Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

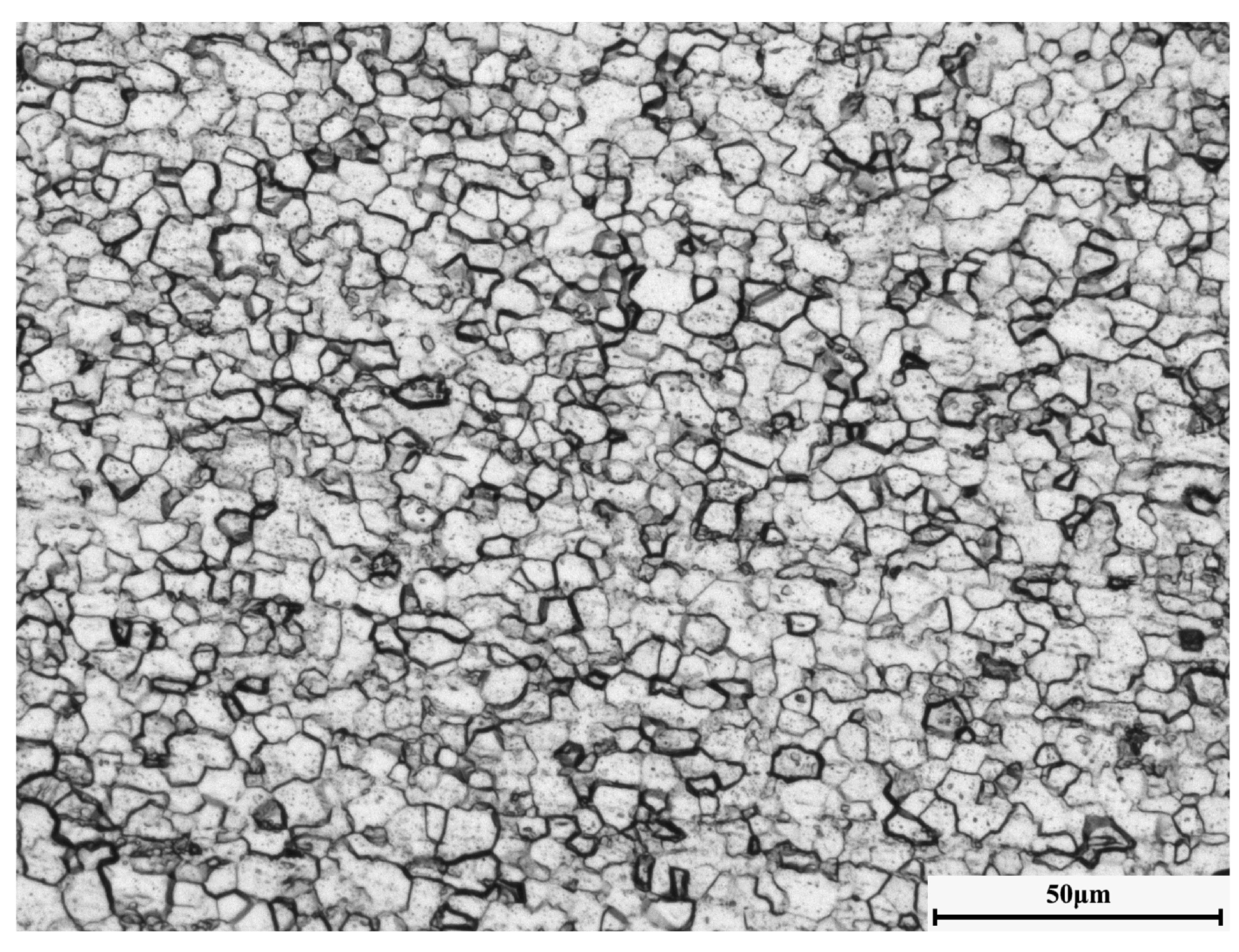

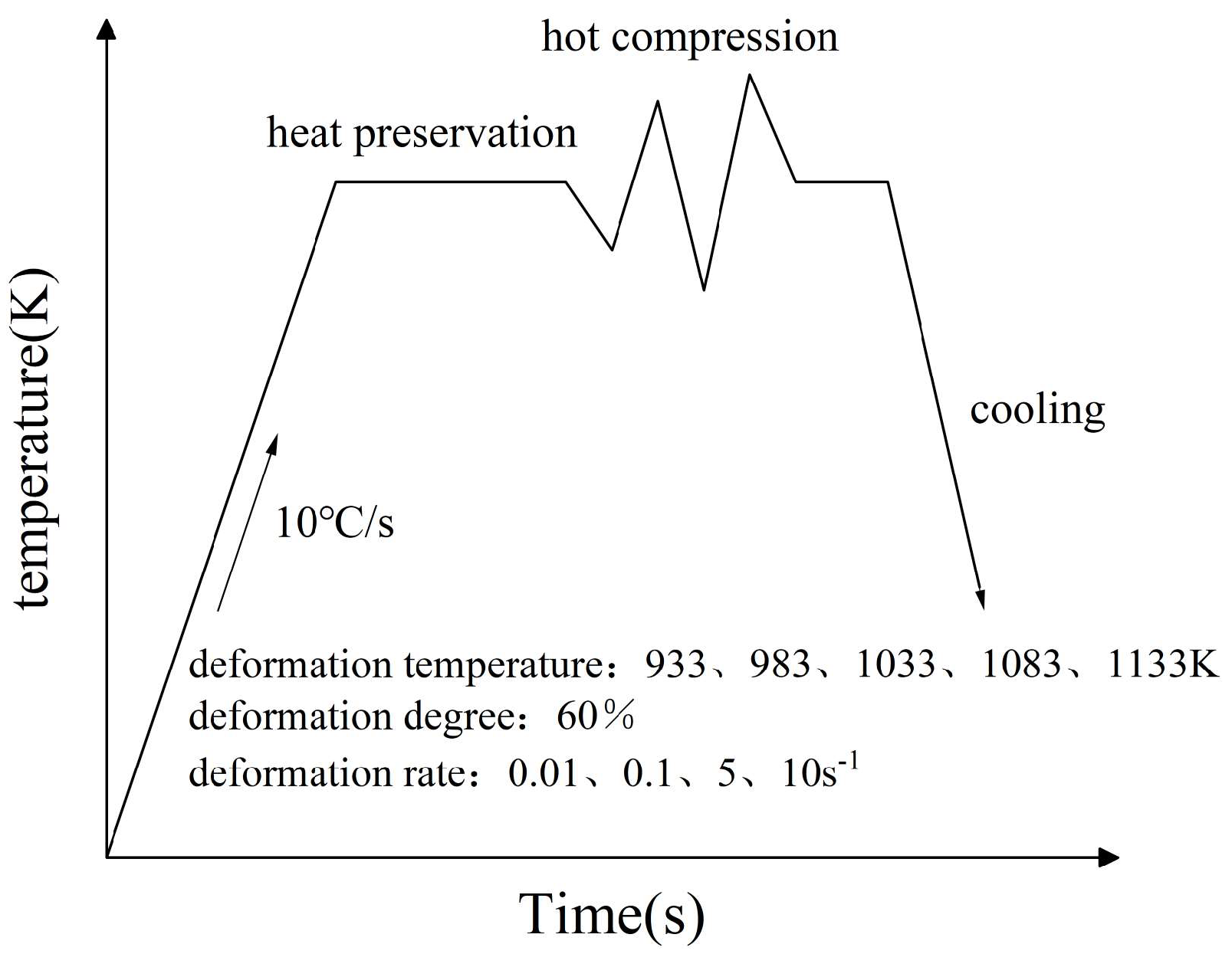

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

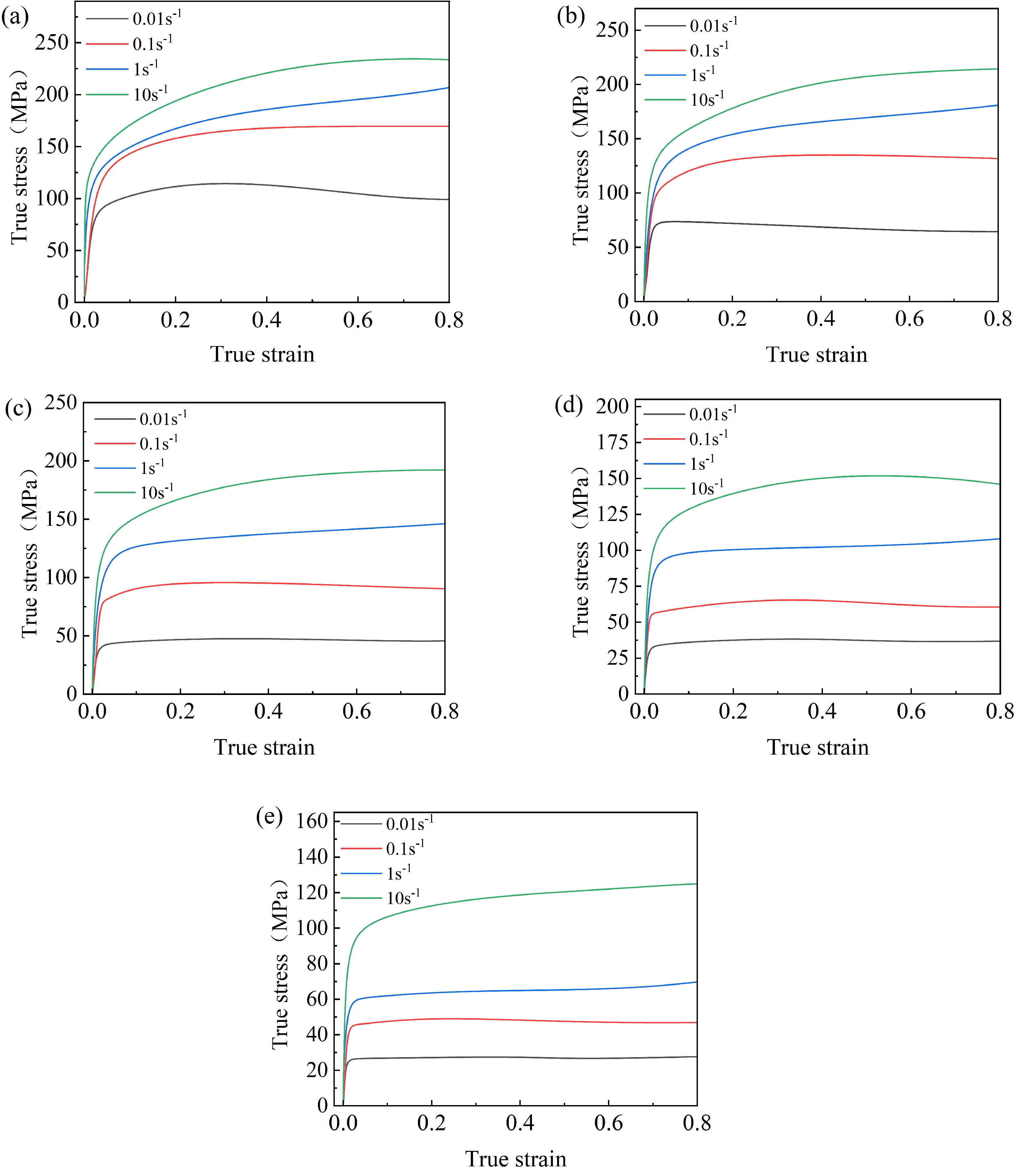

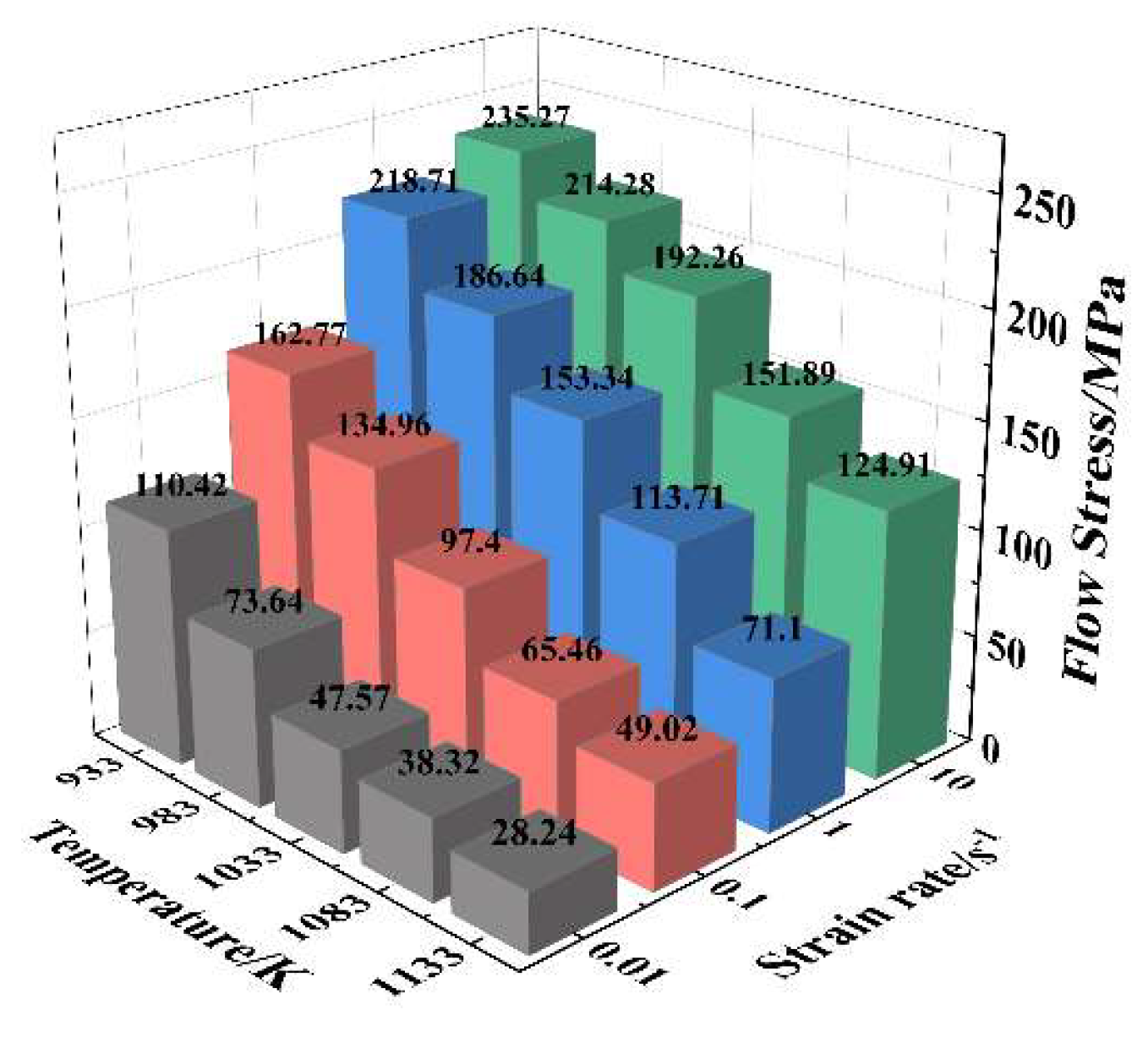

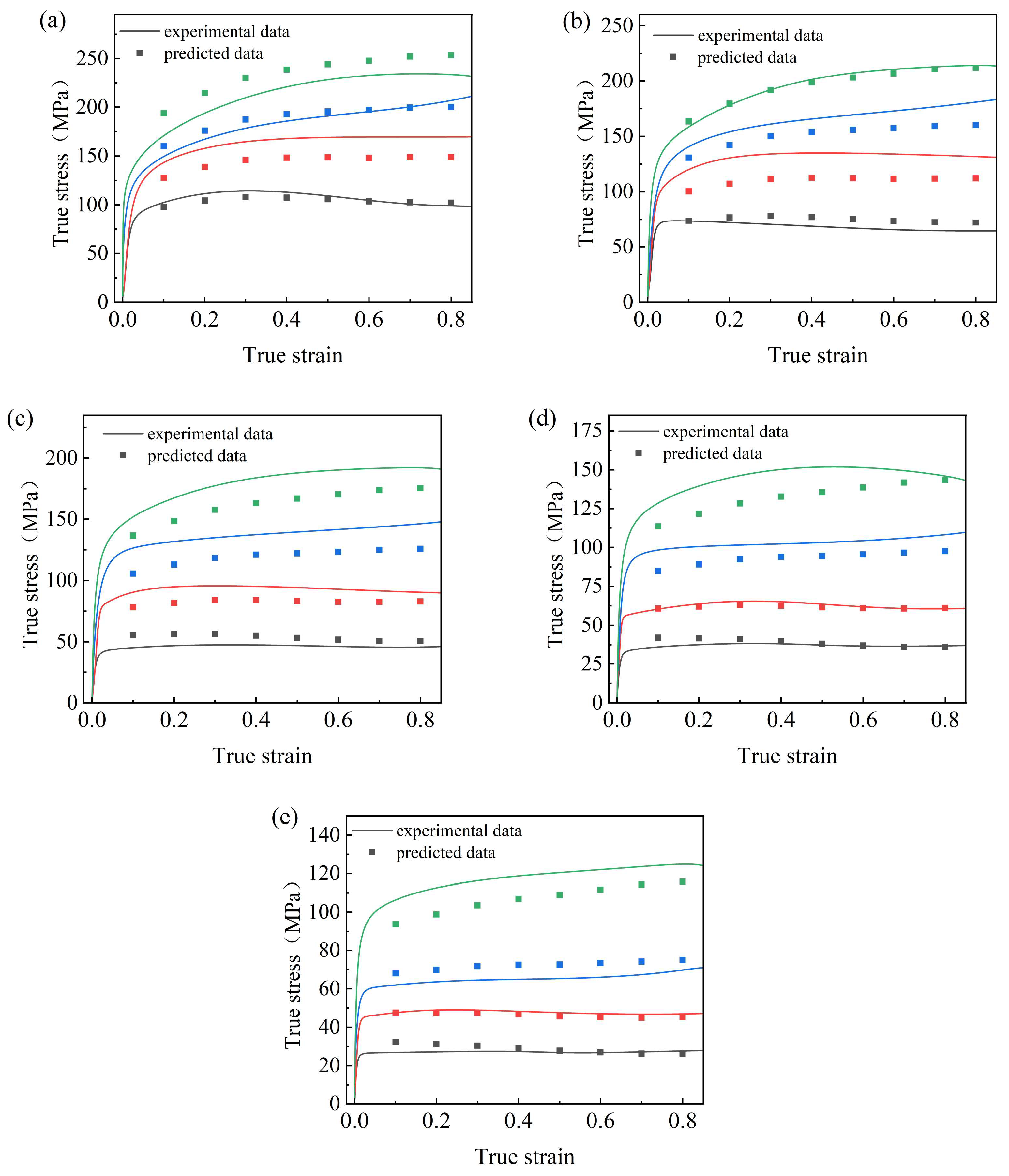

3.1. Flow Stress Behavior

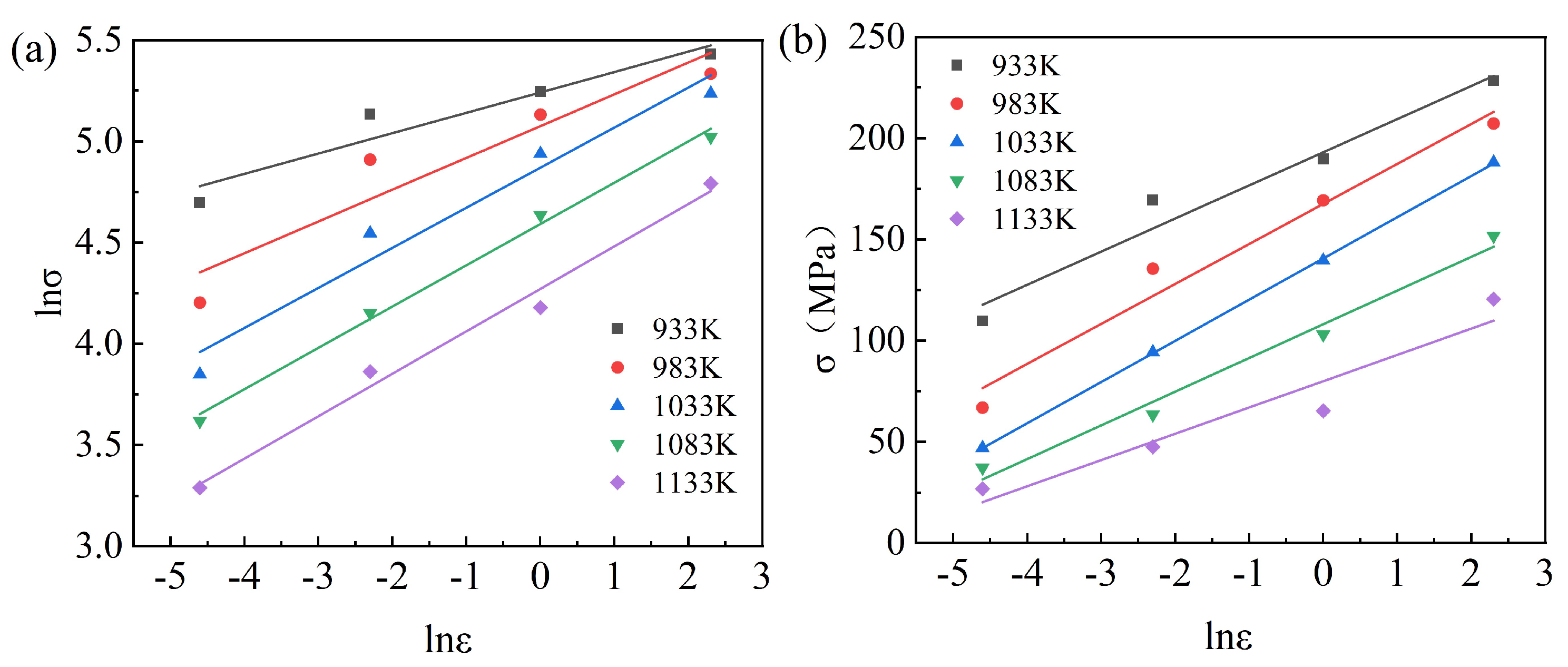

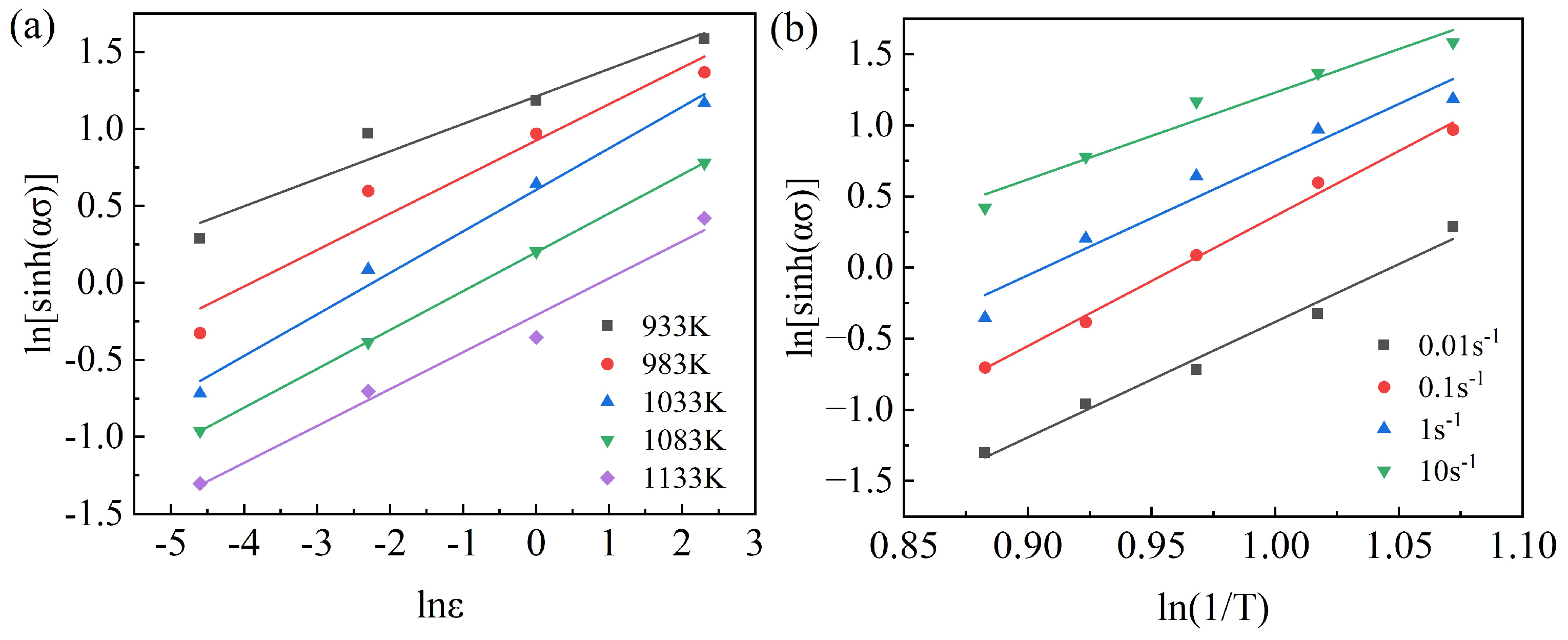

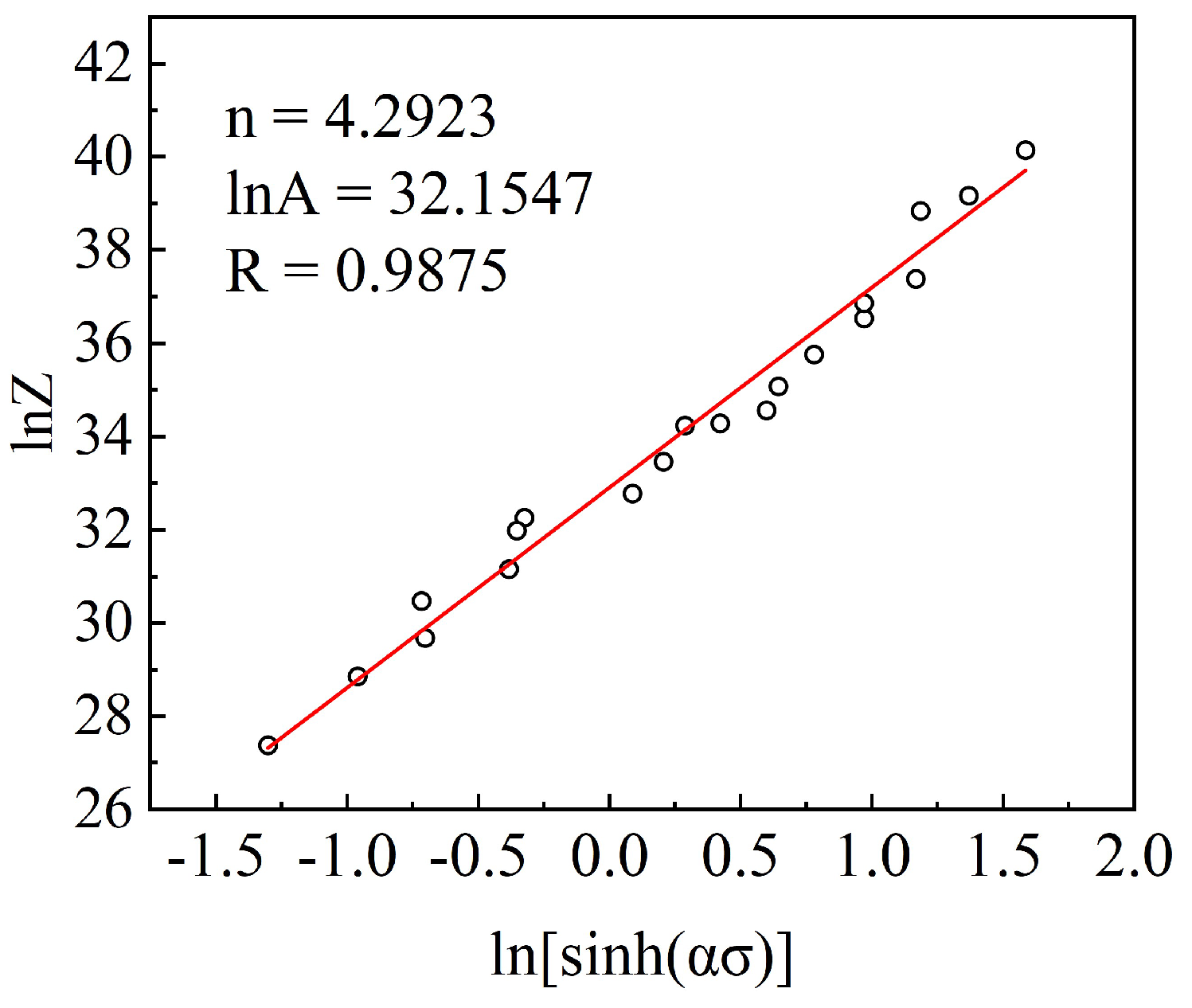

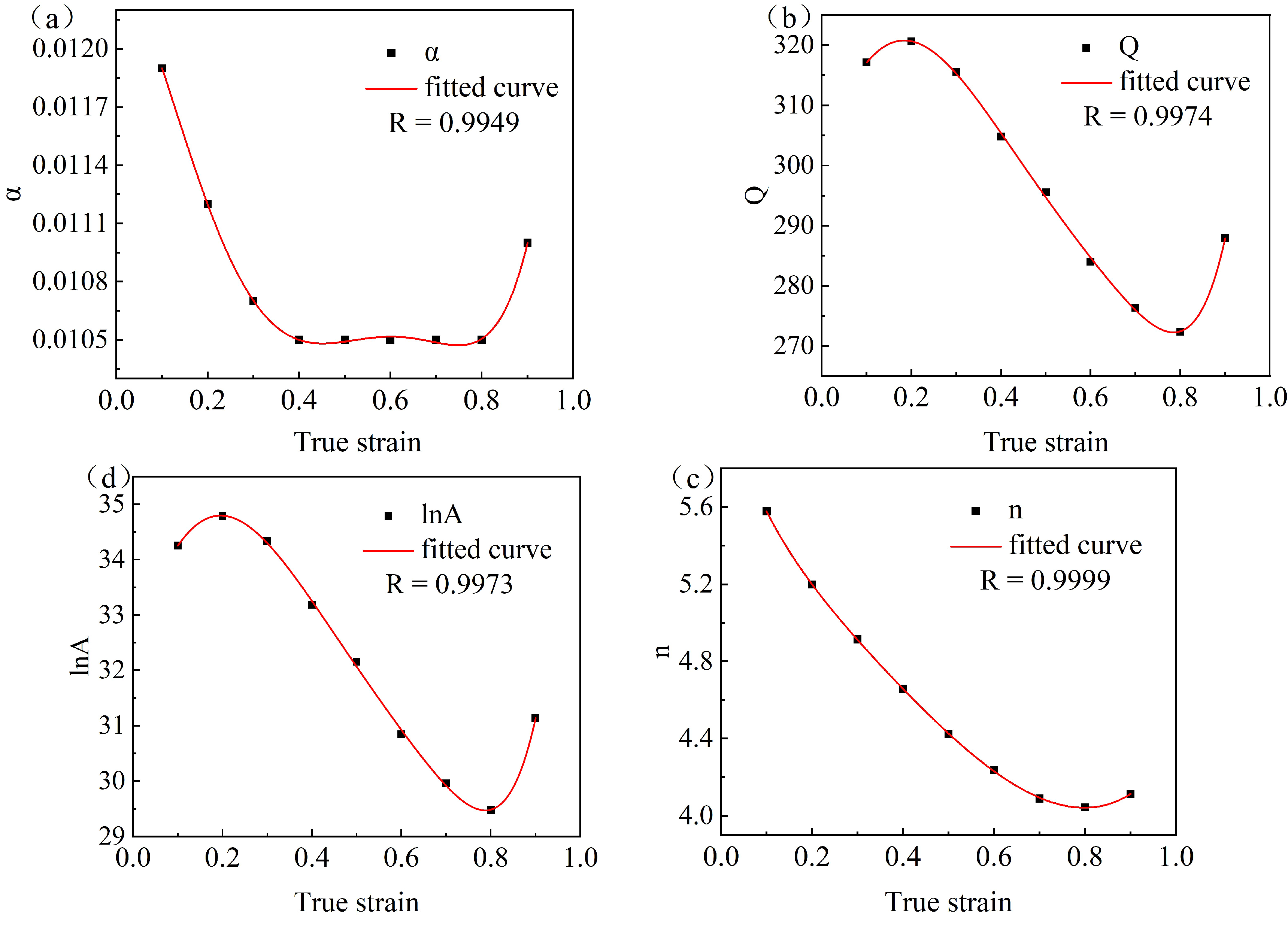

3.2. Derivation of the Constitutive Equation

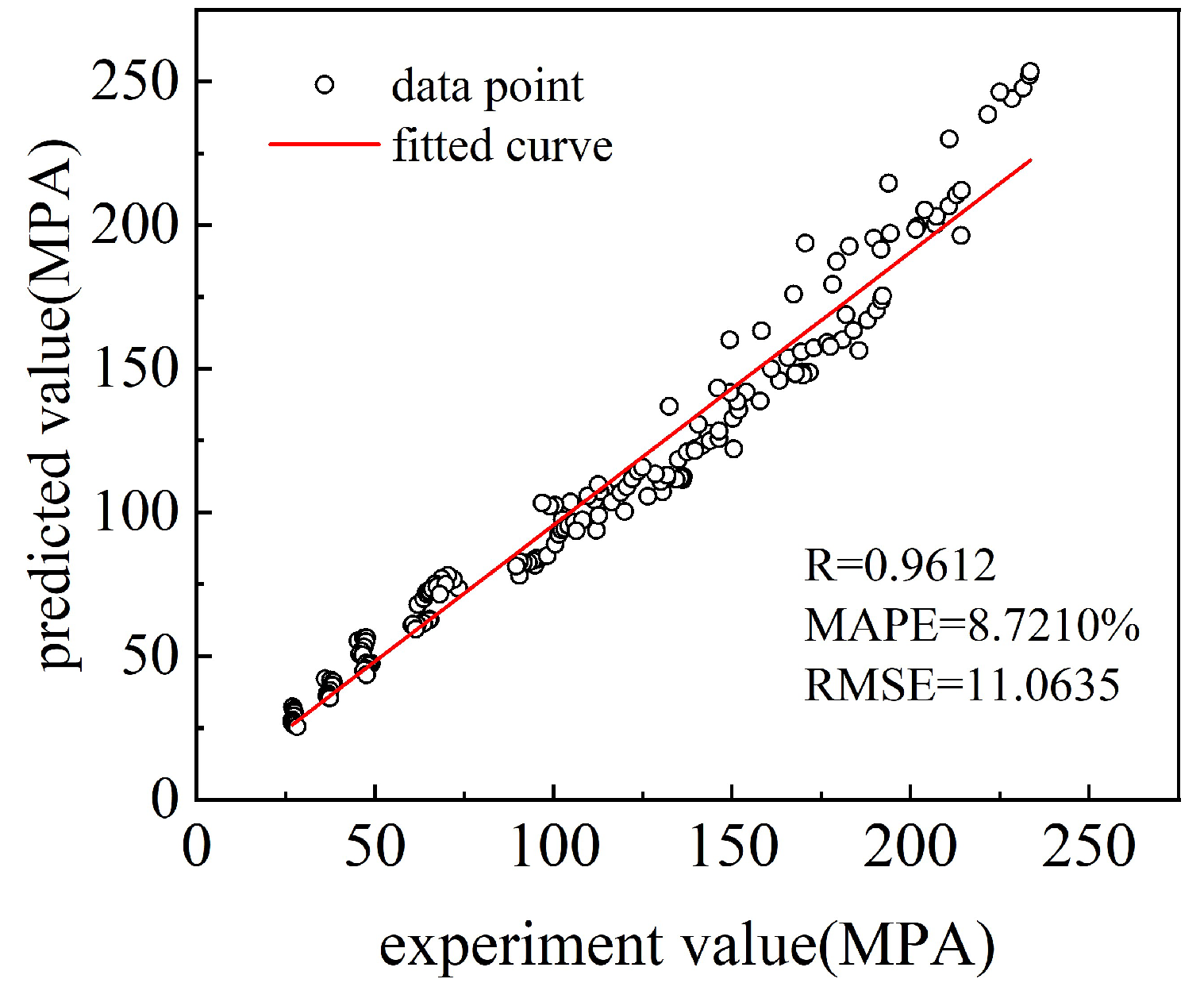

3.3. Evaluation of the Ontological Model

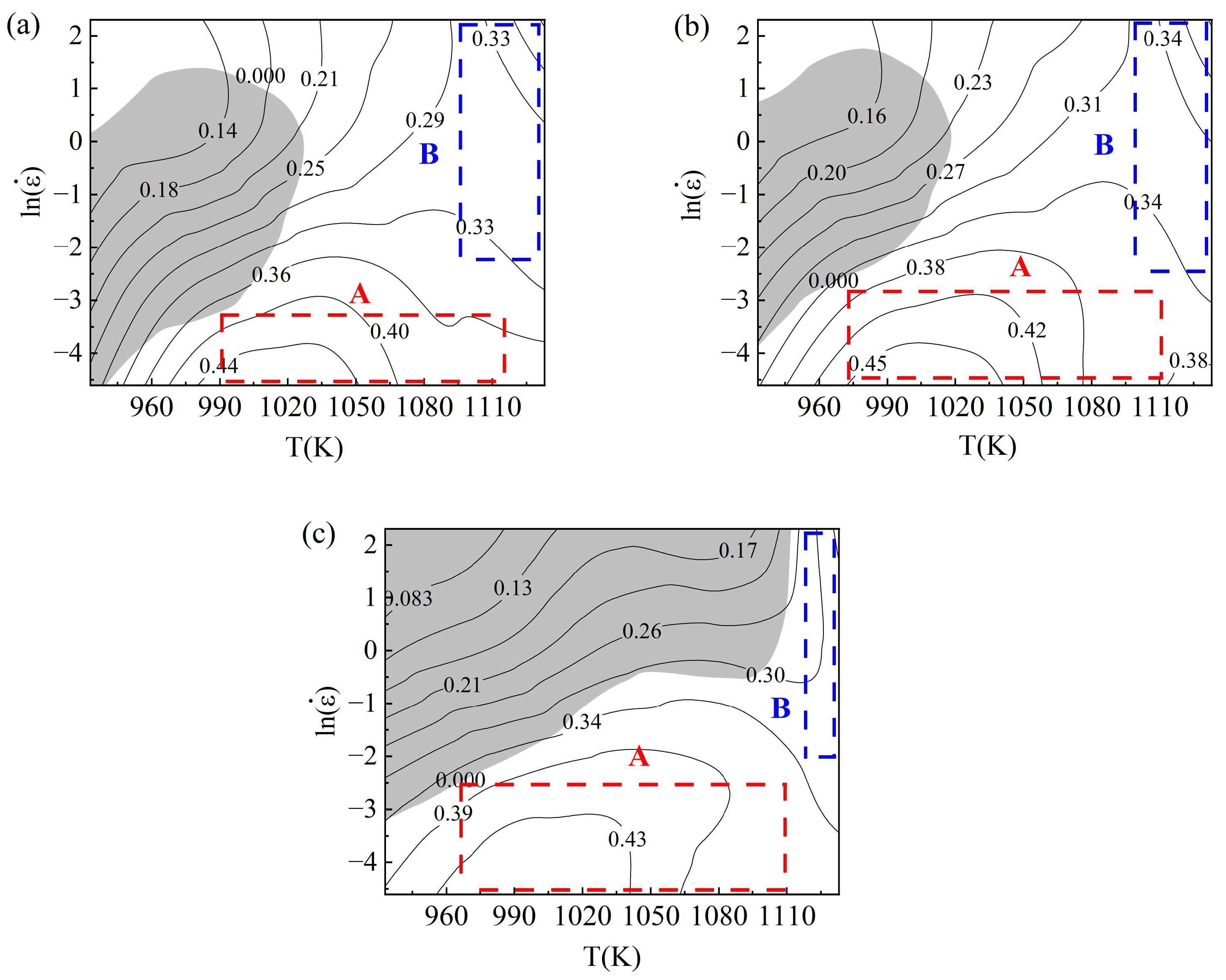

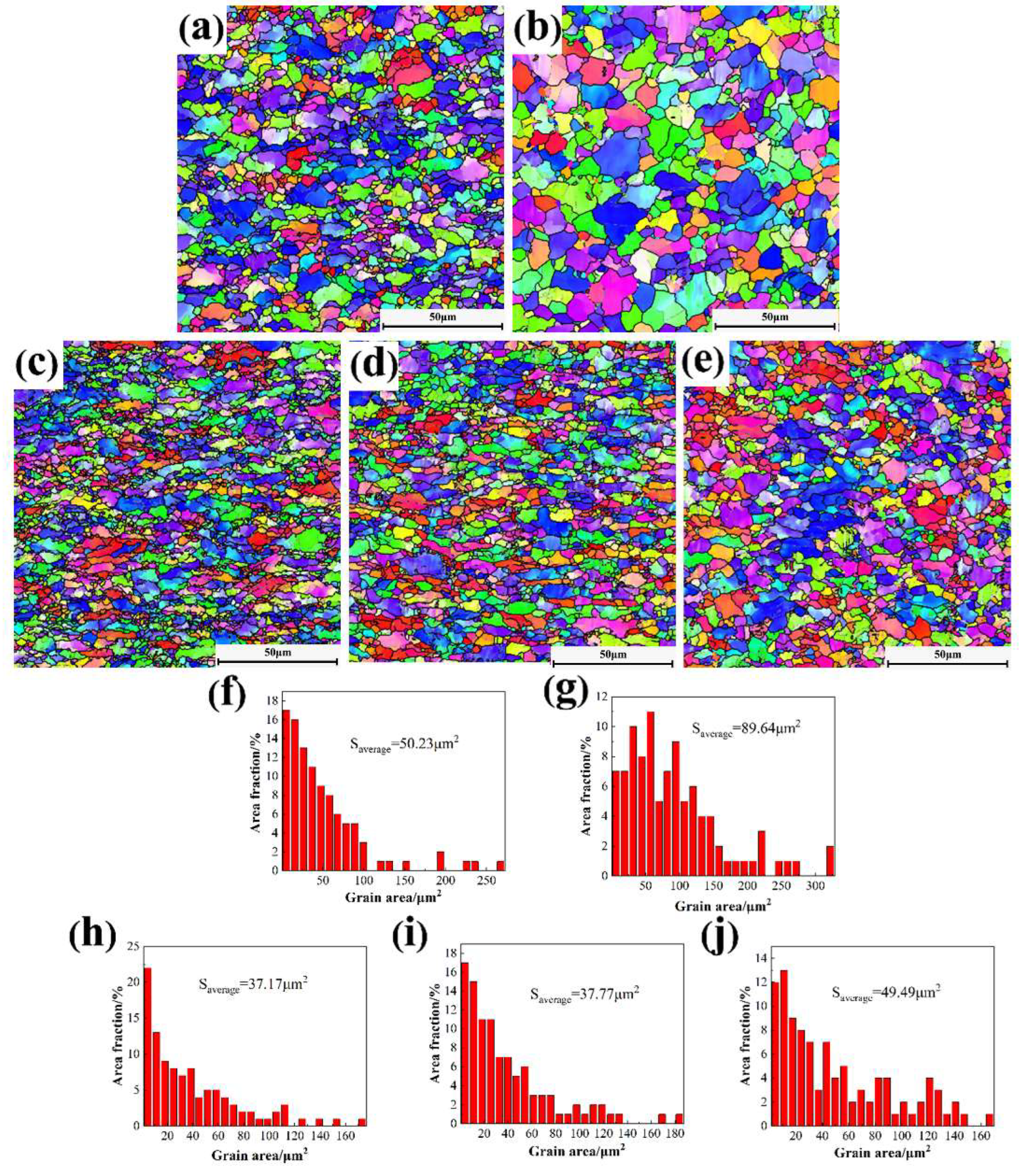

3.4. Creation and Analysis of Thermal Processing Diagrams

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.B.; Hu, H.X.; Zheng, Y.G.; Ke, W.; Qiao, Y.X. Comparison of the corrosion behavior of pure titanium and its alloys in fluoride-containing sulfuric acid. Corrosion Science 2016, 103, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmir, H.; Pereira, P.H.R.; Huang, Y.; Langdon, T.G. Mechanical properties and microstructural evolution of nanocrystalline titanium at elevated temperatures. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2016, 669, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Hong, Z.-q.; Wang, Y.-q.; Zhu, Y.-c. Machine learning-based beta transus temperature prediction for titanium alloys. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 23, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.G.; Yang, H.; Gao, P.F. Prediction of constitutive behavior and microstructure evolution in hot deformation of TA15 titanium alloy. Materials & Design 2013, 51, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, A.; Abbasi, S.M. Effect of hot working on flow behavior of Ti–6Al–4V alloy in single phase and two phase regions. Materials & Design 2010, 31, 3599–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, D.; Cao, S.; Wu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Xin, S.; Qu, L.; Huang, A. Effect of strain rate and temperature on the deformation behavior in a Ti-23.1Nb-2.0Zr-1.0O titanium alloy. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2021, 73, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, Z.; Qian, C.; Huang, S.; Xiao, H. Investigation of deformation behavior, microstructure evolution, and hot processing map of a new near-α Ti alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 23, 2275–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Liang, C.; Lu, T.; Feng, T.; Niu, H.; Dong, Y.; Liu, X. Investigation on the thermal deformation mechanisms and constitutive model of Ti-55511 titanium alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 6780–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, G.; Huang, H.; Xiao, H.; Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, R. Flow behavior analysis and prediction of flow instability of a lamellar TA10 titanium alloy. Materials Characterization 2022, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.M.; Momeni, A.; Lin, Y.C.; Jafarian, H.R. Dynamic softening mechanism in Ti-13V-11Cr-3Al beta Ti alloy during hot compressive deformation. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2016, 665, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Xiang, W.; Yuan, W. Flow softening and microstructural evolution of near β titanium alloy Ti-55531 during hot compression deformation in the α + β region. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, A.; Shahrani, S.B.; Choma, T.; Zrodowski, L.; Qin, L.; Leung, C.L.A.; Clark, S.J.; Fezzaa, K.; Mi, J.; Lee, P.D. New insights into the mechanism of ultrasonic atomization for the production of metal powders in additive manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing 2024, 83, 104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K.; Qin, L.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, S.; Du, W.; Boller, E.; Rack, A.; Li, M.; Mi, J. Operando study of the dynamic evolution of multiple Fe-rich intermetallics of an Al recycled alloy in solidification by synchrotron X-ray and machine learning. Acta Materialia 2024, 279, 120267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Du, W.; Cipiccia, S.; Bodey, A.J.; Rau, C.; Mi, J. Synchrotron X-ray operando study and multiphysics modelling of the solidification dynamics of intermetallic phases under electromagnetic pulses. Acta Materialia 2024, 265, 119593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, B.; Li, W.; Mi, J. Determining the Critical Fracture Stress of Al Dendrites near the Melting Point via Synchrotron X-ray Imaging. Acta Metallurgica Sinica (English Letters) 2023, 36, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Khong, J.C.; Koe, B.; Luo, S.; Huang, S.; Qin, L.; Cipiccia, S.; Batey, D.; Bodey, A.J.; Rau, C. Multiscale characterization of the 3D network structure of metal carbides in a Ni superalloy by synchrotron X-ray microtomography and ptychography. Scripta Materialia 2021, 193, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Luo, S.; Qin, L.; Shu, D.; Sun, B.; Lunt, A.J.; Korsunsky, A.M.; Mi, J. 3D local atomic structure evolution in a solidifying Al-0.4 Sc dilute alloy melt revealed in operando by synchrotron X-ray total scattering and modelling. Scripta Materialia 2022, 211, 114484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Tan, L.; Gan, B.; Jie, Z.; Qin, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L. Variation of Homogenization Pores during Homogenization for Nickel-Based Single-Crystal Superalloys. Advanced Engineering Materials 2021, 23, 2001547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Song, J.; Hu, H.; Qin, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, C.; Cui, Y.; Tan, Z.; et al. Fast shot speed induced microstructure and mechanical property evolution of high pressure die casting Mg-Al-Zn-RE alloys. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2024, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Qin, L.; Tang, H.; Shu, D.; Yan, W.; Sun, B.; Mi, J. Ultrasound cavitation induced nucleation in metal solidification: An analytical model and validation by real-time experiments. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2021, 80, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, G.; Wang, C.; Chen, L. Thermal Deformation Behavior of Ti-6Mo-5V-3Al-2Fe Alloy. Crystals 2021, 11, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L.; Luo, Y.; Niu, Y.; Shao, Z. High-temperature hot deformation behavior and processing map of Ti-22Al-25Nb alloy. Materials Today Communications 2024, 41, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokry, A.; Gowid, S.; Kharmanda, G. An improved generic Johnson-Cook model for the flow prediction of different categories of alloys at elevated temperatures and dynamic loading conditions. Materials Today Communications 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, P. A comparative study on Johnson-Cook and modified Johnson-Cook constitutive material model to predict the dynamic behavior laser additive manufacturing FeCr alloy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2017, 723, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambirasio, L.; Rizzi, E. On the calibration strategies of the Johnson–Cook strength model: Discussion and applications to experimental data. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2014, 610, 370–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Z. Modeling of Flow Stress of High Titanium Content 6061 Aluminum Alloy Under Hot Compression. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2016, 25, 4081–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Yang, J. Hot deformation behavior and processing map of Al–Si–Mg alloys containing different amount of silicon based on Gleebe-3500 hot compression simulation. Materials & Design (1980-2015) 2015, 65, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Bani, A.; Zarei-Hanzaki, A.; Pishbin, M.H.; Haghdadi, N. A comparative study on the capability of Johnson–Cook and Arrhenius-type constitutive equations to describe the flow behavior of Mg–6Al–1Zn alloy. Mechanics of Materials 2014, 71, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhong, L.; Pan, F. Modeling and application of constitutive model considering the compensation of strain during hot deformation. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2016, 681, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Fan, Q.; Xia, Z.; Hao, A.; Yang, W.; Ji, W.; Cao, H. Constitutive Relationship and Hot Processing Maps of Mg-Gd-Y-Nb-Zr Alloy. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2017, 33, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Rakesh, V.; Sivaprasad, P.V.; Venugopal, S.; Kasiviswanathan, K.V. Constitutive equations to predict high temperature flow stress in a Ti-modified austenitic stainless steel. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2009, 500, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robi, P.S.; Dixit, U.S. Application of neural networks in generating processing map for hot working. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2003, 142, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Liu, H.; Lu, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, W.; Feng, Q.; Jia, B.; Song, K. Effect of rare earth yttrium and the deformation process on the thermal deformation behavior and microstructure of pure titanium for cathode rolls. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 4192–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Hou, M.; Yu, K.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, H. Flow behavior and dynamic recrystallization mechanism of a new near-alpha titanium alloy Ti-0.3 Mo-0.8 Ni-2Al-1.5 Zr. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 30, 3863–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; He, D.; Yang, B.; Han, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, W. Construction and application of a physically-based constitutive model for superplastic deformation of near-α TNW700 titanium alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2025, 34, 2071–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Feng, Z.; Shi, Q.; Yang, B.; Chen, M.; Qi, H.; Wang, X. Study on the warm deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of the MDIFed Ti–6Al–4V titanium alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 8929–8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fe | C | N | H | H | Ti |

| 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.007 | 0.0021 | 0.0021 | Bal. |

| material Constant |

strain rate | |||||||

| 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | |

| α | 0.0119 | 0.0112 | 0.0107 | 0.0105 | 0.0105 | 0.0105 | 0.0105 | 0.0105 |

| Q | 317.1401 | 320.5820 | 315.5531 | 304.7553 | 295.4912 | 283.9743 | 276.3184 | 272.3312 |

| n | 5.5782 | 5.1983 | 4.9145 | 4.6582 | 4.4234 | 4.2371 | 4.0892 | 4.0433 |

| ln A | 34.2532 | 34.7864 | 34.3312 | 33.1813 | 32.1540 | 30.8460 | 29.9552 | 29.4720 |

| α | Q | n | ln A |

| 0.0124 | 303.5464 | 6.1858 | 32.5454 |

| -0.0017 | 168.8368 | -7.9749 | 21.0176 |

| -0.0493 | -132.4121 | 23.8815 | -17.9660 |

| 0.1819 | -2689.0837 | -56.1106 | -292.1581 |

| -0.2362 | 8011.9761 | 73.0744 | 869.1344 |

| 0.1058 | -9079.7051 | -48.186 | -981.0780 |

| 3772.3889 | 13.5021 | 406.9907 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).