1. Introduction

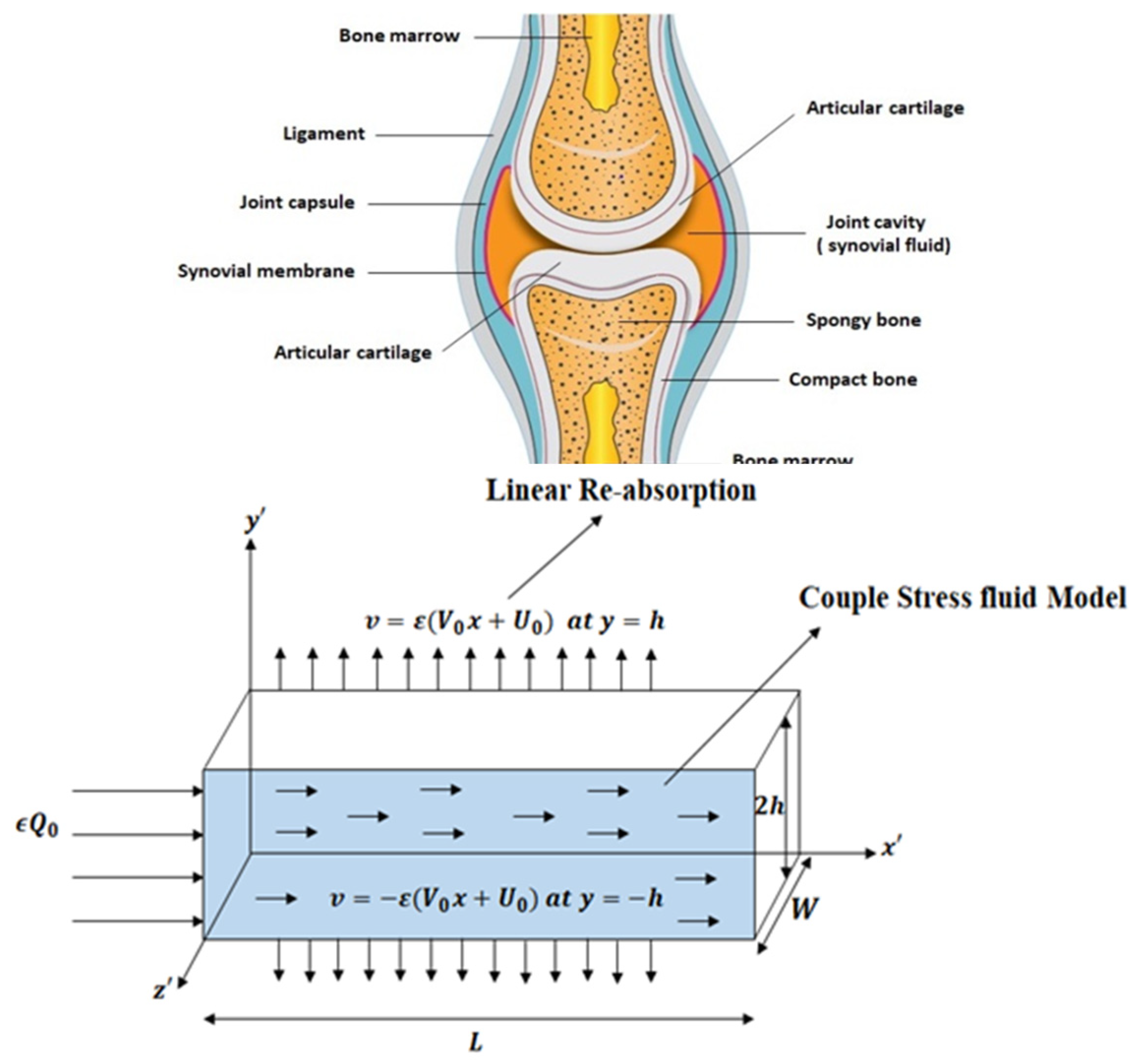

The aim of this research is to analyze the flow of synovial fluid (SF) through the synovium in knee joint. SF plays a crucial role in joint lubrication, reducing cartilage friction for smooth movement. It is located near the synovial membrane (SM), which consists of collagens, proteins, and proteoglycans—key components influencing SF viscosity. The selectively permeable SM allows the absorption and secretion of SF, regulating water balance to prevent joint swelling (effusion) or inadequate lubrication, which may lead to joint damage.

Several studies have examined SF flow characteristics. Yin et al. [

1] highlighted the complexity of SF as a filtrate of interstitial fluids. Lai et al. [

2] noted that SF flow depends on shear stress and deformation rate, but no single fluid model accurately describes its rheology. Ouerfelli et al. [

3] emphasized the role of hyaluronic acid (HA) in joint lubrication, where SF behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid, shifting to Newtonian behavior after hyaluronidase treatment in osteoarthritis. Singh et al. [

4] explored SF analysis for arthritis treatment, while Hasnain et al. [

5] modeled SF as a power-law fluid incorporating permeability and magnetic field effects. Maqbool et al. [

6,

7] analyzed SF flow through permeable conduits using the Linear Phan-Thien-Tanner (LPTT) model and found that periodic filtration influences pressure and velocity distribution. The viscosity of SF is determined by HA molecular size and concentration, and its long-chain molecules can be modeled as a polar fluid. Rumanian et al. [

8,

9] used the couple-stress fluid model to study the hydrodynamic lubrication, noting the presence of couple stresses in fluids with large molecular structures. Previous studies [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,] analyzed couple-stress effects in various flow conditions but did not consider SF as a couple-stress fluid.

Inertial (non-creeping) flow occurs at high shear rates during activities like running and jumping which facilitates nutrient exchange and fluid circulation in the joint. For the healthy synovial fluid properties and consistent joint motion, nutrients re-absorption in synovial fluid follow the linear trajectory. This linear behavior is typically observed in a well-lubricated joint environment where the biomechanical load and fluid dynamics are favorable. Several researchers [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

2122] have examined the impact of exercise on SF composition and joint performance. Oates [

23] observed inertial forces in sudden joint movements, while Mow [

24] explored bio-mechanical factors affecting joint health. Hron et al. [

25] and Ruggior [

26] studied inertial effects on SF flow in one dimension, but no one has examined it in a two-dimensional rectangular permeable synovium under slip and linear re-absorption effect, which is the novelty of this study.

This research uniquely analyzes SF as a couple-stress fluid under inertial effects through a permeable membrane with linear re-absorption. Unlike prior studies that primarily considered creeping flows and ignored membrane permeability but this research has considered the ignored inertial and linear re-absorption effects. The mathematical model is computed by employing a recursive and inverse approach to find the flow properties under constant flux at the entrance. The findings will assist biomedical engineers in calculating SF forces and flow properties under dynamic conditions which are essential for designing the artificial joint and surgical techniques.

The research is structured as follows:

Section 1 reviews the literature and identifies research gaps,

Section 2 models SF flow using mechanical laws,

Section 3 applies recursive and inverse methods to solve the problem,

Section 4 presents graphical results for flow speed, load, and shear stress, and Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Material and Method

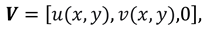

A planar geometry is taken into consideration when creating the scientific model of synovial fluid flow via a knee joint. The two-dimensional cross-sectional area of a slit represents the flow regime of synovial fluid, while the permeable wall of the slit resembles the synovial membrane and couple stress fluid is thought to be a synovial fluid due to micro-rotational effects. It is assumed that the slit is L in length along the x-axis, W in width along the z-axis, and H in height along the y-axis. It is also assumed that the re-absorption rate of nutrients and liquid available in synovial fluid is linear due to healthy synovial fluid properties in the synovial membrane and the flow is symmetric about the center line at y = 0.

Figure 1.

Geometry of the synovial fluid flow in knee joint.

Figure 1.

Geometry of the synovial fluid flow in knee joint.

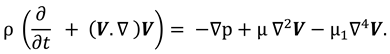

The movement of synovial fluid in knee joint suggests the following velocity field:

where

and

are flow velocity along and across the slit respectively.

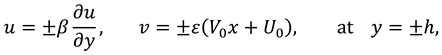

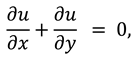

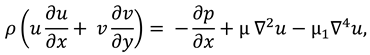

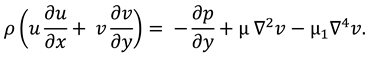

The synovial fluid flow can be described by the following continuity equation for in-compressible flow and momentum equation for the steady couple stress fluid flow:

where

is the hydrostatic pressure of the fluid,

μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid and

is the material constant associated with couple-stress fluid.

The slip velocity and linear re-absorption rate at the synovial membrane suggest the following conditions:

where

and

are re-absorption velocity parameters.

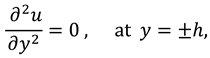

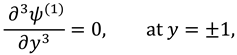

The vanishing of couple stress due to ir-rotational movement of the fluid particles at walls suggests the following condition:

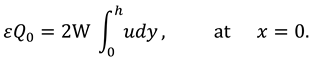

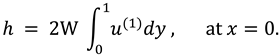

The synovial fluid enters in the flow regime with a constant flow rate and satisfy the following condition at the entry point

x=0.

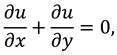

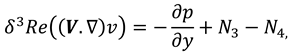

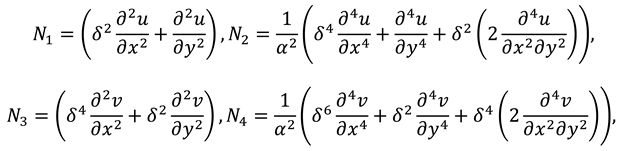

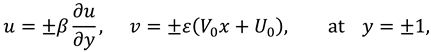

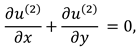

For two-dimensional inertial flow, the component form of continuity and momentum equations are as follows:

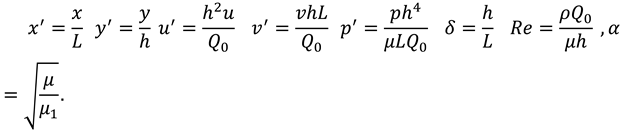

2.1. Non-Dimensional Quantities

The non-dimensional quantities are defined as follows:

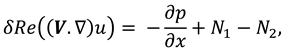

Using above quantities in Equations (5)-(7), and ignoring primes one can write the following equations:

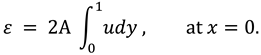

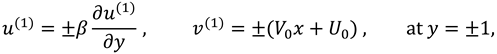

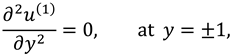

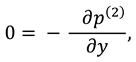

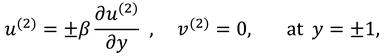

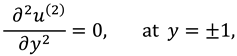

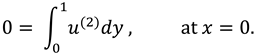

The dimensionless form of the boundary conditions will take the following form:

Where

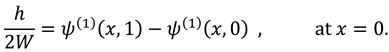

2.2. Solution Methodology

To find the results for the flow rate, normal and tangential forces in synovial fluid, we will solve the mathematical model given in Eqs. (9)-(11). The mathematical model presents the set of non-linear partial differential equations in . The length of synovial membrane (slit) is smaller than its width that make the complex mathematical problem in simple form assume that the ratio of length to width ( is very small and we will ignore the terms of order .

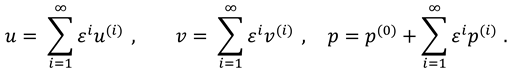

To find the results for u

following recursive approach is used:

where

is a constant.

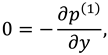

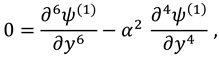

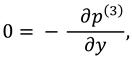

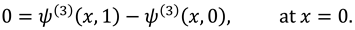

Now by substituting the above mention series in Eqs. (9)-(12) and then by collecting the powers of ε, one can get the following systems:

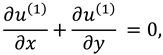

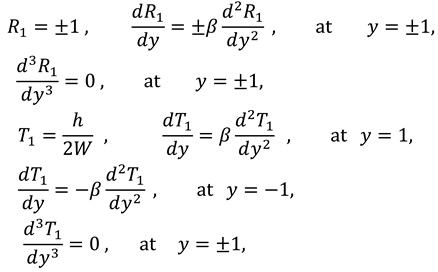

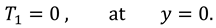

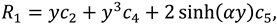

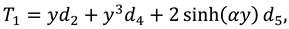

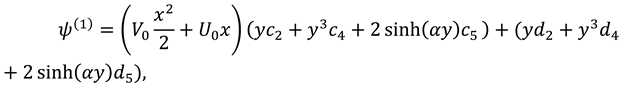

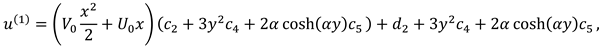

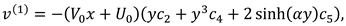

2.2.1. First Order System and It’s Solution

The associated boundary conditions for first order system are defined as follows:

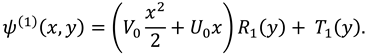

To reduce the number of unknowns one can, introduce the following stream function

:

After replacing

and

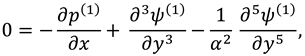

in Equations (14)-(17), one can get following equations:

Differentiating equations (19) and (20) with respect to

y and

x , then by subtracting them the pressure term is eliminated and the resulting equation contains only the stream function and shown as below:

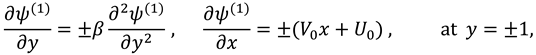

And boundary conditions in connection with stream function are defined as follow:

Assuming the solution of

in the following form as suggested in Inverse method:

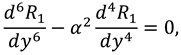

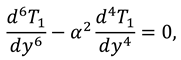

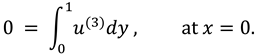

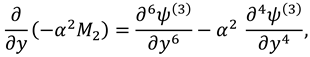

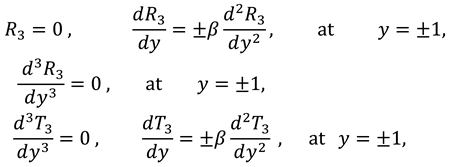

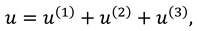

Upon using the above equation, one can get the following system of BVP:

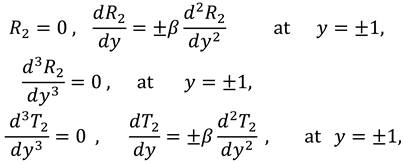

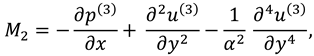

and the boundary conditions associated to the above system of equations are as follows:

Solutions of sixth order linear homogeneous ordinary differential equations together with above boundary conditions are defined as follows:

Where

.

Using above solutions of

and

in Eq. (23), following form of stream function can be obtained:

From the above stream function and Eq. (18), following velocity components can be obtained:

Where are defined in appendix.

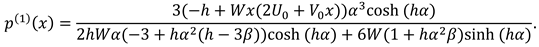

Using first order velocity components in first order momentum equation, one can find the following expression of first order pressure:

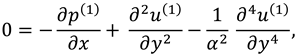

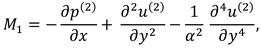

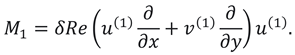

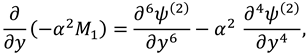

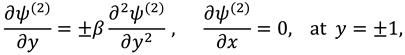

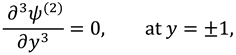

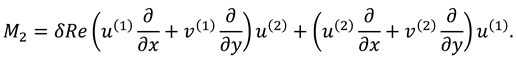

2.2.2. Second Order System and It’s Solution

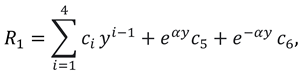

The associated boundary conditions for second order system are defined as follows:

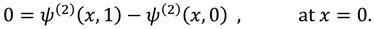

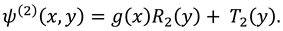

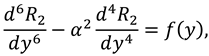

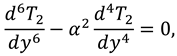

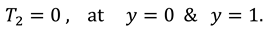

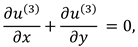

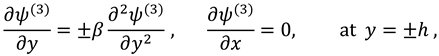

After eliminating the pressure gradient and using the relation of stream function with velocity components one can get the following equation:

With the following boundary conditions:

Assuming the solution of

as follows:

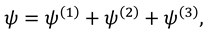

Using above stream function in Eq. (39-40), following system of differential equations can be obtained:

Where are given in appendix.

Boundary conditions associated to the above system of equations are as follows:

Solution of above BVP’s is obtained by DSolve command in MATHEMATICA.

Using solutions of these two BVP’s into assumed solution of stream function we have found 2nd order velocity components and using 2nd order velocity components into 2nd order system one can find expression for 2nd order pressure.

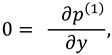

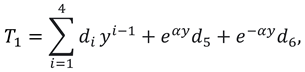

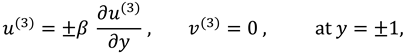

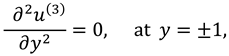

2.2.3. Third Order System and Its Solution

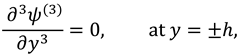

The associated boundary conditions for third order system are as follows:

After eliminating pressure and reducing unknowns, by introducing stream function

following equation can be obtained

And the boundary conditions in connection with stream function are as follows:

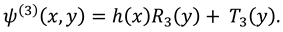

To solve above boundary value problem by inverse method one can assume the following stream function:

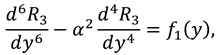

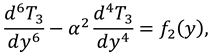

Using this assumption in above equations, we get the following systems of BVP’s:

Where can be calculated with the help of MATHEMATICA.

Boundary conditions associated to the above system of equations are as follows:

Solution of above BVP’s can be obtained by DSolve command in MATHEMATICA.

Using solutions of above two BVP’s into assumed solution of stream function one can find expressions for third order velocity components and using third order velocity components into third order momentum equation one can find expression for third order pressure.

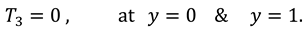

After combining first, second and third order solutions one can find expressions of stream function, velocity components, and pressure:

Where

Special Cases:

- a)

The present study reduces into the inertial flow of Newtonian fluid when,

, which has been discussed by Panek et al [

27].

- b)

When

and

the present model reduces into creeping flow of Newtonian fluid through a permeable channel with linear re-absorption that has been discussed by Haroon et al. [

28].

- c)

The creeping flow of couple stress fluid flow with constant re-absorption at the wall of the channel has been recently presented by Siddiqui et al. [

29] that can be deduce from the present study when,

and

.

3. Discussion on Graphical Results

Here the graphical analysis is discussed in order to study the influence of Reynolds number slip parameter , re-absorption parameters and the couple-stress parameter on the pressure, horizontal and vertical velocity components at (middle point of the slit). We have chosen this position on the axis of the slit so that mean flow of the couple-stress fluid can easily be observed for the re-absorption analysis.

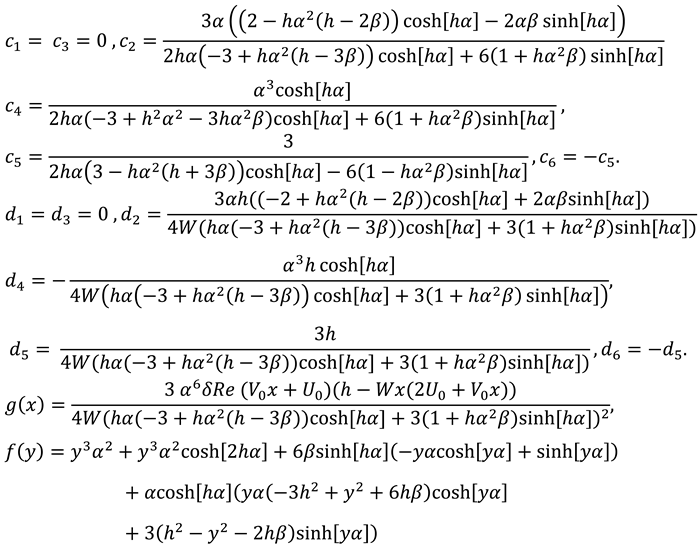

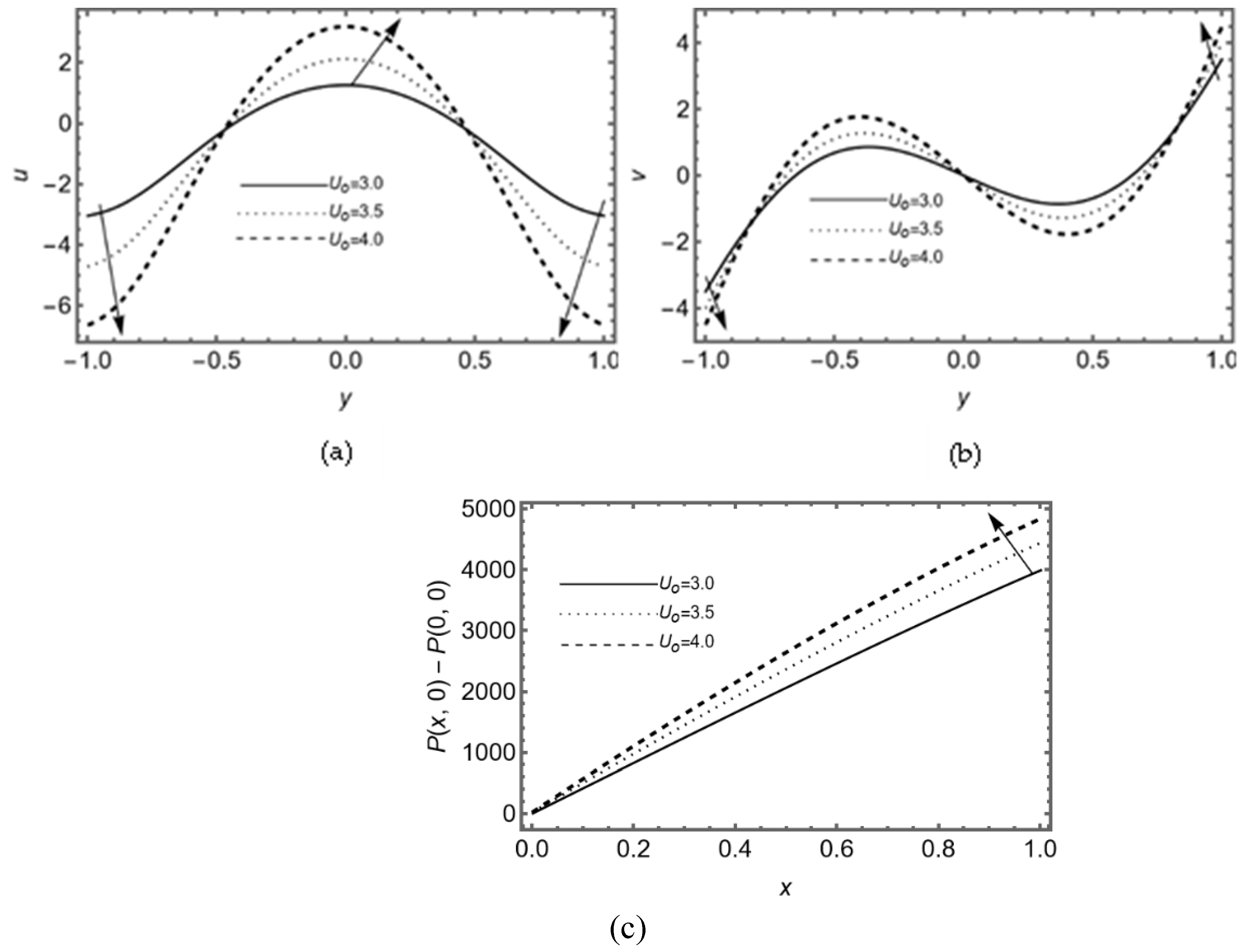

3.1. Effect of Reynold’s Number

Figure 2. (a-b) display the impact of inertial forces at the middle region of the slit that appears due to Reynold’s number. This figure analyzes that axial flow is maximum at the center of the slit due to the presence of pressure gradient. The graphs also show that flow in vertical direction rises during activity (due to non-zero Reynolds number). It also demonstrates the sharp rise in vertical velocity near the wall of the slit due to linear re-absorption in the synovium .

Figure 2c shows that pressure difference becomes more intense during activity (in the presence of Reynold’s number) also it raises rapidly near the exit region. Essentially, it indicates that during the flow of synovial fluid in synovial membrane, inertial forces take supremacy over viscous forces.

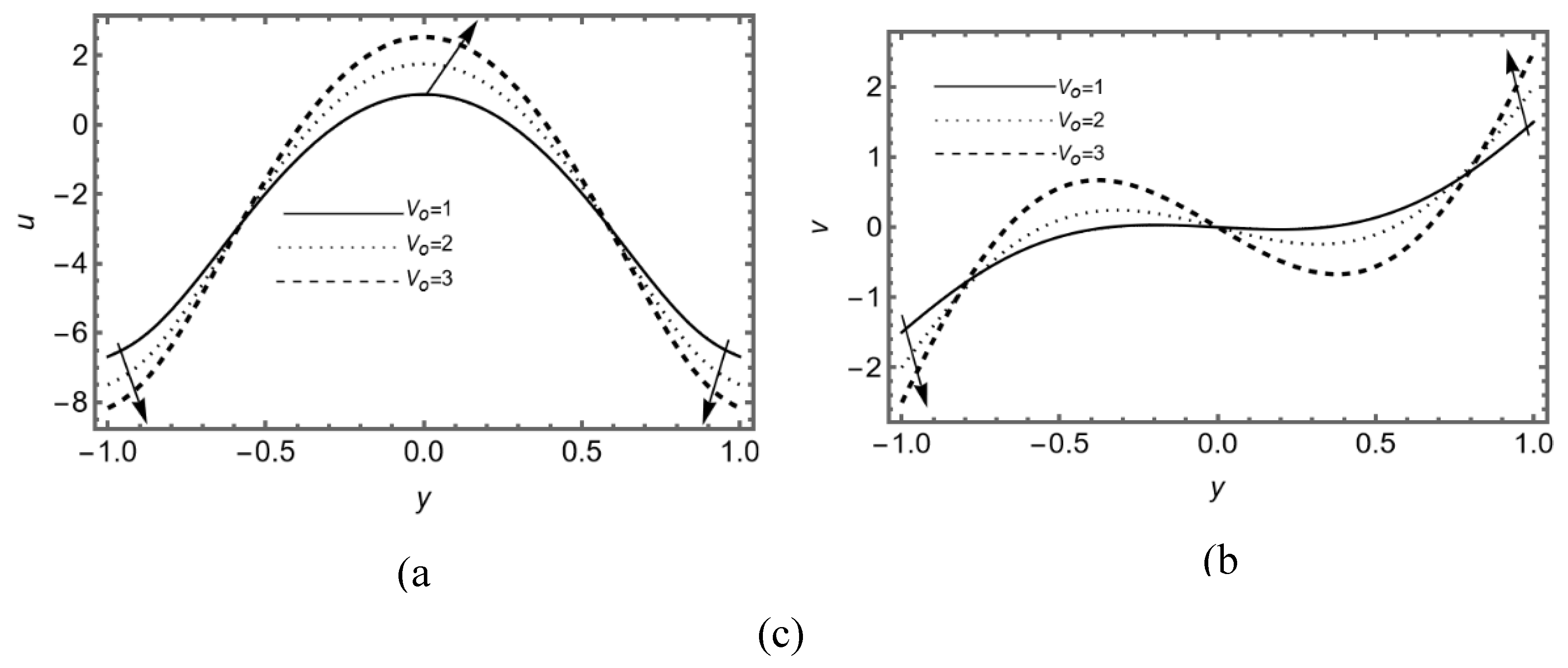

3.2. Effect of Re-Absorption Velocity

Figure 3 (a-b) shows the impact of permeability of membrane on the SF flow, this figure portrays the increasing effect of permeability on axial and transverse flow near the membrane. This graph indicates that the linear re-absorption causes an increase in axial and transverse flow due to the lubricated membrane, but the vertical flow rises in forward and for the upper and lower region.

Figure 3c presents the effect of linear re-absorption

on pressure difference and display the rising impact on pressure distribution.

Figure 4(a-b) displays the variation in axial and transverse velocity against the constant rate of re-absorption, it shows that flow of synovial fluid along and transverse to the SM rises due to appropriate viscosity of the synovial fluid.

Figure 4c displays that the pressure difference between the two points in the synovial fluid flow rises when nutrients are re-absorbed at constant rate in synovial fluid.

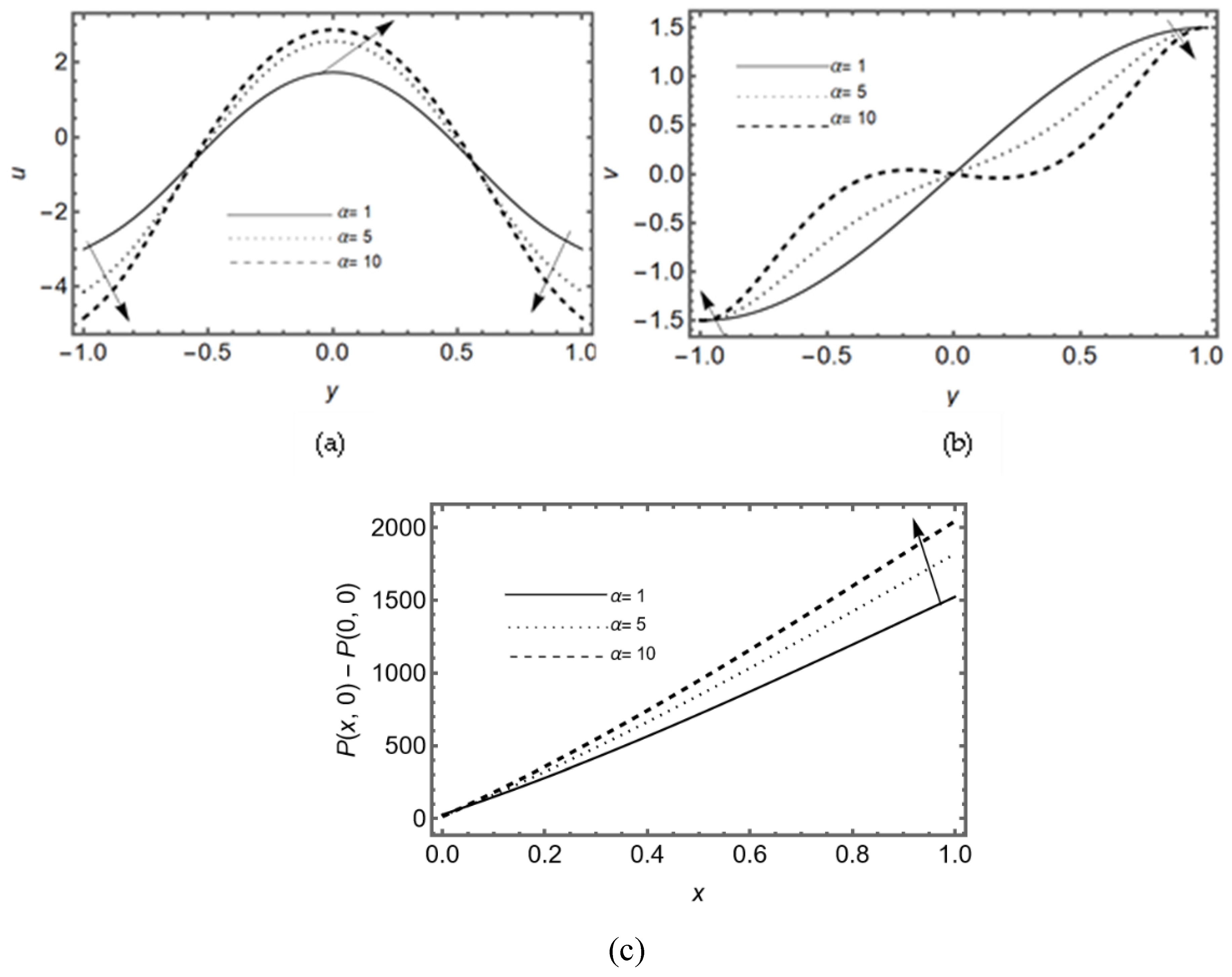

3.3. Effect of Couple-Stress Parameter α

Figure 5 (a-b) display that the velocity in a horizontal direction rises for different couple-stress parameter (α) at the middle of the slit but the transverse velocity decay by the rising values of couple stress parameter. Furthermore, it is seen that axial velocity increases at the center of the slit and decreases near the walls due to lubricated permeable membrane. The pressure difference on the slit is shown in

Figure 5c for various values of α which rises by the couple stress parameter, it shows the rotation of fluid particles helps to flow the fluid and more pressure in synovial fluid is required in case of lubricated permeable slit.

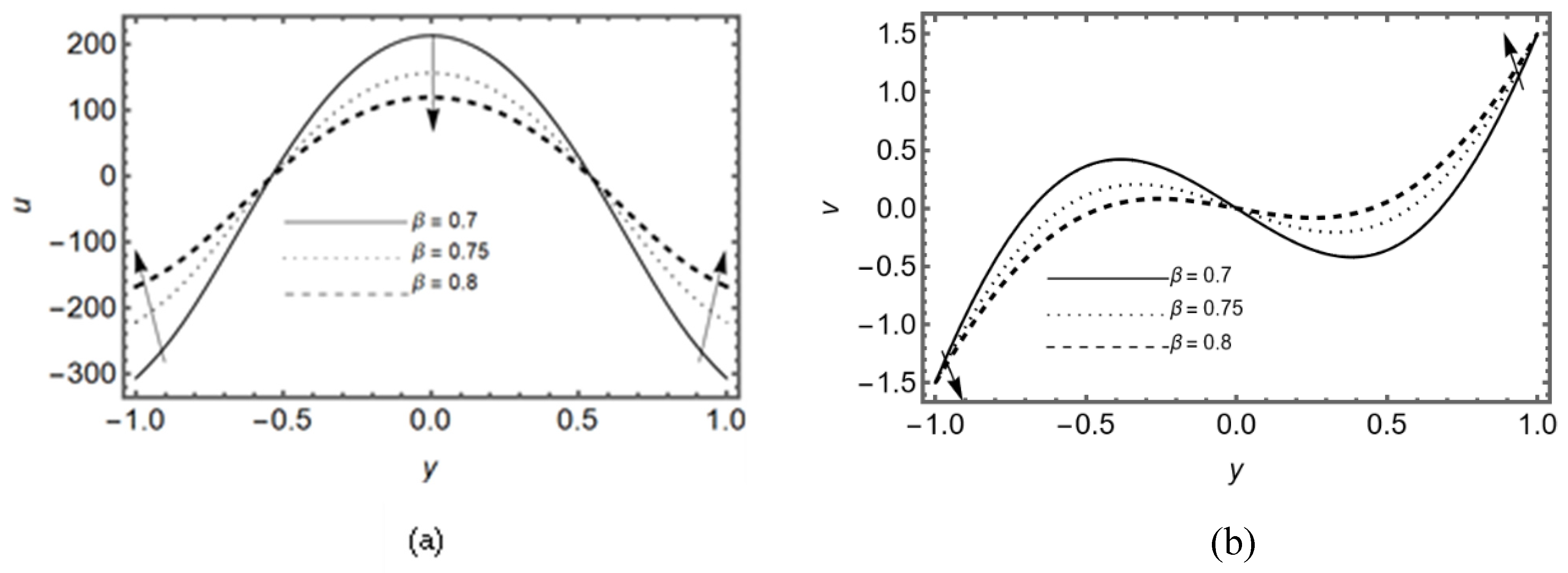

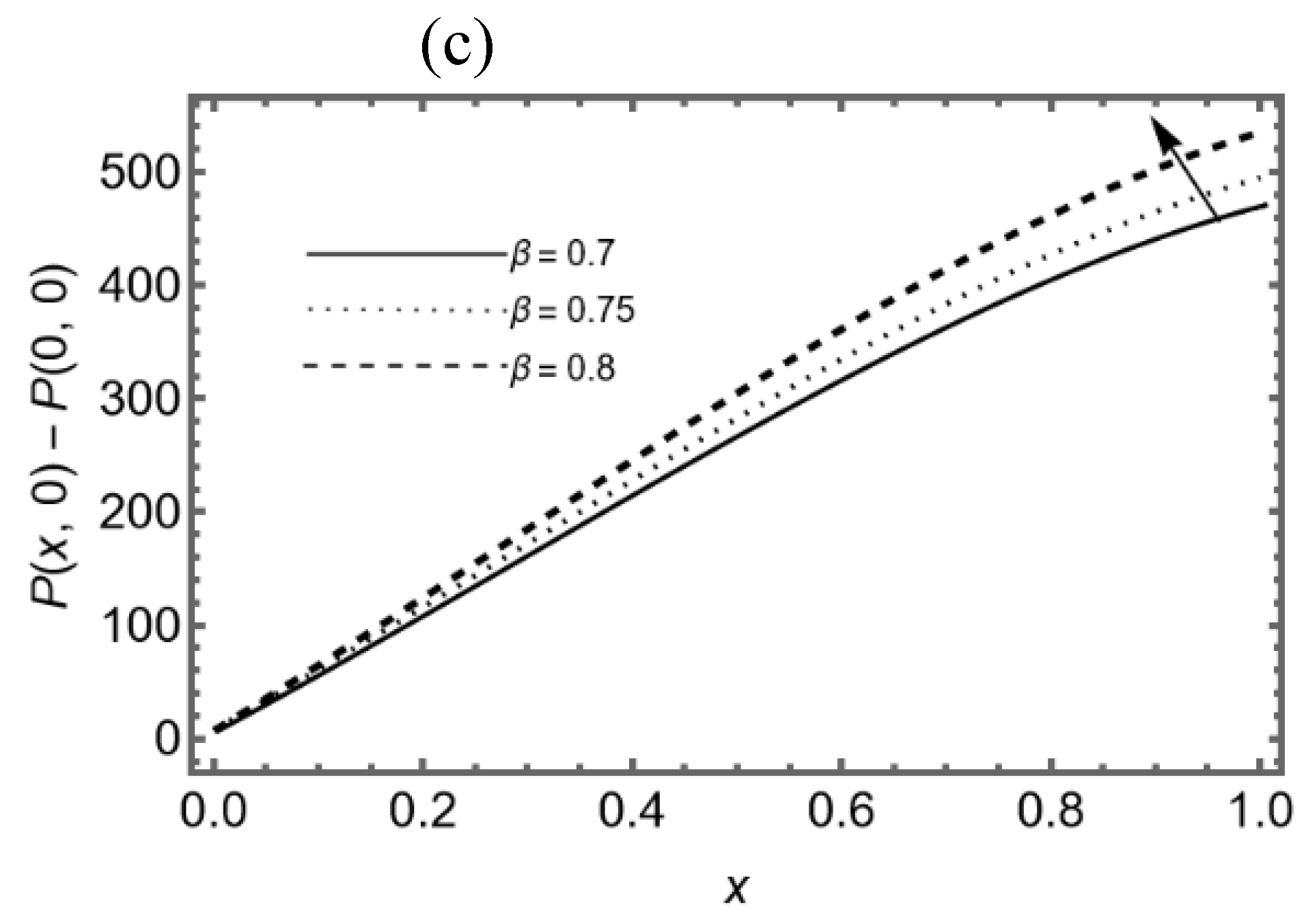

3.4. Effect of Slip Parameter β

Figure 6 (a-b) display that the axial and transverse velocity decay for different slip parameter

β at the middle of the slit. Furthermore, it is seen that axial velocity decays in reverse direction near the walls due to lubricated permeable membrane. The pressure difference on the slit is shown in

Figure 6c for various values of

β, it shows that the lubrication on membrane helps to increase the pressure in synovial fluid near the exit region of the slit.

4. Concluding Remarks

The current study observes the impact of lubricated membrane and linear re-absorption of nutrients in synovial fluid during the movement or running. A two-dimensional couple stress fluid model through a permeable lubricated slit with linear re-absorption at the wall is assumed to observe the flow properties of synovial fluid. This model produces the complex non-linear partial differential equations that are solved by applying the Langlois approach with mixed boundary conditions. This study calculates the analytical findings of flow characteristics, including shear stress, pressure difference, and velocity profile. This study reveals that the presence of inertial forces supports the decelerating flow in axial and transverse direction but enhances the pressure difference.

In this study we have ignored the bending effects of synovial membrane that will be discussed in future work.

References

- Yin, W.; Frame, M.D. (2011). Biofluid Mechanics: An Introduction to Fluid Mechanics, Macrocirculation, and Microcirculation. Academic Press.

- Lai, W.M.; Kuei, S.C.; Mow, V.C. Rheological equations for synovial fluids. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 1978, 100, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouerfelli, N.; Vrinceanu, N.; Mliki, E.; Amin, K.A.; Snoussi, L.; Coman, D.; Mrabet, D. Rheological behavior of the synovial fluid: a mathematical challenge. Frontiers in Materials 2024, 11, 1386694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Ganapathy, H.; Thanka, J. Synovial Fluid Analysis and Biopsy in Diagnosis of Joint Diseases. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 2021, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, S.; Abbas, I.; Al-Atawi, N.O.; Saqib, M.; Afzaal, M.F.; Mashat, D.S. Knee synovial fluid flow and heat transfer, a power law model. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, K.; Siddiqui, A.M.; Mehboob, H.; Jamil, Q. Study of non-Newtonian synovial fluid flow by a recursive approach. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, K.; Siddiqui, A.M.; Mehboob, H.; Tahir, A. Dynamics of non-Newtonian synovial fluid through permeable membrane with periodic filtration. International Journal of Modern Physics B 2024, 38, 2450251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanaiah, G. Squeeze films between finite plates lubricated by fluids with couple stress. Wear 1979, 54, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanaiah, G.; Sarkar, P. Slider bearings lubricated by fluids with stress. Wear 1979, 52, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Singh, C. Couple stresses in the lubrication of rolling contact bearings considering cavitation. Wear 1981, 67, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, T.; Sajjad, R.; Alsaedi, A.; Muhammad, T.; Ellahi, R. On squeezed flow of couple stress nanofluid between two parallel plates. Results in physics 2017, 7, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Sajid, M. Flow of two immiscible uniformly rotating couple stress fluid layers. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madasu, K.P.; Sarkar, P. Couple stress fluid past a sphere embedded in a porous medium. Archive of Mechanical Engineering 2022, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Bég, O.A.; Ghosh, S.K. A couple stress fluid modeling on free convection oscillatory hydromagnetic flow in an inclined rotating channel. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2014, 5, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, L.M. Flow of couple stress fluid through stenotic blood vessels. Journal of Biomechanics 1985, 18, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luti, S.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Gamberi, T.; Vassalle, C.; Pellegrino, A. (Eds.). (2024). Metabolic Responses and Adaptations to Exercise. Frontiers Media SA.

- Frisbie, D.D.; Al-Sobayil, F.; Billinghurst, R.C.; Kawcak, C.E.; McIlwraith, C.W. Changes in synovial fluid and serum biomarkers with exercise and early osteoarthritis in horses. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2008, 16, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.S. (2024). Converging Biological Effects of Physical Activity on Cardiovascular Health in Ageing.

- Hahn, A.K.; Batushansky, A.; Rawle, R.A.; Lopes, E.P.; June, R.K.; Griffin, T.M. Effects of long-term exercise and a high-fat diet on synovial fluid metabolomics and joint structural phenotypes in mice: an integrated network analysis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2021, 29, 1549–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, U.A.; Siddique, J.I.; Ahmed, A. Biomechanical response of soft tissues during passage of synovial fluid in compression. International Journal for Computational Methods in Engineering Science and Mechanics 2023, 24, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haward, S.J. Synovial fluid response to extensional flow: effects of dilution and intermolecular interactions. PLoS One 2014, 9, e92867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadique, M.; Shah, S.R.; Sharma, S.K.; Islam, S.M. Effect of significant parameters on squeeze film characteristics in pathological synovial joints. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, K.M.; Krause, W.E.; Jones, R.L.; Colby, R.H. Rheopexy of synovial fluid and protein aggregation. Journal of the royal society interface 2006, 3, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mow, V.C. The role of lubrication in biomechanical joints. Journal of Lubrication Technology 1969, 91, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hron, J.; Málek, J.; Pustějovská, P.; Rajagopal, K.R. On the modeling of the synovial fluid. Advances in Tribology 2010, 2010, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Gómez, E.; D’Amato, R. Approximate closed-form solution of the synovial fluid film force in the human ankle joint with non-Newtonian Lubricant. Tribology International 2013, 57, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, P.; Kodým, R.; Šnita, D.; Bouzek, K. Spatially two-dimensional mathematical model of the flow hydrodynamics in a spacer-filled channel – the effect of inertial forces. Journal of Membrane Science 2015, 492, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.M.; Haroon, T.; Shahzad, A. Hydrodynamics of viscous fluid through porous slit with linear absorption. Applied Mathematics and Mechanics 2016, 37, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.M.; Azim, Q.A.; Gawo, G.A.; Sohail, A. Analytical approach to explore theory of creeping flow with constant absorption. Sensors International 2024, 5, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).