Submitted:

22 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

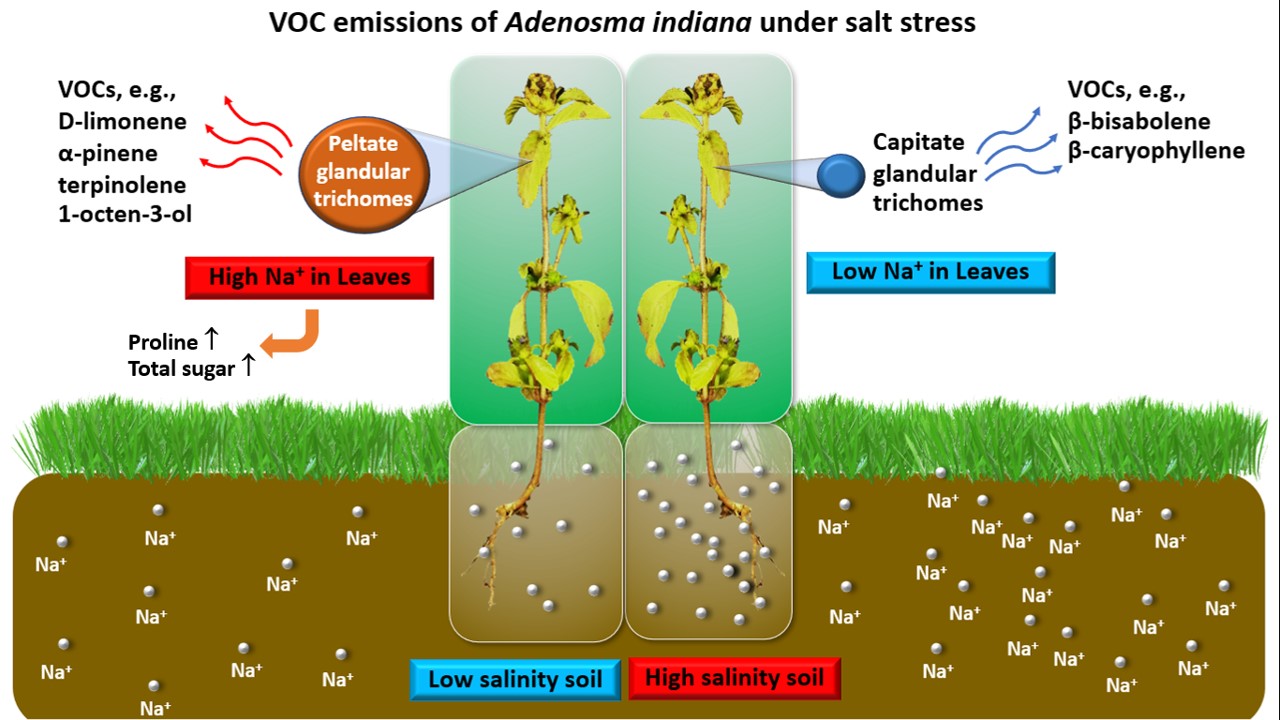

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

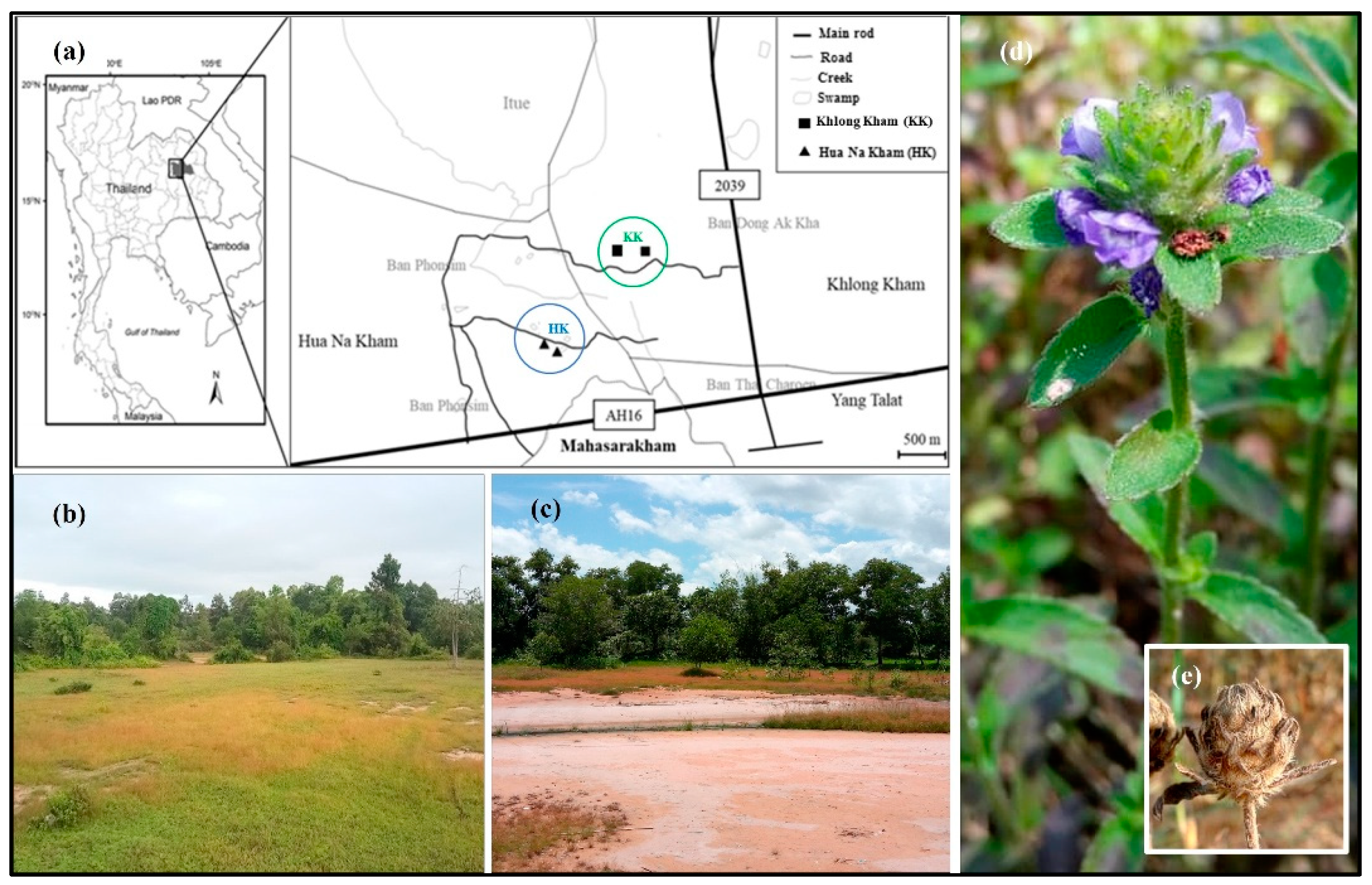

2.1. Study Site Selection and Experimental Design

2.2. Soil Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. Plant Sample Collection and Preparation

2.4. Plant Growth Analysis

2.5. Ion Concentration Analysis in Plant Tissues

2.6. Photosynthetic Pigment Analysis

2.7. Compatible Solute Analysis

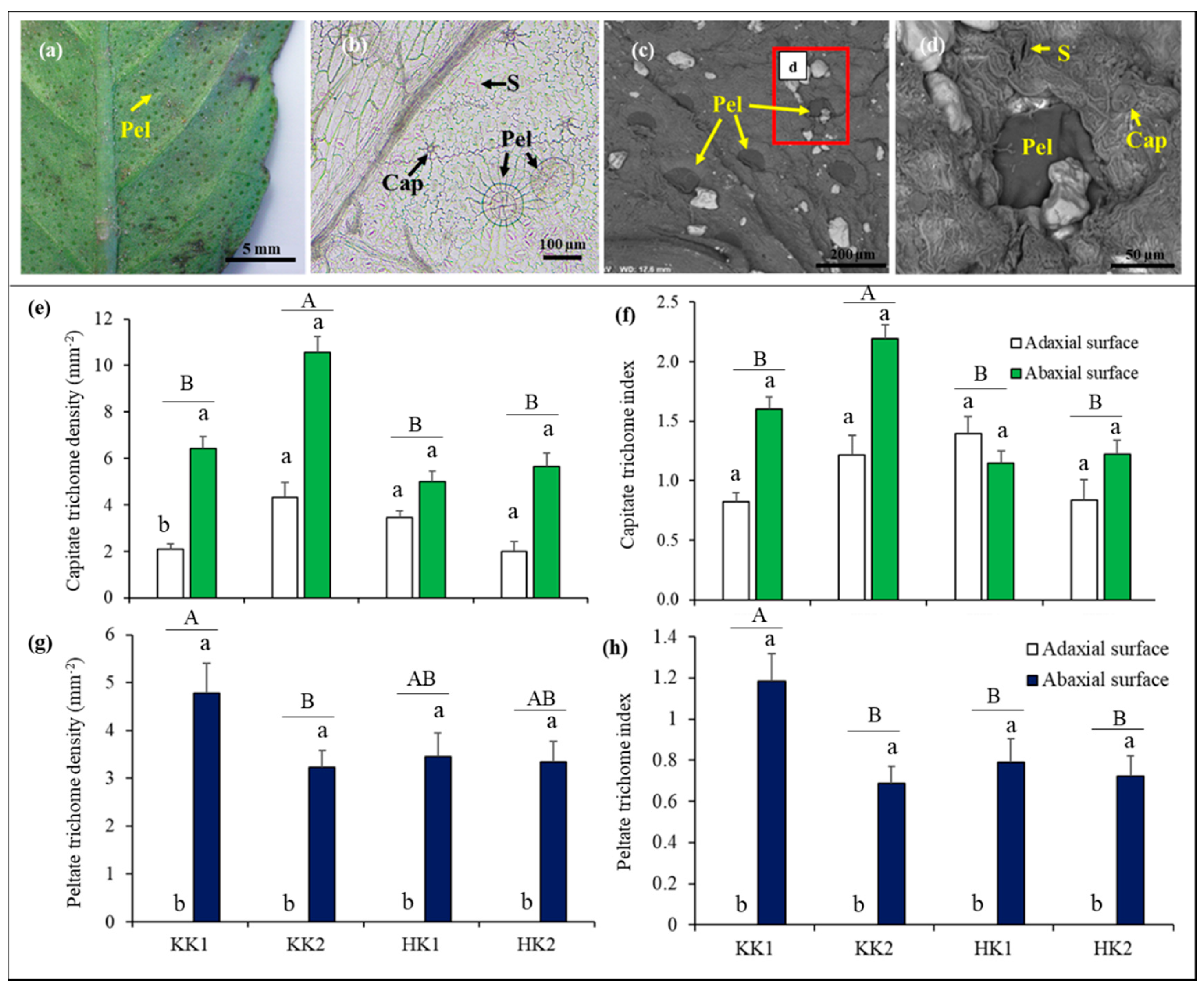

2.8. Morphological Characterization and Density Analysis of Glandular Trichomes

2.9. VOCs Extraction and Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties

3.2. Plant Growth, Photosynthetic Pigments, and Compatible Solutes

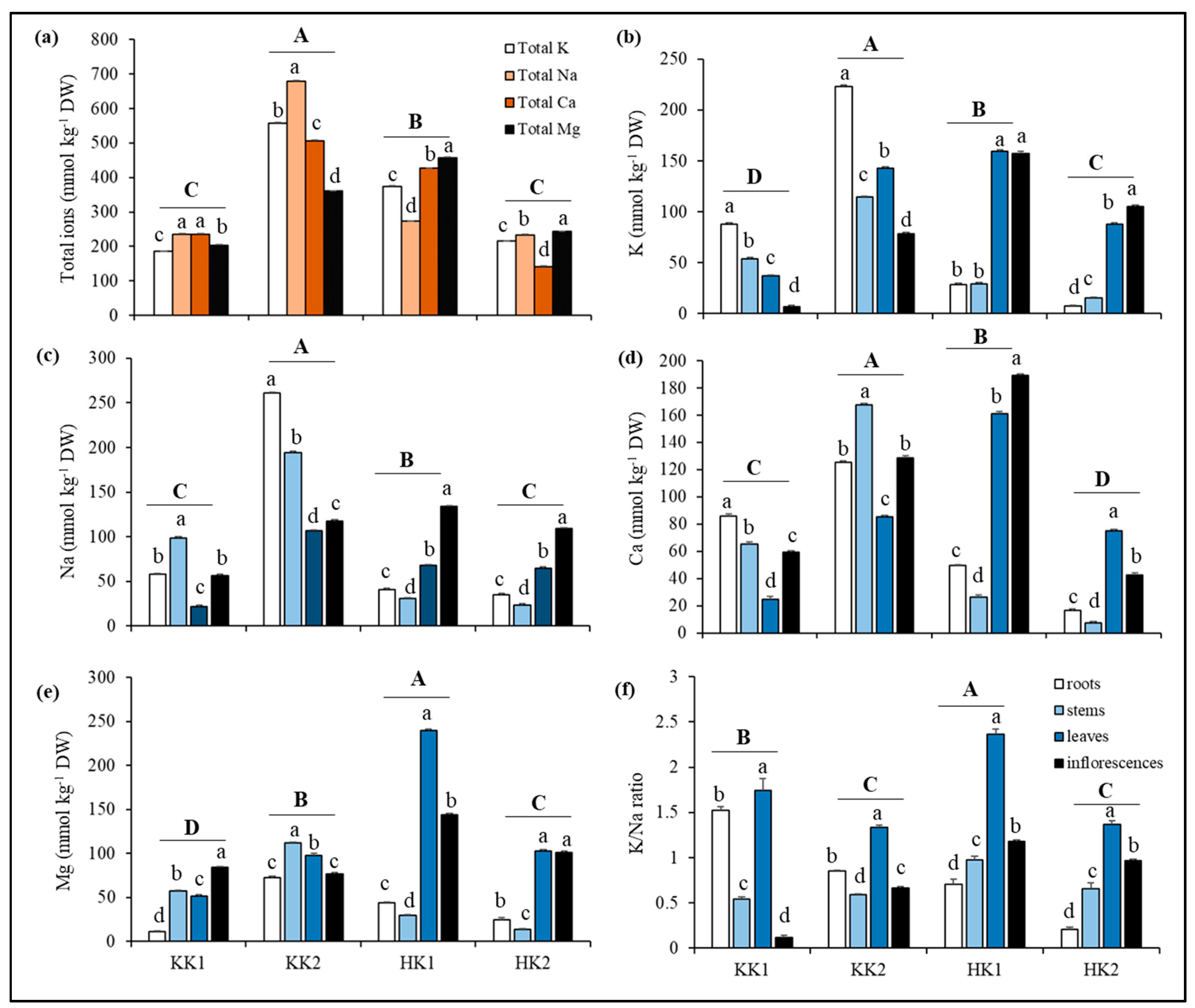

3.3. Salt Ion Accumulation in Plants

3.4. Glandular Trichome Density

3.5. Leaf VOC Analysis

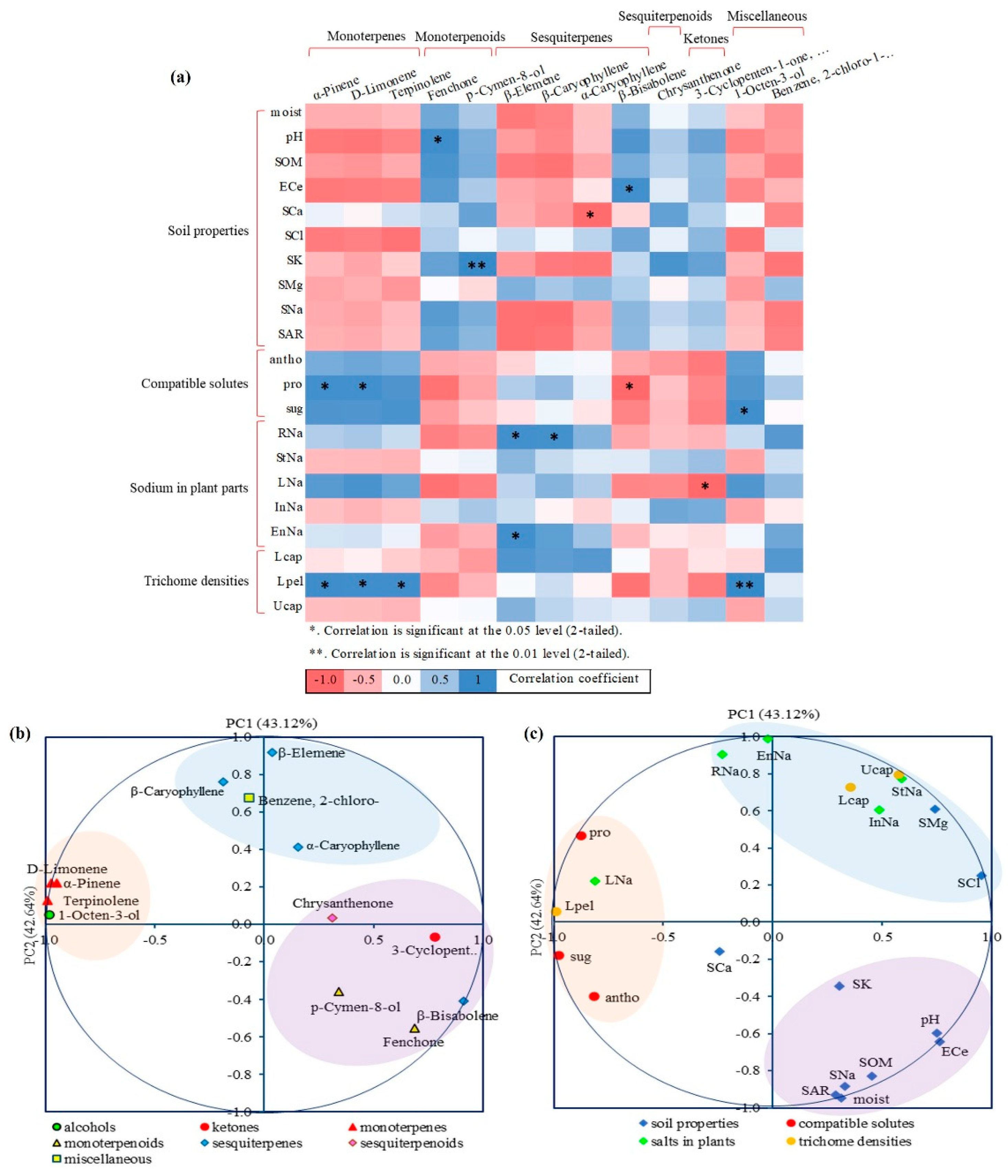

3.6. Correlation and PCA of Plant-Soil Interactions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECe | Electrical conductivity of saturated soil extract |

| HK | Hua Na Kham |

| KK | Khlong Kham |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SAR | Sodium adsorption ratio |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| SOS | Salt Overly Sensitive |

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

References

- Chrysargyris, A.; Tzionis, A.; Xylia, P.; Tzortzakis, N. Effects of salinity on tagetes growth, physiology, and shelf life of edible flowers stored in passive modified atmosphere packaging or treated with ethanol. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrão, S.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Tester, M. Evaluating physiological responses of plants to salinity stress. Ann Bot 2017, 119, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Li, M.; Noor, J.; Tariq, A.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L. Effects of salinity on photosynthetic traits, ion homeostasis and nitrogen metabolism in wild and cultivated soybean. PeerJ 2019, 7, e8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midzi, J.; Jeffery, D.W.; Baumann, U.; Rogiers, S.; Tyerman, S.D.; Pagay, V. Stress-induced volatile emissions and signaling in inter-plant communication. Plants 2022, 11, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari, M.; Ghasemi-Soloklui, A.A.; Kordrostami, M.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H. Deciphering the response of medicinal plants to abiotic stressors: A focus on drought and salinity. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.N.; Thang, T.D.; Thai, T.H.; Ogunwande, I.A. Chemical constituents of leaf essential oils of four Scrophulariaceae species grown in Vietnam. J Essent Oil Res 2015, 27, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, Q.K.; Lu, W.J.; Chen, J.Y.; Tan, X. GC-MS analysis of the chemical constituent of volatile oil from Zhuang drug Adenosma indianum (Lour.) Merr. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2011, 31, 544–546. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Qi, J.; Zhuang, H.; Gou, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. A review of the aromatic genus Adenosma: Geographical distribution, traditional uses, phytochemistry and biological activities. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 275, 114075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Huai-en, W.; Zhi-ying, W.; Yan-fen, X.; Xiao-ling, Y. Chemical constituents and anti-bacterial activity of essential oil from Adenosma indianum. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae 2011, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Meng, C.; Ye, X.; Zeng, Z. Analysis of volatile components of Adenosma indianum (Lour.) Merr. by steam distillation and headspace solid-phase microextraction. J Chem 2012, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.R.; Parks, R.J. Curcumin as an antiviral agent. Viruses 2020, 12, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, N.; Kumari, A.; Raina, N.; Zakir, F.; Gupta, M. Prospects of essential oil loaded nanosystems for skincare. Phytomed. Plus 2022, 2, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laojinda, W.; Khanema, P. Saline soil adaptations of Kratai Cham (Adenosma indianum (Lour.) Merr.): A comprehensive study on life cycle, leaf epidermis, and FTIR analysis of essential oils. Food Agric Sci and Technol 2024, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Land Development Department. Handbook of soil chemical analysis; Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives: Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Land Development Department. Handbook of soil physical analysis; Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives: Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, H.T.; Kahler, H.L. Effect of ions on Mohr method for chloride determination. Ind Eng Chem Anal Ed 1938, 10, 628–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.A. Plants. In Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 15th ed.; Helrich, K., Ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Virginia, USA, 1990; 1, pp. 42.

- Costache, M.A.; Campeanu, G.; Neata, G. Studies concerning the extraction of chlorophyll and total carotenoids from vegetables. Rom Biotechnol Lett 2012, 17, 7702–7708. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J AOAC Int 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilcher, D.L. Approaches to the identification of angiosperm leaf remains. Bot Rev 1974, 40, 1–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonks, A.J.; Roberts, J.M.; Midthassel, A.; Pope, T. Exploiting volatile organic compounds in crop protection: A systematic review of 1-octen-3-ol and 3-octanone. Ann Appl Biol 2023, 183, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lan, Z.; Liang, Y. Analysis of volatile chemical components of Radix Paeoniae Rubra by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and chemometric resolution. J Cent South Univ of Technol 2007, 14, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, M.M.; Zadsirjan, V.; Hamidi, H.; Tabar Amiri, P.H. Total synthesis of natural products containing benzofuran rings. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 24470–24521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatana, K.; Gupta, A. An update on natural occurrence and biological activity of benzofurans. Act Scie Medic Sci 2020, 4, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jishma, P.; Hussain, N.; Chellappan, R.; Rajendran, R.; Mathew, J.; Radhakrishnan, E.K. Strain-specific variation in plant growth promoting volatile organic compounds production by five different Pseudomonas spp. as confirmed by response of Vigna radiata seedlings. J Appl Microbiol 2017, 123, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalstabakken, K.A.; Harned, A.M. Asymmetric transformations of achiral 2,5-cyclohexadienones. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 9571–9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bina, F.; Soleymani, S.; Toliat, T.; Hajimahmoodi, M.; Tabarrai, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Rahimi, R. Plant-derived medicines for treatment of endometriosis: A comprehensive review of molecular mechanisms. Pharmacol Res 2019, 139, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula-Freire, L.I.G.; Andersen, M.L.; Gama, V.S.; Molska, G.R.; Carlini, E.L.A. The oral administration of trans-caryophyllene attenuates acute and chronic pain in mice. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebet, J.J.; Ehiri, J.E.; McClelland, D.J.; Taren, D.; Hakim, I.A. Effect of d-limonene and its derivatives on breast cancer in human trials: A scoping review and narrative synthesis. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-S.; Shi, L.-L.; Guo, K.; Luo, S.-H.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-G.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.-H. A new sesquiterpene synthase catalyzing the formation of (R)-β-bisabolene from medicinal plant Colquhounia coccinea var. mollis and its anti-adipogenic and antibacterial activities. Phytochem 2023, 211, 113681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi Riseh, R.; Ebrahimi-Zarandi, M.; Tamanadar, E.; Moradi Pour, M.; Thakur, V.K. Salinity stress: Toward sustainable plant strategies and using plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria encapsulation for reducing it. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomescu, D.; Şumălan, R.; Copolovici, L.; Copolovici, D. The influence of soil salinity on volatile organic compounds emission and photosynthetic parameters of Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties. Open Life Sci 2017, 12, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Alagoz, S.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Ghorbanpour, M. Proline and soluble carbohydrates biosynthesis and their roles in plants under abiotic stresses. In Plant Stress Mitigators; Ghorbanpour, M., Shahid, M.A. Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; pp 169–185. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ni, R.; Yang, S.; Pu, Y.; Qian, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y. Functional characterization of the Stipa purpurea P5CS gene under drought stress conditions. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Punetha, A.; Chauhan, A.; Suryavanshi, P.; Padalia, R.C.; Kholia, S.; Singh, S. Growth, oil and physiological parameters of three mint species grown under saline stress levels. Physiol Mol Biol Plants 2023, 29, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.K.; Sadhukhan, S. Imperative role of trehalose metabolism and trehalose-6-phosphate signaling on salt stress responses in plants. Physiol Plant 2022, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketehouli, T.; Idrice Carther, K.F.; Noman, M.; Wang, F.-W.; Li, X.-W.; Li, H.-Y. Adaptation of plants to salt stress: Characterization of Na+ and K+ transporters and role of CBL gene family in regulating salt stress response. Agronomy 2019, 9, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, J.-K. A calcium sensor homolog required for plant salt tolerance. Science 1998, 280, 1943–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil properties | KK1 | KK2 | HK1 | HK2 |

| Moisture (%) | 7.62 ± 0.15C1 | 6.54 ± 0.16D | 11.47 ± 0.02B | 18.96 ± 0.61A |

| pH | 6.66 ± 0.01D | 6.76 ± 0.06C | 6.83 ± 0.05B | 6.88 ± 0.07A |

| SOM (%) | 1.58 ± 0.11C | 1.64 ± 0.29C | 2.14 ± 0.22B | 2.40 ± 0.40A |

| ECe (dS m-1) | 0.51 ± 0.01D | 1.06 ± 0.03C | 1.13 ± 0.05B | 1.71 ± 0.04A |

| K (mmol kg-1) | 1.34 ± 0.01D | 1.94 ± 0.01C | 13.96 ± 0.18A | 6.97 ± 0.17B |

| Na (mmol kg-1) | 15.79 ± 0.03C | 10.39 ± 0.52D | 51.84 ± 0.02B | 71.47 ± 0.26A |

| Ca (mmol kg-1) | 13.41 ± 0.16B | 8.98 ± 0.22D | 19.68 ± 0.24A | 11.66 ± 0.28C |

| Mg (mmol kg-1) | 10.49 ± 0.21D | 31.21 ± 0.11A | 16.13 ± 0.21B | 15.56 ± 0.07C |

| Cl (mmol kg-1) | 10.47 ± 0.99D | 29.87 ± 1.42A | 20.33 ± 0.42C | 22.47 ± 0.70B |

| SAR | 4.57 ± 0.02C | 2.32 ± 0.11D | 12.25 ± 0.01B | 19.37 ± 0.16A |

| Plant traits | KK1 | KK2 | HK1 | HK2 |

| Plant growth | ||||

| Plant biomass (%) | 27.90 ± 2.43B1 | 26.83 ± 0.43B | 34.11 ± 1.50A | 30.18 ± 7.10B |

| Stem height (cm) | 17.50 ± 2.52A | 16.37 ± 2.90A | 20.10 ± 1.87A | 19.23 ± 0.95A |

| Leaf area (cm-2) | 8.67 ± 1.53B | 11.67 ± 1.15A | 8.67 ± 2.08B | 7.33 ± 1.53B |

| Photosynthetic pigments (µg g-1) | ||||

| Chlorophyll a | 173.83 ± 8.48C | 171.53 ± 3.31C | 189.09 ± 1.76B | 332.96 ± 5.01A |

| Chlorophyll b | 120.94 ± 5.50B | 129.37 ± 6.43B | 94.49 ± 0.99C | 187.42 ± 1.38A |

| Total chlorophyll | 294.77 ± 13.94B | 300.90 ± 9.73B | 283.57 ± 2.73B | 520.38 ± 6.23A |

| β-carotene | 177.49 ± 8.87A | 133.05 ± 0.96B | 103.62 ± 0.73C | 186.60 ± 2.23A |

| Leaf compatible solutes (µg g-1) | ||||

| Anthocyanins | 250.48 ± 6.68A | 60.68 ± 11.12C | 63.46 ± 4.42C | 166.99 ± 14.56B |

| Proline | 147.25 ± 4.20A | 112.22 ± 18.30B | 107.77 ± 4.42B | 91.64 ± 15.50C |

| Total sugar | 28.28 ± 0.02A | 11.16 ± 0.01C | 15.32 ± 0.05B | 16.50 ± 0.01B |

| No. | Chemical class & Compounds | KK1 | KK2 | HK1 | HK2 | |||||

| RT (min) | Area sum (%) | RT (min) | Area sum (%) | RT (min) | Area sum (%) | RT (min) | Area sum (%) | |||

| Monoterpenes | ||||||||||

| 1 | α-pinene | 7.263 | 2.65 | 7.163 | 0.71 | 7.262 | 0.95 | 7.163 | 0.47 | |

| 2 | sabinene | 8.780 | 0.09 | 8.676 | 0.03 | 8.777 | 0.04 | 8.674 | 0.03 | |

| 3 | β-pinene | 9.479 | 0.21 | 9.377 | 0.07 | 9.479 | 0.05 | 9.380 | 0.05 | |

| 4 | (+)-4-carene | 9.757 | 0.08 | 9.651 | 0.03 | 9.754 | 0.03 | 9.650 | 0.02 | |

| 5 | 3-carene | 10.130 | 0.31 | 10.023 | 0.12 | 10.131 | 0.11 | 10.023 | 0.08 | |

| 6 | 2-carene | 10.409 | 0.17 | 10.307 | 0.05 | 10.412 | 0.04 | 10.309 | 0.03 | |

| 7 | m-cymene | 10.742 | 0.21 | 10.648 | 0.11 | 10.741 | 0.12 | 10.647 | 0.10 | |

| 8 | D-limonene | 10.951 | 21.44 | 10.849 | 9.11 | 10.934 | 8.45 | 10.846 | 7.27 | |

| 9 | β-ocimene | 11.850 | 0.66 | 11.744 | 0.18 | 11.851 | 0.11 | 11.746 | 0.11 | |

| 10 | γ-terpinene | 12.211 | 0.06 | 12.104 | 0.02 | 12.209 | 0.02 | 12.104 | 0.01 | |

| 11 | terpinolene | 13.483 | 3.33 | ND | ND | 13.484 | 0.97 | ND | ND | |

| 12 | verbenone | 18.759 | 0.21 | 18.735 | 0.21 | 18.756 | 0.23 | 18.740 | 0.09 | |

| 13 | carvone | 20.371 | 0.09 | 20.297 | 0.12 | 20.360 | 0.17 | 20.304 | 0.14 | |

| 14 | zingiberene | 27.445 | 0.14 | 27.360 | 0.22 | 27.457 | 0.19 | 27.360 | 0.23 | |

| Monoterpenoids | ||||||||||

| 1 | cis-β-terpineol | 12.555 | 0.05 | 12.511 | 0.03 | 12.553 | 0.04 | 12.522 | 0.02 | |

| 2 | cis-linalool oxide | 12.815 | 0.03 | 12.757 | 0.02 | 12.811 | 0.01 | 12.760 | 0.01 | |

| 3 | fenchone | 13.381 | 2.54 | 13.323 | 4.28 | 13.404 | 6.53 | 13.348 | 6.63 | |

| 4 | β-linalool | 14.104 | 0.27 | 14.054 | 0.21 | 14.102 | 0.19 | 14.054 | 0.16 | |

| 5 | fenchol | 14.550 | 0.07 | 14.506 | 0.11 | 14.550 | 0.26 | 14.509 | 0.20 | |

| 6 | trans-p-mentha-2,8-dienol | 14.901 | 0.06 | 14.856 | 0.05 | 14.894 | 0.14 | 14.858 | 0.09 | |

| 7 | α-campholenal | 15.112 | 0.02 | ND | ND | 15.109 | 0.04 | ND | ND | |

| 8 | cis-p-mentha-2,8-dien-1-ol | 15.524 | 0.08 | ND | ND | 15.541 | 0.10 | ND | ND | |

| 9 | endo-borneol | 16.854 | 0.07 | 16.823 | 0.06 | 16.855 | 0.06 | 16.826 | 0.05 | |

| 10 | citral | 17.405 | 0.73 | 17.360 | 0.47 | 17.411 | 1.10 | 17.368 | 0.75 | |

| 11 | p-cymen-8-ol | 17.830 | 1.14 | 17.832 | 1.19 | 17.847 | 1.78 | 17.845 | 1.45 | |

| 12 | α-terpineol | 18.038 | 0.21 | 18.013 | 0.20 | 18.043 | 0.20 | 18.021 | 0.13 | |

| Sesquiterpenes | ||||||||||

| 1 | β-elemene | 26.796 | 1.27 | 26.744 | 1.66 | 26.819 | 0.99 | 26.743 | 0.81 | |

| 2 | β-caryophyllene | 27.814 | 1.85 | 27.743 | 2.11 | 27.823 | 1.01 | 27.734 | 1.07 | |

| 3 | α-caryophyllene | 29.208 | 6.17 | 29.168 | 7.45 | 29.219 | 4.32 | 29.164 | 5.94 | |

| 4 | cis-β-farnesene | 29.580 | 0.13 | 29.483 | 0.25 | 29.580 | 0.22 | 29.483 | 0.28 | |

| 5 | β-selinene | 30.505 | 0.41 | 30.426 | 0.68 | 30.513 | 0.38 | 30.434 | 0.34 | |

| 6 | α-selinene | 30.879 | 0.32 | 30.798 | 0.51 | 30.885 | 0.26 | 30.797 | 0.24 | |

| 7 | β-bisabolene | 31.616 | 12.85 | 31.629 | 21.08 | 31.677 | 19.67 | 31.657 | 24.50 | |

| 8 | β-sesquiphellandrene | 32.141 | 0.64 | 32.078 | 1.08 | 32.153 | 0.87 | 32.085 | 1.11 | |

| 9 | humulene-1,2-epoxide | 35.217 | 0.53 | 35.178 | 1.11 | 35.223 | 0.90 | 35.190 | 1.69 | |

| Sesquiterpenoids | ||||||||||

| 1 | chrysanthenone | 24.542 | 1.34 | 24.535 | 1.44 | 24.553 | 1.84 | 24.534 | 1.43 | |

| 2 | cinerolone | 27.090 | 0.40 | 27.050 | 0.66 | 27.103 | 0.43 | 27.053 | 0.56 | |

| 3 | caryophyllene oxide | 34.219 | 0.18 | 34.173 | 0.30 | 34.222 | 0.25 | 34.172 | 0.32 | |

| Ketones | ||||||||||

| 1 | p-mentha-1,8-dien-3-one, (+)- | 21.574 | 0.08 | 21.532 | 0.12 | 21.576 | 0.13 | 21.534 | 0.11 | |

| 2 | 3-cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)- | 25.842 | 34.98 | 25.969 | 40.63 | 25.966 | 44.04 | 25.991 | 40.66 | |

| Miscellaneous and Diverse Compounds | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1-octen-3-ol | Alcohols | 9.061 | 1.00 | 9.014 | 0.34 | 9.063 | 0.40 | 9.017 | 0.39 |

| 2 | dodecane | Alkane | 18.623 | 0.23 | ND | ND | 18.623 | 0.15 | ND | ND |

| 3 | benzofuran, 4,7-dimethyl- | Ether | 18.975 | 0.07 | 18.886 | 0.08 | 18.972 | 0.10 | 18.882 | 0.10 |

| 4 | 2-allyl-4-methylphenol | Phenols | 19.236 | 0.13 | 19.201 | 0.32 | 19.239 | 0.19 | 19.208 | 0.30 |

| 5 | 1,4-benzenediol, 2,5-dimethyl- | Phenols | 22.298 | 0.53 | 22.244 | 0.45 | 22.308 | 0.58 | 22.247 | 0.50 |

| 6 | 2-cyclohexen-1-one, 3,6-dimethyl-6-(1-methylethyl)- | Cycloalkanes | 22.721 | 0.50 | 22.692 | 0.40 | 22.729 | 0.45 | 22.693 | 0.45 |

| 7 | benzene, 2-chloro-1-ethyl-5-methoxy-3-methyl- | Aromatic | 33.879 | 1.47 | 33.881 | 1.73 | 33.887 | 0.89 | 33.864 | 1.08 |

| Total identified classes | ||||||||||

| Monoterpenes | 29.65 | 10.98 | 11.48 | 8.63 | ||||||

| Monoterpenoids | 5.27 | 6.62 | 10.45 | 9.49 | ||||||

| Sesquiterpenes | 23.64 | 34.82 | 27.72 | 34.29 | ||||||

| Sesquiterpenoids | 2.27 | 3.21 | 3.17 | 3.68 | ||||||

| Ketones | 35.24 | 41.05 | 44.42 | 41.09 | ||||||

| Miscellaneous | 3.93 | 3.32 | 2.76 | 2.82 | ||||||

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).