1. Introduction

Neck pain, a common source of discomfort and disability globally, is frequently encountered by individuals and is often classified as non-specific due to its unknown etiology[

1]. This condition has a multifactorial origin, potentially influenced by ergonomic and individual factors including age, behavioral attitude, and psychosocial distress such as anxiety or job satisfaction[

2].

Non-specific neck pain (NSNP) is identified as the most common and the fourth leading cause of musculoskeletal disorders globally. Approximately 70% of the population encounters neck pain at some point in their lives, with an annual incidence ranging from 15% to 50%[

3]. NSNP is characterized by discomfort in the posterior and lateral areas of the neck without specific indicative signs and symptoms [

4]. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain lasting for more than 3 months as chronic pain. Therefore, when a patient's non-specific neck pain persists for over three months, we classify it as chronic non-specific neck pain(CNSNP)[

5].

Despite its high prevalence, the management of CNSNP remains challenging. Commonly employed conservative interventions include patient education, manual therapy, therapeutic exercise, electrotherapy, acupuncture, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and a combination of these modalities[

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Fascial Manipulation (FM) is a manual therapy technique originating from Italy's physical therapist Luigi Stecco, based on the concept of fascial continuity for the holistic assessment and treatment of musculoskeletal pain and internal functional disorders.

Existing clinical studies have demonstrated that Fascial Manipulation can effectively treat musculoskeletal pain and disorders in conditions such as trigger finger[

11], chronic recurrent shoulder pain[

12], patellar tendinopathy [

13], subacute whiplash associated disorders[

14], chronic ankle instability[

15], Morton's syndrome[

16], temporomandibular disorders[

17], sacroiliac joint dysfunction[

18], carpal tunnel syndrome[

19], chronic non-specific low back pain[

20,

21], and post-hip arthroplasty pain and functional impairments[

22]. Due to the potential significant role of the thickness of loose connective tissue within the fascia in the pathogenesis of CNSNP[

23], and given that Fascial Manipulation primarily targets this loose connective tissue in the deep fascia[

23], we aimed to investigate the short-term and long-term efficacy of Fascial Manipulation through the randomized controlled trial. This research may provide new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of CNSNP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study is a randomized controlled trial approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University (approval number:2023ZDSYLL209-P01), and registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (registration number: ChiCTR2400088061) at

https://www.chictr.org.cn/. From July to October 2023, a total of 52 patients with CNSNP were recruited from the Rehabilitation Medicine Department outpatient clinic of Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University. All participants provided signed informed consent to participate in the study. The screening and inclusion process was conducted by a single therapist who screened based on the following inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria: A total of 52 CNSNP patients (aged 20-50 years) presenting at the Rehabilitation Medicine Department outpatient clinic were randomly recruited as participants. These individuals had neck pain persisting for more than 3 months, sitting for more than six hours a day, no history of surgery or trauma in the neck and shoulder area, and no significant smoking or alcohol consumption habits.

Exclusion criteria: 1) Severe arthritis or joint dysfunction; 2) Recent use of muscle relaxants; 3) Presence of tumors, inflammatory diseases, pregnancy, or fibromyalgia; 4) Cervical disc herniation or whiplash injuries; 5) History of neck surgery; 6) Other serious systemic diseases such as hypertension or arrhythmias.

2.2. Procedures and Data Collection

2.2.1. Group B

Routine physical therapy and health education were provided as follows:

1) Interferential current therapy: We selected the XSMI-100D electrotherapy device (Tianjin Shunbo Medical Equipment Co., Ltd.) and adjusted the suction force and current intensity to the maximum tolerable threshold for each patient. Electrodes were placed at the intersection of the fibers of the bilateral upper trapezius muscle and levator scapulae muscle, with each session lasting 20 minutes, conducted once every two days, three times a week, for a total of 12 treatments.

2) Magnetic thermal therapy: We utilized the LGT-2600D magnetic therapy device (Guangzhou Longzhijie Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). The magnetic thermal therapy device was placed at the center of the painful area, providing a mild heat intensity for 20 minutes per session. Treatments were conducted every two days, three times a week, for a total of 12 sessions.

3) Neck pain health education: Common causes of CNSNP, diagnostic principles, symptom presentation and assessment methods, daily life precautions, and some pain relief methods were discussed.

2.2.2. Group A

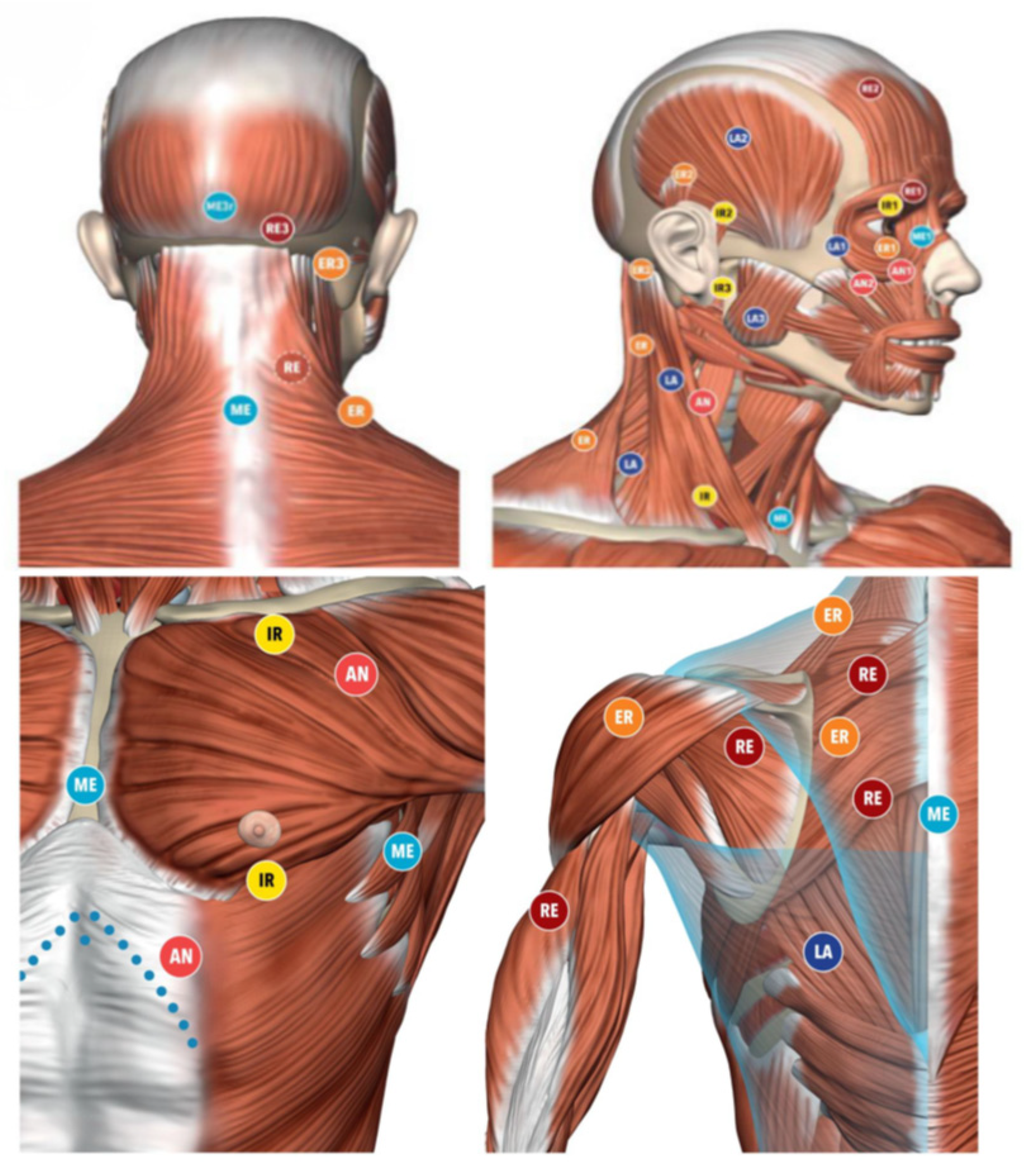

Treatment in the group A consisted of routine physical therapy and health education, supplemented with Fascial Manipulation once a week for a total of four sessions(

Table 1). Following the standard protocol of Fascial Manipulation, the therapist meticulously documented the cervical pain patterns of participants in group A, as well as any history of traumas, fractures, soft tissue injuries, moderate to severe musculoskeletal disorders, surgeries, and scars outside the neck region. Based on this information, the therapist deduced the compensatory patterns and treatment areas for the patients. Subsequently, specific movement tests and palpation of deep fascial densifications were conducted to formulate a comprehensive Fascial Manipulation treatment plan[

18]. The same therapist provided treatment according to the plan, which included a total of 6 treatment CC (Center of Coordination) points. These treatment points are anatomically safe as they do not overlap with major superficial nerves and veins (

Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The average treatment time for densification points is 3.24 minutes, with 19% achieving a reduction in pain by half in under two minutes, and 16.2% achieving the same in over five minutes[

24]. Each treatment point requires treatment until the operator perceives a significant change in tissue gliding under their hand and the patient experiences a reduction in pain by more than half[

24].

The specific timing, duration, quantity, frequency, and number of sessions for the two different approaches are outlined in the following scheme:

2.3. Data Collection

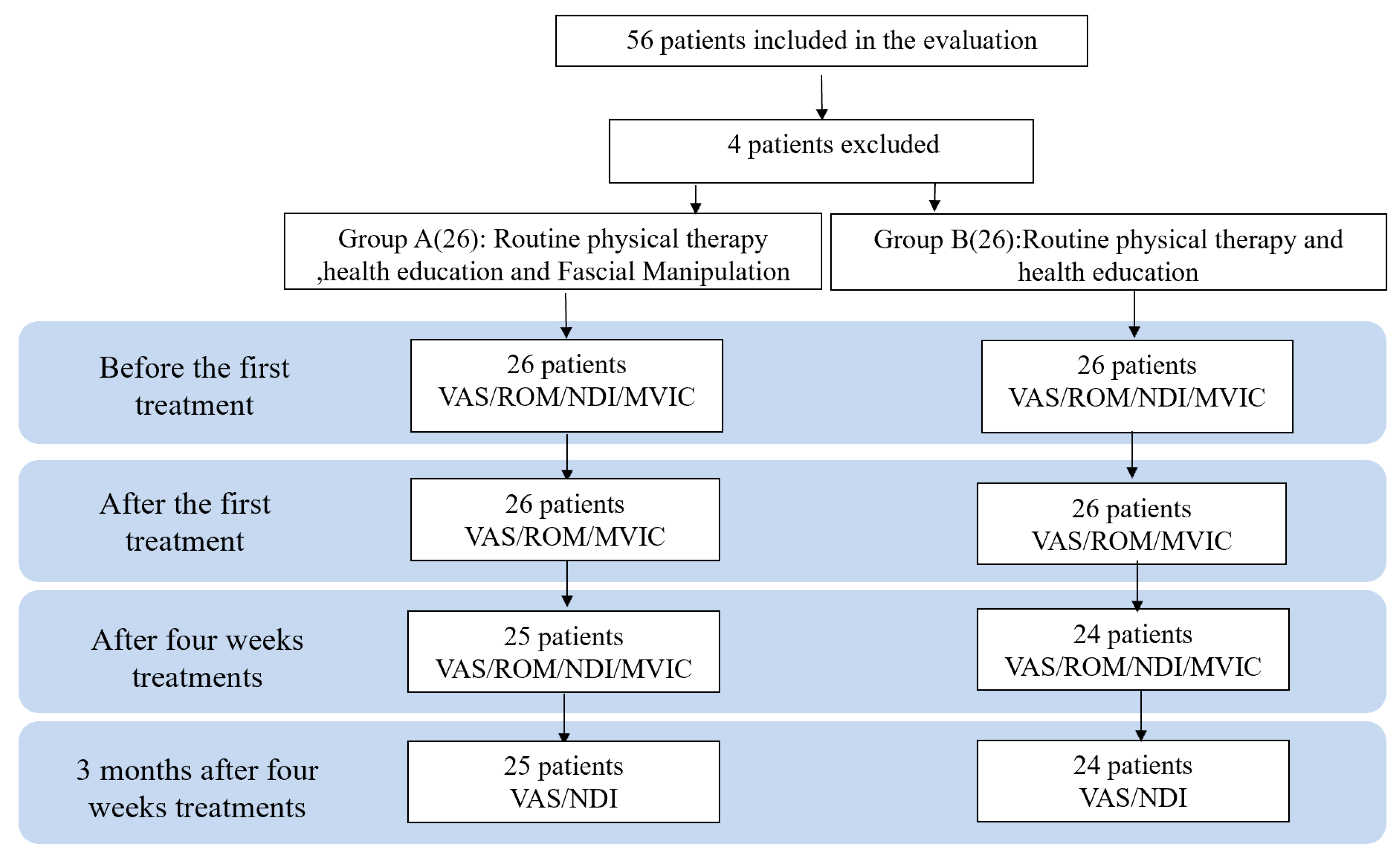

The visual analog scale (VAS) values, range of motion (ROM) of the cervical spine, and Maximal Voluntary Isometric Contraction (MVIC) of the cervical spine flexion and extension were assessed at three time points: before treatment (T0), immediately after treatment (T1), and after four weeks treatment (T2). The Neck Disability Index (NDI) was assessed at T0 and T2. A follow-up was conducted via WeChat three months after the completion of all treatments to assess VAS scores and NDI scores once again (

Figure 3).

2.3.1. VAS

The visual analog scale (VAS) was used to assess pain intensity. Pain intensity was rated on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the most severe pain. Participants were asked by the therapist to mark on the VAS scale the point that corresponded to their level of pain[

25].

2.3.2. ROM

The range of motion (ROM) of the cervical spine was measured using a handheld MicroFET3 dynamometer. To measure the ROM, the participants were seated with their thorax stabilized, and the flexion and extension movements of the cervical spine were measured three times, with the average value recorded. Since the end range of cervical flexion and extension includes some contribution from the thoracic spine, when measuring the ROM of the cervical spine using MicroFET3, the therapist separately measured the range of motion of the thoracic spine during maximum flexion and extension of the cervical spine. The compensation values obtained from the thoracic spine were then subtracted from the measured values of the cervical spine to calculate the true range of motion for the cervical spine.

2.3.3. MVIC

We measured the Maximal Voluntary Isometric Contraction (kg) of the cervical spine using the MicroFET3 handheld dynamometer, which has demonstrated strong validity and reliability in assessing muscle strength[

26,

27,

28]. The measurements were conducted with the participant seated, and the device was positioned above the forehead for measuring flexion MVIC and above the external occipital protuberance for measuring extension MVIC. The measurements of the MVIC during flexion and extension were repeated three times, with the average value recorded, while ensuring the stability of the thorax to assist in the measurements.

2.3.4. NDI

The Neck Disability Index (NDI) was utilized for evaluating disability related to neck pain. Widely employed for assessing the disability caused by neck pain, the NDI demonstrates high test-retest reliability[

29]. This scale assesses 10 aspects including pain intensity, personal care (such as washing, dressing), lifting, reading, headaches, concentration, work, driving, sleep, and recreation. Each item is scored from 0 (no pain or no functional impairment) to 5 (unbearable pain or complete functional impairment). The questionnaire is self-administered and yields a total score ranging from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater disability.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using version 22 of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Software), with a significance level of p < 0.05 consistently considered as the threshold for statistical significance. The Kolgomorov–Smirnov test was employed to assess normality. Descriptive statistics were separately computed for both groups, utilizing measures of central tendency and their dispersion ranges, with parametric data described using the mean and standard deviation (SD), and non-parametric data described using the median and interquartile range (IR). Group differences in demographics were evaluated using the Student t-test. Continuous variables at different time points (T0, T1, T2, and T3) were subjected to statistical analysis using a mixed-model 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analysis of multiple comparisons.

3. Results

52 patients were enrolled in the study, with an age range of 21 to 49 years (mean age: 34.49 ± 7.37) and a CNSNP disease duration ranging from 3 to 20 months (mean months: 11.90 ± 4.74).(

Table 2) The decision to retain the null hypothesis was based on the overall homogeneity of the samples, ensuring comparability across most aspects.

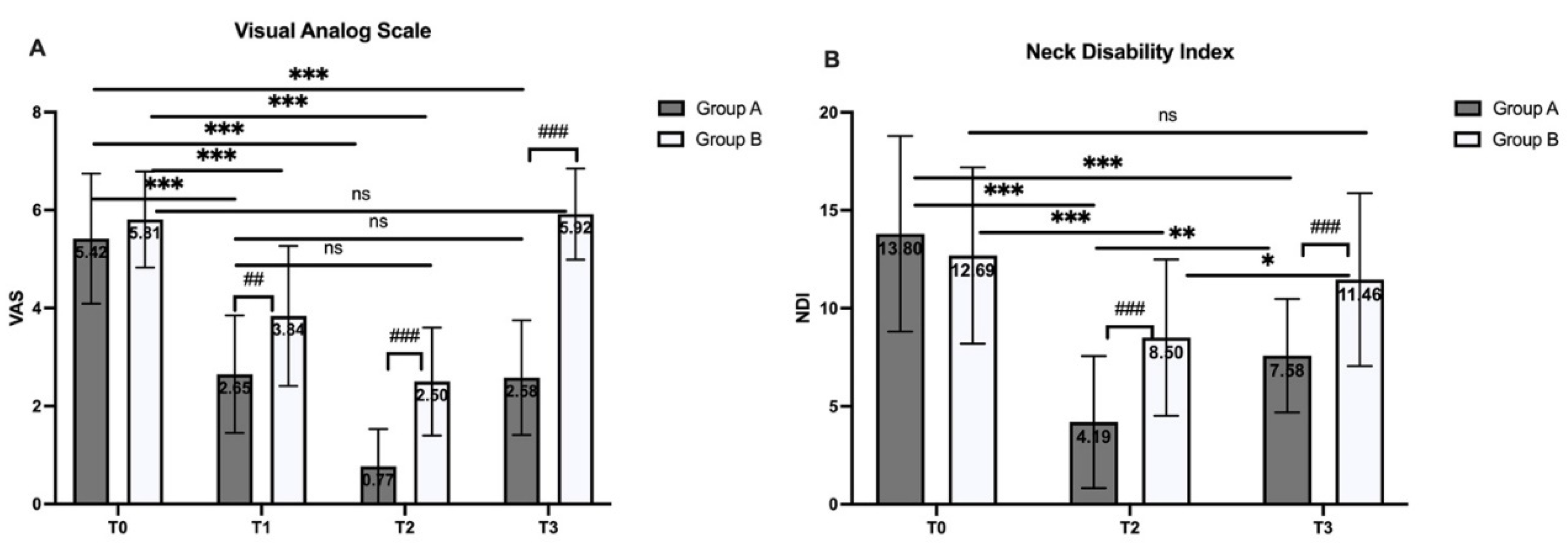

3.1. VAS

Compared to baseline (T0), both Group A and Group B demonstrated significant reductions in VAS scores after the first treatment (T1) and following the 4-week treatment period (T2) (P < 0.001) (

Figure 4A). However, at the 3-month follow-up (T3), the VAS score of group A remained significantly lower than T0 (P < 0.001) and showed no difference compared to T1 (P = 0.999), In contrast, Group B showed no significant difference between T3 and T0. Between groups, Group A consistently showed a significantly greater reduction in VAS scores compared to Group B, with differences observed at T1 (P = 0.02), T2 (P < 0.001), and T3 (P < 0.001). Also, there is no significant difference between VAS of T1 in group A and that of T2 in group B.

3.2. NDI

After the 4-week treatment, both Group A (p< 0.001) and Group B (p=0.002) showed significant reductions in NDI scores (

Figure 4B). At the 3-month follow-up (T3), the NDI score of group A remained significantly lower than baseline (T0) (p<0.001), while group B showed no significant difference between T3 and T0 (p=0.207). Between groups, Group A consistently showed a significantly greater reduction in NDI scores compared to Group B at T2 (P < 0.001), and T3 (P < 0.001).

3.3. ROM and MVIC

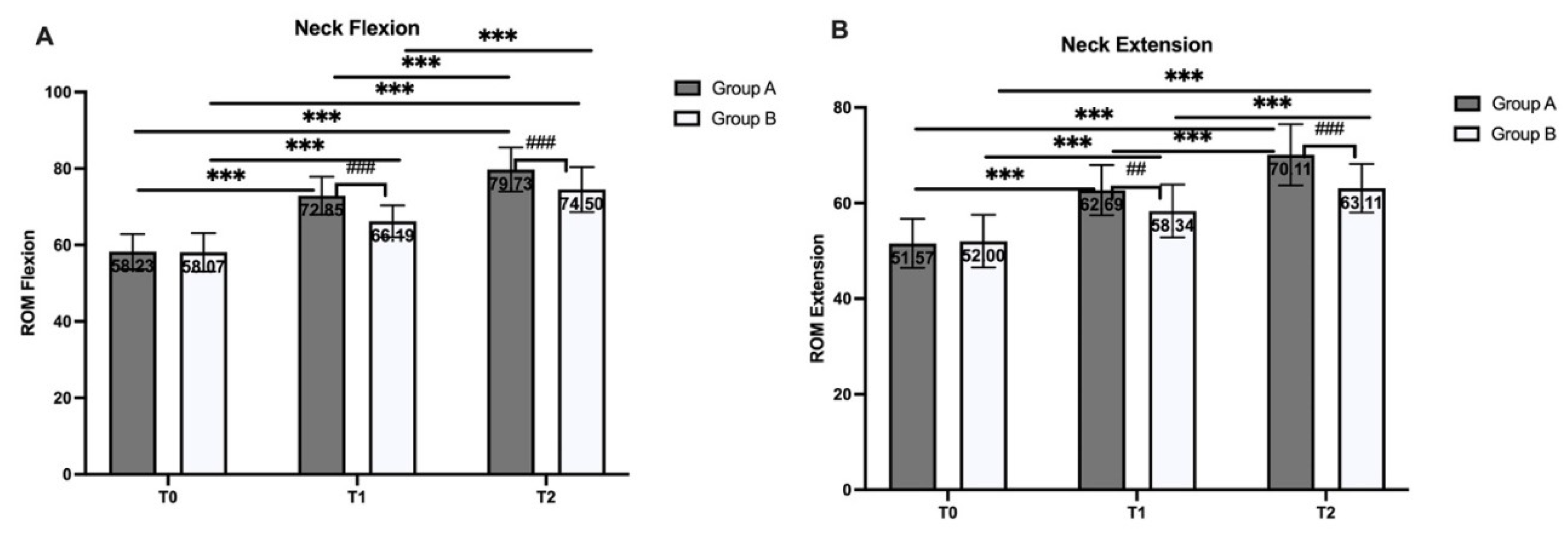

For ROM measured by neck flexion and extension (figure 5), compared to baseline (T0), both Group A and Group B demonstrated significant increase in flexion and extension after the first treatment (T1) and following the 4-week treatment period (T2) (P<0.001). Between groups, Group A consistently showed a significantly greater increasing in flexion and extension compared to Group B at T1 (P< 0.001) and T2 (P<0.01). Also, there is no significant difference between ROM (flexion and extension) of T1 in group A and that of T2 in group B (P>0.05).

Figure 5.

A:ROM flexion B: ROM extension. ns: no significant difference, #: significant difference between group, *: significant difference within group p<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: 0<0.001.

Figure 5.

A:ROM flexion B: ROM extension. ns: no significant difference, #: significant difference between group, *: significant difference within group p<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: 0<0.001.

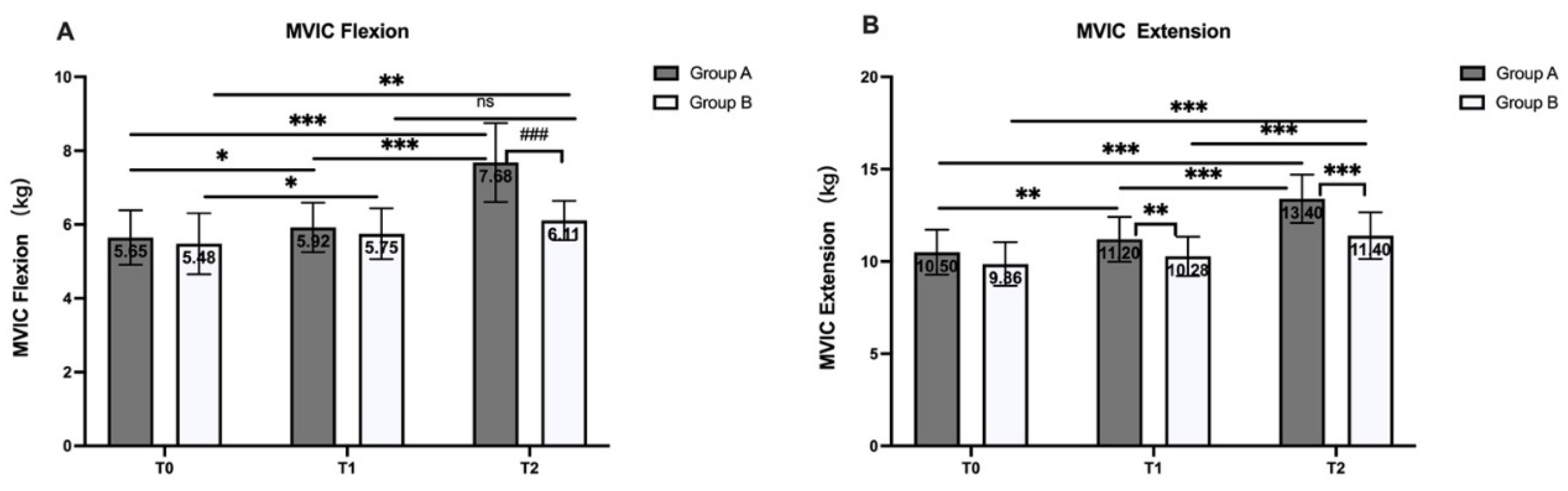

For strength measured by MVIC flexion and extension (

Figure 6), compared to baseline (T0), Group A demonstrated significant increase in both MVIC flexion and extension in T1 (flexion P<0.05; extension P<0.01) and T2 (P<0.001). In group B, compared to baseline (T0), there is a significant increase in MVIC flexion in T1 (P<0.05) and T2 (P<0.01), however in MVIC extension only T2 shows significant increase (P<0.001). Also, there is no significant difference between MVIC (flexion and extension) of T1 in group A and that of T2 in group B (P>0.05).

4. Discussion

Chronic neck pain is a common issue encountered in outpatient rehabilitation medicine. As the majority of chronic neck pain cases have unknown causes, they are often referred to as chronic nonspecific neck pain (CNSNP) [

10]. Treatment modalities for CNSNP include manual therapy, physical agent modalities, pharmacological interventions, exercise therapy, and health education[

30]. In the outpatient rehabilitation department of the Zhongda Hospital Southeast University, many patients with CNSNP still receive solely physical agent treatment. As a novel therapeutic technique differing from traditional Chinese soft tissue Tui Na techniques, Fascial Manipulation was the focus of this study to explore its effects on patients with CNSNP. Although literature indicates that the evidence level for manual therapy in treating CNSNP is low to moderate, there has been a growing number of studies investigating the impact of manual therapy on this condition in recent years. The majority of clinical research suggests that manual intervention is more effective than no intervention or control groups[

31].

Currently, most mainstream manual therapy approaches for chronic neck pain are primarily focused on the area of complaint, often overlooking the neck pain and functional impairments arising from chronic compensatory factors[

32,

33]. Fascial Manipulation (FM) techniques emphasize a holistic perspective in treatment, examining the continuity of fascia to identify the sources of compensation. In this study, although all participants were diagnosed with nonspecific chronic neck pain (CNSNP) and exhibited similar symptoms, the therapist would deduce the pathways of chronic compensation based on the specific patterns of pain exacerbation and the patient's medical history. This informed the selection of specific points within the fascial chains, namely the CC (Center of Coordination) points, for treatment, with each participant's treatment limited to six points[

34,

35]. Due to the nature of Fascial Manipulation, treatment points are often not confined to the area of neck pain, and multiple points may be distributed across the thoracic area, upper limbs, and even the lower back, pelvis. A study examining the effects of a single Fascial Manipulation treatment on sacroiliac joint dysfunction demonstrated that even when all treatment points were located at least 20 cm away from the primary pain site, significant immediate and one-month follow-up effects were still achieved[

18].

According to the VAS findings of this study, Group A demonstrated significant advantages over Group B in the pain control of CNSNP, regardless of whether assessed at T1 (single treatment) or T2 (four-week treatments). Furthermore, the absence of significant differences between Group A at T1 and Group B at T2 suggests that Fascial Manipulation enhances the treatment efficacy for CNSNP patients. The implementation of Fascial Manipulation in rehabilitation clinics not only enhances the efficacy of pain control but also significantly reduces the overall treatment duration for patients with CNSNP.

In terms of long-term efficacy, both the VAS and the NDI scores at the three-month follow-up (T3) in Group A were significantly improved compared to baseline (T0), while Group B showed no notable differences between T3 and T0. This indicates that the intervention of Fascial Manipulation has a significant long-term effect on CNSNP. Notably, the VAS scores for Group A at T3 were similar to those at T1, suggesting that while Fascial Manipulation offers a clear long-term benefit for CNSNP, the overall therapeutic response may diminish over time due to factors such as poor posture, psychosocial influences, or other ergonomic considerations. Future research should focus on examining the long-term effects of Fascial Manipulation when combined with interventions such as postural correction, exercise training, and ergonomic modifications for the management of CNSNP.

In the functional assessment, both the ROM and MVIC results indicated that both Fascial Manipulation and routine physical therapy treatments could enhance neck function. However, Fascial Manipulation proved to be more efficient, as Group A consistently demonstrated significantly greater improvements in both ROM (flexion and extension) and MVIC (flexion and extension) at both T1 and T2. Additionally, similar to the VAS scores, there were no significant differences between the ROM (flexion and extension) and MVIC (flexion and extension) scores at T1 in Group A and the T2 scores in Group B. This suggests that Fascial Manipulation can effectively enhance neck ROM and strength in flexion and extension with fewer treatment sessions compared to the control group, indicating that Fascial Manipulation is a more efficient approach to improving neck function.

The ability of Fascial Manipulation to alleviate distant pain and improve range of motion through the treatment of deep fascia's CC points may be attributed to enhanced flexibility within the entire deep fascial dynamic chain. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Burk et al., fascial therapy influences the tension in distal tissues and increases the range of motion in joints remote from the treatment area[

36]. This finding likely explains why the experimental group exhibited significantly greater improvements in range of motion compared to the control group.

The improvement in muscle strength may be attributed to the restoration of muscle spindle function[

37,

38] . Muscle spindles are highly specialized and crucial sensory receptors that play a vital role in the control of movement and the maintenance of muscle tone. Research has demonstrated that muscle spindles are associated with intramuscular connective tissue (IMCT) and are influenced by the activity of IMCT[

39,

40]. Furthermore, the external capsule of muscle spindles is connected to IMCT[

41]. The application of Fascial Manipulation targets the densified hyaluronan within the deep fascia, which alleviates the stiffness of the muscle spindles and enhances the activation of the motor units[

42]. Building on the findings of this study regarding the impact of Fascial Manipulation on strength, future research could focus on the effects of combining Fascial Manipulation with strength training to determine whether this integrated approach yields superior outcomes compared to strength training alone. If the results demonstrate a beneficial effect, implementing Fascial Manipulation as a preparatory treatment for deep fascia prior to strength training may enhance the overall efficiency of the training regimen.

4.1. Limitations

Limitations of this study include the fact that it was conducted in a rehabilitation medicine outpatient setting, where all participants exhibited typical symptoms of CNSNP. As a consideration to alleviate patients' symptoms, a control group with no intervention was not included. Additionally, there were variations among patients in terms of executing and understanding health education, including factors such as sitting time, emotional regulation, and common self-management strategies for neck pain, all of which could influence the outcomes.

4.2. Future Scope

Future studies could incorporate additional objective measures, such as lactate threshold and electromyography, to provide a more comprehensive assessment of muscle fatigue and electrical activity. To further investigate the efficacy of Fascial Manipulation in treating CNSNP, it may be beneficial to combine Fascial Manipulation with various training modalities or joint techniques to determine if the outcomes surpass those achieved with Fascial Manipulation alone. In the current study, the unique nature of Fascial Manipulation necessitated individualized assessment to identify treatment points corresponding to the CC points. These points were distributed across multiple areas, including the upper limbs, cervical and back, with most treatment points not being located in the primary area of complaint (the neck). Future research could explore whether a standardized selection process for Fascial Manipulation treatment points offers advantages over targeting only the CC points in the area of primary concern, thereby enhancing the scientific basis of the Fascial Manipulation approach.

5. Conclusions

Fascial Manipulation (FM) can significantly improve pain, cervical range of motion, and maximal voluntary isometric contraction of the neck flexor and extensor muscles in patients with chronic non-specific neck pain. Furthermore, significant improvements can still be observed three months after treatment.

Author Contributions

P.Z.: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration; X.Z.: writing—review and editing, formal analysis, methodology; J.G.: investigation, methodology; Y.F.: investigation, methodology; M.M.: writing—review and editing, project administration, conceptualization; C.S.: writing—review and editing, conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University (approval number:2023ZDSYLL209-P01).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Nanjing Sports Bureau for providing partial personnel and financial support for this research through the Sports Science Research Project (NJTY2024-101). The authors also extend their gratitude to the colleagues and intern therapists in the Rehabilitation Department of Zhongda Hospital Southeast University for their assistance during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNSNP |

chronic non-specific neck pain |

| FM |

Fascial Manipulation |

| VAS |

visual analog scale |

MVIC

NDI

ROM

IMCT |

maximal voluntary isometric contraction

neck disability index

range of motion

intramuscular connective tissue |

References

- Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S39-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malchaire J, Roquelaure Y, Cock N, Piette A, Vergracht S, Chiron H. Musculoskeletal complaints, functional capacity, personality and psychosocial factors. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2001;74(8):549-57. [CrossRef]

- de Campos TF, Maher CG, Steffens D, Fuller JT, Hancock MJ. Exercise programs may be effective in preventing a new episode of neck pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Physiother. 2018;64(3):159-65. Epub 20180619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, Haldeman S, Côté P, Carragee EJ, et al. A new conceptual model of neck pain: linking onset, course, and care: the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S17-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misailidou V, Malliou P, Beneka A, Karagiannidis A, Godolias G. Assessment of patients with neck pain: a review of definitions, selection criteria, and measurement tools. J Chiropr Med. 2010;9(2):49-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monticone M, Cedraschi C, Ambrosini E, Rocca B, Fiorentini R, Restelli M, et al. Cognitive-behavioural treatment for subacute and chronic neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(5):Cd010664. Epub 20150526. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tough EA, White AR, Cummings TM, Richards SH, Campbell JL. Acupuncture and dry needling in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(1):3-10. Epub 20080418. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Day RO, Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(7):1269-78. Epub 20170202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross A, Miller J, D'Sylva J, Burnie SJ, Goldsmith CH, Graham N, et al. Manipulation or mobilisation for neck pain: a Cochrane Review. Man Ther. 2010;15(4):315-33. Epub 20100526. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo B, Hall T, Bossert J, Dugeny A, Cagnie B, Pitance L. The efficacy of manual therapy and exercise for treating non-specific neck pain: A systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2017;30(6):1149-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordache SD, Frenkel Rutenberg T, Pizem Y, Ravid A, Firsteter O. Traditional Physiotherapy vs. Fascial Manipulation for the Treatment of Trigger Finger: A Randomized Pilot Study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2023;25(4):286-91. [PubMed]

- Bellotti S, Busato M, Cattaneo C, Branchini M. Effectiveness of the Fascial Manipulation Approach Associated with a Physiotherapy Program in Recurrent Shoulder Disease. Life (Basel). 2023;13(6). Epub 20230615. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrelli A, Stecco C, Day JA. Treating patellar tendinopathy with Fascial Manipulation. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2009;13(1):73-80. Epub 20080726. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picelli A, Ledro G, Turrina A, Stecco C, Santilli V, Smania N. Effects of myofascial technique in patients with subacute whiplash associated disorders: a pilot study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;47(4):561-8. Epub 20110728. [PubMed]

- Kamani NC, Poojari S, Prabu RG. The influence of fascial manipulation on function, ankle dorsiflexion range of motion and postural sway in individuals with chronic ankle instability. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2021;27:216-21. Epub 20210402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biz C, Stecco C, Fantoni I, Aprile G, Giacomini S, Pirri C, et al. Fascial Manipulation Technique in the Conservative Management of Morton's Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15). Epub 20210727. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekito F, Pintucci M, Pirri C, Ribeiro de Moraes Rego M, Cardoso M, Soares Paixão K, et al. Facial Pain: RCT between Conventional Treatment and Fascial Manipulation(®) for Temporomandibular Disorders. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;9(7). Epub 20220627. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoldo D, Pirri C, Roviaro B, Stecco L, Day JA, Fede C, et al. Pilot Study of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction Treated with a Single Session of Fascial Manipulation(®) Method: Clinical Implications for Effective Pain Reduction. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(7). Epub 20210706. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratelli E, Pintucci M, Cultrera P, Baldini E, Stecco A, Petrocelli A, et al. Conservative treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: comparison between laser therapy and Fascial Manipulation(®). J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(1):113-8. Epub 20140811. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper B, Steinbeck L, Aron A. Fascial manipulation vs. standard physical therapy practice for low back pain diagnoses: A pragmatic study. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2019;23(1):115-21. Epub 20181103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branchini M, Lopopolo F, Andreoli E, Loreti I, Marchand AM, Stecco A. Fascial Manipulation for chronic aspecific low back pain: a single blinded randomized controlled trial. F1000Res. 2015;4:1208. Epub 20151103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busato M, Quagliati C, Magri L, Filippi A, Sanna A, Branchini M, et al. Fascial Manipulation Associated With Standard Care Compared to Only Standard Postsurgical Care for Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pm r. 2016;8(12):1142-50. Epub 20160519. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecco A, Meneghini A, Stern R, Stecco C, Imamura M. Ultrasonography in myofascial neck pain: randomized clinical trial for diagnosis and follow-up. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36(3):243-53. Epub 20130823. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercole B, Antonio S, Julie Ann D, Stecco C. How much time is required to modify a fascial fibrosis? J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(4):318-25. Epub 20100520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan E, Karaduman A, Yakut Y, Aras B, Simsek IE, Yaglý N. The cultural adaptation, reliability and validity of neck disability index in patients with neck pain: a Turkish version study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(11):E362-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootswagers P, Vaes AMM, Hangelbroek R, Tieland M, van Loon LJC, de Groot L. Relative Validity and Reliability of Isometric Lower Extremity Strength Assessment in Older Adults by Using a Handheld Dynamometer. Sports Health. 2022;14(6):899-905. Epub 20220204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentanin AC, de Facio CA, da Silva MMC, Sousa FC, Arcuri JF, Mendes RG, et al. Reliability of Quadriceps Femoris Muscle Strength Assessment Using a Portable Dynamometer and Protocol Tolerance in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Phys Ther. 2021;101(9). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição A, Parraca J, Marinho D, Costa M, Louro H, Silva A, et al. Assessment of isometric strength of the shoulder rotators in swimmers using a handheld dynamometer: a reliability study. Acta Bioeng Biomech. 2018;20(4):113-9. [PubMed]

- Farooq MN, Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Gilani SA, Hafeez A. Urdu version of the neck disability index: a reliability and validity study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):149. Epub 20170408. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross A, Kay TM, Paquin JP, Blanchette S, Lalonde P, Christie T, et al. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1(1):Cd004250. Epub 20150128. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent K, Maigne JY, Fischhoff C, Lanlo O, Dagenais S. Systematic review of manual therapies for nonspecific neck pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80(5):508-15. Epub 20121116. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corp N, Mansell G, Stynes S, Wynne-Jones G, Morsø L, Hill JC, et al. Evidence-based treatment recommendations for neck and low back pain across Europe: A systematic review of guidelines. Eur J Pain. 2021;25(2):275-95. Epub 20201112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prablek M, Gadot R, Xu DS, Ropper AE. Neck Pain: Differential Diagnosis and Management. Neurol Clin. 2023;41(1):77-85. Epub 20221029. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlukiewicz M, Kochan M, Niewiadomy P, Szuścik-Niewiadomy K, Taradaj J, Król P, et al. Fascial Manipulation Method Is Effective in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain, but the Treatment Protocol Matters: A Randomised Control Trial-Preliminary Report. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15). Epub 20220804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja GP, Bhat NS, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Gangavelli R, Davis F, Shankar R, et al. Effectiveness of deep cervical fascial manipulation and yoga postures on pain, function, and oculomotor control in patients with mechanical neck pain: study protocol of a pragmatic, parallel-group, randomized, controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):574. Epub 20210828. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burk C, Perry J, Lis S, Dischiavi S, Bleakley C. Can Myofascial Interventions Have a Remote Effect on ROM? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sport Rehabil. 2020;29(5):650-6. Epub 20191018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins JF, Nitz AJ, Hoch MC. Dry needling equilibration theory: A mechanistic explanation for enhancing sensorimotor function in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37(6):672-81. Epub 20190716. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monjo F, Shemmell J. Probing the neuromodulatory gain control system in sports and exercise sciences. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2020;53:102442. Epub 20200707. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins B, Schultheiß J, Rafuna A, Hintze S, Meinke P, Schoser B, et al. Degeneration of muscle spindles in a murine model of Pompe disease. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6555. Epub 20230421. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan P, Monti E, Bondí M, Fan C, Stecco C, Narici M, et al. Alterations of Extracellular Matrix Mechanical Properties Contribute to Age-Related Functional Impairment of Human Skeletal Muscles. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11). Epub 20200602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan C, Pirri C, Fede C, Guidolin D, Biz C, Petrelli L, et al. Age-Related Alterations of Hyaluronan and Collagen in Extracellular Matrix of the Muscle Spindles. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1). Epub 20211224. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowman MK, Schmidt TA, Raghavan P, Stecco A. Viscoelastic Properties of Hyaluronan in Physiological Conditions. F1000Res. 2015;4:622. Epub 20150825. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).