1. Introduction

Induction machines (IMs) are promising electrical motor use in industry and for electric vehicle with their performances as high efficient, low cost and almost free maintenance. Recently, the systems including power converters and electric motors have been widely used for electric vehicles. The acoustic noise generated by the induction motor drive as a variable-speed drive becomes a problem to the living environment, and even a slight noise may cause discomfort. The audible range of humans is generally from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. In recent years, the acoustic noise emitted by electric motors has the subject of numerous studies. The acoustic noise sources can be grouped into four types: mechanic, aerodynamic, magnetic, and electronic [

1,

2,

3]. This work focuses on the study of noise electronic and accordingly in switching harmonics source. The flux harmonics in the air-gap of an IM create radial forces in the stator frame. Thus, these harmonics cause excitation forces that have a detrimental effect on the structure machine. Consequently, considerable emission of vibration and noise can be engendered, which makes the machine more troublesome to operate. Generally, the main reasons of the harmonics in the air-gap flux reported in the literature are:

- -

Spatial harmonics due to the non-sinusoidal repartition of coils in stator and rotor.

- -

Harmonics in the air-gap permeance, which depend on the number and the geometry of the stator and rotor slots, the geometry of teeth in both the stator and the rotor, and the permeation in the iron core.

- -

Harmonic currents in the stator coil.

IMs are driven solid-state inverter drive systems where the power voltages are non- sinusoidal and consequently full in harmonics. Besides, the harmonics absorbed by the stator coils generate additional stator flux density components and, hence, additional force waves to be produced. Voltage Source Inverter VSI-fed IMs produce disagreeable acoustic noise cause to harmonics currents at inverter output. Consequently, these harmonics are located narrow-band components around the inverter switching frequency and its multiples. Furthermore, an analysis of harmonic spectrum of the voltage or current could determine and define the frequencies and amplitudes of the different harmonics at the inverter output. In fact, noise intensity depends on harmonic spectrum of inverter output, which also correlated to the PWM strategy control applied to the inverter. Motor drives modulated with such PWM methods invariably emit discrete/tonal noises, which are irritating to the human ear.

Numerous PWM techniques have been developed and proposed in the literature. Sine Pulse Width Modulation (SPWM) and Space Vector PWM (SVPWM) are well-known fixed-switching frequency PWM methods applied in industry. Using SPWM strategy, the inverter harmonic was concentrated in distinct zones located around the switching frequency and its integer multiples. However, SVPWM strategy has the advantages of a high voltage utilization and would offer reduced current. Also, the harmonics are decreased and are concentrated around integer multiples of the VSI switching frequency, compared to SPWM strategy. The acoustic noise emitted by IM fed by PWM inverter remained very interesting, considering the numerous articles published lately. [

4,

5] elaborated an experimental procedure to determine the acoustic and vibration behavior of SVPWM modulated IM drives over a range of carrier frequencies and modulation frequencies. An advanced SVPWM scheme with a special type of switching sequence, has also been reported to reduce the acoustic noise in the low and medium speed ranges of the motor drive [

6]. Many researchers recently have published and investigated on the Random Pulse Width Modulation (RPWM) technique in order to reduce and dispersed over a wide range of frequencies the tonal bands around the multiple of the switching frequency with the fixed PWM. Many schemes proposed for both DC-DC and DC-AC converters [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. [

7] proposed a novel Hybrid Random PWM (HRPWM) technique based on the modified SVPWM for three-phase VSIs to eliminate the PWM acoustic noise. The proposed HRPWM technique is able to remove the high frequency unpleasant acoustic noise more effectively than fixed PWM with lower switching losses and shorter random frequency range. The effects of the SVPWM, Selective Harmonic Elimination PWM SHEPWM and Random RPWM strategies have been developed in our study [

8]. The acoustic noise emitted by a two-level inverter-fed IM and harmonic spectrum are carried out corresponding the three PWM techniques at different conditions. Consequently, the experimental results show that the acoustic noise and harmonic spectrum are significantly reduced with the random RPWM strategy. Nowadays, many researchers in bibliography published and investigated on the random SVPWM strategy effect in terms of acoustic noise emitted by the electric motor [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The SVPWM is very well considered in industry on account of higher dc bus utilization and superior waveform properties compared to the other PWM techniques. Based to the switching signal for VSI modulated with SVPWM technique, three parameters can be randomized. The three randomization schemes are: Random Switching Frequency (RSF), Random Zero Vector (RZV) and Random Pulse Position (RPP). For the three-phase inverter, the switching signals are generated by comparing three deterministic reference signals to a triangular carrier with random parameters.

This paper presents the simulation and experimental implementation of the fixed SVPWM and three random SVPWM schemes: Random Switching Frequency SVPWM (RSFSVPWM), Random Zero Vector SVPWM (RZVSVPWM) and Random Pulse Position SVPWM (RPPSVPWM). The investigation of spectral characteristics in terms of harmonic spectra and acoustic noise emitted by an induction machine is studied and discussed. Therefore, this document is structured as below:

Section 2 presents the description of acoustic noise on electric machine. In

Section 3, principles of the advanced SVPWM techniques are presented. In

Section 4, the PWM two levels inverter and the IM is applied using Simulink and obtained simulation results are presented and discussed. An experimental setup of an PWM inverter and IM is presented in

Section 5, and the experimental tests of emitted noise are given and discussed. Some general conclusions are provided in

Section 6.

2. Acoustic Noise Sources of an Electric Machine

For several years, the search to guarantee the best operating performance for IM powered by static converters has been the subject of numerous research and development projects. Electrical machines, including IMs, constitute major noise sources in industry. Noise exposure leads to psycho-acoustic and health problems for human being.

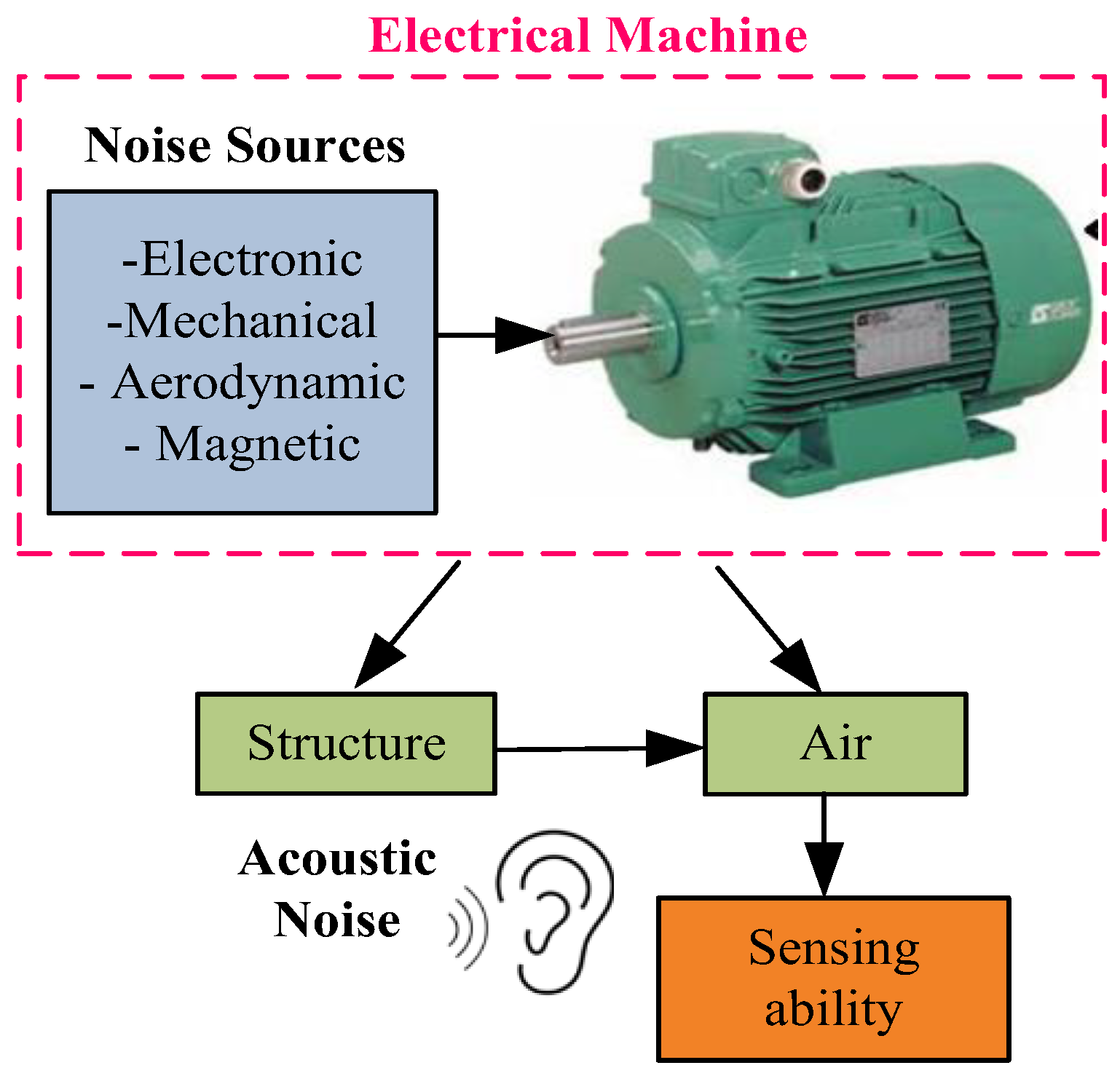

Figure 1 demonstrates the mechanism for generating noise in an electrical machine. Thus, this system is characterized on the one hand by the noise source (electric motor) as principal cause of acoustic phenomenon, on the other hand by the elements related to perception and sensation by the human ear. The overall noise level in an electrical machine originates from four main sources. Considerable efforts have been made to identify the acoustic noise sources of an electrical machines [

1,

2,

3,

22]. These can be subdivided further to four main sources: electronic, mechanical, magnetic and aerodynamic. These sources provide also the excitation forces that act on the internal structure of the stator core. The pressure of the ambient air varies periodically under the effect of vibrations, and this results in the noise creation. Consequently, the sound wave is audible to the human ear. In this study, the noise electronic and accordingly in the switching harmonics is studied.

A voltage inverter produces voltages contains harmonics, that can cause considerable noise, particularly when their frequencies are close to those proper to the machine. Furthermore, the harmonics absorbed by the stator windings produce additional stator flux density components and, consequently, the generation of other magnetic force components. The frequency of voltage harmonics can be obtained as the following:

Where, F: the fundamental frequency, Fc is the switching frequency and (n1 and n2) are integers.

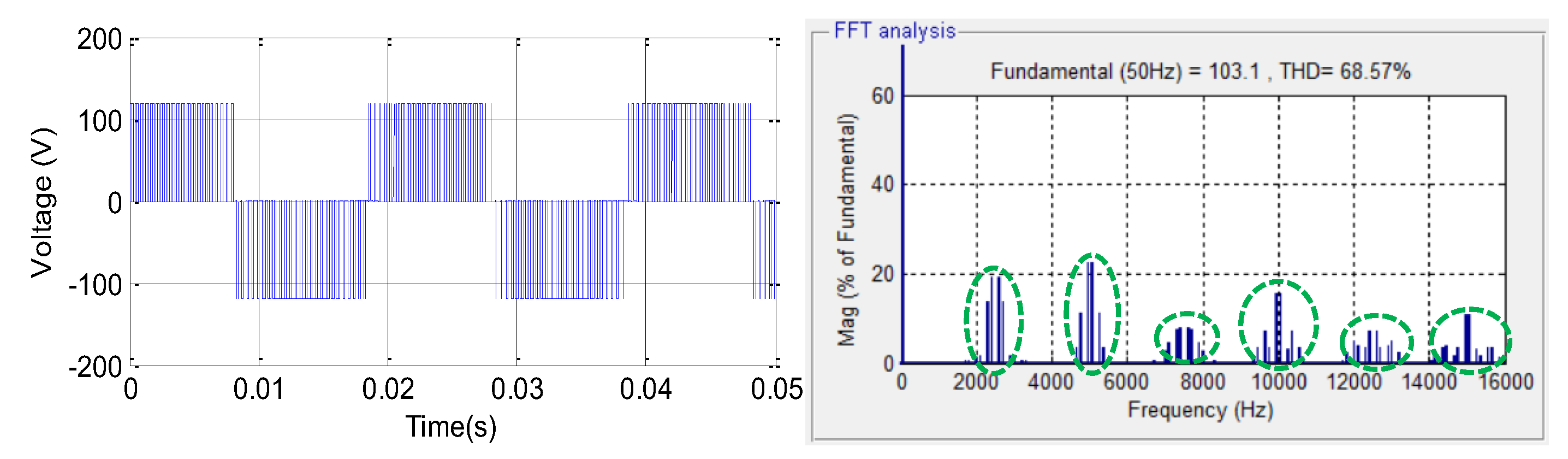

An example of voltage waveform at the output of a three-phase inverter and its Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) for a switching frequency Fc of 2.5 kHz are presented in

Figure 2. The harmonic components are distributed in groups of sidebands near the switching frequency and its multiple is shown.

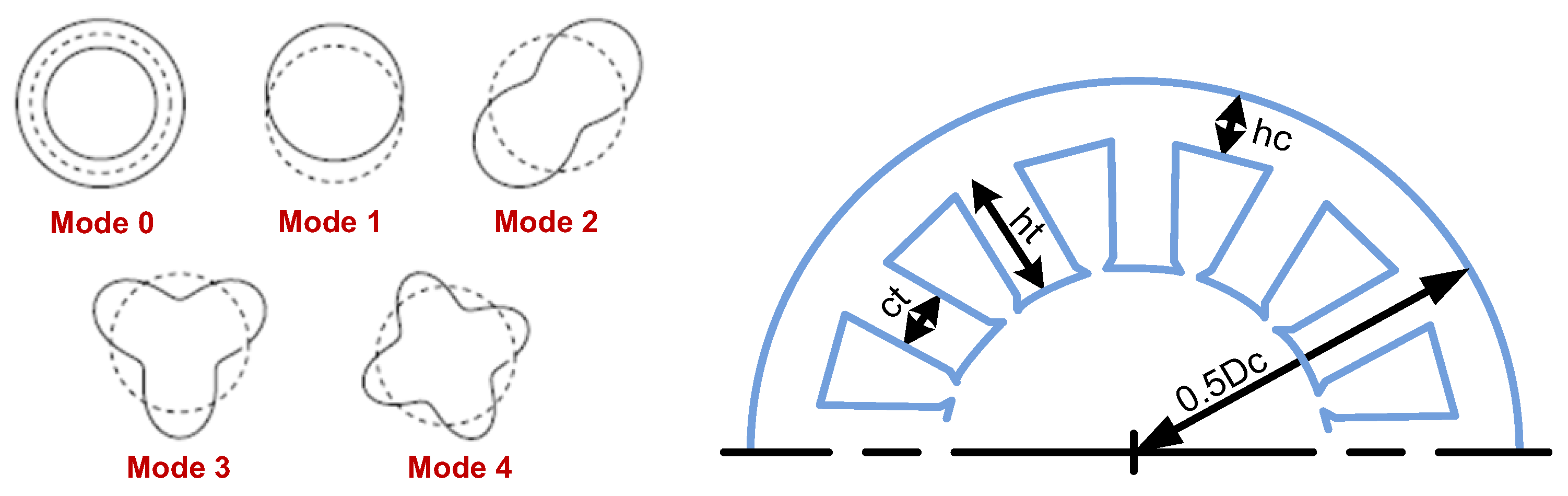

In electric machines, the harmonics components in the air gap generate radial forces applied to the stator, tending to dynamically deform its structure. In this way, the stator is stressed by multiple deflection. Generally, the mechanical behavior of the machine stator can be characterized by its natural modes of vibration. Each mode, corresponding to a proper frequency, represents a particular deformation of the structure [

8]. The stator and geometry of stator ring and teeth and main modes of stator deformation are shown in

Figure 3:

Equation 2 gives the natural frequency F0 of the order vibration mode m=0 [

8]:

Where, Dc is the average diameter of the stator core, Ec is the elasticity modulus, is the density, ki is the piling factor and kmd is the mass addition factor for the displacement.

The natural frequency F1 of the first-order vibration mode m=1 is expressed by:

Where Kmrot is the mass addition factor,

and hc is the stator thickness.

Where: sl: is the stator tooth number, ct: is the tooth width, ht: is the tooth height, Mt is the mass of the stator teeth, Mw is the mass of the stator windings, Mi is the insulation mass and Ic is the surface moment of inertia near the axis parallel to the cylinder axis.

Generally, the expression of the natural frequencies Fm of the vibration mode m≥ 2 is defined by:

The expression of fm is defined as follows:

3. Random SVPWM

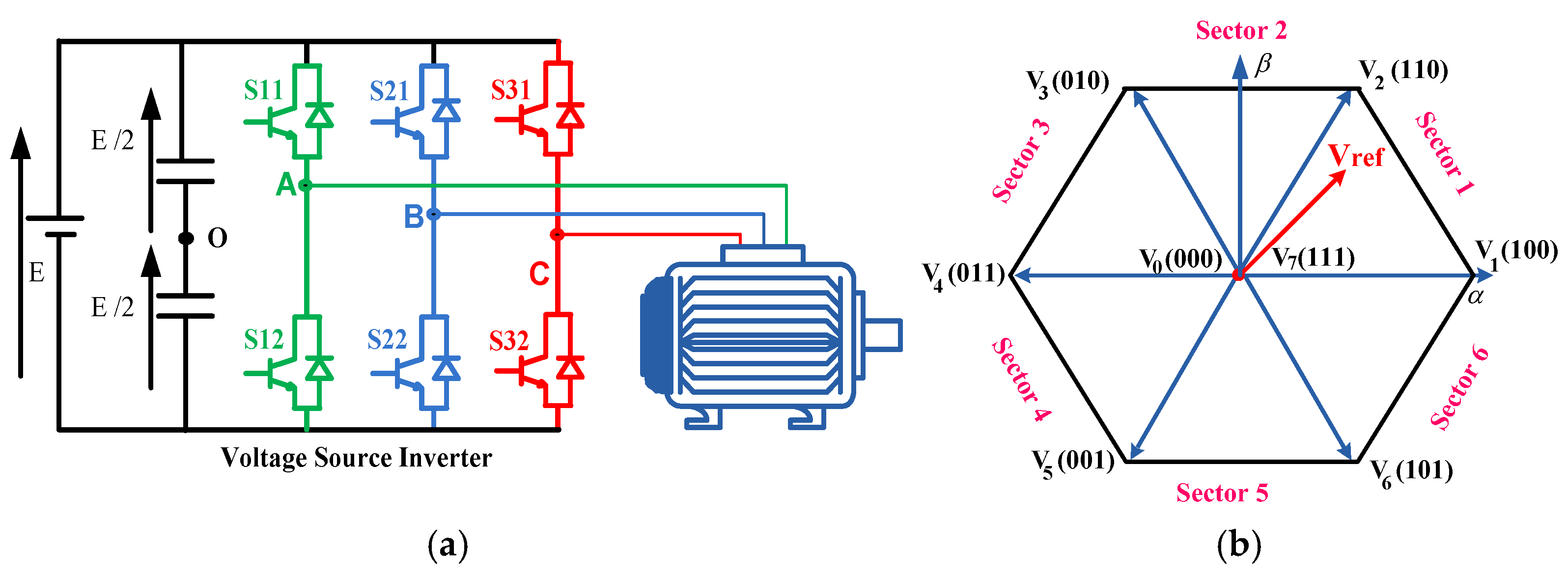

The power circuit structure of VSI two level supplying an IM is also illustrated by the

Figure 4. SVPWM is a digital technique founded on the representation of three reference voltages by single space vector. For the two-level inverter, eight possible combinations of power switch states yield eight vectors whose two vectors are inactive because they are identically zero. The six non-zero vectors in the plane (α, β)are given in the form of standard hexagon whose origin aligned to the zero vectors, as shown in

Figure 4.

The general expressions for reference voltages of amplitude Vm are given by the system of equations (7):

Where: The amplitude of the sine wave, im: modulation index and: The pulsation.

The vector V0 is applied during a duty cycle noted d0 and the two adjacent active vectors V1 and V2 are applied respectively during the cyclic ratios d1 and d2. The general expressions for the duty cycles d0, d1 and d2 are given by:

Where, the instantaneous angle, s the sector and Vref the reference space vector.

The SVPWM algorithm subdivides sectors and transforms reference vector into active vectors, which is demonstrated by

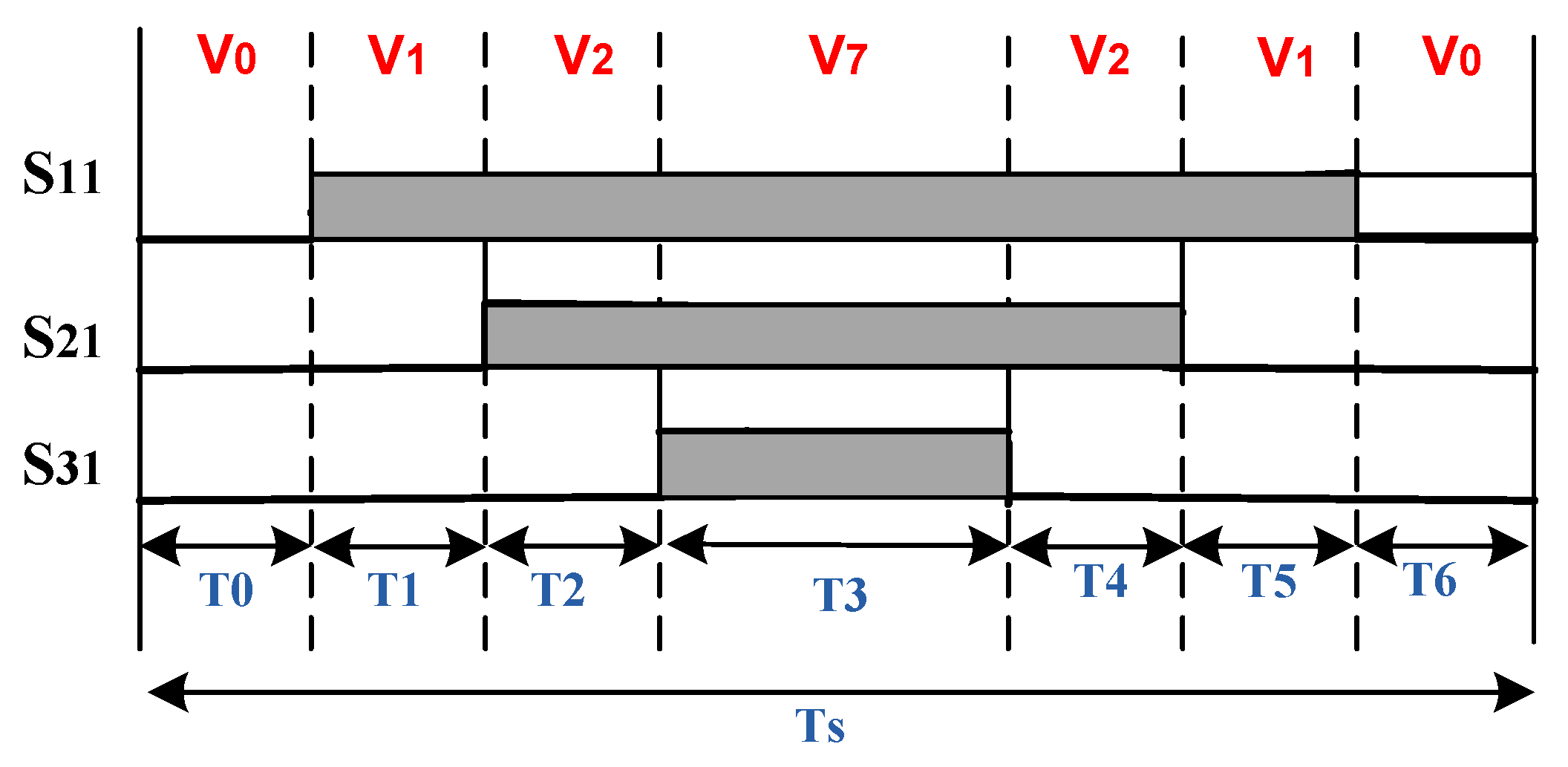

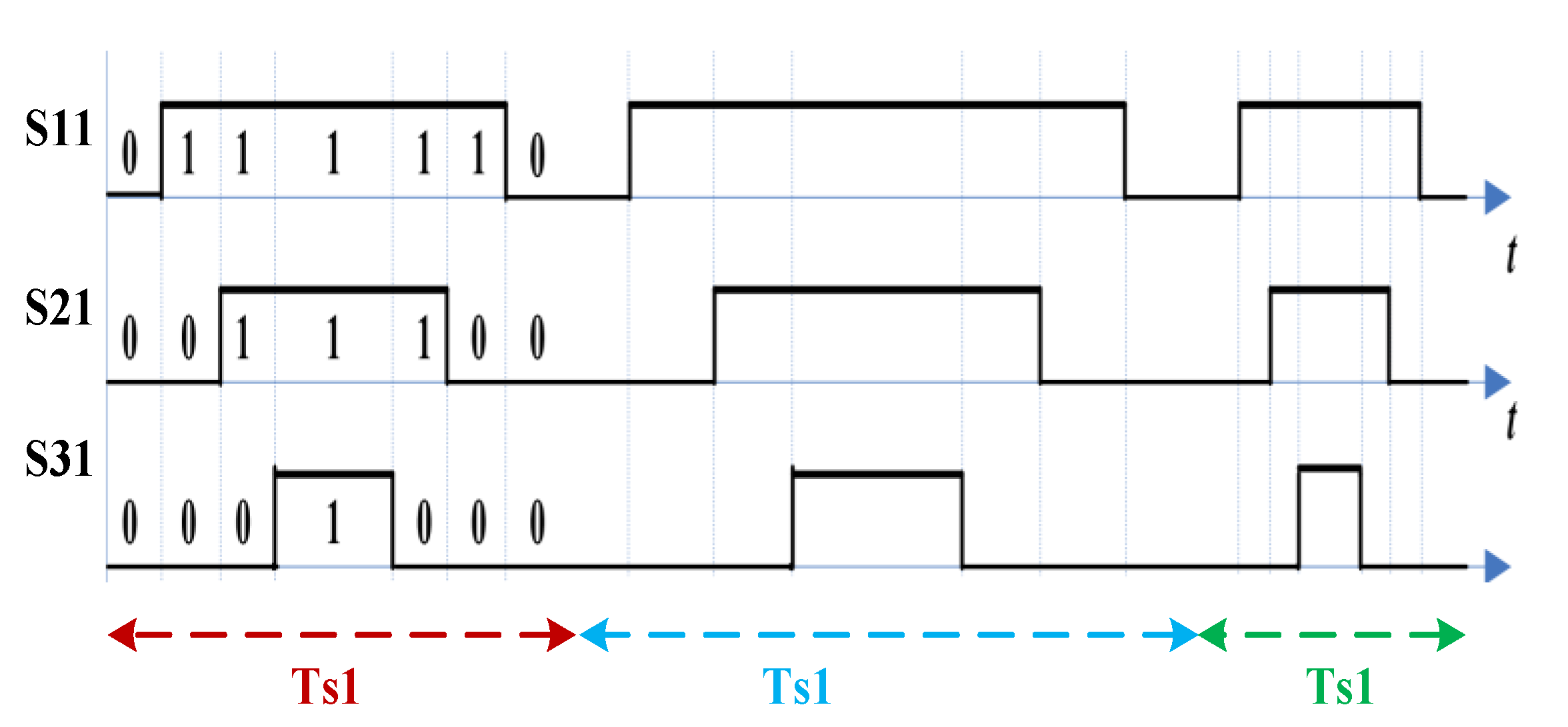

Figure 4. The SVPWM strategy is performed by rotating the space vector. Thus, the control signals are elaborated by applying the sector number determination and duty cycles calculation. The triangular carrier wave for the fixed SVPWM algorithm widely adopts the up and down counting mode of the timer. During the PWM modulation process, the modulation wave and the carrier wave are compared at fixed switching frequency. The three-phase inverter requires three switching signals: S11, S21 and S31. The switching state distribution where the reference voltage Vref is positioned in first sector is explained by

Figure 5.

The durations of switching signals for the SVPWM control are obtained and computed using the following relations:

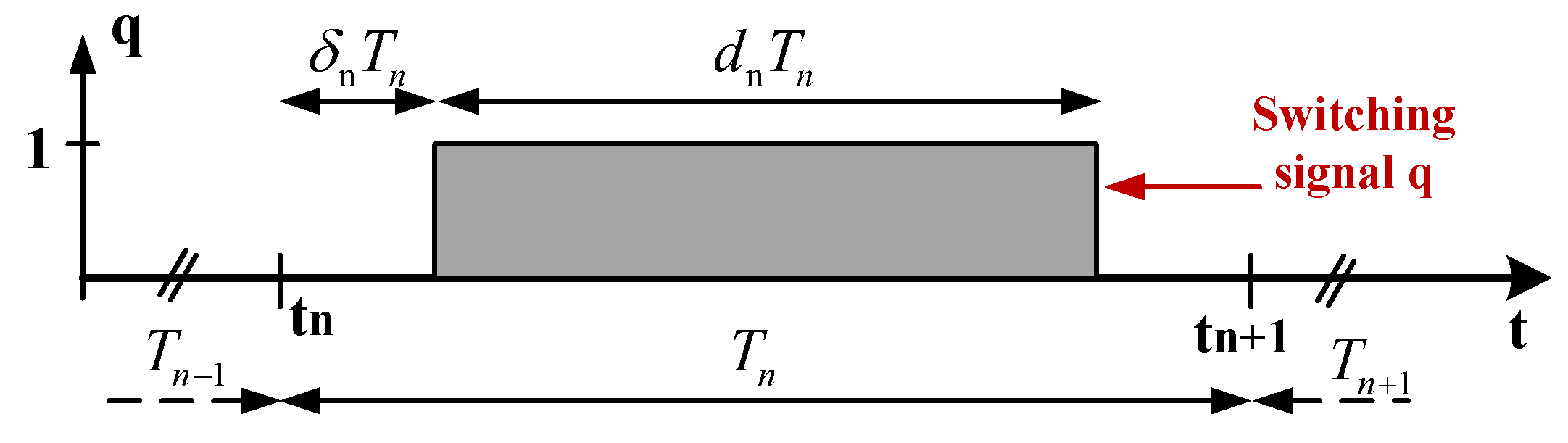

Figure 6 displays the general case of a switching signal q for VSI three phase, which can be characterized by three parameters: the switching period T, the duty cycle d and the delay report δ.

Furthermore, three advanced random SVPWM algorithms can be obtained such as: Random Zero Vector SVPWM (RZVSVPWM), Random Pulse Position SVPWM (RPPSVPWM) and Random Switching Frequency SVPWM (RSFSVPWM). The RZVSVPWM control consist to lead the period T and the delay report δ are deterministic, as well as the duty cycle d is random [

10,

11,

12].

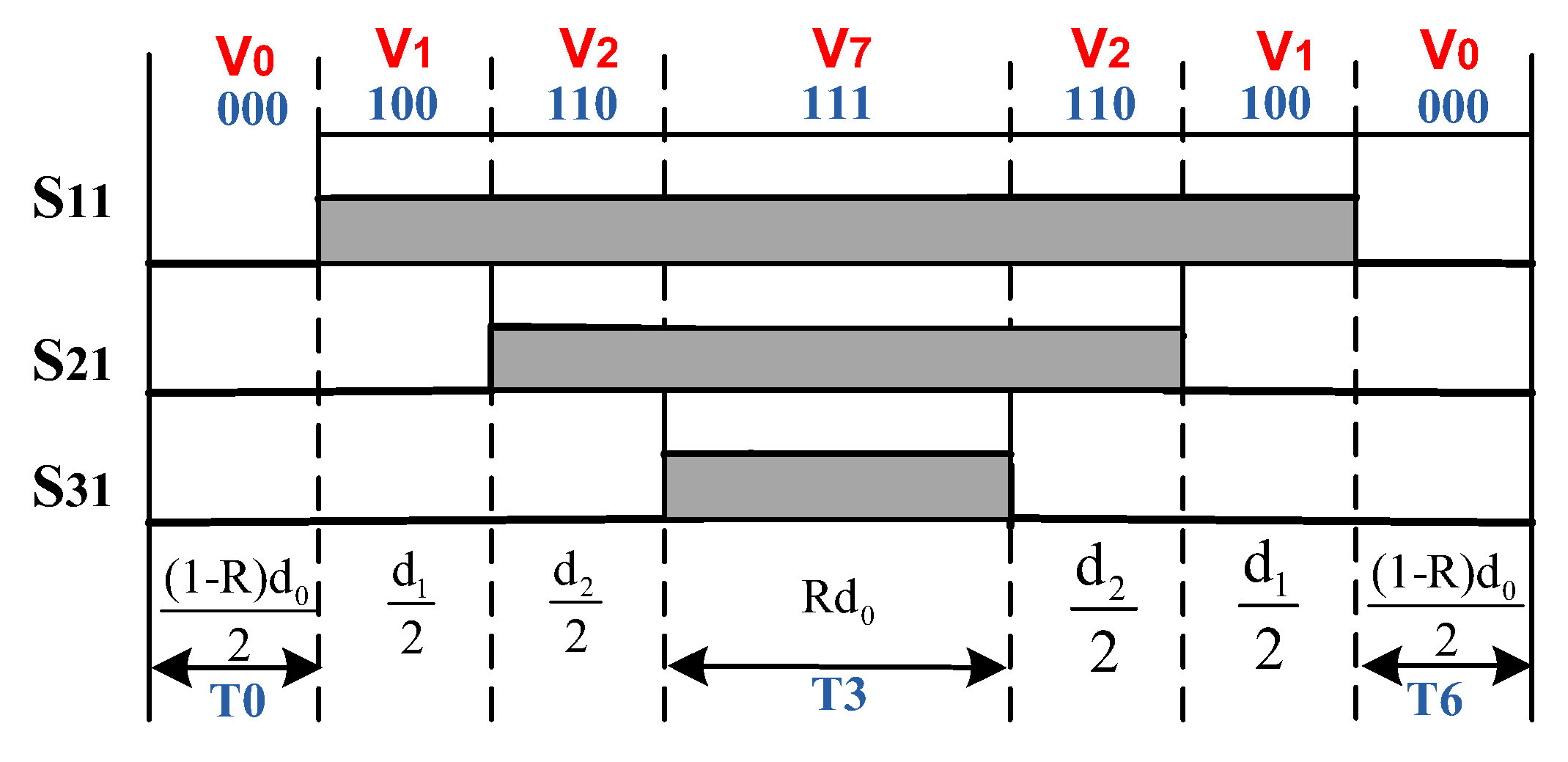

Figure 7 displays the switching state distribution at sector 1 for RZVSVPWM control. The zero voltage vectors randomized the zero voltage vectors V7 and V0. The sum of the durations (T0 + T6) of zero vector state V0 is complementary to that of zero voltage vector V7 during period T3. Thus, the durations T3, T0 and T6 are determined as follows:

Where, R is a random number between 0 and 1.

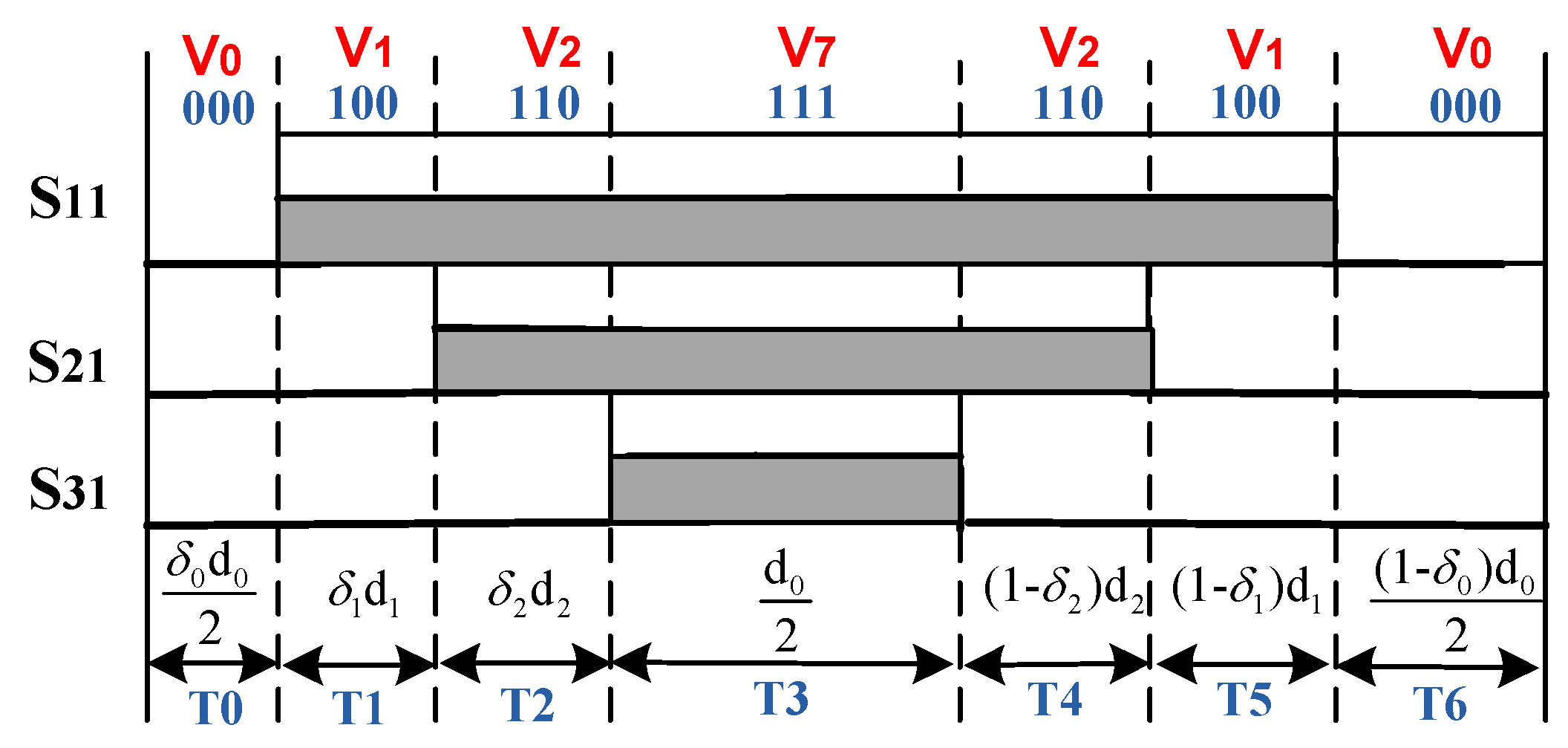

Figure 8 shows the switching pulses at sector 1 for the random RPPSVPWM control. The period T and duty cycle d of the switching signal are deterministic and the delay report δ is random. Thus, the pulse positions randomize by varying the durations of the vectors states V0, V1 and V2 respectively by the random parameters δ0, δ1 and δ2 [

10,

11,

12].

According to the random parameters δ0, δ1 and δ2, the durations expressions are defined by:

The variation interval for random parameter δi(i = 0, 1, 2) is given by :

Where is statistical mean of random parameter δi and is randomness level. Theoretically is also a random number between 0 and 1.

The Random RSFSVPWM exploits the possibility of changing randomly the period T of the switching signal and to keep the duty cycle and delay report. Yet, for this algorithm, the triangular carrier wave is randomly changed. Since Fs=1/Ts, the random change can be completed by changing the time of the triangular carrier. Also, for the case at sector 1, the signal generation mode of the RSFSVPWM control is shown in

Figure 9. In addition, when the timer period count value is randomly changed, consequently the different switching cycles Ts1, Ts2, and Ts3 change to make the random adjustment of the switching frequency.

The limit of variation interval of the period T is given as follows:

Where

is the statistical mean of the randomized period T and RT is the randomness level; it determines the interval in which T is randomized. The minimum value of randomness level is theoretically (RT)min=0 and the maximum value is (RT)max=2 and therefore the variation interval of the period is randomized between 0 and

Consequently, the instantaneous switching period T is expressed by:

The Tmin and Tmax terms can be explained as follows:

Replacing Tmax and Tmin by their values in Equation (14) we get:

Where R is a series of uniformly distributed random numbers in the interval [0, 1].

Therefore,

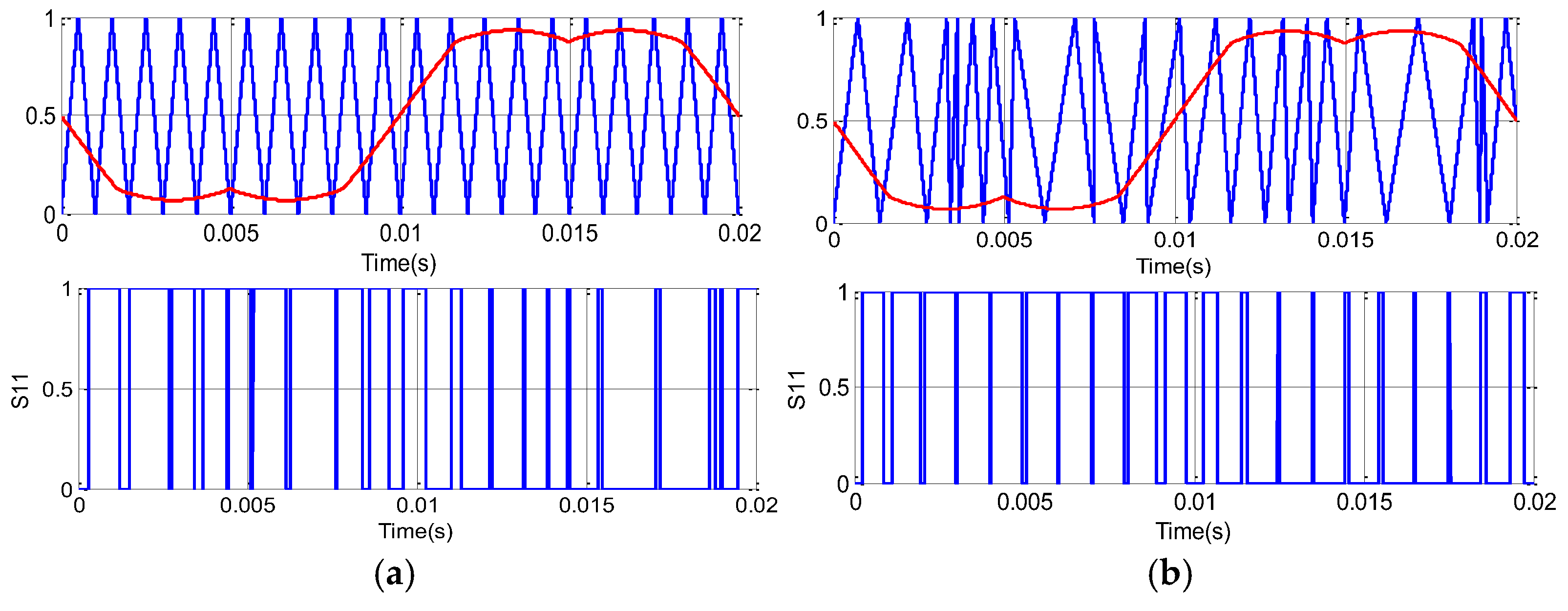

Figure 10 depicts the waveforms random frequency carrier VT, modulation wave signal and the switching sequence of switch S11 for two-level VSI respectively for the SVPWM and RSFSVPWM controls.

4. Simulation Analysis

Numerical simulation model of an IM fed by a two level VSI controlled with SVPWM, RSFSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RZVSVPWM are developed and implemented on MATLAB/Simulink. In addition, the simulation results examine the characteristics of harmonic current spectra and the dynamic response of drives at different modulation indexes. The machine parameters are mentioned in Table 1. The simulations are performed under the same conditions: Input voltage: E = 560 V, switching frequency Fc = 5 kHz, fundamental frequency F = 50 Hz. For all random SVPWM controls, the uniform probability density function is used to perform all randomizations.

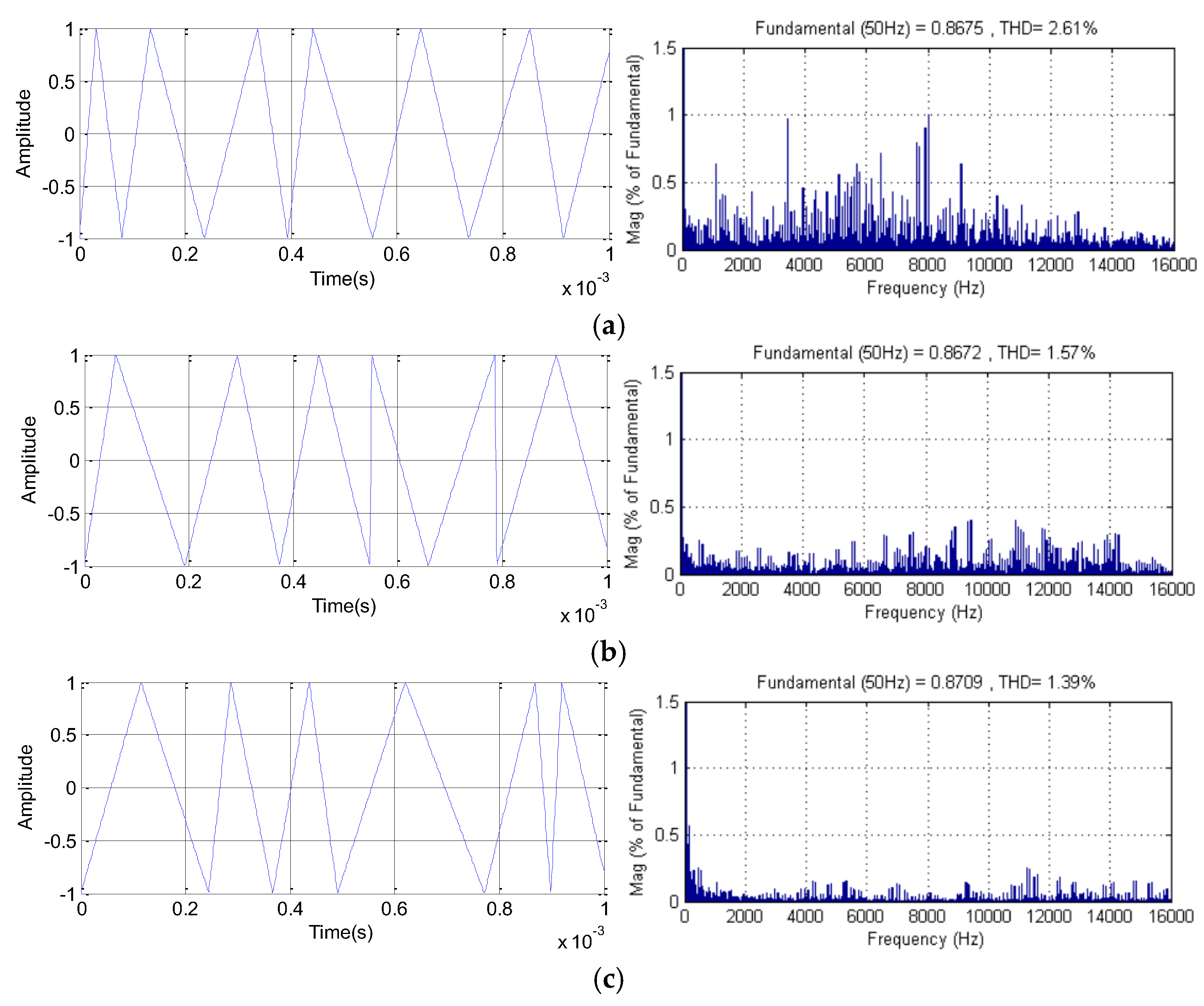

For the random RSFSVPWM control, the randomness level RT plays a key role, since the distribution of harmonic spectra is affected by parameters of the random triangular carrier. Hence, the RT parameter identifies the varying width of the PWM technique. The methodology to select the parameter of the triangular carrier is to make a sequence of simulation tests with different values of RT. Generally, in practice, the randomness level RT does not exceed generally 0.5. We can note if RT= 0, we are in the case of constant switching frequency. In order to estimate the most appropriate RT parameter, a series of simulation tests are carried out to determine the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) of the current corresponding to each RT value. The results of harmonic spectra of each randomness level signals (RT = 0.5, 0.3 and 0.1) are shown in

Figure 11. For, RT = 0.5, the triangular signal begins to vary randomly. As well, we notice that the harmonic peak begins to attenuate with RT = 0.3. In addition, it is clear that the RFSVPWM with RT = 0.1 provides a significant reduction in the THD value by 1.39%, without neglecting the considerable reduction of the harmonic peak amplitude at the switching frequency and its multiples by spreading the energy spectrum over a wide frequency band. In this case, obtained results from the random RSFSVPWM with randomness level RT= 0.1 are more coherent and robust and decrease significantly the THD value compared to the other cases.

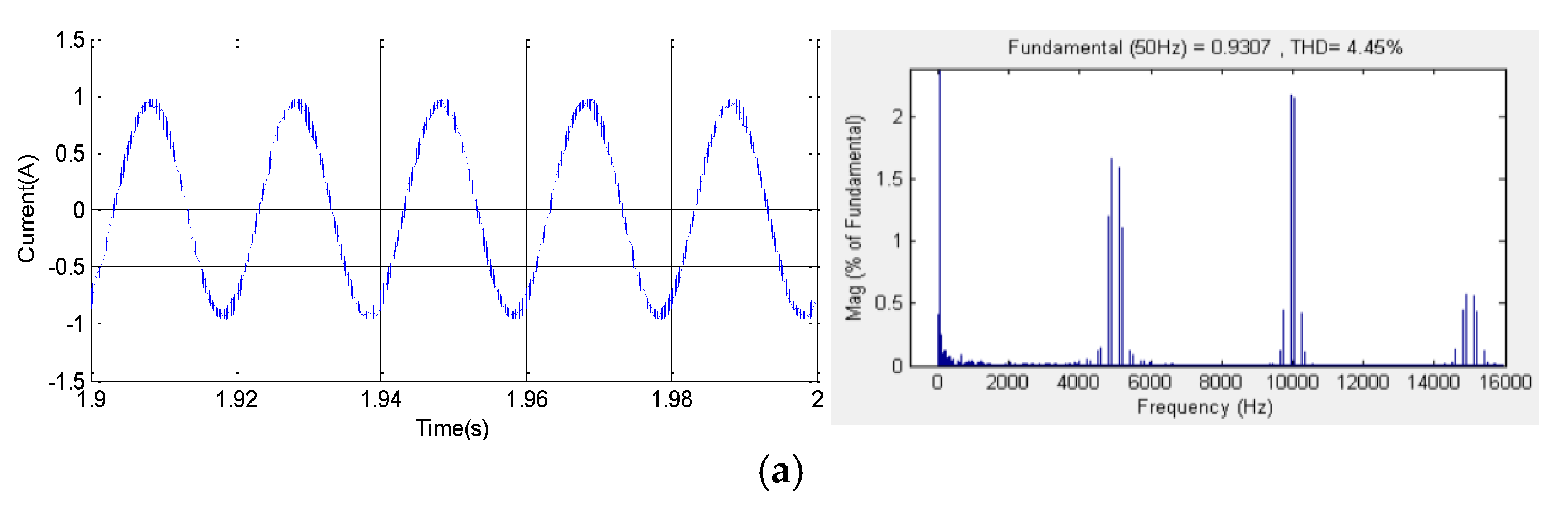

The PWM acoustic noise depends largely on the current noises.

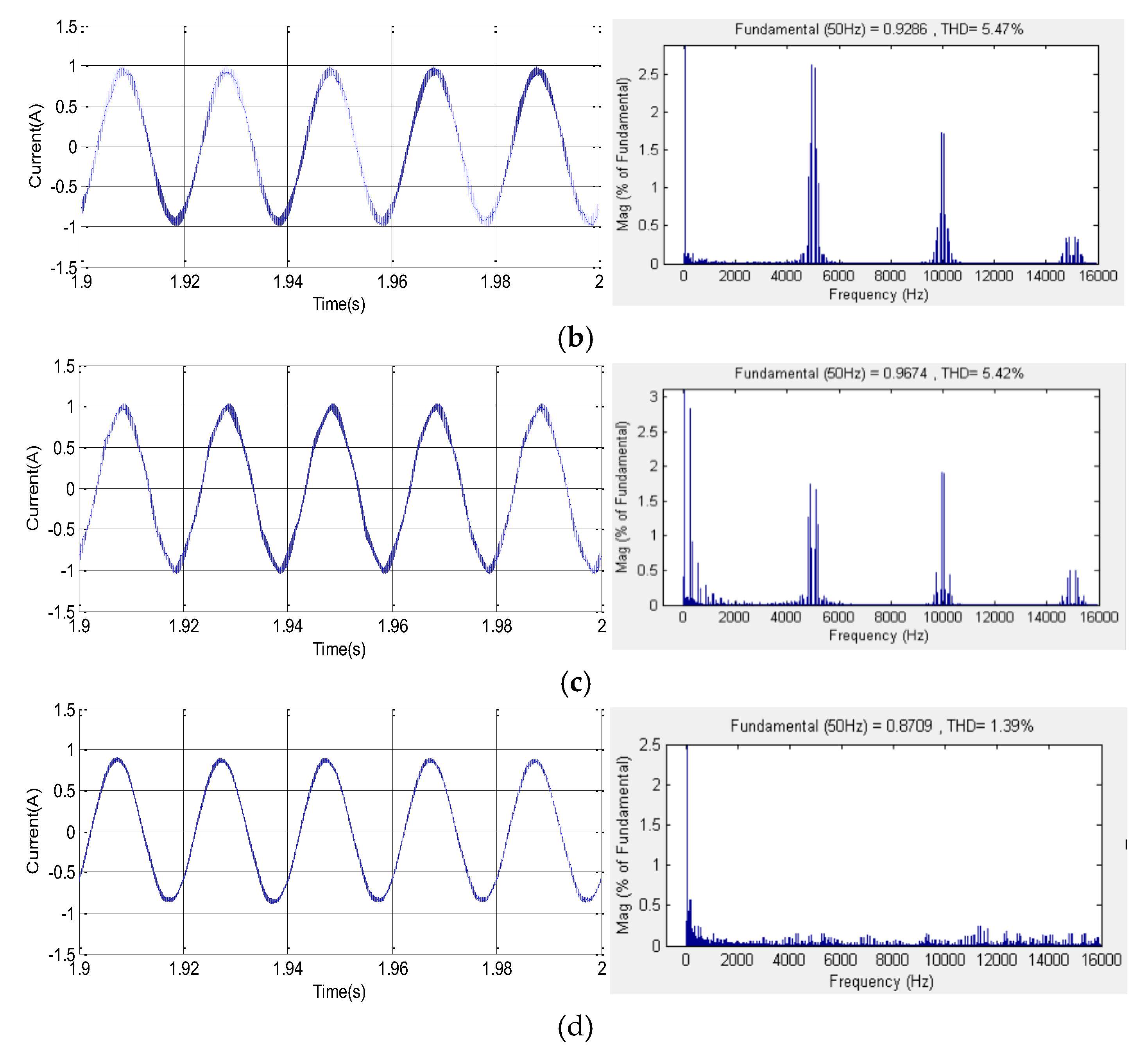

Figure 12 presents the stator current and their harmonic spectra waveforms for (im = 0.8, Fc =5 KHz) corresponding to the studied techniques SVPWM, RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RSFSVPWM respectively. The corresponding obtained THD values are (4.45%, 5.47%, 5.42% and 1.39%), respectively. Referring to the obtained results, it can be clearly noted that the high harmonic components are significantly and more important generated by SVPWM, RZVSVPWM and RPPSVPWM methods compared to the random RSFSVPWM. Therefore, the dominant magnitudes of current harmonics are concentrated on the switching frequency and its multiples. In addition, the magnitudes dominants harmonic around the first switching frequency Fc are 1.66 A, 2.63 A, 1.74 A, respectively for SVPWM, RZVSVPWM and RPPSVPWM. Thus, the magnitudes of harmonics around the second switching frequency Fc are 2.17 A, 1.72 A, 1.92 A, respectively. However, for the RSFSVPWM scheme, as depicted in results it is observed that there is a considerable reduction in the harmonic content. Nevertheless, the harmonic spectrum is totally spread better over the entire frequency band of the current and the band around the switching frequency and its multiples are disappeared.

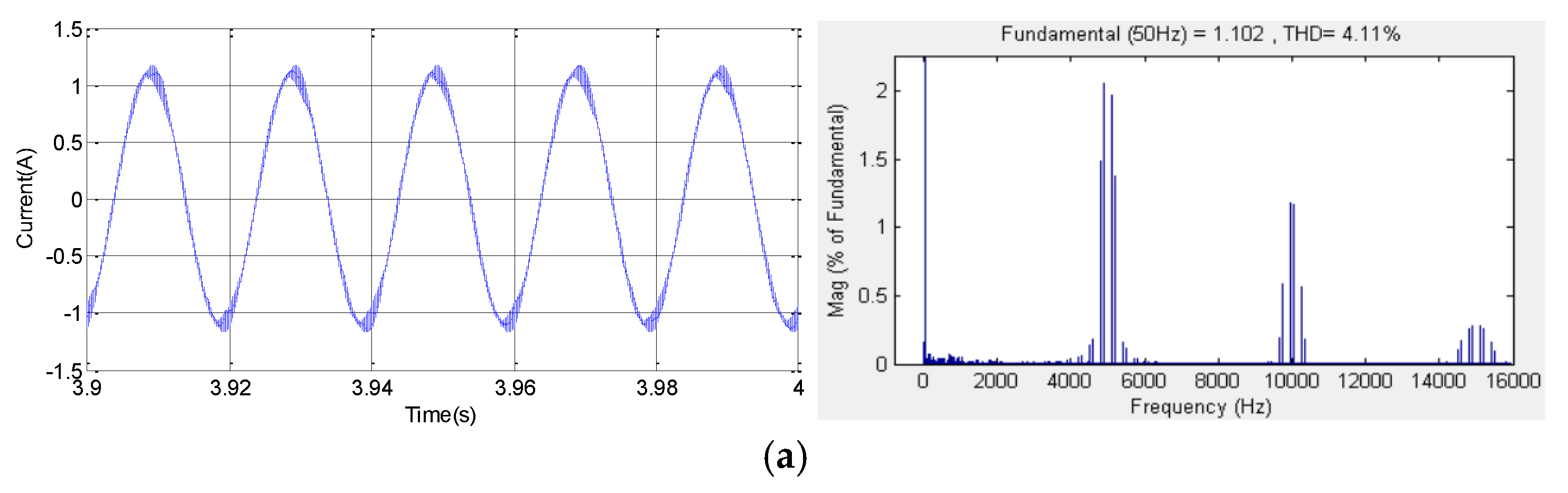

Figure 13 represents the stator current and harmonic spectra waveforms corresponding to the proposed strategies SVPWM, RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RSFSVPWM for (im = 1, Fc =5 KHz). Thus, the corresponding obtained THD values are (4.11%, 4.37%, 4.32% and 1.28%), respectively. In addition, it can be clearly noted that for all proposed strategies, the harmonic component of the stator current is improved and decreased compared to im = 0.8. Furthermore, for the SVPWM, RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM strategies, the dominant harmonic is located around the switching frequency and its multiples. The important harmonic is appeared around the first switching frequency. In addition, the magnitudes dominants harmonic around Fc are 2.06 A, 2.03 A, 2.15 A, respectively. Thus, the magnitudes of harmonics around 2Fc are 1.18 A, 1.12 A, 0.8A, respectively. In the other side, as shown by the simulation results, it is evident note that RSFSVPWM control has the most effective in reducing and spreading the peaks harmonic over the entire frequency band particularly at first and second switching frequency Fc.

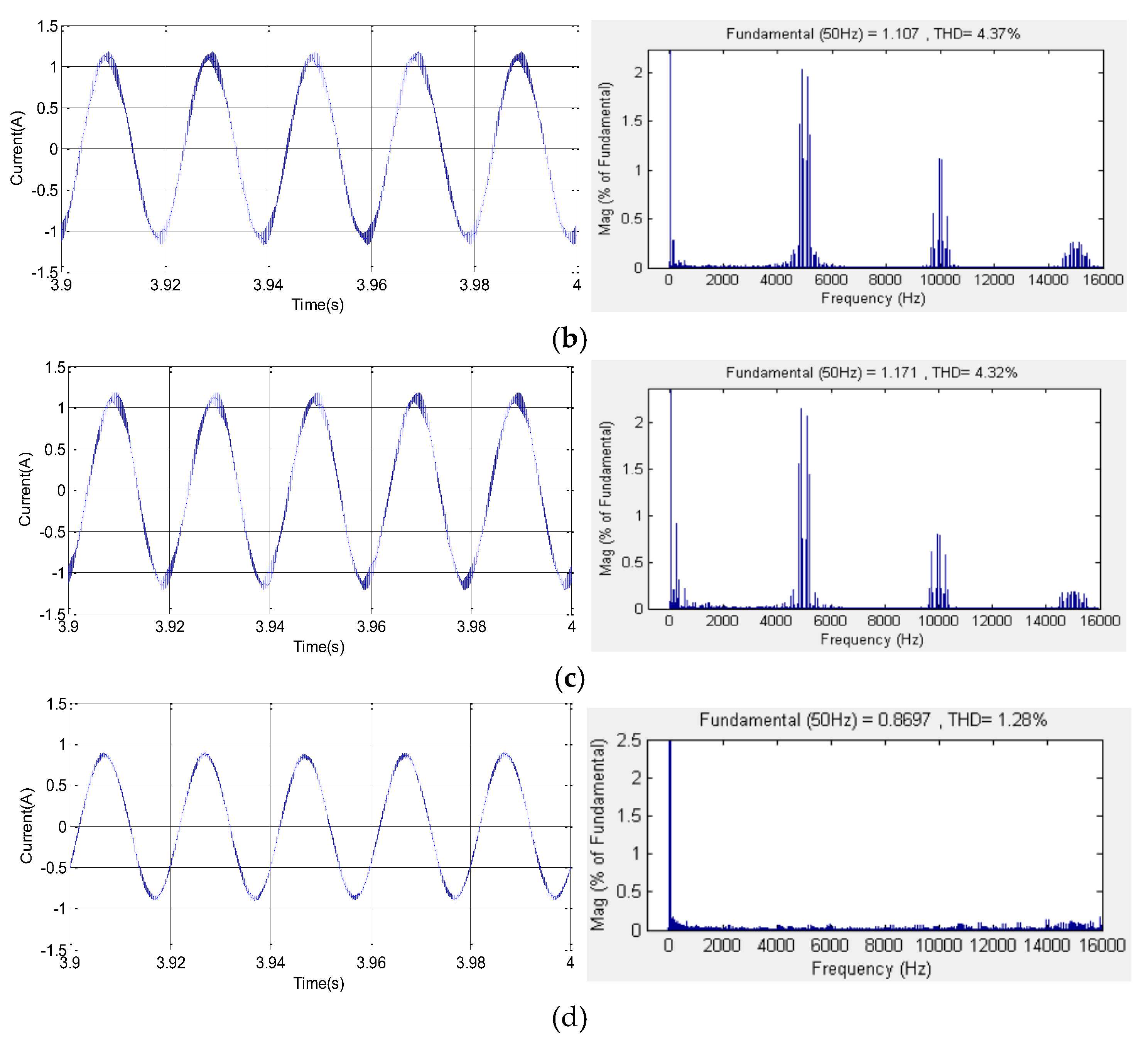

Next, the four proposed PWM controls are examined in terms of THD current and peaks harmonic dominant.

Figure 14 represent the variation according to the modulation index of the THD current, the peaks harmonic. It can be seen also that obtained results are influenced by the values of the modulation index. As illustrated in

Figure 14a, it is clearly seen that when the modulation index value increases, the THD level falls for all controls. Added to that, the current harmonic content of the RSFSVPWM is significantly reduced and lower compared to that other schemes. The fixed SVPWM produced a lower THD compared to the random RZVSVPWM and RPPSVPWM controls. Hence, as shown in

Figure 14b, the magnitude of current harmonic reduced significantly for the RSFSVPWM over the entire modulation range compared to that other schemes. In conclusion, the RSFSVPWM allows the most effective and robust in reducing the THD current and spreading the harmonic spectra, compared to the fixed SVPWM scheme and the random RZVSVPWM and RPPSVPWM.

5. Experimental Results

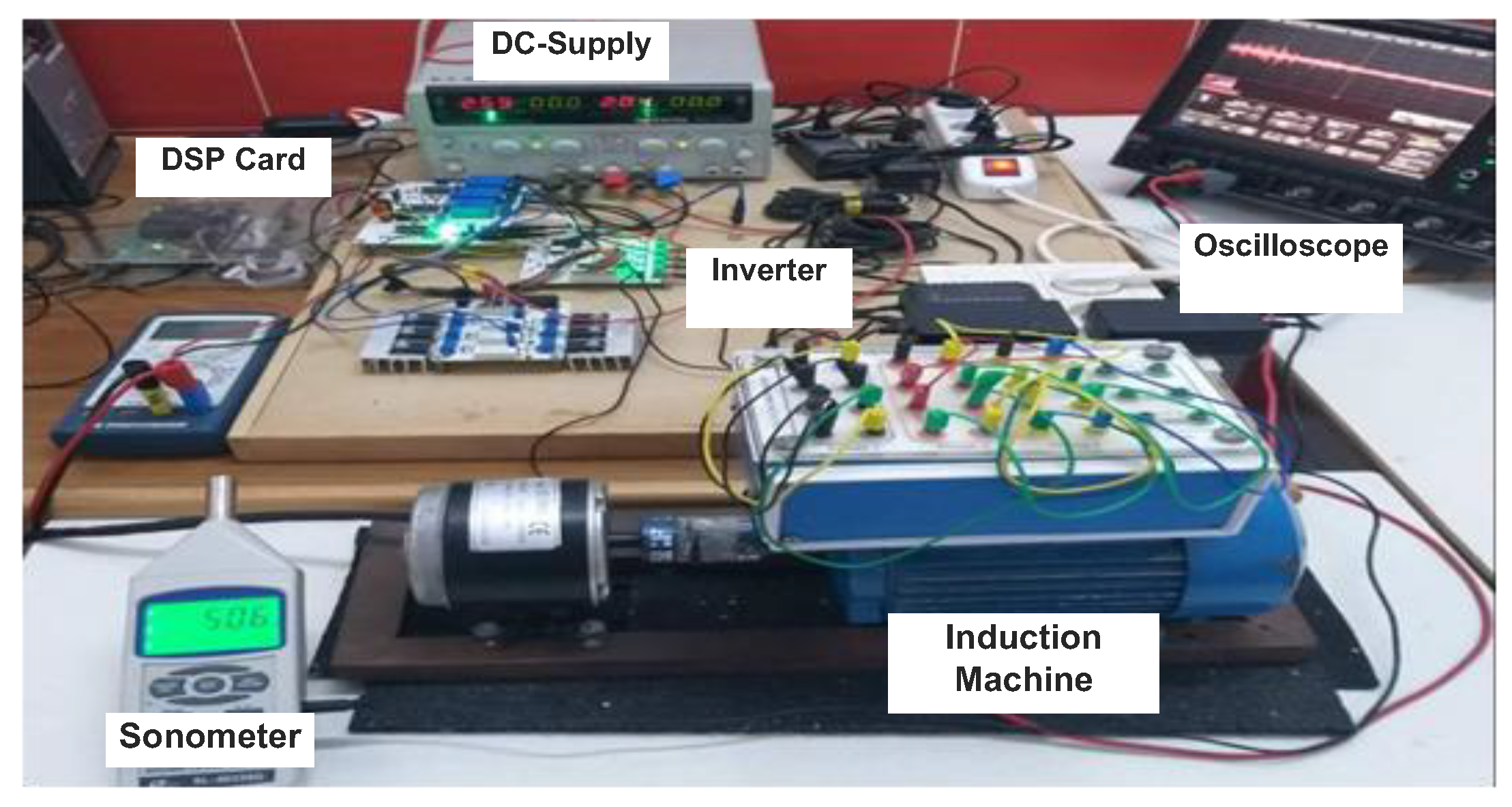

The photographic of the experimental system for acoustic noise measurements, is depicted in

Figure 15. It consists mainly of an IM, a DSP board and a two-level VSI controlled by SVPWM, RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RSFSVPWM respectively. We have implemented all the proposed strategies using the TMS320F28335 DSP board from the Texas Instruments. The motor runs at a fundamental frequency of F=50Hz and a switching frequency of Fc=5 KHz. A sound level meter is used to measure the instantaneous sound pressure. After each measurement test, the saved data file is transferred to the PC. The spectral noise analysis is performed using MATLAB’s FFT function. The machine used in this study is classified as a small machine. Therefore, all measurement points must be located at 250 mm distance or more from the main machine surface. Measurements should be carried out when the machine reaches a steady state of operating mode [

8,

22,

23,

24].

The sound pressure level in decibels(dB) can be described using the sound pressure, which is determined by equation (18):

where p0 is the reference sound pressure and, p(t) is the instantaneous sound.

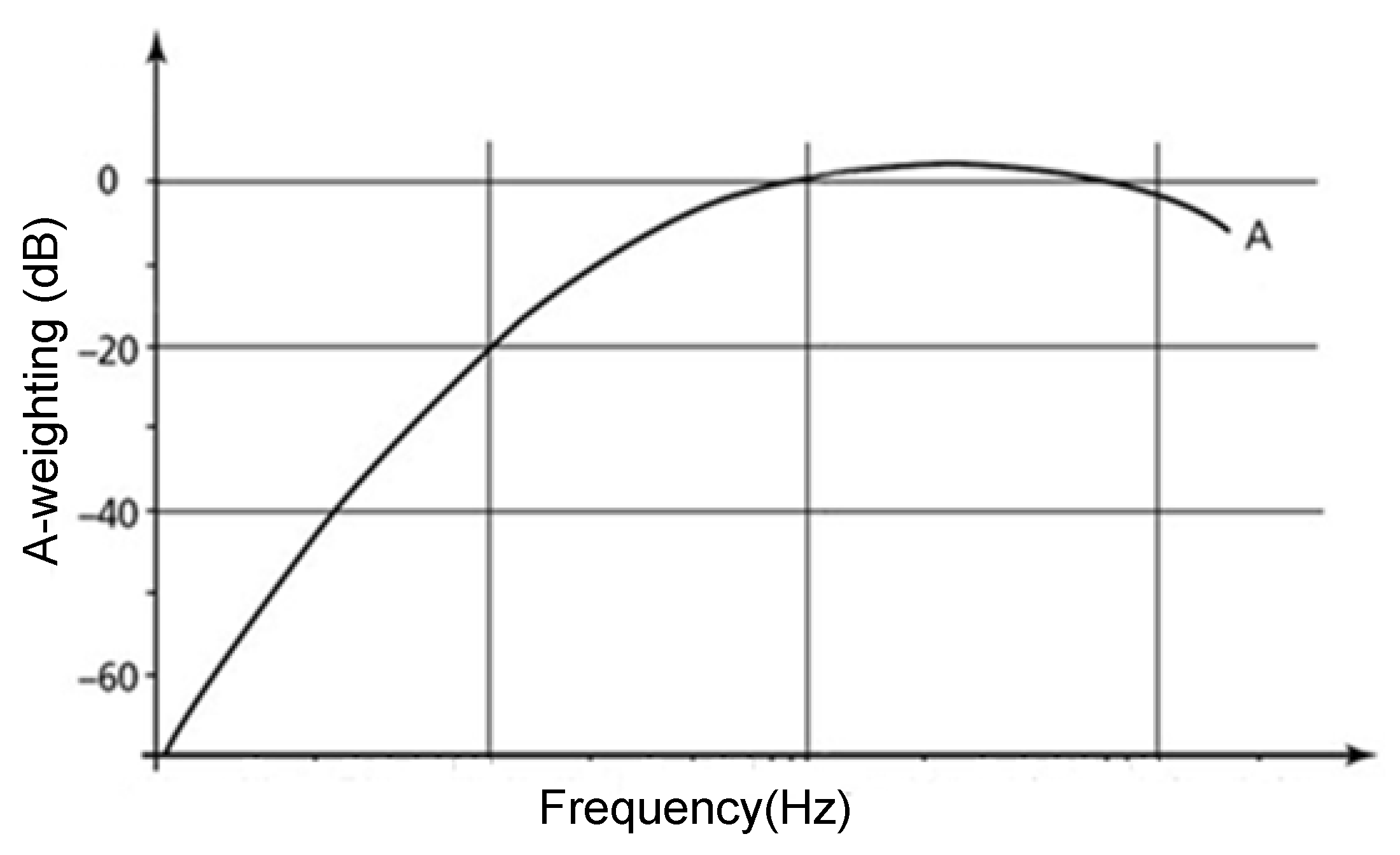

The human ear sensitivity can modelize using appropriate weighting functions or weighting curves. International standards recommend weighting curves. The A-weighting curve is widely used in electrical machine acoustics practice and is also used in this work.

Figure 16 illustrates the dB(A) weighting curve according to IEC 61672-1/2002 [

22].

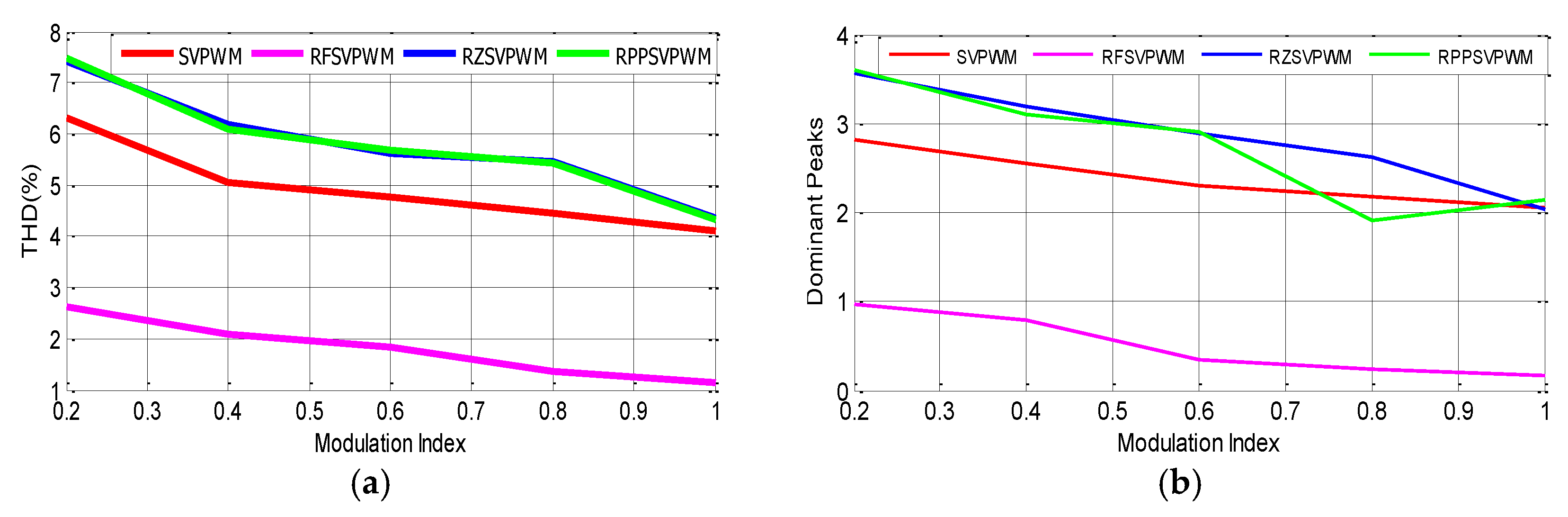

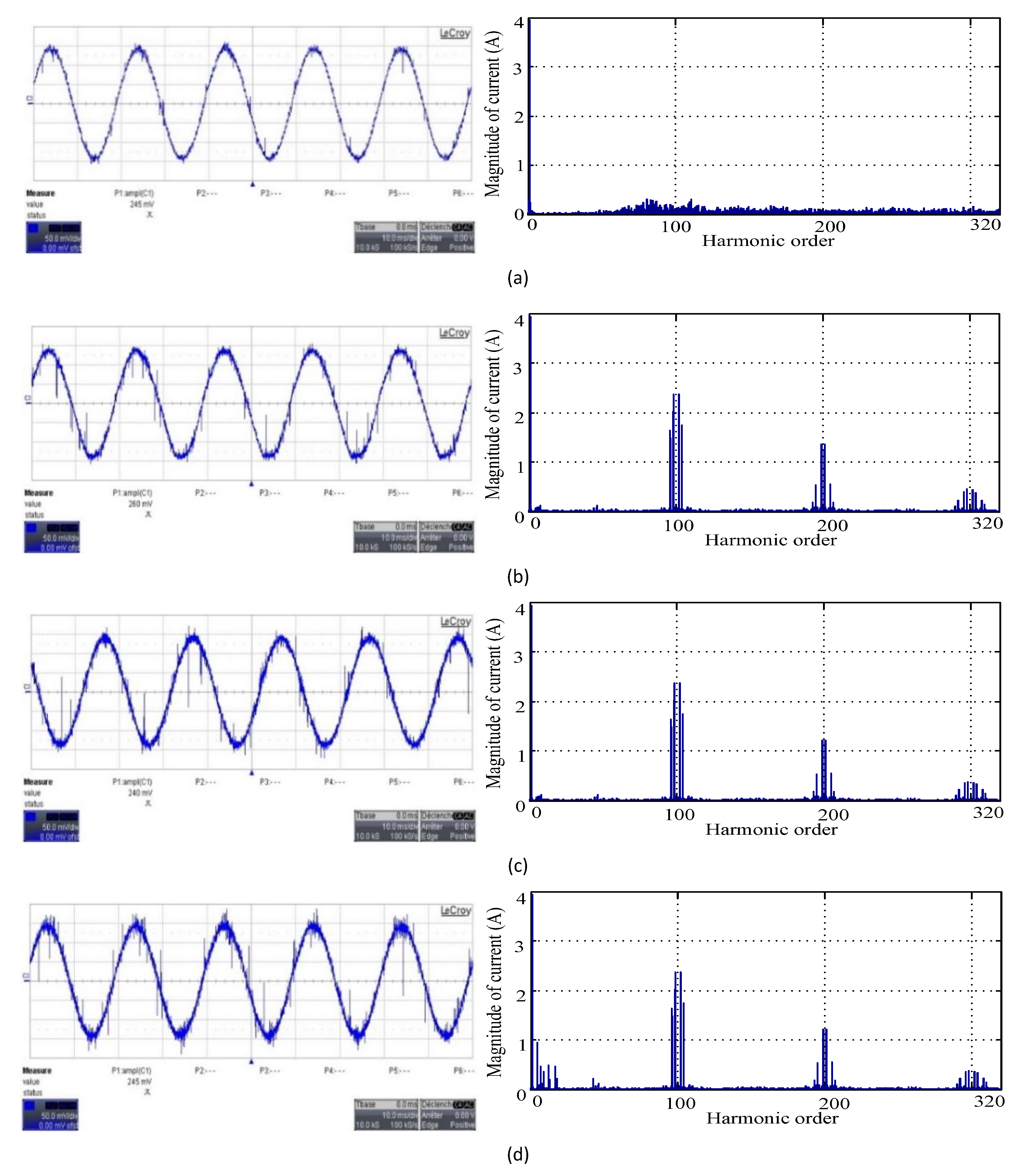

The measured stator current waveforms and the harmonic spectrum produced by the induction motor supply by a two-level VSI and controlled by the SVPWM, RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RSFSVPWM techniques pertaining to (im=1, Fc=5 KHz) are represented respectively in

Figure 17. On the other hand, as it can be seen from the results of the measured harmonic spectrum, with the SVPWM, RZVSVPWM and RPPSVPWM techniques, the dominant harmonics components are concentrated around the switching frequency and its multiples. Furthermore, the highest magnitudes of current harmonics are located around the first sideband of the switching frequency. Whereas, it can be observed that the magnitude of current harmonics is reduced considerably with RSFSVPWM compared to the other strategies. Furthermore, the motor current spectrum is well dispersed and the harmonics around integer multiples of the switching frequency disappear. As a consequence, it is evident the that proposed scheme RFSVPWM has a better performance in terms of acoustic noise as it will be seen in the next section.

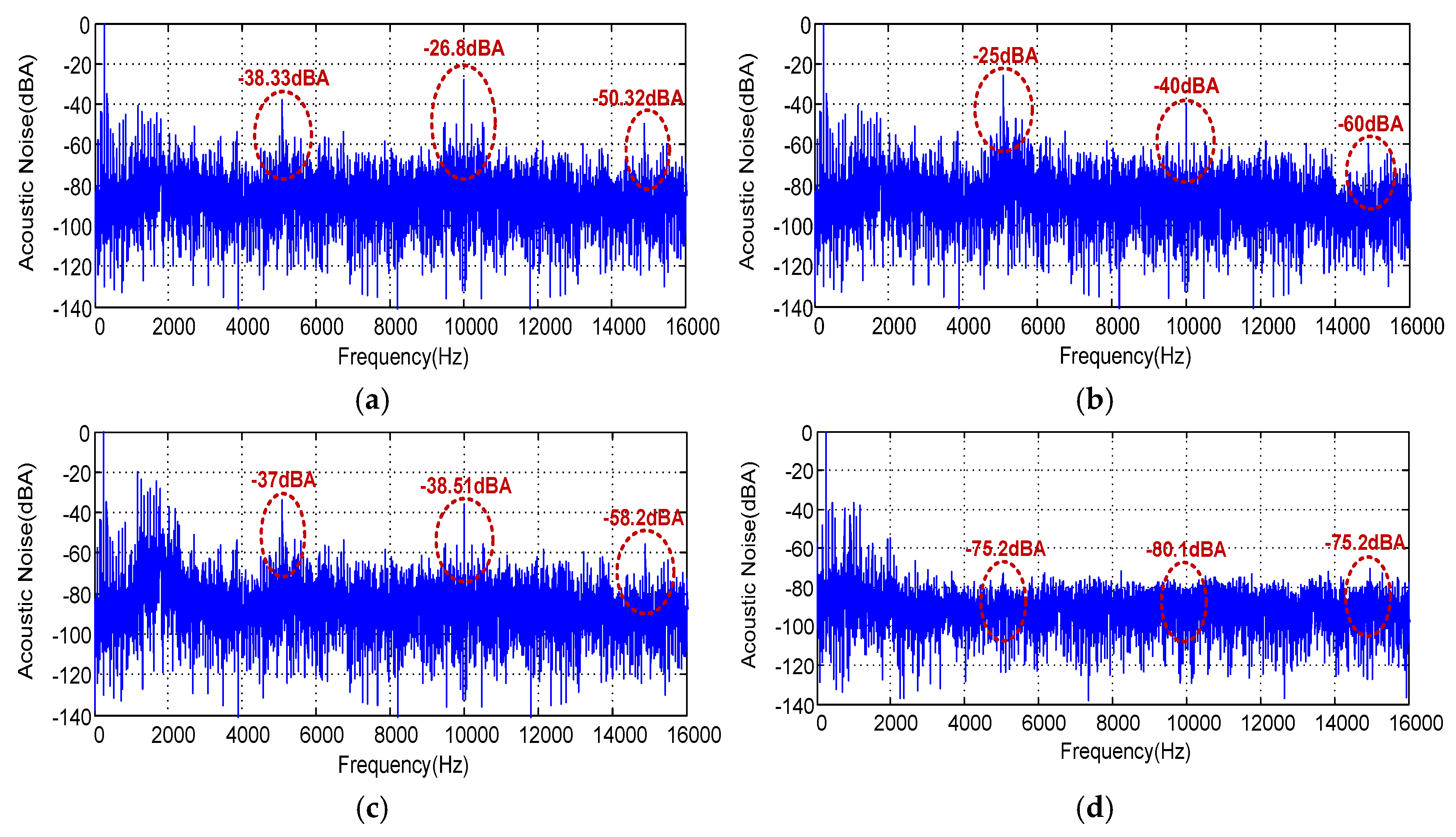

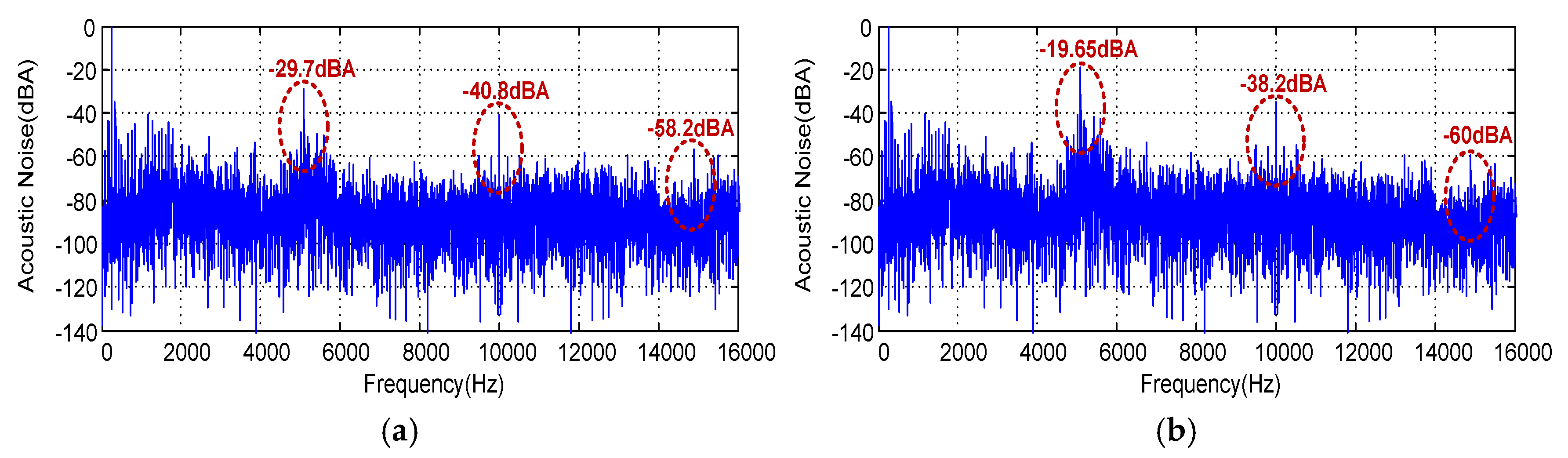

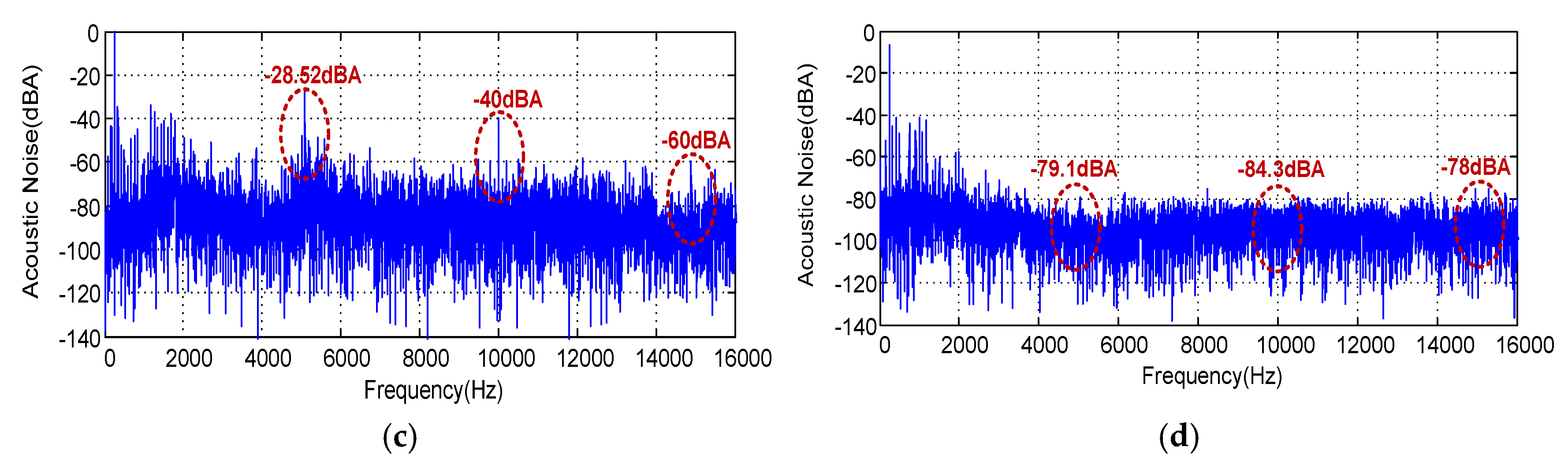

The weighted frequency spectra of acoustic noise corresponding to the SVPWM, RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RSFSVPWM techniques for (im = 0.8, Fc =5 KHz) and (im = 1, Fc =5 KHz) are performed and demonstrated respectively in

Figure 18 and

Figure 19. Referring to the experimental results, we can observe that the acoustic noise emitted from the induction motor are generated with SVPWM, RZVSVPWM and RPPSVPWM. The high acoustic noise components are significantly and more important around integer multiples of the switching frequency, as shown in

Figure 18a,

Figure 18b and

Figure 18c. The dominant noise of these techniques is mainly due to the interaction of the switching frequency and the higher time harmonics. Then, for im=0.8, the noise amplitude are (-38.33 dBA, -26.8 dBA, -50.32 dBA), (-25 dBA, -40 dBA, -60 dBA) and (-37 dBA, -38.51 dBA, -58.2 dBA) respectively, at 5Khz, , 10 KHz and 15 KHz for SVPWM, RZVSVPWM and RPPSVPWM respectively. However, for RFSVPWM technique, the dominant noise components emitted from the induction motor around integer multiples of the switching frequency disappear and spread spectrum, as presented in

Figure 18d. It is clearly noticed that random RSFSVPWM produces a less noise component than the other techniques. The noise amplitude is (-75.2 dBA, -80.1 dBA, -75.2 dBA) respectively, at 5Khz, 10 KHz and 15 KHz. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed RSFSVPWM scheme in reducing the acoustic noise emitted by induction motor.

The measured acoustic noise spectra for (im = 1, Fc =5 KHz) is presented in

Figure 19. The same observations are valid, here again, the acoustic noise emitted from the induction motor is totally spread, as seen from

Figure 19d for the RSFSVPWM technique. In addition, for index modulation im=1, the acoustic noise falls down for the four proposed PWM techniques. Then, the noise amplitude is (-29.7 dBA, -40.8 dBA, -58.2 dBA), (-19.65 dBA, -38.2 dBA, -60 dBA), (-28.52 dBA, -40 dBA, -60 dBA) and (-79.1 dBA, -84.3 dBA, -78 dBA) respectively, at 5Khz, 10 KHz and 15 KHz for SVPWM, RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RSFSVPWM respectively.

Table 2 shows a comparison of SVPWM, RPWM and RSFSVPWM techniques in terms of current THD (%), and acoustic noise level (dBA) emitted by induction machine. It should be remembered that for the RPWM technique developed in our previous study, the values for current and acoustic noise are 3.92% and -59.79 dBA respectively. Therefore, it is noted that the random RSFSVPWM technique has a lower THD and acoustic noise level than fixed SVPWM and the RPWM modulation.

6. Conclusion

This paper examines the impact of the Random Space Vector RSVPWM controls in terms of PWM acoustic noise emitted induction motor fed by for a three-phase two-level voltage source inverter. In addition, the fixed SVPWM, Random Switching Frequency Space Vector (RSFSVPWM), Random Zero Vector Space Vector (RZVSVPWM) and Random Pulse Position Space Vector (RPPSVPWM) are proposed and investigated theoretically and experimentally. The simulation results of the harmonic current show that with SVPWM, RPPSVPWM and RZVSVPWM, the harmonics components produced near the switching frequency and its multiples under different modulation indexes. Nevertheless, the harmonic spectrum of the proposed RFSVPWM is totally spread over the entire frequency band and the band around the switching frequency and its multiples are disappeared. The experimental validation of the studied control strategies is evaluated using a lab prototype of inverter -fed induction motor drive. The proposed random RSFSVPWM is able to provide a good performance in terms current quality (THD) and to reduce the acoustic noise VSI-fed motor drives compared to other random modulation RZVSVPWM, RPPSVPWM and to the fixed SVPWM.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IM |

Induction Machine |

| PWM |

Pulse Width Modulation |

| RSFSVPWM |

Random Switching Frequency Space Vector |

| RZVSVPWM |

Random Zero Vector Space Vector |

| RPPSVPWM |

Random Pulse Position Space Vector |

| SVPWM |

Space Vector PWM |

| VSI |

Voltage Source Inverter |

Appendix A

The machine parameters are mentioned in

Table A1.

Table A1.

Induction Machine Parameters.

Table A1.

Induction Machine Parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

Rated power

Motor speed

Stator resistance

Stator inductance

Rotor Resistance

Rotor inductance

Mutual inductance

Friction coefficient

Inertia Moment

Pair pole number |

0.5Kw

3000 tr/min

24 Ω

0.66H

10.88 Ω

0.66H

0.63 H

0.00159

0.004Kg.m2

1 |

References

- Wu, B.; Qiao, M. A review of the research progress of motor vibration and noise. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems. 2022, 2022, 5897198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P.; Buigues, G.; Mazon, A.J. Noise in electric motors: A comprehensive review. Energies. 2023, 16, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayraghavan, P.; Krishnan, R. Noise in electric machines: A review. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications. 1999, 35, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binojkumar, C.; Saritha, B.; Narayanan, G. Acoustic Noise Characterization of Space Vector Modulated Induction Motor Drives–An Experimental Approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 3362–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Wang, D.; Wang, C.; Miao, W.; Wang, X. Analytical Approach and Experimental Validation of Sideband Electromagnetic Vibration and Noise in PMSM Drive With Voltage-Source Inverter by SVPWM Technique. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Binojkumar, A. C.; Prasad, J. S.; Narayanan, G. Experimental investigation on the effect of advanced bus-clamping pulsewidth modulation on motor acoustic noise. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 2012, 60, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zou, J. Hybrid RPWM technique based on modified SVPWM to reduce the PWM acoustic noise. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 2018, 34, 5667–5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahi, H.; Ben Smida, K.; Khedher, A. Experimental study of PWM strategy effect on acoustic noise generated by inverter-fed induction machine. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems. 2020, 30, e12249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. B.; Narayanan, G. Variable-switching frequency PWM technique for induction motor drive to spread acoustic noise spectrum with reduced current ripple. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications. 2016, 52, 3927–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouda, A.; Boudjerda, N.; Aibeche, A. dSPACE-based dual randomized pulse width modulation for acoustic noise mitigation in induction motor. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering. 2022, 44, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamoudi, R.; Chariag, D. E.; Sbita, L. A review of spread-spectrum-based PWM techniques—A novel fast digital implementation. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 2018, 33, 10292–10307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Preindl, M. Variable Switching Frequency Techniques for Power Converters: Review and Future Trends. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronic. 2023, 38, 15603–15619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhu, W.; Nie, Z. Performance and Characterization of Optimal Harmonic Dispersion Effect in Double FrequencyBand Random PWM Strategy. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 2024.

- Jadeja, R.; Ved, A. D.; Chauhan, S. K.; Trivedi, T. A random carrier frequency PWM technique with a narrowband for a grid-connected solar inverter. Electrical Engineering. 2020, 102, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Song, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y. A variable switching frequency space vector pulse width modulation control strategy of induction motor drive system with torque ripple prediction. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion. 2023, 38, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, G.; Guo, Y. A Variable Switching Frequency Space Vector Pulsewidth Modulation Technique Using Virtual Flux Ripple. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics. 2022, 11, 2051–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Cheng, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Ji, P.; Yang, J. An Optimization Method in the Random Switching Frequency SVPWM for the Sideband Harmonic Dispersion. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ayano, H.; Kitada, M.; Iguchi, Y.; Matsui, Y.; Itoh, J. I. Novel modulation technique to reduce acoustic noise and switching loss. Electrical Engineering in Japan. 2021, 214, e23305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayano, H.; Nakagaki, T.; Iguchi, Y.; Matsui, Y.; Itoh, J. I. Theoretical study of rampwise DPWM technique to reduce motor acoustic noise. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 2023, 38, 8102–8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, W.; Ge, Y.; Wheeler, P. A Markov Chain Random Asymmetrical SVPWM Method to Suppress High-Frequency Harmonics of Output Current in an IMC-PMSM System. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 2023, 39, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, K.; Shao, X.; Liu, J. Chaotic ant colony algorithm-based frequency-optimized random switching frequency SVPWM control strategy. Journal of Power Electronics. 2023, 23, 1688–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieras, J. F.; Wang, C.; Lai, J. C. Noise of polyphase electric motors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lisner, R. P.; Timar, P. L. A new approach to electric motor acoustic noise standards and test procedures. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion. 1999, 14, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Narayanan, G. A low-cost system for measurement and spectral analysis of motor acoustic noise. In Proceedings of the 5th National Power Electronics Conference (NPEC), Howrah, India, 19-22 December 2001; pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Noise generation in electrical machine and different noise sources .

Figure 1.

Noise generation in electrical machine and different noise sources .

Figure 2.

Waveform of output voltage and its FFT.

Figure 2.

Waveform of output voltage and its FFT.

Figure 3.

Principal radial deformation modes of the stator and geometry of stator ring and teeth.

Figure 3.

Principal radial deformation modes of the stator and geometry of stator ring and teeth.

Figure 4.

(a) Structure of IM fed by VSI, (b) Space vector diagram.

Figure 4.

(a) Structure of IM fed by VSI, (b) Space vector diagram.

Figure 5.

Switching state distribution at sector 1 for the SVPWM control.

Figure 5.

Switching state distribution at sector 1 for the SVPWM control.

Figure 6.

Parameters of switching signal for VSI three phase.

Figure 6.

Parameters of switching signal for VSI three phase.

Figure 7.

Switching state distribution at sector 1 for RZVSVPWM control.

Figure 7.

Switching state distribution at sector 1 for RZVSVPWM control.

Figure 8.

Switching state distribution at sector 1 for RPPSVPWM control.

Figure 8.

Switching state distribution at sector 1 for RPPSVPWM control.

Figure 9.

Switching state at sector 1 for the RSFSVPWM control.

Figure 9.

Switching state at sector 1 for the RSFSVPWM control.

Figure 10.

Waveforms for two-level VSI of Switch S11 using: (a) SVPWM and (b) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 10.

Waveforms for two-level VSI of Switch S11 using: (a) SVPWM and (b) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 11.

Numerical simulation results of different carrier waveforms and the FFT analysis for the RSFSVPWM control with (a) RT =0.5, (b) RT =0.3 and (c) RT = 0.1. .

Figure 11.

Numerical simulation results of different carrier waveforms and the FFT analysis for the RSFSVPWM control with (a) RT =0.5, (b) RT =0.3 and (c) RT = 0.1. .

Figure 12.

Stator current waveforms and their harmonic spectrum at im=0.8, Fc=5Khz for: (a) SVPWM, (b) RZVSVPWM, (c) RPPSVPWM and (d) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 12.

Stator current waveforms and their harmonic spectrum at im=0.8, Fc=5Khz for: (a) SVPWM, (b) RZVSVPWM, (c) RPPSVPWM and (d) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 13.

Stator current waveforms and their harmonic spectrum at im=1, Fc=5Khz for: (a) SVPWM, (b) RZVSVPWM, (c) RPPSVPWM and (d) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 13.

Stator current waveforms and their harmonic spectrum at im=1, Fc=5Khz for: (a) SVPWM, (b) RZVSVPWM, (c) RPPSVPWM and (d) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 14.

Variation according to modulation index of : (a) THD current and (b) Dominant peaks.

Figure 14.

Variation according to modulation index of : (a) THD current and (b) Dominant peaks.

Figure 15.

Photo of experimental platform.

Figure 15.

Photo of experimental platform.

Figure 16.

A-weighting curve according to IEC 61672-1/2002.

Figure 16.

A-weighting curve according to IEC 61672-1/2002.

Figure 16.

Stator current waveforms and harmonic spectrum for (a) RSFSVPWM, (b) SVPWM, (c) RZSVPWM and (d) RPPSVPWM.

Figure 16.

Stator current waveforms and harmonic spectrum for (a) RSFSVPWM, (b) SVPWM, (c) RZSVPWM and (d) RPPSVPWM.

Figure 18.

Acoustic noise spectrum at im=0.8, Fc=5Khz for : SVPWM, (b) RZVSVPWM, (c) RPPSVPWM and (d) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 18.

Acoustic noise spectrum at im=0.8, Fc=5Khz for : SVPWM, (b) RZVSVPWM, (c) RPPSVPWM and (d) RSFSVPWM.

Figure 19.

Acoustic noise spectrum at im=0.8, Fc=5Khz for: (a) RSFSVPWM, (b) SVPWM, (c) RZSVPWM and (d) RPPSVPWM.

Figure 19.

Acoustic noise spectrum at im=0.8, Fc=5Khz for: (a) RSFSVPWM, (b) SVPWM, (c) RZSVPWM and (d) RPPSVPWM.

Table 2.

Comparison of SVPWM, RPWM and RSFSVPWM techniques.

Table 2.

Comparison of SVPWM, RPWM and RSFSVPWM techniques.

| |

SVPWM |

RPWM |

RSFSVPWM |

|

THD Current(%)

|

4.87 |

3.92 |

1.49 |

|

Acoustic noise (dBA)

|

-29.7 |

-59.79 |

-79.1 |

|

Frequency

|

Fixed |

Random |

Random |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

and hc is the stator thickness.

and hc is the stator thickness.