1. Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a sudden and painful disease characterized by the premature activation of pancreatic secretory proteins, leading to inflammation and self-damage to the organ [1, 2]. The revised Atlanta criteria classify AP based on type (interstitial edematous or necrotizing), severity (mild, moderately severe, or severe), and phase (early or late) [

3]. Once activated, inflammation leads to vascular damage, endothelial dysfunction, and recruitment of leukocytes to the pancreas, potentially progressing to severe acute pancreatitis (SAP), where mortality is high due to multi-organ failure, significantly impacting quality of life [

4]. The liver, kidneys, and lungs are particularly affected in severe cases, and their failure strongly predicts mortality [

5].

Under physiological conditions, cholecystokinin (CCK) acts as a pancreatic secretagogue in acinar cells to induce pancreatic secretion. However, excessive stimulation of CCK receptors (CCK-R) disrupts vesicular transport, triggering intracellular activation of proteolytic enzymes and ultimately leading to the cell death characteristic of acute pancreatitis [

6]. Hartwig et al. [7, 8] described a rat model of necrohemorrhagic acute pancreatitis induced by CCK-R hyperstimulation and the trypsinogen activator enzyme enterokinase (EK). This model exhibits severe local and systemic organ injury with marked intrapancreatic protease activation and is considered a model of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP). Protease activation plays a crucial role in triggering local and systemic inflammatory responses.

Acinar cell death in AP can occur via necrosis or apoptosis, with disease severity correlating directly with the extent of necrosis and inversely with apoptosis [

9]. Recent studies have shown that acinar cells may also undergo regulated cell death through pyroptosis, necroptosis, or ferroptosis [10, 11]. Additionally, autophagy is an early cellular event in AP, occurring after pancreatic protease activation [

12].

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process that degrades cytoplasmic components, functioning as a nonselective bulk degradation mechanism during starvation to promote cell survival [13, 14]. Beyond this, autophagy selectively eliminates misfolded proteins, protein aggregates, damaged organelles, intracellular pathogens, and lipid droplets— a process known as selective autophagy, which plays a critical role in the cellular response to disease [

15]. In selective autophagy, specific cargo receptors recognize cellular components and mediate autophagosome formation [

16].

VMP1 (Vacuole Membrane Protein 1) was first identified due to its high expression in acute pancreatitis [

17]. We characterized VMP1 as an autophagy-related protein whose expression alone is sufficient to trigger autophagy [

18]. VMP1 is essential for autophagosome formation [19, 20]. To investigate the role of VMP1 expression in acute pancreatitis, we developed a transgenic mouse model in which the acinar-cell-specific elastase promoter drives stable expression of VMP1-EGFP [

18]. Using this model, we identified zymophagy, a novel selective autophagy process induced by pancreatitis. Zymophagy recognizes, sequesters, and degrades prematurely activated zymogen granules within acinar cells, preventing further trypsinogen activation and cell death [

21].

Considering that premature protease activation within acinar cells is critical in triggering local inflammatory responses in acute pancreatitis, we subjected ElaI-VMP1 mice to Hartwig’s model of SAP. We investigated the impact of VMP1-mediated selective autophagy on pancreatic and extrapancreatic tissue damage in severe acute pancreatitis. Our results demonstrate that VMP1 expression exerts a protective effect, preventing the severity of experimental pancreatitis.

2. Results

2.1. Intrapancreatic Features

2.1.1. ElaI-VMP1 mice exhibit lower serum enzyme concentrations, reduced inflammatory signs, and less necrosis during experimental severe acute pancreatitis.

SAP is associated with varying degrees of pancreatic necrosis [8, 9]. To assess pancreatic damage, we analyzed serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentration as a nonspecific marker of cellular necrosis before and after SAP induction in WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice. Both untreated groups showed similar LDH values before treatment, which increased following SAP induction (ElaI-VMP1: 190 ± 14 UI/L vs. 501 ± 37 UI/L; WT: 181 ± 16 UI/L vs. 631 ± 135 UI/L, p<0.001). Although not statistically significant,

Figure 1A indicates that the LDH increase was lower in ElaI-VMP1 mice.

A hallmark of acute pancreatitis is the elevation of amylase and lipase serum levels due to pancreatic acinar cell damage. Therefore, we analyzed the serum concentrations of these enzymes in WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after pancreatitis induction. Untreated WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice had no significant differences in amylase (ElaI-VMP1: 2603 ± 180 UI/L vs. WT: 3130 ± 857 UI/L, p>0.05) or lipase levels (ElaI-VMP1: 80 ± 11 UI/L vs. WT: 61 ± 8 UI/L, p>0.05). After CAE/EK administration, both enzyme levels significantly increased compared to baseline (p<0.001). However, the increase was significantly lower in ElaI-VMP1 mice compared to WT mice (amylase: 11,830 ± 1068 UI/L vs. 9780 ± 906 UI/L, p=0.006;

Figure 1B; lipase: 289 ± 57 UI/L vs. 160 ± 36 UI/L, p=0.001;

Figure 1C). These findings suggest that the pancreas in ElaI-VMP1 mice was less affected in the SAP model compared to WT mice.

To determine whether the lower enzyme levels correlated with reduced tissue injury, we performed histopathological analysis. A total of 394 histological H&E photomicrographs from ElaI-VMP1 mice and 327 from WT mice were analyzed. CAE/EK administration caused structural alterations in the pancreas, confirming the tissue damage induced by SAP. Histologically, ElaI-VMP1 pancreata displayed significantly less damage than WT pancreata, which exhibited marked edema and hemorrhage (

Figure 1D). In WT mice, areas of edema and necrosis were more prominent, along with inflammatory cell infiltration into acinar structures (arrowhead).

The mean edema score for ElaI-VMP1 mice was 2.87 (SD: 0.53; SEM: 0.027; median: 3), whereas in WT mice, it was 2.93 (SD: 0.61; SEM: 0.034; median: 3; p=0.1621). Although the difference was not statistically significant,

Figure 1E shows that in ElaI-VMP1 mice, edema was primarily restricted to the interlobar and interlobular septa, whereas in WT mice, it extended into the interacinar and intercellular spaces (

Figure 1D).

Inflammatory cells were primarily located around blood vessels and necrotic areas (

Figure 1D, arrowhead and asterisk). The mean inflammatory score for Elal-VMP1 mice was 2.18 (SD: 1.09; SEM: 0.055; median: 2, IQR: 1.5-3), whereas in WT mice, it was 2.33 (SD: 1.24; SEM: 0.069; median: 2, IQR: 1.5-3.5; p= 0.08 -Student's T test; p=0.047-non-parametric Mann-Whitney analysis). Although the mean inflammatory score did not differ significantly between ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice (

Figure 1F), in ElaI-VMP1 mice inflammation was primarily focal (1 to 20 leukocytes/HPF), whereas in WT mice diffuse infiltration (21 to 30 leukocytes/HPF) and microabscesses (>30 leukocytes/HPF) were observed (

Figure 1D, 100X).

Quantification of necrosis revealed that the mean acinar necrosis score was significantly lower in ElaI-VMP1 mice (mean: 0.99; SD: 0.88; SEM: 0.045; median: 0.5, IQR: 0.5–1.0) compared to WT mice (mean: 1.93; SD: 1.04; SEM: 0.057; median: 2.0, IQR: 1–3). As shown in

Figure 1G, ElaI-VMP1 mice exhibited significantly fewer necrotic areas than WT mice (p<0.001 in both parametric and non-parametric analyses). Additionally, WT pancreata displayed areas of extensive confluent necrosis (>16 necrotic cells/HPF).

Fat necrosis and hemorrhage were also evaluated. The mean fat necrosis score in ElaI-VMP1 mice was 0.076 (SD: 0.22; SEM: 0.011; median: 0, IQR: 0–0), while in WT mice, it was 0.18 (SD: 0.32; SEM: 0.018; median: 0, IQR: 0–0.5). The difference was statistically significant (p<0.001) in both parametric and non-parametric analyses. Once again, ElaI-VMP1 mice exhibited significantly less necrosis than WT mice, as shown in

Figure 1H.

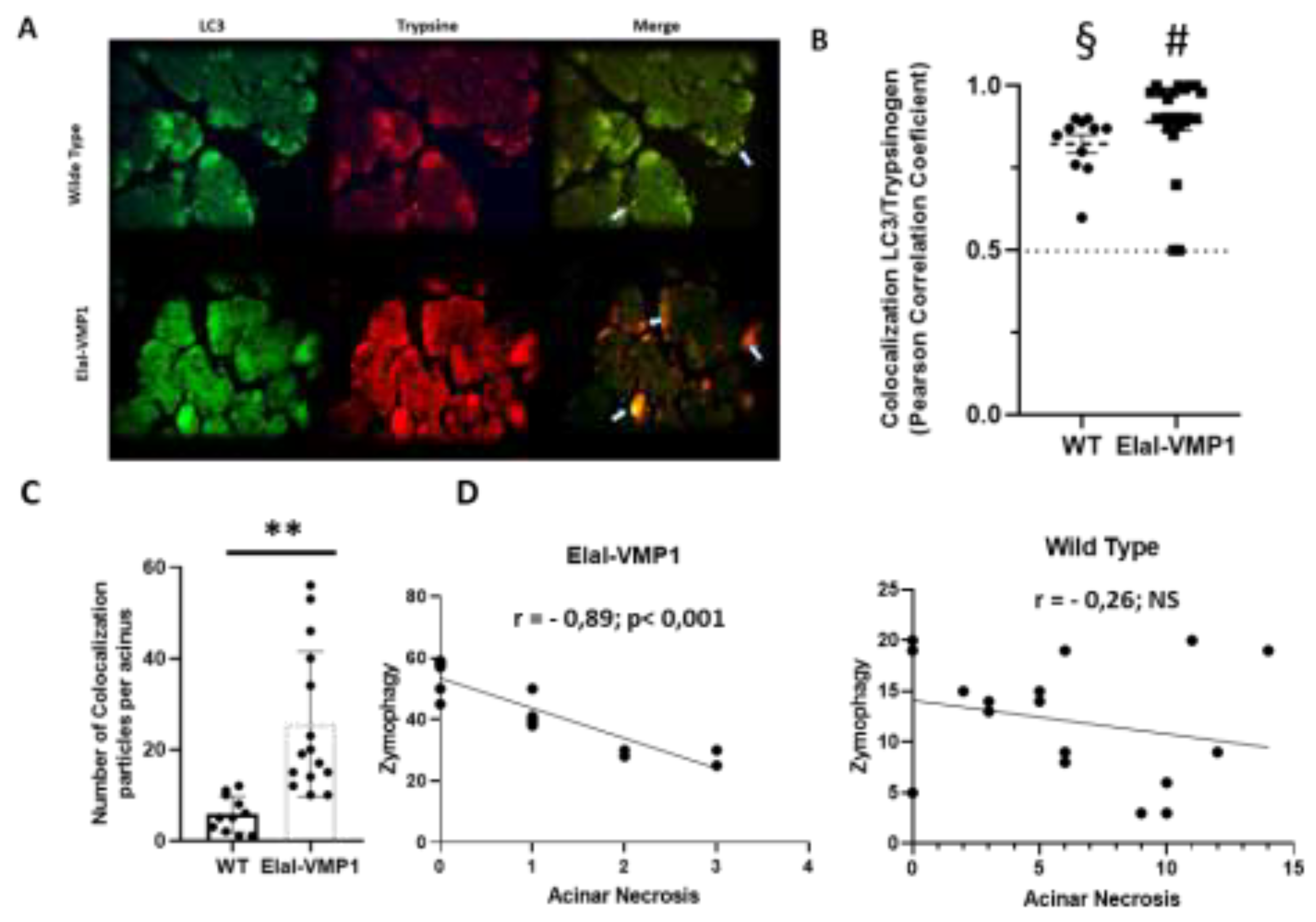

2.1.2. ElaI-VMP1 mice exhibit higher levels of zymophagy, which significantly correlates with lower acinar necrosis during experimental severe acute pancreatitis.

LC3 is a well-established autophagy marker as it remains attached to the autophagosome membrane, making it a reliable indicator of autophagy activity [

14]. During pancreatitis, trypsin is the first zymogen to become activated [

12]. In previous studies, we demonstrated that in ElaI-VMP1 mice, overstimulation of CCK-R with a supramaximal dose of CAE induces a selective form of autophagy known as zymophagy. This process selectively sequesters and degrades activated zymogen granules within the autolysosome in acinar cells, thereby preventing further trypsinogen activation and subsequent cell death [

21].

To analyze the potential relationship between zymophagy and histopathological features in severe experimental acute pancreatitis, we assessed the degree of colocalization between LC3 and trypsinogen following CAE/EK administration.

Figure 2A shows colocalization events between LC3 and trypsinogen, indicative of the presence of zymophagosomes. To confirm these structures, we performed a colocalization test using ImageJ/Fiji and found that, in both mouse groups, the observed events corresponded to colocalization points between LC3 and trypsinogen (p < 0.001, two-tailed Student’s t-test vs. the theoretical mean of 0.5) (

Figure 2B).

Next, we quantified the number of colocalization spots (i.e., the number of zymophagosomes) per acinus in ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice (

Figure 2C). ElaI-VMP1 mice exhibited significantly more colocalization events between LC3 and trypsinogen compared to WT mice (p < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t-test vs. WT), confirming that SAP triggers zymophagy, which is significantly enhanced in ElaI-VMP1 mice.

We then calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between the number of zymophagosomes and the number of necrotic acinar cells per acinus in both mouse groups following SAP induction. In ElaI-VMP1 mice, there was a strong negative correlation (r = -0.83, p<0.001), whereas in WT mice, the correlation was weak and not statistically significant (r = -0.26, p>0.5) (

Figure 2D).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that in this model of necrohemorrhagic pancreatitis, which causes extensive tissue damage in WT mice, ElaI-VMP1 mice develop only edematous pancreatitis. This reduced severity is significantly correlated with their enhanced ability to perform zymophagy.

2.2. Extrapancreatic Features

2.2.1. ElaI-VMP1 mice exhibited preserved liver histology, normal kidney histoarchitecture, and clean lung tissue during experimental severe acute pancreatitis.

The events that regulate the severity of acute pancreatitis remain largely unknown. There is a local inflammatory reaction at the site of damage, leading to a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). It is this systemic response, resulting in multi-organ failure, that is ultimately responsible for the morbidity and mortality of this disease [

22]. To assess the severity of acute pancreatitis in WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice, we performed histopathological studies evaluating liver, kidney, and lung tissue damage.

Morphological evaluation of the liver after CAE/EK-induced SAP revealed that ElaI-VMP1 mice maintained normal histoarchitecture, unlike WT mice, which exhibited numerous areas of necrosis, particularly around the central vein, accompanied by neutrophilic infiltration (

Figure 3A, LPF, left). Focusing on the necrotic areas at high power field (HPF), we observed that in ElaI-VMP1 mice, hepatocytes were preserved, whereas in WT mice, cells showed evident signs of necrosis, such as swollen cytoplasm and numerous intracytoplasmic vacuoles (

Figure 3A, HPF, center and right).

Figure 3B shows the quantification of vacuolated cells, where ElaI-VMP1 mice displayed a significantly lower number of vacuolated cells compared to WT mice (Mean ± SD, ElaI-VMP1: 1.78 ± 0.73 vs. WT: 10.5 ± 1.79; p<0.001), confirming the preservation of liver histology.

Regarding kidney evaluation, after CAE/EK administration, the histoarchitecture of the kidney was preserved in ElaI-VMP1 mice, although isolated areas of tubular necrosis with debris in the lumen were observed. In contrast, SAP induction in WT mice resulted in large areas of acute tubular necrosis with patchy loss of tubular epithelial cells, desquamation, pyknosis, and loss of nuclei. Additionally, we observed the presence of intraluminal cellular debris (

Figure 4A). Quantifying necrotic tubular cells at HPF (400X), we found that ElaI-VMP1 mice had significantly fewer necrotic cells compared to WT mice (Mean ± SD, ElaI-VMP1: 7.22 ± 1.83 vs. WT: 13.00 ± 2.93; p<0.001) (

Figure 4B). Furthermore, glomeruli from WT mice exhibited mesangial proliferation, a condition not observed in ElaI-VMP1 mice.

Finally, the analysis of lung involvement in this experimental model of severe acute pancreatitis is shown in

Figure 5. ElaI-VMP1 mice presented mostly clear lung tissue, whereas WT mice exhibited numerous hemorrhagic foci within the alveolar spaces, associated with numerous infiltrating neutrophils (

Figure 5A). Regarding alveolar capillary septum thickness as an indicator of inflammation, we found that CAE/EK administration caused significantly less widening in ElaI-VMP1 mice than in WT mice (Mean ± SD, ElaI-VMP1: 56.56 ± 19.45 vs. WT: 112.78 ± 21.99 pixels/HPF; p<0.01, Student’s t-test) as shown in

Figure 5B and

Figure 5C.

In summary, the results obtained from the ElaI-VMP1 mice indicate that zymophagy functions as a protective cellular mechanism, preventing the severity of acute pancreatitis.

3. Discussion

ElaI-VMP1 mice are transgenic mice in which the acinar-cell-specific elastase promoter drives VMP1 expression and autophagy, without any alteration in pancreatic tissue

[18]. The induction of acute pancreatitis by hyperstimulation of CCK-R with caerulein (CAE) triggers zymophagy in these mice, preventing the spread of zymogen activation and cell death

[21]. In this study, we used Hartwig et al.'s model

[8] of necrohemorrhagic acute pancreatitis, induced by simultaneous infusion of CAE and enterokinase (EK), in wild type (WT) and ElaI-VMP1 mice. This model is characterized by severe local and systemic organ injury, with marked intrapancreatic protease activation. Our results show that, although the necrohemorrhagic model of acute pancreatitis (AP) is characterized by severe local and systemic organ injury, in ElaI-VMP1 mice, the severity of the disease was significantly reduced. These findings suggest that zymophagy, the selective autophagy mediated by VMP1 expression, functions as a protective cellular mechanism, preventing the severity of acute pancreatitis.

As previously reported in ElaI-VMP1 mice subjected to cerulein-induced pancreatitis, we found that in the SAP model, ElaI-VMP1 mice exhibited dramatically less pancreatic tissue damage (i.e., acinar or fat necrosis, hemorrhagic foci, and inflammatory infiltration) (

Figure 1). Furthermore, we evaluated extrapancreatic features characteristic of SAP in the lungs, liver, and kidneys, as markers of systemic injury and disease severity.

Histopathological analysis of the liver and kidneys revealed a similar pattern, with a clear reduction in tissue damage in ElaI-VMP1 mice. Regarding kidneys, acute kidney injury is one of the main complications of SAP

[23]. However, we found that ElaI-VMP1 mice maintained conserved kidney histoarchitecture, with only isolated areas of tubular necrosis and debris in the lumen, in contrast to WT mice, which exhibited large areas of acute tubular necrosis, desquamation, pyknosis, and loss of nuclei — typical damage seen in acute renal failure associated with SAP (

Figure 4).

It has been proposed that kidney injury following SAP is associated with a complex process, which involves the release of cytokines, chemokines, and damage-associated molecular patterns from dying acinar cells into the bloodstream. However, the precise underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated

[24]. Regarding liver tissue, as part of the pancreatic blood flow, high concentrations of activating enzymes and inflammatory mediators reach the liver early during AP. It has been reported that pancreatic elastases induce Kupffer cells to produce cytokines by activating the nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway during SAP

[25]. Additionally, pancreatitis causes disruption of the intestinal barrier, allowing endotoxins to enter the bloodstream and invade the liver, where they activate phospholipase A2, leading to membrane phospholipid degradation and inducing free radicals that mediate lipid peroxidation in liver cells

[26]. In our study, we found that while the liver histoarchitecture and hepatocytes were preserved in ElaI-VMP1 mice, hepatocytes of WT mice exhibited swollen cytoplasm and numerous intracytoplasmic vacuoles, indicative of cellular necrosis (

Figure 3).

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is a systemic inflammatory complication commonly associated with pancreatitis, which is triggered by neutrophil invasion of the lungs

[7]. Normal lungs have thin septa with few leukocytes. In contrast, our results showed that ElaI-VMP1 mice presented clean lung tissue, whereas WT mice exhibited increased septal thickness, hemorrhagic foci within the alveolar spaces, and numerous infiltrating neutrophils (

Figure 5).

Trypsinogen activation is widely accepted as one of the early events in the pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis

[12], leading to necrosis and the interstitial spreading of activated zymogen, transforming mild edematous pancreatitis into a severe necrohemorrhagic disease

[27, 28]. Our results show that the selective autophagic pathway, zymophagy, is highly activated in pancreatic acinar cells from ElaI-VMP1 mice during the SAP model and significantly correlates with the rate of necrosis in pancreatic tissue. The reduction in pancreatic tissue damage is translated into a lower level of systemic injury in ElaI-VMP1 mice.

Moreover, the protective cellular response mediated by VMP1 expression would explain, at least in part, the self-limiting nature of the disease in most cases. In contrast, the severe forms of pancreatitis may present an excess load and accelerated degradation demand that could overwhelm or alter the protective capacity of this selective autophagic process.

The severity of the disease is associated with the induction of proinflammatory cytokines, which are thought to be responsible for systemic injury

[2] ElaI-VMP1 mice showed a significant reduction in acinar necrosis. Whether this reduction in tissue damage correlates with less expression of NF-κB, leading to decreased production of pro-inflammatory mediators and therefore lesser systemic injury, warrants further study. The reduced systemic impact in ElaI-VMP1 mice seems to be entirely attributed to the lower pancreatic damage observed in these animals, resulting in less systemic inflammation. However, the release of particles or substances that could potentially offer protection to extrapancreatic tissues cannot be ruled out at this time

[29 - 31].

In summary, we describe for the first time that in ElaI-VMP1 mice, the severity of the disease is completely attenuated and correlates with the capacity to develop effective zymophagy mediated by VMP1. These results confirm that zymophagy functions as a protective pathophysiological mechanism against both pancreatic and extrapancreatic tissue injury. Enhancing selective autophagy could be a potential therapeutic strategy for acute pancreatitis.

4. Materials and Methods

Male C57BL6J mice (referred to as wild type, WT) and C57BL6J-ElaI-VMP1 transgenic mice (referred to as ElaI-VMP1) weighing 20-25 g were used in the experiments. The animals were housed with free access to food and water. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Research Committee (CICUAL) of the School of Pharmacy and Biochemistry, University of Buenos Aires, and strictly followed the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals (ICLAS).

Transgenic mice were kindly provided by Dr. Juan Iovanna (INSERM U1068, Marseille, France). The transgene cassette was constructed using the pBEG vector [

18], [

32]. Briefly, the expression cassette contains the acinar-specific control region (-500 to +8) from the rat elastase I gene and the human growth hormone 3’-untranslated region (UTR) (+500 to +2657). This construct was digested with BamHI, filled in, dephosphorylated, and ligated with rat VMP1-EGFP released from the pEGFPVMP1 plasmid. A 1940-kb HindIII/NotI fragment was isolated and used for microinjections into inbred FVB zygotes. Genomic DNA was prepared and tested by Southern blot and PCR.

WT or ElaI-VMP1 mice were fasted for 12-16 hours with free access to water. Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) was induced by 7 hourly intraperitoneal injections of 50 μg/kg caerulein (CAE). Starting from the second injection of CAE, 30 IU/kg of enterokinase (EK) was also administered, i.e., animals received 7 injections of CAE and 5 injections of EK. Mice were euthanized 9 hours after the first injection. Both CAE and EK were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Animal serum amylase, lipase and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity were measured by Cobas® c 501 Analyzer (Roche) and are expressed as units per liter.

Histological Studies

○

Pancreatic Tissue

For histological analysis, the pancreas was removed, and tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. One set of tissues was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), while another set was prepared for immunofluorescence assays. The severity of pancreatitis was evaluated in a blind manner using at least 18 high-power fields (HPF, i.e., 400X) per animal. Schmidt's histopathologic criteria [

33] were applied to score the intensity of damage in pancreatic tissues. The scoring system (0 to 4) is based on morphometric analyses, including the measurement of edema (with the lowest score for absent and the highest for diffuse expansion of intercellular septa/isolated island-like acinar cells), acinar necrosis (from absent to >16 necrotic cells/HPF - extensive confluent necrosis), inflammation (from 0 to 1 intralobular or perivascular leukocyte/HPF (focal inflammation) to more than 35 leukocytes/HPF or confluent micro abscesses - the most severe score), and hemorrhage.

- ○

Extra-pancreatic Tissue Damage

To assess the systemic impact caused by SAP, we evaluated histological changes and the degree of damage to liver, kidney, and lung tissue.

Liver Damage: At low-power fields (LPF, i.e., 40X), the presence and localization of necrotic areas (e.g., centrilobular) were considered. At HPF, histological evidence of loss of hepatocyte membrane integrity, signs of tissue necrosis (e.g., cytoplasm swelling and/or intracellular vacuoles), and areas of leukocyte infiltration, especially in centrilobular areas, were examined.

Kidney Damage: Kidney damage was assessed by examining areas of acute tubular necrosis with patchy loss of tubular epithelial cells, desquamation, pyknosis, and loss of nuclei, as well as the presence of intraluminal cellular debris.

Lung Damage: For lung damage evaluation, particular emphasis was placed on septal integrity and thickness, as well as hemorrhagic foci in the alveolar spaces. The presence of leukocyte infiltration was noted, though it was not the central focus of the lung damage assessment.

∙

Antibodies

Polyclonal sheep anti-LC3 (Abcam) antibody was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Polyclonal goat anti-trypsin (Santa Cruz) antibody was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used for immunofluorescence assays.

Tissue sections (5 μm) were washed several times with PBS. Samples were permeabilized with triton X-100 0.1% in PBS for 5 min, washed three times with PBS, and blocked with fetal bovine serum 10% in PBS for 1 h. Then, tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4° C. The next day, samples were incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Then, samples were. Samples were mounted in 1,4-diazabicyclo [2.2.2] octane (Sigma) and observed using a LSM Olympus FV1000 microscope with an UPLSAPO 60X objective (NA: 1.35).

Changes in enzyme concentrations before and after the experimental intervention were evaluated by two-way ANOVA, with repeated measures in one of the factors (Bonferroni Post Hoc Test). Differences between two groups of independent quantitative data were assessed using Student’s t-test and/or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, depending on the data distribution. In some cases, both tests were applied. In cases where both tests were significant (p<0.05), only the significance of the parametric test is reported. When significance differs between the parametric and non-parametric tests, the significance of each test is reported separately. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to assess whether zymophagy was correlated with the degree of acinar necrosis. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: NS, non-significant; *, p <0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CDG and MIV; methodology, VB and EZ; software, VB, AR and CDG; validation, VB, CDG, EZ, AR and MIV; formal analysis, VB, CDG, EZ and MIV; resources, CDG and MIV; data curation, VB, CDG and EZ; writing—original draft preparation, VB, CDG, AR and MIV; writing—review and editing, VB, CDG, AR and MIV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Buenos Aires (UBACyT 2018-2020 20020170100082BA, and UBACyT 2023-2025- 20020220300232BA), the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET - PIP 2021-2023 GI− 11220200101549CO, and PUE 22920170100033) and the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion (ANPCyT-PICT2019-01664, and PICT-2021-I-A-00328).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tomás Rittaco for his help in the double-blind analysis of histology specimens.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AP |

Acute Pancreatitis |

| SAP |

Severe Acute Pancreatitis |

| CCK |

Cholecystokinin |

| CCK-R |

Cholecystokinin Receptor |

| EK |

Enterokinase |

| VMP1 |

Vacuole Membrane Protein 1 |

| ElaI-VMP1 |

C57BL6J-ElaI-VMP1 transgenic mice |

| WT |

Wild Type |

| CAE |

Caerulein |

| LDH |

Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| H&E |

Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| HPF |

High-Power Field |

| LPF |

Low-Power Field |

| NS |

Non-Significant |

| SEM |

Standard Error of the Mean |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear Transcription Factor-κB |

References

- Habtezion, A.; Gukovskaya, A.S.; Pandol, S.J. Acute Pancreatitis: A Multifaceted Set of Organelle and Cellular Interactions. Gastroenterology 2019, vol. 156, pp. 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Papachristou, G.I. New insights into acute pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, vol. 16, pp. [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.A.; et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013, vol. 62, pp. [CrossRef]

- Dumnicka, P. ; Maduzia, D; Ceranowicz, P.; Olszanecki, R.; Drożdż, R.; Kuśnierz-Cabala, B. The Interplay between Inflammation, Coagulation and Endothelial Injury in the Early Phase of Acute Pancreatitis: Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2017, vol. 18, p. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D. Autophagy Strengthens Intestinal Mucosal Barrier by Attenuating Oxidative Stress in Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2018, vol. 63, pp. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; et al. A Comparative Study of Techniques for Differential Expression Analysis on RNA-Seq Data. PLoS One 2014, vol. 9, pp. 1032; e07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, W.; et al. Enterokinase induces severe necrosis and rapid mortality in cerulein pancreatitis: Characterization of a novel noninvasive rat model of necro-hemorrhagic pancreatitis. Surgery 2007, vol. 142, pp. [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, W.; et al. A novel animal model of severe pancreatitis in mice and its differences to the rat. Surgery 2008, vol. 144, pp. [CrossRef]

- Gukovskaya, A.S.; Gukovsky, I. Autophagy and pancreatitis. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2012, vol. 303, pp. 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. CircHIPK3 Promotes Pyroptosis in Acinar Cells Through Regulation of the miR-193a-5p/GSDMD Axis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, vol. 7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Han, Z. miR-339-3p regulated acute pancreatitis induced by caerulein through targeting TNF receptor-associated factor 3 in AR42J cells. Open Life Sci 2020, vol. 15, pp. [CrossRef]

- Malla, S.R.; et al. Early trypsin activation develops independently of autophagy in caerulein-induced pancreatitis in mice. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2020, vol. 77, pp. 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, D.; Renna, F.J.; Vaccaro, M.I. Initial Steps in Mammalian Autophagosome Biogenesis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2018, vol. 6. [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition). Taylor and Francis Ltd 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B.; Packer, M.; Codogno, P. Development of autophagy inducers in clinical medicine. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2015, vol. 125, pp. 24. [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.; Lamark, T. Selective Autophagy: ATG8 Family Proteins, LIR Motifs and Cargo Receptors. J Mol Biol 2020, vol. 432, pp. [CrossRef]

- Dusetti, N.J.; et al. Cloning and Expression of the Rat Vacuole Membrane Protein 1 (VMP1), a New Gene Activated in Pancreas with Acute Pancreatitis, Which Promotes Vacuole Formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002, vol. 290, pp. [CrossRef]

- Ropolo, A.; et al. The Pancreatitis-induced Vacuole Membrane Protein 1 Triggers Autophagy in Mammalian Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, vol. 282, pp. 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molejon, M.I.; Ropolo, A.; Lo Re, A.; Boggio, V.; Vaccaro, M.I. The VMP1-Beclin 1 interaction regulates autophagy induction. Sci Rep 2013, vol. 3, p. 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbeni, A.C.; et al. ER–plasma membrane contact sites contribute to autophagosome biogenesis by regulation of local PI3P synthesis. EMBO J 2017, vol. 36, pp. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, D.; et al. Zymophagy, a Novel Selective Autophagy Pathway Mediated by VMP1-USP9x-p62, Prevents Pancreatic Cell Death. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, vol. 286, pp. 8308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerle, J.; Sendler, M.; Hegyi, E.; Beyer, G.; Lerch, M.M.; Sahin-Tóth, M. Genetics, Cell Biology, and Pathophysiology of Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2019, vol. 156, pp. 1951-1968. e1. [CrossRef]

- Kes, P.; VuČIČEviĆ, Ž.; RatkoviĆ-GusiĆ, I.; Fotivec, A. Acute Renal Failure Complicating Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Ren Fail 1996, vol. 18, pp. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.; Lu, H.; Zhu, H.; Guo, Y.; Bai, Y. A network-regulative pattern in the pathogenesis of kidney injury following severe acute pancreatitis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, vol. 125, p. 1099; 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murr, M.M.; Yang, J.; Fier, A.; Kaylor, P.; Mastorides, S.; Norman, J.G. Pancreatic Elastase Induces Liver Injury by Activating Cytokine Production Within Kupffer Cells via Nuclear Factor-Kappa B. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2002, vol. 6, pp. [CrossRef]

- Kazantsev, G.B.; et al. Plasmid labeling confirms bacterial translocation in pancreatitis. The American Journal of Surgery 1994, vol. 167, pp. [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, W.; Jimenez, R.E.; Werner, J.; Lewandrowski, K.B.; Warshaw, A.L.; Castillo, C.F. Interstitial trypsinogen release and its relevance to the transformation of mild into necrotizing pancreatitis in rats. Gastroenterology 1999, vol. 117, pp. [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, W.; et al. Trypsin and activation of circulating trypsinogen contribute to pancreatitis-associated lung injury. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 1999, vol. 277, pp. 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Alesanco, A.; et al. Acute pancreatitis promotes the generation of two different exosome populations. Sci Rep 2019, vol. 9, p. 1988; 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascal, M.; et al. Inflammatory capacity of exosomes released in the early stages of acute pancreatitis predicts the severity of the disease. J Pathol 2022, vol. 256, pp. 92. [CrossRef]

- Armengol-Badia, O.; et al. The Microenvironment in an Experimental Model of Acute Pancreatitis Can Modify the Formation of the Protein Corona of sEVs, with Implications on Their Biological Function. Int J Mol Sci 2024, vol. 25, p. 1296; 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Zapico, M.E.; et al. Ectopic expression of VAV1 reveals an unexpected role in pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2005, vol. 7, pp. 49. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.A.N.; et al. A Better Model of Acute Pancreatitis for Evaluating Therapy. Ann Surg 1992, vol. 215, [Online]. Available: https://journals.lww.com/annalsofsurgery/fulltext/1992/01000/a_better_model_of_acute_pancreatitis_for.7.

Figure 1.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Lower Enzyme Serum Concentrations, Reduced Inflammatory Signs, and Less Necrosis During Experimental Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP). (a-c) Serum concentrations of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) (a), Amylase (b), and Lipase (c) following CAE/EK administration. ***, p < 0.001 vs. untreated mice; §, p = 0.006 vs. wild type (WT); #, p < 0.001 vs. WT. Bars represent mean ± SD, n = 4 per group. (d) Representative photomicrographs of H&E-stained pancreatic tissue from ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after CAE/EK administration, showing edema, inflammatory infiltration, and acinar necrosis. Inflammatory infiltration is present in the interstitial and inter-acinar spaces in WT mice (arrowhead) and around necrotic areas (asterisk). (e) Edema, (f) Inflammation, (g) Acinar Necrosis, and (h) Fat Necrosis & Hemorrhage scores in ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after CAE/EK administration. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT. For further details, refer to the text.

Figure 1.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Lower Enzyme Serum Concentrations, Reduced Inflammatory Signs, and Less Necrosis During Experimental Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP). (a-c) Serum concentrations of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) (a), Amylase (b), and Lipase (c) following CAE/EK administration. ***, p < 0.001 vs. untreated mice; §, p = 0.006 vs. wild type (WT); #, p < 0.001 vs. WT. Bars represent mean ± SD, n = 4 per group. (d) Representative photomicrographs of H&E-stained pancreatic tissue from ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after CAE/EK administration, showing edema, inflammatory infiltration, and acinar necrosis. Inflammatory infiltration is present in the interstitial and inter-acinar spaces in WT mice (arrowhead) and around necrotic areas (asterisk). (e) Edema, (f) Inflammation, (g) Acinar Necrosis, and (h) Fat Necrosis & Hemorrhage scores in ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after CAE/EK administration. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT. For further details, refer to the text.

Figure 2.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Higher Levels of Zymophagy, Which Correlate Significantly with Lower Levels of Acinar Necrosis Following Experimental SAP Induction. (a) Representative microphotographs of immunofluorescence assays using anti-LC3 (green) and anti-trypsinogen (red) antibodies in ElaI-VMP1 and wild type (WT) mice after CAE/EK administration. Some representative colocalization spots are marked with arrows. (b) Colocalization between LC3 and trypsinogen was quantified in at least 18 pancreatic acini per animal (n = 4). Each point on the graph represents Pearson’s correlation coefficient. § or #, p < 0.001, as determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test compared to the theoretical mean of 0.5. Error bars represent SEM. (c) Quantification of the number of colocalization spots, indicating the number of zymophagosomes per acinus, in at least 18 pancreatic acini of ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice. Error bars represent SD (n = 4). **, p < 0.01, as determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test vs. WT mice. (d) Correlation between the number of zymophagosomes and the number of necrotic acinar cells per pancreatic acinus in ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after SAP induction. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and the level of significance are shown.3.

Figure 2.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Higher Levels of Zymophagy, Which Correlate Significantly with Lower Levels of Acinar Necrosis Following Experimental SAP Induction. (a) Representative microphotographs of immunofluorescence assays using anti-LC3 (green) and anti-trypsinogen (red) antibodies in ElaI-VMP1 and wild type (WT) mice after CAE/EK administration. Some representative colocalization spots are marked with arrows. (b) Colocalization between LC3 and trypsinogen was quantified in at least 18 pancreatic acini per animal (n = 4). Each point on the graph represents Pearson’s correlation coefficient. § or #, p < 0.001, as determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test compared to the theoretical mean of 0.5. Error bars represent SEM. (c) Quantification of the number of colocalization spots, indicating the number of zymophagosomes per acinus, in at least 18 pancreatic acini of ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice. Error bars represent SD (n = 4). **, p < 0.01, as determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test vs. WT mice. (d) Correlation between the number of zymophagosomes and the number of necrotic acinar cells per pancreatic acinus in ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after SAP induction. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and the level of significance are shown.3.

Figure 3.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Preserved Liver Histology During Experimental SAP. (a) Representative images of liver tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after CAE/EK administration, stained with H&E. Images at LPF (40X) and HPF (400X and 1000X) show representative necrotic areas (black arrows at LPF) and cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles (white arrows at HPF 1000X). (b) Quantification of vacuolated hepatic cells in at least 18 HPF of both ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after SAP induction. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT.

Figure 3.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Preserved Liver Histology During Experimental SAP. (a) Representative images of liver tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after CAE/EK administration, stained with H&E. Images at LPF (40X) and HPF (400X and 1000X) show representative necrotic areas (black arrows at LPF) and cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles (white arrows at HPF 1000X). (b) Quantification of vacuolated hepatic cells in at least 18 HPF of both ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after SAP induction. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT.

Figure 4.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Normal Kidney Histoarchitecture Without Mesangial Proliferation After Experimental SAP. (a) Representative images of kidney tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after CAE/EK administration, stained with H&E. (b) Quantification of necrotic tubular cells in at least 18 HPF of both ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after SAP induction. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT.

Figure 4.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Exhibit Normal Kidney Histoarchitecture Without Mesangial Proliferation After Experimental SAP. (a) Representative images of kidney tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after CAE/EK administration, stained with H&E. (b) Quantification of necrotic tubular cells in at least 18 HPF of both ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice after SAP induction. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT.

Figure 5.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Show Clean Lung Tissue and Reduced Septal Thickness During Experimental SAP. (a) Representative images of lung tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after SAP induction, stained with H&E. (b) Representative images of lung tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after SAP induction, stained with Negative stain. Thickness of alveolar-capillary septum is marked with yellow lines in panel B. (c) Quantification of septal thickness from at least 18 HPF per animal after CAE/EK administration in ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT

Figure 5.

ElaI-VMP1 Mice Show Clean Lung Tissue and Reduced Septal Thickness During Experimental SAP. (a) Representative images of lung tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after SAP induction, stained with H&E. (b) Representative images of lung tissue from WT and ElaI-VMP1 mice after SAP induction, stained with Negative stain. Thickness of alveolar-capillary septum is marked with yellow lines in panel B. (c) Quantification of septal thickness from at least 18 HPF per animal after CAE/EK administration in ElaI-VMP1 and WT mice. ***, p < 0.001 vs. WT

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).