.; Guo, G.L. Tissue-specific function of farnesoid X receptor in liver and intestine. Pharmacol. Res. 2011, 63, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, T.; Choi, M.; Moschetta, A.; Peng, L.; Cummins, C.L.; McDonald, J.G.; Luo, G.; Jones, S.A.; Goodwin, B.; Richardson, J.A. , et al. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005, 2, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, M.J.; Kliewer, S.A.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Endocrine fibroblast growth factors 15/19 and 21: from feast to famine. Genes Dev 2012, 26, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pircher, P.C.; Kitto, J.L.; Petrowski, M.L.; Tangirala, R.K.; Bischoff, E.D.; Schulman, I.G.; Westin, S.K. Farnesoid X receptor regulates bile acid-amino acid conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27703–27711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, C.A.; Liddle, C.; Coulter, S.A.; Sonoda, J.; Alvarez, J.G.; Moore, D.D.; Evans, R.M.; Downes, M. Nuclear receptors constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor ameliorate cholestatic liver injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 2063–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.P.; Sonoda, J.; Xu, L.; Toma, D.; Uppal, H.; Mu, Y.; Ren, S.; Moore, D.D.; Evans, R.M.; Xie, W. A novel constitutive androstane receptor-mediated and CYP3A-independent pathway of bile acid detoxification. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 65, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, M.; Lu, T.T.; Xie, W.; Whitfield, G.K.; Domoto, H.; Evans, R.M.; Haussler, M.R.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Vitamin D receptor as an intestinal bile acid sensor. Science 2002, 296, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, R.; Shulman, A.I.; Yamamoto, K.; Shimomura, I.; Yamada, S.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Makishima, M. Structural determinants for vitamin D receptor response to endocrine and xenobiotic signals. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004, 18, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Li, T.; Ellis, E.; Strom, S.; Chiang, J.Y. A novel bile acid-activated vitamin D receptor signaling in human hepatocytes. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, F.; Liu, S.; Glaeser, H.; Dawson, P.A.; Hofmann, A.F.; Kim, R.B.; Shneider, B.L.; Pang, K.S. Transactivation of rat apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter and increased bile acid transport by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 via the vitamin D receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, F.G.; Trauner, M.; Jansen, P.L. Bile acid receptors as targets for drug development. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Chiang, J.Y. Nuclear receptors in bile acid metabolism. Drug Metab. Rev. 2013, 45, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistuba, W.; Gnewuch, C.; Liebisch, G.; Schmitz, G.; Langmann, T. Lithocholic acid induction of the FGF19 promoter in intestinal cells is mediated by PXR. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 4230–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Macchiarulo, A.; Thomas, C.; Gioiello, A.; Une, M.; Hofmann, A.F.; Saladin, R.; Schoonjans, K.; Pellicciari, R.; Auwerx, J. Novel potent and selective bile acid derivatives as TGR5 agonists: biological screening, structure-activity relationships, and molecular modeling studies. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahashi, M.; Takabe, K.; Liu, R.; Peng, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hait, N.C.; Wang, X.; Allegood, J.C.; Yamada, A. , et al. Conjugated bile acid-activated S1P receptor 2 is a key regulator of sphingosine kinase 2 and hepatic gene expression. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorucci, S.; Carino, A.; Baldoni, M.; Santucci, L.; Costanzi, E.; Graziosi, L.; Distrutti, E.; Biagioli, M. Bile Acid Signaling in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig Dis Sci 2021, 66, 674–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemi, F.; Poole, D.P.; Chiu, J.; Schoonjans, K.; Cattaruzza, F.; Grider, J.R.; Bunnett, N.W.; Corvera, C.U. The receptor TGR5 mediates the prokinetic actions of intestinal bile acids and is required for normal defecation in mice. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Chen, W.D.; Yu, D.; Forman, B.M.; Huang, W. The G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor, Gpbar1 (TGR5), negatively regulates hepatic inflammatory response through antagonizing nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kappaB) in mice. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Houten, S.M.; Mataki, C.; Christoffolete, M.A.; Kim, B.W.; Sato, H.; Messaddeq, N.; Harney, J.W.; Ezaki, O.; Kodama, T. , et al. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 2006, 439, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, M.J.; Potts, A.; He, T.; Duarte, J.A.; Taussig, R.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Kliewer, S.A.; Burgess, S.C. Colesevelam suppresses hepatic glycogenolysis by TGR5-mediated induction of GLP-1 action in DIO mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schledwitz, A.; Sundel, M.H.; Alizadeh, M.; Hu, S.; Xie, G.; Raufman, J.P. Differential Actions of Muscarinic Receptor Subtypes in Gastric, Pancreatic, and Colon Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufman, J.P.; Dawson, P.A.; Rao, A.; Drachenberg, C.B.; Heath, J.; Shang, A.C.; Hu, S.; Zhan, M.; Polli, J.E.; Cheng, K. Slc10a2-null mice uncover colon cancer-promoting actions of endogenous fecal bile acids. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, E.; Li, Y.; Hylemon, P.B.; Zhou, H. Bile acids and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 in hepatic lipid metabolism. Acta. Pharm. Sin. B. 2015, 5, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Aoki, H.; Yang, J.; Peng, K.; Liu, R.; Li, X.; Qiang, X.; Sun, L.; Gurley, E.C.; Lai, G. , et al. The role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 in bile-acid-induced cholangiocyte proliferation and cholestasis-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology 2017, 65, 2005–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Huang, Z.; Liu, R.; Yang, J.; Hylemon, P.B.; Zhou, H. Sphingosine-1 phosphate promotes intestinal epithelial cell proliferation via S1PR2. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2017, 22, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, S.Y.; Soderholm, J.D. Importance of disrupted intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, H.; Barmeyer, C.; Fromm, M.; Runkel, N.; Foss, H.D.; Bentzel, C.J.; Riecken, E.O.; Schulzke, J.D. Altered tight junction structure contributes to the impaired epithelial barrier function in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1999, 116, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Inca, R.; Di Leo, V.; Corrao, G.; Martines, D.; D’Odorico, A.; Mestriner, C.; Venturi, C.; Longo, G.; Sturniolo, G.C. Intestinal permeability test as a predictor of clinical course in Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 94, 2956–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboc, H.; Rajca, S.; Rainteau, D.; Benarous, D.; Maubert, M.A.; Quervain, E.; Thomas, G.; Barbu, V.; Humbert, L.; Despras, G. , et al. Connecting dysbiosis, bile-acid dysmetabolism and gut inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 2013, 62, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Liu, F.; Zhu, X.R.; Suo, F.Y.; Jia, Z.J.; Yao, S.K. Altered profiles of fecal bile acids correlate with gut microbiota and inflammatory responses in patients with ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 3609–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calmus, Y.; Guechot, J.; Podevin, P.; Bonnefis, M.T.; Giboudeau, J.; Poupon, R. Differential effects of chenodeoxycholic and ursodeoxycholic acids on interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by monocytes. Hepatology 1992, 16, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadaleta, R.M.; van Erpecum, K.J.; Oldenburg, B.; Willemsen, E.C.; Renooij, W.; Murzilli, S.; Klomp, L.W.; Siersema, P.D.; Schipper, M.E.; Danese, S. , et al. Farnesoid X receptor activation inhibits inflammation and preserves the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2011, 60, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.F.; Eferl, R. Fos/AP-1 proteins in bone and the immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2005, 208, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. Bile acid nuclear receptor FXR and digestive system diseases. Acta. Pharm. Sin. B. 2015, 5, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorucci, S.; Cipriani, S.; Mencarelli, A.; Renga, B.; Distrutti, E.; Baldelli, F. Counter-regulatory role of bile acid activated receptors in immunity and inflammation. Curr. Mol. Med. 2010, 10, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.W.; Andersson, R.; Soltesz, V.; Willen, R.; Bengmark, S. The role of bile and bile acids in bacterial translocation in obstructive jaundice in rats. Eur. Surg. Res. 1993, 25, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, T.; Moschetta, A.; Lee, Y.K.; Peng, L.; Zhao, G.; Downes, M.; Yu, R.T.; Shelton, J.M.; Richardson, J.A.; Repa, J.J. , et al. Regulation of antibacterial defense in the small intestine by the nuclear bile acid receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 3920–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeke, L.; Farre, R.; Verbinnen, B.; Covens, K.; Vanuytsel, T.; Verhaegen, J.; Komuta, M.; Roskams, T.; Chatterjee, S.; Annaert, P. , et al. The FXR agonist obeticholic acid prevents gut barrier dysfunction and bacterial translocation in cholestatic rats. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keely, S.J.; Walters, J.R. The Farnesoid X Receptor: Good for BAD. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, J.R.; Johnston, I.M.; Nolan, J.D.; Vassie, C.; Pruzanski, M.E.; Shapiro, D.A. The response of patients with bile acid diarrhoea to the farnesoid X receptor agonist obeticholic acid. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroz, M.S.; Keating, N.; Ward, J.B.; Sarker, R.; Amu, S.; Aviello, G.; Donowitz, M.; Fallon, P.G.; Keely, S.J. Farnesoid X receptor agonists attenuate colonic epithelial secretory function and prevent experimental diarrhoea in vivo. Gut 2014, 63, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.M.; Zhan, L.; Maru, D.; Shureiqi, I.; Pickering, C.R.; Kiriakova, G.; Izzo, J.; He, N.; Wei, C.; Baladandayuthapani, V. , et al. FXR silencing in human colon cancer by DNA methylation and KRAS signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2014, 306, G48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, R.R.; Thomas, A.; Roth, M.; Sheng, Z.; Esterly, N.; Pinson, D.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ganapathy, V.; Gonzalez, F.J. , et al. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency in mice leads to increased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and tumor development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009, 328, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocvirk, S.; O’Keefe, S.J.D. Dietary fat, bile acid metabolism and colorectal cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 73, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Xie, S.; Chi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Xia, D.; Ke, Y. , et al. Bile Acids Control Inflammation and Metabolic Disorder through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Immunity 2016, 45, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perino, A.; Pols, T.W.; Nomura, M.; Stein, S.; Pellicciari, R.; Schoonjans, K. TGR5 reduces macrophage migration through mTOR-induced C/EBPbeta differential translation. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 5424–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, A.; Jamma, T. UDCA ameliorates inflammation driven EMT by inducing TGR5 dependent SOCS1 expression in mouse macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, M.; Carino, A.; Cipriani, S.; Francisci, D.; Marchiano, S.; Scarpelli, P.; Sorcini, D.; Zampella, A.; Fiorucci, S. The Bile Acid Receptor GPBAR1 Regulates the M1/M2 Phenotype of Intestinal Macrophages and Activation of GPBAR1 Rescues Mice from Murine Colitis. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Backhed, F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Bai, Y.; Hou, R.; Chen, G.; Liu, L.; Ciftci, O.N.; Farag, M.A.; Liu, L. Advances in dietary polyphenols: Regulation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) via bile acid metabolism and the gut-brain axis. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, C.; Xie, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yang, S.; Tian, Q.; Song, C.; Chen, S. Multi-omics reveals the alleviating effect of berberine on ulcerative colitis through modulating the gut microbiome and bile acid metabolism in the gut-liver axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1494210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Jia, Y.Q.; Liu, W.J.; Niu, C.; Mai, Z.H.; Dong, J.Q.; Zhang, X.S.; Yuan, Z.W.; Ji, P.; Wei, Y.M. , et al. Pulsatilla decoction alleviates DSS-induced UC by activating FXR-ASBT pathways to ameliorate disordered bile acids homeostasis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1399829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yang, P.; Liu, B.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, M.; Gong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, M. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide remodels colon inflammatory microenvironment and improves gut health. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Lei, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, F. , et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-Derived Bile Acid from Dietary Carvacrol and Thymol Supplementation Attenuates Colitis via cGMP-PKG-mTORC1 Pathway. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2406917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nood, E.; Vrieze, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Fuentes, S.; Zoetendal, E.G.; de Vos, W.M.; Visser, C.E.; Kuijper, E.J.; Bartelsman, J.F.; Tijssen, J.G. , et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullish, B.H.; McDonald, J.A.K.; Pechlivanis, A.; Allegretti, J.R.; Kao, D.; Barker, G.F.; Kapila, D.; Petrof, E.O.; Joyce, S.A.; Gahan, C.G.M. , et al. Microbial bile salt hydrolases mediate the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplant in the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Gut 2019, 68, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekatz, A.M.; Theriot, C.M.; Rao, K.; Chang, Y.M.; Freeman, A.E.; Kao, J.Y.; Young, V.B. Restoration of short chain fatty acid and bile acid metabolism following fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Anaerobe 2018, 53, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramsothy, S.; Nielsen, S.; Kamm, M.A.; Deshpande, N.P.; Faith, J.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Paramsothy, R.; Walsh, A.J.; van den Bogaerde, J.; Samuel, D. , et al. Specific Bacteria and Metabolites Associated With Response to Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1440–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibiloni, R.; Fedorak, R.N.; Tannock, G.W.; Madsen, K.L.; Gionchetti, P.; Campieri, M.; De Simone, C.; Sartor, R.B. VSL#3 probiotic-mixture induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 100, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jingjing, F.; Weilin, J.; Shaochen, S.; Aman, K.; Ying, W.; Yanyi, C.; Pengya, F.; Byong-Hun, J.; El-Sayed, S.; Zhenmin, L. , et al. A Probiotic Targets Bile Acids Metabolism to Alleviate Ulcerative Colitis by Reducing Conjugated Bile Acids. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Dong, S.; Xu, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Luo, H. , et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid Reverses Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice via Modulation of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Microbiome Dysregulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2024, 390, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).