1. Introduction

Energy plays a pivotal role in shaping a country's economy, infrastructure, transportation, and overall standard of living. However, a critical issue faced globally is the imbalance between energy availability and consumption, which exacerbates environmental and economic challenges. Currently, all countries rely heavily on fossil fuels for energy generation—resources that are inherently finite and unsustainable. To meet the escalating energy demands of a growing global population, it is essential to transition towards alternative, sustainable energy sources that do not harm the environment [(Hosseini, Andwari, et al., 2013), (Granovskii et al., 2007)].

In recent decades, the United States has taken significant steps to reduce petroleum dependency and mitigate the environmental impacts of the transportation sector. One of the primary challenges associated with the current energy landscape is the depletion of non-renewable fossil fuels, which not only threatens the sustainability of the energy industry but also contributes to broader environmental issues such as the greenhouse effect [(Derbeli et al., 2018), (Hosseini, Wahid, et al., 2013)]. The use of fossil fuels remains substantial today, and projections indicate that by 2050, they will still account for approximately 75% of global energy production (Eriksson & Grey, 2017).

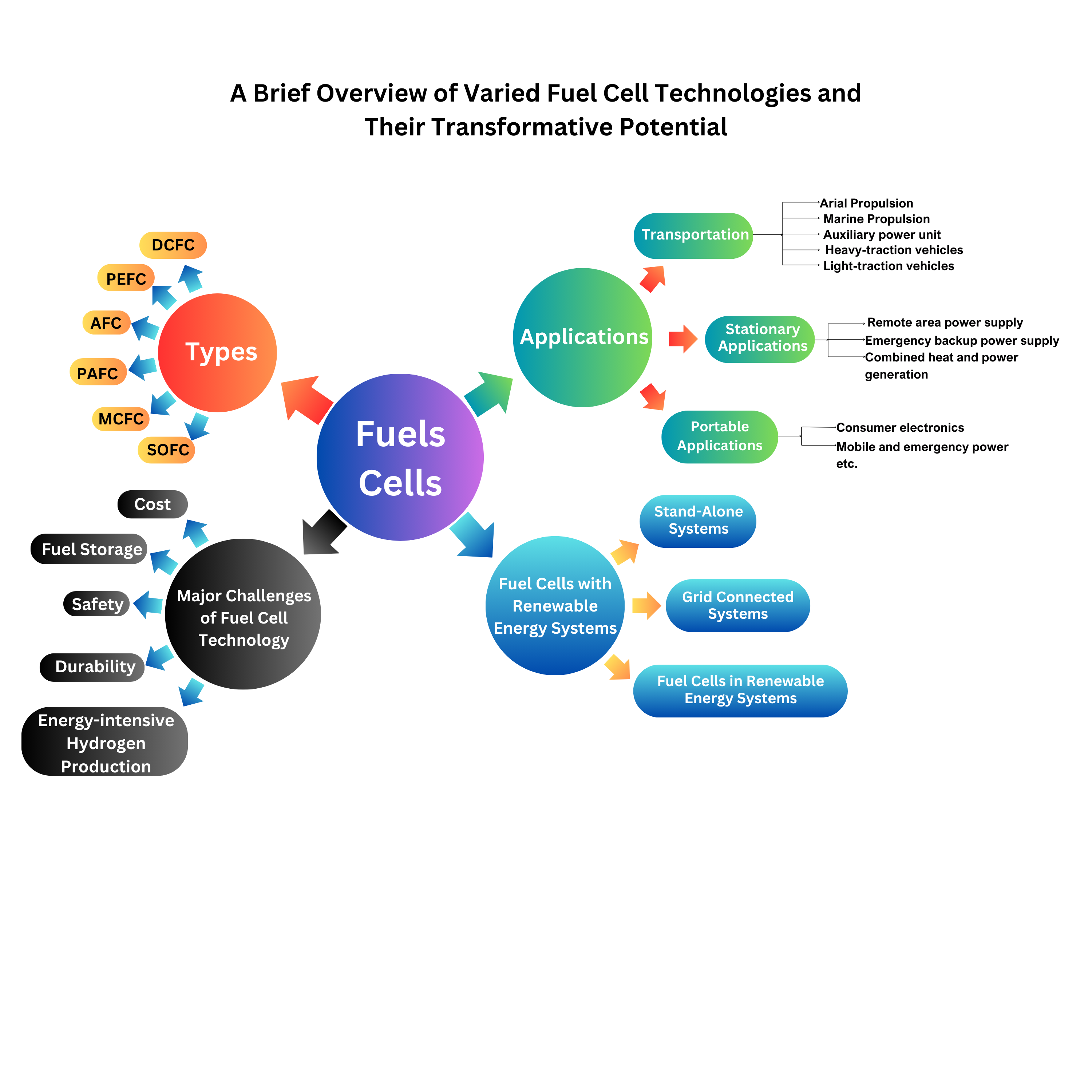

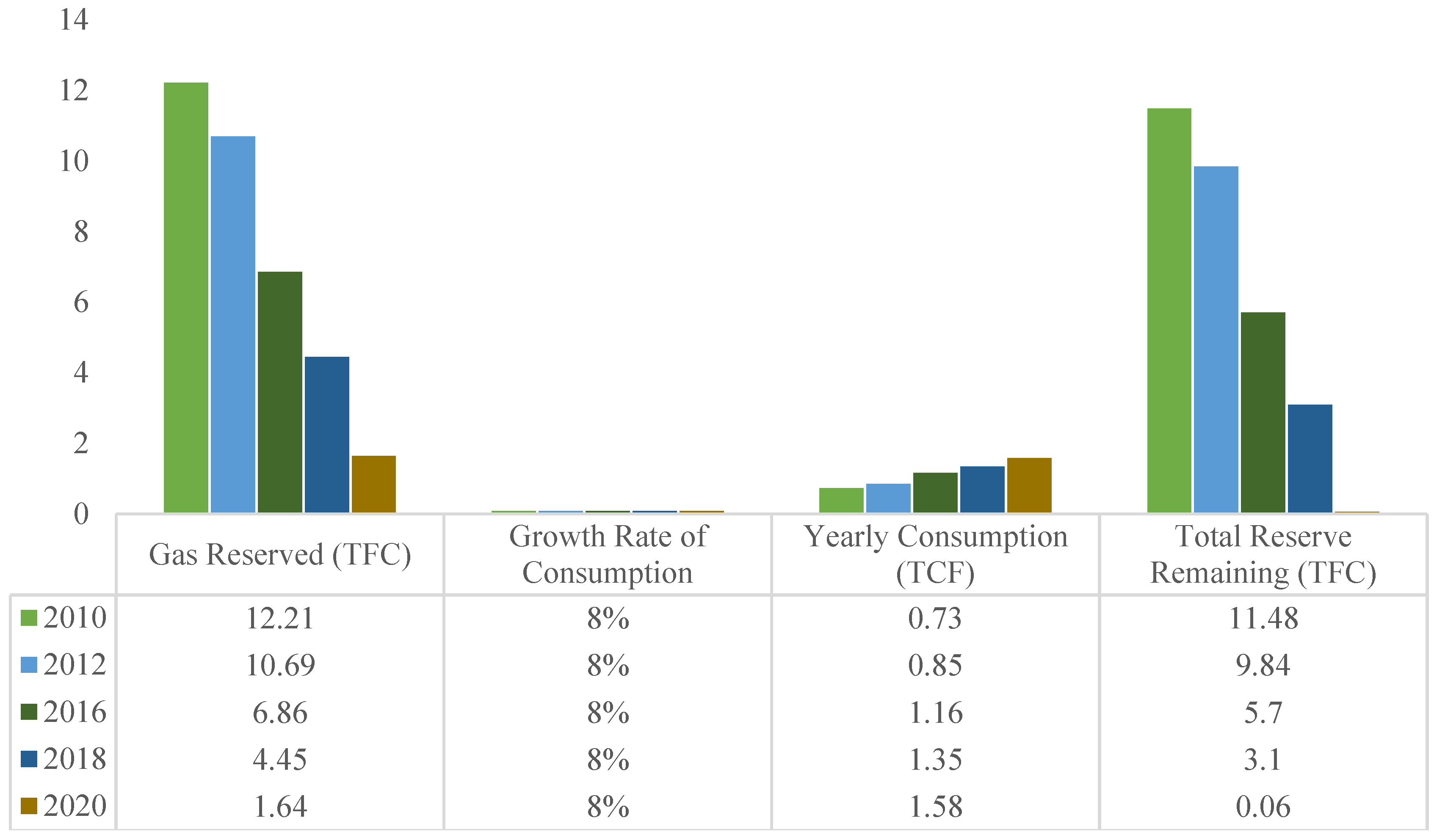

As depicted in

Figure 1, the decline in gas reserves from 2010 to 2020 illustrates this trend, highlighting the steady increase in consumption over time while the remaining reserves continue to dwindle. Notably, the consumption growth rate remains consistent at 8% annually, underscoring the urgency of finding alternative solutions.

This steady depletion of fossil fuels poses a serious challenge, forcing many industries to scale back production due to limited gas supplies. In this case, fuel cells are emerging sources of energy that require special attention. A fuel cell is an electrochemical device which uses the chemical energy of a fuel and transforms it into electrical energy directly. Fuel cells are different from traditional combustion-based heat engines in that they have fewer processes and steps involved in energy production as fuel cells have a direct, more efficient, and sustainable conversion method.

The negative impact of using conventional sources for energy generation, especially those relying on combustion, is now clear. It contributes to some of the world’s biggest issues today which include climate change, depletion of ozone layer, acid rain, and continuously destroying plant ecosystems. Also, these methods are reliant on fossil fuels which are scarce, making the problem worse. This is done while using the fuel cells as they are cleaner and more efficient in converting energy. Also It is possible to integrate fuel cells with renewable sources such as hydrogen to further promote sustainability and energy security.

Due to their applicability, fuel cells are regarded as a fundamental component of the future energy systems. They can be employed across various applications, including portable, stationary, and transportation power generation. Their quiet operation, devoid of noise and vibration, further contributes to their appeal. In essence, fuel cells represent one of the most efficient, clean, and adaptable methods of converting chemical energy into electricity.

As seen in

Table 1, while diesel engines boast the highest capacity, fuel cells are unparalleled in efficiency, achieving up to 85%. Furthermore, the capital cost per kilowatt for fuel cells is relatively low, making them a cost-effective solution in the long run. For these reasons, the use of fuel cells is on the rise, becoming an increasingly prominent topic in power generation discussions.

In this paper, we will explore the current state of fuel cell technology, examine the various types of fuel cells, and discuss their applications in different sectors of the energy market.

2. Energy Storage System

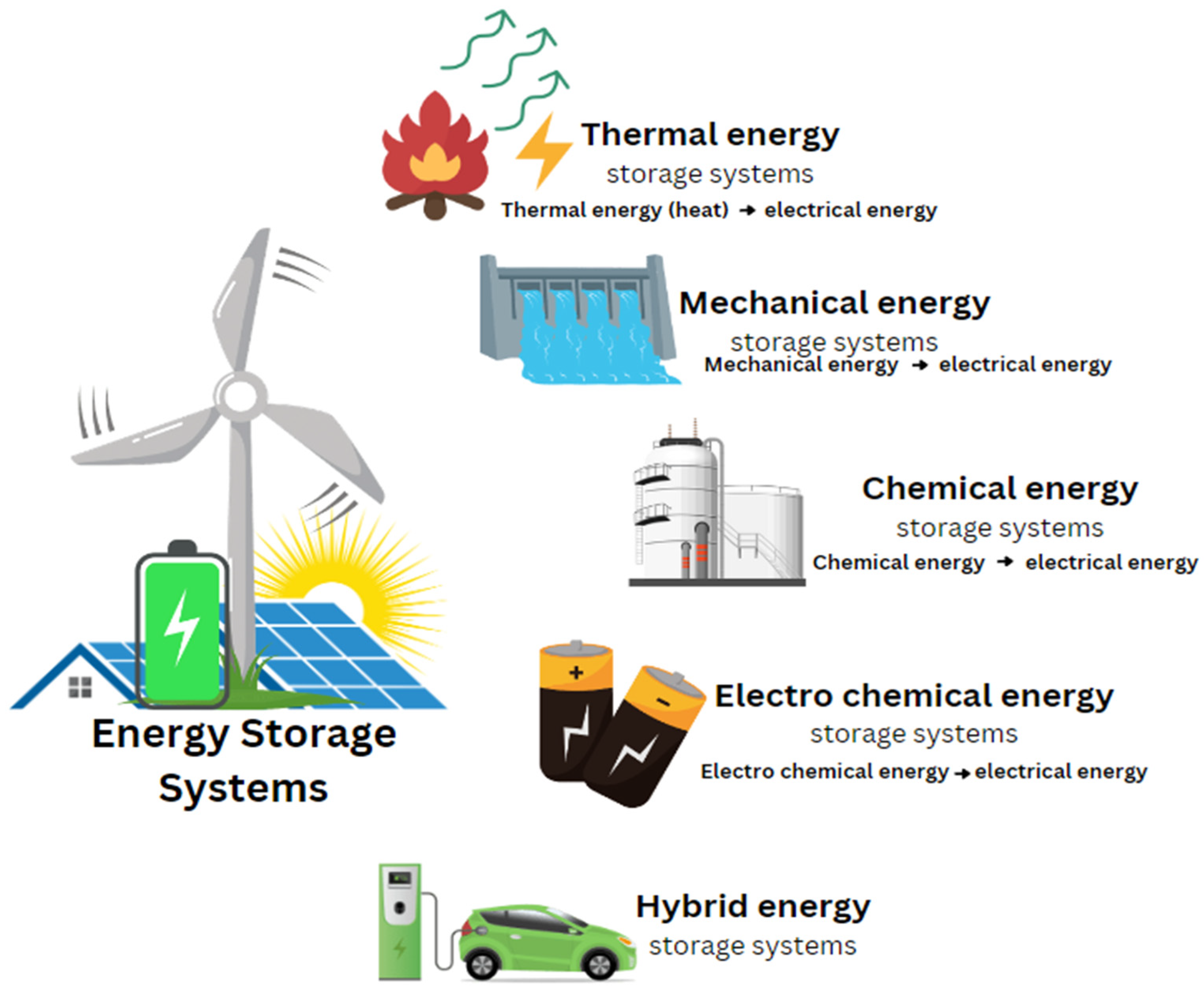

An Energy Storage System (ESS) is a device or a set of interconnected devices designed to store energy for later use. The storage capacities of ESS are typically measured in terms of energy (MWh) and power (MW), reflecting their ability to hold and release energy. There are various methods of storing energy, including thermal, mechanical, chemical, electrochemical, electrical, and magnetic fields. Additionally, energy can be stored in hybrid systems that combine two or more of these methods.

As shown in

Figure 2, the classification of ESS encompasses a wide range of technologies, each with its unique mechanisms for energy storage. According to

Table 2, these systems are categorized based on the specific form of energy they store, offering distinct advantages depending on their application. Before deployment, over 45 types of ESS are compared across 20 technical variables to determine the most suitable solution for a given energy storage need. This comprehensive comparison helps in understanding the strengths and limitations of each type, ensuring optimal selection and implementation.

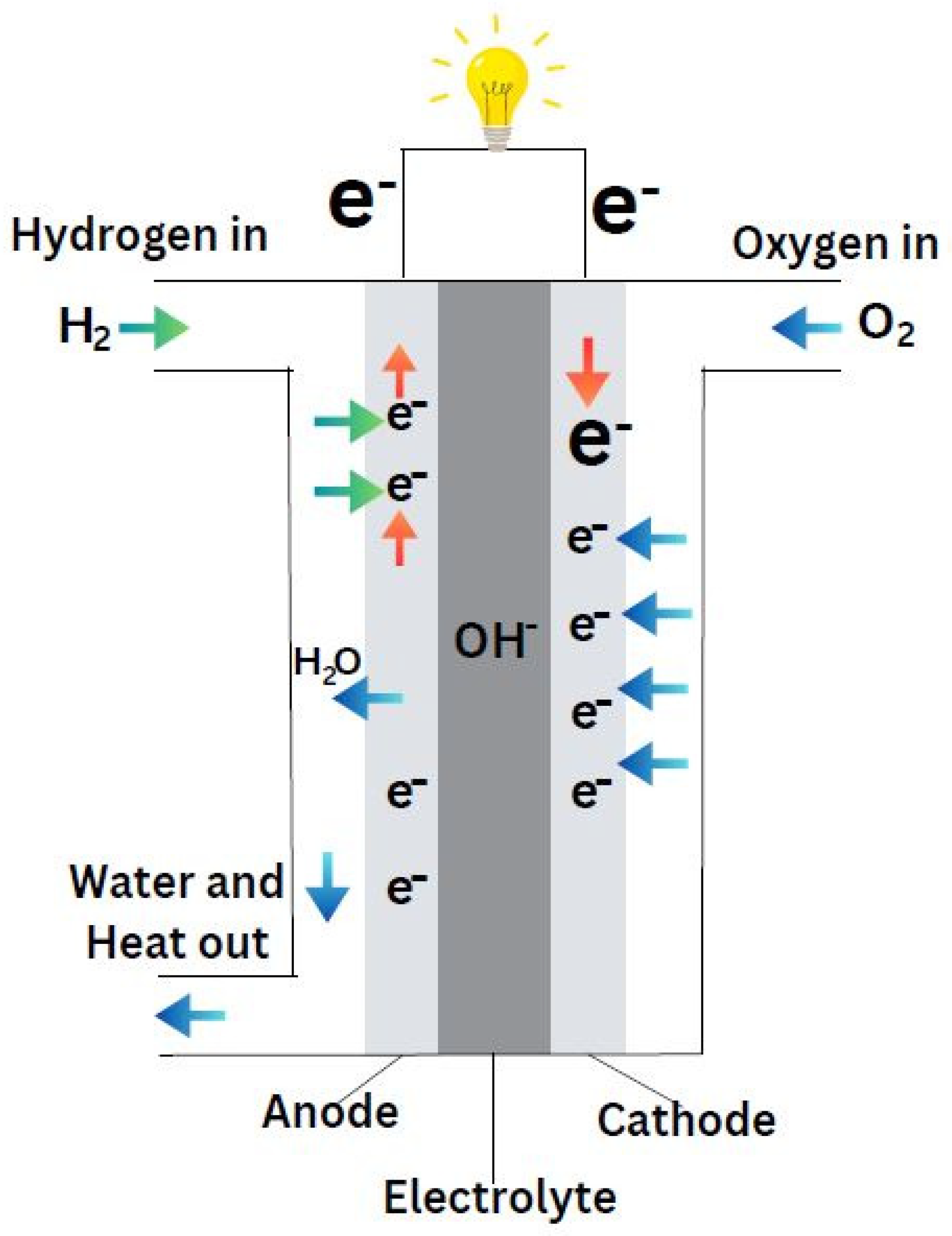

3. Working Principle of Fuel Cell

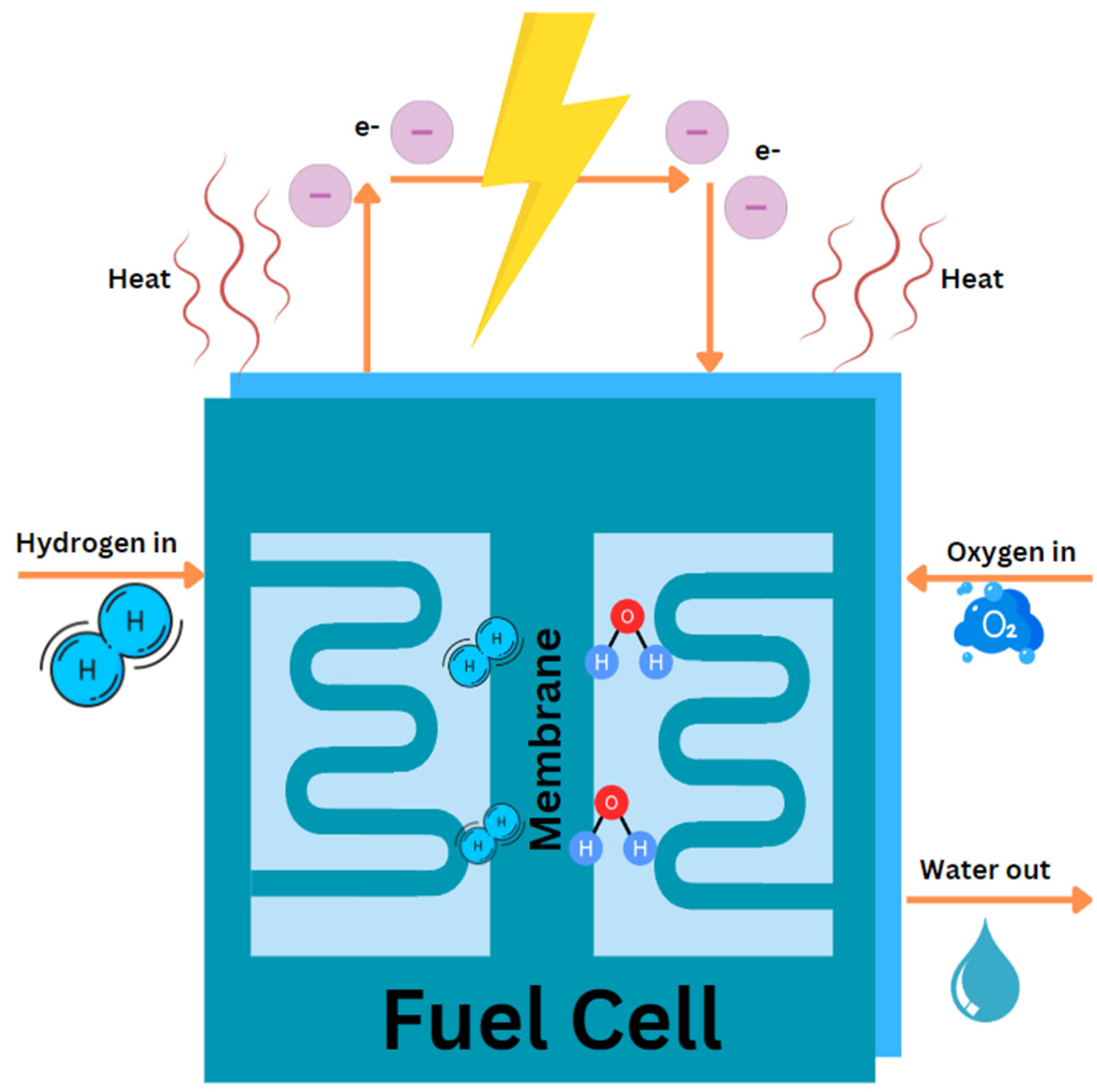

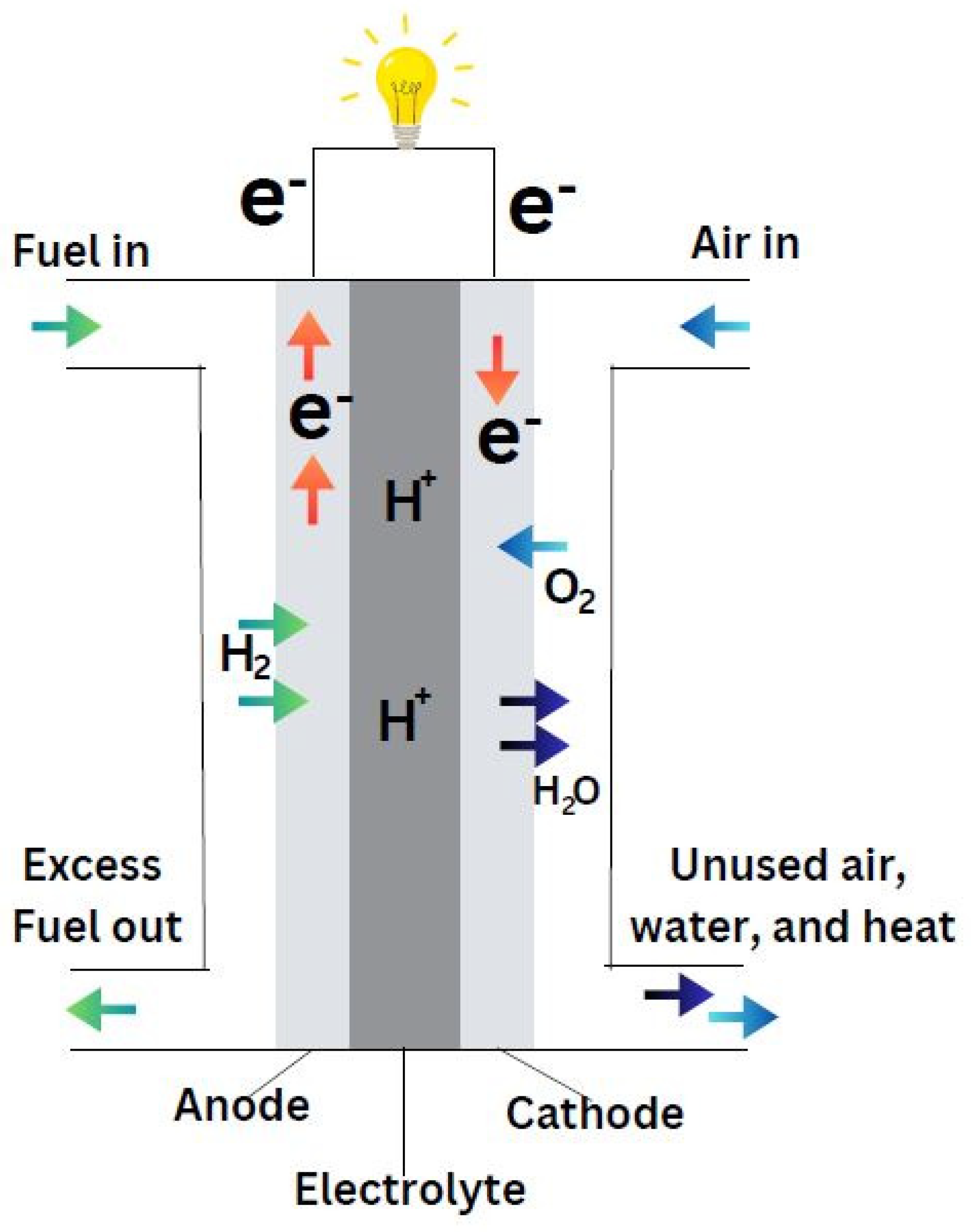

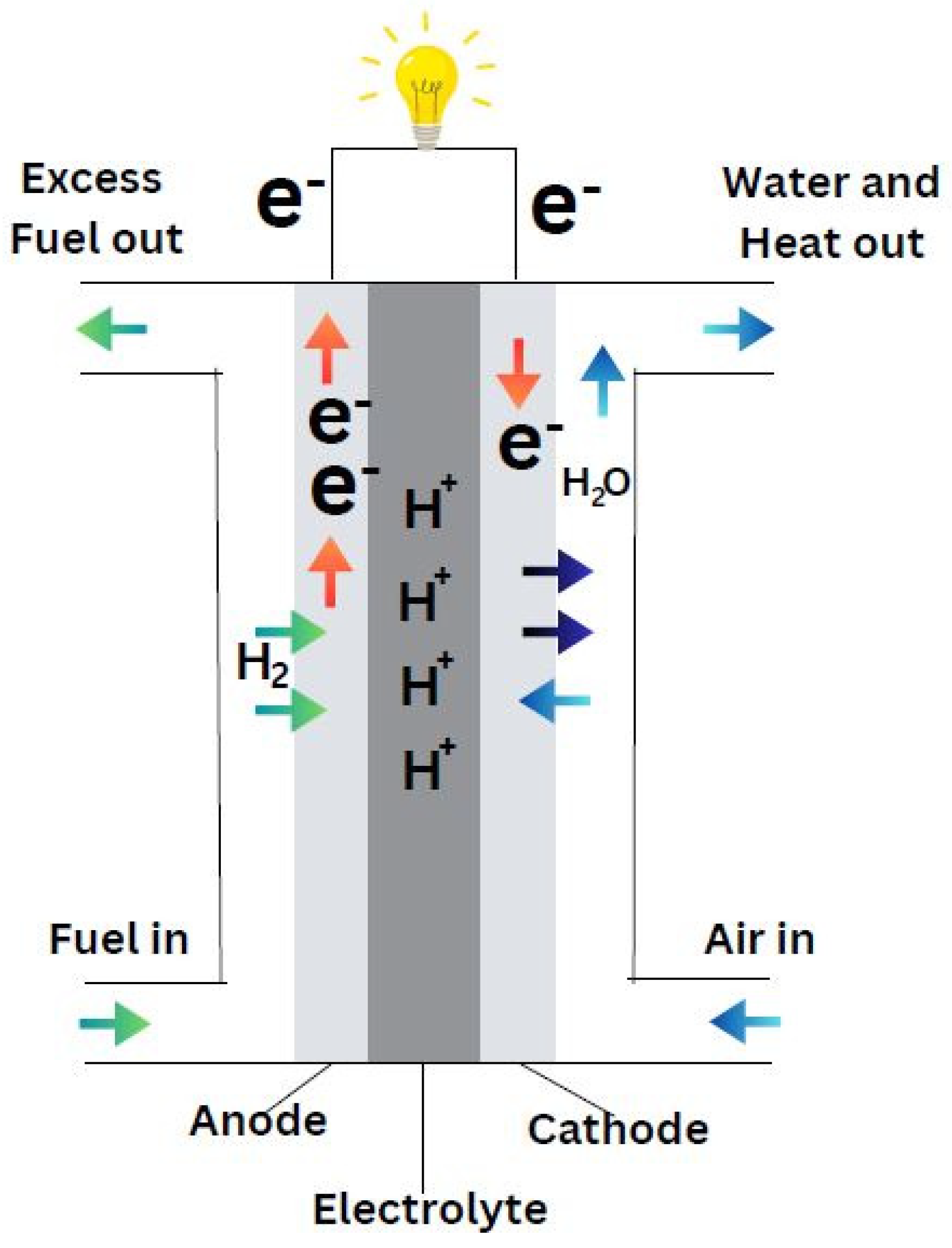

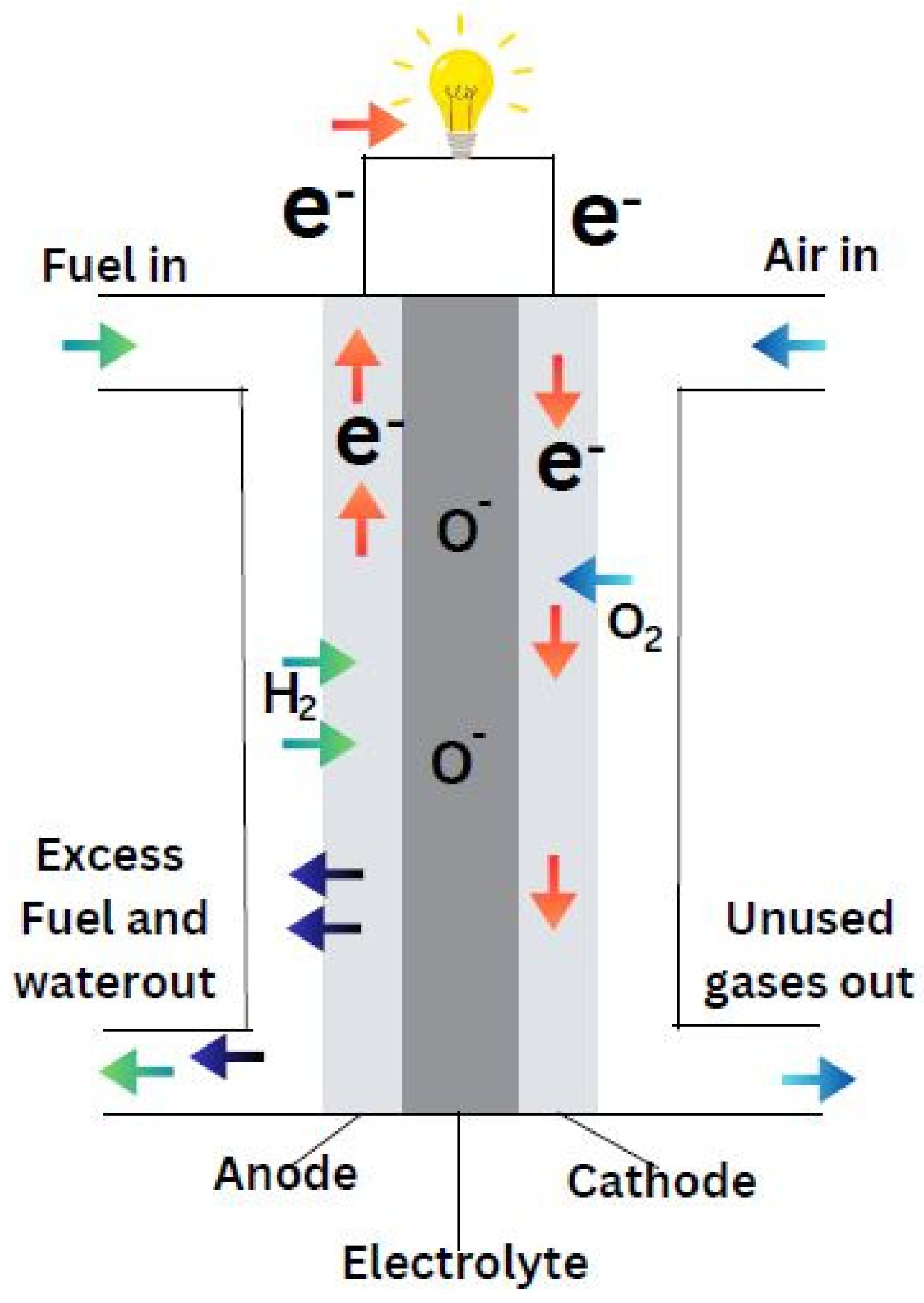

Fuel cells are efficient devices that turn the inherent chemical energy of fuel (hydrogen) into electricity for a variety of applications. Fuel cells emit only heat and water vapour, making them a clean energy source. If the system is supplied with fuel and oxygen, energy can be generated continuously. Fuel cell efficiency is around 20-30% greater than typical combustion engines, and they operate extremely silently owing to the lack of moving parts. Fuel cells are of different types based on the selection of electrolyte. Apart from the electrolyte, the other main parts include cathode, anode and load, an external circuit. Hydrogen is supplied at the anode and is divided into positive ions and negative ions or electrons through oxidation. Whereas oxidants are supplied to the cathode from the air. The protons or positive ions traverse the electrolytic medium, separating anode and cathode plates, and the electrons from the anode come through the external circuit towards the cathode. Consequently, reduction reaction takes place at cathode and generates water from the interaction among cations, electrons and O2. This transfer of electron from anode to cathode results in the current output from fuel cell (Sazali et al., 2020).

Demonstrated by the

Figure 3, the fuel cell converts hydrogen and oxygen into electricity, producing water and heat as byproducts. The whole process can be considered as a reversed electrolysis reaction and showed in following equations:

Various types of fuel cells employ different materials, yet the fundamental reactions remain same between hydrogen and oxygen. The electrolytes play a pivotal role in preventing short circuits by establishing insulation and aversion of electron conductivity, only allowing ionic transportation between electrodes. (Guaitolini & Fardin, 2018) Despite its high theoretical efficiency at approximately 83%, further improvement can be attained by considering thinner electrolyte layers and electrodes with flat and porous surfaces (Mekhilef et al., 2012).

4. Types of Fuel Cells

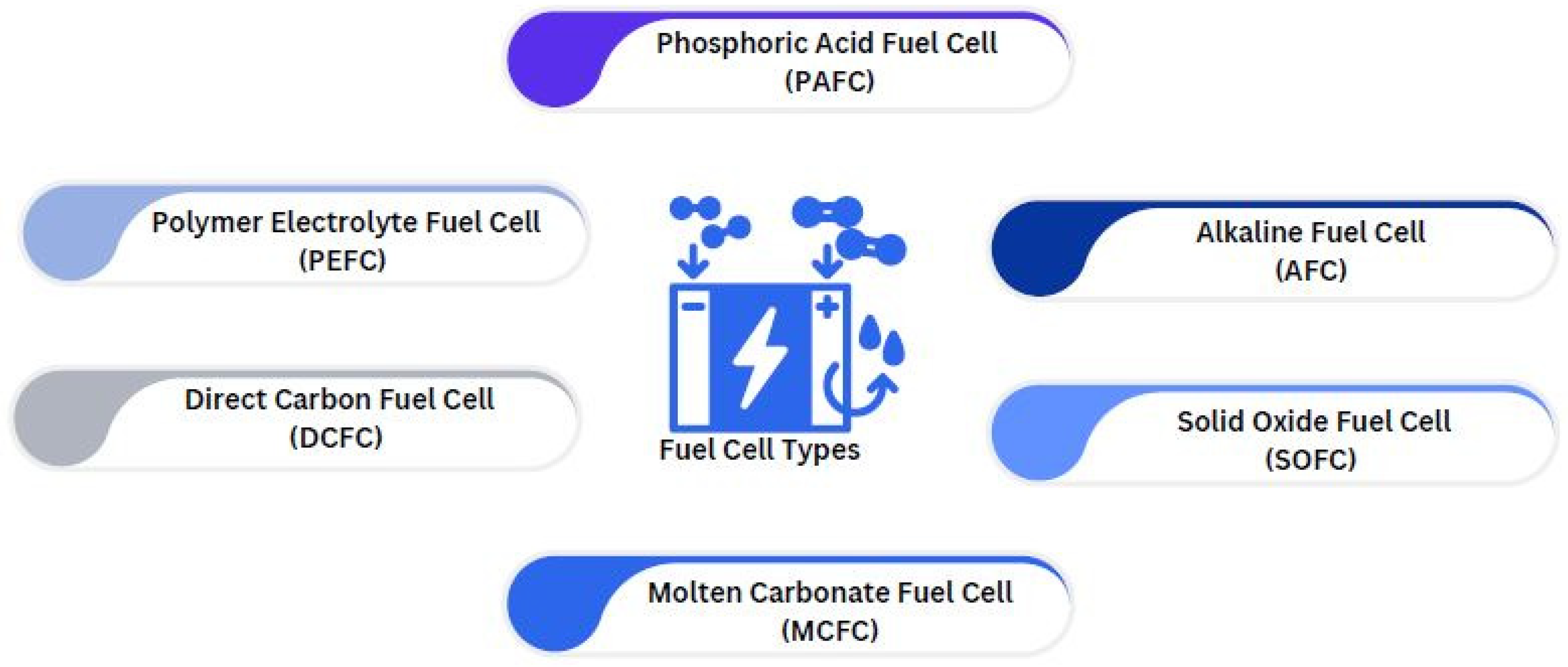

Many geometries, such as planar, tubular, radial, and others, as well as a variety of fuels and electrolyte charge carriers, may be used in the construction of fuel cells, which can include single chamber, dual chamber, and other configurations (Turco et al., 2016). The charge carrier, operating temperature, and kind of electrolyte used in the cells are the initial elements that distinguish different types of fuel cells (Office, n.d). Fuel cells are currently being developed in a number of configurations, each with its own set of advantages, limitations, and potential applications.

Figure 4 shows the types of fuel cells that have been researched and developed:

4.1. Direct Carbon Fuel Cell (DCFC)

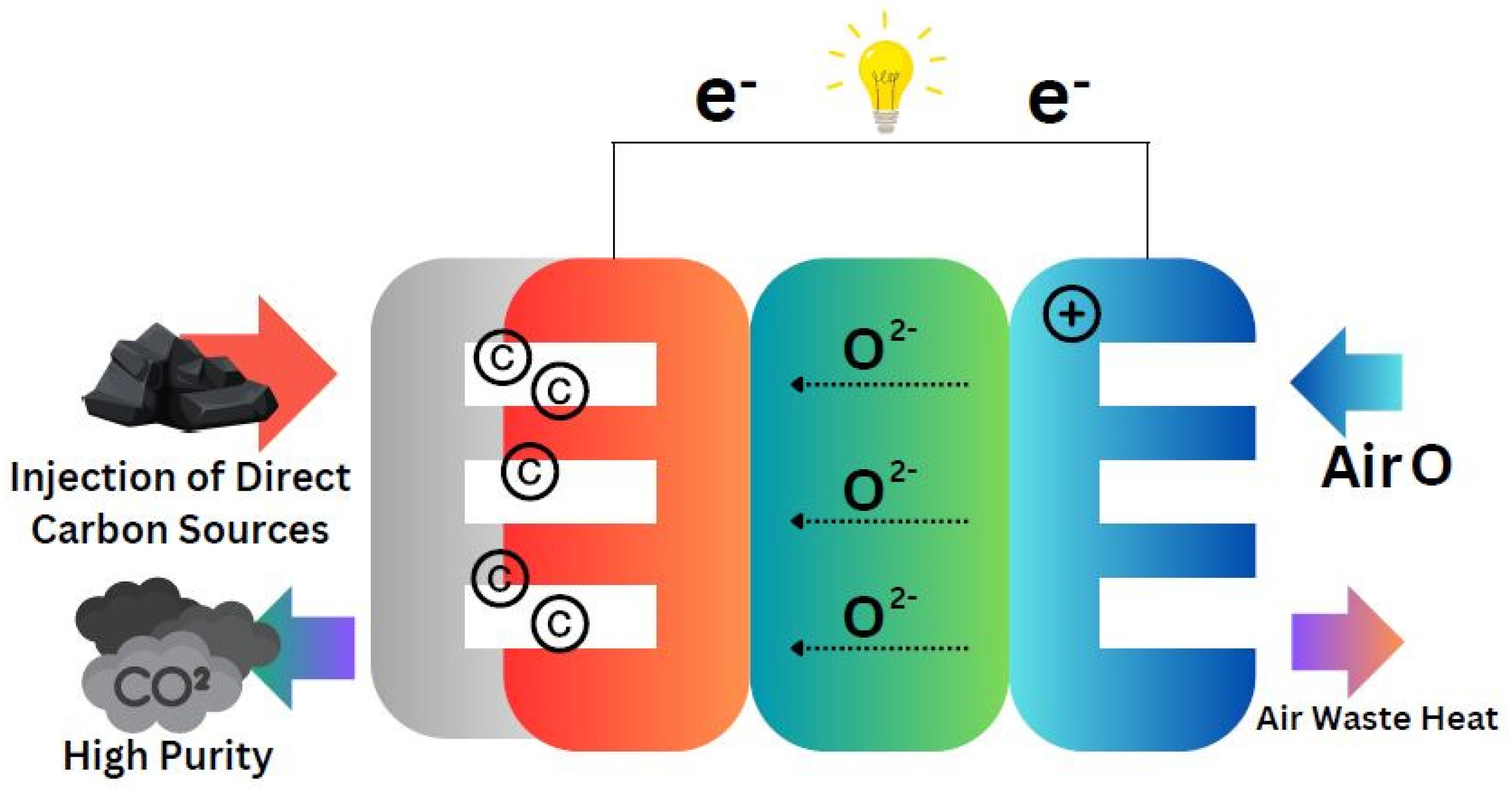

Direct Carbon Fuel Cells (DCFCs) represent a pioneering approach to energy conversion, using solid carbon as fuel and directly transforming its chemical energy into electrical energy through electrochemical oxidation (Giddey et al., 2012). Unlike traditional heat engines, DCFCs achieve higher energy conversion efficiency, simplify system design, and reduce costs. A remarkable feature of these cells is their nearly 100% thermodynamic efficiency, positioning them as an attractive innovation due to both their high energy efficiency and the abundance of carbon as a fuel source. Among various types of DCFCs, the Direct Carbon Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (DC-SOFC) and Direct Carbon Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells (DC-MCFC) are particularly noteworthy. The performance and power densities of these fuel cells are significantly influenced by the carbon's quality and structure, which also affect electrode kinetics during the direct oxidation process.

The

Figure 5 depicts the process in which DCFCs operate carbon sources are injected into the system for oxidation. The output of this process is high-purity CO2 along with electrons that can be utilized for electricity generation. Electricity is produced from the flow of electrons while the oxidation reactions depend on the contribution of air and oxygen, making the system efficient. This process of energy conversion is simplified and yields high efficiency, which enhances the promise of DCFC technology as a viable option for sustainable energy. Comprehensive summary analysis and experimental approaches regarding the performance of DCFCs are captured in

Table 3. These analyses are aimed on the performance of variety of electrolytes and their contribution in efficiency of DCFC, which can help to optimize DCFC technologies for better performance.

Recent progress by Ozalp and colleagues in 2022 tackles anode-side currents and concentrations in novel anode interfaces for improved DCFC performance. Direct Fuel Cell (DFC) technology has come a long way since 1896 and makes use of existing technologies pouring transferrable knowledge from Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells (MCFC), Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC), and Alkaline Fuels Cells (AFC) into harnessing its full potential (Rady et al.,2012). Another area with active research is the use of carbon nanoparticles which, because of their large surface area and high reactivity, could greatly impact negatively or positively be very positive to the DCFC performance. Those like Wang et al. (2021) looked closely to analyze the electrochemical reactivity in molten salts and how it relates to the nanostructure of carbon. The disordered state of carbon atoms is shown to have a large impact on electron yield and the more disordered carbon atoms, the more reactive they become (Cui et al., 2021). These is more important than either surface area or purity of carbon as a contributor to Direct Fuel Cell performance.

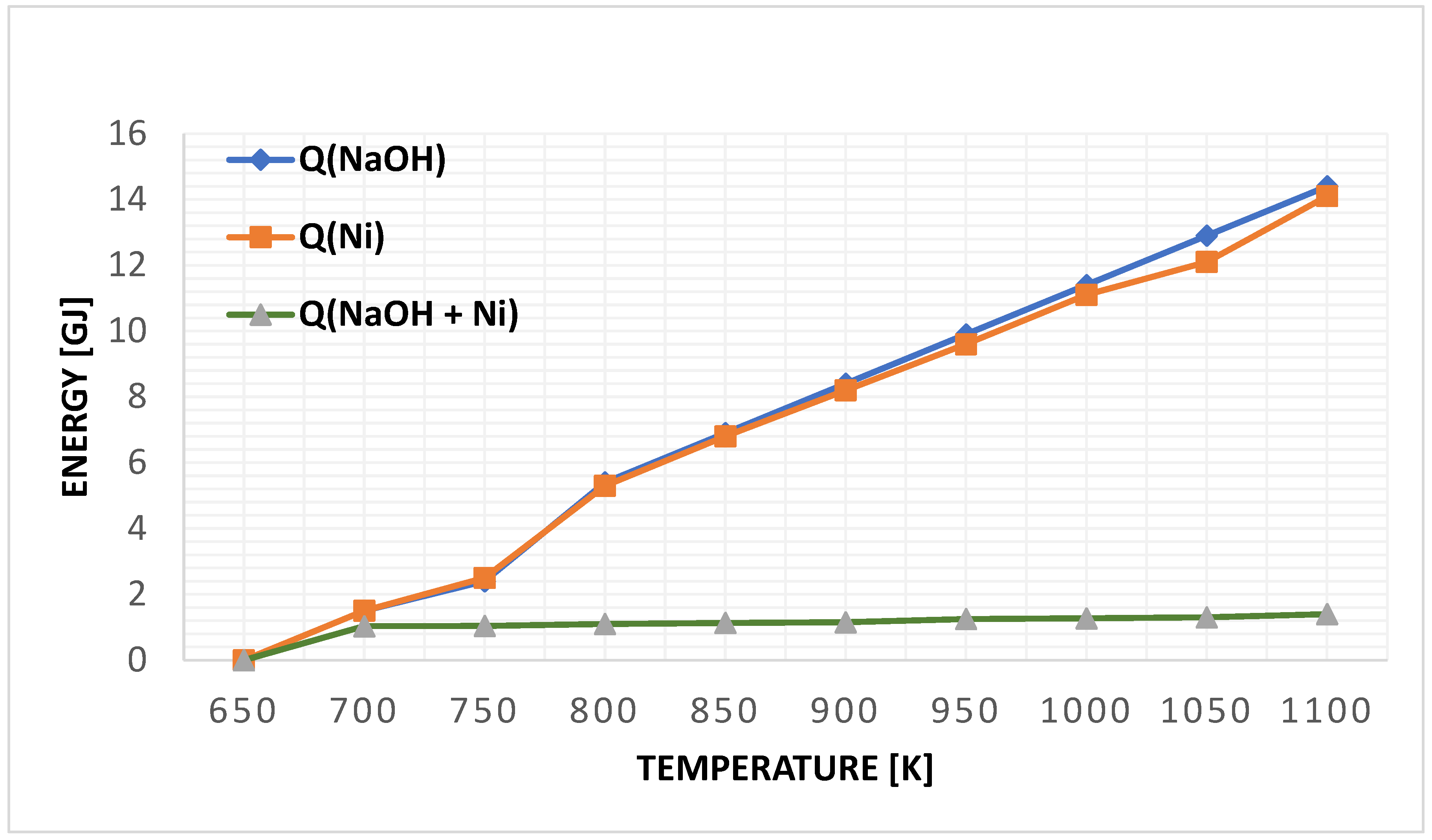

Figure 6 illustrates the heat accumulated in the electrolyte material (NaOH) and the primary components of the Ni cell. The total heat stored in the cell is depicted by the inclined green line, emphasizing the energy management in the DCFC system. This detailed analysis contributes to the understanding of the factors that influence DCFC performance and highlights the significant progress made in the technology.

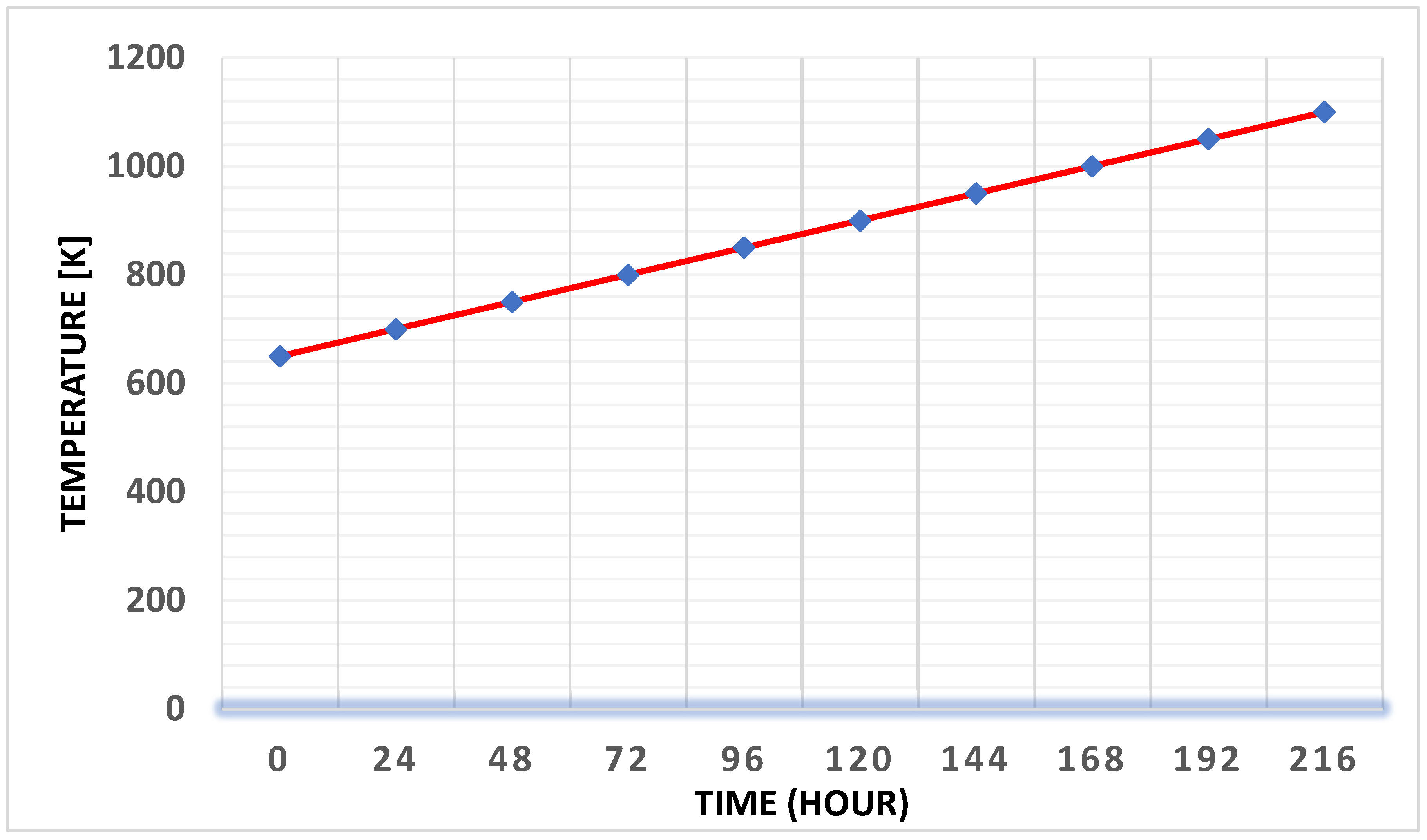

Figure 7 presents the temperature profile of a 25 kW fuel cell over time, which reveals how temperature dynamics are integral to fuel cell efficiency. As indicated by this data, DCFC development heavily depends on advancements in both the anode and anode chamber design. The reactor configuration, whether batch or flow, is influenced by the purity of the solid graphite particles (Rady et al., 2012). Extensive research on anode materials for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) has shown that transition metal carbides such as tungsten, vanadium, zirconia, and titanium carbides, along with nickel and carbon, outperform traditional graphite anodes. Among these, vanadium carbide has proven to be especially effective in activating carbon solids.

The redox processes at the anode play a crucial role in carbon activation, but anode oxidation can hinder electrochemical reactions, especially in minerals like titanium carbide (TiC), which require oxygen for oxidation and do not show a direct relationship between CO evolution and current density. Wang et al. (2021) highlight several critical research needs for molten carbonate-type DCFCs to optimize their performance. These include understanding the wetting behavior of various carbon types in melts, which varies with basicity, cation composition, and temperature; characterizing molten carbonate in reducing solutions with carbon to identify stable versus semi-stable species; and employing molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate the stability of CO-CO2 and carbon-carbonate structures in the melt. Additionally, Monte Carlo modeling is essential for analyzing the interactions between carbon particle assemblies, carbonate melt, and gas bubbles (CO2, CO), as well as the electrochemical processes, buoyant forces, and interfacial interactions. This research underscores the importance of anode material and chamber design in enhancing DCFC efficiency. While significant progress has been made, ongoing innovation is critical to fully unlocking the potential of DCFCs, and continued research is key to advancing this technology toward a sustainable energy future.

4.2. Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cell (PEFC)

Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells (PEFCs) utilize a polymer electrolyte membrane as the core electrolyte material, with an electrode and a gas diffusion layer positioned on either side. These Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEFCs) are regarded as one of the most promising clean energy technologies due to their high energy density, environmental friendliness, and efficiency. A bibliometric review of research trends in PEFCs between 2008 and 2018 underscores the significant advancements and growing interest in this innovative field.

As illustrated in

Table 4, which outlines recent research on PEFCs, substantial progress has been made in enhancing cell performance and reducing manufacturing costs, both critical factors for the growth of the fuel cell industry (OTA et al., 2016). PEFCs typically operate at temperatures below 100°C, generally ranging between 60 and 80°C. Despite a theoretical open-circuit voltage (OCV) of 1.23 V, practical operation is limited to a maximum of 1.1 V due to electrode non-equilibrium (Espinoza-Andaluz et al., 2019). Their high current densities, rapid response to load variations, and high-power densities make them particularly suitable for various applications, including vehicle power systems. The use of hydrogen as fuel, combined with the advantage of low operating temperatures, allows for quick starts and efficient performance.

This review emphasizes the vast potential of PEFCs to transform clean energy systems, showcasing ongoing research efforts aimed at optimizing performance and reducing costs. As shown in

Figure 8, the design and structure of PEFCs continue to evolve, driving these advancements in the field.

A significant challenge for PEFCs is the presence of carbon monoxide (CO) in the fuel stream, which can contaminate platinum catalyst sites. To solve the above, PEFCs have to run at temperatures higher than 120° C. At the moment, fully fluorinated Teflon-based membranes- Nafion, are widely used. This research aims at preventing CO poisoning along with achieving higher operating temperatures to improve the performance and lifetime of PEFCs membranes and multifunctional polymers for more effective fuel cell polymer.

Also, the performance of PEFCs is extremely dependent on the temperature and pressure operating. Nowadays, temperature of 80° C and pressure of 1.0 Mpa is the operational limit for modern PEFCs. However, there is much more scepticism about the use of higher pressure operations. This research is very important for the all-in-one PEFC development to boost the efficiency and performance. The following reaction equations prove the electrochemical reactions in PEFCs have, as in the case of other fuels cells, the original features:

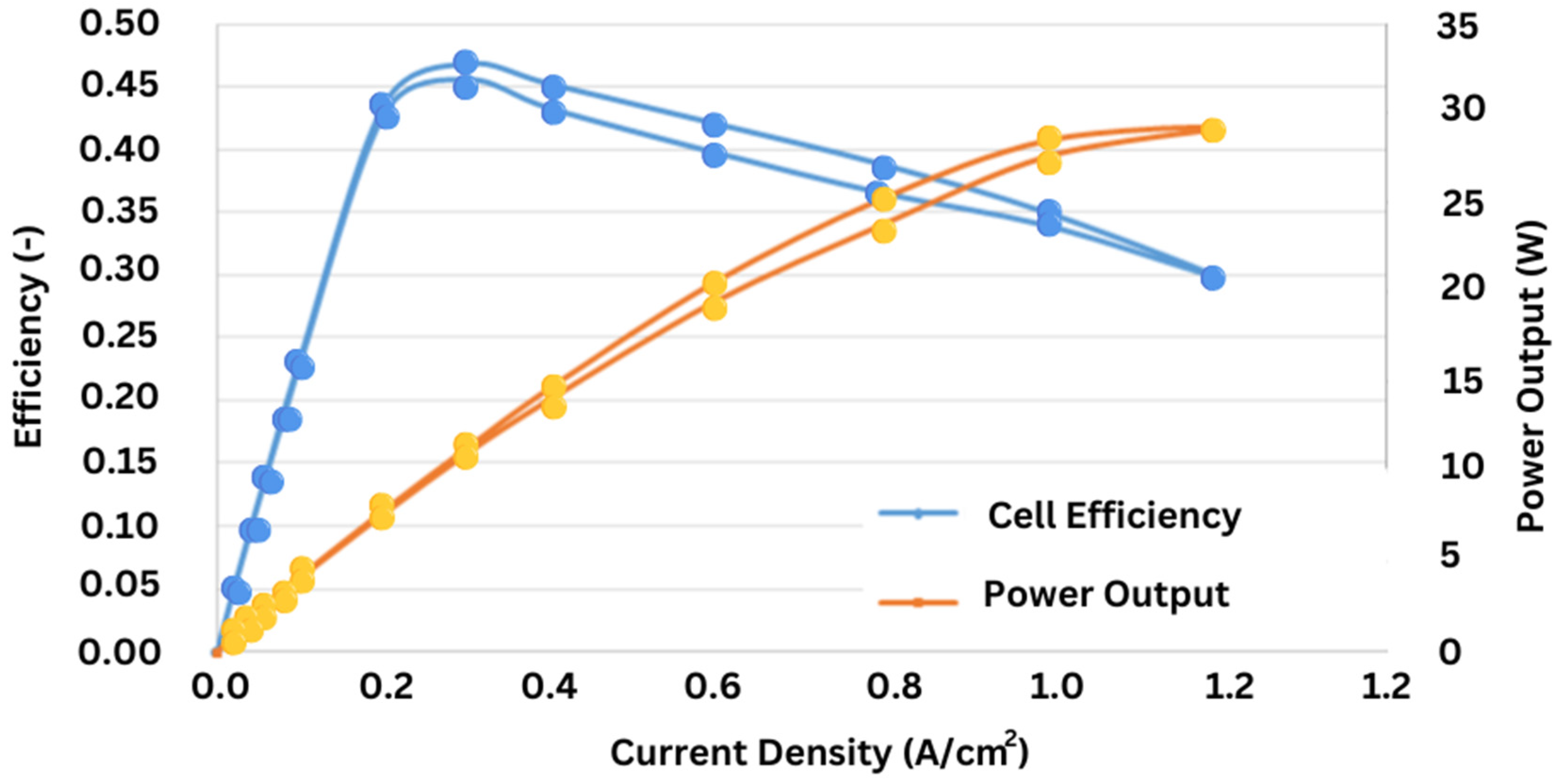

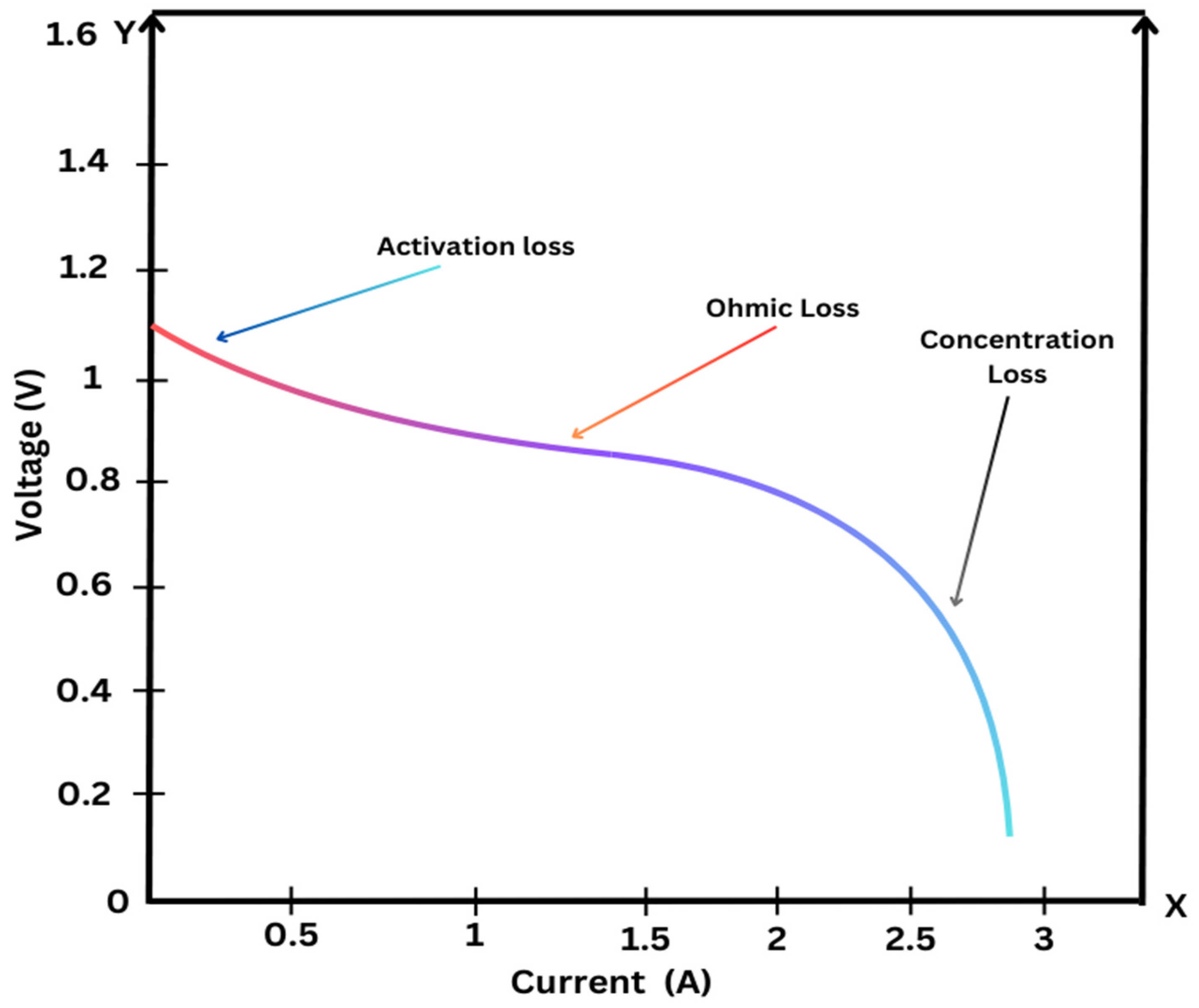

To fully understand the performance characteristics of PEFCs, several graphs are provided below that demonstrate the system's behavior under various conditions:

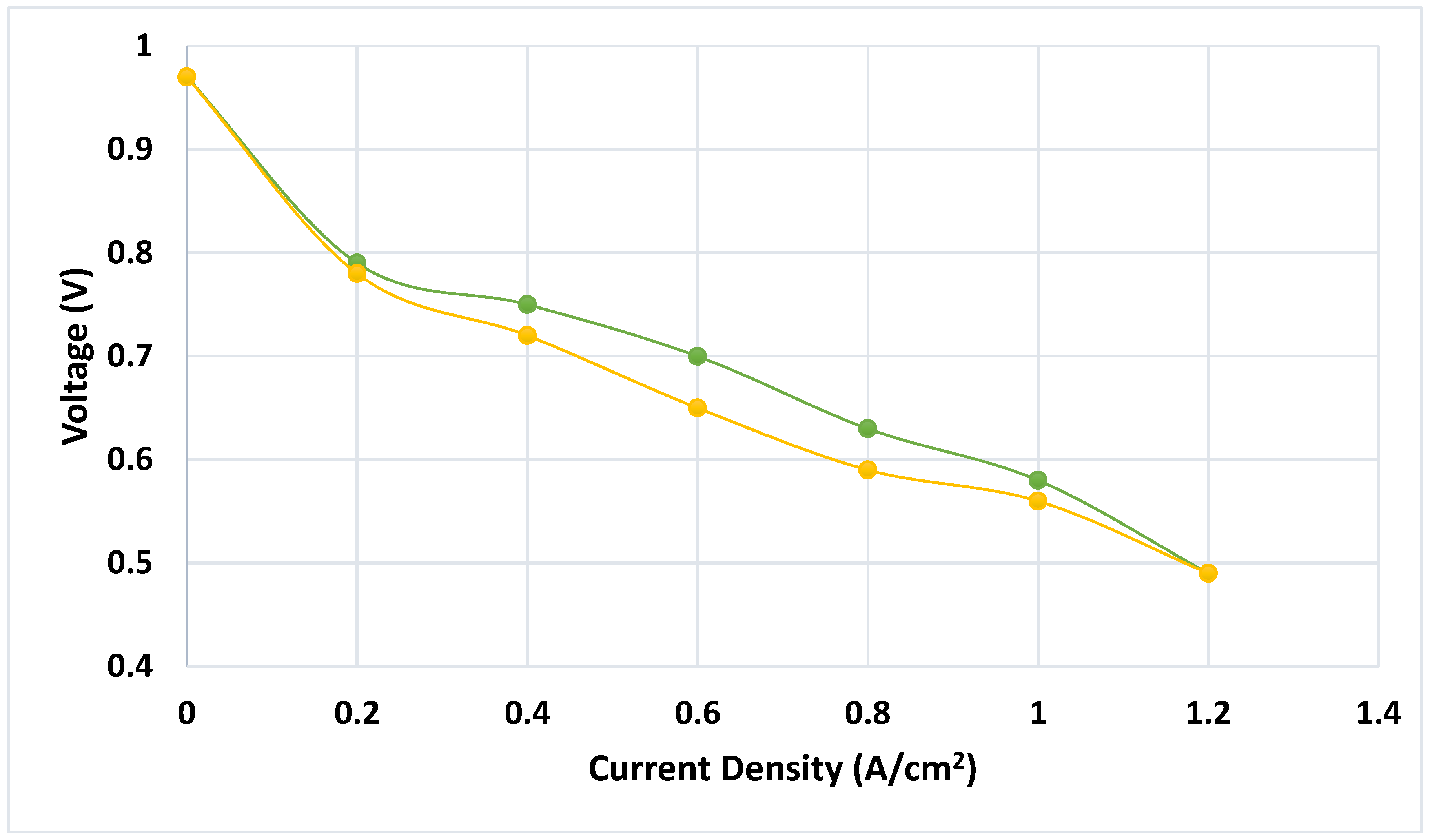

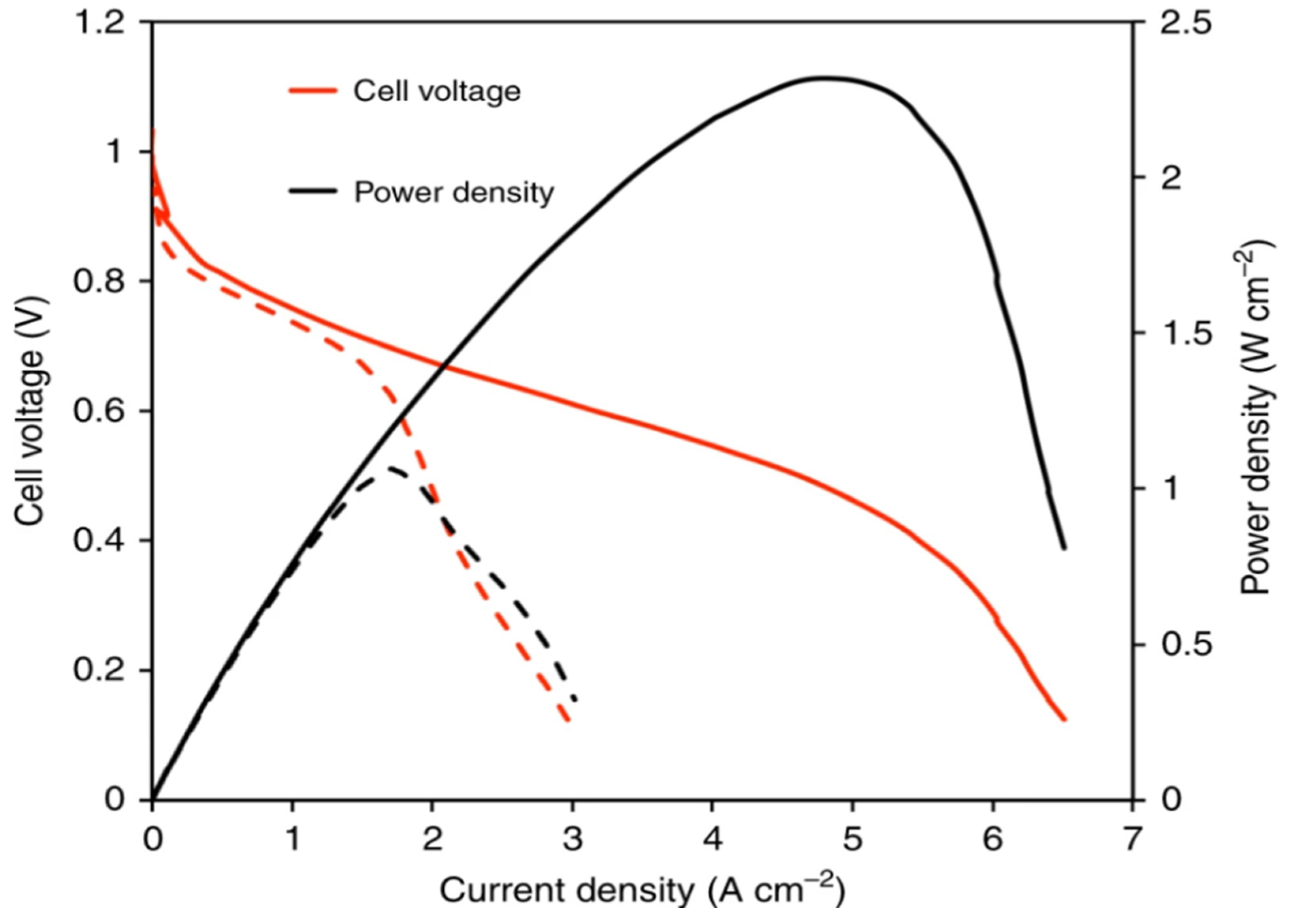

The polarization curve (voltage versus current curve) for reference conditions in Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells is shown in

Figure 9 (Ramírez-Cruzado et al., 2020). The current for the yellow curve at the bottom which represents increasing values is shown and the green curve has decreasing values for current. Each data point has error bars corresponding to three repetitions of the measurement.

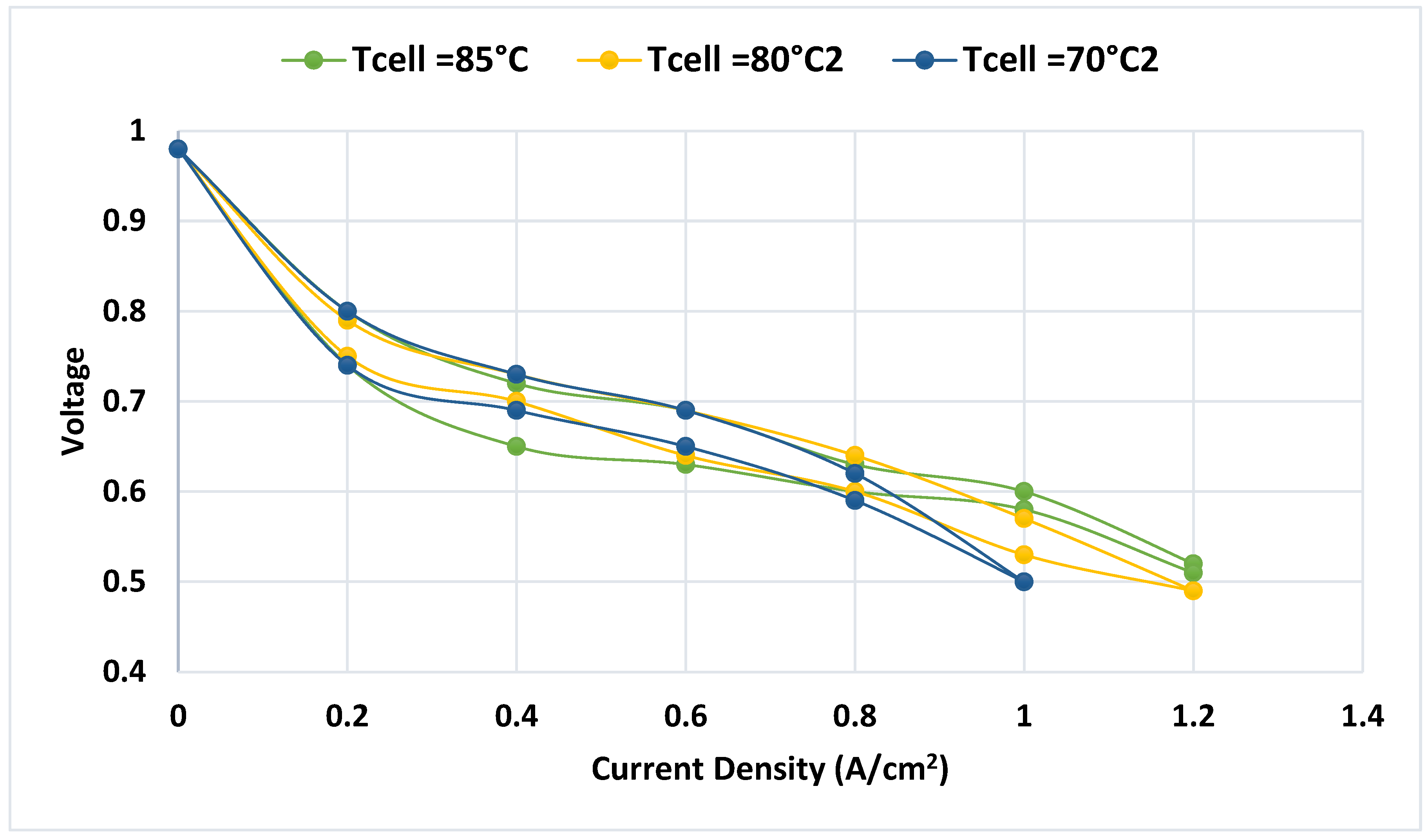

Figure 10 displays the polarization curve for temperature tests, showing voltage vs. current density (Ramírez-Cruzado et al., 2020). This graph illustrates the forward curve (increasing current) at the bottom and the backward curve (decreasing current) at the top.

Figure 11 presents the performance curve, including efficiency, current density, and power output of the PEM fuel cells (Ramírez-Cruzado et al., 2020). This graph provides critical insight into the operational characteristics of PEFCs, which are essential for further enhancing their performance. Although PEFCs could be a game changer for clean energy technologies, further exploration in enhancing the efficiency, solving the CO contamination issue, and developing substitute materials is needed to realize their full promise.

4.3. Alkaline Fuel Cell (AFC)

Alkaline Fuel Cells (AFCs) use an alkaline electrolyte, commonly potassium hydroxide, to transform hydrogen and oxygen into heat, electricity, and water. For the transportation sector, AFCs provided remarkable power and definitely led the industry. However, in the last 25 years, AFC technology has struggled with carbonation. Use of air as an oxidant causes carbon dioxide from the air to react with potassium hydroxide electrolyte resulting in bad performance (Hamada et al, 2023). Notwithstanding, AFCs continue to compete with proton exchange membrane fuel cells for supremacy given their high power densities and long life spans. AFCs, according to Ariyanfar, Ghadamian, and Roshandel (2011), can achieve industry leading efficiency of 60%, but goes up to 87% when heat and power are combined.

AFCs also have growing attention in other fields due to these attributes, refrigeration, electronic devices, and particularly electric vehicle applications. New catalysts, alternative fuels like ammonia and even exploring these fields have made AFC performance and cost effectiveness advances that promises a competetive edge in the clean energy landscape. These changes make AFCs increasingly important in the remaking of sustainable energy systems.

This review emphasizes the substantial progress AFC technology has made, highlighting ongoing innovations aimed at overcoming key challenges and improving overall performance. The continued research efforts suggest that AFCs will play a vital role in the future of sustainable energy systems, furthering their potential to meet the demands of both industrial and consumer applications.

Table 5 presents a summary of research studies on AFCs, specifically focusing on electrolyte investigations and catalyst advancements. These findings highlight the continued interest and progress in enhancing AFC efficiency and mitigating issues such as carbonation.

Figure 12 provides a detailed diagram of the electrochemical reactions occurring within an AFC. The oxidation reaction (2H

2 + 4OH⁻ → 4H

2O + 4e⁻) at the anode generates electrons, which travel through the external circuit to the cathode. At the cathode, these electrons participate in a reduction reaction with water molecules (O

2 + 2H

2O + 4e⁻ → 4OH⁻) to produce hydroxide ions, completing the fuel cell’s operation.

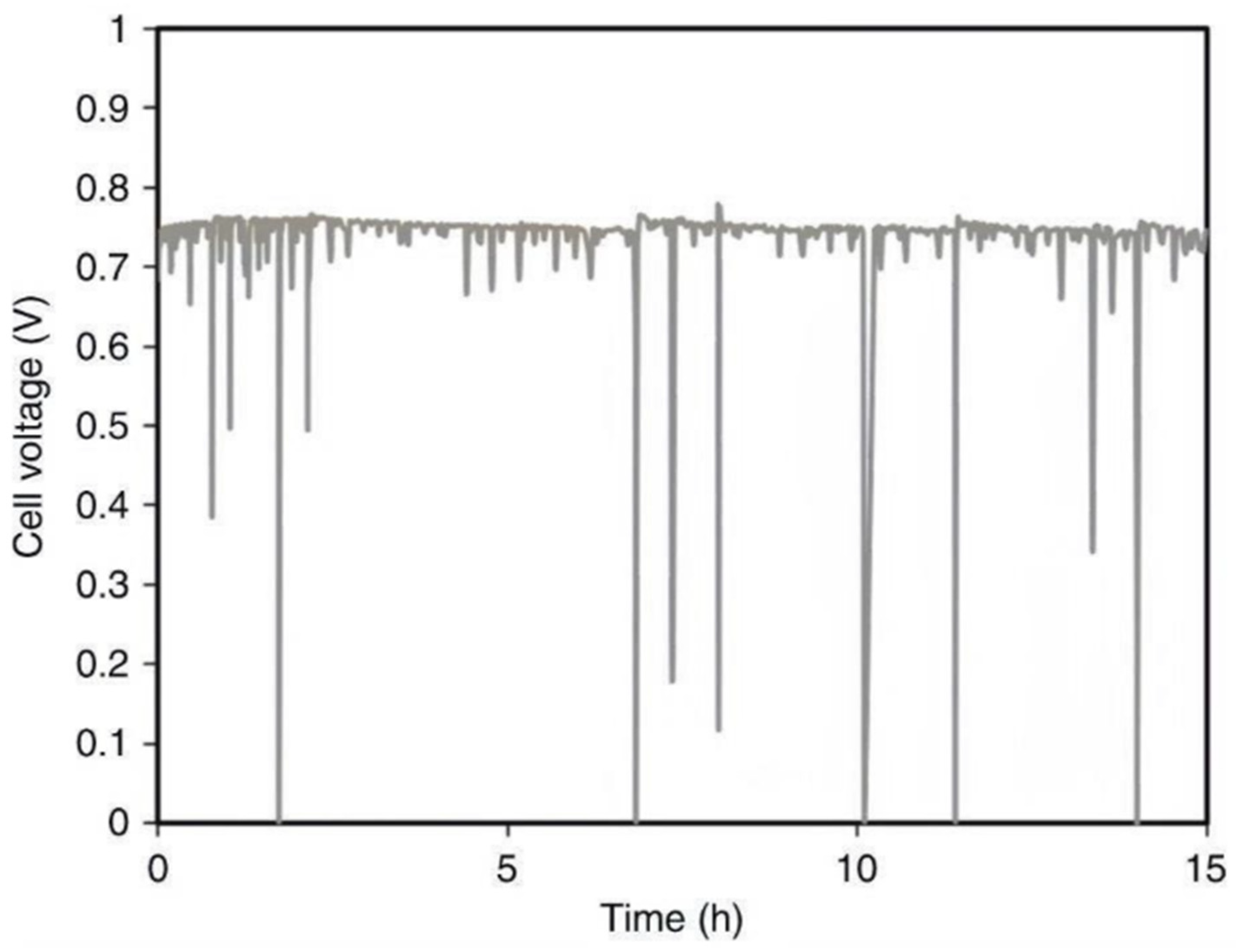

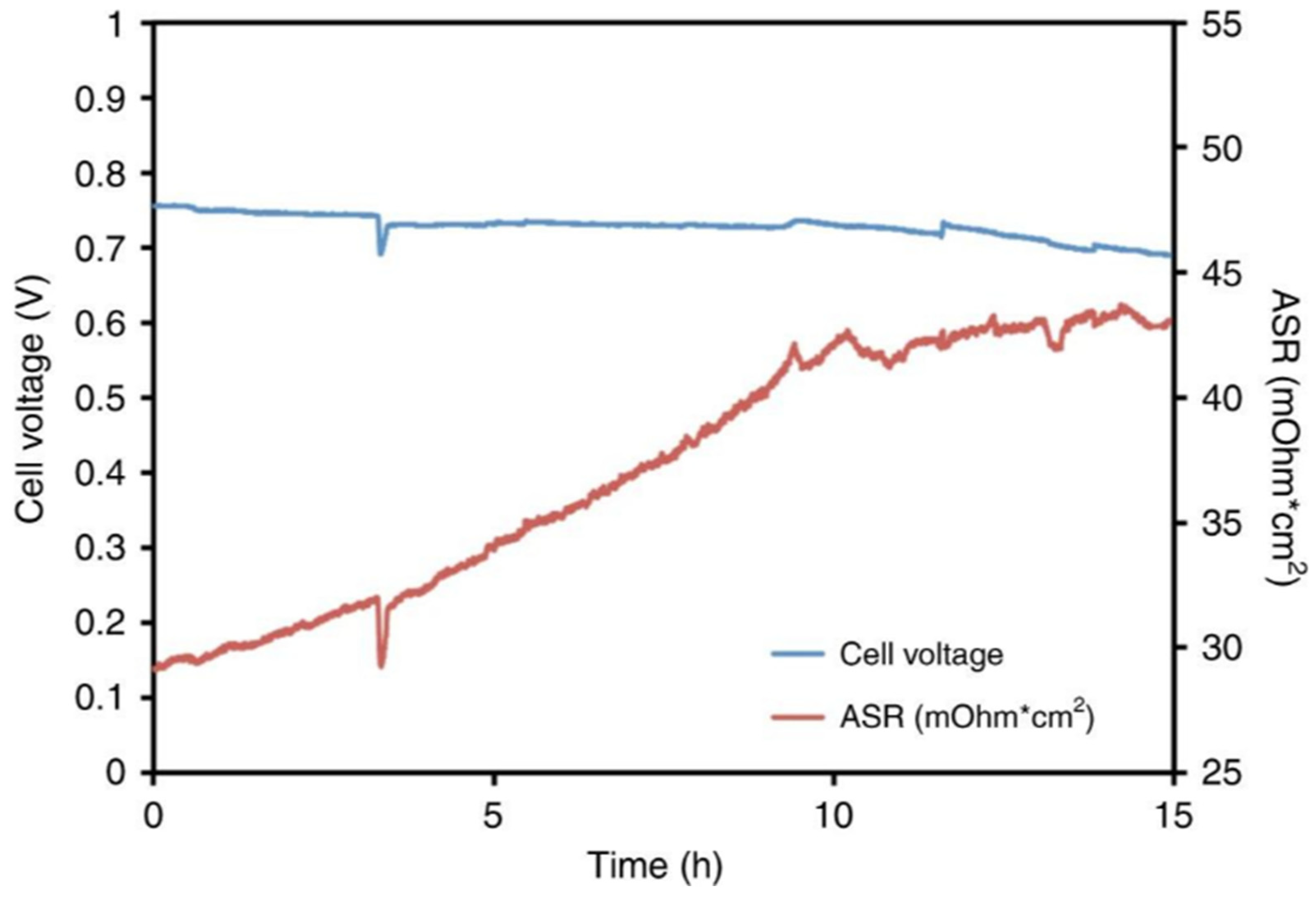

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 illustrate the cell stability under varying anode/cathode dew points.

Figure 13 depicts the stability under relatively high dew points of 55/60 °C, while

Figure 14 shows optimized conditions of 53/55 °C. These tests, presented by Peng et al. (2020), involve measuring cell voltage and area-specific resistance (ASR), with data recorded from cells using a PtRu/C anode and Pt/C cathode. The tests assessed the performance of an AFC under specific operating conditions, such as a cell temperature of 60°C and H

2/air flow rates of 1.0 L/min. This research helps inform the optimal environmental conditions for AFC performance.

The stability of the cells with respect to anode/cathode dew points is shown in figures 13 and 14.

Figure 13 shows the stability at dew points of 55/60 °C and is relatively high, while figure 14 shows optimized conditions of 53/55 °C. These tests are presented in Peng et al. (2020), where the cell voltage and area specific resistance (ASR) were recorded from the cells having a PtRu/C anode and Pt/C cathode. The tests were performed to analyze the Allied Fuel Cell (AFC) performance at given operating parameters of cell temperature of 60 degrees Celsius and H2/air flow rate of 1.0 L/min. This work contributes to establish the optimal environmental conditions of AFC operation. The history of AFCs is long, and most notably in their use in space missions. Originally, they were developed to give reliable power to the Apollo spacecraft, today AFCs still find service in space missions such as supplying power to the Space Shuttle Orbiter (Wagner and Kohnke, 2020). These cells are known for their excellent performance, especially in terms of active oxygen electrode kinetics and their ability to work at elevated temperatures and high pressures.

The performance metrics in both H2/O2 and H2/Air reactions are illustrated in

Figure 15 that presents the Anion-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (AMFC) with 8% PTFE catalyst at the anode and 20% PTFE gas diffusion layer at the cathode. The curves show performance with varying flow rates and operational parameters which yield valuable data for AFC system optimization.

Most attention in recent years has shifted towards the land-based application of the AFCs where these fuel cells are more attractive for remote power generation due to the inexpensive components that operate close to ambient pressure and temperature using air as an oxidizer. On the other hand, these components need to have cost-effective pricing to adequately compete in the consumer and industrial markets (Sokhi et al. 2022). The feasibility of the AFC in mass-market transportation is still unclear because of the never-ending problem of CO2 induced electrolyte poisoning that needs to be regulated and mitigated properly (Vidakovic-Koch, 2016).

The implementation of carbon-based porous electrodes is an example of an advanced AFC technology that has significantly reduced costs and improved performance. As the technology continues to develop, it is metamorphosing for new applications and economic needs. This transforms AFCs to be competitive for the future of clean energy solutions.

4.4. Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cell (PAFC)

Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cells (PAFCs) use liquid phosphoric acid (H3PO4) as an electrolyte, and have emerged as the leading techniques in fuel cell commercialization. These fuel cells were first commercialized due to the notable mosaic in performance, stability, and cost effectiveness achieved during the 1970s (Gallagher et al., 2008). These cells comprise carbon paper electrodes that are plated with platinum catalyst particles and are set in a silicon carbide matrix which is immersed in pure or highly concentrated phosphoric acid. PAFCs operate between temperatures of 150°C and 210°C, although they perform best between 150°C and 200°C.

The electrochemical reactions in PAFCs include the anode reaction:

and the cathode reaction:

Despite being less efficient in energy generation compared to other fuel cell types, PAFCs have the advantage of being resistant to carbon monoxide poisoning, making them ideal for certain applications. Operating at approximately 180°C, these cells can achieve overall efficiencies exceeding 80% when used for cogeneration, where process heat is utilized. PAFCs are commonly deployed in large vehicles such as buses and in stationary power generators, with typical output ranges from 100 to 400 kW (N. H. Behling, 2013).

Leading producers of PAFC technology include Doosan Fuel Cell America Inc. (formerly Clear Edge Power & UTC Power) and Fuji Electric, which have been at the forefront of PAFC development and commercialization.

Table 7.

Summary of Research on Phosphoric Acid and Solid Acid Fuel Cells.

Table 7.

Summary of Research on Phosphoric Acid and Solid Acid Fuel Cells.

| Author |

Type of Investigation |

Electrolyte |

Findings |

| (Cr- et al., 1983) |

New Applications for PAFCs |

Phosphoric Acid |

Explored potential applications of PAFCs, including their use in large diesel locomotives, highlighting the opportunity to displace significant petroleum usage. |

| (Tanni et al., 2013) |

Dynamic Modeling of PAFC and Power Conditioning System |

Phosphoric Acid |

Developed a dynamic model of a 700W PAFC system using MATLAB/Simulink, analyzing cell output voltages, losses, and AC output via inverter simulation. |

| (Tanni et al., 2013) |

Dynamic Modeling of PAFC and Power Conditioning System |

Phosphoric Acid |

Presented a dynamic model of a PAFC system with power electronics, simulating cell output voltages, losses, and AC output, facilitating performance analysis under varying inputs. |

| (Afroze et al., 2023) |

Solid Acid Proton Conductors |

CsH2PO4

|

Demonstrated that solid acids like CsH2PO4 exhibit high proton conductivity at elevated temperatures, making them suitable for fuel cell applications. |

| (Z. Zhang et al., 2023) |

Electrode Design for Enhanced Performance |

Phosphoric Acid |

Introduced an electrode architecture with fibrous networks to optimize phosphoric acid distribution, achieving a 28% increase in maximum power density compared to conventional designs. |

| Lohmann et al., 2017 |

Advanced Electrodes for Solid Acid Fuel Cells |

CsH2PO4

|

Developed stable, high-performance electrodes with minimized catalyst loading for solid acid fuel cells, enhancing efficiency and durability. |

| (Papandrew et al., 2011) |

Advanced Electrodes for Solid Acid Fuel Cells |

CsH2PO4

|

Investigated platinum deposition on CsH2PO4 for solid acid fuel cells, revealing short-range structure and interactions with the electrolyte. |

The phosphoric acid fuel cell operates through a series of electrochemical reactions as shown in

Figure 16, with hydrogen gas being oxidized at the anode and oxygen being reduced at the cathode to produce water.

Although the basic cell design of PAFCs has seen limited changes, significant advancements have been made in terms of improving cell stability, lifespan, and reducing component costs. Companies like UTC Fuel Cells have made concerted efforts to enhance these attributes, although further innovations are still necessary to improve power density and cost efficiency for PAFCs to compete economically with alternative energy sources.

Historically, the introduction of carbon black and graphite as materials for cell construction in the late 1960s replaced the more expensive gold-plated tantalum hardware. These new materials provided greater stability, and the use of high-surface-area graphite allowed for a substantial reduction in platinum loading while maintaining electrode performance. Despite progress, there are still hurdles to overcome including platinum dissolution and carbon corrosion occurring at cell voltages over 0.8V.

The creation of PTFE bounded porous electrodes in combination with platinum black in the mid 1960s anchored PAFC design. Platinum loading was about 9mg Pt/cm² at the start, but efficiency advancements have been made over time and the requirement has been reduced dramatically. For instance, modern electrodes use about 0.10mg Pt/cm² at the anode and 0.50mg Pt/cm² at the cathode.

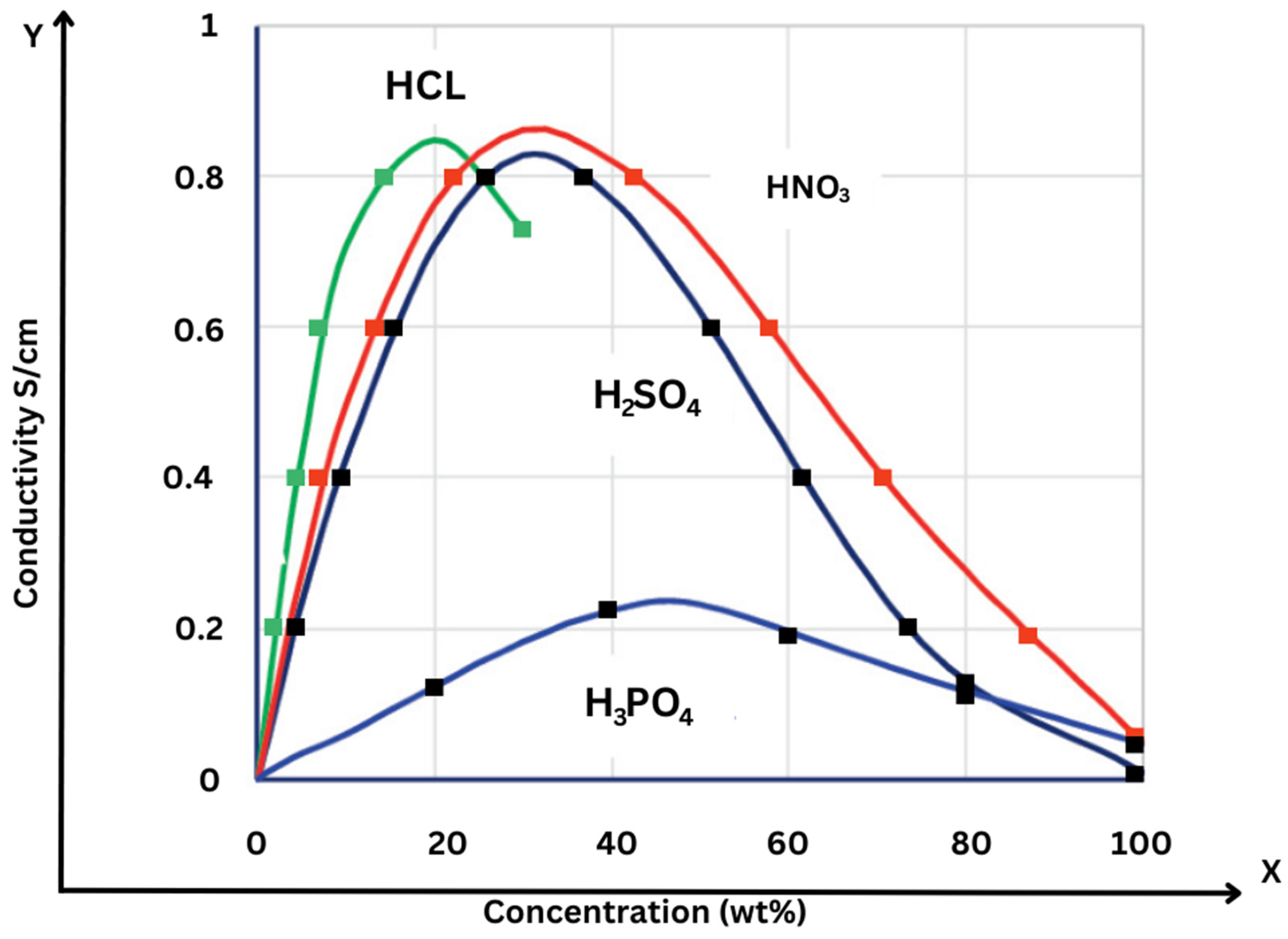

Conductivity of different acids such as HCl, HNO3, H2SO4 and H

3PO

4 affects the efficacy of PAFCs, as seen in

Figure 17 which shows the way the conductivity of these acids changes with concentration. HCl and HNO3 have a conductivity maxima of roughly 0.8 S/cm at around 20-30wt%, while H

3PO

4 has a maximum of 0.2 S/cm at a concentration of 30%. In order to optimize the efficacy of PAFCs, this is essential because the conductivity of the electrolyte directly impacts the performance of the cell.

Current research targets the operating temperature and concentration of phosphoric acid to over 200°C (392°F) with 100% H3PO4 acid concentration. This approach was demonstrated by UTC Fuel Cells and serves to improve system efficiency while also increasing compatibility with hydrocarbon reformers.

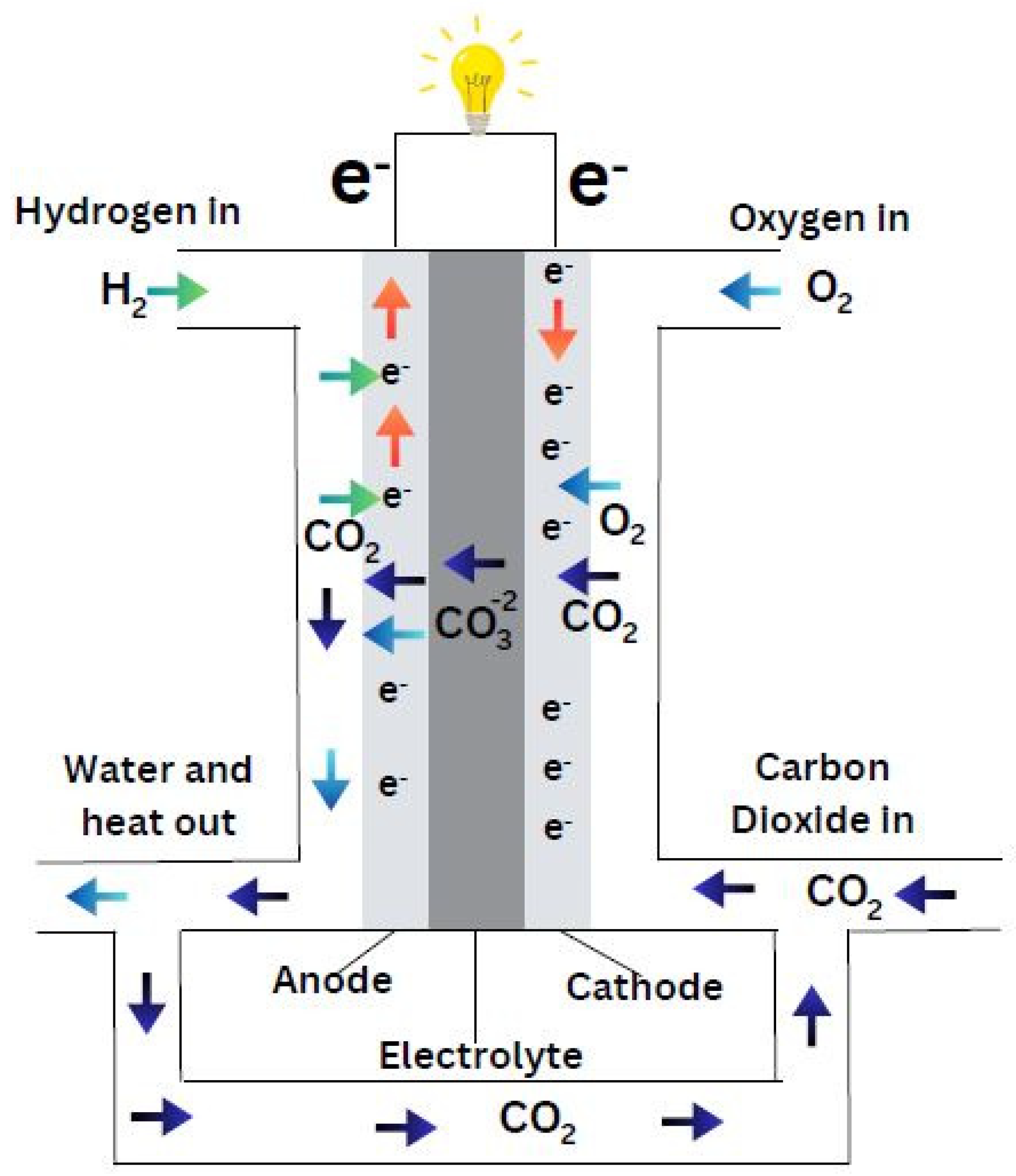

4.5. Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell (MCFC)

A Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell (MCFC) has a molten carbonate salt mixture as an electrolyte that is stored in a beta-alumina solid electrolyte (BASE) ceramic matrix. This matrix is porous and chemically inert to MCFC. The fuel cell temperature currently ranges from 550–650°C but may reach up to 600–700°C in the near future (Venkataraman & Farooque, 2009). These high-temperature fuel cells were specifically designed for large-scale applications such as coal-, gas-, and biogas-fired power plants, as well as military, industrial, and utility sectors (Fuller & Gallagher, 2008).

Figure 18 illustrates the structure of a typical molten carbonate fuel cell.

One of the key advantages of MCFCs is their resistance to carbon monoxide poisoning, making them highly effective when using fuels that contain carbon monoxide. Additionally, MCFCs can efficiently extract hydrogen from a variety of fuels, either via internal or external reformers. This capability makes them particularly attractive for use with coal-based fuels. The cells also benefit from the use of nickel catalysts, which are not only less expensive than platinum but are also more suitable for the operating conditions of MCFCs. As a result, these fuel cells have found widespread use in medium-capacity stationary power generating plants, including large combined heat and power (CHP) and combined cooling and power (CCP) systems, as well as in numerous megawatt-scale fuel cell power plants.

In recent years, research efforts have concentrated on enhancing the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of MCFCs by developing new catalysts and exploring alternative fuels such as biomass gasification (Ferguson & Tarrant, 2021). The high operating temperatures of MCFCs facilitate the electrochemical oxidation and reduction processes, eliminating the need for noble metal catalysts, which enhances fuel flexibility and overall system efficiency. However, this high-temperature operation also presents challenges, particularly regarding the longevity and corrosion resistance of the cell components, especially in the aggressive environment of the molten carbonate electrolyte.

Table 8 provides a summary of recent research findings on MCFCs, including key studies that highlight advancements in various aspects of fuel cell technology. As a case in point, Ferguson et al. (2021) performed a techno-economic evaluation of MCFCs for post-combustion CO

2 capture and managed to achieve 92% CO

2 capture accompanied with 42% additional electricity generation, albeit with a slight thermal efficiency loss of 2.6% relative to an Amine scrubber’s performance. In the same vein, Bove et al. (2021) remarked that MCFCs can obtain energy efficiencies up to 60%, as well as total fuel efficiencies above 80% in a cogeneration application.

The other significant area of MCFC research is the design of internal and external reforming processes. There are two types of MCFCs in regard to the position of the reforming catalyst: internal reforming (IR) and external reforming (ER). In internal reforming MCFCs, the reforming catalyst is positioned close to the anode, which helps in converting methane (CH4) and water (H2O) into hydrogen (H2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Conversely, ER MCFCs utilize hydrogen and carbon monoxide that are produced outside the system. On the contrary, high-temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) with or without a catalyst can do direct oxidation of carbon monoxide and methane, thus having greater freedom in fuel application (Ferguson & Tarrant, 2021).

Figure 19 illustrates the polarization curve of a molten carbonate fuel cell which is integrated with other components, showing the operational features of the cell (Ghorbani et al., 2022). The power output of MCFC stacks and single cells has increased remarkably over the years. The design power density of the cell has increased from 10mW/cm² to approximately 150mW/cm², and some MCFC stacks have cell areas up to 1 m² (Ferguson & Tarrant, 2021). These developments are of great importance towards the higher efficiency and scalability of MCFCs for wide-scale energy production.

4.6. Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC)

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) rely on a solid oxide material as the electrolyte and operate efficiently at high temperatures. As Ormerod (2002) explains, SOFCs typically function at temperatures ranging from 550 to 650°C, with some systems reaching temperatures close to 700°C. These fuel cells are particularly advantageous for coal-based fuels because they can extract hydrogen from a variety of fuels through both internal and external reforming processes. Additionally, SOFCs are less susceptible to carbon monoxide poisoning compared to low-temperature fuel cells, making them a promising solution for broader fuel applications. The use of nickel as a catalyst, instead of more expensive platinum, further enhances the cost-effectiveness of SOFCs while maintaining solid performance.

SOFCs have a diverse range of applications, including stationary power generation, which can range from 100 W to 2 MW, as well as auxiliary power units for vehicles. The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Fossil Energy has dedicated efforts to the research, development, and deployment of SOFCs that run on gasified solid hydrocarbons (Ormerod, 2003). In their comprehensive review, Bhattacharyya and Raghunathan Rengaswamy (2009) identify several critical objectives for SOFC programs, such as reducing the cost of the stack to $225/kW and the overall system cost to $900/kW. They also emphasize the importance of demonstrating that SOFCs can maintain a performance degradation rate of less than 0.2% per 1,000 hours over an impressive 40,000-hour lifespan, while achieving efficiency levels exceeding 60%, excluding carbon capture and storage technologies. These goals underscore the tremendous potential of SOFCs to revolutionize energy systems.

Table 9 presents a summary of the advancements and investigations in the field of SOFCs, highlighting the diversity of approaches and findings from various researchers.

Notably, the Korea Institute of Energy Research (KIER) developed a catalyst coating process that significantly improves SOFC performance in just four minutes, a breakthrough with major implications for efficiency and scalability. Other advancements, such as the use of La₀.₆Sr₀.4CoO3 (LSC) as an electrolyte material, have demonstrated up to 10 times higher conductivity compared to traditional materials, enhancing catalytic activity in SOFC mode (Chemistry Europe). These findings are crucial as they point towards materials and technologies that could lead to both improved performance and cost-effectiveness.

Stambouli and Traversa (2002) emphasize the importance of developing novel catalysts and exploring alternative fuels like biomass gasification to enhance SOFC efficiency. They argue that SOFCs integrated with large Coal gasification facilities have the potential to attain remarkable efficiency with almost total capture of CO2 and decreased water usage. According to the study, the two main types of SOFCs, tubular and planar, have their respective benefits and drawbacks. Tubular SOFCs, which function at relatively higher temperatures ranging from 900-1000 degrees Celsius, are simpler to fabricate; however, they have higher resistive losses. Planar SOFCs, on the other hand, operate at lower temperatures, generally under 800 degrees Celsius, and can utilize less expensive and more conventional materials. Both types, however, are substantial contributors to the advancement of SOFC technologies.

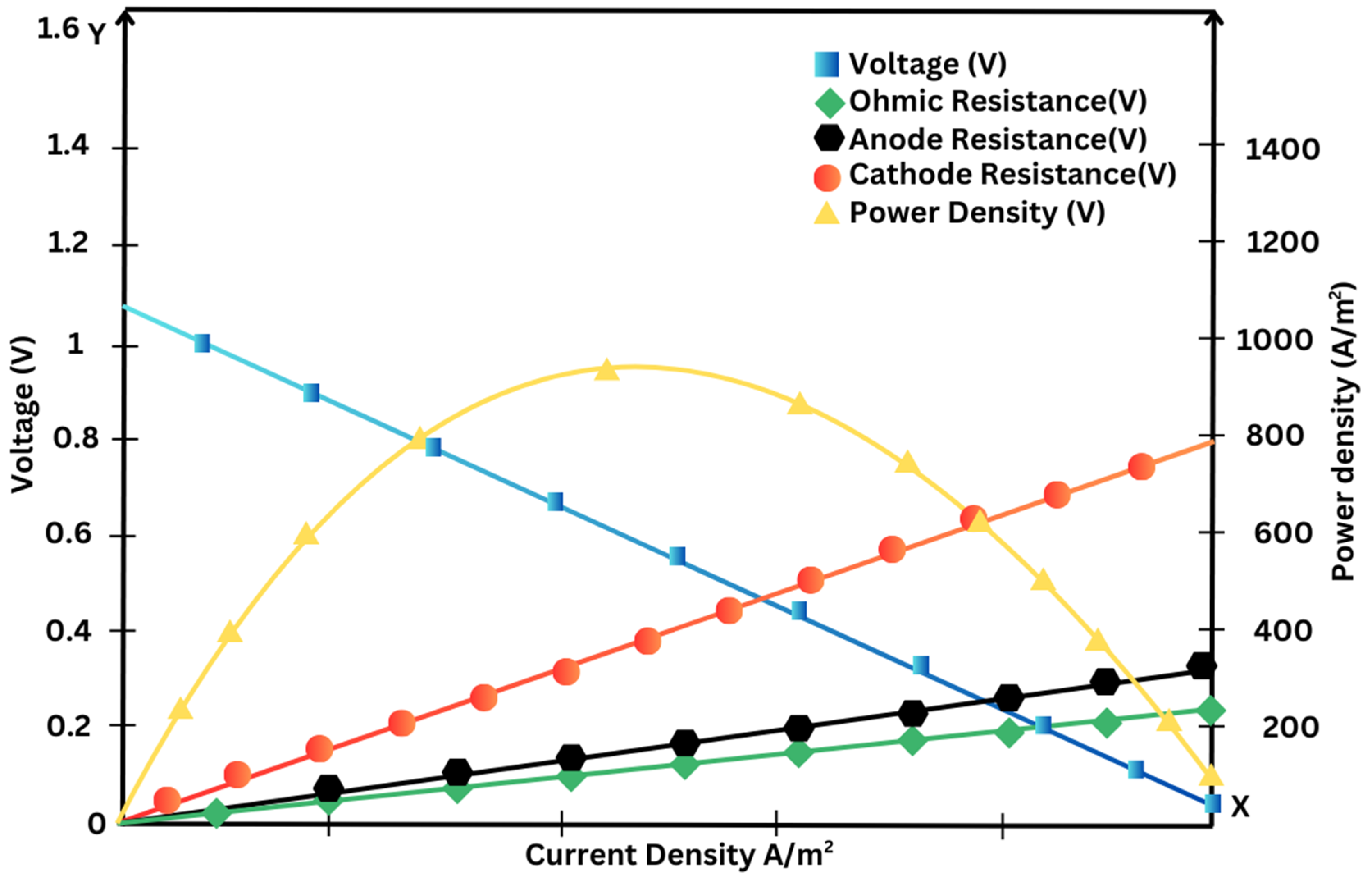

As depicted in

Figure 20, a solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) operates fundamentally on the oxidation reaction at the anode, where oxygen molecules (O

2) are oxidized to form oxygen ions (O²⁻) that gets reduced through a cathode reaction where hydrogen ions (H²) react with the oxygen ions formed to release water (H²O) at the cathode. This part of SOFC is critical for hydrogen electrochemical energy conversion.

In addition, SOFC performance characteristics with respect to internal resistance and thermal efficiency can be appreciated with the V-I polarization curve which is shown in

Figure 21. The voltage (V) is plotted against the current (I) at different operating points of the SOFC. From this curve, one can understand the effect of internal resistance and temperature on efficiency and the operating conditions that give the optimum SOFC performance. The curve also indicates the available different load conditions on the SOFC and how they are best utilized in terms of design and operational parameters.

The SOFCs become economically efficient and performing well due to its planar design. The US DOE Solid-State Energy Conversion Alliance has made enhancements on this technology since 2000 which boosts its power density and lowers its anticipated price (Mahato et al. 2015). This allows for an attractive use of the planar SOFCs for stationary as well as mobile auxiliary power units. In addition, the versatility of SOFCs is illustrated with the emergence of the direct methane oxidation fuel cell which expands the potential uses of this technology.

5. Fuel Cells with Renewable Energy Systems

Fuel cells and renewable energy systems can be combined to enhance energy systems integration. This section discusses how fuel cells can work with other resources like biomass, solar, and wind energy. Hybrid systems aim to be environmentally friendly by taking advantage of the diverse and fluctuating nature of these resources. These systems are integrated to optimize efficiency and reduce non-renewable energy resource use.

A renewable energy system is usually configured as a hybrid energy system that integrates two or more sources of renewable energy to supply electric power. These systems may be classified into two types based on design and operation: stand-alone and grid-connected.

Table 10 classifies the renewable energy systems according to their capacity for generation:

5.1. Stand-Alone Systems

A stand-alone system is also called an autonomous system. The system is in charge of meeting demand at all times and is isolated from the grid network. Because of the resources used, this kind of system is linked to reliability issues (Bukar et al., 2017). Because of this, Technically and financially, the technique is only feasible for off-grid applications when It is challenging to expand the grid to a specific location (Halabi & Mekhilef, 2018).

5.2. Grid Connected Systems

Grid-connected systems (GCS) are freestanding RE systems that are linked to sizable independent networks, usually the public utility grid (Y. Wang et al., 2018). Extra energy generated by the stand-alone renewable energy system is fed into the grid through GCS. Similarly, the grid is used to make up for any deficit in generation.

5.3. Fuel Cells in Renewable Energy Systems

The complexity of stand-alone renewable energy systems (RESs) has been the subject of extensive research focusing on integrating fuel cells.

Table 11.

Summary of Fuel Cell Systems and Findings from Various Studies.

Table 11.

Summary of Fuel Cell Systems and Findings from Various Studies.

| Author |

Type of fuel cell |

Findings |

References |

| Ghenai et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

Simulation results revealed the best hybrid design; it obtained 73% of the energy from solar PV, 3% from a DG, and 24% from FCs. |

(Ghenai & Bettayeb, 2019) |

| Temiz et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

The simulation showed a net present cost (NPC) of $581,733 and an energy (COE) cost of $0.612/kWh. |

(Temiz & Javani, 2020) |

| Chang et al. |

PEM fuel cell |

The hybrid design utilizing the lithium-ion battery yielded an efficiency of 81.24% as opposed to the battery-free setup's 70.22% efficiency. |

(Chang et al., 2019) |

| Duman et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

A 10-kW wind turbine, 57.6 kW PV array, 3 kW DG, 20 kW FC, 25 kW electrolyzer, 72 kW converter, and a 20 kg hydrogen tank were the ideal energy system size. It had the lowest NPC and COE ($253,590 and 0.282 $/kWh, respectively) out of all the configurations examined. |

(Duman & Güler, 2018) |

| Al-sharafi et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

With an NPC of $100,486 and a COE of 1.608 $/kWh, their calculations revealed the ideal PV/FC energy system architecture, which consists of a 2 kW FC, 6 kW PV array, 7 kg hydrogen tank, 5 kW electrolyzer, and 2 kW converter. |

(Al-Sharafi et al., 2017) |

| Gokçek et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

An 8.78 kW PV array, a 1 kW FC, four batteries, a 2 kW electrolyzer, and a 0.4 kg hydrogen tank make up the optimal configuration. The energy system's COE and NPC were calculated to be $102,323 and 1.351 $/kWh, respectively. |

(Gökçek & Kale, 2018) |

| Li |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

the best PV/battery/FC system had a total NPC of $7,815,223 and a COE of $1.553/kWh. |

(C. Li, 2019) |

| Cozzolino et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

The simulation resulted in a configuration with a COE of 0.522 €/kWh. |

(Cozzolino et al., 2016) |

| Luta et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

An ideal system configuration of a 400 kW electrolyzer, a 1351 kW PV generator, a 185-kW inverter, an 80 kW FC, an 80 kg hydrogen tank, and an array of 2048 strings of 16 supercapacitors was achieved. The system's net present cost (NPC) was $26,626,630, and its energy (COE) cost was 4.78 dollars per kWh. |

(Luta & Raji, 2019) |

| Rezk et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

The ideal setup included 96 batteries, a 40 kW FC, a 50 kg hydrogen tank, a 200 kW PV array, a 50-kW converter, a 110 kW electrolyzer and its NPC and COE were determined to be $500,823 and 0.126/kWh, respectively. |

(Rezk et al., 2020) |

| Herdem et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

Even with an increase in PV peak power capacity, the load fraction factor does not rise above a specific threshold. |

(Herdem et al., 2020) |

| Baldi et al. |

Solid oxide and PEM fuel cells |

Pure H2 production from the fuel cell anode off-gas with a purification unit might address peak electricity demands. At the same time, solid oxide fuel cells could handle the system's baseload. With the help of batteries and H2, this hybrid energy storage system successfully lowered peak electricity needs. This method enhanced the average load of the solid oxide FCs and prolonged their lifespan. |

(Baldi et al., 2019) |

| Mudaliyar et al. |

PEM fuel cell |

Microturbines were added to FCs to overcome constraints like poor lifespan and high capital expenditures. They could meet transient and steady-state load requirements on and off the grid. |

(Mudaliyar et al., 2017) |

| Asghari et al. |

Solid oxide fuel cell |

The combination improved system efficiency by enabling the system to adjust to household dynamic loads and utilize solid oxide FC waste heat for further power generation or cooling. |

(Asghari & Brouwer, 2019) |

| Agrawal et al. |

PEM fuel cell |

By regulating the temperature of the FC stack, the Fuzzy logic control increased FC energy generation and lifespan. At the same time, the ANNc assisted in achieving the maximum power point of solar PV modules. |

(Agrawal et al., 2018) |

| Taleb et al. |

Polymer exchange membrane surface FC |

The study suggested a passive hybrid design to increase system performance and reliability with different load demands without extra power management devices. |

(Ait Hammou Taleb et al., 2018) |

| Yang et al. |

Solid oxide fuel cell |

A time delay control device was implemented to enable solid oxide fuel cells to follow loads, resulting in better adaptability to changes in load without compromising fuel supply. |

(J. Yang et al., 2017) |

| Wu et al. |

Solid oxide fuel cell |

An ideal fault-tolerant control strategy for solid oxide fuel cells was able to maximize cost and efficiency in typical and atypical scenarios. |

(X. Wu & Gao, 2017) |

| Barakat et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

The study quantified excess H2 production from the tidal generator and provided two control strategies for maximizing torque/ampere and minimizing losses. |

(Barakat et al., 2020) |

| Han et al. |

Hydrogen fuel cell |

. In addition to coordinating the hybrid energy sources, the energy management system controlled the temperature of the FC stack to increase FC performance and longevity by applying fuzzy logic and artificial neural network control. |

(Y. Han et al., 2019) |

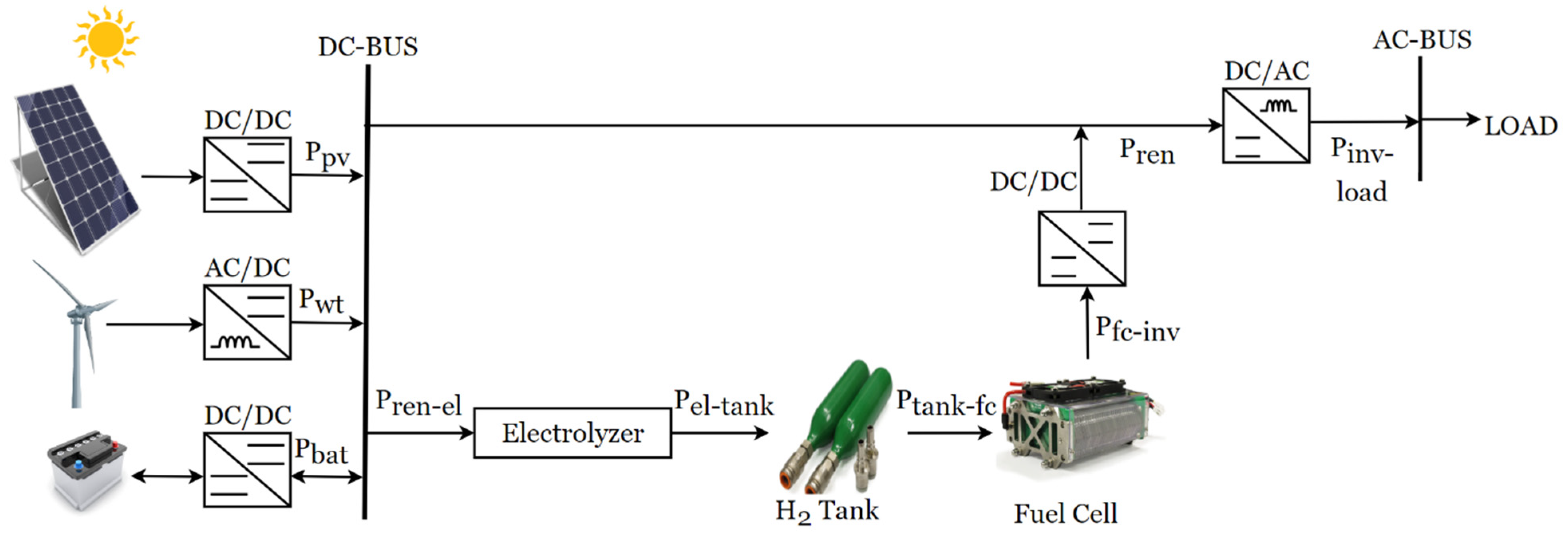

These studies demonstrate the diversity of renewable energy sources and fuel cell systems, each tailored to meet specific load demands based on geographic and climatic conditions. The research emphasizes the importance of economic feasibility in developing sustainable energy solutions. Furthermore, the findings highlight key technological developments aimed at improving system efficiency, such as better load-following capacity and advancements in energy storage and control systems.

The integration of fuel cells into hybrid energy systems has also shown promising potential for improving the reliability and performance of RESs. A typical schematic diagram of a hybrid stand-alone PV-WT-BT integrated with a fuel cell is illustrated in

Figure 22.

6. Applications

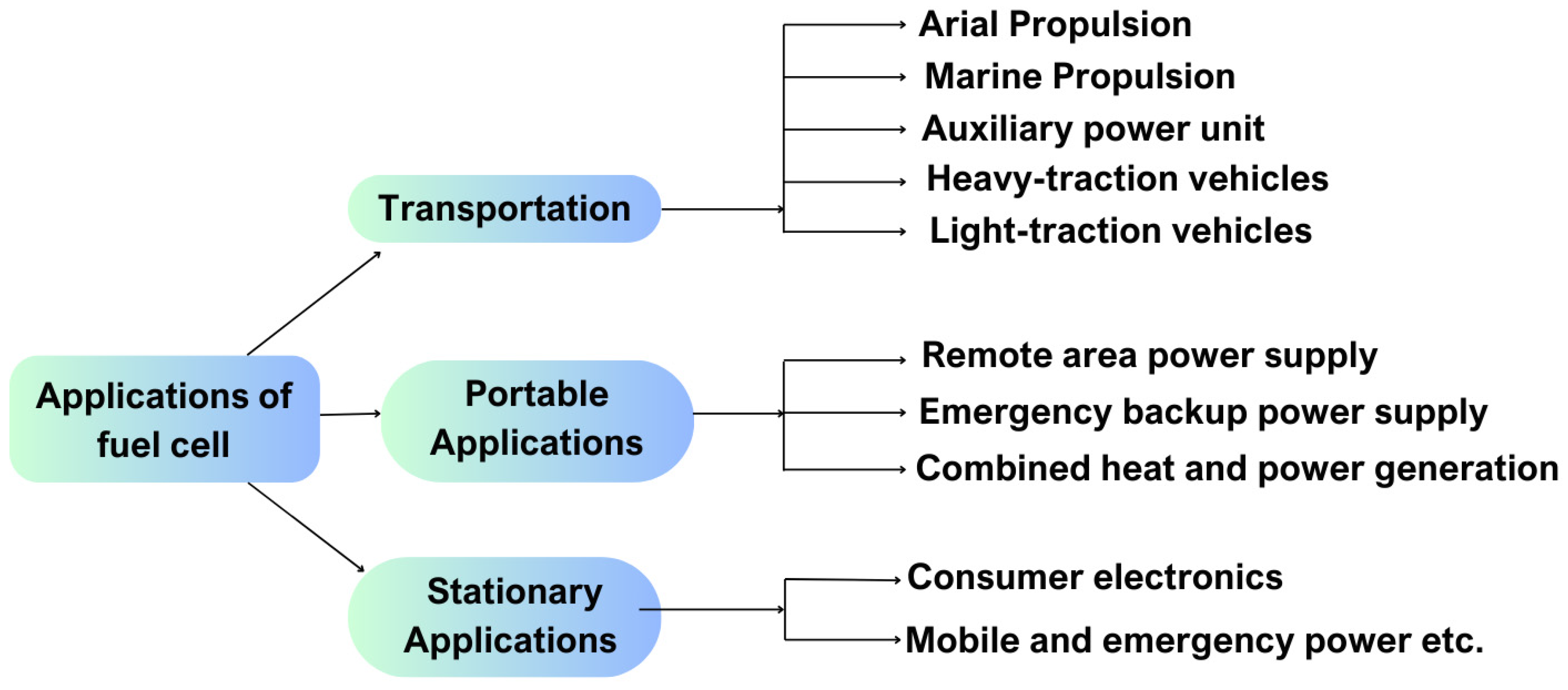

The flexibility, modularity, and variety of these devices is leading to widespread adoption of fuel cells throughout many verticals. These new energy systems are being employed more intensively throughout a diverse range of sectors from scooters to co-generation power plants. Attention is drawn to the increased scope fuel cells have in the transportation industry, electronics, and stationary power generation. The period between 2012 and 2018 saw a vigorously shipped 92% increase in fuel cells (Cigolotti et al., 2021) which signals a high rate of use in many sectors. This rapid expansion has driven many passtrough fuel cell developments in telecommunications backup power, material handling equipment, and airport ground support tools. The stationary fuel cell is expected within the context of competitive international service markets to exceed 5.08 billion dollars by 2030 (Cigolotti et al., 2021). Many nations within the realm of the United States, South Korea, Germany, Japan, and Canada are the ones dominating the development and commercialization of fuel cell technologies that enables further growth and constant change.

The main applications of fuel cells in transportation, stationary, and portable sectors are illustrated in

Figure 23. This figure provides a comprehensive overview of the key areas where fuel cells are making a significant impact, emphasizing their increasing role across multiple industries.

6.1. Transportation

The transportation sector plays a significant role in global greenhouse gas emissions, contributing approximately 19% of the annual total. As a result, the development of clean energy technologies has become an urgent priority (Khalili et al., 2019). The industry is actively exploring alternatives to traditional combustion-based technologies, which rely on fossil fuels to power heat engines. This search for cleaner options is driven by the need to reduce emissions and enhance energy conversion efficiency.

Among the promising solutions, fuel cells stand out. These systems offer the potential for nearly emission-free mobility, without compromising the efficiency of propulsion systems. In fact, fuel cells demonstrate impressive efficiencies, ranging from 53% to 59%, which is nearly twice as high as conventional internal combustion engines (Wipke et al., 2010). As a result, fuel cells are increasingly viewed as an ideal alternative for light-duty passenger vehicles in the future.

Fuel cells offer several advantages, including low maintenance requirements, fuel flexibility, modularity, and the ability to operate statically, all of which contribute to their appeal. However, achieving success in this market requires overcoming several key challenges, such as meeting technological targets, establishing hydrogen infrastructure, and ensuring both durability and cost-effectiveness.

The adoption of fuel cell transportation is steadily gaining momentum. For instance, Japan aims to deploy two million fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) and set up 1,000 hydrogen refueling stations by 2025. So far by September 2020, Japan was at 3,300 FCEVs and everywhere in the country there were only 25 hydrogen refueling stations (Hulvey et al., 2020). These moves indicate the remarkable progress in cell technologies and their ability to transform the world of automotive engineering.

The sector for fuel cells has expanded considerably in the past few years. The shipment of fuel cells has more than doubled between the year of 2016 and 2021. It went from 62,000 to over 130,000 units shipped with an output power of 2.3 gigawatts (GW). Proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells, made from a polymer low and with an ionized membrane, have taken the lead in this industry (Visvanathan et al.,2023). Fuel cells are now being used in airplanes, ships, auxiliary power units (APUs), light traction vehicles (LTVs), and heavy duty fuel cell electric vehicles (H-FCEVs). The continual expansion of fuel cells into new markets demonstrates the innovation possible in fuel cells and the great need for sustainable solutions in transportation.

6.1.1. Aerial Propulsion

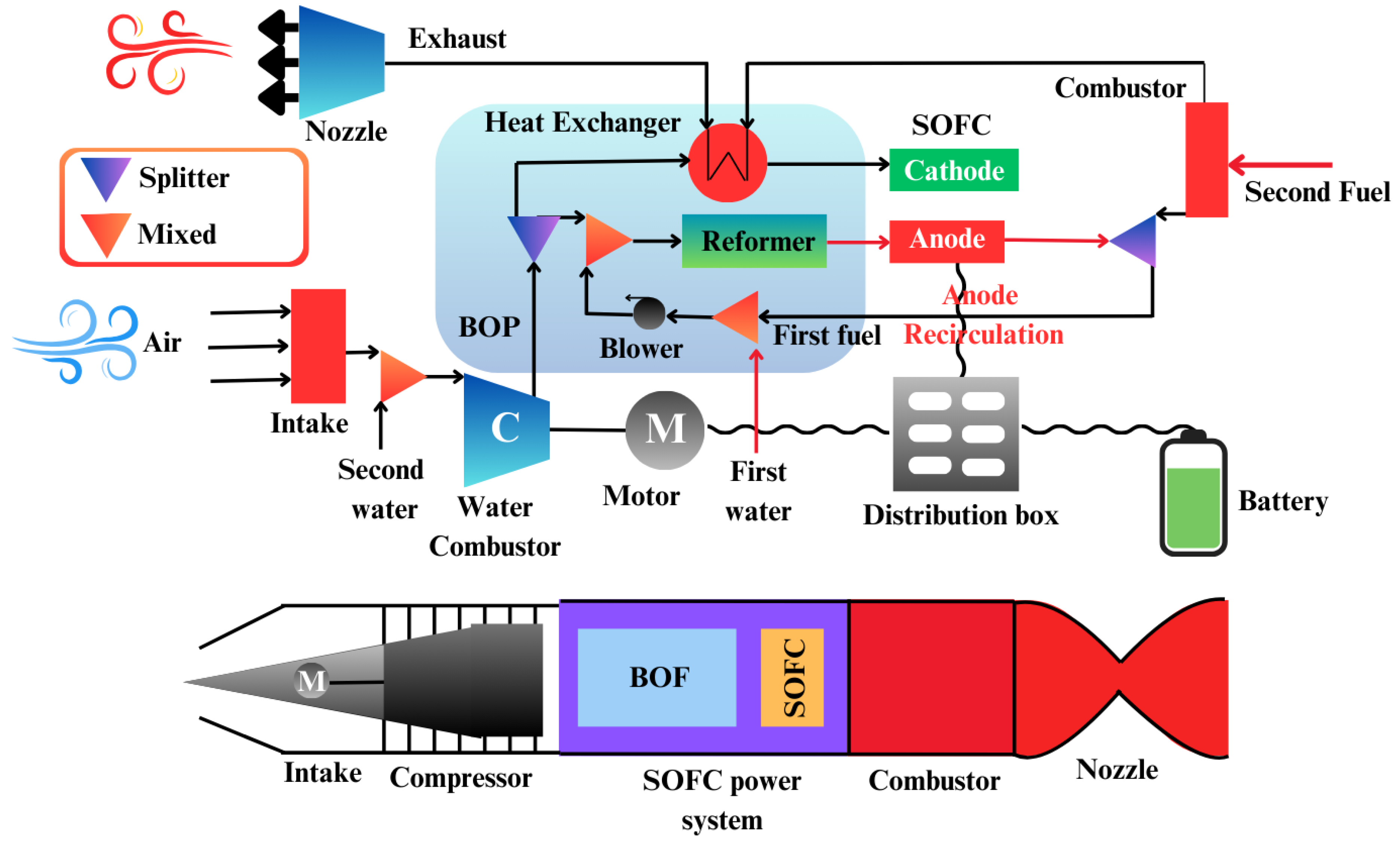

Developments in the fuel cell technology has shown immense promise for the aerospace and aviation sectors within the domain of aerial propulsion systems, specifically in regard to small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). UAVs are considered economical from a dimension and spatial planning prospective and are helpful in a number of disciplines and operations that include tracking, reconnaissance and sometimes, even spying. In order to improve the efficiency of such UAVs, the development of advanced, durable and reliable propulsion systems is necessary. Out of many other technologies, fuel cells stand out in particular with Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs) and some variants of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) being the most common.

Figure 24.

Integrated Jet Engine with SOFC Power System.

Figure 24.

Integrated Jet Engine with SOFC Power System.

Fuel cells hold a significant advantage over traditional battery systems in terms of weight-to-energy ratio, allowing for decreased heat loss and more efficient static operation. While battery-powered UAVs have an endurance limit of about one hour, fuel cell-powered UAVs have significantly greater mission durations due to high energy density and lightweight construction. Compared to combustion engines, these fuel cells integrated into UAVs are easier to maintain and more efficient for small systems, particularly unmanned aerial vehicles where traditional engines are less optimal. For these reasons, fuel cells are perfect for smaller UAVs. Dicks (2012) claims that roughly twenty unmanned aerial vehicles powered by fuel cells have been developed to this point.

A comparative study by Bradley et al. (2009) evaluated various propulsion systems for small-scale UAVs and concluded that a PEMFC system using compressed gaseous hydrogen offered the best potential for both range and endurance. In comparison, other propulsion systems considered included small internal combustion engines, lithium polymer batteries, zinc-air batteries, and propane-based SOFCs.

One innovative development in UAV design is the hybrid fuel cell/battery system, which incorporates onboard hydrogen production. For example, Kim et al. (2011) demonstrated a sodium borohydride-based system that showed superior efficiency in long-endurance flights compared to traditional battery-powered and combustion-based UAVs. For extended high-altitude flights, NASA’s Helios UAV utilized a hybrid propulsion system that combined solar cells, a regenerative fuel cell, and backup batteries. While fuel cells currently cannot meet the high energy and power density requirements of manned military or commercial aircraft, several small-scale manned aircraft experiments have explored the use of hybrid hydrogen PEMFC systems.

Fuel cells have also found applications in high-altitude balloons, with NASA utilizing AFCs and PEMFCs in space missions for decades, particularly in manned space programs. The water produced as a byproduct of these fuel cells provides an additional advantage, as it can be utilized for drinking water and other mission-critical needs. With growing interest in space exploration, fuel cells are again being considered for future space missions, offering the potential for sustainable energy production in the challenging conditions of space (Burke, 2003).

6.1.2. Marine Propulsion

The adoption of fuel cells in the marine sector is rapidly expanding, particularly in auxiliary power units (APUs) on yachts and boats. However, the application of fuel cells for marine propulsion is poised to extend beyond recreational vessels to include cargo ships, ferries, submarines, and various other watercraft. Fuel cells offer several advantages, including efficient static operation, high energy conversion efficiency, and low emissions. Despite these benefits, challenges related to longevity, shock resistance, and the ability to withstand salt air remain obstacles to widespread adoption.

Presently, the marine fuel cell industry is concentrating on three prime technologies: Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs), Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs), and Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells (MCFCs). Perhaps the most significant event in this industry was the first yacht demonstration in Germany in 2003, equipped with a hybrid PEM fuel cell/lead-gel battery system for propulsion, which also served as an auxiliary power source. This milestone was followed by the 2008 debut of the first commercial passenger ship equipped with a hybrid PEM fuel cell/lead-gel battery propulsion system, which was noted for its astonishing doubling of efficiency relative to traditional diesel ships. In 2009, Austria showcased an autonomous hydrogen fuel cell boat that ran on hydrogen created by solar energy and managed to travel longer distances compared to typical battery-operated boats. That was followed by Germany's introduction of the first hydrogen fuel cell-operated ferry in 2011 (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014).

The issue of hydrogen’s low volumetric density has been partially addressed by proposals such as those by Alkaner et al. (2006), who suggested onboard reformation of traditional marine fuels for hydrogen production, making fuel cells a viable option for commercial ships.

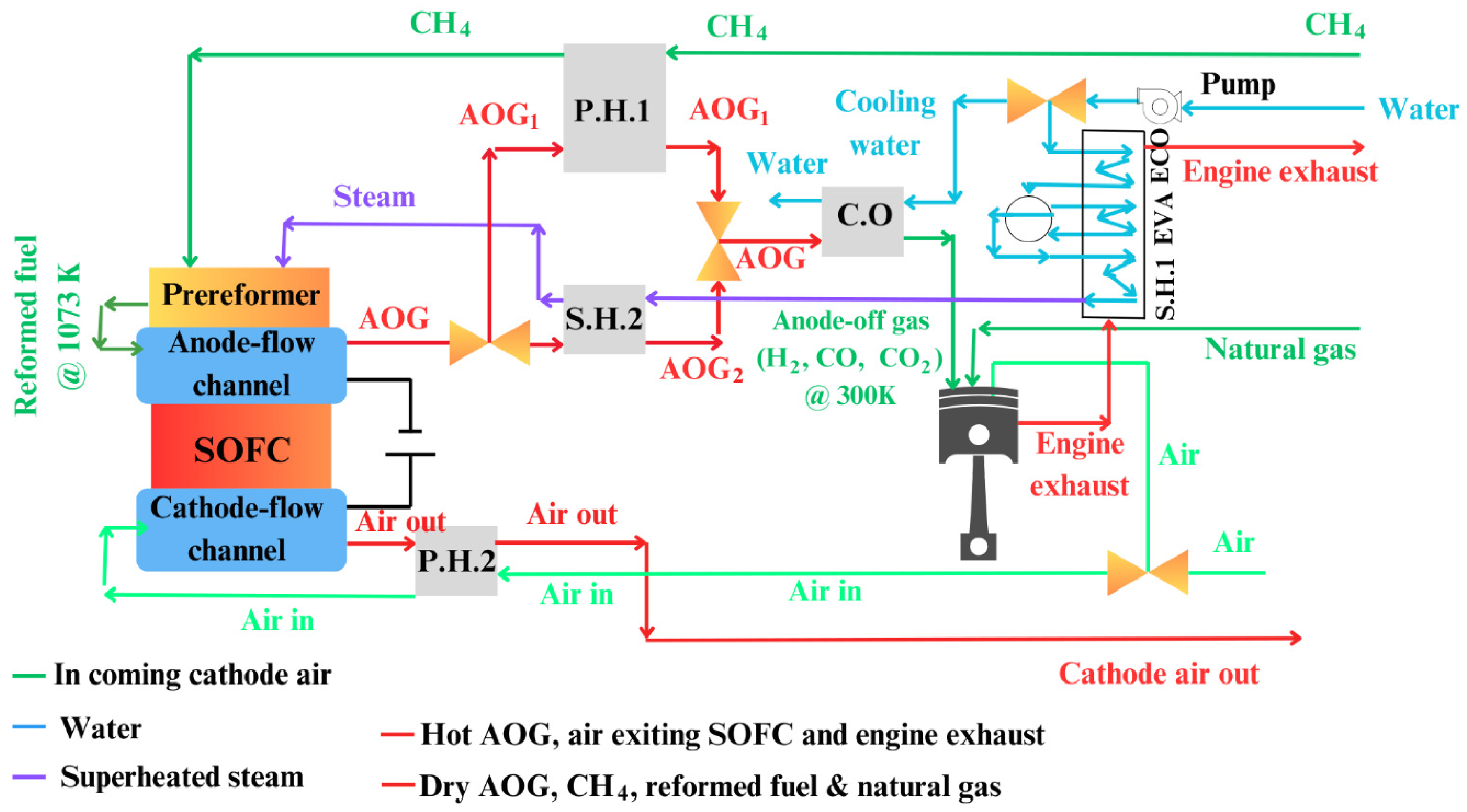

As seen in

Figure 25, which illustrates the proposed system layout of a Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) integrated with an internal combustion engine (ICE) for maritime applications, exergy efficiencies in marine fuel cell systems have been found to be comparable to those of other power arrangements. The system layout incorporates key components such as the preheater (P.H.), cooler (C.O.), superheater (S.H.), evaporator (Evap), and economizer (Eco), all contributing to optimizing performance in marine contexts.

Successful deployments of oxygen/hydrogen fuel cell-powered submarines have demonstrated significant benefits, including enhanced underwater endurance, high efficiency, reduced heat and magnetic signatures, and lower noise levels. These attributes make fuel cell-powered submarines ideal candidates for modern military operations, where undetectability is crucial. As a result, several naval forces—particularly the Italian, Greek, and South Korean fleets—have shown considerable interest in investing in these innovative vessels (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014).

6.1.3. Auxiliary Power Units (APUs)

An Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) generates non-propulsive power for a vehicle, serving a crucial role in providing energy for various onboard systems. Unlike portable generators commonly used in boats and recreational vehicles (RVs), APUs are integrated directly into the vehicle. These units are especially important for large commercial airplanes, where power demands can reach up to 500 kW, requiring a wide range of operational capacity (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014). By decoupling the APU from the primary propulsion system, vehicles can optimize their overall energy efficiency. This strategy is widely adopted across various modes of transport, including cars, boats, ships, locomotives, airplanes, buses, military vehicles, and more.

APUs are responsible for powering a variety of vehicle functions, such as electrical appliances, air conditioning, refrigeration, entertainment systems, lighting, heating, and communications. Given their significant electrical energy demands, certain vehicles like recreational boats, airplanes, large trucks, service vehicles, and law enforcement vehicles present particularly promising markets for APUs. Furthermore, refrigeration vehicles also require reliable auxiliary power systems to maintain temperature control.

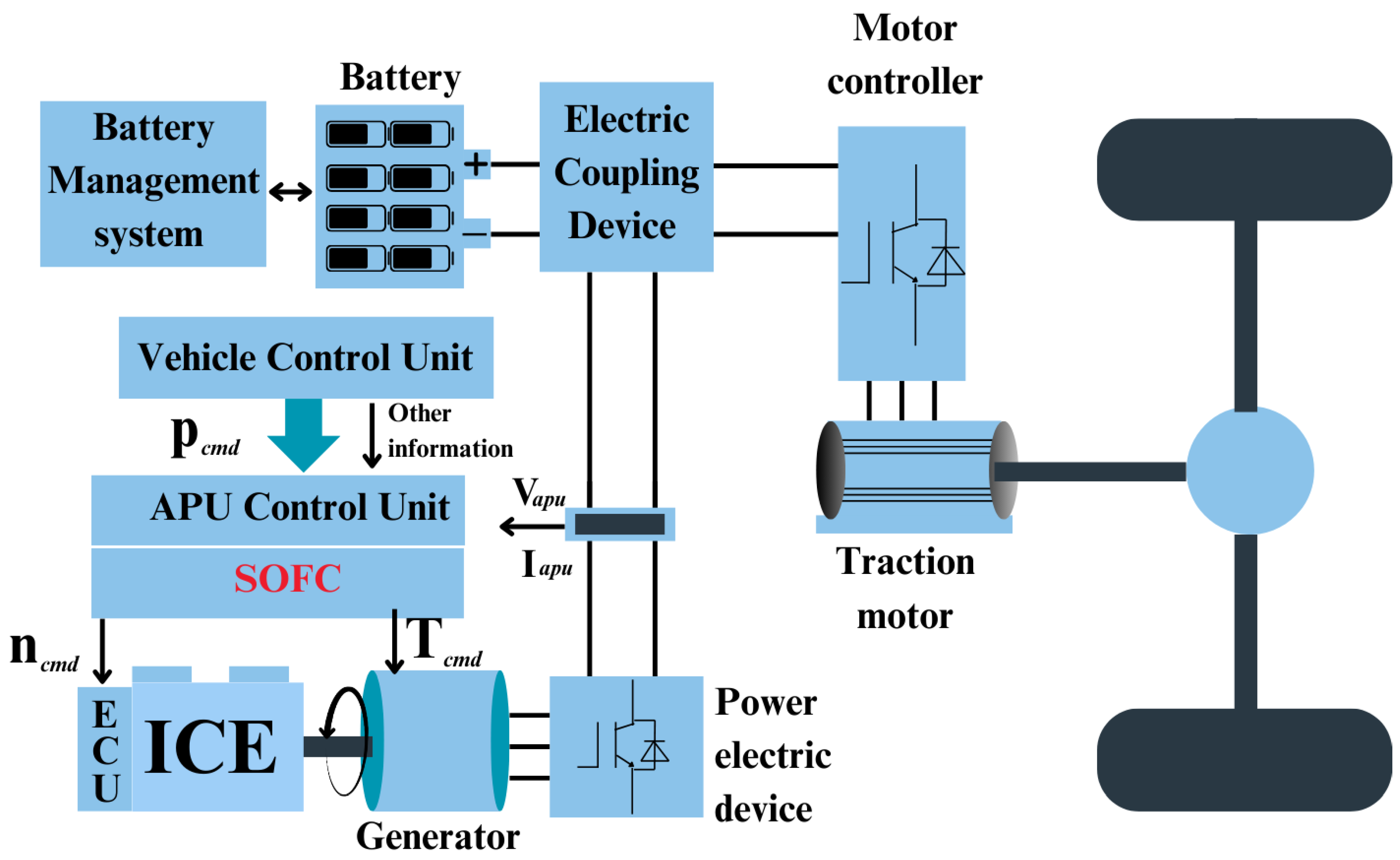

The demand for APUs is expected to rise as automobiles incorporate more electrical appliances and comfort features. While APUs are widely used, fuel cells present a cleaner alternative, offering shorter startup times, reduced noise, fewer pollutants, and higher efficiency. For example,

Figure 26 illustrates the integration of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) into hybrid APU systems for internal combustion engine (ICE) hybrid systems. These hybrid systems can significantly improve vehicle efficiency while reducing environmental impact.

Studies have shown that using fuel cell APUs in heavy-duty trucks, in place of traditional APUs, can lead to substantial reductions in emissions. It is possible to decrease particulate matter-10 emissions by as much as 65%, NOx emissions by up to 95%, and CO2 emissions by over 60% (Henne & Friedrich, 2009). Heavy-duty trucks, which often operate at idle for extended periods, waste fuel, increase pollutant emissions, and suffer from inefficient engineering. The development of fuel cells for APU applications, including Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs), Direct Methanol Fuel Cells (DMFCs), and SOFCs, is gaining momentum. These fuel cells can operate on a variety of fuels such as hydrogen, petrol, natural gas, LPG, methanol, and diesel.

6.1.4. Light Traction Vehicles (LTVs)

Light traction vehicles (LTVs) encompass a variety of transportation and material-handling machines, including personal wheelchairs, golf carts, motorbikes, electric-assisted bicycles, airport tugs, and various types of equipment such as pallet trucks, forklifts, and tow trucks. These vehicles, particularly forklifts, have gained notable attention for showcasing the application of fuel cell technology in the transportation sector. In North America alone, approximately 2.5 million forklifts and similar material-handling vehicles play a crucial role in the warehouse and distribution industries (Qi, 2009).

Historically, these vehicles have been powered by combustion engines fueled by diesel, petrol, LPG, compressed natural gas, or propane, along with rechargeable lead-acid batteries. However, the adoption of fuel cells is increasingly gaining traction due to their numerous benefits. These advantages include extended operational hours (ranging from 2 to 5 minutes), adaptability to temperature fluctuations, minimal self-degradation during charge/discharge cycles, and the ability to operate both indoors and outdoors. Moreover, fuel cells offer space-efficient refueling stations, lower harmful emissions, high efficiency, exceptional load-following dynamics, and reduced maintenance needs. With these qualities, fuel cells have the potential to revolutionize traditional forklifts and similar vehicles over time.

While onboard hydrogen generation systems remain less feasible for this purpose, refueling stations utilizing liquid hydrogen or fuel-feeding systems are becoming more viable alternatives. Currently, the U.S. market has around 1,300 fuel cell-powered forklifts, which are typically integrated with ultracapacitors for quick power delivery and 5-20 kW Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs) (Dicks, 2012).

Additionally, fuel cell-powered electric-assisted bicycles and scooters are in development, offering an environmentally friendly alternative for short to medium-distance travel. These vehicles present a promising solution to reducing traffic congestion while avoiding the use of expensive hydrocarbon fuels (Hwang, 2012). The success of fuel cell-powered personal wheelchairs and light carts further highlights the expanding potential of LTVs across various sectors (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014).

6.1.5. Heavy-Duty Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (H-FCEVs)

As the transportation sector continues to explore environmentally sustainable solutions, Heavy-duty Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (H-FCEVs) have emerged as a promising option. These vehicles, which include buses, heavy-duty trucks, locomotives, vans, and utility trucks, utilize fuel cells for electric power, offering several advantages over conventional diesel-powered alternatives.

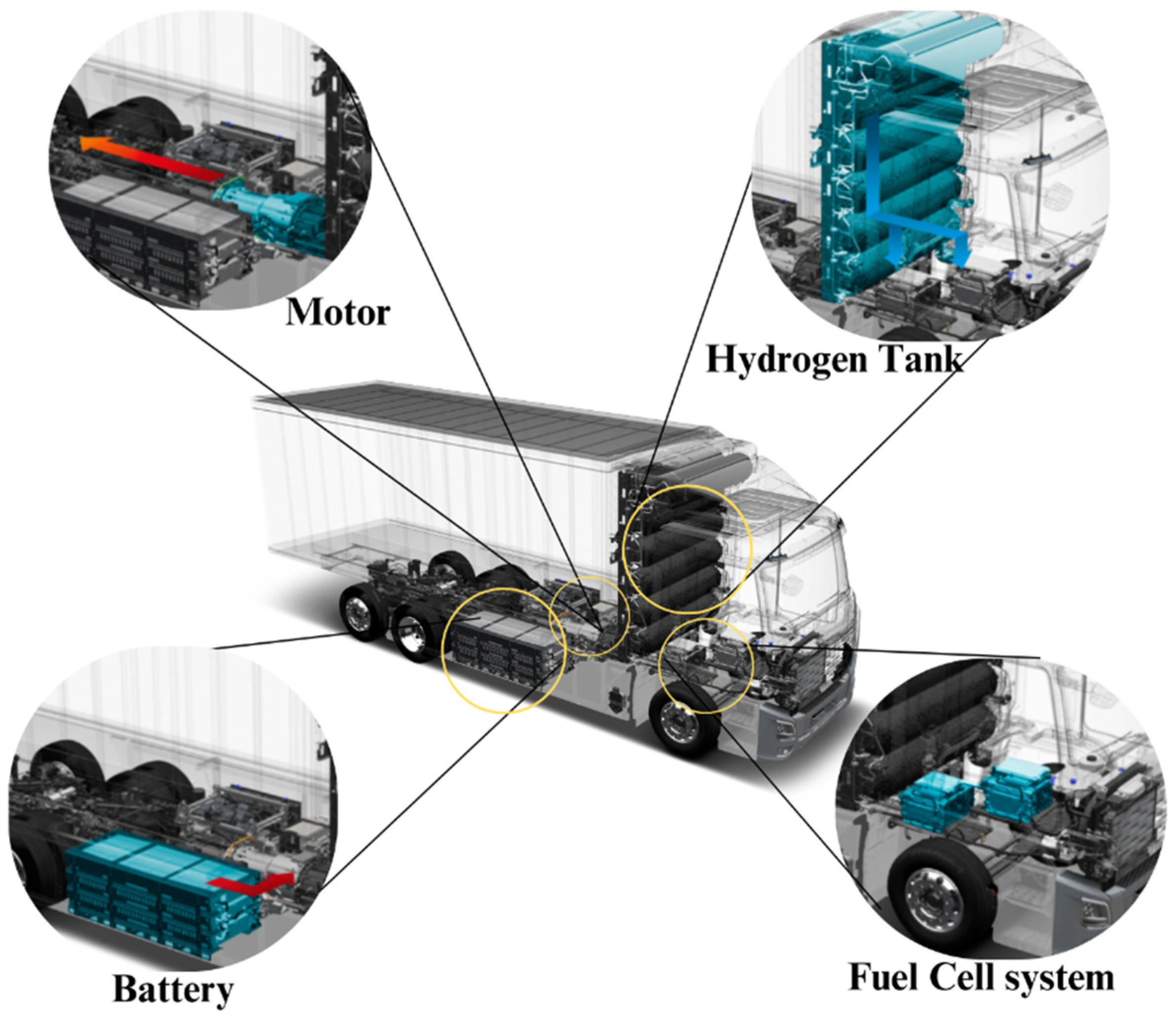

One prominent example of an H-FCEV is the XCIENT Fuel Cell Truck, developed by Hyundai.

Figure 27 illustrates this state-of-the-art heavy-duty truck, which is powered by hydrogen fuel cells. The XCIENT Fuel Cell Truck from Hyundai is an example of a product which illustrates prospect of fuel cell technology in the heavy-duty vehicle segment. FCEBs are regarded as cleaner options for public transport because the buses are less noisy, less polluting, and have lower emissions compared to other vehicles, like traditional diesel ones (Hyundai, 2021).

The FCEB’s benefits, such as noiseless operation and lower emission, are especially important for environmentally sensitive urban areas. Because of their fixed routes and the possibility to accommodate design flexibility, buses are good candidates for hydrogen fuel cell technology which offers better hydrogen storage and transport infrastructure. Initiatives to promote the adoption of FCEBs for public transportation have been launched by governments and the private sector in many parts of the world for example Australia, Europe, Canada, China, Brazil, and the United States (Saxe et al., 2008). Theses projects are geared towards the development of public transport systems that are sustainable and friendly to the environment, which objectives are in harmony with global targets.

FCEBs, on the other hand, have issues with economic efficiency when compared to conventional diesel powered buses. The primary barrier is the lack of development of fuel cell technology and the absence of economies of scale which make these vehicles costlier. Nevertheless, achievement, especially in the aspects of durability and cost-efficiency, has been noted due to developers like Ballard, Hydrogenics, and Daimler AG (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014). The improvements are vital in ensuring that fuel cell buses can be produced at affordable prices.

Other industries are also progressing in developing H-FCEVs. For instance, Vision has developed a hydrogen fuel cell class 8 truck which works at different ambient temperatures and possesses high power, good range, and fast refueling capabilities. In addition, Heliocentris in Germany has been building a fuel cell hybrid refuse collection vehicle which uses diesel engines in addition to fuel cells, demonstrating the adaptability of fuel cell technology. Interest in the implementation of fuel cells in locomotives has also been growing, with some investigations suggesting good efficiency and dependable power output (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014).

6.1.6. Light-Duty Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (L-FCEVs)

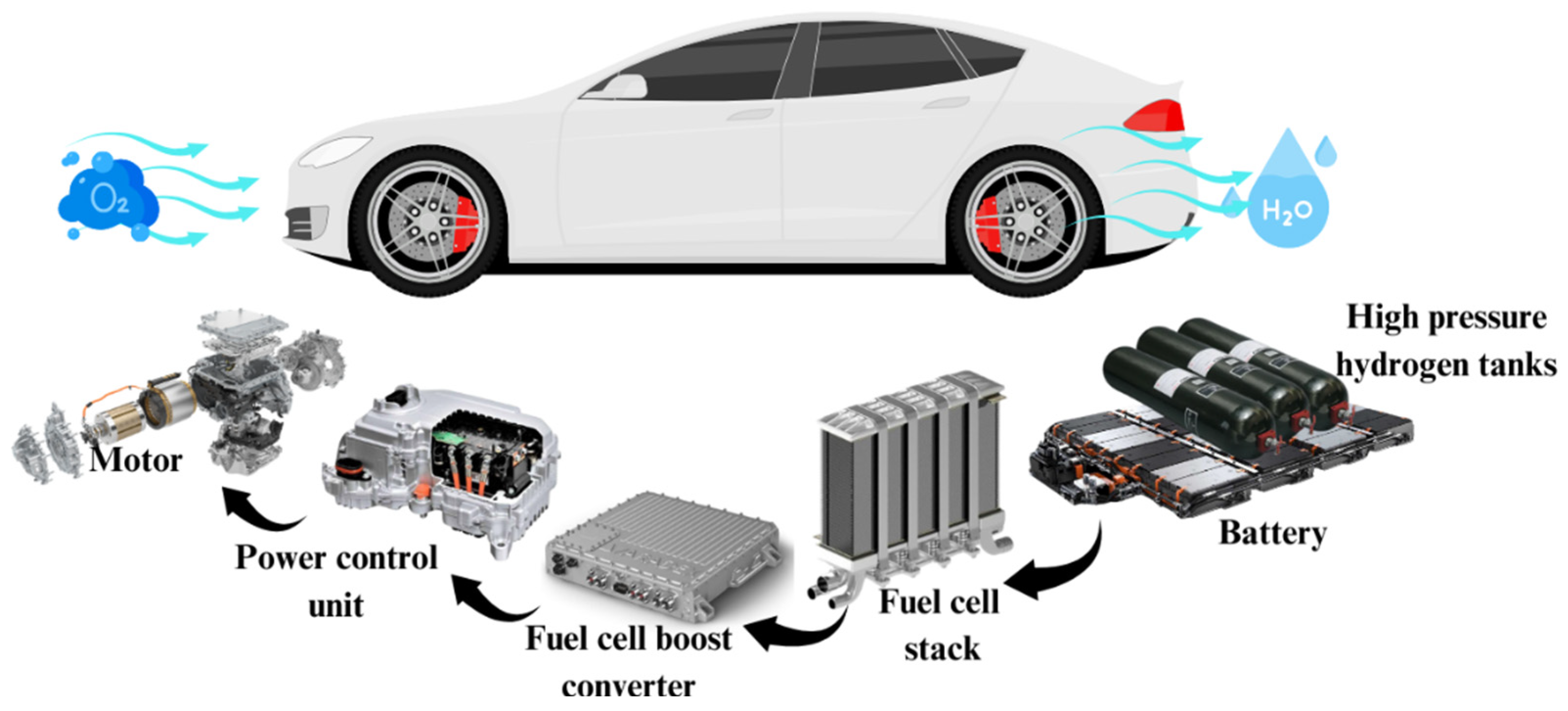

Light-duty fuel cell electric vehicles (L-FCEVs) offer several significant advantages over traditional internal combustion engine vehicles. These benefits include quieter operation, enhanced energy efficiency, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and greater flexibility in design. As depicted in

Figure 28, which provides an overview of the hydrogen-powered drivetrain in Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs), the system operates with key components that contribute to its environmentally friendly performance. Hydrogen is stored in high-pressure tanks, which are then supplied into the fuel cell stack. Inside the fuel cell, hydrogen combusts with oxygen to produce electricity. The fuel cell boost converter raises the voltage level, and the electricity is employed by the power control unit. The vehicle is then powered by a motor, and the additional energy depleted from the battery will be supplied when needed. Importantly, water vapor (H

2O) emission is the only byproduct released from this process, showcasing the environmentally friendly benefit of FCEVs. Unlike other vehicles, L-FCEVs L-FCEVs have higher efficiency during cold weather and longer driving range compared to light-duty battery electric vehicles (L-BEVs), and faster re-fueling usually takes less than two minutes. Moreover, their weight is comparatively lower than battery-powered ones. However, due to the challenges surrounding stack durability and lifecycle costs, L-FCEVs still has limited commercial availability. Various technical difficulties still need to be solved like system size and mass optimization, cold weather start-heating, air compression system enhancement, heat dissipation improvement, catalyst tolerance increase, and membrane humidification, start-stop cycle endurance, and hydrogen safety issues. Furthermore, compliance with hydrogen storage regulations poses additional challenges. L-FCEVs predominantly utilize proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), a technology that is being increasingly adopted by leading automakers such as Nissan, Hyundai, Daimler AG, Volvo, Volkswagen, Honda, and General Motors. A notable milestone was achieved when Hyundai’s L-FCEV, the ix35, entered mass production in 2013, with plans for deployment in Europe ("First Hyundai Ix35 FCEV Rolls off Assembly Line in Korea," 2013). The competition between L-FCEVs and L-BEVs primarily centers around the choice of energy source, energy conversion chain, and design specifications. Until one of these technologies proves superior, light-duty hybrid electric vehicles (L-HEVs) that combine fuel cells and batteries may serve as a transitional solution. In terms of driving range, simulations by Thomas (2009) show that L-FCEVs can achieve ranges greater than 160 km when using natural gas or biomass as the primary energy source. The study considers critical parameters such as vehicle mass, storage space, cost, emissions, refueling time, and energy efficiency. For L-FCEVs, hydrogen is generally produced off-board and supplied through designated fueling stations. Ongoing research is investigating alternative storage methods to improve the long-term viability of L-FCEVs. While current hydrogen storage techniques have limitations, technologies such as cryo-compressed hydrogen storage, ammonia borane chemical storage, and alkane metal hydrides show promise (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014). Onboard hydrogen generation, while not feasible at present due to constraints in size, weight, startup time, and safety, could potentially become viable with future advancements in reformation and hydrogen generation technologies.

6.2. Stationary Applications

Power generation for home, commercial, and industrial uses heavily rely on stationary fuel cells. They meet the needs for grid-assisted and grid-independent power supplies. These include Remote-area power supplies (RAPS), emergency backup power supplies (EPS), and combined heat and power (CHP) generation. Almost 70% of yearly fuel cell shipments at the MW level are accounted for by the stationary fuel cell sector 24.

6.2.1. Remote-Area Power Supply (RAPS)

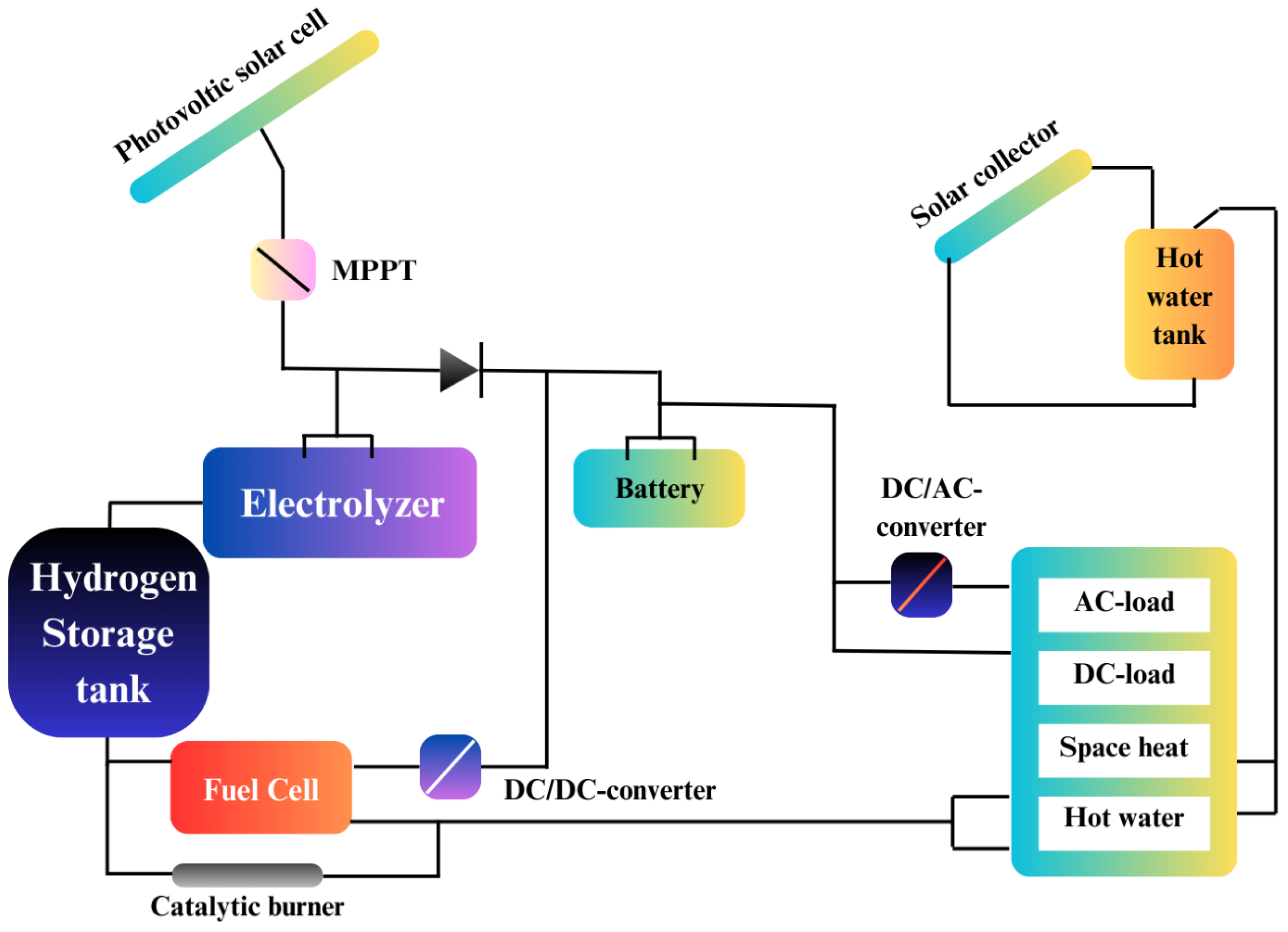

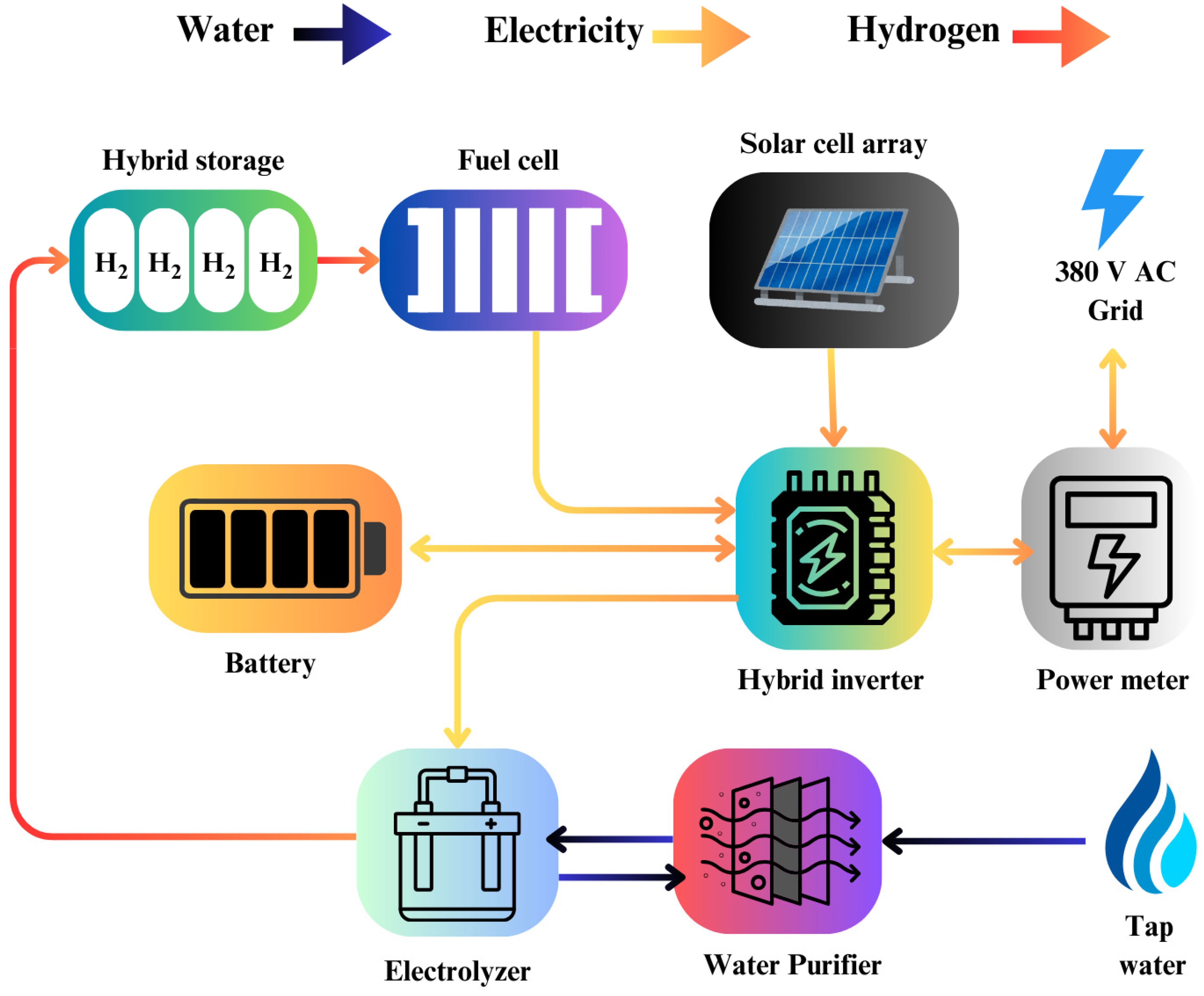

Figure 28 illustrates the schematic of a simulated solar-hydrogen-fuel cell system designed for a Remote-Area Power Supply (RAPS) application, offering a clear visualization of how renewable energy sources, like solar power, can be combined with hydrogen and fuel cells to provide a reliable electricity solution for off-grid areas. This system is especially important for providing electricity in remote locations that lack access to the main power grid.

Fuel cells are crucial for powering isolated areas, where conventional grid infrastructure is not available. RAPS systems present a cost-effective solution for electrifying rural and urban off-grid zones, particularly in challenging terrains such as forests and mountainous regions, where extending traditional power lines is impractical or too expensive. The cost of extending the grid is high due to issues such as significant transmission losses, low population density, and the need for extensive infrastructure. In these regions, RAPS technologies hold great promise, especially in developing countries.

Currently, a combination of hydrocarbon-based, renewable-based, or hybrid systems are used in RAPS solutions (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014). An important aspect of RAPS development is the use of Combined Heat and Power (CHP) systems, which improve performance by generating additional power, particularly in urban off-grid areas. While diesel engines have traditionally been used for RAPS, they are becoming less favorable due to their high carbon emissions and noise pollution. Fuel cells offer a cleaner alternative, as they can utilize light hydrocarbon reforming or natural gas. However, the challenge of transporting these fuels to remote areas remains a significant hurdle.

To offer a more sustainable and independent energy solution, hybrid and integrated energy systems are being explored. These systems combine renewable energy sources, such as solar photovoltaics (PV), with energy storage technologies like batteries, to provide reliable power. In fact, PV-based RAPS systems are expected to generate up to 130 GW by 2030, serving residential, commercial, and industrial users (Perrin & Lemaire-Potteau, 2009).

One of the main challenges with renewable energy is its intermittency, which can be effectively addressed by integrating hydrogen systems. As depicted in Figure 28, these systems typically include a water electrolyzer, fuel cells, and hydrogen storage, creating a more dependable and sustainable energy system. Despite the advantages of hydrogen systems, they face competition from PV and battery-based systems, which are more commonly used in RAPS applications. Research has shown that while hydrogen systems hold promise, they are not yet as cost-effective as conventional batteries. To become more competitive, the cost of fuel cell systems needs to be reduced by approximately €300/kW, while hydrogen storage tanks and water electrolyzers should see a 40% and 50% cost reduction, respectively (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014).

If the cost, efficiency, and durability challenges can be overcome, hydrogen fuel cell systems could provide a critical solution for the nearly two billion people worldwide who lack access to reliable grid electricity.

6.2.2. Emergency Backup Power Supply (EPS)

In the telecom industry, fuel cells are gaining traction as a critical alternative to traditional batteries in the emergency backup power supply (EPS) market. The growing popularity of fuel cells can be attributed to their exceptional power densities, high energy output, adaptability to diverse environments, compact size, long operational lifetimes (typically two to ten times longer than conventional lead-acid batteries), and modular design. These characteristics make them an ideal solution for industries that require reliable backup power, such as telecommunications, hospitals, data centers, banks, and government institutions. Among the various fuel cell technologies, Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs) and Direct Methanol Fuel Cells (DMFCs) are particularly favored in EPS applications, given their efficiency and performance (Varkaraki et al., 2003). High dependability is paramount in these sectors, where continuous, reliable power is necessary, particularly when grid electricity is unavailable. EPS systems typically need to provide power in the range of 2 to 8 kW to ensure smooth operations during power outages. The long-lasting nature of fuel cells makes them an attractive choice in this context, where uptime is critical. As shown in

Figure 29, the integration of fuel cells into emergency power supply systems offers a promising solution, providing a reliable, sustainable energy source when conventional power fails (Varkaraki et al., 2022).

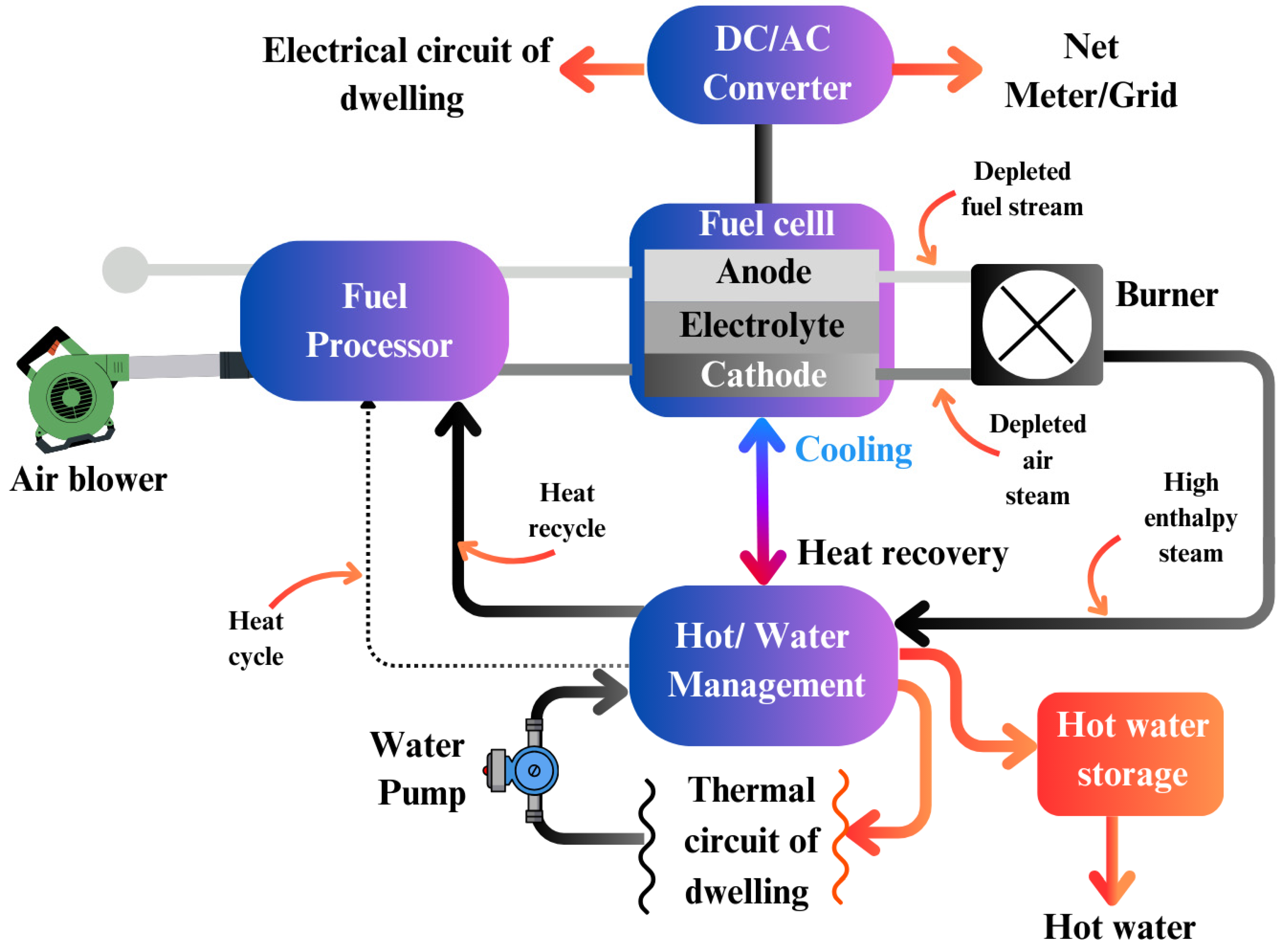

6.2.3. Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Generation

Decentralized, distributed power generation could be increasingly replaced by fuel cells due to their high efficiency, minimal emissions, excellent load-following capabilities, and stationary design. These advantages make fuel cells ideal for use in both large residential blocks and individual households for the distributed generation of Combined Heat and Power (CHP) or domestic electricity. In fact, Japan is a global leader in residential CHP fuel cell systems, with thousands of homes relying on them for both heating and electricity (Staffell et al., 2019). Fuel cell systems used for residential CHP can vary in size, offering capacities ranging from a few kilowatts to several megawatts to meet diverse load demands.

Figure 30 illustrates the schematic diagram for fuel cell micro-CHP systems, showcasing their typical configuration for residential applications (Hawkes et al., 2009).

To enhance their functionality, residential CHP fuel cells can be integrated into Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power (CCHP) systems. These systems not only provide electricity but also support space heating, household water heating, and cooling. The efficiency of CHP and CCHP systems can reach up to 80%, making them highly efficient energy solutions (Ma et al., 2011). However, further research is needed to address technical challenges and reduce capital costs associated with these systems. Larger residential complexes are generally more suited to high-temperature fuel cells (HTFCs), while Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs) and Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cells (PAFCs) are particularly appropriate for household-level CHP generation.

Designing CHP systems to either assist the grid or operate independently offers various operational options. Grid-independent systems face complexities due to dynamic load fluctuations, which can be mitigated by increasing the fuel cell capacity or integrating energy storage solutions, such as battery banks or ultracapacitors. In contrast, grid-assisted systems export excess power to the grid when demand is low and import electricity when load demands rise. Thermal energy storage is also critical for the effective operation of CHP systems. In terms of emissions, fuel cells powered by natural gas, such as Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells (MCFCs) and PAFCs, produce significantly fewer harmful pollutants (NOx, PM-10, and CO) compared to combustion-based distributed generation systems (M. Wang et al., 2010).

In addition to residential applications, the development of combined fuel cell cycles is being explored for use in industrial activities to simultaneously produce chemicals and energy. However, the primary technological challenge for stationary CHP fuel cells remains extending their lifespan to approximately 80,000 hours, a goal that is essential for their commercial viability (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014).

6.3. Portable Applications

There are two main markets for portable fuel cells:

6.3.1. Consumer Electronics

Research is underway to investigate the use of fuel cells in computers, cell phones, radios, camcorders, and other battery-powered gadgets. Typically, they provide 5 to 500 W power ranges, while some more sophisticated types can provide power up to the kW level (Sharaf & Orhan, 2014). Unlike stationary fuel cells, which are bulky and limited in their uses, portable fuel cells are lightweight and portable. They could be used in future personal devices as a result of their high energy density and adaptability, five to ten times higher than traditional rechargeable batteries. Because of its silent operation, energy density, low weight and high power in comparison to conventional battery-based equipment, portable fuel cells—specifically PEMFCs, direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs) and reformed methanol fuel cells (RMFCs), —are also being used by the military industry.

6.3.2. Mobile and Emergency Power

These fuel cells are intended for individual usage during outdoor pursuits such as hiking and camping. They also supply emergency power for minor commercial uses like surveillance and transportable signs.

Even though portable fuel cells have benefits, including reduced weight, increased energy density, and no requirement for electrical recharging, they have not yet reached cost and durability goals. Toys, kits, gadgets, and miniature remote-control cars are among the rapidly expanding markets in the portable sector, as are portable battery chargers. Significant advancements in the mobile fuel cell industry depend on addressing several technical issues, including heat dissipation, noise reduction, emissions control, fuel storage and distribution, shock resilience, responsiveness to demand fluctuations, varied operating conditions, air pollution tolerance, and the capacity for fuel containers to be reused and recycled.

7. Major Challenges of Fuel Cell Technology