1. Introduction

Infection of the foot is a common complication in patients with diabetes mellitus, and it can lead of significant morbidity and mortality. Healthcare interventions using antimicrobial therapy can effectively reduce morbidity, mortality, and associated economic costs [

1,

2,

3]. The addition of a 2% hyclate of doxycycline (DOX) solution applied locally to the standard care regimen for chronic foot ulcers has been reported to have a positive effect, particularly in reducing wound size during the first two weeks and promoting healing until complete closure [

4]. Membranes as transdermal patches are convenient and non-invasive method of drug delivery. It’s offers sustained release of antibiotic, maintaining constant drug levels in the topical area. This treatment improves patient compliance due to its ease of use and long-lasting effects [

5] making it easier for patients to adhere to the regimen in addition this topical healthcare may improve the tissue.

New membranes with carboxymethylcellulose/chitosan/glycerol-based can be used to deliver doxycycline to topical therapy of diabetic foot. DOX is a synthetic antibiotic derived from the tetracycline family, is a bacteriostatic agent that is used to treat gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria [

6], including

Staphylococcus aureus and

Escherichia coli [

7]. Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), a derivative of cellulose, is widely used in the manufacture of advanced dressing and drug delivery because of its many physicochemical properties, non-toxicity, high chemical stability, suitable biodegradability, and the possibility of drug release on the local tissue [

6,

8]. Chitosan (CHS) is a versatile natural copolymer derivate of chitin with mucoadhesive properties, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and antimicrobial activity to treatment of chronic and infectious wound healing [

9]. Loading glycerol (G) at CHS-based membranes can be used to design a drug delivery system with the appropriate mechanical and antibacterial properties [

10] to maintain intimate contact with the local tissue.

Considering the properties of doxycycline (DOX) and polymers used to treat of diabetic foot ulcers, in this investigation we proposed to fabricate a loaded DOX membrane based on these biopolymers. In this study, membranes of CMC, CHS and G containing DOX the physical-chemical characteristics and antibacterial activity against S. aureus, E. coli and S. mutans were evaluated. This treatment may offer an alternative with improve efficacy in the management chronic foot ulcers, promoting wound healing and improving patient compliance.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physical appearance and scanning electron microscopy analysis

Similar to CHS, CMC is a water-soluble anionic biopolymer with excellent physicochemical properties such as hydrophilic, non-toxic and, bio-adhesive [

11]. The

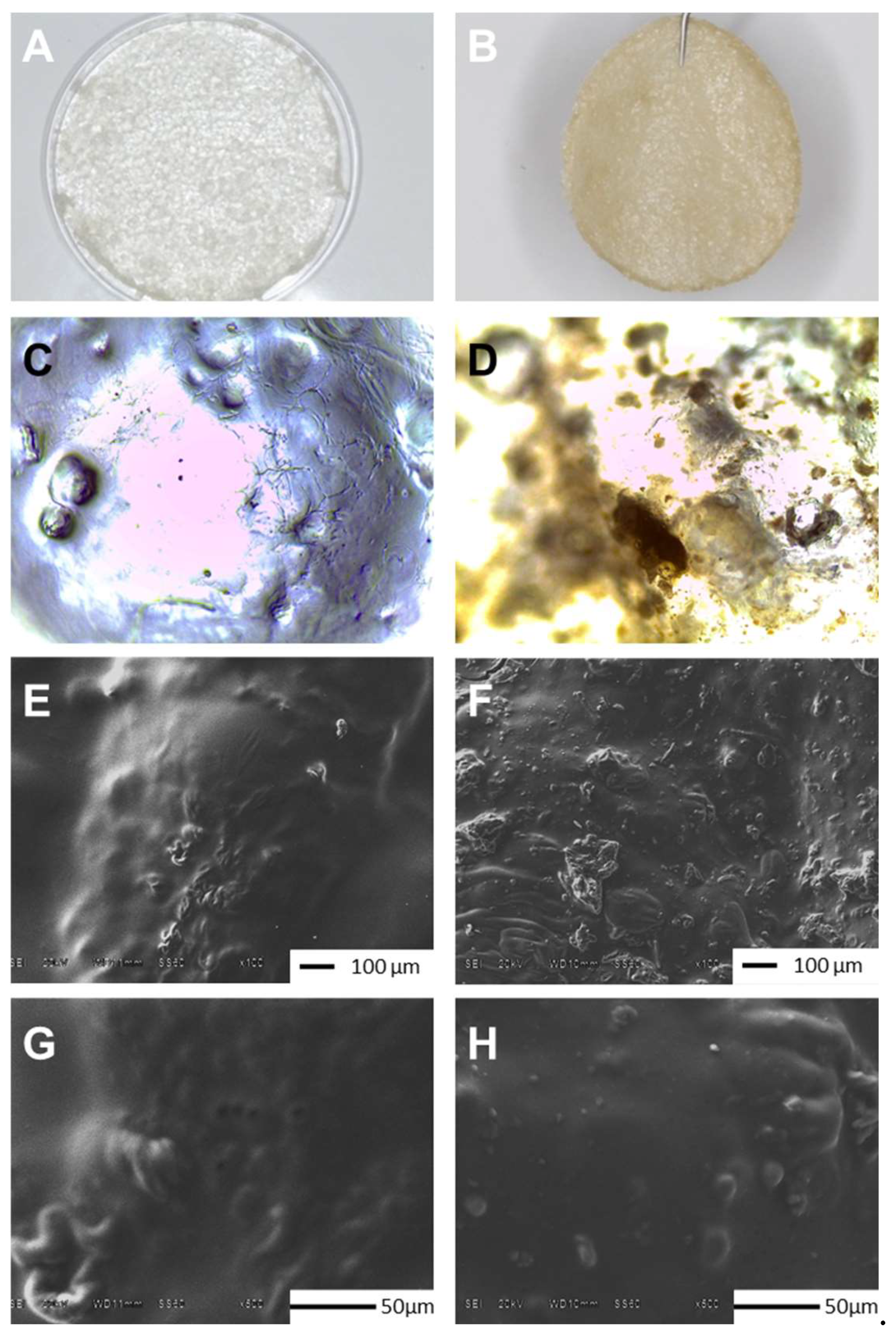

Figure 1 show images at three levels. In section A and B are shown photographs taken with HONOR X8b, Model LLY-LX3 where can observe that G (MControl) and Doxycicline-G (M-DOX) were integrated to membrane homogeneously (

Figure 1A y 1B, respectively). In the microphotographs taken with a Leica CC50 camera coupled to a Leica DM1000 optical microscope, MDOX presents a marron color (Figure D) due antibiotic presence, similar to was reported by Dinte

et al. [

12], but MControl is colorless (Fig C) as biopolymer membranes reported by other authors [

10,

13,

14]. Finally in the sections E, F, G and H, the top surface of the MControl and MDOX were examined by SEM after incubating at 37 °C for 72 h to investigate the influence of DOX on the membrane morphology. The surface morphology is a widely used technique to study the sub-microscopic details of different drug delivery systems of biopolymeric matrix.

Figure 1E shows the top surface of CMC/CHS/G membrane with the presence of few agglomerations of CMC with CHS in the matrix obtained by the synthesis method. The SEM images at 100X (

Figure 1F) of the surface morphology of CMC/CHS/G membrane with DOX at 1% suggests that prepared membranes loaded with DOX had irregular surface in contrast with unloaded membranes (

Figure 1E). DOX particles were visible in the form of dots (

Figure 1H) over the membrane, absent on the roughness surface of MControl (

Figure 1G), similar images were reported by Iqbal

et al. [

15]. DOX loaded hydrogel membrane prepared by Ulu

et al. [

11] also exhibited a similar morphology. This compact surface may be suitable for wound applications due to its no porous structure that inhibits the penetration of bacteria or liquid into the membrane [

16].

2.2. FTIR-ATR analysis

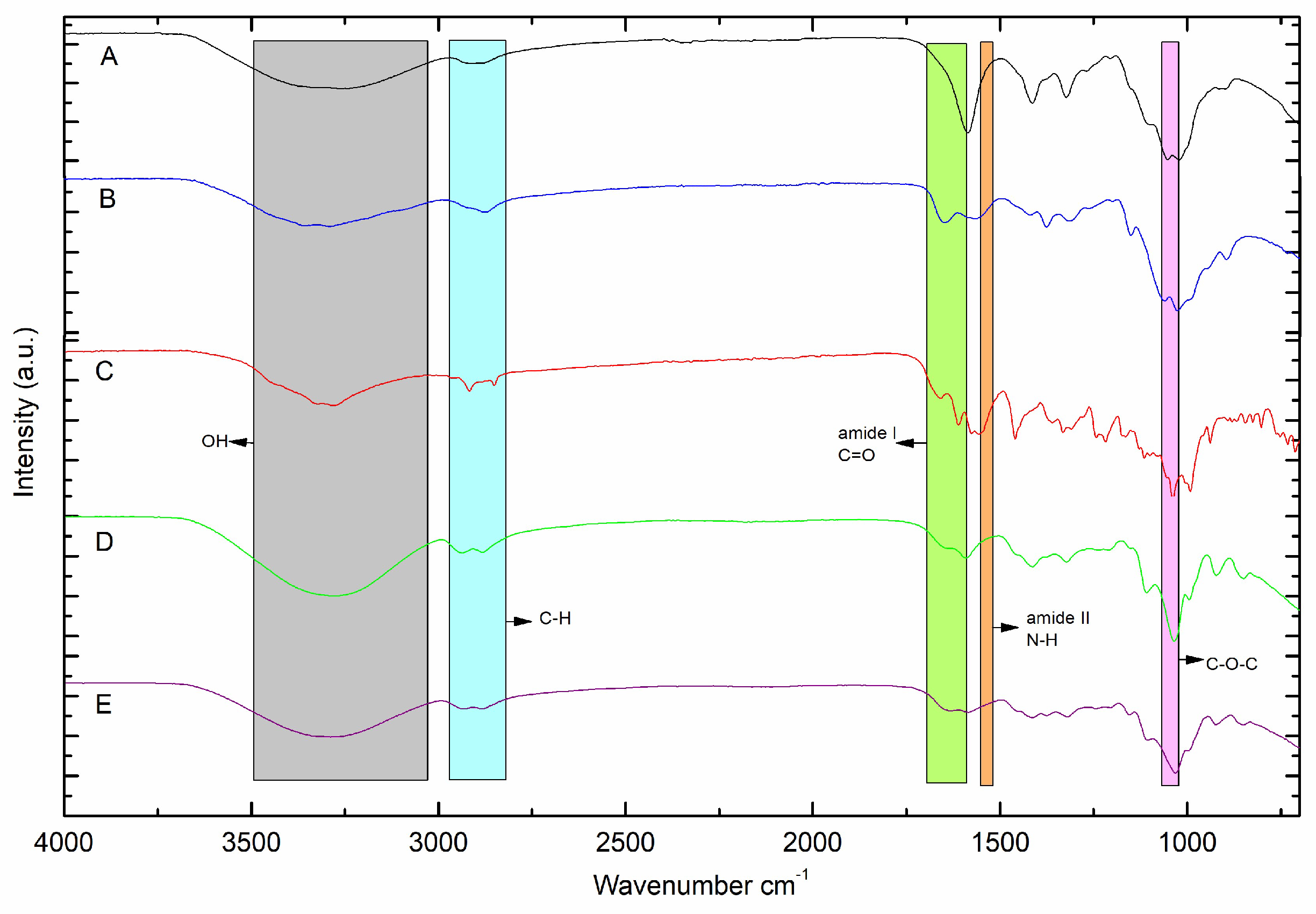

To analyze the interaction between the DOX functional group and the CMC/CHS/G membrane, the FTIR spectra of the CMC/CHS/G membrane and the CMC/CHS/G/DOX membrane were characterized (

Figure 2D, E). The FTIR spectrum of pure DOX exhibited characteristic absorption peaks between 3000 and 3500 cm

-1 (OH and OH), 1610 cm

-1 (amide band I), and 1576 cm

-1 (amide band II) (

Figure 2C), similar as reported by other authors [

6,

11,

17]. The characteristic IR bands of the dusty CMC show the O-H and stretching vibration of COO-bond at 3315 cm

-1, while dusty CHS-FTIR show bands at 3287 cm

-1 correspond to the stretching vibration of N-H, while peaks at 2,872 and 2,280 cm

-1 are assigned to the typical C-H stretching vibration in -CH

2 and -CH

3 of CHS, respectively. In addition, the peak at 1,648 cm

-1 corresponds to C=O stretching (amide I). The peak at 1,375 cm

-1 is assigned to C-N stretching bond (amide II), and the peak at 1,025 cm

-1 is assigned to the OH bond of CHS. When DOX was added to the CMC/CHS/G membrane, the peak shifted from 3253 cm

-1 (

Figure 2D) to 3276 cm

-1 (

Figure 2E), which indicates the N-H and the O-H bond. The weak stretching vibration bonds at 2883.52 and 2935.59 cm

-1 refer to the asymmetric C-H groups to MControl and MDOX. In the spectra of the doxy-loaded CMC/CHS/G membrane (

Figure 2E), characteristic peaks in the range of 1583.52 cm

-1 indicated the presence of DOX in the CMC/CHS membrane, similar as reported in the literature [

13,

15,

17]. The peaks at 1413.79 and 1031.89 cm

-1 in the CMC/CMC/G membrane (Fig D) and 1408.00 and 1028.03 cm

-1 in the CMC/CMC/G at 1% with DOX (Fig E) appeared to belong to the C-O and C-O-C groups, respectively.

2.3. Tensile properties

The mechanical properties of the membrane are critical for successful application in tissue as human skin. Mechanical compatibility between membrane and skin tissues is required to mimic the extracellular matrix. For this reason, it is desirable that the biopolymeric matrix have mechanical properties similar to those of human skin, providing good elasticity and adaptability to movement. Mechanical compatibility between membranes and human skin is required to mimic the extracellular matrix from wounds, providing good elasticity and adaptability to movement[

14]. In literature, the tensile strength of base linear stiffness of a hydrated acellular collagen scaffold was determined to be 0.023 ± 0.04 MPa but increased significantly when fibroblasts and keratinocytes remodeled the matrix for two weeks, 0.072 ± 0.021 MPa [

18] and elastic modulus is a crucial mechanical cue for cells [

19,

20]. The testing results of mechanical stability including tensile strength and elongation at break values are listed in

Table 1. It was seen that addition of DOX show tensile strength values similar to MControl and is proportional to the elongation values, 0.07 Mpa and 0.09Mpa, respectively. The maintenance of mechanical properties can be attributed to the low doses of DOX in the biopolymeric matrix of the membranes and demonstrate that these values are comparable to those of the skin.

2.4. Mass, thickness and roughness of the membrane

The mechanical properties of the membranes as mass, thickness and roughness also provide clues to the membrane structure. The mass values of membranes, as shown in

Table 1, demonstrated an increase in the mass of MDOX compared to MControl, 9.251 ± 0.688 mg and 6.051 ± 0.306 mg, respectively. Difference between membrane’s mass values were statistically significant (

p < 0.001). The increase mass values observed is due to DOX loading in CMC/CHS/G membrane. Meanwhile, the thickness values were of 604 ± 0.182 µm and 833 ± 0.134 µm, for the MControl and MDOX, respectively (

Table 1), with a difference statistically significant of

p < 0.005, were comparable with the measure thickness for grafted skin substitutes, 763 ± 80 µm and autograft (761 ± 74 µm) [

18]. This change thickness of membranes was caused by the adsorption of DOX by CMC and CHS combined as suggested by Tang

et al. [

13]. The increase of thickness obtained by loading MDOX is due to ionization states of doxycycline [

21] and polymers interactions as drug-delivery as hydrogen bond [

22]. The rough surface of the membrane can also be helpful for adherence to tissue and favors cellular activity [

23]. The incorporation of CMC and CHS in combination with G also induced a skin adhesive character in the membranes.

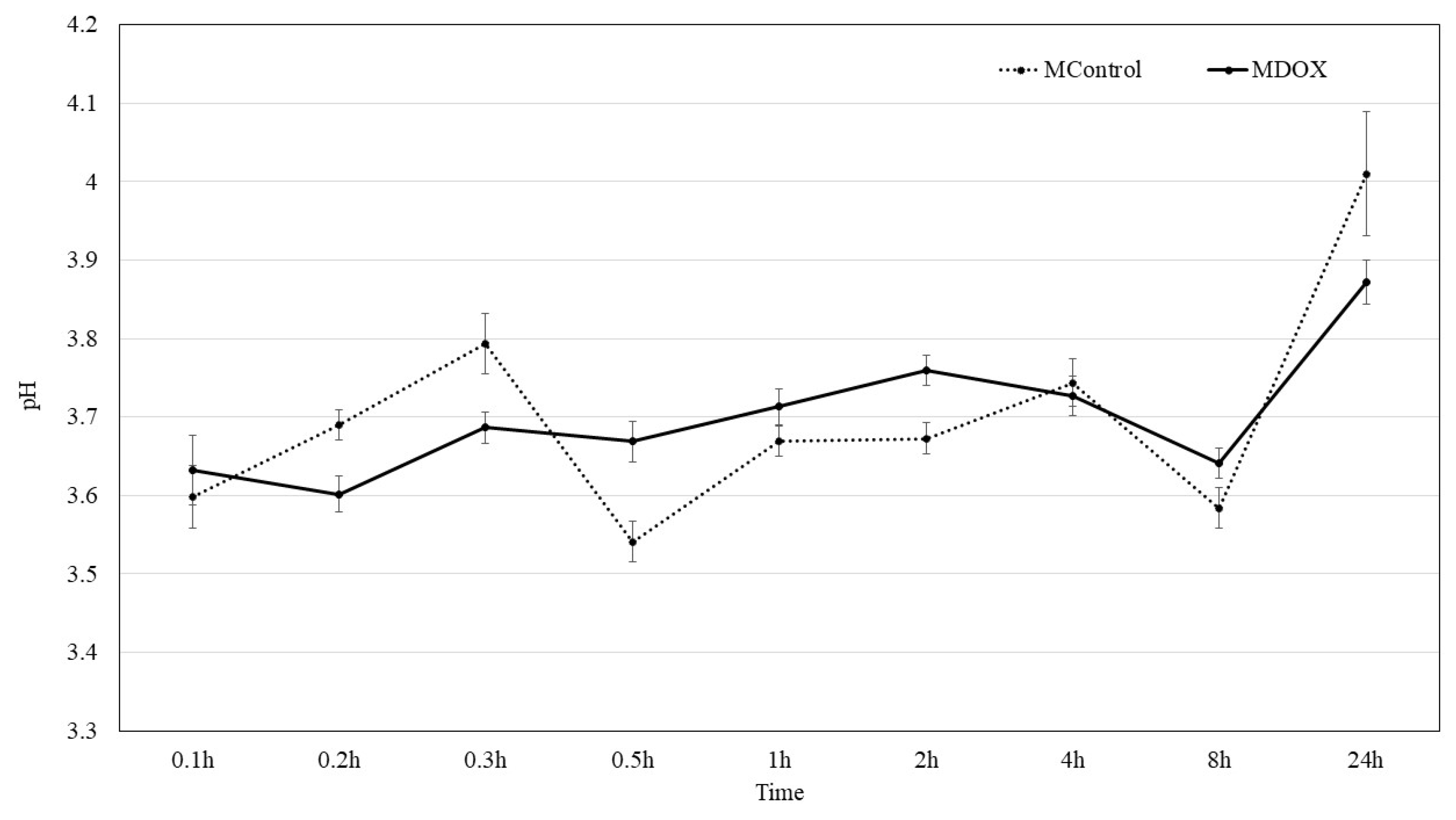

2.4. Surface pH kinetic

DOX existed in the form of DOX

+ at pH 2-3, while great number of H

+ ions competed with DOX

+ on the membrane surface leading the adsorption performance. The absorption efficiency of DOX from biopolymeric matrix of membranes is observed by pH change as reported Tang

et al. [

13]. The pH of surface membranes was 3.59 and 3.79 in buffer solution, to MControl and MDOX, respectively. Then a slowly increasing solution pH with time, from 3.6 to 4.1, suggest the release of DOX from the biopolymeric matrix as suggested by Tang [

13]. Although, drug release tests are necessary to evaluate the DOX release from membranes. The 3 – 4 pH range is different from that reported by Dinte [

12], because a pH range of 5.5 - 7.0 is being considered well tolerated to skin adhesive film. However, in a local pH under 4 by 8h, as show in

Figure 3, bacterial do not survive, and in a pH above 2.8 fibroblast survive, which allows fibroblast to use that local anion gap to proliferate and heal in a bacteria-free environment [

24].

2.4. Moisture sorption Water sorption behavior and Swelling capacity

CMC and CHS are commonly used as drug delivery system due to their strong hygroscopicity. Moisture sorption, water sorption behavior and swelling properties of natural materials rely on the nature of medium and swelling caused by solvent diffusion into material structure from extracellular medium. The stability of DOX could be affected by the membrane moisture sorption during storage as it is a humidity sensitive drug [

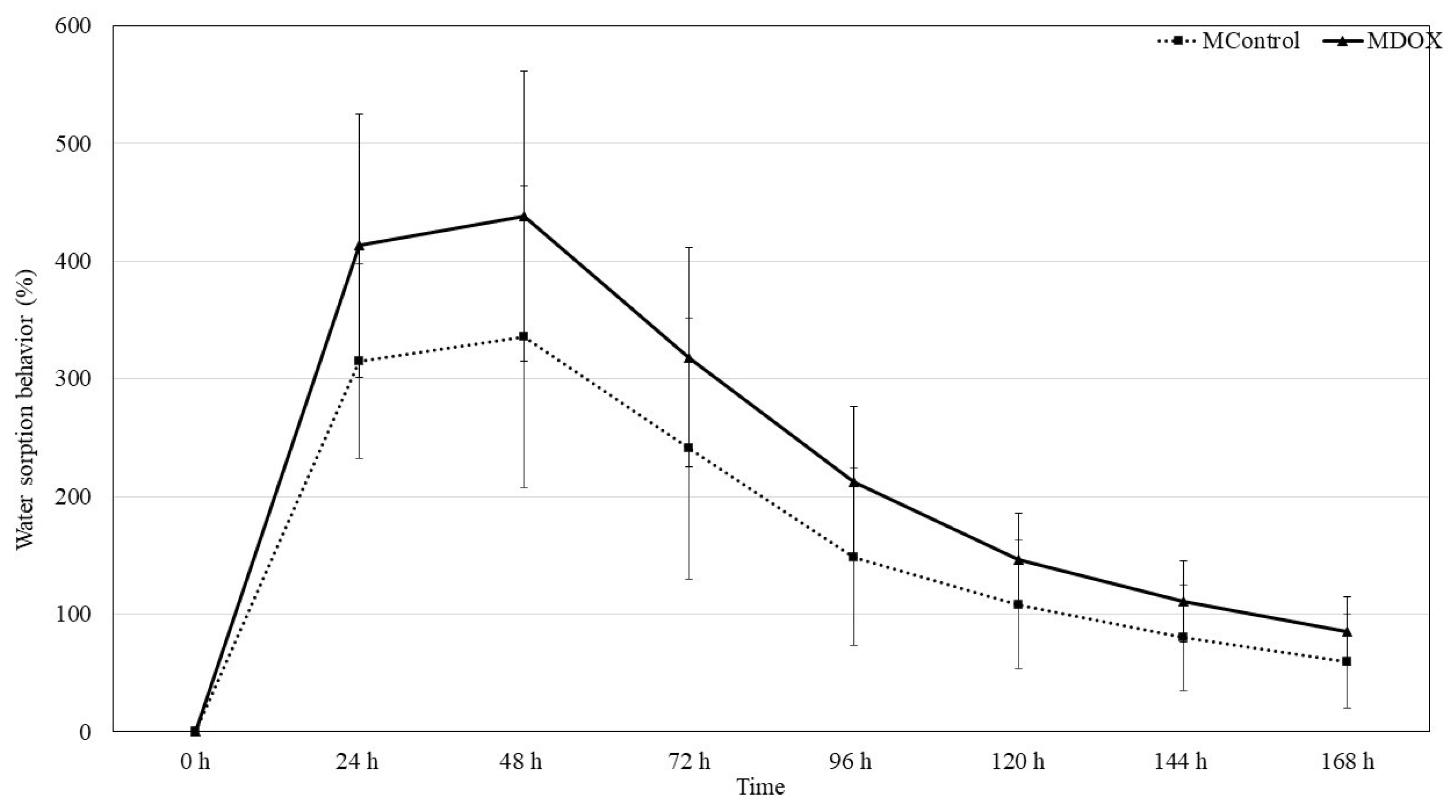

25]. The

Table 1 show the amount of moisture sorption weight gain for the membranes was recorded on the tenth day. The moisture sorption of theses membranes follows the order of MControl > MDOX, with values of 37.52 ± 6.54 and 205.01 ± 66.94, respectively. The difference is statistically difference significant (

p < 0.002). Similar results were reported by Peng

et al. [

25]. The introduction of charged chemical groups of Doxycycline into the biopolymeric matrix can alter some of its membrane characteristics. Therefore, the impact of charges on its wettability and water retention capacity was evaluated (

Figure 4). The loading-DOX membrane exhibited a higher moisture sorption (

Table 1). This amplification in hydrophilicity arose due to the incorporation of DOX at the biopolymeric matrix, probably the interaction of acid groups (-OH, -CONH

2, NMe

2), which led to a greater water affinity [

23]. Due to their high-water absorption capacity and biocompatibility these membranes have been used in dressing and drug delivery as trans-dermal systems [

26]. These membranes are cross-linked polymer networks swollen in a liquid medium. The embedded liquid acts as a selective filter, allowing the free diffusion of certain solute molecules, such as drugs, while the polymer network serves as a matrix to retain the liquid. The membranes may absorb from 10-20% (lower limit) up to thousands of times their dry weight in water [

27]. Swelling behavior of biopolymeric based membrane were tested in buffer media. Results indicated that MDOX showed best swelling that MControl, 0.538 ± 0.033 and 0.521 ± 0.051, respectively, with a statistical difference values,

p < 0.01 (

Table 1). These results indicate that 100 mg was an ideal amount of drug that was encumbered in a 17.5 mg/ml of CMC and 8.75 mg/ml of CHS powder polymer blended membrane.

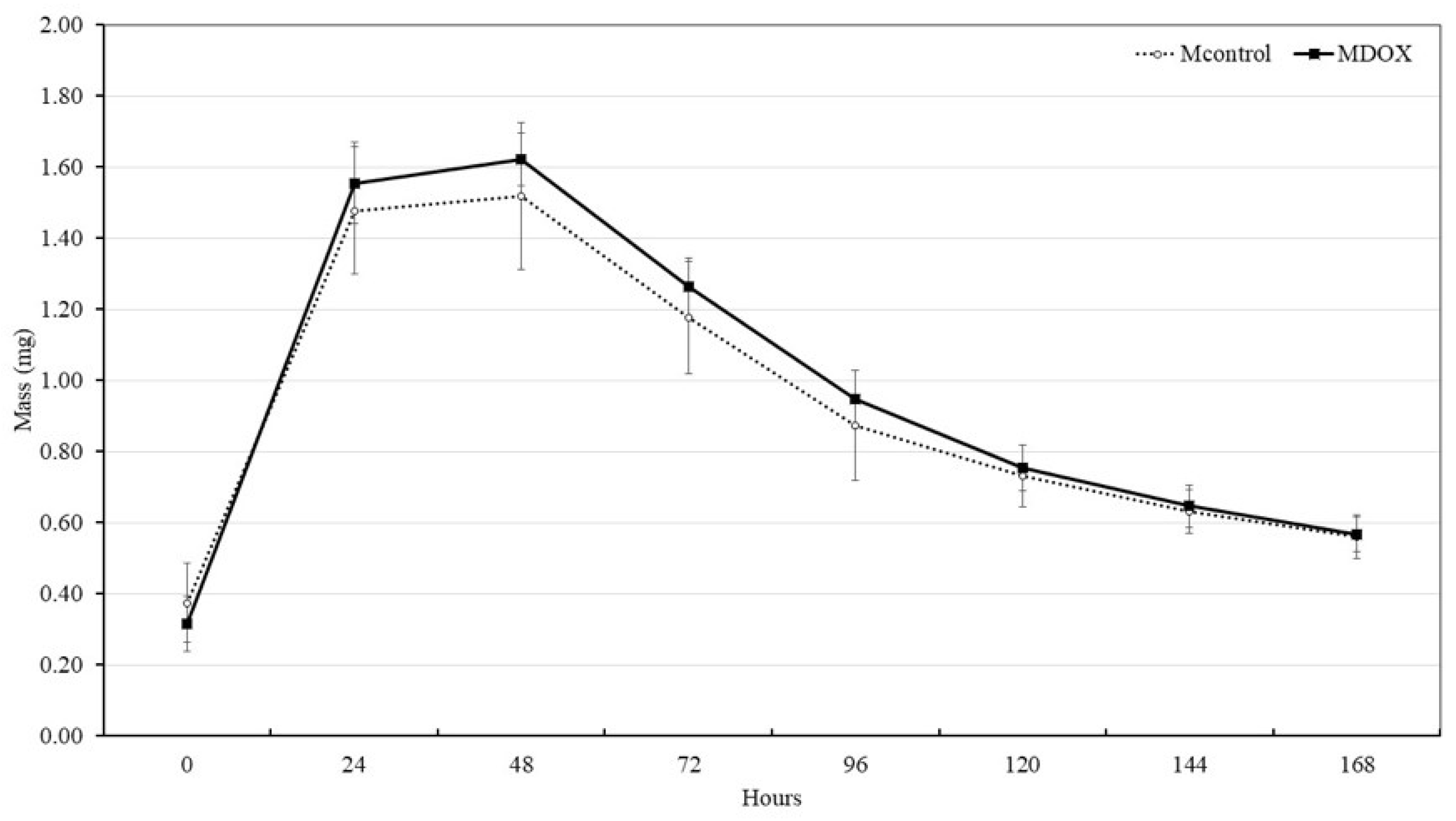

2.4. Disintegration or Biodegradability

Biodegradation potential of the membrane is important for the formation of extracellular matrix, and skin repair. In tissue engineering, the scaffold should not be completely removed until wound healing has finished. To evaluate the biodegradability potential of CMC/CHS/G membrane, SBF solution, which is the closest solution to the content of human blood plasma, was used. The degradation behavior of membrane was investigated according to time (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7-day) in SBF solution at 37 °C and the results are shown in

Figure 5. All the membranes did not present degradate after 1 week and maintained their weight in the second week (

Figure 5). The mass gain values of MDOX and MControl, exhibited a similar behavior at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 days but showed a statistically significant difference at time 0 h (

p < 0.05). The membranes are formed through hydrogen bonds, ionic interaction, and other non-covalent interactions. These bonds maintain their structural integrity, forming a viscoelastic biomaterial with implantable ability, self-healing properties, and superabsorbency for wound tissue remodeling [

9].

2.4. Blood coagulation

PT test and the APTT evaluated the effect of the membranes on the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of blood coagulation, respectively. The

Table 1 shows the PT and APTT of CMC/CHS/G and CMC/CHS/G-DOX. The unloaded membranes induced a PT and APTT within the normal range. Similarly, the DOX-loaded membranes also induced a PT and APTT within the normal range. These findings showed that the membranes did not have an interaction with the blood coagulation pathways. Although membranes composed of CMC and CHS have demonstrated hemostatic properties, their hemostatic effect depends on both the membrane composition and the percentage of these polymers [

28,

29]. In this study, the samples were prepared with a percentage of CMC and CHS that did not induce any effect on the PT and APPT. In addition, doxycycline is an antibiotic with various biological effects; however, these do not include the induction or inhibition of blood coagulation [

30].

2.5. Hemolytic properties

The design of biomaterials intended for wound care requires careful consideration of their interaction with biological systems. Given that the fabricated membranes are intended to come into direct contact with diabetic foot wounds, ensuring their blood compatibility is a critical requirement to prevent adverse reactions and promote healing. CMC/CHS-based membrane, widely recognized for their hemocompatibility, are generally well tolerated by the human body and do not induce an immune response or inflammation [

31]. The hemolytic properties of the membranes were evaluated by quantifying the extent of hemolysis induced by CMC/CHS membrane (MControl = 16.85%) and the Doxycycline-loading membrane (MDOX = 14.72 %). According to the ASTM standard recommendation that we followed for the experiment; the two membranes showed hemolytic properties (> 5% of hemolysis), but the DOX-loaded membrane induced a hemolytic level lower than the unloaded membrane. The CMC/CHS-based membrane exhibited a hemolytic effect because of the detergent action of the cationic charge in the biopolymeric matrix, which disrupts red blood cells [

32]. Interestingly, the DOX-loaded membranes at 1.08% induced a lower percentage of hemolysis, thus the addition of antibiotic might reduce the cationic charges. Indeed, polymer-based films have improved its blood compatibility properties when DOX was added into the formulation [

33].

2.5. Antibacterial activity of CMC/CHS/G-DOX membranes

The inhibition results for

Staphylococcus aureus,

Escherichia coli and

Streptococcus mutans using CMC/CHS/DOX membranes indicated that the conformation of these membranes does not significantly affect the inhibition capacity against the evaluated strains (

Table 2). In both repetitions, a constant and effective inhibition of

S. aureus,

E. coli and

S. mutans growth was observed. Inhibition was complete for

S. aureus and

S. mutans, and partial for

E. coli, where, in both repetitions, the bacterial count was lower than the initial inoculum. As observed, there is no significant difference in the inhibition capacity of the CMC-CHS-DOX membranes, suggesting that the proposed formulation allows for membrane synthesis without compromising the inhibition capacity of the active ingredient or antibiotic contained in them. It is important to note that carboxymethyl cellulose, glycerol, and chitosan do not exhibit any inhibitory capacity against

S. mutans,

S. aureus, and

E. coli (

Table 2), the membranes without doxycycline allowed adequate growth of all evaluated strains. When conducting inhibition tests using the sensidisc method, an average inhibition halo of 25.5 mm was observed for all evaluated strains. Although the inhibition halo technique [

34], and agar well diffusion [

35] is commonly used to assess the ability of biomaterials to inhibit bacterial strains, counting bacteria in the presence of biomaterials provides more detailed information on their effective inhibition [

36]. Our results indicate that the inhibition halo test did not provide as detailed information as the results presented in

Table 2, where total inhibition of

S. mutans and

S. aureus were observed, similar to previous studies [

17,

37]. Previous research has shown that the inhibitory effect of Doxycycline has a wide range of activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

37,

38]. In contrast, the inhibition halos formed by the MDOX membranes showed only partial inhibition for all the evaluated strains.

Among the characteristics that doxycycline has as an antibiotic there is a systematic action in various tissues. Its high lipophilicity allows it to penetrate numerous membranes to reach target molecules. Tetracyclines act as cationic coordination complexes to cross OmpF and OmpC porins channels in gram negative bacteria. Similarly, in Gram positive bacteria, the neutral, lipophilic form penetrates the cytoplasmic membrane. Passage through the cytoplasmic membrane is energy-dependent and proton-motive force-driven [

4]. The bacteriostatic action of DOX aims to inhibit bacterial growth by allosterically binding to the 30S prokaryotic ribosomal unit during protein synthesis. DOX prevents the binding of charged aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) to the A-site of the ribosome, halting the elongation phase and leading to an unproductive cycle of protein synthesis. Doxycycline affects the binding rate of triple complex formation with the ribosome. The development of microbial resistance to antibiotics poses a potential risk. However, the local application of 1 % doxycycline has a significantly higher concentration (i.e., 10,000 mg/ml) than the minimum inhibitory concentration required for a 50% reduction in pathogenic growth, thereby minimizing the likelihood of developing doxycycline-resistant bacteria (Level IV) [

4,

39]. Considering the characteristics of this antibiotic and its ability to inhibit bacteria associated with diabetic ulcers, we propose CMC/CHS/G/DOX membranes as a release system with effective antibacterial properties. This system represents a promising alternative treatment to promote tissue recovery and restoration in patients affected by diabetic ulcers. Furthermore, when these membranes were tested for water absorption and swelling capacity in BPS, they demonstrated promising results for potential use in skin. An additional advantage is their ability to be applied directly to the infection site, enhancing their therapeutic effectiveness.

3. Material and methods

3.1. Formulation and synthesis of membranes

Carboxymethyl cellulose sodium (CMC, molecular weight of 90 kDa, degree of substitution of 0.7) and high molecular weight (CHS) in powder form, with a deacetylation degree greater than 85% were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Glacial Acetic acid and distilled water were acquired from Sigma Aldrich (USA). Glycerol spectrophotometric grade, 99.5%+, was obtained from Acros, New Jersey, USA. Doxycycline was purchased from RAAM De SAHUAYO Lab. S.A. DE C.V. Reagents for prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) were acquired from Spinreact (México). Hemolysis test was performed with the use of cyanmethemoglobin reagent (Hycel Reactivos Químicos México) and standard hemoglobin was acquired from Spinreact.

3.1.1. Preparation of CMC/CHS membrane

The membranes were prepared by the modified method of casting and evaporation of the solvent reported by Hachity et al. Forty mL of the CHS suspension, prepared as described above were poured into Petri dishes (16 cm in diameter) at an analytical scale. The prepared plates were dried at room temperature for 72 h until the water had completely evaporated. The final sample designation and amounts of CMC, CHS, G and DOX used for each sample were summarized in

Table 3. The MDOX was prepared at the same formulation, with 100 mg of hyclate of doxycycline (DOX) to produce a membrane containing 1.08% of DOX.

3.2. In vitro characterization of the membranes

3.2.1. Visual inspection and evaluation of content uniformity in the membranes

The samples were analyzed with an optical microscope Leyca DM-1000 using a Leyca CC50 camera at 4X and 10X amplifications to identify the presence of some imperfections, both after preparation and during storage. The uniformity of membrane was assessed by cutting discs of 0.6 cm in diameter from five different areas of the studied TP samples.

3.2.2. Scanning electron microscopy analysis

The surface images of TP samples were observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL, JSM-6610 LV, Japan). The membranes were dried at 75 °C for 48 h, and then dried fragments were broken and coated with gold by sputtering to produce electric conductivity. SEM images of the membrane surface were taken in a low vacuum condition operating at 5 kV.

3.2.3. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR-ATR) spectra analysis

The spectra of the sample of CMC/CHS and its DOX sample were obtained used Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) (attenuated total reflectance) accessory (Bruker, Vertex 70 model), with 32 scans in the interval between 400 and 4,000 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

3.2.4. Tensile strength and elongation

The tensile tests were performed according to the method described in the literature [

20,

40] using a universal testing machine (Instron 4465, Instron, Norwood, MA, USA) at 5 mm/min crosshead speed. All samples were cut to the standard shape of 20 mm wide and 150 mm gauge length. The measurement was performed in the ambient condition (25 °C, relative humidity of 48 ± 2%). Tensile strength and elongation at break were evaluated (n = 10), and the average values were reported for accuracy.

3.2.5. Mass and thickness of membranes

The samples were weighed separately using the analytical balance (OHAUS Adventure Pro AV265C: 260g (SD ± 0.1mg) (l ± 0.3mg), after 48h stored at room temperature. The mean mass and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. The thickness of the membrane was measured using a micrometer screw (SHAHE-Model T152002FR, 0–25 ± 0.04 mm) in the center and each corner, taking an average of the ten values per unit (n = 10).

3.2.6. Roughness

The membrane surface roughness parameters were measured with a previous roughness meter (Mitutoyo SJ-301, Mitutoyo American Corporation, EU), working at a speed of 0.25 mm/s and a cutoff distance of 0.8 × 5 mm [

41]. The membranes were fixed with double-sided tape parallel to the tip of the roughness gauge. Five samples were used (n = 10).

3.2.7. Surface pH

A disc unit (n = 10) was placed in a flask containing 5 mL of deionized water. The formulation was allowed to swell for 5 min and was subsequently removed from the flask[

42]. The resulting pH of the liquid was recorded using a pH meter (ROCA-Model PHS-3CU) at 25 °C and was taken as an indication of the formulations surface pH.

3.2.8. Moisture sorption

The membrane’s moisture sorption was studied by exposing them to 75% relative humidity (RH) using a desiccator with an oversaturated NaCl solution at room temperature. The units were pre-weighed (m1) and stored in a humid desiccator for 10 days (n = 10). Afterwards, they were re-weighed (m2). Moisture sorption was calculated in the same manner as Swelling capacity and multiplied by 100 to obtain the sorption percentage[

42]. The experiment was performed with ten samples.

3.2.9. Water absorbance capacity

CMC/CHS membranes and DOX loading membranes were cut into small discs (0.6 cm diameter, n = 10), desiccated overnight under vacuum, and weighed to determine their dry mass. The weighed discs were placed in a flask containing 5 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 25 °C [

11]. The swelling kinetics were evaluated by periodically measuring the weight increment of the samples with respect to dry membranes using an analytical scale with a precision of 0.001 g. After gently bottling the surface with a tissue to remove the excess PBS solution, the samples were weighed, and the respective values were recorded until 7-day.

The water vapor gain (W.G.) was calculated as follows:

Eq. 1

where m1 expressed the weight of swollen membranes, while m2 expressed the weight of dried membranes.

3.2.9. Swelling capacity

The swelling capacity of membranes was evaluated using a modified test from literature [

42], where a membrane with a determined mass (m1) was placed in a glass flask and immersed in 5 mL of artificial saliva solution (pH = 7.38) at 37 °C, to mimic the temperature conditions in the oral cavity. The membrane was allowed to swell for 5min. Its mass (m2) was recorded after gently wiping the product with a piece of tissue paper to remove the surface water. The swelling index represents the mass gained with respect to the mass of a dehydrated membrane and was calculated according to Equation 2. The experiment was carried out in ten times.

Eq. 2

3.2.10. Disintegration or Biodegradability

The disintegration test was performed using a modified disc method from literature [

42]. A membrane disc was immersed into a flask containing 5 mL of simulated body fluids (SBFs) (buffer solution) at pH = 7.40 and at 37 °C to determine their biodegradability in skin humans. During the experiment, the disintegration time for separate units of membrane discs was observed. In cases where a coherent matrix remained after 168 h, the sample was recorded as not disintegrated. Ten parallels were tested for each formulation (n = 10).

Blood coagulation time: prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time

The prothrombin time PT was measured to evaluate the effect of the samples on the extrinsic pathway and the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) was measured to evaluate the effect of the membrane samples (MControl and MDOX) on the intrinsic pathway [

43]. Citrated blood was collected from a healthy adult human donor and the blood was used in the experiments. Then, 60 mg of each membrane was incubated with 600 µL of whole blood in a 2 mL conical-bottom tube. The samples were incubated at 37 °C with oscillatory stirring at 100 rpm for 15 minutes (MaxQ 4450 Thermo Scientific). Immediately after the incubation, the blood from each tube with the membrane sample was collected with a micropipette and then the blood was poured into a 1.5 mL conical-bottom tube; these new samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3000 rpm to separate the plasma from the blood cells. The plasma was used to measure the PT and the APTT with the Biobas 10 coagulometer (Spinreact México). Plasma from blood without contact with any sample was used as a physiological control. A normal control and a pathological 4.2.11 control (Spinreact México) were used as negative and positive control, respectively. The blood for these controls was also incubated at 37 °C, at oscillatory stirring (100 rpm, 15 minutes). The normal PT time was set at 11.1-14.3 seconds according to the reagent instructions. The normal APTT time was set at 24-36 seconds according to the reagent instructions. All experiments were done by triplicate.

3.2.12. Hemolysis test

We performed a hemolysis test based on the Standard Practice for Assessment of Hemolytic Properties of Materials (ASTM designation: F 756–00) [

44]. Briefly, blood from a healthy adult donor was used to assess the hemolytic properties of the experimental membranes. The blood was collected with EDTA vacutainer tubes. Each experimental membrane (60 mg) was incubated with blood (600 µL) in the same way as described for the blood coagulation experiments. Also, blood was collected to separate the plasma from the blood cells in the same way as described for the blood coagulation experiments. The plasma (25 µL) obtained from the blood in contact with the experimental membrane was mixed with cyanmethemoglobin reagent (225 µL) in a well of a 96 well microplate. Then, the hemoglobin in plasma was measured at 540 nm in a microplate reader (Multiskan FC Thermo Scientific). The hemoglobin concentration was obtained from a calibration curve made with a solution of standard hemoglobin mixed with cyanmethemoglobin reagent. Hemolysis was expressed as the percentage of hemoglobin released to total content. Thus, we mixed a sample of blood with cyanmethemoglobin reagent to get the 100% of hemolysis. In addition, we used a NaCl solution as a positive control and a silicon sample as a negative control. A physiologic control was performed with plasma collected from blood from the donor. According to the ASTM standard [

44], the material might be nonhemolytic (0%–2% of hemolysis), or slightly hemolytic (2%–5% of hemolysis), or hemolytic (> 5% hemolysis). All experiments were done by triplicate.

3.3. Antibacterial activity of CMC/CHS/G/DOX membranes

The antibacterial capacity of the formulated membranes was evaluated using S. aureus and E.coli strains, which are commonly associated with the development of foot ulcers in diabetic patients. Additionally, the antimicrobial capacity of the membranes against S. mutans was evaluated to explore an alternative use of the membranes in oral cavity diseases, such as caries.

3.3.1. Bacterial growth

S. mutans was cultured overnight in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium, which contains calf brain and bovine heart infusions, peptone, NaCl, glucose, and disodium phosphate. The bacteria were incubated for 24 hours at 37° C under anaerobic conditions with 5% CO₂, using an ESCO CelCulture CO₂ incubator, without shaking. After 24 hours, the optical density (OD) of the culture was measured at 600 nm using a 100 µL sample. The measured OD value was used to prepare a subculture, adjusting it to an initial OD of 0.05. This step ensured a standardized bacterial concentration for subsequent inhibition tests. S. aureus and E. coli strains were cultured aerobically in LB liquid medium at 37° C with constant shaking (180 rpm). The subculture methodology previously described was applied. Colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) at an optical density of 0.05 were determined using the Massive Stamping Drop Plate method (MSDP) [

45].

To conduct the inhibition tests, CMC/CHS/G/DOX membranes (round, ~5 mm in diameter) were sterilized under UV light for 20 minutes per side in a class II biosafety cabinet (LABCONCO Purifier® Biological Safety Cabinet). Once sterilized, two membranes were added to the subcultures of each evaluated strain, as well as to BHI or LB liquid medium as controls. The samples were incubated for 24 hours under aerobic or anaerobic conditions as previously described. After incubation, the CFU/mL count was determined using the MSDP method on BHI or LB solid medium. For the control samples, 25 µL drops were placed on BHI or LB solid medium and incubated for 24 hours under aerobic or anaerobic conditions, depending on the bacterial strain. Additionally, as a secondary control, each membrane was placed directly on BHI or LB solid medium and incubated under the same conditions. This procedure was performed in duplicate, with CFU/mL counts determined in quintuplicate for each repetition. Additionally, the inhibition test was conducted using a technique similar to the sensidisc method, following the methodology described by Hachity-Ortega et al. [

10].

3.4. Statistical analysis

All values are presented as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). Statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi 2024 [

46,

47] to evaluate the data obtained. To compare the water absorbance capacity, swelling index, roughness, moisture sorption, surface pH, tensile strength, elongation, mass and thickness measurements, and antibacterial activity between the two TP, an independent sample t-test was employed. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Conclusions

An efficient synthesis of CMC/CHS membranes loaded with doxycycline (DOX) is presented. The incorporation of DOX into the membranes demonstrated effective antibacterial activity against S. aureus and S. mutans. Mechanical and physical characterization, along with low hemolytic levels, suggest that DOX-loaded CMC/CHS/G membranes hold potential as a wound delivery system for topical applications. Further kinetic studies and in vivo evaluations are required to explore their effectiveness in treating diabetic foot wounds.

Author Contributions

S.P-G and J.A.R.-E. Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Resources. A.V.J-D: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Software, Visualization. LAP-R: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. A.F-L: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. E.R-C: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. D.C.P.-G and P.G.G.-G: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. I.J-D: Investigation, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing B.I.C.-C. Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources, Validation, Visualization. J.L.S.-F: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision. C.S.V. Formal analysis, Resources B.E.C-S. Funding acquisition, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.G.N.R.de C-Q. Resources, supervision. A.G.M-G. Validation, Funding acquisition

Funding

This research was funded by Faculty of Stomatology, Meritorious Autonomous University of Puebla (BUAP)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bioengineering Department of the Tecnológico de Monterrey, Puebla campus, for the facilities provided to carry out part of the experiments presented, which were essential for obtaining relevant results that strengthen this publication. We also extended our gratitude to Bioengineering undergraduate students Chacón-Ortega A., González-Tecpa B., Romero-Cerón A.L., Castillo-Quijano E., Salazar-Hernández M. A., and Avendaño-Mercado M. F. from Tecnológico de Monterrey and Gonzalez-Martínez Mayra from BUAP for their valuable support during the experimental process. CS-V, MC-S, BC-S, and BICC are members of the National Researchers System of SECIHTI and thanks this Institution for the support provided. AJ-D, CS-V, BC-S are members of the Academic Group “Biomedicina y Nuevas Tecnologías Aplicadas a la Odontología”, BUAP-CA-383, PRODEP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akkus, G.; Sert, M. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Devastating Complication of Diabetes Mellitus Continues Non-Stop in Spite of New Medical Treatment Modalities. World J Diabetes 2022, 13, 1106–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulton, A.J.M. The Pathway to Foot Ulceration in Diabetes. Medical Clinics of North America 2013, 97, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, S.; Leton, N.; Nayak, N.; Jha, A.; Anand, N.; Thompson, K.; Boothe, D.; Cromer, A.; Garcia, Y.; Al-Islam, A.; et al. A Systematic Review of Diabetic Foot Infections: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management Strategies. Frontiers in Clinical Diabetes and Healthcare 2024, 5, 1393309–1393309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliy, O.; Popova, M.; Tarasenko, H.; Getalo, O. Development Strategy of Novel Drug Formulations for the Delivery of Doxycycline in the Treatment of Wounds of Various Etiologies. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 195, 106636–106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samari, M.; Kashanian, S.; Zinadini, S.; Derakhshankhah, H. Designing of a New Transdermal Antibiotic Delivery Polymeric Membrane Modified by Functionalized SBA-15 Mesoporous Filler. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 10418–10418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldaghi, N.; Kamalabadi-Farahani, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Salehi, M. Doxycycline-Loaded Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Sodium Alginate/Gelatin Hydrogel: An Approach for Enhancing Pressure Ulcer Healing in a Rat Model. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2024, 112, 2289–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosch, A.; Haefner, S.; Jude, E.; Lobmann, R. Diabetic Foot Infections: Microbiological Aspects, Current and Future Antibiotic Therapy Focusing on Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. International Wound Journal 2011, 8, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Xue, H.; Zhang, Z.; Panayi, A.C.; Knoedler, S.; Zhou, W.; Mi, B.; Liu, G. Recent Advances in Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Based Materials for Biomedical Applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, M.; Reshma, G.; Arthi, C.; Másson, M.; Rangasamy, J. Biodegradable Polymeric Scaffolds and Hydrogels in the Treatment of Chronic and Infectious Wound Healing. European Polymer Journal 2023, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachity-Ortega, J.A.; Jerezano-Domínguez, A.V.; Pazos-Rojas, L.A.; Flores-Ledesma, A.; Pazos-Guarneros, D. del C.; Parra-Solar, K.A.; Reyes-Cervantes, E.; Juárez-Díaz, I.; Medina, M.E.; González-Martínez, M.; et al. Effect of Glycerol on Properties of Chitosan/Chlorhexidine Membranes and Antibacterial Activity against Streptococcus mutans. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulu, A.; Aygün, T.; Birhanlı, E.; Ateş, B. Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of Multi–Biofunctional Properties of a Novel Chitosan–Carboxymethylcellulose–Pluronic P123 Hydrogel Membranes Loaded with Tetracycline Hydrochloride. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 222, 2670–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinte, E.; Muntean, D.M.; Andrei, V.; Boșca, B.A.; Dudescu, C.M.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Borodi, G.; Andrei, S.; Gal, A.F.; Rus, V.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Characterisation of a Mucoadhesive Buccal Film Loaded with Doxycycline Hyclate for Topical Application in Periodontitis. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.; Wang, Z.; Muhammad, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, K.; Ji, J.; Zhu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, H. Fabrication of Carboxymethyl Cellulose and Chitosan Modified Magnetic Alkaline Ca-Bentonite for the Adsorption of Hazardous Doxycycline. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tort, S.; Acartürk, F.; Beşikci, A. Evaluation of Three-Layered Doxycycline-Collagen Loaded Nanofiber Wound Dressing. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2017, 529, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, D.N.; Ehtisham-ul-Haque, S.; Ahmad, S.; Arif, K.; Hussain, E.A.; Iqbal, M.; Alshawwa, S.Z.; Abbas, M.; Amjed, N.; Nazir, A. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan, Guar Gum and Polyvinyl Alcohol Blend Matrix Loaded with Amoxicillin and Doxycycline Hyclate Drugs. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Bilal Khan Niazi, M.; Hussain, A.; Farrukh, S.; Ahmad, T. Development of Anti-Bacterial PVA/Starch Based Hydrogel Membrane for Wound Dressing. J Polym Environ 2018, 26, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Y.; İnce, İ.; Gümüştaş, B.; Vardar, Ö.; Yakar, N.; Munjaković, H.; Özdemir, G.; Emingil, G. Development of Doxycycline and Atorvastatin-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for Local Delivery in Periodontal Disease. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, E.A.; Lynch, K.A.; Boyce, S.T. Development of the Mechanical Properties of Engineered Skin Substitutes After Grafting to Full-Thickness Wounds. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 2014, 136, 0510081–0510081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Filppula, A.M.; Zhao, Y.; Shang, L.; Zhang, H. Mechanically Regulated Microcarriers with Stem Cell Loading for Skin Photoaging Therapy. Bioactive Materials 2025, 46, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, P.; Chandika, P.; Khan, F.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, S.-C.; Kim, Y.-M.; Jung, W.-K. PVA/Gelatin Nanofibrous Scaffold with High Anti-Bacterial Activity for Skin Wound Healing Applications. Materials Today Communications 2024, 40, 109356–109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, R.C.; Ishikawa, E.S.A.; Silva, M.F.A. da; Silva-Júnior, A.A. da; Oliveira-Nascimento, L. Five Decades of Doxycycline: Does Nanotechnology Improve Its Properties? International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2022, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinku; Prajapati, A. K.; Choudhary, S. Physicochemical Insights into the Micellar Delivery of Doxycycline and Minocycline to the Carrier Protein in Aqueous Environment. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Singh, B. Synthesis of Hydrogels Based on Sterculia Gum-Co-Poly(Vinyl Pyrrolidone)-Co-Poly(Vinyl Sulfonic Acid) for Wound Dressing and Drug-Delivery Applications. RSC Sustainability 2024, 2, 2693–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana-Ricci, R.; Martinez-de-Jesús, F.; Aragón-Carreño, M.P.; Saurral, R.; Tamayo-Acosta, C.A.; García-Puerta, M.; Vicente-Bernal, P.; Silva-Quiñonez, K.; Felipe-Feijo, D.; Reyes, C.; et al. Vista de Recomendaciones de Manejo Del Paciente Con Pie Diabético. Curso de Instrucción. Revista Colombiana de Ortopedia y Traumatología.

- Peng, T.; Zhu, C.; Huang, Y.; Quan, G.; Huang, L.; Wu, L.; Pan, X.; Li, G.; Wu, C. Improvement of the Stability of Doxycycline Hydrochloride Pellet-Containing Tablets through a Novel Granulation Technique and Proper Excipients. Powder Technology 2015, 270, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulrez, S.K.H.; Al-Assaf, S.; Phillips, G.O.

- Yahia, Lh. History and Applications of Hydrogels. Journal of Biomedical Sciencies 2015, 04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Li, Y.; Tong, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, Q. Strongly-Adhesive Easily-Detachable Carboxymethyl Cellulose Aerogel for Noncompressible Hemorrhage Control. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 301, 120324–120324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, S.; Rezaei kolarijani, N.; Naeiji, M.; Vaez, A.; Maghsoodifar, H.; Sadeghi douki, S.A. hossein; Salehi, M. Development of Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Gelatin Hydrogel Loaded with Omega-3 for Skin Regeneration. https://doi.org/10.1177/08853282241265769 2024, 39, 377-395. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Khanna, D.; Kalra, S. Minocycline and Doxycycline: More Than Antibiotics. Current Molecular Pharmacology 2021, 14, 1046–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, D.; Li, H. Preparation of Fully Bio-Based Multilayers Composed of Heparin-like Carboxymethylcellulose Sodium and Chitosan to Functionalize Poly (L-Lactic Acid) Film for Cardiovascular Implant Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 231, 123285–123285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda-Cristerna, B.I.; Flores, H.; Pozos-Guillén, A.; Pérez, E.; Sevrin, C.; Grandfils, C. Hemocompatibility Assessment of Poly(2-Dimethylamino Ethylmethacrylate) (PDMAEMA)-Based Polymers. Journal of Controlled Release 2011, 153, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonkong, W.; Petsom, A.; Thongchul, N. Rapidly Stopping Hemorrhage by Enhancing Blood Clotting at an Opened Wound Using Chitosan/Polylactic Acid/ Polycaprolactone Wound Dressing Device. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Tebar, N.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J.; Viuda-Martos, M. Chitosan Edible Films and Coatings with Added Bioactive Compounds: Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties and Their Application to Food Products: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ramachandran, G.; Mothana, R.A.; Noman, O.M.; Alobaid, W.A.; Rajivgandhi, G.; Manoharan, N. Anti-Bacterial Activity of Chitosan Loaded Plant Essential Oil against Multi Drug Resistant K. Pneumoniae. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2020, 27, 3449–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhuang, S. Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan and Its Derivatives and Their Interaction Mechanism with Bacteria: Current State and Perspectives. European Polymer Journal 2020, 138, 109984–109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, F.; Raoufi, Z.; Abdollahi, S.; Asl, H.Z. Antibiotic Delivery in the Presence of Green AgNPs Using Multifunctional Bilayer Carrageenan Nanofiber/Sodium Alginate Nanohydrogel for Rapid Control of Wound Infections. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 277, 134109–134109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, J.P.; Chejara, D.R.; Ranch, K.; Joshi, P. Development of Injectable in Situ Gelling Systems of Doxycycline Hyclate for Controlled Drug Delivery System. Applications of Nanocomposite Materials in Drug Delivery 2018, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluit, A.C.; Van Gorkum, S.; Vlooswijk, J. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of Omadacycline and Doxycycline against Bacterial Isolates with Known Tetracycline Resistance Determinants. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmono; Abdurrahim, I. Water Sorption, Antimicrobial Activity, and Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Chitosan/Clay/Glycerol Nanocomposite Films. Heliyon 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ładniak, A.; Jurak, M.; Wiącek, A.E. Physicochemical Characteristics of Chitosan-TiO2 Biomaterial. 2. Wettability and Biocompatibility. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korelc, K.; Larsen, B.S.; Gašperlin, M.; Tho, I. Water-Soluble Chitosan Eases Development of Mucoadhesive Buccal Films and Wafers for Children. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Arriaga, J.C.; Chavarría-Bolaños, D.; Pozos-Guillén, A. de J.; Escobar-Barrios, V.A.; Cerda-Cristerna, B.I. Synthesis of a PVA Drug Delivery System for Controlled Release of a Tramadol-Dexketoprofen Combination. Journal of materials science. Materials in medicine 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Designation: F 756-00 Standard Practice for Assessment of Hemolytic Properties of Materials 1.

- Corral-Lugo, A.; Morales-García, Y.E.; Pazos-Rojas, L.A.; Ramirez-Valverde, A.; Martínez-Contreras, R.D.; Muñoz-Rojas, J. Quantification of Cultivable Bacteria by the “Massive Stamping Drop Plate” Method. Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol 2012, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Jamovi - Open Statistical Software for the Desktop and Cloud.

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).