Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Parametric Partial Differential Equations

2.2. PDE Setting

This is an example of a quote.

3. Algorithm

3.1. Setting of Input Signal and Function Space

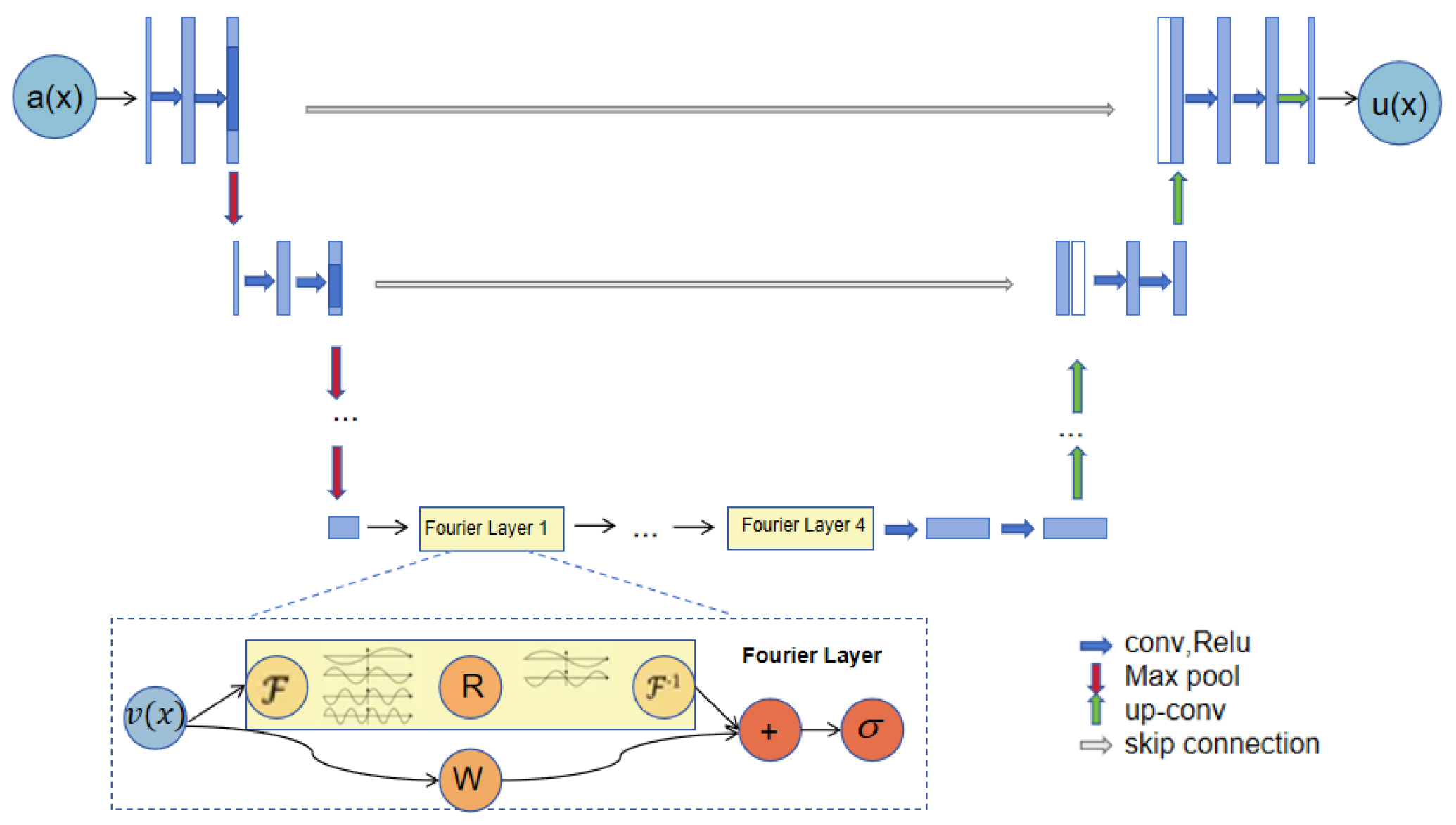

3.2. Structure Based on U - Net Neural Network and Fourier Neural Operator

4. Experiment

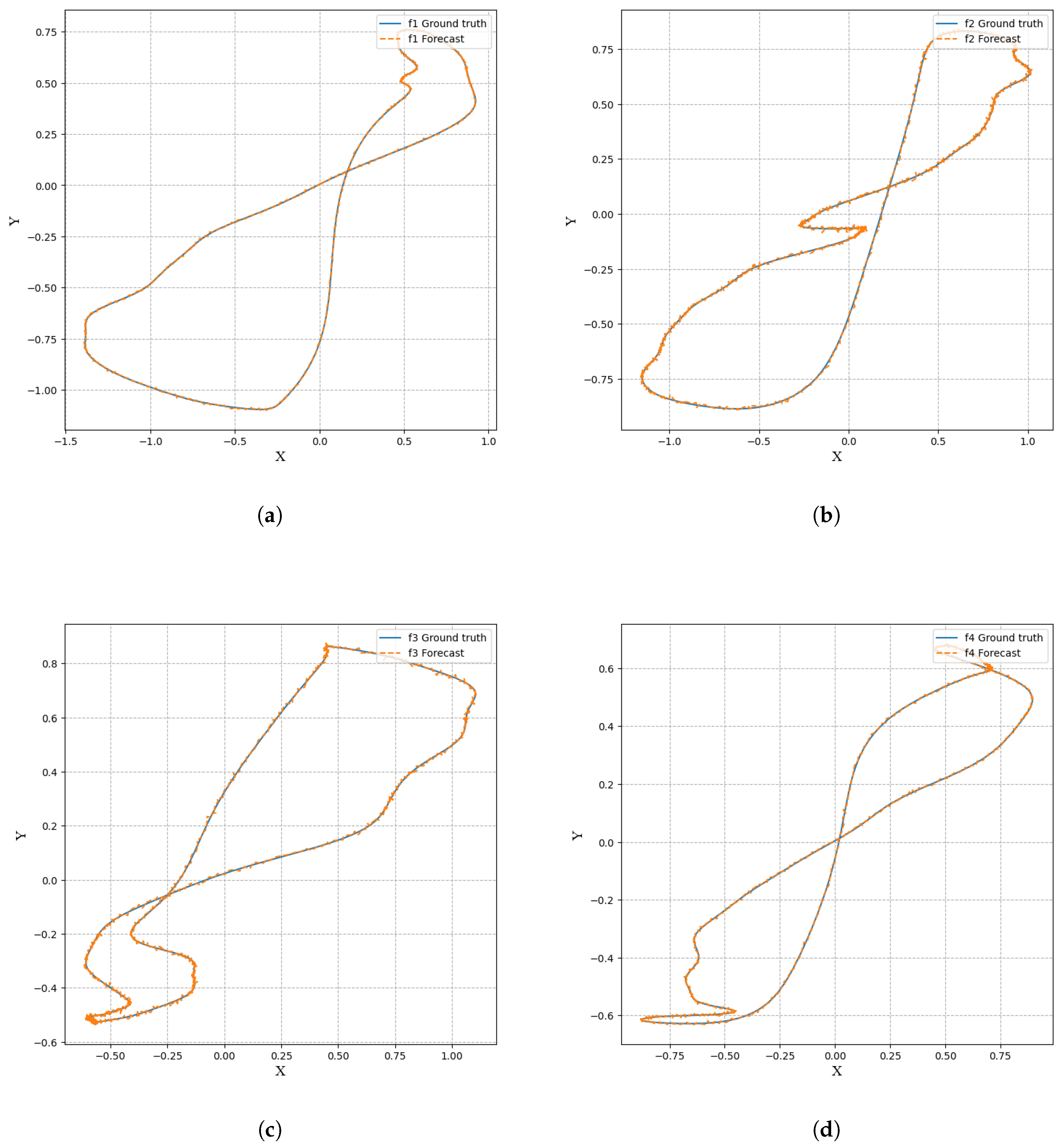

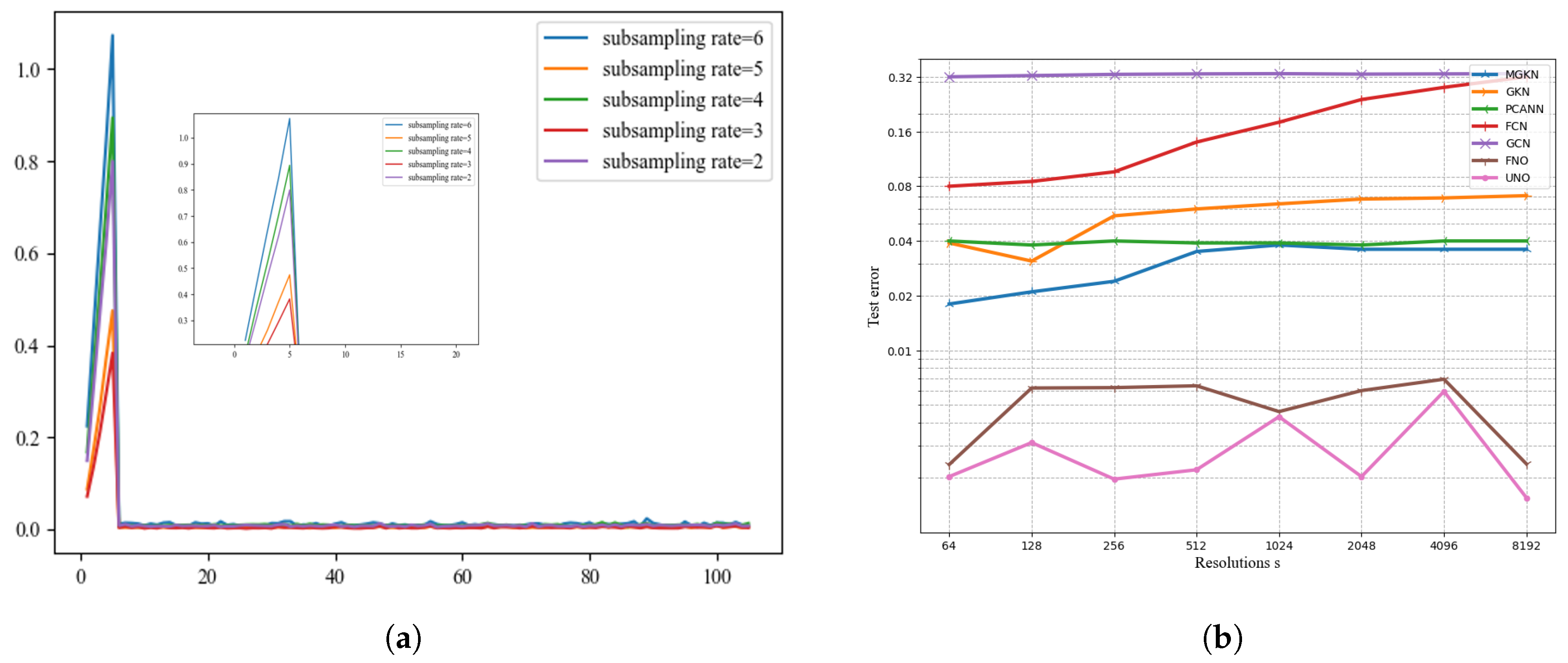

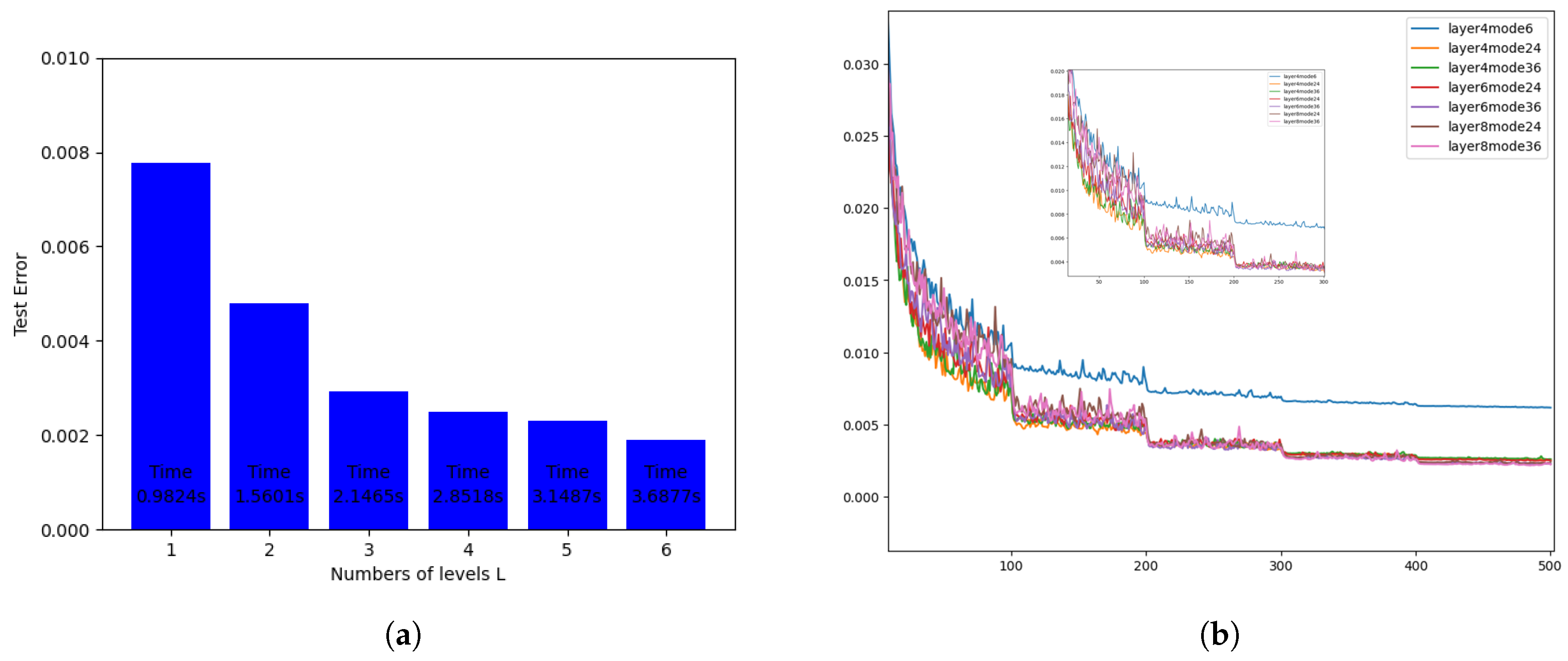

4.1. Burgers

| Network | s=64 | s=128 | s=256 | s=512 | s=1024 | s=2048 | s=4096 | s=8192 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGKN | 0.0187 | 0.0223 | 0.0243 | 0.0355 | 0.0374 | 0.0360 | 0.0364 | 0.0364 |

| GKN | 0.0392 | 0.0325 | 0.0573 | 0.0614 | 0.0644 | 0.0687 | 0.0693 | 0.0714 |

| PCANN | 0.042 | 0.0391 | 0.0398 | 0.0395 | 0.0391 | 0.0383 | 0.0392 | 0.0393 |

| FCN | 0.0827 | 0.0891 | 0.1158 | 0.1407 | 0.1877 | 0.2313 | 0.2855 | 0.3238 |

| GCN | 0.3211 | 0.3216 | 0.3359 | 0.3438 | 0.3476 | 0.3457 | 0.3491 | 0.3498 |

| FNO | 0.0024 | 0.0063 | 0.0063 | 0.0066 | 0.0048 | 0.0060 | 0.0069 | 0.0024 |

| UNO | 0.0021 | 0.0032 | 0.0020 | 0.0023 | 0.0045 | 0.0021 | 0.0060 | 0.0018 |

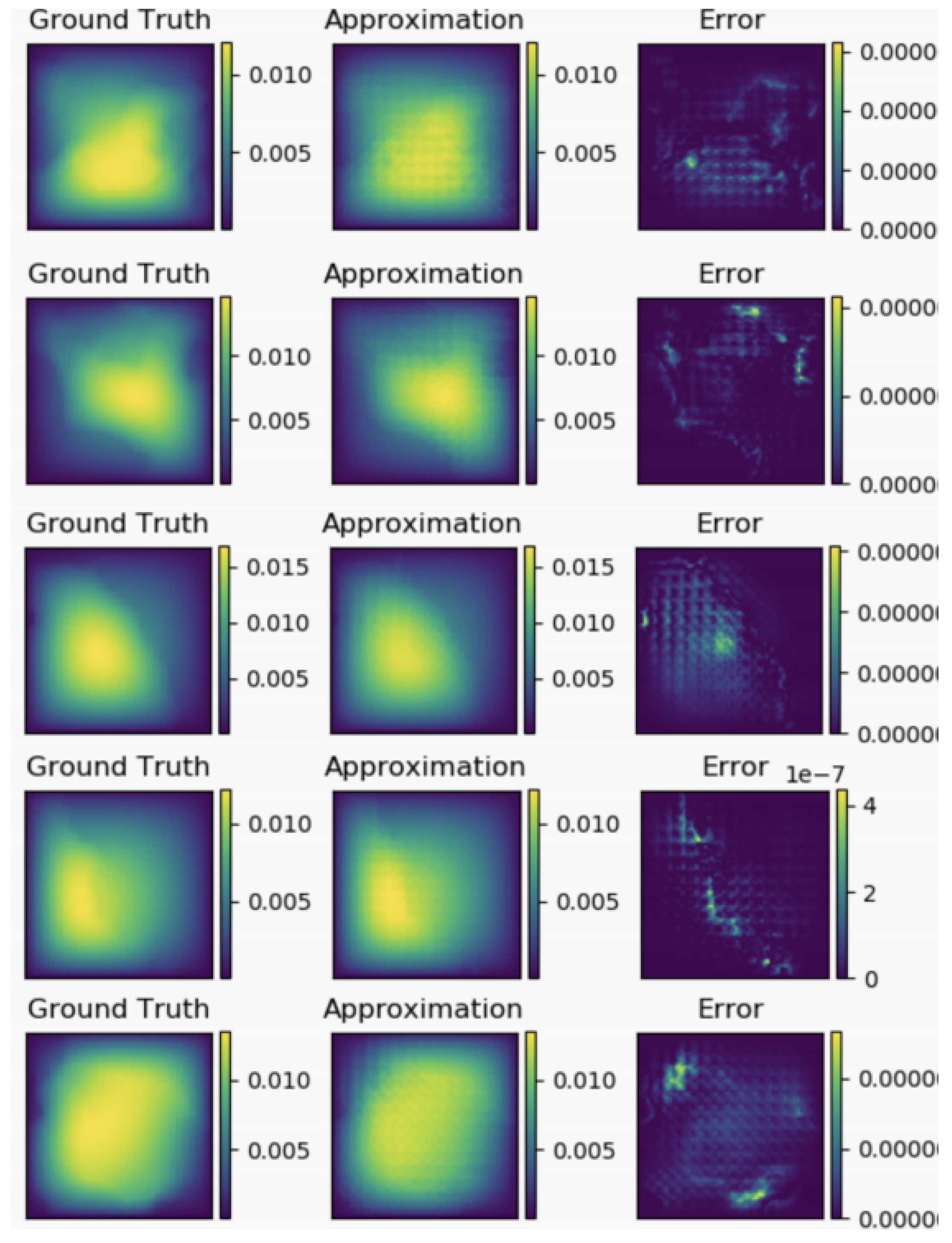

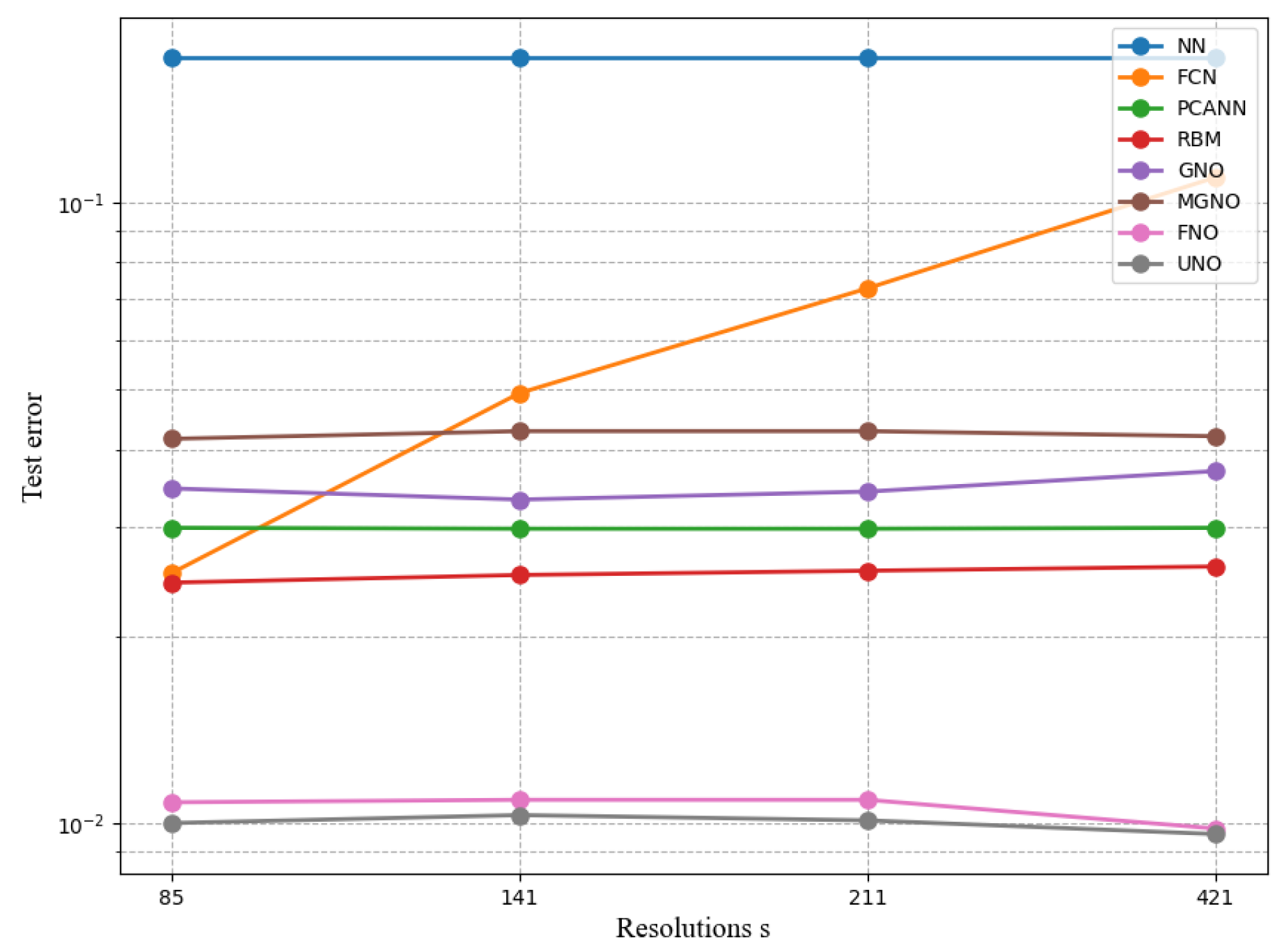

4.2. Darcy Flow

| Network | s=85 | s=141 | s=211 | s=421 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN | 0.1716 | 0.1716 | 0.1716 | 0.1716 |

| FCN | 0.0253 | 0.0493 | 0.0727 | 0.1097 |

| PCANN | 0.0299 | 0.0298 | 0.0298 | 0.0299 |

| RBM | 0.0244 | 0.0251 | 0.0255 | 0.0259 |

| GNO | 0.0346 | 0.0332 | 0.0342 | 0.0369 |

| MGNO | 0.0416 | 0.0428 | 0.0428 | 0.0420 |

| FNO | 0.0122 | 0.0124 | 0.0125 | 0.0099 |

| UNO | 0.0108 | 0.0109 | 0.0109 | 0.0098 |

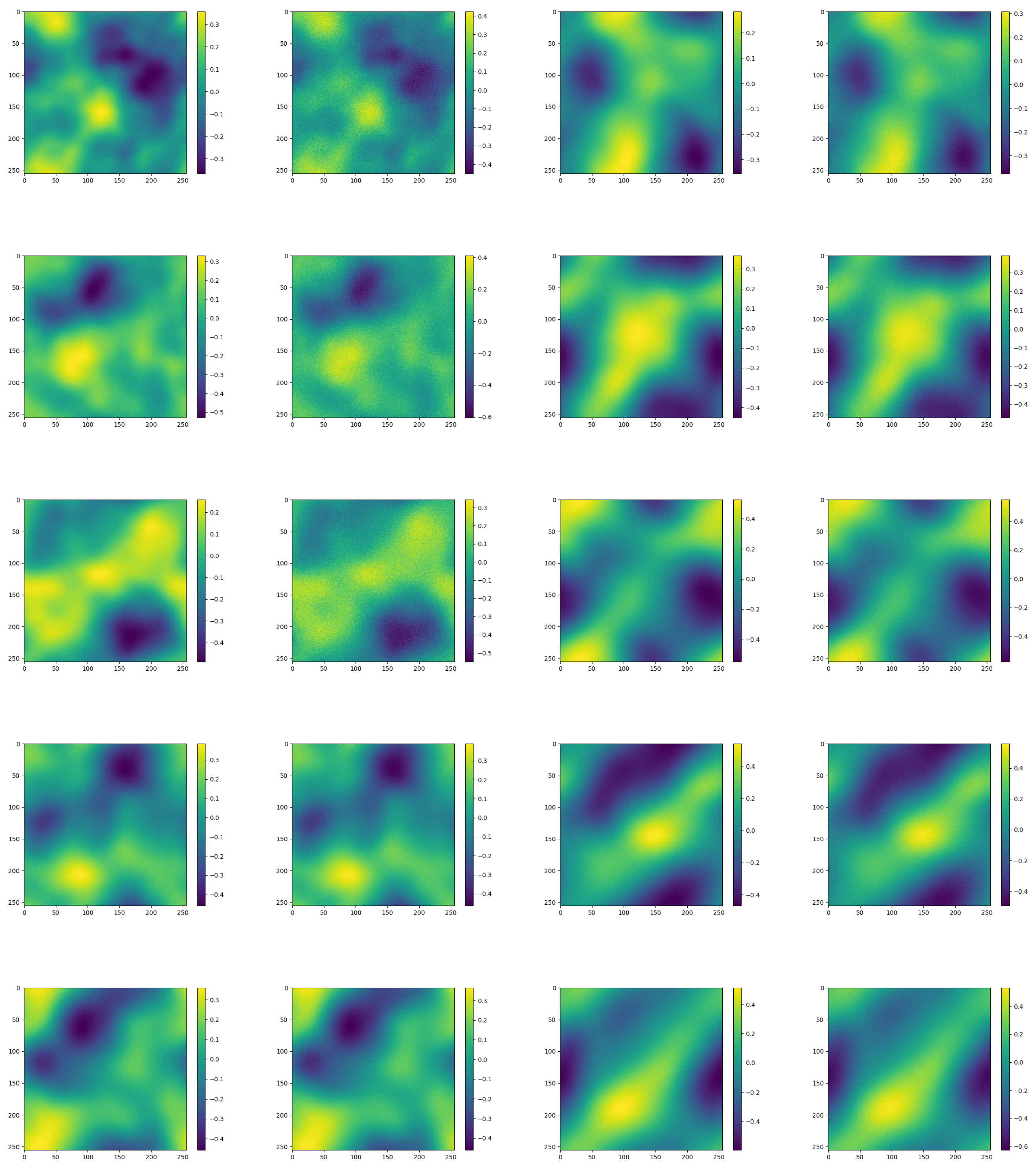

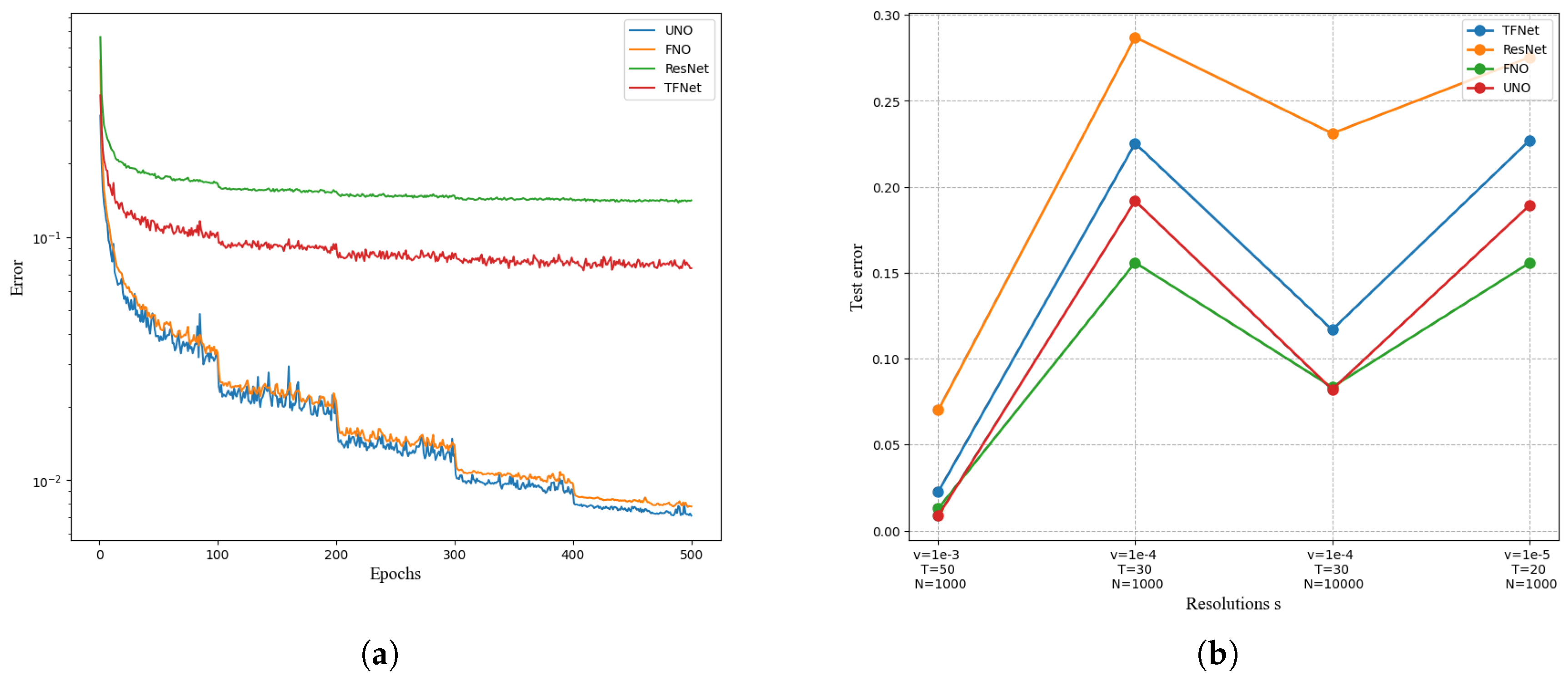

4.3. Navier-Stokes

| Network | total number of parameters |

each round of training takes time |

v=1e-3 T=50 N=1000 |

v=1e-4 T=30 N=1000 |

v=1e-4 T=30 N=10000 |

v=1e-5 T=20 N=1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNO | 414,517 | 38.99s | 0.0128 | 0.1879 | 0.0834 | 0.1856 |

| FNO | 6,558,53 | 45.80s | 0.0135 | 0.1551 | 0.0835 | 0.1524 |

| ResNet | 266,641 | 78.47s | 0.1716 | 0.2871 | 0.2311 | 0.2753 |

| TF-Net | 7,451,724 | 47.21s | 0.0225 | 0.2253 | 0.1168 | 0.2268 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Machine learning and computational mathematics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.14596, 2020.

- Han, Jiequn, and Arnulf Jentzen, Deep learning-based numerical methods for high-dimensional parabolic par- tial differential equations and backward stochastic differential equations, Communications in mathematics and statistics. 5.4 (2017): 349-380. [CrossRef]

- Weinan. E, Jiequn Han, and Arnulf Jentzen, Algorithms for solving high dimensional PDEs: from nonlinear Monte Carlo to machine learning, Nonlinearity. 35.1 (2021): 278. [CrossRef]

- Weinan E and Bing Yu, The deep Ritz method: A deep learning-based numerical algorithm for solving variational problems, Communications in Mathematics and Statistics. 6(1):1?12, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Turner, M. Jon, et al, Stiffness and deflection analysis of complex structures, Journal of the Aeronautical Sci- ences. 23.9 (1956): 805-823. [CrossRef]

- Richtmyer, Robert D., and Keith W. Morton, Difference methods for initial-value problems, Malabar. (1994). [CrossRef]

- Jameson, Antony, Wolfgang Schmidt, and Eli Turkel, Numerical solution of the Euler equations by finite volume methods using Runge Kutta time stepping schemes, 14th Fluid and Plasma Dynamics Conference. (1981).

- Dockhorn, T. A discussion on solving partial differential equations using neural networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.07200, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik K., Stinchcombe M., White H. Universal approximation of an unknown mapping and its derivatives using multilayer feedforward networks[J]. Neural Networks, 1990, 3(5): 551-560. [CrossRef]

- Lagaris I., Likas A., Fotiadis D. Artificial neural networks for solving ordinary and partial dif ferential equations[J]. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 1998, 9(5): 987-1000. [CrossRef]

- Lagaris I., Likas A., Fotiadis D. Artificial neural networks for solving ordinary and partial dif ferential equations[J]. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 1998, 9(5): 987-1000. [CrossRef]

- Winovich N., Ramani K., Lin G. Convpde-uq: Convolutional neural networks with quantified uncertainty for heterogeneous elliptic partial differential equations on varied domains[J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2019, 394: 263-279. [CrossRef]

- Long Z.C., Lu Y.P., Ma X.Z., Dong B. Proceedings of machine learning research: volume 80 PDE-net: Learning PDEs from data[M]. PMLR, 2018: 3208-3216.

- Long Z.C., Lu Y.P., Dong B. Pde-net 2.0: Learning pdes from data with a numeric-symbolic hybrid deep network[J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2019, 399: 108925. [CrossRef]

- LeCun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, et al. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition[J]. Proceedings of the IEEE, 1998, 86(11): 2278-2324. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Yuwei, et al, A multiscale neural network based on hierarchical matrices, Multiscale Modeling Simula- tion. 17.4 (2019): 1189-1213. [CrossRef]

- Hornik K, Stinchcombe M, White H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators[J]. Neural networks, 1989, 2(5): 359-366. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, M.; Henaff, M.; LeCun, Y. Fast training of convolutional networks through ffts. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.5851, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vahid K A, Prabhu A, Farhadi A, et al. Butterfly transform: An efficient fft based neural architecture design[C]//2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, 2020: 12021-12030.

- Kovachki, Nikola, et al, Neural operator: Learning maps between function spaces,arXiv preprint. arXiv:2108.08481 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Li, Zongyi, et al, Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations,arXiv preprint. arXiv:2010.08895 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kushnure D T and Talbar S N.Ms-Unet: A Multi-Scale Unet with Feature Recalibration Approach for Automatic Liver and Tumor Segmentation in Ct Images[J].Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics,2021,89:101885. [CrossRef]

- Isensee F, Kickingereder P, Wick W,et al.Brain Tumor Segmentation and Radiomics Survival Prediction: Contribution to the Brats 2017 Challenge[C]//Brainlesion: Glioma, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injuries: Third International Workshop, BrainLes 2017, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2017, Quebec City, QC, Canada, September 14, 2017, Revised Selected Papers 3, 2018.Springer,287-297.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).