1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), known as COVID-19, caused a global pandemic, declared in March 2020, leading to millions of fatalities worldwide. As of April 2025, there have been over 777 million cases, resulting in the death of 7.1 million people, worldwide. In Brazil, approximately 39 million cases have been reported, leading to 715 thousand deaths [

1]. Sedentary individuals, older adults, and those with pre-existing comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and respiratory disorders, were more susceptible to developing severe acute respiratory infections and, in many cases, succumbed to the disease [

2,

3].

The clinical manifestations of the disease include, but are not limited to, fever, severe inflammation of the respiratory tract, cough, dyspnea, fatigue. Furthermore, skeletal muscle tissue may also be negatively affected by COVID-19. Histopathological alterations, such as fiber necrosis mediated by inflammation with macrophage infiltration, and motoneuron degeneration are possible mechanisms of skeletal muscle damage after the coronavirus invades it [

4]. This damage may lead to medium- and long-term muscle weakness and exercise intolerance. Consequently, functional performance and quality of life may diminish during and post-acute COVID-19.

In addition to acute infection effects, a subset of individuals continues to experience persistent symptoms beyond infection cessation [

5], referred to as Long COVID. According to Ely and colleagues (2024), the definition chosen by NASEM (

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine) for Long COVID is: “a chronic condition associated with infection after SARS-CoV-2 infection that has symptoms present for at least three months continuously, with relapses and remissions, or progressively affecting one or more organs” [

6]. The global prevalence of Long COVID (considering only studies that evaluated symptom persistence between 90 and 120 days after acute infection) is 0.32 (95% CI, .14–.57) for 90 days, and 0.49 (95% CI, .40–.59) for 120 days [

7]. Following this estimate and the data reported by the WHO, the number of people with Long COVID now would be approximately between 248 and 380 million worldwide. In Brazil, this number would be approximately between 12 and 19 million people.

Long COVID is a heterogeneous, multisystemic condition characterized by a diverse range of persistent symptoms, including chest pain, cough, dizziness, cognitive and autonomic dysfunctions that may negatively affect quality of life [

8,

9]. The skeletal muscle damage can result in prolonged weakness, exercise intolerance, and fatigue. These are amongst the most reported Long COVID symptoms, affecting approximately 45% of individuals with Long COVID [

10].

Skeletal muscle tissue plays a critical role in several physiological processes, including glucose regulation, immune response, basal metabolic rate, and protein synthesis [

11]. Hence, muscle mass gain and strengthening strategies in Long COVID are critical for optimizing rehabilitation. Resistance training (RT) represents a promising intervention for the rehabilitation of individuals with Long COVID, given it is a highly effective exercise modality for promoting muscle strength and hypertrophy, improving functional performance, and optimizing health parameters in a wide range of healthy and clinical populations [

12].

While existing evidence supports physical exercise as a potential rehabilitation strategy for individuals with Long COVID [

13], the role of resistance training (RT) as a primary intervention remains unclear, primarily due to concerns over exercise tolerance in this population. Furthermore, although RT modalities, such as elastic bands, have demonstrated positive effects on muscle strength in older adults [

14], their specific impact on individuals with Long COVID has yet to be explored. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of traditional and elastic RT on muscle mass, strength, and several health indicators in individuals with Long COVID.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

This quasi-experimental study included adults (aged 18 years or older), irrespective of sex, who had been physically inactive for at least six months, were non-smokers, and exhibited symptoms potentially related to Long COVID for at least three months following the acute phase of infection. Participants were recruited through both digital and physical advertisements at two universities. The intervention lasted twelve weeks, with measurements of dependent variables taken at baseline, mid-intervention (i.e., six weeks), and following the 12-week intervention. Blood samples were collected at baseline and post-intervention.

Thirteen individuals initially volunteered and provided written informed consent for the study; however, five withdrew (two of them missed sessions due to traveling, and the other three stopped going without providing the reason), leaving eight participants who completed the study. The study adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the institution’s Research Ethics Committee (protocol number: 6.313.134).

Participants were assigned to one of two groups: one performing a traditional resistance training protocol (TRAD; n = 4) and the other performing an elastic resistance training protocol (ELAS; n = 4). The first participant was randomly assigned to one group, and subsequent allocations followed the order of enrolment and sex, ensuring an equal sex distribution in both groups (three females and one male per group for final analysis).

2.2. Resistance Training Protocol

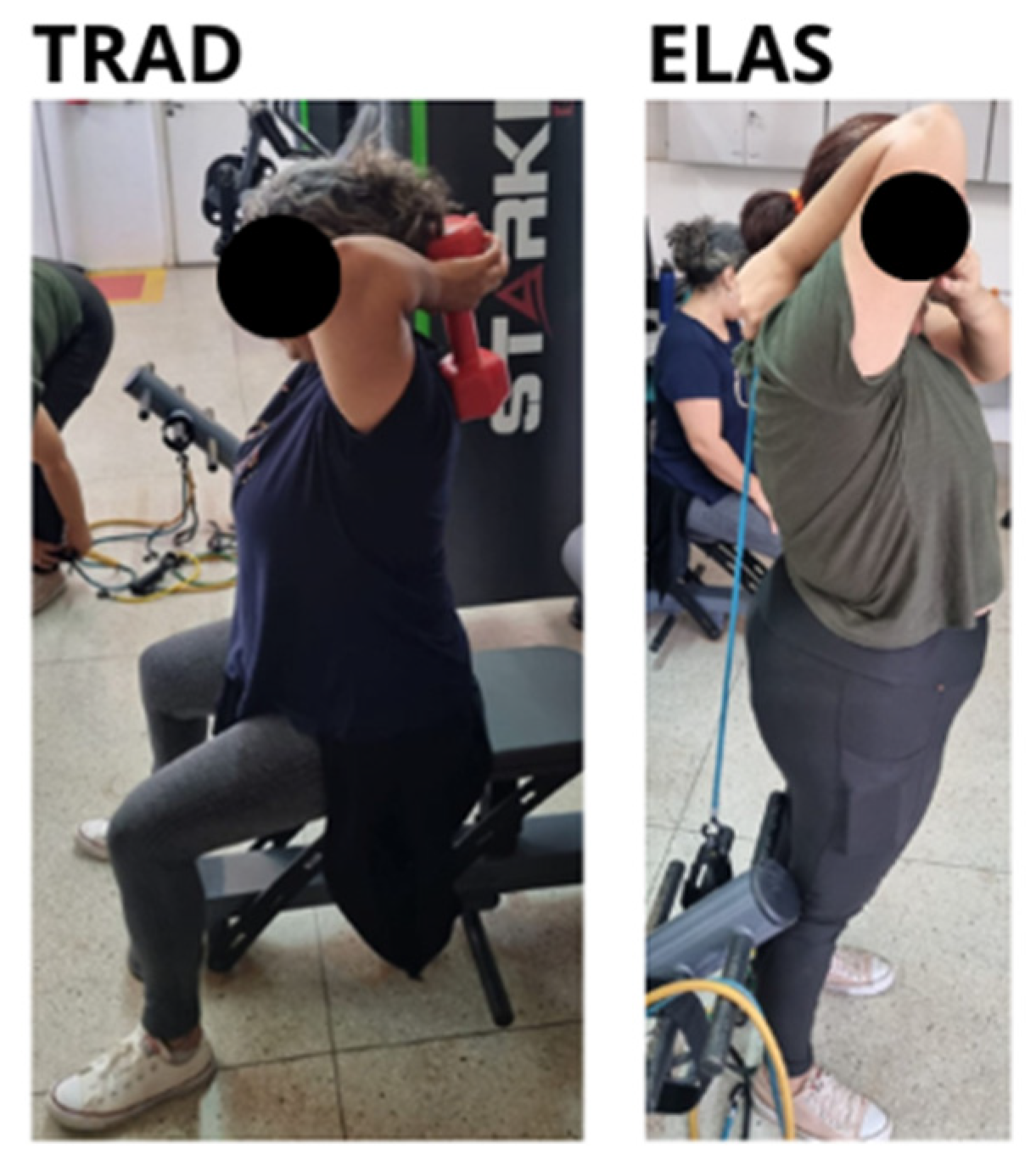

The training protocol for both groups included seven upper and lower limb exercises TRAD group performed the exercise on traditional strength-training machines and dumbbells (Stark™). The exercises were performed in the following order: i) trunk flexion on the ground; ii) bench-press machine; iii) pull-up machine; iv) extension chair; v) elbow extension with dumbbell; vi) elbow flexion with dumbbell; and vii) knee flexor chair. The ELAS group followed the same exercise protocol, with adaptations made for the use of elastic extensors, ensuring the movements were comparable to those in the TRAD group. The abdominal exercise was identical for both groups; however, the pull-up exercise was modified to a rowing exercise for the ELAS group.

Progression of resistance loads a linear approach. During the first six weeks, participants performed two sets of 10 to 12 repetitions per exercise, with intensity between five and six in the OMINI-RES subjective exertion scale. In the final six weeks, participants performed three sets of eight to 10 repetitions per exercise, with intensity between eight and 10 on the perceived exertion scale. The rest-interval between sets and exercises was between one and two minutes. The training volume was equalized between groups.

Figure 1 illustrates the equivalence of the exercises in the two groups.

The oxygen saturation of all participants was monitored during the training sessions, and “desaturation” was considered to be a drop of 3-4% of baseline saturation or less than 94%, which would result in the end of the training session for the participant, as recommended by DeMars et al. (2022) [

15]. No participant in this study had their session terminated early due to desaturation.

2.3. Dependent Variables

The severity and and prevalence of long COVID symptoms were assessed using the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire – COVID (DSQ-COVID) translated to Portuguese and converted into a digital format. The questionnaire results were calculated according to the method recommended by the DSQ-COVID researchers [

16] resulting in a score between 0 and 100 for each symptom. To obtain a single value that could represent all symptoms collectively, the scores of each symptom were summed. This summed score was used to perform the comparisons.

Body composition (body mass, fat mass percentage and muscle mass percentage) was assessed using a tetrapolar bioelectrical impedance device (OMRON HBF-510, OMRON Healthcare Inc. Lake Forest, IL). Height was measured using a portable ultrasonic stadiometer (Inlab

®), and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing body mass by height squared (kg•m

-²). Brachial biceps muscle thickness was assessed by a trained technician using a portable A-type (2,5Mhz) ultrasound device (Body Metrix 200). The measurement was performed in the dominant arm following all manufacturer recommendations [

17].

Handgrip muscle strength (HGS) assessment was performed with a hydraulic hand dynamometer (SAEHAN

®) following literature recommendation [

18]. Each participant performed three sets of three seconds of maximum isometric contraction in the dominant hand, with a 30-second interval between sets. The highest value obtained was used for analysis. Relative handgrip muscle strength (RHGS) was calculated to account for differences in body size and composition [

19] by dividing the HGS value by the BMI. The Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test (5TSTS), Timed Up and Go (TUG), and Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) were assessed as measures of functional performance. The test procedures followed the protocols and guidelines previously described [

20,

21,

22].

Resting blood pressure was measured using a digital oscilometric device (OMRON HEM-7320, OMRON Healthcare Inc. Lake Forest, IL) following minutes of seated rest. Three measurements were taken, with a three-minute interval between each one. The average measurement was adopted as the value for analysis. Blood glucose (Accu-check Active®) and uric acid (Uric Acid Detect TD-4141, ECO Diagnóstica®) were measured after at least eight-hours fasting with portable devices. Capillary blood material was collected from the distal phalanx of the participant’s chosen finger on the non-dominant hand using disposable lancets.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Jamovi statistical package (version 2.3.28), with a significance level set at P < 0.05. Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro Wilk test, and non-parametric tests were applied where appropriate. Initially, a student’s t-test was used to compare dependent variables at baseline. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was then performed to assess within- and between-group differences across three time-points (2 groups x 3 time-points). Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used to identify specific group differences. Additionally, a paired t-test was conducted to compare variables at pre- and post-intervention values for all participants, regardless of group assignment. The deltas of variation of all variables were also analyzed, and Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated. Effect sizes were classified as: 0.2 to 0.5 for a small effect, 0.5 to 0.8 for a moderate effect, and values above 0.8 indicating a large effect.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the sample at baseline. No significant differences were observed between the ELAS or TRAD groups prior to the commencement of the RT intervention.

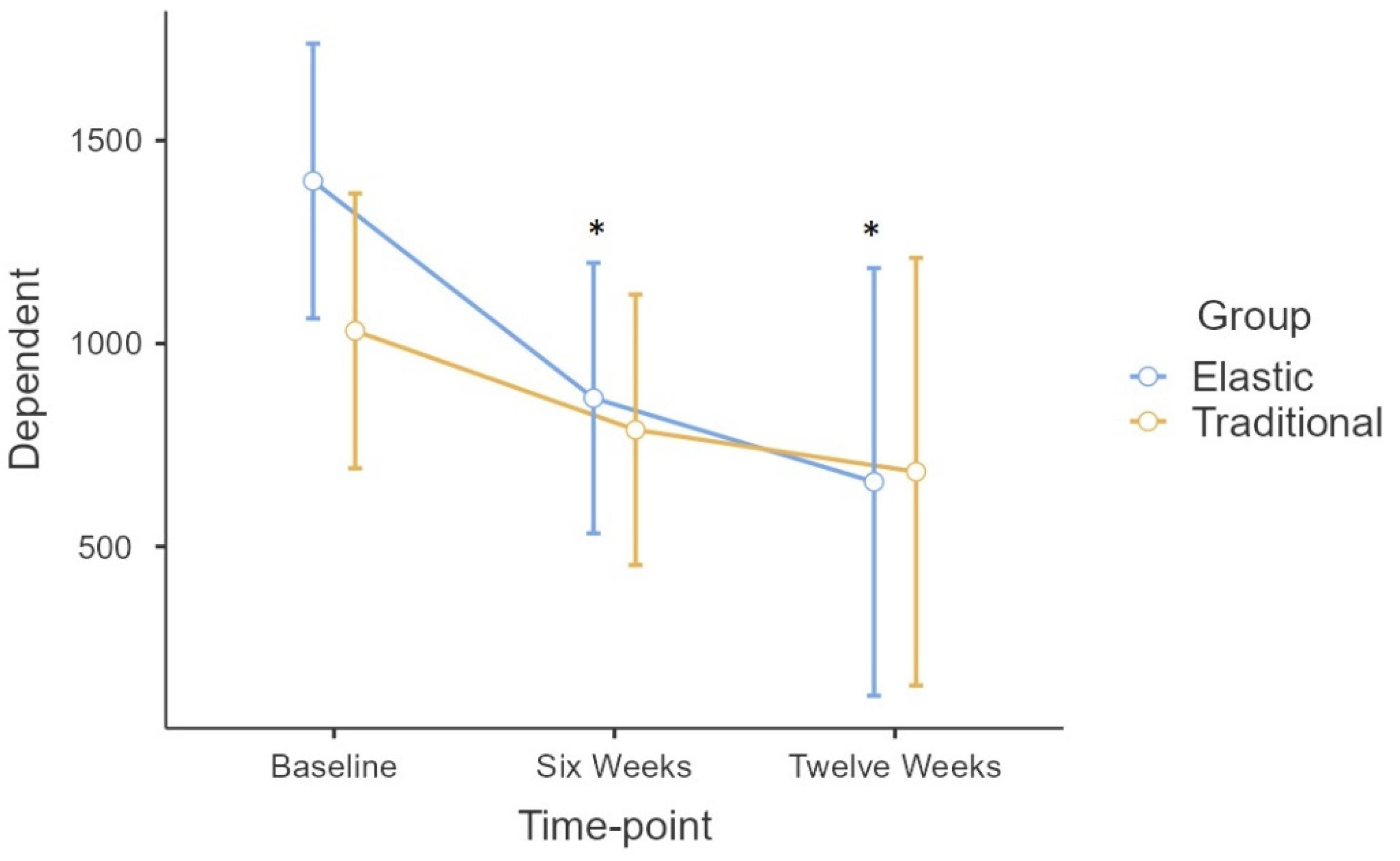

Repeated measures ANOVA showed no statistically significant differences for the Group*Time interaction. A significant time effect (

F = 13.6; p < 0.001) was observed in the long COVID symptom score (DSQ-COVID). Tukey’s

Post-Hoc test demonstrated that the difference in time was found only in the ELAS group between baseline and the six-week time-point (p = 0.043), as well as between the pre- and post-intervention moments (p = 0.045), with no difference between the six-week and post-intervention time-point (

Figure 2).

Given the absence of the Group*Time interaction, a paired T-test was performed to assess the effect of the training intervention in both groups together, regardless of the initial allocation. Systolic blood pressure (SBP), DSQ-COVID score, as well as absolute and relative muscle strength presented significant improvement after the intervention (

Table 2).

Fatigue, bone or joint pain, and memory loss were the most common symptoms experienced by all participants prior to the intervention. The paired t-test did not reveal significant differences between pre- and post-training levels for these symptoms (P > 0.05), although the effect sizes were moderate for all: fatigue (0.76), bone/joint pain (0.72), and memory loss (0.59).

A percentage variation analysis was conducted for all dependent variables, with results presented in

Table 3. The three most prevalent symptoms (fatigue, bone/joint pain, and memory loss) were included in this analysis.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of traditional and elastic RT on muscle mass, strength, and several health indicators in individuals with Long COVID. Participants were classified as overweight and pre-hypertensive, but non-diabetic. The main finding was that no significant group differences were observed. However, a time effect was identified in the symptoms score in the ELAS group. When the groups were analyzed collectively as a single RT group, significant improvements were observed in the DSQ-COVID symptom score, and in muscle strength (absolute and relative). Moreover, percent variation analysis revealed a reduction of approximately 48–53% in the most prevalent symptom scores following the intervention.

The absence of significant differences between groups in this study suggests that both traditional and elastic extensors RT modalities may produce similar effects in the rehabilitation of individuals with long COVID. Notably, a time effect for the DSQ-COVID score was observed only in the ELAS group, highlighting the potential of elastic RT to reduce symptom severity. The beneficial effects of elastic RT are well established. Indeed, a previous meta-analysis demonstrated that RT using elastic bands can significantly increase muscle strength in older adults [

14]. Converse to previous literature in a wide range of healthy and clinical populations [

12], this study did not find that RT enhanced strength or optimized health parameters [

12]. This could, at least in part, be attributed to the small sample size and thus reflect a type II error due to a lack of statistical power. Therefore, the groups were further analyzed as a single RT intervention, regardless of the initial allocation. This approach assumed that, in the absence of a significant Group*Time interaction, traditional and elastic RT provides a similar training stimulus. This revealed significant improvements in SBP (-9.5%), DSQ-COVID score (-45%), as well as in both absolute (+14%) and relative muscle strength (+12%), post-intervention.

Few studies in the literature have evaluated the effects of RT on individuals with Long COVID, but the results of the present study align with existing findings. For example, Ibrahim et al. [

23] assessed handgrip strength and other variables in a sample that performed RT exercises using sandbags, dumbbells, and elastic bands. They reported a remarkable 130% improvement in handgrip strength after six weeks of training. The larger magnitude of strength improvement in Ibrahim and colleagues’ study may be attributed to sample characteristics, as their participants were sarcopenic individuals with chronic kidney disease and Long COVID, representing a more fragile baseline condition.

Another study [

24] assessed static and dynamic strength in older adults with Long COVID. Isometric knee, elbow, and trunk strength, as well as isokinetic knee peak torque of the dominant leg were assessed before and after 8 weeks of traditional RT in that study. The authors found significant increases in isometric strength, irrespective of sex. Percent increases varied from 12.0 to 30.0%. Different from this study, Ramírez-Vélez et al. [

25] showed no significant increase in grip strength after six weeks of progressive RT. Still, they found significant increases in dynamic 1RM (repetition maximum) tests, such as pectoral, leg press, knee extension, and trunk press.

The DSQ-COVID symptom score decreased post-intervention in the present study. Although this reduction did not reach statistical significance, the effect size was moderate, and the magnitude of the reduction was substantial for the total score (-45%), fatigue (-53%), bone or joint pain (-48%), and memory loss (-50%). Notably, when analysing the minimum and maximum score reductions, it was observed that bone or joint pain and memory loss were completely absent in some participants, while fatigue, one of the most prevalent Long COVID symptom [

26], was reduced by more than 87% in a single participant. These findings are of clinical importance. Previous studies using self-reported data have demonstrated significant reductions in several common symptoms related to Long COVID, such as depression, psychological distress, dizziness, equilibrium disorders, perceived muscle weakness, and exercise intolerance [

24,

25]. The results highlight the potential of RT, whether traditional or using elastic extensors, to enhance individuals’ quality of life and overall health.

It is pertinent to note that the significant reduction in SBP observed in the present study may be influenced by one of the participants starting to use anti-hypertensive medication during the training period. However, RT is also known to have a positive effect on blood pressure [

27] and the influence of the training cannot be discounted. With regards to the other dependent variables, no significant changes were observed in functional performance parameters, uric acid, blood glucose, and body composition. This may be attributed, at least in part, to the protocol characteristics, which involved moderate-intensity RT performed twice a week to avoid post-exertional malaise (PEM), a symptom exacerbation that can occur in individuals with Long COVID following exercise [

28]. Additionally, the training duration may have been insufficient to elicit changes in body composition, as muscle hypertrophy tends to occur after more prolonged RT programs (12 weeks on) [

29].

This study has both strengths and limitations. The primary limitation is the small sample size, which resulted in low statistical power. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first Brazilian study to assess the effects of RT in long COVID rehabilitation. The small sample size also allowed a more individual analysis, highlighting the notable clinical relevance of the findings, particularly in relation to the reduction in symptom scores. From an RT perspective, the absence of the squat exercise in the protocol is another limitation. The squat is widely regarded as one of the most effective exercises for improving quality of life due to its ability to engage multiple muscle groups simultaneously [

30]. However, it was intentionally excluded to minimize the risk of PEM, given the uncertainty surrounding the physiological responses of individuals with Long COVID during RT. Lastly, the lack of a control group not undergoing exercise is another limitation of this study.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, RT, whether traditional or using elastic extensors, effectively enhances muscle strength and reduces the severity of Long COVID symptoms, potentially improving overall quality of life. Moreover, RT was demonstrated to be both feasible and safe, as no instances of desaturation or PEM were observed during the intervention. Future studies should explore the impact of RT on functional performance and body composition, utilizing larger sample sizes, more intensive training protocols, and the inclusion of control groups to strengthen the evidence base.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O. and M.D.; methodology and data collection, M.O.; V.C.L.; formal analysis, M.O. and M.D.; data curation, M.O. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, M.O., K.A.M., M.A.D. and R.L.; supervision, M.D.; funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Support Foundation of the Federal District, Brazil (FAPDF), and the APC was funded by the Research Support Foundation of the Federal District, Brazil (FAPDF). Process number 00193.00002363/2022-47.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the University Center UNIEURO (UNIEURO) under the protocol nº 6.313.134 on 20 September 2023 for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RT |

Resistance Training |

| ELAS |

Elastic Group |

| TRAD |

Traditional Exercise Group |

| DSQ |

DePaul Symptom Questionnaire – COVID |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| SBP |

Sistolic Blood Pressure |

| DBP |

Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| 5TST |

Five Times Sit To Stand Test |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go |

| HGS |

Hand Grip Strength |

| RHGS |

Relative Hand Grip Strength |

| 6MW |

Six Minutes Walk |

References

- World Health Organization, ‘WHO COVID-19 dashboard’. Accessed: Mar. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o.

- C. N. S. Oliveira, ‘O dimorfismo sexual e regulação imunoendócrina na COVID-19’, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Ochani et al., ‘COVID-19 pandemic: from origins to outcomes. A comprehensive review of viral pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnostic evaluation, and management’, 2021.

- M. N. Soares et al., ‘Skeletal muscle alterations in patients with acute Covid-19 and post-acute sequelae of Covid-19’, Feb. 01, 2022, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- B. Bigdelou et al., ‘COVID-19 and Preexisting Comorbidities: Risks, Synergies, and Clinical Outcomes’, Front Immunol, vol. 13, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Ely, L. M. Brown, and H. V Fineberg, ‘Long Covid Defined’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 18, no. 391, pp. 1746–1753, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Chen, S. R. Haupert, L. Zimmermann, X. Shi, L. G. Fritsche, and B. Mukherjee, ‘Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review’, Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 226, no. 9, pp. 1593–1607, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Klein et al., ‘Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling’, Nature, vol. 623, no. 7985, pp. 139–148, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Greenhalgh, M. Sivan, A. Perlowski, and J. Nikolich, ‘Long COVID: a clinical update’, Aug. 17, 2024, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- N. Salari et al., ‘Global prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome among long COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, Biopsychosoc Med, vol. 16, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Gil et al., ‘Muscle strength and muscle mass as predictors of hospital length of stay in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: a prospective observational study’, J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1871–1878, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Lopez et al., ‘Resistance Training Load Effects on Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength Gain: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis’, Jun. 01, 2021, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- D. V. Pouliopoulou et al., ‘Rehabilitation Interventions for Physical Capacity and Quality of Life in Adults With Post–COVID-19 Condition A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, JAMA Netw Open, vol. 6, no. 9, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. R. Martins, R. J. de Oliveira, R. S. Carvalho, V. de Oliveira Damasceno, V. Z. M. da Silva, and M. S. Silva, ‘Elastic resistance training to increase muscle strength in elderly: A systematic review with meta-analysis’, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. DeMars et al., ‘What is Safe Long COVID Rehabilitation?’, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Jason and J. A. Dorri, ‘ME/CFS and Post-Exertional Malaise among Patients with Long COVID’, Neurol Int, vol. 15, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Abe, D. V. DeHoyos, M. L. Pollock, and L. Garzarella, ‘Time course for strength and muscle thickness changes following upper and lower body resistance training in men and women’, Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol, vol. 81, no. 3, 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Reis and P. M. M. Arantes, ‘Medida da força de preensão manual – validade e confiabilidade do dinamômetro saehan’, Fisioterapia e Pesquisa, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 176–181, 2011.

- I. da S. Almeida et al., ‘A medida da força muscular relativa de preensão manual representa a força muscular global em idosas?’, Research, Society and Development, vol. 11, no. 11, p. e560111134018, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- American Lung Association, ‘Pulmonary Exercise Tests’. Accessed: Mar. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests/pulmonary-exercise-test.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ‘Timed Up & Go (TUG)’. Accessed: Mar. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/media/pdfs/steadi-assessment-tug-508.pdf.

- T. A. De Melo, A. C. M. Duarte, T. S. Bezerra, F. França, N. S. Soares, and D. Brito, ‘The five times sit-to-stand test: Safety and reliability with older intensive care unit patients at discharge’, Rev Bras Ter Intensiva, vol. 31, no. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Ibrahim, I. M. Dewir, S. T. Abu El Kasem, M. M. Ragab, M. S. Abdel-Fattah, and H. M. Hussein, ‘Influences of high vs. low-intensity exercises on muscle strength, function, and quality of life in post-COVID-19 patients with sarcopenia: a randomized controlled trial’, Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, no. 27, pp. 9530–9539, 2023.

- K. Kaczmarczyk, Y. Matharu, P. Bobowik, J. Gajewski, A. Maciejewska-Skrendo, and K. Kulig, ‘Resistance Exercise Program Is Feasible and Effective in Improving Functional Strength in Post-COVID Survivors’, J Clin Med, vol. 13, no. 6, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Ramírez-Vélez et al., ‘Exercise training in long COVID: the EXER-COVID trial’, Eur Heart J, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. E. Davis, L. McCorkell, J. M. Vogel, and E. J. Topol, ‘Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations’, Nat Rev Microbiol, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 133–146, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Corrêa et al., ‘Post-exercise hypotension following different resistance exercise protocols’, Sport Sci Health, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 357–365, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Gloeckl et al., ‘Practical Recommendations for Exercise Training in Patients with Long COVID with or without Post-exertional Malaise: A Best Practice Proposal’, Sports Med Open, vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaczmarczyk, K. Płoszczyca, K. Jaskulski, and M. Czuba, ‘Eight Weeks of Resistance Training Is Not a Sufficient Stimulus to Improve Body Composition in Post-COVID-19 Elderly Adults’, J Clin Med, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Schoenfeld, ‘Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance’, 2010. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).