Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

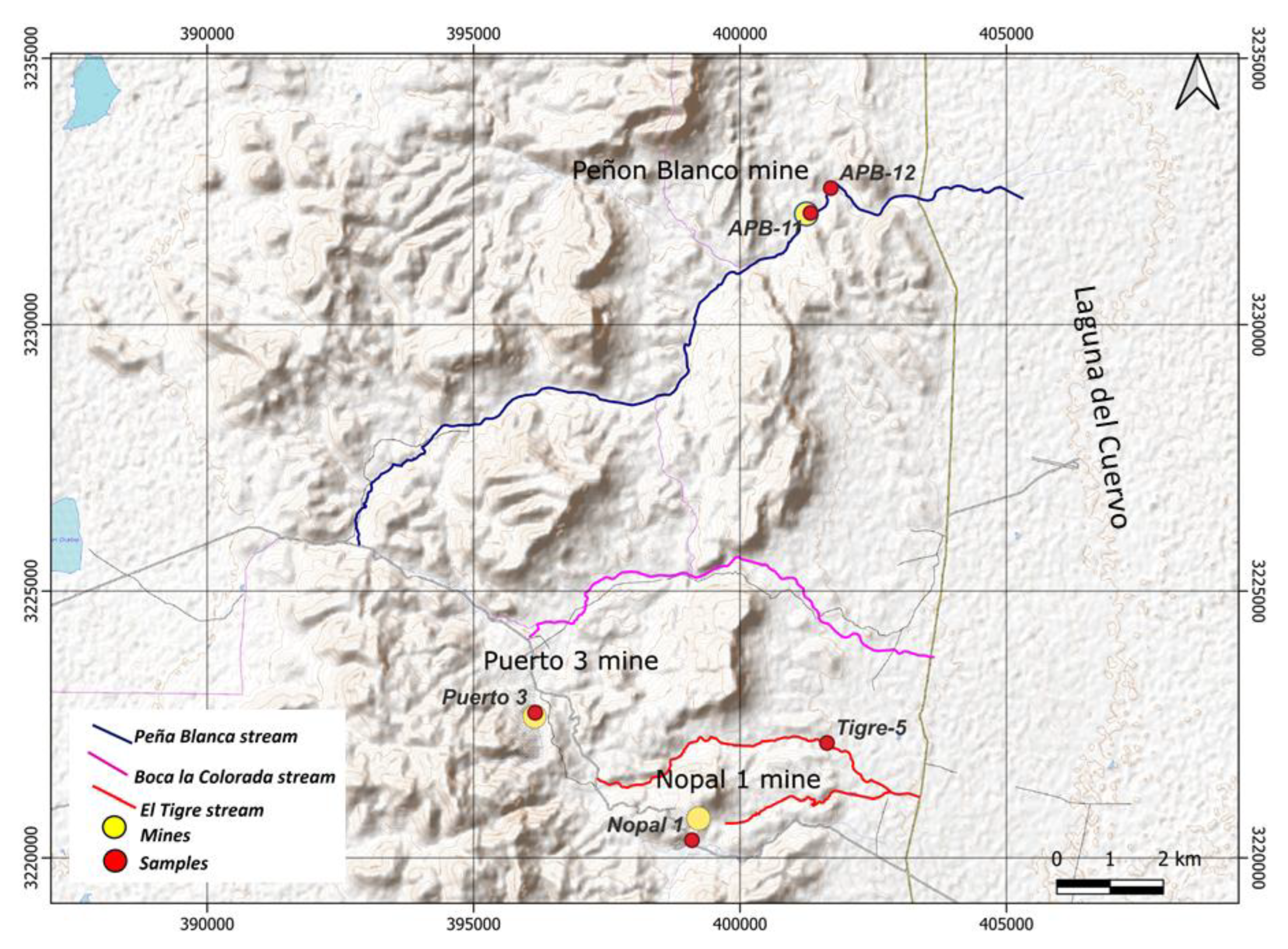

2.1. Sampling and Conditioning of Sediments

2.1. Characterization of Sediment Samples

2.2.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

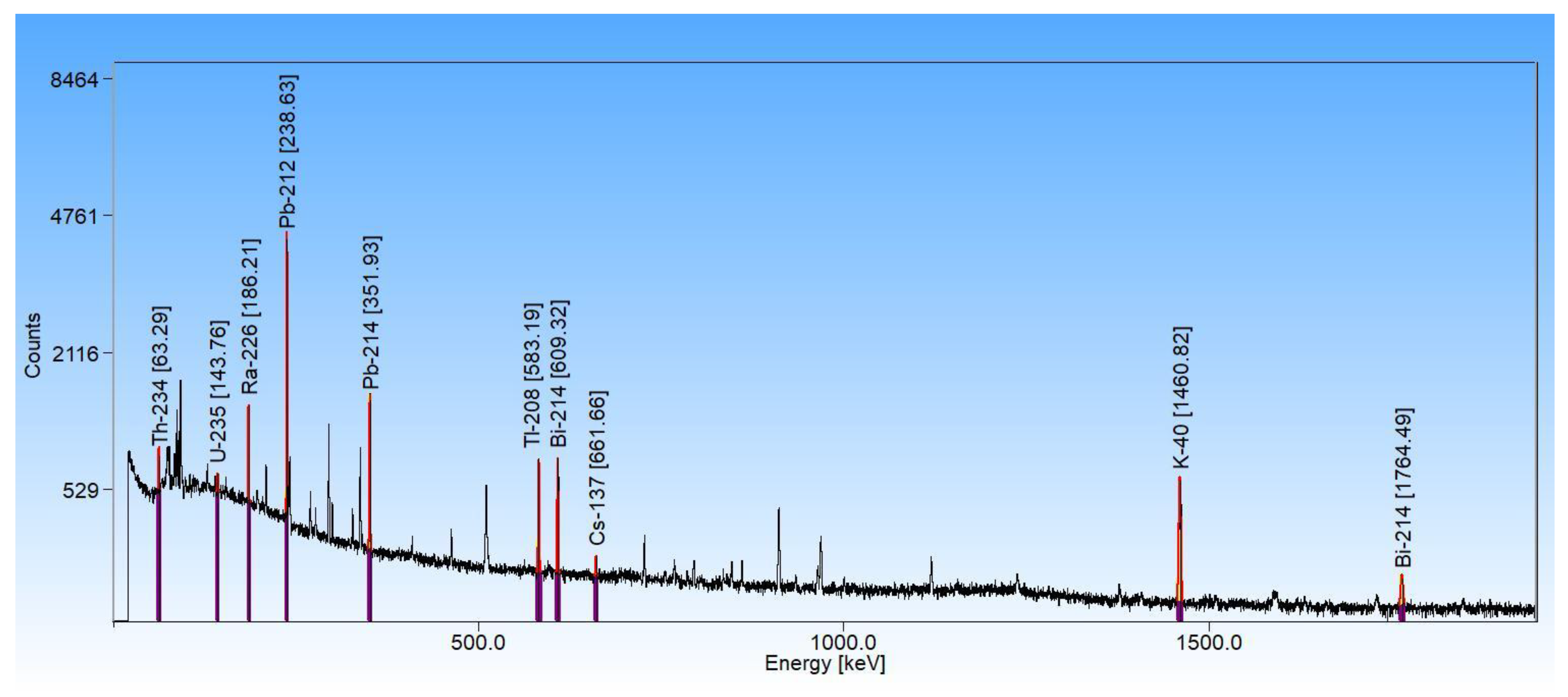

2.2.2. High-Resolution Gamma Spectrometry on Granulometric Fractions of Sediments

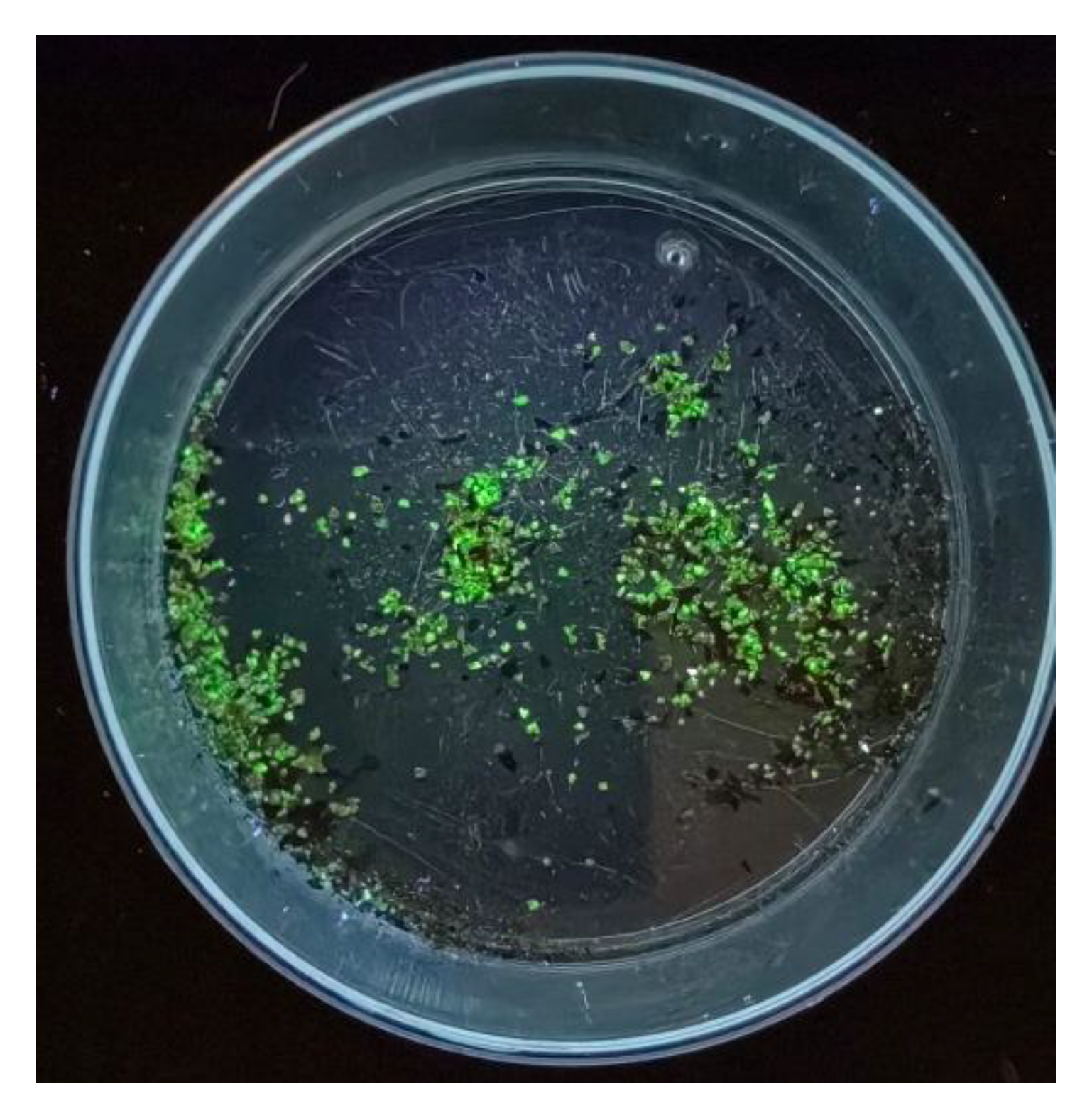

2.3. Selection of Uranium Mineral Particles

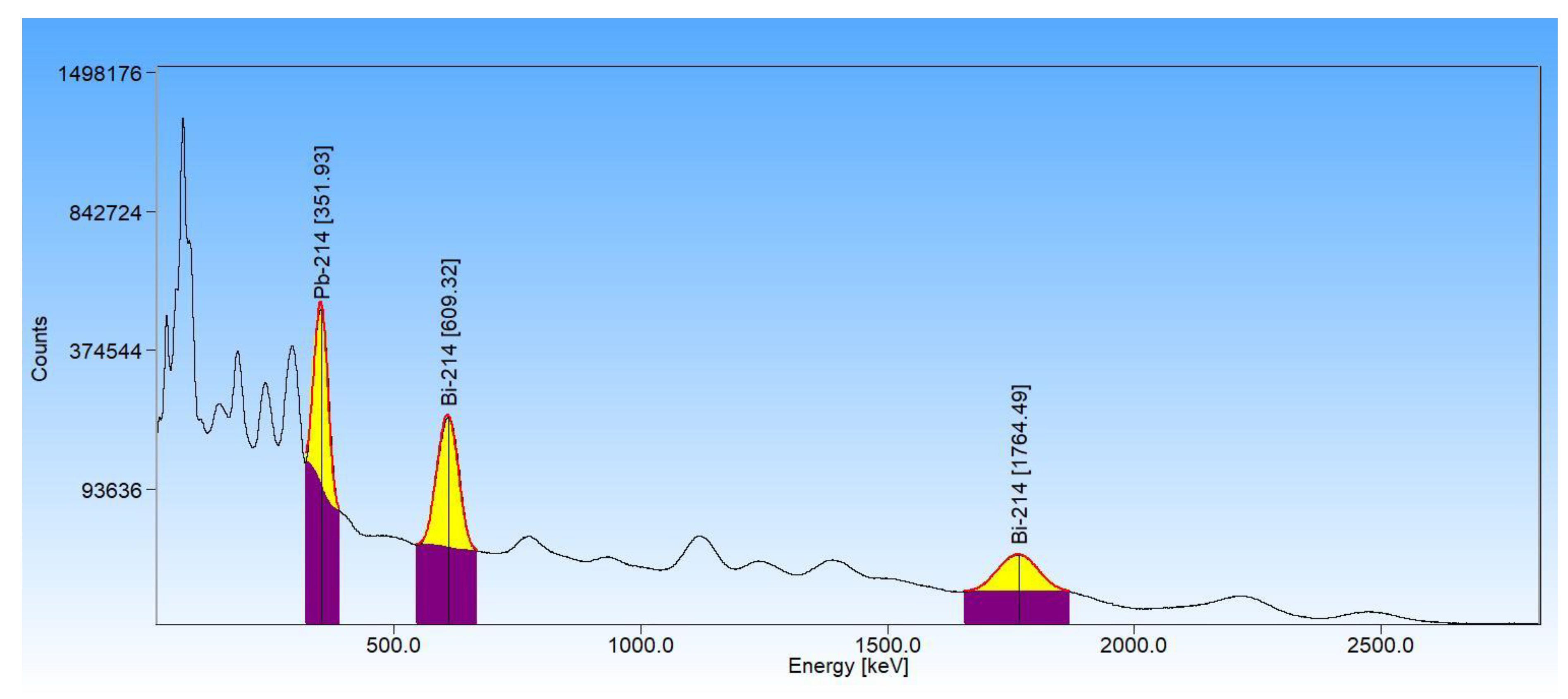

2.4. Quantification of Uranium Particle Density in Fine Sand by Gamma Spectrometry with a Scintillation Detector

- A fine sand sample was selected from a remote position outside the mine drainage pattern, which displayed the lowest uranium activity concentration in the study area obtained separately by γ-ray spectrometry. This sample is a sediment “blank” with the inherent uranium content of igneous rocks, of activity concentration (1.79 ± 0.02) Bq/g.

- From the fraction with grain size 0.279 mm > d > 1.19 mm of sample APB-11, 3336 particles were identified and extracted according to the procedure mentioned in section 2.3, and the resulting total mass was 0.3764 g. The extracted particles were added to an aliquot of the blank matrix. The mixture was homogenized, placed in a vial, and measured in the same geometry. The added activity due to the particles was 0.26 ± 0.02 Bq. The estimated mass per particle was 0.112 ± 0.001 mg, and the assessed 238U activity per particle was Acteach particle = (0.77 ± 0.06) x 10-4 Bq/part.

- An activity concentration reference sample was prepared with the same matrix used for the blank. In this case, a mass of 0.9554 g of pure parauranophane crystals extracted from Peña Blanca was added, and its purity was determined by XRD. The diffraction pattern of parauranophane (URP) reference material analyzed by the Rietveld method is presented in Appendix A, Figure A1. The activity of the added 238U was ActURP = 6565 ± 65 Bq.

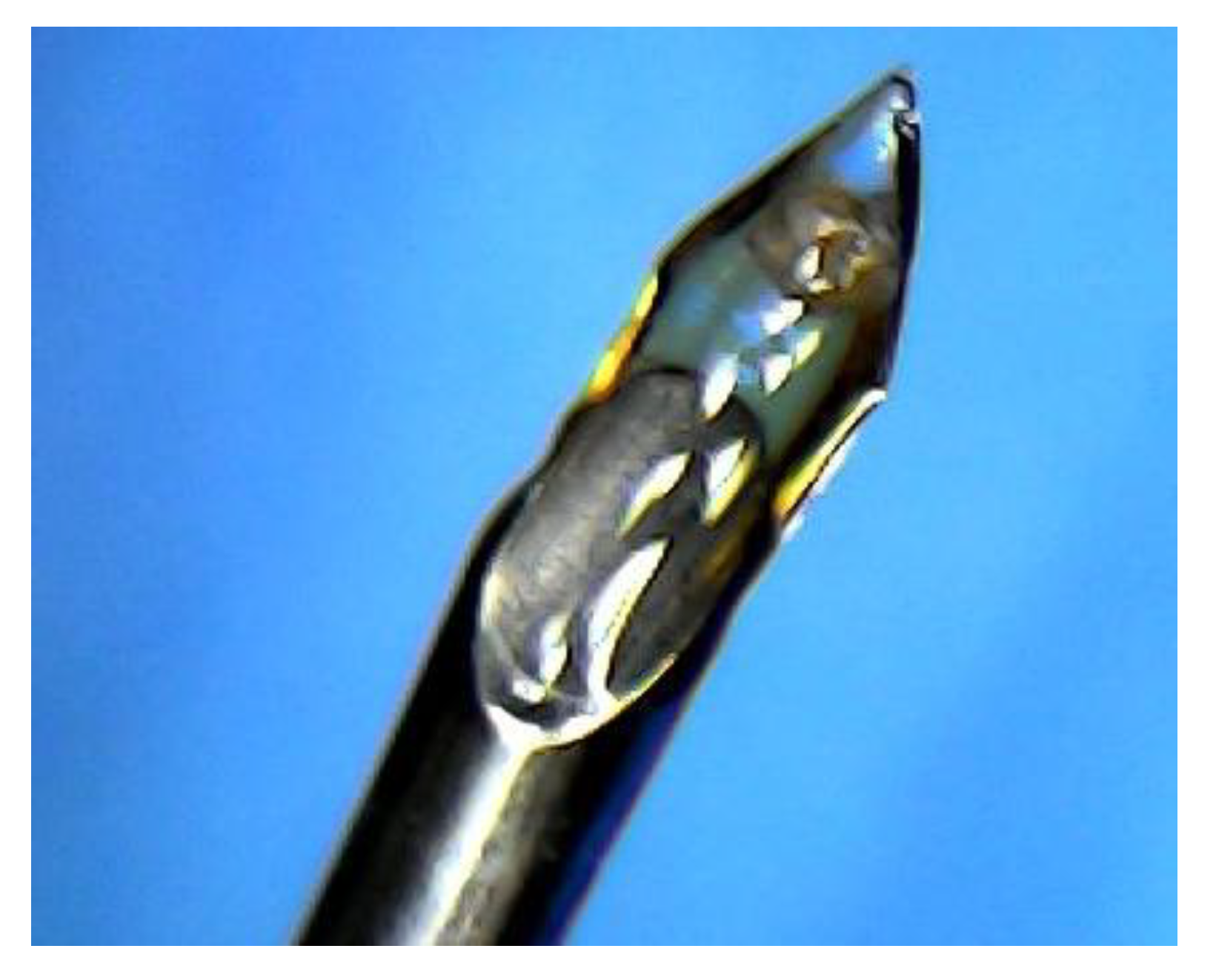

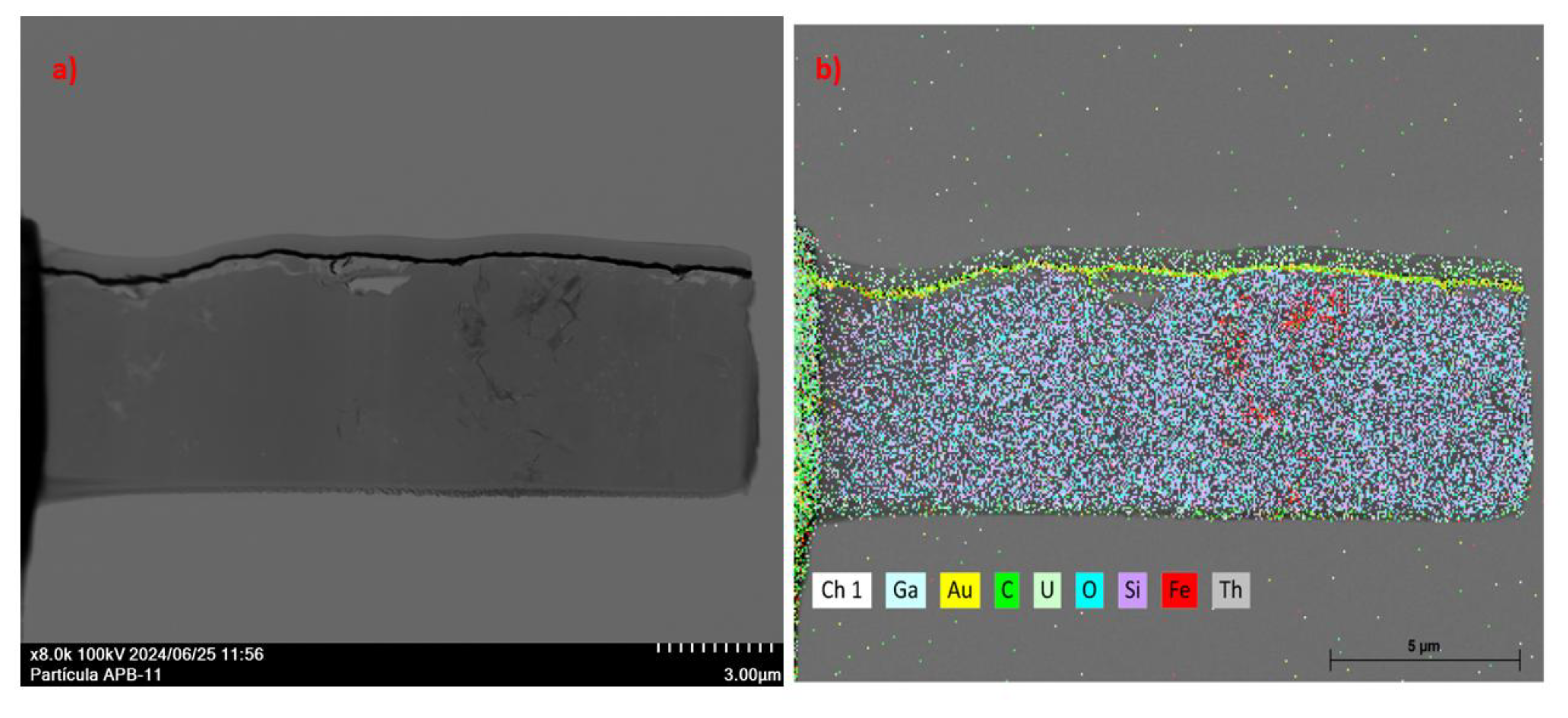

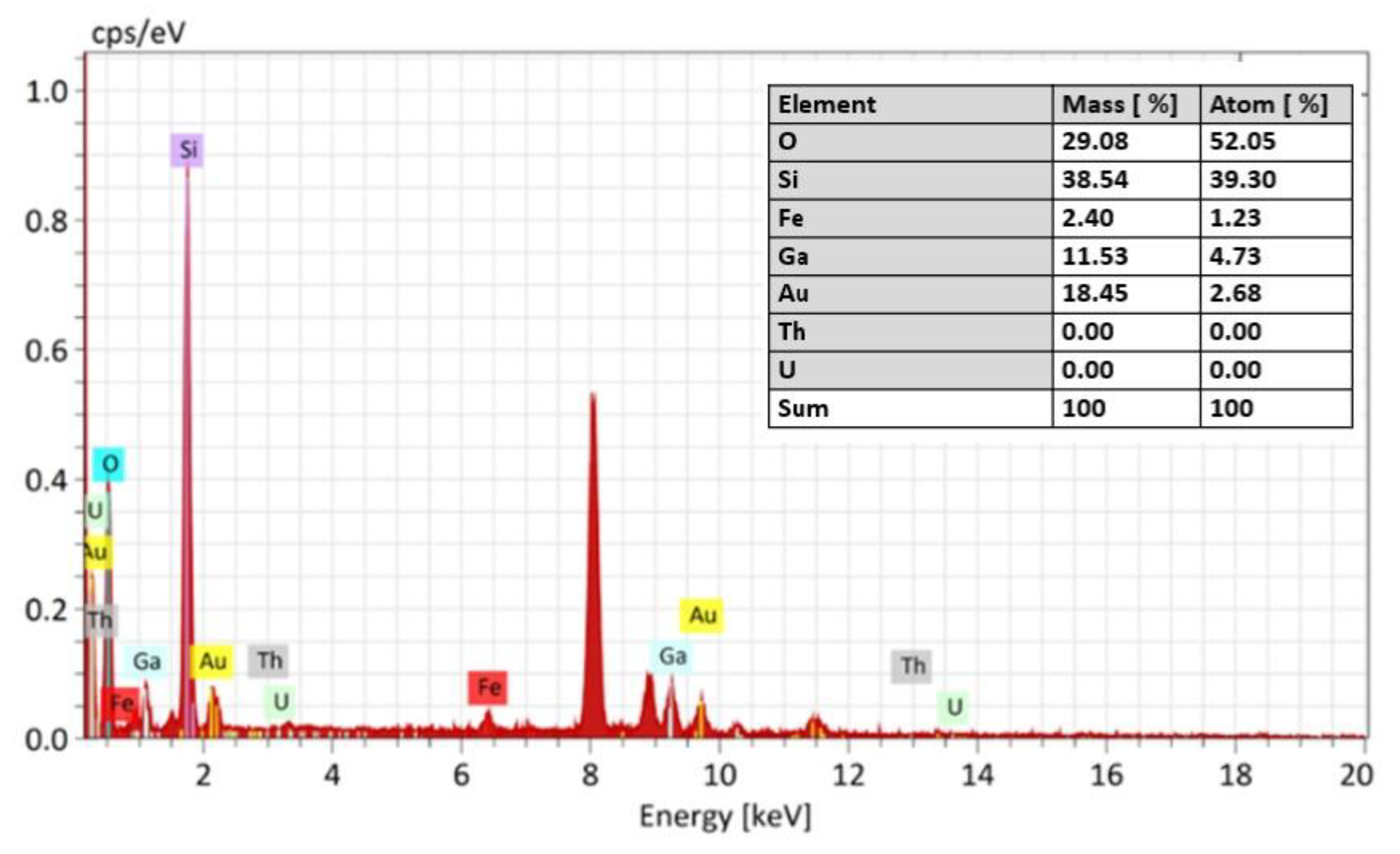

2.5. Morphology and Composition of Individual Particles

2.5.1. Focused Ion Beam and Scanning-Transmission Electron Microscopes

2.5.2. X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure Spectroscopy (XAFS)

2.5.3. CT-µXRF at Diamond Synchrotron

2.5.3.1. Sample Preparation

2.5.3.2. Data Collection at I18 Beamline, Diamond Light Source

3. Results

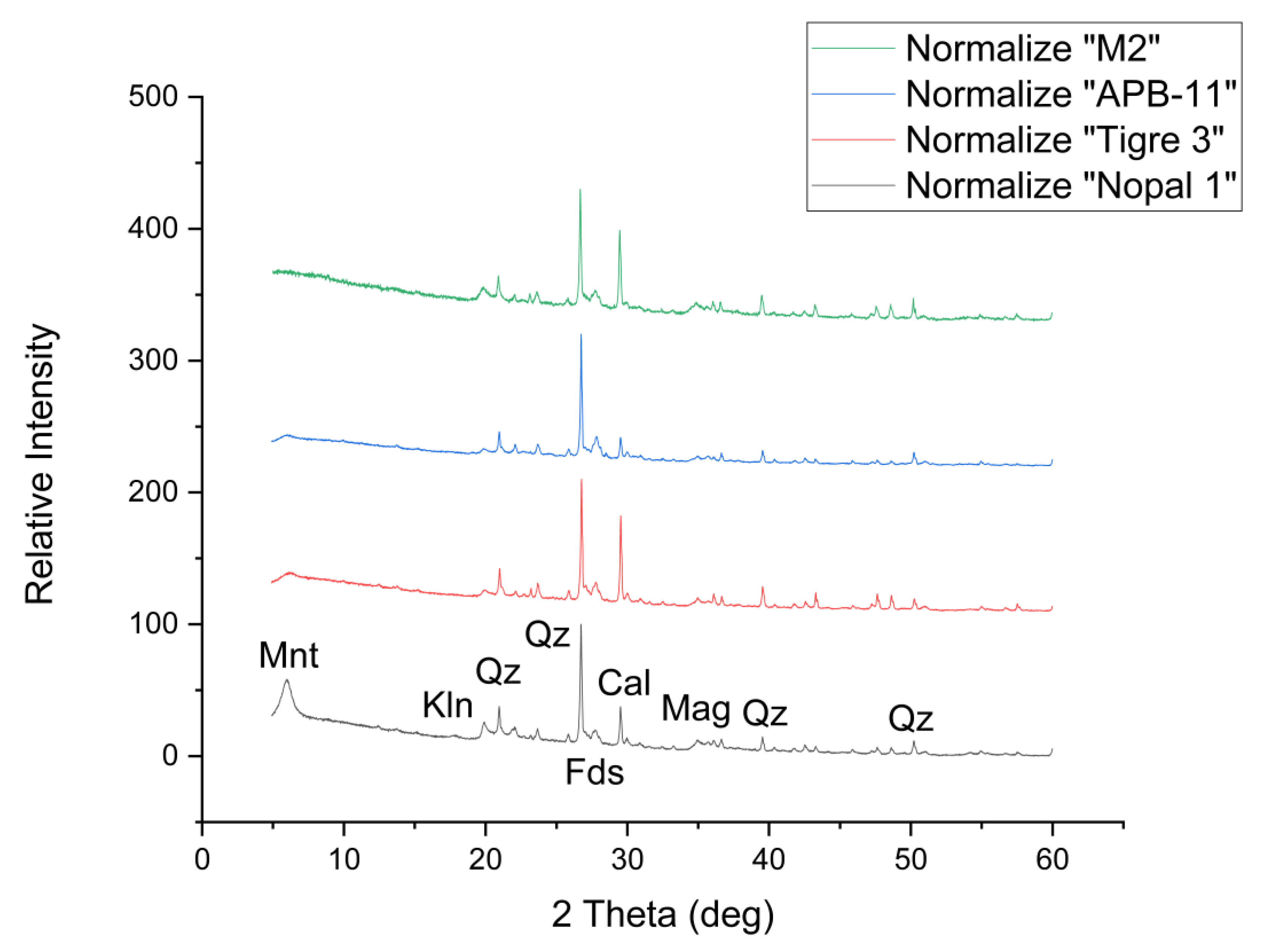

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

3.2. High-Resolution Gamma-Ray Spectrometry

3.3. Quantification of Uranium Particle Density

3.4. Morphology and Composition of Individual Particles

3.4.1. Microscopic Characterization of Fragmented Mineral Particles by FIB-STEM

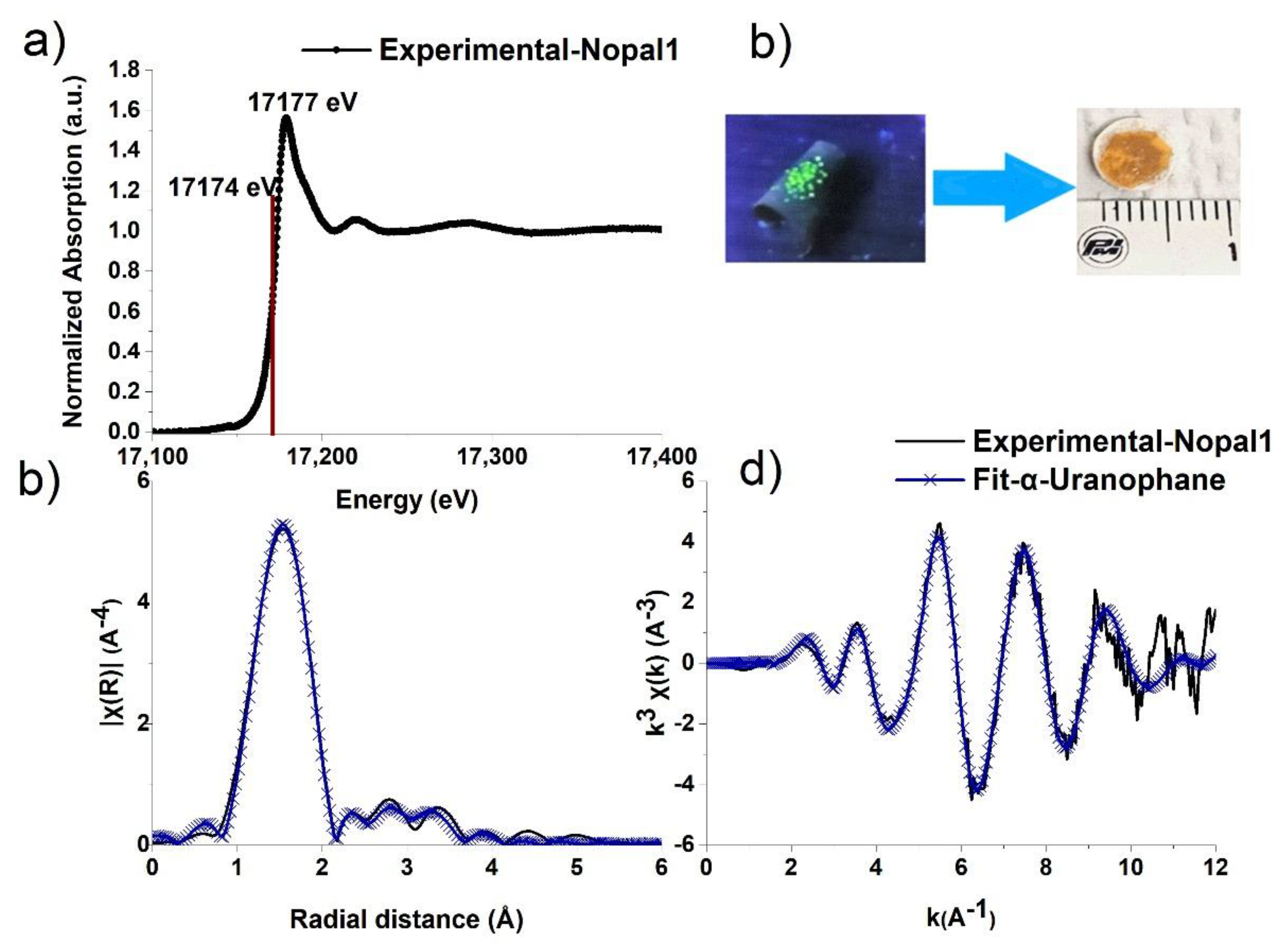

3.4.2. X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure Spectroscopy (XAFS)

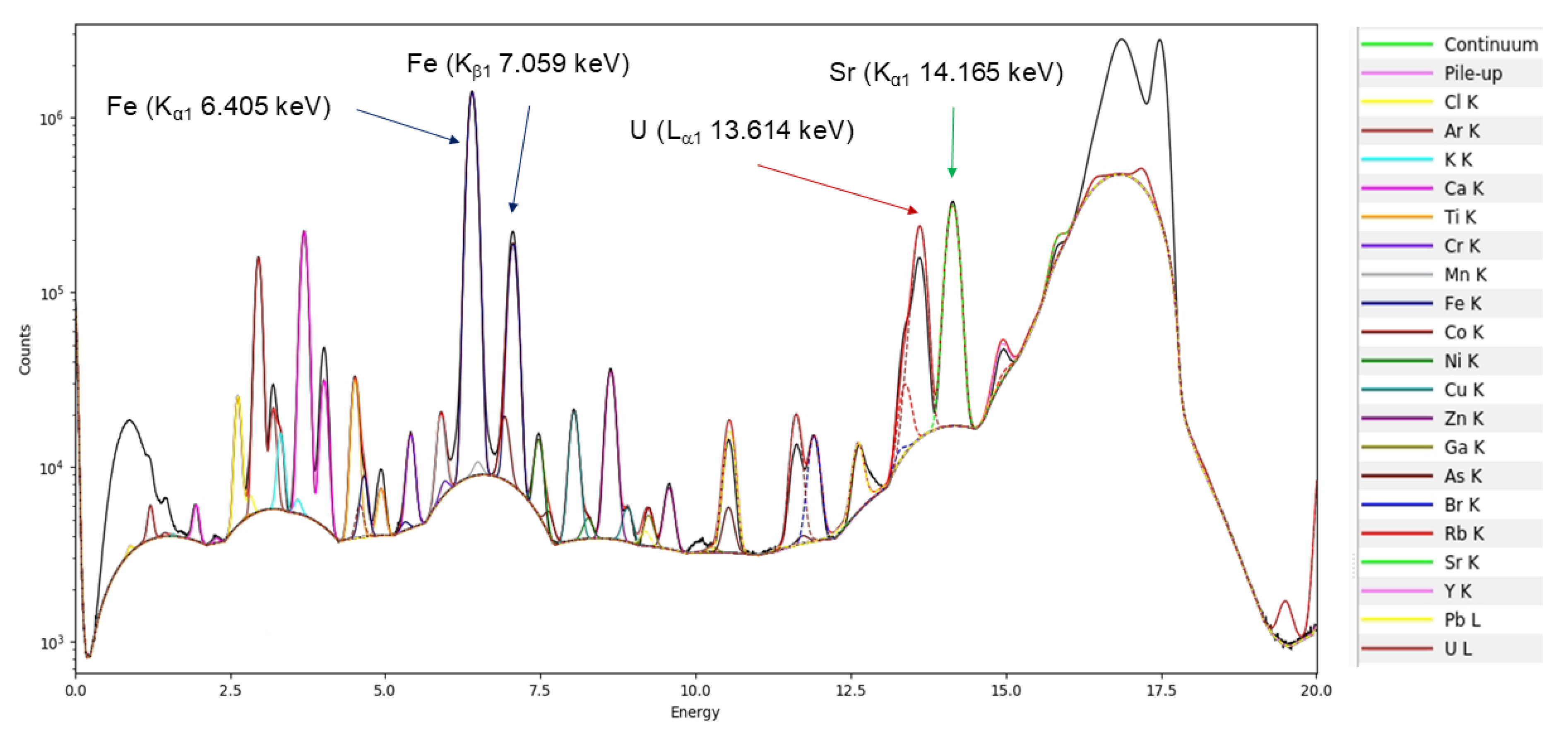

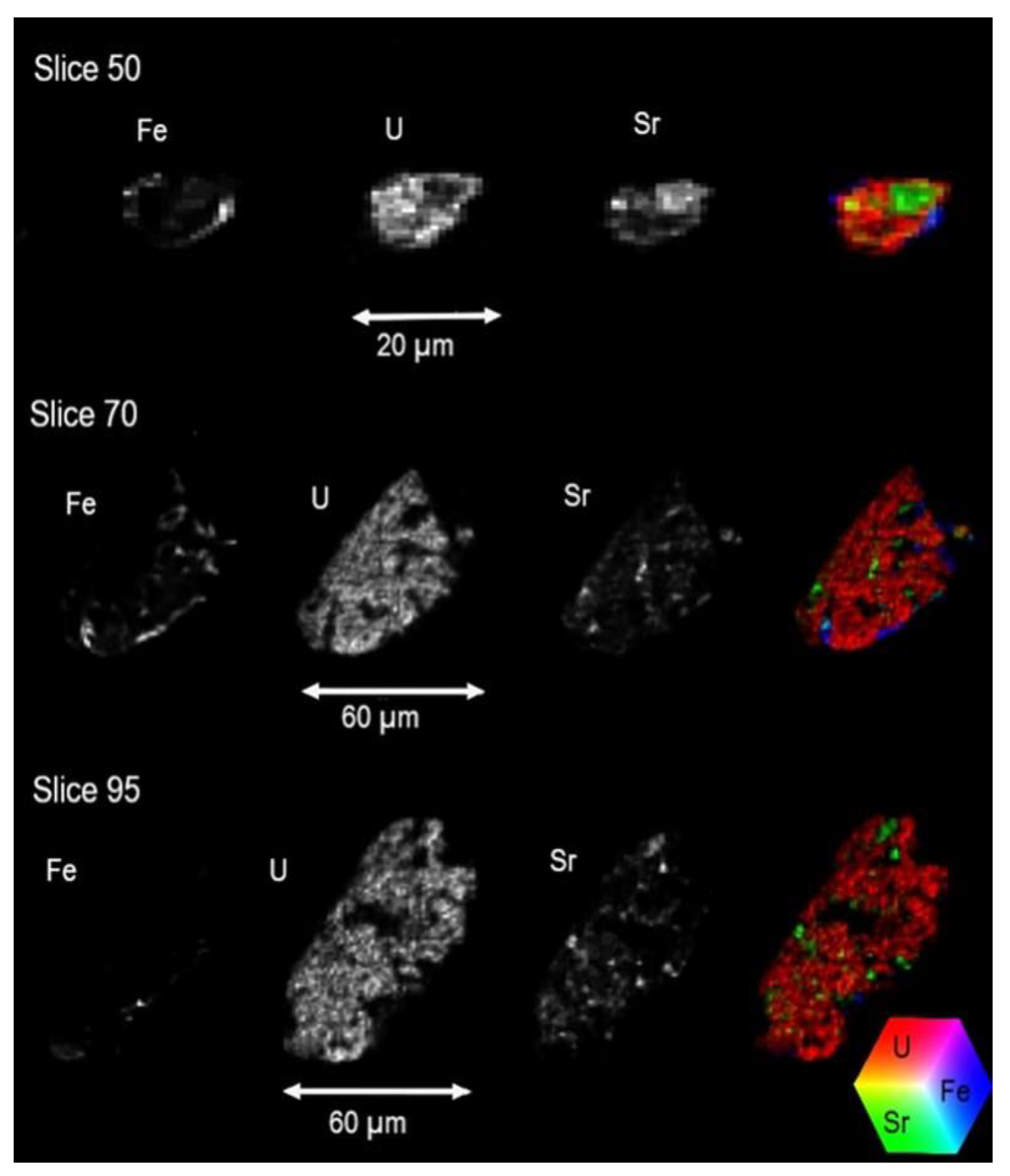

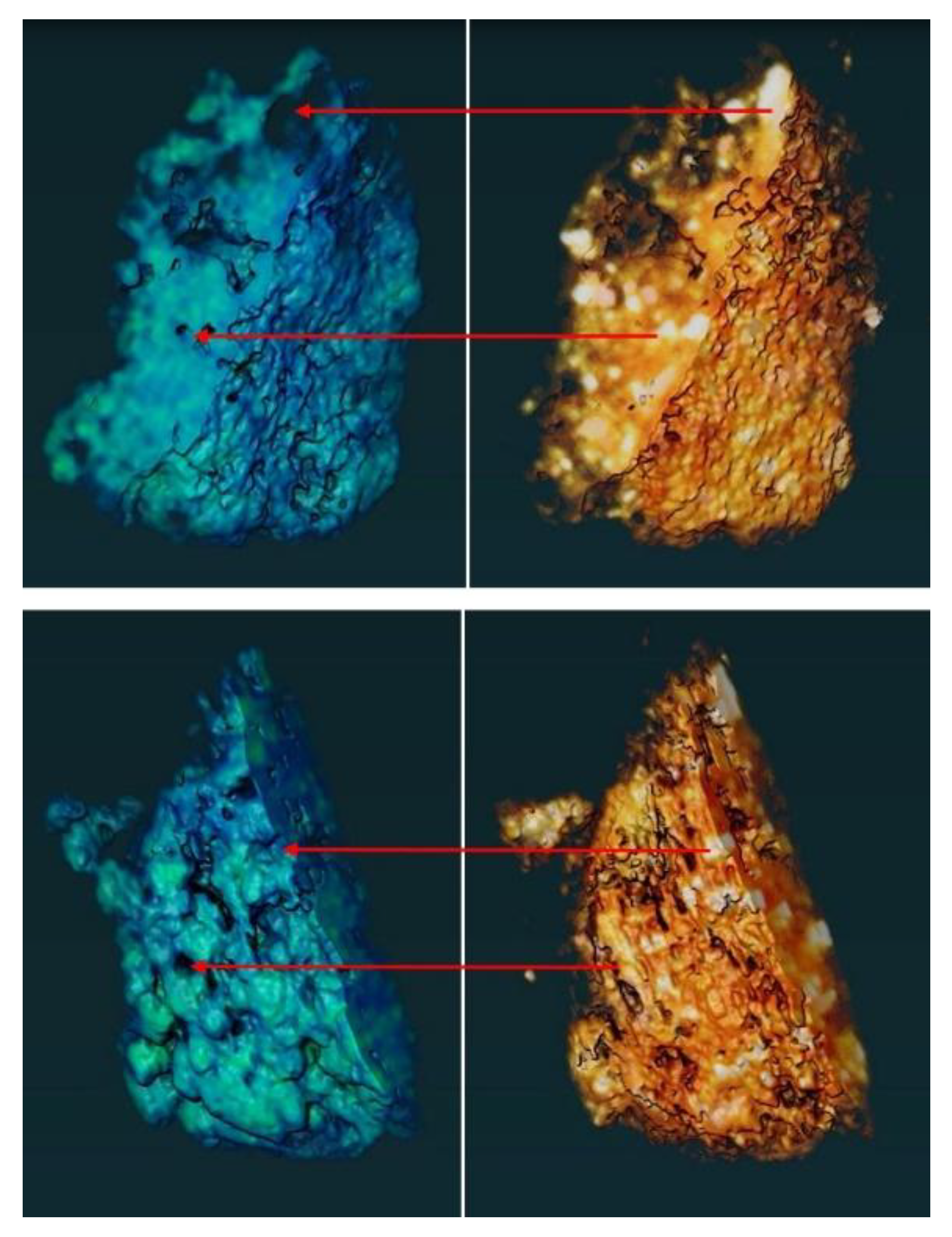

3.4.3. X-Ray Fluorescence MicroTomography (CT-µ-XRF)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPB | Sierra Peña Blanca |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ICP-OES | Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy |

| FIB | Focused ion beam microscopy |

| STEM | Scanning transmission electron microscopy |

| XAFS | X-ray absorption spectrometry |

| XANES | X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure |

| EXAFS | Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure |

| CT-µ-XRF | X-ray fluorescence microtomography |

| CIMAV | Centro de Investigación en Materiales Avanzados |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS | Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| RM | Rietveld method |

| Ab | Albite |

| An | Anorthite |

| Cal | Calcite |

| Hly | Halloysite |

| Kln | Kaolinite |

| Mag | Magnetite |

| Mnt | Montmorillonite |

| Ms | Muscovite |

| Or | Orthoclase |

| Qz | Quartz |

| Sa | Sanidine |

| DL | Detection Limit |

Appendix A. Details of the Mineral Particles Characterization

Appendix A.1. XRD Pattern of Parauranophane.

Appendix A.2. Calculation of Activities of the Isotopes 214Pb and 214Bi by the Relative Method in the HPGe and XtRa Spectrometers

Appendix A.3. Calculation of Particle Concentration in Sediment Samples in the NaI(Tl) Detector

Appendix B. Additional XRD Results

| Location | Total number of samples | Type | Mineral Phase (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qz | Cal | Mnt | Mag | Ab | Sa | Kln | An | |||

| APB This work |

19 | FSC | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| AET Rodríguez- Guerra [27] |

9 | FSD | ||||||||

| CSC | ||||||||||

| FSC | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| ABLC Hernández- Hernández [28] |

7 | FSD | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| CSC | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| FSC | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ABLC Pérez- Reyes [29] |

4 | Mud | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

References

- Angiboust, S.; Fayek, M.; Power, I.M.; Camacho, A.; Calas, G.; Southam, G. Structural and Biological Control of the Cenozoic Epithermal Uranium Concentrations from the Sierra Peña Blanca, Mexico. Miner. Deposita 2012, 47, 859–874. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M. PROVINCIAS FISIOGRAFICAS DE LA REPUBLICA MEXICANA. Bol. Soc. Geológica Mex. 1961, 3–20.

- INEGI Síntesis de Información geográfica del estado de Chihuahua. 2003.

- CONAGUA Actualización de La Disponibilidad Media Anual de Agua En El Acuífero Laguna de Hormigas (0824), Estado de Chihuahua 2020.

- Goodell, P.C. Chihuahua City Uranium Province, Chihuahua, Mexico. Uranium Depos. Volcan. Rocks Proc. Tech. Comm. Meet. Uranium Depos. Volcan. Rockss El Paso TX USA 1984, 97–124.

- Reyes-Cortés, M. Chihuahua City Uranium Province, Chihuahua, Mexico. Deposito Molibdeno Asoc. Con Uranio En Peña Blanca México 1984, 161–174.

- Cárdenas-Flores, D. Volcanic Stratigraphy and U-Mo Mineralization of the Sierra de Peña Blanca District, Chihuahua, México. IAEA 1985.

- Dobson, P.F.; Fayek, M.; Goodell, P.C.; Ghezzehei, T.A.; Melchor, F.; Murrel, M.T.; Oliver, R.; Reyes-Cortés, I.A.; De La Garza, R.; Simmons, A. Stratigraphy of the PB-1 Well, Nopal I Uranium Deposit, Sierra Peña Blanca, Chihuahua, Mexico. Int. Geol. Rev. 2008, 50, 959–974.

- Faudoa, F.G. Modelo de La Evolución de Las Especies Minerales Superficiales de Uranio de La Sierra Peña Blanca, Chihuahua, México. Master´s Thesis, Centro de investigación en Materiales Avanzados: Chihuahua, Chihuahua, 2023.

- George-Aniel, B.; Leroy, J.L.; Poty, B. Volcanogenic Uranium Mineralizations in the Sierra Pena Blanca District, Chihuahua, Mexico; Three Genetic Models. Econ. Geol. 1991, 86, 233–248. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.H. A Climatic Delineation of the ‘Real’ Chihuahuan Desert. J. Arid Environ. 1979, 2, 243–250. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Herrera, C.; Canche Tello, J.G.; Cabral Lares, R.M.; Rodriguez Guerra, Y.; Perez Reyes, V.; Faudoa Gomez, F.G.; Esparza Ponce, H.E.; Reyes Cortez, I.A.; Hernandez Cruz, D.; Loredo Portales, R.; et al. Interpretation of X-ray Absorption Spectra by Synchrotron Radiation of the Uranium Mineral Species Transported by the Main Stream “El Tigre”, in Peña Blanca, Chihuahua, Mexico. Supl. Rev. Mex. Física 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, G. Sedimentology and Stratigraphy; 2. ed., [Nachdr.].; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4051-3592-4.

- Guzmán-Martínez, F.; Arranz-González, J.-C.; Tapia-Téllez, A.; Prazeres, C.; García-Martínez, M.-J.; Jiménez-Oyola, S. Assessment of Potential Contamination and Acid Drainage Generation in Uranium Mining Zones of Peña Blanca, Chihuahua, Mexico. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 386. [CrossRef]

- Schindler, M.; Fayek, M.; Hawthorne, F.C. Uranium-Rich Opal from the Nopal I Uranium Deposit, Peña Blanca, Mexico: Evidence for the Uptake and Retardation of Radionuclides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 187–202. [CrossRef]

- Schindler, M.; Fayek, M.; Courchesne, B.; Kyser, K.; Hawthorne, F.C. Uranium-Bearing Opals: Products of U-Mobilization, Diffusion, and Transformation Processes. Am. Mineral. 2017, 102, 1154–1164. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, Y. Factors Controlling Uranium and Thorium Isotopic Composition of the Streambed Sediments of the River Nile, Egypt. J. King Abdulaziz Univ.-Earth Sci. 2010, 21, 77–103. [CrossRef]

- Chabaux, F.; Bourdon, B.; Riotte, J. Chapter 3 U-Series Geochemistry in Weathering Profiles, River Waters and Lakes. In Radioactivity in the Environment; Elsevier, 2008; Vol. 13, pp. 49–104 ISBN 978-0-08-045012-4.

- Bosia, C.; Chabaux, F.; Pelt, E.; France-Lanord, C.; Morin, G.; Lavé, J.; Stille, P. U–Th–Ra Variations in Himalayan River Sediments (Gandak River, India): Weathering Fractionation and/or Grain-Size Sorting? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 193, 176–196. [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.A.S. The Uranium Geochemistry of Latten Volcanic National Park, California. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1955, Volume 8, Pages 74-85. [CrossRef]

- Hurley, P.M. DIRECT RADIOMETRIC MEASUREMENT BY GAMMA-RAY SCINTILLATION SPECTROMETER: PART I: URANIUM AND THORIUM SERIES IN EQUILIBRIUM. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1956, 67, 395–404. [CrossRef]

- Hurley, P.M. DIRECT RADIOMETRIC MEASUREMENT BY GAMMA-RAY SCINTILLATION SPECTROMETER: PART II: URANIUM, THORIUM, AND POTASSIUM IN COMMON ROCKS. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1956, 67, 405–412. [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.A.S.; Richardson, J.E.; Templeton, C.C. Determinations of Thorium and Uranium in Sedimentary Rocks by Two Independent Methods. Geochim. Cosmochim. 1958, Vol. 13, 270 to 279. [CrossRef]

- Mero, J.L. USES OF THE GAMMA-RAY SPECTROMETER IN MINERAL EXPLORATION. GEOPHYSICS 1960, 25, 1054–1076. [CrossRef]

- CNSNS Comision Nacional de Seguridad Nuclear y Salvaguardias: 1965. p. P 67.

- Colmenero S., L.; Montero C., M.E.; Villalba, L. Natural Radioactivity in Soils of the Main Cities of the State of Chihuahua; Radiactividad Natural En Suelos de Las Principales Ciudades Del Estado de Chihuahua.; Guadalajara, México, July 2003; p. 8 pages.

- Rodríguez- Guerra, Y. Transporte de Isótopos Radiactivos de La Serie Del Uranio Desde Peña Blanca Hasta Laguna Del Cuervo a Través Del Arroyo El Tigre, Chihuahua. Master´s Thesis, Centro de investigación en Materiales Avanzados: Chihuahua, Chihuahua, 2023.

- Hernández-Hernández, D. Transporte y Equilibrio Radioactivo Del Uranio Desde El Yacimiento de Peña Blanca Hasta Laguna Del Cuervo, Chihuahua. Master´s Thesis, Centro de investigación en Materiales Avanzados: Chihuahua, Chihuahua, 2019.

- Pérez-Reyes, V.; Cabral-Lares, R.M.; Méndez-García, C.G.; Caraveo-Castro, C.D.R.; Reyes-Cortés, I.A.; Carrillo-Flores, J.; Montero-Cabrera, M.E. Transport and Concentration of Uranium Isotopes in the Laguna Del Cuervo, Chihuahua, Mexico. Supl. Rev. Mex. Física 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Reyes, V.; Cabral-Lares, R.M.; Canche-Tello, J.G.; Rentería-Villalobos, M.; González-Sánchez, G.; Carmona-Lara, B.P.; Hernández-Herrera, C.; Faudoa-Gómez, F.; Rodríguez-Guerra, Y.; Vázquez-Olvera, G.; et al. Uranium Mineral Transport in the Peña Blanca Desert: Dissolution or Fragmentation? Simulation in Sediment Column Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 609. [CrossRef]

- Salbu, B.; Lind, O.C. Analytical Techniques for Charactering Radioactive Particles Deposited in the Environment. J. Environ. Radioact. 2020, 211, 106078. [CrossRef]

- Lind, O.C.; Salbu, B.; Janssens, K.; Proost, K.; García-León, M.; García-Tenorio, R. Characterization of U/Pu Particles Originating from the Nuclear Weapon Accidents at Palomares, Spain, 1966 and Thule, Greenland, 1968. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 376, 294–305. [CrossRef]

- Pöllänen, R.; Ketterer, M.E.; Lehto, S.; Hokkanen, M.; Ikäheimonen, T.K.; Siiskonen, T.; Moring, M.; Rubio Montero, M.P.; Martín Sánchez, A. Multi-Technique Characterization of a Nuclearbomb Particle from the Palomares Accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2006, 90, 15–28. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ramos, M.C.; Hurtado, S.; Chamizo, E.; García-Tenorio, R.; León-Vintró, L.; Mitchell, P.I. 239 Pu,240 Pu, and241 Am Determination in Hot Particles by Low Level Gamma-Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4247–4252. [CrossRef]

- Sancho, C.; García-Tenorio, R. Radiological Evaluation of the Transuranic Remaining Contamination in Palomares (Spain): A Historical Review. J. Environ. Radioact. 2019, 203, 55–70. [CrossRef]

- López, J.G.; Jiménez-Ramos, M.C.; García-León, M.; García-Tenorio, R. Characterisation of Hot Particles Remaining in Soils from Palomares (Spain) Using a Nuclear Microprobe. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2007, 260, 343–348. [CrossRef]

- Raiwa, M.; Büchner, S.; Kneip, N.; Weiß, M.; Hanemann, P.; Fraatz, P.; Heller, M.; Bosco, H.; Weber, F.; Wendt, K.; et al. Actinide Imaging in Environmental Hot Particles from Chernobyl by Rapid Spatially Resolved Resonant Laser Secondary Neutral Mass Spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2022, 190, 106377. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Shao, Y.; Luo, M.; Xu, D.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Ma, L. Research Progress on the Analysis and Application of Radioactive Hot Particle. J. Environ. Radioact. 2023, 270, 107313. [CrossRef]

- Price, S.W.T.; Ignatyev, K.; Geraki, K.; Basham, M.; Filik, J.; Vo, N.T.; Witte, P.T.; Beale, A.M.; Mosselmans, J.F.W. Chemical Imaging of Single Catalyst Particles with Scanning μ-XANES-CT and μ-XRF-CT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 521–529. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Moreno, S. XAFS Data Collection: An Integrated Approach to Delivering Good Data. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2012, 19, 863–868. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento-Dias, B.L.; Araujo, O.M.O.; Machado, A.S.; Oliveira, D.F.; Anjos, M.J.; Lopes, R.T.; Assis, J.T. Analysis of Two Meteorite Fragments (Lunar and Martian) Using X-Ray Microfluorescence and X-Ray Computed Microtomography Techniques. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2019, 152, 156–161. [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.; Etschmann, B.; Ram, R.; Ignatyev, K.; Gervinskas, G.; Conradson, S.D.; Cumberland, S.; Wong, V.N.L.; Brugger, J. The Nature of Pu-Bearing Particles from the Maralinga Nuclear Testing Site, Australia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10698. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.G.; Louvel, M.; Cipiccia, S.; Jones, C.P.; Batey, D.J.; Hallam, K.R.; Yang, I.A.X.; Satou, Y.; Rau, C.; Mosselmans, J.F.W.; et al. Provenance of Uranium Particulate Contained within Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Unit 1 Ejecta Material. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2801. [CrossRef]

- ISO-18400-102 International Organization for Standardization. 2017, p. 71.

- Wentworth, C.K. A Scale of Grade and Class Terms for Clastic Sediments. J. Geol. 1922, 30, 377–392. [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L. The Distinction between Grain Size and Mineral Composition in Sedimentary-Rock Nomenclature. J. Geol. 1954, 62, 344–359. [CrossRef]

- Switzer, A.D. 14.19 Measuring and Analyzing Particle Size in a Geomorphic Context. In Treatise on Geomorphology; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 224–242 ISBN 978-0-08-088522-3.

- Rodríguez-Carbajal, J. Recent Advances in Magnetic Structure Determination by Neutron Powder Diffraction. Phys. B Condens. Matter 1993, Volume 192, Issues 1–2, Pages 55-69.

- Gilmore, G. Practical Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy; Second Edition.; John Wiley & Sons., 2008;.

- Townsend, L.T.; Smith, K.F.; Winstanley, E.H.; Morris, K.; Stagg, O.; Mosselmans, J.F.W.; Livens, F.R.; Abrahamsen-Mills, L.; Blackham, R.; Shaw, S. Neptunium and Uranium Interactions with Environmentally and Industrially Relevant Iron Minerals. Minerals 2022, 12, 165. [CrossRef]

- Ravel, B.; Newville, M. ATHENA , ARTEMIS , HEPHAESTUS : Data Analysis for X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy Using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2005, 12, 537–541. [CrossRef]

- Solé, V.A.; Papillon, E.; Cotte, M.; Walter, Ph.; Susini, J. A Multiplatform Code for the Analysis of Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectra. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2007, 62, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Gürsoy, D.; De Carlo, F.; Xiao, X.; Jacobsen, C. TomoPy: A Framework for the Analysis of Synchrotron Tomographic Data. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2014, 21, 1188–1193. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [CrossRef]

- Basham, M.; Filik, J.; Wharmby, M.T.; Chang, P.C.Y.; El Kassaby, B.; Gerring, M.; Aishima, J.; Levik, K.; Pulford, B.C.A.; Sikharulidze, I.; et al. Data Analysis WorkbeNch ( DAWN ). J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2015, 22, 853–858. [CrossRef]

- Group F. AVIZO 3D Analysis Software.

- Bès, R.; Rivenet, M.; Solari, P.-L.; Kvashnina, K.O.; Scheinost, A.C.; Martin, P.M. Use of HERFD–XANES at the U L3 - and M4 -Edges To Determine the Uranium Valence State on [Ni(H2 O)4 ]3 [U(OH,H2 O)(UO2 )8 O12 (OH)3 ]. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 4260–4270. [CrossRef]

- Catalano, J.G.; Brown Jr., G.E. Analysis of Uranyl-Bearing Phases by EXAFS Spectroscopy: Interferences, Multiple Scattering, Accuracy of Structural Parameters, and Spectral Differences. Am. Mineral. 2004, Volume 89, pages 1004-1021, doi:DOI: 10.2138/am-2004-0711.

- Lloyd, N.S.; Mosselmans, J.F.W.; Parrish, R.R.; Chenery, S.R.N.; Hainsworth, S.V.; Kemp, S.J. The Morphologies and Compositions of Depleted Uranium Particles from an Environmental Case-Study. Mineral. Mag. 2009, 73, 495–510. [CrossRef]

- Ginderow, D. Structure de l’uranophane alpha, Ca(UO2)2(SiO3OH)2.5H2O. Acta Crystallogr. C 1988, 44, 421–424. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.D. Uranium Chemistry in Soils and Sediments. In Developments in Soil Science; Elsevier, 2010; Vol. 34, pp. 411–466 ISBN 978-0-444-53261-9.

- Brown, C.F.; Serne, R.J.; Catalano, J.G.; Krupka, K.M.; Icenhower, J.P. Mineralization of Contaminant Uranium and Leach Rates in Sediments from Hanford, Washington. Appl. Geochem. 2010, 25, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.G.; Chow, T.J. The Strontium-Calcium Atom Ratio in Carbonate-Secreting Marine Organisms. Pap. Mar. Biol. Oceanogr. 1955, Suppl. vol. 3 of Deep-Sea Research, 20-39.

- Turekus, K.K.; Kulp, J.L. The Geochemistry of Strontium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1956, 245-296.

- Montero, M.E.; Aspiazu, J.; Pajón, J.; Miranda, S.; Moreno, E. PIXE Study of Cuban Quaternary Paleoclimate Geological Samples and Speleothems. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2000, 52, 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Hu, J.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamada, M.; Rahman, M.S.; Yang, G. Application of Synchrotron Radiation and Other Techniques in Analysis of Radioactive Microparticles Emitted from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident-A Review. J. Environ. Radioact. 2019, 196, 29–39. [CrossRef]

- Poliakova, T.; Weiss, M.; Trigub, A.; Yapaskurt, V.; Zheltonozhskaya, M.; Vlasova, I.; Walther, C.; Kalmykov, S. Chernobyl Fuel Microparticles: Uranium Oxidation State and Isotope Ratio by HERFD-XANES and SIMS. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.P.; Child, D.P.; Collins, R.; Cook, M.; Davis, J.; Hotchkis, M.A.C.; Howard, D.L.; Howell, N.; Ikeda-Ohno, A.; Young, E. Radioactive Particles from a Range of Past Nuclear Events: Challenges Posed by Highly Varied Structure and Composition. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 842, 156755. [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, I.; Lind, O.C.; Hansen, E.L.; Janssens, K.; Salbu, B. Characterization of Radioactive Particles from the Dounreay Nuclear Reprocessing Facility. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138488. [CrossRef]

| Author | Sample | Stream | Mineral Phase (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qz | Cal | Mnt | Mag | Ab | Sa | Kln | An | |||

| This work | APB-11 | APB | 26.7 (0.2) | 8.4(0.2) | 4.1(0.2) | 2.6(0.2) | 32.6(0.7) | 15.8(0.7) | 3.9(0.9) | 5.3(0.9) |

| Rodríguez- Guerra [27] | Tigre 3 | AET | 19.8(0.4) | 16.(0.9) | 1.0(0.2) | 1.0(0.5) | 10.4(0.1) | 11.2(0.4) | 1.8(0.5) | - |

| Rodríguez- Guerra [27] | Nopal 1 | AET | 26.7(0.3) | 9.0(0.7) | 11.0(0.9) | 2.3(0.7) | 12.3(0.1) | 9.6(0.1) | 4.3(0.9) | - |

| Pérez- Reyes [29] | M2 | ABLC | 23.5(0.7) | 22.8(0.4) | - | - | - | 22.7(0.9) | 14.7(0.2) | 16(1) |

| Author | Stream | Granulometry | Activity concentration of 214Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest AConc | Lowest AConc | |||

| This work | APB | FSC | 100±2 | 50±1 |

| CSC | 77±2 | 51±1 | ||

| FSD | 51* | 51* | ||

| Rodríguez- Guerra [27] | AET | FSC | 133±2 | 76±2 |

| FSD | 217±1 | 71±1 | ||

| Hernández- Hernández [28] | ABLC | FSC | 79±1 | 33±1 |

| CSC | 71±1 | 31±1 | ||

| Sample | Particle density (g-1) |

|---|---|

| Puerto 3 | 2500±250 |

| Nopal 1-d | 828±82 |

| APB-11 | 386±39 |

| APB-12 | 187±18 |

| Tigre-5 | 124±12 |

| Name | N | S02 | σ2(Å2) | E0 | ΔR | Reff(Å) | Reff+ΔR(Å) | Uncertainty (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U_Oax | 2 | 1.05 | 0.0053(6) | 9 | 0.009 | 1.8045 | 1.814 | 0.004 |

| U_Oeq1 | 1 | 1.05 | 0.004(1) | 9 | -0.04 | 2.2411 | 2.201 | 0.01 |

| U_Oeq2 | 2 | 1.05 | 0.004(1) | 9 | -0.04 | 2.2952 | 2.255 | 0.01 |

| U_Oeq3 | 2 | 1.05 | 0.009(5) | 9 | -0.056 | 2.4498 | 2.394 | 0.019 |

| U_Si | 1 | 1.05 | 0.012(3) | 9 | 0.03 | 3.1444 | 3.174 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).