Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- High specific surface area (e.g., graphene: ~2630 m² g⁻¹)

- Exceptional mechanical and thermal stability

- Tunable surface chemistry via functionalization

- Electrical conductivity (e.g., CNTs, graphene)

- Biocompatibility (e.g., CQDs, nanodiamonds)

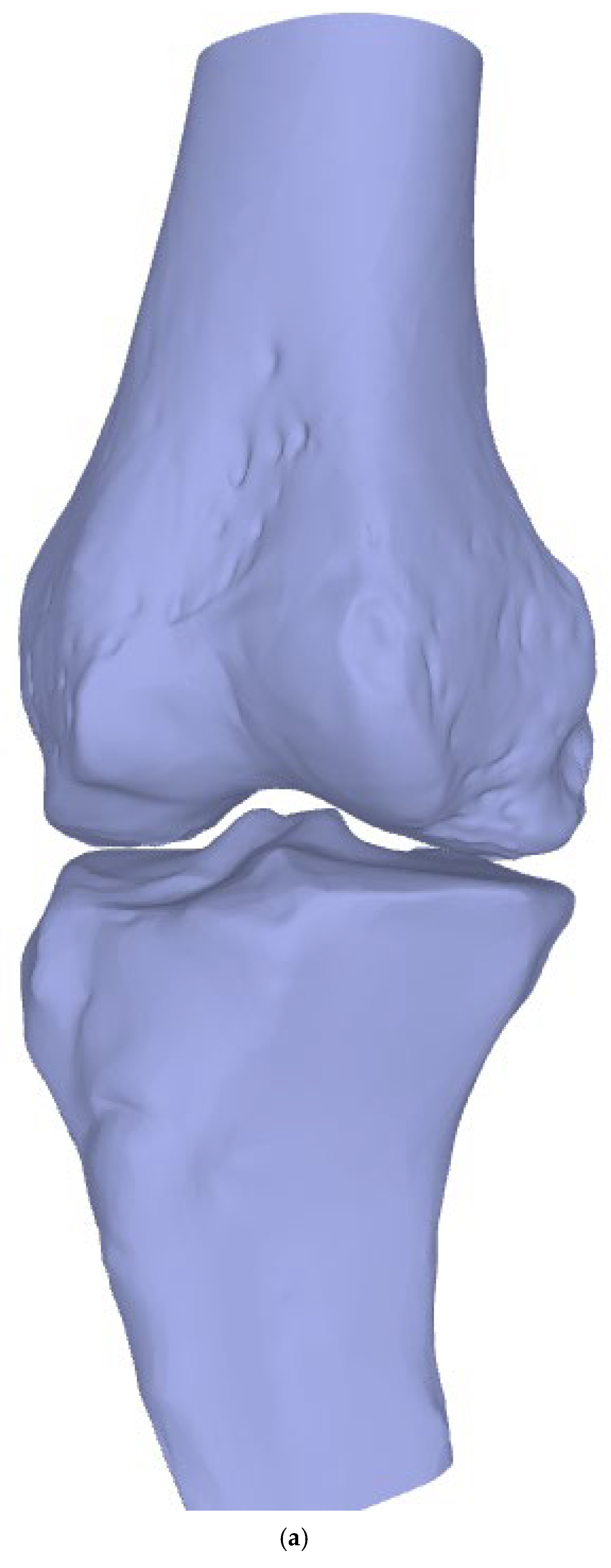

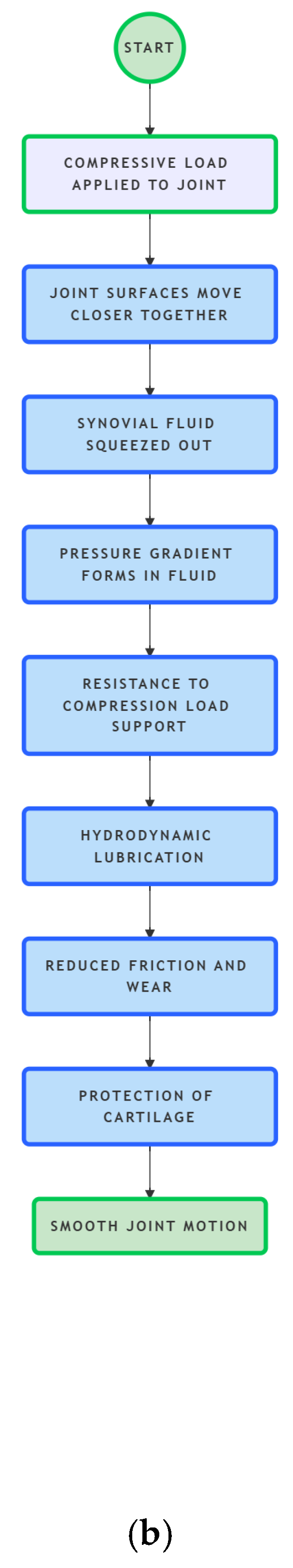

- Input: Compressive Load Applied to Join: Joint Surfaces Move Closer Together

- Joint Surfaces Move Closer Together: Synovial Fluid Squeezed Out

- Synovial Fluid Squeezed Out: Pressure Gradient Forms in Fluid

- Pressure Gradient Forms in Fluid: Resistance to Compression (Load Support)

- Resistance to Compression (Load Support): Hydrodynamic Lubrication

- Hydrodynamic Lubrication: Reduced Friction and Wear

- Reduced Friction and Wear: Protection of Cartilage

- Protection of Cartilage: Smooth Joint Motion

- Physisorption: Van der Waals forces, π-π stacking (e.g., CNTs for aromatic compounds).

- Chemisorption: Covalent bonding via functional groups (–COOH, –OH, –NH₂).

- Electrostatic interactions: GO for cationic dyes/metals.

2. Mathematical Model

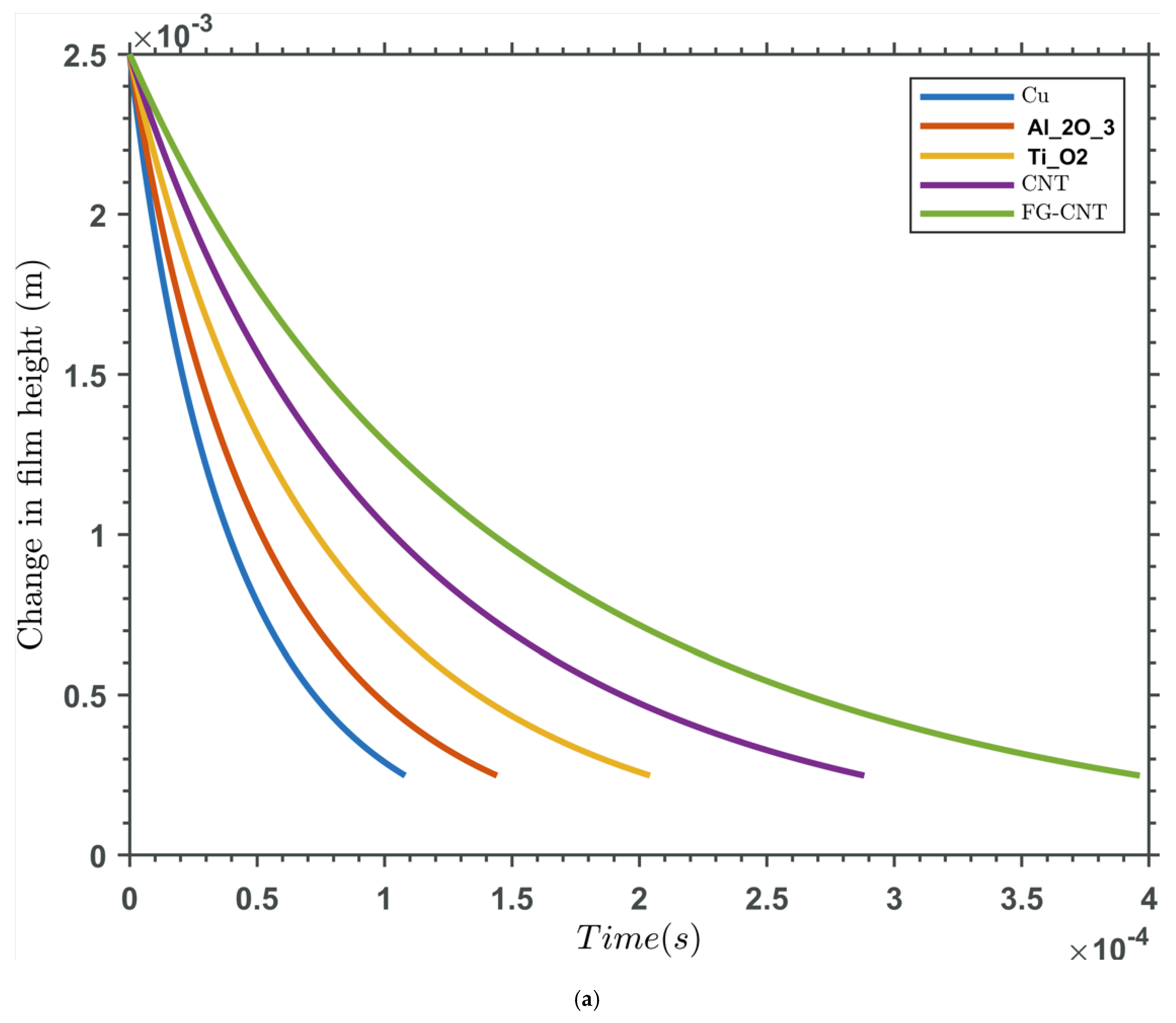

- Particle Concentration: Higher concentrations of nanoparticles generally lead to increased viscosity due to particle interactions.

- Nanoparticle Size and Shape: The size, shape, and material properties of nanoparticles play a significant role in determining the overall viscosity of the fluid.

- Base Fluid Properties: The viscosity of the base fluid, its temperature, and its molecular structure also impact the viscosity of the resulting nanofluid.

- Temperature: Viscosity is typically temperature-dependent, and the thermal behaviour of both the base fluid and the nanoparticles must be considered.

- Accuracy: Some empirical models are accurate for specific types of nanoparticles but may not generalize well to all systems.

- Complexity: Theoretical models often provide a deeper understanding but may require more complex calculations and assumptions.

- Applicability: The choice of model depends on the specific application and the parameters involved, including temperature and particle concentration.

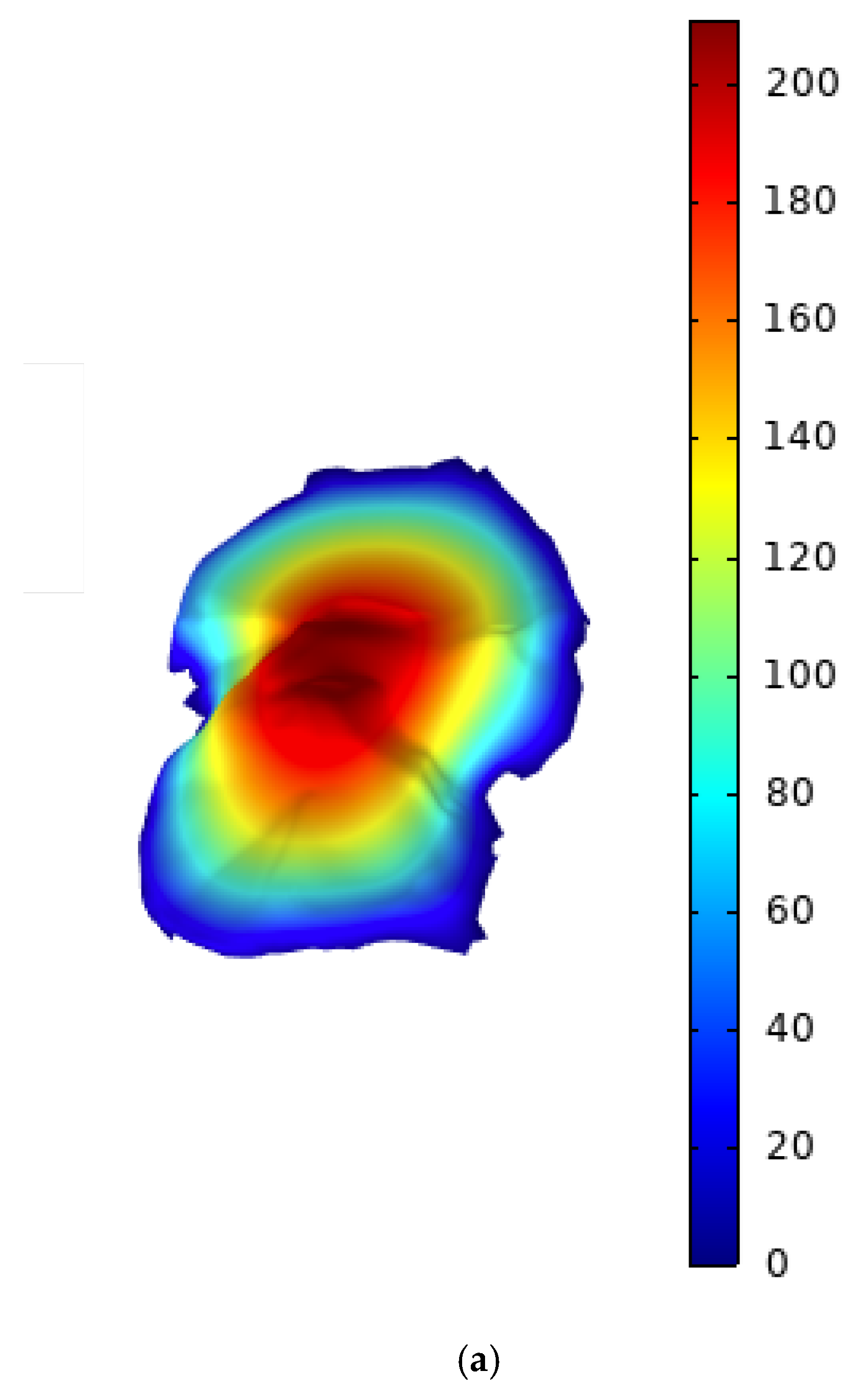

3. Results and Discussions

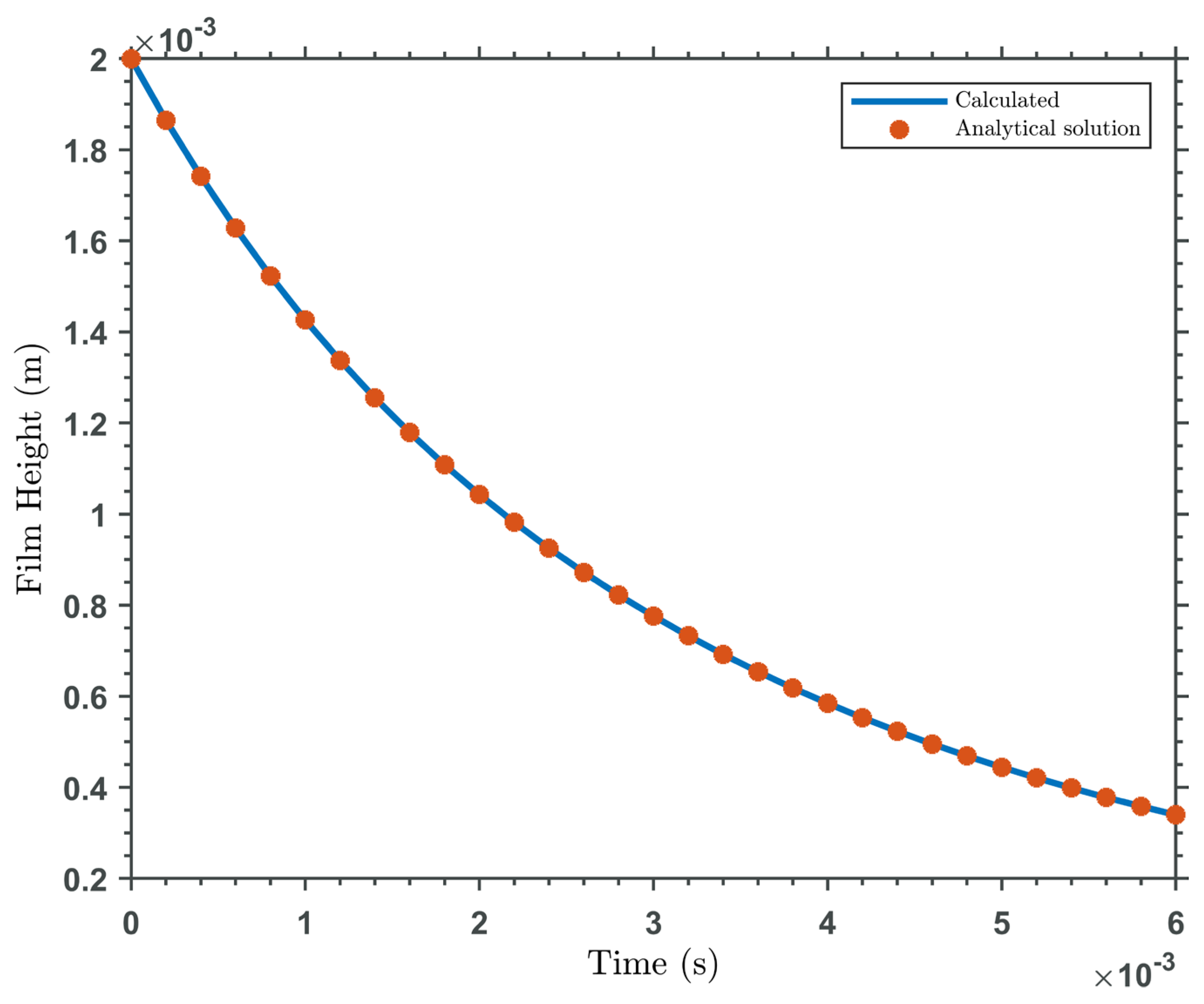

Validation

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

References

- Buongiorno, J. (2005). Convective transport in nanofluids. Journal of Heat Transfer, 128(3), 240–250. [CrossRef]

- Prasher, R. , Song, D., Wang, J., & Phelan, P. (2006a). Measurements of nanofluid viscosity and its implications for thermal applications. Applied Physics Letters, 89(13). [CrossRef]

- Prasher, R. , Song, D., Wang, J., & Phelan, P. (2006b). Measurements of nanofluid viscosity and its implications for thermal applications. Applied Physics Letters, 89(13). [CrossRef]

- Murshed, S., Leong, K., & Yang, C. (2007). Investigations of thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 47(5), 560–568. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Ding, Y., & Tan, C. (2007). Rheological behaviour of nanofluids. New Journal of Physics, 9(10), 367. [CrossRef]

- Xian-Ju, W. , & Xin-Fang, L. (2009). Influence of pH on nanofluids’ viscosity and thermal conductivity. Chinese Physics Letters, 26(5), 056601. [CrossRef]

- Zhao-Zhi, Z. (2011). Experimental study on nano-fluids viscosity in low-temperature phase transition storage. Chemical Engineering & Machinery. https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-HGJX201104008.

- Bhadauria, B. S., & Agarwal, S. (2011). Convective Transport in a Nanofluid Saturated Porous Layer With Thermal Non Equilibrium Model. Transport in Porous Media, 88(1), 107–131. [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, F. , & Mirdamadi, H. R. (2012). Influence of Knudsen number on fluid viscosity for analysis of divergence in fluid conveying nano-tubes. Computational Materials Science, 61, 270–277. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R. (2012). Effect of temperature on rotational viscosity in magnetic nano fluids. The European Physical Journal E, 35(10). [CrossRef]

- Yiamsawas, T. , Dalkilic, A. S., Mahian, O., & Wongwises, S. (2013). Measurement and Correlation of the Viscosity of Water-Based Al2O3and TiO2Nanofluids in High Temperatures and Comparisons with Literature Reports. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology, 34(12), 1697–1703. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D. , & Bég, O. A. (2013). A study on peristaltic flow of nanofluids: Application in drug delivery systems. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 70, 61–70. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, N. S., Raza, M., & Ellahi, R. (2015). Influence of induced magnetic field and heat flux with the suspension of carbon nanotubes for the peristaltic flow in a permeable channel. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 381, 405–415. [CrossRef]

- Kasaeian, A. , & Nasiri, S. (2015). Convection Heat Transfer Modeling of Nano- fluid Tio2 Using Different Viscosity Theories. International Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 11(1), 45–51. http://www.ijnnonline.net/article_12362_b0ba7d8eaabdb63dfe71272d721b9bc1.

- Ibrahim, W. , & Makinde, O. D. (2015). Magnetohydrodynamic Stagnation Point Flow and Heat Transfer of Casson Nanofluid Past a Stretching Sheet with Slip and Convective Boundary Condition. Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 29(2). [CrossRef]

- Afrand, M. , Toghraie, D., & Ruhani, B. (2016). Effects of temperature and nanoparticles concentration on rheological behavior of Fe 3 O 4 –Ag/EG hybrid nanofluid: An experimental study. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, 77, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, T. , Nandan, G., Prakash, R., & Muthuraman, M. (2018). Investigations on Viscosity and Thermal Conductivity of Cobalt oxide- water Nano fluid. Materials Today Proceedings, 5(2), 6176–6182. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M. F. , Soleimani, H., Merican, Z. M. A., Sinnathambi, C. M., Stephen, K. D., & Ahmad, A. A. (2019). Nano-fluid viscosity screening and study of in situ foam pressure buildup at high-temperature high-pressure conditions. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology, 10(3), 1115–1126. [CrossRef]

- Voß, J. , & Wittkowski, R. (2022). Acoustic propulsion of nano- and microcones: dependence on the viscosity of the surrounding fluid. Langmuir, 38(35), 10736–10748. [CrossRef]

- 20 - Farooq, U. , Hussain, M., & Farooq, U. (2023). Non-similar analysis of chemically reactive bioconvective Casson nanofluid flow over an inclined stretching surface. ZAMM - Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics / Zeitschrift Für Angewandte Mathematik Und Mechanik, 104(2). [CrossRef]

- McCutchen, C. W. (1950). The Theory of Lubrication. The Journal of Applied Mechanics.

- Bhushan, B. , and Gupta, B. K. (1991). Introduction to Tribology. Wiley.

- Dowson, D. (1967). Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication: The Fundamentals of Roller and Gear Lubrication. Pergamon Press.

- Hamrock, B. J. , & Dowson, D. (1981). Ball Bearing Lubrication: The Elastohydrodynamics of Elliptical Contacts. Wiley.

- Wang, X. , & Xu, X. (2002). Thermal Conductivity of Nanoparticle-Fluid Mixture. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, 16(4), 474-480.

- Zhang, Y., & Craster, R. V. (2005). Theoretical Studies of Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication in Synovial Joints. Journal of Biomechanics 2005, 38, 1015–1023.

- Murshed, S. M. S. , & de Castro, C. A. N. (2012). Nanofluids: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Nova Science Publishers.

| Base Fluid | Nanoparticle Type | Nanoparticle Concentration | Viscosity (mPas) | Temperature (oC) | Reference/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Al₂O₃ (Alumina) | 1% vol. | 0.96 | 25 | Enhanced viscosity due to nanoparticle addition. |

| Water | TiO₂ (Titanium Dioxide) | 2% vol. | 1.1 | 30 | Viscosity increases with higher concentration. |

| Ethylene Glycol | CuO (Copper Oxide) | 0.5% vol. | 16.5 | 40 | Significant viscosity enhancement in glycol-based fluids. |

| Engine Oil | SiO₂ (Silica) | 0.1% vol. | 120 | 50 | Improved lubrication properties for industrial applications. |

| Water | Graphene Oxide | 0.2% wt. | 1.05 | 25 | Excellent lubrication for biomedical applications. |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Au (Gold) | 0.01% wt. | 12 | 37 | Biocompatible nanofluid for synovial joint applications. |

| Polyethylene Glycol | Fe₃O₄ (Iron Oxide) | 0.5% vol. | 8.2 | 37 | Magnetic nanofluid for targeted drug delivery. |

| Water | ZnO (Zinc Oxide) | 1% vol. | 1.02 | 25 | Antibacterial properties with moderate viscosity increase. |

| Silicone Oil | CNT (Carbon Nanotubes) | 0.3% wt. | 450 | 30 | High viscosity for specialized lubrication. |

| Water | CeO₂ (Cerium Oxide) | 0.1% wt. | 0.98 | 25 | Antioxidant properties for tissue regeneration. |

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | The generation of fluid pressure in synovial fluid between joint surfaces under compressive loading, leading to lubrication and load support. |

| Mechanism | As joint surfaces move closer together, synovial fluid is squeezed out, creating a pressure gradient that resists the compression and lubricates the joint. |

| Fluid Involved | Synovial fluid, a viscous, non-Newtonian fluid with properties like shear-thinning and elasticity. |

| Key Parameters | - Fluid viscosity |

| - Gap height between surfaces | |

| - Loading rate | |

| - Surface geometry | |

| Role in Joint Lubrication | Provides hydrodynamic lubrication, reducing friction and wear between cartilage surfaces. |

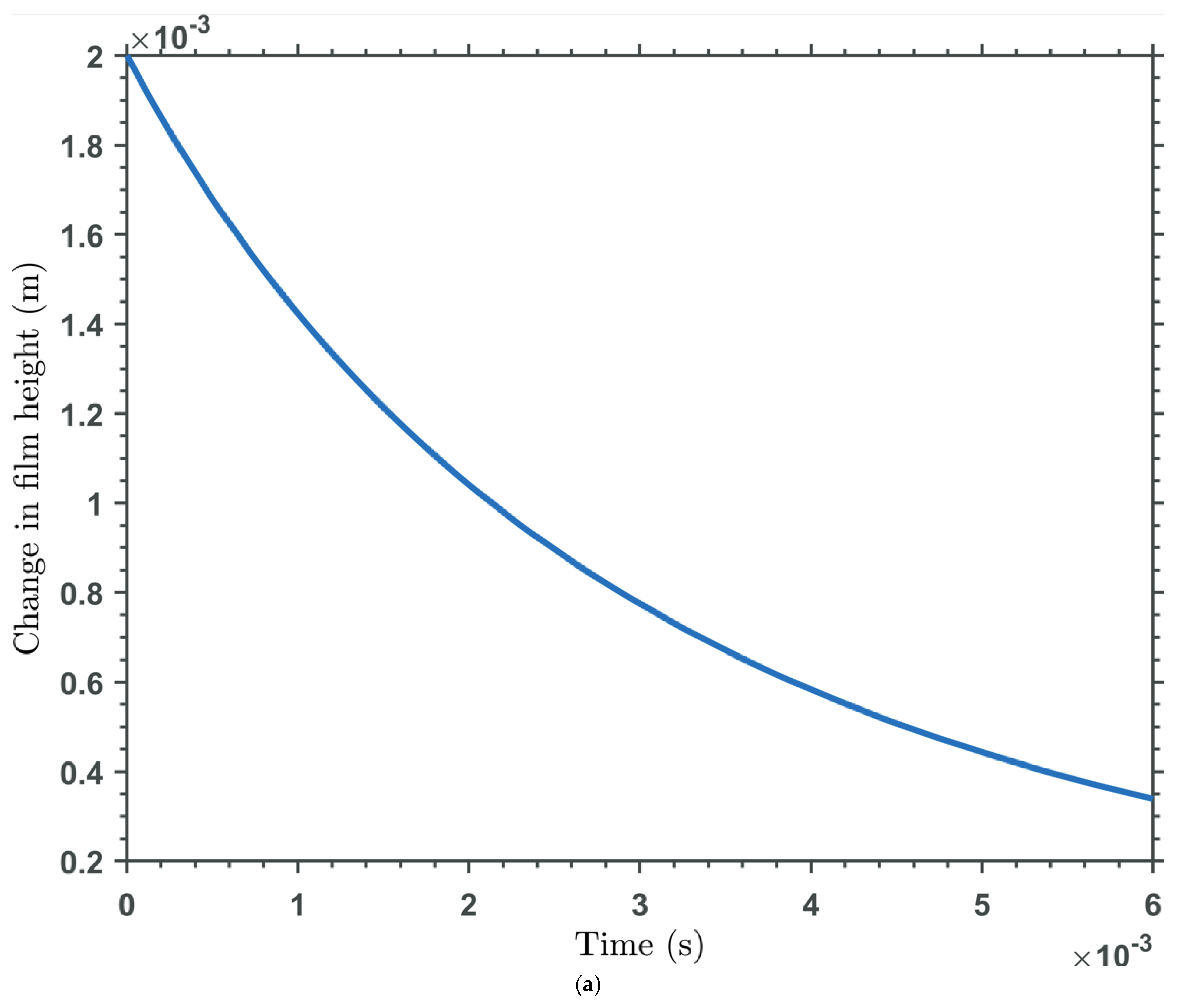

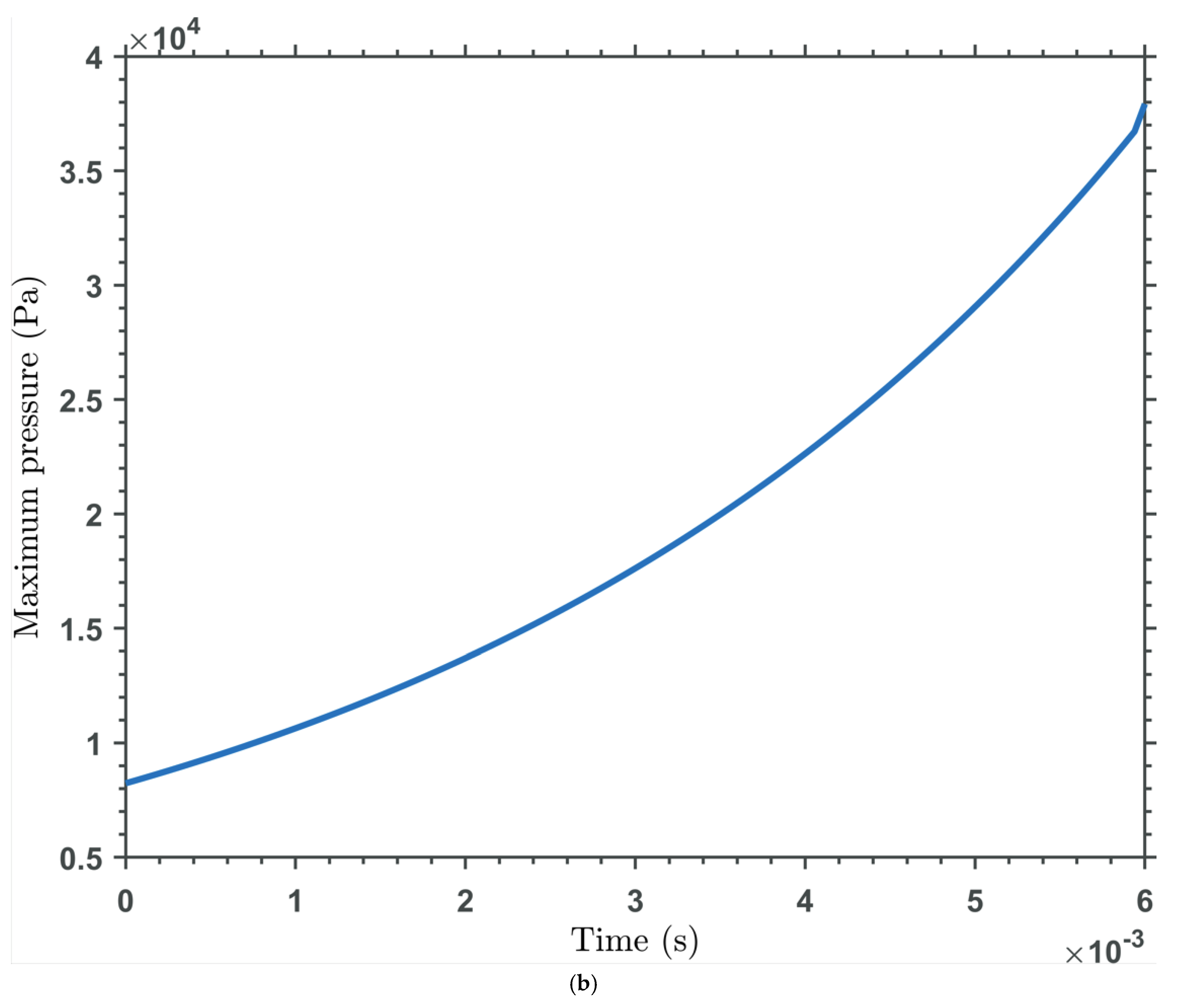

| Time Dependency | Squeeze-film effects are time-dependent, with pressure decaying as fluid is expelled over time. |

| Applications | - Understanding joint mechanics |

| - Designing prosthetics | |

| - Diagnosing joint disorders | |

| Mathematical Modeling | overned by Reynolds equation for thin-film lubrication, incorporating fluid viscosity and surface motion. |

| Challenges | - Complex fluid behavior (non-Newtonian) |

| - Dynamic loading conditions | |

| - Surface roughness and deformation | |

| Biological Significance | Protects cartilage from damage, distributes loads evenly, and ensures smooth joint motion. |

| Parameter | Nominal Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Synovial Fluid Viscosity | 0.01 – 5 Pa·s (shear-dependent) | Viscosity of synovial fluid, which is non-Newtonian and shear-thinning. |

| Cartilage Thickness | 1 – 6 mm | Thickness of articular cartilage covering the bone surfaces in the joint. |

| Joint Gap Height | 0.01 – 0.1 mm (under load) | Distance between articulating surfaces during joint movement or loading. |

| Load on Joint | 1 – 10 times body weight (e.g., 700 – 7000 N) | Compressive forces experienced by joints during activities like walking or running. |

| Synovial Fluid Film Thickness | 1 – 100 µm | Thickness of the fluid film between cartilage surfaces during lubrication. |

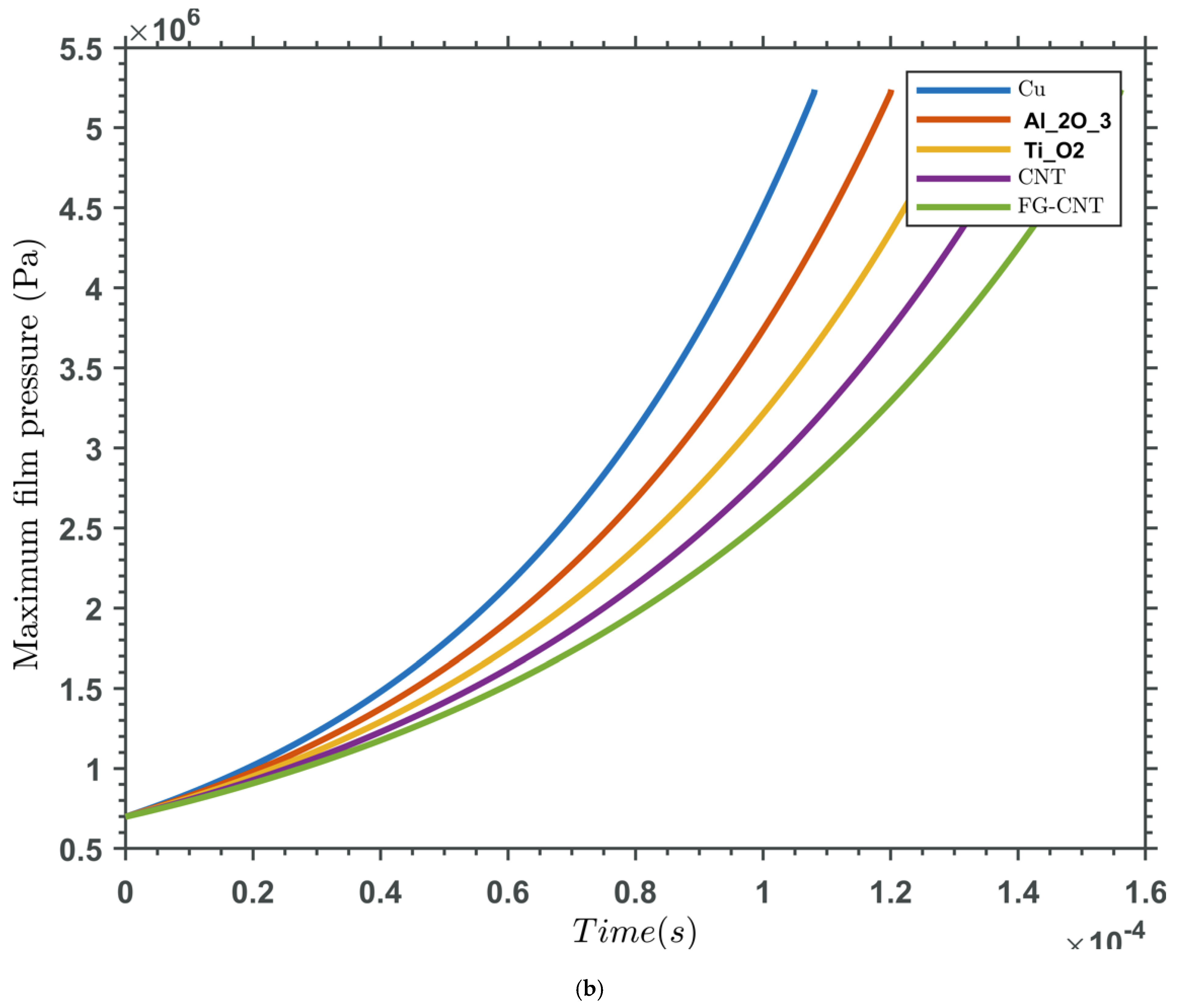

| Pressure in Synovial Fluid | 0.1 – 10 Mpa | Fluid pressure generated during joint loading and movement. |

| Cartilage Elastic Modulus | 0.5 – 20 Mpa | Stiffness of articular cartilage, which deforms under load. |

| Poisson’s Ratio of Cartilage | 0.4 – 0.5 | Measure of cartilage’s compressibility. |

| Shear Rate in Synovial Fluid | 10 – 10,000 s⁻¹ | Rate of deformation of synovial fluid during joint motion. |

| Joint Surface Roughness | 0.1 – 10 µm | Roughness of cartilage surfaces, affecting lubrication and friction. |

| Synovial Fluid pH | 7.2 – 7.4 | Slightly alkaline pH of synovial fluid. |

| Temperature in Joint | 32 – 34°C | Temperature within the joint cavity, slightly lower than core body temperature. |

| Hydraulic Permeability of Cartilage | 10⁻¹⁵ - 10⁻¹³ m² | Ability of cartilage to allow fluid flow through its porous structure. |

| Lubricin Concentration | 0.1 – 1 mg/mL | Concentration of lubricin, a key boundary lubricant in synovial fluid. |

| Hyaluronic Acid Concentration | 2 – 4 mg/mL | Concentration of hyaluronic acid, which contributes to synovial fluid viscosity. |

| CNM | Target Pollutant | Adsorption Capacity | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ | 500–1200 mg g⁻¹ | Chelation, ion exchange |

| MWCNTs | Bisphenol A, Dyes | 200–800 mg g⁻¹ | π-π stacking, H-bonding |

| CQDs | Hg²⁺, Cr(VI) | Fluorescence quenching | Surface complexation |

| Nanodiamonds | Pharmaceuticals | 150–400 mg g⁻¹ | Hydrophobic interactions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).