Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Sarcopenia and muscle mass loss are critical factors influencing the recovery of patients in intensive care units (ICU). Intensive care unit-acquired weakness (ICUAW) is a prevalent condition that exacerbates the challenges faced by critically ill patients, leading to prolonged immobility and disability. These complications are often part of the post-intensive care syndrome, which affects patients' long-term quality of life. Although nutritional support plays a significant role in the recovery process, early mobilization and rehabilitation are essential components in preventing and mitigating muscle loss. This review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of combined early mobilization and nutritional interventions in improving outcomes related to muscle weakness in ICU patients, focusing on clinical evidence and practical strategies for optimizing recovery.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

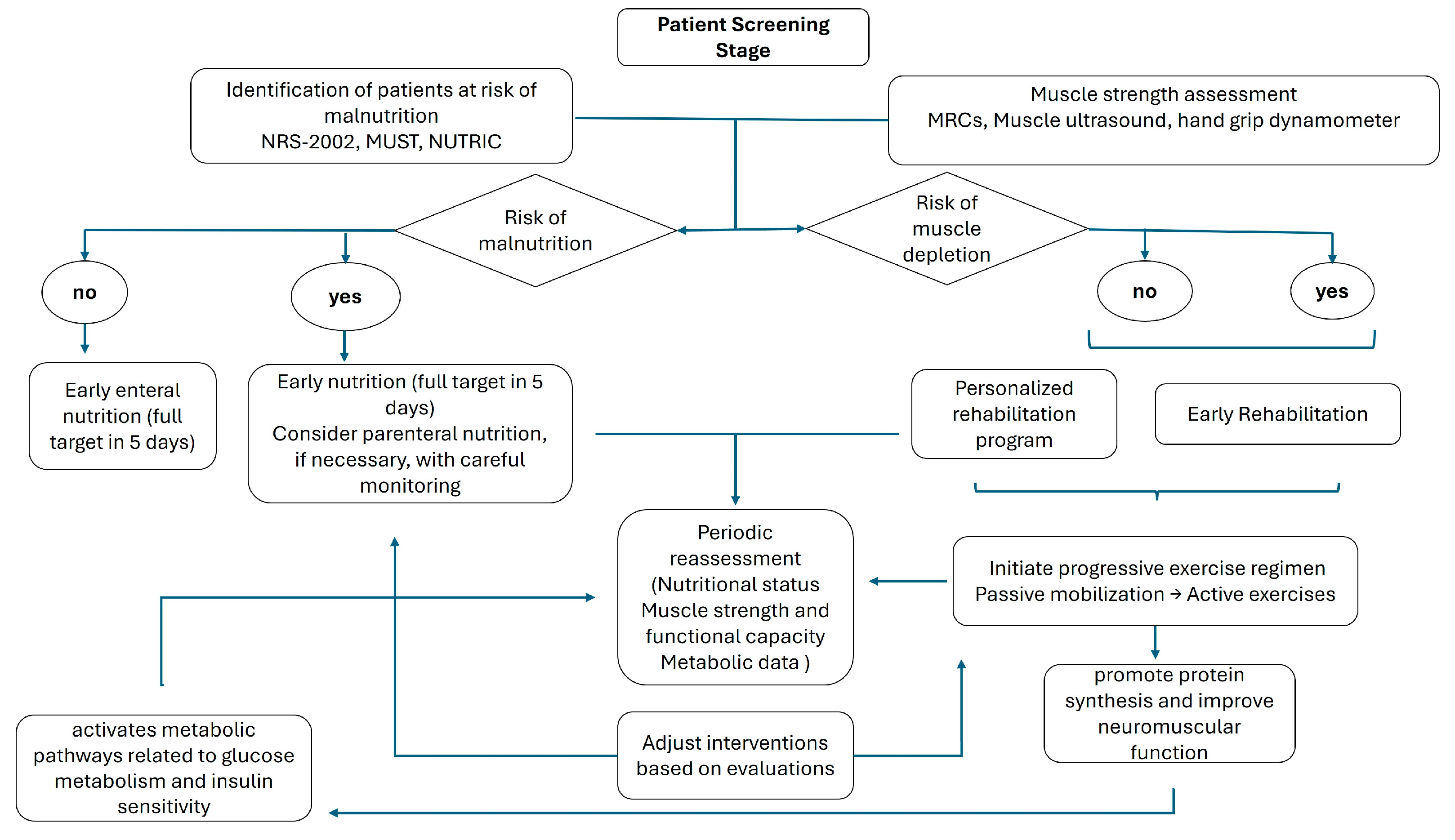

2. Assessment of Nutritional and Physical Status in ICU

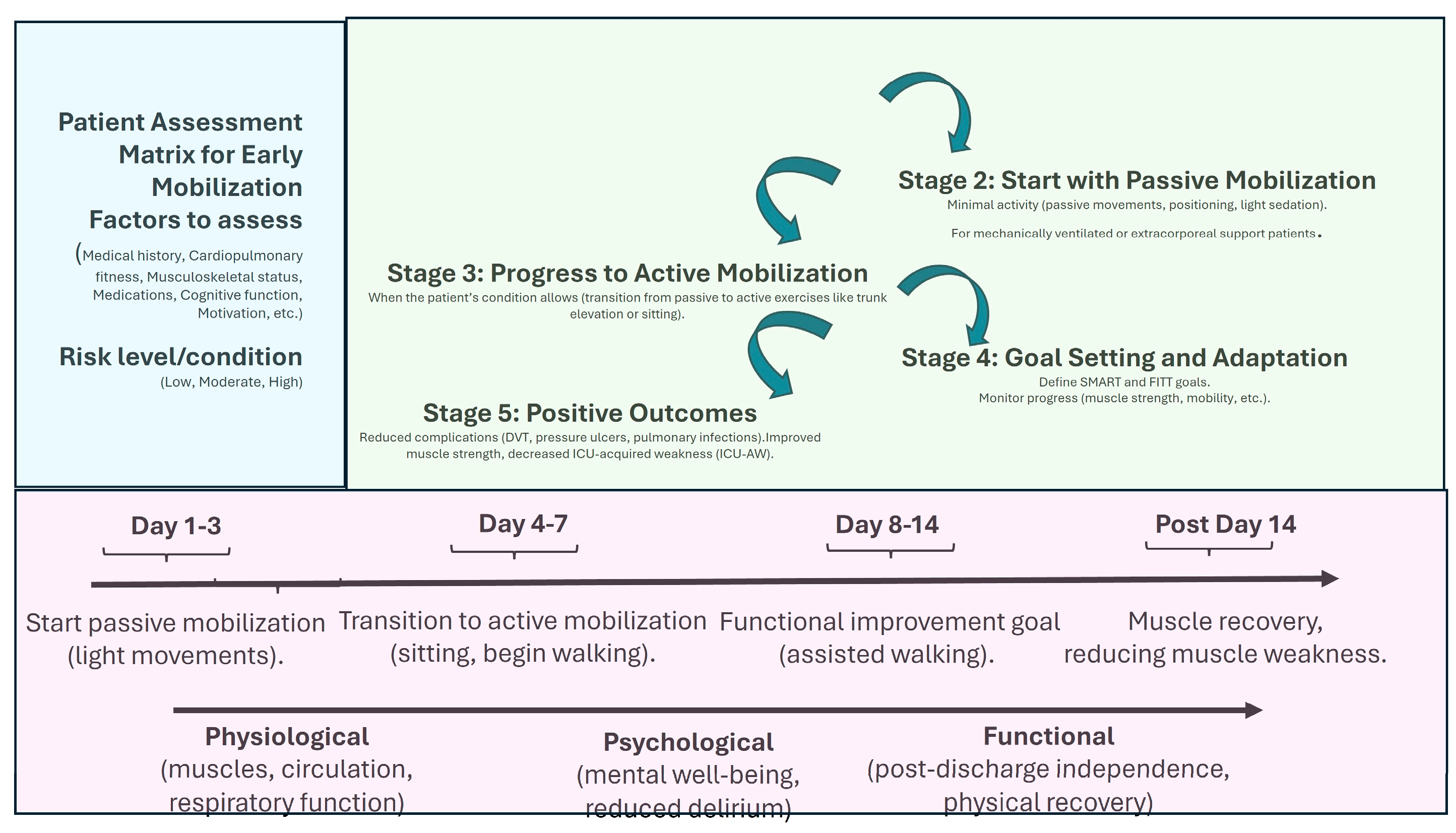

3. Benefits of Early Mobilization in ICU

3.1. Preservation of Muscle Mass and Function

3.2. Improved Functional Outcomes

3.3. Challenges in Implementation

4. Figures, Tables and Schemes

| Study | Patients | Design | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hermans et al.[3] | 415 ICU patients | cohort study and propensity-matched analysis | ICUAW Exacerbates acute health complications, elevates healthcare costs, and is associated with increased mortality rates within one year. The duration and intensity of weakness at the time of ICU discharge are linked to a further rise in one-year mortality rates. |

| Bragança et al. [33] | 45 ICU patients | prospective single center cohort study | Handgrip strength demonstrated a strong correlation with the MRC criteria for diagnosing ICUAW. ICUAW was linked to an increased duration of mechanical ventilation, extended ICU stays, and longer hospital admissions over a six-month period. No significant differences in mortality rates were observed |

| Fazzini et al. [37] | 3251 patients | systematic review and meta-analysis | During the initial week of critical illness, patients typically lose about 2% of their muscle mass each day, with continued reductions in muscle mass throughout their time in the ICU. Additionally, approximately 50% of critically ill patients develop ICU-acquired weakness. |

| Zhou et al. [61] | 150 ICU patients | prospective, dual center, randomized controlled trial | Both early mobilization and early mobilization with nutrition demonstrated beneficial effects. Both interventions may result in a reduced incidence of ICUAW and enhanced functional independence compared to standard care. |

| Zang et al. [44] | 1941 patients | Meta-analysis | Early mobilization proved effective in preventing the development of ICUAW, reducing both ICU and hospital lengths of stay, and enhancing functional mobility. |

| Schweickert et al. [51] | 104 ICU patients | Randomized controlled trial | A comprehensive rehabilitation strategy led to improved functional outcomes at the time of hospital discharge, a reduced duration of delirium, and an increased number of ventilator-free days in comparison to standard care. |

| Casaer et al. [62] | 4640 ICU patients | Randomized multicenter trial ( early-initiation VS late-initiation) | Patients in the late-initiation group experienced a relative increase in the likelihood of being discharged alive. This group also showed a relative decrease of about 10% in the proportion of patients requiring more than two days of mechanical ventilation; the late initiation of parenteral nutrition was associated with a quicker recovery and fewer complications compared to early initiation. |

| Heyland et al. [63] | 1301 ICU patients | multicenter, randomized trial | Administering higher protein doses to mechanically ventilated critically ill patients did not enhance the time to alive discharge from the hospital. A subgroup analysis indicated that increased protein intake was especially detrimental for patients with acute kidney injury and higher baseline organ failure scores. |

| Nakamura et al. [64] | 117 ICU patients | Randomized controlled trial | The loss of femoral muscle was significantly lower in the high-protein group compared to the medium-protein group only with active early mobilization. |

| De Azevedo et al. [65] | 181 ICU patients | prospective, randomized controlled trial | The physical component summary was significantly higher in the high-protein and exercise group at both 3 months and 6 months. The control group exhibited markedly higher mortality rates. |

| Jones et al. [66] | 93 ICU patients | Randomized controlled trial | Patients who received enhanced physiotherapy and structured exercise and glutamine and essential amino acid mixture demonstrated the greatest improvements in the 6-minute walking test. |

| Patel et al. [67] | 104 patients | secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial | Logistic regression analyses indicated that early mobilization and higher insulin doses were effective in preventing the occurrence of ICU-acquired weakness, independent of established risk factors for weakness. |

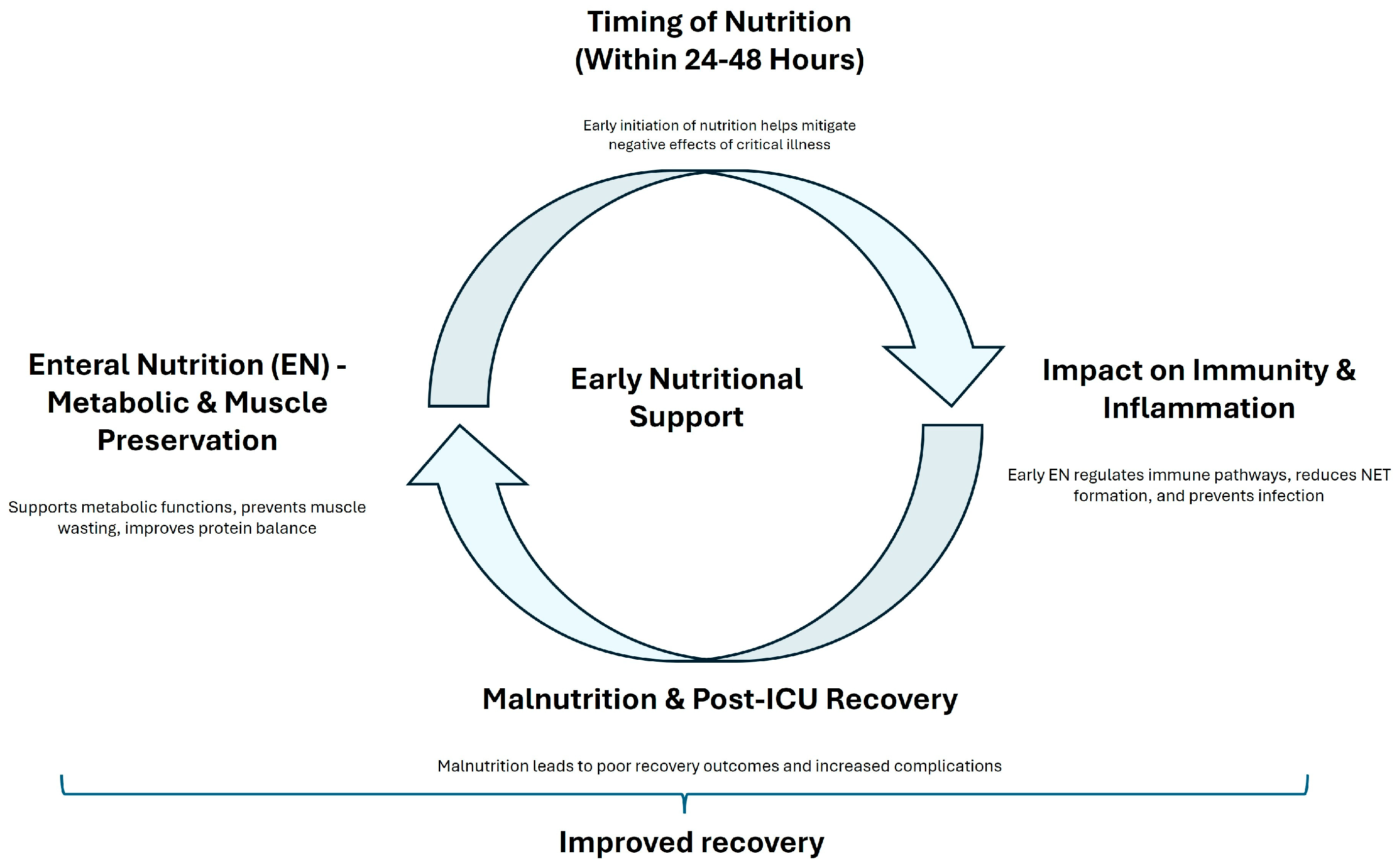

5. Benefits of Early Nutrition in ICU

6. The Combined Effect of Early Mobilization and Nutrition on ICUAW

6.1. Synergistic Muscle Preservation

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ICUAW | Intensive care Unit acquired weakness |

| PICS | post-intensive care syndrome |

| NETs | neutrophil extracellular traps |

References

- Lad, H.; Saumur, T.M.; Herridge, M.S.; Dos Santos, C.C.; Mathur, S.; Batt, J.; Gilbert, P.M. Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness: Not Just Another Muscle Atrophying Condition. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xi, X. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Neurol Scand 2018, 138, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, G.; Van Mechelen, H.; Clerckx, B.; Vanhullebusch, T.; Mesotten, D.; Wilmer, A.; Casaer, M.P.; Meersseman, P.; Debaveye, Y.; Van Cromphaut, S.; et al. Acute Outcomes and 1-Year Mortality of Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness. A Cohort Study and Propensity-Matched Analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014, 190, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thille, A.W.; Boissier, F.; Muller, M.; Levrat, A.; Bourdin, G.; Rosselli, S.; Frat, J.-P.; Coudroy, R.; Vivier, E. Role of ICU-Acquired Weakness on Extubation Outcome among Patients at High Risk of Reintubation. Crit Care 2020, 24, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.-W.; Chou, M.-Y.; Iijima, K.; Jang, H.C.; Kang, L.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020, 21, 300–307.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. GLIM Criteria for the Diagnosis of Malnutrition - A Consensus Report from the Global Clinical Nutrition Community. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.; Degens, H.; Li, M.; Salviati, L.; Lee, Y. il; Thompson, W.; Kirkland, J.L.; Sandri, M. Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 427–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligthart-Melis, G.C.; Luiking, Y.C.; Kakourou, A.; Cederholm, T.; Maier, A.B.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E. Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Malnutrition Frequently (Co-)Occur in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020, 21, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewoude, M.F.J.; Alish, C.J.; Sauer, A.C.; Hegazi, R.A. Malnutrition-Sarcopenia Syndrome: Is This the Future of Nutrition Screening and Assessment for Older Adults? J Aging Res 2012, 2012, 651570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Cherubini, A.; Cesari, M.; Calvani, R.; Tosato, M.; Sisto, A.; Martone, A.M.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. Sarcopenia and Frailty: From Theoretical Approach into Clinical Practice. European Geriatric Medicine 2016, 7, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaafer, O.U.; Zimmers, T.A. The Nutritional Challenges of Cancer Cachexia. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2021, 45, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Bhuachalla, É.B.; Daly, L.E.; Power, D.G.; Cushen, S.J.; MacEneaney, P.; Ryan, A.M. Computed Tomography Diagnosed Cachexia and Sarcopenia in 725 Oncology Patients: Is Nutritional Screening Capturing Hidden Malnutrition? J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthucheary, Z.A.; Rawal, J.; McPhail, M.; Connolly, B.; Ratnayake, G.; Chan, P.; Hopkinson, N.S.; Phadke, R.; Dew, T.; Sidhu, P.S.; et al. Acute Skeletal Muscle Wasting in Critical Illness. JAMA 2013, 310, 1591–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.M.; Landi, F.; Chew, S.T.H.; Atherton, P.J.; Molinger, J.; Ruck, T.; Gonzalez, M.C. Advances in Muscle Health and Nutrition: A Toolkit for Healthcare Professionals. Clin Nutr 2022, 41, 2244–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, N.; Venturelli, E.; Vagheggini, G.; Clini, E. Rehabilitation, Weaning and Physical Therapy Strategies in Chronic Critically Ill Patients. Eur Respir J 2012, 39, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawal, G.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, R. Post-Intensive Care Syndrome: An Overview. J Transl Int Med 2017, 5, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, K.; Lin, F.; Mitchell, M.L.; White, H. Early Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit: An Integrative Literature Review. Aust Crit Care 2015, 28, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo-Gonzalez, J.C.; Pichard, C.; Preiser, J.-C.; et al. ESPEN Practical and Partially Revised Guideline: Clinical Nutrition in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin Nutr 2023, 42, 1671–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, U. Nutritional Laboratory Markers in Malnutrition. J Clin Med 2019, 8, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pereira, S.L.; Luo, M.; Matheson, E.M. Evaluation of Blood Biomarkers Associated with Risk of Malnutrition in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Alhazzani, W.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.P.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo, J.C.; Pichard, C.; et al. ESPEN Guideline on Clinical Nutrition in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 48–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Chavarro, B.C.; Molina-Recio, G.; Assis Reveiz, J.K.; Romero-Saldaña, M. Factors Associated with Nutritional Risk Assessment in Critically Ill Patients Using the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST). J Clin Med 2024, 13, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coruja, M.K.; Cobalchini, Y.; Wentzel, C.; Fink, J. da S. Nutrition Risk Screening in Intensive Care Units: Agreement Between NUTRIC and NRS 2002 Tools. Nutr Clin Pract 2020, 35, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, M.; Yildirim, Z.S.; Deniz, M. Effect of the Modified NUTRIC Score in Predicting the Prognosis of Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Units. BMC Anesthesiol 2024, 24, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wełna, M.; Adamik, B.; Kübler, A.; Goździk, W. The NUTRIC Score as a Tool to Predict Mortality and Increased Resource Utilization in Intensive Care Patients with Sepsis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodpoor, A.; Sanaie, S.; Sarfaraz, T.; Shadvar, K.; Fattahi, V.; Hamishekar, H.; Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Samim, A.; Rahimi-Bashar, F. Prognostic Values of Modified NUTRIC Score to Assess Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Units: Prospective Observational Study. BMC Anesthesiology 2023, 23, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, P.; Alasmar, M.; McLaughlin, J.; Ang, Y.; McPhee, J.; Heire, P.; Sultan, J. The Current Use of Ultrasound to Measure Skeletal Muscle and Its Ability to Predict Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2298–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbrello, M.; Brogi, E.; Formenti, P.; Corradi, F.; Forfori, F. Ultrasonographic Features of Muscular Weakness and Muscle Wasting in Critically Ill Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, P.; Umbrello, M.; Coppola, S.; Froio, S.; Chiumello, D. Clinical Review: Peripheral Muscular Ultrasound in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care 2019, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.P.; Teo, K.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Avezum, A.; Orlandini, A.; Seron, P.; Ahmed, S.H.; Rosengren, A.; Kelishadi, R.; et al. Prognostic Value of Grip Strength: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study. Lancet 2015, 386, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, B.A.; Jones, G.D.; Curtis, A.A.; Murphy, P.B.; Douiri, A.; Hopkinson, N.S.; Polkey, M.I.; Moxham, J.; Hart, N. Clinical Predictive Value of Manual Muscle Strength Testing during Critical Illness: An Observational Cohort Study. Crit Care 2013, 17, R229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragança, R.D.; Ravetti, C.G.; Barreto, L.; Ataíde, T.B.L.S.; Carneiro, R.M.; Teixeira, A.L.; Nobre, V. Use of Handgrip Dynamometry for Diagnosis and Prognosis Assessment of Intensive Care Unit Acquired Weakness: A Prospective Study. Heart Lung 2019, 48, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singam, A. Mobilizing Progress: A Comprehensive Review of the Efficacy of Early Mobilization Therapy in the Intensive Care Unit. Cureus 16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Tronstad, O.; Flaws, D.; Churchill, L.; Jones, A.Y.M.; Nakamura, K.; Fraser, J.F. From Bedside to Recovery: Exercise Therapy for Prevention of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. J Intensive Care 2024, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, C.L.; Berney, S.; Harrold, M.; Saxena, M.; Bellomo, R. Clinical Review: Early Patient Mobilization in the ICU. Critical Care 2013, 17, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazzini, B.; Märkl, T.; Costas, C.; Blobner, M.; Schaller, S.J.; Prowle, J.; Puthucheary, Z.; Wackerhage, H. The Rate and Assessment of Muscle Wasting during Critical Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care 2023, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimune, H.; Stanford, J.A.; Mori, Y. Role of Exercise in Maintaining the Integrity of the Neuromuscular Junction. Muscle Nerve 2014, 49, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimune, H.; Numata, T.; Chen, J.; Aoki, Y.; Wang, Y.; Starr, M.P.; Mori, Y.; Stanford, J.A. Active Zone Protein Bassoon Co-Localizes with Presynaptic Calcium Channel, Modifies Channel Function, and Recovers from Aging Related Loss by Exercise. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrasseur, N.K.; Coté, G.M.; Miller, T.A.; Fielding, R.A.; Sawyer, D.B. Regulation of Neuregulin/ErbB Signaling by Contractile Activity in Skeletal Muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003, 284, C1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Lang, J.K.; Haines, K.J.; Skinner, E.H.; Haines, T.P. Physical Rehabilitation in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med 2022, 50, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolo, G.; Tipton, K.D.; Klein, S.; Wolfe, R.R. An Abundant Supply of Amino Acids Enhances the Metabolic Effect of Exercise on Muscle Protein. Am J Physiol 1997, 273, E122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, K.; Chen, B.; Wang, M.; Chen, D.; Hui, L.; Guo, S.; Ji, T.; Shang, F. The Effect of Early Mobilization in Critically Ill Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Nurs Crit Care 2020, 25, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Mi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, X.; Gan, R.; Mu, S. Effects of the High-Intensity Early Mobilization on Long-Term Functional Status of Patients with Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Res Pract 2024, 2024, 4118896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Cao, J.; Jiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Song, B.; Jin, J.; et al. The Association between Major Complications of Immobility during Hospitalization and Quality of Life among Bedridden Patients: A 3 Month Prospective Multi-Center Study. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0205729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezidi, M.; Guérin, C. Effects of Patient Positioning on Respiratory Mechanics in Mechanically Ventilated ICU Patients. Ann Transl Med 2018, 6, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dorzi, H.M.; AlQahtani, S.; Al-Dawood, A.; Al-Hameed, F.M.; Burns, K.E.A.; Mehta, S.; Jose, J.; Alsolamy, S.J.; Abdukahil, S.A.I.; Afesh, L.Y.; et al. Association of Early Mobility with the Incidence of Deep-Vein Thrombosis and Mortality among Critically Ill Patients: A Post Hoc Analysis of PREVENT Trial. Critical Care 2023, 27, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, M.A.; Teasell, R.W.; Wolfe, D.L.; Keast, D.; Mortenson, W.B.; Aubut, J.-A. A Systematic Review of Therapeutic Interventions for Pressure Ulcers Following Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009, 90, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Hatakeyama, J.; Kondo, Y.; Hifumi, T.; Sakuramoto, H.; Kawasaki, T.; Taito, S.; Nakamura, K.; Unoki, T.; Kawai, Y.; et al. Post-Intensive Care Syndrome: Its Pathophysiology, Prevention, and Future Directions. Acute Med Surg 2019, 6, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mart, M.F.; Williams Roberson, S.; Salas, B.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Ely, E.W. Prevention and Management of Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2021, 42, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweickert, W.D.; Pohlman, M.C.; Pohlman, A.S.; Nigos, C.; Pawlik, A.J.; Esbrook, C.L.; Spears, L.; Miller, M.; Franczyk, M.; Deprizio, D.; et al. Early Physical and Occupational Therapy in Mechanically Ventilated, Critically Ill Patients: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2009, 373, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaparthi, G.K.; Gatty, A.; Samuel, S.R.; Amaravadi, S.K. Effectiveness, Safety, and Barriers to Early Mobilization in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Res Pract 2020, 2020, 7840743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Cao, L.; Ye, L.; Song, W. Early Mobilization for Critically Ill Patients. Respir Care 2023, 68, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genc, A.; Koca, U.; Gunerli, A. What Are the Hemodynamic and Respiratory Effects of Passive Limb Exercise for Mechanically Ventilated Patients Receiving Low-Dose Vasopressor/Inotropic Support? Crit Care Nurs Q 2014, 37, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morisawa, T.; Takahashi, T.; Sasanuma, N.; Mabuchi, S.; Takeda, K.; Hori, N.; Ohashi, N.; Ide, T.; Domen, K.; Nishi, S. Passive Exercise of the Lower Limbs and Trunk Alleviates Decreased Intestinal Motility in Patients in the Intensive Care Unit after Cardiovascular Surgery. J Phys Ther Sci 2017, 29, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrinal, C.; Combret, Y.; Prieur, G.; Robledo Quesada, A.; Bonnevie, T.; Gravier, F.E.; Dupuis Lozeron, E.; Frenoy, E.; Contal, O.; Lamia, B. Comparison of Exercise Intensity during Four Early Rehabilitation Techniques in Sedated and Ventilated Patients in ICU: A Randomised Cross-over Trial. Crit Care 2018, 22, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, K.R.; Dafoe, S.; Jesudason, C.S.; McDonald, T.M.; Callisto, R.J. Passive Movements Do Not Appear to Prevent or Reduce Joint Stiffness in Medium to Long-Stay ICU Patients: A Randomized, Controlled, Within-Participant Trial. Crit Care Explor 2023, 5, e1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, L.A.; Lewis, S.R.; Schofield-Robinson, O.J.; Drummond, A.; Langhorne, P. Occupational Therapy for Adults with Problems in Activities of Daily Living after Stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 2017, CD003585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovend’Eerdt, T.J.H.; Botell, R.E.; Wade, D.T. Writing SMART Rehabilitation Goals and Achieving Goal Attainment Scaling: A Practical Guide. Clin Rehabil 2009, 23, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnet, K.; Kelsch, E.; Zieff, G.; Moore, J.B.; Stoner, L. How Fitting Is F.I.T.T.?: A Perspective on a Transition from the Sole Use of Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type in Exercise Prescription. Physiol Behav 2019, 199, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yu, L.; Fan, Y.; Shi, B.; Wang, X.; Chen, T.; Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; et al. Effect of Early Mobilization Combined with Early Nutrition on Acquired Weakness in Critically Ill Patients (EMAS): A Dual-Center, Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0268599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaer, M.P.; Mesotten, D.; Hermans, G.; Wouters, P.J.; Schetz, M.; Meyfroidt, G.; Van Cromphaut, S.; Ingels, C.; Meersseman, P.; Muller, J.; et al. Early versus Late Parenteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med 2011, 365, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyland, D.K.; Patel, J.; Compher, C.; Rice, T.W.; Bear, D.E.; Lee, Z.-Y.; González, V.C.; O’Reilly, K.; Regala, R.; Wedemire, C.; et al. The Effect of Higher Protein Dosing in Critically Ill Patients with High Nutritional Risk (EFFORT Protein): An International, Multicentre, Pragmatic, Registry-Based Randomised Trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Nakano, H.; Naraba, H.; Mochizuki, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Sonoo, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Morimura, N. High Protein versus Medium Protein Delivery under Equal Total Energy Delivery in Critical Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, J.R.A.; Lima, H.C.M.; Frota, P.H.D.B.; Nogueira, I.R.O.M.; de Souza, S.C.; Fernandes, E.A.A.; Cruz, A.M. High-Protein Intake and Early Exercise in Adult Intensive Care Patients: A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Impact on Functional Outcomes. BMC Anesthesiol 2021, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Eddleston, J.; McCairn, A.; Dowling, S.; McWilliams, D.; Coughlan, E.; Griffiths, R.D. Improving Rehabilitation after Critical Illness through Outpatient Physiotherapy Classes and Essential Amino Acid Supplement: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Crit Care 2015, 30, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.K.; Pohlman, A.S.; Hall, J.B.; Kress, J.P. Impact of Early Mobilization on Glycemic Control and ICU-Acquired Weakness in Critically Ill Patients Who Are Mechanically Ventilated. Chest 2014, 146, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reignier, J.; Rice, T.W.; Arabi, Y.M.; Casaer, M. Nutritional Support in the ICU. BMJ 2025, 388, e077979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T.A.; O’Keefe, S.J.; Callanan, M.; Marks, T. Effect of Severe Undernutrition and Subsequent Refeeding on Gut Mucosal Protein Fractional Synthesis in Human Subjects. Nutrition 2007, 23, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ren, H.; Hong, Z.; Wang, C.; Zheng, T.; Ren, Y.; Chen, K.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Gu, G.; et al. Early Enteral Nutrition Preserves Intestinal Barrier Function through Reducing the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Critically Ill Surgical Patients. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 8815655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, J.; Walters, K.; Avgerinou, C. How Effective Is Nutrition Education Aiming to Prevent or Treat Malnutrition in Community-Dwelling Older Adults? A Systematic Review. Eur Geriatr Med 2019, 10, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunst, J.; Casaer, M.P.; Preiser, J.-C.; Reignier, J.; Van den Berghe, G. Toward Nutrition Improving Outcome of Critically Ill Patients: How to Interpret Recent Feeding RCTs? Crit Care 2023, 27, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, L.-A.S.; Kouw, I.W.K.; Summers, M.J.; Weinel, L.M.; Gluck, S.; Raith, E.; Slobodian, P.; Soenen, S.; Deane, A.M.; van Loon, L.J.C.; et al. Muscle Protein Synthesis after Protein Administration in Critical Illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 206, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisey, L.L.; Merriweather, J.L.; Drover, J.W. The Role of Nutrition Rehabilitation in the Recovery of Survivors of Critical Illness: Underrecognized and Underappreciated. Crit Care 2022, 26, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villet, S.; Chiolero, R.; Bollmann, M.; Revelly, J.-P.; N, M.-C.; Delarue, J.; Berger, M. Negative Impact of Hypocaloric Feeding and Energy Balance on Clinical Outcome in ICU Patients. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2005, 24, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, P.J.; Smith, K. Muscle Protein Synthesis in Response to Nutrition and Exercise. J Physiol 2012, 590, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wackerhage, H.; Rennie, M.J. How Nutrition and Exercise Maintain the Human Musculoskeletal Mass. J Anat 2006, 208, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasiakos, S.M. Exercise and Amino Acid Anabolic Cell Signaling and the Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Mass. Nutrients 2012, 4, 740–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wu, D.; Birukov, K.G. Mechanosensing and Mechanoregulation of Endothelial Cell Functions. Compr Physiol 2019, 9, 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Zhou, C.; Yan, Q.; Tan, Z.; Kang, J.; Tang, S. Elucidating the Underlying Mechanism of Amino Acids to Regulate Muscle Protein Synthesis: Effect on Human Health. Nutrition 2022, 103–104, 111797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).