1. Introduction

Recycling Waste Cooking Oils (WCOs) has emerged as an important topic in the last years [

1]. Within the available methods and technologies for WCOs refining for non-biodiesel application, water treatment under controlled conditions [2] has revealed able to provide a high purity recycled vegetable oil [

3]. Nevertheless, while the purity assessment conducted through

1H NMR spectroscopy indicates a high level of triglycerides purity[

4] upon water processing, minor constituents remain detectable as revealed by UV-VIS[

5] or SPME-GC[

6] analyses. These impurities arise from several sources and are associated with the lifecycle of the oil prior to recycling.

WCOs can be contaminated by metal traces, aldehydes, ketones, heterocycles and other organic molecules originated from cooking tools, Maillard process [

7,

8], and food leaching [

9]. These minor components can be also removed by treatment with an adsorbent material as natural clays or alternative powders [

10]. Preliminary analysis of the volatile fraction prior and after bentonite treatment of WCOs’ samples revealed a complex mechanism underlying the action of bentonite. The results indicated that even slightly variations in the clay composition, lead to the preferential removal of different chemical groups [

6]. This structure-activity relationship can also be observed by UV-VIS spectroscopy [

11].

In this context, any knowledge regarding the mechanisms behind the absorption capacity of clay, can contribute to the development of specific protocols aimed at vegetable oil recycling processes. Recently, some of us have reported a study on the recycling of used vegetable oils with hydrophilic or hydrophobic bentonites, revealing a pivotal role of the hydrophobicity in the removal of polar compounds from the waste [

12]. In that study, the presence of small amount of water was crucial in determining the effectiveness of hydrophobic bentonites when used with recycled vegetables oils. Looking at the recent studies published by some of us, the topic of bentonite processing of WCOs has been deeply addressed. Nevertheless, recent sustainability estimations[

4] indicated water processing as more feasible with respect to clay adsorption. In this context, two relevant aspects were not addressed: the use of bentonite clays to treat already recycled used vegetable oils, and the reason of the different performances within hydrophilic and hydrophobic bentonites sold with the same CAS number and apparently with same physical characteristics.

Thus, four bentonites were used to capture the volatiles present in a recycled mixture of triglycerides considering the variation of the pour point of the treated oil serving as an indicator to highlight different outcomes related to different bentonites. Using a Design of Experiments (DOE) approach, the potential to prepare mixtures of different bentonites to be exploited as hybrid media in vegetable oil recycling, has been assessed. A detailed characterization of the bentonites was carried out by solid state magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR (29Si and 27Al), proving valuable insights into the morphology of the materials in relation to their properties, allowing to relate the coordination mode of Si and Al atoms with the physical properties of the material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Hydrophilic S001 (MKCR3493) and hydrophobic S002 (MKCN7873) bentonites were purchased from Merk Europe (CAS number 1302-78-9).

2.2. Ball Milling

8 grams of bentonite (S001 or S002) were ball milled for 20 min in a SPEX 8000 (SPEX CertiPrep, USA) shaker mill at 875 rpm. The as-obtained S001M1 and S002M1 samples were then used for oil refinement.

2.3. Vegetable Oil Processing

100 g of vegetable oil and 15 g of clay (15 wt%) were placed in a beaker and the mixture was stirred during 30 min, and then filtered under vacuum. The processed oil was then subjected to pour point analysis.

2.4. Pour Point Determination

ASTM D97 method was adapted to our purposes and employed for pour point determination. Oil samples (20 g) were placed in a falcon and slowly cooled in an ice/salt bath. The temperature of the oil was monitored by an internal thermometer every minute, until visual confirmation of the change from liquid to solid.

2.5. Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME)

A 100 μm PDMS/DVB/CAR (Polydimethylsiloxane/Divinylbenzene/Carboxen) coated fibre 50/30 Stableflex (Supelco, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo., USA) was preconditioned at 270 °C during 1 h. 5 g of sample were added to a 20 mL SPME vial (75.5 × 22.5 mm) equipped with a septum. The system was conditioned for 5 min at 60 °C. Thus, the fiber was exposed to the headspace for 30 min. Once the extraction was completed, the fiber was desorbed for 2 min into the injector at a temperature of 250 °C in a splitless injection mode.

2.6. Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) Analysis

GC-MS measurements were carried out using an Agilent 6590 GC, coupled with an Agilent 5973 MSD detector. A ZB-Wax 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness column was used for the chromatographic separation. The following temperature ramp was used: 40 °C hold for 4 min, increased to 150 °C at a rate of 3.0 °C/min, and held for 3 min, before be increased to 220 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. Finally, the temperature was heled for 10 min. The constant flow of helium (carrier gas) was 1 mL/min. The data were analyzed using a MassHunter Workstation B.06.00 SP1. Identification of trhe analytes (

Table 2) was achieved by comparing them with co-injected standards and matching their MS fragmentation patterns and retention indices against built-in libraries, literature data, or commercial mass spectral libraries (NIST/EPA/NIH 2008; HP1607 from Agilent Technologies).

2.6.1. Retention indexes

A hydrocarbon mixture of n-alkanes (C9-C22) was analyzed separately under the same chromatographic conditions to calculate the retention indexes with the generalized equation by Van del Dool and Kartz [

13].

- (I)

Ix=100[(tx-tn)/(tn+1-tn)+n]

where t is the retention time, x is the analyte, n is the number of carbons of alkane that elutes before analyte and n+1 is the number of carbons of alkane that elutes after analyte.

2.7. NMR Analysis

Solid state NMR spectra were acquired with a Bruker NEO 500 spectrometer, equipped with a MAS iprobe, operating at 500.13 MHz for

1H, 99.35 MHz for

29Si and 130.31 MHz for

27Al. Solid samples were packed in a 4 mm zirconium oxide rotor.

29Si direct excitation (DE-MAS) spectra were acquired with recycle delay of 20 s, spinning speed of 10 kHz and 560 scans.

27Al spectra were obtained with recycle delay of 5 s, spinning speed of 12 kHz and 256 scans. All the experiments were performed at 298 K. Deconvolutions were performed with origin 2024 using a Lorentzian fitting model. The chemical shifts are reported relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) for

29Si using octakis-(trimethylsiloxy)silsesquioxane (Q8M8) and for

27Al using Al(NO

3)

3·9H

2O as secondary standard, respectively [

14].

2.8. Karl-Fischer Titration

Water content was determined through Karl Fischer titration with a coulometric MKV-710B (Alkimia SRL, Milan, Italy).

2.9. FT-IR Spectroscopy

For the FT-IR measurements, a Spectrophotometer FT-IR Jasco 480 Plus was employed. The powders were analysed in form of tablets prepared by mixing the bentonite with anhydrous KBr and pressing them into a disk by a hydraulic press.

2.10. Design of Experiments (DoE)

Simplex-Lattice design was used to study the effects of four components in four runs. The design was run in a single block and the order of the experiments was randomized to minimize the effects of lurking variables. Statgraphics 18 software was used for the statistical multivariate analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

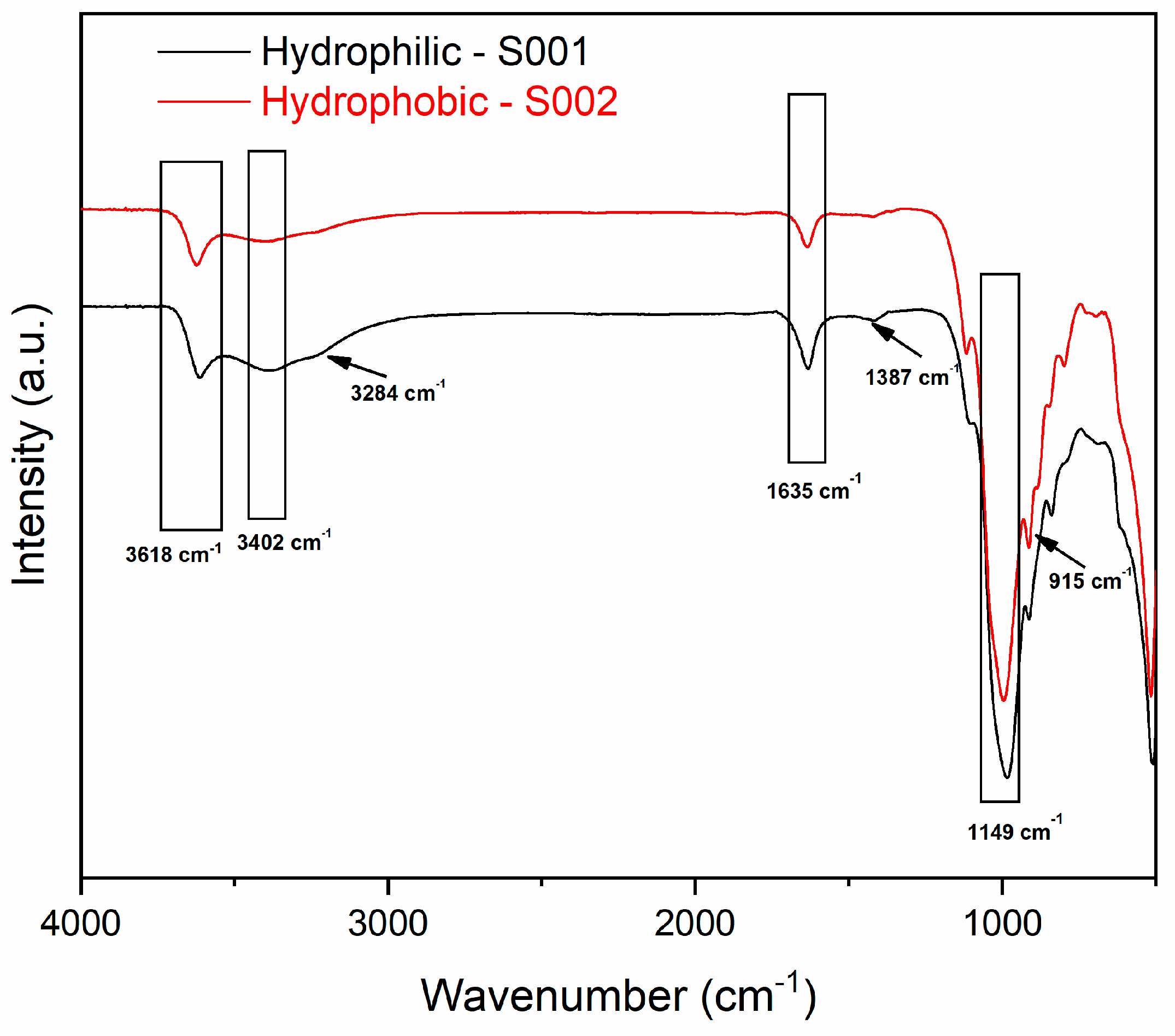

3.1. FT-IR Spectroscopy Analysis

Bentonite is a natural material containing different minerals which can influence its properties [

15]. According to the provider, the commercial bentonites herein considered are composed by montmorillonite, Al

2O

3×4SiO

2×H

2O (molecular weight 180.1 g/mol), with a particle size lower than 74 μm, and a mean particle size of 5.45 μm [

16]. Nevertheless, no additional data are available regarding the differences between the two products. Previous SEM and TEM analyses on same batches of bentonites, revealed, respectively, different interlayer distances and particle shape, while powder X-ray analysis did not highlight any relevant difference [

4]. Nevertheless, the behaviour of the two clays, prior and after grinding, was different, confirming different properties of apparent very similar materials. After being subjected to ball milling process, significative differences, in terms of microstructure, were observed, interlayer distances were modified with respect to the pristine materials, probably due to the partial releasing of trapped water upon grinding conditions [

12]. To detect variations in the chemical groups, FT-IR analysis was conducted on both bentonites (

Figure 1).

Looking at the spectra showed in

Figure 1, it is possible to clearly see the different IR profile of S001 and S002 bentonites. It is known that hydrophobic bentonites are obtained by chemical treatment of hydrophilic ones with the consequent removal of minor components, resulting in a less complex mixture of chemical groups in the FT-IR spectrum [

17]. Regarding the specific composition observed, both samples show typical bands relative to the Si-O stretching (1149 cm

-1), the bending of the adsorbed water (1635 cm

-1), to the stretching of the adsorbed water (3402 cm

-1), as well as the OH-Al stretching band (3618 cm

-1). For the hydrophilic S001 bentonite, relevant bands associated with the -OH vibrations were detected at 3284 cm

-1, and CO

3 stretching of calcite at 1387 cm

-1. The band at 915 cm

-1, visible in the hydrophobic S002 sample can be attributed to the Al-Al-OH bending [

16] [

17].

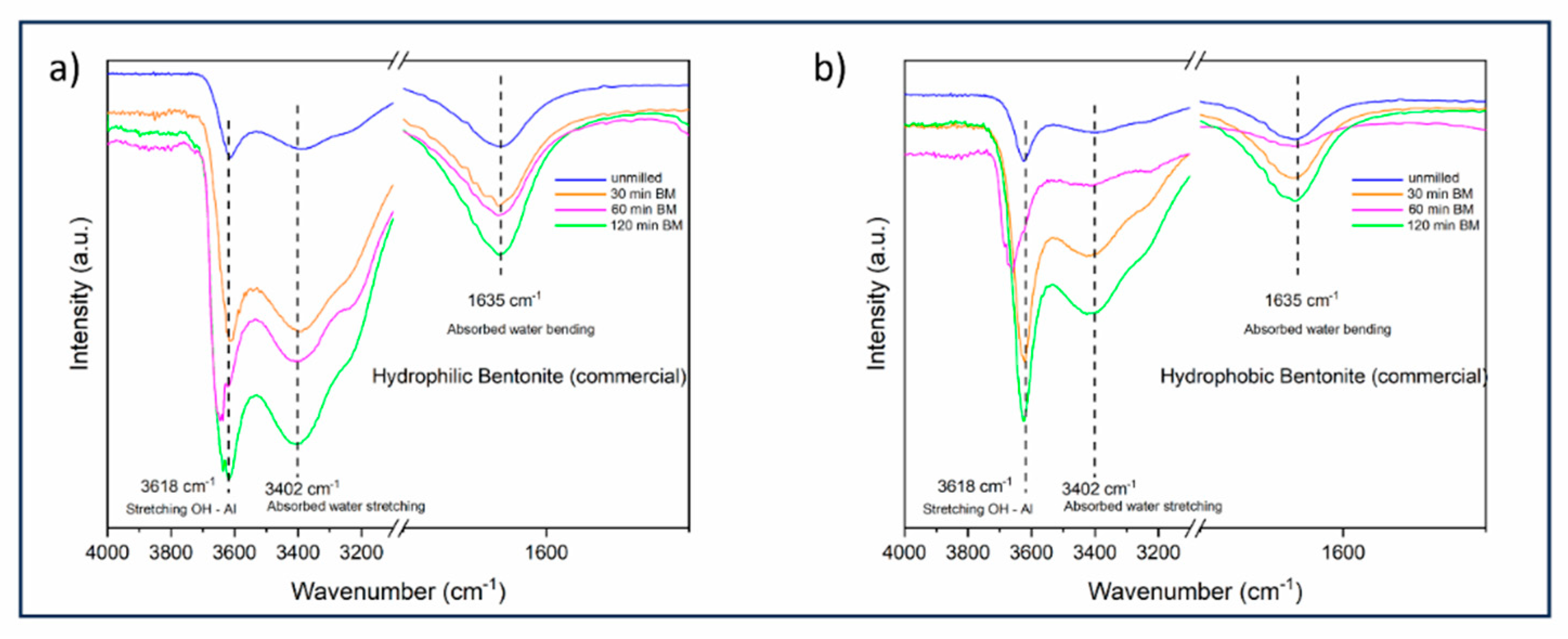

In addition to the characterization of the starting materials, both the bentonites were monitored during the ball milling procedure, specifically at 30, 60, and 120 minutes (

Figure 2).

As already reported for similar samples subjected to the same milling treatment [

12], it is possible to notice, for both bentonites, some slight changes in the FT-IR spectrum after 60 min. of ball milling (shifting of the stretching OH-Al band and consistent attenuation of the adsorbed water bending band), followed by a further change which apparently restore of the original chemical structure at 120 min. For this reason, the milled bentonites further employed to treat the triglycerides mixture were grinded for 60 min.

3.2. NMR Morphological Analysis

To overcome the difficulties occurred with the powder X-ray diffraction characterization and to add further information to the FT-IR spectroscopy data, thus providing a satisfying description of the differences between the bentonites studied, multinuclear solid-state NMR spectroscopy was explored. In fact, the limited selectivity of X-ray diffraction, commonly used for the characterization of such minerals, due to the tiny changes in scattering factor values, can be override looking at the solid-state NMR profile of the main heteroatoms [

18]. In fact, Si and Al exhibit different giromagnetic ratios γ (6.976 10

7 rad T

-1 s

-1 for

27Al, and - 5.3188 10

7 rad T

-1 s

-1γ for

29Si), which allow to highlight even small differences in the chemical environment of the analysed nuclei.

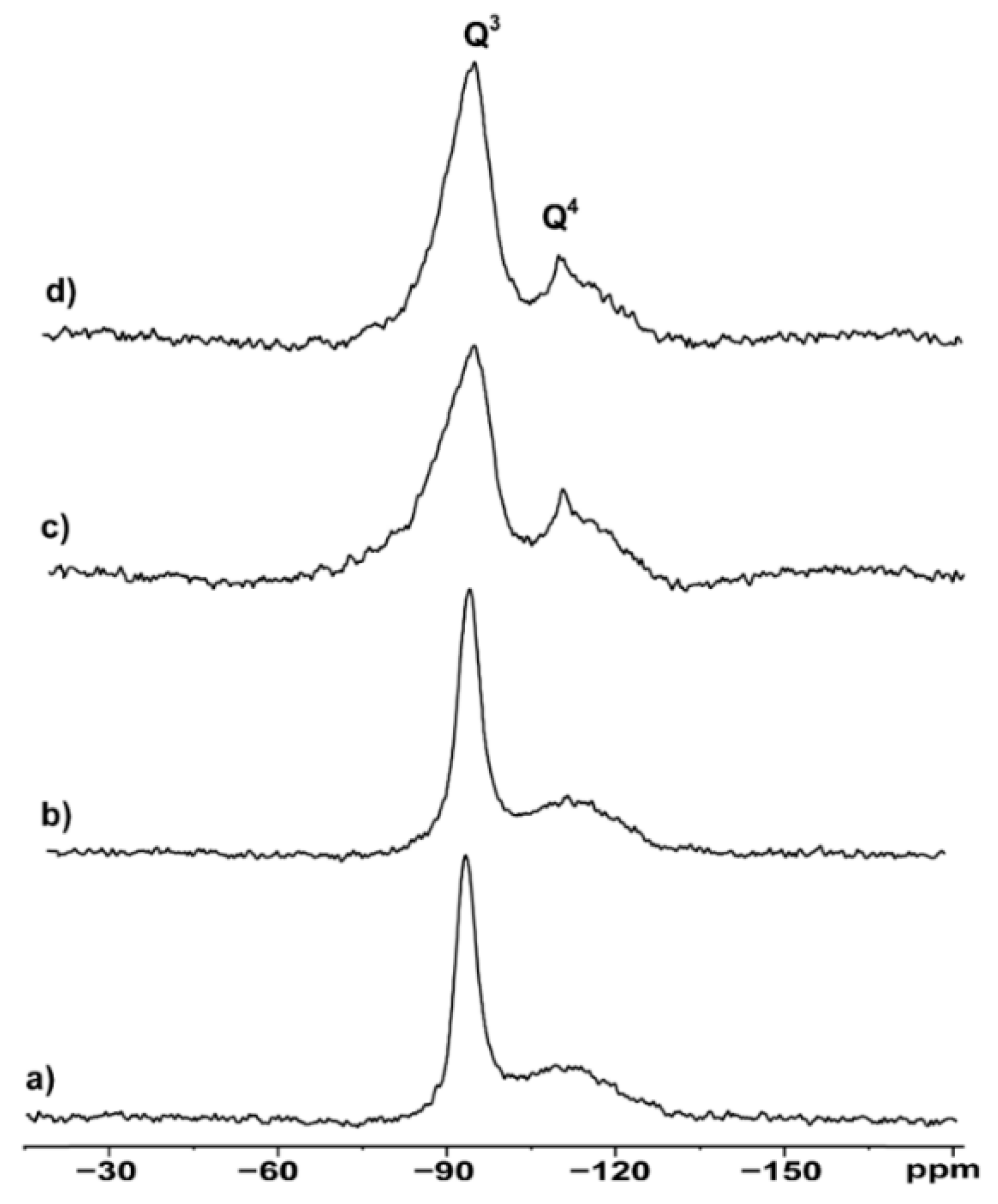

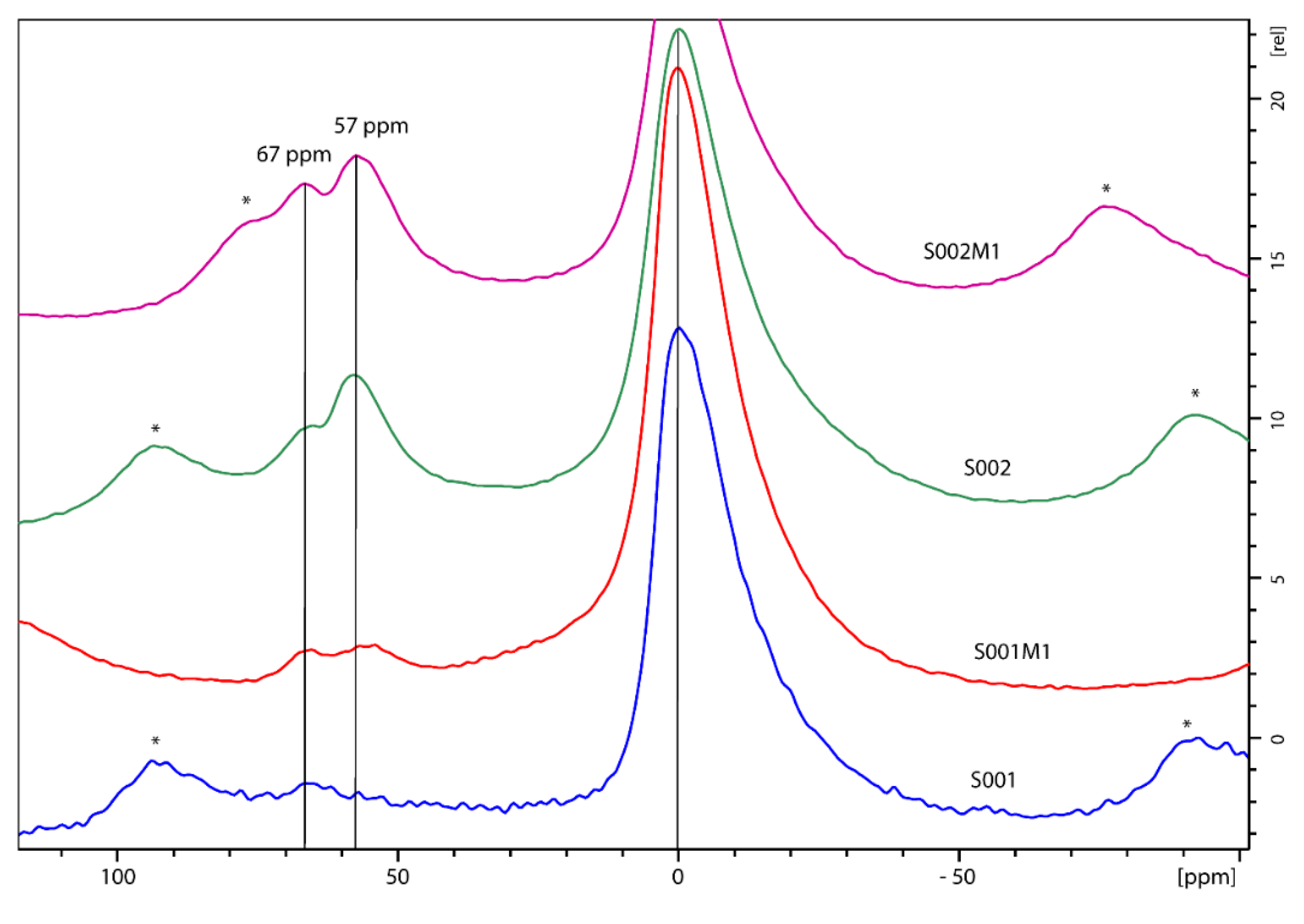

Thus,

29Si MAS NMR analysis was performed on hydrophilic and hydrophobic bentonites as received and after grinding (

Figure 3).

All spectra show a sharp peak at -93.4 ppm and a rather broad signal covering the range -105 - 115 ppm, indicating local disorder of the Si environment in the 3D structure. According to the classic nomenclature and peak assignment proposed by Lippmaa et al. [

19], the

29Si SS NMR signals of

Figure 3 are labelled as Q3 and Q4, respectively. Q3 refers to “chain branching sites”, Si(OAl)(OSi)

2OH in our case, whereas Q4 is associated to the “three-dimensional cross-linked framework” of the fully condensed Si(OAl)(OSi)

3 frame, usually present in the tetrahedral layers of the clay [

20]. After deconvolution of the spectral region containing the Q3 and Q4 signals, the peak’s width as well as the absolute area ratios (Q4/Q3) were estimated and reported in

Table 1.

Hydrophilic bentonite shows a sharper Q3 signal compared to the hydrophobic one (491 Hz vs 834 Hz) and a lower Q4/Q3 ratio (0.137 vs 0.190). The higher Q4/Q3 ratio observed in the hydrophobic samples compared to the hydrophilic counterparts can be related to their lower Brönsted acidity compared to the hydrophilic ones. The rational is in the assignment of Q3 as containing the contribution of the Si-OH sites, responsible for the acidity. The effect of the ball milling procedure is evaluated by comparing the suitable spectra of

Figure 3: a) vs b) for hydrophilic bentonites, and c) vs d) for hydrophobic bentonites. The data highlight that grinding is not affecting the chemical structure – no chemicals shift changes observed – but rather increases, in a selective manner, the structural disorder of the materials, as pointed out by the linewidth (LW) values. The variation, appreciable on Q4 especially, can be expressed as D

LW (Q4) = LW(Q4)

milled – LW(Q4)

not milled for both the hydrophilic and the hydrophobic materials. The experimental data lead to D

LW (Q4)

hydrophilic = 9 Hz and D

LW (Q4)

hydrophobic = 55 Hz, providing evidence of a more effective morphological changes in hydrophobic samples upon mechanical stress.

To provide an exhaustive overview about the chemical structure of the clays, also

27Al MAS spectra were acquired (

Figure 4).

The experimental spectra show the presence of peaks in two regions: from 70 to 50 ppm, and from -25 to +25 ppm corresponding, respectively, to Al in tetrahedral (Al

IV) and octahedral (Al

VIII) forms (

Figure 4 and

Table 2) [

21]. It is known that the presence of Al in the tetrahedral frameworks increases the Brönsted acidity of the material [

22]. Also, two different peaks in the Al tetrahedral region can be encountered which correspond, respectively, to Al sites in layered bentonite (peak at around 70 ppm), and to Al characteristic of fully condensed sites (55-59 ppm) [

23]. The relative percentages of the areas of each peak are reported, along with the corresponding chemical shift, in

Table 2.

Looking at the data relative to the four bentonite samples analysed, it is possible to draw the following considerations. Hydrophilic bentonite (commercial) shows just octahedral Al sites (> 91%) with about 8% of tetrahedral Al layered sites. After ball milling about half of the layered sites are converted in fully condensed ones. The chemical shift in this case for the fully compacted sites (about 56 ppm) is slightly anomalous as it should be close to 70 ppm. Thus, it can’t be excluded that this new peak corresponds to layered sites (not fully condensed) arranged in a different way with respect to the original ones. However, a clear effect, concentrated on the tetrahedral Al sites, of the milling procedure is observed for hydrophilic bentonite. On the other hand, hydrophobic bentonites show all the three configurations with a distribution between octahedral, tetrahedral layered and tetrahedral fully condensed which seems to be not affected by the ball milling procedure. Independently of the milling procedure, it is possible to understand the different behaviour of the two types of bentonites (hydrophilic and hydrophobic) by considering their octahedral/tetrahedral sites ratio which is respectively about 92/8 and 75/25. As reported by Vajglova and coworkers [

21], the presence of Al in the tetrahedral frameworks increases the Brönsted acidity of the material, thus, the bentonite sold under the label hydrophobic differs from the hydrophilic one as it has a consistent increased number of Bronsted acidic sites.

3.3. Design of Experiments (DoE)

Design of Experiments (DoE)

Once relevant structural differences between the considered bentonites were highlighted by solid-state NMR spectroscopy, a Simplex-Lattice Design of Experiments (DoE)[

24,

25] was used to build a viable statistical model describing the effect of the specific bentonite used on the pour point of the processed oil. According to the DoE, four experiments were conducted and for each one, the responses volatile content (VC) and Pour Point (PP) were determined (

Table 3).

Regarding the volatile content, it was determined by SPME GC-MS analysis which provided a semiquantitative assessment of several chemicals in different relative amount (

Table 4).

The general chemical composition of the volatile fraction of the oil prior and after treatment with bentonite is in agreement with previous reported HS-SPME GC/MS data relative to similar matrixes [

6]. Looking at the main organic volatile compounds (VOCs) detected and reported in

Table 4, it is possible to explain the presence of many organic compounds as aldehydes and acids as result of food leaching [

26], the Maillard reaction, oxidation promoted by temperature, and hydrolysis of triglycerides [

27]. Furthermore, regarding the aldehydes profile, the autoxidation of linoleic acid has been reported as source of dienals (2,4-heptadienal or 2,4-decadienal), and alkenals (2-undecenal, 2-decenal, and 2-octenal) [

28].

To better compare the outcomes of the different treatments in terms of variation of the volatile profile, the detected compounds have been grouped in chemical families and resumed in

Table 5, also integrated by the PP values for each sample.

Looking at the data reported in

Table 5, the most evident difference within starting oil TQ and treated ones is relative to the PP, which consistently improves from -2 °C to about -10 °C for samples treated with bentonites S002, S002M1, and S001M1, and reaching -16.5 °C after processing with bentonite S001. The 6.5 °C drop from treated samples with hydrophobic bentonite (S002 series) to S001 is indicative of a specific ability of the hydrophilic bentonite to remove some chemicals. It is known that water molecules in waste vegetable oil samples are better removed by hydrophilic bentonites and by increasing the specific surface area can enhance this phenomenon [

11]. Nevertheless, herein we observe an inverse trend as the not milled hydrophilic bentonite is much more efficient that the milled one (S001 vs S001M1). The latter conclusion seems to be in contrast with published data[

4], anyway it should be considered that when recycled vegetable oil is treated, a low tenor of water (0.4 wt% from Karl-Fischer titration) is present than in raw used vegetable oil. In such environment, the action of the bentonite is related to trapping organic molecules without been saturated by water as happened with waste cooking oils [

4]. It is known also that the absorption process of porous materials is a combination of pore inclusion (determined by the pore sizes) and interaction between polar/non-polar groups. Regarding the differences in morphology, the

29Si MAS NMR showed sharper Q3 signals in hydrophilic bentonites with respect to hydrophobic ones, meaning that hydrophilic bentonites have less contribution of Si(OAl)(OSi)

2OH phases in their structure. Also, the enlargement of the peaks in milled samples suggests a decrease of the crystallinity due to the ball milling process. On the other side, the

27Al MAS spectra revealed that milled bentonites have a high-density packed structure (increasing of the Al

IV peak). Thus, it seems that the combination between the reduced number of O-H groups and the more tiny and regular structure are responsible of the better performances of S001 with respect to the other clays in removing organic contaminants.

Looking at the table 2 it is possible to pick some insights about the specific chemical groups retained during the four processes. By comparing the columns 1 and 2 (hydrophilic bentonites) with 3, and 4 (hydrophobic bentonites), a reduction in the relative amounts of ketones, acids, alcohols, and alkanes is observed after processing with hydrophobic bentonites. Considering that hydrophobic bentonites have less -OH groups, it is possible to attribute this behaviour to physical retention of the low molecular weight contaminants.

Looking for differences between milled and non-milled hydrophilic bentonites, the most relevant difference lay into the relative amounts of ketones and alcohols which are reduced in S001 treated samples (not milled). It is possible to relate this outcome to the reduction of the AlIV signal intensity in S001 processed oils (27Al MAS spectra). Again, an indication of a relevant impact of the structural organization of the clay on the specific chemical group retention ability.

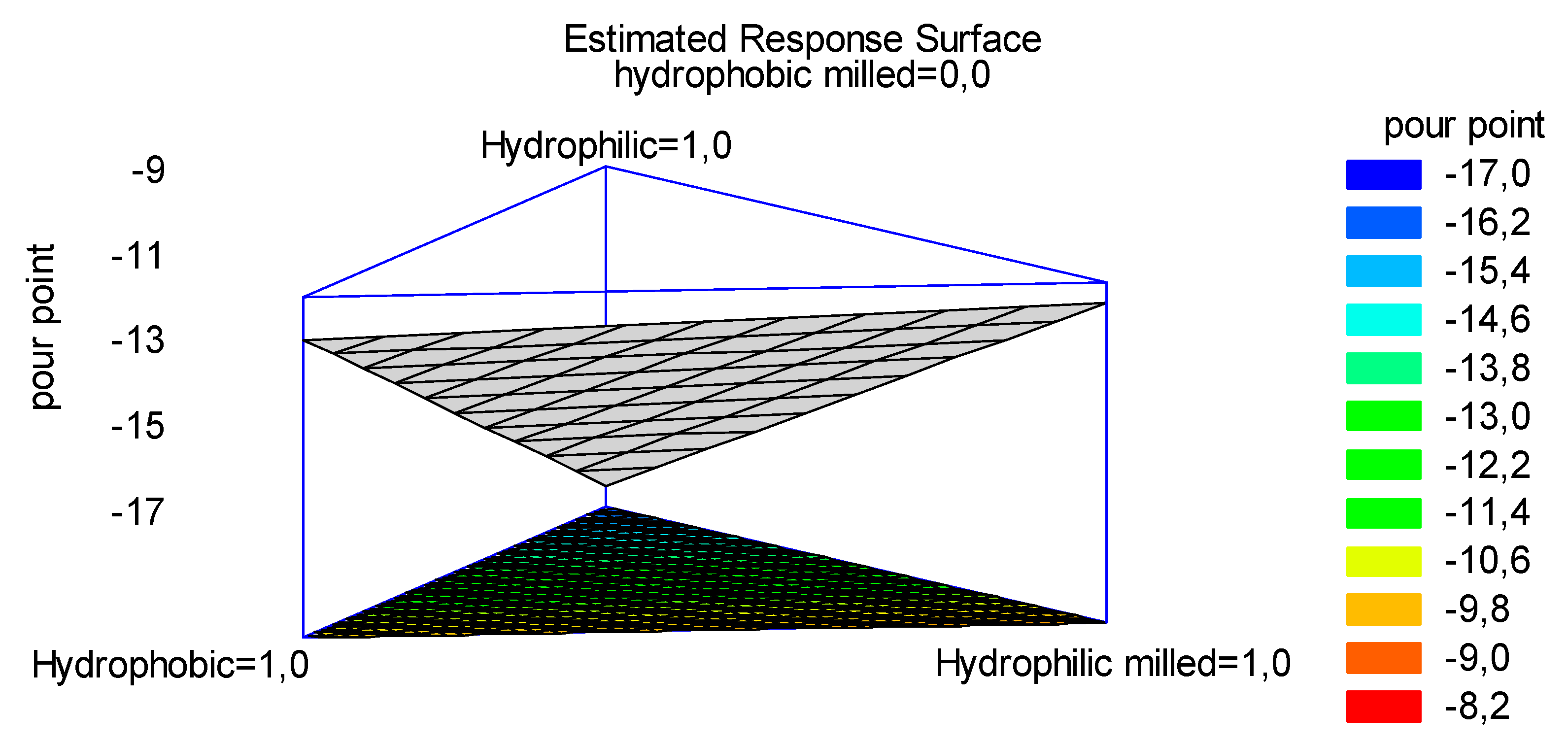

3.4. Optimization by Statistical Multivariate Analysis

According with simple lattice DoE, four experiments were conducted and the variation of the PP depending on the composition of the bentonite employed was expressed in a surface plot as reported in

Figure 6.

Looking at the plot in

Figure 6 it is possible to follow the variation of the PP in the oil treated with different bentonites. If the lower PP is desirable, hydrophilic non-milled bentonite should be used. By looking at the red and dark-orange areas on the top of the triangle, it is possible to estimate that even a mixture of hydrophilic non-milled and hydrophobic (milled or not) bentonites should guarantee a PP within -15 and -17 °C.

In the end, it was highlighted how even small differences in the structure of the clay can determine sensible variation in the ability of the material to effectiveness remove undesired chemical from recycled vegetable oils. This experimental evidence, open to a wide range of customization possibilities if mixtures of different clays are considered.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the effectiveness of four bentonites—two commercial types (hydrophilic and hydrophobic) and two modified via 60 minutes of ball milling—in processing a refined mixture of triglycerides from waste sources. The chemical structures of these bentonite powders were thoroughly characterized using FT-IR and solid-state 29Si and 27Al NMR spectroscopies.

The 29Si solid-state NMR results provided additional insights, particularly in the form of an increased Q4/Q3 ratio, highlighting the structural variations between the hydrophilic (S001) and hydrophobic (S002) bentonites. Furthermore, 27Al solid-state NMR revealed significantly lower intensity in the AlIV signal in hydrophilic bentonite after milling (comparing S001 with the milled sample S001M1). These findings fill a critical gap left by prior studies using X-ray diffraction, SEM, and TEM, which could not capture consistent differences in the chemical structures of the materials.

Equipped with this comprehensive structural characterization, the bentonites were employed as adsorbents in the treatment of recycled vegetable oil. Gas chromatography of the volatile fractions showed a higher affinity of the hydrophobic bentonite S001 for trapping ketones, along with a superior capacity to retain ketones and alcohols compared to its milled counterpart, S001M1. Additionally, the pour point (PP) was used as a further indicator of the bentonites’ ability to retain impurities during oil treatment. A Simplex-Lattice design of experiments, combined with multivariate analysis, was applied to develop a predictive model capable of estimating the PP of treated vegetable oil based on the specific bentonite employed.

Overall, this study underscores the critical role of bentonite morphology and chemical structure, as characterized by solid-state NMR techniques, in determining their efficiency in trapping volatile organic compounds, which is related to the acidic characteristic of the material. Solid-state NMR, in particular, proved invaluable in detecting subtle yet significant differences in the structural features of bentonites, offering insights that could guide the optimization of clays for industrial applications involving VOC adsorption.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.P. and A.M.; methodology, G.L.P., A.M. and F.C.; validation, A.M., S.G.; investigation, S.C., F.C.; resources, S.G., An.M.; data curation, A.M., An.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.P., A.M., An.M., and F.C.; writing—review and editing, A.M., and An.M.; supervision, G.L.P., S.G.; funding acquisition, An.M., S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

The present work was funded by the WORLD Project-RISE, a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, under the Marie Skłodowska- Curie, Grant Agreement No. 873005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cárdenas, J.; Orjuela, A.; Sánchez, D.L.; Narváez, P.C.; Katryniok, B.; Clark, J. Pre-treatment of used cooking oils for the production of green chemicals: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A.; Ferro, M.; Dugoni, G.C.; Panzeri, W.; Petretto, G.L.; Urgeghe, P.; Mele, A. Improving the recycling technology of waste cooking oils: Chemical fingerprint as tool for non-biodiesel application. Waste Manag. 2019, 96, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannu, A.; Garroni, S.; Porras, J.I.; Mele, A. Available Technologies and Materials for Waste Cooking Oil Recycling. Processes 2020, 8, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A.; Flores, P.A.; Vangosa, F.B.; Di Pietro, M.E.; Mele, A. Sustainable production of raw materials from waste cooking oils. RSC Sustain. 2024, 3, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A.; Poddighe, M.; Garroni, S.; Malfatti, L. Application of IR and UV–VIS spectroscopies and multivariate analysis for the classification of waste vegetable oils. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 178, 106088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A.; Vlahopoulou, G.; Urgeghe, P.; Ferro, M.; Del Caro, A.; Taras, A.; Garroni, S.; Rourke, J.P.; Cabizza, R.; Petretto, G.L. Variation of the Chemical Composition of Waste Cooking Oils upon Bentonite Filtration. Resources 2019, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Jiang, K.; Liu, L.; Yan, N.; Farag, M.A.; Liu, L. ; Dissecting Maillard reaction production in fried foods: Formation mechanisms, sensory characteristic attribution, control strategy, and gut homeostasis regulation. Food Chemistry, 2024, 438, 137994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; You, L.; Ji, C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Geng, D.; Gao, S.; Bi, Y.; Luo, R. Formation of volatile flavor compounds, maillard reaction products and potentially hazard substance in China stir-frying beef sao zi. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuek, S.L.; Tarmizi, A.H.A.; Razak, R.A.A.; Jinap, S.; Norliza, S.; Sanny, M. Contribution of lipid towards acrylamide formation during intermittent frying of French fries. 2020, 118, 107430. [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A.; Di Pietro, M.E.; Petretto, G.L.; Taleb, Z.; Serouri, A.; Taleb, S.; Sacchetti, A.; Mele, A. Recycling of used vegetable oils by powder adsorption. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2022, 41, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulas, G.; Garroni, S.; Mannu, A.; Vlahopoulou, G.; Sireus, V.; Petretto, G.L. ; Bentonite as a Refining Agent in Waste Cooking Oils Recycling: Flash Point, Density and Color Evaluation, Natural Product Communication, 2018, 13(5), 613-616.

- Mannu, A.; Poddighe, M.; Mureddu, M.; Castia, S.; Mulas, G.; Murgia, F.; Di Pietro, M.E.; Mele, A.; Garroni, S. Impact of morphology of hydrophilic and hydrophobic bentonites on improving the pour point in the recycling of waste cooking oils. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Del Dool, H.; Kartz, P.D. ; A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J. Chrom. A, 1963, 11, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R.K.; Becker, E.D.; de Menezes, S.M.C.; Goodfellow, R.; Granger, P. NMR Nomenclature. Nuclear Spin Properties and Conventions for Chemical Shifts - (IUPAC Recommendations 2001). Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 1795−1818. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, H.H. ; Chapter 6 Bentonite Applications, Developments in Clay Science, 2006, 2, 111-130.

- Available at https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IT/it/product/sigald/285234. Accessed on , 2024. 12 December.

- Hayati-Ashtiani, M. Use of FTIR Spectroscopy in the Characterization of Natural and Treated Nanostructured Bentonites (Montmorillonites). Part. Sci. Technol. 2012, 30, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavón, E.; Alba, M.D. ; Swelling layered minerals applications: A solid state NMR overview. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, 2021, 124-125, 99-128.

- Lippmaa, E.; Magi, M.; Samoson, A.; Engelhardt, G.; Grimmer, A.-R. ; Structural studies of silicates by solid-state high-resolution 29Si NMR, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 4889–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.H.; Kim, H.K.; Chang, H.; Lee, J.S. Nafion/Sulfonated Montmorillonite Composite: A New Concept Electrolyte Membrane for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Arimitsu, N.; Kameshima, Y.; Nakajima, A.; MacKenzie, K.J. Solid acidity of 2:1 type clay minerals activated by selective leaching. Appl. Clay Sci. 2005, 31, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajglová, Z.; Kumar, N.; Peurla, M.; Peltonen, J.; Heinmaa, I.; Murzin, D.Y. Synthesis and physicochemical characterization of beta zeolite–bentonite composite materials for shaped catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 6150–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, T.; Norden, G.; Justnes, H. Characterisation of calcined raw clays suitable as supplementary cementitious materials. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 162, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloyede, C.T.; Jekayinfa, S.O.; Alade, A.O.; Ogunkunle, O.; Laseinde, O.T.; Adebayo, A.O.; Abdulkareem, A.I.; Smaisim, G.F.; Fattah, I. Synthesis of Biobased Composite Heterogeneous Catalyst for Biodiesel Production Using Simplex Lattice Design Mixture: Optimization Process by Taguchi Method. Energies 2023, 16, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monton, C.; Wunnakup, T.; Suksaeree, J.; Charoenchai, L.; Chankana, N. Investigation of the Interaction of Herbal Ingredients Contained in Triphala Recipe Using Simplex Lattice Design: Chemical Analysis Point of View. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, E.; Min, D.B. ; Chemistry of Deep-Fat Frying Oils. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R77–R86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Sun, Z.; Hu, X.; Shen, Q.; Wu, J. Authentication of edible vegetable oils adulterated with used frying oil by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.M.; Chen, S.Y. Volatile compounds in oils after deep frying or stir frying and subsequent storage. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1992, 69, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of hydrophilic S001 (black line, lower spectrum) and hydrophobic S002 (red line, upper spectrum) bentonites.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of hydrophilic S001 (black line, lower spectrum) and hydrophobic S002 (red line, upper spectrum) bentonites.

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of hydrophilic (a) and hydrophobic (b) bentonite subjected to ball milling process (0, 30, 60, and 120 min.).

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of hydrophilic (a) and hydrophobic (b) bentonite subjected to ball milling process (0, 30, 60, and 120 min.).

Figure 3.

29Si MAS NMR spectra of a) hydrophilic bentonite S001, b) ball milled hydrophilic S001M1, c) hydrophobic bentonite S002, d) ball milled hydrophobic bentonite S002M1.

Figure 3.

29Si MAS NMR spectra of a) hydrophilic bentonite S001, b) ball milled hydrophilic S001M1, c) hydrophobic bentonite S002, d) ball milled hydrophobic bentonite S002M1.

Figure 4.

27Al MAS NMR spectra of a) hydrophilic bentonite S001, b) ball milled hydrophilic bentonite S001M1, c) hydrophobic bentonite S002, d) ball milled hydrophobic bentonite S002M1. Spinning sidebands are marked with a *.

Figure 4.

27Al MAS NMR spectra of a) hydrophilic bentonite S001, b) ball milled hydrophilic bentonite S001M1, c) hydrophobic bentonite S002, d) ball milled hydrophobic bentonite S002M1. Spinning sidebands are marked with a *.

Figure 6.

Contours of the estimated response surface.

Figure 6.

Contours of the estimated response surface.

Table 1.

29Si SS NMR Spectral data for samples of bentonite hydrophilic and hydrophobic (prior and after milling). LW indicates the NMR linewidth (Hz) measured at half-height. Q4/Q3 indicates the peak integral ratio as obtained from peak deconvolution.

Table 1.

29Si SS NMR Spectral data for samples of bentonite hydrophilic and hydrophobic (prior and after milling). LW indicates the NMR linewidth (Hz) measured at half-height. Q4/Q3 indicates the peak integral ratio as obtained from peak deconvolution.

| Spectrum |

Sample |

LW Q3 (Hz) |

LW Q4 (Hz) |

Q4/Q3 ratio |

| A |

hydrophilic (S001) |

491 |

345 |

0.137 |

| B |

hydrophilic milled (S001M1) |

489 |

354 |

0.150 |

| C |

hydrophobic (S002) |

834 |

476 |

0.190 |

| D |

hydrophobic milled (S002M2) |

841 |

531 |

0.186 |

Table 2.

27Al SS NMR Spectral data for samples of bentonite hydrophilic and hydrophobic (prior and after milling).

Table 2.

27Al SS NMR Spectral data for samples of bentonite hydrophilic and hydrophobic (prior and after milling).

| Bentonite |

octahedral |

d

(ppm)

|

Al sites

fully condensed

|

d

(ppm)

|

Al sites

in layered bentonite

|

d

(ppm)

|

| S001 |

91.63% |

0.25 |

0% |

- |

8,36% |

69.32 |

| S001M1 |

91,61% |

0.87 |

4,22% |

55.70 |

4,15% |

55.97 |

| S002 |

74.50% |

0.10 |

13.76% |

58.45 |

11.70% |

68.54 |

| S002M1 |

74.50% |

0.10 |

13.76% |

58.45 |

11.70% |

68.54 |

Table 3.

List of experiments conducted and relative details.

Table 3.

List of experiments conducted and relative details.

| Experiment |

bentonite |

Response 1 |

Response 2 |

| 1 |

S002M1 |

PP* |

VC** |

| 2 |

S002 |

PP* |

VC** |

| 3 |

S001M1 |

PP* |

VC** |

| 4 |

S001 |

PP* |

VC** |

Table 4.

Semiquantitative volatiles’ profile for the triglycerides mixture prior to bentonite treatment (TQ), and oil samples treated respectively with bentonites S001 (hydrophilic), S001M1 (hydrophilic milled), S002 (hydrophobic), and S002M1 (hydrophobic milled).

Table 4.

Semiquantitative volatiles’ profile for the triglycerides mixture prior to bentonite treatment (TQ), and oil samples treated respectively with bentonites S001 (hydrophilic), S001M1 (hydrophilic milled), S002 (hydrophobic), and S002M1 (hydrophobic milled).

| Compound |

Retention Times (RT) * |

TQ |

S001 |

S001M1 |

S002 |

S002M1 |

| Pentanal |

3.87 |

1.09 |

0.87 |

1.27 |

0.30 |

0.75 |

| Hexanal |

6.63 |

12.02 |

9.32 |

17.82 |

9.22 |

6.55 |

| 2-Hexenal, (E)- |

10.68 |

0.43 |

0.33 |

0.51 |

0.06 |

0.26 |

| Heptanal |

9.69 |

1.21 |

0.85 |

1.80 |

0.04 |

0.58 |

| Octanal |

12.81 |

3.10 |

2.48 |

3.59 |

1.15 |

1.14 |

| 2-Heptenal, (Z)- |

13.82 |

9.54 |

8.37 |

10.00 |

5.94 |

5.94 |

| 2-Octenal, (E)- |

16.68 |

4.13 |

3.69 |

3.82 |

2.85 |

2.83 |

| Nonanal |

15.77 |

8.37 |

8.05 |

7.17 |

5.60 |

4.30 |

| 2-Nonenal, (E)- |

19.36 |

1.08 |

1.25 |

0.93 |

1.33 |

1.24 |

| 2-Decenal, (Z)- |

22.00 |

5.73 |

9.22 |

3.82 |

8.59 |

8.92 |

| 2,4-Decadienal, (E,E)- |

25.74 |

3.23 |

7.92 |

2.90 |

8.69 |

10.14 |

| 2-Undecenal |

24.44 |

3.23 |

5.42 |

2.05 |

6.41 |

6.97 |

| 2-Heptanone |

9.61 |

1.36 |

0.53 |

2.00 |

0.12 |

0.33 |

| 2-Octanone |

12.68 |

1.10 |

0.65 |

1.35 |

0.37 |

0.25 |

| Total ketones |

|

2.46 |

1.19 |

3.35 |

0.48 |

0.59 |

| Acetic acid |

17.83 |

4.00 |

7.31 |

6.34 |

9.67 |

10.59 |

| Butanoic acid |

22.34 |

2.12 |

1.41 |

2.09 |

2.61 |

1.94 |

| Pentanoic acid |

24.79 |

4.38 |

5.19 |

3.58 |

5.37 |

5.42 |

| Hexanoic acid |

27.12 |

15.25 |

11.35 |

11.30 |

15.45 |

16.01 |

| Heptanoic acid |

30.06 |

1.07 |

0.98 |

0.55 |

1.71 |

2.15 |

| Octanoic Acid |

32.21 |

0.60 |

0.95 |

0.28 |

1.61 |

1.70 |

| Nonanoic acid |

33.81 |

0.32 |

0.59 |

0.13 |

1.24 |

0.94 |

| 1-Pentanol |

11.86 |

1.17 |

0.83 |

1.32 |

0.84 |

0.61 |

| 1-Hexanol |

14.80 |

4.12 |

2.03 |

5.73 |

1.89 |

1.73 |

| 1-Octen-3-ol |

17.40 |

3.17 |

2.06 |

2.88 |

0.96 |

0.91 |

| 1-Heptanol |

17.52 |

1.28 |

0.85 |

1.58 |

0.60 |

0.72 |

| 2-Hepten-1-ol, (E)- |

18.94 |

1.03 |

0.60 |

1.10 |

0.68 |

0.48 |

| 1-Octanol |

20.06 |

3.27 |

4.92 |

1.17 |

5.72 |

6.28 |

| Dodecane |

10.02 |

0.99 |

0.67 |

0.65 |

0.19 |

0.14 |

Table 5.

Semiquantitative assessment of the main composition of samples TQ (prior to bentonite treatment), S001 (hydrophilic bentonite), S001M1 (milled hydrophilic bentonite), S002 (hydrophobic bentonite), S002M1 (milled hydrophobic bentonite), and PP values.

Table 5.

Semiquantitative assessment of the main composition of samples TQ (prior to bentonite treatment), S001 (hydrophilic bentonite), S001M1 (milled hydrophilic bentonite), S002 (hydrophobic bentonite), S002M1 (milled hydrophobic bentonite), and PP values.

| Volatiles |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| |

TQ |

S001 |

S001M1 |

S002 |

S002M1 |

| Aldehydes |

53.15 |

57.78 |

55.71 |

50.17 |

49.62 |

| Ketones |

2.46 |

1.19 |

3.35 |

0.48 |

0.59 |

| Acids |

27.73 |

27.77 |

24.26 |

37.64 |

38.76 |

| Alcohols |

14.04 |

11.30 |

13.79 |

10.68 |

10.74 |

| Alkanes |

0.99 |

0.67 |

0.65 |

0.19 |

0.14 |

| Pour Point (PP, °C) |

|

-2 °C |

-16.5 |

-9.5 |

-10 |

-10 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).