1. Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes worldwide is alarmingly high and continues to rise rapidly, with type 2 diabetes (T2D) accounting for approximately 90% of cases (IDF, 2021). This condition is strongly associated with various cardiovascular diseases, particularly hypertension, which significantly increases cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Izar et al., 2022). Approximately 50% of individuals with T2D also have hypertension, making the management of both conditions essential for improving quality of life and reducing the risk of cardiocerebrovascular events (Strain & Paldánius, 2018).

Alongside diet and medication, exercise is widely recognized as a fundamental component in the management of T2D (ACSM, 2022; ADA, 2025). Both aerobic and resistance exercises are recommended as effective strategies (Pan et al., 2018; ACSM, 2022; ADA, 2025). While chronic exercise adaptations provide the most clinically significant benefits, understanding the acute effects of exercise is crucial for optimal training prescription. Only by assessing the immediate clinical responses to each session can safe and effective exercise recommendations be made.

A recent meta-analysis (de Almeida et al., 2025) demonstrated that continuous aerobic exercise reduced blood glucose levels by 26.7 mg/dL, while interval aerobic exercise resulted in a more substantial reduction of 47.92 mg/dL one minute after exercise, with effects persisting for up to 30 minutes post-session. In contrast, resistance exercise led to a reduction of 21.26 mg/dL one minute after the session; however, this effect was not sustained beyond 10 minutes.

The acute glycemic effects of aerobic exercise have been widely studied, with its safety and efficacy well established in individuals with T2D. However, less is known about the acute effects of resistance exercise, particularly regarding training variables that may influence clinical responses, such as exercise selection. Multi-joint exercises, which engage larger muscle groups, may have a greater impact on metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes compared to single-joint exercises. While single-joint exercises are easier to perform and require less technical skill, multi-joint exercises may elicit superior functional and glycemic benefits despite their increased complexity. Nonetheless, this hypothesis remains unclear.

Regarding acute blood pressure responses, Mello et al. (2016) found that multi-joint resistance exercises induced lower cardiovascular overload, measured by the double product, and greater post-exercise hypotensive effects compared to single-joint resistance exercises in trained young men.

Although major exercise guidelines for T2D (ACSM, 2022; ADA, 2025) recommend resistance training involving large muscle groups, further investigation is needed to clarify the acute glycemic and blood pressure responses to single- and multi-joint resistance exercises, particularly through randomized controlled crossover trials. Thus, the aim of the present study is to analyze the acute glycemic and blood pressure responses to single- and multi-joint resistance exercise sessions in individuals with T2D. We hypothesize that the effects of the multi-joint session will be more pronounced.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This study is a randomized crossover clinical trial involving individuals with T2D who participated in three sessions: two experimental sessions—one comprising single-joint resistance exercises and the other comprising multi-joint resistance exercises—and a control session without exercise. The trial is registered in the Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry System (code RBR-102jnmyx).

2.2. Participants

Individuals with T2D of both sexes, aged 18 years or older, were included in the study. Participants met the following inclusion criteria: a diagnosis of T2D confirmed by blood test or the use of antidiabetic medication, ongoing endocrinological treatment, and a pre-exercise glycemic range between 90 and 250 mg/dL to ensure safe exercise participation (BRASIL, 2023). The exclusion criteria for this study included the presence of severe autonomic neuropathy, severe peripheral neuropathy or a history of foot injuries, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, decompensated heart failure, peripheral amputations, musculoskeletal impairments preventing the execution of resistance exercises, and the inability to travel for study visits. Recruitment was conducted via social media advertisements by the Grupo de Pesquisa em Exercício Clínico (GPEC) and researchers involved in the study. Additionally, a list of patients with T2D obtained from an outpatient clinic was utilized, and individuals who had previously expressed interest in research participation were contacted via a messaging application, where they were provided with information about the study procedures.

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

The order of the training sessions was randomized using the website

www.randomizer.org in a counterbalanced manner by a researcher not directly involved in the experimental procedures. Due to the nature of the study, blinding of the evaluators was not possible, as they were responsible for administering the intervention and collecting data in each session.

2.4. Experimental Procedures

The experimental procedures consisted of five visits. During the first visit, participants were informed about the research procedures, benefits, and potential risks. They had the opportunity to clarify any questions before signing the Free and Informed Consent Form. Following this, an anamnesis form was administered to collect data for sample characterization, including sociodemographic information, health status, physical activity habits, and medication use. Subsequently, blood pressure, blood glucose levels, and anthropometric measurements (height, body mass, and waist circumference) were assessed. During the second visit, participants were familiarized with the exercise sessions, and the external load for each exercise was determined. The third, fourth, and fifth visits involved the randomized implementation of the experimental and control sessions, with a minimum interval of 48 hours between sessions. In the experimental sessions, blood glucose and blood pressure were measured before and after the intervention (immediately, as well as 15 and 30 minutes post-exercise). At the end of each exercise session, the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and affective valence were recorded.

2.5. Interventions

Each exercise session lasted approximately 35 minutes and was divided into a joint warm-up (five minutes) and a main session (approximately 30 minutes). The main session consisted of five resistance exercises, with one session focused on single-joint exercises and another on multi-joint exercises, performed on different days. The intervention team consisted of three physical education professionals with prior training in working with clinical populations. The structure of the exercise sessions is presented in

Table 1.

2.6. Control Session

In the control session, participants remained at rest for 10 minutes, after which their blood pressure and glycemia were assessed. They stayed in the gym for the same duration as the exercise sessions, moving around the weight training equipment without engaging in any exercises. Following this period, participants underwent the same data collection procedures as in the experimental sessions.

2.7. Anthropometric Measurements

Anthropometric assessments were conducted to characterize the study sample. Body mass was measured using a Sohenle® (Germany) scale with a resolution of 50 grams, with participants wearing appropriate clothing for the measurement. Height was determined using a Sanny® (Brazil) stadiometer, with individuals standing barefoot. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated based on these measurements. Waist circumference was assessed using a non-elastic measuring tape positioned at the midpoint between the anterior superior iliac crest and the last rib.

2.8. Internal Load

The internal load of each exercise session was quantified using the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale adapted from Borg (Foster et al., 2001). This assessment aimed to estimate exercise intensity after each session, and participants were individually asked to report their perceived exertion at the end of each session.

2.9. External Load

The external load was determined based on the weight used for each exercise, which was established during the familiarization phase, considering the individual capabilities of each participant.

2.10. Affective Response

Affective valence was assessed using a validated scale to evaluate participants’ subjective experience of pleasure or displeasure in response to physical exercise. The scale, proposed by Hardy and Rejeski (1989), ranges from -5 to +5, where -5 represents “very bad” and +5 represents “very good.” Intermediate descriptors include: -3 = bad, -1 = reasonably bad, 0 = neutral, +1 = reasonably good, and +3 = good.

2.11. Capillary Glycemia – Primary Outcome

Capillary glycemia was measured by a trained research team member using an Accu-Check glucometer (Performa model, Roche, Portugal). Only participants with pre-exercise glycemia levels between 90 and 250 mg/dL were permitted to begin the training sessions.

2.12. Blood Pressure Assessment

Blood pressure was measured by a trained professional using an OMRON device (model HEM 7122) with appropriately sized cuffs based on participants' arm circumferences, following the guidelines of the Brazilian Hypertension Guidelines (Barroso et al., 2020). Participants remained seated in a calm environment for five minutes before the measurement. Only individuals with systolic and diastolic blood pressure values below 160 mmHg and 105 mmHg, respectively, were allowed to commence the exercise sessions.

2.13. Adverse Events Monitoring

The research team was trained to observe, interview, and document any adverse events occurring during the sessions.

2.14. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Participants at UFSC (CEPSH/UFSC) under protocol number 5.486.869. All participants were informed about the research procedures, potential risks, and benefits, and they were explicitly advised of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

2.15. Data Analysis

The sample size calculation was based on unpublished data from the GPEC, estimating a mean difference of 9 mg/dL in glycemic reduction favoring the multi-joint exercise session. The calculation was performed using G*POWER 3.1 software, assuming a significance level of 0.05, a statistical power of 80%, and a correlation coefficient of 0.5. The resulting sample size was 14 individuals. Descriptive data are presented as mean and standard deviation, while inferential results are reported as mean and standard error. Differences between pre- and post-intervention measurements and between sessions (time effect, session effect, and time*session interaction effect) were analyzed using the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) method. Multiple comparisons were conducted using the LSD post-hoc test. For nonparametric data, the Wilcoxon test was applied. The significance level was set at 5%, and all analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 23.0.

3. Results

The main characteristics of the participants are present in

Table 2. The major part of the sample was middle-aged women, with overweight and hypertension.

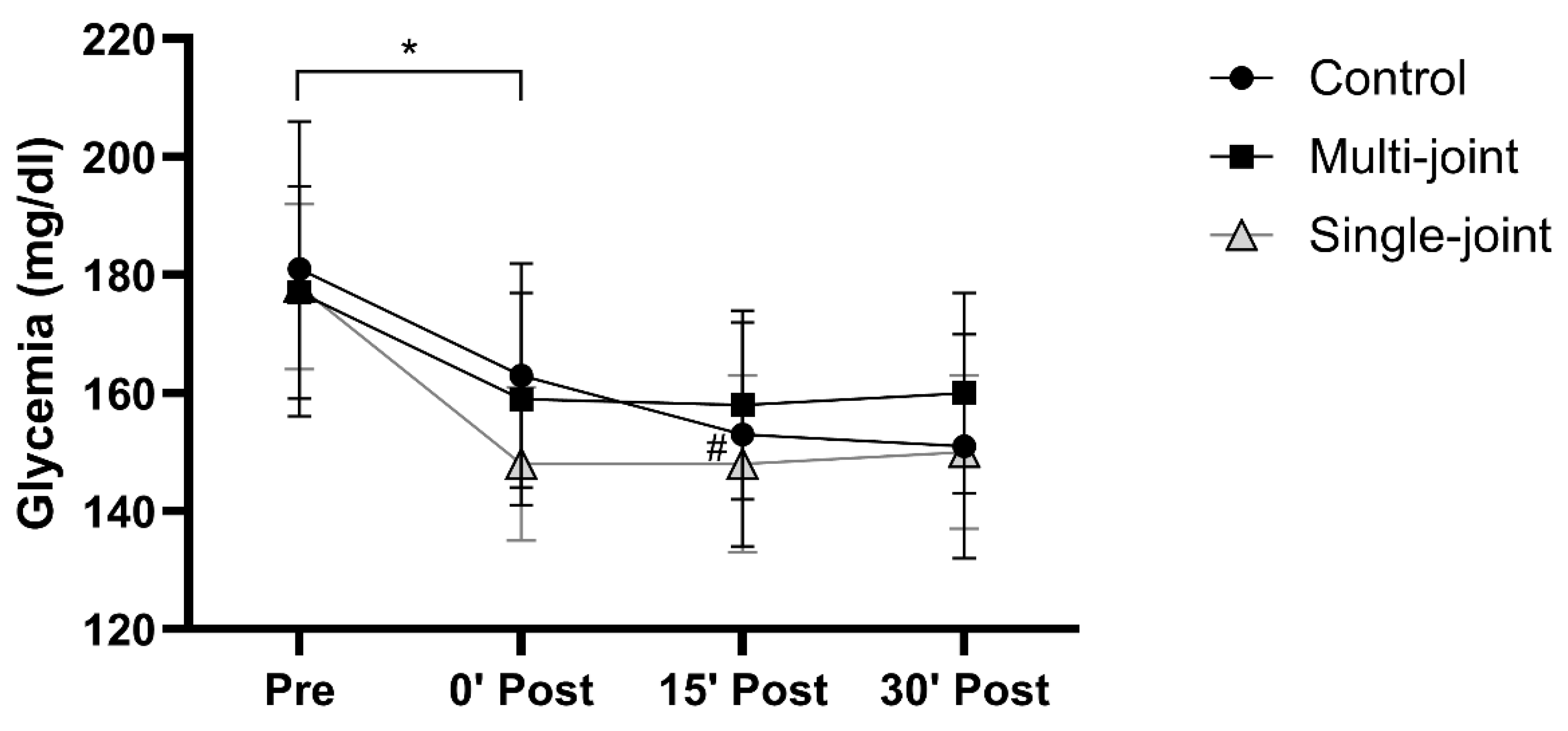

Regarding glycemia, only an isolated time effect (p<0.001) was found (

Figure 1). Both experimental sessions presented significant glycemic reductions immediately after the sessions (multi-joint: -17 mg/dl; single-joint: -29 mg/dl), with these values remaining similar up to 30 minutes after the sessions. The control session presented a glycemic reduction immediately after exercise (-18 mg/dl), which increased 15 minutes later (-29 mg/dl), stabilizing up to 30 minutes after the session.

Table 3 present the results of the blood pressure. Regarding systolic blood pressure, both exercise sessions increased the values immediately after the session, returning to baseline values 15 minutes after sessions, remaining similar until 30 minutes after the sessions. Interestingly, only the multi-joint session presented values immediately after the session higher than those found in the control session in this same time. Regarding diastolic blood pressure, in the multi-joint session the values 15 min post-session were higher than the values immediately post-session. In the single-joint session no changes were found along of time however its 0’post session values were superior to 0’ post-session values of the multi-joint session. Already in the control session, the 15 and 30 min post-session values were higher than the pre-session values, and 30’ post session was also superior to multi-joint session value in the same time.

The exercise sessions presented similar RPE-session and affectivity (

Table 4).

No adverse events related to exercise occurred in any session. When participants arrived with glycemic or blood pressure values above the permitted range for physical activity, the intervention team provided appropriate assistance and waited for the values to normalize before proceeding or rescheduled the session if necessary.

4. Discussion

Glycemic levels showed similar reductions immediately after exercise across all sessions, with these effects maintained throughout the evaluation period and no superiority of experimental sessions over the control session. Regarding systolic blood pressure, only the experimental sessions led to the expected immediate post-exercise increase, making these values higher than those in the control session at the same time point. Diastolic blood pressure was higher immediately after the single-joint session compared to other sessions. Fifteen minutes post-exercise, diastolic blood pressure increased in the multi-joint session compared to immediately post-exercise, while in the control session, values increased at 15 and 30 minutes post-session. Consequently, 30 minutes post-exercise, diastolic blood pressure was lower in the multi-joint session compared to the control session (-4.47 mmHg), indicating post-exercise hypotension (HPE).

Regarding glycemic response, this study refutes the hypothesis that multi-joint exercises lead to superior glycemic reduction compared to single-joint exercises. Additionally, no differences were found between the experimental and control sessions. From a practical perspective, this finding is relevant, as the Diabetes Society Guidelines (ACSM, 2022; ADA, 2025) recommend resistance training with two to three sets for large muscle groups, suggesting that both exercise types may provide acute glycemic benefits. Given the limitations many individuals with T2D face when starting more complex exercise programs requiring greater motor coordination, single-joint exercises may serve as a viable alternative. However, despite these practical considerations, the lack of difference in glycemic response between control and exercise sessions suggests that the observed reductions may not be solely attributable to the exercises performed.

Although pre-session glycemic values were similar across conditions, the lack of dietary control before sessions may have influenced glycemic behavior, potentially explaining reductions observed in the control session. Similarly, Ferrari et al. (2021) reported no differences in glycemic response between body-weight resistance training and a control session in middle-aged adults with hypertension.

For systolic blood pressure, the immediate post-exercise increase was expected due to increased cardiac output but remained within safe limits and subsequently decreased over time. The absence of post-exercise hypotension (PEH) could be attributed to the relatively low pre-exercise values (~125 mmHg) and the short post-exercise monitoring period (30 minutes). Ferrari et al. (2021) reported lower systolic blood pressure values compared to a control session only 45 minutes post-exercise, while Silva et al. (2020) found significant differences in diastolic blood pressure 30 minutes post-session. In the present study, despite the lack of significant differences between control and exercise sessions, systolic blood pressure in the control condition showed an increasing trend at 30 minutes post-session, with mean differences of 5.53 mmHg and 5.00 mmHg compared to the multi-joint and single-joint sessions, respectively—both of which exhibited a decreasing trend.

For diastolic blood pressure, there was no immediate increase post-exercise, indicating cardiovascular safety. However, in the control session, despite participants moving between equipment to minimize prolonged sedentary behavior, diastolic blood pressure increased at 15 and 30 minutes post-session. This led to a significant difference between the multi-joint and control sessions, a notable finding in line with previous studies (Silva et al., 2020; Ferrari et al., 2021) using multi-joint resistance exercises. The absence of a significant reduction in diastolic blood pressure from pre- to post-exercise is likely due to the already low baseline values (70–74 mmHg), leaving little room for further reduction (Carpio-Rivera et al., 2016).

Regarding internal load, measured by RPE-session, both exercise sessions were classified as moderate to somewhat difficult, aligning with recommended intensity levels. These intensities appear safe and potentially effective, particularly in the initial stages of training programs. However, for a greater cardiometabolic impact from resistance training alone, a higher training volume (e.g., additional exercises) may be necessary.

Another secondary variable assessed was affectivity, with both sessions yielding a median rating of 5 ("very good"), suggesting that participants enjoyed both exercise modalities. This is an important factor, as enjoyment of exercise can enhance adherence to regular physical activity, particularly in clinical populations (De Oliveira Segundo et al., 2014).

Limitations and Strengths

The primary limitations of this study include the lack of dietary control before sessions and the short post-session monitoring period. However, notable strengths include the complementary evaluation of RPE-session and affectivity and the controlled crossover design with randomized session order.

5. Conclusion

Both experimental and control sessions resulted in glycemic reductions, with no evidence of exercise-induced superiority or differences between the two exercise modalities. Regarding blood pressure, PEH was observed only for diastolic blood pressure at 30 minutes post-session in the multi-joint session, with values lower than those in the control session.

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 10th ed. 2021.

- Izar M, Fonseca F, Faludi A, Araújo D, Valente F, Bertoluci M. Manejo do risco cardiovascular: dislipidemia. Diretriz Oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. 2022. DOI: 10.29327/557753.2022-19. ISBN: 978-65-5941-622-6.

- Strain, W.D.; Paldánius, P.M. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaley JA, Colberg SR, Corcoran MH, Malin SK, Rodriguez NR, Crespo CJ, et al. Exercise/Physical Activity in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Statement from the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022;54(2):353-68. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002800.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of care in diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48 (Suppl 1).

- Pan B, et al. Exercise training modalities in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):1-14.

- de Almeida JA, Batalha APDB, Santos CVO, Fontoura TS, Laterza MC, da Silva LP. Acute effect of aerobic and resistance exercise on glycemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Phys Ther. 2025;29(1):101146. [CrossRef]

- Mello TL, et al. Treinamento de força em sessão com exercícios poliarticulares gera estresse cardiovascular inferior a sessão de treino com exercícios monoarticulares. Rev Bras Cienc Esporte. 2017; 39:132-40.

- Brasil. Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes 2023. Brasília: Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes; 2023.

- Foster C, et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(1):109-15.

- Hardy CJ, Rejeski WJ. Not what, but how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11(3):304-17.

- Barroso WKS, et al. Diretrizes brasileiras de hipertensão arterial–2020. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;116(3):516-658.

- Ferrari R, et al. Acute effects of body-weight resistance exercises on blood pressure and glycemia in middle-aged adults with hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2021;43(1):63-8.

- Silva AL, et al. Acute effect of bodyweight-based strength training on blood pressure of hypertensive older adults: A randomized crossover clinical trial. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2021;43(3):223-9.

- Carpio-Rivera E, et al. Acute effects of exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analytic investigation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016; 106:422-33.

- De Oliveira Segundo VH, Felipe TR, Knackfuss MI. Efeito do tempo de intervalo sobre o efeito hipotensor pós-exercício de uma sessão de treinamento com pesos regulada pelo afeto em idosos. EFDeportes. 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).