Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental Approach to the Problem

Stage 1: Identification of the Research Question/Objective

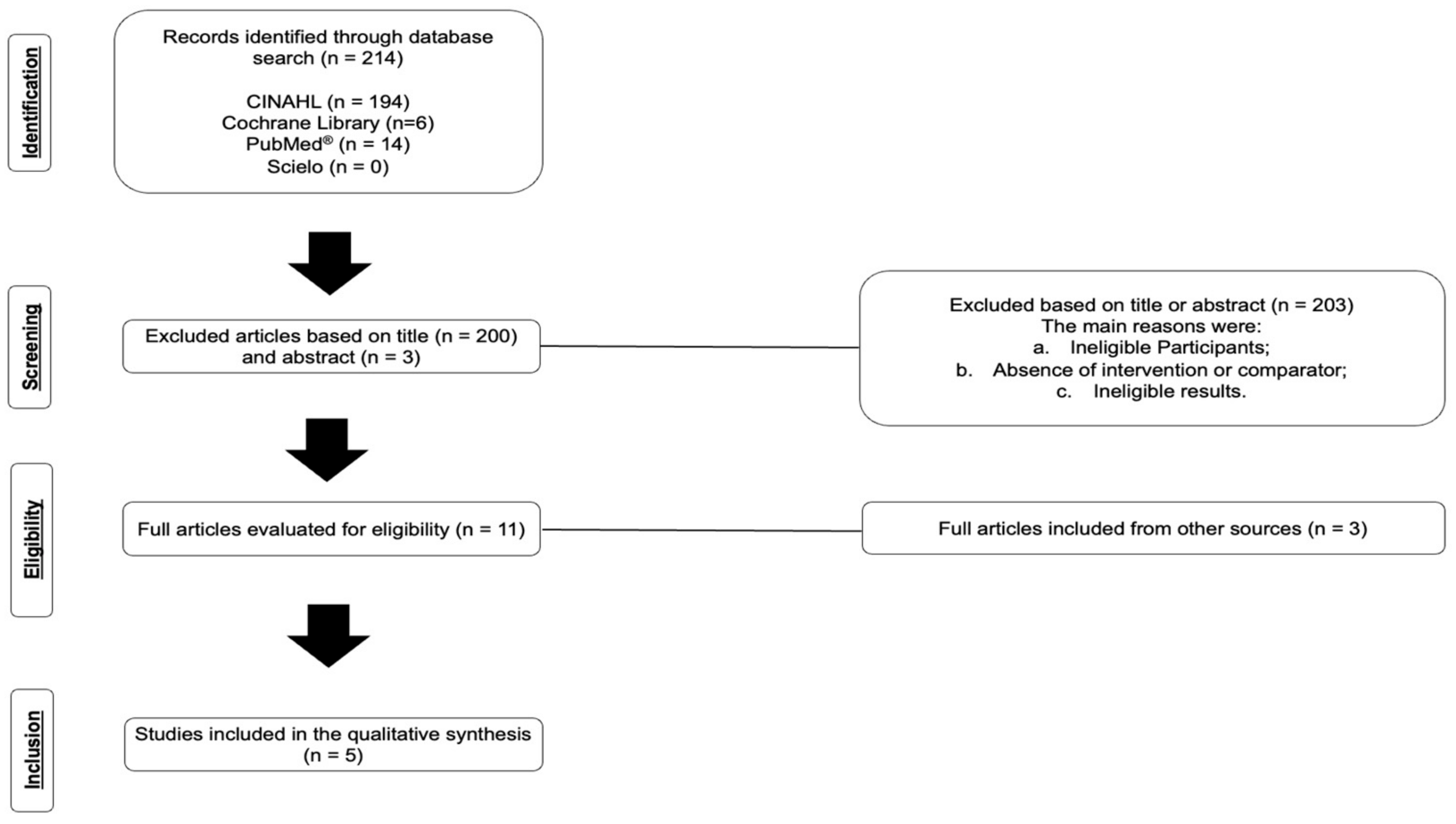

Stage 2: Identification of Relevant Studies

Stage 3: Study Selection

Stage 4: Data Mapping

Stage 5: Gathering, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

Study Quality

Hemodynamic Response

Autonomic Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| PEH | Post-Exercise Hypotension |

| ST | Strength Training |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| MM | Manual Massage |

| FR | Foam Rolling |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews |

| CINAHL | Nursing and Allied Health |

| SS | Static Stretching |

References

- Schiffrin, E.L. Immune mechanisms in hypertension and vascular injury. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014, 126, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E.; Collins, K.J.; Hilmmerfab, C.D.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCN. A Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2018, 138, 426–483.

- Macdonald, H.V.; Johnson, B.T.; Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Livingston, J.; Forsyth, K.C.; Kraemer, W.J. Dynamic resistance training as stand-alone antihypertensive lifestyle therapy: a meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2016, 5, e003231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.T.; Bundy, J.D.; Kelly, T.N.; Reed, J.E.; Keaney, P.M.; Reynolds, K.; Chen, J.; He, Jiang, He. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation 2016, 134, 441–450.

- American College of Sports Medicine - Position Stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sport Exerc 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Appes, L.J.; Rubenfire, M.; Ogedegbe, G.; Bisognano, J.D.; Elliott, W.J.; Fuchs, F.D.; Hughes, J.W.; Lacland, D.T.; Staffileno, B.A.; et al. Beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2013, 61, 1360–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.D.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J. ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 140, e596–e646. [Google Scholar]

- Pescatello, L.S.; Buchner, D.M.; Jakicic, J.M.; Powell, K.E.; Kraus, W.E.; Bloodgood, B.; Campbell, W.W.; Dietz, S.; Dipietro, L.; George, S.M.; et al. Physical activity to prevent and treat hypertension: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019, 51, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo, A.S.F.; Farinatti, P.; Borges, J.P.; De Paula, T.; Monteiro, W. Institutional Guidelines for Resistance Exercise Training in Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Sports Med 2019, 49, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casonatto, J.; Goessler, K.F.; Cornelissen, V.A.; Cardoso, J.R.; Polito, M.D. The blood pressure-lowering effect of a single bout of resistance exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016, 23, 1700–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotfiel, T.; Swoboda, B.; Krinner, S.; Grim, C.; Engelhardt, M.; Uder, M.; Heiss, R.U. Acute effects of lateral thigh foam rolling on arterial tissue perfusion determined by spectral doppler and power doppler ultrasound. J Strength Cond Res 2017, 31, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, T.; Masuhara, M.; Ikuta, K. Acute effects of self-myofascial release using a foam roller on arterial function. J Strength Cond Res 2014, 28, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, I.C.; Chen, S.L.; Wang, M.Y.; Tsai, P.S. Effects of massage on blood pressure in patients with hypertension and prehypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2016, 31, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beardsley, C.; Škarabot, J. Effects of self-myofascial release: A systematic review. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2015, 19, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.M. The effect of resistance exercise on recovery blood pressure in normotensive and borderline hypertensive women. J Strength Cond Res 2001, 15, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, T.; Willardson, J.M.; Miranda, H.; Bentes, C.M.; Reis, V.M.; De Salles, B.F.; Simão, R. Influence of rest interval length between sets on blood pressure and heart rate variability after a strength training session performed by pre hypertensive men. J Strength Cond Res 2016, 30, 1813–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, J.J.; Kravitz, L. A Review of the Acute Cardiovascular Responses to Resistance Exercise of Healthy Young and Older Adults. J Strength Cond Res 1999, 13, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio, C.L. Antonio, C. L. Nobrega, Donal O'Leary, Bruno Moreira Silva, Elisabetta Marongiu, Massimo F. Piepoli, and Antonio Crisafulli, “Neural Regulation of Cardiovascular Response to Exercise: Role of Central Command and Peripheral Afferents,” BioMed Research International, vol. 2014, Article ID 478965, 20 pages, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gladwell, V.F.; Coote, J.H. Heart rate at the onset of muscle contraction and during passive muscle stretch in humans: a role for mechanoreceptors. J Physiol 2002, 540, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inami, T.; Bara, R.; Nakagari, A.; Shimizu, T. Acute changes in peripheral vascular tonus and systemic circulation during static stretching. Res Sports Med 2015, 23, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.R.; Pescatello, L.S.; Winchester, J.B.; Corrêa Neto, V.G.; Brown, A.F.; Budde, H.; Marchetti, P.H.; Silva, J.G.; Vianna, J.M.; Novaes, J.S. Effects of manual therapies and resistance exercise on postexercise hypotension in women with normal blood pressure. J Strength Cond Res 2022, 36, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O´Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.; Brunnhuber, K.; Chalkidou, K.; Chalmers, I.; Clarke, M.; Fenton, M.; Forbes, C.; Glanville, J.; Hickes, N.J.; Moody, J.; et al. How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ 2006, 333, 804–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Evidence-Based Physiotherapy, 2024. Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Available online: https://pedro.org.au/english/resources/pedro-scale/ (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Lastova, K.; Nordvall, M.; Walters-Edwards, M.; Allnutt, A.; Wong, A. Cardiac autonomic and blood pressure responses to an acute foam rolling session. J Strength Cond Res 2018, 32, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.R.; Vingren, J.L.; Pescatello, L.S.; Corrêa Neto, V.G.; Brown, A.F.; Kingsley, J.D.; Silva, J.G.; Vianna, J.M.; Novaes, J.S. Effects of foam rolling and strength training on post exercise hypotension in normotensive women: a cross-over study. J Bodyw Mov Therapies 2023, 34, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.R.; Pescatello, L.S.; Leitão, L.; De Miranda, M.J.C.; Marchetti, P.H.; Novaes, M.R.; Araújo, G.S.; Corrêa Neto, V.G.; Novaes, J.S. Muscular Performance and Blood Pressure After Different Pre-Strength Training Strategies in Recreationally Strength-Trained Women: Cross-Over Trial. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2024, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walaszek, R. Impact of classic massage on blood pressure in patients with clinically diagnosed hypertension. J Tradit Chin Med 2015, 35, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Garakyaragui, M.; Eshghinezhad, A.; Moeini, M.; Ghasempour, Z. Long-term effect of massage therapy on blood pressure prehypertensive women. J Educ Health Promot 2018, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020, 16, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkley, K.J.; Hubscher, C.H. Are there separate central nervous system pathways for touch and pain? Nat Med 1995, 1, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlone, F.; Valbo, A.B.; Olausson, H.; Loken, L.; Wessberg, J. Discriminative touch and emotional touch. Can J Exp Psychol 2007, 61, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preusser, S.; Thiel, S.D.; Rook, C.; Roggenhofer, E.; Kosatschek, A.; Draganski, B.; Blankenburg, F.; Driver, J.; Villringer, A.; Pleger, B. The perception of touch and the ventral somatosensory pathway. Brain 2015, 138, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.W.; Raven, P.B. Autonomic neural control of heart rate during dynamic exercise: revisited. J Physiol 2014, 592, 2491–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Araújo, G.; Behm, D.G.; Monteiro, E.R.; De Melo Fiuza, A.G.F.; Gomes, T.M.; Vianna, J.M.; Reis, M.S.; Novaes, J.S. Order effects of resistance and stretching exercises on heart rate variability and blood pressure in healthy adults. J Strength Cond Res 2019, 33, 2684–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.; Gomes, T.M.; Sousa, M.S.; Saraiva, A.R.; Araújo, S.A.; Figueiredo, T.; Novaes, J.S. Static stretch performed after strength training session induces hypotensive response in trained men. J Strength Cond Res 2019, 33, 2981–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, N.T.; Scheuermann, B.W. Cardiovascular responses to skeletal muscle stretching: “stretching” the truth or a new exercise paradigm for cardiovascular medicine? Sports Med 2017, 47, 2507–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies | Sample Size (n = 75) | Age (years) | Height | Body Mass (kg) | Training Status | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okamoto et al. [12] | 10 (7 men and 3 women) | 19.9 ± 0.3 | 162.7 ± 8.1 cm | 60.6 ± 11.2 | Recreational strength training | Both sexes |

| Hotfiel et al. [11] | 21 (12 men and 9 women) | 25 ± 2 | 177 ± 9 cm | 74 ± 9 | Recreational strength training | Both sexes |

| Lastova et al. [27] | 15 (8 men and 7 women) | 21.55 ± 0.52 | 1.72 ± 0.02 m | 74.79 ± 2.88 | N/A | Both sexes |

| Monteiro et al. [21] | 16 | 25.1 ± 2.9 | 158.9 ± 4.1 cm | 59.5 ± 4.9 | Recreational strength training | Women |

| Monteiro et al. [28] | 16 | 25.5 ± 2.0 | 155.7 ± 4.4 cm | 61.2 ± 5.4 | Recreational strength training | Women |

| Monteiro et al. [29] | 12 | 27.2 ± 3.3 | 164.8 ± 5.5 cm | 69.8 ± 6.0 | Recreational strength training | Women |

| Studies | Objective | Interventions | Results | PEDro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okamoto et al. [12] | Investigate the acute effect of foam rolling on arterial stiffness and vascular endothelial function. | The foam rolling condition was performed on the adductors, hamstrings, quadriceps, iliotibial band, and trapezius regions. Each participant practiced 2 or 3 times to learn the correct foam rolling technique with the guidance of a coach and performed 20 repetitions in each region with 1-minute intervals. The pressure was self-adjusted by applying body weight to the roller and using hands and feet to regulate pressure as needed. The roller was placed under the target tissue area, and the body was moved back and forth along the roller. In the control condition, participants rested in a quiet, temperature-controlled room while lying supine. |

The ankle-brachial pulse wave velocity significantly decreased (from 1202 ± 105 to 1074 ± 110 cm/s), and plasma nitric oxide concentration significantly increased (from 20.4 ± 6.9 to 34.4 ± 17.2 μmol/L) after the myofascial release condition with foam rolling (both p < 0.05), but neither of them differed significantly after the control condition. | 5 (moderate) |

| Hotfiel et al. [11] | Evaluate the effect of foam rolling on arterial blood flow in the lateral thigh region. | The exercise protocol consisted of 3 sets, each with 45 seconds of foam rolling on the lateral thigh region in the sagittal plane (with 20 seconds of rest between sets). | Arterial tissue perfusion was assessed using Spectral Doppler and Power Doppler Ultrasonography, represented by peak flow velocity, time-averaged maximum velocity, time-averaged mean velocity, and resistive index. Ultrasound data were evaluated under resting conditions (after 20 minutes of rest in a horizontal position) to establish baseline values. The second and third measurements were taken immediately after and 30 minutes after the foam rolling intervention. |

5 (moderate) |

| Lastova et al. [27] | Assess the effects of an acute foam rolling session on heart rate variability and blood pressure in healthy individuals. | In the foam rolling condition, individuals completed 10 repetitions of foam rolling per target area of the body (adductors, hamstrings, quadriceps, iliotibial band, gastrocnemius, and upper trapezius), followed by 1 minute of rest. Each repetition involved moving the target tissue across the roller in a smooth motion at a rate of 2 seconds down and 2 seconds up, as determined by a metronome. The control condition only involved measurements without the application of other experimental conditions. |

Measurement of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, as well as heart rate variability, was conducted at 10 and 30 minutes. The authors observed significant increases (p<0.01) in markers of vagal tone (normalized high-frequency power) 30 minutes after foam rolling, while no changes were observed after the control condition. There were also significant reductions (p<0.05) in markers of sympathetic activity (normalized low-frequency power) and sympathovagal balance (normalized low-frequency to high-frequency ratio). |

7 (high) |

| Monteiro et al. [21] | Examine the acute effects of resistance exercise and different manual therapies (static stretching and manual massage) performed separately or combined on blood pressure responses during recovery in normotensive women. | The control condition consisted solely of measurements without applying any other experimental conditions. Isolated strength training comprised three sets of bench press, back squat, and leg press at an intensity controlled to 80% of 10RM. The isolated static stretching and isolated manual massage conditions were applied unilaterally in two sets of 120 seconds for each quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf region. In the combined condition of strength training and static stretching, stretching was performed immediately after strength training, following the same descriptions as above. In the combined condition of strength training and manual massage, the massage was conducted immediately after strength training, following the same descriptions as above. |

Measurement of systolic and diastolic blood pressure at rest and every 10 minutes after each protocol (Post-0, Post-10, Post-20, Post-30, Post-40, Post-50, and Post-60). Post-exercise hypotension was observed in the experimental conditions of isolated strength training at Post-50 (p = 0.038; d = -2.24; ∆ = -4.0 mmHg), isolated static stretching at Post-50 (p = 0.021; d = -2.67; ∆ = -5.0 mmHg), and Post-60 (p = 0.008; d = -2.88; ∆ = -5.0 mmHg), and isolated manual massage at Post-50 (p = 0.011; d = -2.61; ∆ = -4.0 mmHg) and Post-60 (p = 0.011; d = -2.74; ∆ = -4.0 mmHg). Post-exercise hypotension was also observed in the combined condition of strength training and static stretching at Post-60 (p = 0.024; d = -3.12; ∆ = -5.0 mmHg). |

7 (high) |

| Monteiro et al. [28] | Examine the acute effects of resistance exercise and foam rolling performed separately or combined on blood pressure responses during recovery in normotensive women. | The control condition consisted solely of measurements without applying any other experimental conditions. Isolated strength training comprised three sets of bench press, back squat, lateral pulldown, and leg press at an intensity controlled to 80% of 10RM. In the isolated foam rolling condition, foam rolling was performed unilaterally in two sets of 120 seconds for each quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf region. In the combined condition of strength training and foam rolling, foam rolling was conducted immediately after strength training, following the same descriptions as above. |

Measurement of systolic and diastolic blood pressure at rest and every 10 minutes after each protocol (Post-0, Post-10, Post-20, Post-30, Post-40, Post-50, and Post-60). Post-exercise hypotension was observed in the experimental conditions of isolated strength training at Post-50 (p < 0.001; d = -2.14) and Post-60 (p = 0.008; d = -2.88), and in isolated foam rolling at Post-60 (p = 0.020; d = -2.14). Post-exercise hypotension was also observed in the combined condition of strength training and foam rolling at Post-50 (p = 0.001; d = -2.03) and Post-60 (p < 0.001; d = -2.38). |

7 (high) |

| Monteiro et al. [29] | Examine the acute effects of different pre-strength training strategies on total training volume, maximum repetition performance, fatigue index, and blood pressure responses in recreationally strength-trained women. | 10RM test and retest for bench press 45°, front squat, lat pull-down, leg press, shoulder press, and leg extension. Strength Training = 80% of 10RM load with self-suggested rest interval. Foam Rolling and Stretching Exercise = Applied, unilaterally, in randomized order, in single set of 90s to the lateral torso of the trunk, anterior and posterior thigh, and calf regions. Aerobic Exercise = Walking on the treadmill with intensity between 30% and 60% of the heart rate reserve. Specific Warm-Up = Two sets of 15 repetitions with 40%10RM with 90s rest interval. Blood pressure was measured at baseline, Post-10, Post-20, Post-30, Post-40, Post-50, and Post-60 minutes. |

No significant reductions were observed for systolic and diastolic blood pressure with effect sizes magnitude ranging between trivial and large. | 7 (high) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).