1. Introduction

High-energy materials are widely used for mining, construction, military, and other purposes. Thus, exploitation of them is constantly growing each year along with requirements for effectiveness and safety. Currently, there are several directions in the modeling and synthesis to produce materials with favorable detonation performances and high resistance to any stimuli. One of these directions relies on increasing the density of potential hazards. Generally, it is achieved by the inclusion of nitrogen-rich backbones such as triazole, furazan, etc. Currently performed investigations reveal that the introduction of the fluorine-containing group to cycle nitramines could increase their densities as well as detonation performances with remaining good thermal stability [

1,

2]. These results are supported by investigations of Wang et al., which exhibited detonation velocity and heat of explosion of 3-Bromo-5-fluoro-2,4,6-trinitroanisole are higher, and impact and friction sensitivity are lower than those of TNT [

3]. The presence of the pentafluorosulfanyl group markedly increases the densities and can provide energetic salts with improved properties [

4]. Nevertheless, the synthesis of SF

5-containing high-energy materials is a challenge that needs much effort to overcome [

5]. Despite that some aromatic derivatives, containing SF

5 functional group, have already found application in molecular structures of pesticides, optoelectronic materials, and medicinal drugs, however, only a small number of S-containing organic high-energy materials have been mentioned as high-energy ones. A few, very limited, studies are currently known today, which discussed the computational and experimental energetic properties of these potentially interesting and perspective compounds.

Notably, along with increasing the detonation performances, the thermal and chemical stability, as well as resistance to shock stimuli must coincide or, in the beneficial cases, be higher than that of the exploited high-energy materials. Jagadish et al. mentioned the incorporation of sulfur into high-energy materials as a way to improve their thermostability and, in some cases, to decrease their sensitivity to impact, friction, and electrostatic discharge [

6]. The newly synthesized C–C bonded 1,3,4-thiadiazole with pyrazine, incorporating a nitrimino explosophoric moiety, exhibits moderate to high thermal decomposition temperatures, high positive heats of formation, and good densities with strong detonation performances [

7].

A study, recently performed by us, reveals that the incorporation of -CF

3 and -OCF

3 fragments could increase the energetic properties of nitroaromatics, along with stability and resistance to shock stimuli. Compounds, whose assignation codes are CF3N2, OCF3N2, C2F6N2, 1CF2N2/O2CF2N2, and 2CF4N2/O2C2F4N2, were suggested for practical usage because these compounds possess greater stability compared to tetryl and better explosive properties than TNT [

8]. The view of these compounds and their full chemical name are given in

Appendix A. So the question arises if the detonation properties of the nitro-compounds are better when -SF

5 is incorporated along with the above-mentioned fluorine-containing groups. On the other hand, it remains unclear which fluorine-, fluorine-sulfur-containing groups or their combination leads to achieving the greatest improvement. It means not only enhancing detonation properties but also significantly increasing the chemical and thermal stability of the material as well as its impact resistance. Therefore this study aims to predict whether replacing the -CF₃ or -OCF

3 groups in aromatic nitrocompounds with -SF₅ will enhance their energetic properties. It could help to estimate the significance of this replacement and foresee the new direction in the design of advanced high-energy materials. Previously only early works of Sitzmann et al. were dedicated to pentafuorosulfanyl derivatives, where their physicochemical and energetic properties have been researched. However, this work covered only nitro aliphatic compounds, while nitroaromatic compounds were scarcely studied [

9].

2. Materials and Methods

As outlined earlier, the study aimed to demonstrate the influence of the -SF

5 group on the stability and energetic properties of fluorine-containing compounds. The methodology employed in this research aligns with that presented in our recently published work [

8]. Multiple conformers of each molecule under investigation were designed to ensure reliable results. The conformers differ in the positions of substituents relative to the core structure. It is important to note that, in certain cases, steric effects allow only one positional arrangement.

Becke’s three-parameter hybrid functional approach with non-local correlation, as defined by Lee, Yang, and Parr (B3LYP), was utilized in conjunction with the cc-pVTZ basis set implemented in the GAUSSIAN software package [

10,

11,

12]. This approach effectively describes various molecules' geometric and electronic structures and their derivatives [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. To identify equilibrium configurations, Berny optimization was performed without applying any symmetry constraints, allowing the optimization of bond lengths, angles, and dihedral angles. A vibrational frequency analysis confirmed that energy minima were achieved, ensuring the structure of the most stable conformer was identified.

Initially, the calculated total energies of the conformers were compared, and the conformers with the lowest total energy were selected for further analysis. To assess and compare the thermal stability of compounds with varying chemical compositions, cohesion (BEA) was calculated. This parameter, which indicates the energy required to separate an atom from a system of particles, was determined using the following formula:

where

E is the total energy of the molecule under study,

Ei is the total energy of the atoms consisting of this molecule, and

N is the number of atoms. A larger value of BEA, the normalized energy differences, shows a higher thermal stability. To evaluate the stability related to the chemical properties and aging of the compounds investigated we calculated the HOMO–LUMO gap, chemical hardness, and electronegativity. It is known that compounds with a larger HOMO–LUMO gap and chemical hardness are more resistant to undergoing chemical reactions or to being transformed by an external perturbation, such as an applied electric field. On the other hand, a high electronegativity denotes a high tendency of the molecule to attract an electron that leads to ionization and could speed up the degradation [

24,

25].

It is known, that the density of the compounds is the main factor in increasing the detonation pressure and velocity of the compounds. Our study begins with the evaluation of the density of the generic compounds: C2F6N3, CF3N2, CF3N3, C3F9N3, O2C2F6N3, O3C3F9N3 The density of the compounds was predicted by three approaches:

It was done to find a more reliable approach for the density evaluation of the compounds consisting of -SF

5 substitutes. ACD/ChemSketch reliably predicts the density of known fluorine-containing compounds. For example, the experimentally obtained density of CF3N3 is 1.716 - 1.816 g/cm

3, while that estimated by ACD/ChemSketch is equal to 1.77 g/m

3 [

24]. Based on the analysis of the calculated densities and the outlined values of the experimental measurements, the density of the -SF

5-containing compounds was calculated using the above Politizer equation. The proof of the above decision is given in the section Results.

The semi-empirical equations Kamlet and Jacobs developed focus on the C

aH

bN

cO

d compounds. They are not suitable for evaluating the parameters of the derivatives consisting of fluorine and sulfur. The equations suggested by Keshavarz et al. are dedicated to the C

aH

bN

cO

dF

e compounds [

27,

28]. The approaches implemented in Cheetah, Thermo, or EXPLO5 rely on thermodynamic databases, which may have limited or incomplete data for certain fluorine- and sulfur-containing compounds, particularly those that are newly designed and not synthesized. So, we used several Machine learning models to evaluate the detonation velocity and pressure. The data for the training were collected from all available papers [

28,

29,

30]. Considering that the SF

5-group is used to increase the density of these molecules and that, as a consequence, leads to better detonation performance, we obtained a dependence of the detonation pressure and velocity on the density. Another main reason for focusing solely on the density of the compound is the variability of other parameters provided alongside detonation pressure and velocity. To ensure a comprehensive dataset for training, we aim to minimize incompleteness caused by differences in the parameters presented. Notably, the density of the compounds depends on their chemical and geometrical structures and it is, therefore, one of the factors influencing the products of detonation, which directly determines the detonation pressure and velocity [

31]. Considering our aim to show how the stability and explosive properties of the fluorine-containing compounds could be changed due to the replacement -CF

3 group with -SF

5, and advanced Machine learning, we hope that the above dependence is sufficient to find the main general tendency for the improving properties of high energy materials.

The dataset for Machine learning consists of sulfur, and sulfur-fluorine compounds to obtain general equations for evaluating and seeking the progress of the detonation properties rising due to the implementation of -SF5 groups. It satisfies our aim to predict the influence of the above sulfur group on the energetic properties of the fluorine-containing compounds, i.e. when -CF3 groups are replaced by -SF5. As the dataset for Machine Learning was relatively small, we employed Linear Regression, Polynomial Regression, Random Forest Regression, and Bayesian Ridge Regression, which are known to perform well in predicting numerical values. We used 80% of the generated dataset for training, reserving the remaining 20% for testing. To identify the most precise model, the models' performances were evaluated using metrics such as Accuracy, Mean Squared Error, and the Coefficient of Determination (R2). Additionally, we find that the detonation pressure mostly depends on the density of the compounds, while detonation velocity is pressure-dependent. The metrics for the accuracy of the applied Machine learning methods were the best in the case of the Polynomial regressions. So the resulting equations of this approach were applied to calculate the detonation pressure and velocity of newly designed fluorine- and sulfur-containing compounds. Each predicted value was validated against experimentally observed trends and anticipated limitations to ensure reliability.

3. Results

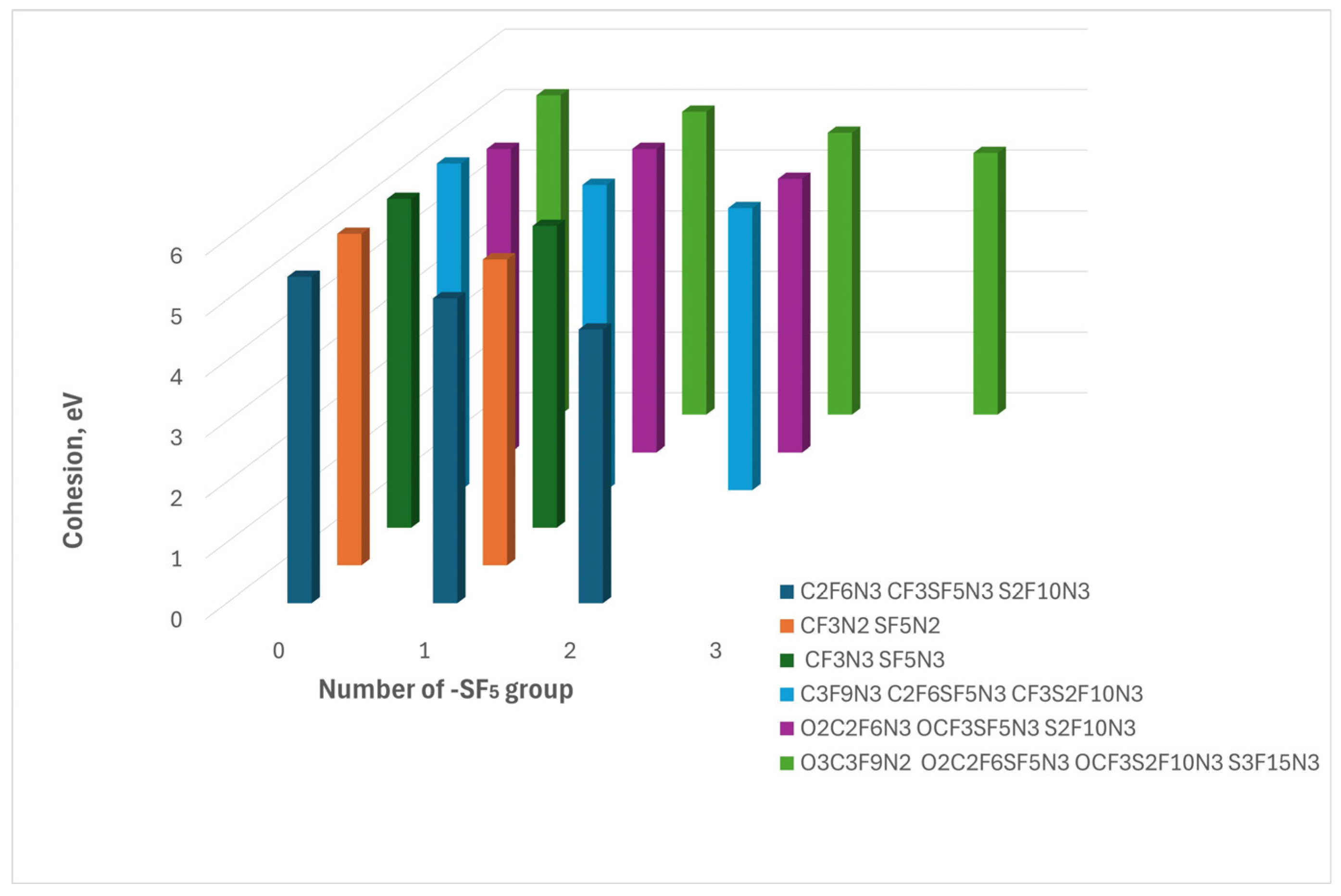

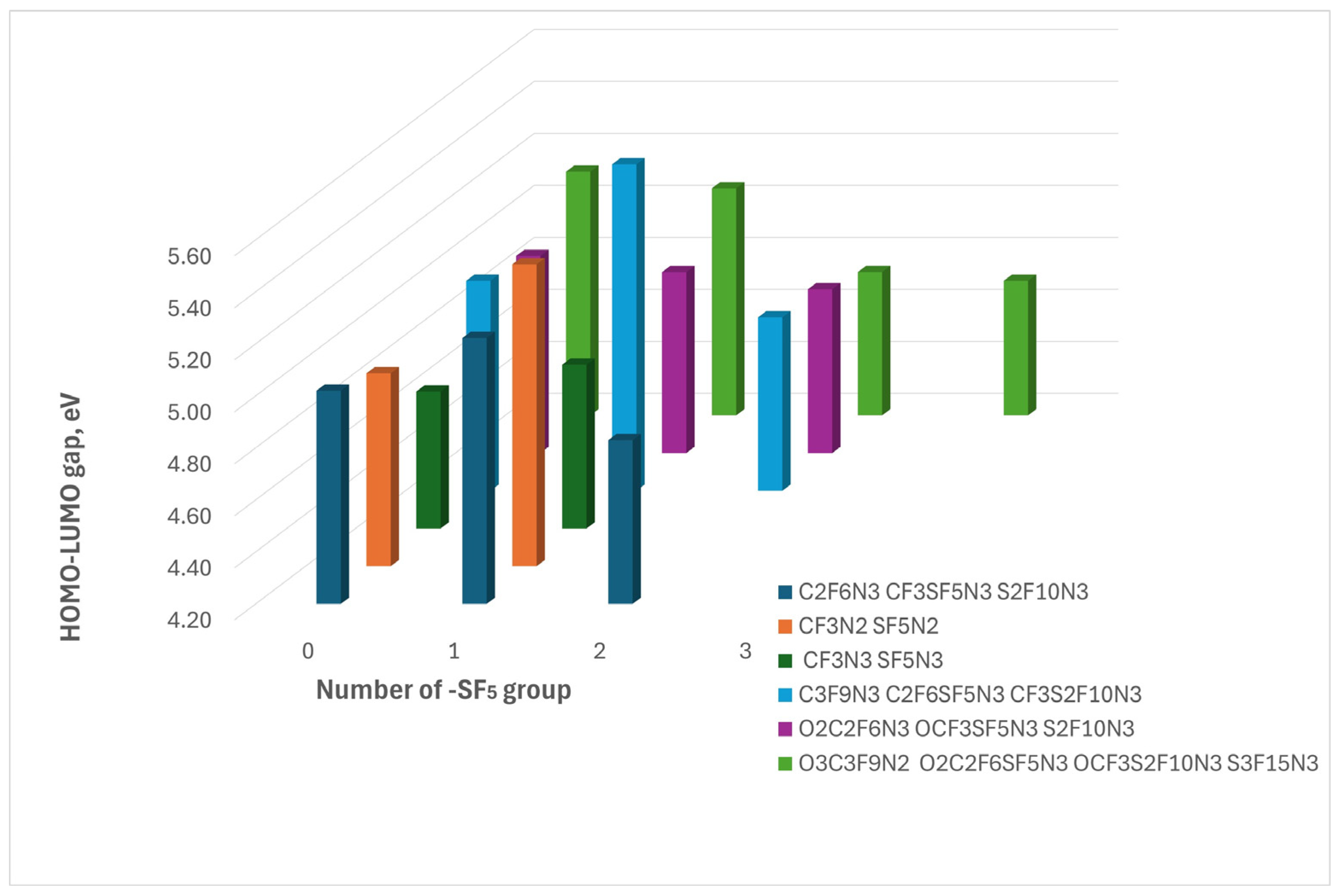

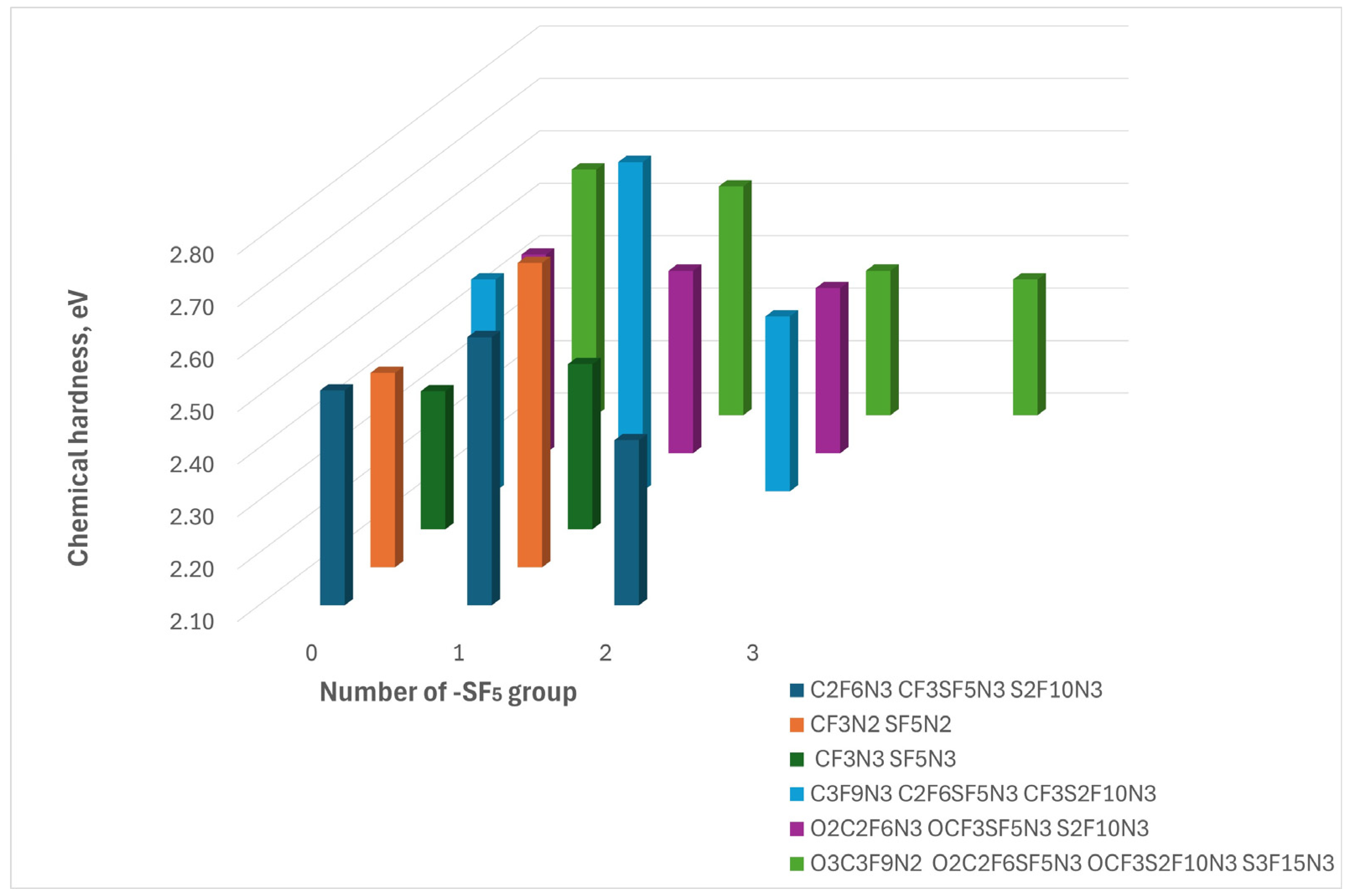

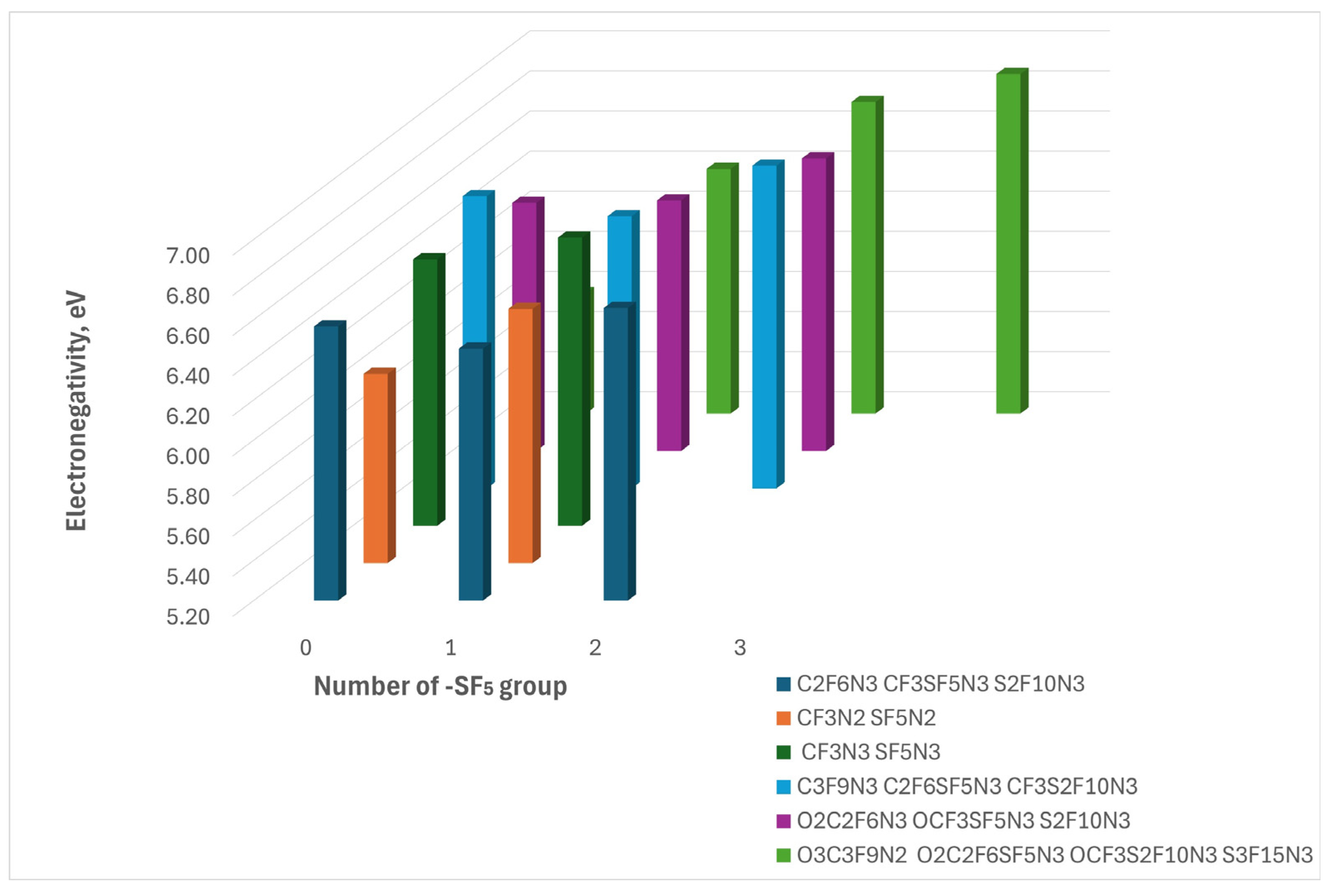

The sketch of the investigated compounds, their chemical composition, full chemical name, and assignation code are presented in Appendixes A and B. It is necessary to mention that the hardness index of the compounds under study is higher than 0.9 which indicates their higher thermal and chemical stability. To be more specific and show how -the SF

5 group influences the thermal and chemical stability of the selected fluorine-containing compounds, we calculate the cohesion, HOMO-LUMO gap, chemical hardness, and electronegativity. The dependence of these parameters on the number of -SF

5 group is presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 and

Table 1.

The study of the energetic properties was started by evaluating the approaches used for the density calculations. The values of the densities of the fluorine-containing compounds obtained by the approach implemented in ACD/ChemSketch program, by using Politizer et al. suggested equation, and followed by our results of the calculations are presented in

Table 2.

It is observed that the values obtained using the Politzer et al. equation are generally higher than those calculated using the ACD/ChemSketch program but lower than those derived from calculations performed with the Gaussian program. Moreover, the density of the CF3N3 compound obtained by the equation coincides with the experimentally determined density of 1.82 g/cm³. The calculated densities of other presented compounds also are in the range of representative values [1.6-2.4 g/cm³ ] of the experimentally measured one for fluorine-containing compounds [

32]. The above equation along with the approach implemented in ACD/ChemSketch was used to evaluate the fluorine-sulfur-containing compound's density. The density is presented in

Table 3.

The announced values of SF

5-containing compounds are from 1.30 ( gas state)) to 2.08 g/cm

3, although in some cases ( for example, in concentrated forms), it could approach or exceed 2.40 g/cm

3 and reach 2.86 g/cm

3 [

29,

30,

31]. Referring to the results presented in

Table 3, we may assume that the approach implemented in the ACD/ChemSketch program is dedicated to evaluating the density of the sulfur-fluorine-containing compounds in concentrated forms. On the other hand, the values obtained using Politizer et al. equation represent a more general density of these types of compounds. We used these values of the densities for the evaluation derivatives representing energetic properties to avoid overestimating them considering the potential of the sulfur-fluorine-containing compounds.

As mentioned above, we used several Machine Learning models to find the most accurate for our purpose. The highest accuracy, lowest mean squared error, and a coefficient of determination of 0.70 for evaluating the dependence of detonation pressure on density, and 0.90 for the dependence of detonation velocity on the pressure, were achieved using the polynomial regression model. Thus the model was used to evaluate the detonation velocity and pressure. The obtained values are presented in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

The results of the density variations due to the replacement of fluorine-containing groups by -SF

5 are presented in

Figure 5.

Generally, replacing the -CF

3 group with -SF

5 tends to increase the density of compounds. This observation aligns well with experimentally obtained results [

28]. However, this trend is not observed in the case of CF2N2 and O2CF3SF5N3. It could occur because the molecular volume outweighs the increase in molecular weight because of a trigonal bipyramidal geometry of the -SF

5 groups, which is bulkier than the relatively compact tetrahedral geometry of -CF

3. Therefore, while the addition of the heavy -SF

5 group can increase the density of compounds, this effect is not consistently observed when -CF

3 is replaced by -SF

5. Despite this finding, the density of two compounds (SF5N2 and S2F10N3) is lower than that of TNT, while that of CF3SF5N3, C2F6SF5N3, CF3S2F10N3, O2C2F6SF5N3, S3F15N3 is higher than the density of HMX - a powerful and relatively insensitive nitroamine.

As it was mentioned above, the hardness index of the compounds under study indicated their high stability. However, the analysis of the BEA exhibits that implementation of the -SF

5 leads to a decrease in their thermal stability (

Figure 1,

Table 1). Indeed, the S-F and C-F bonds are one of the strongest bonds rendering these -SF

5 and -CF

3 groups highly resistant to thermal decomposition and chemical reactions. However, the bond energy 272 kJ/mol of the S-C bonds is lower than 347 kJ/mol of C-C [

33,

34]. In some cases, the 360 kJ/ mol of the C-O bond is replaced by lower energy C-S. It could be the main reason for the decrease in thermal stability caused by the replacement of -CF

3 to -SF

5. Based on the findings we may predict that S-C bonds should be decomposed first during an explosion to form -CF

3 and -SF

5 and then, if the realized energy is enough, these groups should decompose. Thus, after an explosion of CaHbFcNdOeSf compounds in rich by -SF

5 group along with CO, CO

2, COS, H

2S, HF, H

2O, and N

2 gases the SFn could be present, too [

35].

Referring to the results of the HOMO-LUMO gap dependence on the -SF

5 group number we conclude that some precise number of -SF

5 takes place in the most chemically stable compounds (

Figure 2.

Table 1). Indeed, the HOMO-LUMO gap of the compounds with one -SF

5 group is the largest among the similar ones. More precisely, replacing one -CF

3 group with -SF

5 increases the chemical stability of nitro compounds. However, the addition of a second -SF

5 group significantly decreases stability, while the influence of additional -SF

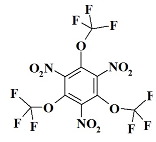

5 groups appears negligible. The exception is O3C3F9N2 which is a highly fluorine-rich compound thus any replacement of -CF

3 with -SF

5 leads to a decrease in chemical stability. Referring to these results, we speculate that increasing the fluorine content in nitro compounds to improve both chemical and thermal stability may be limited by two factors: the number of fluorine atoms in the compound is 9, the implementation of other fluorine-containing groups worsens stability

This tendency is confirmed by the analysis of the chemical hardness: the largest values of the parameter are the compounds possessing one -SF5 group except for the sulfur-fluorine compounds originating from O3C3F9N2. So, the most chemically stable compounds derived from different parent molecules can be ranked based on their resistance to reaction, as follows:

C2F6SF5N3> SF5N2> CF3SF5N3> O3C3F9N2> OCF3SF5N3 > SF5N3

The high electronegativity of the compounds under study is not a surprise because they consist of fluorine atoms. The values of this parameter ranged from 5.18 eV to 6.89 eV indicating a high tendency to attract electrons which could lead to fast aging due to ionization.

It is necessary to highlight SF5N2 and SF5N3, which differ in the number of -NO₂ groups. Previously, we demonstrated that increasing the number of -NO₂ groups in fluorine-containing compounds enhances their energetic properties. This trend is evident in these compounds: the detonation pressure and velocity of SF₅N₂, which contains two nitro groups, are lower than those of SF₅N₃, which possesses three nitro groups.

Typically, the high-energy materials exhibit detonation velocities between 1.01 km/s and 9.89 km/s. The measured detonation velocity of TNT, usually used as a standard is 6.9 km/s. That of RDX and HMX is 8.7 and 9.1 km/s. Hence, the detonation velocity results presented in

Table 4 classify the compounds under study as high-energy materials. Moreover, the detonation velocity of only two compounds, S2F10N3 and SF5N2, is comparable to that of TNT, while the detonation velocity of the remaining compounds is higher. However, these detonation velocities are lower than RDX and HMX. A similar observation can be made when comparing the detonation pressure of TNT (~210 kbar), RDX (338 kbar), and HMX(393 kbar) with the values presented in

Table 4 [

7,

36]. Again, the detonation pressure of S2F10N3 and SF5N2 is similar to that of TNT, while that of others is between TNT and RDX except for CF3S2F10N3. The detonation pressure of this compound is higher than RDX but lower than HMX. Hence, the implementation of -SF

5 groups could lead to improvement in the energetic properties of fluorine-sulfur-containing nitro compounds, but it is not mandatory (Fig.). Notably, the detonation pressure of the nitro compounds consisting of -CF

3 or -OCF

3 mentioned in this paper varies from 189 to 459 kbar [

8]. Their detonation velocity is also higher, altering from 7.01 to 8.78 km/s. Based on these results, we speculate that replacing -CF₃ or --OCF

3 with -SF₅ would not improve the energetic properties of fluorine-containing nitro compounds

That being said, the results depicted in

Figure 6 suggest that replacing -CF₃ with -SF₅ may enhance the energetic properties of fluorine-containing compounds. However, it is not valid for compounds where -CF

3 is incorporated within oxygen. Reducing the number of oxygen atoms results in a decline in the energetic properties of the compounds consisting of -OCF

3 and -SF

5 groups.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to predict the influence of the alternate of the -CF3 or -OCF3 by -SF5 on the stability and detonation performances of the fluorine-containing nitro amines. Notably, all designed and investigated compounds are classified as high-stability and high-energy compounds.

We found that it is not mandatory that -CF3 replacement by heavier -SF5 group leads to increasing the density of the compounds. This is because of the different intensification in volume and molecule weights. Despite that, the density of our proposed advanced materials such as CF3SF5N3, C2F6SF5N3, CF3S2F10N3, O2C2F6SF5N3, S3F15N3 is higher than the density of HMX - a powerful and relatively insensitive nitroamine.

Another undesirable effect is the reduction in thermal stability caused by the inclusion of -SF5 instead -CF3 or-OCF3. Moreover, the comparison of the evaluated parameters such as the HOMO-LUMO gap, the energy of cohesion, and chemical hardness allows us to conclude that the number of fluorine atoms in the nitro compound should not be higher than nine because surpassing this threshold leads to a decrease of the chemical and thermal stability of fluorine-containing nitro compounds. Additionally, we speculate the rapid aging of the compounds under study due to ionization considering the high electronegativity.

Regarding detonation performance, there is no a solid statement on the improvement of the detonation performances due to the replacement fluorine group by pentafluorosulfanyl. The replacement of -OCF₃ with -SF₅ reduces the number of oxygen atoms, leading to a decline in energetic properties in compounds containing both -OCF₃ and -SF₅. In contrast, replacing -CF₃ with -SF₅ produces the opposite effect, improving detonation performance.

Based on our findings and the challenges associated with incorporating the pentafluorosulfanyl group into nitro compounds, we conclude that the practical implementation of compounds containing -SF₅, either alone or in combination with -CF₃ or -OCF₃, is unlikely to be effective or beneficial.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T. and J.S.; methodology, J.T., and J.S; formal analysis, J.T, and J.S.; investigation, J.T. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, J.T. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to access restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The numerical calculations with the GAUSSIAN09 package were performed using the resources of the Information Technology Research Center of Vilnius University and the supercomputer "VU HPC" of Vilnius University in the Faculty of Physics location.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study: in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEA |

Cohesion |

| HOMO |

The highest occupied molecular orbital |

| LUMO |

The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital |

| Gap |

HOMO-LUMO gap |

| CH |

Chemical hardness |

| ELN |

Electronegativity |

Appendix A

The view of Sulfur- and Fluorine containing derivatives

Code (Assignation) and Chemical Name:

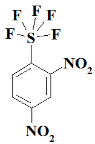

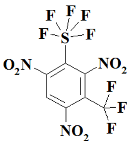

SF5N2---- 2,4-dinitro-1-(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)benzene;

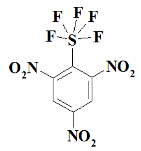

SF5N3---- 1,3,5-trinitro-2-(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)benzene;

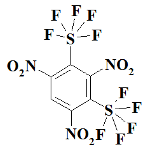

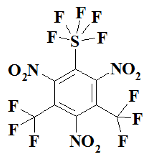

S2F10N3--1,3,5-trinitro-2,4-bis(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)benzene;

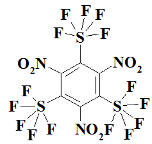

S3F15N3--1,3,5-trinitro-2,4,6-tris(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)benzene;

Code (Assignation) and Chemical Name:

CF3SF5N3------ 1,3,5-trinitro-2-(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzene;

C2F6SF5N3----- 1,3,5-trinitro-2-(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)-4,6-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzene;

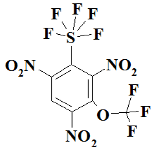

OCF3SF5N3---- 1,3,5-trinitro-2-(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)-4-(trifluoromethoxy)benzene;

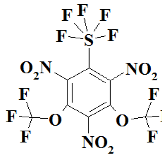

O2C2F6SF5N3- 1,3,5-trinitro-2-(pentafluoro-lambda⁶-sulfanyl)-4,6-bis(trifluoromethoxy)benzene;

The view of Fluorine-containing derivatives

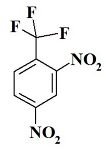

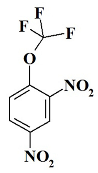

Code (Assignation) and Chemical Name:

CF3N2 --- 2,4-dinitro-1-(trifluoromethyl)benzene;

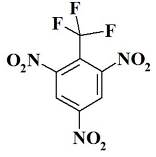

CF3N3 --- 1,3,5-trinitro-2-(trifluoromethyl)benzene;

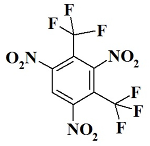

C2F6N3 - 1,3,5-trinitro-2,4-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzene;

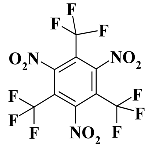

C3F9N3 - 1,3,5-trinitro-2,4,6-tris(trifluoromethyl)benzene;

Code (Assignation) and Chemical Name:

OCF3N2 ---- 2,4-dinitro-1-(trifluoromethoxy)benzene

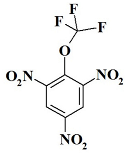

OCF3N3 ---- 1,3,5-trinitro-2-(trifluoromethoxy)benzene

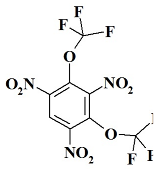

O2C2F6N3 - 1,3,5-trinitro-2,4-bis(trifluoromethoxy)benzene

O3C3F9N3 - 1,3,5-trinitro-2,4,6-tris(trifluoromethoxy)benzene

References

- Lin, H.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, C.; Yang, D.D.; Lou, N.; Zhu, S.G.; Li, H.Z. Dinitromethyl, fluorodinitromethyl derivatives of RDX and HMX as high energy density materials: a computational study. Struct. Chem. 2019, 30, 2401–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bai, T.; Guan, J.; Li, M.; Zhen, Z.; Dong, X.; Wang, Ya.; Wang,Yu. Novel fluorine-containing energetic materials: how potential are they? A computational study of detonation performance. J. Mol. Model. 2023, 29, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Song, X.L.; Yu, Z.H.; Song, D.; An, C.W.; Li, F.S. A high density and low sensitivity carrier explosive promising to replace TNT: 3-Bromo-5-fluoro-2,4,6-trinitroanisole. Energ. Mater. Front. 2024, 5, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H. , Ye, C., Winter, R.W., Gard, G.L., Sitzmann, M.E., Shreeve, J.N.M. Pentafluorosulfanyl (SF5) containing energetic salts. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 16, 3221–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, H.; Zheng, Z.; Dolbier, W.R.Jr. Energetic materials containing fluorine. Design, synthesis and testing of furazan-containing energetic materials bearing a pentafluorosulfanyl group. J. Fluor. Chem.y 2012, 143, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.; Shem-Tov, D.; Zhang, S.; Gao, C.Z.; Zhang, L.; Yao, C.; Flaxer, E.; Stierstorfer, J.; Wurzenberger, M.; Rahinov, I.; Gozin, M. Power of sulfur–Chemistry, properties, laser ignition and theoretical studies of energetic perchlorate-free 1, 3, 4-thiadiazole nitramines. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 443, 136246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. , Ghule, V.D., Dharavath, S. Advancing energetic chemistry: the first synthesis of sulfur-based C–C bonded thiadiazole-pyrazine compounds with a nitrimino moiety. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 19112–19115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamuliene, J.; Sarlauskas, J. Polynitrobenzene derivatives, containing -CF3, -OCF3, and -O(CF2)nO- functional groups, as candidates for perspective fluorinated high-energy materials: theoretical study. Energies 2024, 17, 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, M.E.; Ornellas, D.L.; The Effect of the Pentafluorothio (SF5S) Group on the Properties of Explosive Nitro Compounds: New SF5 Explosives. In PROCEEDINGS Ninth Symposium (International) on Detonation, August 28 - September 1. Red Lion Inn, Columbia River Portland, Oregon. 1989, Vol.2, p.p. 1162-1169. Available online: URL: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA247996. (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Becke, A.D. Density functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.H.Jr. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 09 W Reference; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Cardia, R.; Malloci, G.; Mattoni, A.; Cappellini, G. Effects of TIPS-Functionalization and Perhalogenation on the Electronic, Optical, and Transport Properties of Angular and Compact Dibenzochrysene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 5170–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardia, R.; Malloci, G.; Rignanese, G.M.; Blasé, X.; Molteni, E.; Cappellini, G. Electronic and optical properties of hexathiapentacene in the gas and crystal phases. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 235132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardenne, N.; Cardia, R.; Li, J.; Malloci, G.; Cappellini, G.; Blasé, X.; Charlier, J.C.; Rignanese, G. Tuning Optical Properties of Dibenzochrysenes by Functionalization: A Many-Body Perturbation Theory Study. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 24480–24488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antidormi, A.; Aprile, G.; Cappellini, G.; Cara, E.; Cardia, R.; Colombo, L.; Farris, R.; d’Ischia, M.; Mehrabanian, M.; Melis, C.; Mula, G.; Pezzella, A.; Pinna, E.; Riva, E.R. Physical and Chemical Control of Interface Stability in Porous Si–Eumelanin Hybrids. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 28405–28415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocci, P.; Cardia, R.; Cappellini, G. Inclusions of Si-atoms in Graphene nanostructures: A computational study on the ground-state electronic properties of Coronene and Ovalene. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 956, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocci, P.; Cardia, R.; Cappellini, G. Si-atoms substitutions effects on the electronic and optical properties of coronene and ovalene. New J. Phys. 2018, 20, 113008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Cardia, R.; Cappellini, G. Electronic and optical properties of chromophores from bacterial cellulose. Cellulose 2018, 25, 2191–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafran, M.; Koput, J. Ab initio and DFT calculations of structure and vibrational spectra of pyridine and its isotopomers. J. Mol. Struct. 2001, 565, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begue, D.; Carbonniere, P.; Pouchan, C. Calculations of Vibrational Energy Levels by Using a Hybrid ab Initio and DFT Quartic Force Field: Application to Acetonitrile. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2005, 109, 4611–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumar, B.; Arathala, P.; Muthiah, B. Thermal Decomposition of 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran behind Reflected Shock Waves over the Temperature Range of 1179–1361 K. Phys. Chem. A. 2021, 125, 5406–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arathala, P.; Musah, R.A. Oxidation of Dipropyl Thiosulfinate Initiated by Cl Radicals in the Gas Phase: Implications for Atmospheric Chemistry. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2021, 5, 2878–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free Chemical Drawing Software. ChemSketch. Version 10.0. ACD/Labs. Available online: https://www.acdlabs.com/resources/free-chemistry-software-apps/chemsketch-freeware/. (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Wen, L.; Wang, B.; Yu, T.; Lai, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y. Accelerating the search of CHONF-containing highly energetic materials by combinatorial library design and high-throughput screening. Fuel. 2022, 310, 122241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Martinez, J.; Murray, J.S.; Concha, M.C.; Toro-Labbé, A. An electrostatic interaction correction for improved crystal density prediction. Mol. Phys. 2009, 107, 2095–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.H.; Zamani, A. A simple and reliable method for predicting the detonation velocity of CHNOFCl and aluminized explosives. Cent. Eur. Energ. Mater. 2015, 12, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz, M.H.; Pouretedal, H.R. An empirical method for predicting detonation pressure of CHNOFCl explosives. Thermochim. Acta, 2004, 414, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ye, C.; Winter, R.W.; Gard, G.L.; Sitzmann, M.E.; Shreeve, J.M. Pentafluorosulfanyl (SF5) Containing Energetic Salts. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 3221–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Gard, G.L.; Winter, R.W.; Syvret, R.G.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J.M. Synthesis of pentafluorosulfanylpyrazole and pentafluorosulfanyl-1,2,3-triazole and their derivatives as energetic materials by click chemistry. Org. Lett. 2007, 3841–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džingalašević, V.; Antić, G.; Mlađenović, D. Ratio of detonation pressure and critical pressure of high explosives with different compounds. Sci. Tech. Rev. 2004, 5, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; Shreeve, J.M. Trifluoromethyl- or pentafluorosulfanyl- substituted poly-1, 2, 3-triazole compounds as dense stable energetic materials. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 4787–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlowitz, M.V.; Oberhammer, H.; Willner, H.; Boggs, J.E. Structural determination of a recalcitrant molecule (S2F4). J. Mol. Struct. 1983, 100, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemical and physical properties of Sulfur hexafluoride. Available online: URL https://www.chemicalbook.com/article/chemical-and-physical-properties-of-sulfur-hexafluoride.htm. (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Table of chemical bond energies – CALCULLA. https://calculla.com/bond_energy (Accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Chandler, J.; Ferguson, R.E.; Forbes, J.; Kuhl, A.L.; Oppenheim, A.K.; Spektor, R. Confined combustion of TNT explosion products in air. In Conference: 8th international Colloquium on Dust Explosions, Schaumburg, IL, September 21-25, 1998. Available online: URL: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/3648. (accessed on 8 February 2025).

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the cohesion dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the cohesion dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 2.

The figure illustrates the HOMO-LUMO dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 2.

The figure illustrates the HOMO-LUMO dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 3.

The figure illustrates the Chemical Hardness dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 3.

The figure illustrates the Chemical Hardness dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 4.

The figure illustrates the electronegativity dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 4.

The figure illustrates the electronegativity dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 5.

The figure illustrates the changeability of the density of the CF3-containing compounds when the group is replaced by -SF5. on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing by one -SF₅ group number from 0 on the left to 3 on the right.

Figure 5.

The figure illustrates the changeability of the density of the CF3-containing compounds when the group is replaced by -SF5. on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing by one -SF₅ group number from 0 on the left to 3 on the right.

Figure 6.

The figure illustrates detonation pressure dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Figure 6.

The figure illustrates detonation pressure dependence on the incorporation of the -SF₅ group. The colors represent compounds derived from different parent compounds, arranged in order of increasing SF₅ group number from left to right.

Table 1.

The obtained values of the cohesion (BEA), HOMO-LUMO gap (Gap), chemical hardness (CH), and electronegativity (ELN). The parameters of some compounds are repeated several times because they are the results of the completed replacement of CF3 or OCF3 groups by -SF5.

Table 1.

The obtained values of the cohesion (BEA), HOMO-LUMO gap (Gap), chemical hardness (CH), and electronegativity (ELN). The parameters of some compounds are repeated several times because they are the results of the completed replacement of CF3 or OCF3 groups by -SF5.

| Compounds |

BEA, eV |

Gap, eV |

CH, eV |

ELN, eV |

| C2F6N3 |

5.38 |

5.02 |

2.51 |

6.57 |

| CF3SF5N3 |

5.02 |

5.22 |

2.61 |

6.46 |

| S2F10N3 |

4.51 |

4.83 |

2.41 |

6.66 |

| CF3N2 |

5.47 |

4.94 |

2.47 |

6.14 |

| SF5N2 |

5.05 |

5.36 |

2.68 |

6.47 |

| CF3N3 |

5.43 |

4.73 |

2.36 |

6.53 |

| SF5N3 |

4.98 |

4.83 |

2.41 |

6.64 |

| C3F9N*/ |

5.39 |

5.01 |

2.50 |

6.66 |

| C2F6SF5N3 |

5.04 |

5.45 |

2.73 |

6.56 |

| CF3S2F10N3 |

4.65 |

4.87 |

2.43 |

6.81 |

| O2C2F6N3 |

5.00 |

4.96 |

2.48 |

6.44 |

| OCF3SF5N3 |

5.00 |

4.90 |

2.45 |

6.45 |

| S2F10N3 |

4.51 |

4.83 |

2.41 |

6.66 |

| O3C3F9N2 |

5.27 |

5.14 |

2.57 |

5.80 |

| O2C2F6SF5N3 |

5.00 |

5.07 |

2.54 |

6.42 |

| OCF3S2F10N3 |

4.65 |

4.75 |

2.38 |

6.75 |

| S3F15N3 |

4.31 |

4.72 |

2.36 |

6.89 |

Table 2.

The density of the fluorine-containing compounds obtained by the approach implemented in the ACD/ChemSketch program ( ρAC), by Gaussian ρG, and that suggested by Politizer et al. (ρ).

Table 2.

The density of the fluorine-containing compounds obtained by the approach implemented in the ACD/ChemSketch program ( ρAC), by Gaussian ρG, and that suggested by Politizer et al. (ρ).

| Compound |

ρAC, g/cm³ |

ρG, g/cm³ |

ρ, g/cm³ |

| CF3N2 |

1.74 |

1.98 |

1.60 |

| C2F6N3 |

1.82 |

2.34 |

1.79 |

| CF3N3 |

1.77 |

2.07 |

1.83 |

| C3F9N2 |

1.85 |

2.09 |

2.02 |

| O3C3F9N2 |

1.79 |

2.11 |

1.80 |

| O3C3F9N3 |

1.89 |

2.05 |

1.95 |

Table 3.

The density of the sulfur-fluorine-containing compounds obtained by the approach implemented in the ACD/ChemSketch program ( ρAC), and that suggested by Politizer et al. (ρ).

Table 3.

The density of the sulfur-fluorine-containing compounds obtained by the approach implemented in the ACD/ChemSketch program ( ρAC), and that suggested by Politizer et al. (ρ).

| Compound |

ρAC, g/cm³ |

ρ, g/cm³ |

| CF3SF5N3 |

2.35 |

2.09 |

| SF5N2 |

2.19 |

1.41 |

| SF5N3 |

2.20 |

1.88 |

| C2F6SF5N3 |

2.26 |

2.03 |

| CF3S2F10N3 |

2.84 |

2.40 |

| CF3SF5N3 |

2.35 |

1.89 |

| OCF3SF5N3 |

2.41 |

1.76 |

| S2F10N3 |

2.26 |

1.60 |

| O2C2F6SF5N3 |

2.27 |

2.07 |

| OCF3S2F10N3 |

2.41 |

1.76 |

| S3F15N3 |

2.48 |

2.05 |

Table 4.

The detonation pressure (P) and velocity (D) of the sulfur-fluorine-containing compounds obtained using a polynomial regression model within a machine learning framework.

Table 4.

The detonation pressure (P) and velocity (D) of the sulfur-fluorine-containing compounds obtained using a polynomial regression model within a machine learning framework.

| Compound |

P, kbar |

D. km/s |

| CF3SF5N3 |

297.8 |

7.55 |

| SF5N2 |

160.4 |

6.41 |

| SF5N3 |

295.6 |

7.53 |

| C2F6SF5N3 |

325.2 |

7.73 |

| CF3S2F10N3 |

369.9 |

7.99 |

| OCF3SF5N3 |

335.2 |

7.79 |

| S2F10N3 |

222.9 |

6.97 |

| O2C2F6SF5N3 |

332.0 |

7.77 |

| OCF3S2F10N3 |

267.3 |

7.99 |

| S3F15N3 |

286.7 |

7.47 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).