Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

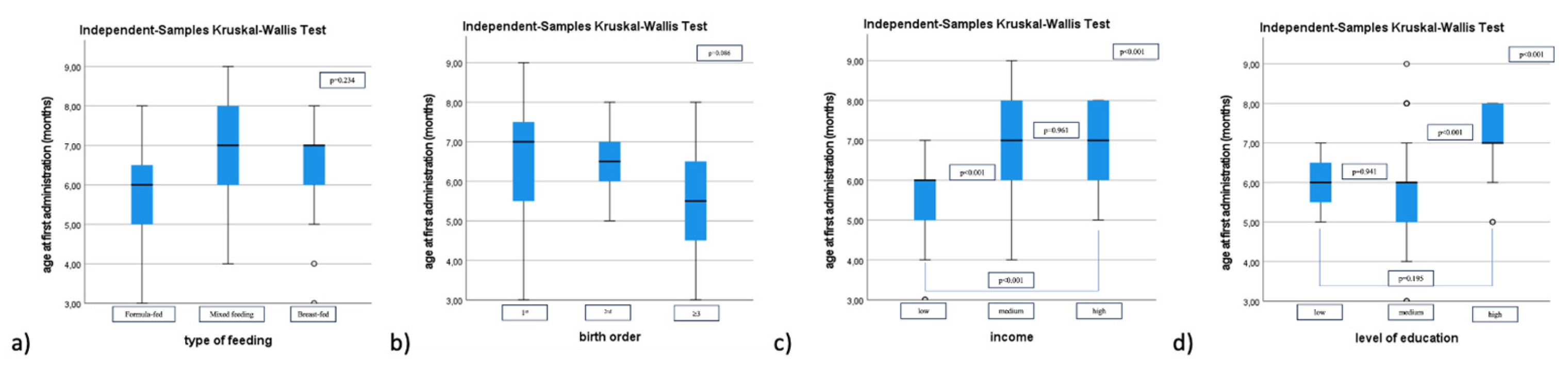

Background/Objectives: Good feeding practices beginning early in life and are crucial for preventing all forms of malnutrition and non-communicable diseases. This time frame encompasses the delicate phase of complementary feeding, which traditionally involved homemade meals. The use of commercial complementary foods (CCF) began more than a century ago and represents a convenient alternative. We aim to outline both the profile of CCF consumers while accurately describe CCF dietary patterns. Materials and Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study analysing a final cohort of 75 infants 6-12 months admitted for various respiratory or gastrointestinal conditions to the Paediatrics Department of the "Grigore Alexandrescu" Emergency Hospital for Children in Bucharest, Romania, from June 2024 to December 2024. The mothers were requested to complete a two-section questionnaire. The first section elicited information on: child demographics, feeding patterns, nutritional status, ma-ternal educational level and monthly family income. The second section focused spe-cifically on the utilization of commercial baby food products. Results: Eighty percent of the study population consumed at least once a CCF product, p< 0.001. The CCF products were divided in 6 categories: milk-based products, cereals, pseudocereals, fruit jars/pouches, vegetables puree and meat jars and biscuits and pastas (flour-based products) similar to the one from European Commission. First administered products were in order of their distribution: biscuits and pastas in 16 infants (26.7%), fruits puree in 14 infants (23.3 %), cereals (including pseudocereals) in 12 infants (20%) and yogurt and vegetables/vegetables with meat jars, each in 9 infants (15%), p=0,530. Median [IQR] age at first administration of a CCF product is 6 months [5.25-7]. CCF consumption was not overall influenced by family income or educational level; however, at an in-dividual level, we identified pseudocereals consume associated with higher education and income (p=0.008 respectively p=0.011). Amongst the most utilised vegetables were sweet potatoes, carrots, zucchini, among the fruits were apples and banana and chicken-meat was the most offered. Overall perception of mothers on CCF was fa-vourable, within the motivations and advantages of using them being their diversity and convenience. Conclusion: CCF are intensely utilized in our country. Regarding the composition of these products, there is a combination between traditions and new di-etary tendencies. Longitudinal, further studies, are necessary to characterize the long-term effects of this feeding pattern.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Improving the Nutritional Quality of Commercial Foods for Infants and Young Children in the WHO European Region. Available online: Https://Www.Who.Int/Europe/Publications/i/Item/WHO-EURO-2019-3593-43352-60816 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.; Kearney, J.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; Pelaez, C.; et al. Appropriate Age Range for Introduction of Complementary Feeding into an Infant’s Diet. EFSA Journal 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewtrell, M.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellöf, M.; Embleton, N.; Fidler Mis, N.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.M.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; et al. Complementary Feeding. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017, 64, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Guideline for Complementary Feeding of Infants and Young Children 6-23 Months of Age. World Health Organization;WHO. 2023. Available online: Https://Iris.Who.Int/Bitstream/Handle/10665/373358/9789240081864-Eng.Pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO) Guideline on the Complementary Feeding of Infants and Young Children Aged 6−23 Months 2023: A Multisociety Response. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2024, 79, 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Adrados, A.; Fernández-Leal, A.; Martínez-Pérez, J.; Delgado-Ojeda, J.; Santamaría-Orleans, A. Clinically Relevant Topics and New Tendencies in Childhood Nutrition during the First 2 Years of Life: A Survey among Primary Care Spanish Paediatricians. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congiu, M.; Cimador, V.; Bettini, I.; Rongai, T.; Labriola, F.; Sbravati, F.; Marcato, C.; Alvisi, P. What Has Changed over Years on Complementary Feeding in Italy: An Update. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: Https://Solidstarts.Com/History-of-Baby-Food (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Hässig-Wegmann, A.; Hartmann, C.; Roman, S.; Sanchez-Siles, L.; Siegrist, M. Beliefs, Evaluations, and Use of Commercial Infant Food: A Survey among German Parents. Food Research International 2024, 194, 114933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, E.; Parrilla, R.; Tárrega, A. The Difficult Decision of Buying Food for Others: Which Puree Will My Baby Like? Food Research International 2024, 179, 114018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: Https://Www.Researchandmarkets.Com/Report/Baby-Food.

- Capra, M.E.; Decarolis, N.M.; Monopoli, D.; Laudisio, S.R.; Giudice, A.; Stanyevic, B.; Esposito, S.; Biasucci, G. Complementary Feeding: Tradition, Innovation and Pitfalls. Nutrients 2024, 16, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.K. Does Breastfeeding Shape Food Preferences Links to Obesity. Ann Nutr Metab 2017, 70, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Https://Www.Who.Int/Europe/Publications/i/Item/9789289057783.

- Https://Www.Who.Int/Europe/Publications/i/Item/WHO-EURO-2022-6681-46447-67287.

- Hollinrake, G.; Komninou, S.; Brown, A. Use of Baby Food Products during the Complementary Feeding Period: What Factors Drive Parents’ Choice of Products? Matern Child Nutr 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haszard, J.J.; Heath, A.-L.M.; Katiforis, I.; Fleming, E.A.; Taylor, R.W. Contribution of Infant Food Pouches and Other Commercial Infant Foods to the Diets of Infants: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2024, 119, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Https://Www.Who.Int/Tools/Child-Growth-Standards/Standards/Weight-for-Age.

- European Commission (2006) Commission Directive 2006/125/ EC on Processed Cereal-Based Foods and Baby Foods for Infants and Young Children. Off J Eur Union (399):16–34. Https ://Eur-Lex. Europ a.Eu/Legal -Conte Nt/EN/TXT/PDF/?Uri=CELEX :32006 L0125 &from=EN.

- Cozma-Petruţ, A.; Filip, L.; Banc, R.; Mîrza, O.; Gavrilaş, L.; Ciobârcă, D.; Badiu-Tişa, I.; Hegheş, S.C.; Popa, C.O.; Miere, D. Breastfeeding Practices and Determinant Factors of Exclusive Breastfeeding among Mothers of Children Aged 0–23 Months in Northwestern Romania. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becheanu, C.A.; T. I.F.; S.R.E.; L.G. Feeding Practices Among Romanian Children in the First Year of Life. HK J. Paediatr 2018, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung DL, P.M.L.M.H.J. Commercial or Homemade Baby Food. Can Med Assoc J. 1982, 126, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Song J, H.J.C.Y.Z.Y.L.H.W.Y.Y.H.L.Y. The Understanding, Attitude and Use of Nutrition Label among Consumers (China). Nutr Hosp. 2015, 2703–2710. [Google Scholar]

- Perrar, I.; Alexy, U.; Nöthlings, U. Cohort Profile Update–Overview of over 35 Years of Research in the Dortmund Nutritional and Anthropometric Longitudinally Designed (DONALD) Study. Eur J Nutr 2024, 63, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbig, A.; Foterek, K.; Kersting, M.; Alexy, U. Home-made and Commercial Complementary Meals in German Infants: Results of the <scp>DONALD</Scp> Study. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2015, 28, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.L.; Raza, S.; Parrett, A.; Wright, C.M. Nutritional Content of Infant Commercial Weaning Foods in the UK. Arch Dis Child 2013, 98, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, J.; Rippin, H.; Threapleton, D.; Jewell, J.; Kanamäe, H.; Salupuu, K.; Caroli, M.; Antignani, A.; Pace, L.; Vassallo, C.; et al. High Sugar Content of European Commercial Baby Foods and Proposed Updates to Existing Recommendations. Matern Child Nutr 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Https://Sp.Ukdataservice.Ac.Uk/Doc/7281/Mrdoc/Pdf/7281_ifs-Uk-2010_report.Pdf.

- Available online: Https://Economedia.Ro/G4food-Piata-de-Hrana-Pentru-Bebelusi-Din-Romania-va-Incheia-Anul-Cu-o-Valoare-de-540-de-Milioane-de-Lei-in-Crestere-Cu-7-Fata-de-2023.Html. (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Maslin, K.; Galvin, A.D.; Shepherd, S. A Qualitative Study of Mothers Perceptions of Weaning and the Use of Commercial Infant Food in the United Kingdom. Matern Pediatr Nutr 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhagen, S.; Pries, A.M.; Dissieka, R. Commercial Snack Food and Beverage Consumption Prevalence among Children 6–59 Months in West Africa. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurich, M.A. Perspective: Novel Commercial Packaging and Devices for Complementary Feeding. Advances in Nutrition 2018, 9, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koletzko, B.; Bührer, C.; Ensenauer, R.; Jochum, F.; Kalhoff, H.; Lawrenz, B.; Körner, A.; Mihatsch, W.; Rudloff, S.; Zimmer, K.-P. Complementary Foods in Baby Food Pouches: Position Statement from the Nutrition Commission of the German Society for Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ, e.V.). Mol Cell Pediatr 2019, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslin, K.; Venter, C. Nutritional Aspects of Commercially Prepared Infant Foods in Developed Countries: A Narrative Review. Nutr Res Rev 2017, 30, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foterek, K.; Hilbig, A.; Alexy, U. Associations between Commercial Complementary Food Consumption and Fruit and Vegetable Intake in Children. Results of the DONALD Study. Appetite 2015, 85, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefel, R.R.; Reidy, K.; Karwe, V.; Devaney, B. Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study: Improvements Needed in Meeting Infant Feeding Recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc 2004, 104, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, K.M.; Black, M.M. Commercial Baby Food Consumption and Dietary Variety in a Statewide Sample of Infants Receiving Benefits from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. J Am Diet Assoc 2010, 110, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidance on Ending the Inappropriate Promotion of Foods for Infants and Young Children 2016. Available online: Https://Www.Who.Int/Nutrition/Topics/Guidance-Inappropriate-Food-Promotion-Iyc/En/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Cetthakrikul, N.; Kelly, M.; Baker, P.; Banwell, C.; Smith, J. Effect of Baby Food Marketing Exposure on Infant and Young Child Feeding Regimes in Bangkok, Thailand. Int Breastfeed J 2022, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurich, M.A.; Zaragoza-Jordana, M.; Luque, V.; Gruszfeld, D.; Gradowska, K.; Xhonneux, A.; Riva, E.; Verduci, E.; Poncelet, P.; Damianidi, L.; et al. Commercial Complementary Food Use amongst European Infants and Children: Results from the EU Childhood Obesity Project. Eur J Nutr 2020, 59, 1679–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, K.C.; Bailey, R.L.; Deming, D.M.; O’Neill, L.; Carr, B.T.; Lesniauskas, R.; Johnson, W. Food Consumption Patterns and Micronutrient Density of Complementary Foods Consumed by Infants Fed Commercially Prepared Baby Foods. Nutr Today 2018, 53, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Dong, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, R.; Qu, L. Development of Weaning Food with Prebiotic Effects Based on Roasted or Extruded Quinoa and Millet Flour. J Food Sci 2021, 86, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandan, A.; Koirala, P.; Dutt Tripathi, A.; Vikranta, U.; Shah, K.; Gupta, A.J.; Agarwal, A.; Nirmal, N. Nutritional and Functional Perspectives of Pseudocereals. Food Chem 2024, 448, 139072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Zamudio, F.; Segura Campos, M.R. Amaranth, Quinoa and Chia Bioactive Peptides: A Comprehensive Review on Three Ancient Grains and Their Potential Role in Management and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 2707–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debessa, T.; Befkadu, Z.; Darge, T.; Mitiku, A.; Negera, E. Commercial Complementary Food Feeding and Associated Factors among Mothers of Children Aged 6–23 Months Old in Mettu Town, Southwest Ethiopia, 2022. BMC Nutr 2023, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirkka, O.; Abrahamse-Berkeveld, M.; van der Beek, E.M. Complementary Feeding Practices among Young Children in China, India, and Indonesia: A Narrative Review. Curr Dev Nutr 2022, 6, nzac092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, M. de los Á.; Quizhpe, J.; Ayuso, P.; Peñalver, R.; Nieto, G. Proximate Composition, Health Benefits, and Food Applications in Bakery Products of Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas L.) and Its By-Products: A Comprehensive Review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: Https://G4food.Ro/Piata-Cartofilor-Dulci-Valoarea-Financiara-a-Importurilor-in-Romania-Este-Anul-Acesta-de-34-de-Ori-Mai-Mare-Decat-Acum-Zece-Ani-Nou-Record-in-Plan-European/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Available online: Https://Www.Digi24.Ro/Stiri/Economie/Agricultura/Recolta-Record-La-Cartoful-Dulce-Cultivat-in-Sudul-Romaniei-30-de-Tone-Pe-Hectar-Cu-Cat-Se-Vinde-Soiul-Coreean-Made-in-Romania-2965257?__grsc=cookieIsUndef0&__grts=57998817&__grua=8835fc9dcffff1f69fd64c4e62c988d7&__grrn=1 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Garcia, A.L.; McLean, K.; Wright, C.M. Types of Fruits and Vegetables Used in Commercial Baby Foods and Their Contribution to Sugar Content. Matern Child Nutr 2016, 12, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.J.; Roman, S.; Klerks, M.; Haro-Vicente, J.F.; Sanchez-Siles, L.M. Are Homemade and Commercial Infant Foods Different? A Nutritional Profile and Food Variety Analysis in Spain. Nutrients 2021, 13, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antignani, A.; Francavilla, R.; Vania, A.; Leonardi, L.; Di Mauro, C.; Tezza, G.; Cristofori, F.; Dargenio, V.; Scotese, I.; Palma, F.; et al. Nutritional Assessment of Baby Food Available in Italy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erratum for, Moding; et al. Variety and Content of Commercial Infant and Toddler Vegetable Products Manufactured and Sold in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 2018;107:576–83. Am J Clin Nutr 2018, 108, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.anpa.ro/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Fish-consumption_Romania-RO_FINAL_27.10.2021.pdf. Accessed on 19.02. 2025. Available online: Https://Www.Anpa.Ro/Wp-Content/Uploads/2011/07/Fish-Consumption_Romania-RO_FINAL_27.10.2021.Pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Mesch, C.M.; Stimming, M.; Foterek, K.; Hilbig, A.; Alexy, U.; Kersting, M.; Libuda, L. Food Variety in Commercial and Homemade Complementary Meals for Infants in Germany. Market Survey and Dietary Practice. Appetite 2014, 76, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimming, M.; Mesch, C.M.; Kersting, M.; Libuda, L. Fish and Rapeseed Oil Consumption in Infants and Mothers: Dietary Habits and Determinants in a Nationwide Sample in Germany. Eur J Nutr 2015, 54, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; de Vries, J.H.; Franco, O.H.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Raat, H.; de Jongste, J.C.; Moll, H.A. Fish Consumption in Infancy and Asthma-like Symptoms at Preschool Age. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kull, I.; Bergström, A.; Lilja, G.; Pershagen, G.; Wickman, M. Fish Consumption during the First Year of Life and Development of Allergic Diseases during Childhood. Allergy 2006, 61, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexy, U.; Dilger, J.J.; Koch, S. Commercial Complementary Food in Germany: A 2020 Market Survey. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-Santos, J.; da Silva, L.A.; Lourenço, C.A.M.; Rosim, R.E.; de Oliveira, C.A.F.; Monteiro, S.H.; Vanin, F.M. Assessment of Quality and Safety Aspects of Homemade and Commercial Baby Foods. Food Research International 2023, 174, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlihan, J.; Brody, C. (2022). Is Homemade Baby Food Better? A New Investigation: Tests Compare Toxic Heavy Metal Contamination in Homemade versus Store-Bought Foods for Babies. Healthy Babies Bright Futures. Available online: Https://Hbbf.Org/Report/Is-Homemade-Baby-Food-Better (accessed on 19 February 2025).

| CCF positive n = 60 (80) |

CCF negative n = 15 (20) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex [n (%)] | 0.506 | ||

| Male | 38 (63.3%) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Female | 22 (36.7%) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Median age at inclusion, months [IQR] | 8 [7,8,9,10] | 7 [6,7,8,9] | 0.451 |

| Median age at CF, months [IQR] | 6 [5,6] | 6 [6] | 0.275 |

| Mean mother’s age, years [SD] | 28.6 [±6.6] | 30.7 (±6.3) | 0.273 |

| Residence [n (%)] | 0.05 | ||

| Urban | 38 (63.3) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Rural | 22 (36.7) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Birth order [n (%)] | 0.167 | ||

| 1st | 32 (53.3) | 9 (60) | |

| 2nd | 16 (26.7) | 3 (20) | |

| ≥3rd | 12 (20) | 3 (20) | |

| Nutritional status [n (%)] | 0.897 | ||

| Healthy weight | 40 (66.7) | 11 (73.3) | |

| Under weight | 15 (25) | 3 (20) | |

| Overweight/obesity | 5 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Feeding type [n (%)] | 0.791 | ||

| Formula-fed | 19 (31.7) | 6 (40) | |

| Mixed-feeding | 25 (41.7) | 6 (40) | |

| Breast-fed | 16 (26.6) | 3 (20) | |

| Mother’s educational level [n (%)] | 0.686 | ||

| Unschooled | 4 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Medium level | 30 (50) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Higher education | 26 (43.3) | 6 (40) | |

| Income level, RON/month [n (%)] | 0.415 | ||

| Low, ≤ 3600 | 22 (36.7%) | 5 (33/3) | |

| Medium, 3601-6600 | 16 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | |

| High, ≥ 6601 | 22 (36.6) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Mother’s employment | 0.336 | ||

| No | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Yes | 40 (66.7) | 20 (33.3) |

| Main motivations (n=60) | [n (%)] | p-value | Causes of reluctance (n=15) |

[n (%)] | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity | 11 (18.3) | Extended shelf life | 4 (26.7) | ||

| Nutritive | 10 (16.7) | Doubtful quality | 3 (20) | ||

| Easily accepted (good palatability) | 25 (41.7) | <0.001 | Sugar/salt content | 1 (6.7) | 0.186 |

| Trusted brand | 8 (13.3) | Other | 7 (46.6) | ||

| Advertising Price |

5 (8.3) 1 (1.7) |

| Income | Education | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of CCF | Low | Medium | High | p-value | Unschooled | Medium | High | p-value |

| Cereals [n, (%)] No [n=27, (45)] |

13 (48.1) | 5 (18.5) |

9 (33.4) | 0.208 | 2 (7.4) |

15 (55.6) |

10 (37) | 0.663 |

| Yes [n=33, (55)] | 9 (27.3) | 11 (33.3) |

13 (39.4) | 2 (6) |

15 (45.5) |

16 (48.5) | ||

| Pseudocereals [n, (%)] No [n=48, (80)] |

20 (41.7) |

15 (31.3) |

13 (27) |

0.011 | 4 (8.3) |

28 (58.3) |

16 (33.4) | 0.008 |

| Yes [n=12, (20)] | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) |

9 (75) |

0 | 2 (16.7) |

10 (83.3) | ||

| Fruit purées [n, (%)] No [n=35, (58.3)] |

15 (42.9) |

8 (22.8) |

12 (34.3) |

0.481 | 3 (8.6) |

19 (54.3) |

13 (37.1) | 0.511 |

| Yes [n=25, (41.7)] | 7 (28) |

8 (32) |

10 (40) | 1 (4) |

11 (44) |

13 (52) | ||

| Vegetables/vegetables with meat jars [n, (%)] No [n=34, (56.7)] |

15 (44.1) | 9 (26.5) |

10 (29.4) | 0.314 | 3 (8.8) |

18 (52.9) |

13 (38.2) | 0.652 |

| Yes [n=26, (43.3)] | 7 (27) |

7 (27) |

12 (46) | 1 (3.9) |

12 (46,1) |

13 (50) | ||

| “Flour-based products” (biscuits and pastas) [n, (%)] No [n=21, (35)] |

8 (38.1) |

5 (23.8) |

8 (38.1) |

0.935 |

0 |

13 (62) |

8 (38) |

0.252 |

| Yes [n=39, (65)] | 14 (35.9) | 11 (28.2) |

14 (35.9) | 4 (10.3) |

17 (43.6) |

18 (46.1) | ||

| Dairy based products [n, (%)] No [n=22, (36.7)] |

7 (31.8) | 6 (27.3) |

9 (40.9) | 0.844 | 2 (9) |

10 (45.5) |

10 (45.5) | 0.769 |

| Yes [n=38, (63.3)] | 15 (39.5) | 10 (26.3) |

13 (34.2) | 2 (5.3) |

20 (52.6) |

16 (42.1) | ||

| Ingredients in CCF | Types | Utilisation [n, (%)] * |

|---|---|---|

|

Cereals N=33 |

Gluten containing | 21 (63.6) |

| Gluten-free | 8 (24.3) | |

| Both | 4 (12.1) | |

|

Pseudocereals n=12 |

Mix | 8 (66.7) |

| Quinoa | 4 (33.3) | |

| Amaranth | 2 (16.7) | |

| Buckwheat | 0 - | |

|

Fruits n=25 |

Mix | 17 (68) |

| Banana | 5 (20) | |

| Apples | 7 (28) | |

| Pears | 4 (16) | |

|

Vegetables n=26 |

Mix | 24 (92.3) |

| Sweet potatoes | 4 (15.4) | |

| Carrots | 3 (11.5) | |

| Zucchini | 2 (7.7) | |

|

Meat n=26 |

Chicken | 22 (84.7) |

| Beef | 10 (38.5) | |

| Turkey | 9 (34.7) | |

| Fish | 7 (26.9) |

| Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories of CCF product* | 1-2 times/week [n, %)] |

3-5 times/week [n, %)] |

6-7 times/week [n, %)] |

p-value |

| Cereals (n=33, 55%) | 22 (66.7) | 4 (12.1) | 7 (21.2) | <0.001 |

| Pseudocereals (n=12, 20%) | 7 (58.3) | 3 (25) | 2 (16.7) | 0.174 |

| Fruits puree (n=25, 58.3%) | 15 (60) | 4 (16) | 6 (24) | 0.016 |

| Vegetables/vegetables with meet jars (n=26, 43.3%) | 15 (57.7) | 7 (27) | 4 (15.3) | 0.024 |

| Flour-based products (n=39, 65%) | 22 (56.4) | 8 (20.5) | 9 (23.1) | 0.009 |

| Dairy based-products (n=38, 63.3) | 23 (60.5) | 8 (21.1) | 7 (18.4) | 0.003 |

| Advantages (n=60) | [n (%)] | p-value | Disadvantages (n=15) |

[n (%)] | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience | 38 (63.3) | p<0.001 | None | 32 (53.3) | p<0.001 |

| Doubtful quality | 12 (20) | ||||

| Extended shelf-life | 8 (13.3) | ||||

| Easily accepted (good palatability) | 18 (30) | Sugar/salt content | 3 (5) | ||

| Diversity | 3 (5) | Won’t accept home-made food | 3 (5) | ||

| Price | 1 (1.67) | ||||

| Gastrointestinal disturbances | 1 (1.67) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).